Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine the role of colonial morphology of Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) organisms in pathogenicity in a mouse model of pulmonary infection. BCC strain C1394 was rapidly cleared by leukopenic mice after intranasal challenge, whereas a spontaneous variant (C1394mp2) that was indistinguishable from the parent strain by genetic typing persisted in the lungs and differed in colonial morphology. The parent strain had a matte colonial phenotype, made scant exopolysaccharide (EPS), and was lightly piliated. The variant had a shiny phenotype, produced abundant EPS, and was heavily piliated. Matte to shiny colonial transformation was induced by growth at 42°C. Colonial morphology in the BCC strain variant was associated with persistence after pulmonary challenge and appeared to be correlated with the elaboration of putative virulence determinants.

Burkholderia cepacia is a serious respiratory pathogen in immunocompromised individuals and in patients with cystic fibrosis (CF). CF patients colonized with B. cepacia exhibit variable clinical responses; however, the organism is rarely eradicated following infection, and colonization can result in fatal pneumonia and septicemia called “cepacia syndrome” (12, 21). Little is known about the pathogenesis of B. cepacia despite the advancements made in understanding the heterogeneity of the species. As a member of a highly diverse family of bacteria, B. cepacia is more accurately represented as a complex of phenotypically similar but genotypically distinct organisms. The B. cepacia complex (BCC) encompasses at least nine genomic species, or genomovars, differentiated by a polyphasic system used for species designation (7, 8, 42). Four genomovars have been assigned binomial classifications: B. multivorans (formerly genomovar II), B. stabilis (genomovar IV), B. vietnamiensis (genomovar V), and B. ambifaria (genomovar VII) (8, 42). All genomovars from the BCC have been isolated from CF patients, a fact which may explain, in part, the variable clinical responses among infected patients (40). The majority of CF isolates in North America, however, are B. multivorans or genomovar III, with the latter group containing the most problematic and epidemic strains (7, 39).

Intrinsic resistance to antibiotics may enable BCC strains to persist in the lungs of CF patients, but the factors that establish infection are still undefined. Putative virulence determinants that have been described include cable pili, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), extracellular protease, lipase, hemolysin, a melanin-like pigment, and siderophores (21, 25). The roles of these factors in lung infections in CF patients remain to be clarified, as their presence does not necessarily correlate with the severity of disease (21, 39).

Reports of mucoid BCC CF isolates suggest a possible pathogenic role for exopolysaccharide (EPS) similar to that of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5, 31). The overproduction of alginate by P. aeruginosa has been shown to contribute to biofilm formation and long-term survival in the lungs of CF patients (10, 12). Alginate production is also associated with the conversion of persistent P. aeruginosa CF isolates from a nonmucoid form to a mucoid form (10, 12). It is not known whether a similar conversion from a nonmucoid form to a mucoid form occurs in BCC strains isolated from CF patients; however, both biofilm formation and EPS production have been described for the BCC (1, 4, 9, 18).

Changes in the bacterial cell envelope are reflected in colonial morphological variations of other gram-negative pathogens (14, 22, 29). The presence or absence of cell surface components such as LPS, pili, flagella, outer membrane proteins, and capsule or EPS may serve as a marker of virulence, as these components often have a direct influence on colonization, drug resistance, and evasion of the host immune response (29, 32). While a correlation exists between the mucoid phenotype and persistent P. aeruginosa CF isolates, little has been described about BCC colonial morphologies that may be associated with virulence or persistence in the host.

To investigate the mechanisms of BCC virulence, we have studied the infectivities of B. multivorans and genomovar III strains by using a mouse model of pulmonary infection. In this model, B. multivorans strains persist, whereas genomovar III strains are rapidly cleared from the lungs (7). Through in vivo selection, we obtained a persistent derivative of a genomovar III strain that exhibited a change from matte to shiny colonial morphology. Comparative analyses of the parent and the derivative identified differences in the cell surface, including EPS production and pilus expression. We also observed induction of the shiny morphology at 42°C. In this report, we describe the conversion of a genomovar III strain from a nonpersistent to a persistent phenotype and describe the putative roles of microbial surface structures in facilitating persistence in a mouse model of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

BCC strain C1394 is a genomovar III isolate recovered from an outbreak among CF patients in Manchester, England (24). Strain variant C1394mp2 was derived by sequential passaging of C1394 through the pulmonary infection model described below. C1394 was recovered at day 16 from the lungs of a cyclophosphamide (CPA)-treated mouse and passaged twice in CPA-treated mice. Strain variant C1394mp2 was recovered at day 4 of the second passage.

Bacteria were stored at −70°C in Mueller-Hinton broth with 8.0% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide and were routinely cultured at 37°C on blood agar plates (PML Microbiologicals, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada) or Luria-Bertani (LB) agar. Liquid cultures were grown in LB broth. To visualize cell surface differences, bacteria were grown on LB agar containing 0.01% (wt/vol) Congo red (Congo red medium [CRM]). For EPS purification, bacteria were grown on a modified version of yeast extract-mannitol (YEM) agar containing 0.05% (wt/vol) yeast extract, 0.4% (wt/vol) mannitol, and 1.5% (wt/vol) agar (35). For heat shock studies, bacteria were grown on LB agar at 42°C.

Mice.

Female BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Canada (St. Constant, Quebec, Canada). All mice were housed and cared for in accordance with the regulations of the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee and the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Mice weighed between 18 and 22 g and were 6 to 8 weeks old at the commencement of each experiment. The general health of the mice was monitored daily by using a three-point grading system as previously described (7).

Immunosuppression and infection of mice.

Mild immunosuppression and infection of BALB/c mice were carried out as previously described (7). Bacteria were cultured from frozen stocks for 48 h on blood agar plates at 37°C. A single isolated colony was used to inoculate 5.0 ml of LB broth, which was incubated for 16 h with mixing by inversion. Cultures were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 2 ml of Hank's balanced salt solution containing 0.1% (wt/vol) gelatin (gHBSS; Gibco BRL). The optical density (at 620 nm) of the culture was determined, and then the culture was diluted to 4 × 105 CFU/ml with gHBSS. Prior to intranasal challenge, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 60 mg of ketamine hydrochloride (MTC Pharmaceuticals)/kg of body weight. Bacteria were delivered drop-wise from a syringe fitted with a 25-gauge needle to alternate nares at an infectious dose of 1.6 × 104 CFU/40 μl. At preselected time points, groups of three mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Lungs were excised, weighed, homogenized, and serially diluted in gHBSS. Dilutions of lung homogenates were spotted on tryptic soy agar quadrant plates and B. cepacia selective agar to enumerate viable bacteria (16).

RAPD, PFGE, and detection of the cable pilus subunit gene (cblA).

Bacterial DNA was prepared and analyzed by random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) as previously described (23, 33). The presence of the cblA gene was determined by PCR as previously described (38).

LPS extraction and serum sensitivity assay.

LPS was extracted by the method developed by Hitchcock and Brown (17). Samples were electrophoresed on a 12% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gel and visualized by using a Pro-Q Emerald 300 LPS gel stain kit (Molecular Probes Inc.). The sensitivity of the strains to pooled human sera was determined as previously described (41).

EPS extraction and purification.

Crude yield extraction studies were performed with EPS extracted from bacteria grown on YEM agar at 37°C for 48 h. The wet weight of bacterial cells was determined prior to EPS isolation. Bacteria were scraped off YEM agar with aqueous phenol (2% [vol/vol] phenol in 0.9% [wt/vol] NaCl) and centrifuged for 30 min at 10,000 × g. The supernatant was dialyzed against distilled water at 4°C for 2 days and lyophilized. Crude EPS was purified by gel filtration chromatography with Sephadex G-100 (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Uppsala, Sweden) followed by ion-exchange chromatography with DEAE-Sephacel (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.2). The column was irrigated with 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer (50 ml), and a gradient of 0 to 0.5 M NaCl in the same buffer was used to remove contaminating nucleic acids and LPS. EPS was then characterized by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), sugar, and methylation analyses.

Analytical methods.

EPS samples (0.5 mg) were hydrolyzed with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid for 1 h at 125°C. Released sugars were determined by gas-liquid chromatography (GLC) of their derived alditol acetates followed by GLC-mass spectrometry (MS) as previously described (34). Alternatively, EPS samples were subjected to methanolysis with refluxing methanolic 2.5% hydrogen chloride for 16 h at 80°C. Samples were neutralized with silver carbonate, reduced with sodium borodeuteride in anhydrous methanol for 16 h at 25°C, hydrolyzed with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid, and analyzed by GLC-MS.

EPS was O deacetylated with 0.1 N NaOH at 37°C for 5 h or 10% (vol/vol) ammonium hydroxide at 37°C for 18 h. Samples (1 mg) were methylated according to the Hakomori procedure (13), and the methylated polysaccharides were hydrolyzed with 4 M trifluoroacetic acid for 1 h at 125°C. Methylation analysis was performed as previously described (34).

NMR analysis was performed by using a Varian INOVA 500 NMR spectrometer with a 5-mm probe. Measurements were made at 22°C and at a concentration of approximately 2 mg/ml in deuterium oxide (D2O), subsequent to several exchanges with D2O. Chemical shifts were reported relative to the methyl resonance of external acetone at 2.225 ppm.

TEM.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was carried out as follows. Bacteria were grown on LB agar at 37°C for 24 and 48 h. Cells were gently resuspended in 1 drop of deionized H2O, and samples were placed on carbon- and Formvar-coated nickel grids for 30 s. Grids were floated on 1 drop of 1% (wt/vol) aqueous uranyl acetate, blotted dry, and then viewed with a Philips EM300 electron microscope at 60 kV under standard operating conditions.

RESULTS

Isolation of a persistent BCC genomovar III variant.

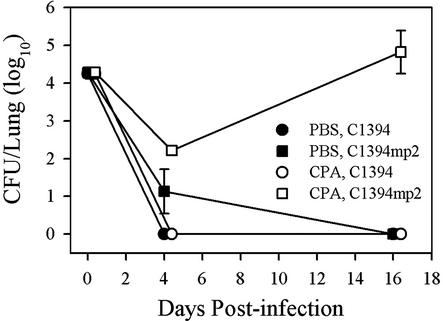

BCC strain C1394 was one of seven genomovar III strains that were previously evaluated with a mouse model of pulmonary infection (7). The genomovar III strains tested expressed a nonpersistence phenotype; all were cleared by day 16, and in most cases by day 4. The only exception to this finding was the recovery of C1394 colonies from one of three CPA-treated mice at numbers equivalent to the inoculating dose (104 CFU). Growth on B. cepacia selective agar and genetic profiling by RAPD analysis and PFGE confirmed that the bacteria recovered were genetically indistinguishable from the challenge strain, C1394. The isolated clone was passaged twice in the same mouse model to evaluate its capacity to persist in mouse lungs. With each passage, greater numbers of bacteria were recovered (data not shown). This phenomenon corroborated previous observations obtained with an i.p. mouse model (41), in which the in vivo passage of a nonpersistent strain promoted the selection of a persistent variant (J. W Chung, K. K. Chu, and D. P. Speert, Abstr. 100th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. D-102, 2000). A C1394 derivative recovered from the second mouse passage was chosen for further study and designated C1394mp2. Figure 1 demonstrates the differences in infectivities observed after challenge in the pulmonary infection model. C1394 was readily eliminated from the lungs of CPA-treated mice (typical of genomovar III strains), but its derivative, C1394mp2, persisted for at least 16 days.

FIG. 1.

Intranasal infection of phosphate-buffered saline-treated and CPA-treated mice with genomovar III strain C1394 and its derivative, C1394mp2. Either one or two mice were evaluated for the number of bacteria deposited in the lungs at day 0 (3 h postinfection). Groups of three mice were sacrificed and evaluated at days 4 and 16. Data are the mean and standard error of the mean for three animals at days 4 and 16.

Phenotypic characterization of C1394 and C1394mp2.

Sugar oxidation-fermentation profiles and oxidase test results were identical for both C1394 and C1394mp2, and although C1394mp2 required a slightly longer incubation time for growth on agar at 37°C, growth rates in LB broth were not significantly different (data not shown). Swimming motility was observed for both C1394 and C1394mp2 by light microscopy. In addition, both the parent and the derivative were serum resistant, although the LPS from both organisms was rough (data not shown).

Differential colonial morphology and heat shock induction.

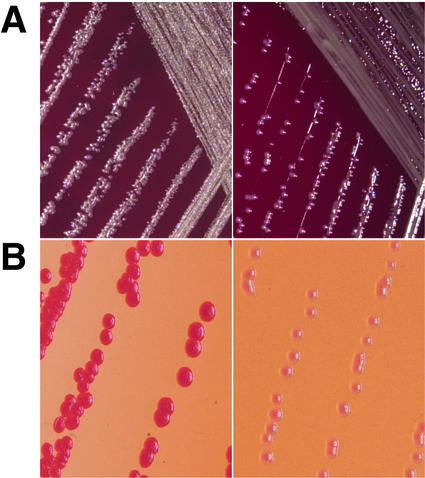

Differences in colonial morphology were observed between strain C1394 and its persistent derivative, C1394mp2 (Fig. 2). On blood agar, tryptic soy agar, and LB agar, the surface of C1394 colonies had a dry, matte appearance, whereas the surface of C1394mp2 colonies was shiny (Fig. 2A). Neither organism displayed the mucoid phenotype typical of P. aeruginosa isolates from chronically infected CF patients. The distinction between the matte and shiny phenotypes was most apparent when bacteria were grown as a dense lawn or when they were grown on CRM. Congo red has been shown to distinguish colonial variants of other bacterial species by differential uptake and binding of the dye to the cell surface (3, 26, 30). After 48 h of growth, strain C1394 absorbed the dye and produced red colonies, whereas C1394mp2 colonies were pink, indicating less absorption of Congo red (Fig. 2B). After 72 h of growth, both C1394 and C1394mp2 colonies had absorbed the dye and were red (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Colonial morphological differences between strains C1394 (left panels) and C1394mp2 (right panels) grown on blood agar (A) or on CRM (B). Strains were grown at 37°C for 48 h.

The colonial morphotypes of C1394 and C1394mp2 were stable for at least five subcultures on LB agar incubated at 37°C. However, when grown at 42°C, C1394 colonies displayed the shiny morphology typical of C1394mp2 colonies. When the heat-shocked, shiny C1394 was removed to 37°C, it reverted to the matte phenotype. In contrast, C1394mp2 colonies maintained their shiny morphotype when grown at either 37 or 42°C.

EPS extraction and characterization.

To determine whether EPS contributed to the differences in colonial morphology, C1394 and C1394mp2 were grown on YEM agar. C1394mp2 produced abundant EPS, which surrounded and masked individual colonies, whereas C1394 produced minimal to moderate amounts of EPS (data not shown). In addition, when C1394 was grown for 48 h on YEM agar containing 0.01% (wt/vol) Congo red, it absorbed the dye, whereas C1394mp2 did not (data not shown). These results suggested that an increased amount of EPS produced by C1394mp2 may have interfered with Congo red binding. Crude EPS was extracted from C1394mp2 grown on YEM agar, and the amount was significantly larger than the amount of EPS extracted from C1394 under the same conditions (10.88 mg of crude EPS per g [wet weight] of C1394 cells versus 39.40 mg per g of C1394mp2 cells).

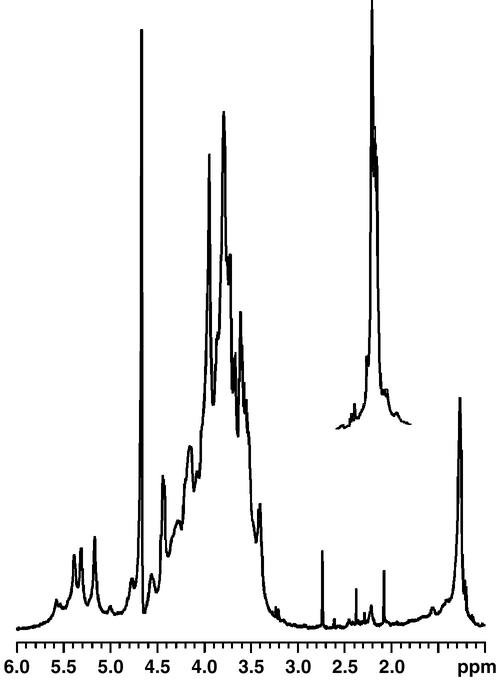

Characterization of the EPS was performed by 1H NMR, sugar, and methylation analyses. The 1H NMR spectrum of crude EPS from C1394mp2 showed the presence of at least three O-acetyl groups in the region from 2.1 to 2.2 ppm (Fig. 3), whereas EPS from C1394 was O acetylated to a much smaller degree. Due to the extreme viscosity of the polysaccharide in water, it was not subjected to further purification by ethanol precipitation. Instead, EPS was purified by gel filtration chromatography with Sephadex G-100 and ion-exchange chromatography with DEAE-Sephacel.

FIG. 3.

1H NMR spectrum of O-deacetylated EPS of strain C1394mp2. The spectrum was recorded in D2O at 37°C. The inset shows the O-acetyl group region of the same polysaccharide prior to O deacetylation.

Purified EPS eluted in the voided volume of the Sephadex G-100 gel filtration column, indicating that it had a high molecular mass. Sugar analysis of purified EPS from both the parent and the derivative revealed the presence of rhamnose, mannose, glucose, and galactose in the ratio 0.5:1.0:0.8:2.1. To confirm the presence of glucuronic acid, EPS was esterified with methanolic hydrogen chloride, followed by reduction of the resultant methyl ester of glucuronic acid with sodium borodeuteride in anhydrous methanol. Subsequent GLC-MS analysis of its hydrolysis products as alditol acetates revealed the presence of rhamnose, mannose, glucose, and galactose in the ratio 0.6:1.0:1.0:2.0; 30% of the glucose was labeled with deuterium, confirming the presence of glucuronic acid. Methylation analysis was carried out without the carboxyl group reduction step, and the substitution pattern for the glucuronic acid residue was not determined. However, our methylation analysis was consistent with the presence of 2-linked rhamnose, terminal galactose, 3-linked glucose, and 3,6-linked mannose, as has been demonstrated for another clinical BCC isolate (6). These results correspond to reports of a highly branched heptasaccharide repeating unit with a similar composition, with O-acetyl groups, and produced by clinical BCC isolates (5, 20). Strain C1394 was shown, in addition to the heptasaccharide repeating unit, to produce a 1,2-linked glucan with occasional branching at position 3.

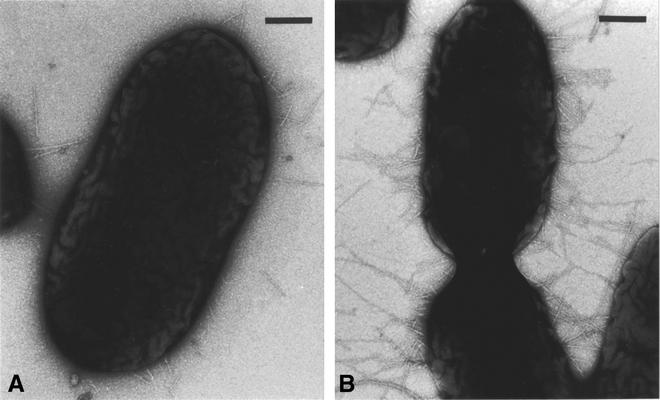

Electron microscopy and pilus expression.

Ultrastructural differences between C1394 and C1394mp2 were observed by TEM. The presence of pili on both C1394 and C1394mp2 can be seen in Fig. 4, with increased piliation on C1394mp2. The pili observed on both the parent and the variant did not resemble the cable pilus associated with the genomovar III epidemic strain ET12. This observation was confirmed by PCR, which did not detect the presence of the cblA gene, the major pilin subunit of the cable pilus. Negative staining also revealed the presence of finer fimbrial structures on both organisms that created a mesh-like network close to the surface of the cells, but these were not present in all images (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Electron micrographs showing piliated bacteria after 24 h of growth on LB agar. (A) C1394. (B) C1394mp2. Bars, 250 nm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the colonial morphology changes of a BCC genomovar III strain that correlated with its persistence in a pulmonary infection model. In this model, B. multivorans has been observed to persist, but genomovar III strains were rapidly cleared from the lungs of mildly immunosuppressed mice (7). Through sequential in vivo passaging of genomovar III strain C1394, we obtained a variant, C1394mp2, that persisted as well as B. multivorans. The genetic backgrounds of C1394 and C1394mp2 appeared to be identical, as determined by macrorestriction of genomic DNA; however, the C1394 colonies had a matte surface and were easily distinguishable from the shiny colonies of C1394mp2. Previous studies with a mouse model of i.p. infection produced similar results with another nonpersistent genomovar III strain (Chung et al., Abstr. 100th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol.). The persistent genomovar III derivative recovered from the i.p. mouse model was also shiny, whereas the parent had a matte phenotype. To our knowledge, a correlation between colonial morphology of BCC organisms and animal infectivity has not been previously described. Our observations suggest a potential role for colonial morphology in differentiating genomovar III strains. Analysis of colonial morphotypes may aid in predicting which BCC strains are most likely to cause persistent rather than transient infections and provide insights into pathogenic potential.

Congo red dye was incorporated into solid media to confirm morphology differences between the parent and the derivative, as this approach has been used for several other diverse bacterial pathogens (3, 26, 30). C1394 colonies readily bound Congo red dye, whereas C1394mp2 colonies did not, indicating differences at the cell surface. Reduced dye absorption may have been due to the loss or modification of a ligand-binding site or to the secretion of a factor impeding Congo red binding. The growth of C1394 and C1394mp2 on YEM agar containing Congo red suggested that the increased EPS production by C1394mp2 may have prevented efficient dye uptake.

Recent reports of mucoid CF isolates of the BCC suggest that EPS production may be important in its pathogenesis (5, 31). Both C1394 and C1394mp2 produced EPS on YEM agar, although the shiny colonial morphology of C1394mp2 correlated with higher levels of EPS production. Characterization studies revealed that both the parent and the variant produced a polymer with glucosyl, rhamnosyl, galactosyl, mannosyl, and glucuronosyl residues, which have been shown to be present as a heptasaccharide repeat unit in the EPS of mucoid BCC clinical isolates (5, 6). It is unknown whether this EPS has a functional role similar to that of the alginate produced by mucoid isolates of P. aeruginosa. Alginate makes up the extracellular matrix of P. aeruginosa biofilms, provides a physical barrier that interferes with nonopsonic and opsonic phagocytosis, scavenges reactive oxygen intermediates, delays the penetration of antimicrobial agents, and therefore may contribute to the persistence of P. aeruginosa in the lungs of CF patients (10, 12). Moreover, O acetylation of alginate is a molecular factor involved in P. aeruginosa resistance to host immune effectors (27). This information may provide some insight into the persistence of C1394mp2 in the pulmonary mouse model, since its EPS had higher levels of O acetylation. Alternatively, the larger amount of EPS produced by C1394mp2 may have prolonged its survival by masking bacterial surface antigens that are targets for phagocytosis or complement, as has been observed with encapsulated Klebsiella pneumoniae (28).

We also detected the production of a 1,2-linked glucan in the EPS of C1394 which requires further investigation. The presence of periplasmic glucans has been described for many bacteria (2). Glucans have been proposed to play a structural role in envelope organization as well as to serve as information molecules sensed by certain proteins in the periplasmic compartment (2). While we cannot, at present, verify how EPS conferred enhanced survival to C1394mp2, our results suggest a possible association between abundant EPS production and persistence in the murine host.

Differential piliation also may have influenced the matte and shiny phenotypes of C1394 and C1394mp2. Piliation has been observed to affect the colonial morphologies of Escherichia coli and Neisseria gonorrheae (14, 22). TEM revealed increased piliation on C1394mp2 cells, which also may have promoted C1394mp2 persistence in mouse lungs, since pilus-mediated attachment is often a critical first step in colonization. The effect of increased piliation was demonstrated in a study by Kuehn et al., in which a heavily piliated B. cepacia strain bound more extensively to A549 cells (19). Functional studies of the only genetically characterized pili of the BCC, cable pili, have further validated the role of these structures in BCC infection. Strains with cable pili were shown to bind to mucin and bound preferentially to CF knockout mouse nasal epithelia and human CF lung explants compared to non-CF control tissues (36, 37). The cblA gene was not detected by PCR in either C1394 or C1394mp2, nor were cable pili observed by TEM. Because other fimbrial types of the BCC have not been fully characterized, we could not classify the pili expressed by C1394 and C1394mp2. Nevertheless, our results were consistent with the work of Kuehn et al. (19) in that increased piliation of C1394mp2 may have conferred enhanced adherence to host cells and led to the establishment of a persistent infection in the mouse model.

The expression of pili as well as other bacterial surface components associated with adhesion and colonial morphology is often subject to phase variation (11, 15). The instability and plasticity of the BCC genome may enhance recombination events and rearrangements associated with phase variation; however, we did not detect any genetic rearrangements in C1394 and C1394mp2. Furthermore, the colonies of both C1394 and C1394mp2 were uniform in their respective colonial morphotypes and were stable for at least five in vitro passages. A switch from a matte to a shiny morphotype was observed only when C1394 was incubated at 42°C. However, the temperature-induced shiny phenotype in C1394 was transient, suggesting that a selective mutational event in C1394mp2 may have stabilized the shiny phenotype and led to its enhanced survival in the host. Heat induction of the shiny phenotype may provide insight into the regulation of EPS production and piliation in C1394. This response may be part of a defense and adaptation mechanism activated as a result of conditions encountered in the host. Whereas EPS and pili are putative factors associated with the shiny colonial morphology, they may not be the only factors involved in the persistence of C1394mp2 in the mouse model.

In summary, we have described adaptation of a BCC genomovar III strain that resulted in its persistence in a mouse model of infection. This persistence correlated with a change in colonial morphology from matte to shiny. Increased EPS production and piliation may have contributed to the shiny morphotype, as these components often dictate the colonial morphology and virulence of other gram-negative pathogens. While EPS production and piliation may indeed enhance bacterial survival, they may not be the only factors involved in persistence, and changes in their expression may coincide with the expression of other potential virulence factors. Further studies will be required to establish the role of BCC surface determinants in the pathogenesis of this evolving complex of opportunistic pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karen Chu for technical assistance in the mouse experiments, Vandana Chandan for the GLC-MS analyses, Suzon Larocque for the recording of NMR spectra, and Dianne Moyles for the TEM work. We also thank Barbara-Ann Conway for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

J.W.C. was supported by a studentship from the Canadian Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CCFF). This work was supported by grants from the CCFF (to D.P.S.), the British Columbia Lung Association (to D.P.S.), and the Canadian Bacterial Disease Network (to E.A., T.J.B., and D.P.S.).

Editor: D. L. Burns

REFERENCES

- 1.Allison, D. G., and M. J. Goldsbrough. 1994. Polysaccharide production in Pseudomonas cepacia. J. Basic Microbiol. 34:3-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohin, J. P. 2000. Osmoregulated periplasmic glucans in Proteobacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 186:11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cangelosi, G. A., C. O. Palermo, J. P. Laurent, A. M. Hamlin, and W. H. Brabant. 1999. Colony morphotypes on Congo red agar segregate along species and drug susceptibility lines in the Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex. Microbiology 145:1317-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cérantola, S., J. Bounéry, C. Segonds, N. Marty, and H. Montrozier. 2000. Exopolysaccharide production by mucoid and non-mucoid strains of Burkholderia cepacia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 185:243-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cérantola, S., A. Lemassu-Jacquier, and H. Montrozier. 1999. Structural elucidation of a novel exopolysaccharide produced by a mucoid clinical isolate of Burkholderia cepacia. Characterization of a trisubstituted glucuronic acid residue in a heptasaccharide repeating unit. Eur. J. Biochem. 260:373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cescutti, P., M. Bosco, F. Picotti, G. Impallomeni, J. H. Leitão, J. A. Richau, and I. S -Correia. 2000. Structural study of the exopolysaccharide produced by a clinical isolate of Burkholderia cepacia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 273:1088-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu, K. K., D. J. Davidson, T. K. Halsey, J. W. Chung, and D. P. Speert. 2002. Differential persistence among genomovars of the Burkholderia cepacia complex in a murine model of pulmonary infection. Infect. Immun. 70:2715-2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coenye, T., P. Vandamme, J. R. Govan, and J. J. LiPuma. 2001. Taxonomy and identification of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3427-3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conway, B. A., V. Venu, and D. P. Speert. 2002. Biofilm formation and acyl homoserine lactone production in the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Bacteriol. 184:5678-5685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deretic, V., M. J. Schurr, J. C. Boucher, and D. W. Martin. 1994. Conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to mucoidy in cystic fibrosis: environmental stress and regulation of bacterial virulence by alternative sigma factors. J. Bacteriol. 176:2773-2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiRita, V. J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1989. Genetic regulation of bacterial virulence. Annu. Rev. Genet. 23:455-482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govan, J. R., and V. Deretic. 1996. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol. Rev. 60:539-574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakomori, S. 1964. Rapid permethylation of glycolipids and polysaccharides by methylsulfinyl carbanion in dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 55:205-208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasman, H., M. A. Schembri, and P. Klemm. 2000. Antigen 43 and type 1 fimbriae determine colony morphology of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 182:1089-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson, I. R., P. Owen, and J. P. Nataro. 1999. Molecular switches—-the ON and OFF of bacterial phase variation. Mol. Microbiol. 33:919-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry, D. A., M. E. Campbell, J. J. LiPuma, and D. P. Speert. 1997. Identification of Burkholderia cepacia isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis and use of a simple new selective medium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:614-619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hitchcock, P. J., and T. M. Brown. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154:269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huber, B., K. Riedel, M. Hentzer, A. Heydorn, A. Gotschlich, M. Givskov, S. Molin, and L. Eberl. 2001. The cep quorum-sensing system of Burkholderia cepacia H111 controls biofilm formation and swarming motility. Microbiology 147:2517-2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuehn, M., K. Lent, J. Haas, J. Hagenzieker, M. Cervin, and A. L. Smith. 1992. Fimbriation of Pseudomonas cepacia. Infect. Immun. 60:2002-2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linker, A., L. R. Evans, and G. Impallomeni. 2001. The structure of a polysaccharide from infectious strains of Burkholderia cepacia. Carbohydr. Res. 335:45-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LiPuma, J. J. 1998. Burkholderia cepacia. Management issues and new insights. Clin. Chest Med. 19:473-486, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long, C. D., R. N. Madraswala, and H. S. Seifert. 1998. Comparisons between colony phase variation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae FA1090 and pilus, pilin, and S-pilin expression. Infect. Immun. 66:1918-1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahenthiralingam, E., M. E. Campbell, D. A. Henry, and D. P. Speert. 1996. Epidemiology of Burkholderia cepacia infection in patients with cystic fibrosis: analysis by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2914-2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahenthiralingam, E., T. Coenye, J. W. Chung, D. P. Speert, J. R. Govan, P. Taylor, and P. Vandamme. 2000. Diagnostically and experimentally useful panel of strains from the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:910-913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohr, C. D., M. Tomich, and C. A. Herfst. 2001. Cellular aspects of Burkholderia cepacia infection. Microbes Infect. 3:425-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payne, S. M., and R. A. Finkelstein. 1977. Detection and differentiation of iron-responsive avirulent mutants on Congo red agar. Infect. Immun. 18:94-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pier, G. B., F. Coleman, M. Grout, M. Franklin, and D. E. Ohman. 2001. Role of alginate O acetylation in resistance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to opsonic phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 69:1895-1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podschun, R., and U. Ullmann. 1998. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:589-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poolman, J. T., C. T. Hopman, and H. C. Zanen. 1985. Colony variants of Neisseria meningitidis strain 2996 (B:2b:P1.2): influence of class-5 outer membrane proteins and lipopolysaccharides. J. Med. Microbiol. 19:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qadri, F., S. A. Hossain, I. Čižnár, K. Haider, A. Ljungh, T. Wadstrom, and D. A. Sack. 1988. Congo red binding and salt aggregation as indicators of virulence in Shigella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:1343-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richau, J. A., J. H. Leitão, M. Correia, L. Lito, M. J. Salgado, C. Barreto, P. Cescutti, and I. S -Correia. 2000. Molecular typing and exopolysaccharide biosynthesis of Burkholderia cepacia isolates from a Portuguese cystic fibrosis center. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1651-1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts, I. S. 1996. The biochemistry and genetics of capsular polysaccharide production in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:285-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodley, P. D., U. Römling, and B. Tümmler. 1995. A physical genome map of the Burkholderia cepacia type strain. Mol. Microbiol. 17:57-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadovskaya, I., J. R. Brisson, E. Altman, and L. M. Mutharia. 1996. Structural studies of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen and capsular polysaccharide of Vibrio anguillarum serotype O:2. Carbohydr. Res. 283:111-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sage, A., A. Linker, L. R. Evans, and T. G. Lessie. 1990. Hexose phosphate metabolism and exopolysaccharide formation in Pseudomonas cepacia. Curr. Microbiol. 20:191-198. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sajjan, U. S., and J. F. Forstner. 1992. Identification of the mucin-binding adhesin of Pseudomonas cepacia isolated from patients with cystic fibrosis. Infect. Immun. 60:1434-1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sajjan, U., Y. Wu, G. Kent, and J. Forstner. 2000. Preferential adherence of cable-piliated Burkholderia cepacia to respiratory epithelia of CF knockout mice and human cystic fibrosis lung explants. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:875-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sajjan, U. S., L. Sun, R. Goldstein, and J. F. Forstner. 1995. Cable (cbl) type II pili of cystic fibrosis-associated Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia: nucleotide sequence of the cblA major subunit pilin gene and novel morphology of the assembled appendage fibers. J. Bacteriol. 177:1030-1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speert, D. 2001. Understanding Burkholderia cepacia: epidemiology, genomovars, and virulence. Infect. Med. 18:49-56. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Speert, D. P., D. Henry, P. Vandamme, M. Corey, and E. Mahenthiralingam. 2002. Epidemiology of Burkholderia cepacia complex in patients with cystic fibrosis, Canada. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:181-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Speert, D. P., B. Steen, K. Halsey, and E. Kwan. 1999. A murine model for infection with Burkholderia cepacia with sustained persistence in the spleen. Infect. Immun. 67:4027-4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vandamme, P., B. Holmes, M. Vancanneyt, T. Coenye, B. Hoste, R. Coopman, H. Revets, S. Lauwers, M. Gillis, K. Kersters, and J. R. Govan. 1997. Occurrence of multiple genomovars of Burkholderia cepacia in cystic fibrosis patients and proposal of Burkholderia multivorans sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:1188-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]