Abstract

Portal hypertension is one of the main consequences of cirrhosis. It results from a combination of increased intrahepatic vascular resistance and increased blood flow through the portal venous system. The condition leads to the formation of portosystemic collateral veins. Esophagogastric varices have the greatest clinical impact, with a risk of bleeding as high as 30% within 2 years of medium or large varices developing. Ascites, another important complication of advanced cirrhosis and severe portal hypertension, is sometimes refractory to treatment and is complicated by spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome. We describe the pathophysiology of portal hypertension and the current management of its complications, with emphasis on the prophylaxis and treatment of variceal bleeding and ascites.

Portal hypertension is one of the main consequences of cirrhosis. It can result in severe complications, including bleeding of esophagogastric varices as well as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis or hepatorenal syndrome as complications of ascites. We describe in brief the pathophysiology of portal hypertension and review the current management of its complications, with emphasis on variceal bleeding and ascites.

Pathophysiologic background

Portal hypertension

Portal hypertension is defined as an increase in blood pressure in the portal venous system. The portal pressure is estimated indirectly by the hepatic venous pressure gradient — the gradient between the wedged (or occluded) hepatic venous pressure and the free hepatic venous pressure. A normal hepatic venous pressure gradient is less than 5 mm Hg.

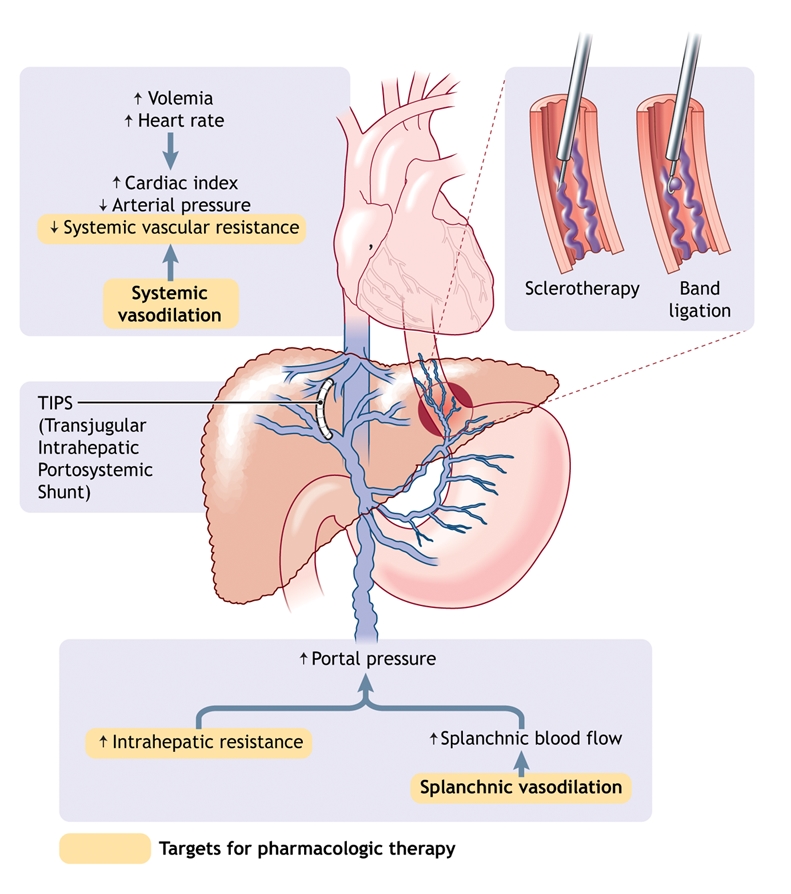

In cirrhosis, portal hypertension results from the combination of increased intrahepatic vascular resistance and increased blood flow through the portal venous system (Fig. 1). According to Ohm's law, portal venous pressure (P) is the product of vascular resistance (R) and blood flow (Q) in the portal bed (P = Q × R). Intrahepatic resistance increases in 2 ways: mechanical and dynamic. The mechanical component stems from intrahepatic fibrosis development; various pathologic processes are thought to contribute to increased intrahepatic resistance at the level of the hepatic microcirculation (sinusoidal portal hypertension): architectural distortion of the liver due to fibrous tissue,1 regenerative nodules,1 and collagen deposition in the space of Disse.2 The dynamic component results from a vasoconstriction in portal venules secondary to active contraction of portal and septal myofibroblasts, to activated hepatic stellates cells and to vascular smooth-muscle cells.3–5 Intrahepatic vascular tone is modulated by endogenous vasoconstrictors (e.g., norepinephrine, endothelin-1, angiotensin II, leukotrienes and thromboxane A2) and enhanced by vasodilators (e.g., nitric oxide). In cirrhosis, increased intrahepatic vascular resistance results also from an imbalance between vasodilators and vasoconstrictors.6

Fig. 1: Pathophysiology of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Portal hypertension results from increased intrahepatic vascular resistance and portal–splanchnic blood flow. In addition, cirrhosis is characterized by splanchnic and systemic arterial vasodilation. Splanchnic arterial vasodilation leads to increased portal blood flow and thus elevated portal hypertension. An increased hepatic venous pressure gradient leads to the formation of portosystemic venous collaterals. Esophagogastric varices represent the most clinically important collaterals given their associated high risk of bleeding. Treatment consists of pharmacologic therapy to decrease portal pressure, endoscopic treatment of varices (band ligation or sclerotherapy) to treat variceal bleeding, and creation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) to reduce portal pressure if drug therapy and endoscopic treatment fail.

Portal hypertension is characterized by increased cardiac output and decreased systemic vascular resistance,7 which results in a hyperdynamic circulatory state with splanchnic and systemic arterial vasodilation. Splanchnic arterial vasodilation leads to increased portal blood flow, which in turn leads to more severe portal hypertension. Splanchnic arterial vasodilation results from an excessive release of endogenous vasodilators such as nitric oxide, glucagon and vasointestinal active peptide.

An increase in the portocaval pressure gradient leads to the formation of portosystemic venous collaterals in an attempt to decompress the portal venous system. Esophageal varices, drained predominantly by the azygos vein, are clinically the most important collaterals because of their propensity to bleed. Esophageal varices can develop when the hepatic venous pressure gradient rises above 10 mm Hg.8–10 All factors that increase portal hypertension can increase the risk of variceal bleeding, including deterioration of liver disease,11 food intake,12,13 ethanol intake,14 circadian rhythms,15 physical exercice16 and increased intra-abdominal pressure.17 Factors that alter the variceal wall, such as ASA and other NSAIDs, could also increase the risk of bleeding.18,19 Bacterial infection can promote initial and recurrent bleeding.20

Ascites and hepatorenal syndrome

In advanced cirrhosis, splanchnic arterial vasodilation promoted by portal hypertension is pronounced and leads to the impairment of systemic and splanchnic circulation.21 Systemic vasodilation leads to relative hypovolemia, with a decrease in effective blood volume and a fall in mean arterial pressure. States of homeostasis and antinatriuresis are activated to maintain arterial pressure, which results in sodium and fluid retention.21 In addition, a combination of portal hypertension and splanchnic arterial vasodilation alters splanchnic microcirculation and intestinal permeability, facilitating the leakage of fluid into the abdominal cavity.21 As cirrhosis progresses, the kidneys' ability to excrete sodium and free water is impaired; sodium retention and ascites develop when the amount of sodium excreted is less than the amount consumed.21 Decreased free water excretion leads to dilutional hyponatremia and eventually to impaired renal perfusion and hepatorenal syndrome.21

Variceal bleeding

Variceal bleeding is a medical emergency associated with high rates of recurrence and death.22–25 Its management is based on specific treatments, including pharmacologic therapy, endoscopic treatment and antibiotic therapy.

Pharmacologic therapy

Vasopressin and its analogue terlipressin: Vasopressin is a potent splanchnic vasoconstrictor; however, its use was abandoned 25 years ago in most countries because of its severe vascular side effects. Terlipressin, a vasopressin analogue not currently licensed for use in Canada, has similar effects,26 reducing the hepatic venous pressure gradient, variceal pressure and azygos blood flow.27,28 Terlipressin has been found to be superior to placebo in the control of variceal bleeding.29 It has also been found to decrease renal vasoconstrictor system activity and improve renal function in patients with hepatorenal syndrome.30–33 However, terlipressin can induce ischemic complications, particularly in cases of severe hypovolemic shock,34 and it is contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular disease (arterial disease with severe obstruction, cardiac insufficiency, arrhythmias, hypertension).

Somatostatin and its analogues octreotide and vapreotide: Somatostatin significantly reduces the hepatic venous pressure gradient,35–37 variceal pressure38 and azygos blood flow;36 however, because its hemodynamic effect is transient, continuous infusion is required.36 Four placebo-controlled studies showed contrasting results. Somatostatin was more effective than placebo in controlling variceal bleeding,39,40 but its effectiveness in reducing the need for transfusion41,42 and balloon tamponade41 remains unproven. Terlipressin appears to be as effective as somatostatin in the control of bleeding.29

Octreotide and vapreotide have a longer half-life than somatostatin and are useful in the management of portal hypertension. Octreotide decreases the hepatic venous pressure gradient and azygos blood flow43–46 but not variceal pressure.27,47 However, the effect of octreotide is transient43–46 and controversial.48 It prevents the increase in hepatic blood flow after a meal,49 and it seems to be as efficient as terlipressin in treating variceal bleeding and in improving the efficacy of endoscopic therapy.50–52 Only one double-blind randomized controlled trial of octreotide has been published (in brief) to date, and it showed that octreotide was not more effective than placebo in controlling and preventing early recurrent variceal bleeding.53 In a randomized controlled trial, vapreotide, a long-acting analogue of somatostatin not currently licensed for use in Canada, was administered before endoscopic treatment and was found to result in fewer blood transfusions and better control of bleeding than endoscopic treatment alone.54

No major toxic effects and practically no complications are associated with the use of somatostatin or its analogues.

Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment

Endoscopy is useful in the diagnosis and treatment of bleeding esophagogastric varices. Three endoscopic techniques are currently used: endoscopic band ligation, endoscopic sclerotherapy and variceal obturation with glue.

Endoscopic band ligation: Currently, endoscopic band ligation is the first choice of endoscopic treatment for esophagogastric varices. The procedure involves placing an elastic band on a varix, which allows aspiration of the varix in a cylinder attached to an endoscope. A maximum of 5–8 elastic bands should be used per session. Sessions should be performed every 2–3 weeks until the varices have been obliterated or have become so small that ligation is impossible.55 Complications of endoscopic band ligation are fewer than those with endoscopic sclerotherapy. Generally, bleeding from a post-ligation ulcer is moderate.56

Endoscopic sclerotherapy: There are several sclerosant agents (polidocanol, ethanolamine, ethanol, tetradecyl sulfate and sodium morrhuate), and they provide similar results. The treatment involves intravariceal or paravariceal injections of the sclerosant agent (total volume 10–30 mL per session) every 1–3 weeks until the varices have been obliterated.56 Given that varices recur in 50%–70% of cases,57 surveillance endoscopy every 3–6 months is required.57,58 Frequent complications of endoscopic sclerotherapy are retrosternal pain, dysphagia and postsclerotherapy bleeding ulcers. More severe complications, such as esophageal perforation or stricture, have been reported.56

Variceal occlusion with glue: This treatment is especially useful in patients who have had gastric or gastroesophageal variceal bleeding. It consists of embolization of varices by injecting them with the tissue adhesive N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate; the adhesive polymerizes in contact with blood. One millilitre of adhesive is injected at a time, with a maximum of 3 injections per session. The most serious risk associated with this procedure is embolization of the lung, spleen or brain.59

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Percutaneous creation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) through a jugular route connects the hepatic and portal veins in the liver. The goal is to reduce portal pressure and thus prevent variceal bleeding.60 TIPS diverts portal blood flow from the liver, but it increases the risk of encephalopathy.61–63 In most cases encephalopathy responds to standard therapy, but in some cases the calibre of the shunt has to be reduced;60 rarely, when encephalopathy does not respond to treatment (in 5% of cases) the shunt should be occluded.60 Thrombosis and stenosis are other complications that can cause TIPS dysfunction.60 Recently, it has been reported that the use of a polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent decreases the rate of shunt dysfunction.64 The putative increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma remains to be clarified.

Other treatment options

Balloon tamponade: In cases of massive or uncontrolled bleeding, balloon tamponade provides a “bridge” to definitive treatment with TIPS or portosystemic surgical shunt.55,65 The most frequently used balloon is the 4-lumen modified Sengstaken–Blakemore tube, which employs a gastric and esophageal balloon.56 In cases of bleeding gastric varices, use of the Linton–Nachlas tube with a large gastric balloon is recommended.56

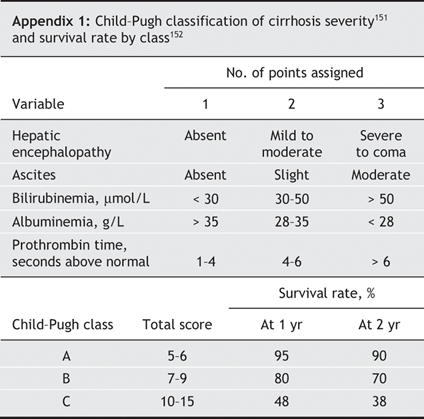

Portosystemic surgical shunt: Its usefulness has dramatically decreased since the advent of TIPS. Moreover, the procedure requires an experienced surgeon. In cases of refractory bleeding and when TIPS is technically impossible, creation of a nonselective portosystemic shunt may be suitable in patients with cirrhosis provided that the liver dysfunction is not too severe (Child–Pugh class A or B, Appendix 1).

Practical management

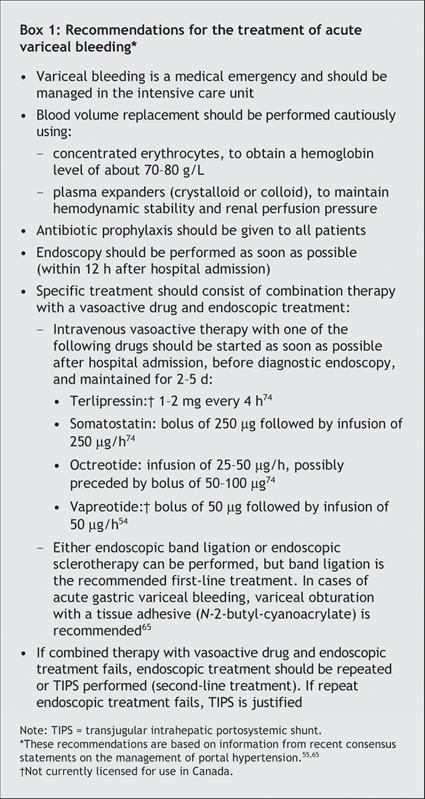

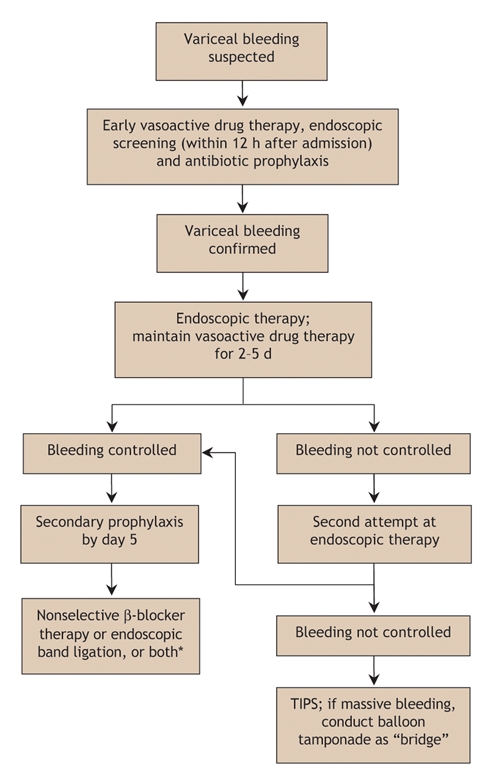

Variceal bleeding should be managed in an intensive care unit.55 Treatment should include nonspecific therapy, such as blood volume replacement and antibiotic prophylaxis, as well as specific treatments, such as pharmacologic therapy and endoscopic treatment (Box 1, Fig. 2).

Box 1.

Fig. 2: Algorithm for the treatment of variceal bleeding. TIPS = transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. *The therapeutic option depends on what was done in primary prophylaxis.

Nonspecific treatment

Nonspecific treatment aims to correct hypovolemia and to prevent complications. Blood volume replacement should be done cautiously using concentrated erythrocytes to obtain a hemoglobin level of about 70–80 g/L.55,65 Overtransfusion should be avoided given the risk of increased portal pressure37,66,67 and continued or recurrent bleeding.68 Plasma expanders are used to maintain hemodynamic stability and renal perfusion pressure.55,65 Either a crystalloid (isotonic saline solution) or colloid solution can be used, but a crystalloid solution is preferred because it is harmless.55

Infection occurs in 25%–50% of patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding.69 Failure to control bleeding and rates of death are increased in infected patients.69,70 The early administration of antibiotic prophylaxis will benefit all patients with variceal bleeding and improve survival.55,65,71,72 One recommended protocol is oral administration of norfloxacin (400 mg twice daily for 7 days).55,73

The routine use of a nasogastric tube is not recommended. Patients with encephalopathy should be given lactulose;65 however, insufficient information exists to recommend its use in the prevention of hepatic encephalopathy.55,65

Specific treatment

Intravenous therapy with a vasoactive drug should be started as soon as possible following hospital admission, before diagnostic endoscopy, and maintained for 2–5 days (Box 1).54,55,65,74 Vasopressin is not recommended because of its deleterious side effects.

Endoscopy should be performed within 12 hours after hospital admission on an empty stomach, which can be achieved by either intravenous injection of erythromycin (250 mg begun 30–60 minutes before endoscopy) or lavage through a nasogastric tube.55,65 Endoscopy is useful in confirming the source of bleeding and allowing hemostatic treatment. Either endoscopic band ligation or endoscopic sclerotherapy may be used.55,65 However, endoscopic band ligation is the recommended first-line treatment.65 In patients who have bled from gastric or gastroesophageal varices, endoscopic obliteration with the tissue adhesive N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate should be performed.65 However, endoscopic band ligation is also possible to treat gastroesophageal varices.

If combined vasoactive and endoscopic therapy fails, a second attempt at endoscopic therapy is justified if the bleeding is mild and the prognosis not compromised.55,65,75 TIPS is a second-line treatment option.65 Balloon tamponade can be used as a “bridge” in cases of massive bleeding.55,65 If bleeding persists or compromises prognosis, TIPS or surgical shunt creation should be offered as a rescue therapy.55,65

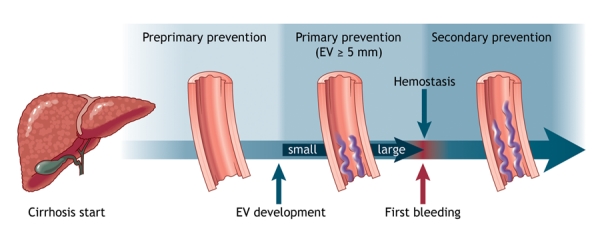

Esophagogastric varices

At present, there is no satisfactory nonendoscopic indicator to detect the presence of esophagogastric varices.65,76 Endoscopic screening is the best technique.76,77 The goal of management is to prevent variceal bleeding. This is achieved in 3 ways: by preventing the development of varices (preprimary prophylaxis), by preventing a first variceal bleeding episode once varices have developed (primary prophylaxis) and by preventing recurrent bleeding (secondary prophylaxis) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Preprimary prophylaxis is aimed at preventing esophagogastric varices (EV) from developing. The goal of primary prophylaxis is to prevent a first variceal bleeding episode once medium or large varices have formed. Secondary prophylaxis is used to prevent recurrent variceal bleeding.

Pharmacologic therapy

Pharmacologic therapy is used to control and prevent variceal bleeding. The 2 classes of drugs used are β-blockers and nitrates.

β-Blockers: β-Blockers lower portal pressure by reducing portal blood flow. The blood flow is reduced as a consequence of decreased cardiac output (β1 receptor blockade) and arteriolar splanchnic vasoconstriction by an unopposed α-vasoconstrictive effect (β2 receptor blockade).78 Nonselective β-blockers such as propranolol, nadolol and timolol are more effective than selective β1-blockers in reducing the hepatic venous pressure gradient.79,80 The median reduction of the gradient by nonselective β-blockers is about 15%.79,81–84 Nonselective β-blockers reduce variceal pressure85 and azygos blood flow86–88 even in patients who do not exhibit a marked decrease in the hepatic venous pressure gradient (propranolol “nonresponders”).87,89 Propranolol has been found to prevent increases in portal pressure related to physical exercise in patients with cirrhosis90 and to decrease the rate of bacterial translocation.91 It has also been found to reduce postprandial peak in portal pressure;92 however, this effect with long-term use was not confirmed in 2 recent trials.93,94

It has been suggested that the hepatic venous pressure gradient could be measured to evaluate the efficiency of β-blocker treatment.95 Several studies have shown that variceal bleeding does not occur if the gradient is reduced to below 12 mm Hg81,96 or that bleeding occurs at a low rate if the gradient is reduced by at least 20% of the basal value.96–99 However, the prognostic value of the hepatic venous pressure gradient on survival is still controversial.100,101 Besides, the measurement of the gradient is invasive and not cost-effective; its use is not recommended in clinical practice and is limited to selected hospitals.76

Nitrates: The mechanism of the vasodilatory effects of nitrates — vascular tone reduction and decreased intrahepatic resistance — is not completely understood. It likely involves nitric oxide release. Isosorbide mononitrate is the only nitrate that has been tested in randomized trials. It has been found to reduce the hepatic venous pressure gradient102 and to enhance the splanchnic hemodynamic effect of propranolol.103 However, its systemic effects can lead to deleterious arterial hypotension. Nitrates are used in association with vasopressin or its analogue terlipressin.

Preprimary prophylaxis

Three clinical trials have studied this issue, but the results are not concordant.104–106 According to a statement from the Baveno international consensus conference, the use of β-blocker therapy is not recommended for preprimary prophylaxis.65

Primary prophylaxis

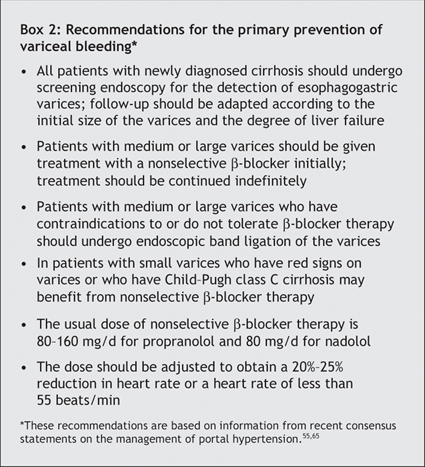

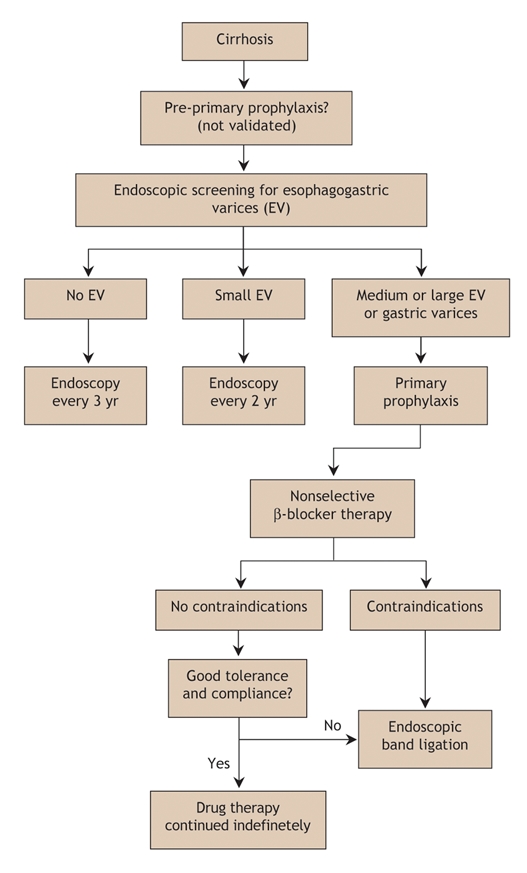

Endoscopic screening for the presence of esophagogastric varices should be done in all patients after the diagnosis of cirrhosis (Box 2).55,65 Screening should be repeated every 3 years in patients without varices and every 2 years in those with small varices (Fig. 4).55 Endoscopic follow-up should then relate to the initial size of detected varices. In case of large varices, endoscopic follow-up is not necessary, and primary prophylaxis with a nonselective β-blocker (propranolol or nadolol) should be started.55 Endoscopic band ligation is useful in preventing variceal bleeding in patients with medium or large varices; however, its long-term benefit requires further research,65 and it is not currently proposed for use in primary prophylaxis unless the patient has contraindications to or side effects from nonselective β-blocker therapy.

Box 2.

Fig. 4: Algorithm for the primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis.

Therapy with a nonselective β-blocker is effective in reducing the risk of a first variceal bleeding episode in patients with medium or large varices.65,107–111 Conventional treatment consists of administering the drug orally twice daily and titrating the dose according to the patient's tolerance and to the treatment objectives based on heart rate response.112,113 However, results of a pharmacodynamic study suggested that a single daily dose of long-acting propanolol is sufficient114 (80 or 160 mg, depending on the available dose in each country115). In all cases, doses should be adjusted to obtain a 20%–25% reduction in heart rate or a heart rate of less than 55 beats/min.55 Propranolol is effective for a few days in cirrhotic patients after the last dose is administered.114 β-Blocker therapy should be maintained indefinitely,55 since late withdrawal can be deleterious on survival despite the lack of an increased risk of bleeding.116 In patients who do not tolerate or have contraindications to β-blocker therapy, endoscopic band ligation is recommended55,65 (Fig. 4). Nitrates (isosorbide mononitrate) are ineffective in preventing variceal bleeding if used alone,117,118 and their use in primary prophylaxis is not recommended.55,65

Secondary prophylaxis

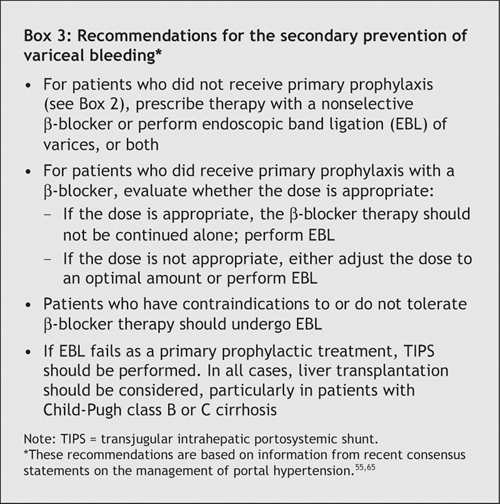

All patients who survive a variceal bleeding episode should receive treatment to prevent recurrent episodes. As a first-line treatment, both pharmacologic and endoscopic treatments can be used to prevent a recurrence. Pharmacologic therapy includes use of a nonselective β-blocker.111,119–122 Although it has been proposed,123 combined treatment with isosorbide mononitrate and propranolol is not recommended.55,65

Eradication of varices by endoscopic procedures is also effective in preventing recurrent variceal bleeding. Only endoscopic sclerotherapy has been compared with placebo, and it was associated with a significant reduction in recurrent bleeding and mortality.56,124 Endoscopic band ligation is currently preferable to endoscopic sclerotherapy,55 since it has been found to be more effective in reducing the risk of recurrent variceal bleeding and the incidence of variceal stricture.125–127 Combined therapy with the 2 endoscopic procedures does not appear to be more effective than endoscopic band ligation alone.128 However, endoscopic sclerotherapy may be effective in preventing the recurrence of varices when endoscopic band ligation is no longer feasible. One trial of endoscopic band ligation with and without therapy with nadolol and sucralfate for secondary prophylaxis showed reduced rates of recurrent variceal bleeding in the group given the combined therapy.129 Such a beneficial effect was not confirmed for combined therapy with endoscopic sclerotherapy and nonselective β-blockers.130,131

If secondary prophylaxis with a nonselective β-blocker or endoscopic band ligation, or both, fails to prevent variceal bleeding, rescue therapies should be considered. Both TIPS and surgical shunt creation are effective in preventing recurrent variceal bleeding.125 TIPS is more effective than endoscopic treatment,132 and surgical shunt creation is more effective than endoscopic sclerotherapy;133 however, neither TIPS nor surgical shunt creation has been found to improve survival, and both are associated with a high risk of encephalopathy.132,133

The 2 consensus statements on portal hypertension55,65 have established recommendations on prophylaxis status before variceal bleeding (Box 3). In patients who have not received previous primary prophylaxis, therapy with a nonselective β-blocker or endoscopic band ligation, or both, can be used. If primary prophylaxis with a β-blocker at an appropriate dose fails, the β-blocker therapy should not be continued alone and endoscopic band ligation should be performed. If the β-blocker dose is not found to be appropriate, either changing it to an optimal dose or performing endoscopic band ligation is possible. If endoscopic band ligation fails as primary prophylaxis, TIPS is the next option. Liver transplantation should be considered in all cases, particularly in patients with severe cirrhosis (Child–Pugh class B or C).

Box 3.

Ascites and its complications

Ascites occurs in cases of advanced cirrhosis and severe portal hypertension. The ultimate complications of ascites are refractory ascites, hepatorenal syndrome and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Uncomplicated ascites

All patients with ascites should undergo an evaluation of ascitic fluid content to rule out spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.134,135 The evaluation should include cell count, bacterial culture in blood culture medium, measurement of protein concentration and cytologic examination in cases of suspected malignant ascites.134,135 The use of leukocyte reagent strips has been recently proposed for the early detection of leukocytes in ascites and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.136–139

For subclinical ascites detectable only by ultrasonography, no specific treatment is necessary.135 However, a reduction in daily sodium intake (to 90 mmol/d) is recommended.

In cases of moderate ascites, renal function is usually preserved and treatment can be administered on an outpatient basis.134 Moderate dietary sodium restriction (90 mmol of sodium per day) should be imposed.135 Spironolactone, an anti-mineralocorticoid, is the drug of choice at the onset of treatment because it promotes better natriuresis more often than loop diuretics.140 It blocks the aldosterone-dependent exchange of sodium in the distal and collecting renal tubules, thus increasing the excretion of sodium and water.141 The initial dose is about 100–200 mg/d.134,135 About 75% of patients respond to treatment after only a few days.135 Side effects of spironolactone are gynecomastia, metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia and renal impairment.135 In the presence of edema, treatment with furosemide (20–40 mg/d) may be added for a few days to increase natriuresis.134,135 Loop diuretics act by increasing sodium excretion in the proximal tubules. In cirrhosis, the effect of loop diuretic monotherapy is limited and therefore is more commonly used as an adjunct to spironolactone therapy.135 The side effects of furosemide include hypokaliemia, metabolic hypochloremic alkalosis, hyponatremia, hypovolemia and related renal dysfunction.135 Amiloride (5–10 mg/d) may be used when spironolactone is contraindicated or if side effects such as gynecomastia occur.134,135 It also acts in the distal tubule.135 Diuretic therapy should be monitored by measuring the patient's weight and levels of serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine daily.135 Maximum weight loss should not exceed 500 g/d in patients without peripheral edema and 1000 g/d in those with it.135 If the therapeutic effect is insufficient, urinary sodium excretion should be determined to identify nonresponsive patients (characterized by a urinary sodium excretion below 30 mmol/d).135

Patients with severe ascites will have marked abdominal discomfort. In such cases, higher diuretic doses are needed (i.e., up to 400 mg of spironolactone and 160 mg of furosemide daily).134,135 However, in some patients, free-water excretion is impaired and severe hyponatremia may develop.134 Frequently, large-volume paracentesis should be done.135 Paracentesis should be routinely combined with plasma volume expansion. If the volume of ascites removed is less than 5 L, a synthetic plasma substitute may be used.135,142 If more than 5 L of ascitic fluid is removed, albumin should be given at a dose of 8 g per litre of fluid removed.135

Refractory ascites develops in about 10% of cases.143 In such cases, liver transplantation should be considered.55,135 In the meantime, therapeutic strategies can involve repeated large-volume paracentesis and plasma volume expansion with albumin or TIPS.55,134,135 TIPS improves renal function and sodium excretion60,144,145 and is more effective than paracentesis in removing ascites.61,63 TIPS has a mortality not significantly differerent from that associated with paracentesis.63 Nevertheless, a recent meta-analysis has reported a tendency toward improved survival with TIPS.61

Hepatorenal syndrome

Hepatorenal syndrome is the most serious circulatory renal dysfunction in cirrhosis21 and is the most severe complication of portal hypertension. It occurs in up to 10% of patients with ascites.146 The syndrome is defined by a serum creatinine concentration greater than 1.5 mg/dL (> 133 μmol/L).134 Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome involves the rapid impairment of renal function, characterized by a doubling of the initial serum creatinine concentration to more than 2.5 mg/dL (> 221 μmol/L) within 2 weeks.146 In type 2 hepatorenal syndrome, renal impairment is stable or progresses at a slower rate than that in type 1.146

The ideal treatment of hepatorenal syndrome is liver transplantation.55 Besides transplantation, vasoactive drug therapy in combination with albumin (20–40 g/d for 5–15 days) can be used.55,134 The efficiency of terlipressin (0.5–1 mg intravenously every 4–12 hours) has been reported in several uncontrolled trials.31–33 Therapy with norepinephrine (0.5–3.0 mg/h intravenously)147 or midodrine (7.5–12.5 mg orally 3 times daily) in association with octreotide (100–200 μg subcutaneously 3 times daily)148 has been suggested to improve hepatorenal syndrome, but its effectiveness remains to be confirmed. TIPS has been found to be effective in the management of hepatorenal syndrome by improving renal function, particularly in patients with a Child–Pugh score of 12 or less and a serum bilirubin level below 85 μmol/L.149

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, an infection of the ascitic fluid, occurs in 10%–30% of patients with ascites.73 All cases in which the neutrophil count is at least 250 × 106/L in ascitic fluid should be treated empirically, since ascites culture yields negative results in about 40% of patients with symptoms suggestive of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.55,73 Empirical treatment should also be started if leukocytes are detected in ascitic fluid at a significant level on reagent strips.136–139

Because most cases of peritonitis are due to gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli),134 therapy with a third-generation cephalosporin is the treatment of choice (cefotaxime 2–4 g/d, intravenously, for 5 days).55,73 Alternative treatments include combination therapy with amoxicillin and clavulinic acid (1 g and 0.125 g respectively, given intravenously or orally 3 times daily) or norfloxacin (400 mg/d, orally) for 7 days.55,73 Antibiotic therapy should be used in conjunction with albumin infusion (1.5 g/kg on day 1 and 1 g/kg on day 3)55 to prevent renal failure and death.150 Treatment efficacy should be assessed by means of evaluating clinical symptoms and determining the neutrophil count in ascitic fluid after 48 hours.55,73 If treatment fails, antibiotic therapy should be shifted toward a broader-spectrum drug or to one adapted to the organism's antibiogram.55,73

Primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with continuous oral norfloxacin therapy (400 mg/d) in hospital patients with cirrhosis who have a low ascitic protein concentration (< 10 g/L) is still debated.55,73 The same treatment is recommended for secondary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis until the ascites resolves, a treatment option that is more easily accepted by clinicians.55,73

Summary

Portal hypertension can lead to severe outcomes in patients with cirrhosis, including bleeding of esophagogastric varices and complications of ascites.

Variceal bleeding is a clinical emergency and requires blood volume replacement, early vasoactive drug therapy, prophylactic antibiotic treatment and endoscopic treatment. Prophylaxis of variceal bleeding involves the use of β-blocker therapy (first-line treatment in primary and secondary prophylaxis) and endoscopic treatment, especially band ligation (second-line step in primary and first-line step in secondary prophylaxis).

Treatment of ascites includes diuretic therapy and dietary sodium reduction. Main complications of ascites are refractory ascites, hepatorenal syndrome and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. In refractory ascites, repeated large-volume paracentesis (with volume expansion using albumin) and TIPS can be proposed. In hepatorenal syndrome, the most serious complication of ascites, liver transplantation should be considered; vasoactive drug therapy in combination with albumin infusion can be given in the meantime. All patients with ascites should be screened for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis; if detected, treatment consists of antibiotics and albumin infusion to prevent hepatorenal syndrome.

Acknowledgments

We thank Myriam Brian for her help with English-language revisions.

Appendix 1.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, the drafting of the article and the critical revision of it for important intellectual content. All gave final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared for Nina Dib, Frédéric Oberti. Paul Calès has received honoraria for clinical research from Debiovision, Montréal.

Correspondence to: Dr. Paul Calès, Centre hospitalier universitaire, 49933 Angers Cedex 09, France; fax (33) 2 41 35 41 19; paul.cales@univ-angers.fr

REFERENCES

- 1.Shibayama Y, Nakata K. Localization of increased hepatic vascular resistance in liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 1985;5:643-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Orrego H, Medline A, Blendis LM, et al. Collagenisation of the Disse space in alcoholic liver disease. Gut 1979;20:673-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Pinzani M, Gentilini P. Biology of hepatic stellate cells and their possible relevance in the pathogenesis of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:397-410. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Rockey DC, Weisiger RA. Endothelin induced contractility of stellate cells from normal and cirrhotic rat liver: implications for regulation of portal pressure and resistance. Hepatology 1996;24:233-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Wiest R, Groszmann RJ. The paradox of nitric oxide in cirrhosis and portal hypertension: too much, not enough. Hepatology 2002;35:478-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Abraldes JG, Angermayr B, Bosch J. The management of portal hypertension [review]. Clin Liver Dis 2005;9:685-713, vii. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Menon KV, Kamath PS. Regional and systemic hemodynamic disturbances in cirrhosis. [viii.]. Clin Liver Dis 2001;5:617-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bosch J, Mastai R, Kravetz D, et al. Hemodynamic evaluation of the patient with portal hypertension. Semin Liver Dis 1986;6:309-17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Garcia-Tsao G, Groszmann RJ, Fisher RL, et al. Portal pressure, presence of gastroesophageal varices and variceal bleeding. Hepatology 1985;5:419-24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Lebrec D, De Fleury P, Rueff B, et al. Portal hypertension, size of esophageal varices, and risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1980;79:1139-44. [PubMed]

- 11.Dell'era A, Bosch J. Review article: the relevance of portal pressure and other risk factors in acute gastro-oesophageal variceal bleeding [review]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;20(Suppl 3):8-15; discussion 16-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lee SS, Hadengue A, Moreau R, et al. Postprandial hemodynamic responses in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1988;8:647-51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.McCormick PA, Dick R, Graffeo M, et al. The effect of non-protein liquid meals on the hepatic venous pressure gradient in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1990;11:221-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Luca A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Bosch J, et al. Effects of ethanol consumption on hepatic hemodynamics in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1997;112:1284-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Garcia-Pagan JC, Feu F, Castells A, et al. Circadian variations of portal pressure and variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1994;19:595-601. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Garcia-Pagan JC, Santos C, Barbera JA, et al. Physical exercise increases portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Gastroenterology 1996;111:1300-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Luca A, Cirera I, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. Hemodynamic effects of acute changes in intra-abdominal pressure in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1993;104:222-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.De Ledinghen V, Heresbach D, Fourdan O, et al. Anti-inflammatory drugs and variceal bleeding: a case-control study. Gut 1999;44:270-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.De Ledinghen V, Mannant PR, Foucher J, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and variceal bleeding: a case-control study. J Hepatol 1996;24:570-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Thalheimer U, Triantos CK, Samonakis DN, et al. Infection, coagulation, and variceal bleeding in cirrhosis. Gut 2005;54:556-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Arroyo V, Colmenero J. Ascites and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis: pathophysiological basis of therapy and current management. J Hepatol 2003;38(Suppl 1):S69-89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.D'Amico G, De Franchis R. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology 2003;38:599-612. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.D'Amico G, Luca A. Natural history. Clinical-haemodynamic correlations. Prediction of the risk of bleeding. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol 1997;11:243-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.De Franchis R, Primignani M. Natural history of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2001;5:645-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.McCormick PA, O'Keefe C. Improving prognosis following a first variceal haemorrhage over four decades. Gut 2001;49:682-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Chiu KW, Sheen IS, Liaw YF. A controlled study of glypressin versus vasopressin in the control of bleeding from oesophageal varices. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1990;5:549-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Nevens F, Van Steenbergen W, Yap SH, et al. Assessment of variceal pressure by continuous non-invasive endoscopic registration: a placebo controlled evaluation of the effect of terlipressin and octreotide. Gut 1996;38:129-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Moreau R, Soubrane O, Hadengue A, et al. [Hemodynamic effects of the administration of terlipressin alone or combined with nitroglycerin in patients with cirrhosis]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1992;16:680-6. [PubMed]

- 29.Ioannou GN, Doust J, Rockey DC. Systematic review: terlipressin in acute oesophageal variceal haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:53-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30. Bosch J, Dell'era A. [Vasoactive drugs for the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004;28 Spec No 2:B186-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Moreau R, Durand F, Poynard T, et al. Terlipressin in patients with cirrhosis and type 1 hepatorenal syndrome: a retrospective multicenter study. Gastroenterology 2002;122:923-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Ortega R, Gines P, Uriz J, et al. Terlipressin therapy with and without albumin for patients with hepatorenal syndrome: results of a prospective, nonrandomized study. Hepatology 2002;36:941-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Uriz J, Gines P, Cardenas A, et al. Terlipressin plus albumin infusion: an effective and safe therapy of hepatorenal syndrome. J Hepatol 2000;33:43-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Feu F, Ruiz del Arbol L, Banares R, et al. Double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing terlipressin and somatostatin for acute variceal hemorrhage. Variceal Bleeding Study Group. Gastroenterology 1996;111:1291-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Bosch J, Kravetz D, Rodes J. Effects of somatostatin on hepatic and systemic hemodynamics in patients with cirrhosis of the liver: comparison with vasopressin. Gastroenterology 1981;80:518-25. [PubMed]

- 36.Cirera I, Feu F, Luca A, et al. Effects of bolus injections and continuous infusions of somatostatin and placebo in patients with cirrhosis: a double-blind hemodynamic investigation. Hepatology 1995;22:106-11. [PubMed]

- 37.Villanueva C, Ortiz J, Minana J, et al. Somatostatin treatment and risk stratification by continuous portal pressure monitoring during acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 2001;121:110-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Nevens F, Sprengers D, Fevery J. The effect of different doses of a bolus injection of somatostatin combined with a slow infusion on transmural oesophageal variceal pressure in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1994;20:27-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Avgerinos A, Nevens F, Raptis S, et al. Early administration of somatostatin and efficacy of sclerotherapy in acute oesophageal variceal bleeds: the European Acute Bleeding Oesophageal Variceal Episodes (ABOVE) randomised trial. Lancet 1997;350:1495-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Burroughs AK, McCormick PA, Hughes MD, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of somatostatin for variceal bleeding. Emergency control and prevention of early variceal rebleeding. Gastroenterology 1990;99:1388-95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Gotzsche PC, Gjorup I, Bonnen H, et al. Somatostatin v placebo in bleeding oesophageal varices: randomised trial and meta-analysis. BMJ 1995;310:1495-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Valenzuela JE, Schubert T, Fogel MR, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial of somatostatin in the management of acute hemorrhage from esophageal varices. Hepatology 1989;10:958-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Escorsell A, Bandi JC, Andreu V, et al. Desensitization to the effects of intravenous octreotide in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension. Gastroenterology 2001;120:161-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Zironi G, Rossi C, Siringo S, et al. Short-and long-term hemodynamic response to octreotide in portal hypertensive patients: a double-blind, controlled study. Liver 1996;16:225-34. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Ottesen LH, Flyvbjerg A, Jakobsen P, et al. The pharmacokinetics of octreotide in cirrhosis and in healthy man. J Hepatol 1997;26:1018-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Jenkins SA, Nott DM, Baxter JN. Pharmacokinetics of octreotide in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension; relationship between the plasma levels of the analogue and the magnitude and duration of the reduction in corrected wedged hepatic venous pressure. HPB Surg 1998;11:13-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Avgerinos A, Armonis A, Rekoumis G, et al. The effect of somatostatin and octreotide on intravascular oesophageal variceal pressure in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1995;22:379-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Moller S, Brinch K, Henriksen JH, et al. Effect of octreotide on systemic, central, and splanchnic haemodynamics in cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1997;26:1026-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Albillos A, Rossi I, Iborra J, et al. Octreotide prevents postprandial splanchnic hyperemia in patients with portal hypertension. J Hepatol 1994;21:88-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Besson I, Ingrand P, Person B, et al. Sclerotherapy with or without octreotide for acute variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 1995;333:555-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Sung JJ, Chung SC, Yung MY, et al. Prospective randomised study of effect of octreotide on rebleeding from oesophageal varices after endoscopic ligation. Lancet 1995;346:1666-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Zuberi BF, Baloch Q. Comparison of endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy alone and in combination with octreotide in controlling acute variceal hemorrhage and early rebleeding in patients with low-risk cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:768-71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Group IOVS, Burroughs AK. Double blind RCT of 5-day octreotide versus placebo, associated with sclerotherapy for trial/failures [abstract]. Hepatology 1996;24:352A.8690404

- 54.Calès P, Masliah C, Bernard B, et al. Early administration of vapreotide for variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. French Club for the Study of Portal Hypertension. N Engl J Med 2001;344:23-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Lebrec D, Vinel JP, Dupas JL. Complications of portal hypertension in adults: a French consensus. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;17:403-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Luketic VA. Management of portal hypertension after variceal hemorrhage [review]. Clin Liver Dis 2001;5:677-707, ix. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Waked I, Korula J. Analysis of long-term endoscopic surveillance during follow-up after variceal sclerotherapy from a 13-year experience. Am J Med 1997;102:192-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Westaby D, Macdougall BR, Williams R. Improved survival following injection sclerotherapy for esophageal varices: final analysis of a controlled trial. Hepatology 1985;5:827-30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Seewald S, Sriram PV, Naga M, et al. Cyanoacrylate glue in gastric variceal bleeding. Endoscopy 2002;34:926-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology 2005;41:386-400. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.D'Amico G, Luca A, Morabito A, et al. Uncovered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2005;129:1282-93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Henderson JM. Salvage therapies for refractory variceal hemorrhage. Clin Liver Dis 2001;5:709-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Saab S, Nieto JM, Ly D, et al. TIPS versus paracentesis for cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites [review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(3):CD004889. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, et al. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology 2004;126:469-75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.De Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension [published erratum in J Hepatol 2005;43(3):547]. J Hepatol 2005;43:167-76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Duggan JM. Review article: transfusion in gastrointestinal haemorrhage — If, when and how much? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1109-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.McCormick PA, Jenkins SA, McIntyre N, et al. Why portal hypertensive varices bleed and bleed: a hypothesis. Gut 1995;36:100-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Castaneda B, Debernardi-Venon W, Bandi JC, et al. The role of portal pressure in the severity of bleeding in portal hypertensive rats. Hepatology 2000;31:581-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Bleichner G, Boulanger R, Squara P, et al. Frequency of infections in cirrhotic patients presenting with acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Br J Surg 1986;73:724-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Goulis J, Armonis A, Patch D, et al. Bacterial infection is independently associated with failure to control bleeding in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Hepatology 1998;27:1207-12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Bernard B, Grange JD, Khac EN, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology 1999;29:1655-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Soares-Weiser K, Brezis M, Tur-Kaspa R, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis of bacterial infections in cirrhotic inpatients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand J Gastroenterol 2003;38:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 73.Rimola A, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol 2000;32:142-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Nevens F. Review article: a critical comparison of drug therapies in currently used therapeutic strategies for variceal haemorrhage [review]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20(Suppl 3):18-22; discussion 23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Bosch J, Abraldes JG, Groszmann R. Current management of portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2003;38(Suppl 1):S54-68. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Dib N, Konate A, Oberti F, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Application to the primary prevention of varices. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2005;29:957-87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Calès P, Oberti F, Bernard-Chabert B, et al. Evaluation of Baveno recommendations for grading esophageal varices. J Hepatol 2003;39:657-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Garcia-Tsao G. Current management of the complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension: variceal hemorrhage, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology 2001;120:726-48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Hillon P, Lebrec D, Munoz C, et al. Comparison of the effects of a cardioselective and a nonselective beta-blocker on portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1982;2:528-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 80.Mills PR, Rae AP, Farah DA, et al. Comparison of three adrenoreceptor blocking agents in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Gut 1984;25:73-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Groszmann RJ, Bosch J, Grace ND, et al. Hemodynamic events in a prospective randomized trial of propranolol versus placebo in the prevention of a first variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 1990;99:1401-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Lebrec D, Hillon P, Munoz C, et al. The effect of propranolol on portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis: a hemodynamic study. Hepatology 1982;2:523-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Garcia-Tsao G, Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, et al. Short-term effects of propranolol on portal venous pressure. Hepatology 1986;6:101-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Vorobioff J, Picabea E, Gamen M, et al. Propranolol compared with propranolol plus isosorbide dinitrate in portal-hypertensive patients: long-term hemodynamic and renal effects. Hepatology 1993;18:477-84. [PubMed]

- 85.Feu F, Bordas JM, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. Double-blind investigation of the effects of propranolol and placebo on the pressure of esophageal varices in patients with portal hypertension. Hepatology 1991;13:917-22. [PubMed]

- 86.Bosch J, Groszmann RJ. Measurement of azygos venous blood flow by a continuous thermal dilution technique: an index of blood flow through gastroesophageal collaterals in cirrhosis. Hepatology 1984;4:424-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Calès P, Braillon A, Jiron MI, et al. Superior portosystemic collateral circulation estimated by azygos blood flow in patients with cirrhosis. Lack of correlation with oesophageal varices and gastrointestinal bleeding. Effect of propranolol. J Hepatol 1985;1:37-46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 88.Bosch J, Masti R, Kravetz D, et al. Effects of propranolol on azygos venous blood flow and hepatic and systemic hemodynamics in cirrhosis. Hepatology 1984;4:1200-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Feu F, Bordas JM, Luca A, et al. Reduction of variceal pressure by propranolol: comparison of the effects on portal pressure and azygos blood flow in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1993;18:1082-9. [PubMed]

- 90.Bandi JC, Garcia-Pagan JC, Escorsell A, et al. Effects of propranolol on the hepatic hemodynamic response to physical exercise in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1998;28:677-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Perez-Paramo M, Munoz J, Albillos A, et al. Effect of propranolol on the factors promoting bacterial translocation in cirrhotic rats with ascites. Hepatology 2000;31:43-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 92.Bendtsen F, Simonsen L, Henriksen JH. Effect on hemodynamics of a liquid meal alone and in combination with propranolol in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1992;102:1017-23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Bellis L, Berzigotti A, Abraldes JG, et al. Low doses of isosorbide mononitrate attenuate the postprandial increase in portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2003;37:378-84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Vorobioff JD, Gamen M, Kravetz D, et al. Effects of long-term propranolol and octreotide on postprandial hemodynamics in cirrhosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2002;122:916-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 95.Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. Portal hypertension and variceal bleeding: an AASLD single topic symposium. Hepatology 1998;28:868-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 96.Feu F, Garcia-Pagan JC, Bosch J, et al. Relation between portal pressure response to pharmacotherapy and risk of recurrent variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Lancet 1995;346:1056-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Gluud C, Henriksen JH, Nielsen G. Prognostic indicators in alcoholic cirrhotic men. Hepatology 1988;8:222-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 98.Moitinho E, Escorsell A, Bandi JC, et al. Prognostic value of early measurements of portal pressure in acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 1999;117:626-31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 99.Vinel JP, Cassigneul J, Levade M, et al. Assessment of short-term prognosis after variceal bleeding in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis by early measurement of portohepatic gradient. Hepatology 1986;6:116-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Abraldes JG, Tarantino I, Turnes J, et al. Hemodynamic response to pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension and long-term prognosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology 2003;37:902-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.Huet PM, Pomier-Layrargues G. The hepatic venous pressure gradient: “remixed and revisited” [review]. Hepatology 2004;39:295-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 102.Navasa M, Chesta J, Bosch J, et al. Reduction of portal pressure by isosorbide-5-mononitrate in patients with cirrhosis. Effects on splanchnic and systemic hemodynamics and liver function. Gastroenterology 1989;96:1110-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Garcia-Pagan JC, Navasa M, Bosch J, et al. Enhancement of portal pressure reduction by the association of isosorbide-5-mononitrate to propranolol administration in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1990;11:230-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Calès P, Oberti F, Payen JL, et al. Lack of effect of propranolol in the prevention of large oesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized trial. French-Speaking Club for the Study of Portal Hypertension. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1999;11:741-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 105.Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Makuch RW, et al. Multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial of non-selective beta-blockers in the prevention of the complications of portal hypertension: final results and identification of a predictive factor. Hepatology 2003;38:206A.

- 106.Merkel C, Marin R, Angeli P, et al. A placebo-controlled clinical trial of nadolol in the prophylaxis of growth of small esophageal varices in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2004;127:476-84. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 107.Propranolol prevents first gastrointestinal bleeding in non-ascitic cirrhotic patients. Final report of a multicenter randomized trial. The Italian Multicenter Project for Propranolol in Prevention of Bleeding. J Hepatol 1989;9:75-83. [PubMed]

- 108.Conn HO. Propranolol-induced reduction in recurrent variceal hemorrhage in schistosomiasis. Hepatology 1990;11:1090-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 109.Lebrec D, Poynard T, Capron JP, et al. Nadolol for prophylaxis of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. A randomized trial. J Hepatol 1988;7:118-25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Pascal JP, Calès P. Propranolol in the prevention of first upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. N Engl J Med 1987;317:856-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 111.Talwalkar JA, Kamath PS. An evidence-based medicine approach to beta-blocker therapy in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Med 2004;116:759-66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 112.Bosch J, Garcia-Pagan JC. Complications of cirrhosis. I. Portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2000;32:141-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 113.Bosch J, Garcia-Pagan JC. Prevention of variceal rebleeding. Lancet 2003;361:952-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 114.Calès P, Grasset D, Ravaud A, et al. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic study of propranolol in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1989;27:763-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Calès P. Optimal use of propranolol in portal hypertension. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2005;29:207-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 116.Abraczinskas DR, Ookubo R, Grace ND, et al. Propranolol for the prevention of first esophageal variceal hemorrhage: A lifetime commitment? Hepatology 2001;34:1096-102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 117.Angelico M, Carli L, Piat C, et al. Effects of isosorbide-5-mononitrate compared with propranolol on first bleeding and long-term survival in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1997;113:1632-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 118.Garcia-Pagan JC, Villanueva C, Vila MC, et al. Isosorbide mononitrate in the prevention of first variceal bleed in patients who cannot receive beta-blockers. Gastroenterology 2001;121:908-14. [PubMed]

- 119.Burroughs AK, Jenkins WJ, Sherlock S, et al. Controlled trial of propranolol for the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1983;309:1539-42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 120.Colombo M, de Franchis R, Tommasini M, et al. Beta-blockade prevents recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding in well-compensated patients with alcoholic cirrhosis: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Hepatology 1989;9:433-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 121.Lebrec D, Poynard T, Bernuau J, et al. A randomized controlled study of propranolol for prevention of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: a final report. Hepatology 1984;4:355-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 122.Rossi V, Calès P, Burtin P, et al. Prevention of recurrent variceal bleeding in alcoholic cirrhotic patients: prospective controlled trial of propranolol and sclerotherapy. J Hepatol 1991;12:283-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 123.Gournay J, Masliah C, Martin T, et al. Isosorbide mononitrate and propranolol compared with propranolol alone for the prevention of variceal rebleeding. Hepatology 2000;31:1239-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 124. Thabut D. [Gastrointestinal hemorrhage. How to prevent rebleeding: role of pharmacological and endoscopic treatments]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004;28(Spec No 2):B73-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 125.D'Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. The treatment of portal hypertension: a meta-analytic review. Hepatology 1995;22:332-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 126.Heresbach D, Jacquelinet C, Nouel O, et al. [Sclerotherapy versus ligation in hemorrhage caused by rupture of esophageal varices. Direct meta-analysis of randomized trials]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1995;19:914-20. [PubMed]

- 127.Laine L, Cook D. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:280-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 128.Karsan HA, Morton SC, Shekelle PG, et al. Combination endoscopic band ligation and sclerotherapy compared with endoscopic band ligation alone for the secondary prophylaxis of esophageal variceal hemorrhage: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2005;50:399-406. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 129.Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, et al. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus nadolol and sucralfate compared with ligation alone for the prevention of variceal rebleeding: a prospective, randomized trial. Hepatology 2000;32:461-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 130.Ink O, Martin T, Poynard T, et al. Does elective sclerotherapy improve the efficacy of long-term propranolol for prevention of recurrent bleeding in patients with severe cirrhosis? A prospective multicenter, randomized trial. Hepatology 1992;16:912-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 131.O'Connor KW, Lehman G, Yune H, et al. Comparison of three nonsurgical treatments for bleeding esophageal varices. Gastroenterology 1989;96:899-906. [PubMed]

- 132.Luca A, D'Amico G, La Galla R, et al. TIPS for prevention of recurrent bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Radiology 1999;212:411-21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 133.Spina GP, Henderson JM, Rikkers LF, et al. Distal spleno-renal shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. A meta-analysis of 4 randomized clinical trials. J Hepatol 1992;16:338-45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 134.Gines P, Cardenas A, Arroyo V, et al. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Engl J Med 2004;350:1646-54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 135.Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, et al. The management of ascites in cirrhosis: report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology 2003;38: 258-66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 136.Castellote J, Lopez C, Gornals J, et al. Rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis by use of reagent strips. Hepatology 2003;37:893-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 137.Sapey T, Mena E, Fort E, et al. Rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with leukocyte esterase reagent strips in a European and in an American center. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;20:187-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 138.Thevenot T, Cadranel JF, Nguyen-Khac E, et al. Diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients by use of two reagent strips. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16:579-83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 139.Vanbiervliet G, Rakotoarisoa C, Filippi J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid urine-screening test (Multistix8SG) in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002;14:1257-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 140.Perez-Ayuso RM, Arroyo V, Planas R, et al. Randomized comparative study of efficacy of furosemide versus spironolactone in nonazotemic cirrhosis with ascites. Relationship between the diuretic response and the activity of the renin-aldosterone system. Gastroenterology 1983;84:961-8. [PubMed]

- 141.Wilkinson SP, Jowett TP, Slater JD, et al. Renal sodium retention in cirrhosis: relation to aldosterone and nephron site. Clin Sci (Lond) 1979;56:169-77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 142.Peltekian KM, Wong F, Liu PP, et al. Cardiovascular, renal, and neurohumoral responses to single large-volume paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and diuretic-resistant ascites. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:394-9. [PubMed]

- 143.Suzuki H, Stanley AJ. Current management and novel therapeutic strategies for refractory ascites and hepatorenal syndrome. QJM 2001;94:293-300. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 144.Wong F, Sniderman K, Liu P, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt: effects on hemodynamics and sodium homeostasis in cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:816-22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 145.Wong F, Sniderman K, Liu P, et al. The mechanism of the initial natriuresis after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Gastroenterology 1997;112:899-907. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 146.Arroyo V, Gines P, Gerbes AL, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of refractory ascites and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. International Ascites Club. Hepatology 1996;23:164-76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 147.Duvoux C, Zanditenas D, Hezode C, et al. Effects of noradrenalin and albumin in patients with type I hepatorenal syndrome: a pilot study. Hepatology 2002;36:374-80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 148.Angeli P, Volpin R, Gerunda G, et al. Reversal of type 1 hepatorenal syndrome with the administration of midodrine and octreotide. Hepatology 1999;29:1690-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 149.Brensing KA, Textor J, Perz J, et al. Long term outcome after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in non-transplant cirrhotics with hepatorenal syndrome: a phase II study. Gut 2000;47:288-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 150.Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med 1999;341:403-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 151.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, et al. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 152.D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217-31. [DOI] [PubMed]