Abstract

Glutathione is a ubiquitous molecule found in all parts of the cell where it fulfils a range of functions from detoxification to protection from oxidative damage. It provides the main redox buffer for cells and as such has been implicated in the formation of native disulphide bonds. However, the discovery of the enzyme Ero1 has called into question the exact role of glutathione in this process. In this review, we discuss the arguments for and against a role for glutathione in facilitating disulphide-bond formation and consider its role in protecting the cell from endoplasmic-reticulum-generated oxidative stress.

Keywords: disulphide-bond formation, endoplasmic reticulum, glutathione, oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species

Introduction

Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide (L-γ-glutamyl-L-cysteinyl-glycine) that is synthesized in the cytosol from the precursor amino acids glutamate, cysteine and glycine. The cell contains millimolar concentrations of GSH (up to 10 mM) that is maintained in this reduced form by a cytosolic NADPH-dependent reaction catalysed by glutathione reductase. Protein disulphide bonds rarely form in the cytosol because of the high concentrations of GSH. By contrast, the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) contains a relatively higher concentration of oxidized glutathione (GSSG; Hwang et al, 1992). This allows the formation of native disulphide bonds in the ER through a complex process involving not only disulphide-bond formation, but also the isomerization of non-native disulphide bonds. Both reactions can be catalysed by protein disulphide isomerase (PDI) and possibly other oxidoreductases that share common domains with PDI (for a recent review, see Ellgaard & Ruddock, 2005). PDI has two active sites, both of which are characterized by the presence of a CGHC motif, which either forms a disulphide for the enzyme to become active as an oxidase, or a dithiol for the enzyme to act as an isomerase. GSSG is widely believed to be involved in the oxidation of PDI, but it has been shown that the ER flavoprotein Ero1 catalyses the oxidation of PDI in vivo and in vitro (Frand & Kaiser, 1998, 1999; Pollard et al, 1998; Tu et al, 2000; Tu & Weissman, 2002). These results indicate that the process of disulphide-bond formation might occur independently of GSSG. However, this does not explain the fact that, in the ER, the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione ([GSH]:[GSSG]) is optimal for disulphide-bond formation (Lyles & Gilbert, 1991). Recently, it has been suggested that GSH might have a role in ensuring the ER oxidoreductases are maintained in a reduced state so that they can catalyse reduction or isomerization reactions (Chakravarthi & Bulleid, 2004; Jessop & Bulleid, 2004; Molteni et al, 2004). It is still not known why an oxidizing balance of glutathione is required in the ER or how this balance is maintained. In addition to a role in disulphide-bond formation, it has been suggested that glutathione provides a redox buffer against ER-generated oxidative stress. The oxidation of PDI by Ero1 is thought to occur through disulphide exchange that results in the formation of reduced Ero1 (Gross et al, 2004). Ero1 can be oxidized rapidly in the presence of flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) and oxygen, indicating that oxygen is the ultimate electron acceptor (Tu & Weissman, 2002). The reactivation of Ero1 by molecular oxygen generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the ER. How the cell is protected from the damage caused by ER-generated ROS is poorly understood; however, recent data suggest that GSH might have an important role in this process.

What is the oxidant during disulphide formation?

GSSG was one of the first molecules proposed to provide oxidizing equivalents for the formation of disulphide bonds. This proposal was based in part on the finding that [GSH]:[GSSG] in the secretory pathway and in microsomal vesicles is similar to the ratio found in redox buffers that are effective for the oxidative folding of proteins in vitro—that is, between 1:1 and 3:1 (Bass et al, 2004; Hwang et al, 1992). The argument is compelling: why would the cell maintain a glutathione balance within the ER lumen that provides the optimal redox potential for PDI to catalyse disulphide bond formation if glutathione is not involved in the oxidation of PDI? However, the measurement of the ratio of [GSH]:[GSSG] in an intracellular organelle is fraught with technical difficulties. Initial studies used a redox probe, which allowed a measurement of ratios, but not absolute concentrations, and measured redox state throughout the secretory pathway rather than specifically in the ER (Hwang et al, 1992). Recent work has measured absolute concentrations, but only after isolation of ER-derived microsomal vesicles (Bass et al, 2004). Unfortunately, glutathione can leak from microsomes, altering the [GSH]:[GSSG] ratio during their preparation, which would affect the values. Nevertheless, the results show that the redox environment in the ER is more oxidizing than the cytosol and that GSSG must be generated through an oxidative pathway.

The discovery of Ero1 as a provider of oxidizing equivalents for the formation of disulphide bonds (Frand & Kaiser, 1998; Pollard et al, 1998; Sevier et al, 2001) led researchers to question the hypothesis that GSSG is solely responsible for the oxidation of PDI in the ER. Yeast strains carrying a conditional mutation in Ero1 were compromised in their ability to form disulphide bonds in secreted proteins when grown at the non-permissive temperature. PDI is normally present in the oxidized form at steady state in yeast cells, but was predominantly reduced in an Ero1 mutant. In vitro experiments showed that the Ero1-mediated oxidation of folding substrates is mainly independent from the bulk redox buffer. Ero1 can efficiently drive the oxidation of RNase A through PDI in the absence of GSH or GSSG, or even in the presence of excess GSH (Tu et al, 2000), indicating that oxidative protein folding proceeds through the direct transfer of oxidizing equivalents between PDI and Ero1. It is difficult to explain these results in any other way than that Ero1 directly oxidizes PDI, which in turn oxidizes substrates. However, these results do not rule out a role for GSSG as an alternative source of oxidizing equivalents for PDI.

One obvious explanation for the low ratio of [GSH]:[GSSG] is that Ero1 activity leads to the oxidation of GSH. In vitro experiments suggest that GSH is a poor substrate for Ero1 (Tu & Weissman, 2002). However, when the rate of GSH oxidation was measured in yeast cells it was found to correlate with Ero1 activity. The regeneration of GSSG was slower in an ero1-1 mutant strain than in wild-type cells, and was faster in cells overexpressing Ero1 from a multicopy plasmid (Cuozzo & Kaiser, 1999). In addition, deletion of the GSH1 gene—encoding γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS), the enzyme catalysing the first step in glutathione synthesis—was shown to suppress an Ero1 conditional mutant, again indicating that GSH provides an additional load on Ero1 activity (Frand & Kaiser, 1998). These results suggest a link between GSH oxidation and Ero1 activity that, if not direct, could be through the reduction of non-native disulphides or members of the PDI family.

Does GSH reduce non-native disulphides?

Evidence that GSH might have an essential role as a reductant, rather than as an oxidant, initially came from studies in which the synthesis of GSH was prevented. In mice, a null mutation in the gene encoding one subunit of γ-GCS was found to be embryonic lethal. However, cell lines isolated from the mutants could grow indefinitely in a medium supplemented with N-acetylcysteine (Shi et al, 2000). Similarly, a yeast strain lacking a functional copy of the GSH1 gene was unable to grow on minimal media. Growth was restored by supplementing the media with 1 mM GSH or with other thiols, such as β-mercaptoethanol, dithiothreitol or cysteine (Cuozzo & Kaiser, 1999). The function of glutathione can be complemented by the addition of reducing agents, suggesting that the main role for glutathione is in reduction rather than oxidation.

One potential role for GSH in the ER could be to reduce non-native disulphide bonds that form in proteins either as the result of oxidative stress or by enzyme-catalysed oxidation. Such non-native disulphide bonds are now known to form in proteins under normal physiological conditions (Jansens et al, 2002). Two recent studies provide evidence that glutathione has a crucial role in the isomerization of non-native disulphide bonds. Both studies showed that when the levels of total glutathione were diminished, the formation of disulphide bonds increased (Chakravarthi & Bulleid, 2004; Molteni et al, 2004). However, this increase in oxidation was accompanied by an increase in non-native disulphide-bond formation. In addition, the absence or decrease in levels of cytosolic GSH resulted in PDI becoming more oxidized, limiting the ability of the enzyme to isomerize non-native disulphide bonds. Therefore, in a GSH-compromised system, the increase in the rate of formation of disulphide bonds is accompanied by an increase in the time required for isomerization. These results suggest that, directly or indirectly, GSH is involved in the isomerization of non-native disulphides.

Does GSH act through the ER oxidoreductases?

Recent studies have shown that, in mammalian cells, most of the active-site disulphides in the ER oxidoreductases are reduced under normal steady-state conditions (Jessop & Bulleid, 2004). Recovery of one of these enzymes (ERp57) from oxidation required the presence of cytosol and, more specifically, GSH. Futhermore, GSH was found to reduce ERp57 rapidly at physiological concentrations in vitro, and biotinylated glutathione formed mixed disulphides with ERp57, confirming earlier work showing that glutathione forms a mixed disulphide with ERp57 in intact cells (Fratelli et al, 2002). This indicates that GSH is the main reductant responsible for maintaining the ER oxidoreductases in a reduced form, which is necessary for the reduction or isomerization of non-native disulphide bonds.

Although the secretory pathway promotes oxidative folding through the oxidoreductase family, a large proportion of glutathione in the ER lumen is found as mixed disulphides with proteins (Bass et al, 2004). These mixed disulphides could be formed either during the oxidation of proteins by GSSG or by the reduction of proteins by GSH. Many substrate proteins are able to fold spontaneously in a glutathione buffer in the absence of oxidoreductases. However, the rate of folding is increased dramatically in the presence of enzymes such as PDI (Weissman & Kim, 1993) or ERp57 (Zapun et al, 1998). For GSH to reduce a non-native disulphide bond, it must first glutathionylate one of the cysteine residues. A second glutathione molecule must then attack the glutathionylated protein, thereby releasing GSSG and a reduced substrate protein. By contrast, the C-terminal cysteine of the CXXC motif of PDI is positioned perfectly to resolve the mixed disulphide. Thus, the CXXC motif present in the ER oxidoreductases ensures efficient reduction or isomerization. Polypeptide-binding domains in PDI also increase the efficiency of disulphide-bond isomerization (Winter et al, 2002). Therefore, although GSH is potentially able to reduce non-native disulphide bonds in newly synthesized proteins, there is a kinetic advantage for this reduction to be catalysed by the ER oxidoreductases.

How is the [GSH]:[GSSG] ratio maintained in the ER?

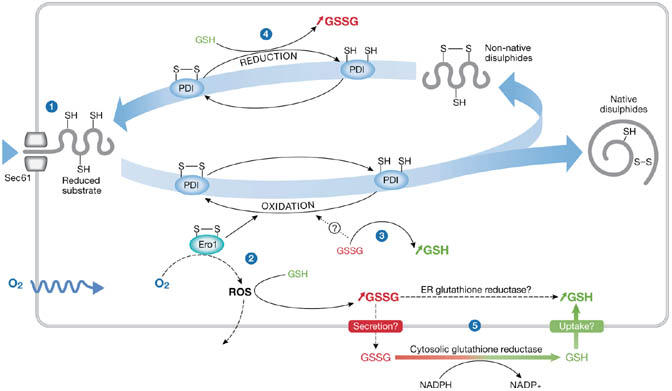

A model that seeks to explain the role of glutathione within the ER must take into account how the redox balance becomes distinct from the cytosol. In an attempt to understand how this balance is maintained, it is important to consider some of the sources of reducing or oxidizing equivalents that occur from disulphide-bond formation within the ER lumen (Fig 1). Reducing equivalents are continuously introduced during protein translocation as cysteine residues in nascent chains. These residues can undergo oxidation to form disulphide bonds and thus reduce PDI or an equivalent ER oxidoreductase. PDI oxidation by Ero1 leads to the production of ROS (Gross et al, 2006). The fate of any ROS produced is unclear; they could diffuse into the cytosol, or they could react with GSH in the ER, leading to an increase in GSSG. In addition, the reduction of non-native disulphide bonds would lead to an increase in the level of GSSG, particularly if the resulting cysteine residues remain reduced or reform native disulphide bonds through an Ero1-catalysed oxidative pathway. If Ero1 has a significant role in disulphide-bond formation, then the net consequence would be an increase in the concentration of GSSG relative to GSH. Conversely, if GSSG oxidizes PDI, then the net result would be an increase in the concentration of GSH relative to GSSG. Therefore, balancing Ero1 and GSSG oxidation of PDI could regulate the [GSH]:[GSSG] ratio.

Figure 1.

The production of reduced or oxidized glutathione can occur at various stages during the formation of native disulphide bonds. Protein disulphide isomerase (PDI) is used as an example of how the levels of reduced glutathione (GSH) or oxidized glutathione (GSSG) are maintained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). (1) Free cysteines are introduced into the ER in the form of newly translocated proteins. (2) Disulphide bonds are formed by PDI, which is reduced. PDI is oxidized by Ero1,which is oxidized by O2, a process that generates reactive oxygen species (ROS). Detoxification of ROS can lead to an increase in GSSG. (3) PDI might also be oxidized by GSSG leading to an increase in GSH. (4) PDI is reduced by GSH, which leads to an increase in GSSG. (5) Influx and efflux of GSH or GSSG from the ER may control their ratio. Cytosolic GSSG is reduced by glutathione reductase. Similar activity might occur in the ER lumen.

Another source of reducing equivalents comes from the selective transport of GSH, rather than GSSG, from the cytosol into the ER lumen. Selective transport of GSH across the ER membrane has been shown in mammalian liver microsomes (Banhegyi et al, 1999), and into the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skeletal muscle (Banhegyi et al, 2003). However, these studies contrast with earlier work that showed the preferential transport of GSSG compared with GSH into microsomes (Hwang et al, 1992). The uptake of GSH (or GSSG) could be through a specific transporter—such as a homologue of CydDC, which is an ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-type transporter that has recently been identified to export GSH and cysteine specifically to the periplasm of Escherichia coli (Pittman et al, 2005). This transporter has similarities to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), which has been shown to be responsible for GSH flux from lung airway epithelial cells (Kogan et al, 2003), suggesting that ABC transporters might function in the transport of glutathione in mammalian cells. Conversely, it has been suggested that the ER membrane might be permeable to small molecules such as GSH (but not GSSG), allowing transport to occur by diffusion (Le Gall et al, 2004). Whether a specific transporter exists for glutathione import into the ER requires further investigation, but it is clear that the selective transport of GSH would provide one possible mechanism for the regulation of the [GSH]:[GSSG] ratio in the ER lumen.

As already mentioned, Ero1 activity might lead indirectly to the production of GSSG, as will any reduction of ER oxidoreductases by GSH. The fate of the luminal GSSG generated is unclear; it could be reduced within the ER by a glutathione reductase, it could be transported to the cytosol for reduction, or it could be secreted from the cell. Regardless of the method, removal or reduction of GSSG will affect the [GSH]:[GSSG] ratio. Answers to the questions of how glutathione is transported across the ER membrane and whether any ER glutathione reductase activity exists will increase our understanding of how the cell regulates the glutathione buffer in the ER.

Stress

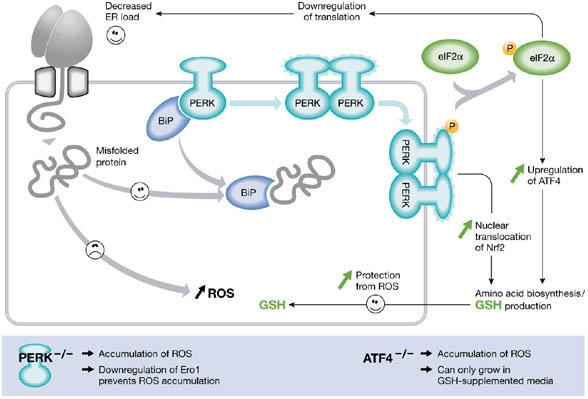

Disulphide-bond formation in the ER of both mammalian and yeast cells can lead to the formation of ROS (Harding et al, 2003; Haynes et al, 2004). Both of these studies used mutant cells that were compromised in their ability to respond to ER stress. In mammalian cells, ER stress leads to an integrated stress response involving the related transmembrane kinases Ire1α, Ire1β and PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), and the transmembrane activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (Zhang & Kaufman, 2004). Phosphorylation of eIF2α by PERK in response to ER stress decreases translation of mRNA and reduces stress (Harding et al, 2003). Paradoxically, synthesis of the transcription factor ATF4 is activated by PERK. PERK-dependent signals also lead to the activation of the transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2; Cullinan et al, 2003). The transcription factors ATF4 and Nrf2 couple ER stress to a general cellular response that increases the production of glutathione by increasing amino-acid metabolism (Cullinan et al, 2003; Harding et al, 2003). The consequence of PERK activation is that there is a general decrease in protein synthesis and an increase in the synthesis of glutathione (Fig 2). Interestingly, in cells that lack PERK, peroxides such as H2O2 accumulate after ER stress. However, this effect is largely eliminated by lowering Ero1 function through RNA interference, indicating that Ero1 activity in vivo leads to the production of ROS. Cells lacking ATF4 can only grow when supplemented with a reducing agent due to the unregulated production of ER-generated ROS. The fact that GSH production is required during conditions that cause overproduction of ER-generated ROS suggests a role for GSH in their elimination.

Figure 2.

PKR-like ER kinase-dependent stress response to protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum of mammalian cells. The unfolded protein response in mammalian cells leads to the activation of the transmembrane kinases, Ire1α, Ire1β, PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) and the transmembrane activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). The PERK pathway is activated after dissociation of BiP from PERK monomers, causing dimerization and activation of the cytosolic kinase domain. (Note that the role of BiP in this process is unclear (Credle et al, 2005).) This activation leads to the phosphorylation of eIF2α, causing attenuation of translation and thereby alleviating endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. However, translation of transcription factor ATF4 is stimulated and, with activation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), leads to an induction of genes involved in amino-acid synthesis. The cellular level of glutathione is increased, which can potentially protect the cell from damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced during ER stress. Perturbation of either the PERK or ATF4 pathway leads to an increase in the production of ER-derived ROS.

The ability of mammalian cells to adapt to ER oxidative stress by increased synthesis of GSH is mirrored in yeast cells. Mutant strains that are unable to degrade ER proteins show an increased sensitivity to ER stress, ROS accumulation and cell death (Haynes et al, 2004). The production of ROS is linked to the overexpression of a misfolded disulphide-bonded protein, carboxypeptidase Y (CPY*); however, the overexpression of a CPY* with mutated cysteine residues does not lead to the same increased production of ROS. Addition of GSH to the growth media allows these cells to grow by diminishing the levels of ROS, providing a direct link between GSH and protection against ER oxidative stress. Therefore, in both mammalian and yeast cells, the response to an increase in oxidative stress is an elevation of the levels of glutathione, which can be used to eliminate ROS and facilitate native disulphide-bond formation.

Summary

The prevailing view on the role of glutathione in protein disulphide-bond formation is that this tripeptide acts as a net reductant in the ER, either by maintaining ER oxidoreductases in a reduced state or by directly reducing non-native disulphide bonds in substrate folding proteins. The consequence of this role is that the ER is a net consumer of GSH and the GSSG has to be recycled by an unidentified mechanism. The identification of oxygen as the ultimate electron acceptor after the formation of disulphide bonds in proteins means that the products of the reduction of oxygen have to be removed to prevent damage to cellular components. The ability of cells to respond to this threat by the up regulation of GSH biosynthesis provides an intricate balance of reducing to oxidizing equivalents, allowing the redox homeostasis in the cell to be maintained. Any perturbation of this balance, caused by excessive production of disulphide bonds during normal protein secretion or the production of mutant misfolded protein, might cause an excess of ROS to accumulate and ultimately lead to cell death. Glutathione has a main role not only in allowing native disulphide bonds to form, but also in balancing redox reactions and thereby protecting the cell from oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

We thank The Wellcome Trust and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council for financial support.

References

- Banhegyi G, Lusini L, Puskas F, Rossi R, Fulceri R, Braun L, Mile V, di Simplicio P, Mandl J, Benedetti A (1999) Preferential transport of glutathione versus glutathione disulfide in rat liver microsomal vesicles. J Biol Chem 274: 12213–12216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banhegyi G, Csala M, Nagy G, Sorrentino V, Fulceri R, Benedetti A (2003) Evidence for the transport of glutathione through ryanodine receptor channel type 1. Biochem J 376: 807–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass R, Ruddock LW, Klappa P, Freedman RB (2004) A major fraction of endoplasmic reticulum-located glutathione is present as mixed disulfides with protein. J Biol Chem 279: 5257–5262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarthi S, Bulleid NJ (2004) Glutathione is required to regulate the formation of native disulphide bonds within proteins entering the secretory pathway. J Biol Chem 279: 39872–39879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Credle JJ, Finer-Moore JS, Papa FR, Stroud RM, Walter P (2005) Inaugural article: on the mechanism of sensing unfolded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 18773–18784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA (2003) Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol 23: 7198–7209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuozzo JW, Kaiser CA (1999) Competition between glutathione and protein thiols for disulphide-bond formation. Nat Cell Biol 1: 130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L, Ruddock LW (2005) The human protein disulphide isomerase family: substrate interactions and functional properties. EMBO Rep 6: 28–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frand AR, Kaiser CA (1998) The ERO1 gene of yeast is required for oxidation of protein dithiols in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell 1: 161–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frand AR, Kaiser CA (1999) Ero1p oxidizes protein disulfide isomerase in a pathway for disulfide bond formation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell 4: 469–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratelli M et al. (2002) Identification by redox proteomics of glutathionylated proteins in oxidatively stressed human T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 3505–3510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Kastner DB, Kaiser CA, Fass D (2004) Structure of Ero1p, source of disulfide bonds for oxidative protein folding in the cell. Cell 117: 601–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross E, Sevier CS, Heldman N, Vitu E, Bentzur M, Kaiser CA, Thorpe C, Fass D (2006) Generating disulfides enzymatically: reaction products and electron acceptors of the endoplasmic reticulum thiol oxidase Ero1p. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 299–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP et al. (2003) An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol Cell 11: 619–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes CM, Titus EA, Cooper AA (2004) Degradation of misfolded proteins prevents ER-derived oxidative stress and cell death. Mol Cell 15: 767–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang C, Sinskey AJ, Lodish HF (1992) Oxidized redox state of glutathione in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 257: 1496–1502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansens A, van Duijn E, Braakman I (2002) Coordinated nonvectorial folding in a newly synthesized multidomain protein. Science 298: 2401–2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop CE, Bulleid NJ (2004) Glutathione directly reduces an oxidoreductase in the endoplasmic reticulum of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 279: 55341–55347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan I, Ramjeesingh M, Li C, Kidd JF, Wang YC, Leslie EM, Cole SPC, Bear CE (2003) CFTR directly mediates nucleotide-regulated glutathione flux. EMBO J 22: 1981–1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall S, Neuhof A, Rapoport T (2004) The endoplasmic reticulum membrane is permeable to small molecules. Mol Biol Cell 15: 447–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyles MM, Gilbert HF (1991) Catalysis of the oxidative folding of ribonuclease A by protein disulfide isomerase: dependence of the rate on the composition of the redox buffer. Biochemistry 30: 613–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molteni SN, Fassio A, Ciriolo MR, Filomeni G, Pasqualetto E, Fagioli C, Sitia R (2004) Glutathione limits Ero1-dependent oxidation in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 279: 32667–32673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman MS, Robinson HC, Poole RK (2005) A bacterial glutathione transporter (Escherichia coli CydDC) exports reductant to the periplasm. J Biol Chem 280: 32254–32261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard MG, Travers KJ, Weissman JS (1998) Ero1p: a novel and ubiquitous protein with an essential role in oxidative protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell 1: 171–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevier CS, Cuozzo JW, Vala A, Aslund F, Kaiser CA (2001) A flavoprotein oxidase defines a new endoplasmic reticulum pathway for biosynthetic disulphide bond formation. Nat Cell Biol 3: 874–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi ZZ, Osei-Frimpong J, Kala G, Kala SV, Barrios RJ, Habib GM, Lukin DJ, Danney CM, Matzuk MM, Lieberman MW (2000) Glutathione synthesis is essential for mouse development but not for cell growth in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 5101–5106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu BP, Weissman JS (2002) The FAD- and O(2)-dependent reaction cycle of Ero1-mediated oxidative protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Mol Cell 10: 983–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu BP, Ho-Schleyer SC, Travers KJ, Weissman JS (2000) Biochemical basis of oxidative protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 290: 1571–1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman JS, Kim PS (1993) Effcient catalysis of disulphide bond rearrangements by protein disulphide isomerase. Nature 365: 185–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter J, Klappa P, Freedman RB, Lilie H, Rudolph R (2002) Catalytic activity and chaperone function of human protein-disulfide isomerase are required for the efficient refolding of proinsulin. J Biol Chem 277: 310–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapun A, Darby NJ, Tessier DC, Michalak M, Bergeron JJ, Thomas DY (1998) Enhanced catalysis of ribonuclease B folding by the interaction of calnexin or calreticulin with ERp57. J Biol Chem 273: 6009–6012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Kaufman RJ (2004) Signaling the unfolded protein response from the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 279: 25935–25938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]