Abstract

Rice qUVR-10, a quantitative trait locus (QTL) for ultraviolet-B (UVB) resistance on chromosome 10, was cloned by map-based strategy. It was detected in backcross inbred lines (BILs) derived from a cross between the japonica variety Nipponbare (UV resistant) and the indica variety Kasalath (UV sensitive). Plants homozygous for the Nipponbare allele at the qUVR-10 locus were more resistant to UVB compared with the Kasalath allele. High-resolution mapping using 1850 F2 plants enabled us to delimit qUVR-10 to a <27-kb genomic region. We identified a gene encoding the cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) photolyase in this region. Activity of CPD photorepair in Nipponbare was higher than that of Kasalath and nearly isogenic with qUVR-10 [NIL(qUVR-10)], suggesting that the CPD photolyase of Kasalath was defective. We introduced a genomic fragment containing the CPD photolyase gene of Nipponbare to NIL(qUVR-10). Transgenic plants showed the same level of resistance as Nipponbare did, indicating that the qUVR-10 encoded the CPD photolyase. Comparison of the qUVR-10 sequence in the Nipponbare and Kasalath alleles revealed one probable candidate for the functional nucleotide polymorphism. It was indicated that single-base substitution in the CPD photolyase gene caused the alteration of activity of CPD photorepair and UVB resistance. Furthermore, we were able to develop a UV-hyperresistant plant by overexpression of the photolyase gene.

BECAUSE plants need to capture sunlight for photosynthesis, they are unavoidably exposed to the harmful effects of solar ultraviolet-B (UVB) radiation. To avoid UV-induced damage, plants have evolved UV-defense mechanisms such as the accumulation of UV-absorbing compounds (Bharti and Khurana 1997), antioxidant enzymes and compounds (Strid et al. 1994; Mackerness and Jordan 1999), and efficient DNA repair (Britt 1999).

Absorption of UVB causes DNA lesions, such as cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidone photoproducts (6-4pps) (Mitchell and Nairn 1989). Both photoproducts block transcription, and replication of altered DNA causes heritable mutations (Britt 1999). Therefore elimination of such photoproducts is essential for plants to survive.

Photoproducts are removed from DNA by evolutionarily conserved nucleotide excision repair (NER) in all organisms (Thoma 1999). NER is a complex multi-step process consisting of the concerted action of many gene products and includes damage recognition, excision of oligonucleotides containing DNA lesions, gap-filling DNA synthesis, and DNA ligation (Britt 1999). The characterization of laboratory-induced UV-sensitive mutants is a powerful tool for studying NER in plants. AtRAD1 and AtRAD2, which encode NER endonucleases, have been isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana by analysis of the UV-hypersensitive mutants uvh1 and uvh3, respectively (Gallego et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2000, 2001). AtXPB1 and AtXPD, which are homologs of a human DNA helicase essential for NER, have been characterized by a UV-hypersensitive mutant, uvh8, and a T-DNA insertion line, respectively (Costa et al. 2001; Liu et al. 2003). Recently, it was reported that the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase ζ (AtREV3), which is thought to be involved in translesion synthesis, was disrupted in a UV-light-sensitive mutant, rev3-1, of Arabidopsis (Sakamoto et al. 2003).

An additional repair system, photorepair, removes UV-induced lesions in many organisms except placental mammals (Menck 2002). During photorepair, enzymes known as DNA photolyases use blue/UVA light energy to reverse CPDs or 6-4 pps directly (Britt 1999). Photolyases show substrate specificity for either CPDs (CPD photolyase) or 6-4 pps (6-4 photolyase). The DNA photolyases have been divided into two classes on the basis of sequence homology. Microbial CPD photolyase and 6-4 photolyase are class I photolyases, which show remarkable homology to blue-light receptors. Class II photolyases include higher eukaryotic CPD photolyases (Kanai et al. 1997). These two classes of CPD photolyases share only 10–15% sequence similarity (Yasui et al. 1994). Homologs of CPD and/or 6-4 photolyase have been cloned from various plant species, such as Arabidopsis (Ahmad et al. 1997; Nakajima et al. 1998), single-cell alga (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) (Petersen et al. 1999), cucumber (Cucumis sativus) (Takahashi et al. 2002), and rice (Oryza sativa) (Hirouchi et al. 2003). Arabidopsis mutants of CPD and 6-4 photolyase genes (uvr2 and uvr3, respectively) are hypersensitive to UV radiation (Ahmad et al. 1997; Jiang et al. 1997; Landry et al. 1997; Nakajima et al. 1998).

Although rice cultivars show wide variations in the level of UVB resistance, laboratory-induced mutants showing UV resistance or sensitivity have not been reported. Sato and Kumagai (1993) reported that most indica cultivars are more UV sensitive than japonica cultivars. Among japonica cultivars, Sasanishiki is resistant to UV radiation, whereas Norin 1 is sensitive (Hidema et al. 1996). This cultivar difference in UV resistance is derived from the activity of photorepair, NER, and accumulation of UV-absorbing compounds (Hidema et al. 1997; Sato and Kumagai 1997). The UV-sensitive cultivar Norin 1 contains a defective CPD photolyase (Hidema et al. 2000). Recently a cDNA clone of CPD photolyase in Sasanishiki was isolated (Hirouchi et al. 2003) and nucleotide sequence comparison between Sasanishiki and Norin 1 CPD photolyase gene indicated that a single amino acid alteration caused the deficit of CPD photolyase activity (Teranishi et al. 2004).

In a previous study, Sato et al. (2003) performed quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis to study UVB resistance and identified three QTL on chromosomes 1, 3, and 10 by using backcross inbred lines derived from a cross between a japonica cultivar, Nipponbare (UVB resistant), and an indica cultivar, Kasalath (UVB sensitive). Nipponbare alleles of the QTL on chromosomes 1 and 10 showed more UVB resistance than Kasalath alleles did, unlike the QTL on chromosome 3. Among the three QTL, qUVR-10 (QTL for ultraviolet-B resistance on chromosome 10) showed the largest allelic difference. By using 198 plants in a segregating population, we mapped qUVR-10 as a single Mendelian factor and found a CPD photolyase gene and four putative chalcone synthase genes as functional and positional candidates in the qUVR-10 region (Ueda et al. 2004). However, the molecular nature of qUVR-10 remained to be clarified.

This article describes the molecular identification of qUVR-10 by high-resolution mapping using 1850 segregants. We found that qUVR-10 encodes a CPD photolyase gene. A single-base substitution in the allele of Kasalath reduces CPD photorepair activity in vitro. Furthermore, elevated levels of the CPD photolyase mRNA enhance the UV resistance of transgenic rice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials:

The rice (O. sativa L.) cultivar Nipponbare was crossed with Kasalath, and a resultant F1 plant was backcrossed with Nipponbare. Successive backcrossing and marker-associated selection allowed us define to a plant in which the region around qUVR-10 was heterozygous and almost all other regions were homozygous for Nipponbare. Self-pollinated progeny of this plant were used for high-resolution mapping of qUVR-10. NIL(qUVR-10) was developed from a cross between Nipponbare and the chromosomal segment substitution line (SL)-77, which was used to confirm the existence of qUVR-10 (Sato et al. 2003). From the self-pollinated progeny, we selected a plant whose qUVR-10 region was homozygous for the Kasalath allele, whereas all other chromosomal regions were homozygous for Nipponbare alleles (Figure 1A).

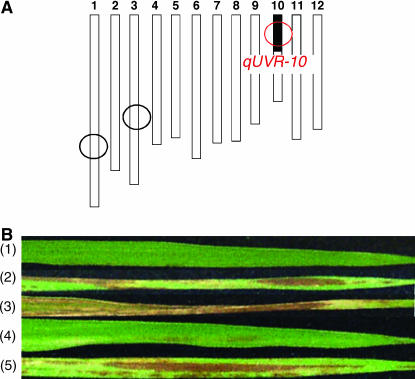

Figure 1.

Plants used in this study. (A) Graphical genotype of NIL(qUVR-10). Solid and open regions represent segments of chromosome derived from Kasalath and Nipponbare, respectively. Circles indicate QTL detected by using BILs (Sato et al. 2003). (B) Necrotic lesion on leaf after 3 weeks of UVB radiation at 1 W m−2. Nontransgenic controls: (1) Nipponbare, (2) Kasalath, (3) NIL(qUVR-10). Transgenic plants: (4) NIL(qUVR-10) with a single copy of Nipponbare genomic fragment of CPD photolyase (T2-76-14) (Table 3), (5) NIL(qUVR-10) with empty vector. The efficiency of CPD photorepair in T2-76-14 was the same as in Nipponbare (data not shown).

UVB irradiation:

Plants were UVB irradiated according to the method of Sato and Kumagai (1997). Visible light was supplied by a combination of high-intensity discharge lamps [Toshiba DR400/T(L), Toshiba, Tokyo] and fluorescent lamps (Toshiba RF 220V, 200WH). The source of UVB radiation was supplied by Toshiba FL20 SE fluorescent tubes. These lamps were suspended above the rice plants and wrapped with 0.1 mm of cellulose diacetate film (Cadillac Plastic, Baltimore) to eliminate UV radiation with wavelengths <290 nm. Seeds of each line were sown and maintained at 25°/18° (day/night) with a 12-hr photoperiod in a growth cabinet (Koitotron type KG, Koito, Tokyo). Seedlings were allowed to grow for 3 weeks under visible light with UVB radiation. UVB irradiance at the top of the leaf canopy was from 1.0 to 1.3 W m−2, as measured with a spectroradiometer (SS-25; Japan Spectroscopic, Tokyo). The dose of biologically effective UVB radiation (UVBBE) was calculated from the generalized plant action spectrum of Caldwell (1971), normalized to unity at 300 nm. The amount of UVBBE (kilojoules per square meter per day) applied daily was 17.8.

Linkage analysis:

We grew 1850 F2 plants in the field under natural summer conditions in Tsukuba, Japan. Plants with recombination around the qUVR-10 region were selected by using the region-specific cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) markers R1933 and C8 (http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/publicdata/caps/index.html). The strategy for qUVR-10 mapping was described by Ueda et al. (2004). In brief, we grew F3 lines obtained from the selected F2 plants and then selected two F3 plants, one homozygous for the recombinant chromosome and one for the nonrecombinant, from each of the F3 lines. For linkage analysis, self-pollinated progeny (F4 families) of the two plants were UVB irradiated for F4 progeny testing. We observed phenotypic differences among the F4 families in the occurrence of necrotic lesions on each leaf (50 plants in each line) after 3 weeks of UV irradiation. Nipponbare, Kasalath, and NIL(qUVR-10) were used as genotype references in the progeny testing. When both F4 families were either UVB resistant or UVB sensitive, we presumed that the F2 plant was homozygous for the Nipponbare or Kasalath allele, respectively, at qUVR-10. We assumed that the plants were heterozygous when the F4 families showed different reactions to UVB. Lines RS24-12 and RS24-13 were F4 lines derived from the same F2 plant, which was heterozygous at qUVR-10. Plant lines used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Plant lines used in this study

| Plant line | Generation | CPD photolyasea | Necrotic lesionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nipponbare | Parent | N | Few |

| Kasalath | Parent | K | Many |

| NIL(qUVR-10)c | NIL | K | Many |

| RS24-23 | F4 | rec | Few |

| RS24-12 | F4 | N | Few |

| RS24-13c | F4 | K | Many |

Genotype of CPD photolyase gene: N, homozygous for Nipponbare; K, homozygous for Kasalath; rec, plant with recombinant point in CPD photolyase gene.

Number of necrotic lesion after 3 weeks of 1.0 W m−2 UVB irradiation.

Both NIL(qUVR-10) and RS24-13 were used for transformation.

Screening of Nipponbare genomic library and DNA marker development:

We used a P1-derived artificial chromosome (PAC) library derived from the Nipponbare genome (Baba et al. 2000) and 18,432 clones from this library for PCR-based screening with C913A and S1757S (Table 2). PAC end-fragments were cloned with the cassette PCR method (Isegawa et al. 1992). We selected a PAC clone that contains the candidate region of qUVR-10 (P0025D06). P0025D06 was sequenced using a shotgun approach. To develop additional PCR-based markers, we analyzed sequences of PCR fragments derived from the Kasalath genome by using primers designed from the PAC clone and compared with the Nipponbare PAC clone and the PCR fragment (Kasalath) sequences. PCR-based markers used in this study are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

PCR-based markers used in this study

| Marker | Class | U/L | Primer sequence | Restriction enzyme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1933 | CAPS | U | TAGACCAGAGTGAAGAGAGAAG | HaeIII |

| L | TAAAGTGAACCAACTGCGTG | |||

| P695C9-A | CAPS | U | GAAAAGAATGGACGGTAGGC | ApoI |

| L | TCCGTATCCTAGTTGTAGGC | |||

| C913A | SCAR | U | GCTTCTTAGGATTGAGGAGG | — |

| L | GCTCAGAACTACACATCACC | |||

| a | CAPS | U | TTCACAAAGCAGAGGTCGTG | DdeI |

| L | TACTGATGCAGCCTTGAACG | |||

| b | CAPS | U | CTTTACCGTGAACTGGCTAG | TaqI |

| L | ATTCTCAAGCTGTTCCCTCC | |||

| c | CAPS | U | TTCAGCCAAGACCTTCAGAG | MspI |

| L | CATCAGTGTCTTCCTTGCCC | |||

| d | SCAR | U | TCCCCTTCTTCCTCTTCACC | — |

| L | GAGCCAGAGAAAAAGCCACG | |||

| e | CAPS | U | AGTCAGGTGAGAAGTGAAGC | PshBI |

| L | GTGGGTGTGAATTGGGTGCG | |||

| P425B2-A | CAPS | U | CTGTGAAAACTGTTTAGCCC | EcoT22I |

| L | TCTCACAATCGACTGAGTGG | |||

| P25D6-A | CAPS | U | CCGCCTAATTGTTGGCTCTC | HindIII |

| L | TATAGCTTCTCCATCCCTCG | |||

| C1757S | NP | U | CTCCCCAGATGTTGTGAAGC | — |

| L | GATCCATAGCATCCGCGCAC | |||

| C8 | CAPS | U | GTCTCTGGCGAGTCATC TC | ApaI |

| L | CTTCACACGCGACATTAG C |

U and L indicate upper and lower primer, respectively. NP indicates nonpolymorphism.

DNA marker analysis:

For RFLP analysis, all probes used in this study were selected from a high-density rice genetic linkage map including 3267 markers (http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/publicdata/geneticmap2000/index.html). All procedures for DNA extraction, DNA digestion by restriction enzymes, electrophoresis, and Southern blotting have been described previously (Kurata et al. 1994). Southern hybridization and detection were performed according to the protocols of the ECL nucleic acid labeling and detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK). PCR amplification used 35 cycles of 94° for 1 min, 60° for 2 min, and 72° for 3 min. CAPS markers were digested with the respective enzyme (Table 2), and all PCR-based markers were separated on 3% (w/v) agarose gel and were visualized with ethidium bromide.

In vitro assay for CPD photolyase:

Photolyase activity in vitro was measured according to Hada et al. (2003). Seedlings were grown with a 16-hr photoperiod, day/night temperature of 28°/22° in a growth cabinet (Koitotron type KG, Koito). The third fully expanded leaves of 14-day-old seedlings (0.1 g fresh weight) were homogenized in 400 μl 80 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 5 mm EDTA, 2 mm DTT, 0.2 mg m−1 BSA, and 25% glycerol. The homogenate was centrifuged for 15 min at 4° and 20,000 × g, and the supernatant was desalted by passage through a Bio-Gel P6DG spin-column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The desalted supernatant was used as the extract for the in vitro assay for CPD photolyase. The soluble protein content was determined by the method of Bradford (1976) and adjusted to 200 μg.

λDNA (50 μg ml−1 in 0.1× TE buffer) was UV irradiated (10 J m−2, 254 nm), inducing ∼100 CPDs Mb−1. The DNA was diluted with an equal volume of 2× reaction buffer [1× reaction buffer = 40 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), 5 mm EDTA, 2 mm DTT, 0.2 mg ml−1 BSA, 80 mm NaCl] and then mixed with extract at a ratio of nine parts substrate solution to one part extract (v/v). All manipulations were performed under dim red light to minimize uncontrolled photorepair. The mixture was incubated in the dark for 15 min at 30° for the formation of photolyase-CPD complexes. Aliquots (15 μl) were incubated at 30° in the dark or in the presence of photoreactivating light from four blue fluorescent tubes (20B-F; Toshiba) at a distance of 20 cm. CPD levels were determined by adding 15 μl 2× UV endonuclease buffer [1× UV endonuclease buffer = 30 mm Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 40 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA] to each reaction mixture, and the mixture was divided into two parts. One microliter of Micrococcus luteus UV endonuclease (Carrier and Setlow 1970) was added to one part, and the mixture was incubated at 37° for 1 hr. The other part was incubated without UV endonuclease. The DNA was then denatured by the addition of alkaline stop mixture.

The number of CPDs in substrate DNA was measured with a DNA damage analysis system made by Tohoku Electric (Miyagi, Japan) (Hidema and Kumagai 1998). The CPD frequency was expressed in units of CPD per megabase.

Genetic complementation analysis and development of UV-hyperresistant plant:

The 9-kb PstI genomic fragment containing the Nipponbare CPD photolyase gene (N-PstI) (Figure 2D) was subcloned into binary vector pPZP2H-lac (Fuse et al. 2001). We also subcloned an 8-kb Nipponbare genomic fragment (60B04) (Figure 2D) derived from a shotgun clone to analyze the sequence of the PAC clone P0025D06. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation was used for transformation (Toki 1997). Subclones of N-PstI and 60B04 were transformed into Agrobacterium strain EHA101 and then infected into the callus of NIL(qUVR-10) or line RS24-13 (Table 1). Plants regenerated from hygromycin-resistant calluses (T0 plants) were grown in an isolated greenhouse. Self-pollinated plants of each T0 plant (T1) were grown, and T2 lines were examined for CPD photorepair activity under UVB irradiation. The copy number of the transformed fragment was evaluated by Southern hybridization and PCR products amplified by CAPS markers “c” and “d” were used as probes. Four T0 plants carrying a single copy of the transgene and two plants carrying multiple copies of the Nipponbare CPD photolyase gene (T0-14 and -22) were selected from 150 T0 plants. Self-pollinated progeny of these selected plants (T1) were analyzed by all designed CAPS markers in the transformed fragment to determine the presence or absence of the gene in each plant. To evaluate the UVB resistance of each T1 plant carrying multiple copies of the transgene, T1 plants were grown under 1.3 W m−2 UVB radiation for 3 weeks, and their phenotypes were observed. After that, these T1 plants were maintained without UVB radiation for 45 days to recover UV-induced damage so we could analyze the accumulation of CPD photolyase mRNA. We selected T2 plants homozygous for the transgene from the segregation pattern of the CAPS marker. For analysis of UVB resistance of T2-22-9, 20 seeds of each line were sown and the fresh weights of the aerial parts of the 1.3 W m−2 UVB-irradiated and unirradiated plants were measured 3 weeks after germination. At the same time, we observed necrotic lesion on leaves of UVB-irradiated plants and assayed in vitro photorepair activity in unirradiated plants. Transgenic lines used in this study are summarized in Table 3.

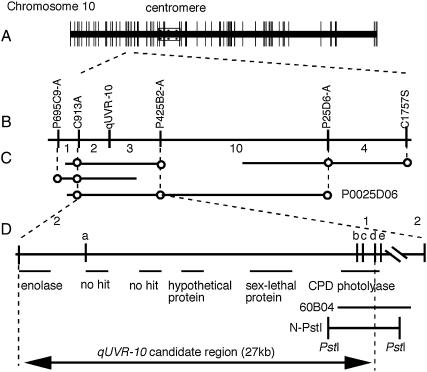

Figure 2.

High-resolution genetic and physical map of the qUVR-10 region on chromosome 10. (A) Framework RFLP linkage map constructed from the F2 population of Nipponbare and Kasalath (Harushima et al. 1998). (B) Genetic linkage map showing the relative position of qUVR-10. The number of recombinant plants is indicated between markers. (C) Nipponbare PAC clone spanning the qUVR-10 region. A circle indicates the existence of a sequence corresponding to the DNA marker. (D) Detailed genetic and physical map of the qUVR-10 region. Vertical bars indicate the positions of CAPS markers. Horizontal lines indicate the region of the predicted gene. 60B04 (8 kb) and N-PstI (9 kb) fragments were used in the complementation test of qUVR-10.

TABLE 3.

Transgenic lines used in this study

| Transgenic line | No. of transgenes | DNA fragment | Background |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2-76-14 | Single | N-PstI | NIL(qUVR-10) |

| T0-14 | Multi | N-PstI | NIL(qUVR-10) |

| T0-22 | Multi | 60B04 | RS24-13 |

| T2-22-9 | Multi | 60B04 | RS24-13 |

Genomic sequence of Kasalath CPD photolyase gene:

A Kasalath BAC library was used (Baba et al. 2000). We selected a clone containing a CPD photolyase gene by using flanking markers. The 9-kb PstI fragment covering CPD photolyase (corresponding to the N-PstI fragment in Nipponbare) was subcloned into the PstI site of pUC19. The shotgun sequencing strategy was used to obtain sequence data of the fragment. The clone was fragmented by ultrasonication and the ends of each piece were blunt ended by using a DNA blunting kit (Takara, Shiga, Japan). After electrophoresis in agarose gels, fractions corresponding to 500–1000 bp were cut out, and the eluted DNA fragment was inserted into the SmaI site of pUC19. Sequencing was performed with an automated fluorescent laser sequencer (ABI3100) and a Big Dye Primer Cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The sequence data of each fragment were assembled with Sequencher ver. 3.11 software (Hitachi Software, Yokohama, Japan) to make a contiguous nucleotide sequence.

RT-PCR assay:

Seedlings were grown for a 16-hr photoperiod, with a day/night temperature of 28°/22° in a growth cabinet (Koitotron type KG, Koito). The third fully expanded leaves of 14-day-old seedlings were sampled and stored at −80°. Total RNA was extracted by using an SDS-phenol method. Total RNA (2 μg) was primed with dT18 primer in a first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The first-strand cDNA was used as a template, and amplification was performed for 32 PCR cycles (1 min at 94°, 2 min at 60°, 3 min at 72°) for CPD photolyase or for 25 PCR cycles (45 sec at 95°, 45 sec at 63°, 60 sec at 72°) for the actin control. The primers for the transcripts of the CPD photolyase gene were the same as for the CAPS marker “c” in Table 2. Actin primers were 5′-TCCATCTTGGCATCTCTCAG-3′ and 5′-GTACCCGCATCAGGCATCTG-3′. RT-PCR assay was performed at least twice for each sample.

RESULTS

Development of nearly isogenic line of qUVR-10:

qUVR-10 was roughly mapped on the short arm of chromosome 10 by using 198 F2 plants (Ueda et al. 2004). To verify the effect of the Kasalath allele of qUVR-10, we produced a nearly isogenic line (NIL) NIL(qUVR-10) in which a chromosomal segment including qUVR-10 of Kasalath was substituted into the Nipponbare genetic background (Figure 1A). NIL(qUVR-10) showed a large number of necrotic lesions on the leaves after 3 weeks of 1.0 W m−2 UVB radiation, as did Kasalath. In contrast, Nipponbare showed no, or few, necrotic lesions (Figure 1B). This result confirmed that plants with the Kasalath allele at qUVR-10 are more sensitive than those with the Nipponbare allele.

High-resolution mapping of qUVR-10:

To delimit the candidate genomic region of qUVR-10, we made a high-resolution linkage map using 1850 F2 plants. Using CAPS markers R1933 and C8 (http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/publicdata/caps/index.html), we selected 231 plants in which recombination occurred in the vicinity of qUVR-10. Genotype class at qUVR-10 was determined by progeny testing. qUVR-10 was located between RFLP markers C913A and C1757S (Figure 2A). We screened a PAC library of the Nipponbare genome by using C913A and C1757S. PAC end-fragments were converted to genetic markers and used for linkage analysis (P695C9-A, P425B2-A, and P25D6-A). qUVR-10 was located between C913A and P425B2-A. The PAC clone P0025D06 contained the qUVR-10 candidate region (Figure 2B).

We also developed some CAPS and sequence characterized amplified region (SCAR) markers by using the nucleotide sequence of P0025D06 to define the region of qUVR-10 more precisely. The candidate region of qUVR-10 was finally delimited to a <27-kb region between SCAR markers C913A and “d.” The computer program Rice GAAS (http://RiceGAAS.dna.affrc.go.jp/) predicted six open reading frames (ORFs) in the candidate region (Figure 2C). Among them, we found a CPD photolyase gene that had already been cloned (Hirouchi et al. 2003). CPD photolyase is an enzyme that efficiently removes UV-induced CPDs from DNA in a light-dependent manner. Thus, we analyzed this gene as the positional candidate of qUVR-10. Database search and genomic Southern hybridization analysis indicated that the CPD photolyase gene is a single copy in the rice genome (data not shown).

qUVR-10 alters CPD photorepair efficiency:

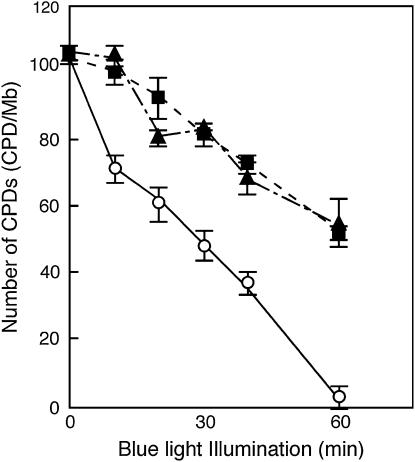

We measured in vitro CPD photorepair activity in Nipponbare, Kasalath, and NIL(qUVR-10). All CPDs were removed in Nipponbare, but half remained in Kasalath and NIL(qUVR-10) after a 60-min illumination with blue (photoreactivating) light (Figure 3). This result clearly indicates that the photorepair activity in Nipponbare was higher than that in Kasalath and NIL(qUVR-10). We also analyzed CPD photorepair activity in the plants in which recombination occurred in the regions flanking qUVR-10. The genomic region responsible for the photorepair was the same as that of qUVR-10 (data not shown). Therefore the CPD photolyase gene was the likely candidate for qUVR-10.

Figure 3.

In vitro activity of CPD photorepair in Nipponbare (open circles), Kasalath (solid squares), and NIL(qUVR-10) (solid triangles). The number of CPDs in the substrate was measured at indicated times. Points represent means of at least three experiments; vertical bars represent standard errors.

qUVR-10 encodes CPD photolyase:

To verify the function of the CPD photolyase gene, we introduced Nipponbare genomic fragments (N-PstI or 60B04) (Figure 2D) into NIL(qUVR-10). Four T0 plants carrying a single copy of the transgene were selected from 150 T0 plants. All four T2 lines derived from these T0 plants (carrying N-PstI or 60B04) showed the same UVB resistance level as Nipponbare (occurrence of necrotic lesions), whereas NIL(qUVR-10) with the empty vector showed the sensitive phenotype. Thus, we concluded that qUVR-10 encodes CPD photolyase.

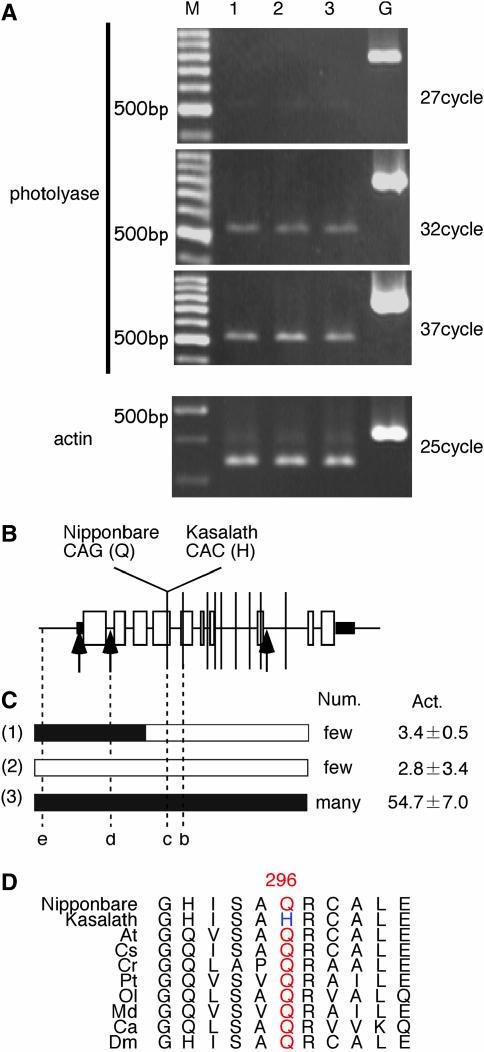

Molecular origin of allelic difference in qUVR-10:

Under the PCR condition used (see materials and methods), the amount of RT-PCR products was proportional to the PCR cycle over a range of 27–37 cycles (Figure 4A) and we used 32 cycles for further expression analysis of CPD photolyase gene. Expression levels of CPD photolyase transcripts in Nipponbare, NIL(qUVR-10), and Kasalath were almost the same (Figure 4A). We compared the genomic sequence of the CPD photolyase gene in Kasalath with the corresponding Nipponbare sequence. Many sequence variations were found in the promoter region (data not shown). We also found six single-base substitutions, a 12-base insert, a 2-base insert in the Kasalath introns, a 3-base insert in the Kasalath 5′-untranslated region (UTR), and three single-base substitutions in the Kasalath exons. Of the three single-base substitutions in the coding regions, two were synonymous and one caused an amino acid change: Glu-296 (CAG) in Nipponbare to His-296 (CAC) in Kasalath (underlined nucleotide represents single-base substitution in photolyase gene) (Figure 4B). In the process of delimitation of the qUVR-10 locus, we found an informative plant with a recombination breakpoint in the CPD photolyase gene (line RS24-23). The region covering the promoter, the 5′-UTR, and the first exon were homozygous for the Kasalath allele, and the downstream region was homozygous for the Nipponbare allele (Figure 4C). The plant showed the same phenotype as Nipponbare. We assayed the CPD photorepair ability of line RS24-23, Nipponbare, and NIL(qUVR-10) in vitro. After a 60-min blue-light exposure, all CPDs were removed in extracts of Nipponbare and RS24-23, but ∼50% remained in that of NIL(qUVR-10) (Figure 4C). On the other hand, the level of CPD photolyase transcription did not show significant difference among these three lines (data not shown). Hence, the allelic difference between Nipponbare and Kasalath qUVR-10 is caused by a single-base substitution in exon 4. This glutamine residue in exon 4 is conserved among other higher eukaryotic CPD photolyases (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

CPD photolyase gene in Nipponbare and Kasalath. (A) Calibration of RT-PCR assay and accumulation of CPD photolyase mRNA in (1) Nipponbare, (2) NIL(qUVR-10), and (3) Kasalath. M, 100-bp ladder DNA molecular weight marker. G, genomic DNA control. Actin primers were used in the control amplification. (B) Comparison of the genomic sequences of the Nipponbare and Kasalath CPD photolyase gene. Boxes indicate ORFs. Thick horizontal lines indicate 5′- and 3′-UTRs. Vertical lines represent single-base substitutions between Nipponbare and Kasalath. Arrows indicate insertions. (C) Graphical genotype of the CPD photolyase region, necrotic lesion after UVB radiation, and activity of CPD photorepair in (1) RS24-23, (2) Nipponbare, and (3) NIL(qUVR-10). Solid and open regions represent segments of the chromosome derived from Kasalath and Nipponbare, respectively. b–e indicate CAPS and SCAR marker developed in CPD photolyase gene (Table 2). Num., the number of necrotic lesions. In vitro activity of photolyase (Act.) is indicated by the number of CPDs in substrate (mean ± standard error) after a 60-min blue-light illumination. The starting number was 103.2 ± 2.6 CPD Mb−1 before blue-light exposure. (D) Alignment of the amino acid sequence of Nipponbare and Kasalath CPD photolyase around the 296th residue with corresponding sequences of class II photolyases from various organisms. At, A. thaliana; Cs, C. sativus; Cr, C. reinhardtii; Pt, Potorous tridactylus; Ol, Oryzias latipes; Md, Monodelphis domestica; Ca, Carassius auratus; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster.

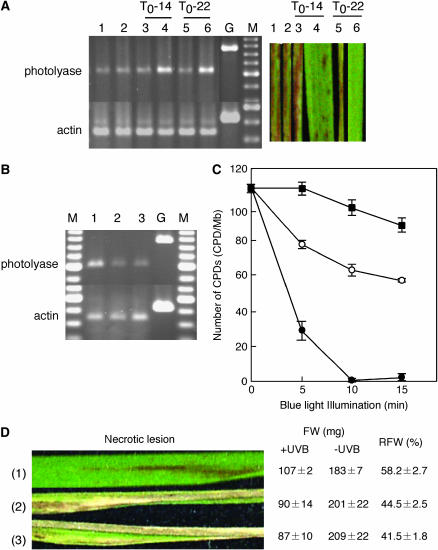

Overexpression of the CPD photolyase gene improves UVB resistance in transgenic rice:

In the process of complementation analysis, we found two T0 plants carrying multiple copies of the Nipponbare CPD photolyase gene: T0-14 [in the NIL(qUVR-10) genetic background] and T0-22 (in the RS24-13 genetic background). T1 plants derived from T0-14 and -22 were grown under 1.3 W m−2 UVB radiation for 3 weeks. The plants with increased levels of CPD photolyase transcripts showed a more UV-resistant phenotype (Figure 5A). Because T1 plants derived from T0-14 were sterile, we used plants derived from T0-22 for further analysis. T0-22 carried six or seven tandemly transformed copies of the Nipponbare CPD photolyase gene (60B04 fragment) in the RS24-13 genetic background. We selected line T2-22-9, which was homozygous for the clustered transgenes. Higher levels of CPD photolyase transcripts (Figure 5B) and CPD photorepair activity (Figure 5C) were recorded in T2-22-9. After 3 weeks of 1.3 W m−2 UVB radiation, T2-22-9 leaves showed no, or few, necrotic legions, and a small retardation of growth rate. In contrast, both RS24-13 with an empty vector and RS24-12 showed a large number of necrotic lesions, correlated with a large retardation in growth (Figure 5D). These results suggest that a higher level of UVB resistance can be achieved by increasing the production level of CPD photolyase.

Figure 5.

UV-hyperresistant plant. (A) Accumulation of CPD photolyase mRNAs and UVB-induced necrotic lesions after 3 weeks of UVB radiation at 1.3 W m−2. (1) RS24-12, (2) RS24-13 with empty vector, (3 and 4) T1 plants derived from T0-14, (5 and 6) T1 plants derived from T0-22. G, Genomic DNA used as an amplification control. M, a 100-bp ladder marker used as a size standard. Actin primers were used in the control amplification. (B) Accumulation of CPD photolyase mRNA in (1) T2-22-9, (2) RS24-12, and (3) RS24-13 with empty vector. (C) In vitro activity of CPD photorepair in T2-22-9 (solid circles), Nipponbare (open circles), and RS24-13 with empty vector (solid squares). The number of CPDs in substrate was measured at the indicated time. Each point represents the mean of at least three experiments; vertical bars represent standard errors. (D) Necrotic lesions on leaves, fresh weight (FW) of UVB-irradiated plants (+UVB) and unirradiated plants (−UVB), and ratio of fresh weight (RFW) of UVB-irradiated plants to that of unirradiated plants after 3 weeks of UVB radiation at 1.3 W m−2. Values are mean ± standard deviation. (1) T2-22-9, (2) RS24-12, and (3) RS24-13 with empty vector.

DISCUSSION

Map-based cloning of qUVR-10:

Three QTL controlling UVB resistance were detected by QTL analysis of backcross inbred lines (BILs) derived from a cross between Nipponbare and Kasalath (Sato et al. 2003). In this article, we demonstrate that a major QTL for UVB resistance on chromosome 10, qUVR-10, encodes a CPD photolyase. To our knowledge, this is the first example of map-based cloning of a QTL controlling resistance (tolerance) to an environmental stress in rice. Mapping of a gene responsible for naturally occurring variation is more difficult than that of a gene for laboratory-induced mutation because of multigenic control of, and environmental effects on, the phenotype (Koornneef et al. 2004). To avoid these problems, we used advanced backcross progeny (Yano 2001; Lin et al. 2003; Ueda et al. 2004) as a mapping population and advanced progeny testing of F4 lines for linkage analysis (Ueda et al. 2004). In this study, the candidate region of qUVR-10 was delimited to a <27-kb region by using 1850 plants from a segregating population, and we found many polymorphisms (data not shown). We proved that qUVR-10 encodes CPD photolyase by a complementation test using transformation of a single copy of the genomic fragment covering the CPD photolyase gene (Figure 1B). By comparing the genomic sequences of Nipponbare and Kasalath, we found polymorphisms in the promoter region (data not shown), 5′-UTR, introns, and exons (Figure 4B). Although introns play an important role in gene expression (Rose 2002, 2004), the level of CPD photolyase transcripts was almost the same in Nipponbare and Kasalath (Figure 4A), and so sequence variations in introns did not affect the CPD photolyase transcript level. In addition, analysis of the plant with a recombination in the CPD photolyase gene showed that sequence variations in the promoter region and the 5′-UTR were not associated with the phenotypic variation (Figure 4C). As described in the results, a single nonsynonymous substitution in the Kasalath qUVR-10 allele appears to cause reduced CPD photolyase activity and the UVB-sensitive phenotype.

Naturally occurring variation in rice CPD photolyase gene:

An amino acid change at position 296 in CPD photolyase seems to be the molecular origin of the phenotypic variation caused by qUVR-10. Comparison of deduced amino acid sequences among higher eukaryotic CPD photolyases showed that the Glu-296 (296Q) of Nipponbare is conserved, whereas the His-296 (296H) of Kasalath is not (Figure 4D). Thus, we consider that 296Q-type CPD photolyase is the original and that the amino acid change from 296Q to 296H has occurred within rice. Although the activity of the 296H-type photolyase is low compared with that of the 296Q-type (Figure 3), seedlings of Kasalath and NIL(qUVR-10) showed no necrotic lesions under field conditions in Japan (data not shown). This means that the photorepair activity of Kasalath suffices to eliminate the CPDs induced by the level of UVB radiation in Japan. Thus, rice varieties with 296H-type photolyase would not be eliminated by natural or human selection.

The difference in CPD photorepair activity between the japonica cultivar Sasanishiki (UVB resistant) and Norin 1 (UVB sensitive) depends on an amino acid change at position 126 of CPD photolyase from Gln (Sasanishiki) to Arg (Norin1) (Teranishi et al. 2004). The deduced amino acid sequence of Nipponbare CPD photolyase is identical to that of Norin 1 CPD photolyase. This suggests that at least three variations of CPD photolyase are found in rice: Nipponbare (Norin 1) type (126R, 296Q), Sasanishiki type (126Q, 296Q), and Kasalath type (126R, 296H). It is well known that the CPD photolyase activity of Norin 1 is lower than that of Sasanishiki (Hidema et al. 1997, 2000; Teranishi et al. 2004). Hence, the activity of CPD photolyase seems to decrease in the order Sasanishiki > Nipponbare (Norin 1) > Kasalath.

Development of UVB-hyperresistant plant:

It is possible that UVB in sunshine can restrict yield and growth, especially in indica cultivars. It would be interesting to compare the effects of UVB on the yield and growth of a UV-sensitive indica cultivar with those of a plant with an introduced 296Q-type CPD photolyase in an indica genetic background under field conditions in tropical areas. DNA markers developed around or in the CPD photolyase gene (Figure 2, Table 2) will be useful tools for producing this material.

The depletion of the stratospheric ozone layer increases the amount of UVB radiation in sunshine (McKenzie et al. 1999). The growth and yield of rice might be reduced by further increases in UVB radiation. Therefore we should produce UV-resistant plants. To do so, we can use mutagenesis by physical, chemical, or biological (transposon or T-DNA insertion) mutagens. Several Arabidopsis mutants that are more UVB resistant than the wild type have been described (Jin et al. 2000; Bieza and Lois 2001; Tanaka et al. 2002; Fujibe et al. 2004). Further physiological analyses of these mutants and the characterization of the genes that increase the UVB resistance will be helpful in producing UVB-resistant plants.

As NER is one of the major pathways that remove photoproducts from DNA, the genes involved in NER might be useful for improving UV resistance. Several genes involved in NER have been cloned in Arabidopsis (Gallego et al. 2000; Liu et al. 2000, 2001; Costa et al. 2001; Liu et al. 2003). To date, no one has reported the development of UV-hyperresistant plants through the use of these NER-related genes, perhaps because many proteins are induced in NER. On the other hand, we demonstrated that the overexpression of 296Q-type CPD photolyase increased the UVB resistance of UVB-sensitive rice (Figure 5, A–D), because it is likely that CPD photolyase is just an enzyme that binds to CPD, receives blue/UVA light, and removes photoproducts. Therefore, we consider that genetic engineering of plants to enhance photolyase expression will offer a shortcut for the development of UV-resistant plants.

Toward understanding of UVB resistance in rice:

We detected at least three QTL conferring resistance to UVB radiation, which explain the phenotypic difference between Nipponbare and Kasalath (Sato et al. 2003). In this study, we demonstrate that one of the QTL, qUVR-10, encodes CPD photolyase and plays an important role in UVB resistance in rice. NIL(qUVR-10) and Kasalath showed the same level of efficiency of CPD photorepair (Figure 3), and Kasalath was more UVB sensitive, showing necrotic lesions on the leaves (Figure 1B). This suggests that the other QTL are independent of CPD photorepair, but their biological functions are unknown. Our next step is to clone these QTL to understand the UVB-defense mechanism in rice.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Matsumoto for sequencing analysis of the PAC clone P0025D06, T. Fuse for technical instruction in the transformation of rice, and M. Teranishi for technical instruction in the in vitro assay for CPD photolyase activity. This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Rice Genome Project MP-1121) and by a grant-in-aid (no. 15201010) for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of Japan.

References

- Ahmad, M., J. A. Jarillo, L. J. Klimczak, L. G. Landry, T. Peng et al., 1997. An enzyme similar to animal type II photolyase mediates photoreactivation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 9: 199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba, T., S. Katagiri, H. Tanoue, R. Tanaka, Y. Chiden et al., 2000. Construction and characterization of rice genome libraries, PAC library of japonica variety Nipponbare and BAC library of indica variety Kasalath. Bull. Natl. Inst. Agrobiol. Resour. 14: 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, A. K., and J. P. Khurana, 1997. Mutants of Arabidopsis as tools to understanding the regulation of phenylpropanoid pathway and UVB protection mechanisms. Photochem. Photobiol. 65: 765–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieza, K., and R. Lois, 2001. An Arabidopsis mutant tolerant to lethal ultraviolet-B levels shows constitutively elevated accumulation of flavonoids and other phenolics. Plant Physiol. 126: 1105–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M., 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biol. 47: 75–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt, A. B., 1999. Molecular genetics of DNA repair in higher plants. Trends Plant Sci. 4: 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, M. M., 1971. Solar UV irradiation and the growth and development of higher plants, pp. 131–177 in Photophysiology, Vol. 6, edited by A. C. Glese. Academic Press, New York.

- Carrier, W. L., and R. B. Setlow, 1970. Endonuclease from Micrococcus luteus which has activity toward ultraviolet-irradiation deoxyribonucleic acid: purification and properties. J. Bacteriol. 102: 178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, R. M. A., P. G. Morgante, C. M. Berra, M. Nakabashi, D. Bruneau et al., 2001. The participation of AtXPB1, the XPB/RAD25 homologue gene from Arabidopsis thaliana, in DNA repair and plant development. Plant J. 28: 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujibe, T., H. Saji, K. Arakawa, N. Yabe, Y. Takeuchi et al., 2004. A methyl viologen-resistant mutant of Arabidopsis, which is allelic to ozone-sensitive rcd1, is tolerant to supplemental ultraviolet-B irradiation. Plant Physiol. 134: 275–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuse, T., T. Sasaki and M. Yano, 2001. Ti-plasmid vectors useful for functional analysis of rice genes. Plant Biotechnol. 18: 219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, F., O. Fleck, A. Li, J. Wyrzykowska and B. Tinland, 2000. AtRAD1, a plant homologue of human and yeast nucleotide excision repair endonucleases, is involved in dark repair of UV damages and recombination. Plant J. 21: 507–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hada, H., J. Hidema, M. Maekawa and T. Kumagai, 2003. Higher amount of anthocyanins and UV-absorbing compounds effectively lowered CPD photorepair in purple rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 26: 1691–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Harushima, Y., M. Yano, A. Shomura, M. Sato, M. Shimano et al., 1998. A high-density rice genetic linkage map with 2275 markers using a single F2 population. Genetics 148: 479–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidema, J., and T. Kumagai, 1998. UVB-induced cyclobutyl pyrimidine dimer and photorepair with progress of growth and leaf age in rice. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B, Biol. 52: 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hidema, J., H. S. Kang and T. Kumagai, 1996. Differences in the sensitivity to UVB radiation of two cultivars of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Physiol. 37: 742–747. [Google Scholar]

- Hidema, J., T. Kumagai, J. C. Sutherland and B. M. Sutherland, 1997. Ultraviolet B-sensitive rice cultivar deficient in cyclobutyl pyrimidine dimer repair. Plant Physiol. 113: 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidema, J., T. Kumagai and B. M. Sutherland, 2000. UV radiation-sensitive Norin 1 rice contains defective cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer photolyase. Plant Cell 12: 1569–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirouchi, T., S. Nakajima, T. Najrana, M. Tanaka, T. Matsunaga et al., 2003. A gene for a class II DNA photolyase from Oryza sativa: cloning of the cDNA by dilution-amplification. Mol. Gen. Genet. 269: 508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isegawa, Y., J. Sheng, Y. Sokawa, K. Yamanishi, O. Nakagomi et al., 1992. Selective amplification of cDNA sequence from total RNA by cassette-ligation mediated polymerase chain reaction (PCR): application to sequencing 6.5 kb genome segment of hantavirus strain B-1. Mol. Cell. Probes 6: 467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C-Z., J. Yee, D. L. Mitchell and A. B. Britt, 1997. Photorepair mutants of Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 7441–7445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H., E. Cominelli, P. Bailey, A. Parr, F. Mehrtens et al., 2000. Transcriptional repression by AtMYB4 controls production of UV-protecting sunscreen in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 19: 6150–6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai, S., R. Kikuno, H. Toh, H. Ryo and T. Todo, 1997. Molecular evolution of the photolyase-blue-light photoreceptor family. J. Mol. Evol. 45: 535–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef, M., C. Alonso-Blanco and D. Vreugdenhil, 2004. Naturally occurring genetic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55: 141–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata, N., Y. Nagamura, K. Yamamoto, Y. Harushima, N. Sue et al., 1994. A 300 kilobase interval genetic map of rice including 883 expressed sequences. Nat. Genet. 8: 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry, L., A. E. Stapleton, J. Lim, P. Hoffman, B. J. Jays et al., 1997. An Arabidopsis photolyase mutant is hypersensitive to ultraviolet-B radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 328–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H. X., Z. W. Liang, T. Sasaki and M. Yano, 2003. Fine mapping and characterization of quantitative trait loci Hd4 and Hd5 controlling heading date in rice. Breed. Sci. 53: 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., G. S. Hossain, M. A. Islas-Osuna, D. L. Mitchell and D. W. Mount, 2000. Repair of UV damage in plants by nucleotide excision repair: Arabidopsis UVH1 DNA repair gene is a homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad1. Plant J. 21: 519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., J. D. Hall and D. W. Mount, 2001. Arabidopsis UVH3 gene is a homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAD2 and human XGP DNA repair genes. Plant J. 26: 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., S-W. Hong, M. Escobar, E. Vierling, D. L. Mitchell et al., 2003. Arabidopsis UVH6, a homolog of human XPD and yeast RAD3 DNA repair genes, functions in DNA repair and is essential for plant growth. Plant Physiol. 132: 1405–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackerness, S. A. H., and B. R. Jordan, 1999. Changes in gene expression in response to UV-B induced stress, pp. 749–768 in Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress, edited by M. Pessarakli. Marcel Dekker, New York.

- McKenzie, R., B. Connor and G. Bodeker, 1999. Increased summertime UV radiation in New Zealand in response to ozone loss. Science 285: 1709–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menck, C. F. M., 2002. Shining a light on photolyase. Nat. Genet. 32: 338–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D. L., and R. S. Nairn, 1989. The biology of the (6–4) photoproduct. Photochem. Photobiol. 49: 805–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, S., M. Sugiyama, S. Iwai, K. Hitomi, E. Otoshi et al., 1998. Cloning and characterization of a gene (UVR3) required for photorepair of 6–4 photoproducts in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 764–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, J. L., D. W. Lang and G. D. Small, 1999. Cloning and characterization of a class II DNA photolyase from Chlamydomonas. Plant Mol. Biol. 40: 1063–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, A. B., 2002. Requirements for intron-mediated enhancement of gene expression in Arabidopsis. RNA 8: 1444–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, A. B., 2004. The effect of intron location on intron-mediated enhancement of gene expression in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 40: 744–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, A., V. T. T. Lan, Y. Hase, N. Shikazono, T. Matsunaga et al., 2003. Disruption of the AtREV3 gene causes hypersensitivity to ultraviolet B light and γ-rays in Arabidopsis: implication of the presence of a translation synthesis mechanism in plants. Plant Cell 15: 2042–2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T., and T. Kumagai, 1993. Cultivar differences in resistance to the inhibitory effect of near-UV radiation among Asian ecotype and Japanese lowland and upland cultivars of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Jpn. J. Breed. 43: 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T., and T. Kumagai, 1997. Role of UV-absorbing compound in genetic differences in the resistance to UV-B radiation in rice plants. Breed. Sci. 47: 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, T., T. Ueda, Y. Fukuta, T. Kumagai and M. Yano, 2003. Mapping of quantitative trait loci associated with ultraviolet-B resistance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 107: 1003–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strid, A., W. S. Chow and J. M. Anderson, 1994. UV-B damage and protection at the molecular level in plants. Photosyn. Res. 39: 475–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, S., N. Nakajima, H. Saji and N. Kondo, 2002. Diurnal change of cucumber CPD photolyase gene (CsPHR) expression and its physiological role in growth under UV-B irradiation. Plant Cell Physiol. 43: 342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, A., A. Sakamoto, Y. Ishigaki, O. Nikaido, G. Sun et al., 2002. An ultraviolet-B-resistant mutant with enhanced DNA repair in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 129: 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teranishi, M., Y. Iwamatsu, J. Hidema and T. Kumagai, 2004. Ultraviolet-B sensitivities in Japanese lowland rice cultivars: cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer photolyase activity and gene mutation. Plant Cell Physiol. 45: 1848–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma, F., 1999. Light and dark in chromatin repair: repair of UV-induced DNA lesion by photolyase and nucleotide excision repair. EMBO J. 18: 6585–6598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki, S., 1997. Rapid and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 15: 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T., T. Sato, H. Numa and M. Yano, 2004. Delimitation of the chromosomal region for a quantitative trait locus, qUVR-10, conferring resistance to ultraviolet-B radiation in rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108: 385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano, M., 2001. Genetic and molecular dissection of naturally occurring variations. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 4: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui, A., A. P. Eker, S. Yasuhira, H. Yajima, T. Kobayashi et al., 1994. A new class of DNA photolyase present in various organisms including aplacental mammals. EMBO J. 13: 6143–6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]