Abstract

The maintenance of genome stability is a fundamental requirement for normal cell cycle progression. The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an excellent model to study chromosome maintenance due to its well-defined centromere and kinetochore, the region of the chromosome and associated protein complex, respectively, that link chromosomes to microtubules. To identify genes that are linked to chromosome stability, we performed genome-wide synthetic lethal screens using a series of novel temperature-sensitive mutations in genes encoding a central and outer kinetochore protein. By performing the screens using different mutant alleles of each gene, we aimed to identify genetic interactions that revealed diverse pathways affecting chromosome stability. Our study, which is the first example of genome-wide synthetic lethal screening with multiple alleles of a single gene, demonstrates that functionally distinct mutants uncover different cellular processes required for chromosome maintenance. Two of our screens identified APQ12, which encodes a nuclear envelope protein that is required for proper nucleocytoplasmic transport of mRNA. We find that apq12 mutants are delayed in anaphase, rereplicate their DNA, and rebud prior to completion of cytokinesis, suggesting a defect in controlling mitotic progression. Our analysis reveals a novel relationship between nucleocytoplasmic transport and chromosome stability.

THE stable inheritance of chromosomes during the mitotic cell cycle requires faithful duplication of the genetic material and equal separation of sister chromatids. Chromosome instability occurs due to defects in multiple cellular functions including DNA replication, chromosome cohesion, chromosome-microtubule (MT) attachment, nucleocytoplasmic transport, and cell cycle control. The nuclear envelope (NE) houses the MT organizing centers, which in the budding yeast Saccharoymces cerevisiae are known as spindle pole bodies (SPBs). SPBs duplicate concurrently with DNA replication, allowing for the creation of a bipolar spindle onto which chromosomes attach. A large protein complex, known as the kinetochore, resides on centromere (CEN) DNA and mediates attachment of chromosomes to spindle MTs. Once all kinetochores have formed bipolar attachments with spindle MTs, the metaphase-to-anaphase transition proceeds and chromosome segregation occurs. Failure of even a single kinetochore to attach to the spindle alerts the spindle checkpoint machinery, which responds by halting cell cycle progression. Errors in chromosome segregation lead to abnormal numbers of chromosomes, or aneuploidy, which is a hallmark of cancerous cells. Mitotic spindle checkpoint failure is an important determinant in the development of aneuploid cells (Lew and Burke 2003; Rajagopalan and Lengauer 2004) and mutations in kinetochore proteins have recently been associated with a subset of aneuploid colon tumors (Wang et al. 2004).

The kinetochore is a hub of activity where centromere, chromatin, cohesin, spindle checkpoint, and MT-associated proteins gather to coordinate chromosome segregation. Inner and central kinetochore complexes assemble in a hierarchical manner onto CEN DNA and serve as a link to the Dam1 outer kinetochore complex that encircles MTs (Biggins and Walczak 2003; McAinsh et al. 2003; Miranda et al. 2005; Westermann et al. 2005). The Ndc80 complex is a highly conserved central kinetochore complex that is required for attachment of chromosomes to MTs (He et al. 2001; Janke et al. 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin 2001; Le Masson et al. 2002). Studies in multiple eukaryotic systems have shown that the Ndc80 complex is required to localize spindle checkpoint proteins to the kinetochore and that cells carrying mutations in Ndc80 complex components are defective in checkpoint signaling (Gillett et al. 2004; Maiato et al. 2004). Two of the spindle checkpoint proteins, Mad1p and Mad2p, localize to the NE, specifically to the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (Iouk et al. 2002). Upon activation of the spindle checkpoint, Mad2p and a portion of Mad1p relocalize to the kinetochore (Iouk et al. 2002; Gillett et al. 2004). In human cells, checkpoint proteins also localize to the NPC and upon NE breakdown relocalize to the kinetochore until MT attachment has occurred (Campbell et al. 2001).

During mitosis in budding yeast, the NE does not break down and growing evidence suggests that the NPC has an active role in controlling mitotic progression and chromosome segregation (Ouspenski et al. 1999; Kerscher et al. 2001; Makhnevych et al. 2003). NE-associated proteins that are required for chromosome stability, but do not appear to be structural components of the kinetochore, have been identified. For example, the nucleoporin Nup170p was identified in a genetic screen for mutants that exhibit an increased rate of chromosome loss and was subsequently shown to be required for kinetochore integrity, despite the fact that Nup170p does not interact with CEN DNA (Spencer et al. 1990; Kerscher et al. 2001). Mps2p localizes to both the SPB and the NE and is required for SPB insertion into the NE (Winey et al. 1991; Munoz-Centeno et al. 1999). Interestingly, Mps2p interacts in vivo with Spc24p, a component of the Ndc80 complex, suggesting that the kinetochore may physically interact with components of the NE (Le Masson et al. 2002). In support of a kinetochore-NE connection, CENs cluster near the SPB/NE in interphase and colocalize with SPBs during late anaphase (Goshima and Yanagida 2000; He et al. 2000; Jin et al. 2000; Pearson et al. 2001).

Our current understanding of chromosome segregation has benefited from many studies focused on protein purification and mass spectrometry analysis that have been instrumental in identifying structural components of the kinetochore (Biggins and Walczak 2003; McAinsh et al. 2003). However, the identification of proteins or pathways that affect chromosome segregation via transient or indirect interactions has remained elusive. Genetic studies, however, have the ability to identify interactions that do not rely on direct protein-protein interaction yet still affect chromosome segregation. For this reason we used the systematic genetic analysis (SGA) approach for identifying nonessential mutants from the haploid yeast gene deletion set that have a role in chromosome stability (Tong et al. 2001). SGA is a method to automate the isolation of synthetically lethal (SL) or synthetically sick (SS) interactions that occur when the combination of two viable nonallelic mutations results in cell lethality or slower growth than either individual mutant. Two mutants that have a SL/SS interaction often function in the same or parallel biological pathways (Hartman et al. 2001). As a starting point for our SGA analysis, we created three independent temperature-sensitive (Ts) alleles in members of both the Ndc80 and the Dam1 kinetochore complex. We performed genome-wide SL screens using SGA methodology with all six Ts mutants as query strains. Our study represents the first series of comparative genome-wide SL screens performed on different mutant alleles of the same gene. Using this approach, we have uncovered a novel role for the Apq12p protein, which resides in the NE, in maintaining chromosome stability and proper progression through anaphase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Creation of Ts mutants and integration into yeast strains:

The SPC24 and SPC34 ORFs (642 and 888 bp, respectively) including ∼250 bp of upstream sequence were amplified by PCR and cloned into pRS316 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989) to create pRS316-SPC24 (BVM93a) and pRS316-SPC34 (BVM95c). Both BVM93a and BVM95c were sequenced to ensure that they carried wild-type SPC24 and SPC34 sequence, respectively. SPC24 and SPC34 were PCR amplified from BVM93a and BVM95c using mutagenic conditions [100 ng template, Taq polymerase (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), 200 μm of dNTPs with either limiting dATP (40 μm) or dGTP (40 μm), 2 mm MgCl2, and 25 pmol primers]. Next, mutagenized SPC24 and SPC34 were cloned into pRS315 using homologous recombination in strains YVM503 and YVM509 that contained deletions of SPC24 and SPC34 covered by the URA3-marked plasmids carrying wild-type versions of SPC24 (BVM93a) and SPC34 (BVM95c) (Muhlrad et al. 1992). Wild-type plasmids were removed from YVM503 and YVM509 by successive incubation on media containing 5-fluoroorotic acid. Colonies now carrying mutagenized pRS315-SPC24 or pRS315-SPC34 as the sole source of either gene were incubated at 37° to identify Ts mutants, and plasmids rescued from these strains were retransformed to confirm the Ts phenotype. FACS analysis was performed on each Ts mutant after incubation at 37° for 2–6 hr. Mutants representing different FACS profiles at 37°—three spc24 (spc24-8, spc24-9, spc24-10) and three spc34 (spc34-5, spc34-6, spc34-7) mutants—were chosen for further analysis. Mutants were next integrated in the genome, replacing the wild-type SPC24 or SPC34 loci in both the SGA starting strain (Y2454) and our lab S288C background strain (YPH499) as described (Tong et al. 2001). Mutants were sequenced and the corresponding amino acid changes are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2. All yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

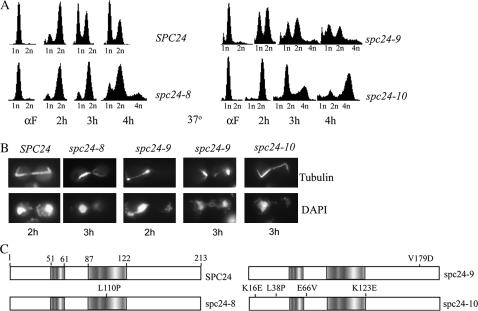

Figure 1.

Characterization of spc24 Ts mutants. (A) Wild-type (SPC24, YVM1370), spc24-8 (YVM1448), spc24-9 (YVM1380), and spc24-10 (YVM1363) strains were arrested with the mating pheromone αF at 25° and then released to 37° and samples were taken at 2, 3, and 4 hr. DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry for 1N, 2N, or 4N DNA content. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy performed on cells incubated at 37° for 2 or 3 hr post-αF release, as described in A. Cells were stained for tubulin and DNA (DAPI). (C) Schematic of amino acid (aa) substitutions in spc24 mutants. Shading identifies aa regions of Spc24p predicted to be coiled-coil domains (aa 51–aa 61 and aa 87–aa 122) on the basis of Multicoil analysis (http://multicoil.lcs.mit.edu/cgi-bin/multicoil).

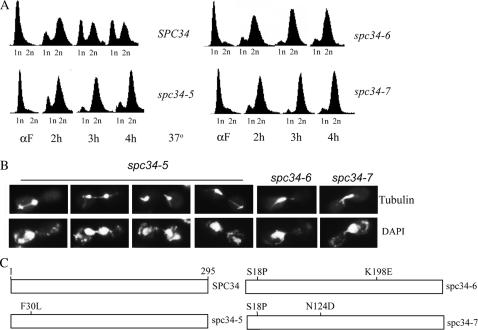

Figure 2.

Characterization of spc34 Ts mutants. (A) Wild-type (SPC34, YM61), spc34-5 (YM40), spc34-6 (YVM1864), and spc34-7 (YM41) strains were arrested with the mating pheromone αF at 25° and then released to 37° and samples were taken at 2, 3, and 4 hr. DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry for 1N, 2N, or 4N DNA content. (B) Immunofluorescence microscopy performed on cells incubated at 37° at 3 hr post-αF release, as described in A. Cells were stained for tubulin and DNA (DAPI). (C) Schematic of aa substitutions in spc34 mutants.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strain list

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| DBY1385 | MATahis4 ura3-52 tub2-104 | D. Botstein |

| DBY2501 | MATaura3-52 ade2-101 tub1-1 | D. Botstein |

| IPY1986 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 OKP1-VFP∷kanMX6 SPC29-CFP∷hphMX4 | P. Hieter |

| Y2454 | MATα mfa1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3 can1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 | Tong et al. (2001) |

| YIB329 | MATα mfa1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3 can1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 spc24-9∷URA3 | This study |

| YIB331 | MATα mfa1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3 can1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 spc24-10∷URA3 | This study |

| YIB338 | MATα mfa1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3 can1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 spc24-8∷URA3 | This study |

| YIB343 | MATα mfa1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3 can1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 spc34-5∷URA3 | This study |

| YIB351 | MATα mfa1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3 can1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 spc34-6∷URA3 | This study |

| YIB355 | MATα mfa1Δ∷MFA1pr-HIS3 can1Δ ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ1 lys2Δ0 spc34-7∷URA3 | This study |

| YM20 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 OKP1-VFP∷kanMX6 SPC29-CFP∷hphMX4 apq12ΔTRP1 | This study |

| YM40 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 spc34-5∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YM41 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 spc34-7∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YM61 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 SPC34∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YM192 | MATa/α ura3-52 ura3-52/, lys2-801/ lys2-801, ade2-101/ ade2-101, his3Δ200 his3Δ200/, leu2Δ1/ leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 spc24-8∷kanMX61/ spc24-8∷kanMX6 CFIII CEN3.d URA3 SUP11 | This study |

| YM194 | MATa/α ura3-52 ura3-52/, lys2-801/lys2-801, ade2-101/ade2-101, his3Δ200 his3Δ200/, leu2Δ1/leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 spc24-10∷kanMX61/spc24-10∷kanMX6 CFIII CEN3.d URA3 SUP11 | This study |

| YM196 | MATa/α ura3-52 ura3-52/, lys2-801/lys2-801, ade2-101/ade2-101, his3Δ200 his3Δ200/, leu2Δ1/leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 SPC24∷kanMX61/SPC24∷kanMX6 CFIII CEN3.d URA3 SUP11 | This study |

| YM160 | MATa/α ura3-52 ura3-52/, lys2-801/lys2-801, ade2-101/ade2-101, his3Δ200 his3Δ200/, leu2Δ1/leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 apq12ΔTRP1/apq12ΔTRP1 CFVII RAD2.d URA3 SUP11 | This study |

| YPH272 | MATa/α ura3-52 ura3-52/, lys2-801/lys2-801, ade2-101/ade2-101, his3Δ200 his3Δ200/, leu2Δ1/leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 CFVII RAD2.d URA3 SUP11 | P. Hieter |

| YPH499 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 | P. Hieter |

| YPH982 | MATa/α ura3-52 ura3-52/, lys2-801/lys2-801, ade2-101/ade2-101, his3Δ200 his3Δ200/, leu2Δ1/leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 CFIII CEN3.L URA3 SUP11 | P. Hieter |

| YVM503 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, spc24ΔHIS3, pBVM93a | This study |

| YVM509 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, spc34ΔHIS3, pBVM95c | This study |

| YVM1363 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 spc24-10∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1370 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 SPC24∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1380 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 spc24-9∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1448 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 spc24-8∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1579 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 SPC24-GFP∷TRP1∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1585 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 spc24-8-GFP∷TRP1∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1764 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 apq12∷TRP1 | This study |

| YVM1864 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 spc34-6∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1892 | MATa/α ura3-52 ura3-52/, lys2-801/lys2-801, ade2-101/ade2-101, his3Δ200 his3Δ200/, leu2Δ1/leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 spc24-9∷kanMX61/spc24-9∷kanMX6 CFIII CEN3.d URA3 SUP11 | This study |

| YVM1893 | MATa/α ura3-52 ura3-52/, lys2-801/ lys2-801, ade2-101/ade2-101, his3Δ200 his3Δ200/, leu2Δ1/leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63/trp1Δ63 apq12ΔTRP1/apq12ΔTRP1 CFIII CEN3.L URA3 SUP11 | This study |

| YVM1902 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 apq12∷TRP1 SPC24∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1904 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 apq12∷TRP1 spc24-10∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1906 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 apq12∷TRP1 spc24-8∷kanMX6 | This study |

| YVM1918 | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 SPC24-GFP∷TRP1∷kanMX6 apq12∷TRP1 | This study |

| YVM1919A | MATaura3-52, lys2-801, ade2-101, his3Δ200, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63 spc24-8-GFP∷TRP1∷kanMX6 apq12∷TRP1 | This study |

SL screen using SGA methodology:

The deletion mutant array was manipulated via robotics and the SL screens were performed as described (Tong et al. 2001). Each SL screen was performed twice and double mutants were detected visually for SS/SL interactions. For each query gene, all deletion mutants isolated in the first and second screen were condensed onto a mini-array and a third SL screen was performed. SS/SL interactions that were scored at least twice were first confirmed by random spore analysis (Tong et al. 2004) and then subsequently by tetrad analysis on YPD medium at 25°.

Two-dimensional hierarchical cluster analysis:

Two-dimensional (2D) hierarchical clustering was performed as described (Tong et al. 2001, 2004).

Chromosome fragment loss assay:

Quantitative half-sector analysis was performed as described (Koshland and Hieter 1987; Hyland et al. 1999). Homozygous diploid strains containing a single chromosome fragment were plated to isolate single colonies on solid media containing limiting adenine (Spencer et al. 1990). Colonies were grown at either 30° or 35° (see Table 3) for 3 days before incubation at 4° for red pigment development. Chromosome loss or 1:0 events were scored as colonies that were half red and half pink, nondisjunction or 2:0 events were scored as colonies that were half red and half white, and overreplication or 2:1 events were scored as colonies that were half white and half pink.

TABLE 3.

Chromosome loss events in spc24 and apq12 mutants

| Strain no. | Genotype (a/α) | Temperature | Total colonies | Chromosome loss (1:0 events) | Nondisjunction (2:0 events) | Overreplication or nondisjunction (2:1 events) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YM196 | SPC24∷kanMX6/SPC24∷kanMX6 CFIII CEN3.d URA3 | 30° | 24,976 | 2 × 10−4 (1.0) | 2.8 × 10−4 (1.0) | 0 |

| YM192 | spc24-8∷kanMX6/spc24-8∷kanMX6 CFIII CEN3.d URA3 | 30° | 25,488 | 6.6 × 10−3 (33) | 0 | 0 |

| YVM1892 | spc24-9∷kanMX6/spc24-9∷kanMX6 CFIII CEN3.d URA3 | 30° | 7,606 | 7.6 × 10−2 (380) | 1.3 × 10−4 (0.5) | 0 |

| YM194 | spc24-10∷kanMX6/spc24-10∷kanMX6 CFIII CEN3.d URA3 | 30° | 23,824 | 2.8 × 10−3 (14) | 0 | 0 |

| YPH982 | Wild type CFIII CEN3.L URA3 | 35° | 17,440 | 4.6 × 10−4 (1.0) | 4.1 × 10−3 (1.0) | 1.7 × 10−4 (1.0) |

| YVM1893 | apq12Δ/apq12Δ CFIII CEN3.L URA3 | 35° | 47,612 | 6.5 × 10−4 (1.4) | 2.0 × 10−3 (0.5) | 1.0 × 10−2 (58.8) |

| YPH272 | Wild type CFVII RAD2.d URA | 35° | 29,224 | 1.7 × 10−4 (1.0) | 1.4 × 10−5 (1.0) | 1.7 × 10−4 (1.0) |

| YM160 | apq12Δ/apq12Δ CFVII RAD2.d URA3 | 35° | 35,759 | 8.1 × 10−4 (4.8) | 0 | 7.4 × 10−3 (43.5) |

Preparation of yeast cell lysate and immunoblot analysis:

Cells were grown to log phase and then lysed by bead beating (Tyers et al. 1992). Fifty micrograms of protein was loaded per lane, and Western blots were performed with α-GFP monoclonal antibodies (Roche) and with α-Cdc28 antibodies (gift from Raymond Deshaies).

Cell cycle synchronization:

To assess the arrest phenotype of spc24 and spc34 Ts mutants (Figures 1 and 2), strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.2 at 25° in YPD media. α-Factor (αF) was added (5 μg/μl) and cultures were incubated for 2 hr and then released into YPD at 37°. Samples were taken every hour for FACS and immunofluorescence microscopy. For apq12Δ αF and nocodazole (Nz) arrest-release experiments (Figure 6), strains were grown to an OD600 of 0.3 at 30°. αF or Nz was added to a final concentration of 5 μm and 20 μg/ml, respectively. Cultures were incubated for 2 hr and then released into YPD. Samples were taken every 20 min for FACS and fluorescence microscopy.

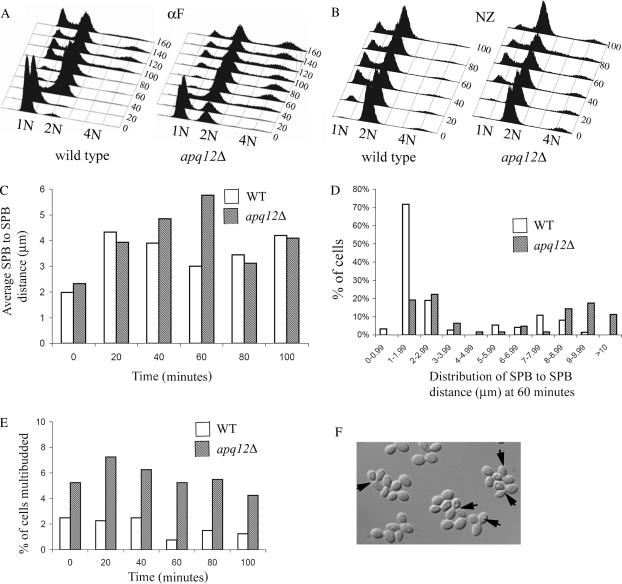

Figure 6.

apq12 mutants are delayed in anaphase and prematurely enter a new cell cycle. Wild-type (IPY1986) and apq12Δ (YM20) cells were released from αF or Nz arrest and sampled every 20 min. (A) αF- and (B) Nz-treated cells were assessed for DNA content by FACS analysis. (C) Average SPB-to-SPB distances in cells sampled from each Nz arrest time point. SPBs were marked with Spc29p-CFP and the distance was quantified from immunofluorescent images. (D) Distribution of SPB-to-SPB distances at 60 min after Nz release. (E) Percentage of multi-budded cells at each time point after Nz release. (F) DIC image of multi-budded cells at 60 min post-Nz release in an apq12Δ mutant. For each time point (C–E), 100 cells were analyzed. Experiments were performed in duplicate with representative data from one experiment shown.

FACS analysis:

FACS analysis was performed as described (Haase and Lew 1997).

Microscopy:

Genes carrying C-terminal epitope tags were designed according to Longtine et al. (1998). For immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were fixed in growth media by addition of 37% formaldehyde to 3.7% final concentration, washed, and spheroplasted. Yol 1-34 rat antitubulin antibody (Serotec, Oxford) was used with a fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibody to visualize MTs in combination with DAPI to stain DNA. Cells were imaged using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with a CoolSNAP HQ camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and Metamorph (Universal Imaging, West Chester, PA) software. Cells used for fluorescence microscopy were fixed by adding an equal volume of 4% paraformaldehyde and incubating for 10 min at 25°. Typically, a stack of 10 images was taken at 0.3-μm spacing and then the images were displayed as maximum projections for analysis. SPB-to-SPB distances were determined using Metamorph software by measuring the straight-line distance between the brightest Spc29p-CFP pixels.

RESULTS

Isolation of Ts alleles in central and outer kinetochore proteins:

To identify pathways that are important for proper chromosome segregation, we performed a series of SL screens using mutants in essential kinetochore components as query strains. We decided to focus on one member of the Ndc80 complex, Spc24p, which has previously been shown to have a role in MT attachment and spindle checkpoint control, and one member of the outer kinetochore Dam1 complex, Spc34p, which is required for MT attachment, spindle stability, and prevention of monopolar attachment (Janke et al. 2001, 2002; Wigge and Kilmartin 2001; Le Masson et al. 2002). We were concerned that genome-wide screening using only a single mutant of spc24 and spc34 might limit our results, depending on the nature of the mutation and the resulting defect in protein function. Thus we created a series of Ts mutations in both genes and selected for mutants that displayed different arrest phenotypes upon shift to nonpermissive temperature. We isolated three alleles in both SPC24 (spc24-8, spc24-9, spc24-10) and SPC34 (spc34-5, spc34-6, spc34-7) and assessed their effects on DNA content and cell morphology at 37°. Strains were arrested in G1 phase using the mating pheromone αF and then released to 37° and monitored over a period of 4 hr. Multiple spc24 Ts mutants have been created yet only one arrest phenotype has been published (Janke et al. 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin 2001; Le Masson et al. 2002). Unexpectedly, we found that all three of our spc24 alleles displayed different arrest profiles (Figure 1, A and B). The spc24-10 mutant, which carries four point mutations (Figure 1C), duplicates its chromosomes and elongates its spindles but DNA remains in the mother cells, suggesting a lack of MT attachment (Figure 1, A and B). In addition, DNA rereplicates to 4N due to continuation of the cell cycle despite the defect in chromosome segregation (Figure 1A). Previous groups have described the spc24-10 mutant arrest phenotype and have shown that the failure to arrest at the metaphase-to-anaphase transition is due to a defect in activation of the spindle checkpoint (Janke et al. 2001; Wigge and Kilmartin 2001; Le Masson et al. 2002). The other two Ts mutants of spc24 exhibited previously undescribed spc24 arrest phenotypes. spc24-8 carries one mutation in the second predicted coiled-coil domain of Spc24p (Figure 1C) and arrests with a short spindle and DNA at the bud neck, indicative of an active checkpoint arrest. The third allele, spc24-9, carries one mutation in the C terminus of Spc24p (Figure 1C) and displays a pleiotropic arrest phenotype. Three hours after shift to nonpermissive temperature, ∼30% of spc24-9 cells have discontinuous spindles that extend into the mother and break (Figure 1B). DAPI staining revealed that 3 hr after the temperature shift, unequal amounts of DNA have segregated, suggesting that partial MT attachment has occurred. The spindle defect phenotypes of spc24-9 mutants are reminiscent of the effects of some mutations in the Dam1 complex (see below).

The three spc34 mutants that we generated fall into two phenotypic classes. spc34-6 and spc34-7 mutants have a metaphase arrest phenotype at restrictive temperature with a short spindle and DNA at the bud neck as described for spc24-8 (Figure 2, A and B). In addition to having a similar arrest phenotype, spc34-6 and spc34-7 have a common amino acid mutation (S18P). However, they do not display similar genetic interactions (see below), possibly due to the K198E mutation in spc34-6, which is directly adjacent to an Ipl1p phosphorylation site (T199) (Cheeseman et al. 2002). After 3 hr at nonpermissive temperature, spc34-5 mutants have a population of mixed cells that have either a discontinuous spindle in the mother that progresses into the daughter cell and breaks (Figure 2B, first three panels from the left) or a short spindle and a MT projection (Figure 2B, fourth panel from the left). The spc34-5 mutant phenotypes are similar to those caused by the spc34-3 allele described by Janke et al. (2002). Other members of the Dam1 complex have phenotypes similar to all three of our spc34 mutants (Hofmann et al. 1998; Jones et al. 1999; Cheeseman et al. 2001a,b; Enquist-Newman et al. 2001; Janke et al. 2002).

Genome-wide SL screen with spc24 and spc34 alleles:

We introduced the spc24 and spc34 mutations into the SGA query strain and reconfirmed the mutations by sequencing and checking the arrest phenotypes at restrictive temperature (data not shown). Genome-wide SL screens were performed twice using SGA methodology by mating each query strain to the yeast deletion set and selecting for double mutants (Tong et al. 2001). Since some of the spc24 and spc34 mutants are inviable at temperatures >32°, we analyzed the double-mutant phenotypes at 25°. Any nonessential mutants that were either inviable or slow growing in combination with spc24 or spc34 mutants were placed on a miniarray and rescreened against the query strains. From our three screens, we chose genetic interactors that were identified in at least two screens and performed random spore analysis and then tetrad dissection to confirm double-mutant phenotypes. Next, the data were organized by 2D hierarchical clustering, which orders both query genes and array genes on the basis of the number of common interactions (Figure 3A). The profile of genetic interactions varied considerably depending on the allele screened.

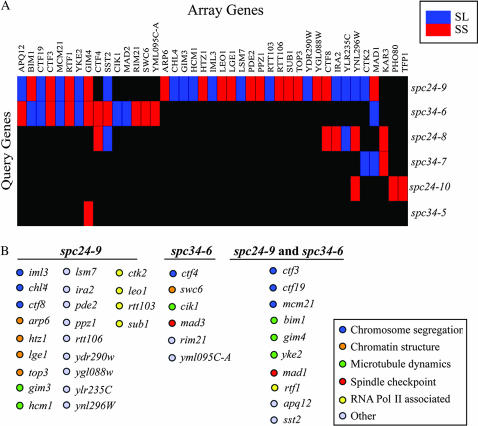

Figure 3.

spc24 and spc34 genomic SL screen. (A) 2D hierarchical cluster analysis of mutants identified in spc24 and spc34 SL screens. Rows are the spc24 and spc34 query genes and columns are the mutants, or array genes, identified in the SL screens. Blue represents SL genetic interactions whereas red represents SS genetic interactions. (B) Unique and common genes identified in the spc24-9 and spc34-6 screens. Genes are color coded on the basis of their cellular roles.

Three central kinetochore mutants (ctf3, ctf19, and mcm21) were identified in both spc24-9 and spc34-6 SL screens while two additional kinetochore mutants (iml3 and chl4) were identified in the spc24-9 screen. We were curious about whether central kinetochore mutants interact specifically with spc24-9 and spc34-6 mutants or if they were false negatives in the other spc24 and spc34 screens. To simplify our analysis we focused on the spc24 mutants by directly testing for genetic interactions via tetrad analysis. Neither spc24-8 nor spc24-10 displayed an SL or SS interaction with the chl4, ctf3, ctf19, or mcm21 central kinetochore mutant or the mad1 spindle checkpoint mutant at 25°, suggesting that the interactions with spc24-9 are indeed allele specific at this temperature (Table 2). Thus the defect in the spc24-9 mutant is more sensitive to loss of central kinetochore proteins than that in the other spc24 mutants.

TABLE 2.

Genetic interactions between spc24 and gene deletion mutants

| Query strain

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORF | SGD name | Function | spc24-9 | spc24-8 | spc24-10 |

| YIL040W | APQ12 | mRNA export | SLa | − | − |

| YDR254W | CHL4 | Central kinetochore | SL | − | − |

| YLR381W | CTF3 | Central kinetochore | SS | − | − |

| YPL018W | CTF19 | Central kinetochore | SL | − | − |

| YGL086W | MAD1 | Spindle checkpoint | SS | − | − |

| YDR318W | MCM21 | Central kinetochore | SL | − | − |

All interactions were determined at 25° on YPD media. SL, synthetic lethal; SS, synthetic sick; −, no phenotype.

Our 2D clustering analysis revealed that the spc24-9 and spc34-6 mutants have the most genetic interactions in common. We organized the array genes that were identified in both the spc24-9 and spc34-6 screens on the basis of functional groups (Figure 3B). Many of the genes have known roles in chromosome segregation, chromatin structure, MT dynamics, and spindle checkpoint function. We identified three members of the GimC/Prefoldin complex (gim3, gim4, and yke2), which is a molecular chaperone that promotes MT and actin filament folding (Geissler et al. 1998; Vainberg et al. 1998; Siegers et al. 1999; Hartl and Hayer-Hartl 2002). Genome-wide SL screens have been performed using members of the GimC/Prefoldin complex as query strains and have identified genetic interactors representing a wide variety of cellular processes (Tong et al. 2004). We also identified two members of the SWR1 chromatin-remodeling complex (arp6, swc6) that incorporates the histone H2A variant Htz1p (which was also identified in our SL screen) into nucleosomes (Korber and Horz 2004). We further identified two components of the Paf1 elongation complex, rtf1 and leo1, plus three additional mutants that interact with RNA polymerase II (ctk2, rtt103, and sub1) (Sterner et al. 1995; Henry et al. 1996; Knaus et al. 1996; Mueller and Jaehning 2002; Kim et al. 2004). Interestingly, we also identified the apq12 mutant in both the spc24-9 and spc34-6 screens. apq12 mutants are known to have defects in nuclear transport (Baker et al. 2004), and recent evidence suggests that nuclear transport is specifically regulated during mitosis (Makhnevych et al. 2003). Thus, we were interested in analyzing this potential link between nuclear transport and kinetochore function.

APQ12 genetically interacts with the kinetochore:

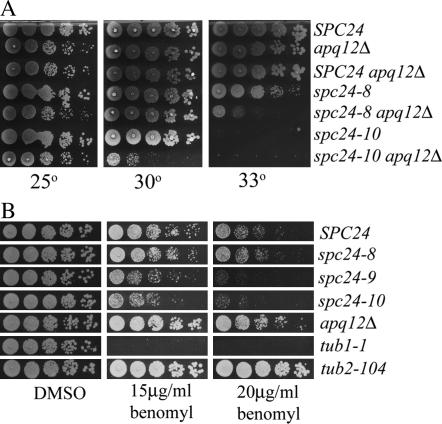

APQ12 encodes a small 16.5-kDa protein with a predicted transmembrane domain that localizes to the NE (Huh et al. 2003; Baker et al. 2004). Recently, it was shown that apq12 deletion mutants produce hyperadenylated mRNAs and accumulate poly(A)+ RNA in the nucleus, suggesting a defect in mRNA export (Baker et al. 2004). Unlike most mRNA transport mutants however, apq12 mutants also have an aberrant cell morphology, suggesting that Apq12p has additional cellular functions (Baker et al. 2004; Saito et al. 2004). apq12 deletion mutants are specifically SS/SL in combination with either spc24-9 or spc34-6 mutants but do not display a phenotype when combined with the other spc24 or spc34 mutants at 25° (Table 2 and data not shown). However, when we tested for genetic interactions between apq12Δ and the other spc24 alleles at temperatures higher than that used in our genome-wide screens (25°), we found that spc24-10 was SS in combination with apq12Δ at 30° and that the spc24-8 apq12Δ double mutant was SS at 33° (Figure 4A). Thus all three of the spc24 mutants exhibit an unexpected genetic interaction with a mutant that has mRNA export defects.

Figure 4.

Growth defects and benomyl sensitivity of spc24 and apq12 mutants. (A) Wild-type (SPC24, YVM1370), apq12Δ (YVM1764), SPC24 apq12Δ (YVM1902), spc24-8 (YVM1448), spc24-8 apq12Δ (YVM1906), spc24-10 (YVM1363), and spc24-10 apq12Δ (YVM1904) strains were grown to log phase, diluted to an OD600 of 0.1, and sequential fivefold dilutions were done. Cells were spotted onto YPD plates and incubated at 25°, 30°, and 33° for 2 days. (B) Wild-type (SPC24, YVM1370), spc24-8 (YVM1448), spc24-9 (YVM1380), spc24-10 (YVM1363), apq12Δ (YVM1764), tub1-1 (DBY2501), and tub2-104 (DBY1385) strains were grown to log phase, diluted to an OD600 of 0.1, and sequential fivefold dilutions were performed and spotted onto DMSO control 15- and 20-μg/ml benomyl plates and incubated at 30° for 2 days.

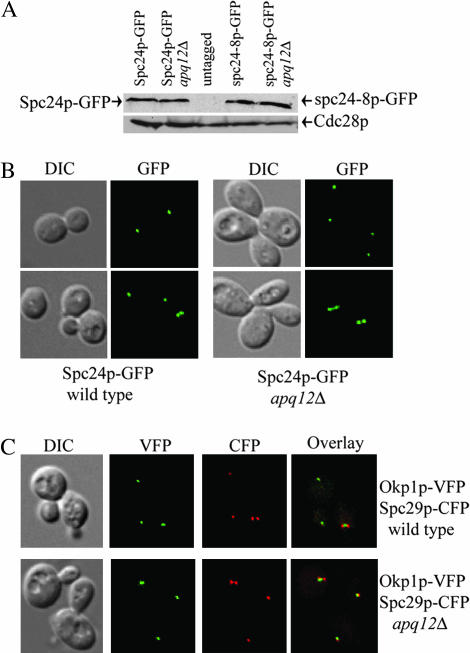

Conceivably, Apq12p could contribute to the nuclear export of SPC24 mRNA and thereby affect Spc24p cellular protein levels. Combining an SPC24 mRNA export defect with a spc24 Ts mutation could result in low levels of the Spc24p protein, which is essential, and may explain the lethality of apq12 spc24 Ts double mutants. To determine if Spc24p protein levels are perturbed in apq12Δ strains, we analyzed the stability and localization of GFP-tagged Spc24p in a log-phase apq12Δ cell population. We found that Spc24p-GFP protein levels are not notably different between a wild-type and an apq12Δ strain (Figure 5A). We also tagged the spc24-8 mutant allele with GFP and found that spc24p-8 mutant protein levels are not perturbed in apq12Δ strains (Figure 5A). spc24p-8-GFP still remains Ts and the strain arrests with the same FACS profile as that in Figure 1A, suggesting that the GFP tag does not alter the behavior of the spc24-8 mutant (data not shown). In addition, we found that both C-terminally GFP epitope-tagged spc24p-8 and spc24p-10 remain at wild-type protein levels when incubated at restrictive temperature (data not shown; spc24p-9 does not tolerate a C-terminal tag and therefore could not be assessed). Spc24p-GFP localizes to punctate foci that are close to each other in small budded cells and separated in the mother and daughter in large budded cells (Figure 5B, wild type). Spc24p-GFP still localized to distinct foci in an apq12 mutant, suggesting that kinetochore clustering and the structure of the Ndc80 complex is not significantly altered in apq12Δ strains (Figure 5B, apq12Δ). Thus, the Spc24p protein stability and localization data suggest that the Spc24p protein is not severely affected in apq12Δ strains. Therefore, apq12 mutants are unlikely to have a specific defect in SPC24 mRNA export.

Figure 5.

Spc24p protein levels and subcellular localization of Spc24p and Okp1p in apq12 mutants. (A) Spc24p-GFP and spc24p-8-GFP protein levels in an apq12Δ strain. Spc24p-GFP (YVM1579), Spc24p-GFP apq12Δ (YVM1918), untagged (YPH499), spc24p-8-GFP (YVM1585), and spc24p-8-GFP apq12Δ (YVM1919A) strains were grown to log phase at 30° and lysates were prepared. Western blots were performed and immunostained with an anti-GFP antibody (top). As a loading control, the anti-GFP blot was reprobed with an anti-Cdc28 antibody (bottom). (B) Spc24p-GFP subcellular localization in an apq12Δ strain. DIC and fluorescent images of Spc24p-GFP localization in wild-type (YVM1579) and apq12Δ (YVM1918) strains. GFP signal appears green. (C) Okp1p-VFP Spc29p-CFP subcellular localization in an apq12Δ strain. DIC and fluorescent images of Okp1p-VFP Spc29p-CFP localization in wild-type (IPY1986) and apq12Δ (YM20) strains. VFP signal appears green and CFP signal appears red.

To determine if apq12 mutants have a defect in overall kinetochore structure, we analyzed the localization of a central kinetochore protein fused to the venus fluorescent protein (VFP) Okp1p-VFP in relation to an SPB protein fused to the cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) Spc29p-CFP in apq12Δ cells. Kinetochore proteins localize to the nuclear side of each SPB in cells with short spindles and colocalize with SPBs in cells with long spindles (Goshima and Yanagida 2000; He et al. 2000; Pearson et al. 2001). Okp1p-VFP Spc29p-CFP localization was unperturbed in apq12Δ cells, suggesting that kinetochore structure and dynamics are not greatly altered in apq12 mutants (Figure 5C).

apq12 mutants have aberrant chromosome segregation:

Since Spc24p protein levels and localization appear to be normal in apq12 mutants, we asked if apq12 mutants might have phenotypes that suggest a defect in chromosome stability. We used a colony-color-based half-sector assay to determine if apq12Δ strains were able to maintain a nonessential chromosome fragment (CF) at wild-type levels (Koshland and Hieter 1987). We also assayed CF missegregation in the three spc24 Ts mutants to compare CF loss phenotypes among the different mutants. As expected, the spc24 mutants showed an increased rate of chromosome loss (1:0 events) compared to wild type (Table 3). Interestingly, spc24-9 had a much higher rate of chromosome loss (380-fold increase) compared to spc24-8 and spc24-10 (33- and 14-fold increase, respectively) at 30°. apq12 mutants did not display a significant increase in chromosome loss compared to the wild-type strain but did show a dramatic increase (58.8-fold over wild type) in 2:1 segregation events when plated at 35°. For 2:1 segregation to occur in the first mitotic division (which gives rise to half-sectored colonies), the parental cell must overreplicate the CF to three or more copies and segregate two or more copies to one cell and one copy to the other cell. We were concerned that there might be a selective advantage for apq12 deletion strains to acquire an extra copy of the CF (CFIII CEN3.L) that contains part of chromosome III, even though the wild-type copy of APQ12 is located on chromosome IX and thus not on the CF. We therefore performed the sector assay using a different CF (CFVII RAD2.d) and still saw a significant increase (43.5-fold over wild type) in 2:1 segregation events for apq12Δ strains (Table 3).

Mutants that have defects in chromosome segregation, including kinetochore mutants, are often sensitive to the microtubule-depolymerizing drug benomyl. Although the precise mechanism of benomyl action is not known, evidence suggests that it may bind to the α- and β-tubulin heterodimers, thereby inhibiting MT formation (Richards et al. 2000). We plated the apq12Δ mutant and the three spc24 Ts mutants, as well as tubulin mutant control strains, on plates to test their sensitivity to benomyl. To our surprise, we found that apq12Δ strains are resistant to benomyl and grow nearly as well as a tub2-104-resistant allele on 20 μg/ml benomyl plates at 30° (Figure 4B). In contrast, we found that the spc24-9 and spc24-10 mutants are sensitive to 15 and 20 μg/ml benomyl (Figure 4B). Resistance to benomyl suggests that apq12 mutants may have stabilized MTs or high levels of tubulin. We performed antitubulin immunofluorescence on fixed apq12 log-phase cells but did not note any striking differences in MT formation (data not shown), although the resolution may not have been sufficient to detect minor changes in MT levels or structure. Thus, apq12Δ strains may have stabilized MTs or be resistant to benomyl due to an indirect mechanism.

apq12 mutants have defects in exiting mitosis:

The 2:1 CF segregation phenotype and benomyl resistance of apq12Δ mutants are indicative of problems during mitosis. We compared the progression of a wild-type vs. an apq12Δ strain through the cell cycle by synchronizing cells in G1 with the mating pheromone αF and releasing them into the cell cycle. Each strain carried a kinetochore and a SPB marker (Okp1p-VFP and Spc29p-CFP, respectively). Samples were taken every 20 min for DNA profiling by FACS analysis and for kinetochore-SPB localization analysis by fluorescence microscopy. After release from the αF arrest we found that wild-type and apq12Δ strains showed similar timing of bud emergence and SPB duplication by analyzing fixed cells (data not shown). FACS analysis indicated that the timing of DNA replication was also similar (Figure 6A, compare 40-min time points). However, we found that apq12Δ cells showed a reproducible delay in the reappearance of 1N cells by ∼20 min (Figure 6A; compare 100-min time points) and that the population of 1N cells remained small compared to wild type throughout the time course (Figure 6A). Wild-type cells showed a transient appearance of 4N DNA, which disappeared by 160 min, whereas the apq12Δ cells had a 4N population of cells from 40 min onward, suggesting that a percentage of apq12 mutants rereplicate DNA prior to exiting mitosis (Figure 6A). Finally, we repeatedly found that apq12Δ cells had an increased proportion of 2N cells when arrested with αF, suggesting that a percentage of apq12Δ G1 cells are carrying an extra copy of all chromosomes or that a percentage of apq12Δ cells do not respond to mating pheromone (Figure 6A, 0 min, apq12Δ). Our observations are consistent with a delay for apq12 mutants in progression through mitosis and a failure to complete mitosis prior to initiating replication.

To define the stage of mitosis that is delayed in apq12Δ mutants, we performed a similar experiment using the MT-depolymerizing drug Nz to arrest cells in metaphase. apq12 mutants arrest primarily with a 2N population of cells after 2 hr exposure to Nz and with a peak of 4N cells that persists throughout the apq12Δ time course (Figure 6B). Although a small peak of 4N cells is detectable in wild-type cells responding to Nz, a greater proportion of apq12Δ cells contain a 4N quantity of DNA in the Nz-imposed G2 arrest (Figure 6B). The DNA profile of apq12Δ cells released from Nz arrest showed an ∼20 min delay in the reappearance of 1N cells compared to wild-type cells as was seen in the G1 synchronization experiment (Figure 6B; compare 20- and 40-min time points). We also monitored the distance between two Spc29p-CFP foci, as an indicator of spindle length, and found that wild-type and apq12Δ cells entered anaphase with similar kinetics. However, anaphase spindles persisted longer in the apq12Δ cell population, suggesting that apq12Δ cells are delayed during mitosis (Figure 6C). More specifically, at 60 min post-Nz release, 70% of wild-type cells had a spindle length of 1–1.99 μm, suggesting that they had progressed from anaphase to G1 (Figure 6D). In contrast, only 19% of the apq12Δ cells had a 1- to 1.99-μm spindle and 28% of the cells had a spindle between 8 and 10 μm, suggesting that the cells were still in anaphase (Figure 6D). In addition, 12% of apq12 mutants had spindle lengths >10 μm whereas none of the wild-type spindles reached this length. Finally, we also noted that the apq12 mutant population contained multibudded cells throughout the time course, even immediately after release from Nz exposure, suggesting that some cells might be breaking through the mitotic checkpoint arrest (Figure 6E). The appearance of apq12Δ cells with multiple buds and 4N DNA content suggests that cells attempt to reenter the cell cycle prior to completing cytokinesis.

DISCUSSION

We employed genome-wide SL screens using novel mutations in kinetochore proteins to uncover genes important for chromosome stability when kinetochore function is compromised. We identified a component of the NE called Apq12p that had not been previously linked to chromosome segregation. Our data demonstrate that Apq12p has a role in the timely execution of anaphase and the maintenance of chromosome stability and provide evidence that the NE is intimately linked with chromosome segregation.

The results of our SL screens highlight the importance of using multiple alleles of essential genes as queries in SGA analysis. Moreover, allele-specific interactions provide information about functional domains of the query protein. For instance, our SL data suggest that Spc24p can be divided into distinct functional domains. spc24-9, which carries a mutation in the C terminus of Spc24p, was SS or SL with the chl4, ctf3, ctf19, iml3, and mcm21 central kinetochore mutants. spc24-8 and spc24-10, which carry mutations in the N-terminal region of Spc24p that contains two coiled-coil domains, did not display genetic interactions with central kinetochore mutants at 25°. spc24-9 mutants also have a much higher rate of chromosome loss than spc24-8 and spc24-10 mutants (Table 3). Thus it is likely that the C-terminal mutation in spc24-9 affects a different Spc24p function or protein-protein interaction than do the spc24-8 and spc24-10 mutants. Our data are consistent with a recently published structural analysis of the Ndc80 complex, which demonstrates that the C terminus of Spc24p is a globular domain that likely interacts with the kinetochore (Wei et al. 2005).

In addition to identifying numerous central kinetochore mutants, we also identified two negative regulators of the cAMP pathway, ira2 and pde2, in the spc24-9 genome-wide SL screen (Figure 3). Interestingly, PDE2 was recently identified as a high-copy suppressor of Dam1 complex mutants (Li et al. 2005). Five negative regulators of the cAMP pathway, including ira2 and pde2, were also identified as benomyl-sensitive mutants in genome-wide screens (Pan et al. 2004). Thus upregulation of the cAMP pathway by mutation of its negative regulators appears to have a deleterious effect on kinetochore function.

The apq12 mutant, which has defects in mRNA nucleocytoplasmic transport (Baker et al. 2004), was identified in both the spc24-9 and spc34-6 screens. Given the role of Apq12p in mRNA transport, one possibility is that Apq12p could direct the nucleocytoplasmic export of specific mRNAs expressing kinetochore proteins. In this hypothesis, mutation of APQ12 could cause nuclear retention of these mRNAs and improper expression of their protein products. However, our data suggest that Spc24p protein levels and localization are not altered in apq12 mutants, further suggesting that Spc24p protein expression is not affected (Figure 5, A and B). In addition, the Okp1p central kinetochore protein displayed a typical kinetochore localization pattern in apq12Δ cells, suggesting that the kinetochore is intact (Figure 5C). Finally, apq12 mutants are resistant to benomyl (Figure 4B), whereas cells carrying mutations in kinetochore components or spindle checkpoint proteins are often benomyl sensitive, suggesting that apq12 mutants do not contain reduced levels of kinetochore and spindle checkpoint proteins.

Since apq12 mutants appear to have normal levels of kinetochore proteins, Apq12p could have a direct role in chromosome segregation and cell cycle regulation by coordinating the localization of specific protein components to the NE. Recently, identified links between the NPC and the kinetochore have given precedent for communication between the NE and the spindle checkpoint machinery (Stukenberg and Macara 2003; Loiodice et al. 2004; Rabut et al. 2004). For example, the Mad1p and Mad2p spindle checkpoint proteins localize to the NPC in both yeast and mammalian cells (Campbell et al. 2001; Iouk et al. 2002). The yeast Nup53 complex sequesters Mad1p and Mad2p in the NE (Iouk et al. 2002). Interestingly, both mutants in the Nup53 complex and apq12 mutants are resistant to benomyl, whereas other Nup mutants are not benomyl resistant, suggesting that a specific class of NE proteins may have a role in chromosome segregation (Figure 4B; Iouk et al. 2002). We analyzed the localization patterns of Mad1p and Mad2p in apq12 mutants both during normal cell growth and in response to the spindle checkpoint induced by Nz. However, we were unable to detect any changes in Mad1p or Mad2p localization in apq12Δ strains compared to a wild-type strain, suggesting that Apq12p is not required to sequester spindle checkpoint proteins in the NE (data not shown). Thus Apq12p has an alternative role at the NE, perhaps by sequestering or trafficking other chromosome segregation proteins via the NE and NPC.

The data presented in this article reveal a new role for Apq12p in cell cycle progression. apq12 mutants are delayed during mitosis and accumulate in anaphase, suggesting a defect in mitotic exit (Figure 6, C and D). Using two methods of cell synchrony, we found that a small percentage of apq12 mutants rereplicate their DNA and rebud prior to completing cytokinesis (Figure 6, A, B, and E). During mitosis, the transition from metaphase to anaphase is marked by degradation of the anaphase inhibitor protein Pds1p (Cohen-Fix et al. 1996; Yamamoto et al. 1996a,b). Stabilization of Pds1p is a hallmark of cells that are actively responding to the spindle checkpoint pathway; thus pds1 mutants are defective in the spindle checkpoint response. Recent genetic studies identified an SL interaction between pds1 and apq12 and between mad2 and apq12 (Sarin et al. 2004). Therefore, the mitotic defects of apq12Δ mutants render the spindle checkpoint pathway essential during normal cell growth.

Apq12p is one of a growing member of NE-associated proteins that have a role in chromosome stability and mitotic progression. For example, Sac3p is a nuclear-pore-associated protein that connects transcription elongation with mRNA export (Fischer et al. 2002). sac3 deletion mutants accumulate in mitosis as large budded cells with extended MTs, are resistant to benomyl, and have an increased rate of chromosome loss compared to wild-type strains (Bauer and Kolling 1996; Jones et al. 2000). In a previous genome-wide SL screen, we identified a genetic interaction between sac3 and cep3-2 (an inner kinetochore protein), further supporting a role for Sac3p in chromosome segregation (Measday et al. 2005). A component of the SPB called Mps3p is another example of the connection between the NE and the chromosome. Mps3p interacts with the Ctf7p cohesin protein and is required to maintain wild-type levels of cohesion between chromosomes (Antoniacci et al. 2004).

In mammalian cells, where the NE disassembles, multiple proteins located at the NPC relocalize to the kinetochore upon NE breakdown (Stukenberg and Macara 2003). Ran is a small GTPase that regulates the interaction of cargo proteins with nucleoporins. The Ran GTPase-activating protein RanGAP1 and its associated nucleoporin RanBP2 are targeted to kinetochores in a MT- and Ndc80-complex-dependent fashion (Joseph et al. 2004). In addition, RanGAP1 and RanBP2 are required for the kinetochore localization of both spindle checkpoint and kinetochore proteins and for maintaining kinetochore-MT interactions (Joseph et al. 2004). Although no nucleoporin has been shown to relocalize to the kinetochore in yeast, the Nnf1p kinetochore protein was originally identified from a purification of NE proteins, and yeast cells depleted of Nnf1p accumulate poly(A)+ RNA (Shan et al. 1997). The molecular mechanism by which NE proteins, such as Apq12p, and kinetochore proteins interact may be a conserved cellular process that functions to promote proper chromosome segregation and mitotic progression.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Baker, M. Basrai, K. Kitagawa, K. McManus, and I. Pot for comments on the manuscript. We also thank B. Sheikh and C. Boone for 2D hierarchical clustering analysis, B. Andrews for SL screening, I. Pot for the strain IPY1986, and the University of Washington Yeast Resource Center for the gift of the Spc29p-CFP tagging plasmid. This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) operating grant to V.M. and operating grants from the CIHR and the National Institutes of Health to P.H. V.M. was supported by a CIHR senior research fellowship and a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) postdoctoral fellowship and is a Canada Research Chair in Enology and Yeast Genomics and a MSFHR Scholar. B.M. was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) doctoral postgraduate scholarship, an NSERC Canada graduate scholarship, and an MSFHR trainee award.

References

- Antoniacci, L. M., M. A. Kenna, P. Uetz, S. Fields and R. V. Skibbens, 2004. The spindle pole body assembly component mps3p/nep98p functions in sister chromatid cohesion. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 49542–49550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, K. E., J. Coller and R. Parker, 2004. The yeast Apq12 protein affects nucleocytoplasmic mRNA transport. RNA 10: 1352–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A., and R. Kolling, 1996. The SAC3 gene encodes a nuclear protein required for normal progression of mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 109 (Pt. 6): 1575–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggins, S., and C. E. Walczak, 2003. Captivating capture: how microtubules attach to kinetochores. Curr. Biol. 13: R449–R460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M. S., G. K. Chan and T. J. Yen, 2001. Mitotic checkpoint proteins HsMAD1 and HsMAD2 are associated with nuclear pore complexes in interphase. J. Cell Sci. 114: 953–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman, I. M., C. Brew, M. Wolyniak, A. Desai, S. Anderson et al., 2001. a Implication of a novel multiprotein Dam1p complex in outer kinetochore function. J. Cell Biol. 155: 1137–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman, I. M., M. Enquist-Newman, T. Muller-Reichert, D. G. Drubin and G. Barnes, 2001. b Mitotic spindle integrity and kinetochore function linked by the Duo1p/Dam1p complex. J. Cell Biol. 152: 197–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman, I. M., S. Anderson, M. Jwa, E. M. Green, J. Kang et al., 2002. Phospho-regulation of kinetochore-microtubule attachments by the Aurora kinase Ipl1p. Cell 111: 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Fix, O., J. M. Peters, M. W. Kirschner and D. Koshland, 1996. Anaphase initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is controlled by the APC-dependent degradation of the anaphase inhibitor Pds1p. Genes Dev. 10: 3081–3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enquist-Newman, M., I. M. Cheeseman, D. Van Goor, D. G. Drubin, P. B. Meluh et al., 2001. Dad1p, third component of the Duo1p/Dam1p complex involved in kinetochore function and mitotic spindle integrity. Mol. Biol. Cell 12: 2601–2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T., K. Strasser, A. Racz, S. Rodriguez-Navarro, M. Oppizzi et al., 2002. The mRNA export machinery requires the novel Sac3p-Thp1p complex to dock at the nucleoplasmic entrance of the nuclear pores. EMBO J. 21: 5843–5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissler, S., K. Siegers and E. Schiebel, 1998. A novel protein complex promoting formation of functional alpha- and gamma-tubulin. EMBO J. 17: 952–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillett, E. S., C. W. Espelin and P. K. Sorger, 2004. Spindle checkpoint proteins and chromosome-microtubule attachment in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 164: 535–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshima, G., and M. Yanagida, 2000. Establishing biorientation occurs with precocious separation of the sister kinetochores, but not the arms, in the early spindle of budding yeast. Cell 100: 619–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase, S. B., and D. J. Lew, 1997. Flow cytometric analysis of DNA content in budding yeast. Methods Enzymol. 283: 322–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl, F. U., and M. Hayer-Hartl, 2002. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science 295: 1852–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, J. L., IV, B. Garvik and L. Hartwell, 2001. Principles for the buffering of genetic variation. Science 291: 1001–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., S. Asthana and P. K. Sorger, 2000. Transient sister chromatid separation and elastic deformation of chromosomes during mitosis in budding yeast. Cell 101: 763–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., D. R. Rines, C. W. Espelin and P. K. Sorger, 2001. Molecular analysis of kinetochore-microtubule attachment in budding yeast. Cell 106: 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, N. L., D. A. Bushnell and R. D. Kornberg, 1996. A yeast transcriptional stimulatory protein similar to human PC4. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 21842–21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, C., I. M. Cheeseman, B. L. Goode, K. L. McDonald, G. Barnes et al., 1998. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Duo1p and Dam1p, novel proteins involved in mitotic spindle function. J. Cell Biol. 143: 1029–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh, W. K., J. V. Falvo, L. C. Gerke, A. S. Carroll, R. W. Howson et al., 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425: 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K. M., J. Kingsbury, D. Koshland and P. Hieter, 1999. Ctf19p: a novel kinetochore protein in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and a potential link between the kinetochore and mitotic spindle. J. Cell Biol. 145: 15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iouk, T., O. Kerscher, R. J. Scott, M. A. Basrai and R. W. Wozniak, 2002. The yeast nuclear pore complex functionally interacts with components of the spindle assembly checkpoint. J. Cell Biol. 159: 807–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke, C., J. Ortiz, J. Lechner, A. Shevchenko, A. Shevchenko et al., 2001. The budding yeast proteins Spc24p and Spc25p interact with Ndc80p and Nuf2p at the kinetochore and are important for kinetochore clustering and checkpoint control. EMBO J. 20: 777–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke, C., J. Ortiz, T. U. Tanaka, J. Lechner and E. Schiebel, 2002. Four new subunits of the Dam1-Duo1 complex reveal novel functions in sister kinetochore biorientation. EMBO J. 21: 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q. W., J. Fuchs and J. Loidl, 2000. Centromere clustering is a major determinant of yeast interphase nuclear organization. J. Cell Sci. 113 (Pt. 11): 1903–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. L., B. B. Quimby, J. K. Hood, P. Ferrigno, P. H. Keshava et al., 2000. SAC3 may link nuclear protein export to cell cycle progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 3224–3229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. H., J. B. Bachant, A. R. Castillo, T. H. Giddings, Jr. and M. Winey, 1999. Yeast Dam1p is required to maintain spindle integrity during mitosis and interacts with the Mps1p kinase. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 2377–2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, J., S. T. Liu, S. A. Jablonski, T. J. Yen and M. Dasso, 2004. The RanGAP1-RanBP2 complex is essential for microtubule-kinetochore interactions in vivo. Curr. Biol. 14: 611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher, O., P. Hieter, M. Winey and M. A. Basrai, 2001. Novel role for a Saccharomyces cerevisiae nucleoporin, Nup170p, in chromosome segregation. Genetics 157: 1543–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M., N. J. Krogan, L. Vasiljeva, O. J. Rando, E. Nedea et al., 2004. The yeast Rat1 exonuclease promotes transcription termination by RNA polymerase II. Nature 432: 517–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus, R., R. Pollock and L. Guarente, 1996. Yeast SUB1 is a suppressor of TFIIB mutations and has homology to the human co-activator PC4. EMBO J. 15: 1933–1940. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber, P., and W. Horz, 2004. SWRred not shaken: mixing the histones. Cell 117: 5–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland, D., and P. Hieter, 1987. Visual assay for chromosome ploidy. Methods Enzymol. 155: 351–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Masson, I., C. Saveanu, A. Chevalier, A. Namane, R. Gobin et al., 2002. Spc24 interacts with Mps2 and is required for chromosome segregation, but is not implicated in spindle pole body duplication. Mol. Microbiol. 43: 1431–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew, D. J., and D. J. Burke, 2003. The spindle assembly and spindle position checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Genet. 37: 251–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. M., Y. Li and S. J. Elledge, 2005. Genetic analysis of the kinetochore DASH complex reveals an antagonistic relationship with the Ras/protein kinase A pathway and a novel subunit required for Ask1 association. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 767–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiodice, I., A. Alves, G. Rabut, M. Van Overbeek, J. Ellenberg et al., 2004. The entire Nup107–160 complex, including three new members, is targeted as one entity to kinetochores in mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 3333–3344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie, III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach et al., 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14: 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiato, H., J. Deluca, E. D. Salmon and W. C. Earnshaw, 2004. The dynamic kinetochore-microtubule interface. J. Cell Sci. 117: 5461–5477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhnevych, T., C. P. Lusk, A. M. Anderson, J. D. Aitchison and R. W. Wozniak, 2003. Cell cycle regulated transport controlled by alterations in the nuclear pore complex. Cell 115: 813–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAinsh, A. D., J. D. Tytell and P. K. Sorger, 2003. Structure, function, and regulation of budding yeast kinetochores. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 19: 519–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measday, V., K. Baetz, J. Guzzo, K. Yuen, T. Kwok et al., 2005. Systematic yeast synthetic lethal and synthetic dosage lethality screens identify genes required for chromosome segregation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miranda, J. L., P. De Wulf, P. Sorger and S. C. Harrison, 2005. The yeast DASH complex forms closed rings on microtubules. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12: 138–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, C. L., and J. A. Jaehning, 2002. Ctr9, Rtf1, and Leo1 are components of the Paf1/RNA polymerase II complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 1971–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlrad, D., R. Hunter and R. Parker, 1992. A rapid method for localized mutagenesis of yeast genes. Yeast 8: 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Centeno, M. C., S. McBratney, A. Monterrosa, B. Byers, C. Mann et al., 1999. Saccharomyces cerevisiae MPS2 encodes a membrane protein localized at the spindle pole body and the nuclear envelope. Mol. Biol. Cell 10: 2393–2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouspenski, II, S. J. Elledge and B. R. Brinkley, 1999. New yeast genes important for chromosome integrity and segregation identified by dosage effects on genome stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 27: 3001–3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X., D. S. Yuan, D. Xiang, X. Wang, S. Sookhai-Mahadeo et al., 2004. A robust toolkit for functional profiling of the yeast genome. Mol. Cell 16: 487–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C. G., P. S. Maddox, E. D. Salmon and K. Bloom, 2001. Budding yeast chromosome structure and dynamics during mitosis. J. Cell Biol. 152: 1255–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabut, G., P. Lenart and J. Ellenberg, 2004. Dynamics of nuclear pore complex organization through the cell cycle. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16: 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, H., and C. Lengauer, 2004. Aneuploidy and cancer. Nature 432: 338–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, K. L., K. R. Anders, E. Nogales, K. Schwartz, K. H. Downing et al., 2000. Structure-function relationships in yeast tubulins. Mol. Biol. Cell 11: 1887–1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito, T. L., M. Ohtani, H. Sawai, F. Sano, A. Saka et al., 2004. SCMD: Saccharomyces cerevisiae Morphological Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: D319–D322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin, S., K. E. Ross, L. Boucher, Y. Green, M. Tyers et al., 2004. Uncovering novel cell cycle players through the inactivation of securin in budding yeast. Genetics 168: 1763–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, X., Z. Xue, G. Euskirchen and T. Melese, 1997. NNF1 is an essential yeast gene required for proper spindle orientation, nucleolar and nuclear envelope structure and mRNA export. J. Cell Sci. 110 (Pt. 14): 1615–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegers, K., T. Waldmann, M. R. Leroux, K. Grein, A. Shevchenko et al., 1999. Compartmentation of protein folding in vivo: sequestration of non-native polypeptide by the chaperonin-GimC system. EMBO J. 18: 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter, 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122: 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, F., S. L. Gerring, C. Connelly and P. Hieter, 1990. Mitotic chromosome transmission fidelity mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 124: 237–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner, D. E., J. M. Lee, S. E. Hardin and A. L. Greenleaf, 1995. The yeast carboxyl-terminal repeat domain kinase CTDK-I is a divergent cyclin-cyclin-dependent kinase complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15: 5716–5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenberg, P. T., and I. G. Macara, 2003. The kinetochore NUPtials. Nat. Cell Biol. 5: 945–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. H., M. Evangelista, A. B. Parsons, H. Xu, G. D. Bader et al., 2001. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294: 2364–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. H., G. Lesage, G. D. Bader, H. Ding, H. Xu et al., 2004. Global mapping of the yeast genetic interaction network. Science 303: 808–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyers, M., G. Tokiwa, R. Nash and B. Futcher, 1992. The Cln3-Cdc28 kinase complex of S. cerevisiae is regulated by proteolysis and phosphorylation. EMBO J. 11: 1773–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainberg, I. E., S. A. Lewis, H. Rommelaere, C. Ampe, J. Vandekerckhove et al., 1998. Prefoldin, a chaperone that delivers unfolded proteins to cytosolic chaperonin. Cell 93: 863–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z., J. M. Cummins, D. Shen, D. P. Cahill, P. V. Jallepalli et al., 2004. Three classes of genes mutated in colorectal cancers with chromosomal instability. Cancer Res. 64: 2998–3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, R. R., P. K. Sorger and S. C. Harrison, 2005. Molecular organization of the Ndc80 complex, an essential kinetochore component. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 5363–5367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, S., A. Avila-Sakar, H. W. Wang, H. Niederstrasser, J. Wong et al., 2005. Formation of a dynamic kinetochore-microtubule interface through assembly of the Dam1 ring complex. Mol. Cell 17: 277–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge, P. A., and J. V. Kilmartin, 2001. The Ndc80p complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains conserved centromere components and has a function in chromosome segregation. J. Cell Biol. 152: 349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winey, M., L. Goetsch, P. Baum and B. Byers, 1991. MPS1 and MPS2: novel yeast genes defining distinct steps of spindle pole body duplication. J. Cell Biol. 114: 745–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, A., V. Guacci and D. Koshland, 1996. a Pds1p is required for faithful execution of anaphase in the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 133: 85–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, A., V. Guacci and D. Koshland, 1996. b Pds1p, an inhibitor of anaphase in budding yeast, plays a critical role in the APC and checkpoint pathway(s). J. Cell Biol. 133: 99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]