Abstract

RSC is an essential and abundant ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Here we show that the RSC components Rsc7/Npl6 and Rsc14/Ldb7 interact physically and/or functionally with Rsc3, Rsc30, and Htl1 to form a module important for a broad range of RSC functions. A strain lacking Rsc7 fails to properly assemble RSC, which confers sensitivity to temperature and to agents that cause DNA damage, microtubule depolymerization, or cell wall stress (likely via transcriptional misregulation). Cells lacking Rsc14 display sensitivity to cell wall stress and are deficient in the assembly of Rsc3 and Rsc30. Interestingly, certain rsc7Δ and rsc14Δ phenotypes are suppressed by an increased dosage of Rsc3, an essential RSC member with roles in cell wall integrity and spindle checkpoint pathways. Thus, Rsc7 and Rsc14 have different roles in the module as well as sharing physical and functional connections to Rsc3. Using a genetic array of nonessential null mutations (SGA) we identified mutations that are sick/lethal in combination with the rsc7Δ mutation, which revealed connections to a surprisingly large number of chromatin remodeling complexes and cellular processes. Taken together, we define a protein module on the RSC complex with links to a broad spectrum of cellular functions.

THE eukaryotic genome is packaged into chromatin, which can inhibit the accessibility of certain DNA binding factors to their cognate sites in vivo. However, the structure of chromatin can be altered in a regulated manner to allow factor binding (Vignali et al. 2000). Dynamic chromatin alterations help regulate processes such as transcription, replication, DNA damage repair, and recombination. A topic of considerable current interest is the characterization of factors that regulate these dynamic chromatin transitions (Jenuwein and Allis 2001; Becker and Horz 2002).

Two general classes of enzymes exist that help regulate DNA accessibility in a chromatin environment: histone modifiers and ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes (remodelers) (Narlikar et al. 2002). This work focuses on remodelers, all of which contain an ATPase subunit that is essential for the remodeling mechanism. The ATPase subunit has been proposed to function as a DNA-translocating enzyme that uses the energy of ATP-hydrolysis to mobilize nucleosomes (Saha et al. 2002; Whitehouse et al. 2003). Remodeler complexes can be divided into families with unique biochemical properties and subunit compositions. The SWI/SNF family includes the human BRM/BAF and BRG/PBAF complexes, the Drosophila BAP and PBAP complexes, and the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RSC and SWI/SNF complexes (Martens and Winston 2003; Mohrmann and Verrijzer 2005).

Remodeling complexes in the SWI/SNF family bear 8 to 15 subunits that work in cooperation with the ATPase to efficiently regulate chromatin structure. Catalytic ATPase subunits in the SWI/SNF family include Swi2/Snf2 (yeast SWI/SNF), Sth1 (yeast RSC), Brm (human BRM/BAF), and Brg1 (human BRG/PBAF or BAF) (Tsukiyama 2002; Martens and Winston 2003; Mohrmann and Verrijzer 2005). The catalytic subunit is bound to a set of “core” subunits that are highly conserved in all SWI/SNF family remodelers. Studies on human BRM and BRG core subunits, BAF170 and BAF155 (Swi3 and Rsc8 orthologs), and INI1 (a Snf5 and Sfh1 ortholog), show that core subunits contribute to the efficiency of chromatin remodeling in vitro, and with the catalytic subunit enable remodeling within twofold of wild-type activity (Phelan et al. 1999). Remodeling complexes are targeted to genes/nucleosomes by several different modes including specific interactions with transcriptional activators/repressors, by binding to modified histone tails, or (possibly) through DNA recognition. For example, the transcriptional activator Gcn4 binds RSC and SWI/SNF and is required for remodeler recruitment to a gene required for amino acid metabolism (ARG1) (Swanson et al. 2003). Furthermore, conserved protein domains that bind histone tails or DNA are present in yeast remodelers. For example, the Rsc3 subunit of RSC contains a zinc-cluster DNA binding domain and Rsc4 contains bromodomains that bind acetylated histone tails (Angus-Hill et al. 2001; Kasten et al. 2004). Certain members also serve as structural components important for assembly (Peterson et al. 1994). Thus, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes require the cooperative action of the catalytic, core, targeting, and structural components. Although roles have been ascribed to certain SWI/SNF and RSC subunits, many subunits still remain to be characterized.

RSC is a large (15 subunit), essential, and abundant remodeling complex with many cellular functions (Cairns et al. 1996). In RSC, the catalytic ATPase is essential for viability (Du et al. 1998) and is also sufficient for remodeling in vitro (Saha et al. 2002). Mutations in other RSC members also confer lethality or conditional phenotypes suggesting important in vivo functions for these attendant subunits (Cao et al. 1997; Treich and Carlson 1997; Cairns et al. 1998, 1999; Treich et al. 1998; Damelin et al. 2002; Saha et al. 2002; Bungard et al. 2004; Taneda and Kikuchi 2004). Mutations in certain RSC subunits (Sth1, Htl1, Rsc3, and Rsc4) confer cell wall defects (osmotically remedial temperature sensitivity) and link RSC to the cell wall integrity pathway likely through proper transcriptional regulation of cell wall components/regulators (Angus-Hill et al. 2001; Chai et al. 2002; Romeo et al. 2002; Kasten et al. 2004). The cell wall integrity pathway is a kinase cascade that proceeds through a central kinase, Pkc1, and helps regulate changes in cell wall composition. Mutations in components of this pathway confer cell wall defects and render cells sensitive to osmotic changes (Heinisch et al. 1999; Levin 2005). Rsc3 is an essential member of RSC with genetic links to the cell wall integrity pathway; a pkc1Δ rsc3 double mutant is nearly lethal, and certain rsc3 phenotypes can be suppressed by an increased dosage of Pkc1 (Angus-Hill et al. 2001). Interestingly, Rsc3 forms a stable heterodimer with Rsc30, a nonessential protein with functional roles distinguishable from Rsc3 (Angus-Hill et al. 2001). As mutations in other RSC components also have cell wall defects, Rsc3 likely cooperates with other RSC subunits to regulate genes involved in cell wall biogenesis (Romeo et al. 2002; Kasten et al. 2004). However, the contribution of individual subunits to the cell wall integrity pathway or other cellular processes is not well understood.

To gain further insight into the roles of individual RSC subunits, we characterized two additional RSC members, Rsc7 and Rsc14, and examined the scope of RSC function through a large-scale genetic analysis. We have shown that Rsc7 and Rsc14 have structural roles in the RSC complex and help define a fungal-specific module in RSC that includes Rsc3, Rsc30, Htl1, Rsc7, and Rsc14. Rsc7 and Rsc14 display strong genetic interactions with Rsc3 and help mediate the association of Rsc3 with the RSC complex. In addition, Rsc7 helps maintain the structural integrity of the entire RSC complex, and a strain lacking Rsc7 provided us with a tool to examine the scope of RSC function in vivo. Here, we crossed the rsc7Δ strain to a library of nonessential deletion mutants and identified a broad spectrum of null mutations that conferred growth defects in combination with the rsc7Δ. This study provides insight into RSC assembly, strengthens the connection between RSC and the cell wall integrity pathway, and identifies novel links to other signaling pathways and cellular processes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and genetic methods:

All S. cerevisiae strains are S288C derivatives. Yeast strains are listed in Table 1. Standard procedures were used for mating, sporulation, transformation, and tetrad dissection. All media were prepared as described previously (Rose et al. 1990). The null mutations for rsc7, swp82, and rsc14 were constructed using standard methods (Baudin et al. 1993; Lorenz et al. 1995) and verified by PCR analysis. All primer sequences for PCR reactions are available upon request. Alleles of rsc3, htl1, rsc9, rsc30, rsc1, and rsc2 have been described previously (Cairns et al. 1999; Angus-Hill et al. 2001; Damelin et al. 2002; Romeo et al. 2002). Genes encoding tagged derivatives of Rsc7 (including tagged truncation derivatives for Rsc7), Rsc14, and Swp82 were constructed using a one-step PCR-mediated gene-tagging procedure and verified by PCR and Western analysis (Longtine et al. 1998). A rsc7Δ strain was modified for use in synthetic genetic array analysis. Briefly, a MFA1pr-HIS3 cassette was integrated into the genomic CAN1 locus of YBC1968 (using standard procedures, Baudin et al. 1993; Lorenz et al. 1995) and confirmed by PCR analysis. The mating-type locus of this strain was then converted from MATa to MATα to generate YBC2039. All other null mutations (including mutations from the nonessential haploid deletion library) were obtained through Research Genetics (Invitrogen) and are isogenic to either BY4741 or BY4742 (Brachmann et al. 1998).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| YBC834 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 [p739b; YCP50.RSC7.13×MYC.TRP1] | This study |

| YBC818 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 trp1Δ63 lys2Δ0 SWP82.13×MYC.TRP1 | This study |

| YBC1946 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 RSC14.13MYC.his3MX6 | This study |

| YBC62 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 | Cairns lab |

| YBC63 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 | Cairns lab |

| BY4741 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Research Genetics |

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Research Genetics |

| YBC1332 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC1333 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC1333A | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 [p935;MET25pr.rsc7 248-435.13×MYC.TRP1] | This study |

| YBC76 | MATa/α his3Δ200/his3Δ200 leu2Δ1/leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ/lys2-128δ trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 ura3-52/ ura3-52 | Cairns lab |

| YBC1888 | MATa/α his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 met15Δ0/MET15 lys2Δ0/LYS2 ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 rsc14Δ∷KanMX/RSC14 | Research Genetics |

| YBC1926 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 rsc14Δ∷KanMX [p1402;pRS316.RSC14] | This study |

| YBC1927 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 rsc14Δ∷KanMX [p1402;pRS316.RSC14] | This study |

| YBC1887 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 rsc14Δ∷KanMX | Research Genetics |

| YBC2297 | MATahis3 leu2Δ ura3 trp1Δ63 lys2 Rsc14.13×MYC.His3MX6 | This study |

| YBC2281 | MATα his3 leu2Δ ura3 trp1Δ63 lys2 rsc7Δ∷LEU2 Rsc14.13×MYC.His3MX6 | This study |

| YBC939 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 rad9Δ∷Kanmx | Research Genetics |

| YBC936 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 mad1Δ∷Kanmx | Research Genetics |

| YBC1470 | MATα his3 leu2Δ0 lys2 ura3 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 mad1Δ∷KanMX [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC1944 | MATα his3 leu2Δ0 lys2 ura3 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 rad9Δ∷KanMX | This study |

| YBC1918 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 rsc14Δ∷KanMX rsc7Δ∷HIS3 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC1349 | MATα his3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 htl1Δ∷TRP1[p1127;pRS316.HTL1] | Romeo et al. (2002) |

| YBC1984 | MATalys2-128∂ leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 htl1Δ∷LEU2 [p1127.pRS316.HTL1] | This study |

| YBC1429 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 htl1Δ∷TRP1 [p1127;pRS316.HTL1] | This study |

| YBC842 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc3Δ∷HIS3 [p746;pRS315.rsc3-2] | Angus-Hill et al. (2001) |

| YBC1393 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 rsc3Δ∷HIS3 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] [p746;pRS315.rsc3-2] | This study |

| YBC906 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc3Δ∷HIS3 [p817.pRS315.rsc3-3] | Angus-Hill et al. (2001) |

| YBC1430 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 rsc3Δ∷HIS3 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] [p817;pRS315.rsc3-3] | This study |

| YBC828 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 trp1Δ63 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 ade2Δ∷hisG rsc30Δ∷LEU2 [p731;pRS316.RSC30] | Angus-Hill et al. (2001) |

| YBC1386 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2 lys2 trp1Δ63 ura3 ade2Δ∷hisG rsc7Δ∷HIS3 rsc30Δ∷LEU2 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC1156 | MATahis3 leu2Δ1 trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc9-1 | Damelin et al. (2002) |

| YBC1381 | MATahis3 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 rsc9-1[p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC849 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 trp1Δ63 ura3Δ0 met15Δ0 ade2Δ∷hisG rsc1Δ∷LEU2 | Cairns et al. (1999) |

| YBC1505 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ0 lys2 trp1Δ63 ura3 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 rsc1Δ∷LEU2 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC79 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc2Δ∷LEU2 | Cairns et al. (1999) |

| YBC1507 | MATahis3Δ200 leu2Δ1 lys2-128δ trp1Δ63 ura3-52 rsc2Δ∷LEU2 rsc7Δ∷HIS3 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC2006 | MATahis3 leu2 trp1Δ63 ura3 htl1Δ∷TRP1 rsc14Δ∷KanMX [p1127;pRS316.HTL1] | This study |

| YBC2028 [p746] | MATalys2 leu2 ura3 trp1Δ63 his3 rsc3Δ∷HIS3 rsc14Δ∷KanMX [p746;pRS315.rsc3-2] | This study |

| YBC2028 [p817-3A] | MATalys2 leu2 ura3 trp1Δ63 his3 rsc3Δ∷HIS3 rsc14Δ∷KanMX [p817.pRS315.rsc3-3] | This study |

| YBC1968 | MATalys2-128∂ leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 rsc7Δ∷LEU2 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC2039 | MATα lys2-128∂ leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 rsc7Δ∷LEU2 can1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC2014 | MATalys2-128∂ leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 rsc71-224.13Xmyc.TRP1 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC2048 | MATalys2-128∂ leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 rsc71-370.13XMYC.TRP1 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

| YBC2017 | MATalys2-128∂ leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 his3Δ200 rsc71-414.13×MYC.TRP1 [p137;YCP50.RSC7] | This study |

Plasmids:

Plasmids p137 and p136 (gifts from Pam Silver) harbor a 2.6-kb SnaBI fragment of the genomic RSC7 locus subcloned into YCP50 or YEP352, respectively. Plasmid p1310 was constructed using a XhoI–SpeI fragment bearing RSC3 that was isolated from p906 (pRS314.RSC3; Angus-Hill et al. 2001) and subcloned into pRS426. Plasmids p1401 and p1403 were constructed by cloning a 900-bp PCR product (using genomic DNA as template) containing RSC14 into pRS315 and pRS425, respectively. Plasmid p1204 (pRS426.HTL1.3×HA) was described previously (Romeo et al. 2002). Plasmids p185 (pRS426.Rsc8.3×HA) and p186 (pRS315.Rsc8.3×HA), gifts from Marian Carlson, were described previously (Treich and Carlson 1997). Plasmids p935 (MET25pr.rsc7 248-435.13×Myc.TRP1) and p936 (MET25pr.rsc7 1-435.13×Myc.TRP1) were constructed by cloning RSC7 fragments generated by PCR (using genomic DNA from YBC834) into the FB1521 plasmid (Funk et al. 2002) using XhoI and XbaI or SpeI and BamHI, respectively.

Extract preparation and immunoprecipitation analysis:

Preparation of whole cell extracts was as described previously (Cairns et al. 1999), except cells were subjected to bead beating for 2 min (three pulses) and 5 min of cooling on ice. Anti-Myc (0.5 mg/ml) or −HA (7 μg/ml) antibodies were prebound to protein G-agarose or magnetic beads, respectively. To immunoprecipitate tagged derivatives of Rsc7, Swp82, Rsc8, and Rsc14, anti-Myc beads (40 μl of a 50% slurry) or Anti-HA beads (50 μl of slurry) were incubated with 200 μg of the indicated protein extract in immunoprecipitation buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mm EDTA, 10% glycerol, 100 mm NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20] (total volume was 140 μl) at 4° for 3.5–7.5 hr. When checking RSC stability in rsc14Δ extracts, the immunoprecipitation buffer contained 250 mm NaCl (total immunoprecipitation volume was 400 μl). When checking RSC stability in rsc7Δ extracts, the total immunoprecipitation volume was 400 μl. Precipitates were recovered by centrifugation (10,600 × g for 2 min) or using a magnetic bead stand, and washed three times with immunoprecipitation buffer (250 mm NaCl). Precipitates were eluted with SDS and separated on a 7.5% acrylamide-SDS gel (with supernatants and input) and transferred to polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Standard immunoblotting and chemiluminescence detection methods were used.

Isolation and identification of Rsc7, Swp82, and Rsc14:

The purification of RSC and SWI/SNF to homogeneity was performed as described previously (Cairns et al. 1994, 1996), respectively. Rsc7, Rsc14, and Swp82 peptides were isolated, sequenced, and analyzed by mass spectrometry as previously described for other RSC and SWI/SNF subunits.

FACS analysis:

Methods used for FACS analysis were described previously (Angus-Hill et al. 2001).

Synthetic genetic array screen:

The modified rsc7Δ strain (YBC2039) was mated with the yeast haploid deletion set (BY4741) from Research Genetics (Invitrogen) (catalog no. 95401.H2) on rich solid media. Diploids were selected on synthetic complete (SC) medium containing G-418 and lacking leucine. These diploids were sporulated on solid medium and meiotic haploid MATa double-mutant progeny containing the plasmid-borne RSC7+ were isolated on SC medium containing canavanine and G-418 while lacking uracil, histidine, leucine, and arginine. Selection was based on haploid selection markers (can1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3), double-mutant selection markers (KanMX and LEU2), and a plasmid selection marker (URA3). To monitor growth of double mutants after loss of the URA3-marked RSC7+ plasmid, haploids were replica plated to haploid selection media with or without 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA). Double mutants were scored as sick/lethal by comparing growth on medium lacking 5-FOA (enabling RSC7+ retention) or with medium containing 5-FOA (enforcing RSC7+ loss).

RESULTS

Rsc7 and Swp82 are paralogs in RSC and SWI/SNF:

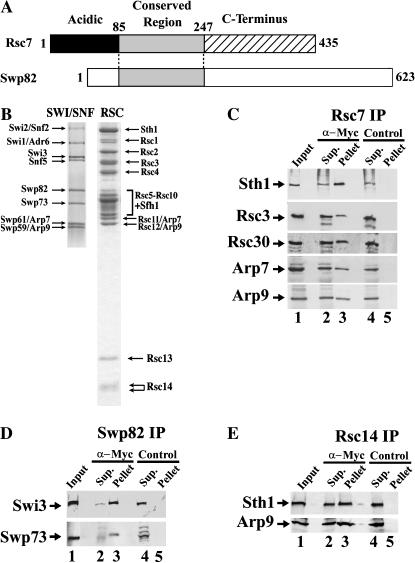

Our studies began with the identification of two paralogs in the RSC and SWI/SNF complexes, Rsc7 and Swp82. These complexes were previously purified to homogeneity from yeast cellular extracts (Figure 1B; Cairns et al. 1994, 1996). The 50-kDa RSC subunit, Rsc7 (also designated Npl6; Bossie et al. 1992) was isolated and analyzed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, mass fingerprinting, and limited Edman sequencing, which uniquely identified the open reading frame YMR091c/NPL6.

Figure 1.

Rsc7 and Swp82 are paralogs found in RSC and SWI/SNF, whereas Rsc14 is unique in RSC. (A) The three regions of Rsc7: (1) a nonconserved acidic amino terminus, (2) a region conserved in Swp82 and other fungi, and (3) a C-terminal region conserved in other fungi with low/no homology to Swp82. (B) Purified SWI/SNF and RSC. SWI/SNF was purified to homogeneity and stained with silver (Cairns et al. 1994), and RSC was purified to homogeneity and stained with Coomassie (Cairns et al. 1996). For SWI/SNF, the small components (Tfg3 and Snf11) are not shown. (C) Verification of Rsc7 association with RSC components. A Rsc7.13×Myc derivative was immunoprecipitated (from an extract derived from YBC834) with protein G-agarose beads coupled to the α-Myc antibody (labeled α-Myc), or beads alone (labeled control). Beads were washed with a wash buffer containing 250 mM NaCl, and proteins were eluted with SDS. Eluates were separated on a 7.5% acrylamide-SDS gel (input 25%, supernatant 25%, eluate/pellet 100%), transferred to a PVDF membrane, and immunoblotted with the polyclonal antibodies anti-Sth1 and anti-Arp9. (D) Verification of Swp82 association with SWI/SNF components. Association of Swp82 with SWI/SNF was determined by the methods described in C except with a Swp82.13×Myc derivative (from an extract derived from YBC818) and probing with antibodies raised against Swi3 and Swp73 (input 50%, supernatant 19%, eluate/pellet 50%). (E) Verification of Rsc14 association with RSC components. Association of Rsc14 with RSC was determined by the methods described in C except with a Rsc14.13×Myc derivative (from an extract derived from YBC1946) and probing with antibodies raised against Sth1 and Arp9 (input 25%, supernatant 25%, pellet/eluate 100%).

To verify the interaction between Rsc7 and RSC (as opposed to fortuitous copurification), we immunoprecipitated an epitope-tagged Rsc7 derivative (Rsc7.13×Myc) and tested for association with known RSC members. Rsc7.13×Myc efficiently coprecipitated other members of the RSC complex, including Sth1, Rsc3, Rsc30, Arp7, and Arp9 (Figure 1C). These interactions were stable under stringent wash conditions and confirm Rsc7 as a stable component of the RSC complex. Our findings support and extend proteomic and biochemical approaches showing Rsc7 associated with RSC members (Uetz et al. 2000; Gavin et al. 2002; Sanders et al. 2002; Baetz et al. 2004; Graumann et al. 2004) and the interaction between Rsc7 and Rsc8 (a core RSC subunit) observed in genome-wide two-hybrid studies (Uetz et al. 2000).

A proteomic strategy similar to that used for Rsc7 identification was used to identify the ∼80-kDa subunit of SWI/SNF as YFL049w/Swp82 (data not shown). An epitope-tagged Swp82 (Swp82.13×Myc) efficiently coprecipitates with Swi3 and Swp73 and remains associated even under stringent wash conditions (Figure 1D). These data support and extend proteomic approaches by others who observed Swp82 copurifying with SWI/SNF subunits (Gavin et al. 2002; Graumann et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2004).

Rsc7 and Swp82 define a new family of proteins conserved in fungi:

Using the algorithm BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990), we searched for proteins related to Rsc7. Orthologs were identified in closely related yeast of the hemiascomycete family including Candida glabrata, Ashbya gossypii, and Kluyveromyces lactis. In addition, orthologs were identified in distantly related fungal species such as Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Neurospora crassa; however, orthologs were not identified in higher eukaryotes. Importantly, a paralogous protein was identified in S. cerevisiae, Swp82 (BLAST P-value 1.36 × 10−4). In Figure 1D, we verified Swp82 as a novel member of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. Thus, Rsc7 and Swp82 are paralogous components of the RSC and SWI/SNF complexes, respectively.

On the basis of alignments with orthologs, we have separated Rsc7 into three regions: (1) an acidic amino terminus (Figure 1A; black box), (2) a conserved region (Figure 1A; shaded box), and (3) a C-terminal region (Figure 1A; hatched box). First, the amino acids 1–84 of Rsc7 are rich in aspartic and glutamic acid, but lack any significant homology with other proteins. Second, the conserved region (amino acids 85–247) is present in Rsc7 orthologs in all fungi and is thus the defining feature of all Rsc7 family members. Searches with this conserved region revealed two orthologs in the closely related hemiascomycete yeast C. glabrata, CAG60715 (BLAST P-value 4.68 × 10−4) and CAG61742 (BLAST P-value 3.65 × 10−3). Two proteins bearing the conserved region can also be identified in more distantly related fungi such as the filamentous yeast, S. pombe, and the red bread mold, N. crassa. Third, the C-terminus of Rsc7 (amino acids 248–435) is not significantly conserved between Rsc7 and Swp82. However, a search for proteins with homology to this region of Rsc7 revealed C. glabrata CAG60715 (BLAST P-value 1.71 × 10−16), S. pombe SPCC1281.05 (BLAST P-value 2.02 × 10−2), and putative Rsc7 counterparts in other fungal species. Thus, we have identified a new family of proteins in fungi related to Rsc7.

A search for proteins related to Swp82 revealed Rsc7 (BLAST P-value 2.27 × 10−4) in S. cerevisiae, proteins in hemiascomycete yeast, and proteins in more distantly related fungal species such as S. pombe and N. crassa. Similar to Rsc7, searches using the conserved region of Swp82 (Figure 1A; shaded box) revealed orthologs in C. glabrata CAG61742 (BLAST P-value 2.81 ×10−13) and CAG60715 (BLAST P-value 6.74 × 10−3) and identified orthologs in other fungal species. Furthermore, searches using the C-terminal nonconserved region of Swp82 helped to identify Swp82 counterparts in closely related hemiascomycete yeast, such as CAG61742 (BLAST P-value 1.10 × 10−34) in C. glabrata. However, unlike Rsc7 the C-terminal region of Swp82 was not conserved in more distantly related fungal species such as S. pombe and N. crassa. Taken together, Swp82 has homologs in fungi and has identifiable counterparts in closely related yeast species.

Rsc14 is a RSC component conserved in yeast:

Among the subunits identified in the initial purification of RSC to homogeneity were two species of ∼15 kDa, previously designated Rsc14 and Rsc15 (Figure 1B; Cairns et al. 1996). Mass fingerprinting and peptide sequencing identify both Rsc14 and Rsc15 as proteins encoded by the open reading frame YBL006c (also named LDB7; Corbacho et al. 2004). We suspect the faster migrating form of Rsc14 is a degradation product as the tagged Rsc14 is present only as a single species (data not shown). Therefore, the species previously designated as Rsc14 and Rsc15 will hereafter be called Rsc14.

To verify the interaction between Rsc14 and RSC, we tagged the C-terminus of Rsc14 with 13 copies of the Myc epitope (Rsc14.13×Myc). Co-immunoprecipitation experiments confirmed association between Rsc14 and other members of RSC. Indeed, Rsc14 coprecipitates with Sth1 and Arp9 and remains stably associated under stringent wash conditions (Figure 1E). Our results support recent proteomic studies revealing that Rsc14 copurifies with RSC complex members (Graumann et al. 2004).

The algorithm BLAST identified Rsc14 orthologs in closely related hemiascomycete yeast but not other higher eukaryotes or more distantly related fungal species. In C. glabrata, Rsc14 is conserved with CAG58728 (BLAST P-value 6.07 × 10−9) and also has counterparts in A. gossypii and K. lactis. Thus, we have verified Rsc14 as a RSC component, and have revealed its conservation in yeast.

Phenotypic analysis of the rsc7Δ, swp82Δ, and rsc14Δ strains:

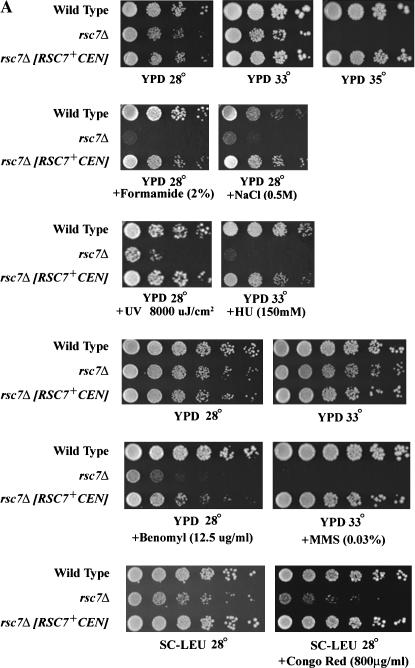

To address the in vivo functions of Rsc7, Swp82, and Rsc14 we isolated null alleles and examined their growth characteristics. The rsc7Δ haploid spores grew slowly at 28° and were inviable at 37°. Furthermore, the rsc7Δ strain displayed severe growth defects when exposed to any of an assortment of cellular stresses: NaCl (0.5 m), congo red (800 μg/ml), formamide (2%), caffeine (15 mm), ultraviolet radiation (UV; 8000 μJ/cm2), methyl methanesulfonate (MMS; 0.03%), hydroxyurea (HU; 150 mm), and benomyl (12.5%) (Figure 2A). Mutant phenotypes were complemented largely or fully by a plasmid-borne copy of RSC7+. Somewhat surprisingly, the rsc7Δ mutation did not confer a narrow range of rsc phenotypes (expected of a specific targeting subunit), but rather conferred a broad range of phenotypes representing the full spectrum of all known rsc mutations. This suggested a broad and/or general role for Rsc7 in the RSC complex.

Figure 2.

Growth ability of a rsc7Δ strain and dosage suppression by RSC3 or sorbitol. (A) Growth ability of rsc7Δ strains. Wild-type (YBC62) and rsc7Δ (YBC1332) strains were grown in liquid medium to log phase, subjected to 10-fold serial dilution (four spots per row) or 5-fold serial dilution (six spots per row), and spotted on solid medium containing the compounds indicated. rsc7Δ phenotypes were complemented by a plasmid-borne RSC7+ (p137). We note that the incomplete complementation of the benomyl phenotype by a low-copy plasmid-borne RSC7+ is likely due to lower levels of Rsc7 expression as this construct lacks the full promoter/upstream region. (B) An increased dosage of RSC3+ (p1310) partially suppresses certain rsc7Δ phenotypes. (C) Sorbitol suppresses the rsc7Δ Ts− phenotype.

To better characterize the domains of Rsc7, we made genomic truncations of the C-terminus of Rsc7 by integrating (via homologous recombination) a cassette encoding a 13×Myc tag (see materials and methods). A Rsc7 derivative lacking its C-terminus failed to assemble into the RSC complex and failed to complement rsc7Δ phenotypes, but was produced in the cell (supplemental Table 1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). To determine the extent to which Rsc7 function depends on this region we expressed a Rsc7 derivative bearing only the C-terminal region (amino acids 248–435). Surprisingly, the C-terminal region of Rsc7 fully complemented all known rsc7Δ phenotypes, showing that the conserved homology region is apparently not required for the large spectrum of Rsc7 functions examined (supplemental Table 1 at at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

The swp82Δ strain grew well under all conditions tested. Our tests included growth at 16°, 35°, and 38°; growth on glycerol (2%), galactose (2%), raffinose (2%), sucrose (2%), and ethanol (6%) (common phenotypes conferred by other swi/snf mutations); growth on media containing lower/higher than normal levels of phosphate; growth on medium lacking amino acids (except those required for auxotrophic markers); growth on rapamycin (15 nm); or growth on increased concentrations of LiCl (0.25 m), ZnSO4 (5 mm), NaCl (1.2 m), MnCl2 (6 mm), CaCl2 (200 mm), and CoCl2 (1.5 mm). Furthermore, we tested for sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation (100 μJ/cm2 × 100), 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (0.5 μg/ml), hydroxyurea (100 mm), and camptothecin (20 μg/ml) (DNA damaging agents); sensitivity to formamide (2%) and caffeine (15 mm) (cellular stress); sensitivity to sulfometuron methyl (3 μg/ml) (amino acid metabolism); sensitivity to tunicamycin (4 μg/ml), dithiothreitol (100 mm), brefeldin A (30 μg/ml), and low pH media (secretory pathway); sensitivity to 6-azauracil (35 μg/ml) (transcription elongation); and sensitivity to cycloheximide (1 μg/ml) (protein synthesis). The swp82Δ strain displayed no obvious sporulation or mating defects, and genes displaying altered expression in swi/snf mutants (including SER3) were not misregulated in a swp82Δ strain (data not shown). Finally, the swp82Δ rsc7Δ double mutant displayed phenotypes indistinguishable from rsc7Δ alone (data not shown). Therefore, the role of Swp82 in SWI/SNF remains elusive.

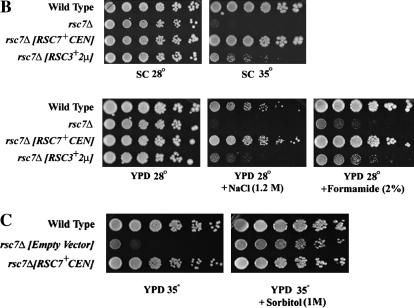

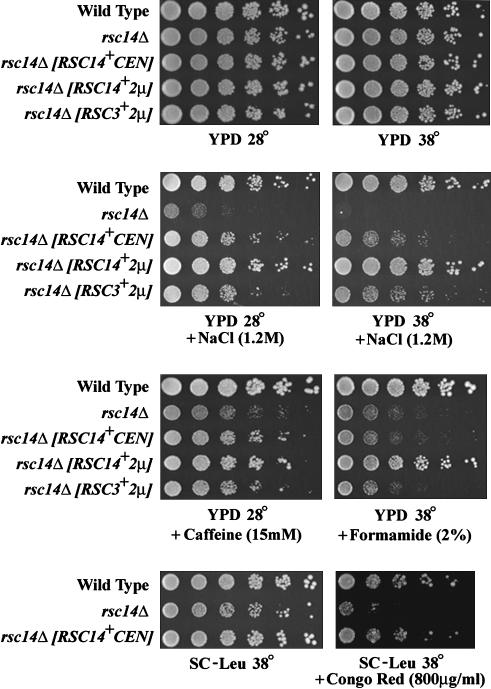

The haploid rsc14Δ strain was generally healthy, but showed clear sensitivity to NaCl (1.2 m) and caffeine (15 mm) at normal temperatures (30°) and formamide (2%) and congo red (800 μg/ml) at elevated temperatures (38°). This sensitivity could be complemented by a plasmid-borne RSC14+ (Figure 3). Thus, we have identified rsc14Δ phenotypes that connect Rsc14 to the cell wall integrity pathway and certain functions shared by Rsc3 and Rsc7.

Figure 3.

Growth ability of a rsc14Δ strain and dosage suppression by RSC3. Wild-type (YBC1895) and rsc14Δ (YBC1926) strains were grown in liquid medium to log phase, subjected to fivefold serial dilution, and spotted on media containing the compounds indicated. rsc14Δ phenotypes were complemented by plasmid-borne RSC14+ (p1401, CEN; p1403 2μ), and suppressed by a plasmid-borne RSC3+ (p1310). We note that the incomplete complementation by a low-copy plasmid-borne RSC14+ is likely due to lower levels of Rsc14 expression as this construct lacks the full promoter/upstream region. Indeed, a high-copy plasmid-borne RSC14+ fully complements the rsc14Δ phenotypes.

rsc7Δ and rsc14Δ mutations are lethal in combination with other rsc mutations:

To help identify functional relationships between RSC subunits and Rsc7 we attempted to cross the rsc7Δ strain to other rsc mutants. However, we found that strains lacking Rsc7 rapidly acquired mutations that conferred spore inviablity (revealed in subsequent mating/sporulation tests, data not shown). To circumvent this problem, rsc7Δ∷HIS3/RSC7+ heterozygous diploids bearing RSC7+ on a URA3-marked plasmid were sporulated and dissected to generate a haploid rsc7Δ strain covered by RSC7+. This strain was crossed to other rsc mutants and growth defects were determined by the ability of the haploid double mutants to lose the URA3-marked plasmid bearing RSC7+. Surprisingly, in all cases tested rsc7Δ double-mutant combinations showed lethality (Table 2). These results support a broad and/or general role for Rsc7 in promoting RSC complex function.

TABLE 2.

rsc7Δ rsc double mutants are inviable

| RSC7 allele | rsc allele | Growth at 28° on 5-FOA | Straina |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSC7 | WT | ++++ | YBC62 |

| rsc7Δ | WT | +++ | YBC1332 |

| WT | rsc14Δ | ++++ | YBC1927 |

| rsc7Δ | rsc14Δ | − | YBC1918 |

| WT | htl1Δ | ++++ | YBC1349 |

| rsc7Δ | htl1Δ | − | YBC1429 |

| WT | rsc3-2 | ++++ | YBC842 |

| rsc7Δ | rsc3-2 | − | YBC1393 |

| WT | rsc3-3 | ++++ | YBC906 |

| rsc7Δ | rsc3-3 | − | YBC1430 |

| WT | rsc30Δ | +++ | YBC828 |

| rsc7Δ | rsc30Δ | − | YBC1386 |

| WT | rsc9-1 | +++ | YBC1156 |

| rsc7Δ | rsc9-1 | − | YBC1381 |

| WT | rsc1Δ | +++ | YBC849 |

| rsc7Δ | rsc1Δ | − | YBC1505 |

| WT | rsc2Δ | +++ | YBC79 |

| rsc7Δ | rsc2Δ | − | YBC1507 |

Strains refer to the covered version bearing the RSC7+–URA3, RSC14+–URA3, or HTL1+–URA3 plasmids. Inviability (−) is determined through a lack of growth ability on media containing 5-FOA.

To test for functional relationships between Rsc14 and other members of RSC, we crossed the rsc14Δ null with other rsc mutants. Similar to the rsc7Δ strain, rsc14Δ mutants acquired mutations that conferred low spore viability. To circumvent this problem, rsc14Δ∷KanMX/RSC14+ heterozygous diploids bearing RSC14+ on a URA3-marked plasmid were sporulated and dissected to generate a haploid rsc14Δ strain covered by plasmid-borne RSC14+. This strain was crossed to other rsc mutants and growth defects were determined by the ability of the haploid double mutants to lose the URA3-marked plasmid bearing RSC14+. Similar to any observations with rsc7Δ, rsc14Δ combinations with other rsc mutations were inviable (Table 3). These results are consistent with Rsc14 conducting an essential RSC function in combination with other members of RSC.

TABLE 3.

rsc14Δ rsc mutants are inviable

| RSC14 allele | rsc allele | Growth at 28° on 5-FOA | Straina |

|---|---|---|---|

| RSC14 | WT | ++++ | YBC62 |

| rsc14Δ | WT | ++++ | YBC1927 |

| WT | htl1Δ | ++++ | YBC1984 |

| rsc14Δ | htl1Δ | − | YBC2006 |

| WT | rsc3-2 | ++++ | YBC842 |

| rsc14Δ | rsc3-2 | − | YBC2028 [p746] |

| WT | rsc3-3 | ++++ | YBC906 |

| rsc14Δ | rsc3-3 | − | YBC2028 [p817] |

Strains refer to the covered version bearing the RSC7+–URA3, RSC14+–URA3, or HTL1+–URA3 plasmids. Inviability (−) is determined through a lack of growth ability on media containing 5-FOA.

RSC structural integrity requires Rsc7 and Rsc14:

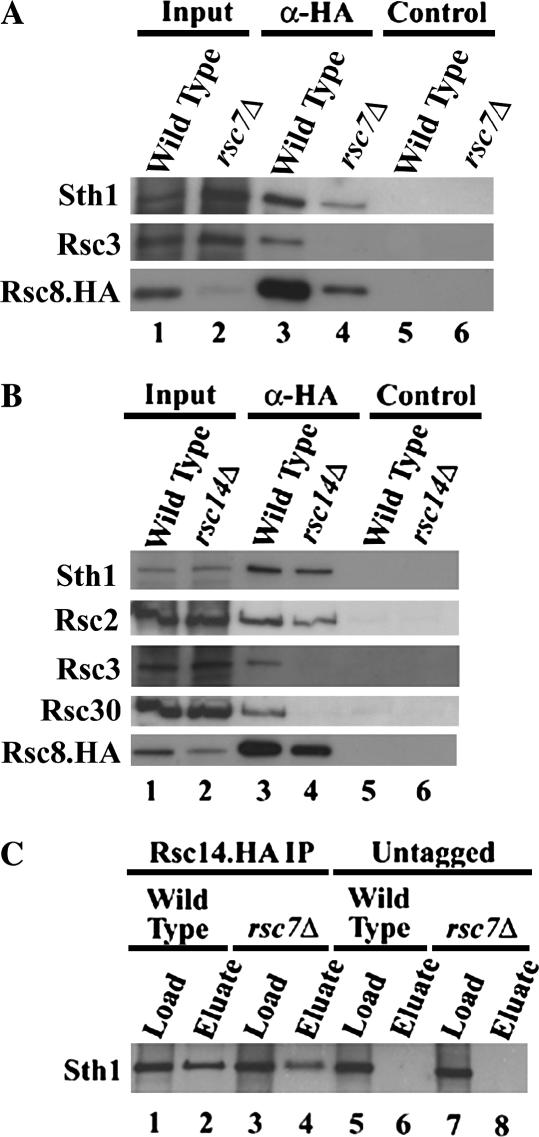

The breadth of phenotypes conferred by rsc7Δ raised the possibility that RSC complexes lacking Rsc7 might fail to assemble properly, impairing all RSC functions. To test this, we performed co-immunoprecipitation studies with a strain expressing an HA-tagged Rsc8 derivative (Rsc8.3×HA). Rsc8 is an essential subunit of RSC that interacts with several other RSC components (Rsc6, Sth1, and Htl1) and likely forms a structural scaffold for the RSC complex (Treich and Carlson 1997; Treich et al. 1998; Lu et al. 2003).We found Rsc8 protein levels greatly reduced in a rsc7Δ strain confirming that Rsc7 contributes to the general assembly of the RSC complex. Importantly, Rsc3 association with Rsc8.3×HA was severely reduced in a rsc7Δ strain (Figure 4A). Taken together, these results confirm Rsc7 is a structural component required for full assembly of the RSC complex, providing a basis for the broad range of phenotypes displayed by the rsc7Δ strain.

Figure 4.

Rsc7 and Rsc14 are structural components of RSC. (A) Loss of Rsc7 leads to Rsc8 instability and failure of Rsc8 to associate with other RSC components. Extracts were derived from wild-type (YBC62) and rsc7Δ (YBC1332) strains harboring the plasmid p186 (encoding Rsc8.3×HA). Rsc8.3×HA protein was immunopreciptated using an HA antibody (α-HA) coupled to magnetic beads or beads alone (control). Beads were washed and eluates were separated on a 7.5% acrylamide-SDS gel, immunoblotted to PVDF, and probed with anti-Rsc3, -Sth1 or -HA antibodies (input 40%, eluate/pellet 100%). (B) Loss of Rsc14 leads to failure of Rsc8 to associate with Rsc3 and Rsc30. Extracts were derived from wild-type (YBC1894) and rsc14Δ (YBC1928) strains harboring the plasmid p186 (encoded Rsc8.3×HA). Rsc8.3×HA protein was immunopreciptated using an HA antibody (α-HA) coupled to magnetic beads, or beads alone (control). Precipitated proteins were analyzed by the methods used in A (input 25%, eluate/pellet 100%). (C) Rsc14 associates with Sth1 in a rsc7Δ strain. Extracts were derived from wild-type (YBC2297) and rsc7Δ (YBC2281) strains. Rsc14.3×HA protein was immunoprecipitated using an HA antibody coupled to protein G agarose. Precipitated proteins were analyzed by the methods used in A and B (input 10%, beads 100%).

The rsc14Δ strain also exhibits sensitivity to NaCl, caffeine, and formamide (at elevated temperatures), all phenotypes shared by rsc7 and rsc3 mutants. These results suggested that Rsc14 might be physically and/or functionally linked to Rsc7 and Rsc3, a notion supported by double-mutant phenotypes; rsc7Δ rsc14Δ or rsc3 rsc14Δ combinations were inviable (Tables 2 and 3). To test whether Rsc14 has a structural role in linking Rsc3 to RSC, we performed co-immunoprecipitation studies with a strain expressing an HA-tagged Rsc8 derivative (Rsc8.3×HA). In a rsc14Δ strain, Rsc8.3×HA coprecipitates with Sth1 normally, whereas its association with Rsc3 and Rsc30 is severely diminished (Figure 4B). Previous work has established that Rsc3 and Rsc30 form a stable heterodimer (Angus-Hill et al. 2001) that would predict their co-loss. Together, our data support a model where Rsc7 and Rsc14 help the Rsc3/30 heterodimer assemble into RSC.

We next tested whether Rsc7 also promotes Rsc14 association with RSC. Here, we immunoprecipitated an HA-tagged Rsc14 derivative (Rsc14.3×HA) in a rsc7Δ strain, which showed full association with Sth1 (Figure 4C). Taken together, we show that Rsc7 and Rsc14 promote Rsc3 association with RSC, whereas Rsc7 is not required for Rsc14 to assemble into RSC.

Rsc7 and Rsc14 are physically and functionally linked to Rsc3:

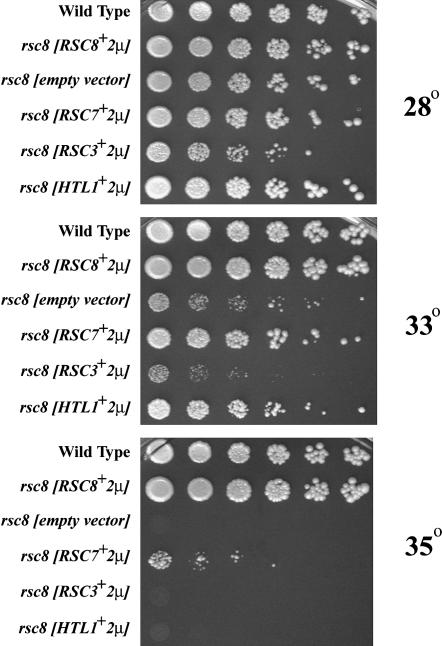

We further tested for functional and/or physical relationships among Rsc7, Rsc14, and Rsc3 by testing for dosage suppression. First, we tested whether an increased dosage of Rsc3 could suppress rsc7Δ phenotypes. We found that plasmid-borne RSC3 in high copy partially suppressed rsc7Δ sensitivity to temperature, osmotic stress, and formamide, whereas increased dosage of other members of RSC (including Htl1 and Rsc30) did not suppress (Figure 2B and data not shown). Furthermore, we found that phenotypes conferred by other rsc mutations (rsc1Δ rsc2, arp7, arp9, rsc2Δ, rsc1Δ, rsc8) could not be suppressed by an increased dosage of Rsc3 (A. Schlichter and B. R. Cairns, unpublished data and Figure 5). These results support our biochemical work suggesting that Rsc7 promotes the interaction of the Rsc3/30 heterodimer with RSC.

Figure 5.

Growth defects conferred by rsc8 are suppressed through increased dosage of RSC7 or HTL1. A rsc8 mutant strain (J. Lenkart and B. R. Cairns, unpublished data) harboring high-copy plasmids, p136 (RSC7+), p1310 (RSC3+), p1204 (HTL1+) p185 (RSC8+), or pRS426 (empty vector), were grown and spotted as in Figure 2.

Rsc3 has strong genetic interactions with components of the cell wall integrity pathway; rsc3 mutants are sick in combination with pkc1Δ and display cell wall defects that can be suppressed by an increased dosage of Pkc1 (Angus-Hill et al. 2001). These results prompted us to test whether the rsc7Δ strain displayed an osmotically remedial temperature sensitive phenotype. Indeed, we found that the temperature sensitivity of the rsc7Δ strain can be rescued by the addition of sorbitol (a cell wall stabilizer), CaCl2, and MgCl2 to the media (Figure 2C and data not shown), whereas other rsc mutants (such as rsc1Δ rsc2 Ts− mutants) cannot be rescued by the addition of cell wall stabilizers (A. Schlichter and B. R. Cairns, unpublished data). These results are consistent with a role for Rsc7 in the cell wall integrity pathway.

If Rsc14 also promotes Rsc3 association with the RSC complex, then increasing the levels of the Rsc3 protein might likewise suppress rsc14Δ phenotypes. Indeed, we found that rsc14Δ phenotypes are suppressed by an increased dosage of Rsc3 but not by an increased dosage of Rsc7 (Figure 3 and data not shown). These data are consistent with Rsc14 being physically linked to Rsc3, and rsc14Δ phenotypes being conferred by a decreased association of Rsc3 with the RSC complex. Thus, Rsc7 and Rsc14 are physically/functionally linked to Rsc3 and suggest an important function for the module in the maintenance of cell wall integrity.

rsc8 Ts− mutations are suppressed by an increased dosage of Rsc7:

Our biochemical results suggest that Rsc7 associates with and stabilizes Rsc8. In support of this notion, genome-wide two-hybrid experiments revealed an interaction between Rsc8 and Rsc7 (Uetz et al. 2000). To test for a functional connection, we utilized rsc8 temperature sensitive mutants (J. Lenkart and B.R Cairns, unpublished data), and found that increased dosage of Rsc7 suppressed rsc8 temperature sensitivity (Figure 5). In contrast, increased dosage of Rsc3 did not suppress rsc8 Ts− mutations, suggesting that this affect with Rsc7 is specific (Figure 5). These data support a model where Rsc7 associates with and stabilizes the core subunit Rsc8 and also helps facilitate Rsc3 association.

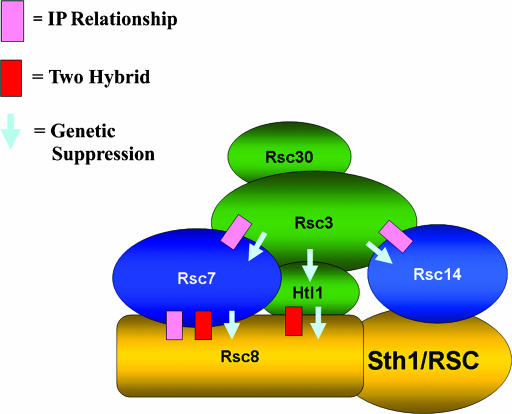

Rsc7 and Rsc14 are components of a fungal-specific module in RSC:

Our data provide evidence for an essential fungal-specific module in RSC containing Rsc7, Rsc14, Htl1, Rsc30, and Rsc3. Indeed, these subunits are restricted to fungi and most (including Rsc14, Htl1, Rsc30, and Rsc3) are present only in yeast species. We show that Rsc7 and Rsc14 are linked genetically to Htl1, Rsc3, and Rsc30 and share mutant phenotypes, suggesting they cooperate in vivo to perform specific RSC functions. In addition, we show that Rsc7 and Rsc14 have roles in mediating the assembly of module components (including Rsc3), but do not affect the assembly of other RSC subunits (including Sth1). Taken together, our results suggest that Rsc7 and Rsc14 help link Rsc3, Rsc30, and Htl1 to RSC, and together form a fungal-specific module in the RSC complex (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A yeast-specific module containing Rsc7, Rsc14, Htl1, Rsc30, and Rsc3. The physical and functional connections among members are indicated: pink boxes represent IP relationships, red boxes indicate a two-hybrid interaction, and light blue arrows indicate dosage suppression.

Isolation of null mutations conferring growth defects in combination with rsc7Δ:

Rsc7 is important for general RSC function (via Rsc8 stability) and also for module functions. As rsc7Δ strains show moderate phenotypes that encompass all known RSC functions, the rsc7Δ allele represented a moderate hypomorph ideal for examining the full scope of RSC function. Therefore, we used the rsc7Δ strain to probe the scope of RSC function in vivo using a synthetic genetic array (SGA). This approach identified null mutations that are sick or lethal in combination with the rsc7Δ null allele. A rsc7Δ strain was modified to enable crossing to each strain of a haploid deletion library, composed of ∼4700 strains each bearing a deletion in a nonessential gene and double-mutant phenotypes were determined. Remarkably, the rsc7Δ mutation displayed a strong double-mutant phenotype in combination with 125 deletion mutations, which together represented a broad range of cellular processes. We further characterized 111 of these double mutants, as 14 of these genes were linked to RSC7 or CAN1 (a haploid selection marker) and thus are likely false positives. Of these 111 we selected 67 double mutants for verification, as this subset included members of each of the many protein complexes and signaling pathways identified. We tested 67 double-mutant combinations by random spore analysis and/or tetrad dissection and determined that 45 interactions were genuine and 22 were false positives (Table 4).A comparable rate of false positives has been reported with this array by others (Tong et al. 2001).

TABLE 4.

Null mutations conferring growth defects in combination with the rsc7Δ mutation

| Broad category | Processes | Complex |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription/chromatin | ||

| ARD1 | Transcription | ARD1 |

| SDS3, DEP1 | Transcription | ECM16 |

| ELP2, ELP3, ELP6, IKI3 | Transcription | ELONGATOR |

| GIM4 | Transcription | GIM |

| ARP8 | Transcription | INO80 |

| MED1, SSN8, SSN2, SRB8 | Transcription | MEDIATOR |

| RTF1 | Transcription | PAF1 |

| BRE1 | Transcription | RAD6 |

| RSC2 | Transcription | RSC |

| SPT3, NGG1, SGF73, GCN5 | Transcription | SAGA |

| BRE2, SWD1 | Transcription | SET1 |

| SWR1, SWC1, ARP6 | Transcription | SWR1 |

| HTZ1, AOR1, VPS72, VPS71 | Transcription | SWR1 |

| SET2, CTK2 | Transcription elongation | |

| LSM6, SSF1, SNT309, SNU66 | RNA processing | |

| ASF1 | Chromatin assembly | |

| Chromosome metabolism | ||

| RTT103a, RTT101, RTT109 | Ty transposition | |

| BUB1, MAD1 | Spindle checkpoint | |

| MSC1 | Recombination | |

| CBF1 | Kinetochore | |

| CTF4, CTF8 | Cohesion | |

| EAP1 | Genetic stability | |

| Cell wall integrity | ||

| BCK1, GAS1, MID1 | ||

| FYV5, FYV1 | ||

| Transport | ||

| APG17, BRE5 | ||

| RIC1, RGP1 | ||

| VPS1, VPS61, VPS51, GOS1 | ||

| NUP84, SXM1 | ||

| Other | ||

| IFM1, MDM10, RSM7 | Mitochondria | |

| IMG2, MRPS5, CEM1, ALD5 | Mitochondria | |

| AAT2, HOM2, ILV1 | Amino acid metabolism | |

| SIC1, MEC3 | Cell cycle |

The rsc7Δ strain (YBC2039) was mated to the yeast haploid deletion set. Heterozygous double mutants were selected and sporulated on solid media. Haploid double-mutant strains (harboring the plasmid-borne RSC7+) were then isolated. These strains were scored as sick/lethal by their ability to lose the URA3-marked RSC7+ plasmid on solid media containing 5-FOA. Underlined genes were confirmed by tetrad dissection and/or random spore analysis, while other genes were identified in our screen but not verified.

The protein encoded by the RTT103 gene also has a role in transcription termination.

The 45 confirmed combinations were categorized into four broad classes: (1) chromatin/transcription, (2) chromosome metabolism, (3) cell wall integrity, and (4) transport. The chromatin/transcription class includes members of many transcription initiation and elongation complexes, including SAGA, SET1, SWR1, INO80, elongator, and mediator. Additionally, certain RNA processing mutants were identified which we have grouped into the transcription class. The second class involved chromosome metabolism and included asf1Δ (chromatin assembly); ctf4Δ and ctf8Δ (cohesion); bub1Δ and mad1Δ (spindle checkpoint); cbf1Δ (kinetochore); msc1Δ (recombination); and rtt103Δ, rtt101Δ, and rtt109Δ (Ty transposition). The third class had roles in cell wall organization and biogenesis and includes bck1Δ (cell wall integrity pathway), gas1Δ (cell wall organization), and mid1Δ (calcium transporter). Finally, the fourth class of deletion mutants identified had roles in transport: nup84Δ and sxm1Δ (nuclear transport); apg17Δ (autophagy); and bre5Δ, ric1Δ, and rgp1Δ (intracellular transport) (Table 4). Taken together, these data reveal the broad scope of RSC function by identifying nonessential deletion mutants that are sick/lethal in combination with the rsc7Δ strain. These results strengthen the connection between RSC and the cell wall integrity and spindle checkpoint pathways, two pathways with which RSC was previously linked. Furthermore, we link RSC to several chromatin/transcription-related processes, suggesting partial redundancy of function with other chromatin complexes in vivo.

Rsc7 is linked to the spindle checkpoint pathway:

Recent data suggest that RSC has roles in chromosome metabolism and the spindle checkpoint pathway (Tsuchiya et al. 1998; Hsu et al. 2003; Baetz et al. 2004; Huang et al. 2004). The spindle checkpoint pathway helps regulate progression from metaphase to anaphase during mitosis. Improperly assembled spindles promote checkpoint activation through the Mad proteins and arrest cells in metaphase until the spindle is assembled properly (Musacchio and Hardwick 2002; Lew and Burke 2003). Mutations in several RSC components, sth1, rsc3, rsc9, and htl1, all confer an arrest or delay in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle (Damelin et al. 2002; Romeo et al. 2002; Hsu et al. 2003). The G2/M arrest observed with certain rsc mutants (rsc3 and sth1) can be relieved by the removal of spindle checkpoint components (Mad proteins) (Tsuchiya et al. 1998; Angus-Hill et al. 2001; Hsu et al. 2003). To test for Rsc7 involvement in the spindle checkpoint pathway we performed FACS analysis on the rsc7Δ, which revealed a slight G2/M bias (Figure 7B). These data suggest that the spindle checkpoint pathway has become partially activated in the rsc7Δ strain. Furthermore, although the removal of key checkpoint components can relieve the G2/M growth arrest, these double mutants often display synergistic growth defects due to loss of viability (Tsuchiya et al. 1998; Hsu et al. 2003). Consistent with this notion, we find that combining spindle checkpoint pathway mutations (bub1Δ and mad1Δ) with rsc7Δ confers very slow growth (Figure 7A and Table 4). These results link Rsc7 to the spindle checkpoint pathway and strengthen the genetic connections between RSC and this pathway.

Figure 7.

Links between Rsc7 and the spindle checkpoint pathway. (A) The rsc7Δ mad1Δ double mutation confers severe growth defects. Wild-type (YBC62), rsc7Δ (YBC1332), mad1Δ (YBC936), rad9Δ (YBC939), rsc7Δ mad1Δ (YBC1470), and rsc7Δ rad9Δ (YBC1944) strains were grown to log phase, subjected to a fivefold serial dilution, and spotted onto rich media. (B) The rsc7Δ mutation confers a G2/M bias. Wild-type (YBC62) and rsc7Δ (YBC1332) strains were grown to log phase in rich medium and analyzed by FACS.

DISCUSSION

Chromatin remodeling complexes regulate the dynamic properties of chromatin and allow accessibility to the DNA template. In the SWI/SNF family of remodelers, the catalytic subunit possesses coupled ATPase and remodeling activities, while the role of other subunits is not well understood. In this study, we examined the roles of two noncatalytic RSC subunits, Rsc7 and Rsc14, and one SWI/SNF subunit, Swp82. Rsc7 and Swp82 define a new family of proteins related to Rsc7 in fungal-specific chromatin remodeling complexes. Rsc7 and Rsc14 interact with Rsc3/30 and Htl1 to define a fungal-specific functional module. We identified structural/assembly roles for Rsc7 and Rsc14, and utilized strains lacking these subunits to examine in vivo RSC functions. Importantly, we have probed the scope of RSC function in vivo through the use of SGA analysis and found novel links to chromatin/transcription, chromosome metabolism, cell wall, and transport processes.

The Rsc7 family is defined by a conserved region:

Here, we identify a novel family of proteins related to Rsc7, which may represent orthologs in fungal chromatin remodeling complexes. Family members exist in closely related hemiascomycetes yeast and in more distantly related fungal species. Like Rsc7 and Swp82, family members in other fungal species probably have roles in remodeling complexes. However, the function of the conserved domain remains elusive as we were not able to observe any phenotypes with the swp82Δ strain or with a rsc7 derivative lacking the conserved region. Therefore, our efforts have focused on Rsc7, as this member has clear phenotypes in RSC, and has helped define a fungal-specific protein module.

An essential fungal-specific protein module in RSC:

Here, we provide evidence for an essential protein module in RSC containing Rsc7, Rsc14, Htl1, Rsc30, and Rsc3. While catalytic/core subunits of RSC are conserved throughout eukaryotes, this module appears restricted to fungi, with most module members present only in yeast species. Interestingly, these subunits are linked genetically and share mutant phenotypes suggesting a cooperative function. In addition, Rsc7 and Rsc14 mediate the assembly of Rsc3/30 into RSC (Figure 4, A and B). Thus, we propose that Rsc3/30 are required for an essential cellular process that does not require Rsc3/30 orthologs in higher eukaryotes. Rsc7, Rsc14, and Htl1 help stabilize the association of Rsc3/30 with the RSC complex and form a functional module that is conserved in yeast.

Rsc3 is a putative targeting molecule in RSC containing a zinc cluster DNA binding domain, which cooperates with module subunits functionally. We show that an increased dosage of Rsc3 can suppress phenotypes conferred by the rsc7Δ, rsc14Δ, and htl1Δ mutations (Figures 2B and 3, and Romeo et al. 2002), while overexpression of Rsc7, Rsc14, or Htl1 will not suppress phenotypes conferred by rsc3 mutations (data not shown). RSC3 is essential, whereas RSC7, RSC14, and HTL1 are not. However, combining rsc7Δ with either rsc14Δ or htl1Δ results in lethality, supporting the notion that the module is essential. Taken together, Rsc3 has a central and essential role and is connected to RSC by other module members.

We propose that this module has an essential role in regulating gene expression in fungi. We speculate that RSC is targeted to certain genes by the putative DNA-binding functions of Rsc3/30, which are themselves found only in yeast species. Additional module subunits might have evolved to help regulate Rsc3/30 and to mediate their assembly into RSC. Additionally, the Rsc7, Rsc14, and Htl1 subunits may serve as an interface between specific signaling pathways (such as the Pkc1 pathway) and the RSC complex, thus helping to regulate RSC recruitment in response to cellular signals. Future studies will test these hypotheses to arrive at a mechanistic understanding of the module's function.

The scope of RSC function:

Strains lacking Rsc7 are deficient in RSC assembly yet remain viable. As Rsc7 affects both core functions (via Rsc8) and module functions (via Rsc3), the rsc7Δ strain can be utilized to examine the full scope of RSC function. We note that our work is the first in which a rsc mutant was utilized to interrogate the entire SGA array. We identified 45 nonessential null mutations that conferred increased sickness when combined with the rsc7Δ mutation and identified links between Rsc7 and chromatin/transcription, chromosome metabolism, cell wall, and transport. A significant challenge for future studies will be to determine whether the genetic interactions revealed via SGA involve a direct role for RSC in these processes, or an indirect role via transcriptional misregulation.

Chromatin/transcription:

The SGA screen identified synthetic sick interactions with subunits from 13 different complexes with various roles in transcription and chromatin regulation (Table 4). As transcriptional regulation requires the cooperative effort of multiple regulatory complexes at each gene, we suggest that impaired RSC function renders the cell totally reliant on the full function of other transcription-related complexes.

Chromosome metabolism and the spindle checkpoint pathway:

The rsc7Δ mutation confers a G2/M bias (Figure 7), as do mutations in other RSC members such as Rsc3, Htl1, Rsc9, Sth1, and Sfh1 (Cao et al. 1997; Angus-Hill et al. 2001; Chai et al. 2002; Damelin et al. 2002; Romeo et al. 2002; Hsu et al. 2003; Baetz et al. 2004), and suggests that Rsc7 has a role in chromosome transmission. Furthermore, Rsc7 has genetic interactions with other components involved in chromosome maintenance and severely reduced growth ability on media containing benomyl (Figure 2 and Table 4). Surprisingly, the rsc7Δ mutant does not display significant chromosome missegregation defects, in contrast to many other rsc mutations (Tsuchiya et al. 1998; Lanzuolo et al. 2001; Hsu et al. 2003; Baetz et al. 2004; Huang et al. 2004). Therefore, we propose that the low level of RSC assembly in rsc7Δ mutants confers mild defects that are exacerbated in combination with additional perturbations to the chromosome segregation process (such as the addition of benomyl).

We further show that Rsc7 is linked to both cohesin and centromere functions. Previous experiments by others have shown that RSC has at least two roles in chromosome metabolism: (1) cohesin loading on chromosome arms and (2) centromere function. First, RSC physically and genetically interacts with cohesin subunits and occupies cohesin binding sites on chromosome arms. Furthermore, mutations in Sth1 and Rsc2 prevent cohesin loading to chromosome arms (Baetz et al. 2004; Huang et al. 2004). Second, RSC affects centromeric chromatin structure independent of cohesin function (Tsuchiya et al. 1998; Hsu et al. 2003). Our work identified genetic interactions between Rsc7 and components required for cohesin function (Ctf4 and Ctf8) and a component required for centromere function (Cbf1), thus strengthening the connection between RSC and both of these processes. Furthermore, we identify genetic interactions with components involved in other areas of chromosome metabolism that may lead to new RSC functions (Table 4).

Cell wall integrity:

Previous experiments have linked RSC to cell wall function (Angus-Hill et al. 2001; Hosotani et al. 2001; Chai et al. 2002; Romeo et al. 2002; Jones et al. 2003; Corbacho et al. 2004; Kasten et al. 2004). Here, we show that rsc7Δ and rsc14Δ mutants have clear cell wall defects. More importantly, we identify cell wall regulators that interact genetically with Rsc7. Among these are Gas1 (which regulates cross-linking of cell wall glucans) and the Fyv1 and Fyv5 proteins (which influence cell wall glucan levels). Interestingly, mutations in all components of the yeast-specific RSC module, and not other subunits (B. Wilson and B. Cairns, unpublished data), confer cell wall defects, suggesting an important module function in regulating cell wall integrity.

DNA damage response:

Our work supports and extends links between RSC and the DNA double-strand break repair (Koyama et al. 2002). Rsc8 and Rsc30 were identified in a screen for novel nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) factors, and mutations in either of these RSC components lead to an impairment in NHEJ. Furthermore, RSC is recruited to double-strand breaks and interacts with other NHEJ factors such as Mre11 and Ku80 (Shim et al. 2005). Very recently, RSC was shown to have roles in double-strand break repair via homologous recombination (Chai et al. 2005). Indeed, our analysis of the rsc7Δ mutation strengthens this link as the rsc7Δ mutation confers sensitivity to an assortment of DNA damaging agents. Interestingly, we find that cells lacking Rsc7 are compromised for growth in cells lacking Mec3 (part of a putative sliding clamp loading complex required for double-strand break repair) (Table 4) and Rad9 (a DNA repair checkpoint protein) (Figure 7).

Conclusion:

The RSC complex is now emerging as a mosaic of modules with specialized functions. Understanding how these modules and their individual subunits function is of critical importance to understanding overall complex regulation. Here, we have characterized two components in the remodeler RSC, Rsc7 and Rsc14, which have led to the identification of a fungal-specific functional module. Importantly, Rsc7 and Rsc14 help mediate the association between the essential Rsc3 component and RSC, and the rsc7Δ and rsc14Δ mutations have given insight into the in vivo functions of the module. Thus, our studies on Rsc7 and Rsc14 have broadened our understanding of RSC assembly, led to the identification of several subunits that cooperate physically/functionally in RSC, and strengthened links between RSC and many important cellular processes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Pam Silver for providing RSC7 plasmids and the rsc9-1 mutant strain. We thank Marian Carlson for the RSC8 plasmids and Jeff Lenkart for rsc8 mutants. We thank David Levin for HTL1 strains and plasmids. We thank Mat Gordon, Alisha Schlichter, and Maggie Kasten for helpful insights and discussion on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM60415 to B.R.C.

References

- Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers and D. J. Lipman, 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus-Hill, M. L., A. Schlichter, D. Roberts, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst et al., 2001. A Rsc3/Rsc30 zinc cluster dimer reveals novel roles for the chromatin remodeler RSC in gene expression and cell cycle control. Mol. Cell 7: 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetz, K. K., N. J. Krogan, A. Emili, J. Greenblatt and P. Hieter, 2004. The ctf13–30/CTF13 genomic haploinsufficiency modifier screen identifies the yeast chromatin remodeling complex RSC, which is required for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 1232–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin, A., O. Ozier-Kalogeropoulos, A. Denouel, F. Lacroute and C. Cullin, 1993. A simple and efficient method for direct gene deletion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 21: 3329–3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, P. B., and W. Horz, 2002. ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71: 247–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossie, M. A., C. DeHoratius, G. Barcelo and P. Silver, 1992. A mutant nuclear protein with similarity to RNA binding proteins interferes with nuclear import in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 3: 875–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann, C. B., A. Davies, G. J. Cost, E. Caputo, J. Li et al., 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14: 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungard, D., M. Reed and E. Winter, 2004. RSC1 and RSC2 are required for expression of mid-late sporulation-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryotic Cell 3: 910–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, B. R., Y. J. Kim, M. H. Sayre, B. C. Laurent and R. D. Kornberg, 1994. A multisubunit complex containing the SWI1/ADR6, SWI2/SNF2, SWI3, SNF5, and SNF6 gene products isolated from yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 1950–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, B. R., Y. Lorch, Y. Li, M. Zhang, L. Lacomis et al., 1996. RSC, an essential, abundant chromatin-remodeling complex. Cell 87: 1249–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, B. R., H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, F. Winston and R. D. Kornberg, 1998. Two actin-related proteins are shared functional components of the chromatin-remodeling complexes RSC and SWI/SNF. Mol. Cell 2: 639–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, B. R., A. Schlichter, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, R. D. Kornberg et al., 1999. Two functionally distinct forms of the RSC nucleosome-remodeling complex, containing essential AT hook, BAH, and bromodomains. Mol. Cell 4: 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y., B. R. Cairns, R. D. Kornberg and B. C. Laurent, 1997. Sfh1p, a component of a novel chromatin-remodeling complex, is required for cell cycle progression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 3323–3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai, B., J. M. Hsu, J. Du and B. C. Laurent, 2002. Yeast RSC function is required for organization of the cellular cytoskeleton via an alternative PKC1 pathway. Genetics 161: 575–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai, B., J. Huang, B. R. Cairns and B. C. Laurent, 2005. Distinct roles for the RSC and Swi/Snf ATP-dependent chromatin remodelers in DNA double-strand break repair. Genes Dev. 19: 1656–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbacho, I., I. Olivero and L. M. Hernandez, 2004. Identification of low-dye-binding (ldb) mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 4: 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damelin, M., I. Simon, T. I. Moy, B. Wilson, S. Komili et al., 2002. The genome-wide localization of Rsc9, a component of the RSC chromatin-remodeling complex, changes in response to stress. Mol. Cell 9: 563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, J., I. Nasir, B. K. Benton, M. P. Kladde and B. C. Laurent, 1998. Sth1p, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae Snf2p/Swi2p homolog, is an essential ATPase in RSC and differs from Snf/Swi in its interactions with histones and chromatin-associated proteins. Genetics 150: 987–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk, M., R. Niedenthal, D. Mumberg, K. Brinkmann, V. Ronicke et al., 2002. Vector systems for heterologous expression of proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 350: 248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin, A. C., M. Bosche, R. Krause, P. Grandi, M. Marzioch et al., 2002. Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415: 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann, J., L. A. Dunipace, J. H. Seol, W. H. McDonald, J. R. Yates III et al., 2004. Applicability of tandem affinity purification MudPIT to pathway proteomics in yeast. Mol. Cell Proteomics 3: 226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinisch, J. J., A. Lorberg, H. Schmitz and J. J. Jacoby, 1999. The protein kinase C-mediated MAP kinase pathway involved in the maintenance of cellular integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 32: 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosotani, T., H. Koyama, M. Uchino, T. Miyakawa and E. Tsuchiya, 2001. PKC1, a protein kinase C homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, participates in microtubule function through the yeast EB1 homologue, BIM1. Genes Cells 6: 775–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, J. M., J. Huang, P. B. Meluh and B. C. Laurent, 2003. The yeast RSC chromatin-remodeling complex is required for kinetochore function in chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 3202–3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J., J. M. Hsu and B. C. Laurent, 2004. The RSC nucleosome-remodeling complex is required for Cohesin's association with chromosome arms. Mol. Cell 13: 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein, T., and C. D. Allis, 2001. Translating the histone code. Science 293: 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. L., J. Petty, D. C. Hoyle, A. Hayes, E. Ragni et al., 2003. Transcriptome profiling of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant with a constitutively activated Ras/cAMP pathway. Physiol. Genomics 16: 107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasten, M., H. Szerlong, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, M. Werner et al., 2004. Tandem bromodomains in the chromatin remodeler RSC recognize acetylated histone H3 Lys14. EMBO J. 23: 1348–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama, H., M. Itoh, K. Miyahara and E. Tsuchiya, 2002. Abundance of the RSC nucleosome-remodeling complex is important for the cells to tolerate DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 531: 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzuolo, C., S. Ederle, A. Pollice, F. Russo, A. Storlazzi et al., 2001. The HTL1 gene (YCR020W-b) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is necessary for growth at 37°C, and for the conservation of chromosome stability and fertility. Yeast 18: 1317–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. K., P. Prochasson, L. Florens, S. K. Swanson, M. P. Washburn et al., 2004. Proteomic analysis of chromatin-modifying complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies novel subunits. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32: 899–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin, D. E., 2005. Cell wall integrity signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69: 262–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew, D. J., and D. J. Burke, 2003. The spindle assembly and spindle position checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Genet. 37: 251–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie, III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach et al., 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, M. C., R. S. Muir, E. Lim, J. McElver, S. C. Weber et al., 1995. Gene disruption with PCR products in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 158: 113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. M., Y. R. Lin, A. Tsai, Y. S. Hsao, C. C. Li et al., 2003. Dissecting the pet18 mutation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: HTL1 encodes a 7-kDa polypeptide that interacts with components of the RSC complex. Mol. Genet. Genomics 269: 321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens, J. A., and F. Winston, 2003. Recent advances in understanding chromatin remodeling by Swi/Snf complexes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrmann, L., and C. P. Verrijzer, 2005. Composition and functional specificity of SWI2/SNF2 class chromatin remodeling complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1681: 59–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio, A., and K. G. Hardwick, 2002. The spindle checkpoint: structural insights into dynamic signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3: 731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar, G. J., H. Y. Fan and R. E. Kingston, 2002. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell 108: 475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C. L., A. Dingwall and M. P. Scott, 1994. Five SWI/SNF gene products are components of a large multisubunit complex required for transcriptional enhancement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 2905–2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, M. L., S. Sif, G. J. Narlikar and R. E. Kingston, 1999. Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol. Cell 3: 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo, M. J., M. L. Angus-Hill, A. K. Sobering, Y. Kamada, B. R. Cairns et al., 2002. HTL1 encodes a novel factor that interacts with the RSC chromatin remodeling complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 8165–8174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M. D., F. Winston and P. Hieter, 1990. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Saha, A., J. Wittmeyer and B. R. Cairns, 2002. Chromatin remodeling by RSC involves ATP-dependent DNA translocation. Genes Dev. 16: 2120–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, S. L., J. Jennings, A. Canutescu, A. J. Link and P. A. Weil, 2002. Proteomics of the eukaryotic transcription machinery: identification of proteins associated with components of yeast TFIID by multidimensional mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 4723–4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim, E. Y., J. L. Ma, J. H. Oum, Y. Yanez and S. E. Lee, 2005. The yeast chromatin remodeler RSC complex facilitates end joining repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 3934–3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson, M. J., H. Qiu, L. Sumibcay, A. Krueger, S. J. Kim et al., 2003. A multiplicity of coactivators is required by Gcn4p at individual promoters in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 2800–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneda, T., and A. Kikuchi, 2004. Genetic analysis of RSC58, which encodes a component of a yeast chromatin remodeling complex, and interacts with the transcription factor Swi6. Mol. Genet. Genomics 271: 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. H., M. Evangelista, A. B. Parsons, H. Xu, G. D. Bader et al., 2001. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294: 2364–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treich, I., and M. Carlson, 1997. Interaction of a Swi3 homolog with Sth1 provides evidence for a Swi/Snf- related complex with an essential function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 1768–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treich, I., L. Ho and M. Carlson, 1998. Direct interaction between Rsc6 and Rsc8/Swh3, two proteins that are conserved in SWI/SNF-related complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 3739–3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya, E., T. Hosotani and T. Miyakawa, 1998. A mutation in NPS1/STH1, an essential gene encoding a component of a novel chromatin-remodeling complex RSC, alters the chromatin structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae centromeres. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 3286–3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama, T., 2002. The in vivo functions of ATP-dependent chromatin remodelling factors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3: 422–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz, P., L. Giot, G. Cagney, T. A. Mansfield, R. S. Judson et al., 2000. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403: 623–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignali, M., A. H. Hassan, K. E. Neely and J. L. Workman, 2000. ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20: 1899–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse, I., C. Stockdale, A. Flaus, M. D. Szczelkun and T. Owen-Hughes, 2003. Evidence for DNA translocation by the ISWI chromatin-remodeling enzyme. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 1935–1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]