Abstract

Presenilin is the enzymatic component of γ-secretase, a multisubunit intramembrane protease that processes several transmembrane receptors, such as the amyloid precursor protein (APP). Mutations in human Presenilins lead to altered APP cleavage and early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Presenilins also play an essential role in Notch receptor cleavage and signaling. The Notch pathway is a highly conserved signaling pathway that functions during the development of multicellular organisms, including vertebrates, Drosophila, and C. elegans. Recent studies have shown that Notch signaling is sensitive to perturbations in subcellular trafficking, although the specific mechanisms are largely unknown. To identify genes that regulate Notch pathway function, we have performed two genetic screens in Drosophila for modifiers of Presenilin-dependent Notch phenotypes. We describe here the cloning and identification of 19 modifiers, including nicastrin and several genes with previously undescribed involvement in Notch biology. The predicted functions of these newly identified genes are consistent with extracellular matrix and vesicular trafficking mechanisms in Presenilin and Notch pathway regulation and suggest a novel role for γ-tubulin in the pathway.

THE Presenilin genes encode eight-pass transmembrane proteins found in most metazoans, including mammals, Drosophila, and Caenorhabditis elegans (reviewed in Selkoe 2000; Wolfe and Kopan 2004). In humans, mutations in the two Presenilin genes, PS1 and PS2, account for the majority of familial early-onset Alzheimer's disease (reviewed in Tanzi and Bertram 2001). Presenilin is the catalytic component of the γ-secretase complex that is responsible for the cleavage of the transmembrane protein, amyloid precursor protein (APP) (reviewed in De Strooper 2003). APP cleavage, first by β-secretase and subsequently by γ-secretase, results primarily in the release of the 40-amino-acid amyloid β-peptide (Aβ40). Alzheimer's disease-associated mutations in PS1 or PS2 subtly alter this cleavage pattern, causing increased production of a longer, more cytotoxic form of the amyloid β-peptide (Aβ42). Aβ-peptides are the major component of amyloid plaques in the brains of Alzheimer's disease patients. Higher Aβ42 levels are thought to accelerate the aggregation of Aβ into toxic oligomers and the deposition of extracellular plaque material (reviewed in Wolfe and Haass 2001; Selkoe 2004).

The γ-secretase complex is composed of at least three proteins in addition to Presenilin: nicastrin, aph-1, and pen-2 (Yu et al. 2000; Francis et al. 2002; Goutte et al. 2002). These four transmembrane proteins constitute the γ-secretase core complex, yet little is known about its regulation and activity. γ-Secretase recognizes and cleaves a growing list of transmembrane proteins with very short extracellular domains generated by prior processing (Struhl and Adachi 2000; reviewed in De Strooper 2003; Wolfe and Kopan 2004). A functional role for γ-secretase cleavage has not been demonstrated for most substrates. In such cases, γ-secretase may serve simply to eliminate transmembrane stubs of proteins after extracellular domain shedding (Struhl and Adachi 2000). However, in the case of the Notch family of receptors, γ-secretase plays an essential role in signaling. Genetic studies in C. elegans initially established that Presenilin is required for Notch pathway signaling (Levitan and Greenwald 1995; Li and Greenwald 1997), and this has now been confirmed in Drosophila, mouse, and human systems (reviewed in Wolfe and Kopan 2004). Following ligand binding and subsequent cleavage of Notch by ADAM/TACE proteins, γ-secretase cleavage of Notch results in the release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD). NICD translocates to the nucleus where it activates transcription of target genes in conjunction with the Suppressor of Hairless [Su(H)] and mastermind proteins (reviewed in Baron 2003; Kadesch 2004; Weng and Aster 2004). Notch signaling is involved in a wide variety of cell signaling events in development and in the regeneration and homeostasis of adult tissues. Defects in Notch signaling have been linked to a number of human developmental syndromes and cancers, including Alagille syndrome, CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy), and T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (reviewed in Gridley 2003; Weng and Aster 2004).

In Drosophila, Notch signaling is required during most stages of development and functions in many cell fate specification events in the wing, bristle, and eye (reviewed in Muskavitch 1994; Artavanis-Tsakonas et al. 1999; Portin 2002). Presenilin (Psn) and nicastrin (nct) loss-of-function mutations in Drosophila have been shown to cause similar developmental defects (Guo et al. 1999; Struhl and Greenwald 1999; Ye et al. 1999; Hu et al. 2002; Lopez-Schier and St. Johnston 2002).

Genetic screens in Drosophila and C. elegans have identified many proteins in the Notch pathway. These include Delta/Serrate/Lag-2 type ligands, cytoplasmic/nuclear proteins such as Su(H) and mastermind, and Notch-regulated target genes such as the Enhancer of split complex genes (Kimble and Simpson 1997; Greenwald 1998; reviewed in Baron 2003). Recently, proteins involved in modification, trafficking, and degradation of Notch pathway components have begun to be elucidated, including proteases (furin, kuzbanian, TACE), enzymes involved in glycosylation and/or in chaperone function (fringe, O-fut), members of the ubiquitin machinery (neuralized, mindbomb, deltex, fat facets), and clathrin-coated pit components (dynamin, clathrin, epsin, α-adaptin) (reviewed in Haltiwanger and Stanley 2002; Baron 2003; Schweisguth 2004; Le Borgne et al. 2005; see also Cadavid et al. 2000; Okajima et al. 2005). Notch signaling appears to be particularly sensitive to alterations in subcellular trafficking. Genes involved in vesicular trafficking have been implicated in the activation of Delta, in Notch dissociation and trans-endocytosis, and in Notch degradation (reviewed in Le Borgne et al. 2005). The molecular mechanisms that underlie the requirements for these genes in Notch signaling remain largely unknown.

We have performed two screens in Drosophila to identify genes that interact with Presenilin and the Notch signaling pathway. By screening for modifiers of Psn hypomorphic alleles, we hoped to isolate genes that might directly regulate Presenilin activity. The first screen employed a small deletion within Psn (Psn143) to identify genes that result in dominant Notch pathway mutant phenotypes in the presence of the Psn143 heterozygote. In this screen we recovered a Psn hypomorphic allele, Psn9, as well as several other second-site modifiers. The second screen utilized the viable Psn hypomorphic genotype, Psn9/Psn143, to screen for second-site enhancers and suppressors of the Psn9/Psn143 small, rough eye. We recovered a total of 23 complementation groups and successfully identified 19 genes. These genes include nct, other known Notch interactors, and several genes with previously undescribed involvement in Notch or Presenilin biology, including genes with roles in the extracellular matrix (ECM), Notch transcriptional activity, and vesicular trafficking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila handling and isolation of the Psn143 allele:

All fly stocks and crosses were handled using standard procedures at 25°, unless otherwise noted. Psn143 was generated from a lethal screen performed against deficiency Df(3L)rdgC-co2 [77A1;77D1; Bloomington Stock Center (BSC) stock 2052], which uncovers the region containing Psn (77C3) (data not shown). The Psn143 allele contains a 268-bp deletion that removes amino acids 136–224. There are no associated phenotypes in Psn143 heterozygotes; homozygotes exhibit pupal lethality, which can be rescued by a wild-type Psn transgene (data not shown).

Screen A:

Isogenic w1118 males were mutagenized by overnight feeding of 25 mm EMS in a 10% sucrose solution after a 2-hr starvation period. Mutagenized males were mated to w1118; Psn143 FRT(w+)(2G)/TM6B Hu Tb virgin females (Figure 1A). F1 Psn143/+ progeny were scored for dominant Notch pathway phenotypes. This screen generated a Psn hypomorph allele, Psn9. The Psn9 chromosome carries an extraneous lethal mutation uncovered by deficiency Df(3R)Antp17 (84A6–D14; BSC stock 1842).

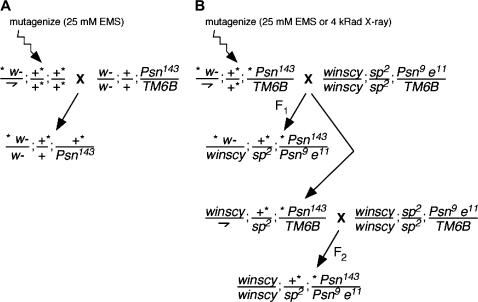

Figure 1.

(A) Screen A. F1 progeny were screened for Notch pathway phenotypes in the presence of +/Psn143. (B) Screen B. F1 or F2 progeny were screened for enhanced small eye or other Notch pathway phenotypes in the presence of Psn9/Psn143.

Screen B:

F1 screen (Figure 1B):

w1118; Psn143/TM6B males were mutagenized with EMS as above or by exposure to X-ray irradiation (4000 rad) using the Faxitron X-ray cabinet system. Mutagenized males were mated with winscy (yc4 sc8 scS1 w1); sp2; Psn9 e11/TM6B virgin females. Reverse crosses were also conducted [mutagenized w1118; Psn9/TM6B males were crossed to winscy; sp2; Psn143 FRT (w+) e11/TM6B virgin females]. Psn9/Psn143 F1 progeny were scored for modification of the Psn9/Psn143 small, rough eye and for other Psn-dependent Notch pathway phenotypes.

F2 screen (Figure 1B):

Balanced F1 male siblings (winscy; +/sp2; Psn143 or Psn9 /TM6B) carrying mutagenized chromosomes were collected and mated as above to the reciprocal Psn allele. A small number of F1 female siblings were also collected and mated to recover modifiers on the X chromosome. F2 progeny were scored for Psn modifier phenotypes. These crosses enjoyed a much higher rate of fertility than did the F1 crosses and resulted in the retention of increased numbers of modifiers, including lethal interactors in the Psn9/Psn143 background.

Complementation analysis and mapping procedures:

Mutations on chromosomes 2 and 3 that were homozygous lethal or homozygous viable with a visible phenotype were analyzed in standard complementation matrices. Complementation for modifiers on the third chromosome (which also carries a copy of either Psn9 or Psn143) could be assessed only as Psn trans-heterozygotes, because both Psn9 and Psn143 chromosomes are homozygous lethal.

Two representatives from each complementation group were mapped via recombination with P-element-containing chromosomes to identify a candidate region of 8–10 Mb. This was followed by sequence analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to narrow the region to 1–2 Mb (Hoskins et al. 2001). High-resolution mapping using SNP analysis on recombinants generated between two flanking P elements (each marked with a miniwhite gene) usually narrowed the candidate region to 25–200 kb (Hoskins et al. 2001). Recombinant chromosomes were scored for lethality with other complementation group members and for the original modification phenotype in the Psn9/Psn143 or +/Psn143 background. The length of the SNP-defined intervals containing each modifier gene is indicated in Table 2. We sequenced most or all genes within these regions. For complementation groups, gene identification was considered valid if mutations were identified in at least two members and were not present in the parental strain. For the two genes represented by single alleles, identification was considered valid if mutations were not present in the parental strain and were confirmed by noncomplementation with known alleles. Additional evidence for candidate regions came from deficiency mapping and, whenever possible, candidate genes were confirmed by lack of complementation with known alleles.

TABLE 2.

Mapped and identified modifiers

| Gene | Cytological site | Accession no. | Allelea | Mutationsb | Phenotypes in Psn mutant backgroundcd | Gene identification methods (maximal interval defined by SNPs, phenotype mapped)e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dac | 36A1 | NM_165161 | MEE-2* | 367–794 DEL and FS | Enhanced eye | Meiotic (40 kb, enhanced eye) and noncomplementation with dac[3] and dac[4] |

| MHE-1 | Y259N | Enhanced eye | ||||

| SFE-8* | C272Y; 887–1074 DEL and FS | Enhanced eye | ||||

| dp | 24F4–25A1 | NM_175960.2 | MFE-1* | Not determined | Notal pits | Meiotic (7 Mb, notal pits) and noncomplementation with CyO dp[lvI], Df(2L)dp-h25, dp[olvR], Tp(2;3)dp[h27], and dp[olvDG10] |

| PGE-8 | Not determined | Enhanced eye | ||||

| PHE-5 | Not determined | Lethal | ||||

| PIE-10* | Not determined | Notal pits | ||||

| eya | 26E1–E2 | NM_078768 | SJE-1 | Translocation | Enhanced eye | Cytology, in situ |

| SLE-2 | Not determined | Enhanced eye | ||||

| γ-Tub23C | 23C3–C4 | NM_057456 | bmps1d* | M382I | Enhanced eye, wing bumps and notching | Meiotic (26.1 kb, enhanced eye) |

| bmps2* | M382I | Enhanced eye, wing bumps and notching | ||||

| bmps3 | P358L | Enhanced eye, wing bumps and notching, vein thickening | ||||

| bmps4 | P358L | Enhanced eye, wing bumps and notching, vein thickening | ||||

| bmps5 | P358L | Enhanced eye, wing bumps and notching, vein thickening | ||||

| so | 43C1 | NM_057385 | SHE-7* | R274Q | Enhanced eye | Meiotic (48 kb, enhanced eye) |

| SKE-1d* | 281–416 DEL | Enhanced eye | ||||

| Spt5 | 56D5–D7 | NM_144353 | MGE-3* | K236* | Enhanced eye | Meiotic (36.2 kb, enhanced eye) |

| SIE-27* | Q632* | Enhanced eye | ||||

| S | 21E2–E3 | NM_078726 | 16 alleles | Not determined | Enhanced eye | Noncomplementation with S[BTE] |

| vg | 49E1 | NM_078999 | PHE-4 | Not determined | Wing notching | Noncomplementation with Df(2R)vg133 and vg[1] |

| SDE-1 | Splice @435 | Enhanced eye, wing notching | ||||

| SGE-4 | Q349* | Wing notching | ||||

| SGE-11 | Not determined | Enhanced eye, wing notching | ||||

| AP-47 | 85D24 | NM_141649 | SAE-10* | S366N | Enhanced eye, vein thickening | Meiotic (85 kb, enhanced eye) |

| SHE-11* | 146–158 DEL and FS | Enhanced eye, vein thickening, low penetrance pupal lethal | ||||

| Dl | 92A1–2 | NM_057916 | MIE-19 | W252* | Lethal | Meiotic (86 kb, enhanced eye) and noncomplementation with known alleles |

| MIE-22* | C433S; C506W | Enhanced eye, vein thickening | ||||

| PFE-5 | C488Y | Lethal | ||||

| PFE-6 | 1–20 DEL | Enhanced eye, vein thickening | ||||

| PGE-2 | 1st exon deleted | Enhanced eye, vein thickening | ||||

| SDE-4* | C538R | Enhanced eye, vein thickening | ||||

| SHE-5 | C362Y | Wings held out, wing notching | ||||

| SHE-11 | Splice @124 | Enhanced eye, vein thickening, low penetrant pupal lethal | ||||

| SIE-36 | Translocation | Vein thickening, low penetrant pupal lethal | ||||

| gl | 91A3 | NM_057506 | SAE-9d | R466* | Enhanced eye | Noncomplementation with gl[2], gl[3] |

| H | 92F3 | NM_079694 | PFE-1 | Not determined | Bristle shaft to socket transformations, vein loss | Noncomplementation with known alleles |

| PGE-1 | Not determined | Bristle shaft to socket transformations, vein loss | ||||

| PGE-4 | Not determined | Bristle shaft to socket transformations, vein loss | ||||

| PGE-6 | Not determined | Bristle shaft to socket transformations, vein loss | ||||

| SDS-1 | Not determined | Suppressed eye, bristle shaft to socket transformations, vein loss | ||||

| SLS-1 | Not determined | Suppressed eye, bristle shaft to socket transformations, vein loss | ||||

| hh | 94E1 | NM_079735.3 | PIE-7* | G257D | Enhanced eye, extra vein material between veins 2 and 3 | Meiotic (161 kb, enhanced eye) and noncomplementation with known alleles |

| SCE-2 | Translocation | Enhanced eye, wing notching | ||||

| SFE-4 | 284–462 DEL and FS | Enhanced eye | ||||

| SGE-2 | N141I | Enhanced eye | ||||

| SHE-2* | S286N | Enhanced eye | ||||

| SLE-1* | Uncharacterized deletion | Enhanced eye | ||||

| kkv | 83A1 | NM_079509 | A1 | G824D | Enhanced eye | Cytology, in situ on a transposition that fails to complement this groupf |

| BM1 | P764N | Enhanced eye | ||||

| SIE-29 | I1043N | Enhanced eye | ||||

| Nsf2 | 87F15 | NM_176499 | A6d* | A597V | Enhanced eye | Meiotic (24 kb, enhanced eye) |

| A15* | 555–641 DEL and FS | Enhanced eye | ||||

| nct | 96B1 | NM_143040 | PIE-6 | Point mutation in 3′ UTR | Enhanced eye | Meiotic (1.46 Mb, enhanced eye) |

| SGE-3 | K476* | Enhanced eye | ||||

| SGE-8 | Q177* | Enhanced eye, wing vein thickening and notching | ||||

| SGE-9 | R273C | Enhanced eye, wing vein thickening and notching | ||||

| SGE-10* | Uncharacterized deletion | Enhanced eye | ||||

| SIE-28* | Not determined | Enhanced eye, wing vein thickening and notching | ||||

| SIE-22 | C272Y | Enhanced eye, wing notching, missing microchaetae | ||||

| Opa | 82E1 | NM_079504 | A3 | Uncharacterized deletion | Enhanced eye, tufted vibrissae | Cytology, in situ |

| B28 | Y275N | Enhanced eye, tufted vibrissae | ||||

| SIE-19 | Y242D | Enhanced eye, tufted vibrissae | ||||

| SIE-24 | Q104* | Enhanced eye, tufted vibrissae | ||||

| SJE-2 | Translocation | Enhanced eye, tufted vibrissae, wing notching | ||||

| SKE-5 | Uncharacterized deletion | Enhanced eye, tufted vibrissae | ||||

| Psn | 77C3 | NM_079460 | 9 | L499Q | Enhanced eye | Sequencing lethal and viable noncomplementers |

| DIE-2g | Q244* | Lethal | ||||

| MIE-5g | Not determined | Lethal | ||||

| MIE-12g | Q523* | Lethal | ||||

| MIE-15g | Not determined | Lethal | ||||

| PIE-11g | G446S | Lethal | ||||

| SIE-5g | D110L | Lethal | ||||

| R | 62B7 | NM_057509 | PIE-6d | L120F | Enhanced eye | Noncomplementation with R[1] |

| Ras85D | 85D21 | NM_057351 | MAE-2* | M67I | Enhanced eye | Meiotic (106 kb, enhanced eye) and noncomplementation with Ras85[D06677] and Ras85[D05703] |

| MDE-7* | G60S | Enhanced eye |

Meiotically mapped alleles are indicated by an *.

The mutation for each allele is indicated. Amino acid numbers are derived from the reference sequence listed in the accession number column. “Splice @” is defined as a nucleotide change in the donor/acceptor “GU/AG” sequence at the referenced amino acid position. “DEL” refers to a deletion of the referenced amino acids and “FS” refers to a predicted frameshift.

Psn background: screen A, Psn143/+ (alleles: 9, bmps1, bmps2, A1, BM1. A6, A15, A3, B28); screen B, Psn9/Psn143 (all other alleles).

Phenotypes in a Psn wild-type background were not assessed, with the following exceptions: NSF2A6 (see results), γ-Tub23C (see results), glSAE-9 (homozygous viable and displays a very small eye), soSKE-1 (homozygous viable and displays a very small eye and loss of ocelli), and RPIE-6 (homozygous viable and displays slightly reduced and severely rough eyes).

Method(s) of gene identification are indicated for each group. Final meiotic mapping interval and the phenotype mapped are indicated in parentheses. The alleles meiotically mapped for each group are indicated by an * in the “Allele” column.

Three additional alleles of kkv were found by testing kkvA1 and kkvBM1 for noncomplementation with a set of lethal mutations within the 82F region recovered by Carpenter (1999). One of these alleles consisted of an X-ray-induced transposition [T(2;3)82Fh2], which was used to cytologically locate the gene by in situ hybridization analysis on polytene chromosomes.

These alleles also carry the Psn9 L499Q mutation in cis to the reported mutation.

Some X-ray-induced modifiers were identified cytologically by utilizing in situ hybridization on polytene chromosomes to molecularly define rearrangements and generate narrow regions of interest (Pardue 1986). dp alleles were meiotically mapped and identified by their notal pit phenotypes and via lack of complementation with known alleles. H and S were identified by their dominant phenotypes and by lack of complementation with known alleles (see Table 2 for details).

Scanning electron microscopy:

Adult flies stored in 70% ethanol were dehydrated through an ethanol series, dried using hexamethyldisilazane (Braet et al. 1997), mounted on stubs, and sputter coated with a 20-nm coat of gold/palladium in an E5400 Sputter Coater. Prepared tissue was viewed and photographed on either an Electroscan E3 ESEM or an ISI DS-130.

Immunohistochemistry:

mAb22C10, which recognizes futsch, a cytoplasmic protein primarily expressed in neuronal cells, was the kind gift of Seymour Benzer (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA). For antibody staining of pupal wings, pupae were removed from their cases at ∼30 hr after puparium formation and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Pupal wings were then removed from the cuticle and fixed for an additional 30 min before washing and staining with mAb22C10 diluted 1:100 (as in Parks et al. 1995 without silver enhancement).

RESULTS

Psn modifier screens identify 19 genes:

We conducted two screens to identify enhancers and suppressors of Presenilin-dependent Notch-like phenotypes. Flies heterozygous for the null allele Psn143 display no visible phenotypes. In screen A (Figure 1A), we screened for mutations causing dominant Notch mutant phenotypes in the +/Psn143 background. These phenotypes include eye reduction and roughness, wing margin loss, ectopic wing veins and vein thickening, and gain or loss of sensory bristles. Twenty-four modifiers of Psn143 were recovered from 18,332 F1 progeny screened (Table 1). We sequenced the Psn genomic region from viable third chromosome mutants and identified a missense mutation, L499Q, in one allele, which we named Psn9. Psn9/Psn143 flies have a reduced and roughened eye (Figure 2D) and distal wing vein thickening (Figures 3E and 4C), consistent with reduced Presenilin function and Notch signaling in eye and wing development. The Psn9 mutation resides in the eighth transmembrane domain of Presenilin, which forms part of the C-terminal PAL domain that is critical for γ-secretase activity. This domain is highly conserved in the Presenilins and in homologous transmembrane proteases (reviewed in Brunkan and Goate 2005). Missense mutations in the residues directly flanking L425 (equivalent to Drosophila L499) have been observed in human PS1 in familial Alzheimer's disease patients. In subsequent experiments, the eye phenotype associated with Psn9 was mapped via meiotic recombination to the interval 73A–83A that contains the Psn gene. Together, these observations implicate the Psn9 allele as a hypomorphic allele responsible for the reduced eye phenotype observed in Psn9/Psn143. Additional modifiers from screen A that did not carry Psn mutations were characterized along with the modifiers from screen B (see below).

TABLE 1.

Summary of screen hits

| Screen | No. screeneda | No. primary hitsb | No. final hitsc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screen A | 18,332 | 295 | 24 |

| Screen B (F1) | 67,079 | 1,266 | 73 |

| Screen B (F2) | 8,821 | 366 | 171 |

| Totals | 94,232 | 1,927 | 268 |

Number of critical class (screen A, Psn143/+; screen B, Psn9/Psn143) flies screened.

Number of initial modifiers recovered during primary screening.

Number of viable, fertile modifiers that retested.

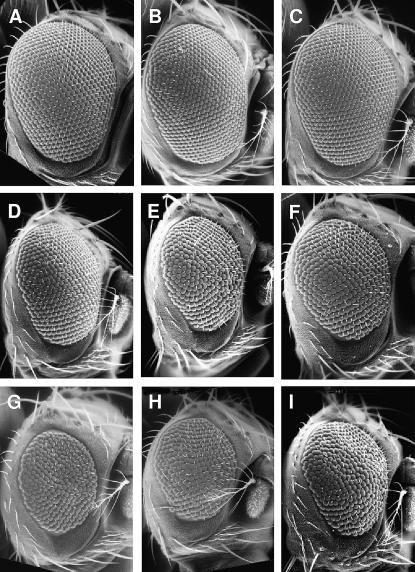

Figure 2.

Enhancers of Psn9/Psn143 have smaller and/or rougher eyes. Scanning electron micrographs of adult eyes from control, Psn9/Psn143, and a selection of modifiers are shown. (A) Wild type. (B) Psn143/+. (C) Psn9/+. (D) Psn9/Psn143. (E) Psn143 nctSGE-9/Psn9. (F) Psn143 AP-47SHE-11/Psn9. (G) γ-Tubbmps4/+; Psn9/Psn143. (H) Spt5SIE-27/+; Psn9/Psn143. (I) opaSIE-19/+; Psn9/Psn143.

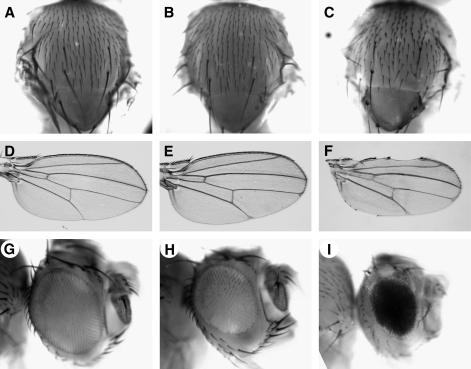

Figure 3.

Reductions in AP-47 function enhance Psn loss-of-function phenotypes in multiple tissues. (A, D, and G) Wild type. (B, E, and H) Psn9/Psn143. (C, F, and I) Psn9 AP-47SAE-10/Psn143 AP-47SHE-11. In addition to a smaller, slightly rougher eye (H), Psn9/Psn143 flies display slight wing vein thickening (E); the notum is relatively normal (B). In contrast, Psn9 AP-47SAE-10/Psn143 AP-47SHE-11 flies have much smaller and rougher eyes (I) (the w+ eye is derived from a recombinant chromosome carrying a w+ P element generated during mapping). They also display dorsal and ventral wing notching (F), enhanced wing vein thickening (F), and notal bristle (microchaetae) loss (C).

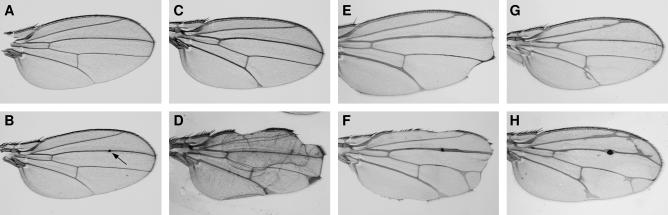

Figure 4.

Wing phenotypes caused by loss of Presenilin, Notch, or Delta function are enhanced by mutations in γ-Tub23C. (A) Wild type. (B) γ-Tub23Cbmps4/+ wings display small- to moderate-sized bumps (arrow points to small bump), usually along wing veins, and occasional nicking (not shown). (C) Psn9/Psn143 wings show slight vein thickening at the wing margin. (D) γ-Tub23Cbmps4/+; Psn9/Psn143 wings display notching and enhanced vein thickening compared to C. (E) N81k1/+ wings have distal notching and wing vein thickening. (F) N81k1/+; γ-Tub23Cbmps4/+ wings have enhanced notching (dorsal, ventral, and distal) compared to E and both thickened and ectopic veins. (G) DleA7/+ wings show some vein thickening as well as small amounts of ectopic vein. (H) γ-Tub23Cbmps4/+; DleA7/+ wings develop more ectopic vein and have mildly enhanced wing vein thickening compared to G.

In the F1 generation of screen B (Figure 1B), we screened for enhancement or suppression of the small, rough eye phenotype present in Psn9/Psn143 as well as for the presence of any other Notch-like phenotypes. In addition, an F2 screen was performed by crossing F1 generation Psn−/TM6B males heterozygous for mutagenized chromosomes (Figure 1B) to females carrying the reciprocal Psn allele. Their progeny were scored for Notch-like phenotypes as well as lethality. We recovered 244 modifiers from 75,900 total trans-heterozygous progeny from the F1 and F2 portions of screen B (Table 1).

From these modifiers, we identified 21 lethal complementation groups and two complementation groups displaying phenotypic interactions. In total, 19 modifier genes were successfully mapped and identified, including 17 defined by complementation groups and two genes represented by single alleles (Table 2). Additionally we recovered secondary mutations in the Psn gene in cis to the Psn9 mutation. These mutations, like Psn deficiencies, are lethal in trans to Psn143, suggesting that they are severe hypomorphic or null alleles.

Nicastrin, a γ-secretase core complex member:

We recovered seven alleles of the γ-secretase core complex gene, nct, from screen B. These nct alleles enhance the Psn9/Psn143 reduced eye (Figure 2E) and wing vein thickening and also exhibit wing notching (data not shown). They show no phenotype as heterozygotes in cis with either Psn allele alone. Two alleles, nctSGE-9 and nctSIE-22, have missense mutations that result in substitutions in two adjacent amino acids (Table 2). This region is located two amino acids upstream of an aspartate conserved in the bacterial zinc aminopeptidase and glutaminyl cyclase G-protein families. These two amino acids may be critical for nicastrin function as part of a putative catalytic or structural domain involved in either assembly of the active Presenilin complex or interactions with γ-secretase substrates such as Notch, Delta, or APP.

Although this screen isolated nct alleles, we note that the background is not sensitive enough to recover all γ-secretase complex members. Heterozygosity for a recessive lethal aph-1 allele, aph-1D35, does not modify Psn9/Psn143. However, aph-1D35 did show interactions with nctSGE-9 Psn9/Psn143, including slightly smaller, rougher eyes and severe loss of abdominal bristles (data not shown). Future screens using modifiers of this genotype or a clonal screen to recover recessive modifier mutations may yield additional regulators of Presenilin and the Notch pathway.

Modifiers with established roles in Notch signaling:

In addition to nct, we identified a number of genes with well-characterized roles in Notch signaling. Nine alleles of Delta (Dl), one of the two Drosophila Notch ligands, were isolated either as enhancers of the Psn9/Psn143 eye or wing phenotype or as lethal interactors. All display dominant vein thickening at the wing margin, a common Dl mutant phenotype, in a Psn9/+ or a Psn143/+ background. Interestingly, mutations in a number of alleles affect cysteine residues in epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like repeats (ELRs) 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9. Previous results indicate that mutations in many of the Dl ELRs are correlated with loss-of-function phenotypes and abnormal subcellular Delta distribution (Parks et al. 2000; J. R. Stout, A. Dos Santos and M. A. T. Muskavitch, personal communication).

Six alleles of Hairless (H) were identified. H encodes a negative regulator of Notch signaling (Bang et al. 1995; Lyman and Yedvobnick 1995; Schweisguth and Lecourtois 1998) and, consistent with this, two of our alleles suppressed the Psn9/Psn143 reduced eye (Table 2). All display dominant phenotypes associated with reduced Hairless activity (e.g., transformation of the bristle shaft to a socket cell and shortening of the fourth wing vein) in a Psn9/+ or a Psn143/+ background.

Alleles of vestigial (vg) were recovered as wing modifiers, exhibiting wing notching in the Psn9/Psn143 background; vgPHE-4 also exhibits mild wing nicking in the presence of Psn143 alone. All trans-heterozygous combinations of these alleles result in severe reduction or loss of wings. Two alleles, vgSGE-11 and vgSDE-1, also display a slightly smaller eye with Psn9/Psn143. Notch signaling, in addition to wingless signaling, is required for vg expression (Couso et al. 1995; Kim et al. 1996; Neumann and Cohen 1996). The genetic interactions in our screen suggest that vg is an important Notch pathway downstream effector in the eye as well as in the wing.

Modifiers involved in eye development:

We recovered alleles of eight genes with known roles in eye development: dachshund (dac), sine oculis (so), eyes absent (eya), Star (S), Ras85D, Roughened (R), glass (gl), and hedgehog (hh). All alleles, with the exception of hhPIE-7 (see Table 2), exhibited a small rough eye in the presence of Psn143 or were enhancers of the Psn9/Psn143 reduced eye phenotype. Eyes absent, sine oculis, and dachshund function downstream of eyeless during early eye development and positively regulate specification of the eye (reviewed in Silver and Rebay 2005). The small GTPase Ras85D functions downstream of multiple receptors during eye development, including the EGF receptor and Sevenless, and plays roles during many different stages of eye development (Simon et al. 1991; Halfar et al. 2001; Kumar and Moses 2001b; Yang and Baker 2001, 2003; Strutt and Strutt 2003). Star is required during eye development (Heberlein and Rubin 1991; Heberlein et al. 1993) for the correct trafficking of the EGF receptor ligand, spitz, to the cell surface (Bang and Kintner 2000; Lee et al. 2001; Tsruya et al. 2002). The Notch and EGF receptor signaling pathways have been shown to act together and/or in opposition during the specification of most retinal cell fates (Flores et al. 2000; Kumar and Moses 2001a,b; Tsuda et al. 2002; reviewed in Voas and Rebay 2004). However, we note that Star may also be required directly by the Notch pathway for proper transport of Notch, its ligands, or components of the Presenilin complex, in a manner analogous to that of spitz. R encodes a Ras-related Rap GTPase that has been implicated in the regulation of the development of cell morphology during eye imaginal development (Hariharan et al. 1991; Asha et al. 1999). The transcription factor, glass, is required for photoreceptor development (Moses et al. 1989; Dickson and Hafen 1993; O'Neill et al. 1995), while hedgehog is involved in both specification of the early eye primordium (Royet and Finkelstein 1997) and the progression of the morphogenetic furrow (reviewed in Heberlein and Moses 1995). The eye phenotypes associated with these eight genes in the Psn mutant background are likely due to additive effects on eye development or to reduced Notch induction resulting from alterations in these pathways.

Odd-paired:

Six alleles of odd-paired (opa) were recovered as mild enhancers of the Psn9/Psn143 eye phenotype (Figure 2I) and all display tufted vibrissae (data not shown). Opa is homologous to the Zic family of transcription factors, which function prominently in vertebrate neuronal development (reviewed in Aruga 2004). During embryonic development in Drosophila, opa is required for the correct level and temporal pattern of wingless (wg) and engrailed expression (Benedyk et al. 1994 and references therein) as well as for the expression of the proneural gene, achaete (ac) (Skeath et al. 1992). In vertebrates, Zic1 has been shown to affect the expression levels of several members of the Notch pathway (Aruga et al. 2002). Our data demonstrate a novel function for opa in the development of adult eyes and head bristles. We propose that opa plays a role in determining the positioning and number of vibrissae via regulation of wg, ac, and N. This phenotype and subtle changes in eye size are likely the result of the additive effects of altering Wingless, Achaete, and Notch signaling.

Spt5:

We recovered two alleles of Spt5 as enhancers of the Psn9/Psn143 reduced eye phenotype (Figure 2H). Spt5 is one of a group of transcriptional regulatory factors named after their initial isolation in yeast genetic screens as suppressors of Ty insertions. Spt5 appears to play both positive and negative roles during transcription, possibly by forming a complex with Spt4 and by interacting with both a positive transcription elongation factor (P-TEFb) and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) (Hartzog et al. 1998; Wada et al. 1998a,b).

In yeast, Spt5 forms a physical complex with another elongation factor, Spt6, and in humans, Spt6 can stimulate transcription in conjunction with the Spt5/Spt4 complex (Lindstrom et al. 2003; Endoh et al. 2004). In Drosophila, Spt5 and Spt6 may play both positive and negative roles in transcription elongation. They colocalize to actively transcribed regions of the chromosome and are recruited to the heat-shock genes following heat shock. Spt5 mutant embryos display reduced levels of heat-shock proteins following heat shock, suggesting that Spt5 plays a positive role in the transcription of these genes (Andrulis et al. 2000, 2002; Kaplan et al. 2000; Jennings et al. 2004). In contrast, even-skipped transcription increases in Spt5 mutant embryos, suggesting that Spt5 acts to negatively regulate expression of this gene (Jennings et al. 2004).

Genetic and biochemical studies suggest that Spt6 may interact with histones H3 and H4 and may help regulate chromatin structure (Bortvin and Winston 1996). Interestingly, the C. elegans homolog of Spt6, EMB-5, has mutant phenotypes and genetic interactions consistent with a role in Notch signaling (Hubbard et al. 1996). It has also been shown by yeast two-hybrid analysis to associate with the intracellular domains of the C. elegans Notch homologs, LIN-12 and GLP-1, and to biochemically contribute to NICD transcriptional activity (Hubbard et al. 1996). Fryer et al. (2004) observed that human SPT6 is present at Notch-regulated promoters and increases upon Notch stimulation, although a physical interaction of NICD and SPT6 was not detected. The genetic interactions of Spt5 and Spt6 with Notch signaling implicate regulated transcriptional elongation by the Pol II transcriptional machinery in the function of the NICD transcription complex

Novel Presenilin-dependent Notch interactions in the ECM:

We recovered four alleles of dumpy (dp) from screen B. dpPHE-5 was recovered as a modifier causing Psn9/Psn143 lethality. dpPGE-8 enhances the Psn9/Psn143 eye phenotype and two alleles, dpMFE-1 and dpPIE-10, exhibit Psn9/Psn143-dependent dp-like pits in the anterior of the notum. dpPIE-10 also displays mild dp-like pits in a Psn9/+ background.

dp encodes a very large protein predicted to contain 308 EGF-like repeats, a zona pellucida (ZP) domain, and a membrane anchor sequence and likely functions as part of the ECM (Wilkin et al. 2000). Dumpy appears to play roles in the organization of the cuticle, tracheal development, attachment of epithelial cells to overlying cuticle, and in cell growth and differentiation (Wilkin et al. 2000 and references therein; Denholm and Skaer 2003; Jazwinska et al. 2003). Recent studies have also suggested that ZP-containing proteins, including dumpy, may be involved in cell adhesion to the apical extracellular matrix (Bokel et al. 2005). Dumpy may be involved in mediating cell–cell interactions in the ECM between Notch and its ligands or possibly in localizing the Presenilin complex to specific regions of the membrane. Alternatively, loss of dumpy activity may cause cell adhesion abnormalities that, in addition to reductions in Notch signaling, result in the observed modifications.

A total of three alleles of krotzkopf verkehrt (kkv) were isolated from the two screens. Two alleles cause smaller eyes in the presence of Psn143 and one enhances the Psn9/Psn143 eye phenotype. kkv encodes one of two chitin synthases found in Drosophila. It is a multipass transmembrane protein that converts UDP-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine into UDP and chitin, an insoluble polymer consisting of 1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues. It has two conserved aspartates and a QXXRW sequence motif necessary for substrate binding and catalysis (Saxena et al. 1995). In mammals, these same motifs are conserved in hyaluronan synthase (HAS), and recent studies have demonstrated that insects can produce hyaluronan when the murine HAS2 gene is introduced, suggesting that the chitin and hyaluronan synthetic pathways are highly related (Takeo et al. 2004). All three mutations in the kkv gene lie within conserved stretches of amino acids in this region of HAS homology. We propose that alterations of chitin synthesis adversely affect cell–cell adhesion in the ECM, thereby disrupting the interactions of Notch with its ligands, although alternative models in which altered ECM integrity disrupts general cell–cell interactions independently of Notch cannot be ruled out.

Nsf2 and AP-47 implicate vesicular trafficking in Notch signaling:

We recovered two Psn modifiers with known functions in subcellular protein and vesicular trafficking. The first of these modifiers, NEM-sensitive fusion protein 2 (Nsf2), encodes an AAA ATPase family member, which functions as a chaperone-type protein that utilizes ATP hydrolysis to drive conformational changes in target proteins (reviewed in Whiteheart and Matveeva 2004). We identified two alleles of Nsf2 that cause subtle eye roughness in the Psn143 background, one of which, Nsf2A6, is homozygous viable with small rough eyes.

In Drosophila, phenotypes resulting from expression of dominant-negative forms of Nsf2 suggest that Nsf2 plays roles in Notch and Wingless signaling (Stewart et al. 2001), and our mutant alleles confirm this observation. In humans, NSF likely functions in synaptic vesicle fusion by altering the conformation of SNAP–SNARE complexes. A similar chaperone activity contributes to the regulation of the β-2-adrenergic receptor by altering the conformation of the adrenergic receptor-binding protein, β-arrestin, which affects β-arrestin's interactions with the cytoskeleton or with proteins such as clathrin (McDonald et al. 1999; McDonald and Lefkowitz 2001; Miller et al. 2001). In addition, NSF may be involved in disassembly and recycling of the glutamate receptor complex (Nishimune et al. 1998; Song et al. 1998; Noel et al. 1999). Several models are possible for the role of Nsf2 in Notch signaling. Nsf2 may be required for the endocytosis of Notch receptors and ligands that has been shown to be essential for Notch signaling (see discussion). Alternatively, Nsf2 might be essential for the assembly of mature γ-secretase complexes or for trafficking and recycling of γ-secretase during Notch signaling.

We recovered two alleles of AP-47, the μ-subunit of the AP-1 clathrin adaptor complex, as mild enhancers of the Psn9/Psn143 reduced eye (Figure 2F). AP-47SAE-10 displayed mild vein thickening in the Psn9/Psn143 background. As trans-heterozygotes, Psn9 AP-47SAE-10/Psn143 AP-47SHE-11 are viable and display striking Notch loss-of-function phenotypes in the wing, the notum, and the eye (Figure 3). In the course of genetic mapping, we generated a recombinant AP-47SHE-11 chromosome lacking the Psn143 mutation. Psn9 AP-47SAE-10/AP-47SHE-11 flies are essentially wild type (data not shown), suggesting that the AP-47 Notch-like interaction phenotypes are dependent on reduced Notch signaling. We suggest that AP-47 functions in Notch signaling via its role as a clathrin adaptor complex member (see discussion).

γ-Tubulin:

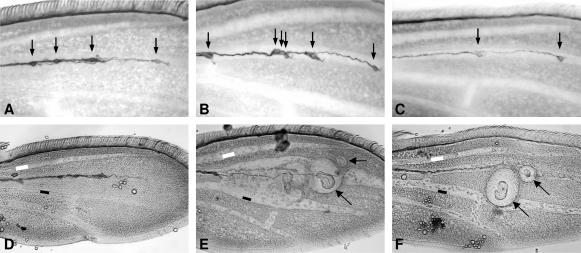

We isolated five alleles of γ-Tubulin23C (γ-Tub23C) that exhibit small, rough eyes, enhanced wing vein thickening, and wing nicking in combination with Psn9/Psn143 (Figures 2G and 4, C and D). γ-Tub23C mutants exhibit two additional phenotypes as pupae that may result from Notch signaling defects. Wild-type pupal wings contain four neuronal cell bodies spaced along the third wing vein (Figure 5A, arrows), three of which are likely associated with the campaniform sensillae. In contrast, γ-Tub23C mutant wings often show a reduced number of neuronal cell bodies, neurons spaced incorrectly, or, less frequently, extra neurons at a single site (Figure 5, B and C). Sensory organ loss and the inappropriate adoption of the neuronal fate by sibling cells resulting in clusters of neurons are typical phenotypes caused by alterations in Notch signaling. In addition, 30 hr after puparium formation (APF), γ-Tub23C mutant pupal wings appear to have grossly thickened veins (compare Figure 5, E and F, with 5D), a typical Notch pathway loss-of-function phenotype. These thickened veins appear to recover during subsequent development, resulting in essentially wild-type veins in the adult. Transient vein thickening associated with loss of Notch signaling has also been observed in conditional dynamin mutants (Parks et al. 2000).

Figure 5.

Mutations in γ-Tub23C result in abnormal numbers of neurons and thickened veins in pupal wings. (A–C) Thirty hours after puparium formation (APF) pupal wings were immunostained with mAb22C10 to identify neurons. (D–F) Pupal wings were treated as in A–C except that photos were taken under high contrast to more easily visualize veins. (A–C) Wild-type pupal wings (A) have four neurons (arrows) spaced along the third wing vein. In contrast, γ-Tub23Cbmps1/+ pupal wings have either too many neurons (arrows in B) or too few neurons (arrows in C). (D–F) In comparison to wild type (D), γ-Tub23Cbmps4/+; Psn9/+ pupal wing veins are abnormally wide (E and F). The open and solid rectangles in D–F indicate the widths of the wild-type veins in D to facilitate comparison. Arrows in E and F indicate bumps (see text).

γ-Tub23C mutants are homozygous lethal. Heterozygotes display several dominant, Presenilin-independent phenotypes in the adult. Approximately 8% of γ-Tub23C adults have nicked wings and γ-Tub23Cbmps1, γ-Tub23Cbmps2, and γ-Tub23Cbmps4 adults display a very mild rough eye phenotype (data not shown) that is not highly penetrant and is not strong enough to account for the enhanced small, rough eye observed in the Psn9/Psn143 background (Figure 2G). Strikingly, a large fraction of γ-Tub23C adults have wings with “bumps” (Figure 4B, arrow). This phenotype appears to be temperature sensitive. At 18°, 10% (n = 19) and at 23°, 6% (n = 31) of γ-Tub23C bmps1/CyO display bumps, whereas, at 27°, ∼92% display bumps (n = 40). Similarly, 0–5% of γ-Tub23C bmps4/CyO adults display bumps at 18° or 23° (n = 149 and 37, respectively), whereas 47% display bumps at 27° (n = 113). The majority (90%) of these bumps occur along the third wing vein (L3) and most of these (91%) occur in the mid-distal portion of the vein (data not shown). Bumps have also been observed on the fourth wing vein, on crossveins, and in intervein regions. The location of the majority of bumps on L3 coincides with the region in which campaniform sensillae are found. However, examination of 30-hr APF wings suggests that there is no correlation between the neurons associated with the campaniform sensillae and the location of these masses. Bumps appear sometime between 0 and 30 hr APF and seem to consist of a mass of extracellular material deposited between the dorsal and ventral epithelial sheets that form the wing (Figure 5, E and F, arrows). There are no cells associated with these masses as judged by the absence of DAPI-positive nuclei (data not shown). In addition, there is no clear correlation between the severity of the bumps phenotype and reductions in Presenilin, Notch, or Delta function (data not shown). These results indicate that this phenotype is not directly related to Notch signaling.

In addition to strong genetic interactions with Psn mutations, γ-Tub23C alleles show significant genetic interactions with N and Dl alleles. γ-Tub23C mutants strongly enhance the wing-notching phenotype associated with N hypomorphs. For example, nicking associated with N81k1 occurs primarily in the distal portion of the wing with little or no anterior nicking (Figure 4E). In contrast, notching in N81k1/+ ; γ-Tub23Cbmps4/+ occurs throughout the entirety of the wing margin and is accompanied by a mild increase in extra vein material, especially at vein termini (Figure 4F). γ-Tub23C mutations also enhance the vein thickening and ectopic vein phenotypes associated with Dl mutations (Figure 4, G and H). No interactions were seen with alleles of Su(H), aph-1, mastermind, deltex, bigbrain, EGFR, or rhomboid (data not shown).

The mutational changes present in our γ-Tub23C alleles suggest that they are not null alleles. The five alleles arose in two separate rounds of mutagenesis in each of the two screens and thus originated from at least four independent mutational events. Nonetheless, γ-Tub23Cbmps1 and γ-Tub23Cbmps2 both share a change from Met382 to Ile, while γ-Tub23Cbmps3, γ-Tub23Cbmps4, and γ-Tub23Cbmps5 share a change from Pro358 to Leu. Met382 is conserved in both humans and yeast γ-tubulin, but is changed to Leu in C. elegans. Pro358 is conserved in humans, yeast, and C. elegans γ-tubulin. Genetic data are consistent with the suggestion that these γ-Tub23C alleles are not null alleles as γ-Tub23Cbmps4 is semiviable in trans with a deficiency that deletes γ-Tub23C [Df(2L)JS17 dppd-ho; BSC stock 1567]. The surviving adults are all male and display small, crumpled, blistered wings; small, rough eyes; missing macrochaetae; and microchaeta polarity defects (data not shown). The recurrence of these two amino acid changes in our alleles suggests that they cause aberrant γ-tubulin function that can reduce Notch pathway signaling.

DISCUSSION

We performed two genetic screens in Drosophila and identified 19 modifiers of Presenilin-dependent Notch phenotypes caused by Psn hypomorphic mutations. We identified genes required for general eye development as well as known members of the Notch pathway. The screen isolated several nct mutations, indicating that the Psn9/Psn143 genotype provides a sensitized background for recovering Notch pathway interactors, including those directly involved in γ-secretase function.

We identified Nsf2, AP-47, and γ-Tubulin23C as regulators of the Notch pathway. Nsf2 has well-defined functions in protein trafficking and has been previously tied to Notch signaling using overexpression of a dominant-negative Nsf2 protein (Stewart et al. 2001). Our screens now confirm Nsf2 involvement in Notch signaling with the recovery of loss-of-function alleles. In contrast, AP-47 and γ-tubulin have not been linked to Notch signaling in the past. AP-47 has well-defined functions in vesicular trafficking and likely functions in Notch signaling in this capacity, while the mechanism of γ-tubulin function in the pathway is less clear.

Recent work has implicated several proteins involved in vesicular trafficking in both positive and negative regulation of the Notch pathway (reviewed in Le Borgne et al. 2005). The best studied of these is dynamin, the GTPase responsible for formation and pinching off of vesicles. Loss of dynamin function results in loss of Delta endocytosis, loss of dissociation of the Notch extracellular and intracellular domains, and strong Notch loss-of-function phenotypes (Poodry 1990; Seugnet et al. 1997; Parks et al. 2000). Dynamin appears to be required in both Delta- and Notch-expressing cells for Notch signaling to occur, but its precise role has yet to be determined (Seugnet et al. 1997; Parks et al. 2000). Other proteins that positively regulate Notch signaling include the clathrin coat components, clathrin heavy chain, α-adaptin, and epsin (Cadavid et al. 2000; Tian et al. 2004; Wang and Struhl 2004, 2005) and the regulator, Nsf2 (see results; Stewart et al. 2001). Finally, three ubiquitin ligases, neuralized, mindbomb, and deltex, act to positively regulate trafficking and signaling of Notch pathway members. Neuralized and mindbomb are thought to ubiquitinate Delta and/or Serrate to promote ligand endocytosis and activation of signal (reviewed in Le Borgne et al. 2005). Deltex likely ubiquitinates Notch to promote sorting into an undefined intracellular compartment where ligand- and Su(H)-independent signaling may occur (Hori et al. 2004 and references therein).

It is apparent that the endocytic machinery can be regulated at numerous steps to positively affect Notch signaling, yet the role that these proteins play remains unclear. Endocytosis of Delta bound to Notch could result in conformational changes in Notch necessary for its cleavage by ADAM/TACE proteins and γ-secretases and subsequent release of the intracellular domain (Parks et al. 2000). Endocytic proteins may also recruit cofactors necessary for Delta–Notch signaling or may contribute to colocalization of Notch receptors and secretases. In addition, endocytosis through a recycling endosome has been proposed as a mechanism for converting a Delta “pro-ligand” into an active form (Wang and Struhl 2004). It is not known if similar mechanisms directly regulate the activity and recycling of γ-secretase complexes.

Mutations in AP-47, the Drosophila μ1 protein of the clathrin adaptor complex AP-1, result in typical Notch loss-of-function phenotypes in the Psn9/Psn143 background. There are at least four distinct adaptor protein (AP) complexes that link clathrin to membranes, coordinate clathrin coat assembly, and recruit cargo proteins. AP-1 functions in multiple steps in vesicle trafficking and cargo sorting from the Golgi to endosomes and the plasma membrane and is critical for the sorting and recycling of receptors to correct plasma membrane domains (Futter et al. 1998; Nakagawa et al. 2000; Orzech et al. 2001; Gan et al. 2002; Pagano et al. 2004). The μ-chain of AP-1 appears to be responsible for sorting cargo proteins into developing vesicles. In kidney epithelial cells, μ1A mediates sorting to endosomes, while μ1B mediates the targeting of proteins to the basolateral plasma membrane (Sugimoto et al. 2002; Folsch et al. 2003 and references therein). In C. elegans, unc-101 encodes a μ-subunit closely related to mammalian AP-47 (Lee et al. 1994). In chemosensory neurons, loss of unc-101 function results in abnormal membrane trafficking of a certain set of proteins (Dwyer et al. 2001). These data suggest that AP-1 μ-chains can recognize and target specific proteins to specific cellular destinations. Preliminary data suggest that unc-101 enhances a Presenilin loss-of-function egg-laying phenotype in C. elegans (R. Francis and G. McGrath, personal communication). This, in combination with our genetic data, implies that AP-47 plays a key regulatory role in Notch pathway function through the sorting, trafficking, and/or recycling of the Notch receptors, ligands, and secretases to their correct cellular destinations. Alternatively, AP-47 could function as part of the recycling endosomal pathway suggested to be required for Delta activation (Wang and Struhl 2004, 2005).

We recovered five alleles of γ-Tub23C. These alleles display loss-of-function Notch-like phenotypes in pupae and adults in the absence of any sensitizing mutations and have strong genetic interactions not only with Psn mutations, but also with Dl and N alleles. These alleles do not appear to behave as nulls (see results), but rather may impair or impart a specific interaction between γ-tubulin and Presenilin, Notch, or other members of the pathway.

There are currently two primary functions attributed to γ-tubulin: nucleation of microtubules as part of the centrosomal complex (Oakley 2000; reviewed in Moritz and Agard 2001) and capping of microtubule “minus” ends (Wiese and Zheng 2000), which may regulate microtubule growth. It has also been hypothesized that the centrosomal complex may serve as a site to concentrate proteins involved in the cell cycle and that some of these proteins may bind to γ-tubulin (Prigozhina et al. 2004). Interestingly, PS1 is functionally associated with the cytoskeleton (Pigino et al. 2001 and references therein), perhaps through interactions with microtubule-binding proteins such as CLIP-170 (Tezapsidis et al. 2003). PS1 and PS2 have also been detected at centrosomes (Li et al. 1997), suggesting the possibility of a functional interaction with γ-tubulin. This notion is supported by the observation that mutations in a C. elegans Presenilin gene, spe-4, display defective spermatogenesis accompanied by aberrant tubulin accumulation (Arduengo et al. 1998). Finally, recent research has indicated that in the two-cell stage in developing Drosophila bristle organs, Delta accumulates in Rab11-positive recycling endosomes in one cell but not in the other (Emery et al. 2005). These endosomes are pericentrosomal and their asymmetric accumulation appears to require asymmetric accumulation of the protein Nuclear Fallout, the Drosophila homolog of Arfophilin/Rab11-FIB3, which is also known to concentrate at centrosomes (Emery et al. 2005).

Centrosomal and/or cytoplasmic γ-tubulin may play a role in regulating cellular architecture via the nucleation of microtubules from the centrosome, capping of minus ends, and mediating microtubule growth in the cytoplasm and/or recruitment and localization of proteins. These functions may regulate vesicle trafficking through the secretory and endocytic pathways, which could influence the subcellular localization of Presenilin or other Notch pathway components. Additional experiments will be required to determine if the γ-tubulin missense mutations described here are gain or loss of function, whether they interact directly with Presenilin or Notch pathway components, or whether they modulate the pathway indirectly through effects on other processes, such as vesicle trafficking.

In conclusion, we have performed two genetic screens and identified 19 modifiers of Presenilin-dependent Notch pathway phenotypes. We recovered a number of proteins not previously implicated in Notch signaling, including Spt5, a transcription elongation factor that may interact with the Notch intracellular domain through Spt6, and two proteins involved in ECM function, kkv and dumpy. In addition, we have discovered a novel role for AP-47 that reinforces current research suggesting that the subcellular trafficking machinery is an important regulator of Notch signaling, and we implicate γ-tubulin as a Notch pathway interactor. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms by which Notch signaling is regulated in development and suggest novel candidate approaches for targeting human disorders, including cancer and Alzheimer's disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Exelixis Genome Biochemistry department, in particular, Chris Park and Lisa Wong, for help with mapping and sequencing. We thank the Exelixis FlyCore and FlyTech groups for help in developing and maintaining the fly stocks used in mapping and characterization of modifiers. We thank Ross Francis, Garth McGrath, Jane Stout, Ana Dos Santos, and Marc Muskavitch for sharing unpublished data. We thank Casey Kopczynski, Geoff Duyk, and the genetics department for helpful discussions. We thank Seymour Benzer for kindly supplying the 22C10 antibody. We also acknowledge project support and helpful discussions with Mark Gurney, Jeffrey Nye, Ismael Kola, Henry Skinner, Jinhe Li, and Jennifer Johnston of Pharmacia Corporation.

References

- Andrulis, E. D., E. Guzman, P. Doring, J. Werner and J. T. Lis, 2000. High-resolution localization of Drosophila Spt5 and Spt6 at heat shock genes in vivo: roles in promoter proximal pausing and transcription elongation. Genes Dev. 14: 2635–2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis, E. D., J. Werner, A. Nazarian, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst et al., 2002. The RNA processing exosome is linked to elongating RNA polymerase II in Drosophila. Nature 420: 837–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arduengo, P. M., O. K. Appleberry, P. Chuang and S. W. L'Hernault, 1998. The Presenilin protein family member SPE-4 localizes to an ER/Golgi derived organelle and is required for proper cytoplasmic partitioning during Caenorhabditis elegans spermatogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 111(24): 3645–3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas, S., M. D. Rand and R. J. Lake, 1999. Notch signalling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science 284: 770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruga, J., 2004. The role of Zic genes in neural development. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 26: 205–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruga, J., T. Tohmonda, S. Homma and K. Mikoshiba, 2002. Zic1 promotes the expansion of dorsal neural progenitors in spinal cord by inhibiting neuronal differentiation. Dev. Biol. 244: 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asha, H., N. D. de Ruiter, M. G. Wang and I. K. Hariharan, 1999. The Rap1 GTPase functions as a regulator of morphogenesis in vivo. EMBO J. 18: 605–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang, A. G., and C. Kintner, 2000. Rhomboid and Star facilitate presentation and processing of the Drosophila TGF-alpha homolog Spitz. Genes Dev. 14: 177–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang, A. G., A. M. Bailey and J. W. Posakony, 1995. Hairless promotes stable commitment to the sensory organ precursor cell fate by negatively regulating the activity of the Notch signalling pathway. Dev. Biol. 172: 479–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron, M., 2003. An overview of the Notch signalling pathway. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 14: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedyk, M. J., J. R. Mullen and S. DiNardo, 1994. Odd-paired: a zinc finger pair-rule protein required for the timely activation of engrailed and wingless in Drosophila embryos. Genes Dev. 8: 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokel, C., A. Prokop and N. H. Brown, 2005. Papillote and Piopio: Drosophila ZP-domain proteins required for cell adhesion to the apical extracellular matrix and microtubule organization. J. Cell Sci. 118: 633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortvin, A., and F. Winston, 1996. Evidence that Spt6p controls chromatin structure by a direct interaction with histones. Science 272: 1473–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braet, F., R. De Zanger and E. Wisse, 1997. Drying cells for SEM, AFM and TEM by hexamethyldisilazane: a study on hepatic endothelial cells. J. Microsc. 186(1): 84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkan, A. L., and A. M. Goate, 2005. Presenilin function and gamma-secretase activity. J. Neurochem. 93: 769–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadavid, A. L., A. Ginzel and J. A. Fischer, 2000. The function of the Drosophila fat facets deubiquitinating enzyme in limiting photoreceptor cell number is intimately associated with endocytosis. Development 127: 1727–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, A. T. C., 1999. Saturation mutagenesis of region 82F. Dros. Inf. Serv. 82: 113–114. [Google Scholar]

- Couso, J. P., E. Knust and A. Martinez-Arias, 1995. Serrate and wingless cooperate to induce vestigial gene expression and wing formation in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 5: 1437–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denholm, B., and H. Skaer, 2003. Tubulogenesis: a role for the apical extracellular matrix? Curr. Biol. 13: R909–R911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper, B., 2003. Aph-1, Pen-2, and Nicastrin with Presenilin generate an active gamma-secretase complex. Neuron 38: 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, B., and E. Hafen, 1993. Genetic dissection of eye development in Drosophila, pp. 1327–1362 in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, edited by M. Bates and A. Martinez Arias. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Dwyer, N. D., C. E. Adler, J. G. Crump, N. D. L'Etoile and C. I. Bargmann, 2001. Polarized dendritic transport and the AP-1 mu1 clathrin adaptor UNC-101 localize odorant receptors to olfactory cilia. Neuron 31: 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endoh, M., W. Zhu, J. Hasegawa, H. Watanabe, D. K. Kim et al., 2004. Human Spt6 stimulates transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 3324–3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery, G., A. Hutterer, D. Berdnik, B. Mayer, F. Wirtz-Peitz et al., 2005. Asymmetric Rab11 endosomes regulate Delta recycling and specify cell fate in the Drosophila nervous system. Cell 122: 763–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores, G. V., H. Duan, H. Yan, R. Nagaraj, W. Fu et al., 2000. Combinatorial signaling in the specification of unique cell fates. Cell 103: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsch, H., M. Pypaert, S. Maday, L. Pelletier and I. Mellman, 2003. The AP-1A and AP-1B clathrin adaptor complexes define biochemically and functionally distinct membrane domains. J. Cell Biol. 163: 351–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis, R., G. McGrath, J. Zhang, D. A. Ruddy, M. Sym et al., 2002. aph-1 and pen-2 are required for Notch pathway signaling, gamma-secretase cleavage of betaAPP, and Presenilin protein accumulation. Dev. Cell 3: 85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer, C. J., J. B. White and K. A. Jones, 2004. Mastermind recruits CycC:CDK8 to phosphorylate the Notch ICD and coordinate activation with turnover. Mol. Cell 16: 509–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futter, C. E., A. Gibson, E. H. Allchin, S. Maxwell, L. J. Ruddock et al., 1998. In polarized MDCK cells basolateral vesicles arise from clathrin-gamma-adaptin-coated domains on endosomal tubules. J. Cell Biol. 141: 611–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y., T. E. McGraw and E. Rodriguez-Boulan, 2002. The epithelial-specific adaptor AP1B mediates post-endocytic recycling to the basolateral membrane. Nat. Cell Biol. 4: 605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutte, C., M. Tsunozaki, V. A. Hale and J. R. Priess, 2002. APH-1 is a multipass membrane protein essential for the Notch signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 775–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald, I., 1998. LIN-12/Notch signaling: lessons from worms and flies. Genes Dev. 124: 1751–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley, T., 2003. Notch signaling and inherited disease syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12(Spec. no. 1): R9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., I. Livne-Bar, L. Zhou and G. L. Boulianne, 1999. Drosophila Presenilin is required for neuronal differentiation and affects Notch subcellular localization and signaling. J. Neurosci. 19: 8435–8442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halfar, K., C. Rommel, H. Stocker and E. Hafen, 2001. Ras controls growth, survival and differentiation in the Drosophila eye by different thresholds of MAP kinase activity. Development 128: 1687–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltiwanger, R. S., and P. Stanley, 2002. Modulation of receptor signaling by glycosylation: fringe is an O-fucose-beta1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1573: 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, I. K., R. W. Carthew and G. M. Rubin, 1991. The Drosophila Roughened mutation: activation of a Rap homolog disrupts eye development and interferes with cell determination. Cell 67: 717–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzog, G. A., T. Wada, H. Handa and F. Winston, 1998. Evidence that Spt4, Spt5, and Spt6 control transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 12: 357–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein, U., and K. Moses, 1995. Mechanisms of Drosophila retinal morphogenesis: the virtues of being progressive. Cell 81: 987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein, U., and G. M. Rubin, 1991. Star is required in a subset of photoreceptor cells in the developing Drosophila retina and displays dosage sensitive interactions with rough. Dev. Biol. 144: 353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein, U., I. K. Hariharan and G. M. Rubin, 1993. Star is required for neuronal differentiation in the Drosophila retina and displays dosage-sensitive interactions with Ras1. Dev. Biol. 160: 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori, K., M. Fostier, M. Ito, T. J. Fuwa, M. J. Go et al., 2004. Drosophila deltex mediates Suppressor of Hairless-independent and late-endosomal activation of Notch signaling. Development 131: 5527–5537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, R. A., A. C. Phan, M. Naeemuddin, F. A. Mapa, D. A. Ruddy et al., 2001. Single nucleotide polymorphism markers for genetic mapping in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 11: 1100–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y., Y. Ye and M. E. Fortini, 2002. Nicastrin is required for gamma-secretase cleavage of the Drosophila Notch receptor. Dev. Cell 2: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, E. J., Q. Dong and I. Greenwald, 1996. Evidence for physical and functional association between EMB-5 and LIN-12 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 273: 112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazwinska, A., C. Ribeiro and M. Affolter, 2003. Epithelial tube morphogenesis during Drosophila tracheal development requires Piopio, a luminal ZP protein. Nat. Cell Biol. 5: 895–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, B. H., S. Shah, Y. Yamaguchi, M. Seki, R. G. Phillips et al., 2004. Locus-specific requirements for Spt5 in transcriptional activation and repression in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 14: 1680–1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadesch, T., 2004. Notch signaling: the demise of elegant simplicity. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14: 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, C. D., J. R. Morris, C. Wu and F. Winston, 2000. Spt5 and spt6 are associated with active transcription and have characteristics of general elongation factors in D. melanogaster. Genes Dev. 14: 2623–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., A. Sebring, J. J. Esch, M. E. Kraus, K. Vorwerk et al., 1996. Integration of positional signals and regulation of wing formation and identity by Drosophila vestigial gene. Nature 382: 133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble, J., and P. Simpson, 1997. The LIN-12/Notch signaling pathway and its regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13: 333–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. P., and K. Moses, 2001. a EGF receptor and Notch signaling act upstream of Eyeless/Pax6 to control eye specification. Cell 104: 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J. P., and K. Moses, 2001. b The EGF receptor and Notch signaling pathways control the initiation of the morphogenetic furrow during Drosophila eye development. Development 128: 2689–2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Borgne, R., A. Bardin and F. Schweisguth, 2005. The roles of receptor and ligand endocytosis in regulating Notch signaling. Development 132: 1751–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., G. D. Jongeward and P. W. Sternberg, 1994. unc-101, a gene required for many aspects of Caenorhabditis elegans development and behavior, encodes a clathrin-associated protein. Genes Dev. 8: 60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. R., S. Urban, C. F. Garvey and M. Freeman, 2001. Regulated intracellular ligand transport and proteolysis control EGF signal activation in Drosophila. Cell 107: 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan, D., and I. Greenwald, 1995. Facilitation of lin-12-mediated signalling by sel-12, a Caenorhabditis elegans S182 Alzheimers disease gene. Nature 377: 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., M. Xu, H. Zhou, J. Ma and H. Potter, 1997. Alzheimer presenilins in the nuclear membrane, interphase kinetochores, and centrosomes suggest a role in chromosome segregation. Cell 90: 917–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., and I. Greenwald, 1997. HOP-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans presenilin, appears to be functionally redundant with SEL-12 presenilin and to facilitate LIN-12 and GLP-1 signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94: 12204–12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom, D. L., S. L. Squazzo, N. Muster, T. A. Burckin, K. C. Wachter et al., 2003. Dual roles for Spt5 in pre-mRNA processing and transcription elongation revealed by identification of Spt5-associated proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 1368–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Schier, H., and D. St. Johnston, 2002. Drosophila nicastrin is essential for the intramembranous cleavage of Notch. Dev. Cell 2: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, D. F., and B. Yedvobnick, 1995. Drosophila Notch receptor activity suppresses Hairless function during adult external sensory organ development. Genetics 141: 1491–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, P. H., and R. J. Lefkowitz, 2001. Beta-Arrestins: new roles in regulating heptahelical receptors' functions. Cell Signal. 13: 683–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, P. H., N. L. Cote, F. T. Lin, R. T. Premont, J. A. Pitcher et al., 1999. Identification of NSF as a beta-arrestin1-binding protein. Implications for beta2-adrenergic receptor regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 10677–10680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, W. E., P. H. McDonald, S. F. Cai, M. E. Field, R. J. Davis et al., 2001. Identification of a motif in the carboxyl terminus of beta -arrestin2 responsible for activation of JNK3. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 27770–27777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, M., and D. A. Agard, 2001. Gamma-tubulin complexes and microtubule nucleation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11: 174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses, K., M. C. Ellis and G. M. Rubin, 1989. The glass gene encodes a zinc-finger protein required by Drosophila photoreceptor cells. Nature 340: 531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muskavitch, M. A. T., 1994. Delta-Notch signaling and Drosophila cell fate choice. Dev. Biol. 166: 415–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, T., M. Setou, D. Seog, K. Ogasawara, N. Dohmae et al., 2000. A novel motor, KIF13A, transports mannose-6-phosphate receptor to plasma membrane through direct interaction with AP-1 complex. Cell 103: 569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, C. J., and S. M. Cohen, 1996. A hierarchy of cross-regulation involving Notch, wingless, vestigial and cut organizes the dorsal/ventral axis of the Drosophila wing. Development 122: 3477–3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimune, A., J. T. Isaac, E. Molnar, J. Noel, S. R. Nash et al., 1998. NSF binding to GluR2 regulates synaptic transmission. Neuron 21: 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel, J., G. S. Ralph, L. Pickard, J. Williams, E. Molnar et al., 1999. Surface expression of AMPA receptors in hippocampal neurons is regulated by an NSF-dependent mechanism. Neuron 23: 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, B. R., 2000. gamma-Tubulin. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 49: 27–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okajima, T., A. Xu, L. Lei and K. D. Irvine, 2005. Chaperone activity of protein O-fucosyltransferase 1 promotes Notch receptor folding. Science 307: 1599–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill, E. M., M. C. Ellis, G. M. Rubin and R. Tjian, 1995. Functional domain analysis of glass, a zinc-finger-containing transcription factor in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 6557–6561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzech, E., L. Livshits, J. Leyt, H. Okhrimenko, V. Reich et al., 2001. Interactions between adaptor protein-1 of the clathrin coat and microtubules via type 1a microtubule-associated proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 31340–31348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano, A., P. Crottet, C. Prescianotto-Baschong and M. Spiess, 2004. In vitro formation of recycling vesicles from endosomes requires adaptor protein-1/clathrin and is regulated by rab4 and the connector rabaptin-5. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 4990–5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardue, M. L., 1986. In situ hybridization to DNA of chromosomes and nuclei, pp. 111–137 in Drosophila: A Practical Approach, edited by D. B. Roberts. IRL Press, Oxford/Washington, DC.

- Parks, A. L., F. R. Turner and M. A. T. Muskavitch, 1995. Relationships between complex Delta expression and the specification of retinal cell fates during Drosophila eye development. Mech. Dev. 50: 201–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks, A. L., K. M. Klueg, J. R. Stout and M. A. Muskavitch, 2000. Ligand endocytosis drives receptor dissociation and activation in the Notch pathway. Development 127: 1373–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigino, G., A. Pelsman, H. Mori and J. Busciglio, 2001. Presenilin-1 mutations reduce cytoskeletal association, deregulate neurite growth, and potentiate neuronal dystrophy and tau phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. 21: 834–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poodry, C. A., 1990. shibire, a neurogenic mutant of Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 138: 464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portin, P., 2002. General outlines of the molecular genetics of the Notch signalling pathway in Drosophila melanogaster: a review. Hereditas 136: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigozhina, N. L., C. E. Oakley, A. M. Lewis, T. Nayak, S. A. Osmani et al., 2004. gamma-tubulin plays an essential role in the coordination of mitotic events. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 1374–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royet, J., and R. Finkelstein, 1997. Establishing primordia in the Drosophila eye-antennal imaginal disc: the roles of decapentaplegic, wingless and hedgehog. Development 124: 4793–4800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, I. M., R. M. Brown, Jr., M. Fevre, R. A. Geremia and B. Henrissat, 1995. Multidomain architecture of beta-glycosyl transferases: implications for mechanism of action. J. Bacteriol. 177: 1419–1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweisguth, F., 2004. Notch signaling activity. Curr. Biol. 14: R129–R138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweisguth, F., and M. Lecourtois, 1998. The activity of Drosophila Hairless is required in pupae but not in embryos to inhibit Notch signal transduction. Dev. Genes Evol. 208: 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe, D. J., 2000. Notch and presenilins in vertebrates and invertebrates: implications for neuronal development and degeneration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10: 50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe, D. J., 2004. Cell biology of protein misfolding: the examples of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Nat. Cell Biol. 6: 1054–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seugnet, L., P. Simpson and M. Haenlin, 1997. Requirement for dynamin during Notch signalling in Drosophila neurogenesis. Dev. Biol. 192: 585–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver, S. J., and I. Rebay, 2005. Signaling circuitries in development: insights from the retinal determination gene network. Development 132: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, M. A., D. D. L. Bowtell, G. S. Dodson, T. R. Laverty and G. M. Rubin, 1991. Ras1 and a putative guanine nucleotide exchange factor perform crucial steps in signalling by the Sevenless protein tyrosine kinase. Cell 67: 701–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeath, J. B., G. Panganiban, J. Selegue and S. B. Carroll, 1992. Gene regulation in two dimensions: the proneural achaete and scute genes are controlled by combinations of axis-patterning genes through a common intergenic control region. Genes Dev. 6: 2606–2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, I., S. Kamboj, J. Xia, H. Dong, D. Liao et al., 1998. Interaction of the N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor with AMPA receptors. Neuron 21: 393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, B. A., M. Mohtashami, L. Zhou, W. S. Trimble and G. L. Boulianne, 2001. SNARE-dependent signaling at the Drosophila wing margin. Dev. Biol. 234: 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl, G., and A. Adachi, 2000. Requirements for presenilin-dependent cleavage of Notch and other transmembrane proteins. Mol. Cell 6: 625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl, G., and I. Greenwald, 1999. Presenilin is required for activity and nuclear access of Notch in Drosophila. Nature 398: 522–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutt, H., and D. Strutt, 2003. EGF signaling and ommatidial rotation in the Drosophila eye. Curr. Biol. 13: 1451–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto, H., M. Sugahara, H. Folsch, Y. Koide, F. Nakatsu et al., 2002. Differential recognition of tyrosine-based basolateral signals by AP-1B subunit mu1B in polarized epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13: 2374–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo, S., M. Fujise, T. Akiyama, H. Habuchi, N. Itano et al., 2004. In vivo hyaluronan synthesis upon expression of the mammalian hyaluronan synthase gene in Drosophila. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 18920–18925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanzi, R. E., and L. Bertram, 2001. New frontiers in Alzheimer's disease genetics. Neuron 32: 181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tezapsidis, N., P. A. Merz, G. Merz and H. Hong, 2003. Microtubular interactions of presenilin direct kinesis of Abeta peptide and its precursors. FASEB J. 17: 1322–1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X., D. Hansen, T. Schedl and J. B. Skeath, 2004. Epsin potentiates Notch pathway activity in Drosophila and C. elegans. Development 131: 5807–5815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]