Abstract

Primary insults to the brain can initiate glutamate release that may result in excitotoxicity followed by neuronal cell death. This secondary process is mediated by both N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA receptors in vivo and requires new gene expression. Neuronal cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) expression is upregulated following brain insults, via glutamatergic and inflammatory mechanisms. The products of COX2 are bioactive prostanoids and reactive oxygen species that may play a role in neuronal survival. This study explores the role of neuronal COX2 in glutamate excitotoxicity using cultured cerebellar granule neurons (day 8 in vitro). Treatment with excitotoxic concentrations of glutamate or kainate transiently induced COX2 mRNA (two- and threefold at 6 h, respectively, p < 0.05, Dunnett) and prostaglandin production (five- and sixfold at 30 min, respectively, p < 0.05, Dunnett). COX2 induction peaked at toxic concentrations of these excitatory amino acids. Surprisingly, NMDA, l-quisqualate, and trans-ACPD did not induce COX2 mRNA at any concentration tested. The glutamate receptor antagonist NBQX (5 μM, AMPA/kainate receptor) completely inhibited kainate-induced COX2 mRNA and partially inhibited glutamate-induced COX2 (p < 0.05, Dunnett). Other glutamate receptor antagonists, such as MK-801 (1 μM, NMDA receptor) or MCPG (500 μM, class 1 metabotropic receptors), partially attenuated glutamate-induced COX2 mRNA. These antagonists all reduced steady-state COX2 mRNA (p < 0.05, Dunnett). To determine whether COX2 might be an effector of excitotoxic cell death, cerebellar granule cells were pretreated (24 h) with the COX2-specific enzyme inhibitor, DFU (5,5-dimethyl-3-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-(4-methyl-sulphonyl) phenyl-2(5H)-furanone) prior to glutamate challenge. DFU (1 to 1000 nM) completely protected cultured neurons from glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity. Approximately 50% protection from NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity, and no protection from kainate-mediated neurotoxicity was observed. Therefore, glutamate-mediated COX2 induction contributes to excitotoxic neuronal death. These results suggest that glutamate, NMDA, and kainate neurotoxicity involve distinct excitotoxic pathways, and that the glutamate and NMDA pathways may intersect at the level of COX2.

Keywords: COX2 mRNA, glutamate, kainate, NMDA, metabotropic receptors, prostaglandins

INTRODUCTION

Many genes expressed in the central nervous system function differently than in the periphery. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2) is one such gene that has recently become the subject of intense investigation (Kaufmann et al., 1997; O'Banion et al., 1999). Normal brain COX2 protein is found primarily in neuronal cell bodies and dendrites of the neocortex, but not in glia or endothelial cells. The role of COX2 in neural development, maintenance, and pathology has not been well defined; however, a number of studies have revealed diverse functions for COX2 in the central nervous system. Prostaglandins, the products of COX2, mediate vasoreactivity, platelet aggregation, vascular permeability, and act as chemokines, via activation of G-protein–linked membrane receptors. Brain COX2 most likely plays a role in the regulation of the cerebral microcirculation (which behaves differently from other vascular beds), the febrile response (Simpson et al., 1994), as well as suggested roles in synaptic function (Vaughan, 1998), cell death, and survival (Walton et al., 1997).

During late prenatal development, brain COX2 expression is highly upregulated, presumably through glutamatergic mechanisms (Smith and DeWitt, 1996; Deauseault et al., 2000). While basal COX2 appears to be regulated by normal glutamatergic synaptic activity in the adult brain (Yamagata et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1995; Kaufmann et al., 1996; Adams et al., 1996; Marcheselli and Bazan, 1996), neuronal COX2 can also be transiently induced by kainate-or NMDA-receptor mediated stimulation in cultured cortical neurons (Yamagata et al., 1993; Marcheselli and Bazan, 1996; Tocco et al., 1997; Hewett et al., 2000).

Increased neuronal COX2 expression is also associated with neuropathology, including traumatic brain injury (TBI; Dash et al., 2000; Strauss et al., 2000), cerebral ischemia (Collaco-Moraes et al., 1996; Graham et al., 1996; Nogawa et al., 1997; Kong et al., 1997; Sanz et al., 1997; Walton et al., 1997; Kinouchi et al., 1999), spreading depression (Caggiano et al., 1996), and seizures (Wallace et al., 1998), as well as chronic neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (Pasinetti and Aisen, 1998). Brain injuries stimulate cortical and subcortical COX2 expression in neurons and glia (Yamagata et al., 1993; Walton et al., 1997; Nogawa et al., 1997; Nakayama et al., 1998; Hirst et al., 1999; Strauss et al., 2000). Little or no evidence has been reported on neuropathological changes in COX1, thromboxane, or prostacyclin synthases. We have hypothesized that prolonged elevation of COX2 expression, beyond the acute phase of injury, exacerbates neuropathology and neurological deficits. Prolonged elevations in COX2 gene expression may correlate with worse injuries.

Glutamate receptor stimulation has been shown to regulate COX2 expression, though the exact contribution of NMDA and non-NMDA receptors is not known. For example, it has been shown that NMDA induces COX2 mRNA in some systems (Yamagata et al., 1993; Kaufmann et al., 1996; Hewitt et al., 2000), while kainic acid induces COX2 in other systems (Tocco et al., 1997; Koistinaho et al., 1999; Baik et al., 1999). In addition, basal COX2 expression was not fully eliminated by the NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (Yamagata et al., 1993; Kaufmann et al., 1996; Bidmon et al., 2000).

COX2 has been implicated in the mechanism of cell death following brain injury; neuronal COX2 increases after brain injury, and COX2 inhibitors have beneficial effects on neuronal survival and outcome (Resnick et al., 1998; Dash et al., 2000). We have found that DFU, a COX2-specific inhibitor, improves functional recovery in a rat model of TBI (Strauss and Jacobowitz, 1993). Cultures enriched in rat cerebellar granule cells are glutamatergic neurons that have been extensively characterized (Gallo et al., 1987). These neurons express all of the glutamate receptors and are relatively homogeneous (95%). They are susceptible to the excitotoxic effects of glutamate or kainate, acting on NMDA or AMPA/kainate receptors, respectively on day 8 in vitro (Marini and Paul, 1992; Marini et al., 1999). Here we provide evidence that the COX2 inhibitor DFU protects neurons from glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity in cerebellar granule neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Granule cells were prepared from postnatal day 8 Sprague-Dawley rat pups. Briefly, meninges-free cerebella were minced and recovered by centrifugation. The pellets from 20 cerebella were subjected to trypsinization, followed by inactivation of the trypsin by the addition of soybean trypsin inhibitor. Cells were then dissociated by a series of triturations and recovered by centrifugation. The final pellet was reconstituted in basal Eagle's medium containing glutamine (2 mM). No antibiotics were added, and the plating density was 1.8 × 106 cells/mL in Nunc® culture dishes. Cytosine arabinoside (10 μM) was added 18–24 h later to inhibit the proliferation of nonneuronal constituents. On day 7 in vitro, glucose (3.3 mM) was added to maintain survival. The culture medium was not replaced throughout the culture period (Marini and Paul, 1992). Granule cell neurons were used on day 8 in vitro for all experiments unless otherwise specified.

Exposure of Cerebellar Granule Cells to Drugs and Neurotoxins

Glutamate, kainate, NMDA, l-quisqualate, and trans-1-amino-cyclopentane-1,3-dicarboxylic acid (trans-ACPD) were the glutamatergic agonists used. The following drugs were added for the indicated time prior to neurotoxin exposure: 1 μM (±)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5Hdibenzo[a,d]cyclohepte n-5,10-imine maleate (MK-801), 500 μM d-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG), 5 μM 6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo(f)quinoxaline-2,3-dion e (NBQX), and 0.1–1000 nM 5,5-dimethyl-3-(3-fluorophenyl)-4-(4-methylsulphonyl) phenyl-2(5H)-furanone (DFU; Merck, Rahway, NJ). Drugs were dissolved at ≥100 times working concentrations in either sterile water or dimethyl sulfoxide. MK-801 was added 5 min prior, whereas NBQX and MCPG were added 30 min prior to the addition of excitotoxic amino acids. DFU was added 24 h prior to addition of excitotoxic amino acids. Glutamate, NMDA, kainic acid, NK-801, MCPG, quisqualic acid, trans-ACPD, and NBQX were purchased from Sigma-RBI (St. Louis, MO).

Determination of Prostaglandins in Cultured Neurons

On day 8 in vitro, the serum-containing culture medium was removed and replaced with Basal Medium Eagle containing 2 mM glutamine (serum-free medium). The neurons were equilibrated in serum-free medium for 1 h followed by the addition of an excitotoxic concentration of glutamate (100 μM) or kainate (500 μM). Aliquots (5% total) of serum-free medium were collected, immediately frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. Triplicate cultures were assayed in duplicate using EIA kits (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Media alone yielded results below the detection limit. The optimal procedures for prostaglandin measurements have been debated in the literature. Many investigators choose to examine prostaglandin production in the presence of exogenous arachidonic acid, however this approach is confounded by problems—e.g., the biological activity of the substrate itself (Kovalchuk et al., 1994). With the appearance of sensitive, double specificity enzyme-linked immunoassays (EIA; Cayman, Oxford, Assay Design Systems), we have measured de novo synthesized prostaglandins in serum-free medium. We were able to double the individual prostaglandin concentrations in these experiments by using half the volume of serum-free medium during the time of collection. Levels of total prostaglandins in untreated control cultures were well above the assay's limit of detection.

Determination of COX2 mRNA in Cultured Neurons

Quantitation of COX2 and cyclophilin mRNA via a lysate ribonuclease protection assay was achieved via scintillation counting of the excised bands (Strauss and Jacobwitz, 1993). At the indicated times, the culture medium was aspirated and the neurons were lysed with 5 M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.1 M EDTA, pH 8.0 (150 μL) at room temperature. The culture dishes were scraped and the cell lysates (≤107 cells/mL) were placed on dry ice and stored at −80°C. Each lysate (40μl) was directly combined with a solution (10 μL) containing excess syngeneic antisense COX2 and cyclophilin RNA probes (Strauss et al., 2000). Full-length 32P-labeled riboprobe transcripts were purified using polyacrylamide-urea gel electrophoresis and eluted in 0.5 M ammonium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% SDS (pH 6.3). Target mRNA/riboprobe hybrids formed overnight at 37°C were protected from ribonuclease degradation, and purified from background contaminants by organic extraction, ethanol precipitation, and nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Gels were dried between cellophane sheets, autoradiographed overnight and gel pieces containing the hybrids were excised using the autoradiogram as a guide. The radioactive decay, measured by scintillation counting, was converted to moles (via the specific activity) and to grams of mRNA (via the ratio of probe to message length) as described (Strauss and Jacobowitz, 1993). Two methods of normalization were used, comparison to total protein and to cyclophilin mRNA (CYC, a housekeeping gene) in the specimen.

Determination of Neuronal Viability

Cultured cerebellar granule cells were treated with each neurotoxin as described. After 24 h, the culture medium was removed and the cells were washed once with 1 mL of Locke's buffer (154 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 2.3 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 5.6 mM d-glucose, 86 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). The buffer was removed and replaced with 1 mL of Locke's buffer containing 5 μg/mL fluorescein diacetate and the dishes were placed in a 37°C water bath for 5 min. The viable fluorescein-positive neurons were detected using a Olympus fluorescence microscope. Fluorescein-positive neurons were counted in three representative fields. Each experiment was performed in triplicate with at least two different preparations of neurons. The ratio of fluorescein-positive neurons in treated dishes to untreated control dishes was expressed as percent neuronal survival.

Determination of Glutamate-Induced Apoptosis

Cultured rat cerebellar granule cells were exposed to an excitotoxic concentration of glutamate (100 μM) for 8–10 h on day 8 in vitro. The neurons were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and DNA fragmentation was determined using ApopTag (Oncor, Rockville, MD) with fluorescein diacetate according to the manufacturer's instructions. This method fluorescently labels the 3′-hydroxyl ends of fragmented DNA in situ. Total cell number was assessed by staining the fixed neurons with propidium iodide (PI, 1 μg/mL). A fluorescence microscope (Olympus; 100× objective) was used to count the apoptotic (fluorescein-positive) and total number of neurons (PI-positive) in three representative fields. Each experiment was performed in triplicate with at least two different preparations of neurons. The ratio of fluorescein-positive neurons to PI-positive counts was expressed as percent apoptosis.

Statistics

Values from experimental and control groups were averaged and compared using analysis of variance (p < 0.05 to reject the null hypothesis that the group means were equal). Post hoc analyses used the Dunnett test for comparison with control groups and the Scheffé test for other intergroup comparisons.

RESULTS

Glutamate and Kainate Induce COX2 Gene Expression in Cerebellar Granule Cells

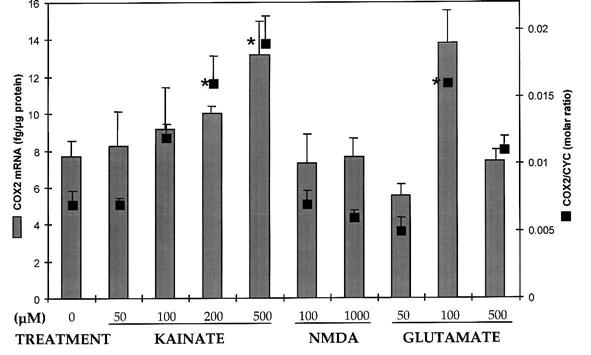

Exposure of cultured cerebellar granule cells to excitotoxic concentrations of glutamate and kainate, but not NMDA were associated with increases in COX2 mRNA (Fig. 1). Toxic concentrations of glutamate (100–500 μM) transiently increased COX2 mRNA expression at 1 h, 3 h (Fig. 1), and 6 h (Fig. 2) after treatment (p < 0.05, Dunnett), followed by a return to basal levels by 9 h. Glutamate (500 μM) induced COX2 at 3 h (not shown), but excessive cell death at 6 h probably reduced the number of viable cells. Kainate (200–500 μM) also transiently increased COX2 mRNA expression at 3 h (Fig. 1) and 6 h (Fig. 2) compared to untreated control neurons (p < 0.05, Dunnett). Addition of either subtoxic (100 μM) or toxic (1 mM) concentrations of NMDA did not result in a change in COX2 mRNA at any of the time points examined (Figs. 1 and 2). Treatment with the metabotropic agonists l-quisqualate (200, 500 μM) or trans-ACPD (100, 200 μM) may have decreased COX2 mRNA (50%), but did not reach statistical significance (not shown). At the earliest time points, no changes in total cellular protein or cyclophilin mRNA were detected. However, toxic concentrations of glutamate (≥100 μM) and kainate (≥200 μM), decreased cyclophilin expression beginning at 3 h and extending through 48 h (Fig. 1; p < 0.05, Dunnett).

FIG. 1.

COX2 mRNA was induced in cultured cerebellar neurons after 3-h treatment with toxic concentrations of glutamate (100 μM) or kainate (500 μM). COX2 mRNA was not affected by toxic concentrations of NMDA (1 mM). COX2 levels were normalized both by the cyclophilin mRNA (CYC) and the total protein in each sample. In this experiment, COX2 mRNA (fg/μg protein) levels were control 1.65 ± 0.67; glutamate 4.88 ± 1.14*; NMDA 2.77 ± 0.98; kainate 8.22 ± 2.29* (p < 0.05, Dunnett). Results are mean ± SEM (n = 3 per point). Controls levels were above the limit of quantitation (LOQ) of the assay. The LOQ was determined using nulls (ø, treated in every way similar to samples except the hybridization step was performed on dry ice): LOQ = (mean null value + 2 SEM).

FIG. 2.

Concentration-response of COX2 mRNA to excitotoxic amino acids. COX2 mRNA levels, quantified by two methods of normalization, were increased after 6-h exposure to toxic concentrations of glutamate and kainate, but not NMDA (bars: fg mRNA/μg protein; boxes: molar ratio of COX2 to CYC mRNA). The 500-μM glutamate treatment did not significantly increase COX2 mRNA, due possibly to excessive toxicity at 6 h. Results are mean ± SEM (n = 2–4 per point), *p < 0.05, Dunnett.

Glutamatergic Antagonists Differentially Affect Steady-State and Induced COX2 Gene Expression

The pharmacology of steady-state and excitotoxicity-induced COX2 expression was investigated using selective glutamatergic antagonists (Table 1). Decreased steady-state COX2 mRNA levels were observed following addition of MK-801 (1 μM), NBQX (5 μM), or MCPG (500 μM) to cultured cerebellar granule cells, suggesting a dependence on NMDA, AMPA/kainate and metabotropic receptor stimulation for basal expression. COX2 induction by glutamate (100 μM) was attenuated by MK-801 (−37%, p < 0.05, Scheffé). Glutamate-mediated COX2 induction was not significantly attenuated by NBQX (−8%) or MCPG (−14%), but a combination of the two did suppress COX2 mRNA induction (−25%, p < 0.05, Scheffé). Kainate-mediated COX2 induction was virtually blocked in the presence NBQX (−80%, p < 0.05, Scheffé).

Table 1.

COX2 mRNA Levels Are Modulated by Glutamate Receptor Antagonists

| Percent change |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (μM) | COX2/CYC(%) | +NBQX | +MCPG | +NBQX+MCPG | +MK801 |

| Control | 0.50 ± 0.10 | −40%a | −60%a | −60%a | −40%a |

| Glutamate (100) | 0.80 ± 0.05a | −8% | −14% | −25%b | −37%b |

| Kainate (500) | 1.04 ± 0.10a | −80%b | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

p < 0.05, Dunnett.

p < 0.05, Scheffé.

All assays were performed on DIV8 cultures (n = 3 per group) lysed 6 h after addition of agonists. Antagonists were added prior to agonists. Control denotes no agonist was added. Percentage change was calculated as value with antagonist divided by value without antagonist minus 100%.

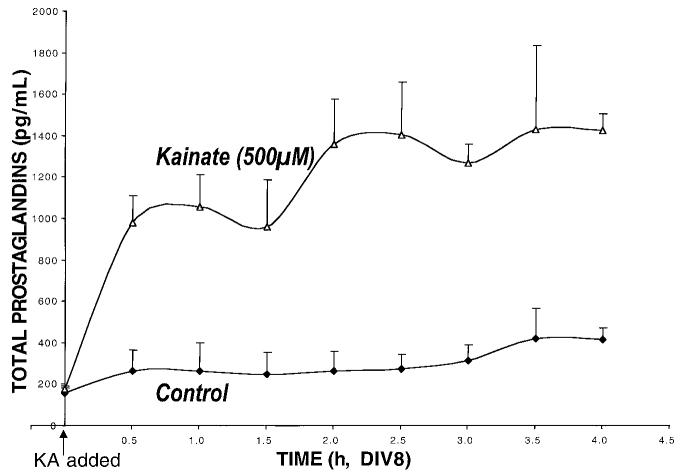

Endogenous COX2 Enzyme Activity Increases under Excitotoxic Conditions

Treatment of cerebellar granule cells with kainate (500 μM) induced a two-phase increase in the production of prostaglandins (Fig. 3). Initially, a rapid increase in total prostaglandins was observed (from 175 ± 17 to 982 ± 127 pg/mL at 30 min, p < 0.05, Dunnett), followed by a prolonged more gradual increase over the next several hours (to 1,422 ± 81 pg/mL by 6 h, p < 0.01, repeated measures, Dunnett). Prostaglandin E2 measured in these specimens demonstrated an increase from initially undetectable levels to 71 ± 12 pg/mL by 6 h, and thus could not account for the larger increase in total prostaglandins. No differences were observed in thromboxane B2 levels between control and glutamate-treated (100 μM) cultures (at 6 h, 298 ± 22 vs. 284 ± 10 pg/mL, respectively). The increase of total prostaglandin levels by an excitotoxic concentration of glutamate (100 μM) was substantially the same as kainate (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Total prostaglandin levels rise acutely after excitotoxic amino acid treatment. The time course of total prost-aglandin changes was analyzed by polynomial regression. The quadratic curve had a corellation coefficient r2 = 0.62 (p < 0.0003). This is consistent with a steady rise and fall of prostaglandin levels over the time course described. Cerebellar granule cells were incubated in serum-free medium, small aliquots (5% total) were collected, frozen and replaced with an equal volume of serum free medium (±kainate). Total prostaglandins were measured using an EIA (Cayman Chemical). Unfortunately, the colorimetric screening assay used has been discontinued and no suitable replacement could be found. The glutamate time course though incomplete, showed a slower rise with a lower peak than those from the kainate time course (not shown). Results are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 2 per time point).

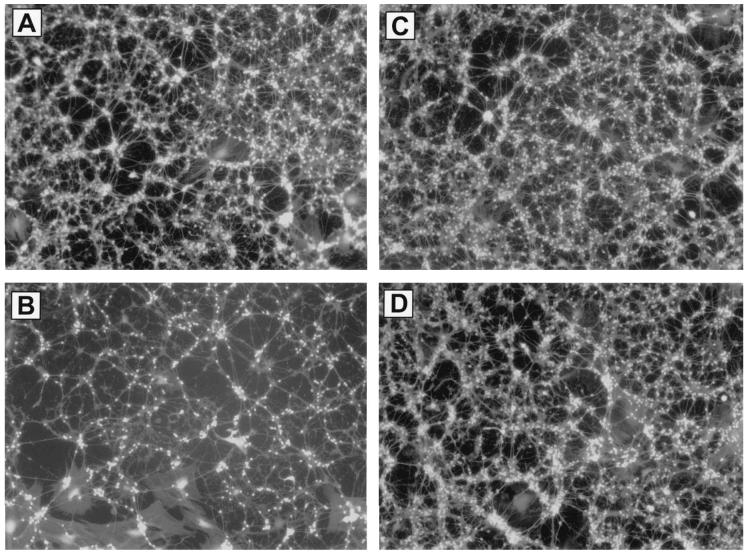

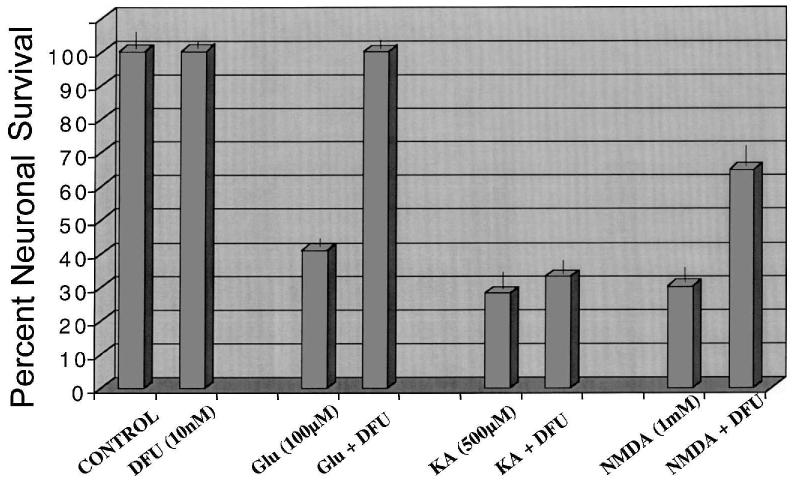

Glutamate-Mediated Neuronal Death Is Blocked by Inhibition of COX2 Enzyme Activity

The induction of COX2 in response to excess glutamate and kainate suggests a functional role for this enzyme in excitotoxicity. Glutamate (100 μM) caused ∼70% cell death at 24 h (compare Figs. 4A,B). Pretreatment with 10 nM DFU protected almost all of the vulnerable neurons from glutamate-mediated cell death (compare Figs. 4B vs. 4D and 4C vs. 4D). Total prostaglandin levels were halved in the DFU treated cultures (Table 2). DFU pretreatment, at a range of concentrations from 1nM to 1μM, was completely protective against glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity (Fig. 5). In addition, a cytochemical assay for DNA fragmentation revealed that DFU completely protected these neurons from glutamate-mediated apoptosis (Table 2). Surprisingly, the DFU-treated cells were still viable 3 days following glutamate addition, while 100% cell death had occurred in the control dishes (data not shown). Partial protection was observed (Fig. 6) following treatment with NMDA (2mM), while no protection was observed following treatment with kainate (500 μM).

FIG. 4.

The COX2 inhibitor DFU protects rat cerebellar granule neurons from glutamate-mediated cell death. (A) Untreated neurons. (B) Neurons treated with 100 μM glutamate. (C) Neurons pretreated (24 h) with 10 nM DFU. (D) Neurons pretreated with DFU and treated with 100 μM glutamate. Cultures were pretreated with DFU (10 nM) for 24 h. An excitotoxic concentration of glutamate (100 μM) was added, and neuronal viability was assessed 24 h later with fluorescein diacetate. Photos are representative fields from replicates (n = 3 dishes per group). Experiment was repeated three times with the same outcome.

Table 2.

DFU Blocks Glutamate-Induced Apoptosis in Cerebellar Granule Cells

| Treatment | Percent apoptosisa | Total prostaglandinb(pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Untreated cultures | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 59 ± 0.3 |

| Glutamate (100 μM) | 29.7 ± 1.8 | 426 ± 2 |

| DFU (10 nM) | 0.52 ± 0.07 | n.d. |

| Glutamate + DFU | 1.64 ± 1.28c | 218 ± 38c |

Cultured cerebellar granule cells were exposed to DFU for 24 h (day in vitro 7) followed by the addition of an excitotoxic concentration of glutamate (day in vitro 8) for 9 h. Apoptotic neurons were quantified by manually counting the number of fluorescein-positive neurons as described. Data are presented as percent apoptosis (mean ± SD).

Separate study (n = 2); total prostaglandin measured as described in Methods.

p < 0.001 versus glutamate, Scheffé.

FIG. 5.

The COX2 inhibitor DFU protects cultured neurons against glutamate neurotoxicity. Cultured cerebellar granule cells (day 7 in vitro) were treated with various concentrations of DFU (0.01–1000 nM) for 24 h followed by the addition of glutamate (100 μM) for an additional 24 h. Neuronal viability was assessed using the fluorescein diacetate assay as described in Materials and Methods. Percent neuronal survival is the ratio of viable neurons in DFU treated to untreated cultures ± SD.

FIG. 6.

DFU blocks glutamate-mediated cell death in cerebellar granule neurons. Cultures were pretreated with 10 nM DFU and exposed to 100 μM glutamate as described in Materials and Methods. Neuronal viability was determined with fluorescein diacetate as described in Figure 4. Results presented as percent survival (mean ± SEM).

DISCUSSION

Our data suggest that excitotoxic concentrations of glutamate and kainate (but not NMDA, l-quisqualate, or trans-ACPD) induced COX2 mRNA in cerebellar granule neurons, as well as increasing de novo prostaglandin production. The specific NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801, the kainic acid receptor antagonist, NBQX, and the class 1 metabotropic receptor antagonist MCPG partially blocked basal COX2 mRNA expression. Importantly, DFU protected the neurons from glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity and apoptosis, partially protected the neurons from NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity, and did not protect these neurons from kainate-mediated neurotoxicity. We hypothesize that glutamate-mediated induction of COX2 contributes to excitotoxic and apoptotic cell death, whereas kainate-mediated neuronal cell death involves a glutamatergic pathway that does not require COX2. Interestingly, while COX2 mRNA was not induced by NMDA, partial protection was afforded against NMDA toxicity, supporting a role for basal COX2 activity in glutamate-mediated neuronal death.

Steady-state COX2 expression may require stimulation of all three types of glutamate receptors. The combination of glutamate receptor antagonists NBQX (AMPA/kainate) and MCPG (metabotropic) did not additively reduce basal COX2 levels, an indication that steady-state COX2 levels may be regulated via a common pathway in these cells. Conversely, this combination did additively reduce the induction of COX2 by glutamate, suggesting separate mechanisms for basal and induced COX2 expression. None of these antagonists, even in combination, completely attenuated the glutamatergic induction of COX2 mRNA.

De novo prostaglandin production was accelerated during excitotoxic challenge, and PGE2 accounted for only a fraction of the increase. Thromboxane levels did not change. A two-staged increase of total prostaglandins was detected in response to kainate. This could be due to limited amounts of free arachidonic acid (e.g., through a transient rise in arachidonic acid availability due to phospholipase activation) or to a transient acceleration in COX2 enzyme activity. Our findings of continued COX2 mRNA induction between 2 and 6 h would support the first alternative.

Normal and excitotoxic concentrations of glutamate can modulate COX2 expression in the central nervous system (Yamagata et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1995; Kaufmann et al., 1996; Adams et al., 1996; Marcheselli and Bazan, 1996; Miettinen et al., 1997; Hirst et al., 1999; Candelario-Jalil et al., 2000); however, several studies have suggested different glutamate receptor–subtypes might be involved. These fall broadly into two categories: AMPA/kainate-mediated induction (Tocco et al., 1997; Koistinaho et al., 1999; Baik et al., 1999) and NMDA-mediated induction (Adams et al., 1996; Collaco-Moraes et al., 1996; Dolan and Nolan, 1999; Hewitt et al., 2000). One other study inferred a role for both NMDA and AMPA in the induction of COX2 (Chen et al., 1995). Hewett et al. (2000) recently showed that a toxic NMDA treatment induced COX2 mRNA in mixed cortical cultures. Interestingly, MK-801 was included in all their kainate experiments “to prevent NMDA receptor activation after the release of endogenous glutamate”; however, NBQX was not included with any of the NMDA experiments to prevent cross-talk with the AMPA/kainate receptor. It would have been most informative to determine whether NMDA-mediated COX2 induction occurred in the presence of NBQX.

Hewitt et al. (2000) also showed that NMDA excitotoxicity could be attenuated using COX2 inhibitors NS398 (COX2-specific) or flurbiprofen (mixed COX2/1), but not a COX1 inhibitor (valeryl salicylate). The NMDA-receptor blocker MK-801 reversed COX2 induction (as well, we assume, as subsequent glutamate release and neurotoxicity). In addition, NMDA-induced COX2 in the mixed cortical cultures was not specifically identified as being of neuronal origin. COX2 induction following injury was both neuronal as well as glial in origin (Hirst et al., 1999; Strauss et al., 2000). If glial uptake of excitotoxic amino acids were regulated by prostaglandins (Beaman-Hall et al., 1998), then glial COX2 might be involved in excitotoxicity. The results presented in this work might seem contradictory. However, the systems used to examine the role of COX2 were complementary. The cultured cortical and cerebellar neurons differed in their NMDA receptor subunit composition (Vallano et al., 1996). The present study looked at multiple glutamatergic agonists and antagonists with respect to COX2 induction, while Hewett et al. (2000) examined selected cyclooxygenase inhibitors and their effect on NMDA excitotoxicity. Total prostaglandin production followed the same time course in both studies. Both studies concluded that COX2 enzyme activity is involved in glutamate (NMDA)–mediated neuronal cell death and that kainate-mediated excitotoxicity is insensitive to COX2 inhibition. Obtaining a better understanding of neuronal COX2 gene regulation might lead to the development of novel therapies for glutamate-mediated neurotoxicity.

COX2 has been implicated as an effector of neurotoxicity in a number of neurodegenerative disorders. Inhibition of brain COX2 was beneficial to outcome both in vivo (Stevens and Yaksh, 1988; Buccellati et al., 1998; Nakayama et al., 1998; Nagayama et al., 1999; Dash et al., 2000; Strauss et al., in preparation) and in vitro (McGinty et al., 2000; Hewitt et al., 2000). Potentiation of glutamate and kainate excitotoxicity was observed in a strain of transgenic mice overexpressing neuronal COX2 (Kelley et al., 1999). In rats, kainate injections rapidly increased COX2 mRNA in forebrain, and levels were elevated for 24–72 h in brain regions that sustained the most apoptotic damage (Chen et al., 1995). We also observed prolonged overexpression of COX2 in brain regions associated with motor and cognitive deficits of traumatic brain injury (Strauss et al., 2000). COX2 inhibition improved neuronal survival in a rat model of global ischemia (Nakayama et al., 1998). And our recent findings demonstrate a significant relationship between inhibition of COX2 activity by DFU and functional recovery in a rat closed head injury model (Strauss et al., in preparation).

Interestingly, COX2 overexpression alone could not be directly associated with neurotoxicity. Two studies have demonstrated high levels of neuronal COX2 mRNA in the contralateral hippocampus where neuropathology did not seem to occur (Ho et al., 1999; Strauss et al., 2000). Viral coat protein–mediated neuronal apoptosis has been shown to be COX2 dependent (Bagetta et al., 1998; Maccarrone et al., 2000) and the mechanism hypothesized to involve “early derangement of the arachidonate cascade in favor of prostanoids” in rat neocortex (Maccarrone et al., 2000). In fact, Baik et al. (2000) showed that COX2 inhibition (celecoxib, NS398) exacerbated seizure activity and mortality following kainate-induced seizures that resulted in increased levels of prostaglandins D2, F2α, and E2 in the rat hippocampus. Also, McGinty et al. (2000) suggested that, in COX2-expressing PC12 cells, proapoptotoic capase-3 activity was reduced by prostaglandins. A thorough analysis of excitotoxicity-induced changes in prostaglandin production in primary neurons could be of importance in determining which arachidonic acid metabolites were active in the cell death pathways. Understanding the details of arachidonic acid metabolism may lead to new treatment paradigms in neurodegenerative diseases from Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases to cerebral vascular accidents and traumatic brain injury.

Paradoxically, COX2 in the periphery and in malignant cells demonstrated anti-apoptotic activity (vonKnethen et al., 1999; Hsueh et al., 2000). If COX2 was associated with both anti-apoptotic and neurotoxic actvi-ties, then the context in which this gene was expressed must be crucial to its function. The mechanisms of action of COX2 in any cell system would vary depending on the arachidonate-metabolic activities present under the specific conditions being investigated (Walton et al., 1997; Christie et al., 1999). NMDA has been shown to induce neuronal arachidonic acid release in a variety of primary neuronal cultures (Dumuis et al., 1988; Sanfeliu et al., 1990; Lazarewicz et al., 1988, 1990). Lazarewicz et al. (2000) showed that NMDA receptor activation stimulates prostaglandin D2 production in vivo. Cerebellar granule cells treated with DFU were differentially protected from glutamate, NMDA, and kainate excitotoxicity. Therefore, COX2 enzyme activity was implicated in glutamate-mediated cell death because inhibition is beneficial to the cells. There could be alternate explanations. If kainate-mediated neurotoxicity were dependent on, for example, lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid, then blockade of COX2 might actually shunt arachidonic acid toward an increase in lipoxygenase products, and cause more cell death. Indeed, the induction of COX2 following kainate treatment might be a protective mechanism (Baik et al., 1999). Thus, the efficacy of COX2 inhibitors in neuropathology (and the fate of released arachidonic acid) will be determined by the enzymes present or induced both upstream and downstream of COX2. We speculate that the effects of COX2 inhibitors may include the shunting of arachidonic acid toward the production of beneficial metabolites. For example, Node et al. (1999) have identified specific cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid that demonstrate antiinflammatory activity in heart muscle. Finally, the arachidonate derivative 2-arachidonoyl glycerol, an endogenous cannabinoid, has been shown to be neuroprotective in a mouse brain injury model (Panikashvilli et al., 2001).

Two important issues have also been raised: (1) Although glutamate and kainate both induce COX2, why did DFU protect only against glutamate toxicity? (2) While toxic concentrations of NMDA did not induce COX2, DFU had a protective effect on NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity. The implication is that these neurotoxins induce different sets of effector genes that may or may not depend on COX2 activity for neuronal cell death to proceed. Kainate-mediated neurotoxicity in cerebellar granule cells is independent of glutamate (NMDA)–mediated neurotoxicity and COX2. The sensitivity of glutamate-mediated cell death to COX2 inhibition is one marker of these separate pathways. In conclusion, measuring arachidonic acid and its metabolites in primary neuronal cultures following exposure to toxic or protective (Marini and Paul, 1992; Banaudha et al., 2000) glutamatergic agonists (±antagonists, ±DFU), and a series of add-back experiments, will better define the role of arachidonic acid metabolites in excitotoxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Krishna Banaudha, George Bratinov, and R. J. Meagher for able technical assistance. Thanks to Jilly Evans (Merck and Co.) for the DFU. We wish to recognize our chairmen, Raj K, Narayan, M.D. (Temple Neurosurgery) and Bahman Jabbari, M.D. (USUHS Neurology), for their support and encouragement. This work was funded by NINDS (R01 NS38654; K.S), the Sam & Bertha Brochstein Fund (K.S.), and the Defense and Veterans Head Injury Program (A.M.M.).

REFERENCES

- ADAMS J, COLLACO-MORAES Y, DEBELLEROCHE JS. Cyclooxygenase-2 induction in cerebral cortex: an intracellular response to synaptic excitation. J. Neurochem. 1996;66:6–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAGETTA G, CORASANITI MT, PAOLETTI AM, et al. HIV-1 gp120-induced apoptosis in the rat neocortex involves enhanced expression of cyclooxygenase type 2 (COX-2) Biochem Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998;244:819–824. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAIK EJ, KIM EJ, LEE SH, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective inhibitors aggravate kainic acid induced seizure and neuronal cell death in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 1999;843:118–129. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01797-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANAUDHA K, MARINI AM. AMPA prevents glutamate-induced neurotoxicity and apoptosis in cultured cerebellar granule cell neurons. Neurotoxicity Res. 2000;2:51–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03033327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEAMAN-HALL CM, LEAHY JC, BENMANSOUR S, et al. Glia modulate NMDA-mediated signaling in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurochem. 1998;71:1993–2005. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71051993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIDMON H-J, OERMANN E, SCHIENE K, et al. Unilateral upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 following cerebral, cortical photothrombosis in the rat: suppression by MK-801 and co-distribution with enzymes involved in the oxidative stress cascade. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2000;20:163–176. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(00)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUCCELLATI C, FOLCO GC, SALA A, et al. Inhibition of prostanoid synthesis protects against neuronal damage induced by focal ischemia in rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;257:123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAGGIANO AO, BREDER CD, KRAIG RP. Long-term elevation of cyclooxygenase-2, but not lipoxygenase, in regions synaptically distant from spreading depression. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;376:447–462. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961216)376:3<447::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANDELARIO-JALIL E, AJAMIEH HH, SAM S, et al. Nimesulide limits kainate-induced oxidative damage in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000;390:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAO C, MATSUMURA K, WATANABE Y. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in the brain by cytokines. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1997;813:307–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN J, MARSH T, ZHANG JS, et al. Expression of cyclo-oxygenase 2 in rat brain following kainate treatment. Neuroreport. 1995;6:245–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHRISTIE MJ, VAUGHAN CW, INGRAM SL. Opioids, NSAIDs and 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors act synergistically in brain via arachidonic acid metabolism. Inflamm. Res. 1999;48:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s000110050367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLACO-MORAES Y, ASPEY B, HARRISON M, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 messenger RNA induction in focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:1366–1372. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199611000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DASH PK, MACH SA, MOORE AN. Regional expression and role of cyclooxygenase-2 following experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2000;17:69–81. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEAUSEAULT D, GIROUX D, WOOD CE. Ontogeny of immunoreactive prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase isoforms in ovine fetal pituitary, hypothalamus and brainstem. Neuroendocrinology. 2000;71:287–291. doi: 10.1159/000054548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOLAN S, NOLAN AM. N-Methyl-d-aspartate–induced mechanical allodynia is blocked by nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Neuroreport. 1999;10:449–452. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199902250-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUMUIS A, SEBBEN M, HAYNES L, et al. NMDA receptors activate the arachidonic acid cascade system in striatal neurons. Nature. 1988;336:68–70. doi: 10.1038/336068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALLO V, SUIERGIU R, GIOVANNINI C, et al. Glutamate receptor subtypes in cultured cerebellar neurons: modulation of glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid release. J. Neurochem. 1987;49:1801–1809. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb02439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAHAM SH, NAKAYAMA M, ZHU R, et al. Cyclooxygenase 2 and the pathogenesis of delayed neuronal death after global ischemia. Neurology. 1996;46:A406. S. [Google Scholar]

- HEWETT SJ, ULIASZ TF, VIDWANS AS, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 contributes to N-methyl-d-asparate–mediated neuronal cell death in primary cortical cell culture. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 2000;293:417–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIRST WD, YOUNG KA, NEWTON R, et al. Expression of COX-2 by normal and reactive astrocytes in the adult rat central nervous system. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 1999;13:57–68. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HO L, PIERONI C, WINGER D, et al. Regional distribution of cyclooxygenase-2 in the hippocampal formation in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;57:295–303. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990801)57:3<295::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSUEH CT, CHIU CF, KELSEN DP, et al. Selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 enhances mitomycinC-induced apoptosis. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2000;45:389–396. doi: 10.1007/s002800051007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUFMANN WE, WORLEY PF, PEGG J, et al. COX-2, a synaptically induced enzyme, is expressed by excitatory neurons at postsynaptic sites in rat cerebral cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:2317–2321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUFMANN WE, ANDREASSON KL, ISAKSON PC, et al. Cyclooxygenases and the central nervous system. Prostaglandins. 1997;54:601–624. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(97)00128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELLEY KA, HO L, WINGER D, et al. Potentiation of excitotoxicity in transgenic mice overexpressing neuronal cyclooxygenase-2. Am. J. Pathol. 1999;155:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KINOUCHI H, HUANG H, ARAI S, et al. Induction of cyclooxygenase-2 messenger RNA after transient and permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats: comparison with c-fos messenger RNA by using in situ hybridization. J. Neurosurg. 1999;91:1005–1012. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOISTINAHO J, KOPONEN S, CHAN PH. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA after global ischemia is regulated by AMPA receptors and glucocorticoids. Stroke. 1999;30:1900–1905. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.9.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONG DL, HARA K, WEINSTEIN PR, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA and protein expression in a mouse model of cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1997;23:2181. [Google Scholar]

- KOVALCHUK Y, MILLER B, SARANTIS M, et al. Arachidonic acid depresses non-NMDA receptor currents. Brain Res. 1994;643:287–295. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZAREWICZ JW, WROBLEWSKI JT, PALMER ME, et al. Activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate–sensitive glutamate receptors stimulates arachidonic acid release in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27:765–770. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZAREWICZ JW, WROBLEWSKI JT, COSTA E. N-Methyl-d-asparate–sensitive glutamate receptors induce calcium-mediated arachidonic acid release in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurochem. 1990;55:1875–1881. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb05771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZAREWICZ JW, SALINSKA E, STAFIEJ A, et al. NMDA receptors and nitric oxide regulate prostaglandin D2 synthesis in the rabbit hippocampus in vivo. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2000;60:427–435. doi: 10.55782/ane-2000-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCARRONE M, BARI M, CORASANITI MT, et al. HIV-1 coat glycoprotein gp120 induces apoptosis in rat brain neocortex by deranging the arachidonate cascade in favor of prostanoids. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:196–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCHESELLI VL, BAZAN NG. Sustained induction of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2 by seizures in hippocampus. Inhibition by a platelet-activating factor antagonist. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;27:24794–24799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARINI AM, PAUL SM. N-Methyl-d-asparate receptor–mediated neuroprotection requires new RNA and protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:6555–6559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARINI AM, UEDA Y, JUNE CH. Intracellular survival pathways against glutamate receptor agonist excitotoxicity in cultured neurons. Intracellular calcium responses. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;890:421–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGINTY A, CHANG YW, SOROKIN A, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression inhibits trophic withdrawal apoptosis in nerve growth factor–differentiated PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:12095–12101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIETTINEN S, FUSCO FR, YRJANHEIKKI J, et al. Spreading depression and focal brain ischemia induce cyclooxygenase-2 in cortical neurons through N-methyl-d-aspartic acid-receptors and phospholipase A2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:6500–6505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGAYAMA M, NIWA K, NAGAYAMA T, et al. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor NS-398 ameliorates ischemic brain injury in wild-type mice but not in mice with deletion of the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:1213–1219. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAYAMA M, UCHIMURA K, ZHU RL, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition prevents delayed death of CA1 hippocampal neurons following global ischemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:10954–10959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NODE K, HUO YQ, RUAN XL, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science. 1999;285:1276–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOGAWA S, FANGYI Z, ROSS ME, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression in neurons contributes to ischemic brain damage. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:2746–2755. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02746.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'BANION MK. Cyclooxygenase-2: molecular biology, pharmacology, and neurobiology. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 1999;13:45–82. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v13.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PANIKASHVILI D, SIMEONIDOU C, BEN-SHABAT S, et al. An endogenous cannabinoid (2-AG) is neuro-protective after brain injury. Nature. 2001;413:527–531. doi: 10.1038/35097089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PASINETTI GM, AISEN PS. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is increased in frontal cortex of Alzheimer's disease brain. Neuroscience. 1998;87:319–324. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RESNICK DK, GRAHAM SH, DIXON CE, et al. Role of cyclooxygenase 2 in acute spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1998;15:1005–1013. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANFELIU C, HUNT A, PATEL AJ. Exposure to N-methyl-d-aspartate increases release of arachidonic acid in primary cultures of rat hippocampal neurons and not in astrocytes. Brain Res. 1990;526:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANZ O, ESTRADA A, FERRER I, et al. Differential cellular distribution and dynamnics of HSP70, cyclooxygenase-2, and c-Fos in the rat brain after transient focal ischemia or kainic acid. Neuroscience. 1997;80:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMPSON CW, RUWE WD, MYERS RD. Prostaglandins and hypothalamic neurotransmitter receptors involved in hyperthermia: a critical evaluation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1994;18:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH WL, DeWITT DL. Prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2. Adv. Immunol. 1996;62:167–215. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEVENS MK, YAKSH TL. Time course of release in vivo of PGE2, PGF2 alpha, 6-keto-PGF1 alpha, and TxB2 into the brain extracellular space after 15 min of complete global ischemia in the presence and absence of cyclooxygenase inhibition. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1988;8:790–798. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRAUSS KI, BARBE MF, MARSHALL R, et al. Prolonged cyclooxygenase-2 induction in neurons and glia following traumatic brain injury in the rat. J. Neurotrauma. 2000;17:695–711. doi: 10.1089/089771500415436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRAUSS KI, JACOBOWITZ DM. Quantitative measurement of calretinin and β-actin mRNA in rat brain micropunches without prior isolation of RNA. Molecular Brain Res. 1993;20:229–239. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90045-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOCCO G, FREIRE-MOAR J, SCHREIBER SS, et al. Maturational regulation and regional induction of cyclooxygenase-2 in rat brain: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Exp. Neurol. 1997;144:339–349. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALLANO ML, LAMBOLEZ B, AUDINAT E, et al. Neuronal activity differentially regulates NMDA receptor subunit expression in cerebellar granule cells. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:631–639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00631.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAUGHAN CW. Enhancement of opioid inhibition of GABAergic synaptic transmission by cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors in rat periaqueductal grey neurones. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;123:1479–1481. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VONKNETHEN A, BROCKHAUS F, KLEITER J, et al. NO-evoked macrophage apoptosis is attenuated by cAMP-induced gene expression. Mol. Med. 1999;5:572–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALLACE CS, LYFORD GL, WORLEY PF, et al. Differential intracellular sorting of immediate early gene mRNAs depends on signals in the mRNA sequence. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:26–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00026.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALTON M, SIRIMANNE E, WILLIAMS C, et al. Prostaglandin H synthase-2 and cytosolic phospholipase A2 in the hypoxic-ischemic brain: role in neuronal death or survival? Mol. Brain Res. 1997;50:165–170. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00181-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMAGATA K, ANDREASSON KI, KAUFMANN WE, et al. Expression of a mitogen-inducible cyclooxygenase in brain neurons: regulation by synaptic activity and glucocorticoids. Neuron. 1993;11:371–386. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90192-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]