Abstract

If a gene is mutated and its function lost, are compensatory genes upregulated? We investigated whether genes are transcriptionally upregulated when their synthetic sick or lethal (SSL) partners are lost. We identified several new examples; however, remarkably few SSL pairs exhibited this phenomenon, suggesting that transcriptional compensation by SSL partners is a rare mechanism for maintaining genetic robustness.

THE ability to tolerate random mutation is critical to an organism's fitness (Kitano 2004). This tolerance often relies on genes or pathways that can compensate for the loss of one another (Tong et al. 2001, 2004). A key indicator of a compensatory relationship is a synthetic sick or lethal (SSL) interaction, in which mutation of two genes in combination yields a more deleterious phenotype than either single mutation alone.

The existence of genetic compensation is well accepted (Nowak et al. 1997; Winzeler et al. 1999; Wagner 2000; Tong et al. 2001, 2004; Gu et al. 2003), but the mechanism by which this compensation is achieved remains unclear. Are compensatory genes, expressed at wild-type levels, sufficient to buffer gene loss? Or does the cell detect loss of a gene and respond by upregulating compensatory genes/pathways (i.e., the SSL interaction partners of the deleted gene)? Previously, Lesage et al. (2004) suggested that transcriptional compensation among SSL partners is rare. Now large mRNA expression and genetic interaction data sets offer an opportunity to address this question on a genome-wide level.

Investigating transcriptional compensation among SSL gene pairs:

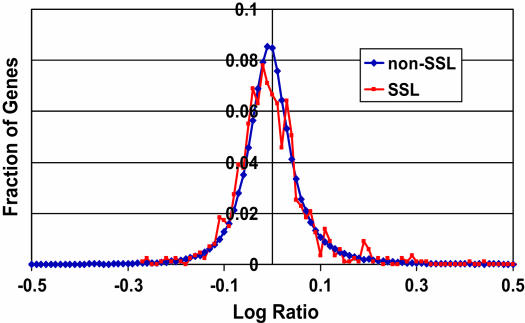

To investigate whether compensatory genes are transcriptionally upregulated in response to gene loss, we employed a large data set of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mRNA expression profiles of single-gene mutants (Winzeler et al. 1999; Hughes et al. 2000a) and a systematically generated data set of gene pairs assessed for SSL interaction (Tong et al. 2001, 2004). For each transcriptionally profiled mutant, we considered expression levels of genes previously assessed for SSL interaction with the mutated gene. For example, if the mutant of gene M was transcriptionally profiled and gene M was also assessed for SSL interaction with a gene G, we considered the expression level of G in the mutant of M. More specifically, for each M:G pair, we compared expression of G in mutant and wild-type cells using log ratios [log (expression in mutant/expression in wild type)]. We excluded profiles of known aneuploid strains (Hughes et al. 2000b) and took averages of log ratios in the cases of duplicate measurements (<10%). We then separately considered M:G pairs with (872) and without (112,686) SSL interaction. The distributions of log ratios for SSL and non-SSL pairs were similar (Figure 1). Normalizing the log ratios using a gene-specific error model (Hughes et al. 2000a) produced similar distributions (data not shown). These data suggest that transcriptional regulation of compensatory genes does not play a global role in maintaining robustness.

Figure 1.

Log ratios of expression for each gene, G, in a gene M mutant strain relative to wild type. M:G gene pairs with an SSL interaction are plotted separately from non-SSL pairs.

We next investigated whether transcriptional compensation played a greater role among SSL M:G pairs with homology in comparison to nonhomologous SSL pairs. Because homologous genes were more likely than nonhomologous genes to overlap in function, we hypothesized that they may exhibit more pronounced compensatory transcriptional effects. Our data did not support this hypothesis (see supplementary material at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/).

Transcriptional compensation among a minority of gene pairs:

Although transcriptional compensation for gene loss did not appear to be a global phenomenon, it has been previously observed for several SSL gene pairs (Terashima et al. 2000; Lesage et al. 2004; Kafri et al. 2005). To systematically identify additional cases, we again considered M:G pairs previously assessed for SSL interaction. Among genes significantly changed in an M mutant (according to significance threshold P < 0.001), SSL partners of M were more likely than non-SSL partners to be transcriptionally upregulated (P = 0.02) (see supplementary material at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/). Therefore, although transcriptional compensation is rare, our results confirm that it does occur for a minority of SSL pairs.

Six of the 13 SSL gene pairs that we found to exhibit transcriptional upregulation were previously noted (Table 1) (Zhao et al. 1998; Lesage et al. 2004), confirming our method of analysis. Five of these 6 were noted by Lesage et al. (2004), who reported transcriptional upregulation for 10 of the SSL pairs that we investigated. That we observed compensation for only 5 of these 10 pairs may reflect experimental error or differences in mutant strains or growth conditions of the mRNA expression data sets.

TABLE 1.

SSL M:G pairs in which expression of gene G is significantly changed in the null mutant of gene M (P < 0.001)

| Gene M (the mutated gene)

|

Gene G (for which mRNA expression was measured)

|

Expression change

|

Transcriptional compensation previously noted

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene IDs | Protein | Description | Gene IDs | Protein | Description | Homology | P-value(s) | ||

| BNI1 YNL271C S000005215 | Formin, involved in spindle orientation | Formin, nucleates the formation of linear actin filaments, involved in cell processes such as budding and mitotic spindle orientation, which require the formation of polarized actin cables, functionally redundant with BNR1. | SLT2 YHR030C S000001072 | Suppressor of lyt2; serine/threonine MAP kinase. | Up | 4.2E-4 | |||

| CDC42 YLR229C S000004219 | Rho subfamily of Ras-like proteins | Small rho-like GTPase essential for establishment and maintenance of cell polarity; mutants have defects in the organization of actin and septins. | GIC2 YDR309C S000002717 | Protein of unknown function involved in initiation of budding and cellular polarization; interacts with Cdc42p via the Cdc42/ Rac-interactive binding domain. | Up | 6.9E-5 | |||

| FKS1 YLR342W S000004334 | 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase | Catalytic subunit of 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase, functionally redundant with alternate catalytic subunit Gsc2p; binds to regulatory subunit Rho1p; involved in cell wall synthesis and maintenance; localizes to sites of cell wall remodeling. | FKS2 GSC2 YGR032W S000003264 | 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase catalytic component | Catalytic subunit of 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase with similarity to an alternate catalytic subunit, Fks1p (Gsc1p); Rho1p encodes the regulatory subunit; involved in cell wall synthesis and maintenance. | Yes | Down | 2.1E-8 | Tereshimaet al. (2000) and Lesage et al. (2004) observed compensatory upregulation. |

| FKS1 YLR342W S000004334 | KAI1 MID2 YLR332W S000004324 | Protein required for mating | Up | 3.2E-4 | |||||

| FKS1 YLR342W S000004334 | PAL2 RIM21 YNL294C S000005238 | Unknown function | Regulator of IME2 | Up | 8.8E-4 | ||||

| FKS1 YLR342W S000004334 | RLM1 YPL089C S000006010 | Serum response factor-like protein that may function downstream of MPK1 (SLT2) MAP-kinase pathway; serum response factor-like protein. | Up | 1.2E-5 2.7E-4 | Zhao et al. (1998) | ||||

| FKS1 YLR342W S000004334 | SLT2 YHR030C S000001072 | Suppressor of lyt2; serine/threonine MAP kinase. | Up | 1.5E-5 9.9E-6 | Lesage et al. (2004) | ||||

| GAS1 YMR307W S000004924 | Cell surface glycoprotein (115–120 kDa) | β-1,3-glucanosyltransferase required for cell wall assembly; localizes to the cell surface via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor. | CHS3 YBR023C S000000227 | Chitin synthase 3 | Chitin synthase III, catalyzes the transfer of N-acetyl glucosamine to chitin; required for synthesis of the majority of cell wall chitin, the chitin ring during bud emergence, and spore wall chitosan. | Up | 7.4E-4 | Lesage et al. (2004) | |

| GAS1 YMR307W S000004924 | KRE11 YGR166W S000003398 | Protein involved in biosynthesis of cell wall β-glucans; subunit of the TRAPP (transport protein particle) complex, involved in the late steps of endoplasmic-reticulum- to-Golgi transport. | Up | 1.2E-4 | Lesage et al. (2004) | ||||

| GAS1 YMR307W S000004924 | SLT2 YHR030C S000001072 | Suppressor of lyt2; serine/threonine MAP kinase. | Up | 6.0E-7 | Lesage et al. (2004) | ||||

| GAS1 YMR307W S000004924 | YMR316C-A S000004933 | Up | 5.0E-6 | ||||||

| GAS1 YMR307W S000004924 | YAL053W S000000049 | Up | 1.5E-5 | Lesage et al. (2004) | |||||

| SHE4 YOR035C S000005561 | Protein containing a UCS (UNC-45/CRO1/SHE4) domain; binds to myosin motor domains to regulate myosin function; involved in endocytosis, polarization of the actin cytoskeleton, and asymmetric mRNA localization. | ARC40 YBR234C S000000438 | Arp2/3 complex subunit, 40 kDa; component of Arp2/Arp3 protein complex. | Up | 3.0E-4 | ||||

| SHE4 YOR035C S000005561 | CHS7 YHR142W S000001184 | Protein of unknown function, involved in chitin biosynthesis by regulating Chs3p export from the ER. | Up | 8.2E-6 | |||||

Presented are the gene identifiers, the protein, and a description of gene M, followed by the same information for gene G; whether M and G proteins are homologous (BLAST E < e-3); direction of expression change of gene G in M null mutant compared to wild type; P-value for significance of change in expression taken from Hughes et al. (2000a); and whether transcriptional compensation for M:G was previously noted in the context of genetic interaction.

For seven pairs, transcriptional upregulation in the context of SSL interaction had not been previously noted (Table 1). However, for the pair CDC42:GIC2, compensation at the protein expression level was previously observed; the level of GIC2 protein increased in the CDC42-null mutant (Jaquenoud et al. 1998). For the remaining six pairs, our observations may help define functional relationships between genetic interactors that exhibit compensatory transcriptional upregulation.

The SSL pair FKS1:RIM21 exhibited transcriptional compensation. Little information on the relationship between the 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase FKS1 and RIM21, a protein of unknown molecular function and cellular component, is available. Our observation of transcriptional compensation by RIM21 in the FKS1-null mutant, in the context of genetic interaction, may help determine the function of RIM21.

Another example, SHE4, is the SSL partner of CHS7. According to the Saccharomyces Genome Database, CHS7 is a protein of unknown function involved in chitin biosynthesis (Dolinski et al. 2004) and was transcriptionally upregulated in the SHE4-null mutant.

Surprisingly, one gene, FKS2, was downregulated in the deletion mutant of its SSL partner, FKS1 (Table 1). This contrasts with the compensatory transcriptional upregulation seen previously (Terashima et al. 2000; Lesage et al. 2004) and may represent an experimental error (see discussion of cross-hybridization below) or differences in the FKS1 mutants or conditions profiled (Hughes et al. 2000a; Lagorce et al. 2003).

In summary, we explored transcriptional upregulation as a mechanism of compensation for gene loss. While we confirmed a handful of previously observed cases and identified several new ones, our data suggest that transcriptional compensation among SSL partners is rare.

Our conclusion agrees with a qualitative observation from a smaller study, which considered SSL partners of three genes involved in β-1,3-glucan assembly and used a different expression data set (Lagorce et al. 2003; Lesage et al. 2004). By contrast, we addressed this question quantitatively and examined the SSL interaction partners of 18 query genes. Therefore, our conclusion has broader scope, encompassing additional biological processes (see supplementary Table S1 at http://www.genetics.org/supplemental/ for query genes examined).

We have likely missed some instances of upregulation of compensatory genes. For example, microarrays are not sensitive enough to detect all transcriptional changes. Furthermore, expression experiments were conducted in rich medium, while SSL interaction was assessed in near minimal medium, so pairs exhibiting compensatory upregulation in minimal but not rich media were missed. In addition, cross-hybridization between paralogous genes may mask cases of compensatory upregulation or may cause the appearance of compensatory downregulation (Hughes et al. 2001). However, even using a permissive definition of homology (BLAST E-value <10−3), only 2% of SSL gene pairs are paralogous (Tong et al. 2004), so this source of decreased sensitivity to compensatory upregulation is unlikely to have affected our overall conclusion. Finally, the SSL interaction data set has a false-negative rate of 17–41% (Tong et al. 2001, 2004), causing us to incorrectly consider some pairs as non-SSL. However, given the remarkably low frequency of compensatory upregulation observed here, increased sensitivity to SSL interaction is unlikely to change our overall conclusion.

Compensation by upregulation may be even rarer than we report here. In some of the 13 cases that we report, the observed upregulation may not be required to achieve compensation. Thus, we may have conservatively overcounted cases of compensation by transcriptional upregulation.

Our study has an interesting parallel to a previous study. Giaever et al. (2002) identified genes required to survive a change in environmental condition, while we examined genes required to survive a change in genotype (i.e., the synthetic lethal partners of deleted genes). In both cases, genes required for surviving the change are often not transcriptionally upregulated.

Collectively, our results and previous ones suggest that transcriptional “retuning” in response to change, environmental or genotypic, is rare. Given the rarity of gene loss, a regulatory network that detects and responds to gene loss may be a large target for mutation with only a weak selection for its maintenance. Furthermore, the potential consequences of a misregulated network may be too costly to justify its benefit. Regardless of the explanation, our study suggests that robustness is generally achieved without a change in mRNA expression of compensatory genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Bussey, F. Winston, E. Elion, and J. Roth for valuable discussion. We thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions. S.L.W. was supported by a Ryan Fellowship. This work was supported by Funds for Discovery provided by John Taplin, by an institutional grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and by NIH/NHGRI grant R01 HG003224.

References

- Dolinski, K., R. Balakrishnan, K. R. Christie, M. C. Costanzo, S. S. Dwight et al., 2004. Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org).

- Giaever, G., A. M. Chu, L. Ni, C. Connelly, L. Riles et al., 2002. Functional profiling of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae genome. Nature 418: 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Z., L. M. Steinmetz, X. Gu, C. Scharfe, R. W. Davis et al., 2003. Role of duplicate genes in genetic robustness against null mutations. Nature 421: 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T. R., M. J. Marton, A. R. Jones, C. J. Roberts, R. Stoughton et al., 2000. a Functional discovery via a compendium of expression profiles. Cell 102: 109–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T. R., C. J. Roberts, H. Dai, A. R. Jones, M. R. Meyer et al., 2000. b Widespread aneuploidy revealed by DNA microarray expression profiling. Nat. Genet. 25: 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T. R., M. Mao, A. R. Jones, J. Burchard, M. J. Marton et al., 2001. Expression profiling using microarrays fabricated by an ink-jet oligonucleotide synthesizer. Nat. Biotechnol. 19: 342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaquenoud, M., M. P. Gulli, K. Peter and M. Peter, 1998. The Cdc42p effector Gic2p is targeted for ubiquitin-dependent degradation by the SCFGrr1 complex. EMBO J. 17: 5360–5373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafri, R., A. Bar-Even and Y. Pilpel, 2005. Transcription control reprogramming in genetic backup circuits. Nat. Genet. 37: 295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitano, H., 2004. Biological robustness. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5: 826–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagorce, A., N. C. Hauser, D. Labourdette, C. Rodriguez, H. Martin-Yken et al., 2003. Genome-wide analysis of the response to cell wall mutations in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 20345–20357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, G., A. M. Sdicu, P. Menard, J. Shapiro, S. Hussein et al., 2004. Analysis of β-1,3-glucan assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a synthetic interaction network and altered sensitivity to caspofungin. Genetics 167: 35–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M. A., M. C. Boerlijst, J. Cooke and J. M. Smith, 1997. Evolution of genetic redundancy. Nature 388: 167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima, H., N. Yabuki, M. Arisawa, K. Hamada and K. Kitada, 2000. Up-regulation of genes encoding glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-attached proteins in response to cell wall damage caused by disruption of FKS1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264: 64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. H., M. Evangelista, A. B. Parsons, H. Xu, G. D. Bader et al., 2001. Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294: 2364–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A. H., G. Lesage, G. D. Bader, H. Ding, H. Xu et al., 2004. Global mapping of the yeast genetic interaction network. Science 303: 808–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A., 2000. Robustness against mutations in genetic networks of yeast. Nat. Genet. 24: 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler, E. A., D. D. Shoemaker, A. Astromoff, H. Liang, K. Anderson et al., 1999. Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285: 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C., U. S. Jung, P. Garrett-Engele, T. Roe, M. S. Cyert et al., 1998. Temperature-induced expression of yeast FKS2 is under the dual control of protein kinase C and calcineurin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18: 1013–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]