Abstract

Initiator proteins are critical components of the DNA replication machinery and mark the site of initiation. This activity probably requires highly selective DNA binding; however, many initiators display modest specificity in vitro. We demonstrate that low specificity of the papillomavirus E1 initiator results from the presence of a non-specific DNA-binding activity, involved in melting, which masks the specificity intrinsic to the E1 DNA-binding domain. The viral factor E2 restores specificity through a physical interaction with E1 that suppresses non-specific binding. We propose that this arrangement, where one DNA-binding activity tethers the initiator to ori while another alters DNA structure, is a characteristic of other viral and cellular initiator proteins. This arrangement would provide an explanation for the low selectivity observed for DNA binding by initiator proteins.

Keywords: DNA binding/DNA replication/initiator/specificity factor

Introduction

Initiator proteins bind to the origin of DNA replication and orchestrate melting and unwinding of the double-stranded ori DNA. The range of activities associated with different initiators varies, but one function all initiators share is the recognition and ‘marking’ of the ori. The initiators DnaA from Escherichia coli and the viral initiators T-antigen (T-ag) from SV40 and E1 from papillomavirus also take part in the melting of ori that heralds the onset of DNA synthesis. T-ag and E1, in addition, function as replicative DNA helicases (for reviews, see Fanning and Knippers, 1992; Sverdrup and Myers, 1997).

Initiators must recognize specific sites involved in DNA replication in a vast excess of non-ori DNA, and are therefore expected to display a high degree of specificity, i.e. the ability to distinguish between a cognate site and other DNA. Viral initiators face a similar challenge; early after infection, a single copy of the ori is present in a vast excess of host DNA and has to be recognized by low levels of the initiator. Thus, the requirement for a high degree of selectivity is likely to be similar for viral and cellular initiators. Contrary to expected behavior, however, many cellular and viral initiators display low DNA binding selectivity in vitro, and the intrinsic selectivity of initiators appears to fall far short of the selectivity required for in vivo function. For example, cellular initiators, such as the ORC complexes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, bind their replicators or autonomously replicating sequences (ARS) with modest to low selectivity (Kong and DePamphilis, 2001; Lee et al., 2001; Bell, 2002; Chuang et al., 2002) that is not likely to be sufficient for the required in vivo selectivity (Bell, 2002). It currently is unclear whether, in higher organisms, origin recognition complexes (ORCs) bind to DNA site-specifically or if they utilize an entirely different mechanism.

The bovine papillomavirus (BPV) E1 initiator has characteristics similar to the cellular initiators. In in vitro assays for DNA binding selectivity, such as competition assays with non-specific DNA, the E1 protein has a very limited capacity to distinguish between its cognate sites in the origin of DNA replication and unrelated DNA (Yang et al., 1993; Sedman and Stenlund, 1995). Depending on the type of competitor, the cognate site is recognized only 10–100 times better than non-specific DNA (Sedman and Stenlund, 1995). This level of selectivity allows for DNA binding assays such as DNase footprinting but is far from sufficient for in vivo function. In comparison, a highly selective protein such as λ repressor, which is capable of recognizing a single site in a bacterial genome, has a selectivity that is at least 106-fold greater than that of E1 (Johnson et al., 1981). Papillomavirus replication in vivo, however, requires the presence of the virus-encoded transcription factor E2. In the presence of E2, the in vitro selectivity associated with E1 binding is increased several hundred-fold. This increase in selectivity requires interaction between E1 and E2, and cooperative binding of E1 and E2 to ori (Sedman and Stenlund, 1995; Sanders and Stenlund, 2000). The dependence on E2 for DNA replication can be reproduced in vitro by the addition of non-specific competitor DNA, indicating that an important function of E2 in DNA replication is to act as a specificity factor (Yang et al., 1993; Sedman and Stenlund, 1995).

E1 and E2 bind to adjacent binding sites in ori, generating an E12E22 complex that is essential for DNA replication in vivo and has been characterized extensively (Sedman et al., 1997; Sanders and Stenlund, 1998). After recognition of the ori by this complex, E2 is displaced in an ATP-dependent manner and additional E1 molecules are added, generating larger complexes that can modify the ori structure (Lusky et al., 1994; Sanders and Stenlund, 1998). These larger E1 complexes have low intrinsic sequence specificity but, because they are formed via the prior specific E12E22 complex, they occur only on the ori. Thus it has been suggested that the function of E2 is to tether E1 specifically to the ori (Mohr et al., 1990; Yang et al., 1991; Sedman and Stenlund, 1995; Sanders and Stenlund, 1998).

Here we demonstrate that E2 functions by a different mechanism. We have determined the basis for specific and non-specific DNA binding by E1. First, unexpectedly, although the net specificity of full-length E1 is low, the E1 DNA-binding domain (DBD) has the intrinsic ability to bind to DNA with high sequence specificity. The presence of a second, non-specific DNA-binding activity in the helicase domain of E1 masks the intrinsic specificity of the E1 DBD. The net effect is a low overall selectivity of the full-length E1 resulting from the sum of the two distinctly different DNA-binding activities. Secondly, E2 restores E1 DNA binding specificity by blocking the ability of E1 to bind to DNA non-specifically. This results in the unmasking of the specific DNA-binding activity intrinsic to the E1 DBD. This mechanism explains how E1 functions as a highly specific initiator. Furthermore, the two modes of DNA binding provide strong hints as to how initiator complexes are assembled and function. We propose that the non-specific DNA-binding activity of E1 is a property common to initiator proteins that is required for initiator function. The presence of such an activity could be the cause of the low apparent selectivity observed for many initiator proteins, including ORCs. The low selectivity of initiators such as ORC thus may not be due to the absence of a specific DNA-binding activity, but to the presence of both a specific and a non-specific DNA-binding activity.

Results

The full-length E1 protein and the E1 DBD bind DNA differently

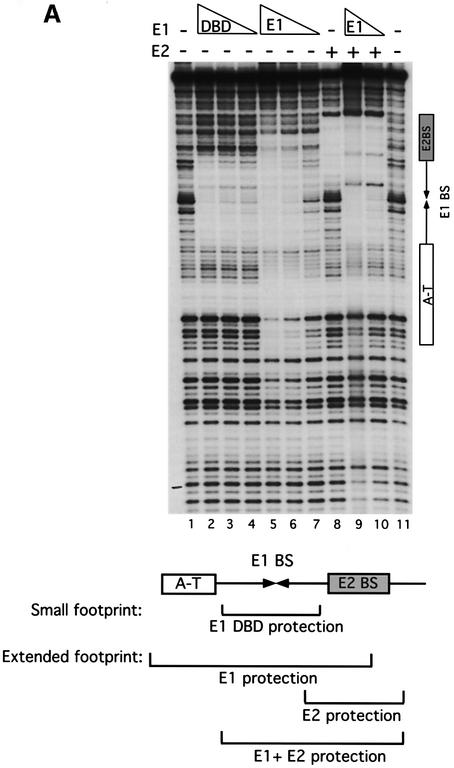

To determine how E2 affects DNA binding by E1 and how binding of E1 differs from binding of the E1 DBD, we performed DNase footprinting analysis on the top strand of the ori comparing the footprints generated by the E1 DBD alone, E1 alone, E2 alone, and E1 and E2 together (Figure 1A). The E1 DBD gave rise to a discrete small footprint covering the E1-binding sites only (small footprint, lanes 2–4). Full-length E1, however, gave rise to a much larger footprint extending on both sides of the E1-binding sites (extended footprint, lanes 5–7). E2 alone gave rise to a discrete footprint over the E2-binding site (lane 8). Interestingly, E1 and E2 proteins binding together gave rise to a combined small footprint corresponding to the sum of the individual protections observed with the E1 DBD and E2 (compare lanes 9 and 10 with 2 and 8). This demonstrates that E1 binds to ori differently in the presence of E2 than in its absence. In the combined E12E22 complex, E1 binds DNA in a way that is very similar to how the E1 DBD binds and, in the absence of E2, E1 protects the sequences flanking the E1-binding sites.

Fig. 1. (A) E1 and the E1 DBD bind the ori differently. DNase I footprinting was carried out on the top strand of the minimal ori using the E1 DBD (8, 4 and 2 ng, lanes 2–4), full-length E1 (20, 10 and 5 ng, lanes 5–7), full-length E2 (1 ng, lane 8) and full-length E1 (10 and 5 ng) and E2 (1 ng) together (lanes 9 and 10). Shown below is the extent of protection generated by the different proteins relative to the AT-rich region (A-T), the E1-binding sites (E1 BS) and the E2-binding site (E2 BS). (B) The E1 DBD binds DNA with a high degree of selectivity while full-length E1 binds with low selectivity. DNase footprinting was carried out on the top strand of the minimal ori using the E1 DBD (8 ng, lanes 2–6), full-length E1 (20 ng, lanes 7–11) and full-length E1 and E2 (5 and 1 ng, respectively, lanes 12–16). Competitor DNA, poly(dI–dC), at the indicated concentrations was mixed with the probe followed by the addition of protein. In lanes 1, 2, 7 and 12, no competitor DNA was added.

The E1 protein binds the ori with low selectivity, whereas the E1 DBD binds with high selectivity

The E1 footprint is very sensitive to the presence of non-specific competitor DNA, indicating a low level of DNA binding specificity (Sedman and Stenlund, 1995). We determined whether the E1 DBD behaves like the full-length E1 protein by comparing footprints of E1 and the E1 DBD in the presence of competitor DNA (Figure 1B). We added 1, 10, 100 or 1000 ng of the non-specific competitor poly(dI–dC) to the probe, before addition of protein to the binding reactions. As expected, binding by the full-length E1 was readily competed, and 1 ng of competitor was the highest concentration where protection could still be observed (lanes 7–11). Surprisingly, the E1 DBD showed no sensitivity to any of these levels of competitor DNA (lanes 2–6), demonstrating an ∼1000-fold higher selectivity than full-length E1. At the highest concentration, competitor is present at ∼104-fold excess over probe, and the E1 DBD thus displays a specificity similar to E1 in combination with E2 (lanes 12–16) (Sedman and Stenlund, 1995). These results demonstrate that the E1 DBD is intrinsically capable of highly selective DNA binding. Since mutations in the E1-binding sites affect the binding of the full-length E1 and E1 DBD similarly, the full-length E1 protein binds DNA via the E1 DBD (Sedman et al., 1997; Chen and Stenlund, 2001). The low selectivity therefore must result from the presence of other domains in the full-length E1 protein. A likely explanation is that the full-length E1 protein is capable of non-specific DNA binding and that this activity masks the selectivity of the E1 DBD in assays utilizing competitor DNA. Thus, in the context of the full-length E1 protein, generation of specific binding requires that the selectivity of which the E1 DBD is intrinsically capable is exhibited or unmasked.

Both the high degree of selectivity and the similarity of the footprints indicate that E1 in combination with E2 binds DNA in the same way that its DBD binds DNA on its own. This is also supported by high resolution hydroxyradical footprinting, which has been performed for both the E1 DBD and E12E22 complexes and indicates virtually identical E1 protections (Sedman and Stenlund, 1996; Chen and Stenlund, 2002). A likely function for E2 therefore is the unmasking of the highly selective E1 DBD-binding activity.

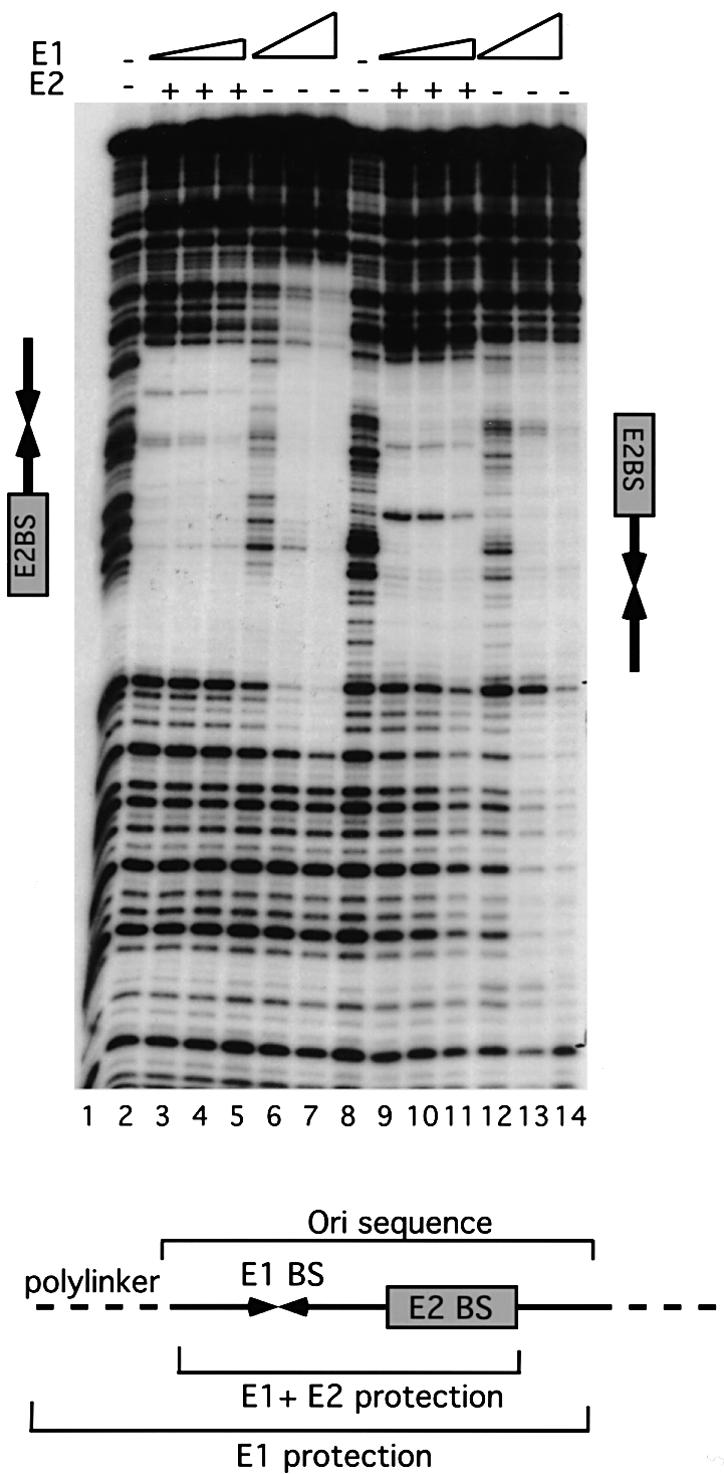

The extension of the E1 footprint is not sequence dependent

The footprinting experiments above show that low selectivity for binding correlates with protection of DNA sequences flanking the E1-binding sites. If these flanking protections result from non-specific DNA binding, the activity that gives rise to them might be the very activity that obscures selective DNA binding by the E1 DBD. We tested the flanking protections for DNA sequence specificity using a probe where the E1-binding site is flanked on one side by polylinker sequences and on the other side by ori sequences (Figure 2). We used this probe in DNase footprinting and compared the size of the footprint as well as the extent of protection for the two sides with E1 alone and with E1 in the presence of E2. As observed with the wild-type ori, E1 alone gave rise to a significantly larger footprint than E1 and E2 (compare lanes 2–4 and 9–11 with lanes 5–7 and 12–14). The extended protection is symmetrical, and 22 bp in each direction is protected beyond the sequences protected by the E1 DBD (data not shown). These extensions appeared simultaneously on both the left and right flanks of the E1-binding sites, indicating that binding to these sequences occurs at the same concentration of E1 irrespective of whether polylinker or ori sequences are present on the flanks. This indicates at most a modest sequence dependence for generation of the flanking protections.

Fig. 2. The E1 footprint extends symmetrically over two helical turns of flanking sequence. An ori fragment spanning the E1- and E2-binding sites, but lacking the AT-rich region, was inserted into the polylinker of pUC19 in two orientations to provide two different contexts of flanking sequences. Probes were generated from both orientations, and DNase footprinting was performed with E1 (10, 5 and 2.5 ng) and E2 (1 ng) in combination (lanes 2–4 and lanes 9–11), or with E1 alone (5, 10 and 20 ng, lanes 5–7 and lanes 12–14). Below is shown schematically the extent of the protections relative to the elements in the ori.

If E2 is capable of ‘neutralizing’ the non-specific DNA-binding activity that masks specific binding by E1 DBD, specific DNA binding would result. The interaction between the E1 and E2 proteins is complex, and involves two separate, physical interactions (Ferguson and Botchan, 1996; Berg and Stenlund, 1997; Masterson et al., 1998; Titolo et al., 1999; Chen and Stenlund, 2000). The DBDs of both proteins interact and generate a sharp (∼90°) bend in the ori. The consequence of the induced bend is to allow the E2 activation domain (AD) to interact physically with the C-terminus of E1 (the helicase domain) to form a stable E12E22–DNA complex (Berg and Stenlund, 1997; Chen and Stenlund, 1998; Gillitzer et al., 2000). The effect on DNA sequence specificity can also be generated from a distal E2-binding site where the cooperative binding depends solely on the interaction between the E2 AD and the E1 helicase domain (Berg and Stenlund, 1997; A.Stenlund, unpublished data). Therefore, the interaction between the E1 helicase domain and the E2 AD is the prime candidate for the effect on E1 specificity. A prediction of this model is that removal of the E2 AD would allow the flanking E1 protection to be regained.

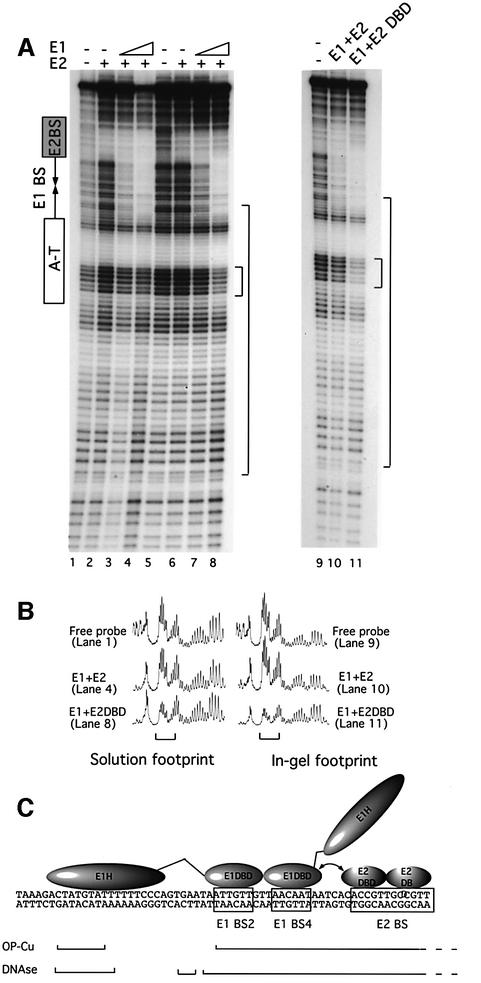

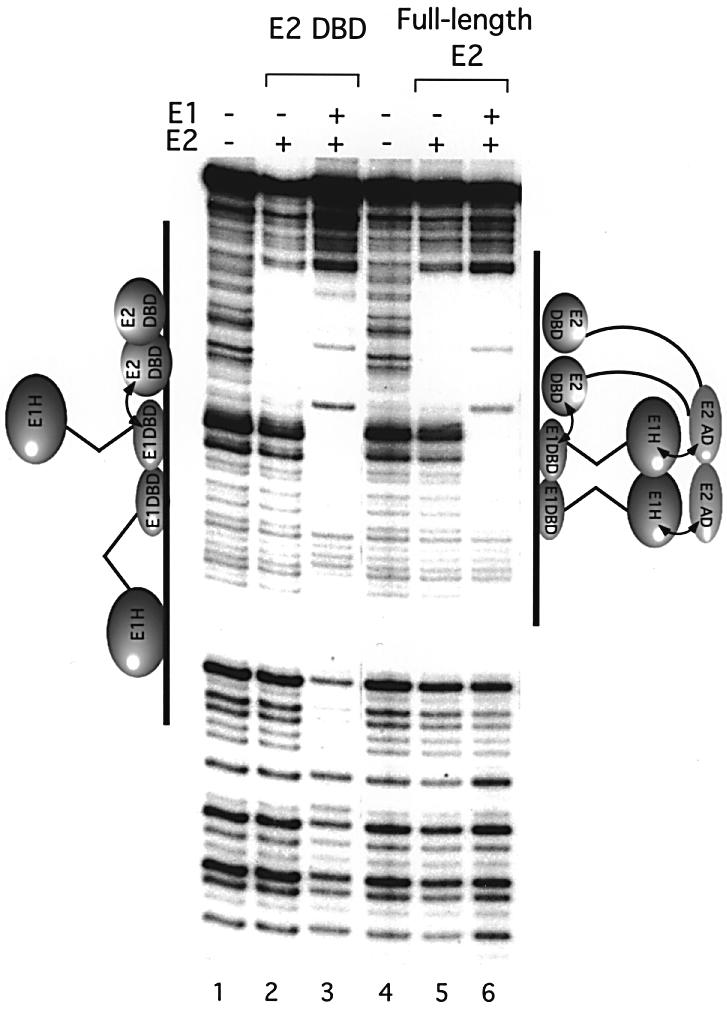

The role of the E2 AD in the generation of the two types of footprints was determined by comparing E1 footprints in the presence of full-length E2 which contains the AD, and E2 DBD which lacks the AD (Figure 3). Full-length E2 and the E2 DBD give rise to identical footprints (compare lanes 2 and 5). Full-length E1 and E2 proteins together generate the small footprint (lane 6), as observed above (see Figure 1A). Interestingly, when E1 and the E2 DBD are bound together, the small footprint is extended in a manner similar to that observed with full-length E1 alone (lane 3), but in one direction only, presumably due to the presence of the E2 DBD on the other side. This result indicates that in the absence of the E2 AD, E1 is free to extend the footprint over the flanking sequences. These data provide support for the idea that the presence of the E2 AD prevents the appearance of the flanking protections. To address the mechanism by which this occurs, we analyzed the architecture of complexes containing E1 and E2 bound to the ori.

Fig. 3. E1 generates the small footprint together with E2, but the extended footprint with the E2 DBD. DNase footprinting was performed on the top strand of the wild-type ori using E2 alone (1 ng, lane 5), the E2 DBD alone (0.5 ng, lane 2), E1 and E2 (5 and 1 ng, respectively, lane 6), and E1 and the E2 DBD (5 and 0.5 ng, respectively, lane 3).

The flanking E1 protections are caused by binding of a domain other than the E1 DBD

The extended protections observed with full-length E1 could be caused either by binding of additional E1 molecules on the flanks of the E1-binding sites, or by binding of other domains of the very same molecules that are bound to the E1-binding sites. A way to distinguish between these two possibilities is examination of the protections in complexes of defined size and composition. For example, if a dimer of E1 that is bound to the E1-binding sites can generate flanking protections, the flanking protections probably result from contacts with other domains within the same two molecules that are bound to the paired E1-binding sites via their DBDs.

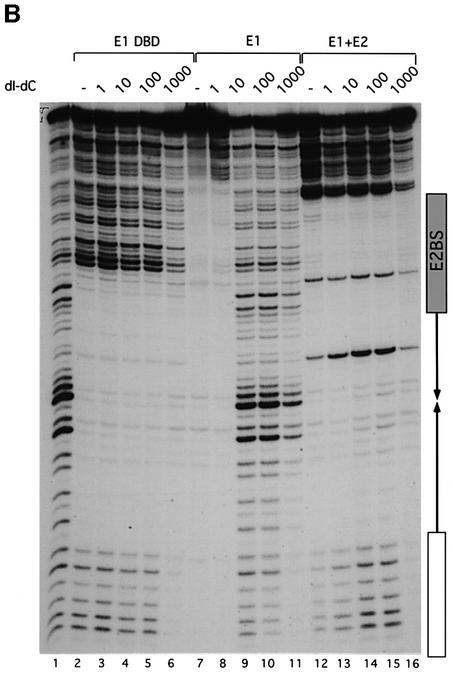

To examine E1 binding under conditions where the stoichiometry of the complexes is known, we wanted to isolate a defined E1 complex after electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and analyze the resulting protections. Orthophenantroline-copper (OP-Cu) footprinting is particularly well suited for this purpose since cleavage can be carried out in gel slices excised from such gels (Sigman et al., 1991). EMSA with E1, however, presents difficulties, since E1 by itself does not form site-specific complexes under any known EMSA conditions. Instead, E1 binding produces ladders that result from non-specific binding as judged by the lack of sequence dependence for generation of these ladders (Figure 4, lanes 2–4 and 8–10, and data not shown). Discrete E1 complexes in which E1 is bound sequence-specifically to the probe can be generated in the presence of E2. As shown above, the E12E22 cooperative complex generates the small footprint, which provides no information about flanking protections. However, in the presence of the E2 DBD, the E1 flanking protections can be observed (Figure 3). We conjectured, therefore, that if discrete E1 complexes with the E2 DBD could be generated, these could be used to analyze the flanking protections.

Fig. 4. Formation of E12E22 and E12(E2 DBD)2 complexes. EMSA was performed using full-length E1 alone (0.5, 1 and 2 ng, lanes 2–4 and lanes 8–10) and E1 (0.5 ng) in the presence of E2 (0.1 ng, lane 6) or the E2 DBD (0.05 ng, lane 12). Lanes 5 and 11 contained 0.1 ng of E2 and 0.05 ng of the E2 DBD, respectively. Lanes 1 and 7 contained probe alone. The ladders generated by E1 alone in lanes 3 and 10 serve as markers. The number of molecules in each complex is indicated.

We successfully generated complexes that contain E1 and the E2 DBD using conditions under which the E12E22 complex is formed. We added either full-length E2 or the E2 DBD to a low concentration of E1 where no binding of E1 alone can be observed. As shown in Figure 4, lane 6, addition of E2 results in the formation of a cooperative E12E22 complex, which we have previously characterized extensively (Sedman et al., 1997; Sanders and Stenlund, 1998). This complex migrates slightly more slowly than three E1 molecules (compare lanes 4 and 6). Similarly, upon addition of the E2 DBD, a new complex is generated (lane 12). This complex migrates slightly more slowly than two E1 molecules, consistent with this complex containing two molecules of E1 and two molecules of the E2 DBD (compare lanes 10 and 12). The degree of cooperativity is significantly lower for the complex with E1 and the E2 DBD as compared with that between E1 and full-length E2. Addition of E1 to E2 in lane 6 results in a shift of all DNA-bound E2 (compare lanes 5 and 6). Addition of the same level of E1 to E2 DBD in lane 12 results in a shift of only a fraction of the DNA-bound E2 DBD (compare lanes 11 and 12).

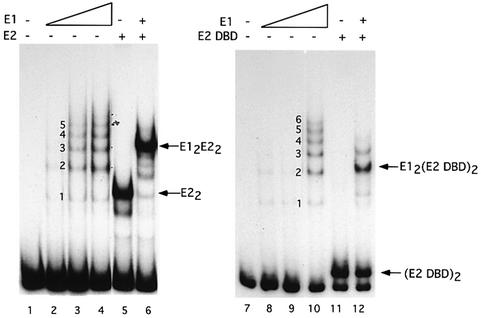

To determine whether OP-Cu footprinting can distinguish between the small and the extended protections observed with DNase I, we performed OP-Cu footprinting in solution comparing E1 binding in the presence of either E2 or the E2 DBD (Figure 5A, lanes 1–8). E2 and the E2 DBD give rise to identical solution protections (lanes 2 and 6). In the presence of E1, a combined protection over the E1- and E2-binding sites similar to that observed by DNase I is observed (lanes 3 and 4). Binding of E1 and E2 DBD generates a footprint that is very similar to that generated by E1 and E2; however, an extension of this footprint is observed (Figure 5A, lanes 7 and 8, see also tracings in B).

Fig. 5. In-gel OP-Cu footprinting of E12E22 and E12(E2 DBD)2 complexes. (A) Solution OP-Cu footprints were generated with E1 and E2 (lanes 1–4) or E1 and the E2 DBD (lanes 5–8). Two quantities of full-length E1, 25 and 50 ng, in the presence of 5 ng of E2 (lanes 3 and 4), or in the presence of 2.5 ng of the E2 DBD (lanes 7 and 8) were bound. Solution footprints with E2 and the E2 DBD alone (5 and 2.5 ng, respectively) are shown in lanes 2 and 6. In-gel OP-Cu footprints were performed on free probe (lane 9) and with complexes formed by E1 and E2 (lane 10) and complexes formed by E1 and the E2 DBD (lane 11). The large bracket indicates the section of the gels that was quantitated and is shown in (B). (B) The gels were exposed to a Fuji imaging plate and the profiles for six selected lanes are shown below. The small bracket indicates the flanking sequences that are protected in the E12(E2 DBD)2 complex. (C) A schematic summary of the DNase I and OP-Cu protections observed on the top strand for the E12(E2 DBD)2 complex in relation to the position of the E1- and E2-binding sites.

To determine how the molecules are bound in the E1–E2 complexes with known stoichiometry, we performed OP-Cu footprinting with the E12E22 and E12E2 DBD2 complexes isolated from EMSA gels. As shown in lanes 10 and 11, the extended protection is observed in the presence of E1 and E2 DBD, but not in the presence of E1 and E2 (compare the tracings for lanes 9, 10 and 11 in Figure 5B). This demonstrates that the flanking protection is caused by the dimer of E1 bound to the E1-binding sites and, consequently, that an E1 molecule that is bound to the E1-binding sites via its DBD is responsible for this protection. These data indicate that another domain in E1 is capable of binding to the flanking sequences non-specifically and that the E2 AD is capable of preventing this flanking interaction. Since the E2 AD is known to interact with the E1 helicase domain, this raises the strong possibility that the E1 helicase domain is responsible for the interaction with the flanking DNA (Masterson et al., 1998; Titolo et al., 1999).

The E1 helicase domain can be cross-linked specifically to the sequences flanking the E1-binding sites

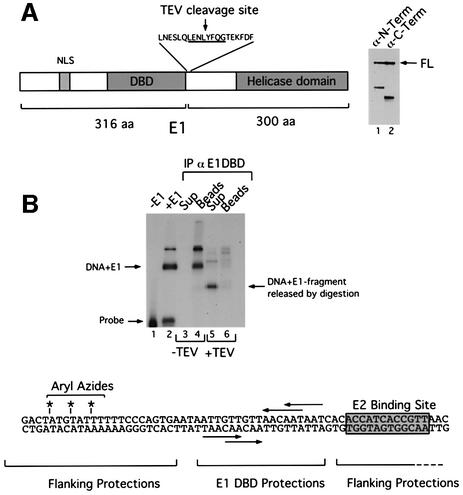

To obtain further direct evidence that the E1 helicase domain is responsible for generating the flanking protections, we used a UV cross-linking approach similar to that used by Aurora and Herr (1992). We generated an E1 protein with a TEV protease cleavage site inserted between the E1 DBD and the helicase domain (E1-TEV). Digestion of this protein generates two halves that are similar in size, one half containing the N-terminus and the DBD, the other half containing the C-terminal helicase domain. After a partial digestion with TEV, we could detect the two halves (as well as the full-length E1 protein) using monoclonal antibodies directed against either the N- or the C-terminal half of E1 (Figure 6A, lanes 1 and 2).

Fig. 6. Site-specific UV cross-linking demonstrates that the E1 helicase domain binds to the AT-rich region. (A) An E1 protein engineered with a TEV protease cleavage site inserted between the DBD and the helicase domain was expressed, purified and used for UV cross-linking experiments. Digestion of this protein with TEV protease generates two fragments, an N-terminal fragment of 35 kDa and a C-terminal fragment of 30 kDa, which can be detected by western blotting using monoclonal antibodies directed against the N- (lane 1) and C-terminus (lane 2) of the E1 protein. (B) The probe for UV cross-linking was generated by modifying an oligonucleotide with three phosphorothioate linkages with azidophencyl bromide to generate aryl azides in the flanking sequence upstream (left) of the E1-binding sites. An ori probe was generated by PCR using the modified oligonucleotide and a 32P-labeled primer from the other strand. This probe was used for UV cross-linking to E1-TEV. After UV irradiation, the level of cross- linking in the absence or presence of E1 was assessed by SDS–PAGE (lanes 1 and 2). The UV-irradiated sample was purified by ion exchange chromatography and immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal antiserum against the E1 DBD (lanes 4–6). After the immunoprecipitation, the sample was divided in two, and incubated with (lanes 5 and 6) or without (lanes 3 and 4) TEV protease. Following digestion, the protein G beads (lanes 4 and 6) and the supernatants (lanes 3 and 5) were separated and analyzed by SDS–PAGE.

We generated a template for cross-linking using an oligonucleotide with three phosphorothioate linkages in the AT-rich region that is protected in the extended footprint but not in the small footprint (Figure 6B). After 5′ end labeling of the oligonucleotide, it was treated with azidophenacyl bromide that generates photoreactive aryl azides at the phosphorothioate linkages. We used this modified oligonucleotide for PCR to generate ori probes. After purification of the probe, we assembled binding reactions using E1 containing the TEV site and performed UV cross-linking at 312 nm. A very prominent cross-linked complex appeared with high efficiency in the presence of E1-TEV (lane 2).

We purified all DNA-containing material by ion exchange chromatography, which removes all free protein to facilitate immunoprecipitations and TEV cleavage. This material was immunoprecipitated using a polyclonal antiserum raised against the E1 DBD, which recognizes the N-terminal half of the E1-TEV protein. As shown in Figure 6, the DNA–protein complex can be recovered and separated from the free probe (lane 4). After washing the beads, the immunoprecipitate was divided into two portions. One half was digested with TEV protease (lanes 5 and 6), while the other portion was mock digested (lanes 3 and 4). After digestion, the supernatant and the beads were separated and analyzed by SDS–PAGE. Digestion with TEV resulted in the release of the majority of the labeled DNA from the beads in a faster migrating band, indicating that the C-terminal half of E1 is associated exclusively with the labeled DNA (compare lanes 4 and 5). After a mock digestion, the intact full-length E1 was still associated with the antibody beads (compare lanes 3 and 4). These results demonstrate that the C-terminal half of the E1 protein, which includes the helicase domain, associates with the sequences flanking the E1-binding site.

We performed DNase footprinting experiments with E1 mutants lacking the sequences either N- or C-terminal to the DBD to verify that the presence of the E1 helicase domain is required for flanking protections. The protein lacking the N-terminal domain produced the extended footprint while the C-terminal truncation produced a footprint indistinguishable from the footprint generated by the E1 DBD (data not shown). These results indicate that the presence of the C-terminal helicase domain is required for formation of the extended footprint and that the presence of the N-terminal domain is not required.

Discussion

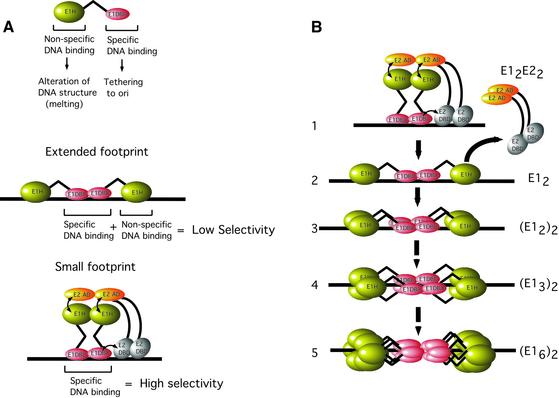

The results reported here provide many new insights into DNA replication initiator function. We demonstrate that the low DNA binding selectivity observed for the E1 initiator is not intrinsic to the E1 DBD, but rather is caused by a non-specific DNA-binding activity present in the E1 helicase domain, which masks specific binding by the E1 DBD. We also understand how the low selectivity is switched to high selectivity by the E2 auxiliary factor. The E2 AD interacts physically with the E1 helicase domain and prevents its non-specific binding. The net effect is to unmask the selectivity of the E1 DBD. These results provide a basis for understanding important aspects of formation of initiator complexes, such as how selectivity is generated (Figure 7A).

Fig. 7. (A) A summary of the dual DNA-binding activities in E1 and the consequences for DNA binding specificity. The E1 initiator encodes two distinct DNA-binding activities. A highly specific DNA-binding activity is present in the E1 DBD. This activity is responsible for recognition and tethering of E1 to the ori. The second DNA-binding activity is present in the helicase domain of E1, binds DNA with low specificity and is required for melting of the sequences flanking the E1-binding site. In the absence of E2, the non-specific DNA-binding activity masks the specificity of the E1 DBD, resulting in a net low selectivity for E1 DNA binding. In the presence of E2, however, the interaction between the E2 AD and the E1 helicase domain (E1H) inactivates the non-specific DNA-binding activity, resulting in unmasking of the intrinsic specificity of the E1 DBD. The extended footprint forms by binding of the E1 DBD with high specificity to the E1-binding sites, and simultaneous binding of the E1 helicase domain with low specificity to the flanking sequences. In the small footprint, DNA contacts are generated by the E1 DBD only. (B) A model for the assembly of E1 monomers to form a double hexamer. See text for details.

The non-specific DNA-binding activity places the E1 helicase domain in contact with DNA on the flanks of the E1-binding sites, coinciding precisely with the sequences where melting of the template is first detected (Gillette et al., 1994; Sanders and Stenlund, 2000). Melting activity is also associated with other initiator proteins, and therefore it is plausible that the non-specific DNA-binding activity is a general property of initiator proteins. To make this argument, the limited selectivity that we observe for E1 would have to apply also to other viral initiators. Papillomavirus DNA replication shows very distinctive similarities to SV40 replication, and the structural similarities between the DBDs in these two proteins indicate that T-ag and E1 are highly related (Luo et al., 1996; Enemark et al., 2000). It has been recognized that DNA-binding activities other than those accounted for by the DBD may exist in SV40 T-ag, but the nature and function of those activities, as well as their precise location, have been difficult to determine (Lin et al., 1992). However, previous footprinting experiments with T-ag generally are consistent with the manner of DNA binding that we propose for E1 (SenGupta and Borowiec, 1994). Although measurements of selectivity have not been performed with SV40 T-ag, such experiments have been performed with T-ag from the close relative polyomavirus (Py) (Lorimer et al., 1991). These studies indicated that Py T-ag has a low selectivity for ori binding similar to that of E1 (∼100-fold preference for ori), consistent with a need for an increase in selectivity to function efficiently in vivo in the presence of the vast excess of host genomic DNA.

How could such an increase in specificity come about? A comparison of the ori structures of papillomaviruses and SV40 reveals a similar organization but, in place of the palindromic E2-binding site that is present in the papillomavirus ori, SV40 contains a sequence termed the early palindrome (EP) which is essential for replication (Deb et al., 1986). This sequence may be the binding site for a hitherto unidentified factor of cellular origin that performs a function for T-ag binding similar to that which E2 does for E1 binding. A consequence of highly selective binding by an initiator is that recognition of an ori can be achieved at very low levels of the initiator, while, with a low level of selectivity, high levels of the initiator are required. In cell lines replicating the BPV genome (where both E1 and E2 are present), levels of E1 are extremely low, consistent with a high degree of selectivity (Thorner et al., 1993; Voitenleitner and Botchan, 2002). Interestingly, some cell lines allow very efficient SV40 replication in spite of very low levels of T-ag (293 cells), indicating a high level of specificity, while in other cell lines (CV-1) very high levels of T-ag are required for replication, indicative of low specificity (Lebkowski et al., 1985). These results are consistent with the presence or absence (or different levels) of a host-encoded selectivity factor that can bind to the EP in these different cell lines.

If initiator proteins in general have an intrinsic, non-specific DNA-binding activity in addition to a specific DNA-binding activity, overall low selectivity for recognition of a binding site is expected to result. Indeed, both S.cerevisiae and S.pombe ORCs appear to have substantial non-specific DNA binding activities which may explain their modest selectivity (Rao and Stillman, 1995; Kong and DePamphilis, 2001; Chuang et al., 2002). For ORCs from higher organisms, few biochemical data is available; however, in Xenopus egg extracts where ORC levels are very high, little or no selectivity is observed for initiation (Coverley and Laskey, 1994). This behavior is reminiscent of the behavior of E1 in the absence of E2; at very high E1 concentrations, replication is initiated with little specificity (Yang et al., 1993; Sedman and Stenlund, 1995). Any protein that encodes both a specific and a non-specific DNA-binding activity is expected to be subject to the same conflict as E1, i.e. a non-specific activity would mask the specific DNA-binding activity. How this problem is circumvented could differ in details, but that the non-specific activity has to be suppressed to achieve specific binding would seem to be universally true. Interactions with other proteins could perform this function, but virtually any signal that could block non-specific DNA binding could serve such a purpose, including modification (such as phosphorylation) of a DNA-binding surface.

The high degree of selectivity for binding by the E1 DBD was unexpected. The detailed biochemical, mutational and structural analyses of E1 DBD binding that have previously been performed have shown little indication of the properties that usually are associated with highly selective binding, i.e. a high degree of DNA sequence dependence (Sedman et al., 1997; Chen and Stenlund, 1998, 2001). On the contrary, our previous studies show a consistent picture of modest sequence dependence. Extensive mutational analysis of the 6 bp ATTGTT E1-binding site has shown that only in one position is there an absolute requirement for a particular base (T2) and, in most of the other positions, any base change results in at most 2- to 3-fold effects on binding (Chen and Stenlund, 2001). This observation indicates that very few base-specific contacts are made between E1 DBD and the DNA. These biochemical observations are confirmed by a recent co-crystal structure of the E1 DBD bound to its binding site (Enemark et al., 2002). The majority of the base interactions are with the one conserved base (T2) in the site, and the majority of the DNA–protein contacts are generic DNA contacts such as phosphate interactions.

Thus, we do not completely understand the basis for the high selectivity, but it is likely that structural determinants in the DNA are responsible. With the exception of S.cerevisiae ORC (Bell and Stillman, 1992), it has proven difficult so far to define binding sites for cellular initiator proteins. A prominent contribution from DNA structure in the recognition would be consistent with these difficulties since similarities in structure of DNA are not readily detected as similarities in sequence. Thus, the difficulty in defining consensus binding sites for other ORC proteins (such as S.pombe ORC) is not necessarily an indication that these proteins lack the ability to bind DNA in a highly selective manner.

We can now provide a view of how basic viral initiator complexes are assembled based on our understanding of how E1 and E2 bind to the ori (Figure 7B). The E1 and E2 proteins bind together to adjacent binding sites, forming an E12E22 complex. In this complex, due to the contact between the E1 helicase domain and the E2 AD, E1 is contacting DNA exclusively via the E1 DBD and, consequently, is capable of highly specific DNA binding. As E2 is displaced, the DBD and helicase domains in E1 make simultaneous contact with the DNA. The E1 DBD is bound to paired E1-binding sites and the helicase domains contact flanking sequences on both sides of the E1-binding sites (step 2). We have demonstrated binding of up to four E1 molecules (E12)2 utilizing the four overlapping E1-binding sites that are present in ori (step 3; Chen and Stenlund, 2002), but only indirect evidence exists for the binding of a third pair of E1 molecules (step 4): trimeric rings of E1 topologically linked to ori DNA can be detected after cross-linking (Sedman and Stenlund, 1996). Binding in this manner invites comparison with the recent electron microscopic images that show SV40 T-ag as a dumbbell-shaped dodecamer with the DBDs in the center and the C-terminus (helicase domain) to the outside (Valle et al., 2000; VanLoock et al., 2002). These images of the dodecamer (‘double hexamer’) allow us to propose a very simple model for the assembly of larger E1 complexes. Starting from a dimer of E1 bound as described above (step 2), simple addition of dimers of E1 in sequence, with the same orientation and arrangement as the first pair, would suffice to generate such a structure. Certainly, no drastic rearrangement or remodeling of E1 molecules would seem to be necessary for this process.

This model explains some features of initiators such as the required transition from site-specific binding to the non-specific binding by the E1 helicase. As assembly proceeds beyond the binding of four E1 molecules, no further specific DNA contacts via the DBD can be accommodated since additional sites are not present, which limits the contribution that specific DNA contacts can bring to complex formation. However, as more molecules are added, non-specific contacts between the helicase domain and DNA, beyond the binding of four molecules, may be possible. As assembly proceeds, this would result in a gradual change of DNA binding properties from a largely specific form required for ori recognition, to a largely non-specific form appropriate for DNA melting and non-specific helicase activity, without a requirement for subunit rearrangement.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification of E1 and E2 proteins

Expression and purification of full-length E1 and E2, and the DBDs of the E1 and E2 proteins have been described previously (Sedman et al., 1997; Chen and Stenlund, 1998, 2000). Briefly, full-length E1 (amino acids 1–605) and the E1 DBD (amino acids 142–308) were expressed as GST fusions in E.coli and isolated by glutathione–agarose affinity chromatography. After isolation of the fusion proteins, the GST portion was removed by thrombin digestion and the material further purified by Mono S ion exchange chromatography. Full-length E2 (amino acids 1–410) and the E2 DBD (amino acids 323–410) were expressed in E.coli without tags and purified by successive Mono S and Mono Q ion exchange chromatography. All proteins were purified to apparent homogeneity.

DNase footprints

DNase footprints were carried out as described previously (Sedman et al., 1997). Proteins and probe (30 000 c.p.m.) were incubated at room temperature in binding buffer [20 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.4, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mM EDTA, 0.7 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% NP-40 and 5% glycerol] in a final volume of 10 µl. After 20 min, 10 µl of a solution containing 5 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM MgCl2 was added together with 1 µl of DNase I. After 60 s, cleavage was terminated by the addition of 130 µl of STOP solution (0.2 M NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% SDS) followed by phenol/chloroform extraction. The aqueous phase was precipitated by the addition of 350 µl of 0.45 M ammonium acetate in ethanol. When competitor DNA was used, it was added together with the probe prior to addition of the protein.

EMSA

Binding reactions containing 5000 c.p.m. of probe were assembled in binding buffer (see above) and loaded onto a native 6% polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide:bis 80:1) in 0.5× Tris-borate EDTA. The gel was pre-electrophoresed overnight and the samples were run at 150 V for 4 h.

OP-Cu footprinting

OP-Cu footprinting was carried out as described (Sigman et al., 1991). Binding reactions were assembled as described for DNase footprinting reactions above except that 100 000 c.p.m. of probe was used. A 1 µl aliquot of a solution containing 10 mM orthophenatroline (OP) and 2.4 mM CuSO4, and 1 µl of 58 mM mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) were added to the binding reactions in 10 µl of binding buffer. After 1 min at room temperature, the cleavage was terminated by the addition of 1 µl of 28 mM dimethylorthophenatroline (DMOP). After addition of STOP solution, the samples were treated as described above for DNase footprinting. The relatively high concentrations of reagents used in these experiments were necessary to generate sufficient cleavage in the presence of 1 mM DTT, which is required for efficient cooperative complex formation.

In-gel Op-Cu footprinting

Binding reactions were scaled up 20-fold relative to the reactions shown in Figure 4. After electrophoresis, the gel was immediately immersed in 1 l of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0. A 50 ml aliquot of a solution containing 0.9 mM CuSO4 and 4 mM OP was added, followed by 50 ml of 1% MPA. After 3.5 min, 50 ml of 56 mM DMOP was added and incubation was continued for another 3 min. After exposure to a Fuji imaging plate, the bands were excised, eluted by diffusion, precipitated and analyzed on sequencing gels.

UV cross-linking

UV cross-linking experiments were based on previous procedures (Yang and Nash, 1994). The templates for UV cross-linking were generated by the synthesis of an 18mer oligonucleotide with three phosphorothioate linkages between positions 4 and 5, 7 and 8, and 10 and 11 in the primer. This primer was reacted with 5 mM azidophenacyl bromide in 20 mM sodium bicarbonate pH 9.1 containing 50% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). All subsequent steps were carried out with subdued lighting. After reaction for 1 h at room temperature, the azidophenacyl bromide was removed by repeated extractions with butanol. The level of modification was assessed by analysis of a small radiolabeled sample by electrophoresis on a 20% acrylamide–urea sequencing gel. Each added aryl azide results in a mobility reduction, roughly equivalent to one added nucleotide. The modified oligonucleotide was utilized for 20 PCR cycles using a 32P-labeled universal primer (RSP) and the minimal ori cloned in pUC19 as the template. The radiolabeled PCR fragment was purified by PAGE and eluted. The probe was used to bind E1 protein with a TEV protease cleavage site engineered between the DBD and the helicase domain in a solution containing 20 mM KPO4 pH 7.4, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 0.1% NP-40. After 30 min at room temperature, the sample was exposed to UV light (350 mJ/cm2) at 312 nm. After cross-linking, urea was added to 2 M, the concentration NaCl was adjusted to 0.5 M, and the pH was adjusted to 6.1 by the addition of phosphate buffer pH 6.1 to 40 mM. The sample was passed over a 0.04 ml Q-Sepharose column, and washed with 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.1, 2 M urea, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1% NP-40 and 5% glycerol. Bound material was eluted with 20 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.1, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol. Under these conditions, free protein is removed and only DNA-containing material is recovered. The mixture of free probe and cross-linked material was diluted 10-fold in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% SDS, and immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal antiserum directed against the E1 DBD (amino acids 159–303), coupled to protein G beads. After successive washes with TBS + 0.1% SDS, TBS and 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, the sample was divided into two portions. To one portion, 2 U of TEV protease was added, while the other portion received no enzyme. After 1 h at 30°C, the supernatant and pellets were separated and analyzed by SDS–PAGE.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank W.Herr and K.Fien for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by Public Health Service grant CA 13106 from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- Aurora R. and Herr,W. (1992) Segments of the POU domain influence one another’s DNA binding specificity. Mol. Cell. Biol., 12, 455–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S.P. (2002) The origin recognition complex: from simple origins to complex functions. Genes Dev., 16, 659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell S.P. and Stillman,B. (1992) ATP-dependent recognition of eukaryotic origins of DNA replication by a multiprotein complex. Nature, 357, 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M. and Stenlund,A. (1997) Functional interactions between papillomavirus E1 and E2 proteins. J. Virol., 71, 3853–3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. and Stenlund,A. (1998) Characterization of the DNA-binding domain of the bovine papillomavirus replication initiator E1. J. Virol., 72, 2567–2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. and Stenlund,A. (2000) Two patches of amino acids on the E2 DNA binding domain define the surface for interaction with E1. J. Virol., 74, 1506–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. and Stenlund,A. (2001) The E1 initiator recognizes multiple overlapping sites in the papillomavirus origin of DNA replication. J. Virol., 75, 292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. and Stenlund,A. (2002) Sequential and ordered assembly of E1 initiator complexes on the papillomavirus origin of DNA replication generates progressive structural changes related to melting. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 7712–7720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang R.Y., Chretien,L., Dai,J. and Kelly,T.J. (2002) Purification and characterization of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe origin recognition complex: interaction with origin DNA and Cdc18 protein. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 16920–16927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coverley D. and Laskey,R.A. (1994) Regulation of eukaryotic DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 63, 745–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb S., DeLucia,A.L., Baur,C.P., Koff,A. and Tegtmeyer,P. (1986) Domain structure of the simian virus 40 core origin of replication. Mol. Cell. Biol., 6, 1663–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enemark E.J., Chen,G., Vaughn,D.E., Stenlund,A. and Joshua-Tor,L. (2000) Crystal structure of the DNA binding domain of the replication initiation protein E1 from papillomavirus. Mol. Cell, 6, 149–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enemark E.J., Stenlund,A. and Joshua-Tor,L. (2002) Crystal structures of two intermediates in the assembly of the papillomavirus replication initiation complex. EMBO J., 21, 1487–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanning E. and Knippers,R. (1992) Structure and function of simian virus 40 large tumor antigen. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 61, 55–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M.K. and Botchan,M.R. (1996) Genetic analysis of the activation domain of bovine papillomavirus protein E2: its role in transcription and replication. J. Virol., 70, 4193–4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillette T.G., Lusky,M. and Borowiec,J.A. (1994) Induction of structural changes in the bovine papillomavirus type 1 origin of replication by the viral E1 and E2 proteins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 8846–8850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillitzer E., Chen,G. and Stenlund,A. (2000) Separate domains in E1 and E2 proteins serve architectural and productive roles for cooperative DNA binding. EMBO J., 19, 3069–3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.D., Poteete,A.R., Lauer,G., Sauer,R.T., Ackers,G.K. and Ptashne,M. (1981) λ repressor and cro—components of an efficient molecular switch. Nature, 294, 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D. and DePamphilis,M.L. (2001) Site-specific DNA binding of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe origin recognition complex is determined by the Orc4 subunit. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 8095–8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebkowski J.S., Clancy,S. and Calos,M.P. (1985) Simian virus 40 replication in adenovirus-transformed human cells antagonizes gene expression. Nature, 317, 169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.K., Moon,K.Y., Jiang,Y. and Hurwitz,J. (2001) The Schizosaccharomyces pombe origin recognition complex interacts with multiple AT-rich regions of the replication origin DNA by means of the AT-hook domains of the spOrc4 protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 13589–13594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.J., Upson,R.H. and Simmons,D.T. (1992) Nonspecific DNA binding activity of simian virus 40 large T antigen: evidence for the cooperation of two regions for full activity. J. Virol., 66, 5443–5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer H.E., Wang,E.H. and Prives,C. (1991) The DNA-binding properties of polyomavirus large T antigen are altered by ATP and other nucleotides. J. Virol., 65, 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X., Sanford,D.G., Bullock,P.A. and Bachovchin,W.W. (1996) Solution structure of the origin DNA-binding domain of SV40 T-antigen. Nat. Struct. Biol., 3, 1034–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusky M., Hurwitz,J. and Seo,Y.S. (1994) The bovine papillomavirus E2 protein modulates the assembly of but is not stably maintained in a replication-competent multimeric E1–replication origin complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 8895–8899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masterson P.J., Stanley,M.A., Lewis,A.P. and Romanos,M.A. (1998) A C-terminal helicase domain of the human papillomavirus E1 protein binds E2 and the DNA polymerase α-primase p68 subunit. J. Virol., 72, 7407–7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr I.J., Clark,R., Sun,S. androphy,E.J., MacPherson,P. and Botchan,M.R. (1990) Targeting the E1 replication protein to the papillomavirus origin of replication by complex formation with the E2 transactivator. Science, 250, 1694–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao H. and Stillman,B. (1995) The origin recognition complex interacts with a bipartite DNA binding site within yeast replicators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 92, 2224–2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C.M. and Stenlund,A. (1998) Recruitment and loading of the E1 initiator protein: an ATP-dependent process catalysed by a transcription factor. EMBO J., 17, 7044–7055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C.M. and Stenlund,A. (2000) Transcription factor-dependent loading of the E1 initiator reveals modular assembly of the papillomavirus origin melting complex. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 3522–3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedman J. and Stenlund,A. (1995) Co-operative interaction between the initiator E1 and the transcriptional activator E2 is required for replicator specific DNA replication of bovine papillomavirus in vivo and in vitro. EMBO J., 14, 6218–6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedman J. and Stenlund,A. (1996) The initiator protein E1 binds to the bovine papillomavirus origin of replication as a trimeric ring-like structure. EMBO J., 15, 5085–5092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedman T., Sedman,J. and Stenlund,A. (1997) Binding of the E1 and E2 proteins to the origin of replication of bovine papillomavirus. J. Virol., 71, 2887–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SenGupta D.J. and Borowiec,J.A. (1994) Strand and face: the topography of interactions between the SV40 origin of replication and T-antigen during the initiation of replication. EMBO J., 13, 982–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigman D.S., Kuwabara,M.D., Chen,C.H. and Bruice,T.W. (1991) Nuclease activity of 1,10-phenanthroline-copper in study of protein–DNA interactions. Methods Enzymol., 208, 414–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sverdrup F. and Myers,G. (1997) The E1 proteins. In Myers,C.B.G., Munger,K., Sverdup,F., McBride,A. and Bernard,H.-U. (eds), Human Papillomaviruses. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM, pp. 37–53.

- Thorner L.K., Lim,D.A. and Botchan,M.R. (1993) DNA-binding domain of bovine papillomavirus type 1 E1 helicase: structural and functional aspects. J. Virol., 67, 6000–6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titolo S., Pelletier,A., Sauve,F., Brault,K., Wardrop,E., White,P.W., Amin,A., Cordingley,M.G. and Archambault,J. (1999) Role of the ATP-binding domain of the human papillomavirus type 11 E1 helicase in E2-dependent binding to the origin. J. Virol., 73, 5282–5293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle M., Gruss,C., Halmer,L., Carazo,J.M. and Donate,L.E. (2000) Large T-antigen double hexamers imaged at the simian virus 40 origin of replication. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanLoock M.S., Alexandrov,A., Yu,X., Cozzarelli,N.R. and Egelman,E.H. (2002) SV40 large T antigen hexamer structure. Domain organization and DNA-induced conformational changes. Curr. Biol., 12, 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voitenleitner C. and Botchan,M. (2002) E1 protein of bovine papillomavirus type 1 interferes with E2 protein-mediated tethering of the viral DNA to mitotic chromosomes. J. Virol., 76, 3440–3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Mohr,I., Li,R., Nottoli,T., Sun,S. and Botchan,M. (1991) Transcription factor E2 regulates BPV-1 DNA replication in vitro by direct protein–protein interaction. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol., 56, 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Mohr,I., Fouts,E., Lim,D.A., Nohaile,M. and Botchan,M. (1993) The E1 protein of bovine papilloma virus 1 is an ATP-dependent DNA helicase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 5086–5090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.-W. and Nash,H.A. (1994) Specific photocrosslinking of DNA–protein complexes: identification of contacts between integration host factor and its target DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 12183–12187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]