Abstract

The yeast LTR retrotransposon Ty1 integrates preferentially into regions upstream of tRNA genes. The chromatin structure of transcriptionally active tRNA genes is known to be important for Ty1 integration, but specific chromatin factors that enhance integration at tRNA genes have not been identified. Here we report that the histone deacetylase, Hos2, and the Trithorax-group protein, Set3, both components of the Set3 complex (Set3C), enhance transposition of chromosomal Ty1 elements by promoting integration into the upstream region of tRNA genes. Deletion of HOS2 or SET3 reduced the mobility of a chromosomal Ty1his3AI element about sevenfold. Despite the fact that Ty1his3AI RNA, total Ty1 RNA, and total Ty1 cDNA levels were not reduced in hos2Δ or set3Δ mutants, transposition of endogenous Ty1 elements into the upstream regions of tRNAGly genes was substantially decreased. Furthermore, when equivalent numbers of Ty1HIS3 mobility events launched from a pGAL1:Ty1his3AI plasmid were analyzed, only one-quarter to one-half as many were found upstream of tRNAGly genes in a hos2Δ or set3Δ mutant than in a wild-type strain. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that Hos2 is physically associated with tRNA genes. Taken together, our results support the hypothesis that Hos2 and Set3 function at tRNA genes to promote Ty1 integration.

THE long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposon Ty1 transposes through an RNA intermediate. Ty1 RNA is reverse transcribed into a linear double-stranded cDNA that is integrated into the genome by the Ty1-encoded integrase protein (IN). Like the IN protein of retroviruses, Ty1 IN inserts cDNA into specific genomic regions that lack a strong consensus sequence. Over 90% of Ty1 elements in the sequenced Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome are distributed within 75–750 bp upstream of RNA polymerase III (Pol III)-transcribed genes (Hani and Feldmann 1998; Kim et al. 1998). This bias is a direct result of the Ty1 target preference, since Ty1 integrates preferentially into a window upstream of Pol III-transcribed genes, including tRNA genes, some snRNA genes, and the 5S rRNA gene (Ji et al. 1993; Devine and Boeke 1996; Bolton and Boeke 2003; Bachman et al. 2004). Plasmid targets containing actively transcribed tRNA genes are >100-fold more active as integration targets than plasmids that either lack tRNA genes or carry tRNA genes with mutations that block Pol III transcription (Devine and Boeke 1996). Moreover, tRNA genes on naked plasmids are not efficiently targeted in an in vitro integration assay (Ji et al. 1993). These observations support the idea that Ty1 IN recognizes specific features of chromatin for its biased integration. However, the mechanistic basis for Ty1 integration near tRNA genes remains poorly understood.

Analyses of the integration of two other yeast LTR retrotransposons, Ty3 and Ty5, have provided insights into the mechanisms involved in LTR-retrotransposon and retrovirus integration specificity. Ty3 integrates 1–4 bp upstream of the transcription initiation site of tRNA genes and other Pol III-transcribed genes (Chalker and Sandmeyer 1992). This exquisite specificity requires binding of the Pol III transcription factors TFIIIB and TFIIIC to the Pol III gene promoter (Kirchner et al. 1995). In vitro, position-specific integration results from tethering of the integration complex to the Brf and TATA-binding protein subunits of TFIIIB (Yieh et al. 2000, 2002). Ty5, in contrast to Ty3, displays a regional targeting preference, integrating into subtelomeric domains and the silent mating loci (Zou et al. 1995, 1996). Recognition of the silencing protein Sir4 by the six-amino-acid targeting domain of Ty5 IN is the primary determinant in Ty5 target specificity (Gai and Voytas 1998; Zhu et al. 1999, 2003; Xie et al. 2001). These findings suggest that tethering of the retroelement IN protein to chromatin-associated proteins can be an important factor in LTR-retroelement targeting in vivo (Bushman 2003; Sandmeyer 2003).

Several in vivo studies have shown that changes in chromatin structure can influence the local pattern and efficiency of Ty1 integration. Ty1 integrates upstream of tRNA genes with an 80-bp periodicity, and both the ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling complex, Isw2, and a subunit of TFIIIB, Bdp1, are required for this periodic pattern of integration (Bachman et al. 2004, 2005; Gelbart et al. 2005). At low efficiency, Ty1 elements can transpose into Pol II-transcribed genes with a strong preference for the promoter region (Eibel and Philippsen 1984; Simchen et al. 1984; Natsoulis et al. 1989; Wilke et al. 1989). A role for chromatin structure in integration into Pol II targets was suggested by the observation that diminished levels of histones H2A and H2B disrupt a bias in the orientation of Ty1 insertions into the CAN1 promoter (Rinckel and Garfinkel 1996). Moreover, the absence of Rad6, which ubiquitinates histone H2B at K123 and is required for methylation of histone H3 at K4 and K79 by Set1 and Dot1, respectively (Sun and Allis 2002), increases Ty1 integration into the CAN1 and URA3 loci and abolishes the preference for promoter regions (Liebman and Newnam 1993; Huang et al. 1999). The latter finding suggested to us that modification of histones could influence the efficiency and specificity of Ty1 integration. This study is the first to identify chromatin modifiers that are required for efficient integration of Ty1 elements at their preferred target sites, Pol III-transcribed genes.

Yeast cells contain a group of related histone deacetylases (HDACs) that include Rpd3, Hda1, Hos1, Hos2, and Hos3 (Kurdistani and Grunstein 2003). In contrast to the typically repressive role of other HDACs, Hos2 binds to and deacetylates histones in the coding region of active genes, and it is required for efficient transcriptional activation (Wang et al. 2002). Acetylation microarrays demonstrate that Hos2 preferentially deacetylates ribosomal protein genes (Robyr et al. 2002). Hos2 deacetylates specific lysines in histones H3 and H4, including H4 K12 and K16 (Robyr et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2002). In yeast cells, Hos2 is found in a single complex, Set3C, with Set3, Snt1, YIL112w, Sif2, Cpr1, and the NAD-dependent histone deacetylase, Hst1. Both Set3 and Hos2, but not Hst1, are required for the integrity of Set3C (Pijnappel et al. 2001). Moreover, Set3 and Hos2 promote the efficient activation of the GAL1 gene, whereas HST1 is dispensable for activation (Wang et al. 2002). Set3 is one of two proteins in yeast that, like Drosophila Trithorax, contain both SET and PHD domains (Pijnappel et al. 2001). Trithorax-group proteins in higher eukaryotes are chromatin-associated regulators that play a role in the maintenance of gene expression patterns (Ringrose and Paro 2004). Here we describe a role for Hos2 and Set3 in facilitating Ty1 transposition into the upstream region of tRNA genes. We also show that Hos2 binds to tRNA genes, consistent with a model in which Hos2 and Set3 function at these preferred Ty1 target sites to promote integration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. cerevisiae strains and media:

The genotypes of yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains are derivatives of the congenic strains BY4741 and BY4742 (Brachmann et al. 1998). Single ORF deletion derivatives of BY4741 were obtained from Open Biosystems. Strain JC3212 contains the chromosomal Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 element, which was introduced into strain BY4741 by galactose induction of the pGAL1:Ty1his3AI[Δ1] element, as described previously (Curcio and Garfinkel 1991). Strain JC3787 is a segregant of a cross between JC3212 and BY4742. To generate strains JC3993, JC3994, and JC3995, we performed crosses between strain JC3787 and the appropriate ORF deletion derivative of BY4741. His+ prototroph formation was assayed semiquantitatively in six or more segregants harboring the ORF deletion and Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114. Strains JC3993, JC3994, and JC3995 are representative segregants from each cross. The trp1:hisG-URA3-hisG allele (Alani et al. 1987) was introduced into strains JC3877 and JC4030 by gene disruption of strains BY4741hos2Δ and JC3993, respectively.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains used in this study

| Strain name | Genotype |

|---|---|

| BY4741 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| BY4742 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| BY4741, hos2Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hos2Δ∷kanMX |

| BY4741, set3Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 set3Δ∷kanMX |

| BY4741, hos3Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hos3Δ∷kanMX |

| BY4741, rad6Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 rad6Δ∷kanmx |

| BY4741, tec1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 tec1Δ∷kanMX |

| BY4741, spt3Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 spt3Δ∷kanMX |

| BY4741, rpd3Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 rpd3Δ∷kanMX |

| BY4741, dbr1Δ | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 dbr1Δ∷kanMX |

| JC3212 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 |

| JC3787 | MATα his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 |

| JC3877 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hos2Δ∷kanMX trp1∷hisG-URA3-hisG |

| JC3993 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hos2Δ∷kanMX Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 |

| JC3994 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 set3Δ∷kanMX Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 |

| JC3995 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hos3Δ∷kanMX Ty1his3AI-3114 |

| JC4030 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 trp1∷hisG-URA3-hisG hos2Δ∷kanMX Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 |

| JC4070 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hos2Δ∷kanMX Ty1his3AI-3114 rad52∷hisG-URA3-hisG |

| JC4072 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 Ty1his3AI-3114 rad52∷hisG-URA3-hisG |

| JC4074 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 set3Δ∷kanMX Ty1his3AI-3114 rad52∷hisG-URA3-hisG |

| JC4203 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hos2Δ∷kanMX set3Δ:URA3 Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 |

| JC4391 | MATahis3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hst1Δ∷kanMX Ty1his3AI[Δ1]-3114 |

The rad52:hisG-URA3-hisG allele (Curcio and Garfinkel 1994) was introduced into strains JC4070, JC4072, and JC4074 by one-step gene disruption of JC3993, JC3212, and JC3994, respectively. The set3ΔURA3 allele of strain JC4203 was introduced by PCR-mediated gene disruption in strain JC3993, using a PCR product synthesized with primers SET3KO-F and SET3KO-R (Table 2) and plasmid pRS406 DNA (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). The hst1ΔkanMX allele in strain JC4391 was introduced by PCR-mediated gene disruption of strain JC3212, using a PCR product synthesized with primers HST-UP/S1 and HST1-DN/A1 (Table 2) and genomic DNA from strain BY4741 hst1Δ. Gene replacements were confirmed by two independent PCR analyses. His+ prototroph formation was assayed semiquantitatively in four or more transformants. Strains JC4070, JC4072, JC4074, JC4203, and JC4391 are representative transformants from each transformation.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| SUF16-2 | 5′-GGCAACGTTGGATTTTACCAC-3′ |

| HIS3OUT-3 | 5′-CTTCGTTTATCTTGCCTGCTT-3′ |

| TYBOUT2 | 5′-GTGATGACAAAACCTCTTCCG-3′ |

| TEL1-F | 5′-CGGATTTCTGACGATATGGAC-3′ |

| TEL1-R | 5′-ACCAACGTACTGAAGGTATCC-3′ |

| LTR-PROBE | 5′-GTGGAAGCTGAAACGCAAGGATTGAT-3′ |

| RPL27A-F | 5′-GAAAAAAGCATCAATAGCCACC-3′ |

| RPL27A-R | 5′-GAGAAAAATTATCATAGGCCCACG-3′ |

| NSUF16-1F | 5′-ATAAAGTAAAAAAGATGCGCAAGCC-3′ |

| NSUF16-1R | 5′-TGCTTTTCTCGAATCATGTATCAAG-3′ |

| NSUF16-2F | 5′-GAAAATTTTCATAACGAATCTCTTCTATTC-3′ |

| NSUF16-2R | 5′-TTGCGCATCTTTTTTACTTTATATAC-3′ |

| NSUF16-3F | 5′-CTTACTACGAAAAGTGTTTCCC-3′ |

| NSUF16-3R | 5′-TGGTATTCCTGTTCCCAATAAC-3′ |

| NtRNAQ-1F | 5′-AATCTGTATTCAAAAAAAGGTCCTACCC-3′ |

| NtRNAQ-1R | 5′-AATATTACAAGAAGTCCTGGTCCTATAG-3′ |

| NtRNAQ-2F | 5′-CGTGTAACTGCTGTAGAAATTG-3′ |

| NtRNAQ-2R | 5′-ACTATCTTCAGATACAGAAGAACG-3′ |

| NtRNAQ-3F | 5′-CGAGCCCGTAATACAACATAATATC-3′ |

| NtRNAQ-3R | 5′-GGCAACCAAAACGTAATCTAAAAG-3′ |

| TDH3-F | 5′-ACCACCAACTGTTTGGCTC-3′ |

| TDH3- R | 5′-GACAGTGGTCATCAAACCTTC-3′ |

| YPT53-F | 5′-AAGGCTCAAAACTGGGTCG-3′ |

| YPT53-R | 5′-CATTTTGTTCCCCACCAAG-3′ |

| SET3KO-F | 5′-GAGAACTGAATCATGTCAGTACCTAATTCCAAAGAGCAG TCGCTGTGCGGTATTTCACACCG-3′ |

| SET3KO-R | 5′-ATGTTTATTTCAGTAGTTTTTTTCTGTAATCCGCAAAGCT TAATTAGATTGTACTGAGAGTGCAC-3′ |

| HST1-UP/s1 | 5′-TGATGACTCAGTAAGACCGCC-3′ |

| HST1-DN/A1 | 5′-TCAAGAGGAACTGATCAGTGG-3′ |

Yeast media were prepared by standard methods. Unless otherwise indicated, all media contained 2% glucose.

Plasmids:

Plasmid pGAL1:Ty1his3AI[Δ1] contains a 104-bp artificial intron inserted into the HIS3 ORF at position +404, which is within the interval that is deleted in the his3Δ1 allele present in strains BY4741 and BY4742 (Scholes et al. 2001). Plasmids PAW202 and PAW203, TRP1-CEN vectors harboring HOS2-myc and hos2(H195A, H196A)-myc alleles, respectively (Wang et al. 2002), were generously provided by Michael Grunstein (University of California at Los Angeles).

Transposition of chromosomal Ty1his3AI elements:

Cells from a single colony of each strain were grown in YEPD broth at 30° overnight, diluted 1:1000 into 3–12 cultures of YEPD broth, and grown at 20° for 3 days. Aliquots of each culture were plated onto YEPD and SC–His agar. The frequency of Ty1his3AI transposition is equal to the number of His+ prototrophs divided by the number of viable cells in the same culture volume. Strain JC4030 carrying various TRP1-CEN plasmids was grown in SC–Trp broth at 30° overnight, diluted 1:1000 into cultures of YEPD broth, and grown at 20° for 3 days. Aliquots of each culture were plated on SC–Trp agar and SC–His–Trp agar. The frequency of Ty1his3AI transposition is equal to the number of His+ Trp+ prototrophs divided by the number of Trp+ colonies in the same culture volume.

Quantification of Ty1 RNA and cDNA:

Northern blot analysis of Ty1his3AI, Ty1, and PYK1 RNA was performed as described previously (Scholes et al. 2001). For Ty1 cDNA analysis, independent colonies of each strain were each inoculated into a culture of 10 ml YEPD broth and grown at 20° for 2 days. Genomic DNA prepared from each culture was digested with PvuII, and Ty1 cDNA was quantified relative to genomic Ty1 DNA in each sample as described previously (Scholes et al. 2001).

Endogenous Ty1 integration assay:

Genomic DNA (1 μg) extracted from independent cultures of strain BY4741 and hos2Δ, set3Δ, hos3Δ, spt3Δ, and tec1Δ derivatives and grown as described for Ty1 cDNA analysis was used as template DNA in a PCR-based assay to detect insertion of Ty1 upstream of tRNAGly genes (Scholes et al. 2001). PCR reactions containing primers TYBOUT-2 and SUF16-2 (Table 2) were performed for five cycles at 94° for 30 sec, 65° for 30 sec, 72° for 1 min followed by 20 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 60° for 30 sec, and 72° for 1 min. Twenty-five cycles were shown to be within the geometric range of the reaction in control experiments with varied cycle numbers. PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and transferred onto a Hybond–N+ membrane (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK). The membrane was probed with primer LTR–PROBE (Table 2) end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase. Southern blot bands were visualized by autoradiography. As a control for equal loading of DNA, a 0.48-kb fragment of the TEL1 gene was amplified in separate PCR reactions using 200 ng genomic DNA and primers TEL1-F and TEL1-R (Table 2) and the same cycling conditions. PCR products were run on a 1% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide.

Ty1HIS3 integration assay:

Independent transformants of strain BY4741 and hos2Δ, set3Δ, hos3Δ, rpd3Δ, and rad6Δ derivatives containing plasmid pGAL1Ty1his3AI-Δ1 were grown in SC–Ura broth at 30° overnight. Cultures were diluted 1:100 in SC–Ura 2% galactose broth and grown at 20° for 3 days. Aliquots of each galactose culture were plated on SC–His + 5-FOA agar. Ten His+ Ura− colonies from independent cultures of hos2Δ, set3Δ, and wild-type strains were single colony purified and saved for Southern blot analysis. His+ Ura− colonies were counted, and 1000 His+ Ura− colonies were pooled in 10 ml SC–His broth and grown at 30° for 12 hr. Genomic DNA (0.4 μg) prepared from each pool was subject to PCR amplification using 0.5 μm HISOUT3 primer, 0.5 μm SUF16-2 primer, 0.15 μm Tel1-F primer, 0.15 μm Tel1-R primer, 1 μCi of [α-32P]dATP and 0.2 mm dNTPs. PCR reactions were performed for 5 cycles at 94° for 30 sec, 65° for 30 sec, 72° for 2 min followed by 20 cycles of 94° for 30 sec, 60° for 30 sec, and 72° for 2 min. Twenty-five cycles was shown to be within the geometric range of the reaction in control experiments with varied cycle numbers. PCR products were separated on a 2% agarose gel. The gel was dried, and products were visualized by autoradiography. The 32P activity in each lane was quantified using a Storm 860 Phosphorimager and ImageQuant software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation:

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed using strain JC3877 carrying plasmid PAW202 and strain BY4741. Cells were grown in SC–Trp broth to an OD600 of ∼1.0. Formaldehyde was added to a final concentration of 1%, and cultures were incubated for 15 min. Glycine was added to a final concentration of 125 mm and incubated for 5 min. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and 150 mm NaCl. Cells from 50 ml of culture were resuspended in 400 μl FA–lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES–KOH (pH 7.5), 140 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% Na deoxycholate) containing 1 mm PMSF, 1 μg/ml leupeptin and 1 μg/ml pepstatin together with 500 μl of glass beads, and the cultures were vortexed at 4° for 40 min. Lysates were sonicated six times with five pulses at 90% duty, 30% output using a Branson Ultrasonics (Danbury, CT) model 250 sonifier. The resulting DNA fragments ranged from 100 to 1000 bp and averaged 500 bp in length. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°. A 100-μl aliquot of lysate was diluted fivefold in FA–lysis buffer and incubated with 50 μl of a 50% suspension of Protein A Sepharose beads at 4° for 1 hr. The lysate was clarified and then incubated with 3 μg of anti-c-myc antibody (Covance) or no antibody at 4° for 12 hr. The samples were incubated with 40 μl of a 50% suspension of Protein A Sepharose beads for 2 hr at 4°. The precipitated complex was washed twice with 1.4 ml FA–lysis buffer, once with 1.4 ml FA–lysis buffer/500 mm NaCl, once with 1.4 ml immunoprecipitation wash solution [10 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 0.25 m LiCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% Na deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA], and once with 1.4 ml of 50 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mm EDTA at room temperature. Immunoprecipitated DNA was eluted by incubating beads in 50 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mm EDTA, and 1% SDS at 65° for 15 min. The supernatant was removed and a second elution was performed with 50 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mm EDTA, and 0.67% SDS. Eluates were pooled and incubated at 65° overnight, phenol:chloroform (1:1) was extracted, and ethanol was precipitated and dissolved in 25 μl water.

PCR reactions of 25 μl contained 3 μl of template DNA, 1 μl (0.5 μCi) of [α-32P]dATP, 0.5 μl of 25 μm RPL27A-F primer, 0.5 μl of 25 μm RPL27A-R primer, and 0.5 μl of each of two 25-μm solutions of primers specific for the genomic site examined. Primers NSUF16-1F and -1R were used for amplification of the coding region of SUF16; NSUF16-2F and -2R for the downstream region of SUF16; NSUF16-3F and -3R for the upstream region of SUF16; NtRNAQ-1F and -1R for the coding region of tQ(UUG)C; NtRNAQ-2F and -2R for the downstream region of tQ(UUG)C; and NtRNAQ-3F and -3R for the upstream region of tQ(UUG)C (Table 2). Following 25 cycles of PCR, products were separated on a 10% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. Results were visualized by autoradiography and quantified using a STORM 860 PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software.

RESULTS

Hos2 and Set3 as activators of Ty1 retrotransposition:

The goal of this work was to identify chromatin-associated factors that promote the integration of Ty1 elements at their preferred target sites, the regions upstream of tRNA genes. To initiate this project, we screened a small collection of yeast mutants harboring deletions in genes that encode chromatin-modifying factors for those with a reduced level of Ty1 mobility. A chromosomal Ty1 element marked with the retrotransposition indicator gene, his3AI, was introduced into each deletion strain in genetic crosses. The frequency with which Ty1his3AI gives rise to cDNA that integrates or recombines into the genome is proportional to the frequency of His+ prototroph formation in each strain, since splicing of the intron (AI) from Ty1his3AI RNA results in synthesis of Ty1 cDNA encoding a functional HIS3 gene (Curcio and Garfinkel 1991). Therefore, we measured His+ prototroph formation in each deletion mutant to identify a mutant with a reduced level of Ty1his3AI cDNA mobility. This screen led to the identification of Hos2 and Set3 as factors that promote efficient retromobility of chromosomal Ty1 elements.

To quantify the reduction in Ty1 mobility in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants, we measured the frequency of His+ prototroph formation, herein referred to as the frequency of Ty1his3AI mobility. Ty1his3AI mobility in a hos2Δ, set3Δ, or hos2Δset3Δ mutant was reduced to 11–22% of the frequency in the wild-type strain (Table 3). In contrast, Ty1his3AI mobility was modestly increased in the absence of the histone deacetylase Hos3 and only slightly reduced in the absence of the deacetylase Hst1, which, like Hos2 and Set3, is a component of Set3C.

TABLE 3.

Ty1his3AI mobility frequency in the absence of Hos2 and Set3

| Experiment | Strain | Relevant genotype | No. of cultures | Average mobility frequencya ± SE (× 10−8) | Relative mobility frequencyb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | JC3212 | Wild type | 3 | 52.0 ± 2.7 | 100 |

| JC3993 | hos2Δ | 5 | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 14 | |

| JC3994 | set3Δ | 3 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 11 | |

| JC3995 | hos3Δ | 3 | 94.3 ± 2.8 | 181 | |

| JC4203 | set3Δ hos2Δ | 5 | 6.8 ± 1.1 | 13 | |

| II | JC4072 | rad52Δ | 12 | 128.0 ± 7.2 | 100 |

| JC4070 | rad52Δ hos2Δ | 8 | 39.0 ± 5.6 | 30 | |

| JC4074 | rad52Δ set3Δ | 8 | 67.8 ± 9.0 | 53 | |

| III | JC3212 | Wild type | 4 | 23.8 ± 3.2 | 100 |

| JC3993 | hos2Δ | 4 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 22 | |

| JC4391 | hst1Δ | 4 | 18.4 ± 2.8 | 77 |

SE, standard error.

The number of His+ prototrophs divided by the total number of cells plated.

Mobility frequency relative to the wild-type or rad52Δ control strain in each experiment.

Ty1 cDNA mobility can occur by two mechanisms: the cDNA can transpose into the genome through the action of the Ty1-encoded integrase, or the cDNA can recombine with homologous Ty1 sequences. Accordingly, deletion of HOS2 or SET3 may cause a reduction in Ty1 cDNA recombination rather than transposition. Rad52 is required for homologous recombination of Ty1 cDNA with genomic Ty1 elements (Sharon et al. 1994). Therefore, we determined whether Ty1his3AI mobility is reduced when either HOS2 or SET3 is deleted from a rad52Δ strain. As previously shown, the rad52Δ mutation increases the frequency of Ty1his3AI mobility relative to the wild-type strain (Table 3). Nonetheless, the retromobility frequency in a rad52Δ hos2Δ or rad52Δ set3Δ strain was 30% or 53%, respectively, of that in a rad52Δ strain. These data support the hypothesis that Hos2 and Set3 are required for efficient integration of Ty1 cDNA.

To determine whether the catalytic activity of the deacetylase Hos2 is necessary to promote transposition, we introduced a TRP1-CEN vector harboring the catalytically inactive hos2(H195A, H196A) allele or the wild-type HOS2 allele into the hos2Δ strain JC4030. The wild-type and mutant Hos2 proteins are expressed from these plasmids at equivalent levels (Wang et al. 2002). The frequency of Ty1his3AI mobility in the strain expressing Hos2-H195A, H196A, was the same as that of the strain lacking any HOS2 allele (Table 4). In contrast, mobility was increased threefold when wild-type Hos2 was expressed. This finding suggests that the deacetylase activity of Hos2 is important for efficient transposition of chromosomal Ty1 elements.

TABLE 4.

The effect of a catalytically inactive allele of Hos2 on Ty1his3AI mobility

| Relevant genotype | Plasmid | No. of cultures | Average mobility frequency ± SE (× 10−8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hos2Δ | pCEN vector | 4 | 15.3 ± 6.0 |

| hos2Δ | pCEN-HOS2 | 4 | 47.1 ± 10.0 |

| hos2Δ | pCEN-hos2(H195A, H196A) | 4 | 16.1 ± 2.2 |

SE, standard error.

aThe number of His+ Trp+ prototrophs divided by the total number of Trp+ cells plated.

Ty1 RNA and cDNA levels in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants:

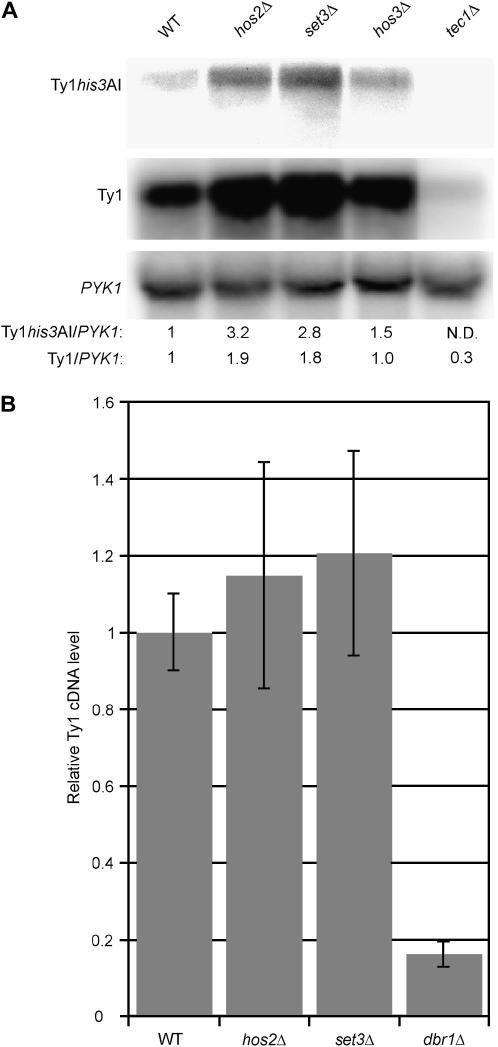

We considered the possibility that Ty1 cDNA mobility is inhibited in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants because Ty1 RNA levels are reduced. We tested this idea by quantifying Ty1his3AI RNA and total Ty1 RNA relative to a control transcript, PYK1 RNA, using Northern blot analysis (Figure 1A). The relative levels of Ty1his3AI and total Ty1 RNA were not decreased, but instead were increased approximately three- and twofold, respectively, in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants. Deletion of HOS3 had little or no effect on the level of Ty1his3AI RNA or Ty1 RNA. In contrast, deletion of TEC1, which encodes a transcription factor required for efficient Ty1 element expression, significantly reduced the levels of both Ty1his3AI RNA and total Ty1 RNA. These data demonstrate that the lower levels of Ty1his3AI mobility in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants do not result from reduced amounts of Ty1his3AI RNA or total Ty1 RNA.

Figure 1.

Ty1 RNA and cDNA levels are not reduced in hos2Δ or set3Δ mutants. (A) Northern blot analysis of RNA isolated from congenic strains whose relevant genotypes are provided. The Northern blot was probed with 32P riboprobes that hybridize to Ty1his3AI RNA (top), total Ty1 RNA (middle), and PYK1 RNA (bottom), the latter as a loading control. Autoradiograms of the blot hybridized to each probe are shown. The ratio of 32P activity in the Ty1his3AI band to 32P activity in the PYK1 band and the ratio of 32P activity in the Ty1 band to 32P activity in the PYK1 band were determined by phosphorimaging. Ty1his3AI/PYK1 and Ty1/PYK1 RNA ratios for each strain normalized to that of the wild-type strain are provided below each lane. (B) The average amount of Ty1 cDNA in genomic DNA from six independent cultures of the wild-type strain, six cultures of the hos2Δ strain, six cultures of the set3Δ strain, and two cultures of the dbr1Δ strain. Ty1 cDNA was measured relative to Ty1 genomic DNA by Southern blot analysis of PvuII-digested genomic DNA using a Ty1 riboprobe. Error bars, ± standard error.

Another possibility is that the absence of Hos2 and Set3 indirectly affects a post-transcriptional step in Ty1 retrotransposition, resulting in lower levels of Ty1 cDNA available for transposition. To test this hypothesis, we prepared genomic DNA from hos2Δ, set3Δ, and wild-type strains and from a dbr1Δ strain as a control. Total unintegrated Ty1 cDNA relative to genomic Ty1 DNA in each strain was measured using a standard Southern blot assay (Scholes et al. 2001). The average level of Ty1 cDNA in the hos2Δ or set3Δ mutant was comparable to that of the wild-type strain (Figure 1B). In contrast, the dbr1Δ mutant, which has a defect in Ty1 cDNA accumulation (Karst et al. 2000), had only 18% as much Ty1 cDNA as the wild-type strain. This finding suggests that Hos2 and Set3 stimulate Ty1 transposition at a step subsequent to the accumulation of Ty1 cDNA.

Reduced integration of Ty1 cDNA upstream of tRNAGly genes in the absence of Hos2 or Set3:

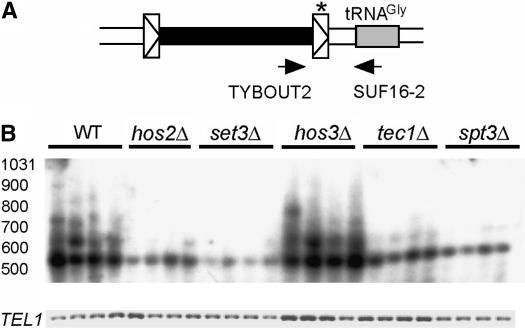

The fact that Ty1his3AI mobility is decreased even though Ty1 cDNA levels are normal suggested that Ty1 cDNA is not utilized efficiently for integration in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants. To determine if integration was reduced in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants, we used a PCR assay to detect nascent Ty1 integration events in the upstream regions of tRNAGly genes. There are 16 different tRNAGly genes in the genome, and at least 2 are known hotspots for Ty1 transposition (Ji et al. 1993; Bachman et al. 2004). Ty1:tRNAGly gene junction fragments were amplified from four genomic DNA samples of each strain using one primer that recognizes TYB1 sequences and one primer that recognizes 16 tRNAGly genes (Figure 2A). Ty1 transposition events upstream and in the same orientation as tRNAGly genes can be detected using this method. Ty1:tRNAGly gene junctions do not preexist in the BY4741 genome (Saccharomyces Genome Database; http://www.yeastgenome.org), but are detected when transposition is induced by growth at 20°, a permissive temperature for transposition. To ensure that the PCR reactions were within the geometric range, we used a low number of PCR cycles and detected the Ty1:tRNAGly gene junctions by Southern blotting (Figure 2B). The intensity and number of bands provide a relative measure of the level of integration in each sample. As has been demonstrated previously (Scholes et al. 2001; Bachman et al. 2004), the wild-type strain yielded a ladder of PCR products between 0.55 and 1.0 kb, representing Ty1 insertions ∼85–550 bp upstream of one or more tRNAGly genes. Genomic DNA samples from the spt3Δ and tec1Δ strains, both of which lack a transcription factor required for Ty1 RNA expression, showed a substantially reduced level of Ty1 integration, consistent with the low levels of Ty1 transposition in these strains. Notably, the levels of Ty1 integration in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants were reduced to levels comparable to those in the tec1Δ or spt3Δ strain. Similar results were obtained when PCR was performed with a primer that detects Ty1 insertions in the opposite orientation (data not shown), indicating that there is no orientation bias in the reduced integration of Ty1 at tRNAGly genes in hos2Δ and set3Δ strains. In contrast to hos2Δ and set3Δ strains, hos3Δ strains did not have decreased levels of Ty1 integration upstream of tRNAGly genes (Figure 2B). Overall, these findings indicate that Hos2 and Set3 are required for efficient integration into normally preferred target sites. Therefore, our data support the conclusion that Hos2 and Set3 affect a step after the accumulation of Ty1 cDNA but before or at integration of the Ty1 cDNA.

Figure 2.

Integration of Ty1 into the upstream regions of tRNAGly genes is reduced in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants. (A) Schematic of a Ty1 element (solid rectangle surrounded by boxed triangles) that has transposed upstream from a tRNAGly gene (shaded rectangle), illustrating the PCR primers used to detect de novo Ty1 integration events. The asterisk indicates the location of the LTR probe used in Southern analysis. (B) Southern blot of PCR products of unselected Ty1 integration events present in the genomic DNA of the strains indicated (top). The PCR product of the single-copy TEL1 gene was obtained using the same genomic DNA as template in a parallel reaction and was detected by ethidium bromide staining of an agarose gel (bottom).

Reduced targeting of Ty1HIS3 elements to tRNAGly genes in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants:

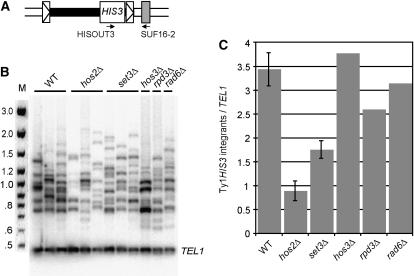

The preferred target sites for Ty1 integration have been determined by locating marked Ty1 insertions launched from plasmid-borne GAL1:Ty1 (pGTy1) elements. However, a genomewide screen did not identify either Hos2 or Set3 as necessary for the mobility of pGTy1 elements (Griffith et al. 2003). Therefore, it was important for us to determine whether pGTy1 elements, like their chromosomal counterparts, integrate at tRNA genes less efficiently in the absence of Hos2 and Set3. Plasmid pGTy1his3AI was introduced into congenic hos2Δ, set3Δ, and control strains, and mobility of the Ty1his3AI element was induced by growth on medium containing galactose. Aliquots of each induction culture were spread on selective medium to obtain His+ Ura− colonies that had sustained a Ty1HIS3 insertion into the genome but had lost the URA3-based pGTy1his3AI plasmid. The frequencies of His+ Ura− colonies arising in the hos2Δ or set3Δ mutant and the wild-type strain were equivalent (data not shown), which confirms the previous observation that neither Hos2 nor Set3 is required for mobility when Ty1 is expressed from a pGTy1 plasmid (Griffith et al. 2003).

Next, we constructed pools of 1000 His+ Ura− colonies harboring equivalent numbers of Ty1HIS3 insertions. The average number of Ty1HIS3 insertions per His+ Ura− colony was determined by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from 10 wild-type, 10 hos2Δ, and 10 set3Δ colonies. A single Ty1HIS3 insertion was detected in each of the 30 His+ Ura− isolates analyzed (data not shown). Moreover, the sizes of the Ty1HIS3 bands in genomic DNA from all three strains were variable, indicating that many independent Ty1HIS3 mobility events were represented. Therefore, 1000 His+ Ura− colonies from independent induction cultures of each strain were scraped from plates, and genomic DNA was prepared from each pool. Genomic DNA from three independent wild-type colony pools, three hos2Δ colony pools, three set3Δ colony pools, and one pool each of colonies from hos3Δ, rpd3Δ, and rad6Δ mutants as controls were subjected to PCR using one primer that hybridized to HIS3 sequences in the Ty1HIS3 insertion and one primer that hybridized to tRNAGly genes (Figure 3A). Primers that amplify a fragment of the TEL1 gene were included in each reaction as an internal control. PCR was performed using a low cycle number to ensure that the reactions were in the geometric range.

Figure 3.

Targeting of Ty1 to the upstream regions of tRNAGly genes is reduced in the absence of Hos2 or Set3. (A) Schematic of a Ty1 element (solid rectangle surrounded by boxed triangles) marked with the HIS3 gene (labeled rectangle) that has transposed upstream from a tRNAGly gene (shaded rectangle), illustrating the PCR primers used to detect de novo Ty1HIS3 integration events. (B) PCR analysis of genomic DNA from pools of 1000 His+ colonies that each sustained a Ty1HIS3 insertion event. Genomic DNA from one pool of 1000 is analyzed per lane. PCR products were labeled by inclusion of [α-32P]dATP in each reaction. Bands >0.7 kb are Ty1HIS3:tRNAGly junction products and the 0.48-kb band is an internal control product from the TEL1 gene. (C) The ratio of 32P activity in Ty1HIS3:tRNAGly junction products ranging from 0.7 to 2.2 kb relative to the 32P activity in the 0.48-kb TEL1 product. The average ratio is presented for strains for which three pools of 1000 His+ colonies were analyzed. Error bars, ± standard error.

PCR reactions using genomic DNA from each pool yielded a 0.48-kb TEL1 band and a series of bands ranging in size from 0.75–2.2 kb, indicative of Ty1HIS3 integration events between ∼50 and ∼1500 bp upstream of tRNAGly genes (Figure 3B). This range of integration events was broader than the range that is typically seen, which may reflect differences in our experimental method relative to the standard integration assay. The 32P activity in individual bands from 0.7- to 2.2-kb products was summed and divided by the 32P activity in the TEL1 band to obtain the relative level of Ty1 integration upstream of tRNAGly genes in each independent sample. The average level of Ty1HIS3 integration upstream of tRNAGly genes in the hos2Δ mutant pools was approximately one-quarter of that in the wild-type pools (Figure 3C). Similarly, set3Δ mutants had about one-half the level of integration into tRNAGly genes as the wild-type strains did. In contrast, absence of the deacetylase Hos3 or Rpd3 or the histone-ubiquitinating enzyme Rad6 did not alter the level of Ty1HIS3 integration upstream of tRNAGly genes. Thus, these findings suggest that Hos2 and Set3 promote Ty1 transposition into the regions upstream of tRNA genes. The observation that integration but not mobility of cDNA from a pGTy1his3AI element is reduced in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants supports the conclusion that Hos2 and Set3 enhance integration rather than an earlier step in transposition. Ty1HIS3 cDNA that is not integrated upstream of tRNA genes in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants may integrate elsewhere or may recombine with preexisting Ty1 elements in the genome.

Binding of Hos2 to tRNA genes:

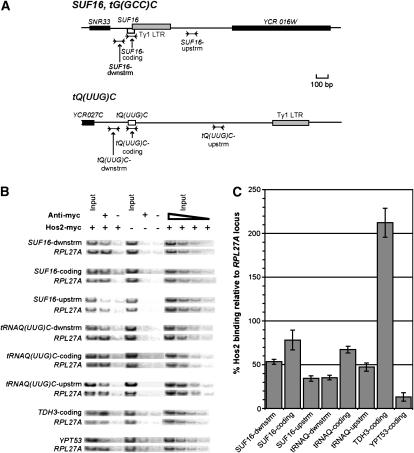

Given the known role of Hos2 in deacetylating histones, we hypothesized that Hos2 and Set3 directly promote Ty1 integration by associating with or modifying chromatin at tRNA genes. Therefore, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments to determine if Hos2 binds to the SUF16/tG(GCC)C locus, a tRNAGly gene that is a known hotspot for Ty1 integration, and to the tQ(UUG)C locus, a tRNAGln gene that is a relatively poor Ty1 integration target (Ji et al. 1993). Binding to regions within, upstream, and downstream of each tRNA gene was examined (Figure 4A). For comparison, we also examined the binding of Hos2 to a poorly expressed gene, YPT53, and to a highly expressed gene, TDH3 (Holstege et al. 1998), since the level of Hos2 binding to a gene is correlated with the level of mRNA produced from that gene (Wang et al. 2002). A hos2Δ strain was transformed with a CEN plasmid that encodes Hos2 fused at the C terminus to 13 tandem copies of the myc epitope (Wang et al. 2002). Chromatin was immunoprecipitated using an antibody to the myc epitope. PCR was used to determine the level of Hos2 binding at or near the two tRNA genes relative to binding at RPL27A, a known Hos2-binding target used as an internal control (Robyr et al. 2002) (Figure 4B). Hos2 bound both tRNA genes tested. Although Hos2 binding to SUF16 and tQ(UUG)C was 78% and 67% of the binding to RPL27A, respectively, it was substantially increased above the background level, represented by 13% binding at the poorly expressed gene, YPT53. Binding of Hos2 to regions upstream or downstream of either tRNA gene was not as strong as to the tRNA gene itself. However, we could not examine Hos2 binding immediately upstream of either tRNA gene because there is a Ty1 LTR immediately upstream of SUF16 and degenerate Ty1 LTR sequences upstream of tQ(UUG)C. The presence of these LTR sequences prohibited the design of unique PCR primers that anneal directly upstream of these tRNA genes. Nonetheless, our results demonstrate that Hos2 is physically associated with tRNA genes. This finding supports the hypothesis that Hos2 functions at Ty1 target sites to promote integration. The fact that Hos2 binds relatively hot and cold tRNA gene target sites equivalently suggests that Hos2 is necessary but not sufficient to promote integration of Ty1 at tRNA genes.

Figure 4.

ChIP analysis indicates that Hos2 is physically associated with tRNA genes. (A) Schematic of the regions around two tRNA genes analyzed, SUF16 and tQ(UUG)C. The locations of three PCR products from each tRNA gene region are indicated, as well as surrounding genomic features. (B) PCR reactions performed on DNA extracted from immunoprecipitated chromatin from strains expressing Hos2–myc (+) or Hos2 lacking a myc tag (−), using anti-myc antibody (+), or using no antibody (−). The first and fourth lanes (Input) contain PCR products from DNA extracted without immunoprecipitation at a 1:2700 dilution. The triangle represents the dilution series of control input DNA (1:900, 1:2700, 1:8100, 1:24,300). Each PCR reaction detects one product specific to a tRNA gene region and one product from the RPL27A coding region. As positive and negative controls, respectively, PCR products from the coding region of TDH3 and YPT53 were measured relative to the RPL27A product. (C) The ratio of PCR product at each genomic site examined relative to the internal RPL27A PCR product for the immunoprecipitated DNA divided by the same ratio in the input DNA. The average of three independent ChIP experiments, one of which is shown in B, is given. Error bars, ± standard error.

DISCUSSION

We used a chromosomal Ty1his3AI element as a sensitive indicator of Ty1 mobility to identify potential chromatin modifiers that are required for Ty1 integration. In a small screen of known chromatin modifiers, we identified Hos2 and Set3 as necessary for efficient mobility of a chromosomal Ty1 (Table 3). Further analyses of hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants suggested that the transposition defect in these mutants occurs during integration. This conclusion is based on the following observations. First, Ty1 and Ty1his3AI RNA levels are actually increased in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants, indicating that a decrease in expression of Ty1 elements is not the cause of lower transposition levels (Figure 1A). Second, Ty1 cDNA levels in hos2Δ and set3Δ mutants were similar to those in the wild-type strain, indicating that these mutations do not affect the accumulation of Ty1 cDNA (Figure 1B). Third, integration of chromosomal Ty1 elements into the upstream region of tRNAGly genes was significantly reduced in hos2Δ and set3Δ strains and was similar to the level of integration in an spt3Δ mutant (Figure 2). Moreover, plasmid-borne Ty1HIS3 elements transpose upstream of tRNAGly genes only one-fourth to one-half as often in a hos2Δ or set3Δ mutant, respectively, as they do in a wild-type strain (Figure 3). Finally, chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis demonstrated that Hos2 is physically associated with tRNA genes, consistent with the hypothesis that Hos2 functions at the target site to promote integration (Figure 4).

While the model that Hos2 and Set3 act at Ty1 target sites to enhance integration is a parsimonious one, we cannot rule out the possibility that Hos2 and Set3 affect transposition at a step just prior to integration. Hos2 could directly or indirectly enhance steps between Ty1 cDNA accumulation and integration. For example, we were not able to determine whether deleting HOS2 or SET3 results in lower levels of Ty1 IN, since IN is difficult to detect in wild-type strains (Curcio and Garfinkel 1992). However, the fact that Hos2 binds at tRNA genes and is also required for efficient integration at these sites suggests that the presence or function of Hos2 at tRNA genes is necessary for optimal levels of Ty1 transposition.

The physical association of Hos2 with tRNA genes is intriguing, given that all three HOS deacetylases are active at genes that encode components of the protein synthesis machinery. Acetylation microarrays have revealed that Hos1 and Hos3 are preferentially associated with ribosomal DNA and that Hos2 is associated with ribosomal protein genes. Therefore, it was proposed that HOS deacetylases play a role in coordinating expression of protein synthesis components (Robyr et al. 2002). The association of Hos2 with tRNA genes could reflect another aspect of this coordinated regulation.

Interestingly, Hos2 and Set3 are necessary for efficient mobility of chromosomal Ty1 elements but not for the mobility of Ty1 elements expressed from the GAL1 promoter. Several findings suggest that the host regulates pGTy1 elements differently from endogenous Ty1 elements. For example, pTy1 elements evade post-transcriptional cosuppression and transpose at ∼100-fold greater efficiency per transcript than endogenous Ty1 elements (Curcio and Garfinkel 1992; Garfinkel et al. 2003). The fact that mobility of cDNA from pGTy1 elements is not limited by the absence of Hos2 and Set3, but integration at tRNA genes is reduced, suggests that cDNA from pGTy1 elements can enter the genome by mechanisms other than integration. This alternative mechanism is probably recombination with endogenous Ty1 elements, since pGTy1 cDNA can recombine efficiently into the genome when integration is blocked by cis- or trans-acting mutations in the pGTy1 element (Sharon et al. 1994). Moreover, cDNA recombination is likely to be significantly more common for pGTy1 elements than for chromosomal Ty1 elements, since the mobility of pGTy1 elements is reduced in a rad52Δ mutant, whereas the mobility of endogenous Ty1 elements is actually increased in a rad52Δ mutant (Curcio and Garfinkel 1994; Griffith et al. 2003). Increased Ty1 cDNA recombination in the case of pGTy1 elements may be the reason that the mobility of only chromosomal Ty1 elements and not pGTy1 elements is reduced in the absence of Hos2 and Set3.

Two observations suggest that Hos2 affects the efficiency of Ty1 integration rather than target specificity. First, Hos2 is required for integration of chromosomal Ty1 elements at tRNA genes and for the overall mobility of Ty1his3AI elements; therefore, reduced integration at tRNA genes may account for the reduced levels of transposition. Second, we found that Hos2 was bound not only at SUF16, a tRNA gene that is a known hotspot for Ty1 integration, but also at the tQ(UUG)C gene (Figure 4), which lacks features in the adjoining DNA that are characteristic of Ty1 hotspots (Bachman et al. 2004) and was not targeted by Ty1 when compared to other tRNA genes on chromosome III (Ji et al. 1993). Moreover, Hos2 binds the ORFs of actively transcribed genes (Wang et al. 2002), and ORFs are generally poor targets of Ty1 integration (Natsoulis et al. 1989; Wilke et al. 1989; Ji et al. 1993). Therefore, it appears that Hos2 is necessary for efficient integration at tRNA genes but is not sufficient to define a tRNA gene or other region as a Ty1 hotspot.

It remains to be determined whether the presence or function of Hos2 enhances Ty1 integration upstream of tRNA genes. By analogy with Ty3 and Ty5, the Ty1 integration complex might be brought to the vicinity of tRNA genes because of an association with Hos2. As Hos2 is required for the integrity of Set3C (Pijnappel et al. 2001), Ty1 integrase might also be tethered to another component of Set3C. However, a simple tethering model cannot in itself explain why Ty1 elements fail to target all Hos2-binding sites. A second possible mechanism is that Ty1 integrase is brought to tRNA genes by tethering to another unidentified protein and that, once the integrase complex is in the vicinity, the deacetylation of histones by Hos2 or another histone modification made by Set3C promotes Ty1 integration. In support of this model, we found that the level of Ty1 transposition in a strain bearing a catalytically inactive Hos2 allele was similar to that in a hos2Δ strain (Table 4). One caveat of this interpretation, however, is that the catalytically inactive Hos2 protein does not bind to a known target DNA as efficiently as the wild-type Hos2 does (Wang et al. 2002). Therefore, the catalytically inactive Hos2 might interfere with recruitment of the Ty1 integration complex to the target site by failing to bind the target site or by failing to carry out histone modifications that enhance Ty1 integration.

Hos2 is the closest yeast homolog to mammalian HDAC3, and there are many similarities between Set3C and the partially characterized mammalian HDAC3 complexes (Pijnappel et al. 2001). In view of this, the results presented here may be relevant to the host mechanisms used to control the target-site selection of retroviruses in mammals, including humans. Intriguingly, the HIV-1 virus is preferentially targeted to the transcription units of actively transcribed genes (Schroder et al. 2002; Wu et al. 2003). This pattern of HIV-1 integration in human cells parallels the pattern of Hos2-mediated histone deacetylation of Pol II-transcribed genes in yeast. Therefore, our findings raise the possibility that patterns of histone deacetylation in humans could play a role in the target-site selection of the HIV-1 virus.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Grunstein for the kind gift of reagents and R. Morse and P. Maxwell for comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to the Wadsworth Center Molecular Genetics Core for oligonucleotide synthesis. This work was supported by a grant (GM52072) from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alani, E., L. Cao and N. Kleckner, 1987. A method for gene disruption that allows repeated use of URA3 selection in the construction of multiply disrupted yeast strains. Genetics 116: 541–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, N., Y. Eby and J. D. Boeke, 2004. Local definition of Ty1 target preference by long terminal repeats and clustered tRNA genes. Genome Res. 14: 1232–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, N., M. E. Gelbart, T. Tsukiyama and J. D. Boeke, 2005. TFIIIB subunit Bdp1p is required for periodic integration of the Ty1 retrotransposon and targeting of Isw2p to S. cerevisiae tDNAs. Genes Dev. 19: 955–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, E. C., and J. D. Boeke, 2003. Transcriptional interactions between yeast tRNA genes, flanking genes and Ty elements: a genomic point of view. Genome Res. 13: 254–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachmann, C. B., A. Davies, G. J. Cost, E. Caputo, J. Li et al., 1998. Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14: 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman, F. D., 2003. Targeting survival: integration site selection by retroviruses and LTR-retrotransposons. Cell 115: 135–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalker, D. L., and S. B. Sandmeyer, 1992. Ty3 integrates within the region of RNA polymerase III transcription initiation. Genes Dev. 6: 117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio, M. J., and D. J. Garfinkel, 1991. Single-step selection for Ty1 element retrotransposition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88: 936–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio, M. J., and D. J. Garfinkel, 1992. Posttranslational control of Ty1 retrotransposition occurs at the level of protein processing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12: 2813–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio, M. J., and D. J. Garfinkel, 1994. Heterogeneous functional Ty1 elements are abundant in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Genetics 136: 1245–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine, S. E., and J. D. Boeke, 1996. Integration of the yeast retrotransposon Ty1 is targeted to regions upstream of genes transcribed by RNA polymerase III. Genes Dev. 10: 620–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibel, H., and P. Philippsen, 1984. Preferential integration of yeast transposable element Ty into a promoter region. Nature 307: 386–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gai, X., and D. F. Voytas, 1998. A single amino acid change in the yeast retrotransposon Ty5 abolishes targeting to silent chromatin. Mol. Cell 1: 1051–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel, D. J., K. Nyswaner, J. Wang and J. Y. Cho, 2003. Post-transcriptional cosuppression of Ty1 retrotransposition. Genetics 165: 83–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelbart, M. E., N. Bachman, J. Delrow, J. D. Boeke and T. Tsukiyama, 2005. Genome-wide identification of Isw2 chromatin-remodeling targets by localization of a catalytically inactive mutant. Genes Dev. 19: 942–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith, J. L., L. E. Coleman, A. S. Raymond, S. G. Goodson, W. S. Pittard et al., 2003. Functional genomics reveals relationships between the retrovirus-like Ty1 element and its host Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 164: 867–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hani, J., and H. Feldmann, 1998. tRNA genes and retroelements in the yeast genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 26: 689–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege, F. C., E. G. Jennings, J. J. Wyrick, T. I. Lee, C. J. Hengartner et al., 1998. Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell 95: 717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H., J. Y. Hong, C. L. Burck and S. W. Liebman, 1999. Host genes that affect the target-site distribution of the yeast retrotransposon Ty1. Genetics 151: 1393–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H., D. P. Moore, M. A. Blomberg, L. T. Braiterman, D. F. Voytas et al., 1993. Hotspots for unselected Ty1 transposition events on yeast chromosome III are near tRNA genes and LTR sequences. Cell 73: 1007–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karst, S. M., M. L. Rutz and T. M. Menees, 2000. The yeast retrotransposons Ty1 and Ty3 require the RNA Lariat debranching enzyme, Dbr1p, for efficient accumulation of reverse transcripts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268: 112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. M., S. Vanguri, J. D. Boeke, A. Gabriel and D. F. Voytas, 1998. Transposable elements and genome organization: a comprehensive survey of retrotransposons revealed by the complete Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome sequence. Genome Res. 8: 464–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchner, J., C. M. Connolly and S. B. Sandmeyer, 1995. Requirement of RNA polymerase III transcription factors for in vitro position-specific integration of a retroviruslike element. Science 267: 1488–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdistani, S. K., and M. Grunstein, 2003. Histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4: 276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebman, S. W., and G. Newnam, 1993. A ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, RAD6, affects the distribution of Ty1 retrotransposon integration positions. Genetics 133: 499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsoulis, G., W. Thomas, M. C. Roghmann, F. Winston and J. D. Boeke, 1989. Ty1 transposition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is nonrandom. Genetics 123: 269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijnappel, W. W., D. Schaft, A. Roguev, A. Shevchenko, H. Tekotte et al., 2001. The S. cerevisiae SET3 complex includes two histone deacetylases, Hos2 and Hst1, and is a meiotic-specific repressor of the sporulation gene program. Genes Dev. 15: 2991–3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinckel, L. A., and D. J. Garfinkel, 1996. Influences of histone stoichiometry on the target site preference of retrotransposons Ty1 and Ty2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 142: 761–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringrose, L., and R. Paro, 2004. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38: 413–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robyr, D., Y. Suka, I. Xenarios, S. K. Kurdistani, A. Wang et al., 2002. Microarray deacetylation maps determine genome-wide functions for yeast histone deacetylases. Cell 109: 437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmeyer, S., 2003. Integration by design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 5586–5588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholes, D. T., M. Banerjee, B. Bowen and M. J. Curcio, 2001. Multiple regulators of Ty1 transposition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have conserved roles in genome maintenance. Genetics 159: 1449–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder, A. R., P. Shinn, H. Chen, C. Berry, J. R. Ecker et al., 2002. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell 110: 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon, G., T. J. Burkett and D. J. Garfinkel, 1994. Efficient homologous recombination of Ty1 element cDNA when integration is blocked. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 6540–6551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter, 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simchen, G., F. Winston, C. A. Styles and G. R. Fink, 1984. Ty-mediated gene expression of the LYS2 and HIS4 genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by the same SPT genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81: 2431–2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z. W., and C. D. Allis, 2002. Ubiquitination of histone H2B regulates H3 methylation and gene silencing in yeast. Nature 418: 104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A., S. K. Kurdistani and M. Grunstein, 2002. Requirement of Hos2 histone deacetylase for gene activity in yeast. Science 298: 1412–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, C. M., S. H. Heidler, N. Brown and S. W. Liebman, 1989. Analysis of yeast retrotransposon Ty insertions at the CAN1 locus. Genetics 123: 655–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X., Y. Li, B. Crise and S. M. Burgess, 2003. Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science 300: 1749–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W., X. Gai, Y. Zhu, D. C. Zappulla, R. Sternglanz et al., 2001. Targeting of the yeast Ty5 retrotransposon to silent chromatin is mediated by interactions between integrase and Sir4p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21: 6606–6614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yieh, L., G. Kassavetis, E. P. Geiduschek and S. B. Sandmeyer, 2000. The Brf and TATA-binding protein subunits of the RNA polymerase III transcription factor IIIB mediate position-specific integration of the gypsy-like element, Ty3. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 29800–29807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yieh, L., H. Hatzis, G. Kassavetis and S. B. Sandmeyer, 2002. Mutational analysis of the transcription factor IIIB-DNA target of Ty3 retroelement integration. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 25920–25928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y., S. Zou, D. A. Wright and D. F. Voytas, 1999. Tagging chromatin with retrotransposons: target specificity of the Saccharomyces Ty5 retrotransposon changes with the chromosomal localization of Sir3p and Sir4p. Genes Dev. 13: 2738–2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y., J. Dai, P. G. Fuerst and D. F. Voytas, 2003. Controlling integration specificity of a yeast retrotransposon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 5891–5895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, S., D. A. Wright and D. F. Voytas, 1995. The Saccharomyces Ty5 retrotransposon family is associated with origins of DNA replication at the telomeres and the silent mating locus HMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 920–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, S., N. Ke, J. M. Kim and D. F. Voytas, 1996. The Saccharomyces retrotransposon Ty5 integrates preferentially into regions of silent chromatin at the telomeres and mating loci. Genes Dev. 10: 634–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]