Abstract

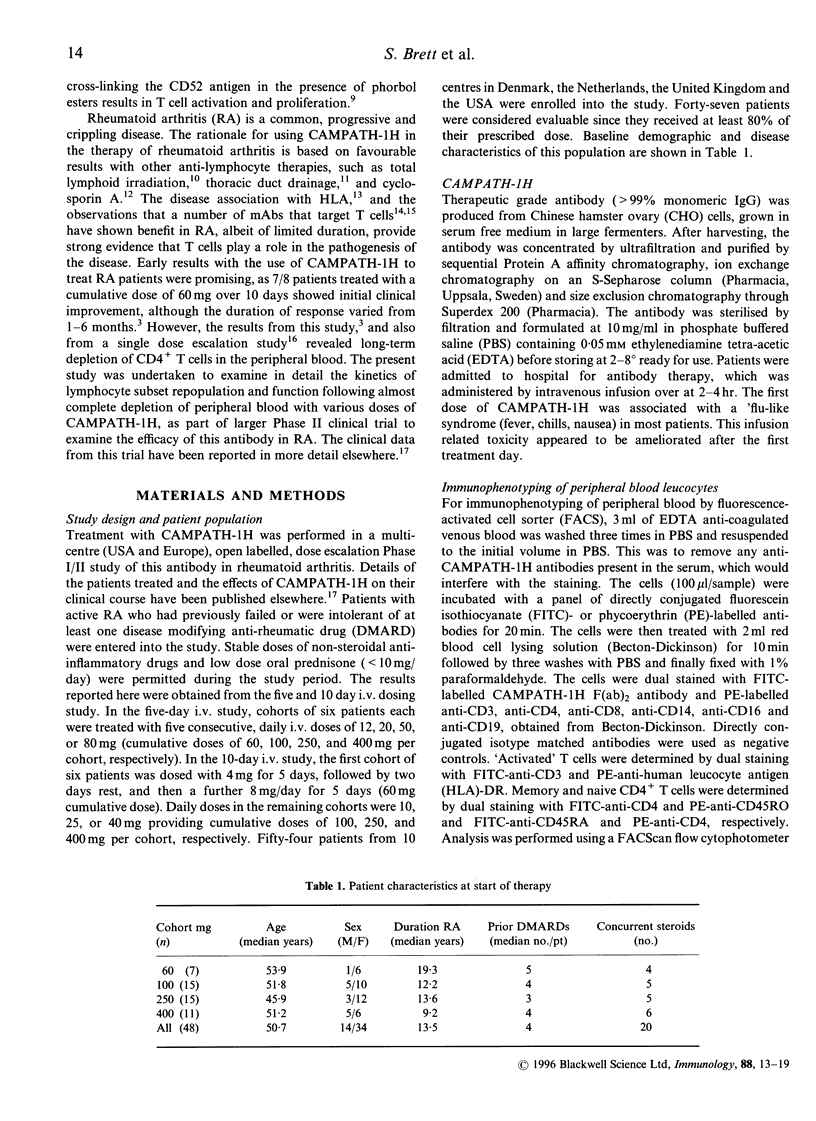

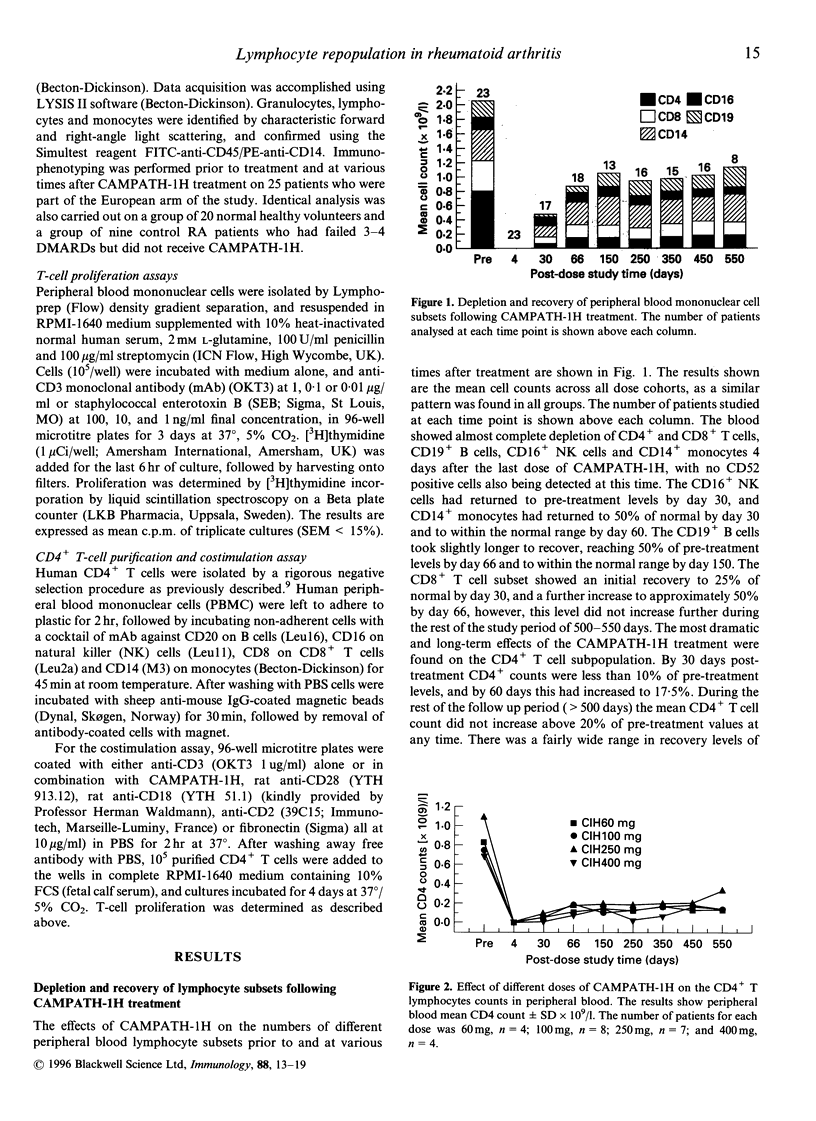

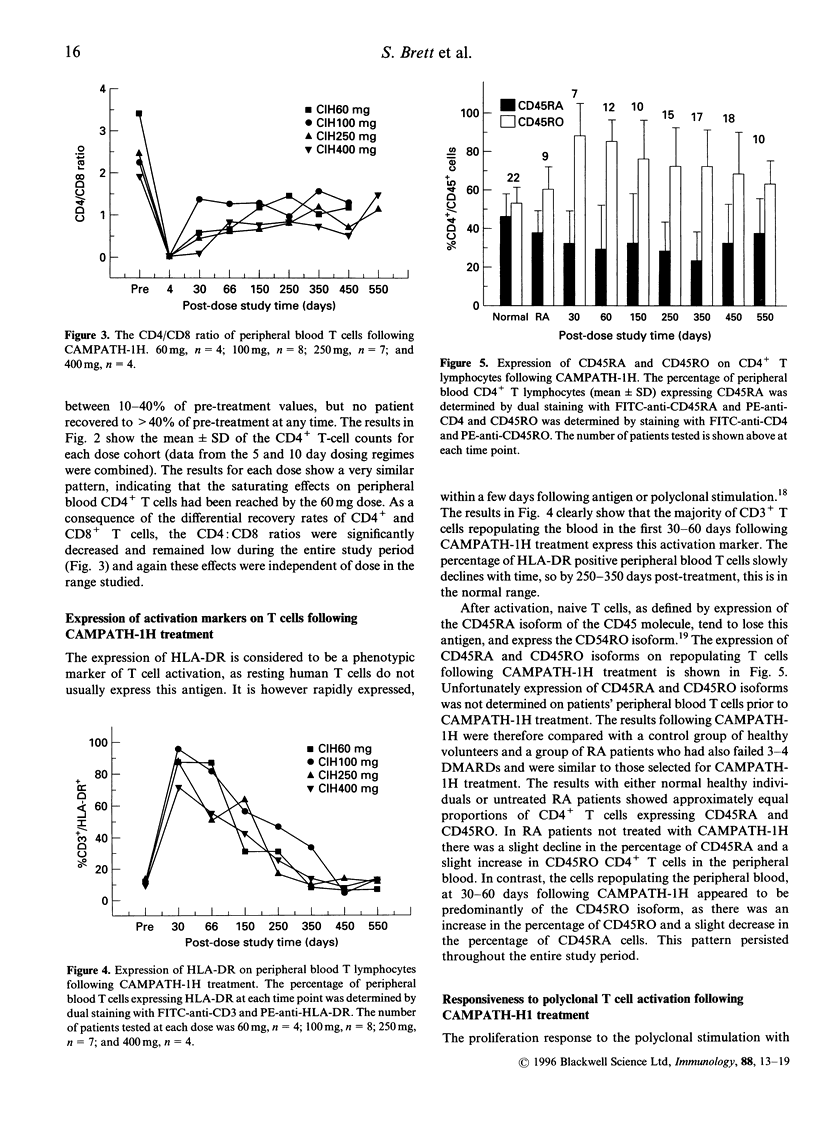

Patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis who had failed treatment with conventional therapies were treated with a course of five or 10 daily intravenous infusions of CAMPATH-1H, a humanized antibody against the CD52 antigen, resulting in profound depletion of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. During the subsequent 18 months, lymphocytes were analysed for sub-populations by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) and for proliferation in response to polyclonal T-cell stimulation with anti-CD3 or staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB). Treatment resulted in almost complete depletion of lymphocytes from the blood followed by gradual repopulation. CD16+ natural killer (NK) cells and CD14+ monocytes returned to pretreatment levels within 1-2 months. CD19+ B cells returned to within 50% of pre-treatment levels by day 66 and to within normal range by day 150, whereas CD8+ T cells recovered to 50% of pretreatment levels by day 66, but did not show any further increase during the rest of the study period. The most profound effects were on the CD4+ T lymphocyte sub-population, as the mean CD4+ count did not increase above 20% of pre-treatment level at any time during the study period (550 days), at all the doses tested. The T cells which initially repopulated the blood 1-2 months after treatment, nearly all expressed the activation markers human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-DR and CD45RO, although the percentage of T cells expressing these molecules gradually declined to normal levels over time. Proliferative responses to polyclonal T-cell stimulation (anti-CD3 and SEB) were also significantly reduced in the first few months after treatment, but recovered to pre-treatment levels by day 250. The relationship between these observations and the clinical response is discussed.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Akbar A. N., Borthwick N., Salmon M., Gombert W., Bofill M., Shamsadeen N., Pilling D., Pett S., Grundy J. E., Janossy G. The significance of low bcl-2 expression by CD45RO T cells in normal individuals and patients with acute viral infections. The role of apoptosis in T cell memory. J Exp Med. 1993 Aug 1;178(2):427–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar A. N., Salmon M., Janossy G. The synergy between naive and memory T cells during activation. Immunol Today. 1991 Jun;12(6):184–188. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beverley P. C. Functional analysis of human T cell subsets defined by CD45 isoform expression. Semin Immunol. 1992 Feb;4(1):35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe J. S., Hall V. S., Smith M. A., Cooper H. J., Tite J. P. Humanized monoclonal antibody CAMPATH-1H: myeloma cell expression of genomic constructs, nucleotide sequence of cDNA constructs and comparison of effector mechanisms of myeloma and Chinese hamster ovary cell-derived material. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992 Jan;87(1):105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty P. C. Immune exhaustion: driving virus-specific CD8+ T cells to death. Trends Microbiol. 1993 Sep;1(6):207–209. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90133-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas A. A., Rocha B. B. Lymphocyte lifespans: homeostasis, selection and competition. Immunol Today. 1993 Jan;14(1):25–29. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90320-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale G., Xia M. Q., Tighe H. P., Dyer M. J., Waldmann H. The CAMPATH-1 antigen (CDw52). Tissue Antigens. 1990 Mar;35(3):118–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1990.tb01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs J. D., Watts R. A., Hazleman B. L., Hale G., Keogan M. T., Cobbold S. P., Waldmann H. Humanised monoclonal antibody therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1992 Sep 26;340(8822):748–752. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92294-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackall C. L., Fleisher T. A., Brown M. R., Andrich M. P., Chen C. C., Feuerstein I. M., Horowitz M. E., Magrath I. T., Shad A. T., Steinberg S. M. Age, thymopoiesis, and CD4+ T-lymphocyte regeneration after intensive chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jan 19;332(3):143–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau T., Thorpe J., Miller D., Moseley I., Hale G., Waldmann H., Clayton D., Wing M., Scolding N., Compston A. Preliminary evidence from magnetic resonance imaging for reduction in disease activity after lymphocyte depletion in multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1994 Jul 30;344(8918):298–301. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus H. E., Machleder H. I., Levine S., Yu D. T., MacDonald N. S. Lymphocyte involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Studies during thoracic duct drainage. Arthritis Rheum. 1977 Jul-Aug;20(6):1249–1262. doi: 10.1002/art.1780200614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riechmann L., Clark M., Waldmann H., Winter G. Reshaping human antibodies for therapy. Nature. 1988 Mar 24;332(6162):323–327. doi: 10.1038/332323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riethmüller G., Rieber E. P., Kiefersauer S., Prinz J., van der Lubbe P., Meiser B., Breedveld F., Eisenburg J., Krüger K., Deusch K. From antilymphocyte serum to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: first experiences with a chimeric CD4 antibody in the treatment of autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev. 1992 Oct;129:81–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan W. C., Hale G., Tite J. P., Brett S. J. Cross-linking of the CAMPATH-1 antigen (CD52) triggers activation of normal human T lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1995 Jan;7(1):69–77. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruderman E. M., Weinblatt M. E., Thurmond L. M., Pinkus G. S., Gravallese E. M. Synovial tissue response to treatment with Campath-1H. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Feb;38(2):254–258. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon M., Pilling D., Borthwick N. J., Viner N., Janossy G., Bacon P. A., Akbar A. N. The progressive differentiation of primed T cells is associated with an increasing susceptibility to apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 1994 Apr;24(4):892–899. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stastny P. Association of the B-cell alloantigen DRw4 with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1978 Apr 20;298(16):869–871. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197804202981602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts R. A., Isaacs J. D. Immunotherapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992 May;51(5):577–579. doi: 10.1136/ard.51.5.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg K., Parkman R. Age, the thymus, and T lymphocytes. N Engl J Med. 1995 Jan 19;332(3):182–183. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M. Q., Hale G., Lifely M. R., Ferguson M. A., Campbell D., Packman L., Waldmann H. Structure of the CAMPATH-1 antigen, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein which is an exceptionally good target for complement lysis. Biochem J. 1993 Aug 1;293(Pt 3):633–640. doi: 10.1042/bj2930633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M. Q., Tone M., Packman L., Hale G., Waldmann H. Characterization of the CAMPATH-1 (CDw52) antigen: biochemical analysis and cDNA cloning reveal an unusually small peptide backbone. Eur J Immunol. 1991 Jul;21(7):1677–1684. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]