Abstract

The E6 and E7 of the cutaneous human papillomavirus (HPV) type 38 immortalize primary human keratinocytes, an event normally associated with the inactivation of pathways controlled by the tumour suppressor p53. Here, we show for the first time that HPV38 alters p53 functions. Expression of HPV38 E6 and E7 in human keratinocytes or in the skin of transgenic mice induces stabilization of wild-type p53. This selectively activates the transcription of ΔNp73, an isoform of the p53-related protein p73, which in turn inhibits the capacity of p53 to induce the transcription of genes involved in growth suppression and apoptosis. ΔNp73 downregulation by an antisense oligonucleotide leads to transcriptional re-activation of p53-regulated genes and apoptosis. Our findings illustrate a novel mechanism of the alteration of p53 function that is mediated by a cutaneous HPV type and support the role of HPV38 and ΔNp73 in human carcinogenesis.

Keywords: cutaneous HPV38, E6 and E7, p53, ΔNp73

Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) constitute a large and ubiquitous family of viruses that can be subdivided into cutaneous and mucosal types (de Villiers et al, 2004). The mucosal ‘high-risk' types are the aetiological agent of cervical cancer (zur Hausen, 2002). In this subgroup, HPV16 is the most frequently detected type in malignant lesions, being present in about 50% of cervical cancers worldwide (Clifford et al, 2003). HPV16 early proteins E6 and E7 disrupt the regulation of apoptosis and cell cycle by binding and promoting degradation of the tumour suppressors p53 and retinoblastoma (pRb), respectively (reviewed by zur Hausen, 2002). In contrast to mucosal high-risk HPV types, the involvement of cutaneous HPV types in human carcinogenesis is still unclear. Cutaneous HPV types that belong to the beta genus of the HPV phylogenetic tree (de Villiers et al, 2004) were first isolated in patients suffering from a rare autosomal recessive cancer-prone genetic disorder, epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV), and are consistently detected in non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) from EV, immunocompromised and normal individuals (reviewed by Pfister, 2003). However, a direct role of the EV HPV types in cancer development remains to be proved. In particular, very little is known about the transforming properties of the EV HPV E6 and E7 proteins.

We have recently shown that E6 and E7 proteins of the EV HPV type 38, like E6 and E7 of mucosal carcinogenic HPV type 16, are able to immortalize primary human keratinocytes (Caldeira et al, 2003), an event normally associated with functional loss of pathways controlled by pRb and p53 (zur Hausen, 2002). HPV38 E7 efficiently inactivates pRb and alters cell-cycle control (Caldeira et al, 2003), whereas HPV38 E6, in contrast to HPV16 E6, is unable to induce p53 degradation (Caldeira et al, 2004). Thus, it is unclear whether HPV38 E6 and E7 induce immortalization of primary keratinocytes without targeting the p53 pathway. Using in vitro and in vivo models, we show here that HPV38 E6 and E7 expression induces the accumulation of ΔNp73α, which in turn inhibits the capacity of p53 to induce the transcription of genes involved in growth suppression and apoptosis. Our findings indicate a novel mechanism of HPV-mediated p53 inactivation.

Results

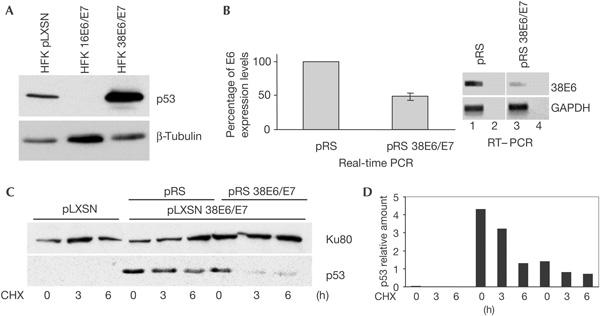

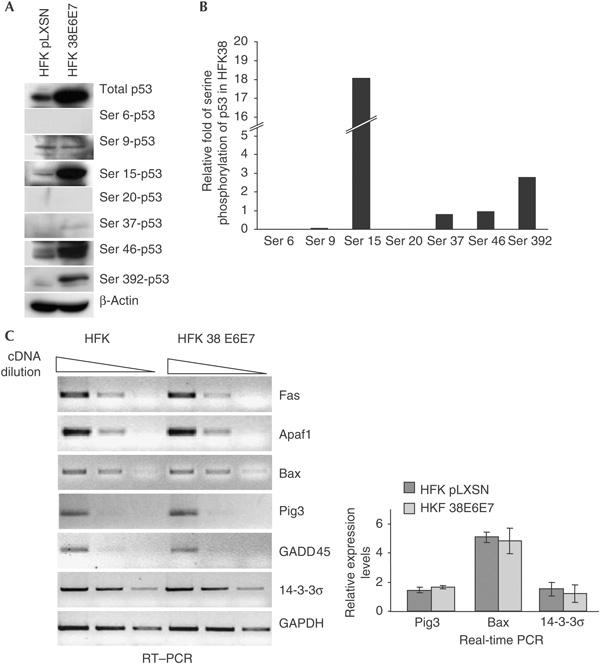

HPV38 induces p53 stabilization

To evaluate the status of p53 in human keratinocytes immortalized by HPV38 E6 and E7 (hereafter referred to as HPV38-keratinocytes), we first determined its protein levels by immunoblotting. p53 is strongly accumulated in HPV38-keratinocytes in comparison with primary keratinocytes (Fig 1A). Infection with retrovirus expressing HPV38 E6 and E7 small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs; pRS 38E6/E7) inhibited viral gene expression as shown by real-time and reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR; Fig 1B) and greatly decreased the half-life of p53 (Fig 1C,D). To exclude the possibility that p53 stabilization might also result from an accidental mutation in the TP53 gene, we sequenced exons 2–9 (plus flanking splice junctions) in the HPV38-keratinocytes, and confirmed a wild-type sequence (data not shown). Stabilization of wild-type p53 is normally associated with phosphorylation (Bode & Dong, 2004). Immunoblot analyses using antibodies specific for various phosphorylated forms of p53 showed a marked increase in phosphorylation of p53 at serines 15 and 392 in HPV38-keratinocytes, compared with cells infected with empty retrovirus (pLXSN; Fig 2A,B). In contrast, serine 9 was less phosphorylated in the HPV38-transformed cells than in control cells. No changes in phosphorylation status were observed at serines 6, 20, 37 and 46 (Fig 2A,B). Immunofluorescence staining showed that p53 was distributed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus in control cells, whereas it was exclusively localized in the nucleus in HPV38-keratinocytes (supplementary Fig 1 online). Despite the presence of high levels of p53 in the nucleus, HPV38-keratinocytes actively proliferate and do not show any sign of apoptotis (data not shown), indicating that the function of p53 may be impaired in these cells. Fig 2C shows that p53-regulated genes encoding proteins involved in apoptosis (Fas, Apaf1, Bax and Pig3), cell cycle (14-3-3σ) and DNA repair (GADD45) were not upregulated in HPV38-keratinocytes in comparison with primary cells. Taken together, these data indicate that expression of HPV38 E6 and E7 in human keratinocytes induces the phosphorylation of specific serine residues, resulting in the stabilization of a nuclear p53 form with impaired transcriptional functions.

Figure 1.

HPV38 E6 and E7 induce stabilization of p53. (A) Human foreskin keratinocytes (HFKs) expressing HPV38 E6 and E7 harbour high levels of p53. Immunoblotting was performed using the indicated antibodies. (B) Downregulation of HPV38 E6 and E7 by small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs). HPV38-HFKs were infected with empty pRetroSuper (pRS) or pRS containing shRNA for HPV38 E6/E7 (pRS 38E6/E7) and E6 messenger RNA was determined by real-time and reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR). The real-time PCR data are the mean of three independent experiments. RT–PCR was performed using the indicated primers. As control, PCRs were performed on non-reverse-transcribed RNA (lanes 2,4). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (C,D) Downregulation of HPV38 E6 and E7 decreases p53 half-life. The indicated cell lines were cultured in a medium containing cycloheximide (CHX) as described in Methods. The levels of p53 and Ku80 (loading control) were determined by immunoblotting (C) and the amount of p53 and Ku80 was quantified by Fluor-S™ MultiImager (Bio-Rad) (D).

Figure 2.

Status of p53 in HPV38-keratinocytes. (A) Characterization of p53 phosphorylation pattern. Protein extracts of the indicated cells were analysed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. (B) Quantification of the increase in p53 phosphorylation in human foreskin keratinocyte (HFK) HPV38 E6/E7 in comparison with HFK pLXSN. The amounts of total and phosphorylated p53 shown in (A) were quantified as described in Methods. After normalization of the levels of the different phosphorylated forms of p53 to the signal for total p53, the relative level of p53 phosphorylation in HFK HPV38 E6/E7 cells was evaluated in comparison with primary keratinocytes (HFK pLXSN). (C) p53-regulated genes are not upregulated in HPV38-HFKs. After reverse transcription, PCR was performed on serial dilutions of the complementary DNA with the indicated primers. The real-time PCR data are the mean of three independent experiments.

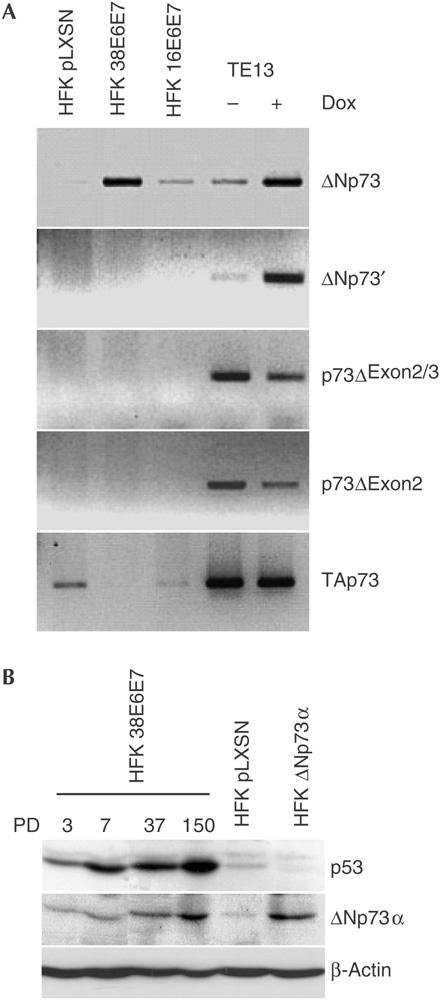

ΔNp73 is upregulated in HPV38-keratinocytes

It has been shown that isoforms of the p53-related protein, p73, lacking the amino-terminal transcriptional activation (TA) domain, collectively called Δ (delta) isoforms, antagonize the transactivation functions of p53 and p73 (reviewed by Melino et al, 2002). The isoforms ΔNp73′, p73ΔExon2/3 and p73ΔExon2 are generated by alternative splicing at the 5′ region of the p73 messenger RNA, whereas the ΔNp73 isoform is expressed by the internal promoter located in intron 3 that contains a p53-responsive element (p53-RE; Levrero et al, 2000; Melino et al, 2002). RT–PCR analysis showed that HPV38-keratinocytes express high levels of the ΔNp73 isoform (Fig 3A). This isoform is absent in primary cells and is weakly expressed in keratinocytes expressing HPV16 E6 and E7 (Fig 3A). In addition, the Δ isoforms generated by internal splicing are not expressed in all three types of keratinocyte, whereas TAp73 is downregulated in HPV38-keratinocytes in comparison with primary keratinocytes (Fig 3A). An identical expression pattern was found in three independent lines of HPV38-keratinocytes (data not shown).

Figure 3.

HPV38 E6 and E7 expression promotes ΔNp73 accumulation. (A) The Δ isoform detected in HPV38-HFK (human foreskin keratinocyte) is expressed from the p73 p2 internal promoter. Reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR) was performed using specific primers for the different Δ isoforms. As control, complementary DNA of RNA extracted from untreated or doxorubicin (Dox)-treated (1 μg/μl; 24 h) p53−/− oesophageal tumour cells (TE13) was used. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (B) ΔNp73α protein is present at high levels in HPV38-keratinocytes. Protein extracts of HPV38-HFK taken at different population doublings (PD) and HFK infected with ΔNp73α retrovirus were analysed by immunoblotting.

At least six different ΔNp73 carboxy-terminal variants are generated by alternative splicing at the 3′ region (termed α, β, γ, δ, ɛ and ζ; Levrero et al, 2000). We determined by RT–PCR that ΔNp73α was the predominant, if not the only, isoform present in HPV38-keratinocytes (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis with an anti-p73 antibody detected a protein band with an approximate molecular mass of 60 kDa that co-migrated with the ectopically expressed ΔNp73α isoform (Fig 3B), confirming the RT–PCR data. ΔNp73 and p53 accumulation became apparent immediately after infection of keratinocytes with HPV38 E6/E7 retrovirus, but was enhanced at later population doublings (Fig 3B).

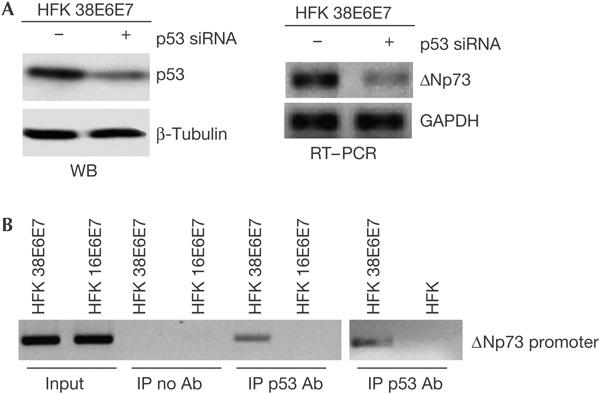

Next, we determined whether downregulation of p53 by short interfering RNA (siRNA) decreases ΔNp73 levels. Fig 4A shows that silencing of p53 expression correlated with downregulation of ΔNp73. Similar results were obtained using HPV38 E6 and E7 shRNAs that decreased the levels of p53 as well as ΔNp73α (data not shown). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments showed that p53 is associated with the ΔNp73 promoter in HPV38-keratinocytes, but not in primary or HPV16-keratinocytes (Fig 4B). Thus, the expression of ΔNp73α in HPV38-keratinocytes is p53 dependent.

Figure 4.

HPV38-mediated ΔNp73 accumulation is p53 dependent. (A) ΔNp73 expression is mediated by p53. After transfection of HPV38-keratinocytes with indicated short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), p53 and ΔNp73 expression levels were determined by immunoblotting (WB, left panel) and reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR; right panel), respectively. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HFK, human foreskin keratinocyte. (B) p53 binds the ΔNp73 promoter in HPV38-keratinocytes. Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIPs) were performed on the indicated cell populations. Purified DNA from total lysate (input) and DNA co-immunoprecipitated from the control ChIP with no antibody (IP no Ab) or from the p53 immunoprecipitates (IP p53 Ab) were analysed by PCR using primers designed within the p73 p2 internal promoter.

Downregulation of ΔNp73 leads to re-activation of p53

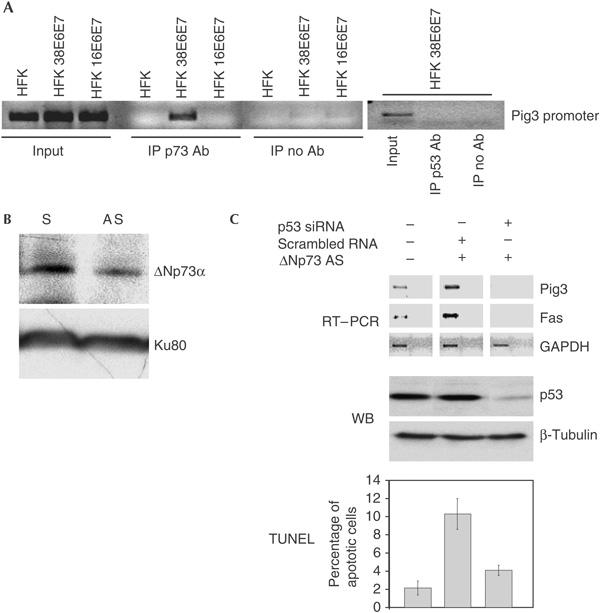

The lack of transcriptional activation of p53-regulated genes can be explained by the fact that ΔNp73α, which is transcriptionally inactive, may compete with p53 in binding p53-RE. ChIPs showed that an anti-p73 antibody was able to immunoprecipitate the Pig3 promoter only in HPV38-keratinocytes, but not in primary or HPV16-keratinocytes (Fig 5A). In contrast, no p53 was found to be associated with Pig3 promoter, further supporting this model (Fig 5A). As ΔNp73α is the only p73 isoform present in HPV38-keratinocytes, these findings provide evidence for ΔNp73α binding to the p53-RE of the Pig3 promoter. Indeed, downregulation of the endogenous levels of ΔNp73α in HPV38-keratinocytes using antisense oligonucleotides (Fig 5B) led to activation of p53-mediated gene expression and subsequent induction of apoptosis (Fig 5C), whereas ΔNp73 sense oligonucleotides had no significant effect (data not shown). Induction of p53-mediated gene expression and apoptosis was counteracted by p53 siRNA, indicating that both events induced by downregulation of ΔNp73α are mediated by p53 (Fig 5C). These data clearly show that ΔNp73α accumulation is directly involved in the alteration of p53 functions.

Figure 5.

Downregulation of ΔNp73 leads to re-activation of p53-regulated genes and apoptosis. (A) Pig3 promoter is bound to ΔNp73, but not to p53, in HPV38-keratinocytes. Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed as described in the legend of Fig 3C and Methods. p53 and p73 immunoprecipitates were analysed by PCR using Pig3 promoter primers. HFK, human foreskin keratinocyte. (B) Antisense oligonucleotide reduces ΔNp73 protein levels. ΔNp73 antisense oligonucleotides were transfected into HPV38- keratinocytes. ΔNp73α and Ku80 levels were detected by immunoblotting. AS, antisense; S, sense. (C) ΔNp73 downregulation induces p53-mediated apoptosis. HPV38-keratinocytes were transfected with different oligonucleotides as indicated. PCR was performed on complementary DNAs using indicated primers (reverse transcription–PCR (RT–PCR), top panel). Control PCR was performed using non-reverse transcribed RNA as template (far right of each panel). The p53 levels were determined by immunoblotting (WB, middle panel). Apoptosis was detected by TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) assay (bottom panel). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

HPV38 E6/E7 mice have high levels of p53 and ΔNp73

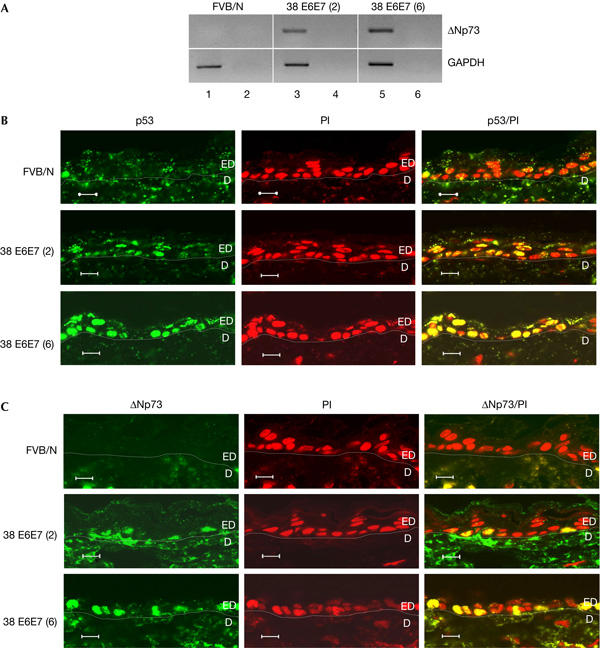

To confirm HPV38-mediated p53 inactivation in an in vivo model, we generated two transgenic mouse lines (2 and 6) expressing HPV38 E6 and E7 under the control of the bovine homologue of the human keratin 10 (K10) promoter. RT–PCR analysis showed that transgenic mouse line 2 expressed lower levels of HPV38 E6 and E7 than line 6 (Dong et al, 2005). Both lines of HPV38 transgenic mice clearly expressed ΔNp73, whereas no signal was detected in the RNA extracted from the epidermis of non-transgenic mice (Fig 6A). Immunoblot analysis of protein extracts prepared from frozen skin of FVB/N and transgenic mice showed the presence of higher p53 and ΔNp73 levels in transgenic mice than in FVB/N mice (data not shown). Immunofluorescence showed strong staining for p53 and ΔNp73 in the nucleus of epidermal keratinocytes from transgenic mice that was not detected in control animals (FVB/N; Fig 6B,C; supplementary Fig 2 online). The increase in levels of p53 and ΔNp73 detected by immunofluorescence was proportional to the increase in levels of HPV38 E6 and E7 expression in the two transgenic lines. We also observed that accumulation of p53 and ΔNp73 in transgenic mice correlated with the lack of transcriptional activation of p53-regulated genes (supplementary Fig 3 online). These findings confirm that the dependence of p53 and ΔNp73 on the levels of HPV38 E6 and E7 expression observed in human keratinocytes also occurs in vivo.

Figure 6.

p53 and ΔNp73 accumulate in keratinocytes of HPV38 E6/E7 transgenic mice. (A) ΔNp73 messenger RNA is expressed in the epidermis of HPV38 E6/E7 transgenic mice. PCR was performed on complementary DNA prepared from total RNA of non-transgenic and transgenic mice. As control, PCR was performed on non-reverse-transcribed RNA (lanes 2,4,6). GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (B,C) Accumulation of p53 and ΔNp73 in skin keratinocytes of HPV38 E6/E7 transgenic mice. Skin sections were prepared and stained with antibodies against p53 (C) or p73 (D) (green) and propidium iodide (PI, red) as described in Methods. Original photographs were taken at × 63 magnification. The derma (D) and epidermis (ED) are indicated. Scale bars, 10 μm (B,C).

Discussion

Here, we report for the first time that EV HPV types can alter the functions of p53. However, the mechanism of p53 inactivation mediated by HPV38 differs substantially from that mediated by HPV16. In fact, whereas HPV16 E6 promotes p53 degradation by the ubiquitin pathway, our data show that HPV38 E6 and E7 induce stabilization of wild-type p53, which in turn selectively activates transcription of ΔNp73. We also observed that TAp73 is downregulated in HPV38-keratinocytes. As ΔNp73 is able to antagonize p53 and p73 transcriptional function, the TAp73 downregulation is probably less relevant than ΔNp73 accumulation. The decrease of ΔNp73 levels resulted in transcriptional re-activation of p53-regulated genes encoding pro-apoptotic proteins and induction of apoptosis, indicating the importance of ΔNp73 accumulation in the alteration of p53 functions. Interestingly, it has been shown that ΔNp73α shows in vitro transforming activities (Petrenko et al, 2003) and is upregulated in many human cancers (Zaika et al, 2002; Concin et al, 2004).

Our study clearly identifies the role of ΔNp73 in altering the suppressive effects of p53; however, important questions remain to be answered. First, how do HPV38 E6 and/or E7 stabilize p53 and modulate its activity? Second, what is the molecular basis for the specific transcriptional activation of the ΔNp73 promoter by p53, and why is this activity not turned off by ΔNp73 itself after accumulation? We believe that the answers to these questions lie in the particular status of p53 on stabilization by HPV38 E6 and E7, which may significantly differ from that of p53 on stabilization in response to DNA damage. Overall, our results indicate that HPV38 E6 and E7, together, may induce p53 to adopt a specific activation status allowing preferential, high-affinity binding and transcriptional activation of the ΔNp73 promoter. Further studies are necessary to explain fully the molecular basis for these HPV38-induced events.

It has recently been shown that human cytomegalovirus also induces accumulation of ΔNp73α, but by a different mechanism from HPV38 (Allart et al, 2002; Terrasson et al, 2005). Independently of the mechanism, it is remarkable that two distinct viruses circumvent apoptotic pathways by increasing intracellular levels of ΔNp73α.

The targeting of p53 and pRb by HPV38 is similar to the activity of the mucosal carcinogenic HPV types, and supports the role of this and other related HPV types in human carcinogenesis. Our findings pave the way for new biological and epidemiological studies to assess the role of EV HPV types in NMSC and other epithelial tumours. In addition, they shed further light on the role of ΔNp73 as an important factor in transformation.

Methods

Generation of constructs. The following retroviral vectors were used: pBabe (described by Caldeira et al, 2003), pLXSN (Clontech, BD, Le Pont Claix, France) and pRetroSuper (Screeninc, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). ΔNp73α complementary DNA, kindly provided by Ute Moll (Stony Brook, US), was cloned in pBabe. For construction of HPV38 E7 shRNA, the oligonucleotide shown in supplementary Table 1 online and its complementary oligonucleotide were synthesized, annealed and cloned into pRetroSuper.

Cell culture procedures. Cell culture and retroviral infections. Cell cultures, antibiotic selections and generation of high-titre retroviral supernatants were carried out as previously described (Caldeira et al, 2003).

Gene silencing. Silencing of HPV38 E6 and E7 gene expression was achieved by the use of pRetroSuper expressing shRNA for the polycistronic E6 and E7 mRNA. p53 and ΔNp73 expression was silenced using the oligonucleotides listed in supplementary Table 1 online.

Determination of p53 half-life. To determine p53 half-life, general protein synthesis was blocked by addition of cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) to the culture medium, and cells were collected at different durations (0, 3 and 6 h). p53 levels were determined by immunoblotting.

Apoptotic assay. Apoptosis was estimated by the TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) assay using the In situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche, Meylan, France). Percentages of apoptotic cells were determined from the ratio between TUNEL- and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole-positive cells. About 800 cells were counted in four different fields under a fluorescence microscope.

Real-time and RT–PCR. Real-time PCR was carried out using the LightCycler® FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I kit (Roche). RT–PCR analyses were carried out as described previously (Caldeira et al, 2003). The primer sequences used for real-time and RT–PCR are indicated in supplementary Table 2 online.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation. Cells (5 × 105 keratinocytes) were processed according to the protocol of the Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay Kit (Upstate, Euromedex, Mundolsheim, France) using p53 or p73 antibody. DNA was extracted from the immunocomplexes and amplified by PCR using the primers listed in supplementary Table 2 online.

HPV38 transgenic mouse model. Transgenic mice expressing HPV38 E6/E7 genes under the regulation of a keratin 10 were generated, as described previously (Auewarakul et al, 1994; Dong et al, 2005). Skin of 8-week-old mice was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted using an Absolutely RNA Miniprep kit (Stratagene, Strasbourg, France). The use of experimental animals was approved by the internal IARC committee and experiments were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Immunofluorescence. Immunofluorescence staining of monolayer-cultured keratinocytes was carried out on formaldehyde-fixed cells. Immunofluorescence staining of mouse skin was carried out using the TSA™ fluorescence system (NEL754, Perkin-Elmer, Courtaboeuf, France). Skin sections of 8-week-old mice were prepared from paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed tissue, and epitopes were unmasked by heating. The percentages of positive cells were determined in 5–6 different fields of the epidermis, taking propidium iodide-stained cells as the total cell number. The two-sample t-test (Student's t-test) was used for statistical analysis of significance. A P-value of <0.01 was considered to be significant.

Antibodies. Immunoblot analyses were carried out using the following antibodies: anti-β-tubulin (TUB2.1; Sigma, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France), anti-Ku80 (Serotec, Cergy Saint-Christophe, France), anti-human p53 (NCL-CM1; Novocastra Laboratories Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK), anti-mouse p53 (NCL-CM5; Novocastra Laboratories), anti-phospho-p53 (Phospho-p53 Antibody Sampler kit; Cell Signaling, OZYME, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France), anti-p73 (Anti-p73 Ab-1; Calbiochem, Fontenay sous Bois Cedex, France) and (IMG-259; Imgenex, CliniSciences, Montrouge, France). Immunoprecipitation was performed using anti-p53 (NCL-CM1) or anti-p73 (Ab-1) antibody.

Immunofluorescence analysis was performed using anti-mouse p53 (NCL-CM5) or anti-p73 antibody (IMG-259; Imgenex) and fluorescein-tagged donkey anti-rabbit antibody (UP 264301; Uptima Interchim, Montluçon, France). Quantification of the protein signals was performed by scanning the immunoblot films using Fluor-S™ MultiImager and Quantity One-4.2.1 software (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France).

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/7400615-s1.ppt, http://www.nature.com/embor/journal/vaop/ncurrent/extref/7400615-s2.pdf).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures

Legends to Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Tables

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the members of our laboratory for their cooperation, Dr U. Moll for the ΔNp73α cDNA and Dr V. Bouvard, Dr U. Hasan, Dr J. Cheney and Dr L. Ringrose for a critical reading of the manuscript. This study was partially supported by La Ligue Contre le Cancer (Comité du Rhône).

References

- Allart S, Martin H, Detraves C, Terrasson J, Caput D, Davrinche C (2002) Human cytomegalovirus induces drug resistance and alteration of programmed cell death by accumulation of ΔN-p73α. J Biol Chem 277: 29063–29068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auewarakul P, Gissmann L, Cidarregui A (1994) Targeted expression of the E6 and E7 oncogenes of human papillomavirus type 16 in the epidermis of transgenic mice elicits generalized epidermal hyperplasia involving autocrine factors. Mol Cell Biol 14: 8250–8258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bode AM, Dong Z (2004) Post-translational modification of p53 in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 4: 793–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira S, Zehbe I, Accardi R, Malanchi I, Dong W, Giarre M, deVilliers E-M, Filotico R, Boukamp P, Tommasino M (2003) The E6 and E7 proteins of cutaneous human papillomavirus type 38 display transforming properties. J Virol 77: 2195–2206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira S, Filotico R, Accardi R, Zehbe I, Franceschi S, Tommasino M (2004) p53 mutations are common in human papillomavirus type 38-positive non-melanoma skin cancers. Cancer Lett 209: 119–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford GM, Smith JS, Plummer M, Munoz N, Franceschi S (2003) Human papillomavirus types in invasive cervical cancer worldwide: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 88: 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concin N et al. (2004) Transdominant ΔTAp73 isoforms are frequently up-regulated in ovarian cancer. Evidence for their role as epigenetic p53 inhibitors in vivo. Cancer Res 64: 2449–2460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H (2004) Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology 324: 17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W et al. (2005) Skin hyperproliferation and susceptibility to chemical carcinogenesis in transgenic mice expressing E6 and E7 of human papillomavirus type 38. J Virol 79: 14899–14908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levrero M, De Laurenzi V, Costanzo A, Gong J, Wang JY, Melino G (2000) The p53/p63/p73 family of transcription factors: overlapping and distinct functions. J Cell Sci 113: 1661–1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melino G, De Laurenzi V, Vousden KH (2002) p73: friend or foe in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 605–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko O, Zaika A, Moll UM (2003) ΔNp73 facilitates cell immortalization and cooperates with oncogenic Ras in cellular transformation in vivo. Mol Cell Biol 23: 5540–5555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister H (2003) Chapter 8: human papillomavirus and skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 31: 52–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrasson J, Allart S, Martin H, Lule J, Haddada H, Caput D, Davrinche C (2005) p73-dependent apoptosis through death receptor: impairment by human cytomegalovirus infection. Cancer Res 65: 2787–2794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaika AI, Slade N, Erster SH, Sansome C, Joseph TW, Pearl M, Chalas E, Moll UM (2002) ΔNp73, a dominant-negative inhibitor of wild-type p53 and TAp73, is up-regulated in human tumors. J Exp Med 196: 765–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- zur Hausen H (2002) Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer 2: 342–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures

Legends to Supplementary Figures and Supplementary Tables