Abstract

SC35 belongs to the family of SR proteins that regulate alternative splicing in a concentration-dependent manner in vitro and in vivo. We previously reported that SC35 is expressed through alternatively spliced mRNAs with differing 3′ untranslated sequences and stabilities. Here, we show that overexpression of SC35 in HeLa cells results in a significant decrease of endogenous SC35 mRNA levels along with changes in the relative abundance of SC35 alternatively spliced mRNAs. Remarkably, SC35 leads to both an exon inclusion and an intron excision in the 3′ untranslated region of its mRNAs. In vitro splicing experiments performed with recombinant SR proteins demonstrate that SC35, but not ASF/SF2 or 9G8, specifically activates these alternative splicing events. Interestingly, the resulting mRNA is very unstable and we present evidence that mRNA surveillance is likely to be involved in this instability. SC35 therefore constitutes the first example of a splicing factor that controls its own expression through activation of splicing events leading to expression of unstable mRNA.

Keywords: alternative splicing/autoregulation/mRNA stability/SC35

Introduction

Alternative splicing, allowing the formation of different mRNA isoforms from a single gene, is a fundamental process controlling genetic expression in higher eukaryotes. Among the different factors involved in the regulation of alternative splicing, one group of non-snRNP proteins belongs to a conserved family of structurally and functionally related phosphoproteins called SR proteins (for review see Fu, 1995; Manley and Tacke, 1996; Graveley, 2000). SR proteins exhibit a modular structure consisting of one or two RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) and a C-terminal domain of variable length (the RS domain), rich in Arg and Ser residues. Whereas the RS domain is responsible for specific protein–protein interactions, the RRM domain binds to many different sites along the RNA and is involved in specific interactions with sequences, known as exonic (ESE) or intronic splicing enhancers (ISE), identified in numerous pre-mRNAs (for reviews see Tacke and Manley, 1999; Graveley, 2000).

Several studies have reported that SR proteins, which are involved in the early steps of spliceosome assembly, promote binding of the U1 snRNP to the 5′ splice site and stimulate binding of U2AF and the U2 snRNP to the 3′ splice site region (Reed, 1996 and references therein). Since the RS domains of SR factors interact with themselves and with each other, as well as with the U1-70K and U2AF35 proteins, it has been proposed that a role of SR proteins consists of bringing the 5′ and 3′ splice sites together via a bridge of protein contacts (for review see Graveley, 2000). In addition to their role in constitutive splicing, SR proteins also influence the selection of alternative splice sites in a concentration-dependent manner both in vitro and in transfected cells (for review see Smith and Valcarcel, 2000). For some, if not all SR proteins, this activity can be antagonized by members of the hnRNP A/B family (Fu and Maniatis, 1992; Caceres et al., 1994; Mayeda et al., 1994 and references therein), as well as by other SR factors (Gallego et al., 1997; Jumaa and Nielsen, 1997). This indicates that accurate splice site selection depends on the relative concentrations of SR proteins and antagonist factors. Along this line, depletion of the ASF/SF2 and B52/SRp55 splicing factors in chicken B cells and in Drosophila, respectively, were shown to affect splicing of specific transcripts in vivo (Wang et al., 1998; Hoffman and Lis, 2000).

Increasing the expression level of SR proteins also interferes with developmental processes in different organisms. Transgenic plants overexpressing atSRp30 showed morphological and developmental changes (Lopato et al., 1999), and overexpression of B52/SRp55 in Drosophila resulted in developmental defects (Kraus and Lis, 1994), which can be rescued, at least in part, by concomitant overexpression of the splicing repressor RSF1 (Labourier et al., 1999). Taken together, these observations indicate that the regulation of the expression levels of SR proteins and their antagonists is crucial in controlling tissue-specific or developmentally regulated alternative splicing events. Along this line, significant tissue- and cell line-specific variations in mRNA coding for SR proteins or SR protein levels have been described (Fu and Maniatis, 1992; Vellard et al., 1992; Screaton et al., 1995; Hanamura et al., 1998; Lopato et al., 1999). However, little is known about the mechanisms involved in the regulation of SR protein expression. A striking feature of most SR protein genes is that they express alternative mRNAs encoding truncated proteins whose biological roles remain to be established (Ge et al., 1991; Popielarz et al., 1995; Screaton et al., 1995).

Here, we report that SC35 overexpression leads to a pronounced decrease of its endogenous mRNA levels in HeLa cells. Moreover, SC35 accumulation is also correlated to changes in the splicing pattern of its own mRNAs. Analysis of SC35 mRNAs in overexpressing cells indicates that these changes essentially result from activation of both a cassette exon inclusion and a retained intron splicing in the 3′ untranslated sequences of SC35 messengers. Using in vitro splicing experiments and purified recombinant SR proteins, we establish that SC35 directly and specifically activates these two alternative splicing events. Interestingly, we have determined that the corresponding SC35 mRNA isoform exhibits a very low stability in HeLa cells, most likely due to mRNA surveillance. These observations indicate that SC35 autoregulates its expression by promoting alternative splicing events altering the stability of its own mRNAs.

Results

SC35 overexpression results in alteration of its own mRNA splicing pattern and in the downregulation of corresponding endogenous expression

To determine whether expression levels and/or the splicing pattern of SC35 mRNAs could be affected in response to SC35 accumulation, HeLa Tet-On cells (Gossen et al., 1995) were co-transfected with the pUHD-HA-SC35 inducible expression vector containing the SC35 cDNA sequences fused to the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope sequence (Figure 1) and a hygromycin selection plasmid. Total RNA purified from ∼50 hygromycin-resistant clones cultured for 48 h in the presence of doxycyclin (Dox) was analyzed by slot-blot hybridization with an HA-specific probe (data not shown), and clones exhibiting the higher expression levels were selected. In these clones, cell growth and viability are not affected in response to SC35 overexpression (see Supplementary data, available at The EMBO Journal Online).

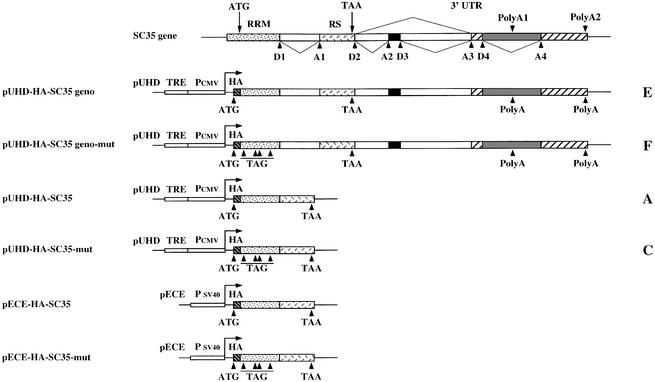

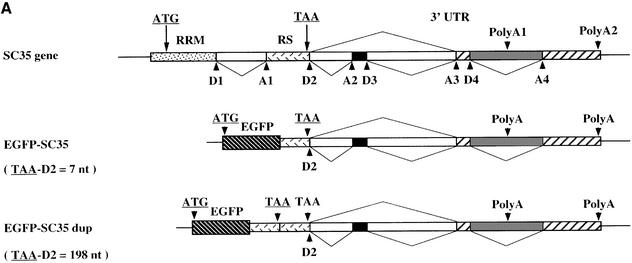

Fig. 1. Structure of the SC35-inducible and constitutive expression vectors. Top: overall organization of the human SC35 gene. The different donor (D) and acceptor (A) splice sites as well as alternative polyadenylation sites are indicated. The two first exons encoding the SC35 RRM and RS domains are shown. Alternative splicing events occurring in the 3′UTR are represented. In the pUHD inducible vectors, the tetracyclin-transactivator responsive element (TRE), the minimal CMV promoter (PCMV) and the HA tag (HA) are indicated. In the pECE vector, SC35 expression is driven by SV40 promoter sequences (PSV40). In non-coding versions of the vectors, the in-frame ATG codons mutated into stop codons are indicated by arrowheads and TAG. The capital letter at the right of each vector corresponds to the general name of HeLa cell clones isolated following transfection with this construct.

Time course analysis of Dox-induced SC35 expression was performed in different clones at both the RNA and protein levels with an oligonucleotide probe and a monoclonal antibody specific for the HA tag. For one (A10), SC35 exogenous mRNA and protein expression were progressively increased 18 h following Dox addition (Figure 2A). Analysis of the same northern blot with a probe specific for 5′ untranslated sequences of endogenous, but not exogenous SC35 mRNAs also revealed that expression of endogenous SC35 sequences is affected by SC35 overexpression. Among the three mRNA isoforms (3.0, 2.0 and 1.3 kb) revealed below the 28S rRNA band, the expression level of the major 2.0 and 1.3 kb SC35 mRNAs was slightly increased 6 h following Dox induction, for unclear reasons. However, from 48 to 96 h after induction, the expression levels of the 2.0 and 1.3 kb mRNAs were reduced by ∼75%, an observation confirmed by semi-quantitative RT–PCR analyses (data not shown). Western blot analyses performed with an anti-SC35 antibody also revealed that expression of the endogenous SC35 protein is markedly reduced after 4 days of Dox induction (Supplementary data). Similar studies performed in HeLa Tet-On cells transfected with a non-coding SC35 expression vector (pUHD-HA-SC35-mut, Figure 1) allowed us to establish that the downregulation of endogenous SC35 expression products results from the accumulation of SC35 protein. Indeed, no decrease of the endogenous SC35 mRNA levels was detected in different clones (C9 and C28) overexpressing non-coding SC35 cDNA sequences (Figure 2A). Together, these observations strongly suggested the existence of a negative feedback loop leading to the downregulation of SC35 expression in response to accumulation of this splicing factor.

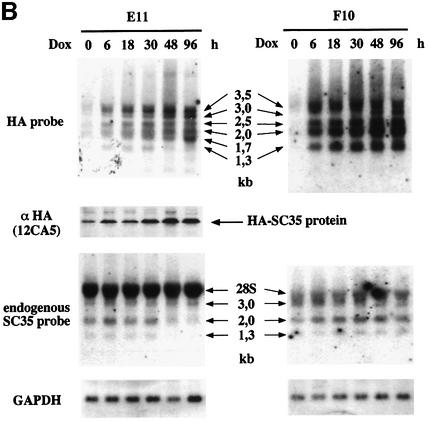

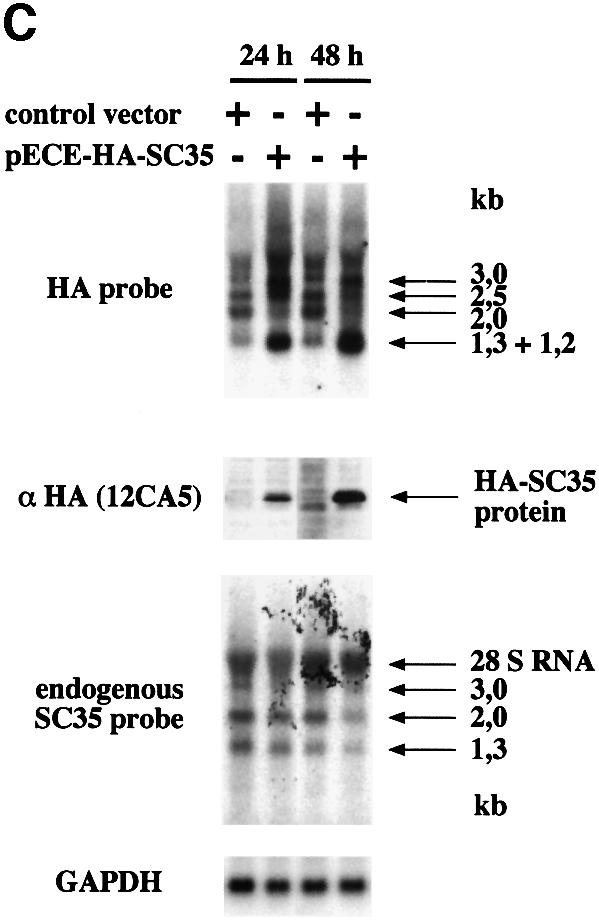

Fig. 2. Northern and western blot analysis of SC35 exogenous and endogenous products in HeLa cells. (A) Analysis of SC35 expression products in HeLa cell clones stably transfected with coding (A10) or non-coding (C9 and C28) HA-tagged SC35 cDNA sequences. (B) Analysis of SC35 expression products in HeLa cell clones stably transfected with coding (E11) or non-coding (F10) HA-tagged SC35 genomic sequences. Total RNA (20 µg/lane) purified from HeLa cell clones at different times (in hours) following doxycyclin (Dox) induction was analyzed by northern blot hybridization with the HA probe specific for exogenous transcripts or with the SC35 leader probe specific for endogenous mRNAs. The size of the different SC35 mRNAs is mentioned. The 28S rRNA detected by the SC35 leader probe is indicated. Hybridization with a GAPDH-specific probe was performed to normalize for RNA amounts and transfer efficiency. Protein samples (30 µg/lane) purified from the same cells were analyzed by western blotting with the 12CA5 monoclonal antibody specific for the HA tag. (C) Analysis of SC35 expression products in F3 cells expressing non-coding HA-tagged SC35 genomic sequences and transiently transfected with either the control or pECE-HA-SC35 vector driving constitutive expression of a 1.2 kb SC35 mRNA. Northern and western blot analyses were performed as above at the indicated times following transient transfection.

To analyze the mechanism underlying this downregulation, we first tested whether the overall pattern of SC35 mRNAs was altered upon SC35 overexpression. HeLa Tet-On cells were stably transfected with either the pUHD-HA-SC35 geno vector containing the entire SC35 genomic sequence fused to the HA tag or the non-coding version (geno-mut, Figure 1). Following Dox induction, time course analysis of the exogenous SC35 mRNA splicing pattern was performed in clones expressing either coding (E11) or non-coding (F10) genomic sequences (Figure 2B). Four major mRNAs, ranging from 1.3 to 3.5 kb in size, accumulated in cells overexpressing SC35 non-coding sequences (F10 cells). A 3.0 kb mRNA was also revealed by the HA-specific probe 48 and 96 h after induction. The 1.3, 2.0 and 3.0 kb exogenous mRNAs are likely to correspond to the same endogenous species (whose structure is depicted in Figure 3) that are detected in all cell lines and tissues tested thus far (Vellard et al., 1992; Sureau and Perbal, 1994). Given that the expression vector contains an SV40 polyadenylation site 400 nucleotides (nt) downstream of the SC35 authentic polyadenylation site, the 2.5 and 3.5 kb mRNA could correspond to versions of the 2.0 and 3.0 kb mRNAs ending at the more distal site. This was confirmed by northern blot and RT–PCR analyses performed with a probe specific for the SV40 polyadenylation sequences (data not shown). These results indicate that the expression pattern revealed in F10 cells expressing non-coding SC35 sequences is very similar to that of the endogenous SC35 gene.

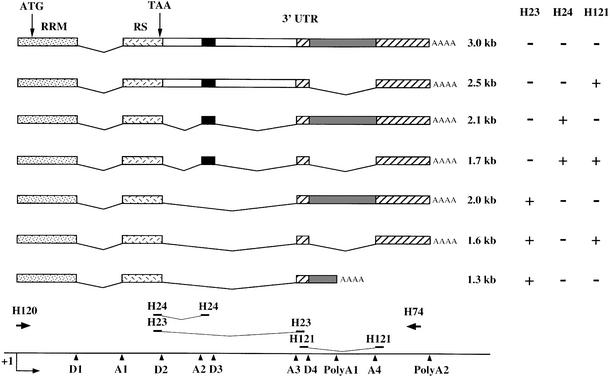

Fig. 3. Schematic structure of the SC35 transcripts. The features of the SC35 gene are indicated as in Figure 1. For the various mRNA isoforms, whose size is indicated on the right, exons are represented by boxes and excised introns by lines. The positions of the different oligonucleotides used for PCR or Southern blot analysis of RT–PCR products (Figure 4) are indicated at the bottom. The specificity of the oligonucleotidic probes for the different SC35 mRNAs is indicated on the right.

A significantly different expression pattern was observed in HeLa cells expressing exogenous SC35 genomic coding sequences (E11 cells, Figure 2B). An additional 1.7 kb mRNA was revealed with the HA-specific probe and the relative expression levels of the 1.7, 2.0–2.5 and 3.0–3.5 kb mRNAs were quite similar from 6 to 30 h following Dox addition. At later points (48–96 h), we observed marked changes in the relative abundance of the various isoforms, with a particular increase of the 1.7 kb mRNA (Figure 2B). Western blot analysis revealed that the HA-tagged SC35 protein was expressed in these cells prior to Dox induction, which agrees with a weak signal detected by northern blot analysis (Figure 2B). The expression level of the exogenous SC35 protein was evenly increased up to 30–48 h following induction and remained unchanged thereafter. As before (Figure 2A), a significant downregulation of endogenous SC35 mRNA expression occurred in E11 cells transfected with coding genomic sequences, while no appreciable change was detected in F10 cells (Figure 2B).

We also established that the non-coding SC35 transcripts may undergo the same type of regulation, provided that SC35 protein is overexpressed concomitantly. In F3 cells transiently transfected with the pECE-HA-SC35 vector (Figure 1), SC35 overexpression led to an alteration of the exogenous non-coding SC35 mRNA expression pattern that was readily detectable at 24 h and even stronger 48 h after transfection, as exemplified by the dramatic decrease in the 2.0 kb mRNA (Figure 2C). Furthermore, the downregulation of the endogenous SC35 expression correlated with the accumulation of SC35 protein in these cells. Considering the role of SC35 in constitutive and alternative splicing, our observations were consistent with the idea that the downregulation of endogenous and exogenous SC35 transcripts is mediated, at least in part, by an alteration of their splicing pattern.

Two different splicing events are promoted in response to SC35 overexpression

Except for the 3.0 and 1.3 kb SC35 transcripts [unspliced in the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) and polyadenylated at the proximal poly(A) site, respectively], the various SC35 mRNAs arise via a combination of two splicing events (Figure 3). The 2.1 and 1.7 kb species differ from the 2.0 and 1.6 kb transcripts by the inclusion of a 104 nt cassette exon delineated by the A2–D3 splice sites. In addition, the 2.1 and 2.0 kb species differ from the 1.7 and 1.6 kb transcripts by the retention of a 498 nt intron delineated by the D4–A4 splice sites. To evaluate the relative levels of these mRNAs prior to and following induction of SC35 expression, we performed semi- quantitative RT–PCR experiments. Southern blot analysis of RT–PCR products was performed with the H23, H24 and H121 oligonucleotide probes specific for different exon–exon junction sequences of the 3′UTR (Figure 3) and that allow us to discriminate between the various alternative SC35 mRNAs.

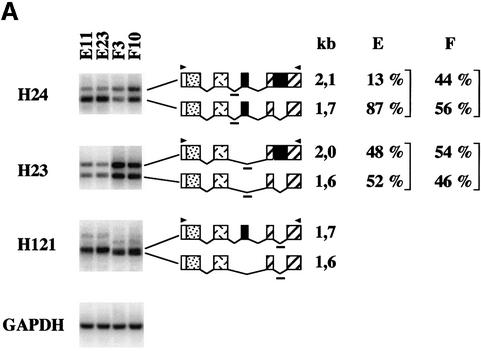

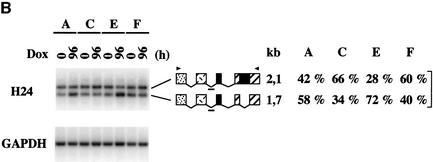

Analysis of exogenous SC35 transcripts from HeLa cells expressing coding (E11 and E23) or non-coding (F3 and F10) genomic sequences showed that inclusion of the 104 nt cassette exon and splicing of the 498 nt intron are concomitantly promoted in cells overexpressing the SC35 protein. The H24 probe revealed that the ratio of the expression levels of the 1.7 and 2.1 kb mRNAs, both containing the 104 nt cassette exon but differing by the splicing of the 498 nt intron, is significantly higher in E cells than in F cells (Figure 4A). Splicing of this intron appears to be related to the inclusion of the 104 nt cassette exon, since hybridization with the H23 probe (specific for mRNAs resulting from skipping of the cassette exon) indicated that the ratio of the 1.6 and 2.0 kb mRNA expression levels is only slightly increased upon induction of SC35 overexpression in E cells. Furthermore, both mRNAs appear to be 4- to 5-fold less abundant in E cells than in F cells, an observation that agrees with our northern blot analyses showing decreased expression of the major 2.0 kb mRNA in response to SC35 accumulation. The H121 probe showed that the ratio of the 1.7 and 1.6 kb mRNA expression levels in E cells is the reverse of that determined in F cells, confirming that inclusion of the cassette exon is stimulated in cells overexpressing SC35. Similar observations were obtained in HeLa cells overexpressing non-coding genomic sequences and transiently transfected with an SC35 constitutive expression vector (data not shown). We finally established that the expression pattern of endogenous SC35 mRNAs is affected similarly in HeLa cells expressing SC35 coding sequences (Figure 4B). Four days after Dox induction, the relative expression level of the 1.7 kb mRNA was clearly increased in cells stably transfected with coding cDNA (A) or genomic (E) SC35 sequences, as compared with that observed in uninduced cells or in cells expressing non-coding cDNA (C) or genomic (F) sequences. Altogether, northern blot and RT–PCR analyses demonstrate that the distribution of the various SC35 mRNAs is strongly affected in cells overexpressing SC35. In particular, the 1.7 kb mRNA, which differs from the 2.0 kb major species by both the retention of a 104 nt cassette exon and excision of a 498 nt intron, preferentially accumulates relative to other SC35 mRNAs.

Fig. 4. Southern blot analysis of RT–PCR products corresponding to exogenous and endogenous SC35 mRNAs expressed in HeLa cell clones. One-tenth of the PCR products corresponding to SC35 exogenous (A) or endogenous (B) mRNAs expressed in different HeLa cell clones were analyzed with the indicated probes. The structure and size of the transcripts corresponding to the PCR products are indicated and the positions of the PCR primers (arrowheads) and probes (short bold line) are shown. For each probe, the percentage of the hybridization signal corresponding to each PCR product was determined by PhosphorImager analysis for four independent clones of the same series and the mean values are indicated on the right. RT–PCR analysis of the GAPDH mRNA was performed to normalize for RNA amounts used in the RT step. (A) RT–PCR analysis of exogenous SC35 mRNAs from HeLa cell clones stably transfected with coding (E11 and E23) or non-coding (F3 and F10) SC35 genomic sequences and incubated for 48 h in the presence of Dox. (B) RT–PCR analysis of endogenous SC35 mRNAs expressed in HeLa cell clones stably transfected with coding cDNA (A), non-coding cDNA (C), coding genomic (E) or non-coding genomic (F) SC35 sequences prior to or 96 h after Dox induction.

SC35 specifically activates two splicing events in its own pre-mRNA in vitro

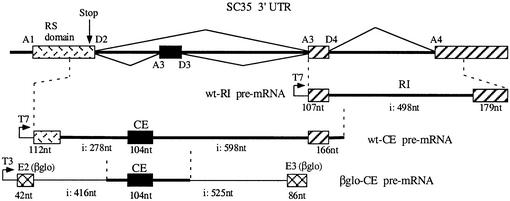

To eliminate the possibility of effects not directly mediated by SC35, we tested whether this splicing factor could recapitulate both the retention of the 104 nt cassette exon and the excision of the 498 nt intron in vitro. To this end, we generated three constructs (Figure 5): one containing the whole 498 nt intron flanked by its natural exons (wt-RI construct) and two others containing the 104 nt cassette exon. The first (wt-CE) corresponds to a wild-type 1249 bp fragment including the flanking whole introns and natural exons. The second (βglo-CE) contains a smaller portion (451 bp) of the SC35 gene including limited intronic sequences flanking the cassette exon, which was inserted in the middle of the intron separating exons 2 and 3 of the rabbit β globin gene. Consistent with the alternative splicing observed in vivo with both cassette exon and retained intron, these two elements are flanked by poor 5′ splice sites (only four successive bases matching with the consensus sequence) and suboptimal 3′ splice sites. In vitro assays were performed with standard HeLa nuclear extracts and the nature of the various splicing products was assessed by various criteria, such as abnormal electrophoretic behavior and debranching assays for lariat products, or RT–PCR analysis and sequencing of mRNA products. The results obtained with the different constructs showed that excision of the retained intron and inclusion of the cassette exon are highly and specifically activated by SC35 in vitro.

Fig. 5. Origin and schematic representation of the minigene constructs used in in vitro splicing analyses. The overall organization of the human SC35 gene is depicted and the different donor (D) and acceptor (A) splice sites are indicated. The β globin exon 2, exon 3 and intronic sequences represented in the βGlo-CE chimeric transcript are shown.

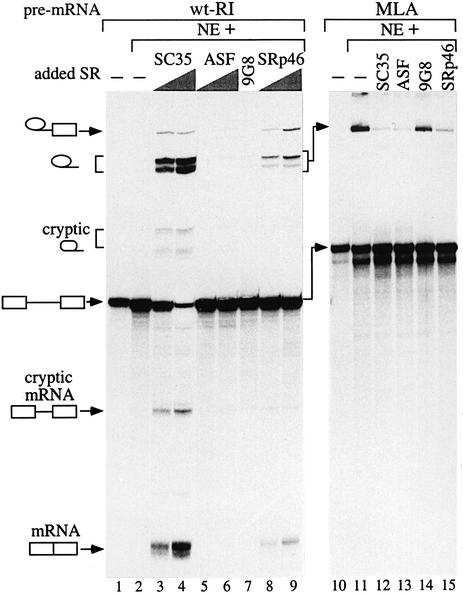

Due to weak splice sites, the wt-RI substrate was almost not spliced under standard splicing conditions (Figure 6, lane 2). However, when nuclear extracts were complemented with moderate amounts of SC35 (7–14 pmol), efficient splicing of the 498 nt intron (lanes 3 and 4) was observed. Moreover, a cryptic 5′ splice site (AG/GTAAAA), located 157 nt downstream of the bona fide 5′ splice site, was activated. These are specific for SC35, since complementation of the nuclear extract with ASF/SF2 (lanes 5 and 6) or 9G8 (lane 7) has no effect. Interestingly, complementation with SRp46 (lanes 8 and 9), expressed in human cells from an SC35-derived retrogene (Soret et al., 1998), also led to a partial splicing activation. To determine whether the splicing activation by SC35 was specific, we then analyzed splicing of the first intron of the major late adenovirus (MLA) transcription unit. As assessed by the accumulation of that intron (lane 11), splicing in the absence of added SR protein is quite efficient given the intron size (1021 nt), indicating that SR proteins were not limiting in our nuclear extracts. Complementation of these extracts with each individual SR protein, but especially with SC35 or ASF/SF2 (lanes 12 and 13), led to a splicing inhibition specific to the MLA intron, because such inhibition does not occur when introns of a similar size are spliced from the wt-CE and βglo-CE pre-mRNA (Figure 7). These results indicate that the SC35-dependent activation observed with the wt-RI pre-mRNA does not represent a general consequence of nuclear extract complementation by individual SR proteins.

Fig. 6. In vitro splicing of the retained intron (wt-RI) pre-mRNA. The wt-RI (left panel) and MLA (right panel) pre-mRNA substrates were subjected to in vitro splicing assays and the RNAs were analyzed by PAGE. Lanes 1 and 10, pre-mRNA starting material; lanes 2 and 11, splicing assays with the nuclear extract alone. The other assays were supplemented by individual SR proteins as indicated above the lanes. In the left panel, increasing amounts (7 and 14 pmol) of SC35 (lanes 3 and 4), ASF/SF2 (lanes 5 and 6) and SRp46 (lanes 8 and 9) or 10 pmol of 9G8 (lane 7) were added to the assays. In the right panel, the higher amount of each SR protein is added. Note that, for Figures 6 and 7, the use of three different nuclear extract preparations gave very similar results. The positions of precursors, intermediates and final products are indicated to the left of the autoradiograms.

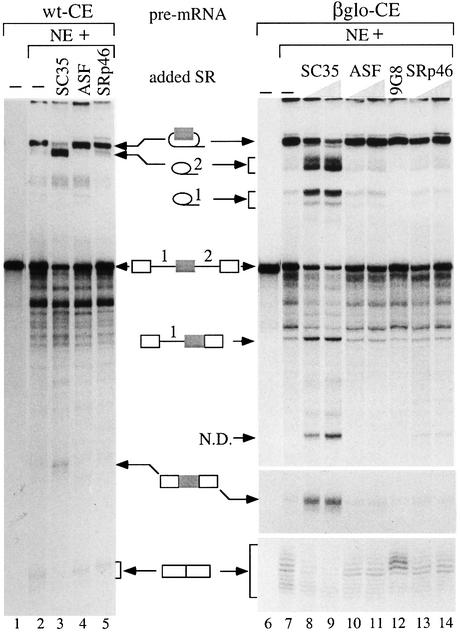

Fig. 7. In vitro splicing of the SC35 cassette exon. The wt-CE (left panel) and the βGlo-CE (right panel) pre-mRNAs were spliced in the presence of nuclear extracts alone or supplemented with the individual SR proteins as in Figure 6. Lanes 1 and 6, pre-mRNA starting material; lanes 2 and 7, splicing assays with the nuclear extract alone. In the right panel, 7 and 14 pmol are used for SC35, ASF/SF2 and SRp46, and 10 pmol for 9G8. In the left panel, the higher amount of each SR protein was used. At the bottom of the right panel, two small zones, only including the 3- or 2-exon mRNA, are shown. The positions of the RNA products are indicated at the side of both panels.

Studies performed with the wild-type wt-CE pre-mRNA in HeLa nuclear extracts (Figure 7, lane 2) revealed that the splicing of the large 980 nt intron, including the cassette exon, is moderately efficient. This result was not surprising, since this whole region remains unspliced in vivo in the 2.5 and 3.0 kb SC35 mRNAs (Figure 3). Accordingly, the accumulation of the short 2-exon mRNA of 278 nt was weak. Very similar splicing patterns were observed when nuclear extracts were complemented with ASF/SF2 (lane 4) and SRp46 (lane 5), where the splicing efficiency in the presence of ASF/SF2 was slightly better. As already observed for the wt-RI substrate, complementation with SC35 (lane 3) resulted in a strong shift of splicing, revealed by the accumulation of a novel lariat intron of smaller size (the 598 nt intron 2) at the expense of the larger intron. An additional band with an apparent size of 540 nt, possibly corresponding to the free intron 1 of 278 nt, was also weakly visible. Concomitantly, the 382 nt mRNA, including the cassette exon, was detected, although at a weak level.

Splicing of the chimeric βglo-CE substrate in HeLa nuclear extract was more efficient than that of the wt-CE substrate, as shown by the strong accumulation of the 1044 nt intron containing the cassette exon and the detection of the 128 nt 2-exon mRNA (Figure 7, right panel, lane 7). However, the weak accumulation of the excised intron 1 and 2 showed poor recognition of the cassette exon. As previously, addition of ASF, 9G8 and SRp46 to the nuclear extracts (lanes 10–14) did not significantly modify this splicing pattern. In contrast, SC35 induced a dramatic shift of splicing, as revealed by the accumulation of the individual introns 1 and 2, of the splicing intermediates lacking intron 2 and of the 3-exon mRNA (lanes 8 and 9). Concomitantly, accumulation of the large 1044 nt intron and of the 2-exon mRNA was decreased. These results demonstrate that increasing concentrations of SC35 strongly stimulate the inclusion of the cassette exon and that the 451 nt region including the cassette exon is sufficient to promote this specific regulation.

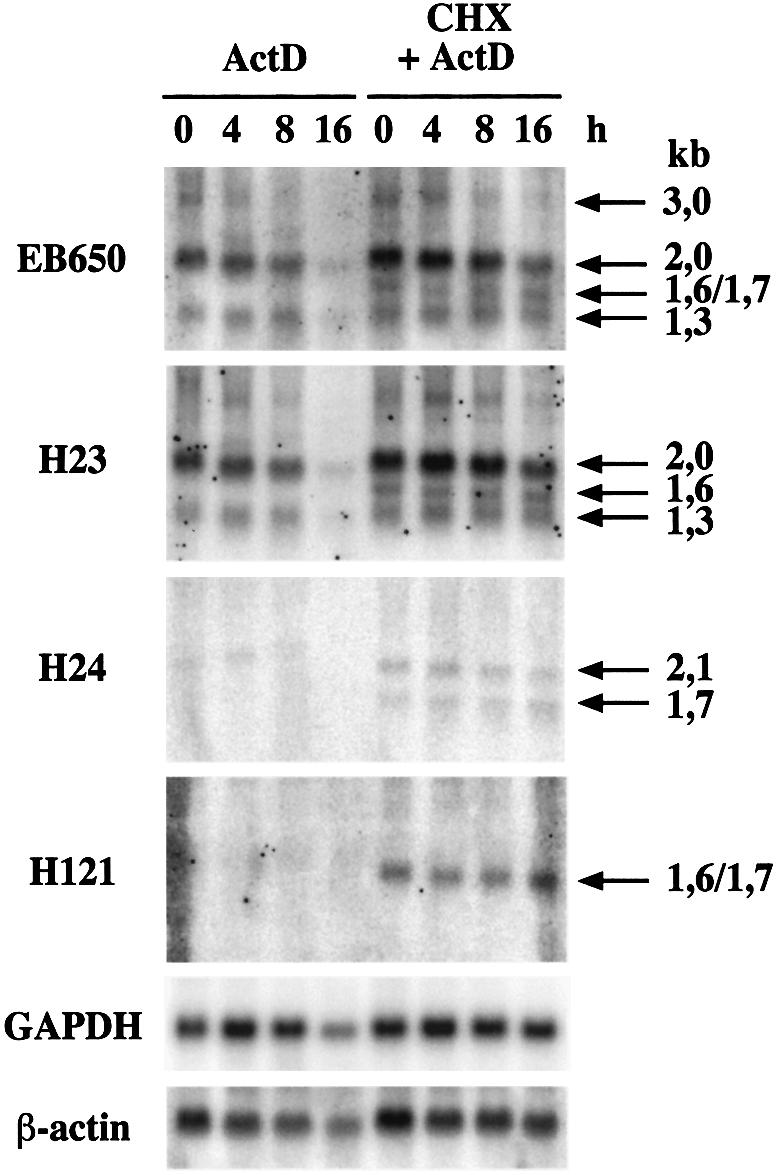

The 1.7 kb SC35 mRNA exhibits a very low stability in HeLa cells

Our previous northern blot analyses of alternative SC35 mRNAs have revealed that the 1.6/1.7 kb SC35 mRNAs are not detected in hematopoietic CCRF-CEM cells, except when cells have been treated for 2 h with cycloheximide (Sureau and Perbal, 1994). To test whether these SC35 mRNAs exhibit the same behavior in HeLa cells, we performed northern blot analysis of total RNA purified from HeLa cells incubated in the presence of actinomycin D with or without a 2 h pre-treatment with cycloheximide. Hybridization with the EB650 probe, specific for the different SC35 transcripts, indicates that mRNAs of 1.6/1.7 kb are only detected in cells pre-incubated with cycloheximide (Figure 8). Moreover, cycloheximide pre-incubation results in stabilization of the 1.7/1.6 and 1.3 kb transcripts, since they are present at similar levels from 4 to 16 h after actinomycin D treatment. Similar analyses performed with probes specific for distinct exon–exon junctions (H23, H24 and especially H121, Figure 3) confirmed that the 1.6/1.7 kb mRNAs correspond to species lacking the intronic sequences delineated by the D4–A4 splice sites (H121 probe) that differ by exclusion or inclusion of the cassette exon delineated by the A2–D3 splice sites (H23 and H24 probes, respectively). Taken together, these observations indicate that both the 1.6 and 1.7 kb SC35 mRNAs exhibit a very low stability in HeLa cells and suggest that their translation is required for rapid degradation.

Fig. 8. Analysis of the SC35 mRNA stability in HeLa cells. Cells were incubated for increasing periods of time (4–16 h) in the presence of actinomycin D (ActD, 5 µg/ml). Northern blot analyses of total RNA (20 µg/lane) were performed with the indicated probes. Samples obtained from HeLa cells pre-incubated in the presence of cyclo heximide (CHX, 10 µg/ml) prior to actinomycin D treatment were analyzed in the same way. Hybridization with GAPDH and β-actin probes was performed to normalize for RNA amount and transfer efficiency.

One explanation accounting for the low stability of the 1.6 and 1.7 kb mRNAs might be nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) or mRNA surveillance (Sun and Maquat, 2000 and references therein). Indeed, a rule for termination-codon position within intron-containing genes in mammalian cells states that only those termination codons located >50–55 nt upstream of the 3′-most exon–exon junction mediate mRNA decay (reviewed in Sun and Maquat, 2000). Since switching the alternative splicing of the SC35 pre-mRNA from the 2.0 to the 1.7 kb isoform moves the 3′-most exon–exon junction away from the SC35 translation stop codon (7 nt in the 2.0 kb versus 209 nt in the 1.7 kb mRNA), we tested whether NMD processes could be involved in the differential stability of the SC35 transcripts.

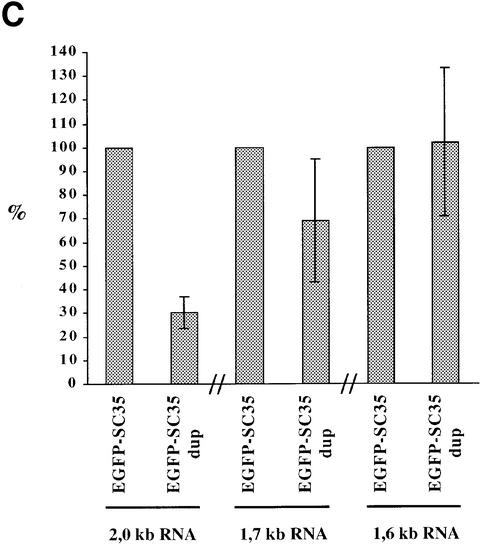

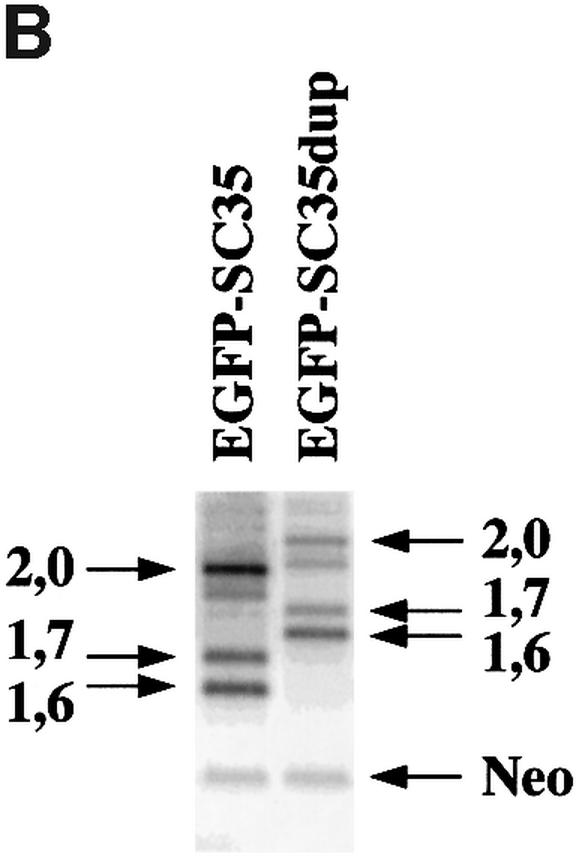

To address this question, we constructed two reporter vectors (Figure 9A). In the first construct (EGFP-SC35), SC35 genomic sequences corresponding to the 3′ end of the second coding exon and to the whole 3′UTR are fused in-frame downstream of the EGFP sequences. The second construct (EGFP-SC35dup) is similar, except that the SC35 3′ coding region is duplicated, thereby increasing the distance between the translation stop codon and the first splice donor site by 198 nt, and hence the size of the transcripts. Two days following transient transfection of HeLa cells, EGFP-SC35 mRNA levels were analyzed by semi-quantitative RT–PCR experiments. EGFP-SC35 transcripts corresponding to the 2.0, 1.7 and 1.6 kb SC35 mRNA isoforms were clearly detected in transfected cells (Figure 9B). As expected, mRNAs corresponding to the 2.0 kb species are predominantly expressed in cells transfected with the EGFP-SC35 construct, whereas their level is decreased by 70% in cells transfected with the EGFP-SC35dup vector (Figure 9C). In the latter, the relative amount of transcripts corresponding to the 1.7 kb species is moderately decreased, while that of the 1.6 kb mRNA is not significantly modified. Taken together, these results indicate that the 2.0 kb transcripts are strongly destabilized when the distance between the translation stop codon and the 3′-most splice junction is artificially increased. Since a very similar situation occurs naturally in the 1.7 kb mRNA, our observations support the notion that the splicing events promoted by SC35 elicit NMD processes and degradation of the resulting mRNAs.

Fig. 9. Analysis of EGFP-SC35 mRNA stability in HeLa cells. (A) Schematic representation of the reporter constructs. The features of the SC35 gene are indicated as in Figure 1 and the EGFP sequences are indicated. Splicing events used to generate the 2.0, 1.7 and 1.6 kb SC35 mRNAs are depicted by lines. In the EGFP-SC35dup reporter vector, the SC35 3′-proximal coding sequences and the translation stop codon are duplicated. For both reporter vectors, the distance between the first translation stop codon and the D2 splice donor site is indicated on the left. (B) Representative 1.5% agarose gel of the RT–PCR products corresponding to the EGFP-SC35 mRNAs. PCR products corresponding to EGFP-SC35 isoforms spliced as the 2.0, 1.7 and 1.6 kb SC35 mRNAs are indicated. RT–PCR products corresponding to neomycin (Neo) mRNAs expressed from both reporter vectors and used to normalize for transfection efficiency are shown. (C) Relative abundance of the EGFP-SC35 mRNAs as determined from four independent transfection experiments. The amounts of the different EGFP-SC35 mRNA isoforms detected in HeLa cells transfected with the EGFP-SC35 vector were fixed to 100%.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that accumulation of the SC35 splicing factor in HeLa cells leads to the alteration of the alternative splicing pattern and the downregulation of endogenous mRNA and protein levels. Decreased endogenous mRNA levels have also been observed in response to overexpression of ASF/SF2 and atSRp30 (Wang et al., 1996; Lopato et al., 1999), but the mechanisms underlying this regulation remain uninvestigated. Negative feedback regulation appears to be a common mechanism controlling the level of splicing regulators. Indeed, the Drosophila splicing factors tra-2 (Mattox and Baker, 1991), SWAP (Zachar et al., 1994) and the murine SRp20 protein (Jumaa and Nielsen, 1997) autoregulate the splicing of their own pre-mRNAs through activation of alternative splicing events leading to the expression of a truncated protein.

The alteration of the SC35 splicing pattern in response to SC35 overexpression sheds a new light on the mechanisms controlling SR protein expression levels. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing that autoregulation of an SR protein-encoding gene expression is mediated by stimulation of splicing events affecting the 3′UTR and mRNA stability. In Caenorhabditis elegans, it has been reported that the stability of alternatively spliced SRp20 and SRp30b mRNAs is affected by smg genes exhibiting allele-specific suppression of nonsense mutations (Morrison et al., 1997). However, this situation differs from that described here, since unstable SRp20 and SRp30b mRNAs contain alternative exons introducing upstream stop codons in the open reading frame. In contrast, both the very unstable SC35 1.6 and 1.7 kb transcripts retain a full coding capacity.

Our results suggest that NMD is likely to be involved in the diminished stability of the SC35 1.6 and 1.7 kb mRNAs. First, it is noteworthy that in hematopoietic (Sureau and Perbal, 1994) and HeLa cells (this work), cycloheximide treatment is required to detect the endogenous 1.6 and 1.7 kb SC35 mRNAs, an observation consistent with the fact that NMD processes are reversed by translation inhibitors (Carter et al., 1995). The second argument follows from our observations that: (i) the 3′UTR of the 1.7 kb mRNA does not affect RNA stability when fused to a reporter gene (Supplementary data); and (ii) the half-life of the 1.6 and 1.7 kb transcripts in cycloheximide-treated cells (Figure 8) is similar to or even higher than that of the 2.0 kb species. Indeed, it has been reported that the fraction of nucleus-associated mRNA escaping NMD is exported to the cytoplasm and exhibits normal stability (Cheng and Maquat, 1993 and references therein). Finally, we have shown that increasing the distance between the translation stop codon and the 3′-most exon–exon junction to 205 nt, i.e. as in the 1.7 kb mRNA, leads to a dramatic decrease in 2.0 kb mRNA levels (Figure 9). Taken together, these observations strongly suggest that, unlike C.elegans SRp20, SRp30b and rpl-12 autoregulation eliciting NMD via unproductively spliced mRNAs (Morrison et al., 1997; Mitrovich and Anderson, 2000), SC35 autoregulation is mediated by alternative but productive splicing coupled with mRNA surveillance.

While SC35 has been widely studied, only a limited number of pre-mRNAs corresponding to natural substrates of the SC35 splicing activity have been characterized thus far. Recently, the constitutive C3–C4 exons of the immunoglobulin µ-chain (IgM) pre-mRNA (Mayeda et al., 1999) and E1–E2 exons of the β globin pre-mRNA (Schaal and Maniatis, 1999a) were found to be preferentially spliced with SC35, but they represent constitutively spliced substrates. In the case of the β-tropomyosin pre-mRNA, SC35 has been reported to inhibit the splicing of exon 6A, which is otherwise stimulated by SF2/ASF (Gallego et al., 1997). In contrast, SC35 and SF2/ASF act in the same way in promoting exon skipping within the Ich-1 mRNA (Jiang et al., 1998). Notably, we have not observed significant changes in the Ich-1 splicing pattern in different HeLa cell clones overexpressing SC35 (Supplementary data), most probably because exon skipping in the Ich-1 mRNA is already predominant in uninduced HeLa cells and/or because the SC35 expression levels are not sufficient to regulate Ich-1 splicing.

Our data identify the SC35 pre-mRNA as another interesting target of the SC35 splicing activity. To our knowledge, this is the first example of a natural substrate where SC35 promotes two different splicing events consisting of inclusion of an alternative exon and splicing of a retained intron. Significantly, the SC35-derived pre-mRNA substrates that we have tested in vitro respond specifically to the SC35 protein, suggesting that putative cis-acting sequences present in the retained intron and cassette exon regions are fully recognized by SC35. While ASF/SF2 and 9G8 do not affect alternative splicing of these substrates, SRp46, encoded by a SC35 retrogene (Soret et al., 1998), also stimulates, although to a lower extent, the splicing of the retained intron (Figure 6). Thus, it is conceivable that SRp46 exhibits an RNA substrate specificity different from that of SC35 but is still able to recognize, with a lower affinity, SC35-specific binding sites.

The isolation of high affinity targets specific for SC35 by a conventional SELEX approach identified several purine- or pyrimidine-rich consensus sequences that showed no or poor enhancer activities as compared with those specific for ASF/SF2, 9G8 or SRp20 (Tacke and Manley, 1995; Cavaloc et al., 1999). In contrast, a functional selection approach identified sequences with significant enhancer activity mediated by the SC35 splicing factor (Liu et al., 2000). However, the defined consensus GRYYcSYR is highly degenerate and the sequences identified are not fully specific for SC35, because SRp40 and SRp55 also activate them (Liu et al., 2000). Functional splicing enhancers for SC35 have also been isolated by a variant approach (Schaal and Maniatis, 1999b) or identified directly as constitutive enhancers from β globin exon 2 (Schaal and Maniatis, 1999a). Although similar to pyrimidine-rich sequences identified previously (Tacke and Manley, 1995; Cavaloc et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2000), the prototypical motif UGCUGUU exhibits an efficient activation capacity. Sequence analysis of the SC35 3′UTR revealed numerous potential SC35 enhancer motifs. However, we will have to precisely identify and fully characterize these enhancers, and especially compare them with those identified in constitutive exons.

Of particular interest is the notion that the 3′UTR of the SC35 gene, which undergoes splicing regulation, was not subjected to coding sequence constraints during evolution. Thus, this region could represent an ideal model of regulation mediated by the SC35 protein. Importantly, a comparison between human, mouse and chicken SC35 sequences revealed that short regions (100–200 nt) in the cassette exon and near the splice sites of the retained intron are highly conserved (from 90 to 98%) between these three species. Further studies will be needed to determine whether this conservation reflects the conservation of sequences required by SC35 to achieve regulation of its own expression.

Materials and methods

Plasmid construction

The SC35 open reading frame was PCR amplified from the HPR5 cDNA (Sureau and Perbal, 1994) and cloned in the pECE-HA1 constitutive expression vector to generate pECE-HA-SC35. HA-tagged SC35 sequences recovered from this plasmid were inserted into pUHD 10-3 (Gossen et al., 1995) to generate the pUHD-HA-SC35 inducible expression vector. In the corresponding control vector (pUHD-HA-SC35-mut), the four internal in-frame ATG codons present in SC35 sequences were converted into stop codons by serial PCR amplifications. In the pUHD-HA-SC35 geno vector, SC35 genomic sequences comprised between the ATG initiation codon and the more distal polyadenylation site were inserted in place of cDNA sequences in pUHD-HA-SC35. A non-coding version of these sequences was PCR generated to obtain the control pUHD-HA-SC35 geno-mut. EGFP-SC35 and EGFP-SC35dup used in NMD studies were obtained by subcloning SC35 3′ coding sequences and 3′UTR downstream from EGFP sequences in the pEGFP-c2 vector (Clontech). Detailed cloning strategies are available upon request.

Cell culture and transfection conditions

HeLa Tet-On cells (Clontech) were transfected by calcium phosphate co-precipitation according to standard protocols. Briefly, 4 × 105 cells seeded in 60 mm dishes were transfected 24 h later with a mixture consisting of 5 µg of SC35 expression vectors, 2 µg of pNT-Hygro selection vector and 8 µg of carrier DNA (pBKS). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were incubated in fresh medium containing 150 µg/ml hygromycin (Sigma) and 100 µg/ml geneticin (Life Technologies). Resistant clones were isolated 15–20 days later and expanded for further analyses. Induction of SC35 expression was performed in the presence of 1 µg/ml Dox (Sigma) for various times. Before transient transfection, HeLa cells were incubated for 48 h in the presence of 1 µg/ml Dox to induce expression of SC35 sequences. Transfection was performed as described above in the presence of Dox.

Origin and derivation of probes

The EB650 probe detecting the different SC35 mRNAs was previously described (Sureau and Perbal, 1994). The HA probe (5′-GAGGCT AGCATAATCAGGAAC-3′) is specific for the tag sequence present at the 5′ end of exogenous SC35 RNAs. The SC35 probe specific for the 5′UTR of endogenous SC35 mRNAs corresponds to a 378 bp PCR-generated fragment. Oligonucleotides H23, H24 (Sureau and Perbal, 1994) and H121 (5′-CACAACTGCGCCTTTTCAAT-3′), specific for different exon–exon junctions, were used as probes for Southern blot analysis of RT–PCR products and northern blot analysis of SC35 mRNAs. The human GAPDH (Clontech) and β-actin-specific probes were used for normalization of northern blot hybridization signals. The GAPDH-specific probe (5′-CCAAAGTTGTCATGGATGACC-3′) was used for normalization of Southern blot hybridization signals.

Northern and western blot analysis

Total RNA and protein samples were purified with Tri-Reagent (Sigma) as recommended. Labeling of probes, northern blotting and hybridizations were performed according to standard procedures. Protein samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Immobilon P, Millipore). Detection was performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (NEN Life Science). HA-tagged proteins were revealed with the 12CA5 monoclonal (Boehringer Mannheim) and peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Jackson Immuno research Laboratories).

RT–PCR analysis

First strand cDNA was synthesized from 5 µg of DNase-treated total RNA with the Amersham cDNA synthesis kit. For analysis of cDNA corresponding to exogenous SC35 mRNAs, one-twentieth of the reaction was amplified by 20 PCR cycles with the HA (5′-GTTCCT GATTATGCTAGCCTC-3′) and the H74 (5′-AAGGCCCGGGTGACT GGAAGTGC-3′) primers. Amplification of cDNAs corresponding to endogenous SC35 messengers was performed by 22 PCR cycles under the same conditions except that H120 (5′-GGCCGCCACTCAGAGCT ATG-3′), specific for the SC35 5′UTR, was used instead of the HA primer. Amounts of cDNA subjected to PCR amplifications were normalized with primers specific for GAPDH sequences. PCR products amplified with Expand Long Template Taq DNA polymerase (Roche) were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with oligonucleotidic probes. For NMD studies, amplification of EGFP-SC35 cDNAs was performed in the presence of 2 µCi of [α-32P]dCTP by 22 or 25 PCR cycles with the EGFP-specific (5′-GACGAGCTGTACAAGTCC-3′) and H74 primers. Neomycin mRNA levels were used to normalize for transfection efficiency. Densitometric analyses were performed with a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

In vitro splicing assays

Transcription vectors used to generate pre-mRNA substrates were constructed as follows. A 765 bp fragment containing SC35 3′UTR sequences (positions 3209–3973 in DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. X75755) was PCR amplified and subcloned at the SacI and EcoRI sites in the pBKS vector (Stratagene) to generate the wt-RI construct. The wt-CE construct was obtained following subcloning of a 1240 bp PCR-generated fragment (positions 2125–3364) at the SacI and EcoRI sites in pBKS. The βGlo-CE construct was created from the BSSK HG2 vector, which contains the human β globin exon 2–intron 2–exon 3 region (provided by Dr R.Breathnach, INSERM, Nantes, France), by insertion of a 451 bp PCR-generated fragment (positions 2265–2715) at the HincII site in intron 2.

Capped 32P-labeled pre-mRNA substrates were obtained by in vitro transcription with T7 or T3 RNA polymerase, and HeLa nuclear extracts and cytoplasmic S100 extracts were prepared as described (Bourgeois et al., 1999). In vitro splicing was performed in 25 µl assays containing 9 µl of nuclear extract plus 2 µl of S100 and the basic components for the splicing reaction (Bourgeois et al., 1999). The splicing reaction was carried out in the presence of 60 mM KCl and 3.2 mM MgCl2, except for the MLA precursor (48 mM KCl and 1.6 mM MgCl2), for 2 h at 30°C. Some assays were supplemented by purified recombinant SR proteins (7–14 pmol), as indicated. Splicing products were analyzed on 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels and visualized by autoradiography.

RNA stability measurements

HeLa cells (3.5 × 105) were incubated in the presence of actinomycin D (5 µg/ml) for 4–16 h. Total RNA was analyzed by northern blot hybridization with either the EB650 probe or the H23, H24 and H121 oligonucleotidic probes. To measure RNA stability in the absence of protein synthesis, similar experiments were performed after a 2 h cycloheximide (10 µg/ml) treatment.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data for this paper are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

A.Sureau and J.Soret are grateful to Dr G.Calothy, Professor D.Louvard, Drs J.Marie and J.Tazi for constant support during this work. We gratefully acknowledge Drs J.Tazi, R.Bordonné, J.Marie, A.Expert-Bezançon, C.Thermes and R.Hipskind for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful advice. D.Rouillard is acknowledged for her precious help in apoptosis studies. We also thank the staff of the IGBMC facilities for their assistance. This work was supported by grants from Institut Curie, CNRS, INSERM and Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer.

References

- Bourgeois C.F., Popielarz,M., Hildwein,G. and Stevenin,J. (1999) Identification of a bidirectional splicing enhancer: differential involvement of SR proteins in 5′ or 3′ splice site activation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 7347–7356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres J.F., Stamm,S., Helfman,D.M. and Krainer,A.R. (1994) Regulation of alternative splicing in vivo by overexpression of antagonistic splicing factors. Science, 265, 1706–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter M.S., Doskow,J., Morris,P., Li,S., Nhim,R.P., Sandstedt,S. and Wilkinson,M.F. (1995) A regulatory mechanism that detects premature nonsense codons in T-cell receptor transcripts in vivo is reversed by protein synthesis inhibitors in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 28995–29003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaloc Y., Bourgeois,C.F., Kister,L. and Stevenin,J. (1999) The splicing factors 9G8 and SRp20 transactivate splicing through different and specific enhancers. RNA, 5, 468–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J. and Maquat,L.E. (1993) Nonsense codons can reduce the abundance of nuclear mRNA without affecting the abundance of pre-mRNA or half-life of cytoplasmic mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol., 13, 1892–1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X.D. (1995) The superfamily of arginine/serine-rich splicing factors. RNA, 1, 663–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X.D. and Maniatis,T. (1992) Isolation of a complementary DNA that encodes the mammalian splicing factor SC35. Science, 256, 535–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego M.E., Gattoni,R., Stevenin,J., Marie,J. and Expert-Bezancon,A. (1997) The SR splicing factors ASF/SF2 and SC35 have antagonistic effects on intronic enhancer-dependent splicing of the β-tropomyosin alternative exon 6A. EMBO J., 16, 1772–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge H., Zuo,P. and Manley,J.L. (1991) Primary structure of the human splicing factor ASF reveals similarities with Drosophila regulators. Cell, 66, 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen M., Freundlieb,S., Bender,G., Muller,G., Hillen,W. and Bujard,H. (1995) Transcriptional activation by tetracyclines in mammalian cells. Science, 268, 1766–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveley B.R. (2000) Sorting out the complexity of SR protein functions. RNA, 6, 1197–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanamura A., Caceres,J.F., Mayeda,A., Franza,B.R.,Jr and Krainer,A.R. (1998) Regulated tissue-specific expression of antagonistic pre-mRNA splicing factors. RNA, 4, 430–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman B.E. and Lis,J.T. (2000) Pre-mRNA splicing by the essential Drosophila protein B52: tissue and target specificity. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 181–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z.H., Zhang,W.J., Rao,Y. and Wu,J.Y. (1998) Regulation of Ich-1 pre-mRNA alternative splicing and apoptosis by mammalian splicing factors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 9155–9160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumaa H. and Nielsen,P.J. (1997) The splicing factor SRp20 modifies splicing of its own mRNA and ASF/SF2 antagonizes this regulation. EMBO J., 16, 5077–5085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus M.E. and Lis,J.T. (1994) The concentration of B52, an essential splicing factor and regulator of splice site choice in vitro, is critical for Drosophila development. Mol. Cell. Biol., 14, 5360–5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labourier E., Bourbon,H.M., Gallouzi,I.E., Fostier,M., Allemand,E. and Tazi,J. (1999) Antagonism between RSF1 and SR proteins for both splice-site recognition in vitro and Drosophila development. Genes Dev., 13, 740–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.X., Chew,S.L., Cartegni,L., Zhang,M.Q. and Krainer,A.R. (2000) Exonic splicing enhancer motif recognized by human SC35 under splicing conditions. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 1063–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopato S., Kalyna,M., Dorner,S., Kobayashi,R., Krainer,A.R. and Barta,A. (1999) atSRp30, one of two SF2/ASF-like proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana, regulates splicing of specific plant genes. Genes Dev., 13, 987–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley J.L. and Tacke,R. (1996) SR proteins and splicing control. Genes Dev., 10, 1569–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattox W. and Baker,B.S. (1991) Autoregulation of the splicing of transcripts from the transformer-2 gene of Drosophila. Genes Dev., 5, 786–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda A., Munroe,S.H., Caceres,J.F. and Krainer,A.R. (1994) Function of conserved domains of hnRNP A1 and other hnRNP A/B proteins. EMBO J., 13, 5483–5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda A., Screaton,G.R., Chandler,S.D., Fu,X.D. and Krainer,A.R. (1999) Substrate specificities of SR proteins in constitutive splicing are determined by their RNA recognition motifs and composite pre-mRNA exonic elements. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 1853–1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovich Q.M. and Anderson,P. (2000) Unproductively spliced ribosomal protein mRNAs are natural targets of mRNA surveillance in C. elegans. Genes Dev., 14, 2173–2184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison M., Harris,K.S. and Roth,M.B. (1997) smg mutants affect the expression of alternatively spliced SR protein mRNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 9782–9785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popielarz M., Cavaloc,Y., Mattei,M.G., Gattoni,R. and Stevenin,J. (1995) The gene encoding human splicing factor 9G8. Structure, chromosomal localization, and expression of alternatively processed transcripts. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 17830–17835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R. (1996) Initial splice-site recognition and pairing during pre-mRNA splicing. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 6, 215–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal T.D. and Maniatis,T. (1999a) Multiple distinct splicing enhancers in the protein-coding sequences of a constitutively spliced pre-mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 261–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaal T.D. and Maniatis,T. (1999b) Selection and characterization of pre-mRNA splicing enhancers: identification of novel SR protein-specific enhancer sequences. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 1705–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Screaton G.R., Caceres,J.F., Mayeda,A., Bell,M.V., Plebanski,M., Jackson,D.G., Bell,J.I. and Krainer,A.R. (1995) Identification and characterization of three members of the human SR family of pre-mRNA splicing factors. EMBO J., 14, 4336–4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C.W. and Valcarcel,J. (2000) Alternative pre-mRNA splicing: the logic of combinatorial control. Trends Biochem. Sci., 25, 381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soret J. et al. (1998) Characterization of SRp46, a novel human SR splicing factor encoded by a PR264/SC35 retropseudogene. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 4924–4934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X. and Maquat,L.E. (2000) mRNA surveillance in mammalian cells: the relationship between introns and translation termination. RNA, 6, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sureau A. and Perbal,B. (1994) Several mRNAs with variable 3′ untranslated regions and different stability encode the human PR264/SC35 splicing factor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 932–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacke R. and Manley,J.L. (1995) The human splicing factors ASF/SF2 and SC35 possess distinct, functionally significant RNA binding specificities. EMBO J., 14, 3540–3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacke R. and Manley,J.L. (1999) Determinants of SR protein specificity. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol., 11, 358–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellard M., Sureau,A., Soret,J., Martinerie,C. and Perbal,B. (1992) A potential splicing factor is encoded by the opposite strand of the trans-spliced c-myb exon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 2511–2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Takagaki,Y. and Manley,J.L. (1996) Targeted disruption of an essential vertebrate gene: ASF/SF2 is required for cell viability. Genes Dev., 10, 2588–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Xiao,S.H. and Manley,J.L. (1998) Genetic analysis of the SR protein ASF/SF2: interchangeability of RS domains and negative control of splicing. Genes Dev., 12, 2222–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachar Z., Chou,T.B., Kramer,J., Mims,I.P. and Bingham,P.M. (1994) Analysis of autoregulation at the level of pre-mRNA splicing of the suppressor-of-white-apricot gene in Drosophila. Genetics, 137, 139–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]