Abstract

Ras-mediated signaling is necessary for the induction of vulval cell fates during Caenorhabditis elegans development. We identified cgr-1 by screening for suppressors of the ectopic vulval cell fates caused by a gain-of-function mutation of the let-60 ras gene. Analysis of two cgr-1 loss-of-function mutations indicates that cgr-1 positively regulates induction of vulval cell fates. cgr-1 is likely to function at a step in the Ras signaling pathway that is downstream of let-60, which encodes Ras, and upstream of lin-1, which encodes a transcription factor, if these genes function in a linear signaling pathway. These genetic studies are also consistent with the model that cgr-1 functions in a parallel pathway that promotes vulval cell fates. Localized expression studies suggest that cgr-1 functions cell autonomously to affect vulval cell fates. cgr-1 also functions early in development, since cgr-1 is necessary for larval viability. CGR-1 contains a CRAL/TRIO domain likely to bind a small hydrophobic ligand and a GOLD domain that may mediate interactions with proteins. A bioinformatic analysis revealed that there is a conserved family of CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domain-containing proteins that includes members from vertebrates and Drosophila. The analysis of cgr-1 identifies a novel in vivo function for a member of this family and a potential new regulator of Ras-mediated signaling.

RAS is a pivotal protein in signal transduction pathways that regulate important cellular processes such as proliferation, migration, and differentiation, and the ras gene is frequently mutated in human tumors (Barbacid 1987). The Ras signaling pathway regulates multiple cell fates during the development of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, and its role in the development of the hermaphrodite vulva has been characterized extensively (reviewed in Kornfeld 1997; Sternberg and Han 1998). The vulva is a specialized epithelial tube used for egg laying and sperm entry formed by the descendants of three hypodermal blast cells: P5.p, P6.p, and P7.p. During larval development, the anchor cell in the somatic gonad signals to P6.p by expressing the LIN-3 epidermal growth factor ligand. LIN-3 binding to the LET-23 receptor tyrosine kinase triggers activation of a conserved signaling pathway that includes the SEM-5 adapter protein, the LET-341 guanine nucleotide exchange factor, the LET-60 Ras protein, the LIN-45 Raf kinase, the MEK-2 kinase, and the MPK-1 ERK MAP kinase. MPK-1 phosphorylates multiple target proteins, including the LIN-1 ETS transcription factor. The activation of this signaling pathway causes P6.p to adopt a primary vulval cell fate and generate eight descendants. P6.p then signals to P5.p and P7.p through the LIN-12 Notch receptor, causing these cells to adopt the secondary vulval cell fate and generate seven descendants. Three additional hypodermal blast cells, P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p, are capable of adopting vulval cell fates but normally receive neither signal and thus adopt the tertiary nonvulval cell fate. Loss-of-function mutations in core signaling genes cause P5.p, P6.p, and P7.p to adopt nonvulval cell fates resulting in a vulvaless (Vul) phenotype. By contrast, gain-of-function mutations in core signaling genes such as let-60 ras cause P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p to inappropriately adopt vulval cell fates resulting in ectopic pseudovulvae: a phenotype designated multivulva (Muv).

The activities of the core signaling proteins are highly regulated, but the mechanisms of regulation have not been fully characterized. An advantage of the C. elegans system is the ability to identify regulators of the pathway by conducting sensitive screens for genes that affect Ras-mediated signaling. Others and we have described screens for mutations that suppress the Muv phenotype caused by activated let-60 ras. These screens identified mutations in the core signaling genes lin-45 raf (Hsu et al. 2002), mek-2 (Kornfeld et al. 1995a; Wu et al. 1995), and mpk-1 (Lackner et al. 1994; Wu and Han 1994). These screens also identified novel regulators of the pathway including kinase suppressor of Ras (KSR)-1, a probable adapter protein for Raf, MEK, and ERK (Kornfeld et al. 1995b; Sundaram and Han 1995); suppressor of activated Ras (SUR)-8, a leucine-rich repeat protein that binds Ras (Sieburth et al. 1998); SUR-2, a component of the mediator complex (Singh and Han 1995); SUR-6, a component of the PP2A phosphatase that may regulate Raf (Sieburth et al. 1999); and CDF-1 and SUR-7, proteins involved in zinc metabolism and Ras-mediated signaling (Bruinsma et al. 2002; Yoder et al. 2004). Several of these proteins have been demonstrated to have conserved functions in regulating Ras signaling in insects and vertebrates.

Here we describe the genetic and molecular characterization of cgr-1, a new gene identified in a screen for suppressors of activated let-60 ras. Genetic studies indicated that cgr-1 positively regulates Ras-mediated signaling and functions downstream of let-60 ras and upstream of the lin-1 ETS transcription factor. CGR-1 contains two conserved domains, a CRAL/TRIO domain that is likely to form a pocket that binds a small, hydrophobic ligand and a GOLD domain; both domains were necessary for the full activity of CGR-1. Bioinformatic studies showed that there is a family of proteins with both CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domains that includes members in vertebrates and insects. These proteins have not been implicated in Ras signaling, and these studies establish an in vivo function for a member of this protein family and identify a new regulator of Ras signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods and strains:

C. elegans strains were cultured as described by Brenner (1974) and grown at 20° unless otherwise noted. The wild-type strain and parent of all mutant strains was N2. CB4856 was used for single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mapping. The following mutations are described by Riddle et al. (1997): LGIII, dpy-17(e164); LGIV, unc-24(e138), dpy-20(e1282); and LGX, unc-78(e1217), lon-2(e678). The following mutations that affect vulval development were examined. let-60(n1046 gf) is a semidominant, temperature-sensitive mutation that results in a G13E substitution and a Ras protein that is constitutively active (Beitel et al. 1990). let-60(ga89) causes a gain-of-function Muv phenotype at high temperatures and a loss-of-function Vul phenotype at low temperatures and results in a L19F substitution (Eisenmann and Kim 1997). lin-1(n383) causes a strong loss-of-function and results in a Q298STOP substitution (Beitel et al. 1995). lin-45(n2520) partially reduces lin-45 function and results in a S751F substitution that affects the C-terminal 14-3-3 binding site of Raf (Hsu et al. 2002). sur-8(ku167) results in a E430K substitution and causes a loss-of-function of the leucine-rich repeat protein SUR-8 (Sieburth et al. 1998). lin-12(n137gf) results in a S872F substitution and a constitutively active Notch protein (Greenwald and Seydoux 1990). lin-31(n1053) is an apparent null allele that results in a W57STOP substitution, causing a truncation in the middle of the DNA-binding domain of the winged-helix transcription factor LIN-31 (Miller et al. 2000). lin-15(n765) is a temperature-sensitive, partial loss-of-function mutation that affects both lin-15A and lin-15B transcripts (Clark et al. 1994). mpk-1(n2521) results in a L124F substitution that causes a partial loss-of-function of ERK MAP kinase (Lackner et al. 1994). cgr-1(n2528) and cgr-1(am114) are described here.

Identification of cgr-1 alleles:

We previously described a screen for suppressors of the let-60(n1046) Muv phenotype (Lackner et al. 1994; Kornfeld et al. 1995a,b; Jakubowski and Kornfeld 1999; Hsu et al. 2002). In brief, we used EMS to mutagenize let-60(n1046) hermaphrodites, placed 2794 F1 progeny on separate petri dishes, and examined the F2 self-progeny for non-Muv animals. We identified 33 independently derived mutations that reduced the penetrance of the Muv phenotype from 93% to <10%. One of these mutations was n2528. Seven additional mutations were isolated in a related screen (Beitel et al. 1990).

To isolate a cgr-1 deletion allele, we mutagenized wild-type N2 hermaphrodites on day 1 with 30 μg/ml trimethylpsoralen for 15 min, followed by a 90-sec exposure to 365 nm ultraviolet light from a UVL-21 BLAK RAY lamp (Ultra-Violet Products, Upland, CA) at 340 μW/cm2 measured with an IL1400A ultraviolet light dose meter (International Light, Newburyport, MA). On day 2, mutagenized animals were incubated in a bleach solution (3 ml 20% NaOCl−, 2 ml 4 m NaOH). Eggs were collected, plated on NGM/agar plates without bacterial lawns, and incubated overnight to obtain a population of arrested L1 larvae. On day 3, we collected larvae in M9 buffer (170 mm KH2PO4, 130 mm Na2HPO4, 86 mm NaCl, and 1 mm MgSO4) and distributed ∼50 larvae per plate to NGM/agar plates containing a lawn of Escherichia coli OP50. In total, we prepared 3840 plates with ∼100 mutagenized genomes per plate. These animals were propagated until the bacteria were consumed, ∼8 days at 20°. We collected the starved animals in 600 μl of M9 buffer per plate and distributed 150-μl aliquots to corresponding wells on each of two 1-ml 96-well Co-Star assay blocks (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh). To one 96-well plate, we added 150 μl of freezing solution (100 mm NaCl, 30 mm KH2PO4, 140 mm NaOH, 300 μm MgSO4, and 30% glycerol) and stored these worms at −80° for future mutant recovery. To the other 96-well plate, we added 150 μl of lysis buffer (50 mm KCl, 10 mm Tris, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 0.9% NP-40, 0.01% gelatin, and 60 μg/liter proteinase K), incubated it at −80° for 4–8 hr, at 60° for 12–16 hr, and at 95° for 30–60 min to prepare DNA suitable for PCR. For initial screening, DNA lysates from 10 96-well plates were pooled into 1 96-well plate. Five microliters of this pooled DNA lysate were used as a template for a nested PCR reaction, using primers to amplify a 3.1-kb fragment spanning the entire cgr-1 genomic locus. The PCR reactions were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis; the cgr-1(am114) deletion was identified as a faster-migrating band. To recover worms with this allele, we thawed the appropriate well from the stock of frozen worms, distributed 1200 animals to individual plates, and used PCR to identify a population of animals homozygous for the deletion allele. The cgr-1(am114) strain was backcrossed four times to N2. The deletion endpoints were determined by DNA sequencing and are base pairs 30,198 and 32,401 on cosmid T27A10.

Genetic mapping:

We used standard techniques to generate the recombinant chromosome unc-78(e1217) cgr-1(n2528) lon-2(e678) and hermaphrodites of the genotype let-60(n1046); unc-78(e1217) cgr-1(n2528) lon-2(e678)/CB4856. Unc non-Lon and Lon non-Unc self-progeny were selected, and animals homozygous for the recombinant chromosome were selected and scored for the suppression of let-60(n1046) Muv phenotype (Figure 1A).

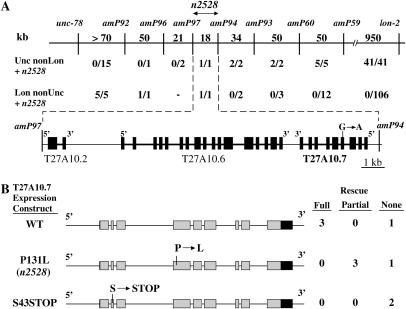

Figure 1.

Cloning cgr-1. (A) A portion of the physical map on LGX. Polymorphisms are differences between the nucleotide sequences of CB4856 and wild-type N2 and are designated amPX. A total of 130 Lon non-Unc and 69 Unc non-Lon progeny were selected from let-60(n1046gf); unc-78 n2528 lon-2 / CB4856 hermaphrodites. We determined the interval that includes the recombination event by scoring polymorphisms and the presence of n2528 by scoring suppression of the let-60(n1046gf) Muv phenotype. These data positioned n2528 between amP97 and amP94. This interval is expanded below; exons (boxes) and introns (thick lines) of Genefinder predicted open reading frames are shown. The G-to-A change in n2528 animals is shown. (B) Plasmids containing wild-type (pJG1) or mutant T27A10.7 (pJG2, pJG3) were used to generate transgenic strains. The chromosomal genotype was let-60(n1046); n2528. Each rescue result represents an independently derived transgenic strain. We defined full rescue as >80% Muv, partial rescue as 40–80% Muv, and no rescue as <40% Muv.

To identify polymorphisms, we determined the DNA sequence of 1.2-kb fragments from predicted intergenic regions positioned between unc-78 and lon-2, using DNA from CB4856 worms (as described by Jakubowski and Kornfeld 1999). Nine polymorphisms were identified by analyzing ∼10 kb of DNA. amP59 is a 55-bp insertion at position 6269 of cosmid T14G12, amP60 is an A-to-G substitution at position 18,282 of cosmid C02F12, amP91 is a T-to-C substitution at position 20,029 of cosmid T27A10, amP92 is a 1-bp deletion at position 260 of cosmid F56B6, amP93 is a G-to-A substitution at position 3273 of cosmid R11G1, amP94 is a T-to-C substitution at position 34,167 of cosmid T27A10, amP95 is an A-to-G substitution at position 29,039 of cosmid T27A10, amP96 was scored by the absence of PCR amplification of the region from 5909 to 7180 of cosmid F59D8, and amP97 is a T-to-G substitution at position 16,482 of cosmid T27A10. Cosmids are numbered according to wormbase/NCBI.

For each of the 199 recombinant strains, the interval that contains the recombination event between N2 and CB4856 DNA was determined by using DNA sequencing or PCR amplification and gel electrophoresis to score polymorphisms (Figure 1A).

DNA cloning:

All molecular biology techniques were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (1989), unless otherwise noted. To subclone the T27A10.7 predicted ORF, we ligated a 4785-bp SacI/SacII fragment of cosmid T27A10 that extends 990 bp upstream of the ATG (start) and 760 bp downstream of the TAA (stop) and does not contain sequences from adjacent predicted genes into pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) to create the plasmid pJG1. To engineer the G-to-A n2528 mutation, we replaced the 1935-bp AatII/SnaBI fragment of pJG1 with the corresponding fragment from PCR-amplified DNA derived from cgr-1(n2528) worms, creating pJG3. We used standard in vitro mutagenesis techniques to introduce a C-to-A change into pJG1 that alters codon 43 from TCG (serine) to TAG (stop), creating the plasmid pJG2. pDG125 contains the cgr-1 genomic DNA coding region and encodes a CGR-1:GFP fusion protein; it was generated by ligating an 869-bp GFP genomic sequence from pPD95.77 (Chalfie et al. 1994) into pJG1 digested with AscI. pDG135 and pDG141 contain cgr-1 cDNA and encode CGR-1:GFP fusion proteins; a PCR-amplified 1104-bp fragment containing the cgr-1 cDNA was ligated into pDG125 digested with AgeI and BspEI. pDG141 was modified to generate pDG147, which encodes CGR-1(K230A) and pDG146, which encodes CGR-1(292Stop). To express the cgr-1 cDNA from the lin-31 promoter, we constructed pDG149 by ligating the 2000-bp cgr-1 cDNA:GFP fragment from pDG141 into the 10,899-bp backbone of pJJ25 (Bruinsma et al. 2002). To express the cgr-1 cDNA from the ges-1 promoter, we constructed pDG151 by ligating the 2000-bp cgr-1 cDNA:GFP fragment from pDG141 into the 6267-bp pJM16 plasmid (Bruinsma et al. 2002).

Identification and analysis of cDNA:

We obtained the cDNAs, yk464g7 and yk708h11, from the C. elegans EST project (Kohara 1996). We isolated phage DNA according to the Lambda ZAP II in vivo excision protocol (Stragene, La Jolla, CA). DNA sequencing revealed a poly(A) tail attached 145 bp downstream of the STOP codon of both cDNAs. yk708h11 contained an SL1 sequence attached 2 bp upstream of the ATG start codon. The 5′ end of yk464g7 was in codon 2. To further characterize the position of the SL1 attachment site and the splicing pattern of exons 1–4, we purified total RNA from a mixed-stage population of N2 worms by Trizol extraction. RT–PCR was performed according to the Titan one-tube RT–PCR protocol (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis), using a forward primer that is complementary to the SL1 trans-spliced leader and contains a SacI site and a reverse primer that is complementary to exon 4 and contains a KpnI site. PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes and cloned into SacI/KpnI-digested pBluescript SK+ (Stratagene). We isolated three of these colonies, purified the plasmid, and sequenced the cDNA. These three independently derived cDNAs had the identical sequence and contained an SL1 leader sequence attached to the cgr-1 transcript 2 bp upstream of the start codon. We performed RT–PCR with oligonucleotide primers that span each intron and identified a single product in each case that corresponds to the predicted size on the basis of the analysis of cgr-1 cDNAs.

We identified three differences from the coding region predicted by Genefinder: (1) Exon 4 is 5 bp shorter than predicted, (2) the 111-bp exon 5 was not predicted, and (3) exon 6 is 107 bp longer than predicted. The positions of the exons on cosmid T27A10 are as follows: exon 1, 33,043–32,943; exon 2, 32,888–32,824; exon 3, 32,777–32,584; exon 4, 31,665–31,447; exon 5, 31,391–31,281; exon 6, 31,233–31,088; exon 7, 30,556–30,487; exon 8, 30,439–30,344; and exon 9, 30,158–30,009.

Transformation rescue:

Germline transformation experiments were performed as described by Mello et al. (1991). We co-injected let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528) hermaphrodites with C. elegans DNA cloned in cosmids or plasmids (0.01–20 ng/μl) and with the plasmid pRF4 (80–100 ng/μl), which contains a dominant mutation rol-6(su1006). Transgenic lines were established by identifying F1 Rol animals that segregated F2 Rol animals.

RNA-mediated interference:

RNA was prepared according to the MEGAscript protocol (Ambion, Austin, TX), using the yk464g7 cDNA as template. Injections were performed as described previously (Fire et al. 1998). We injected RNA at 1 mg/ml into N2 or let-60(n1046) adult hermaphrodites raised at either 20° or 15°.

Phylogeny:

Homologous predicted protein sequences were identified using BLASTP with C. elegans CGR-1 as query. Presence of a CRAL/TRIO domain was determined using an HMM (Pfam 13.0, PF00650) (Sonnhammer et al. 1997), and presence of a GOLD domain was determined as described (Anantharaman and Aravind 2002). Sequences were aligned using CLUSTALX (Thompson et al. 1997), columns with gaps were removed, and sequences were realigned. Phylogenetic inference was performed using neighbor joining (NJ) (PHYLIP version 3.6) (Felsenstein 1989). Tree topology was tested using two methods: bootstrapping with 1000 replicates and rebuilding the phylogeny using maximum parsimony (MP). NJ and MP produced an identical branching pattern (data not shown).

RESULTS

Identification of cgr-1(n2528):

The gain-of-function mutation let-60(n1046) results in a mutant Ras protein that is constitutively active and causes a Muv phenotype that is partially penetrant and heat sensitive (Beitel et al. 1990). let-60(n1046) is similar to mutations in codon 12 of human Ras that are frequently identified in human tumors and reduce the GTPase activity of the Ras protein (Barbacid 1987). We identified the n2528 mutation in a screen suppressors of the Muv phenotype caused by let-60(n1046) (see materials and methods). The strain containing n2528 was backcrossed to wild-type animals to remove extraneous mutations. The suppression of the let-60 Muv phenotype caused by n2528 displayed linkage to lon-2 on chromosome X, and three-factor mapping experiments positioned n2528 between the visible markers unc-78 and lon-2 (data not shown). No other mutation isolated in this screen was positioned in this interval, and this interval did not contain previously characterized mutations that cause a similar phenotype. These results indicated that the n2528 mutation affects a C. elegans gene that has not been previously reported to be involved in Ras-mediated signaling.

cgr-1(n2528) is a mutation in the predicted open reading frame T27A10.7 and causes a loss of gene activity:

To identify the gene affected by the n2528 mutation, we mapped the suppression of the let-60(n1046) Muv phenotype caused by n2528 relative to SNPs. A total of 199 animals with a recombination event near n2528 were selected using the visible markers Unc-78 and Lon-2, and a local, high-density map consisting of seven SNPs between unc-78 and lon-2 was used to position the n2528 mutation to an 18-kb interval between the polymorphisms amP97 and amP94 (Figure 1A). We determined the DNA sequence of the three predicted open reading frames in this interval and identified 1 bp change in n2528 mutants compared to wild-type animals. This G-to-A change results in a proline-to-leucine substitution in the predicted protein encoded by T27A10.7 (Figure 1A).

To test the hypothesis that the n2528 mutation affects T27A10.7, we analyzed the activity of T27A10.7 in transgenic animals. A 4.8-kb fragment of genomic DNA including 1.0 kb upstream of the predicted start codon, the entire T27A10.7 coding region, and 0.8 kb downstream of the predicted stop codon was introduced into let-60(n1046); n2528 mutant worms. Transgenic animals containing a multicopy array of this DNA displayed robust rescue of the suppression of Muv phenotype (Figure 1B), indicating that T27A10.7 is indeed the gene affected by the n2528 mutation. To determine if the rescuing activity requires an intact open reading frame, we engineered the following two mutations into rescuing constructs: (1) a single-base change that results in a premature stop at codon 43 and (2) the G-to-A change present in the n2528 allele. The premature stop codon eliminated the rescuing activity, whereas the n2528 mutation reduced, but did not completely eliminate, rescuing activity (Figure 1B). These results indicate that the rescuing activity requires the protein encoded by T27A10.7 and that the n2528 mutation partially reduces the activity or stability of this protein.

cgr-1 encodes a protein with CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domains:

To characterize the structure of the mRNA encoded by T27A10.7, we completely sequenced two independently derived cDNAs generated by the C. elegans expressed sequence tags (EST) project (Kohara 1996). In addition, T27A10.7 transcripts present in RNA isolated from mixed-stage populations of worms were analyzed by RT–PCR. These studies indicated that the transcript consists of nine exons and the predicted protein contains 383 amino acids (Figure 2, A and B). The 5′ end of the transcript contains an SL1 leader sequence that is attached two nucleotides upstream of the predicted start ATG. The 3′ end of the transcript contains a poly(A) tail. The analysis of cDNAs and RT–PCR products indicated that there is one predominant splicing pattern and did not provide evidence for alternative splicing.

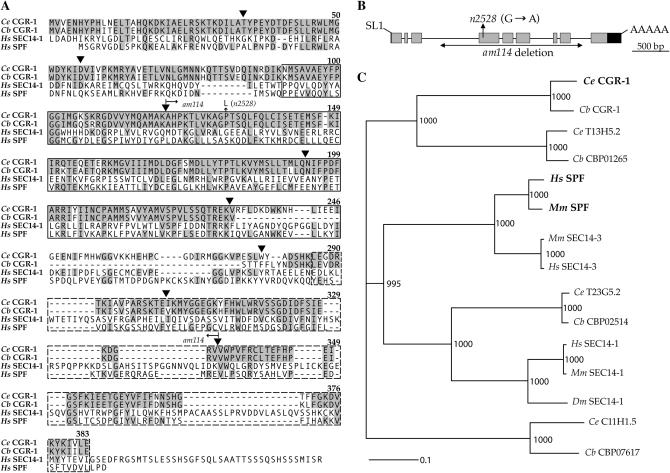

Figure 2.

cgr-1 encodes a protein with CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domains. (A) Full-length C. elegans CGR-1 protein (Ce CGR-1) is aligned with the predicted full-length C. briggsae CGR-1 protein (Cb CGR-1), with amino acids 239–715 of the predicted human SEC14-1 protein (Hs SEC14-1; Chinen et al. 1996), and with the full-length predicted human SPF protein (Hs SPF; Shibata et al. 2001). Amino acid numbers refer to Ce CGR-1. Shaded residues are identical to Ce CGR-1. The CRAL/TRIO domain is boxed with a solid line and the GOLD domain is boxed with a hatched line. Triangles indicate intron positions. Arrows indicate the position of the cgr-1(n2528) mutation (P131L) and the coding region removed by the cgr-1(am114) deletion (amino acids 121–334). (B) Diagram of the cgr-1 locus. Boxes represent exons. Shaded boxes and the solid box show coding and untranslated regions, respectively. The thin line represents introns. An SL1 leader sequence is spliced 2 nucleotides upstream of the start codon. A poly(A) tail is attached 145 nucleotides downstream of the stop codon. Arrows indicate the position of the n2528 mutation and the endpoints of the am114 deletion. (C) Neighbor-Joining tree illustrating phylogenetic relationships of predicted CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domain-containing proteins. Boldface type indicates proteins that have been biochemically or genetically characterized. Branch lengths are proportional to divergence (scale represents 10% divergence). Numbers at each node indicate bootstrap support out of 1000 replicates. All nodes were well supported. Mm, mus musculus; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster.

A BLAST search was used to identify homologous proteins. An alignment of these proteins revealed that the predicted protein contains two conserved domains, an N-terminal CRAL/TRIO domain and a C-terminal GOLD domain (Figure 2A). The CRAL/TRIO domain was named for the cis-retinaldehyde binding protein and the Trio multidomain protein (Bateman et al. 2000). It forms a hydrophobic binding pocket that binds ligands such as retinaldehyde or phosphatidylinositol (Sha et al. 1998; Stocker et al. 2002; Stocker and Baumann 2003). The GOLD domain was identified by protein alignments and it forms a β-barrel (Anantharaman and Aravind 2002; Stocker et al. 2002). We named the T27A10.7 gene cgr-1 for CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domain suppressor of activated ras.

To characterize evolutionary conservation of this protein family, we identified human, mouse, Drosophila, and nematode predicted proteins that contain a CRAL/TRIO and a GOLD domain and constructed a neighbor-joining phylogeny (Figure 2C). There are four such proteins encoded by the genomes of C. elegans and the related nematode C. briggsae. The phylogeny shows that CGR-1 has diverged to a similar extent from the vertebrate SEC14-1 and SPF/SEC14-3 proteins. However, C. elegans T23G5.2 is closely related to the SEC14-1 proteins, and all five proteins in this branch contain a similar N-terminal extension. CGR-1 and the SPF/SEC14-3 proteins lack this N-terminal extension, suggesting that they may be more closely related.

Identification of a cgr-1 deletion mutation:

To obtain a null mutation of cgr-1, we took advantage of our molecular analysis by screening for a deletion in the cgr-1 locus (see materials and methods). We identified one allele, cgr-1(am114), containing a deletion of 2.2 kb that begins in intron 3, removes exons 4–8, and ends in intron 8 (Figure 2). The deleted region encodes most of the CRAL/TRIO domain and approximately half of the GOLD domain, suggesting that am114 is likely a null mutation.

cgr-1 positively regulates Ras signaling and is necessary for ectopic vulval cell fates induced by let-60 and lin-15 but not by lin-1, lin-31, or lin-12:

cgr-1(n2528) reduced the penetrance of the Muv phenotype caused by let-60(n1046) from 71 to 4% (Table 1, rows 2 and 3). To determine if the suppression of the Muv phenotype is caused by a change of cell fates, we used Nomarski optics to analyze the number of Pn.p cells that adopt vulval fates. Wild-type hermaphrodites displayed an average of 3.0 induced Pn.p cells, since P5.p, P6.p, and P7.p adopt vulval cell fates whereas P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p adopt nonvulval cell fates (Table 1, row 1). let-60(n1046) increased the number of induced Pn.p cells to 4.3 (Table 1, line 2). let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528) hermaphrodites displayed an average of 3.0 induced Pn.p cells (Table 1, line 3). The cgr-1(am114) deletion allele exhibited similar interactions with let-60. let-60(n1046); cgr-1(am114) hermaphrodites displayed a Muv penetrance of <1% and an average of 3.0 induced Pn.p cells (Table 1, row 4). These results indicated that cgr-1 is necessary for activated let-60 ras to induce ectopic vulval cell fates.

TABLE 1.

cgr-1 interactions with Muv mutations

| Genotype | % Muva | nb | Induced Pn.p cellsc | nb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 0 | 341 | 3.0 | 12 |

| let-60(n1046) | 71 | 362 | 4.3 | 10 |

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528) | 4 | 388 | 3.0 | 10 |

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(am114) | <1 | 376 | 3.0 | 10 |

| let-60(ga89)d | 19 | 308 | NDe | — |

| let-60(ga89); cgr-1(n2528)d | 2 | 293 | ND | — |

| lin-15(n765) | 99 | 150 | ND | — |

| cgr-1(n2528) lin-15(n765)f | 7 | 174 | ND | — |

| lin-1(n383) | 100 | 415 | 5.3 | 10 |

| lin-1(n383); cgr-1(n2528) | 99 | 504 | 5.3 | 10 |

| lin-1(n383); cgr-1(am114) | 100 | 356 | 5.2 | 10 |

| lin-31(n1053) | 73 | 356 | ND | — |

| lin-31(n1053); cgr-1(n2528) | 57 | 188 | ND | — |

| lin-12(n137) | 100 | 151 | ND | — |

| lin-12(n137); cgr-1(n2528)g | 100 | 153 | ND | — |

| let-60(n1046)h | 33 | 193 | ND | — |

| let-60(n1046); amEx57hi | 89 | 220 | ND | — |

The multivulva (Muv) phenotype, defined as one or more protrusions along the ventral cuticle that are displaced from the normal location of the vulva, was scored using a dissecting microscope.

Number of hermaphrodites analyzed.

Fourth larval stage (L4) hermaphrodites were examined using Nomarski optics. The Pn.p cells, P3.p–P8.p, were classified as induced if they appeared to have produced more than two descendants.

Hermaphrodites were analyzed at 25° to increase the penetrance of the ga89 Muv phenotype.

Not determined.

Complete genotype: cgr-1(n2528) lon-2(e678) lin-15(n765).

Complete genotype: lin-12(n137); cgr-1(n2528) lon-2(e678).

Hermaphrodites were analyzed at 15° to reduce the penetrance of the n1046 Muv phenotype.

The amEx57 extrachromosomal array consists of multiple copies of pJG1 (Pcgr-1/cgr-1 genomic DNA) and the transformation marker pRF4. Four transgenic lines were generated; these data are from one representative line.

To determine if cgr-1 mutations have allele-specific interactions with let-60(n1046), we analyzed a different mutation, let-60(ga89), that results in a L19F substitution. The ga89 missense mutation causes a gain-of-function at high temperatures and a loss-of-function at low temperatures (Eisenmann and Kim 1997). cgr-1(n2528) strongly suppressed the gain-of-function Muv phenotype caused by let-60(ga89) at 25° (Table 1, rows 5 and 6). This indicates that the cgr-1 phenotype is independent of the specific mutation that activates let-60 ras.

To test if cgr-1 interacts with other genes that control induction of vulval cell fates, we examined the interaction of cgr-1 with lin-15, lin-1, lin-31, and lin-12. lin-15 is a complex locus that encodes two novel proteins that function in the synthetic Multivulva pathway (Clark et al. 1994; Huang et al. 1994). Loss-of-function mutations in lin-15 cause a Muv phenotype, and genetic epistasis experiments indicate that lin-15 acts downstream of the lin-3 epidermal growth factor ligand and upstream of the let-23 receptor tyrosine kinase and let-60 ras (Sternberg et al. 1992). cgr-1(n2528) suppressed the lin-15(n765) Muv phenotype from 99 to 7% at 20° (Table 1, rows 7 and 8). Thus, cgr-1 is necessary for the ectopic vulval cell fates induced by a loss of lin-15.

lin-1 encodes an ETS-domain transcription factor that inhibits the primary vulval cell fate and functions downstream of mpk-1 (Beitel et al. 1995). The strong loss-of-function lin-1(n383) mutation causes a highly penetrant Muv phenotype with an average of 5.3 induced Pn.p cells (Table 1, row 9). The cgr-1(n2528) and cgr-1(am114) mutations did not significantly affect the Muv phenotype or the ectopic induction of vulval cell fates caused by lin-1(n383) (Table 1, rows 10 and 11). The lin-31 gene encodes a predicted transcription factor that contains an HNF-3 forkhead domain and appears to act at the level of lin-1 to regulate vulval cell fates (Miller et al. 1993). The strong loss-of-function lin-31(n1053) mutation causes a Muv phenotype with a penetrance of 73% (Table 1, row 12). The cgr-1(n2528) mutation only slightly reduced the Muv phenotype caused by lin-31(n1053) (Table 1, row 13). Thus, cgr-1 is not necessary for the ectopic vulval cell fates caused by a loss of lin-1 and lin-31.

The activity of the lin-12 Notch gene causes P5.p and P7.p to adopt 2° vulval cell fates (Yochem et al. 1988). The lin-12(n137) gain-of-function mutation causes a Muv phenotype because all six Pn.p cells adopt secondary vulval cell fates (Greenwald and Seydoux 1990). cgr-1(n2528) did not affect the Muv phenotype caused by lin-12(n137) (Table 1, rows 14 and 15). Thus, cgr-1 is not necessary for the ectopic 2° vulval cell fate induced by activated lin-12.

The result that cgr-1 loss-of-function mutations suppress the Muv phenotype caused by mutations of let-60 ras and lin-15 indicates that cgr-1 activity promotes Ras signaling. If this is the case, then overexpression of cgr-1 might enhance Ras signaling. To test this prediction, we generated transgenic animals that contain multicopy arrays of the wild-type cgr-1 genomic DNA locus. In a wild-type genetic background overexpression of cgr-1 did not significantly affect vulval development. In let-60(n1046gf) hermaphrodites, overexpression of cgr-1 increased the penetrance of Muv from 33 to 89% at 15° (Table 1, rows 16 and 17). This result demonstrates that cgr-1 is sufficient to promote Ras-mediated signaling in a sensitive genetic background and provides additional evidence that cgr-1 positively regulates Ras signaling.

cgr-1 promotes vulval cell fates in P5.p, P6.p, and P7.p:

In an otherwise wild-type background, cgr-1 mutations caused an egg-laying defect that was 4% penetrant, indicating that most mutant hermaphrodites formed a functional vulval passageway (Table 2, rows 2 and 3). These mutants displayed 22 descendants of P5.p, P6.p, and P7.p, indicating that the vulval cell lineages are frequently normal. To determine if cgr-1 mutations affect the fates of P5.p–P7.p in sensitized genetic backgrounds, we constructed double mutants containing cgr-1(am114) and a mutation that partially reduces Ras-mediated signaling. The lin-45 raf gene is necessary for all Ras-mediated signaling, since strong loss-of-function mutations in lin-45 cause a highly penetrant vulvaless phenotype (Han et al. 1993; Hsu et al. 2002). We previously identified the partial loss-of-function allele lin-45 (n2520) as a suppressor of let-60 ras (Hsu et al. 2002). In an otherwise wild-type genetic background, lin-45(n2520) does not cause an egg-laying defect or affect the lineages of P5.p–P7.p (Table 2, row 4). The lin-45(n2520); cgr-1(am114) double-mutant strain displayed an egg-laying defect that was 31% penetrant and a reduction in the average number of P5.p–P7.p descendants (Table 2, row 5). The gene sur-8 encodes a leucine-rich repeat protein that binds Ras and promotes Ras-mediated signaling (Sieburth et al. 1998). The sur-8(ku167) partial reduction-of-function mutation causes an egg-laying defect that is 2% penetrant and does not affect the cell lineages of P5.p–P7.p in an otherwise wild-type genetic background (Table 2, row 6). sur-8(ku167); cgr-1(am114) double-mutant hermaphrodites displayed an egg-laying defect that was 28% penetrant and a reduction in the average number of P5.p–P7.p descendants that was 80% penetrant (Table 2, row 7). Thus, in these sensitized genetic backgrounds cgr-1 is necessary for P5.p–P7.p to generate normal vulval cell lineages.

TABLE 2.

cgr-1 interactions with Vul mutations

| Genotype | % egg-laying defectivea | nb | P5.p–P7.p descendants (range)c | % animals with 22 P5p–P7.p descendants | nb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1 | 142 | 22 (22) | 100 | 12 |

| cgr-1(n2528)d | 4 | 156 | 22 (22) | 100 | 10 |

| cgr-1(am114)e | 4 | 306 | 22 (22) | 100 | 12 |

| lin-45(n2520)f | 0 | 188 | 22 (22) | 100 | 11 |

| lin-45(n2520); cgr-1(am114)g | 31 | 130 | 21 (18-22) | 64 | 11 |

| sur-8(ku167)h | 2 | 170 | 22 (22) | 100 | 10 |

| sur-8(ku167); cgr-1(am114)i | 28 | 125 | 20 (16-22) | 20 | 10 |

Eggs were placed on individual petri dishes, and worms were observed every 1–2 days. Worms were scored as egg-laying defective if they laid fewer than five eggs and produced viable progeny that hatched internally.

Number of hermaphrodites analyzed.

L4 stage hermaphrodites were examined using Nomarski optics, and the number of descendants of P5.p–P7.p was inferred from their position and morphology. The range represents the lowest and highest number of descendants counted in an individual animal.

Hermaphrodites were raised at 20° to analyze egg laying and at 15° to analyze P5.p–P7.p.

Complete genotype of hermaphrodites used to analyze P5.p–P7.p: cgr-1(am114) lon-2(e678).

Complete genotype of hermaphrodites used to analyze P5.p–P7.p: lin-45(n2520) unc-24(e138).

Complete genotype of hermaphrodites used to analyze P5.p–P7.p: lin-45(n2520) unc-24(e138); cgr-1(am114) lon-2(e678).

Complete genotype of hermaphrodites used to analyze P5.p–P7.p: sur-8(ku167) dpy-20(e1282).

Complete genotype of hermaphrodites used to analyze P5.p–P7.p: sur-8(ku167) dpy-20(e1282); cgr-1(am114) lon-2(e678).

cgr-1 is required for larval development:

In addition to vulval defects, cgr-1 mutants exhibited other abnormalities including a slightly dumpy appearance, a small increase in the amplitude of body bends, a propensity to spend time away from the lawn of E. coli on the petri dish, delays in larval development, and larval lethality. To characterize the abnormalities during larval development, we placed one egg on a petri dish and monitored larval development using a dissecting microscope. cgr-1(n2528) mutants displayed a larval lethal phenotype that was cold sensitive: 8% of these mutants died at 20° whereas 49% died at 15° (Table 3, row 2). For the cgr-1(n2528) mutants that developed into fertile adults, ∼90% experienced some developmental delay during the larval stages, and we observed mutants that were L1 or L2 larvae for 8–10 days before developing into fertile adults. cgr-1(am114) mutants displayed a higher-penetrance larval lethal phenotype that was also cold sensitive: 12% of these mutants died at 20° whereas 100% died at 15° (Table 3, row 3). The time until larval death was highly variable; ∼10% of cgr-1(am114) mutants died as L1 larvae within 3 days and 75% persisted as L1 or L2 larvae for >10 days.

TABLE 3.

cgr-1 mutations cause larval lethality

| Genotype | % larval lethala at 20° | nb | % larval lethala at 15° | nb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1 | 142 | 1 | 275 |

| cgr-1(n2528) | 8 | 57 | 49 | 162 |

| cgr-1(am114) | 12 | 206 | 100 | 248 |

| cgr-1(RNAi)c | 1 | 842 | 26d | 983 |

| mpk-1(n2521) | 11 | 137 | — | — |

| mpk-1(n2521); cgr-1(am114)e | 100 | 44 | — | — |

| let-60(n1046) | NDf | — | 5 | 129 |

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528) | 9 | 47 | 15 | 153 |

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(am114) | ND | — | 73 | 145 |

| lin-1(n383) | ND | — | 8 | 117 |

| lin-1(n383); cgr-1(am114) | ND | — | 100 | 171 |

Eggs were placed on individual petri plates, and worms were examined every 1–2 days. A worm was scored as larval lethal if it died during the L1–L4 stages or persisted in these larval stages for >14 days.

Number of hermaphrodites analyzed.

Wild-type N2 hermaphrodites were injected with cgr-1 double-stranded RNA. To analyze progeny, we placed each hermaphrodite on a separate petri dish, transferred it to a fresh plate daily, and counted the number of eggs laid. Eggs that did not yield L4 stage larvae by day 4 at 20° or day 6 at 15° were scored as larval lethal.

The average of 11 independently injected hermaphrodites is shown. Individual results varied from 4 to 96%.

We analyzed self-progeny of mpk-1(n2521) dpy-17(e164); cgr-1(am114)/unc-78(e1217) lon-2(e678) hermaphrodites. Forty-four of 158 (28%) of the progeny did not develop to adulthood, and we inferred that these animals had the genotype cgr-1/cgr-1. Forty of 158 (25%) of the progeny were Unc Lon, indicating that they had the genotype unc-78 lon-2/unc-78 lon-2. Fifty-five of 158 (35%) of the progeny segregated Unc Lon self-progeny, indicating that they had the genotype cgr-1/unc-78 lon-2. Nineteen of 158 (12%) of the progeny were non-Lon Unc, sterile adults. On the basis of the expected segregation ration of 1:2:1, we inferred that these animals had the genotype cgr-1/unc-78 lon-2, although it is possible that some of these had the genotype cgr-1/cgr-1.

Not determined.

The function of many C. elegans genes can be reduced transiently by RNA interference (RNAi), using double-stranded RNA (Fire et al. 1998). To analyze cgr-1, we injected double-stranded cgr-1 RNA into the gonad of wild-type hermaphrodites and examined their progeny. cgr-1(RNAi) caused a cold-sensitive larval lethal phenotype with a penetrance of 1% at 20° and 26% at 15° (Table 3, row 4). cgr-1(RNAi) larvae displayed developmental delays and arrests that were similar to the defects caused by the cgr-1 mutations. These results support the model that cgr-1 promotes larval viability and provide additional evidence that n2528 and am114 cause a reduction of cgr-1 gene activity.

The core genes of the Ras-signaling pathway including lin-3, let-23, sem-5, let-341, let-60, lin-45, mek-2, and mpk-1 are necessary for the development of the excretory duct cell (Yochem et al. 1997). Strong loss-of-function mutations of these genes cause a larval lethal phenotype characterized by a rigid, rod-like morphology. By contrast, the cgr-1(lf) mutants do not display this rigid, rod-like morphology, but instead die as thin and scrawny larvae or persist as larvae for many days. To determine if cgr-1 function during larval development involves Ras-mediated signaling in the excretory duct cell and/or another cell, we analyzed interactions with Ras pathway genes. The let-60(n1046) allele partially rescued the larval lethality caused by cgr-1, reducing the cgr-1(am114) larval lethal phenotype from 100 to 73% and the cgr-1(n2528) larval lethal phenotype from 49 to 15% (Table 3, rows 8 and 9). mpk-1(n2521) is a partial loss-of-function mutation that causes only 11% larval lethality (Table 3, row 5) (Lackner et al. 1994). mpk-1(n2521) enhanced the penetrance of the cgr-1(am114) larval lethal phenotype from 12 to 100% at 20°; most double mutants displayed the arrested larval development characteristic of cgr-1 mutants and not the rigid, rod-like morphology characteristic of mutants with a defective excretory duct cell (Table 3, row 6). The LIN-1 ETS transcription factor is an important target of Ras signaling during the development of the excretory duct cell, and a loss-of-function mutation of lin-1 suppresses the larval lethal phenotype caused by a loss-of-function mutation in a core signaling gene, such as mek-2 (Kornfeld et al. 1995a). If cgr-1(lf) mutations cause larval lethality by reducing Ras signaling in the excretory duct cell, then the cgr-1 lethal phenotype might be suppressed by a loss-of-function mutation in lin-1. However, lin-1(n383) did not suppress the larval lethality caused by cgr-1(am114), since these double mutants displayed a larval lethal phenotype that was 100% penetrant (Table 3, row 11). The results that the cgr-1 larval lethal phenotype displayed interactions with let-60 and mpk-1 but not with lin-1 suggest that cgr-1 promotes larval viability by functioning in a signaling pathway that is distinct from the pathway that specifies the excretory duct cell. These results do not exclude the possibility that cgr-1 functions in the excretory duct cell and that part of the cgr-1 phenotype is caused by a defect in this cell.

CGR-1 expression pattern:

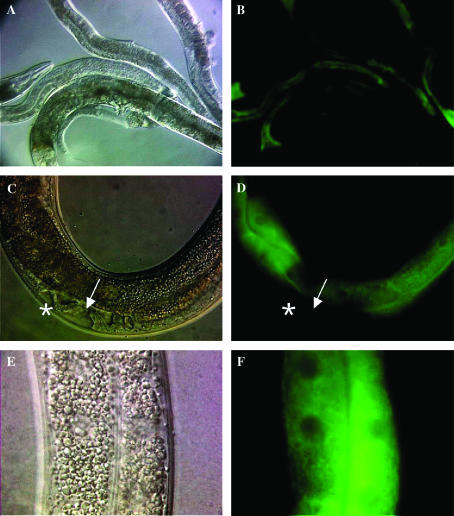

To investigate the expression pattern of CGR-1, we generated a plasmid that encodes a CGR-1:GFP fusion protein. To mimic the endogenous CGR-1 expression pattern, we used a 4.8-kb genomic DNA fragment that includes 1 kb of the cgr-1 promoter region and the complete cgr-1 coding region; the GFP coding region was inserted at the cgr-1 stop codon. Transgenic animals containing this plasmid displayed rescue of the cgr-1(n2528) suppression of Muv phenotype, indicating that the fusion protein is functional and that it is expressed in the cells that are necessary for cgr-1 function. CGR-1:GFP fluorescence was visible in the intestinal cells during all stages of development; it was not visible in Pn.p cells (Figure 3). The fluorescence signal in intestinal cells appears to be diffuse and cytosolic; it was largely excluded from the nucleus and was not concentrated at the periphery of the cell.

Figure 3.

Expression pattern of CGR-1. The genotype of all hermaphrodites was let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528); amEx82. The amEx82 array contains pDG125 (Pcgr-1:cgr-1 genomic:GFP) and pRF4. (A and B) Nomarski and fluorescent images (100×) of adult hermaphrodites. CGR-1:GFP expression is visible in intestinal cells. (C and D) Nomarski and fluorescent images (400×) of an L4 hermaphrodite. The arrow marks the vulva. The asterisk marks an ectopic vulval invagination. CGR-1:GFP expression is visible in intestinal cells but not in vulval cells. (E and F) Nomarski and fluorescent images (630×) of adult intestinal cells. CGR-1:GFP exhibits cytoplasmic localization and appears to be largely excluded from nuclei.

cgr-1 functions in Pn.p cells to mediate vulval induction:

The observation that CGR-1:GFP was not visible in Pn.p cells suggests that CGR-1 may be expressed in Pn.p cells at a level that is below the detection threshold of this assay or that CGR-1 may affect the fate of Pn.p cells by functioning in another cell type. To investigate the CGR-1 site of action, we used two tissue-specific promoters to express CGR-1: the ges-1 promoter that is expressed specifically in intestinal cells (Aamodt et al. 1991) and the lin-31 promoter that is expressed specifically in Pn.p cells (Tan et al. 1998). cgr-1 expression directed by the ges-1 promoter did not rescue the cgr-1(n2528) suppression of let-60(n1046) Muv phenotype (Table 4, rows 19 and 20). By contrast, cgr-1 expression directed by the lin-31 promoter partially rescued the cgr-1(n2528) phenotype (Table 4, rows 16–18). These results indicate that CGR-1 activity in Pn.p cells is sufficient to rescue the cgr-1 mutant defects in vulval development and suggest that CGR-1 normally functions cell autonomously in the Pn.p cells to promote induction of the primary vulval cell fate.

TABLE 4.

CGR-1 expression in transgenic animals

| Genotypea | cgr-1 expression construct | % Muvb | Nc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | None | 0 | 341 |

| let-60(n1046) | None | 71 | 362 |

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528) | None | 4 | 388 |

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528); amEx84 | Pcgr-1/CGR-1:GFP | 92 | 90 |

| 91 | 118 | ||

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528); amEx62 | Pcgr-1/CGR-1(P131L) | 68 | 117 |

| 47 | 100 | ||

| 47 | 74 | ||

| 26 | 86 | ||

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528); amEx89 | Pcgr-1/CGR-1 (K230A):GFP | 79 | 250 |

| 46 | 370 | ||

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528); amEx88 | Pcgr-1/CGR-1 (ΔGOLD):GFP | 63 | 295 |

| 52 | 367 | ||

| 48 | 446 | ||

| 38 | 397 | ||

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528); amEx90 | Plin-31/CGR-1:GFP | 49 | 222 |

| 40 | 264 | ||

| 21 | 213 | ||

| let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528); amEx91 | Pges-1/CGR-1:GFP | 10 | 118 |

| 9 | 206 |

Extrachromosomal arrays were obtained by coinjecting pRF4 and the following CGR-1 expression plasmids: amEx84, containing pDG135; amEx62, containing pJG3; amEx89, containing pDG147; amEx88, containing pDG146; amEx90, containing pDG149; and amEx91, containing pDG151 (described in materials and methods).

The Muv phenotype was scored as described in Table 1. Each value represents an independently derived transgenic strain. All adult hermaphrodites that displayed the Rol phenotype were scored on several petri dishes.

Number of hermaphrodites analyzed.

The CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domains are important for CGR-1 function:

The CRAL/TRIO domain of yeast SEC14 binds phosphatidylinositol (PI), and purified SEC14 displays PI transfer activity (Phillips et al. 1999). A lysine residue that is necessary for this activity is conserved in CGR-1 and corresponds to lysine 230 (Figure 2). To test the importance of CGR-1 lysine 230, we generated a plasmid that encodes mutant CGR-1 with a lysine 230-to-alanine substitution. The CGR-1(K230A) mutant partially rescued the cgr-1(n2528) suppression of Muv phenotype (Figure 4 and Table 4, rows 10 and 11). The cgr-1(n2528) mutation results in a proline 131-to-leucine substitution in the CRAL/TRIO domain. Our genetic studies indicated that this mutation partially reduces cgr-1 activity. In addition, expression of CGR-1(P131L) partially rescued the cgr-1 suppression of Muv phenotype (Figure 4 and Table 4, rows 6–9). The analysis of CGR-1(K230A) and CGR-1(P131L) mutants indicates that the CRAL/TRIO domain is necessary for the full function of CGR-1, although it is also possible that these mutations reduce protein stability. The residual activity of these proteins might result from residual function of the CRAL/TRIO domain or from CGR-1 functions that are independent of the CRAL/TRIO domain. To address this issue, we generated a plasmid-encoding CGR-1 protein with a deletion of the entire CRAL/TRIO domain. However, this construct could not be maintained in transgenic animals, perhaps because expression of the GOLD domain alone causes toxicity.

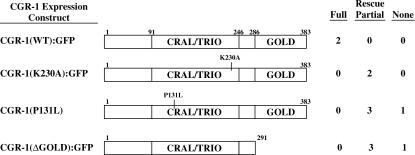

Figure 4.

Structure/function analysis of CGR-1. Transgenic strains that expressed the diagrammed CGR-1 protein and had the chromosomal genotype let-60(n1046); cgr-1(n2528) were assayed for rescue of the cgr-1 suppression of Muv phenotype. Extrachromosomal arrays are described in Table 4 and criteria for rescue are described in Figure 1.

To investigate the role of the GOLD domain, we constructed a plasmid that encodes mutant CGR-1 protein with a deletion of the entire GOLD domain. Expression of CGR-1(K292 Stop) partially rescued the cgr-1 suppression of Muv phenotype (Figure 4 and Table 4, rows 12–15). This result suggests that the GOLD domain is necessary for the full activity of CGR-1, although it is also possible that this mutation reduces protein stability. In addition, it indicates that some CGR-1 functions are independent of the GOLD domain.

DISCUSSION

The cgr-1(n2528) mutation was identified by using random chemical mutagenesis and a forward genetic screen. This strategy was chosen because it is a sensitive and unbiased approach to identify novel genes that mediate Ras signaling. Indeed, C. elegans cgr-1 and similar genes in other species have not been implicated previously in Ras signaling. Here we present genetic and molecular experiments demonstrating that CGR-1 promotes Ras-mediated signal transduction. These results identify a new protein that contributes to Ras-mediated signaling and demonstrate an in vivo function for a member of the evolutionarily conserved family of CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domain proteins.

cgr-1 positively regulates Ras-mediated signaling:

Several techniques were used to manipulate cgr-1 activity, and these studies indicate that cgr-1 positively regulates Ras signaling. Two cgr-1 chromosomal mutations were analyzed: the cgr-1(n2528) missense mutation and the cgr-1(am114) deletion mutation. Both cgr-1 mutations caused larval lethal and suppression of Muv phenotypes. They can be arranged in an allelic series, since am114 caused a higher penetrance of both phenotypes. The cgr-1 vulval phenotype was rescued by overexpression of wild-type cgr-1, and rescuing activity was diminished by introducing the n2528 mutation. These results suggest that n2528 causes a partial reduction of cgr-1 function and that am114 causes a larger and perhaps complete reduction of cgr-1 function. Consistent with this conclusion, double-stranded RNA interference, a technique that reduces gene function, phenocopied the cgr-1 larval lethal phenotype. In addition, overexpression of wild-type cgr-1 enhanced Ras-mediated signaling. These findings indicate that cgr-1 is necessary for the full activity of the Ras-mediated signaling pathway and that cgr-1 can be sufficient to promote Ras-mediated signaling. Our analysis also showed that Pn.p cells usually adopt a normal pattern of cell fates when a cgr-1 mutation is in an otherwise wild-type background. One possibility is that cgr-1 provides a function that is essential for Ras signaling but genes that are homologous to cgr-1 are partially redundant. Our analysis revealed three other C. elegans genes in the cgr-1 family; these genes have not been characterized, and they may be partially redundant with cgr-1. A second possibility is that cgr-1 function is important but not essential; the Ras signaling pathway may be robust enough to specify the vulval cell fates in many cases despite the absence of this positive regulator.

The genetic studies define a portion of the Ras signal transduction pathway that is likely to be the site of cgr-1 action. cgr-1(lf) mutations strongly suppressed the Muv phenotype caused by lin-15(lf) or let-60(gf) mutations. The lin-15(lf) phenotype is not efficiently suppressed by loss-of-function mutations in upstream signaling genes such as lin-3, and the let-60(gf) Muv phenotype is not efficiently suppressed by loss-of-function mutations in upstream signaling genes such as sem-5 (Ferguson et al. 1987; Clark et al. 1992; Sternberg et al. 1992). Thus, the suppression of these Muv phenotypes by cgr-1(lf) mutations indicates that cgr-1 functions downstream of lin-15 and let-60 if these genes function in a linear signaling pathway. The cgr-1(lf) mutations did not suppress the Muv phenotypes caused by lin-1(lf), lin-31(lf), or lin-12(gf) mutations. These results indicate that cgr-1 does not simply prevent execution of vulval cell fates and that cgr-1 functions upstream of lin-1, lin-31, and lin-12 if these genes function in a linear signaling pathway. The signal transduction pathway downstream of let-60 ras and upstream of lin-1 includes the core signaling genes lin-45 Raf, mek-2 MEK, and mpk-1 ERK and the positive modifiers ksr-1 and cdf-1. Our data do not establish the order of action of cgr-1 relative to these genes. These results are also consistent with the model that cgr-1 functions in parallel to the genes in the Ras pathway. For example, the induction of vulval cell fates is positively regulated by a Wnt signaling pathway that includes the positive regulator bar-1 and the negative regulator pry-1 (Eisenmann et al. 1998; Hoier et al. 2000; Gleason et al. 2002). The activity of this Wnt pathway positively regulates transcription of the lin-39 homeotic gene, which promotes vulval cell fates. If cgr-1 functions in parallel to the Ras signaling pathway, then it might promote Wnt signaling.

The suppression of the Muv phenotype caused by cgr-1(lf) mutations demonstrates that cgr-1 affects the cell fates of P3.p, P4.p, and P8.p. In two sensitized genetic backgrounds, cgr-1(lf) mutations caused a Vul phenotype characterized by a reduced number of descendants of P5.p, P6.p, and P7.p. Thus, cgr-1 affects the fates of all six Pn.p cells. To address whether cgr-1 acts cell autonomously in these Pn.p cells, we expressed cgr-1 in specific tissues. CGR-1 is highly expressed in intestinal cells, but specific expression in these cells did not affect vulval development. Expression in intestinal cells may mediate a different function of CGR-1. By contrast, CGR-1 expression in Pn.p cells was sufficient to promote vulval cell fates, indicating that cgr-1 acts cell autonomously in Pn.p cells. These findings are consistent with the model that cgr-1 functions in Pn.p cells to affect the signaling pathway at a step downstream of let-60 ras and upstream of the LIN-1 transcription factor.

An in vivo function for a CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domain protein:

A large number of proteins contain a CRAL/TRIO or a GOLD domain, often in combination with other conserved motifs. Here we focus on proteins that contain both motifs, since these are likely to share an ancestral gene and may have retained conserved functions. We used bioinformatic searches to identify proteins with both domains in vertebrates, insects, and nematodes, and we constructed a phylogeny for this protein family. These studies demonstrate that this protein family has been conserved during the evolution of multicellular animals. Only two of these proteins have been functionally characterized: supernatant protein factor (SPF) has been analyzed biochemically, and CGR-1 is described here. The other proteins are predicted on the basis of genomic DNA sequences and have not yet been characterized.

SPF was discovered because it stimulates conversion of squalene to lanosterol by liver microsomes (Tchen and Bloch 1957). Purified SPF can stimulates two enzymes, squalene epoxidase and squalene-2-3-oxide lanosterol cyclase (Ferguson and Bloch 1977; Caras and Bloch 1979). The mechanism of SPF has been investigated extensively but has not yet been fully defined. Purified SPF can facilitate squalene transfer between membranes, and it appears to enhance the availability of substrates to cholesterol biosynthetic enzymes. However, it does not bind squalene but rather binds anionic phospholipids (Caras et al. 1980).

The gene encoding SPF was recently cloned (Shibata et al. 2001), and the crystal structure was recently reported (Stocker et al. 2002). The structure of the CRAL/TRIO domain of SPF is similar to that of SEC14, and both form hydrophobic binding pockets that mediate binding to hydrophobic ligands (Sha et al. 1998). The GOLD domain forms an unusual eight-stranded jelly-roll barrel structure characteristic of viral proteins that bind to the outer surface of cell membranes (Stocker et al. 2002). The function of the GOLD domain is not well characterized. One possible function of the GOLD domain is suggested by an analysis of GCP-60. The GOLD domain of GCP-60 is necessary for binding to the Golgi resident protein, Giantin (Sohda et al. 2001), suggesting that the GOLD domain may mediate protein–protein interactions. SPF was independently identified on the basis of its ability to bind α-tocopherol and called tocopherol-associated protein (TAP) (Zimmer et al. 2000). However, the physiological significance of tocopherol binding is unclear. These enzymatic and structural studies of SPF complement the genetic and in vivo studies of CGR-1 and suggest intriguing possibilities for the biochemical mechanism of CGR-1.

CGR-1 is not likely to regulate cholesterol synthesis, like SPF, since C. elegans does not synthesize cholesterol and appears to lack the enzymes that are stimulated by SPF. However, the CRAL/TRIO and GOLD domains of CGR-1 are highly conserved and likely to adopt structures that are similar to SPF. Thus, CGR-1 is likely to contain a hydrophobic binding pocket and to interact with a hydrophobic ligand. Both Ras and Raf interact with lipids, and we speculate that CGR-1 might regulate signaling by affecting these interactions. Ras is membrane tethered by a lipid modification, and CGR-1 might affect the localization or membrane environment of Ras. Raf is recruited to the plasma membrane where it becomes activated by mechanisms that have yet to be fully defined. Raf can bind phospholipids such as phosphatidyl serine and phosphatidic acid, and these interactions may promote Raf activation (Ghosh et al. 1996; McPherson et al. 1999). CGR-1 might promote the activation of Raf by facilitating access to such a hydrophobic ligand. Although more studies are required to elucidate the mechanism of action of CGR-1, our results document that CGR-1 plays an important role in Ras-mediated signaling. This function may be conserved, and other members of the CGR-1 family may also regulate signal transduction.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Bob Horvitz for support and encouragement during the initiation of these studies. We thank members of the Kornfeld and Salkoff laboratories for assistance with deletion mutant libraries; Kara Sternhell for RNA analysis; V. Bankaitis, J. McGhee, S. Kim, and Y. Kohara for providing clones; and the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for providing strains. This work was supported by grants to K.K. from the National Institutes of Health and the Washington University/Pfizer Biomedical Program. K.K. is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

References

- Aamodt, E. J., M. A. Chung and J. D. McGhee, 1991. Spatial control of gut-specific gene expression during Caenorhabditis elegans development. Science 252: 579–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaman, V., and L. Aravind, 2002. The GOLD domain, a novel protein module involved in Golgi function and secretion. Genome Biol. 3: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbacid, M., 1987. ras genes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56: 779–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, A., E. Birney, R. Durbin, S. R. Eddy, K. L. Howe et al., 2000. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 28: 263–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitel, G. J., S. G. Clark and H. R. Horvitz, 1990. Caenorhabditis elegans ras gene let-60 acts as a switch in the pathway of vulval induction. Nature 348: 503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitel, G. J., S. Tuck, I. Greenwald and H. R. Horvitz, 1995. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene lin-1 encodes an ETS-domain protein and defines a branch of the vulval induction pathway. Genes Dev. 9: 3149–3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, S., 1974. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77: 71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma, J. J., T. Jirakulaporn, A. J. Muslin and K. Kornfeld, 2002. Zinc ions and cation diffusion facilitator proteins regulate Ras-mediated signaling. Dev. Cell 2: 567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caras, I. W., and K. Bloch, 1979. Effects of a supernatant protein activator on microsomal squalene-2,3-oxide-lanosterol cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 254: 11816–11821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caras, I. W., E. J. Friedlander and K. Bloch, 1980. Interactions of supernatant protein factor with components of the microsomal squalene epoxidase system. Binding of supernatant protein factor to anionic phospholipids. J. Biol. Chem. 255: 3575–3580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalfie, M., Y. Tu, G. Euskirchen, W. W. Ward and D. C. Prasher, 1994. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science 263: 802–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinen, K., E. Takahashi and Y. Nakamura, 1996. Isolation and mapping of a human gene (SEC14L), partially homologous to yeast SEC14, that contains a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) site in its 3′ untranslated region. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 73: 218–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S. G., M. J. Stern and H. R. Horvitz, 1992. Genes involved in two Caenorhabditis elegans cell-signaling pathways. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 57: 363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, S. G., X. Lu and H. R. Horvitz, 1994. The Caenorhabditis elegans locus lin-15, a negative regulator of a tyrosine kinase signaling pathway, encodes two different proteins. Genetics 137: 987–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, D. M., and S. K. Kim, 1997. Mechanism of activation of the Caenorhabditis elegans ras homologue let-60 by a novel, temperature-sensitive, gain-of-function mutation. Genetics 146: 553–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenmann, D. M., J. N. Maloof, J. S. Simske, C. Kenyon and S. K. Kim, 1998. The β-catenin homolog BAR-1 and LET-60 Ras coordinately regulate the Hox gene lin-39 during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Development 125: 3667–3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, E. L., P. W. Sternberg and H. R. Horvitz, 1987. A genetic pathway for the specification of the vulval cell lineages of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 326: 259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J. B., and K. Bloch, 1977. Purification and properties of a soluble protein activator of rat liver squalene epoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 252: 5381–5385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J., 1989. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5: 164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Fire, A., S. Xu, M. K. Montgomery, S. A. Kostas, S. E. Driver et al., 1998. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391: 806–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S., J. C. Strum, V. A. Sciorra, L. Daniel and R. M. Bell, 1996. Raf-1 kinase possesses distinct binding domains for phosphatidylserine and phosphatidic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 8472–8480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason, J. E., H. C. Korswagen and D. M. Eisenmann, 2002. Activation of Wnt signaling bypasses the requirement for RTK/Ras signaling during C. elegans vulval induction. Genes Dev. 16: 1281–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, I., and G. Seydoux, 1990. Analysis of gain-of-function mutations of the lin-12 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 346: 197–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, M., A. Golden, Y. Han and P. W. Sternberg, 1993. C. elegans lin-45 raf gene participates in let-60 ras-stimulated vulval differentiation. Nature 363: 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoier, E. F., W. A. Mohler, S. K. Kim and A. Hajnal, 2000. The Caenorhabditis elegans APC-related gene apr-1 is required for epithelial cell migration and Hox gene expression. Genes Dev. 14: 874–886. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, V., C. L. Zobel, E. J. Lambie, T. Schedl and K. Kornfeld, 2002. Caenorhabditis elegans lin-45 raf is essential for larval viability, fertility and the induction of vulval cell fates. Genetics 160: 481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L. S., P. Tzou and P. W. Sternberg, 1994. The lin-15 locus encodes two negative regulators of Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Mol. Biol. Cell 5: 395–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, J., and K. Kornfeld, 1999. A local, high-density, single-nucleotide polymorphism map used to clone Caenorhabditis elegans cdf-1. Genetics 153: 743–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohara, Y., 1996. Large scale analysis of C. elegans cDNA. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso 41: 715–720 (in Japanese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld, K., 1997. Vulval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Genet. 13: 55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld, K., K. L. Guan and H. R. Horvitz, 1995. a The Caenorhabditis elegans gene mek-2 is required for vulval induction and encodes a protein similar to the protein kinase MEK. Genes Dev. 9: 756–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornfeld, K., D. B. Hom and H. R. Horvitz, 1995. b The ksr-1 gene encodes a novel protein kinase involved in Ras-mediated signaling in C. elegans. Cell 83: 903–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner, M. R., K. Kornfeld, L. M. Miller, H. R. Horvitz and S. K. Kim, 1994. A MAP kinase homolog, mpk-1, is involved in ras-mediated induction of vulval cell fates in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 8: 160–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, R. A., A. Harding, S. Roy, A. Lane and J. F. Hancock, 1999. Interactions of c-Raf-1 with phosphatidylserine and 14–3-3. Oncogene 18: 3862–3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello, C. C., J. M. Kramer, D. Stinchcomb and V. Ambros, 1991. Efficient gene transfer in C. elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 10: 3959–3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L. M., M. E. Gallegos, B. A. Morisseau and S. K. Kim, 1993. lin-31, a Caenorhabditis elegans HNF-3/fork head transcription factor homolog, specifies three alternative cell fates in vulval development. Genes Dev. 7: 933–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, L. M., H. A. Hess, D. B. Doroquez and N. M. Andrews, 2000. Null mutations in the lin-31 gene indicate two functions during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Genetics 156: 1595–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, S. E., B. Sha, L. Topalof, Z. Xie, J. G. Alb et al., 1999. Yeast Sec14p deficient in phosphatidylinositol transfer activity is functional in vivo. Mol. Cell 4: 187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle, D. L., T. Blumenthal, B. J. Meyer and J. R. Priess, 1997. C. Elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY. [PubMed]

- Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch and T. Maniatis, 1989. Molecular Cloning. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY.

- Sha, B., S. E. Phillips, V. A. Bankaitis and M. Luo, 1998. Crystal structure of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae phosphatidylinositol-transfer protein. Nature 391: 506–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, N., M. Arita, Y. Misaki, N. Dohmae, K. Takio et al., 2001. Supernatant protein factor, which stimulates the conversion of squalene to lanosterol, is a cytosolic squalene transfer protein and enhances cholesterol biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 2244–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth, D. S., Q. Sun and M. Han, 1998. SUR-8, a conserved Ras-binding protein with leucine-rich repeats, positively regulates Ras-mediated signaling in C. elegans. Cell 94: 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieburth, D. S., M. Sundaram, R. M. Howard and M. Han, 1999. A PP2A regulatory subunit positively regulates Ras-mediated signaling during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction. Genes Dev. 13: 2562–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N., and M. Han, 1995. sur-2, a novel gene, functions late in the let-60 ras-mediated signaling pathway during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction. Genes Dev. 9: 2251–2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohda, M., Y. Misumi, A. Yamamoto, A. Yano, N. Nakamura et al., 2001. Identification and characterization of a novel Golgi protein, GCP60, that interacts with the integral membrane protein giantin. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 45298–45306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnhammer, E. L., S. R. Eddy and R. Durbin, 1997. Pfam: a comprehensive database of protein domain families based on seed alignments. Proteins 3: 405–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, P. W., and M. Han, 1998. Genetics of RAS signaling in C. elegans. Trends Genet. 14: 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, P. W., R. J. Hill, G. Jongeward, L. S. Huang and L. Carta, 1992. Intercellular signaling during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 57: 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, A., and U. Baumann, 2003. Supernatant protein factor in complex with RRR-alpha-tocopherylquinone: a link between oxidized vitamin E and cholesterol biosynthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 332: 759–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, A., T. Tomizaki, C. Schulze-Briese and U. Baumann, 2002. Crystal structure of the human supernatant protein factor. Structure 10: 1533–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram, M., and M. Han, 1995. The C. elegans ksr-1 gene encodes a novel Raf-related kinase involved in Ras-mediated signal transduction. Cell 83: 889–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P. B., M. R. Lackner and S. K. Kim, 1998. MAP kinase signaling specificity mediated by the LIN-1 Ets/LIN-31 WH transcription factor complex during C. elegans vulval induction. Cell 93: 569–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchen, T. T., and K. Bloch, 1957. On the conversion of squalene to lanosterol in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 226: 921–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin and D. G. Higgins, 1997. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24: 4876–4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y., and M. Han, 1994. Suppression of activated Let-60 ras protein defines a role of Caenorhabditis elegans Sur-1 MAP kinase in vulval differentiation. Genes Dev. 8: 147–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y., M. Han and K. L. Guan, 1995. MEK-2, a Caenorhabditis elegans MAP kinase kinase, functions in Ras-mediated vulval induction and other developmental events. Genes Dev. 9: 742–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochem, J., K. Weston and I. Greenwald, 1988. The Caenorhabditis elegans lin-12 gene encodes a transmembrane protein with overall similarity to Drosophila Notch. Nature 335: 547–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yochem, J., M. Sundaram and M. Han, 1997. Ras is required for a limited number of cell fates and not for general proliferation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17: 2716–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder, J. H., H. Chong, K. L. Guan and M. Han, 2004. Modulation of KSR activity in Caenorhabditis elegans by Zn ions, PAR-1 kinase and PP2A phosphatase. EMBO J. 23: 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, S., A. Stocker, M. N. Sarbolouki, S. E. Spycher, J. Sassoon et al., 2000. A novel human tocopherol-associated protein: cloning, in vitro expression, and characterization. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 25672–25680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]