Abstract

Much of the information about the function of D. melanogaster genes has come from P-element mutagenesis. The major drawback of the P element, however, is its strong bias for insertion into some genes (hotspots) and against insertion into others (coldspots). Within genes, 5′-UTRs are preferential targets. For the successful completion of the Drosophila Genome Disruption Project, the use of transposon vectors other than P will be necessary. We examined here the suitability of the Minos element from Drosophila hydei as a tool for Drosophila genomics. Previous work has shown that Minos, a member of the Tc1/mariner family of transposable elements, is active in diverse organisms and cultured cells; it produces stable integrants in the germ line of several insect species, in the mouse, and in human cells. We generated and analyzed 96 Minos integrations into the Drosophila genome and devised an efficient “jump-starting” scheme for production of single insertions. The ratio of insertions into genes vs. intergenic DNA is consistent with a random distribution. Within genes, there is a statistically significant preference for insertion into introns rather than into exons. About 30% of all insertions were in introns and ∼55% of insertions were into or next to genes that have so far not been hit by the P element. The insertion sites exhibit, in contrast to other transposons, little sequence requirement beyond the TA dinucleotide insertion target. We further demonstrate that induced remobilization of Minos insertions can delete nearby sequences. Our results suggest that Minos is a useful tool complementing the P element for insertional mutagenesis and genomic analysis in Drosophila.

ONE of the main goals of modern genetics is to link the many thousands of genes identified through the sequencing of whole genomes of model organisms to gene function. The most powerful technique for this purpose so far has been transgenesis with mobile elements. This technique is a means to disrupt, overexpress, or misexpress single genes to identify expression patterns and also to characterize genetic pathways and their interactions. One of the main advantages of insertional mutagenesis over the classical method of chemical mutagenesis is the ease with which the targeted gene can be identified, since it carries an inserted tag.

The P element was the first mobile element that enabled germ-line transformation of an insect species (Rubin and Spradling 1982). Since then, thousands of single P-element insertions causing lethality, semilethality, sterility, semisterility, and visible phenotypes have been created and analyzed in Drosophila (Cooley et al. 1988; Bier et al. 1989; Gaul et al. 1992; Karpen and Spradling 1992; Chang et al. 1993; Törok et al. 1993; Spradling et al. 1995, 1999; Rorth 1996). Furthermore, P-element-based enhancer and gene-trapping strategies (O'Kane and Gehring 1987; Bellen et al. 1989, 2004; Wilson et al. 1989; Brand and Perrimon 1993; Lukacsovich et al. 2001; Morin et al. 2001; Bourbon et al. 2002) have underlined the value of transposon mutagenesis for genome-wide functional analysis.

No other insect species were transformed for 13 years after the germ-line transformation of Drosophila, mainly because efforts were based on the P-element vector, which was subsequently found to be inactive in non-drosophilids (Handler et al. 1993). It was in 1995 when Minos, an element isolated from Drosophila hydei and belonging to the Tc1/mariner superfamily, was found to transform the medfly Ceratitis capitata (Loukeris et al. 1995b), an insect of great economical importance. This was the first report of a transposable element able to transform a species belonging to a genus other than that of the original host of the element. Since then, several insect species have been transformed by this and other mobile elements, some of which are active in organisms very phylogenetically distant (for review see Handler 2001). Interestingly, at least some members of the Tc1/mariner superfamily of transposable elements do not require any host-specific factors for transposition, since purified transposase is sufficient to catalyze in vitro transposition (Lampe et al. 1996; Vos et al. 1996). This property makes them potentially active in all organisms.

Despite the current existence of a diverse arsenal of transposable elements that can be used for the transformation of different species, certain features, such as efficiency of transposition and preference for integration into certain euchromatic regions, have to be considered for selection of the most appropriate transposon for functional genomic analysis. For example, although the mariner element is active in a broad spectrum of species, ranging from microorganisms (Gueiros-Filho and Beverley 1997) to human cells (Fadool et al. 1998; Sherman et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 1998), its transposition efficiency in Drosophila species is very low in comparison to other mobile elements with a more restricted spectrum, such as P and hobo (Garza et al. 1991; Lidholm et al. 1993; Lohe and Hartl 1996). Furthermore, different elements show distinctive intragenic preferences for integration. The P element inserts preferentially into the 5′-UTRs of genes in Drosophila (Spradling et al. 1995), while Sleeping Beauty has a preference for introns in human cells (Vigdal et al. 2002). The genomic insertional bias of the P element is such that integration preference is strong for some genes (hotspots), very low for the majority of genes (coldspots), and intermediate for a third group of loci (warmspots). This bias makes the mutagenesis of the entire Drosophila genome by the P element alone problematic. Therefore, the piggyBac element, which does not exhibit the same bias (Hacker et al. 2003), has recently been employed for the Drosophila gene disruption project and is greatly advancing its progress (Thibault et al. 2004).

In the context of functional genomic analysis we have further characterized the potential of the transposon Minos from D. hydei (Franz and Savakis 1991). Minos is a member of the Tc1/mariner family of transposable elements with 255-bp long terminal inverted repeats, which flank a single gene encoding transposase. The Minos transposase has been shown to catalyze, in most cases, precise excision and integration of the element without involvement of flanking DNA (Loukeris et al. 1995a; Arca et al. 1997). Most excision events either are precise (i.e., the original, preinsertion sequence is restored) or leave behind a characteristic 6-bp footprint, consisting of four terminal nucleotides of the Minos element followed by the duplicated TA, which is generated by the element upon insertion; complex events involving partial loss of the element are rare (Arca et al. 1997). The Minos element is active in insect and mammalian cells in culture and leads to stable insertions into germ-line chromosomes of embryos of several insect species (Loukeris et al. 1995a,b; Catteruccia et al. 2000a,b; Klinakis et al. 2000a; Shimizu et al. 2000; Pavlopoulos et al. 2004) and of ascidians (Sasakura et al. 2003). It is also functional in somatic and germ cells of mice (Zagoraiou et al. 2001; Drabek et al. 2003). The wide range of host organisms that permit transposition of this element and the fact that transposition produces stable transformants with high efficiency (Kapetanaki et al. 2002), allowing genome-wide mutagenesis in mammalian cells (Klinakis et al. 2000b), suggests that it is a versatile tool for functional genomic analysis.

In this work, the ability of Minos transposons to insert into Drosophila melanogaster genes that have not been mutagenized by the P element is demonstrated, as is a preference of Minos to target introns. In contrast to other elements of the same family, Minos does not seem to have a strong preference for DNA sequences with certain primary motifs and its preferred insertion sites appear to have predicted physical properties that differ from those of other members of the Tc1/mariner superfamily. We also demonstrate the ability of Minos to produce deletions at the sites of integration upon remobilization in the germ line. In addition, a “jump-starting” scheme, efficiently producing reinsertions from the X chromosome to the autosomes, has been devised. We conclude that Minos-based mutagenesis has the properties required to approach saturation of the Drosophila genome with intragenic insertions useful for functional analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructions:

To generate pMiPR1, two annealed oligonucleotides containing KpnI, SfiI, BglII, XbaI, StuI, EcoRV, SacI, and SspI restriction sites were cloned between the HindIII and XmaI sites of vector pHSS6 (Seifert et al. 1986), resulting in pHSSK. The left Minos inverted repeat together with the 5′-UTR of Minos transposase and ∼100 bp of flanking DNA from a Minos insertion in D. hydei were cloned into pHSSK as a ClaI-KpnI fragment from pMiLRtetR (Klinakis et al. 2000a), resulting in pMiLori. Two other fragments of pMiLRtetR, an EcoRI-HindIII (blunted) fragment containing a tetracycline resistance gene and a SacII-BstNI (blunted) fragment containing the right Minos inverted repeat, with ∼50 bp from D. hydei and 59 bp of the Minos transposase 3′-UTR, were cloned in the StuI and SspI sites of pMiLori, respectively, resulting in pMiLRoriT. The enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene flanked by the 3xP3 promoter and the SV40 polyadenylation signal was taken as an EcoRI-FseI (blunted) fragment from plasmid pSL-3xP3-EGFP, which was kindly provided by E. Wimmer (Horn et al. 2000), cloned into EcoRI-SmaI-digested pBlueScript KSII+ (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and then recloned as an XbaI-XhoI fragment into pMiLRtetR, resulting in pMi3xP3-EGFP. An EcoRI-NotI fragment from pMi3xP3-EGFP, containing the eye-specific 3xP3-EGFP marker, was cloned into pMiLRoriT, resulting in transposon donor plasmid pMiPR1.

pMiET1 is based on transposon donor pMiPR1. The Gal4 gene, driven by the hsp70 minimal promoter and followed downstream by the hsp70 terminator, was amplified with Vent polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) from vector pGATN (Brand and Perrimon 1993). The primers contained an EcoRI site each, which were used to clone the PCR fragment into the unique EcoRI site of vector pMiPR1. Plasmid pPhsILMiT is a derivative of P-element vector pCaSper4 (Thummel and Pirrotta 1992), carrying in its unique NotI site a 2.3-kb NotI fragment from pHSS6hsILMi20 (Klinakis et al. 2000a), containing an intronless Minos transposase gene under control of the hsp70 promoter.

Germ-line transformation and transposase mRNA synthesis:

Germ-line transformation was performed by micro-injection of plasmid DNA or a mixture of plasmid DNA and RNA into D. melanogaster preblastoderm embryos of strain yw67c23, as described (Rubin and Spradling 1982). Embryos were co-injected with 400 μg/ml of transposon donor and either 100 μg/ml of helper plasmid pHSS6hsMi2 (Loukeris et al. 1995a,b) or 100 μg/ml of Minos transposase mRNA, produced from vector pBS(SK)MimRNA (Pavlopoulos et al. 2004), using the message machine T7 kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), according to the manufacturer's instructions. G0 males and females were individually backcrossed with four female or male flies, respectively. The G1 progeny from these crosses were screened for green fluorescence of the eyes. Positive individuals were used to establish transgenic lines.

For the production of novel single insertions in flies, we used a so-called “jump-start” scheme (Cooley et al. 1988). We established a line producing Minos transposase from a balancer chromosome by co-injecting D. melanogaster embryos carrying the CyO balancer with helper plasmid Δ2-3 (Laski et al. 1986) and P-element-based plasmid pPhsILMiT. G1 progeny that carried both the CyO balancer and the white gene were crossed individually to yw flies. Six lines that cotransmitted the balancer and the white marker gene were established.

Plasmid rescue:

Purification of genomic DNA was after Holmes and Bonner (1973) and plasmid rescue was according to Pirrotta (1986). Genomic DNA was digested with BamHI, XbaI, or double digested with XbaI and SpeI, diluted, and ligated. DH5α competent cells were transformed with the ligation products and plated onto Luria broth plates with kanamycin (25 μg/ml). Sanger sequencing was performed with primer IMio2 (Klinakis et al. 2000a).

Computational analysis:

Analysis of the physical properties of Minos insertion sites was performed with the software by Liao et al. (2000). Flanking the TA insertion sites on either side, 50 bp each were aligned for 80 insertions and average values for GC content, DNA bendability, A-philicity, B-DNA twist, and protein-induced deformability were calculated. The values were predicted as previously described (Brukner et al. 1995; Gorin et al. 1995; Ivanov and Minchenkova 1995; Olson et al. 1998). H-bond view analysis was performed as previously described (Liao et al. 2000). The profiles were compared with those of 80 sequences randomly taken from the D. melanogaster genome, each centered around a TA dinucleotide. All calculations were performed using a 3-bp sliding window. For the determination of the consensus sequence of Minos insertions, 10 bp upstream and downstream of the TA insertion site were analyzed with the program SeqLogo (Schneider and Stephens 1990).

Production and analysis of Minos excision events:

For the generation of excision events in the germ line of flies with single Minos insertions, flies homozygous for a MiET1 transposon insertion on the second chromosome were crossed with flies carrying helper chromosome PhsILMiT (cross 1). Two days after setting up the crosses, the flies were transferred to new vials and the old vials were heat-shocked daily for 1 hr in a 37° water bath until pupariation. Adults that expressed both the EGFP marker of the transposon and the white marker of the helper chromosome were crossed individually with flies carrying balancer chromosome SM6 over the marker Glaze (cross 2). Progeny with transposon excisions were identified as carrying the SM6 balancer but lacking the EGFP and white markers. One such fly was chosen per vial and crossed individually with flies carrying a chromosome 2 balancer over deficiencies covering the region of the initial transposon insertion (cross 3). DNA was extracted from flies that carried the chromosome with the excision event over the deficiency-carrying chromosome and used for PCR amplification of a 2-kb fragment centered around the TA insertion site. We analyzed excision events from introns of three different genes, CG4114 or expanded (AE003589.3, 132323 nt), CG5423 or robo3 (AE003586.3, 55570 nt), and CG30497 (AE003840.3, 239589 nt). The deficiency-carrying flies were from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. Df(2L)al, ds[al]/In(2L)Cy was used for excision events at CG4114, Df(2L)ast2/SM1 for excision events at CG5423, and Df(2R)NCX13/CyO for excision events at CG30497. The following three pairs of primers were used for the analytical PCR reactions:

Ex1: 5′ CGCTTGACAAACACACGCCC 3′ and Ex2: 5′ CGATCGGACCGATCGGAGG 3′

Robo1: 5′ GCGTGCAGGAGCTCTTGCC 3′ and Robo2: 5′ AAGTGAGCAGTGGCAGGAAAG 3′

30b1: 5′ TAAAGCCCGTGTGCCAAATGC 3′ and 30b2: 5′ CCATAGCCATACCCATACCAAG 3′.

PCR products that appeared larger or smaller than the expected 2 kb were cloned into vectors pBlueScript KSII+ (Stratagene) or PCRII (Invitrogen, San Diego) and sequenced.

RESULTS

Generation of Minos insertions in Drosophila:

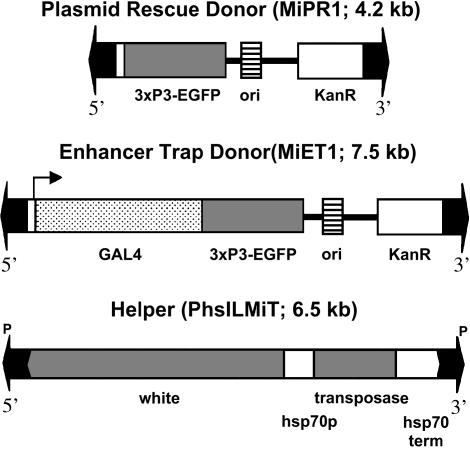

Fifty-six Drosophila lines carrying Minos insertions were generated in three series of preblastoderm embryo injections. In experiment 1, donor plasmid pMiET1, carrying an enhancer trap transposon, was co-injected with Minos transposase mRNA; in experiment 2, donor plasmid pMiPR1 was used instead of pMiET1; and in experiment 3, donor pMiPR1 was co-injected with helper plasmid pHSS6hsMi2 (Loukeris et al. 1995a,b) (Figure 1). Transformation efficiencies ranged from 30% (with DNA helper) to 50% (with mRNA). Transformed flies were identified by eye-specific EGFP fluorescence in adults. The number of insertions per transformed line ranged in all experiments between one and four, as determined by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Twenty-four additional lines, each carrying single autosomal insertions of transposon MiET1, were generated by the remobilization scheme described below.

Figure 1.

Minos donor and helper constructs. Both donors contain the 3xPax6/EGFP dominant marker (Berghammer et al. 1999) and allow plasmid rescue of insertions. The helper construct expresses Minos transposase under heat-shock control and is based on pCaSper. Only the transposon regions are shown.

Mobilization of chromosomal insertions using endogenous transposase:

To establish an efficient source of transposase for transposon mobilization, six different lines carrying P-element-based helper PhsILMiT, encoding Minos transposase under control of a hsp70 promoter (Figure 1) on a balancer chromosome (hereafter called “helper chromosome”), were established. The helper chromosomes were tested for their ability to mediate remobilization of a single insertion of transposon MiPR1 from the X chromosome (X:8F3, hereafter called “transposon chromosome”) to the autosomes. In a first experiment, “jump-start” males carrying both helper and transposon chromosomes were heat-shocked once during larval development. The highest remobilization efficiency observed was 24% (with line MiT2.4). Flies from this line were then used to define optimal conditions for mobilization of a single insertion of transposon MiET1 (located at 17D3) from the X chromosome to the autosomes. The jump-start males were heat-shocked daily for 1 hr during the larval and pupal stages. Transposition efficiency in this experiment was 81%. No remobilization was detected when the jump-start males were kept continuously at 25° or 30°. Twenty-four of these reinsertions of MiET1 into autosomes were recovered and sequenced. The transposons MiET1 and MiPR1 used in these experiments allow recovery of the genomic DNA flanking the insertions on one side by plasmid rescue (Perucho et al. 1980). This enabled us to identify the exact insertion point of 92 different Minos insertions.

Analysis of Minos insertion sites:

BLAST (Altschul et al. 1990) analysis was used to place the 92 insertions recovered plus 4 previously published insertions (Loukeris et al. 1995a) on the Drosophila genome, according to release 3 of the D. melanogaster database (Celniker et al. 2002). Seven insertions were in repetitive regions. One of these is found only on 3L while the others occur on more than one chromosomal arm. These were excluded from analysis of chromosomal distribution.

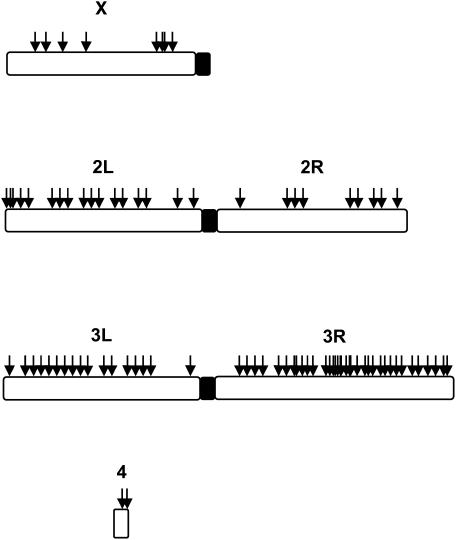

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the remaining Minos insertions over the chromosomal arms. A clear preference for 3R is apparent. Thirty-nine percent of Minos insertions lie on 3R, which contains only 24% of the euchromatin. The distribution of TA dinucleotides, which are a prerequisite for Minos insertion, does not explain this preference (Table 1). Chi-square analysis of the distribution of the 82 Minos insertions on the chromosomal arms vs. the distribution of TAs shows a significant bias (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Distribution of Minos insertions over the Drosophila genome. The number of insertions on the X chromosome is an underestimate, since 24 integration events were produced by mobilization of an X-linked insertion into the autosomes.

TABLE 1.

Observed and expected number of Minos insertions into the autosomes of D. melanogaster assuming all TA insertion targets are equally accessible

| Chromosome arm

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2L | 2R | 3L | 3R | 4 | Total | |

| TA targets | 1,405,300 | 1,226,348 | 1,476,758 | 1,706,228 | 112,619 | 5,927,253 |

| Observed insertions | 18 | 9a | 18 | 35a | 2 | 82 |

| Expected insertions | 19 | 17 | 20 | 24 | 2 | 82 |

χ2-test, P ≤ 0.05.

Of the 96 characterized insertions, 58 were found to be within or close to (2 kb upstream or downstream) known or predicted genes (Table 2). A total of 30 insertions were in introns, 7 in exons (one of which was in a nested gene), 2 in 5′-UTRs, 2 in 3′-UTRs, and 1 in an intron/3′-UTR of an alternatively spliced gene. Sixteen insertions were located <2 kb from the closest gene. A total of 56 different genes were targeted by these insertions. Two genes, the Dystrophin gene and the predicted gene CG31000, were targeted twice. Additionally, one insertion occurred in the exon of a gene that lies nested within the intron of a second gene (Table 2). Thirteen of the insertions (∼22%) occurred in genes that have not been hit either by the P element or by piggyBac (Bellen et al. 2004; Thibault et al. 2004).

TABLE 2.

Minos insertions into Drosophila genes

| Genes with Minos hits | Position in gene | GenBank entry site (nucleotide position) | Cytogenetic site | Function | piggy Bac hits | P-element hits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG5613 | Intron | AE003505.3: 190433 | X: 16A1-4 | — | + | − |

| CG32549 | Intron | AE003508.3: 254243 | X: 17A11 | 5′ nucleotidase activity | + | + |

| CG32498 | Intron | AE003426.2: 366742 | X: 3D1 | cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase activity | − | − |

| CG4114, Ex | Intron | AE003589.3: 132323 | 2L: 21C5-6 | Regulator of cell proliferation | − | + |

| CG5156 | 60 bp from 3′ end | AE003587.3: 309289 | 2L: 21F3 | — | + | − |

| CG5423, Robo-3 | Intron | AE003586.3: 55570 | 2L: 21F3-4 | Axon guidance receptor | + | − |

| CG17648 | 670 bp from 3′ end | AE003585.3: 212158 | 2L: 22B2 | — | + | − |

| CG16987, Alp23B | Intron | AE003583.3: 271193 | 2L: 23A3 | Metallopeptidase activity | − | + |

| CG31646 | Intron | AE003610.3: 217269 | 2L: 25F3 | Cell adhesion | + | + |

| CG11147 | Intron | AE003611.3: 43102 | 2L: 25F4 | ABC transporter | + | − |

| CG18340, Ucp4B | 110 bp from 3′ end | AE003612.2: 14760 | 2L: 26A5 | Mitochondrial transporter | + | − |

| CG7105 | Intron | AE003619.3: 47680 | 2L: 28D3-4 | Proctolin, neuropeptide hormone | + | − |

| CG8049, Btk29A | Intron | AE003620.3: 156821 | 2L: 29A1-3 | Tyrosine kinase | + | + |

| CG31719, RluA-1 | 500 bp from 5′ end | AE003628.2: 236953 | 2L: 31E6 | Deaminase activity | + | + |

| CG7294 | 160 bp from 5′ end | AE003629.2: 182506 | 2L: 32A2 | — | − | − |

| CG7147, Kuz | Intron | AE003640.3: 216217 | 2L: 34C4-6 | Metalloendopeptidase activity | + | + |

| CG4952, Dac | 400 bp from 3′ end | AE003651.2: 104793 | 2L: 36A1 | RNA pol II transcription factor | − | − |

| CG12508 | 590 bp from 3′end | AE003664.3: 237127 | 2L: 38B1 | — | + | − |

| CG30497 | Intron | AE003840.3: 239589 | 2R: 43E13 | — | + | + |

| CG12367 | 300 bp from 5′ end | AE003823.3: 149017 | 2R: 48E12 | — | + | + |

| CG17019 | 3′-UTR | AE003820.3: 115367 | 2R: 49E1-3 | Ubiquitin-protein ligase activity | + | − |

| CG6520 | 1300 bp from 5′ end | AE003803.3: 193893 | 2R: 54C5-6 | — | + | − |

| CG7020, DIP2 | Intron | AE003467.3: 238181 | 3L: 61B3 | — | + | + |

| CG16991, Tsp66A | Exon | AE003559.3: 258506 | 3L: 66A2 | Component integral to membrane | − | − |

| CG6718 | 3′-UTR | AE003550.3: 97483 | 3L: 67C9 | Ca-independent phospholipase A2 | + | + |

| CG7628 | Intron | AE003546.3: 242734 | 3L: 68A4-5 | Transporter activity | − | + |

| CG32146, dlp | Intron | AE003533.3: 35328 | 3L: 70E5-7 | Wnt receptor signaling pathway | + | + |

| CG13474 | Exon | AE003533.3:64573 | 3L: 70F1 | — | − | − |

| CG6117, Pka-C3 | Intron | AE003529.3: 158146 | 3L: 72A3-5 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase | + | + |

| CG7571, Oatp74D | Exon | AE003523.3: 24407 | 3L: 74D1 | Organic anion transporter | − | − |

| CG5582 | Intron | AE003522.3: 35487 | 3L: 75A4 | Transmission of nerve impulse | − | − |

| CG32457 | 700 bp from 3′ end | AE003599.2: 196361 | 3L: 80C2 | — | + | − |

| CG31519 | 400 bp from 5′ end | AE003607.3: 82270 | 3R: 82A1 | Olfactory receptor | − | − |

| CG32490, Complexin | Intron/3′-UTR | AE003606.3: 32995 | 3R: 82A3 | Syntaxin binding | − | + |

| CG1028, AntP | Intron | AE003673.3: 142252 | 3R: 84A6 | Transcription factor | + | + |

| CG1988 | 220 bp from 5′ end | AE003673.3: 283960 | 3R: 84C1 | — | − | + |

| CG31410 | Intron | AE003685.3: 109798 | 3R: 85F8-9 | — | − | − |

| CG7091 | 5′-UTR | AE003698.3: 62152 | 3R: 87D8 | Inorganic phosphate sodium symporter | + | − |

| CG17907, Ace | Intron | AE003699.3: 68737 | 3R: 87E2-3 | Acetylcholinesterase | + | + |

| CG31150 | Exon | AE003710.2: 194610 | 3R: 89A5-6 | Lipoprotein aminoterminal region | + | − |

| CG17562 | 140 bp from 3′ end | AE003714.2: 48639 | 3R: 89D5 | Oxidoreductase activity | + | − |

| CG3937, cherio | Intron | AE003716.3: 69050 | 3R: 89E13 | Actin binding | + | + |

| CG31243, Cpo | Intron | AE003720.3: 74671 | 3R: 90D1-6 | RNA binding | + | + |

| CG18599 | 5′-UTR | AE003721.2: 107497 | 3R: 90F3 | Homeobox domain | − | − |

| CG7700 | Exon | AE003723.3: 59569 | 3R: 91B6-8 | SNAP receptor | − | + |

| CG31175, Dys | Intron | AE003726.3: 148326 | 3R: 92A6-7 | Cytoskeletal protein binding | + | − |

| CG31175, Dys | Intron | AE003726.3: 169013 | 3R: 92A6-7 | Cytoskeletal protein binding | + | − |

| CG5191 | 300 bp from 3′-end | AE003731.3: 49441 | 3R: 92F1-2 | Amidotransferase activity | + | − |

| CG5346 | Intron | AE003739.2: 102269 | 3R: 94A14 | — | + | + |

| CG13408 | 670 bp from 3′ end | AE003737.3: 128239 | 3R: 94A2 | — | − | − |

| CG4467 | Intron | AE003742.3: 124381 | 3R: 94E7-8 | Aminopeptidase activity | + | + |

| CG13624 | Intron | AE003748.3: 108349 | 3R: 96A3 | DNA binding | + | + |

| CR31382, tRNA Asp | Exon | AE003749.3: 204677 | 3R: 96B6 | tRNA Asp | − | − |

| CG31120 | Intron | AE003749.3: 204677 | 3R: 96B6 | Oxidoreductase activity | + | + |

| CG10001 | 1150 bp from 3′ end | AE003766.2: 166978 | 3R: 98E2 | Allatostatin receptor activity | − | − |

| CG31000 | Intron | AE003780.3: 91982 | 3R: 100F1 | Pre-mRNA splicing factor | + | + |

| CG31000 | Intron | AE003780.3: 151439 | 3R: 100F1 | Pre-mRNA splicing factor | + | + |

| CG31998 | Exon | AE003844.3: 44976 | 4: 102A1 | — | + | − |

The nucleotide sequences of the insertion sites are available upon request.

Interestingly, introns were hit five times more frequently than exons. Chi-square analysis indicates that the preference of Minos for introns vs. exons is nonrandom (P < 0.05). This is not explained by the distribution of TA dinucleotides, the potential sites of Minos insertion, since the total number of TAs in introns is only twice the number of TAs in exons (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Observed and expected number of Minos insertions into the TAs (potential sites of Minos insertions) of introns vs. exons

| Exons | Introns | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TA targets | 1,052,616 | 2,106,358 | 3,158,974 |

| Observed insertions | 6a | 30a | 36 |

| Expected insertions | 12 | 24 | 36 |

χ2-test, P ≤ 0.05.

No visible phenotypes, lethality, or semilethality were observed in 10 lines with single intronic insertions that were made homozygous, indicating that Minos insertions into introns are not likely to lead to a loss of function (data not shown).

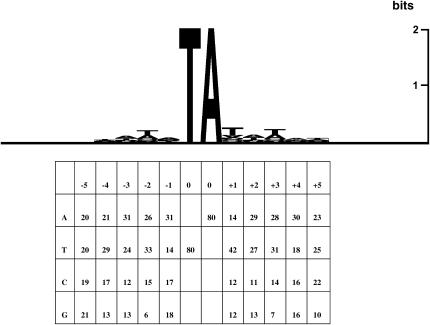

Lack of sequence bias at insertion sites:

An interplasmid transposition assay performed previously in insect cells failed to detect a sequence consensus at the insertion sites, beyond the actual TA target dinucleotide (Klinakis et al. 2000a). The sample of potential target sites in this assay was, however, rather limited, being restricted to a single 2-kb gene. As shown in Figure 3, analysis of the primary sequence of the D. melanogaster genomic integration reveals a very weak palindromic consensus around the actual insertion site. Interestingly, the corresponding sequence, ATATATAT, is also the consensus integration site for Sleeping Beauty, another transposon of the Tc1/mariner family; however, in the case of Sleeping Beauty, the consensus is considerably stronger (Vigdal et al. 2002).

Figure 3.

Sequence composition analysis of Minos insertion sites. (Top) Five nucleotides upstream and downstream of the insertions were aligned for 80 integrants and their informational content was plotted with the SeqLogo program (Schneider and Stephens 1990). (Bottom) Base distribution of the 80 insertion sites.

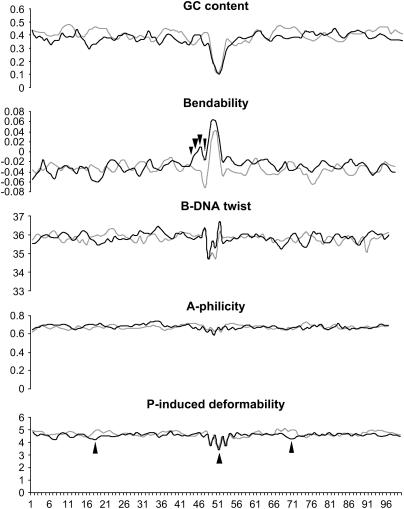

Physical properties of DNA at Minos insertions sites:

In addition to the primary sequence of the insertion site, structural properties of the target DNA are thought to determine the target preference of transposable elements (Craig 1997). We examined GC content and predicted bendability, B-DNA twist, A-philicity, and protein-induced deformability of 50 bp upstream and downstream of the Minos TA targets for 80 integration events. For comparison, 80 sequences of the same length and centered around a TA were taken randomly from the Drosophila genome (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Analysis of predicted physical properties of Minos insertion sites. One hundred nucleotides centered around each of the 80 Minos insertions were analyzed and averaged (solid lines). Eighty sequences, also centered around TAs, but randomly taken from the Drosophila genome, were coanalyzed (shaded lines). Arrowheads indicate nucleotide positions where the predicted values between the two groups are different according to a confidence level of >99% (Student's t-test). Bendability is the tendency of DNA to bend toward the major groove. B-DNA twist determines the tightness of the DNA coil. A-philicity is the tendency of the DNA double helix to form A-DNA. Protein-induced deformability describes the propensity of DNA to change conformation upon binding to a protein.

Positions in which the Minos flanking sequences differ significantly from the random sequences (as judged by Student's t-test with a significance threshold of 0.01) are indicated by arrowheads in Figure 4. It appears that Minos insertion sites differ significantly from the random sequences only in predicted bendability and P-induced deformability.

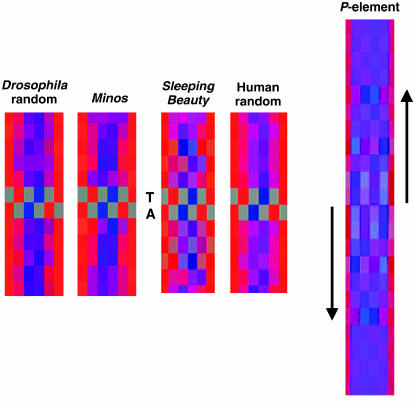

H-Bond view analysis color codes the respective positions of base pairs according to their hydrogen bonding potential and generates average color values for a sequence alignment (Liao et al. 2000). This analysis reveals a weak conservation of potential hydrogen bonding at positions −3 to +3 flanking the target TA, presumably corresponding to the weak palindrome at these positions. Compared to Sleeping Beauty and P, however, Minos shows a much less pronounced hydrogen bonding pattern in the sequences flanking the TA target (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hydrogen-bonding analysis of Minos insertion sites compared to Sleeping Beauty and P-element insertion sites. Program HbondView (Liao et al. 2000) was used to illustrate average hydrogen-bonding patterns of base pairs flanking the Minos insertion sites. Six positions for each base pair are color coded as potential hydrogen acceptor (red), donor (blue), or inert (gray). Sleeping Beauty and P graphs are from Liao et al. (2000) and Vigdal et al. (2002), respectively.

Deletion of flanking genomic sequences through Minos excision:

The preference of Minos for introns, with the fact that the homozygous intronic Minos insertions examined did not have any detectable phenotype, raised the question of whether Minos transposons can mutate a gene by deleting flanking exonic sequences after mobilization from an initial insertion in an intron. We tested this by mobilizing, in the germ line of heterozygotes, the MiET1 transposon from intronic insertions in genes CG5423 (robo3), CG4114 (expanded), and CG30497 (a gene with no matches in the databases). Each excision-carrying chromosome was then made heterozygous with a deficiency spanning the respective locus. Genomic DNA from these heterozygous flies was subjected to PCR analysis with oligonucleotides priming at a distance of ∼1000 bp on either side of the TA insertion site of Minos.

In 1 of 50 Minos excisions from the intron of gene robo3, the PCR product was 800 bp shorter than the expected 2000 bp. Sequence analysis showed a complex deletion/insertion event. A total of 800 bp of genomic DNA were deleted just adjacent to the TA insertion site, taking away almost the whole upstream exon, and 15 nucleotides of unknown origin were inserted instead. No transposon sequences were left behind.

Fifty excision events from the insertion in the expanded gene (ex, CG4114) were analyzed by PCR. The PCR product in all 50 cases had the expected size. Nevertheless, one of the excision chromosomes caused lethality over deletion Df(2L)al, ds[al]/In(2L)Cy. Certain mutations of the ex gene have been reported to cause lethality (Spradling et al. 1999). The initial insertion of Minos was 2 kbp upstream of the predicted ATG of expanded, and it is possible that a deletion, too small to be detected by our analysis, caused the lethality. Alternatively, the lethal mutation may have been the result of a “hit and run” event, where the excised element first reinserts into a nearby locus, from where it excises again, leaving behind its mutagenic footprint or a deletion.

In 2 of 89 excision events from orphan gene CG30497, the transposon was imprecisely excised, leaving behind 368 and 112 bp of the inverted repeat. In the latter case, 25 bp of genomic DNA were deleted adjacent to the TA insertion site. Furthermore, three PCR reactions from gene CG30497 excisions did not give any product, indicating that deletions covering at least one of the primer-annealing sites may have taken place. Lethality was also observed in one excision event from gene CG30497. Again, Southern blot analysis of heterozygotes of this event did not reveal a deletion at the site of the initial Minos insertion.

DISCUSSION

Transposon mutagenesis is an important tool in functional genomics. Mutagenesis of Drosophila with the P element has played a central role in elucidating the function and regulation of many genes. Constructs based on the P element are used to “trap” genes and enhancers, to produce loss-of-function mutations, to overexpress and ectopically express genes, and to study genetic interactions. Such studies have helped to unravel basic conserved genetic pathways, some of which are involved in human diseases and aging (for review see O'Kane 2003). It has been estimated that 77% of human genes implicated in specific diseases have one or more Drosophila homologs with considerable sequence similarity (Reiter et al. 2001).

An extensive body of data on the genomic distribution of P-element insertions accumulated over 20 years has revealed a high insertion preference for certain euchromatic areas, the so-called hotspots (Spradling et al. 1999). Consequently, so far only a fraction of all predicted genes in the Drosophila genome have been targeted by P, indicating that the P element alone is not sufficient for saturating mutational analysis of the Drosophila genome. Therefore, other mobile elements that also insert efficiently into the Drosophila genome and at the same time show a different insertional spectrum or even no insertion site preference at all are desirable as complementing mutagenesis tools.

We demonstrate here that the Tc1/mariner-like transposable element Minos is an efficient tool for generating insertions into the Drosophila genome, that Minos insertions show little sequence preference beyond the strictly required target dinucleotide TA, and that there is a significant bias for insertion into introns vs. exons. Furthermore, we show that while Minos inserts preferentially into introns, where it does not appear to interfere with expression of the target gene, it occasionally causes deletions of nearby exonic sequences upon subsequent excision. This property distinguishes Minos from piggyBac, which does not cause deletions upon excision (Horn et al. 2003).

Efficiency of transposition:

Minos insertions were generated either through preblastoderm embryo injections or through remobilization of a Minos transposon from an X-linked insertion. Transposase expression in remobilization experiments was regulated by heat shock. Transformation efficiency varied between 30 and 50%, with higher rates when the transposon was co-injected with transposase mRNA. Remobilization efficiency through expression of a chromosomally encoded transposase was at least 80%. Remobilization is thus more appropriate for genomic analysis, since it is easier to perform on a large scale and produces single insertions. One of the transposons used in this study (MiET1) was designed to function as a GAL4-based enhancer trap. Preliminary analysis of MiET1 insertions indicated that ∼20% of insertions can be classified as bona fide enhancer traps (data not shown).

Characterization of Minos insertions:

Alignment of 80 Minos insertions, centered around the target TA dinucleotide, revealed a weakly conserved palindromic motif, the sequence ATATATAT. Interestingly, the same consensus, although much more strongly conserved, was found for insertions of Sleeping Beauty, another member of the Tc1/mariner superfamily of mobile elements, into the mouse genome. A similar consensus (CAYATATRTY) has been reported for Tc1 in Caenorhabditis elegans (Korswagen et al. 1996). Thus, these elements share a similar target site, albeit with a different degree of conservation. Compared to Sleeping Beauty and Tc1, Minos insertions seem to depend much less, if at all, on sequences beyond the TA insertion dinucleotide. This is strongly supported by H-bond view analysis, which reveals a very low degree of symmetric hydrogen bonding potential around the target TA. The P element, Sleeping Beauty, and Tc1, on the other hand, exhibit extensive conservation and strong symmetry in hydrogen-bonding potential within the DNA flanking their target sites (Liao et al. 2000; Vigdal et al. 2002).

High bendability (Figure 4) seems to be the DNA property that mainly distinguishes Minos target sites from randomly chosen TA-centered sequences. Additionally, the site of insertion has a significantly lower predicted protein-induced deformability than in the random sequences, a property not shared by other Tc1/mariner family members (Vigdal et al. 2002).

Analysis of genomic position of the retrieved Minos insertions reveals no apparent preference for insertions into genes. There is, however, a preference of Minos for introns vs. exons, which is not sufficiently explained by the respective frequency of TA dinucleotides in introns and exons (P = 0.034). However, the relative overall A/T richness may be a determinant of the integration site and may explain the observed bias. The sequences immediately flanking Minos insertions are A/T rich, and it is possible that such sites may be better targets either on the level of primary sequence or through their structural properties. Introns would thus be preferential targets since their A/T content, over all chromosomes, is ∼10 percentage points above that of the exons.

A preference for insertions into introns has been reported for piggyBac in Drosophila (Hacker et al. 2003) and for the Tc1-like element Sleeping Beauty in mammalian cells (Vigdal et al. 2002). This property sets these elements apart from the yeast Ty1 and Ty2 elements and the P element, which preferably insert into 5′-UTRs of genes (Craig 1997).

Our analysis revealed no obvious hotspot for Minos integration. Two genes, which contain exceptionally large introns, were hit twice. A more thorough investigation of genome-wide insertional bias will require analysis of a much greater number of insertions. However, it can be inferred that Minos does not share the same bias of insertion as the P element; >55% of the genes with a Minos hit (30/56) have no known P-element insertions. Furthermore, the observation that ∼20% of the genes hit by Minos have not been hit by either P or piggyBac suggests that Minos will be invaluable in achieving saturation mutagenesis in Drosophila.

The Minos system has the key properties required of a tool for genome-wide insertional screens in Drosophila. First, high-efficiency germ-line transposition of a Minos insertion is achieved by expressing transposase in trans. Second, sequence conservation at the insertion site is considerably weaker compared to the P element. Third, since insertions in introns are more abundant than insertions in exons, Minos will be useful for developing true gene-trap constructs for genome-wide disruption screens. Additionally, Minos can be more useful as a mutagen compared to piggyBac, since new mutant alleles can be generated through imprecise excision of the element. One drawback of imprecise excision, however, is the possibility of “hit-and-run” events, which can complicate genetic analysis, as has been observed with P. All these features are, due to the broad host range of Minos, also potentially available for the genetic manipulation of many other species. We conclude that Minos can be instrumental for completion of the effort to introduce useful insertions into all known genes of D. melanogaster.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Livadaras for excellent technical assistance with embryo injections, G. Liao for supplying us with the H-Bond View and DNA structure analysis software, and J. Lagnel for computational assistance. E. Wimmer is acknowledged for kindly supplying us with the pSL-3xP3-EGFP construct and Gareth Lycett and Alexandros Kiupakis for critical comments. Plasmid pBS(SK)MImRNA for the production of Minos transposase mRNA was kindly provided by A. Pavlopoulos. A.M. was partly supported by the Operational Program “Competitiveness” (EPAN) of the General Secretariat for Research and Technology (Greece).

References

- Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers and D. J. Lipman, 1990. BASIC local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arca, B., S. Zabalou, T. G. Loukeris and C. Savakis, 1997. Mobilization of a Minos transposon in Drosophila melanogaster chromosomes and chromatid repair by heteroduplex formation. Genetics 145: 267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen, H. J., C. J. O'Kane, C. Wilson, U. Grossniklaus, R. K. Pearson et al., 1989. P-element mediated enhancer detection: a versatile method to study development in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 3: 1288–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellen, H. J., R. W. Levis, G. Liao, Y. He, J. W. Carlson et al., 2004. The BDGP gene disruption project: single transposon insertions associated with 40% of Drosophila genes. Genetics 167: 761–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghammer, A. J., M. Klingler and E. A. Wimmer, 1999. A universal marker for transgenic insects. Nature 402: 370–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier, E., H. Vaessin, S. Shepherd, K. Lee, K. McCall et al., 1989. Searching for pattern and mutation in the Drosophila genome with a P-lacZ vector. Genes Dev. 3: 1273–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourbon, H. M., G. Gonzy-Treboul, F. Peronnet, M. Alin, C. Ardourel et al., 2002. A P-insertion screen identifying novel X-linked essential genes in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 110: 71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A. H., and N. Perrimon, 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brukner, I., R. Sanchez, D. Suck and S. Pongor, 1995. Sequence-dependent bending propensity of DNA as revealed by DNAase I: parameters for trinucleotides. EMBO J. 14: 1812–1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catteruccia, F., T. Nolan, C. Blass, H. M. Muller, A. Crisanti et al., 2000. a Toward Anopheles transformation: Minos element activity in anopheline cells and embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 2157–2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catteruccia, F., T. Nolan, T. G. Loukeris, C. Blass, C. Savakis et al., 2000. b Stable germline transformation of the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi. Nature 405: 959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celniker, S. E., D. A. Wheeler, B. Kronmiller, J. W. Carlson, A. Halpern et al., 2002. Finishing a whole genome shotgun: Release 3 of the Drosophila melanogaster euchromatic genome sequence. Genome Biol. 3: research0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chang, Z., B. D. Price, S. Bockheim, M. J. Boedigheimer, R. Smith et al., 1993. Molecular and genetic characterization of the Drosophila tartan gene. Dev. Biol. 160: 315–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, L., R. Kelley and A. C. Spradling, 1988. Insertional mutagenesis of the Drosophila genome with single P elements. Science 239: 1121–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig, N. L., 1997. Target site selection in transposition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 66: 437–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabek, D., L. Zagoraiou, T. de Wit, A. Langeveld, C. Roumpaki et al., 2003. Transposition of the Drosophila hydei Minos transposon in the mouse germ line. Genomics 81: 108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadool, J. M., D. L. Hartl and J. E. Dowling, 1998. Transposition of the mariner element from Drosophila mauritiana in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 5182–5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz, G., and C. Savakis, 1991. Minos, a new transposable element from Drosophila hydei, is a member of the TC1-like family of transposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 19: 6646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza, D., M. Medhora, A. Koga and D. L. Hartl, 1991. Introduction of the transposable element mariner into the germline of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 128: 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaul, U., G. Mardon and G. M. Rubin, 1992. A putative Ras GTPase activating protein acts as a negative regulator of signaling by the Sevenless receptor tyrosine kinase. Cell 68: 1007–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorin, A. A., V. B. Zhurkin and W. K. Olson, 1995. B-DNA twisting correlates with base-pair morphology. J. Mol. Biol. 247: 34–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueiros-Filho, F. J., and S. M. Beverley, 1997. Trans-kingdom transposition of the Drosophila element mariner within the protozoan Leishmania. Science 276: 1716–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, U., S. Nystedt, M. P. Barmchi, C. Horn and A. Wimmer, 2003. piggyBac-based insertional mutagenesis in the presence of stably integrated P elements in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 7720–7725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler, A. M., 2001. A current perspective on insect gene transformation. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 31: 111–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handler, A. M., S. P. Gomez and D. A. O'Brochta, 1993. A functional analysis of the P-element gene-transfer vector in insects. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 22: 373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, D. S., and J. Bonner, 1973. Preparation, molecular weight, base composition, and secondary structure of giant nuclear ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 12: 2330–2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn, C., B. Jaunich and E. A. Wimmer, 2000. Highly sensitive, fluorescent transformation marker for Drosophila transgenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 210: 623–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn, C., N. Offen, S. Nystedt, U. Hacker and E. A. Wimmer, 2003. piggyBac-based insertional mutagenesis and enhancer detection as a tool for functional insect genomics. Genetics 163: 647–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, V. I., and L. E. Minchenkova, 1995. The A-form of DNA: in search of the biological role. Mol. Biol. 28: 1258–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanaki, M. G., T. G. Loukeris, I. Livadaras and C. Savakis, 2002. High frequencies of Minos transposon mobilization are obtained in insects by using in vitro synthesized mRNA as a source of transposase. Nucleic Acids Res. 30: 3333–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpen, G. H., and A. C. Spradling, 1992. Analysis of subtelomeric heterochromatin in a Drosophila minichromosome by single P element insertional mutagenesis. Genetics 132: 737–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinakis, A. G., T. G. Loukeris, A. Pavlopoulos and C. Savakis, 2000. a Mobility assays confirm the broad host range activity of the Minos transposable element and validate new transformation tools. Insect Mol. Biol. 9: 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinakis, A. G., L. Zagoraiou, D. K. Vassilatis and C. Savakis, 2000. b Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis in human cells by the Drosophila mobile element Minos. EMBO Rep. 1: 416–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korswagen, H. C., R. M. Durbin, M. T. Smits and R. H. A. Plasterk, 1996. Transposon Tc1-derived, sequence-tagged sites in Caenorhabditis elegans as markers for gene mapping. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 14680–14685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe, D. J., M. E. A. Churchill and H. M. Robertson, 1996. A purified mariner transposase is sufficient to mediate transposition in vitro. EMBO J. 15: 5470–5479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laski, F. A., D. C. Rio and G. M. Rubin, 1986. Tissue specificity of Drosophila P element transposition is regulated at the level of mRNA splicing. Cell 44: 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao, G. C., E. J. Rehm and G. M. Rubin, 2000. Insertion site preferences of the P transposable element in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 3347–3351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidholm, D.-A., A. R. Lohe and D. L. Hartl, 1993. The transposable element mariner mediates germline transformation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 134: 859–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohe, A. R., and D. L. Hartl, 1996. Reduced germline mobility of a mariner vector containing exogenous DNA: Effect of size or site? Genetics 143: 1299–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukeris, T. G., B. Arca, I. Livadaras, G. Dialektaki and C. Savakis, 1995. a Introduction of the transposable element Minos into the germ line of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 9485–9489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukeris, T. G., I. Livadaras, B. Arca, S. Zabalou and C. Savakis, 1995. b Gene transfer into the medfly, Ceratitis capitata, with a Drosophila hydei transposable element. Science 170: 2002–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacsovich, T., Z. Aztalos, W. Awano, K. Baba, S. Kondo et al., 2001. Dual-tagging gene trap of novel genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 157: 727–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin, X., R. Daneman, M. Zavortink and W. Chia, 2001. A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenus loci in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 15050–15055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kane, C. J., 2003. Modelling human diseases in Drosophila and Caenorhabditis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 14: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kane, C. J., and W. J. Gehring, 1987. Detection in situ of genomic regulatory elements in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84: 9123–9127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson, W. K., A. A. Gorin, X. J. Lu, L. M. Hock and V. B. Zhurkin, 1998. DNA sequence-dependent deformability deduced from protein-DNA crystal complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95: 11163–11168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlopoulos, A., A. J. Berghammer, M. Averof and M. Klingler, 2004. Efficient transformation of the beetle Tribolium castaneum using the Minos transposable element: quantitative and qualitative analysis of genomic integration events. Genetics 167: 737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perucho, M., D. Hanahan, L. Lipsich and M. Wigler, 1980. Isolation of the chicken thymidine kinase gene by plasmid rescue. Nature 285: 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirrotta, V., 1986. Cloning Drosophila genes, pp. 83–110 in Drosophila: A Practical Approach, edited by D. B. Roberts. IRL Press, Oxford.

- Reiter, L. T., L. Potocki, S. Chien, M. Gribskov and E. Bier, 2001. A systematic analysis of human disease-associated gene sequences in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Res. 11: 1114–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth, P., 1996. A modular misexpression screen in Drosophila detecting tissue-specific phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 12418–12422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, G. M., and A. C. Spradling, 1982. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science 218: 348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasakura, Y., S. Awazu, S. Chiba and N. Satoh, 2003. Germ-line transgenesis of the Tc1/mariner superfamily transposon Minos in Ciona intestinalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 7726–7730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, T. D., and R. M. Stephens, 1990. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 6097–6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, H. S., E. Y. Chen, M. So and F. Heffrom, 1986. Shuttle mutagenesis: a method of transposon mutagenesis for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83: 735–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, A., A. Dawson, C. Mather, H. Gilhooley, Y. Li et al., 1998. Transposition of the Drosophila element mariner into the chicken germ line. Nat. Biotech. 16: 1050–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, K., M. Kamba, H. Sonobe, T. Kanda, A. G. Klinakis et al., 2000. Extrachromosomal transposition of the transposable element Minos occurs in embryos of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Insect Mol. Biol. 9: 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling, A. C., D. M. Stern, I. Kiss, J. Roote, T. Laverty et al., 1995. Gene disruptions using P transposable elements: an integral component of the Drosophila genome project. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 10824–10830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling, A. C., D. Stern, A. Beaton, E. J. Rhem, T. Laverty et al., 1999. The Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project gene disruption project: single P-element insertions mutating 25% of vital Drosophila genes. Genetics 153: 135–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault, S. T., M. A. Singer, W. Y. Miyazaki, B. Milash, N. A. Dompe et al., 2004. A complementary transposon tool kit for Drosophila melanogaster using P and piggyBac. Nat. Genet. 36: 283–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel, C. S. and V. Pirrotta, 1992. Technical notes: new pCaSper P-element vectors. Dros. Inf. Serv. 71: 150. [Google Scholar]

- Törok, T., T. Tick, M. Alvarado and I. Kiss, 1993. P-lacW insertional mutagenesis on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster: isolation of lethals with different overgrowth phenotypes. Genetics 135: 71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigdal, T. H., C. D. Kaufman, Z. Izsvak, D. F. Voytas and Z. Ivics, 2002. Common physical properties of DNA affecting target site selection of Sleeping Beauty and other Tc1/mariner transposable elements. J. Mol. Biol. 323: 441–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos, J. C, I. De Baere and R. H. Plasterk, 1996. Transposase is the only nematode protein required for in vitro transposition of Tc1. Genes Dev. 10: 755–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C., R. K. Pearson, H. J. Bellen, C. J. O'Kane, U. Grossniklaus et al., 1989. P-element-mediated enhancer detection: an efficient method for isolating and characterizing developmentally regulated genes in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 3: 1301–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagoraiou, L., D. Drabek, S. Alexaki, J. A. Guy, A. G. Klinakis et al., 2001. In vivo transposition of Minos, a Drosophila mobile element, in mammalian tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 11474–11478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., U. Sankar, D. J. Lampe, H. M. Robertson and F. L. Graham, 1998. The Himar1 mariner transposase cloned in a recombinant adenovirus vector is functional in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 226: 3687–3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]