Abstract

Microsatellites are tandemly repeated short DNA sequences that are favored as molecular-genetic markers due to their high polymorphism index. Plant genomes characterized to date exhibit taxon-specific differences in frequency, genomic location, and motif structure of microsatellites, indicating that extant microsatellites originated recently and turn over quickly. With the goal of using microsatellite markers to integrate the physical and genetic maps of Medicago truncatula, we surveyed the frequency and distribution of perfect microsatellites in 77 Mbp of gene-rich BAC sequences, 27 Mbp of nonredundant transcript sequences, 20 Mbp of random whole genome shotgun sequences, and 49 Mbp of BAC-end sequences. Microsatellites are predominantly located in gene-rich regions of the genome, with a density of one long (i.e., ≥20 nt) microsatellite every 12 kbp, while the frequency of individual motifs varied according to the genome fraction under analysis. A total of 1,236 microsatellites were analyzed for polymorphism between parents of our reference intraspecific mapping population, revealing that motifs (AT)n, (AG)n, (AC)n, and (AAT)n exhibit the highest allelic diversity. A total of 378 genetic markers could be integrated with sequenced BAC clones, anchoring 274 physical contigs that represent 174 Mbp of the genome and composing an estimated 70% of the euchromatic gene space.

LEGUMES are the second most important crop family in terms of cultivated acreage, contribution to human and animal diets, and economic value. Their capacity for symbiotic nitrogen fixation underlies the value of legumes as a source of dietary protein, while the diversity of their metabolic output provides a wide range of pharmacologically valuable secondary natural products, including isoflavonoids and triterpene saponins. Although Arabidopsis and rice serve as models for dicot and monocot species, respectively, they cannot serve as models for identifying the genetic programs responsible for legume-specific characteristics. Two legume species, namely Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus, serve as models for legume biology.

The utility of M. truncatula as a genetic system (e.g., Penmetsa and Cook 2000), combined with its relatively small (466 Mb; Bennett and Leitch 1995) and efficiently organized genome (Kulikova et al. 2001, 2004), have motivated an international effort to develop and apply the tools of genomics in M. truncatula to key questions in legume biology. One aspect of this effort has been the development of enabling methodologies, such as efficient transformation methods (Trinh et al. 1998; Kamaté et al. 2000; Zhou et al. 2004), high-throughput systems for forward and reverse genetics, including insertional mutagenesis (d'Erfurth et al. 2003), RNAi (Limpens et al. 2003, 2004), and TILLING (VandenBosch and Stacey 2003), and an effective network among research groups (http://www.medicago.org). In parallel to these activities, national and international programs are collaborating to characterize the genome of M. truncatula at the transcript (Fedorova et al. 2002; Journet et al. 2002; Lamblin et al. 2003), protein (Gallardo et al. 2003; Watson et al. 2003; Imin et al. 2004), and whole genome sequence levels (Young et al. 2005).

Cytogenetic and genetic data predict that the genome of M. truncatula is organized into separate gene-rich euchromatic arms and gene-poor heterochromatic pericentromeric regions (Kulikova et al. 2001, 2004; Choi et al. 2004a). These results underlie a strategy for sequencing the M. truncatula genome wherein the euchromatic chromosome arms are first delimited within a physical map and then subjected to a BAC-by-BAC sequencing approach. As of March 2004, 44,292 BACs (∼11× coverage) had been fingerprinted by HindIII digestion and agarose gel electrophoresis. An initial stringent build of the map yielded 1370 contigs with an average length of 340 kbp, covering an estimated 466 Mbp or 93% of the genome. In parallel to the development of a physical map, >800 EST-containing BAC clones were sequenced to provide seed points from which to continue the whole genome sequencing effort. Sites of potential sequence polymorphism within the initial BAC sequence data are being used to facilitate merger of the genetic and physical maps, while the resulting chromosome assignments are being used to guide the distribution of BACs to sequencing centers.

A major focus of the genetic mapping effort is short tandem repeats, also known as simple sequence repeats (SSRs) or microsatellites. These repetitive sequences consist of direct tandem repeats of short (1–10 bp) nucleotide motifs. Unequal recombination between SSRs and slip-mispairing during DNA replication (Sia et al. 1997) result in polymorphism rates that tend to be much greater than those observed for nonrepetitive DNA sequences. The high rate of mutation combined with low selection coefficients on variant alleles result in extreme allelic diversity at microsatellite loci (Ross et al. 2003).

Identification of SSRs in DNA sequence databases can be automated by use of public software programs, such as SSRIT (Temnykh et al. 2001). Moreover, because SSR alleles are typically codominant and their polymorphisms can be scored either in a simple agarose gel format or in high-throughput capillary arrays, they are frequently the molecular marker of choice for construction of genetic maps. Estimates suggest that 1–5% of plant ESTs contain SSRs longer than 18 nucleotides (Kantety et al. 2002). Thus, development of EST–SSR markers has become commonplace in a wide variety of plant species (Cordeiro et al. 2001; Kantety et al. 2002; Sharopova et al. 2002; Decroocq et al. 2003; Thiel et al. 2003), including Medicago spp. (Julier et al. 2003; Eujayl et al. 2004; Gutierrez et al. 2005; Sledge et al. 2005). SSRs are even more abundant in the noncoding regions of genomic sequences, providing a rich source of genetic markers to map sequenced genome regions (Cardle et al. 2000). In rice, for example, genomic-SSR markers identified from BAC sequences provided immediate links between genetic, physical, and sequence-based maps (Temnykh et al. 2001).

In this article we report the characteristics of perfect microsatellites within the genome of M. truncatula. Genetic markers developed from SSRs in BAC sequences were incorporated into the M. truncatula genetic map, simultaneously anchoring a predicted majority of the euchromatic portion of the physical map to chromosomal loci. In total, we analyzed 77 Mbp of genomic sequence (16.5% of the genome) obtained from gene-rich BAC clones, 27 Mbp of nonredundant transcript sequence, 20 Mbp of low pass random whole genome shotgun data, and 49 Mbp of BAC-end sequences for the presence of perfect SSRs. The resulting data set allowed comparison of SSR frequency, length, motif structure, and distribution between genic and nongenic fractions of the genome. We also compared the distribution of SSRs in the M. truncatula genome to that of other legumes (soybean and L. japonicus) and model plants (Arabidopsis and rice).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Analysis of SSR content in DNA sequence:

The origin of sequence data for M. truncatula, Glycine max, L. japonicus, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Oryza sativa is given in Table 1. SSRs were identified by automated analysis using the software SSRIT (Temnykh et al. 2001), considering only perfect repeats of >12 nucleotides in length. Although SSRs are classically defined as repeats of 1- to 6-bp motifs (Tautz 1989), the present analysis also considered repeats with motif lengths of 7 and 8 bp. SSRs meeting these criteria were named according to their location within a sequence contig, and this information, along with motif structure and microsatellite size, was stored in a MySQL relational database. Mononucleotide repeats in whole genome shotgun and BAC-end sequence data were not considered in this analysis due to the difficulty of distinguishing bona fide microsatellites from sequencing or assembly error. Similarly, (A/T)n repeats in EST sequence data were not considered due to possible confusion with polyadenylation tracks. Gene-coding regions were predicted in M. truncatula using the eudicot version of FGENESH (http://www.softberry.com). BAC-end sequences were divided into gene-containing and gene-poor data sets based on BLASTN against the TIGR M. truncatula GeneIndex Release 6.0 (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/mtgi) with a cutoff value E−10. The t-test statistic was used to compare the frequencies of SSRs in genomic and EST data between species. The chi-square test was used to evaluate differences in SSR frequencies between the different genome fractions of M. truncatula.

TABLE 1.

Source of genomic and transcript sequences

| Species | Database | Sequence type |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA sequences | ||

| Medicago truncatula | NCBI HTGS | Phase 1 and 2 BAC clones |

| NCBI NR | Phase 3 BAC clones | |

| NCBI GSS | Random genome shotgun | |

| NCBI HTGS | BAC end | |

| Glycine max | NCBI GSS | Mixed genome reads |

| Lotus japonicus | NCBI NR | Phase 3 BAC and TAC clones |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | NCBI NR | Complete genome |

| Oryza sativa | NCBI NR | Draft genome data |

| Transcript-based sequences | ||

| All species | NCBI dbEST | cDNA single pass |

| NCBI unigene | Clustered ESTs | |

All data were collected from NCBI databases in February, 2004.

NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; HTGS, high-throughput genome sequence; NR, nonredundant; GSS, genome survey sequence; dbEST, database of expressed sequence tags.

Development of SSR markers:

SSRs of longer than 15 nucleotides were selected for the development of genetic markers from sequenced BACs of M. truncatula. Oligonucleotide primer design was automated by combining the Primer3 software (Rozen and Skaletsky 2000) with SSRIT (Temnykh et al. 2001) by means of a simple Perl script. Briefly, SSRs of >15 nucleotides were first identified by SSRIT and then the repeat region and surrounding sequence (∼400 bases to either side) were extracted for primer design. The Primer3 software was configured to design five sets of oligonucleotide primers flanking each SSR with a target amplicon size range of 100–300 bp. Primer specifications were melting temperature (Tm) ∼57–63° (target 60°) with ΔTm <1° for each primer pair and a primer length of ∼18–27 nucleotides (target 20 nucleotides). Three oligonucleotide sets were generally tested to discover polymorphisms for each BAC clone. PCR was performed in a total volume of 10 μl [10 ng of genomic template DNA, 1× PCR buffer, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 0.25 mm of each dNTPs, 5 μM of each primer, and 0.5 unit of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen)] with a temperature profile of 3 min at 95°, 35 cycles of 20–30 sec at 94–95°, 20–30 sec at 55°, 1 min at 72°, and a final 5 min extension step at 72°. PCR products were resolved on a 2–4% agarose gel and bands were visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. Primers that produced easily scored polymorphisms (length variation and dominant inheritance) were selected as genetic markers for mapping. In some cases, BAC clones were mapped on the basis of simple length polymorphisms, single strand conformational polymorphisms (SSCP), or differential restriction sites (i.e., cleavable amplified polymorphic sequences or CAPS) identified between the two parental alleles. SSCP analysis was performed according to Vincent et al. (2000), with silver staining of polyacrylamide gels according to Bassam and Caetano-Annoles (1993).

Mapping of SSRs—integration of sequenced BAC clones into the genetic map:

To facilitate genotyping and map integration, a subset of 69 individuals from an earlier mapping population (Choi et al. 2004a) was used. The genetic map reported by Choi et al. (2004a,b) included 288 sequence-characterized genetic markers on the same base-mapping population. Using this strategy we integrated 320 new SSR markers and 29 non-SSR markers into the existing genetic map. Plant genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Plant 96 Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's directions. For purposes of marker genotype analysis, the F2 DNAs were analyzed in parallel with three control DNAs (A17 maternal homozygous line, A20 paternal homozygous line, and F1 heterozygote DNA). The PCR products were resolved as described above and genotypes were recorded as follows: homozygous maternal (A17) “A”, homozygous paternal (A20) “B”, heterozygous “H”, not A “C”, not B “D”, and missing data “-”. Genotypes for all markers were integrated into a color-coded genotype matrix using Excel (Kiss et al., 1998). Markers were assigned to chromosomes using the “Make Linkage Groups” command of Map Manager QTX (Manly et al. 2001). Genetic distances were calculated on the basis of the Kosambi function. Markers with an LOD > 3.0 were integrated into a framework map, while those with LOD < 3.0 or ambiguous genotypes were tentatively assigned to intervals by visual inspection of the color-coded genotype matrix. In addition to mapping BAC clones by means of SSRs, we also used BLASTN to compare the sequences of previously mapped genetic markers (Choi et al. 2004a,b) with sequenced BAC clones of M. truncatula. In cases where BLASTN results revealed perfect matches, genetic markers and BAC clones were assumed to represent the same locus.

RESULTS

As a prelude to development of microsatellite genetic markers in M. truncatula, we examined the profile of perfect microsatellites within the M. truncatula genome and compared it to that of the legumes L. japonicus and soybean, and the model species Arabidopsis and rice. The sequence types used for analysis varied by species (Table 1), primarily as a function of the data available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Because rates of SSR mutation are positively correlated with SSR length (Ellegren 2004), we divided SSRs into two classes based on size (class I, ≥20 bp; class II, 12 to ≤19 bp). SSRs with lengths of 20 nucleotides and greater tend to be highly mutable (Temnykh et al. 2001), while SSRs with lengths between 12 and 19 nucleotides tend to be moderately mutable (Pupko and Graur 1999).

Frequency of perfect microsatellites in genomic DNA sequence:

The frequency of perfect microsatellites in Medicago genomic DNA is shown in Table 2, along with similar calculations for soybean, L. japonicus, Arabidopsis, and rice. Despite differences in the nature and quantity of genomic sequence analyzed, the major trends were similar across species. Thus, class II SSRs (12–19 nt) were the most abundant microsatellites and occurred at similar frequencies in all five species, with an average density of one SSR every 0.6–0.7 Mbp. In Medicago, hexa- and heptanucleotide repeats accounted for 65% of these short genomic microsatellites, with di- and pentanucleotide repeats being the most infrequent. These same patterns characterize the other four genomes. The major evident differences between the monocot (rice) and dicot (Medicago, Lotus, soybean, and Arabidopsis) species were a twofold increase in the frequency of trinucleotide repeats and an underrepresentation in the frequency of mononucleotide repeats in rice compared with dicots.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of microsatellites per million base pairs in genomic and EST sequences of five plant species

| Plant species

|

Sequence length (Mbp)

|

G/C content (%)

|

Frequency of class II SSRs (SSR/Mbp)

|

Average distance (kbp)

|

Frequency of class I SSRs (SSR/Mbp)

|

Average distance (kbp)

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono- | Di- | Tri- | Tetra- | Penta- | Hexa- | Hepta- | Octa- | Mono- | Di- | Tri- | Tetra- | Penta- | Hexa- | Hepta- | Octa- | |||||

| Genomic sequences | ||||||||||||||||||||

| M. truncatula | 77.13 | 33.4 | 184.2 | 43.7 | 98.8 | 128.2 | 44.1 | 812.7 | 270.6 | 88.1 | 0.6 | 19.7 | 37.5 | 9.5 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 2.4 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 12.1 |

| Soybean | 20.15 | 36.0 | 75.9 | 52.4 | 96.5 | 119.9 | 31.4 | 749.4 | 256.7 | 73.5 | 0.7 | 6.1 | 63.0 | 43.2 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 1.4 | 7.4 | 0.3 | 7.8 |

| L. japonicus | 26.92 | 36.6 | 62.7 | 47.0 | 118.4 | 101.08 | 36.3 | 821.5 | 284.2 | 85.9 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 24.0 | 11.4 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 16.9 |

| Arabidopsis | 119.10 | 36.0 | 103.0 | 57.5 | 138.0 | 92.2 | 29.1 | 732.4 | 223.1 | 70.4 | 0.7 | 11.7 | 21.4 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 1.5 | 5.8 | 0.7 | 18.4 |

| Rice | 474.66 | 43.5 | 44.8 | 69.3 | 204.7 | 127.6 | 37.9 | 804.1 | 232.6 | 85.3 | 0.6 | 2.3 | 29.8 | 13.9 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 14.7 |

| Bulk EST sequences | ||||||||||||||||||||

| M. truncatula | 100.93 | 41.1 | 3.8a | 34.8 | 167.7 | 69.0 | 20.4 | 760.1 | 161.7 | 37.8 | 0.8 | 0.7a | 16.6 | 12.3 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 21.6 |

| Soybean | 157.92 | 43.5 | 4.3a | 39.8 | 170.3 | 70.2 | 16.0 | 805.7 | 131.4 | 32.7 | 0.8 | 0.8a | 20.1 | 12.4 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 21.5 |

| L. japonicus | 13.92 | 47.3 | 1.4a | 59.1 | 326.4 | 59.3 | 18.8 | 1015.2 | 127.5 | 46.0 | 0.6 | 0.0a | 20.3 | 35.6 | 3.2 | 5.4 | 17.6 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 11.8 |

| Arabidopsis | 83.36 | 43.1 | 6.1a | 49.1 | 217.6 | 60.0 | 12.8 | 697.8 | 133.4 | 36.9 | 0.8 | 1.3a | 8.1 | 11.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 38.8 |

| Rice | 135.30 | 49.5 | 27.5a | 41.6 | 409.8 | 122.2 | 27.7 | 879.8 | 145.1 | 54.3 | 0.6 | 1.7a | 10.2 | 24.1 | 5.2 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 18.4 |

| NCBI unigene sequences | ||||||||||||||||||||

| M. truncatula | 3.56 | 60.4 | 3.1a | 24.2 | 113.3 | 67.2 | 21.4 | 688.8 | 146.7 | 47.8 | 0.9 | 1.1a | 6.2 | 9.0 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.0 | 34.9 |

| Soybean | 10.10 | 43.9 | 2.2a | 30.4 | 96.0 | 61.6 | 13.5 | 597.3 | 143.9 | 44.6 | 1.0 | 0.3a | 12.2 | 7.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 37.0 |

| L. japonicus | 4.34 | 43.4 | 2.5a | 23.9 | 113.3 | 71.4 | 16.1 | 682.5 | 173.3 | 43.3 | 0.9 | 0.5a | 9.7 | 7.6 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 33.2 |

| Arabidopsis | 33.54 | 39.7 | 1.3a | 39.9 | 235.8 | 43.6 | 11.7 | 670.1 | 116.0 | 34.4 | 0.9 | 0.2a | 6.6 | 15.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 36.3 |

| Rice | 47.78 | 49.9 | 6.8a | 38.5 | 477.10 | 98.6 | 33.7 | 952.1 | 156.0 | 58.4 | 0.6 | 0.5a | 12.0 | 39.7 | 4.9 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 13.4 |

Class II SSRS: mono- (T = 3.43, P < 0.01), penta- (T = 4.60, P < 0.01), hepta- (T = 8.74, P < 0.01), and octanucleotide (T = 7.40, P < 0.01) repeats are more abundant in genomic compared to EST data. Class I SSRs: only heptanucleotide repeats are significantly different in abundance between genomic and EST data sets (T = 3.27, P < 0.01). Mono-, mononucleotide repeats; Di-, dinucleotide repeats; Tri-, trinucleotide repeats; Tetra-, tetranucleotide repeats; Penta-, pentanucleotide repeats; Hexa-, hexanucleotide repeats; Hepta-, heptanucleotide repeats; Octa-, octanucleotide repeats.

Mononucleotide repeats for EST sequences included only poly (C/G) repeat type.

In all species analyzed, dinucleotide repeats were the most abundant genomic class I (long) microsatellites, with frequencies similar to those observed in class II (short) dinucleotide repeats. The frequencies of all other genomic class I microsatellites were substantially reduced relative to their class II counterparts, with hexa- and heptanucleotide repeats 35- to 700-fold less frequent in the class I fraction compared to class II. A number of species-related differences were observed in the genomic class I frequency data. Thus, mononucleotide repeats were the second most abundant genomic class I microsatellite for Medicago and Arabidopsis, a situation that was also observed for class II mononucleotide repeats. By contrast, for soybean, rice, and Lotus, trinucleotide repeats were the second most abundant genomic class I microsatellite. Interestingly, genomic class I microsatellites were two- to threefold more abundant in soybean genomic DNA by comparison to the other species, primarily due to an elevated occurrence of di- and trinucleotide repeats. We note that a large fraction of soybean genomic sequence information corresponds to RFLP clones and thus may not represent a random sample of genomic DNA.

Frequency of perfect microsatellites in transcript sequence:

For analysis of transcript data, we compared SSR frequencies in two data sets: bulk nonclustered ESTs and the NCBI unigene set. As shown in Table 2, despite the redundant and asymmetric nature of bulk EST data, the relative and absolute frequencies of microsatellites showed good correspondence between the bulk EST and NCBI unigene data sets. Moreover, as in the case of genomic DNA, trends were similar between species.

Class II SSRs were significantly more abundant (i.e., one SSR every 0.6–1.0 Mbp) in transcript data compared to their class I counterparts (i.e., one SSR every 13–39 Mbp), similar to the situation observed in genomic DNA. Thus, 54–91% of bulk EST sequences contained class II SSRs, depending on the species under analysis, while only 1–3% of ESTs contained class I SSRs. The most abundant class II SSRs were tri-, hexa- and heptanucleotide motifs, consistent with observations made in a wide range of species (Ellegren 2004), while class I SSRs were most frequently repeats of di- and trinucleotide motifs. On the basis of analysis of the NCBI unigene set, the frequency of class I and class II SSRs is similar in the transcript data of all four dicot species, and substantially less frequent than that observed in rice.

Class I SSRs—frequency of individual motifs:

To compare the frequency of specific long-repeat motifs within and between genomes, we examined each of the 16 possible mononucleotide, dinucleotide, and trinucleotide motifs of class I SSRs in each of the five species (Table 3). In all species, the abundance of dinucleotide repeats in genomic DNA (Table 2) could be attributed to an overrepresentation of AT motifs; soybean in particular exhibits a two- to threefold increase in AT-motif frequency relative to the other four species analyzed. By contrast, the high frequency of dinucleotide repeats in EST sequences could be attributed to an abundance of AG repeats (Table 3). The frequency of AG-balanced repeats in bulk EST data was especially high in legumes, with values two- to threefold higher than their frequency in rice and Arabidopsis.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of individual class I microsatellite motifs per million base pairs in genomic and EST sequences of five plant species

| Genomic sequences

|

EST sequences

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat motif | M. truncatula | Soybean | L. japonicus | Arabidopsis | Rice | M. truncatula | Soybean | L. japonicus | Arabidopsis | Rice |

| A/Ta | 18.4 | 5.8 | 1.0 | 11.5 | 0.8 | — | — | — | — | — |

| C/Ga | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| AT/TA | 27.2 | 52.9 | 15.7 | 16.5 | 18.4 | 2.4 | 7.0 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 2.1 |

| AG/GA/CT/TC | 8.1 | 6.6 | 7.0 | 4.1 | 9.1 | 13.6 | 12.5 | 18.5 | 5.3 | 7.4 |

| AC/CA/TG/GT | 2.2 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| GC/CG | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 |

| AAT/ATA/TAA/ATT/TTA/TAT | 5.1 | 39.3 | 3.7 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| AAG/AGA/GAA/CTT/TTC/TCT | 2.0 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 6.4 | 2.9 | 14.0 | 5.8 | 2.8 |

| AAC/ACA/CAA/GTT/TTG/TGT | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| ATG/TGA/GAT/CAT/ATC/TCA | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 0.4 |

| AGT/GTA/TAG/ACT/CTA/TAC | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| AGG/GGA/GAG/CCT/CTC/TCC | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 5.1 | 0.4 | 3.8 |

| AGC/GCA/CAG/GCT/CTG/TGC | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.9 |

| ACG/CGA/GAC/CGT/GTC/TCG | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0 | 1.5 |

| ACC/CCA/CAC/GGT/GTG/TGG | 0.2 | 0 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 7.0 | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| GGC/GCG/CGG/GCC/CCG/CGC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0 | 11.7 |

| AT-rich repeatsb | 68.2 | 117.0 | 42.9 | 47.1 | 34.9 | 25.8 | 23.2 | 35.9 | 17.0 | 11.8 |

| AT/GC balanced repeatsb | 11.2 | 10.6 | 11.0 | 5.5 | 13.4 | 17.5 | 15.9 | 29.3 | 5.9 | 11.2 |

| GC-rich repeatsb | 3.5 | 1.2 | 5.2 | 1.9 | 19.5 | 3.1 | 7.5 | 19.3 | 2.9 | 31.3 |

AT repeats are more abundant in genomic compared to EST data (T = 3.25, P < 0.01). Specifically in the case of M. truncatula, soybean, and L. japonicus, AG repeats are more abundant in EST compared to genomic data (T = 4.02, P < 0.01).

Mononucleotide repeats for EST sequences included only poly (C/G) repeat type.

All class I SSRs were categorized according to their AT contents.

Taken together, the relative distribution of specific di- and trinucleotide repeats reflects both the increased GC content of coding vs. noncoding genome regions and the higher GC content of monocots as compared to dicots. In particular, the results demonstrate a partitioning of (AT)n and (AG)n repeats between noncoding and coding regions. Interestingly, (GC)n dinucleotide repeats were rare in all of the genomes analyzed. The scarcity of poly(C) and (GC)n repeats has been observed in a broad range of species, from yeast to vertebrates and plants (Tóth et al. 2000). This low frequency of poly(C) and (GC)n repeats in various genomes has been attributed to methylation of cytosine, which can increase rates of mutation to thymine; however, methylation cannot explain the rarity of poly(C) and (GC)n repeats in C. elegans, Drosophila, or yeast, where cytosine methylation is uncommon (Katti et al. 2001). An alternative explanation is that (GC)n repeats are selected against due to the increased stability of (GC)n hairpin structures.

In the case of trinucleotide repeats, the dicot species contained higher frequencies of AT-rich repeats in both genomic DNA and EST sequence relative to rice. Soybean in particular possessed an ∼10-fold increase in the genomic AAT trinucleotide motif relative to Medicago and Lotus and a 20- to 40-fold increase relative to rice and Arabidopsis. The opposite was true for GC-rich trinucleotide repeats, which were the predominant trinucleotide motif in rice (Kantety et al. 2002) and either rare or absent from the dicot genomes. Perfect repeats with motifs longer than trinucleotides (i.e., tetranucleotide to octanucleotide repeats) were predominantly AT-rich motifs in all of genomes analyzed (data not shown).

Distribution of class I microsatellites in the genome of M. truncatula:

To characterize the spatial distribution of class I repeats with respect to genic and nongenic features of the M. truncatula genome, we examined the distribution of perfect microsatellites >20 nt in (1) 51 completely sequenced and annotated gene-rich BAC clones (6.3 Mbp), (2) a random low-pass whole genome shotgun data set (20 Mbp), and (3) a random BAC-end sequence data set (49 Mbp; Table 4). The complete BAC clone sequences used for analysis were part of a larger data set of 778 sequenced BAC clones. These 778 BAC clones were selected to represent euchromatic (presumably gene-rich) regions of the genome on the basis of a combination of genetic and cytogenetic mapping (Choi et al. 2004a; Kulikova et al. 2001) or on the basis of homology to transcript sequences. We first determined that the frequency of SSRs in the 51 annotated BACs (Table 4, row 4) was not significantly different from that of the larger data set of 778 sequenced BAC clones (Table 2, class I SSRs, row 1) (Pearson χ2 = 1.23, d.f. = 7, at α = 0.05).

TABLE 4.

Frequency of Class I microsatellites in selected genome fractions of M. truncatula

| Frequency of SSRs (SSR/Mbp)

|

Average distance (kbp)

|

Sequence length (Mbp)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome fraction | Mono- | Di- | Tri- | Tetra- | Penta- | Hexa- | Hepta- | Octa- | ||

| Whole genome shotgun sequences | —a | 14.5 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 36.7a | 20.4 |

| BAC-end sequences showing BLAST matchb | —a | 25.9 | 7.0 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 21.7a | 23.0 |

| BAC-end sequences without BLAST matchb | —a | 24.7 | 6.8 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 23.6a | 25.8 |

| Selected BACs | 19.5 | 33.8 | 8.9 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 12.5 | 6.3 |

| Nontranscribed region | 23.5 | 44.3 | 9.7 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 10.5 | 2.9 |

| Transcribed region | 16.0 | 24.7 | 8.1 | 4.8 | 3.3 | 5.1 | 3.6 | 0.9 | 15.0 | 3.4 |

| 5′-UTR | 25.9 | 60.3 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 8.6 | 3.4 | 7.4 | 0.6 |

| Exon | 0 | 0.9 | 6.1 | 0 | 1.8 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 | 76.0 | 1.1 |

| Intron | 24.9 | 26.4 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 0.8 | 13.2 | 1.3 |

| 3′-UTR | 22.9 | 37.1 | 11.4 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 8.6 | 5.7 | 0 | 10.6 | 0.4 |

Mono-, mononucleotide repeats; Di-, dinucleotide repeats; Tri-, trinucleotide repeats; Tetra-, tetranucleotide repeats; Penta-, pentanucleotide repeats; Hexa-, hexanucleotide repeats; Hepta-, heptanucleotide repeats; Octa-, octanucleotide repeats.

Mononucloetide repeats in the whole genome shotgun sequences and BAC-end sequences were not considered because of low quality of untrimmed poly (N) tracks in the raw data.

BAC-end sequences were categorized into two datasets according to the result of BLASTN against MtGI Rel. 6.0 with cutoff E−10.

In M. truncatula, ∼60% of the genome can be attributed to repeat-rich and gene-poor heterochromatin located within pericentromeric regions of the genome (Kulikova et al. 2004). As described above, the completely sequenced BAC clones were intentionally enriched for gene-rich euchromatic DNA, while the whole genome-shotgun and BAC-end sequence data sets were derived from randomly selected clones that are presumably more representative of the genome as a whole. Comparison of these three genomic data sets revealed that, with the exception of mononucleotide repeats, SSR frequency was 2.3- to 1.4-fold higher in gene-rich BAC clones (63.2 SSR/Mbp) compared to that of random whole genome shotgun sequences (27.3 SSR/Mbp) or random BAC-end sequences (44.2 SSR/Mbp). The finding that SSRs have intermediate frequency in the BAC-end sequence data suggests that the BAC library used for end sequencing might be enriched for gene-rich regions of the genome. This conclusion is supported by the observation that the major classes of centromere-like tandem repeats (i.e., MtR1, MtR2, and MtR3), which together compose 7% of the genome (Kulikova et al. 2004), are underrepresented in BAC-end sequence data (data not shown). As a further test of this conclusion, we analyzed SSR frequency in the portion of the shotgun sequence data set with homology to the tandemly arrayed centromere-like repeats, MtR1, MtR2, and MtR3. SSR frequency in this repetitive genome fraction was 7.0 SSR/Mbp, or ninefold less frequent than values obtained with completely sequenced BAC clones. The association of class I SSRs with gene-rich fractions of the genome was also evident in the comparison of BAC-end sequences having homology to ESTs vs. those without homology to ESTs. In particular, BAC-end sequences with BLASTN similarity to ESTs of M. truncatula had ∼10% higher average SSR frequencies (46.0 SSR/Mbp) than that of BAC-end sequences without BLASTN similarity (42.4 SSR/Mbp). These data are in agreement with the previous report of Morgante et al. (2002), in which SSRs were observed to be preferentially associated with the nonrepetitive fractions of plant genomes.

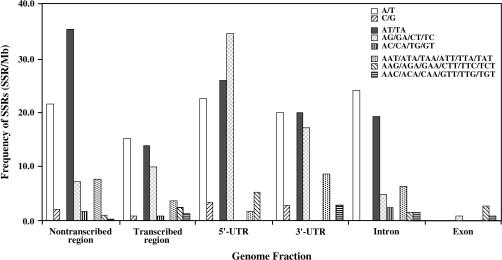

To correlate SSRs with specific genic and nongenic fractions, we annotated the 51 completely sequenced BAC clones by means of the dicot version of FGENESH and assigned five categories of sequence, namely, (1) nontranscribed, (2) 5′-untranslated exon (5′-UTR), (3) coding exon, (4) intron, and (5) 3′-untranslated exon (3′-UTR). The 51 BAC clones contained an average of 20.3 predicted genes per clone, with 1 gene per 6.0 kbp. As shown in Table 4, class I SSRs were slightly more frequent in predicted nontranscribed compared to predicted transcribed regions of gene-rich BAC clones, due primarily to a higher frequency of mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats. However, SSR frequency varied considerably between the different predicted transcribed fractions (χ2 = 57.35, d.f. = 21, P < 0.001). Most SSRs in transcribed regions were detected in 5′- and 3′-untranslated fractions and within introns, with the highest SSR frequency in 5′-UTRs, which were characterized by elevated levels of di-, penta-, hexa-, and heptanucleotide motifs. Predicted exons were substantially underrepresented in all SSR motif lengths, with the exception of trinucleotide and hexanucleotide repeats. Figure 1 presents the distribution of the eight most abundant SSR motifs relative to the five genome fractions. Consistent with the results shown in Table 3, AT-rich di- and trinucleotide motifs were more abundant in nontranscribed than in transcribed regions. This bias was also evident within transcribed regions, where AT-rich repeats were relatively abundant in transcribed nontranslated regions and essentially absent in exon sequences.

Figure 1.

Frequency of eight most abundant microsatellite motifs in deduced genome fractions of M. truncatula. Separation of M. truncatula genomic sequence into transcribed and nontranscribed fractions, and further into untranslated regions (5′ and 3′ UTRs), exons and introns, is based on the output of the Arabidopsis of FGENESH (http://www.softberry.com).

Development of SSR markers in M. truncatula:

With the goal of establishing genetic map positions for sequenced BAC clones and the corresponding physical contigs, we used the Primer3 software to design multiple sets of PCR primers flanking SSR motifs. In total, 1236 primer pairs were tested for PCR amplification of genomic DNA from M. truncatula genotypes A17 and A20 (Table 5), representing 148 class II SSRs of longer than 15 nucleotides and 1088 class I SSRs. A total of 801 (64.8%) of the primer pairs yielded an amplification product. The efficiency of amplification was highest for class II SSRs (79.1%) compared to the larger class I SSRs (62.9%), with the exception of poly (A) and hexanucleotide repeats (Table 5). Amplification was least efficient for (AT)n and (AAT)n class I repeats, which together represent 39% of all class I repeats in the M. truncatula genome (Table 2). Similar results were reported for rice (Temnykh et al. 2001). It is possible that the secondary structure of repeats (e.g., hairpins; Trotta et al. 2000) or specific sequences around microsatellites may affect annealing of primers or polymerase processivity.

TABLE 5.

Development of SSR makers for A17 and A20 mapping population of M. truncatula

| Tested primer pairs

|

PCR amplification (%)

|

Polymorphic SSRs (%)

|

Mean length of polymorphic SSR (bp)

|

No. of mapped markers

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat type | Motif | Class I | Class II | Subtotal | Class I | Class II | Subtotal | Class I | Class II | Subtotal | ||

| Mono- | 37 | 9 | 46 | 83.8 | 77.8 | 82.6 | 87.1 | 28.6 | 76.3 | 23.5 | 10 | |

| A/T | 35 | 9 | 44 | 82.9 | 77.8 | 81.8 | 86.2 | 28.6 | 75.0 | 23.6 | 10 | |

| C/G | 2 | — | 2 | 100 | — | 100 | 100 | — | 100 | 21.5 | 0 | |

| Di- | 852 | 46 | 898 | 60.4 | 73.9 | 60.7 | 82.1 | 70.6 | 81.4 | 41.1 | 227 | |

| AT/TA | 621 | 22 | 643 | 58.5 | 72.7 | 58.9 | 84.0 | 68.8 | 83.4 | 43.8 | 135 | |

| AG/GA/CT/TC | 181 | 16 | 197 | 64.1 | 75.0 | 65.0 | 77.6 | 75.0 | 77.3 | 37.3 | 73 | |

| AC/CA/TG/GT | 50 | 8 | 58 | 72.0 | 75.0 | 72.4 | 77.8 | 66.7 | 76.2 | 27.1 | 19 | |

| Tri- | 160 | 57 | 217 | 66.3 | 78.9 | 68.7 | 78.3 | 40.0 | 66.9 | 30.3 | 66 | |

| AAT/ATA/TAA/ATT/TTA/TAT | 102 | 25 | 127 | 62.7 | 68.0 | 63.8 | 84.4 | 29.4 | 72.8 | 33.4 | 31 | |

| AAG/AGA/GAA/CTT/TTC/TCT | 30 | 11 | 41 | 66.7 | 90.9 | 73.2 | 65.0 | 50.0 | 60.0 | 31.9 | 17 | |

| AAC/ACA/CAA/GTT/TTG/TGT | 10 | 9 | 19 | 80.0 | 77.8 | 78.9 | 75.0 | 57.1 | 66.7 | 20.7 | 10 | |

| ATG/TGA/GAT/CAT/ATC/TCA | 6 | 6 | 12 | 50.0 | 100 | 75.0 | 100 | 33.3 | 55.6 | 22.8 | 2 | |

| AGT/GTA/TAG/ACT/CTA/TAC | 2 | 1 | 3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | — | 66.7 | 25.5 | 1 | |

| AGG/GGA/GAG/CCT/CTC/TCC | 5 | 1 | 6 | 80.0 | 0 | 66.7 | 50.0 | — | 50.0 | 28.5 | 2 | |

| ACC/CCA/CAC/GGT/GTG/TGG | 5 | 2 | 7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 60.0 | 50.0 | 57.1 | 27.0 | 2 | |

| AGC/GCA/CAG/GCT/CTG/TGC | 0 | 2 | 2 | — | 100 | 100 | — | 50.0 | 50.0 | 15.0 | 1 | |

| Tetra- | 14 | 14 | 28 | 64.3 | 85.7 | 75.0 | 77.8 | 33.3 | 52.4 | 17.8 | 5 | |

| Penta- | 9 | 2 | 11 | 88.9 | 100 | 90.9 | 100 | 50.0 | 90.0 | 27.8 | 3 | |

| Hexa- | 11 | 20 | 31 | 100 | 85.0 | 90.3 | 81.8 | 52.9 | 64.3 | 22.0 | 9 | |

| Hepta- | 4 | — | 4 | 75.0 | — | 75.0 | 66.7 | — | 66.7 | 21.0 | 0 | |

| Octa- | 1 | — | 1 | 100 | — | 100 | — | — | 0 | — | — | |

| Total | 1088 | 148 | 1236 | 62.9 | 79.1 | 64.8 | 81.7 | 49.6 | 77.0 | 37.3 | 320 | |

Mono-, mononucleotide repeats; Di-, dinucleotide repeats; Tri-, trinucleotide repeats; Tetra-, tetranucleotide repeats; Penta-, pentanucleotide repeats; Hexa-, hexanucleotide repeats; Hepta-, heptanucleotide repeats; Octa-, octanucleotide repeats.

A total of 617 (77.0%) of the 801 amplified SSR loci were polymorphic between M. truncatula genotypes A17 and A20. For comparison, the SNP frequency for these two genotypes is ∼1/500 bp for exon sequences and ∼1/140 bp for intron sequences (Choi et al. 2004a). Class I SSRs (559 or 81.7%) were significantly more polymorphic than class II SSRs (58 or 49.6%). The highest rates of polymorphism were observed for (AT)n, (AG)n, (AC)n, and (AAT)n motifs, the most abundant motifs in the M. truncatula genome. Polymorphism rates increased with the number of repeat units: 5-fold, <60%; ∼5- to 10-fold, 66%; ∼11- to 15-fold, 71%; ∼16- to 20-fold, 77%; ≥20-fold 82%.

Anchoring of sequenced BACs to the genetic map:

For purposes of integrating the BAC-based physical map of M. truncatula with the genetic and cytogenetic maps, the genotypes of 317 of 617 polymorphic SSRs were scored in a reference mapping population. The remaining 300 SSRs were considered redundant, as they were derived from BACs that were already mapped by means of other SSRs. A total of 71% of the mapped SSR polymorphisms were derived from dinucleotide repeats, and 29 additional markers were developed on the basis of CAPS, SSCP, or length polymorphisms associated with BAC clone sequences. As shown in Figure 2, these 346 new genetic markers were integrated into an existing genetic map of M. truncatula (Choi et al. 2004a,b), bringing the total number of markers mapped in this population to 634, including 378 genetically mapped BAC clones. In total, these BAC-based markers integrate 274 BAC contigs from the M. truncatula physical map (Table 6). A detailed list of marker attributes and clone GenBank accession numbers is given in supplemental Table S1 (http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

Figure 2.

Molecular genetic map of M. truncatula. SSR genetic markers analyzed in this study are designated by the prefix MtB, for Medicago truncatula BAC-based STS markers. The correspondence between SSR markers and BAC clones is given in supplemental Table S1 (http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). Markers not notated as MtB correspond to 210 previously reported genetic markers (Choi et al. 2004a,b) that are used here for purposes of integrating the data from the various studies. Two categories of genetic loci were obtained from the current analysis: (1) framework markers (LOD > 3.0), which are connected to linkage groups by horizontal or diagonal lines, and (2) interval markers (LOD < 3.0) whose positions are denoted by vertical lines that delimit inferred genetic intervals. Markers separated by a period derive from the same BAC clone. Conflicts between SSR-mapped BAC clones and previously inferred genetic marker–BAC associations (Choi et al. 2004a) are designated by superscript letters.

TABLE 6.

Summary of map length, mapped markers, framework loci, average map density per framework loci for the map, and number and length of anchored physical contigs

| Linkage group

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG1 | LG2 | LG3 | LG4 | LG5 | LG6 | LG7 | LG8 | Total | Average | |

| Map distance (cM) | 63.6 | 65.4 | 95.0 | 63.8 | 80.3 | 53.9 | 71.4 | 73.1 | 566.5 | 70.8 |

| No. of BAC-based STS markers | 46 | 45 | 47 | 52 | 44 | 19 | 44 | 49 | 346 | 43.3 |

| SSR marker | 37 | 42 | 47 | 46 | 40 | 18 | 41 | 46 | 317 | 39.6 |

| Other marker | 9 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 29 | 3.6 |

| No. of EST-based marker | 20 | 20 | 37 | 34 | 32 | 22 | 17 | 28 | 210 | 26.3 |

| Framework loci | 25 | 21 | 30 | 31 | 24 | 19 | 26 | 30 | 206 | 25.8 |

| Loci assigned to interval | 18 | 18 | 7 | 16 | 18 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 102 | 12.8 |

| Average map density per framework loci (cM) | 2.5 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.4 | — | 2.8 |

| No. of mapped BACs | 47 | 49 | 52 | 61 | 49 | 23 | 47 | 53 | 381 | 47.6 |

| No. of anchored physical contigs | 38 | 36 | 41 | 38 | 34 | 17 | 32 | 38 | 274 | 34.2 |

| Length of physical contigs (Mbp) | 23.1 | 20.1 | 26.3 | 29.7 | 18.3 | 13.7 | 19.8 | 23.1 | 174.1 | 21.8 |

SSR markers continue to be added to the genetic map, furthering the integration of genetic and physical map resources in this species and providing additional anchoring for the ongoing genome sequencing effort, with updates available through http://www.medicago.org/genome [Medicago truncatula community web site and databases, including the home page (i.e., /genome) for the genome sequencing project]. As of August 4, 2005, 1243 sequenced BAC clones were mapped, either directly by means of BAC-based SSRs or by virtue of their association with genetically mapped physical map contigs. Thus, of ∼150 Mbp of nonredundant genome sequences obtained as of August 2005, ∼130 Mbp of sequenced genome, representing an estimated 21,000 predicted genes, has been associated to chromosomal loci by means of genetic mapping of physical contigs. The extent of the physical map (including not-yet-sequenced BAC clones) associated to genetic loci is ∼242 Mbp, or 48% of the total genome and an estimated 88% of the predicted gene space.

DISCUSSION

The utility of microsatellites for genetic, genomic, and evolutionary studies derives from their high rates of polymorphism, simple-to-score length variation, and the ease with which they can be mined from genomic and EST sequence data. Here we report a detailed analysis of perfect microsatellites >12 nucleotides in M. truncatula and a comparison of SSR frequency and type between M. truncatula and those of other legume species and model plants. Analysis of genomic and EST sequences of M. truncatula, soybean, L. japonicus, Arabidopsis, and rice revealed that the frequency of SSRs was 1.3- to 2.8-fold higher in genomic sequences as compared to bulk EST sequences, with the exception of L. japonicus (Table 2). This result contradicts the report of Morgante et al. (2002) in which the frequency of microsatellites was higher in ESTs than in genomic DNA of plant species. Here we analyzed a significantly larger data set (i.e., a 5- to 20-fold increase, depending on species) than that analyzed by Morgante et al. (2002). Given the nonrandom distribution of SSRs in plant genomes, and in particular their frequent association with nonrepetitive sequences (Cardle et al. 2000; McCouch et al. 2002), it is possible that small data sets yield unreliable predictions of SSR distribution.

The frequency of class II SSRs in genomic DNA was similar across all plant genomes analyzed in this study (0.6–0.7 SSR/kbp, Table 2). By contrast, the frequency of class I SSRs was both lower and more variable across genomes. In particular, class I SSRs were 1.5- to 2.5-fold more frequent for soybean compared to the other genomes analyzed. This increase is correlated with the larger size of the soybean genome and also with the fact that the public genome sequence data for soybean is enriched in RFLP-derived genomic clones relative to the other species we analyzed. Although it is uncertain whether either of these factors is causal to the increased frequency of class I SSRs in soybean data, it is noteworthy that Ross et al. (2003) have recently described the rapid divergence of microsatellite abundance among closely related species. Wierdl et al. (1997; and more recently Kruglyak et al. 1998; Katti et al. 2001) proposed that the lower frequency of long vs. short SSRs may result from selection against mutagenic sites in the genome. It is possible that the polyploid nature of the soybean genome might reduce selection against long microsatellites due to the redundancy of homeologous regions, but if so then the relaxed selection must be specific to noncoding regions, as the frequency of class I SSRs within coding regions (i.e., the NCBI unigene set) was similar between soybean and the other dicot genomes (Table 2).

Analysis of individual class I SSR motifs revealed additional taxon-specific patterns, especially with respect to the types and distribution of dinucleotide and trinucleotide repeats. Thus, (AAT)n and (AG)n were overrepresented in the genomic and EST fractions, respectively, of legume species, but relatively underrepresented in Arabidopsis and rice (Table 3). By contrast, (GGC)n repeats were predominant in the rice genome but not in the dicot genomes. In general the rice genome exhibited a higher rate of class I SSRs (threefold) and class II SSRs (1.5-fold) within the unigene data set, indicating that rice is likely to be a relatively rich source of transcript-associated polymorphisms. Taxon-specific accumulation of repeats in eukaryotic genomes has been reported for several species (Tóth et al. 2000; Katti et al. 2001). The current results, and in particular the similarity between the related legume genomes, suggest that taxon-specific motifs originated after divergence of legumes from Arabidopsis and rice. Strand-slippage theories alone are insufficient to explain the differential abundance of specific motif types in different genomes. A positive selection pressure, such as a preference of codon usage in exons or a regulatory effect of specific repeats in noncoding regions, may underlie the taxa-specific accumulation of certain repeat motifs.

In contrast to the classical definition of SSRs as motifs of 1–6 bp in length (Tautz, 1989), the current analysis also considered motifs with lengths of 7 and 8 bp. The frequencies and distribution of hepta- and octanucleotide repeats were consistent with those observed for motifs of 1–6 bp, including correspondence across taxa (Table 2), a significantly higher frequency in class II compared to class I SSRs (Table 2), and a low frequency in exon regions (Table 4, except tri- and hexanucleotide repeats). Interestingly, motifs of 7 bp were the second most abundant class II SSR motif length, and they were as abundant as tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotide motifs in class I SSRs.

The current analysis of SSR distribution in M. truncatula agrees with previous reports for dicot genomes in which the majority of SSRs were found to reside in the nontranscribed fraction of gene-rich regions or within the untranslated portions of transcripts (i.e., UTRs and introns). The rare Medicago SSRs in exons were typically AT-rich trinucleotide repeats (Figure 1). This contrasts to rice, in which GC-rich trinucleotide repeats were observed preferentially in exons (Cho et al. 2000).

The primary objective of this study was to integrate the physical and genetic maps of M. truncatula using microsatellites identified within sequenced BAC clones. By means of semiautomated SSR identification and primer design, 346 BAC clones have been incorporated into the existing genetic map, anchoring 174 Mbp of the physical map to genetic loci. During map integration, eight conflicts were identified between SSR-mapped BAC clones and previously inferred marker–BAC relationships (Choi et al. 2004a), as indicated in Figure 2. The possible origins of such conflicts include highly conserved duplicated genome segments, recently evolved gene paralogs, clone chimerism, and experimental error. Four of the conflicting relationships correspond to resistance gene clusters. Plant resistance genes are members of large gene families, often composed of recently derived paralogs, suggesting that these conflicts may arise from the misassignment of closely related genome regions that have distinct locations in the genetic map. The additional four conflicting BAC clone assignments may also derive from the misassignment of closely-related paralogous genes, as in each case the similarity between sequenced BAC clones and sequenced genetic markers was more consistent with paralogy than identity (89–98% identity). Such conflicts will resolve with additional genetic mapping and the progress of the whole genome sequencing effort in M. truncatula.

We note that more detailed analyses of the M. truncatula genome, as well as the genomes of G. max (soybean) and L. japonicus, will become possible as their genomes are better characterized. For example, here we have used FGENESH to predict transcribed vs. nontranscribed regions of the genomes. Recently, the International Medicago Genome Annotation Group has established standards for automated gene prediction, which is likely to increase the accuracy of gene calls relative to the FGENESH tool we have used here. Similarly, even more robust annotations will ultimately derive from experimental approaches, such as those based on the sequencing of full-length cDNA clones for a majority of transcripts. The current work has contributed to an increased characterization of microsatellites in legumes and their comparison to that of other model plant species. Moreover, these data increase the genetic and genomic resources available in M. truncatula by adding a new category of BAC-associated genetic markers and by facilitating integration of genetic and physical maps. Of practical importance, the positioning of physical map contigs to specific locations on linkage groups, and to cytogenetically defined chromosomes (e.g., Kulikova et al., 2001, 2004; Choi et al., 2004a), greatly aids the current genome-sequencing effort in which BACs are distributed according to chromosome assignments (Young et al., 2005). These microsatellite markers also provide tools to validate contig structure and orientation as a prelude to selection of BAC clones for sequencing. Although the ultimate goal of genome sequencing in M. truncatula is to produce pseudo-chromosome arms that cover the entire euchromatic space of M. truncatula (outlined in Young et al., 2005), a more immediate deliverable will be an assembly of ordered and oriented sequenced BAC contigs. Genetic mapping of sequenced BAC clones, largely based on the SSR strategy described here, is crucial to achieving these goals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Boehlke and Ryan Bretzel from the University of Minnesota for their technical assistance and G. Cardinet and Thierry Huguet for providing knowledge of certain SSR markers. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation to D.R.C., N.D.Y, and D.J.K. (DBI-0110206), from the European Union to G.B.K and F.D. (MEDICAGO QLG2-CT-2000-30676 and GLIP FOOD-CD-2004-506223), from Toulouse Midi-Pyrénées Génopole to F.D., and from the Hungarian National Grants Program to G.B.K. (NKFP 4/031/2004, OTKA T038211, T046645, and T046819, and GVOP 3.1.1-2004-05-0101/3.0). O.S. was supported by a grant from INRA Scientific Direction of Plants and Plant Products.

References

- Bassam, B. J., and G. Caetano-Anolles, 1993. Silver staining of DNA in polyacryamide gels. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 42: 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, M. D., and I. J. Leitch, 1995. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms. Ann. Bot. 76: 113–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cardle, L., L. Ramsay, D. Milbourne, M. Macaulay, D. Marshall et al., 2000. Computational and experimental characterization of physically clustered simple sequence repeats in plants. Genetics 156: 847–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y. G., T. Ishii, S. Temnykh, X. Chen, L. Lipovich et al., 2000. Diversity of microsatellites derived from genomic libraries and GenBank sequences in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 100: 713–722. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H., D. Kim, T. Uhm, E. Limpens, H. Lim et al., 2004. a A sequence-based genetic map of Medicago truncatula and comparison of marker co-linearity with Medicago sativa. Genetics 166: 1463–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.-K., J.-H. Mun, D.-J. Kim, H. Zhu, J.-M. Baek et al., 2004. b Estimating genome conservation between crop and model legume species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101: 15289–15294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, G. M., R. Casu, C. L. McIntyre, J. M. Manners and R. J. Henry, 2001. Microsatellite markers from sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) ESTs cross transferable to erianthus and sorghum. Plant Sci. 160: 1115–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decroocq, V., M. G. Fave, L. Hagen, L. Bordenave and S. Decroocq, 2003. Development and transferability of apricot and grape EST microsatellite markers across taxa. Theor. Appl. Genet. 106: 912–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Erfurth, I., V. Cosson, A. Eschstruth, H. Lucas, A. Kondorosi, et al., 2003. Efficient transposition of the Tnt1 tobacco retrotransposon in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 34: 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren, H., 2004. Microsatellites: simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5: 435–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eujayl, I, M. K. Sledge, L. Wang, G. D. May, K. Chekhovskiy et al., 2004. Medicago truncatula EST-SSRs reveal cross-species genetic markers for Medicago spp. Theor. Appl. Genet. 108: 414–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorova, M., J. van de Mortel, P. A. Matsumoto, J. Cho, C. D. Town et al., 2002. Genome-wide identification of nodule-specific transcripts in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 130: 519–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, K., C. le Signor, J. Vandekerckhove, R. D. Thompson and J. Burstin, 2003. Proteomics of Medicago truncatula seed development establishes the time frame of diverse metabolic processes related to reserve accumulation. Plant Physiol. 133: 664–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, M. V., M. C. Vaz Patto, T. Huguet, J. I. Cubero, M. T. Moreno et al., 2005. Cross-species amplification of Medicago truncatula microsatellites across three major pulse crops. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110: 1210–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imin, N., F. de Jong, U. Mathesius, G. van Noorden, N. A. Saeed et al., 2004. Proteome reference maps of Medicago truncatula embryogenic cell cultures generated from single protoplasts. Proteomics 4: 1883–1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journet, E. P., D. van Tuine, J. Gouzy, H. Crespeau, V. Carreau et al., 2002. Exploring root symbiotic programs in the model legume Medicago truncatula. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 5579–5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julier, B., S. Flajoulot, P. Barre, G. Cardinet, S. Santoni et al., 2003. Construction of two genetic linkage maps in cultivated tetraploid alfalfa (Medicago sativa) using microsatellite and AFLP markers. BMC Plant Biol. 3: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaté, K., I. D. Rodriguez-Llorente, M. Scholte, P. Durand, P. Ratet et al., 2000. Transformation of floral organs with GFP in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell Rep. 19: 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantety, R. V., M. La Rota, D. E. Matthews and M. E. Sorrells, 2002. Data mining for simple sequence repeats in expressed sequence tags from barley, maize, rice, sorghum and wheat. Plant Mol. Biol. 48: 501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katti, M. V., P. K. Ranjekar and V. S. Gupta, 2001. Differential distribution of simple sequence repeats in eukaryotic genome sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18: 1161–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, G. B., A. Kereszt, P. Kiss and G. Endre, 1998. Colormapping: a non-mathematical procedure for genetic mapping. Acta Biol. Hung. 49: 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglyak, S., R. T. Durrett, M. D. Schug and C. F. Aquadro, 1998. Equilibrium distributions of microsatellite repeat length resulting from a balance between slippage events and point mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 10774–10778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulikova, O., G. Gualtieri, R. Geurts, D. Kim, D. R. Cook et al., 2001. Integration of the FISH pachytene and genetic maps of Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 27: 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulikova, O., R. Geurts, M. Lamine, D. Kim, D. R. Cook et al., 2004. Satellite repeats in the functional centromere and pericentromeric heterochromatin of Medicago truncatula. Chromosoma 113: 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamblin, A. F., J. A. Crow, J. E. Johnson, K. A. Silverstein, T. M. Kunau et al., 2003. MtDB: a database for personalized data mining of the model legume Medicago truncatula transcriptome. Nucleic Acids Res. 31: 196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens, E., C. Franken, P. Smit, J. Willemse, T. Bisseling et al., 2003. LysM domain receptor kinases regulating rhizobial Nod factor-induced infection. Science 302: 630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpens, E., R. Javier, C. Franken, V. Raz, B. Compaan et al., 2004. RNA interference in Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots of Arabidopsis and Medicago truncatula. J. Exp. Bot. 55: 983–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly, K. H., R. H. Cudmore and J. M. Meer, 2001. Map Manager QTX, cross-platform software for genetic mapping. Mamm. Genome 12: 930–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCouch, S. R., L. Teytelman, Y. Xu, D. B. Lobos, K. Clare et al., 2002. Development and mapping 2,240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza sativa L.). DNA Res. 9: 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgante, M., M. Hanafey and W. Powell, 2002. Microsatellites are preferentially associated with nonrepetitive DNA in plant genomes. Nat. Genet. 30: 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penmetsa, R. V., and D. R. Cook, 2000. Production and characterization of diverse development mutants in Medicago truncatula. Plant Physiol. 123: 1387–1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pupko, T., and D. Graur, 1999. Evolution of microsatellites in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Role of length and number of repeated units. J. Mol. Evol. 48: 313–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C. L., K. A. Dyer, T. Erez, S. J. Miller, J. Jaenike et al., 2003. Rapid divergence of microsatellite abundance among species of Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20: 1143–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen, S., and H. Skaletsky, 2000. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers, pp. 365–386 in Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology, edited by S. Krawetz and S. Misener. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sharopova, N., M. D. McMullen, L. Schultz, S. Schroeder, H. Sanchez-Villeda et al., 2002. Development and mapping of SSR markers for maize. Plant Mol. Biol. 48: 463–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia, E. A., S. Jinks-Robertson and T. D. Petes, 1997. Genetic control of microsatellite stability. Mutat. Res. 383: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledge, M. K., I. M. Ray and G. Jiang, 2005. An expressed sequence tag SSR map of tetraploid alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. Aug 2: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz, D., 1989. Hypervariability of simple sequences as a general source for polymorphic DNA markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 17: 6463–6471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temnykh, S., G. DeClerck, A. Lukashova, L. Lipovich, S. Cartinhour et al., 2001. Computational and experimental analysis of microsatellites in rice (Oryza sativa L.): frequency, length variation, transposon associations, and genetic marker potential. Genome Res. 11: 1441–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel, T., W. Michalek, R. K. Varshney and A. Graner, 2003. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 106: 411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, G., Z. Gáspári and J. Jurka, 2000. Microsatellites in different eukaryotic genomes: survey and analysis. Genome Res. 10: 967–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, T. H., P. Ratet, E. Kondorosi, P. Durand, K. Kamaté et al., 1998. Rapid and efficient transformation of diploid Medicago truncatula and Medicago sativa ssp. falcata lines improved in somatic embryogenesis. Plant Cell Rep. 17: 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta, E., N. E. Grosso, M. Erba and M. Paci, 2000. The ATT strand of AAT·ATT trinucleotide repeats adopts stable hairpin structures induced by minor groove binding lignads. Biochemistry 39: 6799–6808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VandenBosch, K. A., and G. Stacey, 2003. Summaries of legume genomics projects from around the globe. Community resources for crops and models. Plant Physiol. 131: 840–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, J. L., M. R. Knox, T. H. N. Ellis, P. Kaló, G. B. Kiss et al., 2000. Nodule-expressed Cyp15a cysteine protease genes map to syntenic genome regions in Pisum and Medicago spp. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13: 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, B. S., V. S. Asirvatham, L. Wang and L. W. Sumner, 2003. Mapping the proteome of barrel medic (Medicago truncatula). Plant Physiol. 131: 1104–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierdl, M., M. Dominska and T.D. Petes, 1997. Microsatellite instability in yeast: dependence on the length of the microsatellite. Genetics 146: 769–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, N. D., S. B. Cannon, S. Sato, D. Kim, D. R. Cook et al., 2005. Sequencing the genespaces of Medicago truncatula and Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol. 137: 1174–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z., M. B. Chandrasekharan and T. C. Hall, 2004. High rooting frequency and functional analysis of GUS and GFP expression in transgenic Medicago truncatula A17. New Phytol. 162: 813–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]