Abstract

Drosophila CREB-binding protein (dCBP) is a very large multidomain protein, which belongs to the CBP/p300 family of proteins that were first identified by their ability to bind the CREB transcription factor and the adenoviral protein E1. Since then CBP has been shown to bind to >100 additional proteins and functions in a multitude of different developmental contexts. Among other activities, CBP is known to influence development by remodeling chromatin, by serving as a transcriptional coactivator, and by interacting with terminal members of several signaling transduction cascades. Reductions in CBP activity are the underlying cause of Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, which is, in part, characterized by several eye defects, including strabismus, cataracts, juvenile glaucoma, and coloboma of the eyelid, iris, and lens. Development of the Drosophila melanogaster compound eye is also inhibited in flies that are mutant for CBP. However, the vast array of putative protein interactions and the wide-ranging roles played by CBP within a single tissue such as the retina can often complicate the analysis of CBP loss-of-function mutants. Through a series of genetic screens we have identified several genes that could either serve as downstream transcriptional targets or encode for potential CBP-binding partners and whose association with eye development has hitherto been unknown. The identification of these new components may provide new insight into the roles that CBP plays in retinal development. Of particular interest is the identification that the CREB transcription factor appears to function with CBP at multiple stages of retinal development.

THE near-perfect structure of the Drosophila melanogaster compound eye is a striking example of how tight patterns of gene expression, morphogenetic movements, and cell fate choices can be regulated (Dickson and Hafen 1993; Wolff and Ready 1993; Voas and Rebay 2004). The adult retina consists of ∼800 identical unit eyes or ommatidia that are packed into a hexagonal array so precise that it is often referred to as a “neurocrystalline lattice” (Ready et al. 1976). Underlying this apparent seamless architecture is the internal organization of the ommatidia. The eight photoreceptors and 12 accessory cells occupy selfsame and stereotyped positions within each unit eye (Tomlinson and Ready 1987b; Cagan and Ready 1989; Ready 1989). While the positioning of the photoreceptors and accessory cells occurs relatively late in the development of the retina, the exactness of this process is reflected in the developmental history and gene expression profile of each specific cell type (Dickson and Hafen 1993; Wolff and Ready 1993). The R8 photoreceptor is the first cell to be specified, closely tailed by the addition of the R2/5, R3/4, and R1/6 pairs and finally followed by the R7 neuron (Tomlinson and Ready 1987a,b). The cone and pigment accessory cells are then sequentially added to the growing ommatidium (Cagan and Ready 1989). Each cell within an ommatidium expresses a unique combination of transcription factors and receives temporally and spatially regulated instructions (Dickson and Hafen 1993; Kumar and Moses 1997; Voas and Rebay 2004). For example, the R8 photoreceptor expresses the helix-loop-helix transcription factor atonal and is dependent upon the Notch signaling cascade (Jarman et al. 1994, 1995; Baker et al. 1996; Dokucu et al. 1996). In contrast, the neighboring R2/5 pair of photoreceptors requires the homeodomain transcription factor rough and signals from the EGF receptor pathway (Tomlinson et al. 1988; Kimmel et al. 1990; Freeman 1996; Kumar et al. 1998). How each cell interprets and integrates the different instructions with the repertoire of available transcription factors is still a largely undefined paradigm.

A growing body of evidence supports a pivotal role for large transcriptional complexes consisting of basal transcription components, specific DNA-binding proteins, and transcriptional coactivators and corepressors in coordinating spatial and temporal gene expression patterns (Mannervik et al. 1999). During development cells destined to adopt distinct cellular fates are often confronted with dynamic combinations of instructions from signaling cascades (Voas and Rebay 2004). The assembly of a large multifaceted transcriptional complex is thought to enhance the reception and execution of these “personalized” instructions. A great deal of data on the function of sequence-specific activators and repressors in retinal development in both insects and vertebrates has accumulated. However, significantly less is known about the roles played by transcriptional coactivators and corepressors. One such coactivator that functions in retinal development within both systems is CREB-binding protein (CBP) (van Genderen et al. 2000; Kumar et al. 2004).

CBP is a member of the CBP/p300 family of proteins (Goodman and Smolik 2000). CBP was first identified by a physical interaction with the CREB transcription factor while p300 was isolated on the basis of its ability to bind the adenoviral protein E1 (Chrivia et al. 1993; Kwok et al. 1994; Nordheim 1994). Since then CBP is known to physically interact with >100 proteins, including members of the basal transcriptional machinery, sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins, nuclear hormone receptors, and terminal members of several signaling transduction cascades (Arany et al. 1994; Kwok et al. 1994; Kee et al. 1996; Gu et al. 1997; Chan and La Thangue 2001; McManus and Hendzel 2001). In addition, CBP is known to bind to acetylated histones during phases of chromatin remodeling and contains several putative zinc-finger motifs that can be used for either direct DNA binding or protein-protein interactions (Bannister and Kouzarides 1996; Chakravarti et al. 1996; Akimaru et al. 1997a; Avantaggiati et al. 1997; Martinez-Balbas et al. 1998; Goodman and Smolik 2000; Deng et al. 2003). Thus, CBP has the potential to influence development through a variety of molecular and biochemical means, some separated in time and space, others executed simultaneously (Goldman et al. 1997; Shi and Mello 1998; Goodman and Smolik 2000; Chan and La Thangue 2001; Janknecht 2002).

Mutational studies of CBP in Drosophila, mice, and human patients confirm a wide-ranging role for CBP in early development. For example, mutations within the human homolog of CBP are the underlying cause of Rubinstein-Taybi Syndrome, an affliction characterized by severe facial abnormalities, broad thumbs, broad big toes, mental retardation, and incorrect retinal development (Petrij et al. 1995; Tanaka et al. 1997; Oike et al. 1999; Murata et al. 2001; Coupry et al. 2002; Kalkhoven et al. 2003). Strabismus, juvenile glaucoma, cataracts, and coloboma of the eyelid, lens, and iris are among the eye defects associated with this syndrome (Roy et al. 1968; Levy 1976; Ramakrishnan et al. 1990; Silengo et al. 1990; Guion-Almeida and Richieri-Costa 1992; van Genderen et al. 2000). Similarly, reductions in CBP activity have pleiotropic effects within a wide range of Drosophila tissues. For instance, during embryogenesis CBP is known to play a part in patterning several head and trunk segments, the midgut, and the dorsal ectoderm (Akimaru et al. 1997b; Florence and McGinnis 1998; Waltzer and Bienz 1998, 1999; Petruk et al. 2001; Takaesu et al. 2002; Lilja et al. 2003). In addition, CBP functions during late larval and pupal stages to promote dendritic and axonal morphogenesis, synapse formation, and the release of transmitters at the neuromuscular junction (Bantignies et al. 2000; Marek et al. 2000). During these same stages CBP also plays a role in patterning by regulating the formation of the wing veins (Akimaru et al. 1997a). Furthermore, previous studies have shown that CBP is required for the proper specification and patterning of the fly retina while overexpression of CBP in adult photoreceptors can induce a light-independent form of retinal degeneration (Ludlam et al. 2002; Taylor et al. 2003; Kumar et al. 2004).

While there is an obvious wealth of opportunities to study the role that CBP plays in both insect and mammalian development, the sheer number of potential means by which CBP influences development can complicate interpretations of loss-of-function phenotypes. In other words, it is not entirely clear what effect each of the >100 different physical interactions assigned to CBP has on the development of the fruit fly, the mouse, or humans. Nor is the primary defect in any one particular tissue, including the eye, always clear from an analysis of loss-of-function mutants. To begin to get a better understanding of how CBP influences retinal development, we have carried out a series of genetic screens in the fly eye to isolate putative binding partners and transcriptional targets. The series of screens described in this report have revealed interactions that are not readily found in other classical screens. Additionally, these assays have enabled us to gain an understanding of how the interacting genes are integrated into the modular function of CBP.

Our screens indicate that during eye development CBP interacts with (1) members of the retinal determination cascade to specify the eye and with (2) signaling pathways to regulate cell fate choices. Of particular significance is the observation that the CREB transcription factor and members of the EGF receptor signaling cascade interact with CBP during eye development. These genetic and developmental interactions are supported by biochemical evidence that places both CREB and CBP directly downstream of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling (Frodin and Gammeltoft 1999). In this article we further demonstrate that CREB is expressed in the developing eye and plays a role in both eye specification and photoreceptor cell fate decisions. Such interactions may provide further insight into the mechanisms underlying the observed phenotypes in the retinas of CBP loss-of-function mutants in both flies and mammals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks:

The following fly alleles and insertions were obtained for the experiments described here: GMR-CBP FL, GMR-CBP ΔNZK, GMR-CBP ΔBHQ, GMR-CBP ΔQ, GMR-DIAPI, GMR-DIAPII, Df(3)H99 (Joseph Duffy), so3 (Larry Zipursky), eyaD1 (Nancy Bonini), dac4 (Graeme Mardon), ey-GAL4 (Walter Gehring), GMR-GAL4 (Lucy Cherbas), UAS-CrebA, crebAB204 (Deborah Andrew), and sev-GAL4, ey-FLP, FRT80B, FRT80B Ubi-GFP, CrebA10183, and the Bloomington Stock Center Drosophila deficiency kit (Bloomington Stock Center).

Genetic screen:

We crossed the ∼235 stocks that constitute the Bloomington Stock Center Drosophila deficiency kit, which provides nearly 95% coverage of the genome, to GMR-CBP FL, GMR-CBP ΔNZK, GMR-CBP ΔBHQ, and GMR-CBP ΔQ flies and assayed the ability of each deficiency to modify the rough-eye phenotypes that result from the expression of each CBP protein variant. We mapped the suppressing and enhancing activities by crossing single-gene mutations (Bloomington Stock Center) uncovered by the larger deficiencies and scored the ability of each single-gene mutation to mimic that of the overlying deficiency. All genetic interactions were confirmed by testing multiple mutant alleles of each identified complementation group.

Generation of retinal mosaic clones:

Loss-of-function CrebA alleles were recombined onto a third chromosome containing an FRT element at cytological position 80B. eyFLP; FRT80B CrebA[LOF]/+ males were crossed to either FRT80B Ubi-GFP or FRT80B P[w+] females to induce retinal clones that could be analyzed within either the eye imaginal disc or adult retinas, respectively. Clones were negatively marked and identified in the imaginal disc by the absence of a GFP reporter and in the adult by the absence of red pigment.

Antibodies and microscopy:

The following primary antibodies were used: rat ant-ELAV (1:100, gift of Gerald Rubin), rabbit anti-ATONAL (1:1000, gift of Andrew Jarman), mouse anti-DACHSHUND (1:100, gift of Graeme Mardon), mouse anti-EYES ABSENT (1:10, gift of Seymour Benzer), and rabbit anti-CREB (1:10, gift of Deborah Andrews). The following secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson Laboratories: goat anti-mouse FITC (1:100), goat anti-rabbit FITC, and goat anti-rat FITC (1:100). F-actin was visualized using phalloidin-rhodamine (1:500, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Imaginal discs were dissected and treated as described in Kumar et al. (1998) while adult retinas were prepared either for scanning electron microscopy or for sectioning as described in Kumar et al. (1998, 2003).

RESULTS

Expression of CBP variants inhibits eye development:

In a previous report that analyzed retinal phenotypes of nejire (nej) loss-of-function mutants, we showed that CBP influences eye specification by regulating and interacting with several members of the retinal determination cascade (Kumar et al. 2004). CBP was also shown to regulate the cell fate choices of photoreceptor neurons and accessory cone cells (Kumar et al. 2004). We further demonstrated, through the use of a series of truncated proteins, that the activity of CBP within the developing retina is modular (Kumar et al. 2004). Since CBP is a large multidomain protein with a myriad of known binding partners, we were interested in furthering our understanding of the genetic, molecular, and biochemical mechanisms by which CBP influences cell fate choices in the fly retina. Here we report the results of several genetic screens designed to identify putative CBP-binding partners and transcriptional targets in the developing eye of Drosophila.

The GMR-GAL4 and sev-GAL4 drivers were used to drive expression of wild-type (UAS-CBP FL) and several mutant versions of CBP (UAS-CBP ΔNZK, UAS-CBP ΔBHQ, or UAS-CBP ΔQ transgenes) in the developing eye (Figures 1 and 2; Kumar et al. 2004). The GMR enhancer element (which is under the control of the GLASS transcription factor) directs expression to all cells posterior to the advancing morphogenetic furrow while the sev enhancer element restricts expression to just a subset of cells within each assembling unit eye (Basler et al. 1989; Bowtell et al. 1989; Moses et al. 1989; Moses and Rubin 1991; Hay et al. 1995). The expression of the full-length and truncated CBP proteins results in unique disruptions of the compound eye, which can be easily scored in a scan of the external surface (Figure 2, A, C, E, and G; Kumar et al. 2004). These truncated proteins are expected to function as “protein sinks” by soaking up varying combinations of site-specific DNA-binding proteins as well as signaling pathway components. Since each CBP truncated protein retains a unique set of protein domains, the expression of each variant protein is expected to yield a different phenotype. This is observed in surface views of the compound eye (Figure 2, A, C, E, and G; Kumar et al. 2004) as well as in retinal sections of developing and adult retinas (Figure 2, B, D, F, and H; Kumar et al. 2004).

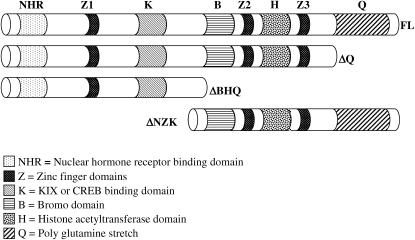

Figure 1.

Schematic of CBP deletion proteins. Wild-type (CBP FL) and three mutant variants of CBP (CBP ΔNZK, CBP ΔBHQ, and CBP ΔQ) are diagrammed with protein domains included. The CBP ΔQ variant lacks the C-terminal poly-glutamine-rich region of the protein. The CBP ΔBHQ variant is lacking the BROMO domain, the HAT domain, the poly-glutamine-rich domain and the second and third zinc-finger DNA-binding domains. The CBP ΔNZK variant deletes the N-terminal half of the protein that includes the domain for binding to nuclear hormone receptors and the KIX domain, which binds the CREB transcription factor.

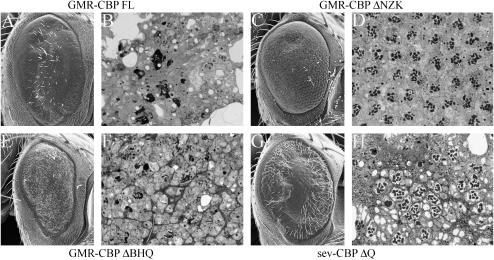

Figure 2.

Expression of CBP variant proteins alter the structure of the adult eye. (A, C, E, and G) Scanning electron micrographs of the external surface of adult eyes. (B, D, F, and H) Light microscope sections of adult retinas. (A and B) GMR-GAL4/UAS-CBP FL. Note that the surface is relatively flat with few scattered bristles. The retina has undergone severe retinal degeneration. (C and D) GMR-GAL4/UAS-CBP ΔNZK. Note that the major defect on the external surface is the absence of interommatidial bristles. Also, each ommatidium appears to have one to two extra photoreceptors. (E and F) GMR-GAL4/UAS-CBP ΔBHQ. Note the severe roughening of the adult eye and the presence of nonommatidial bristles. The photoreceptors have also undergone high levels of retinal degeneration. (G and H) sev-GAL4/UAS-CBP ΔQ. Note the loss of ommatidia within the middle of the retina. The remaining ommatidia lack variable numbers of photoreceptors. Anterior is to the right.

The phenotypes that resulted from the expression of truncated CBP proteins provided considerable insight into the roles played by CBP in cell fate specification. For instance, expression of the CBP ΔNZK protein results in the recruitment of one to two extra photoreceptor cells per ommatidium (Figure 2, C and D; Kumar et al. 2004). Within the developing eye disc, these extra photoreceptors appear to occupy the positions of the so-called mystery cells, which normally join the developing unit eye but are then removed during ommatidial assembly (Tomlinson and Ready 1987a,b; Kumar et al. 2004). One possible explanation is that CBP ΔNZK has bound and sequestered one or several factors that are normally required to block the mystery cells from acquiring a neuronal fate and joining the developing ommatidium. Another striking example is the switch in cell fate that accompanies expression of the CBP ΔBHQ. Each ommatidium has a lower-than-normal number of photoreceptors while at the same time maintaining a higher-than-expected number of nonneuronal cone and pigment cells (Figure 2, E and F; Kumar et al. 2004). One possible scenario is that the CBP ΔBHQ might bind and sequester one or several factors that are involved in the decision to become a photoreceptor, thus promoting the default nonneuronal accessory cell fate instead. In the final case, a block in R3/4 recruitment accompanies expression of the CBP ΔQ protein (Figure 2, G and H; Kumar et al. 2004). In these retinas, it is likely that the CBP ΔQ protein is bound to one or more transcription factors that are required to select the R3/4 cell fate. The genetic screens that are reported here were designed to identify the factors that cooperate with CBP to regulate each of these cell fate decisions within the developing ommatidium.

Reductions in the gene dosage of at least 35 complementation groups modify the retinal phenotypes of CBP expression in the developing eye:

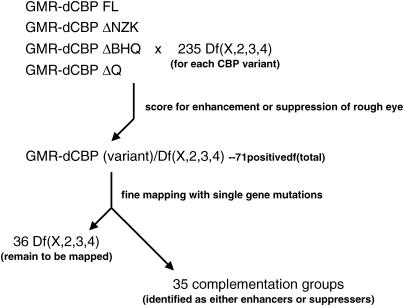

We initiated four genetic screens in which we were looking for modifications (either suppression or enhancement) of the rough-eye phenotypes described in Figure 2 by reducing the dosage of putative interacting genes (Figure 3). We made use of the Bloomington Stock Center deficiency kit that provides nearly 95% coverage of the Drosophila genome. Since each fly strain contains a unique chromosomal deletion, we were able to fairly rapidly determine which regions of the genome were harboring putative interacting genes. In this initial screen 71 deletions were scored as positives in our assays (Figure 3). We then narrowed the genomic intervals by testing the ability of smaller deficiencies (whose breakpoints are within the initial deletion) to mimic the effects of the overlying large deletions. We then mapped the suppressing and enhancing activities by scoring the ability of single-gene disruptions to mimic that of the overlying deletion. Using this approach we were then able to identify 35 complementation groups that encode for putative binding partners and transcriptional targets (Figure 3, Table 1). In all cases we confirmed these suppressing and enhancing activities by testing multiple alleles of each complementation group.

Figure 3.

Genetic screen for modifiers of the CBP variant rough-eye phenotype. Flies expressing either wild-type CBP or the three protein variants were crossed to the ∼235 stocks that constitute the Bloomington Stock Center deficiency kit and the F1 progeny were screened for modifications of the rough-eye phenotypes depicted in Figure 2. From this initial screen 71 deletions were selected for further genetic mapping. Single-gene mutations were then screened and 35 complementation groups were identified as being responsible for the modification of the rough-eye phenotypes of the starting materials. The complementation groups of 36 regions of the genome remain unidentified.

TABLE 1.

Mutants that suppress the overexpression of CBP proteins

| GMR-CBP FL

|

GMR-CBP ΔNZK

|

GMR-CBP ΔBHQ

|

GMR-CBP ΔQ

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| En | Su | En | Su | En | Su | En | Su |

| — | — | kni | gl | ade2 | Tpl | Scr | CG1707 |

| rho | ll | lilli | Ubx | Tsp42E | |||

| 1(4)102CD | luc | sog | RhoGAP93B | ||||

| dpp | CrebA | cgd | |||||

| CG17836 | gl | srp | |||||

| cgd | 1(3)L3659 | ||||||

| Ubx | sty | ||||||

| rho | enc | ||||||

| kni | 1(3)72Df(3) | ||||||

| Egfr | 1(3)71DEc[E86] | ||||||

| Kr | rn | ||||||

| spi | ey | ||||||

The genetic screen for modifiers of the GMR-CBP FL and GMR-CBP ΔNZK yielded the fewest interacting genes while the screens for modifiers of GMR-CBP ΔBHQ and GMR-CBP ΔQ yielded the most interacting genes. Mutants that modified more than one construct are underlined. En, enhancer; Su, supperssor.

We were unable to identify individual complementation groups in the remaining 36 cases (Figure 3, Table 2). A significantly large number of genes that are predicted to lie within these intervals are not disrupted by existing mutations and therefore we could not test all potential candidates. Another possible explanation is that the modifying activity is due to the simultaneous removal of two or more genes within any one given region. As gene disruption projects continue to produce newly induced loss-of-function mutants it will become interesting to determine the identity of these remaining 36 putative interacting loci.

TABLE 2.

Deficiency stocks that suppress the overexpression of CBP proteins

| GMR-CBP FL

|

GMR-CBP ΔNZK

|

GMR-CBP ΔBHQ

|

GMR-CBP ΔQ

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytological location | Phenotype | Cytological location | Phenotype | Cytological location | Phenotype | Cytological location | Phenotype |

| 31C1-32E1 | Enhancer | 3D6-4F5 | Enhancer | 42E1-44D8 | Enhancer | ||

| 60F1-60F5 | Enhancer | 7B2-7C1 | Enhancer | 63F6-64C15 | Enhancer | ||

| None found | 64C1-65C1 | Enhancer | 10A7-10F7 | Enhancer | 88F9-89B9 | Enhancer | |

| 76B4-77B1 | Enhancer | 13F1-14C1 | Enhancer | 95D7-95F17 | Enhancer | ||

| 96B6-96D2 | Enhancer | 15D3-16A6 | Enhancer | 96F1-97B1 | Enhancer | ||

| 30D1-31F1 | Enhancer | ||||||

| 48E12-50D7 | Enhancer | ||||||

| 96F1-97B1 | Enhancer | ||||||

| 99A1-99B6 | Enhancer | ||||||

| 53E1-53F11 | Suppressor | 5C3-6C12 | Suppressor | 5C3-6C12 | Suppressor | ||

| 76B4-77B1 | Suppressor | 23C1-23E2 | Suppressor | 22D2-22F2 | Suppressor | ||

| 60A3-60B7 | Suppressor | 23C1-23C5 | Suppressor | ||||

| None found | 63C2-63F7 | Suppressor | 23E5-23F5 | Suppressor | |||

| 65D4-65E6 | Suppressor | 28A4-28D9 | Suppressor | ||||

| 71F1-72D10 | Suppressor | 30C3-30F1 | Suppressor | ||||

| 76B6-77A1 | Suppressor | 54F2-56A1 | Suppressor | ||||

| 76B4-77B1 | Suppressor | ||||||

We were unable to refine the genetic maps for several genomic regions. This may be due to the lack of available mutations for all predicted genes or the modifying activity may be the product of simultaneously removing two or more genes. Note that stocks carrying deletions of the 76B4-77B1 interval enhance the rough-eye phenotype of GMR-CBP ΔNZK but suppress the phenotype of GMR-CBP ΔBHQ and GMR-CBP ΔQ. Also note that deletions of the 5C3-6C12 region suppress both GMR-CBP ΔBHQ and GMR-CBP ΔQ. Additionally, deletions of the 96F1-97B1 interval enhance both GMR-CBP ΔBHQ and GMR-CBP ΔQ. These three regions are likely to harbor genes that interact or are regulated by specific domains of CBP. Deletions that modified more than one construct are underlined.

Modification of the GMR-CBP FL phenotype:

Of the four constructs, expression of the full-length CBP protein (CBP FL) yielded the strongest rough-eye phenotype. The external surface is flattened and contains a small scattering of interommatidial bristles while retinal sections reveal a retina that is largely composed of completely degenerated photoreceptors (Figure 2, A and B; Kumar et al. 2004). This phenotype likely results from the interaction of CBP with dozens of transcription factors, the chromatin-remodeling machinery, nuclear hormone receptors, and signaling pathway components. It is therefore not surprising that we identified fewer than a handful of deficiencies that could either suppress or enhance the eye phenotype (Table 2, Figure 4, I and J).

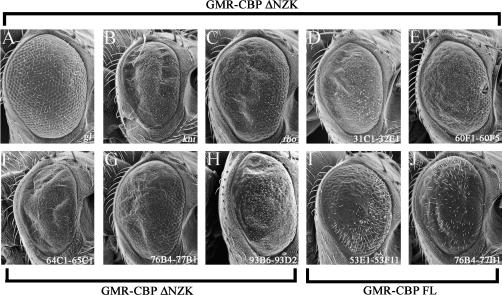

Figure 4.

Modifiers of CBP FL and CBP ΔNZK expression in the developing eye. (A–J) Scanning electron micrographs of adult eyes. (A–H) Modifiers of GMR-CBP ΔNZK. (I and J) Modifiers of GMR-CBP FL. All genotypes and genomic regions are listed above and within each panel. Anterior is to the right. An example of a suppressor of the GMR-CBP ΔNZK rough-eye phenotype is shown in A. Examples of enhancers of the GMR-CBP ΔNZK rough-eye phenotype are shown in B–H. Examples of suppressors of the GMR-CBP FL rough-eye phenotype are shown in I and J.

Modification of the GMR-CBP ΔNZK phenotype:

Expression of the CBP ΔNZK protein, which lacks the CREB-binding domain, inhibited the formation of the interommatidial bristles, a process that is thought to be influenced by the wingless signaling pathway (Cadigan and Nusse 1996). Most ommatidia contained extra photoreceptor cells, a phenotype also observed in argos mutations (Freeman et al. 1992). In addition, the rhabdomere, which is the light-capturing organelle of the cell, is malformed in nearly all photoreceptors (Figure 2, C and D; Kumar et al. 2004). As CBP is known to play a role in retinal degenerations (Ludlam et al. 2002; Taylor et al. 2003; Kumar et al. 2004), it is not surprising that proper rhabdomere formation is affected by the expression of CBP ΔNZK.

As a control we were able to suppress the rough-eye phenotype by removing one copy of the glass gene (Table 1, Figure 4A). However, no other single-gene disruptions were identified as suppressor mutants. All other observed modifications were enhancements of the rough eye (Tables 1 and 2; Figure 4, B–H). We were able to identify two complementation groups [rhomboid (rho) and knirps (kni)] as potential interacting genes (Figure 4, B and C). The rho locus encodes a serine protease, which is a critical member of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling cascade and has a long-standing role in eye development (Freeman et al. 1992; Lee et al. 2001; Urban et al. 2001, 2002). The kni locus, while important for the establishment of several wing veins, has not been known to play a role in eye development (Lunde et al. 1998, 2003; Martin-Blanco et al. 1999). It is possible that our sensitized genetic background has uncovered a new role for kni, this time in eye development.

We were unable to refine the genetic maps for the remaining five genomic regions listed in Table 2 and displayed in Figure 4, D–H. Interestingly, the region 76B4-77B1 was identified by deficiencies that enhanced the GMR-CBP ΔNZK phenotype. However, these same deficiencies were identified as suppressors of the rough-eye phenotypes of GMR-CBP FL, GMR-CBP ΔBHQ, and sev-CBP ΔQ expression (Figures 4J, 6B, and 8J). This observation suggests that there is at least one gene within this region that serves as a transcriptional target or encodes for a binding partner that is specific for the N-terminal half of the protein. Such domain-specific interactions are supported by the modular activity of CBP in the eye (Kumar et al. 2004).

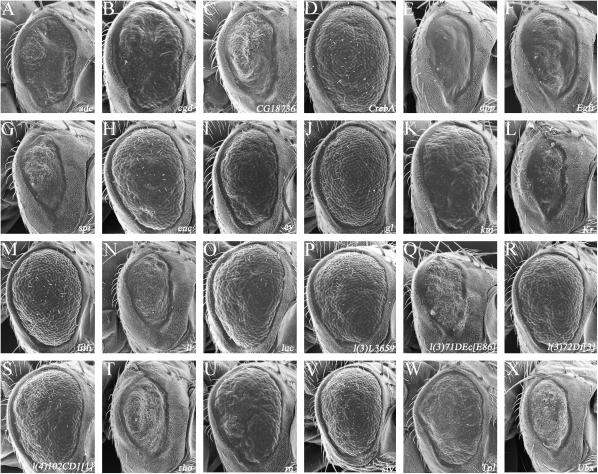

Figure 6.

Modifiers of CBP ΔBHQ expression in the developing eye. (A–X) Scanning electron micrographs of adult eyes. All genotypes and genomic regions are indicated. Anterior is to the right. Examples of enhancers of the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ rough-eye phenotype are shown in A, C–F, H, I, O, and P. Examples of suppressors of the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ rough-eye phenotype are shown in B, G, and J–N.

Figure 8.

Modifiers of CBP ΔQ expression in the developing eye. (A–X) Scanning electron micrographs of adult eyes. Genomic regions are indicated. Anterior is to the right. Examples of enhancers of the GMR-CBP ΔQ rough-eye phenotype are shown in G, I, K, L, and M. Examples of suppressors of the GMR-CBP ΔQ rough-eye phenotype are shown in A–F, H, and J.

Modification of the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ phenotype:

The adult eye that results from expression of the CBP ΔBHQ protein is sizably smaller than that of wild type and is covered with tiny bristles that are not consistent with the size or organization of wild-type interommadial bristles (Figure 2E; Kumar et al. 2004). Adult sections show a retina that appears to have clusters of photoreceptor cells. However, severe retinal degeneration has occurred and the rhabdomeres are completely absent (Figure 2F; Kumar et al. 2004). Despite the severe rough-eye phenotype, removing one copy of the glass gene was sufficient to suppress the phenotype (Table 1, Figure 5J). Screens designed to recover modifiers of the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ phenotype by far yielded the largest number of putative interacting genes (Table 1, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Modifiers of CBP ΔBHQ expression in the developing eye. (A–X) Scanning electron micrographs of adult eyes. All genotypes are listed within each image. Anterior is to the right. Examples of enhancers of the CBP ΔBHQ rough-eye phenotype are shown in A–C, E–G, K, L, N, S, T, and X. Examples of suppressors of the CBP ΔBHQ rough-eye phenotype are shown in D, H–J, M, O–R, U, and V.

One interesting finding is a potential interaction between CBP and the EGFR signaling cascade. Dosage reductions in the genes that encode for the receptor (EGFR), a positively acting ligand, spitz (spi; Rutledge et al. 1992) and rho, a serine protease that processes the ligand (Lee et al. 2001; Urban et al. 2001, 2002), lead to a strong enhancement of the rough-eye phenotype (Figure 5, F, G, and T). In contrast, reductions in sprouty (spry; Kramer et al. 1999) and liliputian (lilli; Wittwer et al. 2001), two EGFR signaling antagonists, suppresses the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ rough-eye phenotype (Figure 5, M and V). Taken together, these results suggest that CBP functions within the EGFR signaling cascade. Supporting this assertion is biochemical evidence that indicates that the CBP-CREB complex is phosphorylated by RSK, a known component of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling cascades (Frodin and Gammeltoft 1999).

Several other genes such as decapentaplegic (dpp), eyeless (ey), lanceolate (ll), and rotund (rn) were identified in our screen on the basis of the modification of the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ eye phenotype (Figure 5, E, I, N, and U) and are already known to play roles in eye specification, morphogenetic furrow initiation, and photoreceptor cell fate determination (Heberlein and Moses 1995; Treisman and Heberlein 1998; Abrell et al. 2000; Bergeret et al. 2001; Kumar 2001; Kumar and Moses 2001). In the case of dpp, our results are supported by prior demonstrations that CBP regulates dpp expression in the amnioserosa of the blastoderm embryo, the midgut, the posterior tracheal branches, and the wing veins (Waltzer and Bienz 1999; Takaesu et al. 2002; Lilja et al. 2003). These results suggest a central role for CBP in coordinating the activities of several signaling cascades and transcription factors during eye development.

We have also identified genes whose roles in nonretinal tissues are well documented but whose function in eye development remains unknown (Figure 5, A, B, D, H, K, O, W, and X). For example, the CrebA, luckenhaft, encore, and congested genes are known to function in many developmental contexts within the embryonic and larval stages but hitherto have not been associated with retinal development (Eberl and Hilliker 1988; Schüpbach and Wieschaus 1989; Hawkins et al. 1996; Andrew et al. 1997; Rose et al. 1997; Van Buskirk et al. 2000). However, loss-of-function mutations for each of these genes were sufficient to modify the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ retinal phenotype (Figure 5, B, D, H, and O). Our results suggest that these genes may play additional roles in eye development through interactions with nejire.

Several mutants, which were identified in earlier screens for embryonic lethal mutations, were also identified as potential targets or binding partners of CBP in the eye (Figure 5, C, P, Q, R, and S). Unfortunately, very little, if any, developmental or molecular information surrounds these mutations. And finally, we have identified several regions of the genome that are likely to harbor additional genes that interact with nejire (Table 2, Figure 6). Again, due to the lack of mutations in all predicted genes within these regions, we were unable to refine the genetic maps to individual complementation groups. However, on the basis of the strength of their suppressing and enhancing activities we are confident that the underlying genes play an important role in eye development. It should be noted that deletions of the 96F1-97B1 interval enhance the rough-eye phenotype of both GMR-CBP ΔBHQ and GMR-CBP ΔQ. Likewise, deletions of the 5C3-6C12 interval suppress the rough eyes of both fly stocks. These results suggest that the N-terminal half of CBP likely interacts with factors encoded by genes that reside within these cytological locations.

Modification of the CBP ΔQ phenotype:

We attempted to identify new interacting genes through a screen that isolated modifiers of CBP ΔQ expression (Figure 1). While expression of CBP ΔQ under the GMR enhancer element leads to a block in the addition of the R3/4 photoreceptor pair during ommatidial assembly, the animals die during the midpupal phase, and thus a genetic screen for modifications of this phenotype is not feasible (Kumar et al. 2004). However, flies that express CBP ΔQ under the control of the sev enhancer element, which directs expression within a subset of developing photoreceptors (Basler et al. 1989; Bowtell et al. 1989), are viable and have severely roughened adult eyes (Figure 2G). An examination of adult retinal sections indicates that there is a drastic reduction in the number of ommatidia, loss of photoreceptor neurons, aberrant rhabdomere formation, and retinal degenerations (Figure 2H). As expected, this milder phenotype was conducive to the recovery of several modifiers (Tables 1 and 2) of which we were able to identify eight complementation groups (Figure 7).

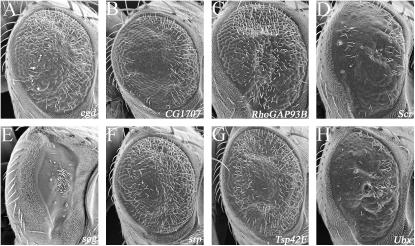

Figure 7.

Modifiers of CBP ΔQ expression in the developing eye. (A–X) Scanning electron micrographs of adult eyes. All genotypes are listed indicated. Anterior is to the right. Examples of enhancers of the GMR-CBP ΔQ rough-eye phenotype are shown in D, E, and H. Examples of suppressors of the GMR-CBP ΔQ are shown in A–C, F, and G.

Interestingly, removal of one copy of short gastrulation (sog), which functions to maintain a high Dpp gradient in several tissues including the D/V axis of early embryos (Francois et al. 1994; Biehs et al. 1996; Yu et al. 1996; Decotto and Ferguson 2001), enhanced the rough-eye phenotype of sev-CBP ΔQ (Figure 7E). This is consistent with the above results in which reductions of dpp also enhanced the retinal phenotype of GMR-CBP ΔBHQ (Figure 5E). Thus the results from both screens suggest that the Dpp pathway may converge with CBP to regulate various aspects of eye development (Figure 5E). This is supported by evidence that in several embryonic tissues CBP interacts with MAD protein to induce the expression of downstream transcriptional targets of the Dpp signaling pathway (Waltzer and Bienz 1999).

As with the other genetic screens described above, this screen identified genes whose role in nonretinal tissues is well established but hitherto not known to function during eye development. For example, congested (cgd), Sex combs reduced (Scr), serpent (srp), and Ultrabithorax (Ubx) function to properly segment the embryonic head and trunk, secrete the embryonic/larval cuticle, and specify the crystal cells (Akam et al. 1985; Eberl and Hilliker 1988; Reuter 1994; Percival-Smith et al. 1997; Fossett et al. 2003; Waltzer et al. 2003). Reductions in the gene dosage of each of these genes modified the sev-CBP ΔQ rough-eye phenotype, suggesting new roles for each of these genes in retinal development (Figure 7, A, D, F, and H). The CG1707, rhoGAP93B, and Tsp42Ea complementation groups are interesting because they appear to interact with CBP and because a role in eye development would be the first major role ascribed to these genes (Figure 7, B, C, and G). Additionally, we potentially have another 13 complementation groups yet to be identified (Figure 8).

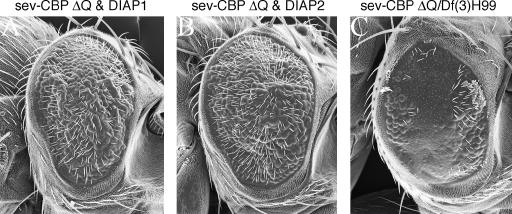

Expression of CBP ΔQ promotes cell death:

We were surprised not to have observed a suppression of the rough-eye phenotypes by the deletions that remove the cell death genes head involution defective (hid), grim, and reaper (rpr) (Wing et al. 1999; Song et al. 2000) or an enhancement by deficiencies that remove genes like DIAP1 and DIAP2 that block cell death (Song and Steller 1999; data not shown). We sought to determine if the severe rough-eye phenotypes that result from expression of either CBP ΔBHQ or CBP ΔQ can be attributed to an increase in programmed cell death.

We expressed CBP ΔBHQ in a genetic background in which the dosage of just the hid, grim, and rpr genes was reduced by 50% and observed no suppression of the rough-eye phenotype (data not shown). We also expressed both DIAP1 and DIAP2 simultaneously with CBP ΔBHQ and still observed no modification (data not shown). This suggests and supports the conclusion that an increase in cell death is not a major consequence of expressing the CBP ΔBHQ protein variant. Rather, cell fate changes account primarily for the defects observed in retinal development (Kumar et al. 2004; data not shown).

In contrast, expression of either DIAP1 or DIAP2 simultaneously with CBP ΔQ results in a strong suppression of the rough-eye phenotype (compare Figure 2G with Figure 9, A and B), suggesting that cell death is in fact a major underlying cause of defects in retinal structure. Sections of these flies reveal a dramatic increase in the number of photoreceptors and accessory cells within each ommatidium (data not shown). We did not observe a similar degree of suppression when the sev-CBP ΔQ construct was placed in trans to the H99 deficiency that removes the three cell death genes (Figure 9C). It is likely that removal of both copies of these genes is required before a modification can be observed.

Figure 9.

Cell death in the eye is increased by the expression of CBP ΔQ. (A–C) Scanning electron micrographs. (A and B) Expression of DIAP1 or DIAP2 is sufficient to suppress the cell death that results from expression of CBP ΔQ. (C) Reductions of 50% in hid, grim, and rpr are insufficient to block cell death caused by expression of CBP ΔQ. Genotypes are listed above each panel. Anterior is to the right.

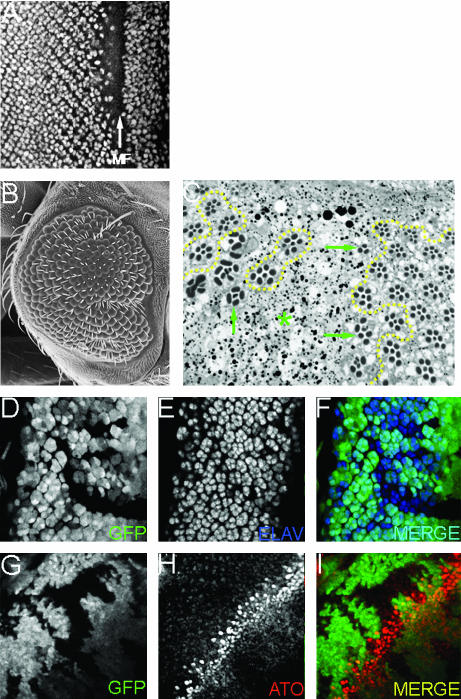

CrebA functions during eye development:

Mutations within CrebA (Cyclic-AMP response element binding protein-A) suppressed the rough-eye phenotype in flies expressing CBP ΔBHQ, suggesting that CrebA may function during eye development. CrebA had been previously implicated in the specification of the dorsal and ventral larval cuticle and the patterning of the salivary gland (Andrew et al. 1997; Rose et al. 1997). To confirm a role for CrebA in normal eye development, we determined the expression pattern of CrebA and analyzed adult and developing retinal phenotypes in loss-of-function retinal mosaic clones (Figure 10). CREB-A protein appears to be present in most cells that lie ahead of the morphogenetic furrow and in all developing photoreceptor cells (Figure 10A). This distribution of CREB protein within the developing eye retina is very similar to that of CBP (Kumar et al. 2004). Taken together with the known physical interaction between CREB and CBP, these data imply that both proteins function together in cells anterior to the furrow and in all developing photoreceptor cells.

Figure 10.

CrebA is required for normal eye development. (A) Confocal micrograph demonstrating that CREB protein is present in most cells ahead of the morphogenetic furrow in all developing photoreceptor cells. An arrow marks the morphogenetic furrow. (B) Scanning electron micrograph of an adult compound eye that contains CrebA retinal mosaic clones. Note the roughening of the surface and small areas that are devoid of ommatidia. (C) Light microscope sections of adult retinas containing CrebA retinal mosaic clones. The dotted yellow outline marks the regions of wild-type tissue. Note that along the border there are mutant ommatidia with fewer than the normal number of photoreceptor cells (green arrows). Also note that the central regions of the clone are completely devoid of ommatidia (green asterisk). (D–F) Confocal micrographs of developing retinas containing CrebA retinal mosaic clones. Within the clones the number of ELAV-positive cells is reduced, indicating that CrebA is required for photoreceptor development. (G–I) Confocal micrographs of developing retinas containing CrebA retinal mosaic clones. Within the clones the pattern of ATO localization is not altered, suggesting that CrebA is not required for the development of the R8 cell. Anterior is to the right.

We then generated loss-of-function retinal mosaic clones and assayed the effect of reductions of CrebA on developing and adult retinas. Loss of CrebA disrupted the structure of the compound eye while retinal sections suggest that CrebA is required in all photoreceptor cells (Figure 10, B and C). Entire ommatidia are absent from the center of clones (C, asterisk) while ommatidia on the border of clones have variable numbers of photoreceptors (Figure 10, B and C, arrows). A role for CREB in photoreceptor specification and development was confirmed when a significant loss of photoreceptor neurons was observed in CrebA mutant clones within developing eye imaginal discs (Figure 10, D–F). Our prior analysis of CBP loss-of-function mutant phenotypes indicated that CBP was not required for the specification of the R8 photoreceptor neuron (Kumar et al. 2004). As CREB and CBP are known to function as a heterodimer, we looked at the expression of atonal (ato), a proneural gene involved in R8 determination, in CrebA mutant clones. Similar to CBP mutant clones, the levels of ATO protein are unchanged within the CrebA clones, suggesting that CREB protein is also not required for R8 determination (Figure 10, G–I). However, the loss of other photoreceptor cells indicates that CREB, like CBP, is required for the specification and maintenance of all other photoreceptor neurons. These results are very similar to those seen in CBP loss-of-function retinal mosaic clones (Kumar et al. 2004).

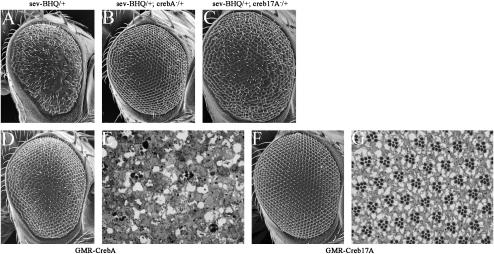

A second Drosophila CREB protein is encoded by the CrebB-17A gene (Smolik et al. 1992; Usui et al. 1993). Creb17A plays roles in circadian rhythms, long-term memory, mating behavior, and synapse formation (Yin et al. 1994, 1995a,b; Yin and Tully 1996; Belvin et al. 1999; Lamprecht 1999; Sakai and Kidokoro 2002). Reductions in Creb17A failed to modify the rough-eye phenotype that resulted from the expression of CBP variant proteins. However, it is possible that the phenotypes generated by expressing CBP proteins under the GMR promoter are too strong to be modified by just a 50% reduction in Creb17A levels. To address this issue, we placed the expression of both CBP ΔBHQ and CBP ΔQ under the control of the sev-GAL4 driver (which is significantly weaker than that of GMR-GAL4) and then removed one copy of either CrebA or Creb17A. Flies expressing CBP ΔBHQ under the control of the sev enhancer display a moderate rough eye (Figure 11A). Removing one copy of CrebA reverts the eye phenotype almost back to wild type (Figure 11B). Likewise, reductions in Creb17A levels also suppressed the rough eye albeit not to the same levels (Figure 11C). Our new interpretation of these results is that both CrebA and Creb17A function in eye development.

Figure 11.

Creb participates with CBP to regulate eye development. (A–C, D, and F) Scanning electron micrographs of the external surface of adult eyes. (E and G) Light microscope sections of adult retinas. (A–C) Note that reductions in CrebA and Creb17A are sufficient to suppress the rough-eye phenotype of sev-CBP ΔBHQ. (D and E) Expression of CrebA in photoreceptor cells results in severe retinal degeneration. (G and H) Expression of Creb17A results in mild developmental defects, including slight rotation aberrations. Genotypes are listed above or below each panel. Anterior is to the right.

The suppression of the rough-eye phenotypes caused by expression of sev-CBP ΔBHQ suggested a role for both CrebA and Creb17A in the development of photoreceptor cells. We increased the levels of both CREB genes in the eye by placing them under the control of the GMR enhancer. The external surface of GMR-CrebA flies is slightly rough with only minor alterations in the positions of individual ommatidia (Figure 11D). However, retinal sections reveal severe retinal degenerations in GMR-CrebA retinas (Figure 11E). An examination of photoreceptor development in eye imaginal discs using cell-specific markers confirms that specification of photoreceptors occurs normally (data not shown). The severity of retinal degeneration seen in GMR-CrebA retinas is quite similar to that seen when the levels of CBP are likewise increased (Figure 2B; Kumar et al. 2004). Interestingly, both loss of Creb17A function and overexpression of Creb17A did not appear to have a significant effect on eye development. Photoreceptor development in these flies appears relatively normal and retinal degeneration does not occur. Only minor positioning defects were observed (Figure 11, F and G; data not shown). Taken together, these defects suggest that CBP cooperates mainly with CREB-A to influence eye development and that interactions with CREB-17A may play at best a minor role within the retina.

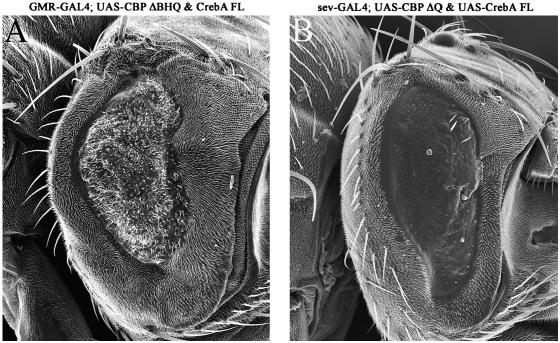

CREB and CBP cooperate genetically during eye development:

Our loss-of-function and overexpression assays along with the results from our genetic screens suggest that CBP and CREB may function together, at least in certain contexts, during normal eye development (Kumar et al. 2004; this report). We further sought to examine this interaction by coexpressing the CBP ΔBHQ and CBP ΔQ protein variants with a wild-type version of CREB-A. These variants of CBP were chosen since mutations in CrebA modified the rough-eye phenotypes that resulted from expression of CBP ΔBHQ and CBP ΔQ proteins. Coexpression of CBP ΔBHQ and CREB-A FL strongly enhanced the rough-eye phenotype of CBP ΔBHQ alone (compare Figures 2E and 11D with 12A). Coexpression of CBP ΔQ and CREB FL also gave a very strong enhancement of the CBP ΔQ rough-eye phenotype (compare Figures 2G and 11D with 12B). Together these results further suggest that CREB and CBP function together during eye development.

Figure 12.

CREB and CBP function cooperatively to influence eye development. (A and B) Scanning electron micrographs of the external surface of adult eyes. Coexpression of CREB-A and CBP ΔBHQ (A) or CBP ΔQ (B) leads to an enhancement of the rough-eye phenotype. Genotypes are listed above each panel. Anterior is to the right.

Increased levels of CREB ahead of the furrow promote eye development:

We previously showed that CBP functions during eye specification by interacting with sine oculis and eyes absent, two critical components of the retinal determination cascade (Kumar et al. 2004). We sought to determine if CREB might also play a role in early eye development. Unlike members of the retinal determination network, neither CBP nor CREB has the ability to support eye development on their own in ectopic expression experiments (i.e., antennae, legs, wings, and halteres; data not shown). Furthermore, transcription of the retinal determination genes is not induced by expression of either CREB or CBP (data not shown). Thus, any potential interaction between CBP (and presumably CREB) and the eye specification proteins is likely to be through physical protein-protein interactions or to require the activity of additional factors.

The eye specification genes are expressed within the eye antennal disc, including small areas of the disc that give rise not to the eye but to parts of the surrounding head capsule. We used an ey-GAL4 driver to direct expression of CrebA to these regions. The eyeless enhancer used in these experiments drives expression ahead of the morphogenetic furrow. The eyes of ey-GAL4/UAS-Creb FL flies are mildly rough (Figure 13A). However, a small ectopic eye is present along the ventral margin of the eye (Figure 13A, arrow). It is separated from the normal compound eye by a small zone of head cuticle. Antibodies directed against the DAC and EYA proteins marked the areas in the ventral zones of the eye disc that would give rise to ectopic eyes (Figure 13, B and C, arrows). The zone of separation between the normal compound eye and the smaller ectopic eye seen in Figure 13, B and C, is marked with an arrowhead. The eye specification gene eye gone (eyg) also directs eye formation on the ventral surface of the fly head and nowhere else (Jang et al. 2003). In contrast, ectopic eyes that are generated by expression of the ey and twin of eyeless (toy) genes are not found on the head but rather are located on the antennae, legs, wings, and halteres. Our results suggest the CREB-A transcription factor might function together with the Pax protein EYG to promote retinal development.

Figure 13.

CREB expression promotes ectopic eye development along the ventral margin of the fly head. (A) Scanning electron micrograph of adult eye. (B and C) Confocal images of developing eye antennal imaginal discs. Expression of CREB along the ventral margin of the head promotes eye development. Genotypes are listed at the left. Visualized proteins are listed in B and C. Arrows in A–C mark the formation of an ectopic eye. Arrowheads in B and C mark the zone of separation of the ectopic eye from the normal compound eye. Anterior is to the right.

CBP interacts genetically with members of the eye specification cascade:

We previously observed interactions between CBP and members of the eye specification cascade (Kumar et al. 2004). For instance, the expression pattern of CBP mimics that of the retinal determination genes in the regions of the epithelium ahead of the morphogenetic furrow. Second, nejire was identified in a screen for genes that interacted with sine oculis. And finally, we observed a drastic reduction in the expression of eyes absent within loss-of-function nejire retinal mosaic clones. These results suggested that nejire interacts with both sine oculis and eyes absent. We were surprised that reductions in neither sine oculis nor eyes absent were sufficient to modify the rough-eye phenotypes that resulted from the expression of CBP variant proteins in our initial screens. However, a putative role for CBP in early eye development is supported by the observation that reductions in eyeless suppressed the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ rough-eye phenotype (Figure 5I).

It is possible that the rough-eye phenotypes that we induced by expression of each CBP variant were too strong to detect reductions in the dosages of the other members of the retinal determination network. We took advantage of the temperature sensitivity of the GAL4 protein and reared GMR-CBP ΔBHQ flies at 18°. At this temperature the rough eye is considerably milder than that seen when flies are reared at 25° (compare Figures 2E and 14A). Only reductions in eye absent were sufficient to modify the rough-eye phenotype of GMR-CBP ΔBHQ under these conditions (Figure 14, B–D). This is consistent with the loss of eyes absent expression in nejire mutant clones (Kumar et al. 2004) and suggests that CBP functions genetically upstream of eyes absent. Reductions in levels of SO and DAC protein did not alter the phenotype of CBP ΔBHQ expression (Figure 14, B and C). Our model is that sine oculis functions upstream of nejire since a genetic interaction between the two was established through genetic screens (Kumar et al. 2004). However, CBP does not appear to interact or to regulate dachshund since its expression is normal in nejire retinal clones (Kumar et al. 2004) and reductions in dachshund do not modify the rough-eye phenotype of CBP expression (Figure 13B). Thus CBP interacts with several, but not all, members of the retinal determination cascade, including eyeless, sine oculis, and eyes absent. Furthermore, these interactions are also likely to involve the CREB transcription factor.

Figure 14.

Interactions between CBP and the retinal determination genes. (A–D) Scanning electron micrograph of adult eyes. Genotypes are listed above each panel. Anterior is to the right. (A) Expression of CBP ΔBHQ at 18° has a milder rough eye. (B–D) Reductions in the dosage of eyes absent enhance the rough-eye phenotype.

DISCUSSION

CBP plays a pivotal role in both insect and mammalian eye development. Mutations within nejire, which encodes for the Drosophila homolog of CBP, inhibit eye development at several stages, including eye determination and photoreceptor cell specification (Ludlam et al. 2002; Taylor et al. 2003; Kumar et al. 2004). Likewise, lesions within human CBP are known to be the underlying cause of Rubenstein-Taybi syndrome which is characterized, in part, by several retinal disorders, including strabismus, juvenile glaucoma, cataracts, and coloboma of the eyelid, lens, and iris (Petrij et al. 1995; Tanaka et al. 1997; Oike et al. 1999; Murata et al. 2001; Coupry et al. 2002; Kalkhoven et al. 2003). Through the use of several genetic screens we sought to identify genes that function cooperatively with CBP to influence eye development. We expressed either wild type or one of three variants of CBP within the developing eye of Drosophila (Figure 1). The expression of each CBP protein resulted in a disruption of eye development that is easily visualized by an examination of the external surface of adult eyes. The degree of structural alteration and the underlying cause of the disruption are unique to the expression of each individual CBP protein (Figure 2).

The retinal phenotypes that are generated by the expression of CBP variant proteins reveal considerable information on the role that CBP plays in normal eye development. Each variant protein retains a unique combination of protein domains and is expected to act as a protein sink by binding and soaking up signaling pathway components and transcription factors. Thus the changes in eye specification and ommatidial cell fate are due to a “loss” of factors that normally function in these processes. Since CBP appears to be normally expressed in every cell within the developing retina, it is likely that the putative transcriptional targets and binding partners of CBP that we identified in our screens are biologically relevant for eye development.

We took advantage of the Bloomington Stock Center deficiency kit to rapidly identify regions of the genome that potentially harbor interacting genes (Figure 3). Through this method we initially identified 71 such regions. We then screened extant single-gene mutants and identified 35 complementation groups that potentially interact with CBP (Figures 3, 4, 5, and 7; Table 1). We were unable to identify interacting genes for the remaining 36 genomic intervals (Figures 3, 4, 6, and 8; Table 2). This is likely due to the lack of single-gene mutations for all predicted genes. Alternatively, it is possible that these regions contain two or more genes that must be removed simultaneously to modify the rough-eye phenotypes associated with CBP expression.

Among the collection of potential interacting genes, our screens identified members of the eye specification cascade, two Hox genes, the CREB transcription factor, and several members of the EGFR and TGFβ signaling cascades. Our recovery of these factors in the course of an “eye screen” is supported by known interactions between CBP and many of these factors in other developmental contexts. For instance, CBP is known to interact with the TGFβ signaling pathway during several stages of embryonic development (Waltzer and Bienz 1999; Ashe et al. 2000; Newfeld and Takaesu 2002). Likewise, CBP is known to participate in the regulation of several Hox genes (Florence and McGinnis 1998; Petruk et al. 2001). As another example, CBP is known to interact with the retinal determination genes in both the fly retina and mouse muscle (Ikeda et al. 2002; Kumar et al. 2004). Furthermore, interactions between CBP and CREB have been well documented in a number of contexts, including learning and memory and synapse formation (Yin et al. 1994, 1995a, b; Yin and Tully 1996; Marek et al. 2000). And finally, the CREB-CBP complex is known to be phosphorylated by RSK, a known component of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling cascades (Frodin and Gammeltoft 1999). Thus, it is exciting that we are now able to link CBP to the EGFR pathway during eye development. These results are further supported by the fact that loss-of-function mutations in either CBP or members of the EGFR cascade lead to near-identical phenotypes in the eye, wing, leg, and embryo of Drosophila. Our screens connect CBP directly to this signaling system.

It should be noted that the approach used in this report to find genes that potentially interact with CBP revealed interactions that would not have been found if we had limited ourselves to a single screen in which we looked for modifiers of the GMR-CBP FL rough-eye phenotype. In that screen we recovered only two deficiency stocks that could modify the rough eye. Since CBP interacts with well over 100 different proteins, the reduction in any one is unlikely to alter the GMR-CBP FL rough-eye phenotype significantly. Our empirical results (Figure 4; Tables 1 and 2) bear this out. By expressing CBP protein variants, each containing a unique combination of functional domains, we were able to induce retinal phenotypes that could be modified by reductions in single-gene dosages.

Another novel aspect of these genetic screens is that not only have we been able to find factors that interact with or are regulated by CBP, but also we have some information about how they modulate the activity of this coactivator. For instance, CBP ΔBHQ retains the N-terminal half of the protein (Figure 1), which includes a zinc-finger domain, a nuclear hormone receptor binding domain, and the CREB-binding domain. We predict that the genes identified as suppressors of the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ rough-eye phenotype may be bound by the zinc-finger domain of CBP or the CREB transcription factor. Alternatively, these genes may encode proteins that interact with the N-terminal portion of CBP. For example, the CBP ΔBHQ protein can still interact with the CREB transcription factor through the KIX domain. Previous reports have demonstrated that CREB is phosphorylated by RSK, a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase signaling cascade. Our screen for modifiers of the GMR-CBP ΔBHQ phenotype yielded several members of the EGFR signaling cascade. We predict that the results from these screens will provide insight into how the modular activity of CBP can be integrated with the remaining interacting genes and proteins.

In a significant fraction of cases it remains to be determined which of the newly identified factors will turn out to be binding partners, transcriptional targets, or upstream regulators of CBP. This is especially true of many genes that have had no previously ascribed role in eye development. In addition to standard genetic practices of examining phenotypes of loss-of-function mutants, several high-throughput methods, including yeast two-hybrid assays and genomic microarrays, will certainly be useful in sorting out the regulatory relationship between CBP and the interacting genes described in this report. As CBP is thought to function as a biochemical scaffold (Goodman and Smolik 2000; Chan and La Thangue 2001), our results support a role for CBP in integrating instructions from multiple signaling pathways and regulatory networks.

One of the most interesting results from our screen is the identification of CREB as a potential regulator of eye development. The interactions between CREB and CBP are well known and have been described for several developmental contexts (Kwok et al. 1994; Nordheim 1994). However, this is the first report of a potential role for CREB in Drosophila eye development. We have demonstrated that CREB-A is expressed in cells ahead of the morphogenetic furrow and in all developing photoreceptor cells. Loss-of-function retinal mosaic clones indicate that the CREB-A transcription factor is required in all photoreceptor cells with the exception of R8. This phenotype is consistent with that seen in CBP loss-of-function retinal mosaic clones. Interestingly, ectopic expression of CrebA is sufficient to induce ectopic eye formation on the ventral surface of the fly head, a phenotype seen when the Pax protein EYG is itself ectopically expressed. This might place the CBP-CREB complex within the retinal determination network. While it has been reported that activation of CREB in the vertebrate retina blocks degeneration of retinal ganglion cells (Choi et al. 2003), it is exciting to speculate on potential roles for CREB in the determination of the vertebrate eye and for the specification of vertebrate cell types. It would also be interesting to determine if mutations within human CREB might also be associated with the same retinal phenotypes observed in patients harboring lesions with CBP.

Of the 36 genomic regions for which we have not identified the genetic loci that are responsible for the modification of the rough-eye phenotypes, three regions are of particular interest because our results suggest that the interacting gene or the encoded protein interacts specifically with the N-terminal half of CBP. Deletion of the 76B4-77B1 interval suppresses the rough-eye phenotypes that are associated with expression of CBP FL, CBP ΔBHQ, and CBP ΔQ proteins while enhancing the CBP ΔNZK retinal phenotype. These results suggest that at least one interacting gene resides within this interval and that it is either a target of or the encoded protein in a binding partner of the N-terminal region of CBP. Deletions of the 96F1-97B1 interval enhance the rough-eye phenotypes that result from expression of CBP ΔBHQ and CBP ΔQ proteins. Likewise, deletions of the 5C3-6C12 interval suppress the retinal phenotypes of CBP ΔBHQ and CBP ΔQ expression. In both situations it is likely that the interacting gene or its encoded protein functions specifically with the N-terminal domain of CBP. The remaining 33 regions modified the expression of specific constructs (Table 2). It will be interesting to determine if they encode for members of a common pathway or if they represent a set of factors within differing activities.

Despite the tremendous focus on the development of the insect and vertebrate retinas, our understanding of how the eye is constructed is still in its earliest stages. An unresolved issue relates to the molecular and biochemical mechanisms by which the eye is specified and patterned. On the basis of the loss-of-function phenotypes in both Drosophila and human patients, it appears that CBP plays a pivotal role in nearly all stages of retinal development. Additionally, it is known that CBP influences development by interacting with members of the basal transcriptional machinery, sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins, nuclear hormone receptors, and terminal members of several signaling transduction cascades. CBP also affects developmental processes by binding to acetylated histones during phases of chromatin remodeling and contains several putative zinc-finger DNA-binding domains. In this report we have conducted a series of genetic screens and have identified 35 genes that potentially interact with CBP to influence retinal development at successive stages. Some of these genes already have established roles during eye development while a significant number of genes, despite having well-documented roles in nonretinal tissues, are completely new to eye development. And for the remaining genes, a role in eye development represents the only known information that we have about their role in insect development. Furthermore, the remaining unmapped loci represent at least an additional 36 genes that are likely to be involved in eye development. It will be exciting to see how each of these genes interacts with CBP to regulate the construction of the eye, which may provide some insight into Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. It also represents an opportunity to begin to further our understanding of how instructions from signaling cascades are integrated with the activities of hundreds of transcription factors. This paradigm is not specific to the eye but is a common theme in the development of complex systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gerald Rubin, Graeme Mardon, Seymour Benzer, Joseph Duffy, Larry Zipursky, Nancy Bonini, Walter Gehring, Lucy Cherbas, Debbie Andrew, Mani Ramaswami, the Bloomington Stock Center, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for gifts of fly stocks and antibodies. We also thank F. Rudolf Turner for technical support with the scanning electron micrographs and adult retinal sections. This work was supported by a grant from the National Eye Institute (R01 EY014863) to Justin P. Kumar.

References

- Abrell, S., P. Carrera and H. Jackle, 2000. A modifier screen of ectopic Kruppel activity identifies autosomal Drosophila chromosomal sites and genes required for normal eye development. Chromosoma 109: 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akam, M. E., A. Martinez-Arias, R. Weinzierl and C. D. Wilde, 1985. Function and expression of ultrabithorax in the Drosophila embryo. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 50: 195–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimaru, H., Y. Chen, P. Dai, D. X. Hou, M. Nonaka et al., 1997. a Drosophila CBP is a co-activator of cubitus interruptus in hedgehog signalling. Nature 386: 735–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimaru, H., D. X. Hou and S. Ishii, 1997. b Drosophila CBP is required for dorsal-dependent twist gene expression. Nat. Genet. 17: 211–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, D. J., A. Baig, P. Bhanot, S. M. Smolik and K. D. Henderson, 1997. The Drosophila dCREB-A gene is required for dorsal/ventral patterning of the larval cuticle. Development 124: 181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arany, Z., W. R. Sellers, D. M. Livingston and R. Eckner, 1994. E1A-associated p300 and CREB-associated CBP belong to a conserved family of coactivators. Cell 77: 799–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe, H. L., M. Mannervik and M. Levine, 2000. Dpp signaling thresholds in the dorsal ectoderm of the Drosophila embryo. Development 127: 3305–3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avantaggiati, M. L., V. Ogryzko, K. Gardner, A. Giordano, A. S. Levine et al., 1997. Recruitment of p300/CBP in p53-dependent signal pathways. Cell 89: 1175–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, N. E., S. Yu and D. Han, 1996. Evolution of proneural atonal expression during distinct regulatory phases in the developing Drosophila eye. Curr. Biol. 6: 1290–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister, A. J., and T. Kouzarides, 1996. The CBP co-activator is a histone acetyltransferase. Nature 384: 641–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantignies, F., R. H. Goodman and S. M. Smolik, 2000. Functional interaction between the coactivator Drosophila CREB-binding protein and ASH1, a member of the trithorax group of chromatin modifiers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 9317–9330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basler, K., P. Siegrist and E. Hafen, 1989. The spatial and temporal expression pattern of sevenless is exclusively controlled by gene-internal elements. EMBO J. 8: 2381–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvin, M. P., H. Zhou and J. C. Yin, 1999. The Drosophila dCREB2 gene affects the circadian clock. Neuron 22: 777–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeret, E., I. Pignot-Paintrand, A. Guichard, K. Raymond, M. O. Fauvarque et al., 2001. RotundRacGAP functions with Ras during spermatogenesis and retinal differentiation in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 6280–6291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehs, B., V. Francois and E. Bier, 1996. The Drosophila short gastrulation gene prevents Dpp from autoactivating and suppressing neurogenesis in the neuroectoderm. Genes Dev. 10: 2922–2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowtell, D. D., B. E. Kimmel, M. A. Simon and G. M. Rubin, 1989. Regulation of the complex pattern of sevenless expression in the developing Drosophila eye. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86: 6245–6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan, K. M., and R. Nusse, 1996. wingless signaling in the Drosophila eye and embryonic epidermis. Development 122: 2801–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagan, R. L., and D. F. Ready, 1989. The emergence of order in the Drosophila pupal retina. Dev. Biol. 136: 346–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti, D., V. J. LaMorte, M. C. Nelson, T. Nakajima, I. G. Schulman et al., 1996. Role of CBP/P300 in nuclear receptor signalling. Nature 383: 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, H. M., and N. B. La Thangue, 2001. p300/CBP proteins: HATs for transcriptional bridges and scaffolds. J. Cell Sci. 114: 2363–2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. S., J. A. Kim and C. K. Joo, 2003. Activation of MAPK and CREB by GM1 induces survival of RGCs in the retina with axotomized nerve. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44: 1747–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrivia, J. C., R. P. Kwok, N. Lamb, M. Hagiwara, M. R. Montminy et al., 1993. Phosphorylated CREB binds specifically to the nuclear protein CBP. Nature 365: 855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupry, I., C. Roudaut, M. Stef, M. A. Delrue, M. Marche et al., 2002. Molecular analysis of the CBP gene in 60 patients with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 39: 415–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decotto, E., and E. L. Ferguson, 2001. A positive role for Short gastrulation in modulating BMP signaling during dorsoventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo. Development 128: 3831–3841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z., C. J. Chen, M. Chamberlin, F. Lu, G. A. Blobel et al., 2003. The CBP bromodomain and nucleosome targeting are required for Zta-directed nucleosome acetylation and transcription activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 2633–2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, B., and E. Hafen, 1993. Genetic dissection of eye development in Drosophila, pp. 1327–1361 in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, edited by M. Bate and A. Martinez Arias. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Dokucu, M. E., S. L. Zipursky and R. L. Cagan, 1996. Atonal, rough and the resolution of proneural clusters in the developing Drosophila retina. Development 122: 4139–4147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl, D. F., and A. J. Hilliker, 1988. Characterization of X-linked recessive lethal mutations affecting embryonic morphogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 118: 109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florence, B., and W. McGinnis, 1998. A genetic screen of the Drosophila X chromosome for mutations that modify Deformed function. Genetics 150: 1497–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossett, N., K. Hyman, K. Gajewski, S. H. Orkin and R. A. Schulz, 2003. Combinatorial interactions of serpent, lozenge, and U-shaped regulate crystal cell lineage commitment during Drosophila hematopoiesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 11451–11456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois, V., M. Solloway, J. W. O'Neill, J. Emery and E. Bier, 1994. Dorsal-ventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo depends on a putative negative growth factor encoded by the short gastrulation gene. Genes Dev. 8: 2602–2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frodin, M., and Gammeltoft, S., 1999. Role and regulation of 90kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) in signal transduction. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 151: 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M., 1996. Reiterative use of the EGF receptor triggers differentiation of all cell types in the Drosophila eye. Cell 87: 651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M., B. E. Kimmel and G. M. Rubin, 1992. Identifying targets of the rough homeobox gene of Drosophila: evidence that rhomboid functions in eye development. Development 116: 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, P. S., V. K. Tran and R. H. Goodman, 1997. The multifunctional role of the co-activator CBP in transcriptional regulation. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 52: 103–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. H., and S. Smolik, 2000. CBP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development. Genes Dev. 14: 1553–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, W., X. L. Shi and R. G. Roeder, 1997. Synergistic activation of transcription by CBP and p53. Nature 387: 819–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guion-Almeida, M. L., and A. Richieri-Costa, 1992. Callosal agenesis, iris coloboma, and megacolon in a Brazilian boy with Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 43: 929–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, N. C., J. Thorpe and T. Schüpbach, 1996. Encore, a gene required for the regulation of germ line mitosis and oocyte differentiation during Drosophila oogenesis. Development 122: 281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay, B. A., D. A. Wassarman and G. M. Rubin, 1995. Drosophila homologs of baculovirus inhibitor of apoptosis proteins function to block cell death. Cell 83: 1253–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein, U., and K. Moses, 1995. Mechanisms of Drosophila retinal morphogenesis: the virtues of being progressive. Cell 81: 987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, K., Y. Watanabe, H. Ohto and K. Kawakami, 2002. Molecular interaction and synergistic activation of a promoter by Six, Eya, and Dach proteins mediated through CREB binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 6759–6766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang, C. C., J. L. Chao, N. Jones, L. C. Yao, D. A. Bessarab et al., 2003. Two Pax genes, eye gone and eyeless, act cooperatively in promoting Drosophila eye development. Development 130: 2939–2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janknecht, R., 2002. The versatile functions of the transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP and their roles in disease. Histol. Histopathol. 17: 657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman, A. P., E. H. Grell, L. Ackerman, L. Y. Jan and Y. N. Jan, 1994. atonal is the proneural gene for Drosophila photoreceptors. Nature 369: 398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman, A. P., Y. Sun, L. Y. Jan and Y. N. Jan, 1995. Role of the proneural gene, atonal, in formation of Drosophila chordotonal organs and photoreceptors. Development 121: 2019–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkhoven, E., J. H. Roelfsema, H. Teunissen, A. den Boer, Y. Ariyurek et al., 2003. Loss of CBP acetyltransferase activity by PHD finger mutations in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12: 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee, B. L., J. Arias and M. R. Montminy, 1996. Adaptor-mediated recruitment of RNA polymerase II to a signal-dependent activator. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 2373–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, B. E., U. Heberlein and G. M. Rubin, 1990. The homeo domain protein rough is expressed in a subset of cells in the developing Drosophila eye where it can specify photoreceptor cell subtype. Genes Dev. 4: 712–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, S., M. Okabe, N. Hacohen, M. A. Krasnow and Y. Hiromi, 1999. Sprouty: a common antagonist of FGF and EGF signaling pathways in Drosophila. Development 126: 2515–2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. P., 2001. Signalling pathways in Drosophila and vertebrate retinal development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 846–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. P., and K. Moses, 1997. Transcription factors in eye development: A gorgeous mosaic? Genes Dev. 11: 2023–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. P., and K. Moses, 2001. Eye specification in Drosophila: perspectives and implications. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 12: 469–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. P., M. Tio, F. Hsiung, S. Akopyan, L. Gabay et al., 1998. Dissecting the roles of the Drosophila EGF receptor in eye development and MAP kinase activation. Development 125: 3875–3885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. P., F. Hsiung, M. A. Powers and K. Moses, 2003. Nuclear translocation of activated MAP kinase is developmentally regulated in the developing Drosophila eye. Development 130: 3703–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. P., T. Jamal, A. Doetsch, F. R. Turner and J. B. Duffy, 2004. CREB binding protein functions during successive stages of eye development in Drosophila. Genetics 168: 877–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwok, R. P., J. R. Lundblad, J. C. Chrivia, J. P. Richards, H. P. Bachinger et al., 1994. Nuclear protein CBP is a coactivator for the transcription factor CREB. Nature 370: 223–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht, R., 1999. CREB: a message to remember. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 55: 554–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. R., S. Urban, C. F. Garvey and M. Freeman, 2001. Regulated intracellular ligand transport and proteolysis control EGF signal activation in Drosophila. Cell 107: 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, N. S., 1976. Juvenile glaucoma in the Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. 13: 141–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilja, T., D. Qi, M. Stabell and M. Mannervik, 2003. The CBP coactivator functions both upstream and downstream of Dpp/Screw signaling in the early Drosophila embryo. Dev. Biol. 262: 294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]