Abstract

Mammalian rRNA genes are preceded by a terminator element that is recognized by the transcription termination factor TTF-I. In exploring the functional significance of the promoter-proximal terminator, we found that TTF-I associates with the p300/CBP-associated factor PCAF, suggesting that TTF-I may target histone acetyltransferase to the rDNA promoter. We demonstrate that PCAF acetylates TAFI68, the second largest subunit of the TATA box-binding protein (TBP)-containing factor TIF-IB/SL1, and acetylation enhances binding of TAFI68 to the rDNA promoter. Moreover, PCAF stimulates RNA polymerase I (Pol I) transcription in a reconstituted in vitro system. Consistent with acetylation of TIF-IB/SL1 being required for rDNA transcription, the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase mSir2a deacetyl ates TAFI68 and represses Pol I transcription. The results demonstrate that acetylation of the basal Pol I transcription machinery has functional consequences and suggest that reversible acetylation of TIF-IB/SL1 may be an effective means to regulate rDNA transcription in response to external signals.

Keywords: acetylation/mSir2a/PCAF/RNA polymerase I/ TIF-IB/SL1

Introduction

Packaging of DNA into chromatin inhibits transcription at the initiation and elongation step. Therefore, for transcription to proceed the cell must recruit proteins to alleviate nucleosome-mediated transcriptional repression. Several laboratories have pursued the mechanisms by which nucleosome and chromatin structure are altered in order to facilitate binding of sequence-specific transcription factors to DNA and transcription initiation. These studies have revealed the participation of multiprotein complexes in the remodeling of chromatin structures. One group of such complexes are ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling machines, such as SWI/SNF, NURF, CHRAC, ACF and RSC, that are thought to facilitate transcription factor binding or function through alteration of nucleosome structure or position (for reviews see Wu, 1997; Kadonaga, 1998). A second group includes transcriptional coactivators with histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity that, through acetylation of N-terminal lysines, alter histone–DNA interactions and nucleosome stability functions (for reviews see Wade and Wolffe, 1997; Struhl, 1998). Increased levels of histone acetylation are often associated with enhanced transcriptional activity (Hebbes et al., 1988), whereas hypoacetylation of histones correlates with transcriptional silencing (reviewed by Pazin and Kadonaga, 1997).

In previous studies, we have demonstrated that alleviation of nucleosome-mediated transcriptional repression by DNA-bound proteins is also a key event in class I gene transcription on nucleosomal templates. Transcription of rDNA on chromatin requires binding of the transcription termination factor TTF-I to the promoter-proximal terminator element, known as T0, which is positioned 160 bp upstream of the transcription start site (Längst et al., 1997). Binding of TTF-I to T0 results in alterations of the chromatin structure, including the establishment of DNase I-hypersensitive sites adjacent to the bound factor and relocation of a nucleosome. Chromatin remodeling induced by TTF-I is a prerequisite for transcriptional activation on otherwise repressed nucleosomal rDNA templates. Apparently, TTF-I-mediated chromatin remodeling facilitates the access of basal RNA polymerase I (Pol I) transcription factors or recruits chromatin-modifying activities to the rDNA promoter (Längst et al., 1998).

Consistent with this, sequence-specific transcription factors and coactivators have been demonstrated to target HATs and deacetylases to promoters. The finding that many coactivators (e.g. GCN5, CBP/p300, PCAF, ACTR, SRC-1, BRCA2 and TAFII250) are HATs that are contained in large multiprotein complexes has led to an appealing model that transcription activators recruit these enzymes to certain gene promoters to destabilize nucleosomes. These structural transitions enhance the accessibility of DNA to various factors, thereby reducing the repressive effect of nucleosomes. Most studies concerning the effect of acetylation on the structure and function of chromatin have focused on the reversible acetylation of core histones. In addition to histones, other chromatin-associated proteins are also modified by HATs, such as the non-histone proteins HMG-17 and HMGI(Y) (Munshi et al., 1998; Herrera et al., 1999) as well as several transcription factors including p53 (Gu and Roeder, 1997; Sakaguchi et al., 1998; Liu et al., 1999), GATA-1 (Boyes et al., 1998), EKLF (Zhang and Bieker, 1998), E2F1 (Martínez-Balbás et al., 2000), TCF (Waltzer and Bienz, 1998), HNF-4 (Soutoglou et al., 2000) and the basal factors TFIIE and TFIIF (Imhof et al., 1997). The list of acetylated proteins is increasing rapidly.

Acetylation can have either stimulatory or inhibitory effects on transcription. In the case of p53, E2F1, GATA-1 and EKLF, acetylation occurs directly adjacent to the DNA-binding domain and acetylation enhances DNA binding in vitro and in vivo (Gu and Roeder, 1997; Sakaguchi et al., 1998; Liu et al., 1999; Martínez-Balbás et al., 2000). Specific acetylation of HMGI(Y) by CBP, on the other hand, leads to enhanceosome disassembly and turn-off of interferon-β gene expression (Munshi et al., 1998). In addition, the stability of proteins and protein– protein interactions are affected by acetylation, indicating that acetylation regulates a variety of cellular functions.

To elucidate the role of TTF-I binding to the upstream terminator, we have examined whether TTF-I can interact with the p300/CBP-associated factor PCAF, thereby recruiting HAT activity to the rDNA promoter. Indeed, we found that PCAF interacts with TTF-I and acetylates TAFI68, the second largest subunit of the TATA box-binding protein (TBP)-containing promoter selectivity factor TIF-IB/SL1. Acetylation by PCAF increases the DNA binding activity of TAFI68 and enhances Pol I transcription. mSir2a, a murine NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase that, by analogy to yeast Sir2, may play a role in silencing of the rDNA locus, can deacetylate TAFI68 and repress Pol I transcription in vitro. The results indicate that HATs modify component(s) of the Pol I transcriptional machinery and suggest acetylation as a novel regulatory modification that activates rDNA transcription.

Results

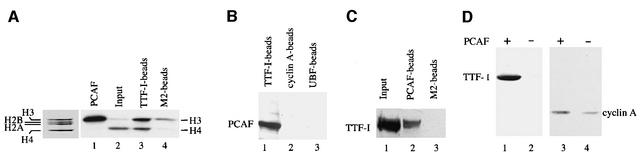

TTF-I interacts with PCAF

To examine whether TTF-I may recruit HAT(s) to the rDNA promoter, recombinant TTF-I was immobilized on agarose beads and incubated with extracts from mouse cells. TTF-I-associated HAT activity was determined using core histones as substrates. As shown in Figure 1A, significant levels of HAT activity were associated with bead-bound TTF-I but not with control beads saturated with the FLAG peptide (lanes 3 and 4). Notably, whereas the endogenous HAT activity of the extract preferentially acetylated histone H4 (lane 2), the HAT that was retained on TTF-I beads preferentially acetylated histone H3. No labeling of histones H2A and H2B was observed. The preferential acetylation of histone H3 suggests that PCAF has been pulled down by TTF-I. Indeed, western blot analysis of bead-bound proteins revealed that significant levels of PCAF protein were retained on the TTF-I beads (Figure 1B, lane 1). No PCAF was detected on control beads saturated with cyclin A (lane 2) or upstream binding factor (UBF) (lane 3). In a reciprocal experiment, immobilized PCAF was incubated with mouse cell extract and specific retention of cellular TTF-I was demonstrated on immunoblots using anti-TTF-I antibodies (Figure 1C, lane 2).

Fig. 1. TTF-I interacts with PCAF. (A) Pull-down of cellular HAT activity by TTF-I. A 10 µg aliquot of FLAG-TTF-I bound to 10 µl of M2-agarose beads (lane 3) or M2 beads saturated with the FLAG peptide (lane 4) was incubated with 2 mg of mouse whole-cell extract proteins for 4 h at 4°C in a total volume of 380 µl. After stringent washing, 50% of the beads were assayed for HAT activity using 5 µg of histones and 1 µCi of [3H]acetyl-CoA. In lanes 1 and 2, histone acetylation by recombinant PCAF or cell extract is shown. Histones were separated by 15% SDS–PAGE and visualized by Coomassie Blue staining (left panel) and fluorography (lanes 1–4). (B) Interaction of PCAF with bead-bound TTF-I. A 35 µl aliquot of Ni2+-NTA–agarose saturated with histidine-tagged TTF-I (lane 1) or cyclin A (lane 2), and M2-agarose saturated with FLAG-UBF (lane 3) were incubated with extracts from mouse cells. After washing, bead-bound proteins were subjected to western blot analysis using anti-PCAF antibodies. (C) Association of cellular TTF-I with PCAF. Bead-bound FLAG-PCAF (lane 2) or control beads (lane 3) were incubated with extract from mouse cells, and associated TTF-I was identified on immunoblots. In lane 1, the amount of TTF-I present in 10% of the extract is shown. (D) Co-immunoprecipitation of TTF-I and PCAF. Histidine-tagged TTF-I or cyclin A was co-expressed with FLAG-PCAF in Sf9 cells. PCAF was precipitated with anti-FLAG antibodies (M2) and analyzed on western blots for the presence of TTF-I (lanes 1 and 2) or cyclin A (lanes 3 and 4).

To demonstrate interaction of TTF-I with PCAF in vivo, histidine-tagged TTF-I was expressed in Sf9 cells in the absence or presence of FLAG-tagged PCAF, precipitated with anti-FLAG (M2) antibodies, and co-immunoprecipitated TTF-I was visualized on western blots (Figure 1D). Consistent with TTF-I interacting with PCAF in vivo, TTF-I was found to co-precipitate with PCAF (lane 1). When extracts from Sf9 cells were used that overexpress cyclin A in the absence or presence of PCAF, no co-immunoprecipitation with PCAF was observed (lanes 3 and 4). This specific interaction between PCAF and TTF-I suggests that PCAF may be recruited to the rDNA promoter by TTF-I.

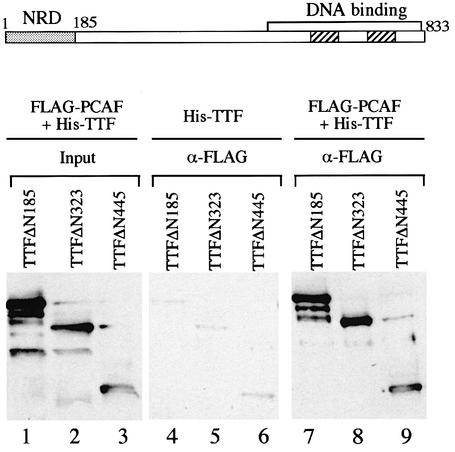

The C-terminal part of TTF-I interacts with PCAF

In order to delimit the part of TTF-I that interacts with PCAF, a series of N-terminal deletions of TTF-I were expressed in insect cells (Evers et al., 1995; Sander et al., 1996) and tested for their ability to interact with PCAF. Two of these mutants, TTFΔN185 and TTFΔN323, are functionally active, i.e. mediate Pol I transcription termination and transcriptional activation on chromatin templates. Mutant TTFΔN445, however, although able to bind to the ‘Sal box’ target sequence on naked DNA, fails to mediate transcription termination and activate transcription on chromatin templates (Evers et al., 1995; Längst et al., 1997). To assay the ability of the three N-terminally truncated versions of TTF-I to interact with PCAF, the respective proteins were overexpressed in Sf9 cells either alone or together with FLAG-PCAF (Figure 2). The cell lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG antibodies and the immunoprecipitates were assayed for TTF-I on western blots. Under stringent conditions, no TTF-I was retained on the anti-FLAG resin if cells were used that express TTF-I in the absence of FLAG-PCAF (lanes 4–6). In contrast, a significant amount (5%) of TTF-I present in the lysate co-precipitated with PCAF. Significantly, all three mutants exhibited similar PCAF binding capacities, indicating that the C-terminal part of TTF-I, which harbors the DNA-binding domain, mediates the interaction with PCAF.

Fig. 2. The C-terminal part of TTF-I interacts with PCAF. N-terminal His-tagged deletion mutants TTFΔN185 (lanes 1, 4 and 7), TTFΔN323 (lanes 2, 5 and 8) and TTFΔN445 (lanes 3, 6 and 9) were expressed in Sf9 cells in the presence (lanes 1–3 and 7–9) or absence (lanes 4–6) of FLAG-PCAF. PCAF was bound to M2-agarose by immunoadsorption, and associated TTF-I was identified on immunoblots with anti-TTF-I antibodies. In lanes 1–3, the amount of TTF-I present in 5% of the cell lysates is shown. A schematic representation of TTF-I is shown above. The negative regulatory domain (NRD) and the DNA-binding domain are indicated. The numbers mark amino acid positions.

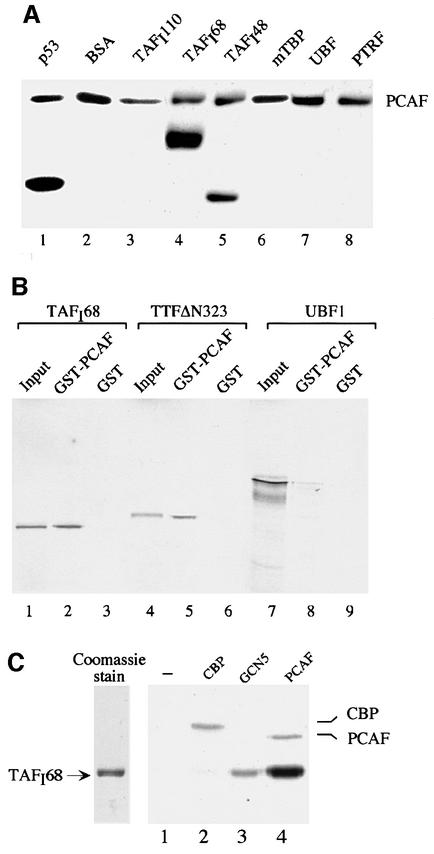

PCAF acetylates TAFI68

Having established that TTF-I is capable of interacting with PCAF, we sought to investigate whether components of the transcription initiation complex are targeted by PCAF. For this, we carried out in vitro protein acetyltransferase assays using several Pol I-specific transcription factors as substrates. Subunits of the promoter selectivity factor TIF-IB/SL1 (TAFI110, TAFI68, TAFI48 and TBP), UBF and the polymerase and transcript release factor (PTRF; Jansa et al., 1998) were expressed in Sf9 cells and purified to near homogeneity. p53, which is known to be acetylated by PCAF, was used as a positive control. Equal amounts of protein were incubated with PCAF and [3H]acetyl-CoA, and acetylated proteins were visualized by fluorography. In agreement with previous data demonstrating acetylation of p53 by PCAF (Sakaguchi et al., 1998; Liu et al., 1999), p53 was labeled efficiently in this in vitro assay (Figure 3A, lane 1). Significantly, two subunits of the promoter selectivity factor TIF-IB/SL1, i.e. TAFI68 and TAFI48, were acetylated, the acetylation of TAFI68 being ∼3-fold stronger than that of TAFI48 (lanes 4 and 5). Acetylation of TAFI68 was even more pronounced than that of p53 (lane 1), suggesting that TAFI68 is acetylated at multiple sites. None of the other proteins tested, i.e. TAFI110, TBP, UBF or PTRF, was acetylated by PCAF in vitro, demonstrating the specificity of the acetylation reaction.

Fig. 3. PCAF acetylates TAFI68 in vitro. (A) Acetylation of recombinant proteins. A 2 µg aliquot of the proteins indicated was incubated with 500 ng of FLAG-PCAF, 1 µCi of [3H]acetyl-CoA and 0.4 µM TSA in a total volume of 30 µl of buffer AM-100 for 30 min at 30°C. Proteins were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE, and acetylated proteins were visualized by fluorography. (B) TAFI68 interacts with PCAF. GST–PCAF or GST were bound to glutathione–agarose beads and incubated with 35S-labeled TAFI68 (lanes 2 and 3), TTFΔN323 (lanes 5 and 6) or UBF (lanes 8 and 9). Bound proteins were analyzed by 8% SDS–PAGE and autoradiography. Ten percent of the 35S-labeled input proteins are shown in lanes 1, 4 and 7. (C) Acetylation of TAFI68 with CBP, GCN5 and PCAF. A 500 ng aliquot of TAFI68 was incubated for 30 min at 30°C with 1 µCi of [3H]acetyl-CoA, 0.4 µM TSA and comparable units of HAT activity of CBP (lane 2), GCN5 (lane 3) or PCAF (lane 4). After gel electrophoresis, acetylated TAFI68 was visualized by fluorography. A Coomassie Blue stain of 500 ng of TAFI68 is shown on the left.

As acetylated proteins are usually associated with their respective HATs, we examined whether PCAF interacts with TAFI68. Immobilized glutathione S-transferase (GST)–PCAF was incubated with 35S-labeled TAFI68, TTF-I and UBF, respectively, and bead-bound labeled proteins were visualized by electrophoresis and autoradiography. As shown in Figure 3B, ∼10% of TAFI68 was found to be associated with GST–PCAF but not with GST control beads (lanes 1–3). The efficiency of TAFI68 binding was comparable to that of TTF-I (lanes 4–6). In contrast, almost no UBF (<1% of input) was retained on the PCAF affinity resin (lane 8). This result demonstrates that TAFI68 and TTF-I, but not UBF, interact with PCAF.

Next, we tested whether TAFI68 is specifically targeted by PCAF or whether other HATs also acetylate this subunit of TIF-IB/SL1. We therefore compared the ability of similar amounts (in terms of HAT activity) of CBP, GCN5 and PCAF to acetylate TAFI68 (Figure 3C). All three HATs modified p53 with comparable efficiency (data not shown). TAFI68, on the other hand, was acetylated efficiently by PCAF (lane 4), to a lesser extent by GCN5 (lane 3), but not by CBP (lane 2). Thus, acetylation of TAFI68 appears to be mediated by PCAF.

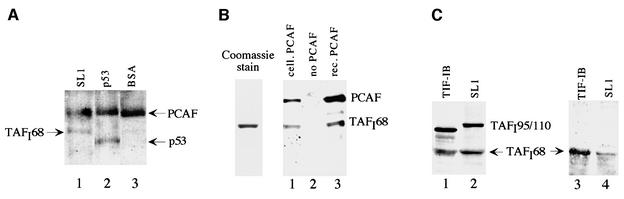

Cellular TIF-IB/SL1 contains acetylated TAFI68

As recombinant TAFI68 and TAFI48 can be acetylated by PCAF, we examined whether these subunits are accessible for acetylation within the cellular TBP–TAF complex. For this, the human factor SL1 was affinity purified, incubated with PCAF and [3H]acetyl-CoA, and [3H]acetate incorporation was monitored by fluorography (Figure 4A). As a positive control, acetylation of p53 was assayed. Consistent with TAFI68 being a bona fide substrate for PCAF, TAFI68 was labeled in the TBP–TAF complex. TAFI48, on the other hand, was not acetylated under these conditions, suggesting that the acetylation site(s) may be masked by interaction with other TAFIs or TBP.

Fig. 4. TAFI68 is acetylated in vitro and in vivo. (A) PCAF acetylates cellular SL1 in vitro. Immunopurified SL1 (lane 1), recombinant p53 (lane 2) and BSA (lane 3) were incubated with 500 ng of FLAG-PCAF and 1 µCi of [3H]acetyl-CoA, separated by 10% SDS–PAGE and acetylated proteins detected by fluorography. Autoacetylated PCAF is indicated. (B) TAFI68 is acetylated by the cellular PCAF complex. FLAG-tagged PCAF isolated from transfected NIH-3T3 cells (lane 1) or 500 ng of recombinant FLAG-PCAF purified from Sf9 cells (lane 3) was used to acetylate recombinant TAFI68 that was expressed in Sf9 cells (lane 2). Acetylation was monitored on immunoblots with α-acetyl-lysine antibodies. A Coomassie Blue stain of TAFI68 is shown on the left. (C) TAFI68 is acetylated in vivo. TIF-IB/SL1 was immunopurified from PC-1000 fractions (Schnapp and Grummt, 1996) from Ehrlich ascites (lane 1) and HeLa cells (lane 2), and subjected to western blotting using α-acetyl-lysine antibodies (lanes 3 and 4). In lanes 1 and 2, the western blot was reprobed with α-TAFI95 and α-TAFI68 antibodies.

Cellular PCAF interacts with its substrates in the context of a large multiprotein complex. To examine whether cellular PCAF would acetylate TAFI68 as well, the PCAF complex was immunopurified from NIH-3T3 cells overexpressing FLAG-tagged PCAF and used to acetylate recombinant TAFI68. As shown in Figure 4B, both the cellular PCAF complex (lane 1) and recombinant PCAF isolated from Sf9 cells (lane 3) are capable of acetylating TAFI68 (lane 2), the latter being more active than the cellular complex.

In vitro acetylation of proteins does not establish that they are substrates for modification in vivo. To determine whether acetylation of TAFI68 occurs in vivo, we used an antibody, anti-AK, which reacts with acetyl-lysine residues but not with unacetylated lysine residues (Hebbes et al., 1988). The human factor SL1 and the homologous murine factor TIF-IB were immunopurified from HeLa and Ehrlich ascites cells, respectively, and subjected to western blotting using anti-AK and anti-TAFI antibodies. As shown in Figure 4C, in both the human and mouse complex TAFI68 was recognized by the anti-AK antibodies, demonstrating that this subunit of TIF-IB/SL1 is acetylated in vivo.

Treatment with trichostatin A does not affect rRNA synthesis in cycling cells

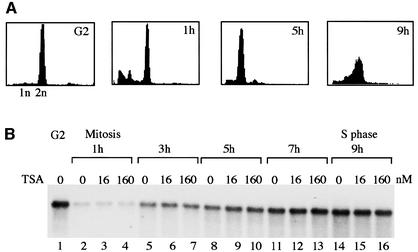

Given that TIF-IB/SL1 is acetylated in vivo, one would expect inhibition of deacetylases by butyrate or trichostatin A (TSA) to have an effect on cellular rRNA synthesis. To address this issue, pre-rRNA synthesis was monitored in FT210 cells, a murine mammary tumor cell line carrying a temperature-sensitive mutant of cdc2 (Yasuda et al., 1991). Cells were cultured in the absence or presence of TSA, and pre-rRNA synthesis was compared on northern blots using a labeled antisense RNA that hybridizes to 5′-terminal nucleotides (from +1 to +155) of mouse 45S pre-rRNA. To exclude the possibility that inhibition of deacetylases affects rDNA transcription only in distinct phases of the cell cycle, the experiment was performed with synchronized cells. Cells were synchronized at the G2–M boundary by culturing at the non-permissive temperature (39°C), and then shifted to the permissive temperature (33°C) to allow the cells to re-enter the cell cycle. In agreement with previous data (Klein and Grummt, 1999), there are drastic changes in the overall rRNA synthetic activity during cell cycle progression, being maximal at G2, shut down at mitosis and slowly recovering during progression through G1 phase (Figure 5B). However, there was no difference in pre-rRNA levels, regardless of whether the cells were cultured in the absence or presence of TSA. Thus, inhibition of TSA-sensitive deacetylases does not affect cellular pre-rRNA synthesis.

Fig. 5. TSA treatment does not affect cellular pre-rRNA synthesis. (A) FACS analysis. FT210 cells were synchronized at the G2–M boundary by shifting to 39°C for 18 h and released from the G2–M block by shifting to the permissive temperature (33°C). Aliquots of cells were subjected to FACS analysis at the times indicated. (B) Measurement of pre-rRNA synthesis. RNA was prepared from synchronized cells grown in the absence or presence of the indicated amounts of TSA, and 10 µg were used for northern blots to determine 45S pre-rRNA levels.

Acetylation augments the DNA-binding activity of TAFI68

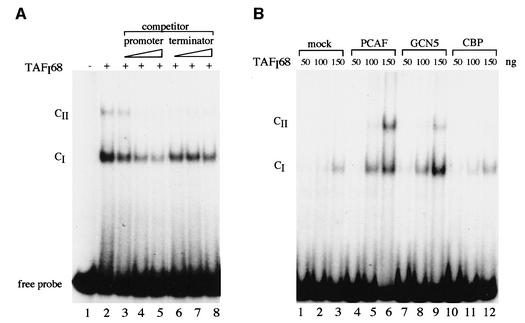

Acetylation changes the size and charge of lysine residues, and thus alters the functional properties of proteins. TAFI68 contains three zinc finger motifs, and cross-linking studies have demonstrated that it binds to the rDNA promoter (Rudloff et al., 1994; Beckmann et al., 1995; Heix et al., 1997). Given the stimulation of DNA binding activity of p53 (Gu and Roeder, 1997), MyoD (Sartorelli et al., 1999), E2F-1 (Martínez-Balbás et al., 2000), GATA-1 (Boyes et al., 1998) and HNF-4 (Soutolgou et al., 2000), we investigated whether the DNA binding properties of TAFI68 were affected by acetylation. FLAG-tagged TAFI68 was incubated with a labeled DNA fragment covering murine rDNA sequences from –54 to +7, and protein–DNA complexes were separated from free DNA by electrophoresis. As shown in Figure 6A, TAFI68 interacted with the rDNA promoter probe and formed a defined DNA–protein complex (CI). If the amounts of TAFI68 were increased, a second, more slowly migrating complex (CII) was generated (data not shown), indicating that two TAFI68 molecules have bound to DNA. The DNA–protein complex could be competed by a DNA fragment encompassing the core element of the rDNA promoter (lanes 3–5), but not by a 3′-terminal rDNA fragment containing the terminator element T1 (lanes 6–8), underscoring the sequence selectivity of TAFI68 binding.

Fig. 6. Acetylation augments binding of TAFI68 to the rDNA promoter. (A) TAFI68 binds specifically to the rDNA promoter. A 300 ng aliquot of recombinant FLAG-TAFI68 was incubated with 5 fmol of radiolabeled rDNA probe, and DNA–protein complexes were analyzed by electrophoresis on 5% native polyacrylamide gels. For competition, reactions were supplemented with 250, 500 and 1000 fmol, respectively, of an unlabeled fragment harboring sequences of either the rDNA promoter (lanes 3–5) or the rDNA terminator (lanes 6–8). (B) Binding of TAFI68 to the rDNA promoter is enhanced by acetylation. Increasing amounts (50–150 ng) of FLAG-TAFI68 were acetylated with PCAF, hGCN5 and CBP, respectively, and assayed for DNA binding by EMSA. In lanes 1–3, the reactions contained FLAG-TAFI68 alone.

To examine the effect of acetylation on the DNA-binding properties of TAFI68, recombinant TAFI68 was pre-incubated either with acetyl-CoA (mock) or with several HATs and acetyl-CoA before the DNA binding activity was assayed (Figure 6B). Consistent with the data in Figure 6A, in the absence of de novo acetylation, binding of TAFI68 to its cognate site yielded complex CI (lanes 1–3). Acetylation by PCAF increased the overall DNA binding efficiency of TAFI68, leading to enhanced formation of complex CI and generation of complex CII (lanes 4–6). Like PCAF, GCN5 augmented DNA binding and formation of complex CII (lanes 7–9), whereas CBP had no effect (lanes 10–12).

Acetylation of TAFI68 by PCAF enhances rDNA transcription in vitro

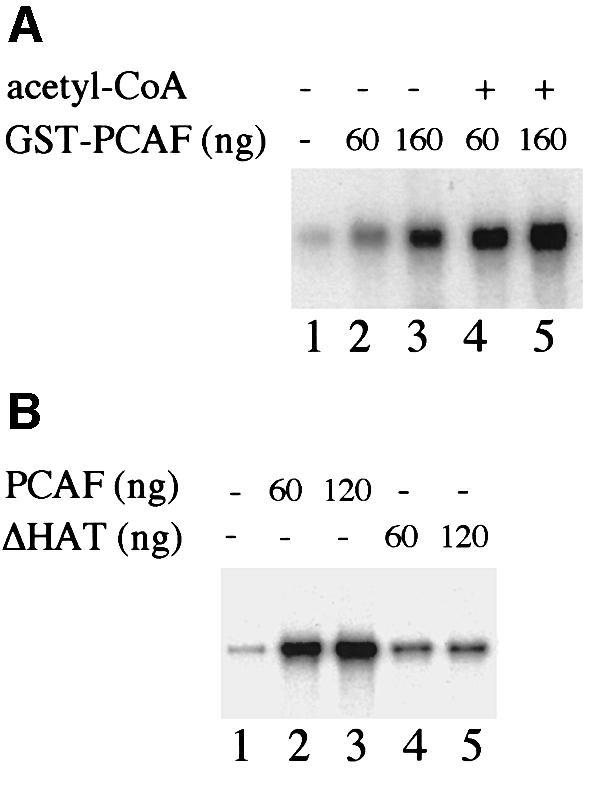

The correlation between acetylation of TAFI68 and the increase of DNA binding suggests that acetylation-induced enhancement of TIF-IB/SL1 binding could be a means that the cell may use to modulate initiation complex formation and regulate rDNA transcription. To examine whether acetylation by PCAF would stimulate Pol I transcription, we assayed the effect of GST–PCAF in a reconstituted transcription system. The system used contained low amounts of TIF-IB and, therefore, transcriptional activity was low (Figure 7A, lane 1). Addition of increasing amounts of GST–PCAF enhanced transcription 7- and 13-fold, respectively (lanes 2 and 3). In the presence of exogenous acetyl-CoA, transcription was elevated further, resulting in 15- and 17-fold activation (lanes 4 and 5).

Fig. 7. Acetylation by PCAF stimulates rDNA transcription in vitro. (A) PCAF-mediated transcriptional activation. Transcription factors and Pol I were pre-incubated in the absence (lane 1) or presence of 60 (lanes 2 and 4) and 160 ng (lanes 3 and 5) of purified GST–PCAF. Reactions 4 and 5 were supplemented with 10 µM acetyl-CoA. After pre-incubation for 30 min at 30°C, transcriptions were started by adding 20 ng of template DNA and ribonucleotides. (B) Transcriptional stimulation by PCAF requires a functional HAT domain. Transcription reactions were performed in the absence (lane 1) or presence of GST–PCAF (lanes 2 and 3) or GST–PCAF/ΔHAT (lanes 4 and 5) and 10 µM acetyl CoA as above.

The fact that significant levels of PCAF-mediated transcriptional activation were observed in the absence of exogenous acetyl-CoA suggests that either PCAF or a component(s) of the transcription system contains endogenous acetyl-CoA. To demonstrate unambiguously that transcriptional enhancement by PCAF was caused by acetylation, we compared the effect of GST–PCAF with that of GST–PCAF/ΔHAT, a mutant that lacks HAT activity, on transcriptional activity. Clearly, the mutant protein failed to activate Pol I transcription to a significant extent (Figure 7B, lanes 4 and 5). Thus, the HAT activity of PCAF is required for activation of the basal Pol I transcription apparatus.

Deacetylation by Sir2p impairs rDNA transcription in vitro

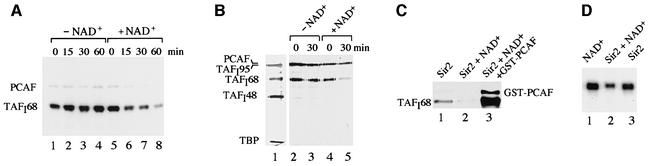

Recent studies indicated that Sir2, a highly conserved member of the family of ‘silent information regulators’ which localizes to the nucleolus, exhibits NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase activity (Imai et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2000). To examine whether mSir2a would be a candidate enzyme that deacetylates TAFI68, recombinant murine mSir2a was incubated with acetylated TAFI68 in the absence and presence of NAD+, and deacetylation was monitored on western blots using anti-AK antibodies that recognize acetylated lysines (Figure 8A). In the absence of NAD+, mSir2a did not affect the acetylation level of TAFI68 (lanes 1–4). In contrast, in the presence of NAD+, a time-dependent deacetylation of TAFI68 was observed (lanes 5–8), indicating that acetylated TAFI68 is targeted by mSir2a. In support of this, incubation of purified TIF-IB with mSir2a showed an NAD+-dependent reduction of TAFI68 acetylation, demonstrating the accessibility of acetylated lysine residues within the TBP–TAF complex (Figure 8B). Autoacetylated PCAF, on the other hand, was not deacetylated by mSir2a, consistent with specific targeting of TAFI68 by mSir2a.

Fig. 8. mSir2a deacetylates TAFI68 and decreases rDNA transcription. (A) mSir2a deacetylates TAFI68. FLAG-TAFI68 and FLAG-PCAF were co-expressed in Sf9 cells and immunopurified with α-FLAG antibodies. A 500 ng aliquot of purified protein FLAG-TAFI68 was incubated with 200 ng of recombinant mSir2a in the absence (lanes 1–4) or presence (lanes 5–8) of 1 mM NAD+ at 30°C for the times indicated. Reactions were subjected to 8% SDS–PAGE, and acetylated proteins were detected on immunoblots using α-acetyl-lysine antibodies. (B) Deacetylation of TAFI68 in the TBP–TAF complex. Recombinant TIF-IB was purified from Sf9 cells that co-expressed the three TAFIs, TBP and PCAF. A 40 ng aliquot of immunopurified complexes was incubated with 200 ng of mSir2 in the absence (lanes 2 and 3) or presence (lanes 4 and 5) of 1 mM NAD+, subjected to 11% SDS–PAGE, and acetylated proteins were visualized on immunoblots using α-acetyl-lysine antibodies. (C) Deacetylation of TAFI68 is reversed by PCAF. Acetylated TAFI68 was incubated with mSir2a immobilized on Ni+-NTA–agarose for 60 min at 30°C in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lane 2) of 1 mM NAD+. Bead-bound Sir2a was removed by centrifugation, and an aliquot of the NAD+-treated reaction was incubated with 500 ng of GST–PCAF and 10 µM acetyl-CoA (lane 3). Acetylated proteins were detected on immunoblots with α-acetyl-lysine antibodies. (D) Deacetylation by Sir2p decreases rDNA transcription in vitro. Transcription factors and RNA polymerase I were pre-incubated for 60 min at 30°C with 200 ng of purified mSir2 immobilized on Ni+-NTA–agarose in the presence (lane 2) or absence (lane 3) of 1 mM NAD+. Bead-bound mSir2a was removed, and the transcriptional activity of the supernatant was measured in the presence of ribonucleotides and template DNA. In lane 1, NAD+ was added to the transcription reaction after the pre-incubation step.

If our assumption is correct and mSir2a counteracts PCAF-mediated acetylation of TAFI68, then deacetylation by mSir2a should be reversed by PCAF. In the experiment shown in Figure 8C, TAFI68 was acetylated by co-expression with PCAF in Sf9 cells, and incubated with bead-bound mSir2a in the presence of NAD+. After removal of mSir2a, the reaction was incubated with GST–PCAF and acetyl-CoA. Clearly, mSir2a deacetylated TAFI68 (lanes 1 and 2), whereas PCAF efficiently reacetylated TAFI68 in vitro (lane 3).

If acetylation is required for rDNA transcription initiation, deacetylation by mSir2a should impair transcriptional activity. To test this, transcription reactions were pre-incubated with bead-bound mSir2a in the absence and presence of NAD+, before being assayed for transcriptional activity. As shown in Figure 8D, NAD+-dependent deacetylation by mSir2a markedly decreased transcriptional activity (lane 2). Neither mSir2a nor NAD+ alone had any effect (lanes 1 and 3). Together, these results suggest that TAFI68, a basal component of the Pol I transcription apparatus, is a relevant target of mSir2a, and deacetylation of TAFI68 (and perhaps other yet to be identified nucleolar proteins) by mSir2a may cause transcriptional silencing of the rDNA locus.

Discussion

A number of studies have demonstrated that acetylation of histones increases the accessibility of transcription factors to nucleosomal DNA and correlates with transcriptional activity in vivo (Grunstein, 1997). It is not yet known whether the acetylation of histones or basal transcription factors also plays a role in Pol I transcription. Previous studies have demonstrated that transcription on rDNA assembled into chromatin requires TTF-I (Längst et al., 1997, 1998), indicating that, in addition to its well-documented role as a transcription termination factor, TTF-I also plays an important role as a chromatin-specific transcription activator. We therefore reasoned that activation of Pol I transcription on nucleosomal templates by TTF-I may be due to recruitment of HAT and/or remodeling activity to the rDNA promoter. In support of such a recruitment model, we observed a physical association of TTF-I with PCAF in vitro and in vivo. The association with PCAF is mediated by the C-terminal half of TTF-I, which harbors the DNA-binding domain. The observation that TTF-I can target PCAF to the rDNA promoter is consistent with numerous studies demonstrating that many transcriptional activators recruit HATs to acetylate nucleosomes in the promoter region. Moreover, there is a growing body of evidence that, in addition to histones, HATs acetylate a number of non-histone proteins and transcription factors, thereby affecting diverse functions, such as DNA binding affinity, protein–protein interactions and protein stability (Kouzarides, 2000). In the present study, we show for the first time that TAFI68, a subunit of the basal Pol I transcription factor TIF-IB/SL1, is modified by acetylation and can act as a substrate for PCAF. Acetylation by PCAF in vitro and in vivo was observed with both recombinant TAFI68 and immunopurified TIF-IB/SL1. TAFI68 contains three zinc finger motifs (Heix et al., 1997), and cross-linking studies have revealed that this subunit is involved in rDNA promoter recognition (Rudloff et al., 1994; Beckmann et al., 1995).

With regard to the functional consequence of TIF-IB/SL1 acetylation, this post-translational modification strongly increases binding of TAFI68 to the rDNA promoter, indicating that acetylation facilitates and/or stabilizes TIF-IB/SL1 recruitment to the rDNA promoter. Thus, TAFI68 can be added to the list of acetyltransferase substrates whose site-specific DNA binding activity is increased. Examples of increased binding activity upon acetylation are p53, E2F1, EKLF, MyoD, GATA-1 and HNF-4 (Gu and Roeder, 1997; Boyes et al., 1998; Zhang and Bieker, 1998; Sartorelli et al., 1999; Martínez-Balbás et al., 2000; Soutoglou et al., 2000). The increase in DNA binding may be inherent to the mechanism of TIF-IB/SL1 action. Vertebrate rDNA promoters consist of two sequence elements, the core and the upstream control element (UCE). The two elements share a region of significant sequence homology and appear to exert a similar function, namely the recruitment of TIF-IB/SL1, presumably by protein–protein interaction with UBF. This homology, together with the finding that the correct spacing and helical alignment between the UCE and core are crucial for promoter function, suggests that for efficient transcription TIF-IB/SL1 has to interact with both elements. Electron microscopic imaging has shown that a dimer of UBF can loop the promoter nearly 360° (Bazett-Jones et al., 1994). This looping places the two promoter elements in close proximity which, in turn, would facilitate binding of two TBP–TAFI complexes. Our finding that TAFI68 forms a distinct slower migrating complex in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) after acetylation by PCAF is consistent with acetylation being required for binding of TIF-IB/SL1 to both elements. Moreover, acetylated lysine residues of TAFI68 might be docking sites for other components of the transcription initiation complex, e.g. UBF, Pol I, TIF-IA etc., and therefore acetylation may regulate such interactions.

An important result was that acetylation by PCAF led to a drastic increase in Pol I transcription. This transcriptional activation by PCAF is due to its ability to acetylate TIF-IB/SL1 (and perhaps other components of the Pol I transcription machinery), since a PCAF/ΔHAT mutant can not mediate this effect. However, we can not conclude at this point whether the increase in transcription is a direct consequence of increased DNA binding of TIF-IB/SL1 or promotion of protein–protein interactions involved in initiation complex formation. While this paper was in revision, acetylation of another basal Pol I transcription factor, UBF, by CBP has been described (Pelletier et al., 2000). Thus, different HATs appear to modify at least two components of the Pol I initiation complex, suggesting a universal role of HATs in class I gene transcription.

If acetylation of TIF-IB/SL1 is relevant for transcriptional activity in vivo, then one would predict an enhancing effect of the deacetylase inhibitor TSA on cellular pre-rRNA synthesis. However, we did not detect any changes in pre-rRNA synthetic activity in response to TSA treatment. This could mean that inhibition of protein deacetylation does not affect Pol I transcription in cycling cells or, alternatively, that TSA does not inhibit the histone deacetylase activity that deacetylates TIF-IB/SL1. We strongly favor the latter possibility, because Sir2 is very likely to be the enzyme that counteracts PCAF-directed acetylation of TIF-IB/SL1. Sir2 is an NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase that is not inhibited by high doses of TSA (Imai et al., 2000). Yeast Sir2 has been known to be implicated in gene silencing at the mating-type loci, telomeres and the rDNA locus (Guarente, 1999). Yeast from which all five SIR2 homologs have been deleted exhibit relatively normal levels of bulk histone acetylation (Smith et al., 2000). This result revealed that histones may not be the in vivo target of the Sir2p family and suggested that some other protein(s) associated with silent rDNA chromatin may be the relevant target of Sir2. Our data showing that mSir2a deacetylates one subunit of TIF-IB/SL1, thereby repressing Pol I transcription, support this idea. It is tempting to speculate that rDNA silencing in yeast is brought about by Sir2-mediated deacetylation of component(s) of the basal Pol I transcription machinery, presumably Rrn7, the yeast homolog of TAFI68. It is noteworthy that in the reconstituted murine Pol I transcription system, inhibition of rDNA transcription was observed on naked DNA templates, demonstrating that Sir2a does not target chromatin.

Together, the results presented here suggest a novel aspect of Pol I transcriptional activation and lead us to suggest the following working hypothesis. In the cell, TTF-I binds to its recognition site T0 160 bp upstream of transcription initiation. TTF-I recruits remodeling complexes and PCAF to the rDNA promoter. PCAF, which is known to play a pivotal role in the control of cell growth and differentiation, acetylates TIF-IB/SL1 (and perhaps other components of the Pol I transcriptional machinery) in response to diverse external signals. Acetylation is required for transcriptional activity, and deacetylation by mSir2a decreases rDNA transcription. These findings reveal a novel mechanism which the cell may use to regulate rRNA synthesis under certain physiological conditions, and may have significant implications regarding the role of Sir2 in silencing of the rDNA locus whose primary targets have been presumed to be histones.

Materials and methods

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins

Histidine-tagged TTF-I, p53 and cyclin A were expressed in baculovirus-infected Sf9 cells and purified as described (Längst et al., 1997). His-hGCN5 and His-tagged mSir2 were purified from Escherichia coli. Expression and purification of GST–PCAF(352–832), GST– PCAFΔHAT(352–608) and GST–CBP(1098–1758) were performed as described (Yang et al., 1996). FLAG-tagged proteins, e.g. TTF-I (Sander et al., 1996), TAFI68 (Heix et al., 1997), UBF (Voit et al., 1997) and PCAF (Yang et al., 1996), were purified from Sf9 cells by incubating cell lysates with anti-FLAG (M2) beads for 4 h at 4°C in buffer AM-600 [20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), protease inhibitors (complete™, Roche), 10% glycerol, 600 mM KCl] including 0.5% NP-40. After successive washes with buffers AM-1000/0.5% NP-40, AM-400/0.5% NP-40 and AM-300/0.1% NP-40, bead-bound proteins were eluted with buffer AM-300/0.1% NP-40 containing 0.4 µg/µl FLAG peptide and dialyzed against AM-100.

Protein–protein interaction experiments

FLAG-tagged recombinant proteins (FLAG-PCAF, FLAG-TTF-I and FLAG-UBF1) were immobilized on M2-agarose. Control beads were saturated with the FLAG-epitope peptide. Histidine-tagged cyclin A and TTF-I were bound to Ni2+-NTA–agarose. To pull-down associated proteins, the beads were incubated for 4 h at 4°C in buffer AM-500/0.1% NP-40 with whole-cell extracts, washed, and associated proteins were identified on immunoblots or tested for HAT activity. To monitor the interaction between PCAF and Pol I transcription factors, GST and GST–PCAF were expressed in E.coli BL21(DE3)pLysS, attached to glutathione–Sepharose (Amersham-Pharmacia), and 10 µl of packed beads containing 5 µg of GST or GST–PCAF, respectively, were incubated with 10 µl of 35S-labeled TAFI68, UBF1 or TTF-IΔN323 in 80 µl of buffer AM-120 supplemented with 0.2% NP-40 and protease inhibitors (2 µg/ml leupeptin, aprotinin and pepstatin). After incubation for 4 h at 4°C, the beads were washed four times in binding buffer, and proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE and autoradiography.

To demonstrate interaction of PCAF with TTF-I in vivo, lysates from Sf9 cells that were infected with baculoviruses encoding recombinant proteins were incubated with M2-agarose in buffer AM-300/0.5% NP-40 for 4 h at 4°C and washed with buffers AM-300/0.5% NP-40, AM-100/0.5% NP-40 and AM-100/0.1% NP-40. Bound proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and visualized on immunoblots.

Acetylation of proteins in vitro

A 0.5–2 µg aliquot of recombinant proteins was incubated for 30 min at 30°C in buffer AM-100 containing 1 µCi of [3H]acetyl-CoA (4.1 µCi/mmol, Amersham), 0.4 µM TSA and 500 ng of the respective HATs. Acetylated proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE and visualized by fluorography. The cellular PCAF complex was immunopurified from NIH-3T3 cells that had been transfected with pX-FLAG-PCAF. To determine HAT activity, the enzyme was incubated with 25 µg of core histones (Sigma) in 50 µl of 100 mM KCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF and 0.2 µCi of [3H]acetyl-CoA. After incubation for 30 min at 30°C, the reactions were spotted onto P-81 (Whatman) filters. The paper was air-dried and washed four times for 10 min at 37°C with 50 mM NaHCO3 pH 9.2. [3H]acetyl-CoA incorporation into histones was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Deacetylation by Sir2 in vitro

Acetylated TAFI68 was produced in Sf9 cells by co-expressing FLAG-tagged TAFI68 and PCAF. A 200 ng aliquot of immunopurified TAFI68 was incubated at 30°C with 200 ng of recombinant mSir2a in buffer AM-100 in the presence or absence of 1 mM NAD+. Alternatively, mSir2a bound to Ni2+-NTA–agarose (100 ng/µl of beads) was used for deacetylation. Deacetylase activity was determined by incubating mSir2a with 3H-acetylated histones in 200 µl of 25 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA at 37°C for 30 min in the absence or presence of 1 mM NAD+. Released acetate was extracted and counted in a liquid scintillation counter (Wade et al., 1999). Acetylation and deacetylation of TAFI68 was monitored on immunoblots using α-acetyl-lysine antibodies (New England Biolabs).

Purification of TIF-IB/SL1

Extracts from mouse or human cells were fractionated by chromatography on phosphocellulose, and TIF-IB/SL1 was purified from the high salt eluate (PC-1000 fraction) as described (Rudloff et al., 1994). The PC-1000 fraction was incubated for 2 h at 4°C with anti-TBP antibodies (3G3; Brou et al., 1993) bound to magnetic beads (Dynal), the beads were washed with buffers AM-1000/0.1% NP-40, AM-700/0.1% NP-40, AM-300/0.1% NP-40 and resolved in buffer AM-100.

RNA analysis from TSA-treated cells

FT210 cells (Yasuda et al., 1991) were cultured at the permissive temperature (33°C) in RPMI 1640 medium containing 5% newborn calf serum. For synchronization, cells were arrested in G2 by incubation for 18 h at the non-permissive temperature (39°C), allowed to re-enter the cell cycle by shifting to 33°C and cultured for 1–9 h in the absence or presence of TSA. For fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, 1 × 106 cells were fixed and stained with propidium iodide. To monitor pre-rRNA synthesis, cellular RNA was separated on 1% MOPS-formaldehyde gels, blotted onto nylon filters and hybridized with a 32P-labeled antisense RNA encompassing 5′-terminal rDNA sequences from –170 to +155. Hybridization was performed in 50% formamide, 5× SSC, 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5, 8× Denhardt’s, 0.5 mg/ml yeast RNA, 0.1% SDS at 65°C for 16 h. The filters were washed in 0.2× SSC, 0.1% SDS at 65°C and exposed for autoradiography.

In vitro transcription assays

Transcription reactions (25 µl) contained 20 ng of template pMrWT/NdeI (Wandelt and Grummt, 1983) in 12 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 80 mM KCl, 12% glycerol, 0.66 mM of each ATP, CTP and GTP, 0.01 mM UTP and 1 µCi of [α-32P]UTP. The fractionation scheme for purification of murine Pol I and Pol I-specific transcription factors has been described (Schnapp and Grummt, 1996). TIF-IB activity was monitored in a reconstituted transcription system containing 4 µl of partially purified Pol I (H-400), 2 µl of TIF-IA/TIF-IC (QS-fraction) and 10 ng of FLAG-tagged UBF1 purified from Sf9 cells.

To assay the effect of PCAF on rDNA transcription, the reaction mixture was pre-incubated for 30 min at 30°C with GST–PCAF and 10 µM acetyl-CoA. Transcription was started by adding 20 ng of pMrWT/NdeI and ribonucleotides. For deacetylation, transcription factors and 500 ng of bead-bound mSir2a were pre-incubated for 60 min at 30°C in 12 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 80 mM KCl and 12% glycerol in the absence or presence of 1 mM NAD+. Bead-bound mSir2a was removed by centrifugation, and aliquots of the supernatant were tested in the in vitro transcription system.

EMSAs

Five femtomoles of a 32P-labeled fragment encompassing murine rDNA sequences from –54 to +7 (with respect to the initiation site) and increasing amounts of FLAG-TAFI68 were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 80 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 100 ng of bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 100 ng of poly(dA–dT). DNA–protein complexes were analyzed on 5% native polyacrylamide gels. For competition, a double-stranded oligonucleotide encompassing the murine terminator T1 (5′-GATCCTTCGGAGGTCGACCAGTACTCCGGGCGACA-3′) or the murine rDNA promoter (–54 to +7) was used.

Antibodies

Antibodies against mTTF-I (Evers et al., 1995), UBF (Voit et al., 1997), TBP (3G3; Brou et al., 1993), TAFI48, TAFI68 and TAFI95 (Heix et al., 1997), and PCAF (Yang et al., 1996) were used. Antibodies against cyclin A and the FLAG epitope (M2) were purchased from Santa Cruz and Sigma, respectively. Acetylated lysine antisera (anti-AK) were obtained from New England Biolabs or provided by C.Crane-Robinson.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank N.Wagner for technical assistance, Y.Nakatani for baculoviruses encoding FLAG-PCAF, various plasmids for PCAF and antibodies against PCAF, L.Tora for antibodies against TBP, M.Ott for purified GST–CBP, C.Crane-Robinson for anti-acetyl-lysine antiserum, S.Berger for pRSET-hGCN5, S.-I.Imai for the pET-mSir2a plasmid and P.Loidl for radiolabeled histones. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. S.N was supported in part by the French Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale.

References

- Bazett-Jones D.P., Leblanc,B., Herfort,M. and Moss.T. (1994) Short-range DNA looping by the Xenopus HMG-box transcription factor, xUBF. Science, 264, 1134–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann H., Chen,J.L., O’Brien,T. and Tjian,R. (1995) Coactivator and promoter-selective properties of RNA polymerase I TAFs. Science, 270, 1506–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes J., Byfield,P., Nakatani,Y. and Ogryzko,V. (1998) Regulation of activity of the transcription factor GATA-1 by acetylation. Nature, 396, 594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brou C., Chaudhary,S., Davidson,I., Lutz,Y., Wu,J., Egly,J.M., Tora,L. and Chambon,P. (1993) Distinct TFIID complexes mediate the effect of different transcriptional activators. EMBO J., 12, 489–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers R., Smid,A., Rudloff,U., Lottspeich,F. and Grummt,I. (1995) Different domains of the murine RNA polymerase I-specific termination factor mTTF-I serve distinct functions in transcription termination. EMBO J., 14, 1248–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunstein M. (1997) Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature, 389, 349–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W. and Roeder,R.G. (1997) Activation of p53 sequence-specific DNA binding by acetylation of the p53 C-terminal domain. Cell, 90, 595–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L. (1999) Diverse and dynamic functions of the Sir silencing complex. Nature Genet., 23, 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbes T.R., Thorne,A.W. and Crane-Robinson,C.A. (1988) A direct link between core histone acetylation and transcriptionally active chromatin. EMBO J., 7, 1395–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heix J., Zomerdijk,J.C.B.M., Ravanpay,A., Tjian,R. and Grummt,I. (1997) Cloning of murine RNA polymerase I-specific TAF factors: conserved interactions between the subunits of the species-specific transcription initiation factor TIF-IB/SL1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 1733–1738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera J.E., Sakaguchi,K., Bergel,M., Trieschmann,L., Nakatani,Y. and Bustin,M. (1999) Specific acetylation of chromosomal protein HMG-17 by PCAF alters its interaction with nucleosomes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 3466–3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai S., Armstrong,C.M., Kaeberlein,M. and Guarente,L. (2000) Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature, 403, 795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhof A., Yang,X., Ogryzko,V., Nakatani,Y., Wolffe,A. and Ge,H. (1997) Acetylation of general transcription factors by histone acetyltransferase. Curr. Biol., 7, 689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansa P., Mason,S.W., Hoffmann-Rohrer,U. and Grummt,I., (1998) Cloning and functional characterization of PTRF, a novel protein which induces dissociation of paused ternary transcription complexes. EMBO J., 17, 2855–2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadonaga J.T. (1998) Eukaryotic transcription: an interlaced network of transcription factors and chromatin modifying machines. Cell, 92, 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein J. and Grummt,I. (1999) Cell cycle-dependent regulation of RNA polymerase I transcription: the nucleolar transcription factor UBF is inactive in mitosis and early G1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 96, 6096–6101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. (2000) Acetylation: a regulatory modification to rival phosphorylation? EMBO J., 19, 1176–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Längst G., Blank,T., Becker,P. and Grummt,I. (1997) RNA polymerase I transcription on nucleosomal templates: the transcription termination factor TTF-I induces chromatin remodeling and relieves transcriptional repression. EMBO J., 16, 760–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Längst G., Becker,P. and Grummt,I. (1998) TTF-I determines the chromatin architecture of the active rDNA promoter. EMBO J., 17, 3135–3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Sclonick,D.M., Trievel,R.C., Zhang,H.B., Marmorstein,R., Halazonetis,T.D. and Berger,S.L. (1999) p53 sites acetylated in vitro by PCAF and p300 acetylated in vivo in response to DNA damage. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 1202–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Balbás M.A., Bauer,U.-M., Nielsen,S.J., Brehm,A. and Kouzarides,T. (2000) Regulation of E2F1 activity by acetylation. EMBO J., 19, 662–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi N., Merika,M., Yie,J., Senger,K., Chen,G. and Thanos,D. (1998) Acetylation of HMGI(Y) by CBP turns off IFN expression by disrupting the enhanceosome. Mol. Cell, 2, 457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazin M.J. and Kadonaga,J.T. (1997) What’s up and down with histone deacetylation and transcription? Cell, 89, 325–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier G., Stefanovsky,V.Y., Faubladier,M., Hirschler-Laszkiewicz,I., Savard,J., Rothblum,L.I., Coté,J. and Moss,T. (2000) Competitive recruitment of CBP and Rb-HDAC regulates UBF acetylation and ribosomal transcription. Mol. Cell, 6, 1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudloff U., Eberhard,D., Tora,L., Stunnenberg,H. and Grummt,I. (1994) TBP-associated factors interact with DNA and govern species specificity of RNA polymerase I transcription. EMBO J., 13, 2611–2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorelli V., Puri,P.L., Hamamori,Y., Ogryzko,V., Chung,G., Nakatani,Y., Wang,J.Y.J. and Kedes,L. (1999) Acetylation of MyoD is necessary for the execution of the muscle program. Mol. Cell, 4, 725–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi K., Herrera,J.E., Saito,S., Miki,T., Bustin,M., Vassilev,A., Anderson,C.W. and Appella,E. (1998) DNA damage activates p53 through a phosphorylation–acetylation cascade. Genes Dev., 12, 2831–2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander E., Mason,S., Munz,C. and Grummt,I. (1996) The amino-terminal domain of the transcription termination factor TTF-I causes protein oligomerization and inhibition of DNA binding. Nucleic Acids Res., 24, 3677–3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheridan P.L., Mayall,T.P., Verdin,E. and Jones,K.A. (1997) Histone acetyltransferases regulate HIV-1 enhancer activity in vitro. Genes Dev., 11, 3327–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnapp A. and Grummt,I. (1996) Purification, assay and properties of RNA polymerase I and class I-specific transcription factors. Methods Enzymol., 273, 233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.S. et al. (2000) A phylogenetically conserved NAD+-dependent protein deacetylase activity in the Sir2 protein family. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 6658–6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soutoglou E., Katrakili,N. and Talianidis,I. (2000) Acetylation regulates transcription factor activity at multiple levels. Mol. Cell, 5, 745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl K. (1998) Histone acetylation and transcriptional regulatory mechanisms. Genes Dev., 12, 599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lint C., Emiliani,S. and Verdin,E. (1996) The expression of a small fraction of cellular genes is changed in response to histone hyperacetylation. Gene Expr., 5, 245–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voit R., Schäfer,K. and Grummt,I. (1997) Mechanism of repression of RNA polymerase I transcription by the retinoblastoma protein. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 4230–4237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade P.A. and Wolffe,A.P. (1997) Histone acetyltransferases in control. Curr. Biol., 7, R82–R84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade P.A., Jones,P.L., Vermaak,D. and Wolffe,A.P. (1999) Purification of a histone deacetylase complex from Xenopus laevis: preparation of substrates and assay procedures. Methods Enzymol., 304, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltzer L. and Bienz,M. (1998) Drosophila CBP represses the transcription factor TCF to antagonize wingless signalling. Nature, 395, 521–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandelt C. and Grummt,I. (1983) Formation of stable preinitiation complexes is a prerequisite for ribosomal DNA transcription in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res., 11, 3795–3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. (1997) Chromatin remodeling and the control of gene expression. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 28171–28174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Ogryzko,V.V., Nishikawa,J., Howard,B.H. and Nakatani,Y. (1996) A p300/CBP-associated factor that competes with the adenoviral oncoprotein E1A. Nature, 382, 319–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda H., Kamijo,M., Honda,R., Nakamura,M., Hanaoka,F. and Ohba,Y. (1991) A point mutation in C-terminal region of cdc2 kinase causes a G2-phase arrest in a mouse temperature-sensitive FM3A cell mutant. Cell Struct. Funct., 16, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W. and Bieker,J.J. (1998) Acetylation and modulation of erythroid Krüppel-like factor (EKLF) activity by interaction with histone acetyltransferases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 9855–9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]