Abstract

This study had a dual purpose of estimating population- and hospital-based caesarean section rates in 18 Arab countries and examining the association between these rates and important indicators of socioeconomic development. Data on caesarean section were based on the most recent population-based surveys undertaken in each country. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlation coefficients were used for the analysis. Specifically, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to analyze the associations between caesarean section rates and important population parameters. Results revealed that four Arab countries had population-based caesarean rates below 5%, while only three countries had rates above 15%. The remaining 11 countries had caesarean rates ranging between 5–15%. Higher hospital-based rates were reported for all countries. Differences in caesarean section rates between private and public hospitals were also noted. Highly significant associations were observed between population caesarean rates and female literacy, percentage urban, infant mortality rate, and the proportion of physicians per 100 000 people. The ‘caesarean section epidemic’ observed in countries of Latin America is not yet evident in the 18 Arab countries examined. Rather, emphasis should be on improving access to appropriate obstetrical interventions in case of complications in a number of countries where rates were well below 5%.

Keywords: caesarean section, socioeconomic development, health system, Arab countries

Introduction

The number of women having babies born by caesarean section is growing rapidly in both developed and developing countries (The Lancet 2000; Dosa 2001). Concern has been expressed at these growing rates (De Muylder 1993). Although safer caesarean section delivery may reduce maternal and infant morbidity and mortality, it remains a major surgical procedure with serious implications for the health of mother and child. Caesarean section deliveries carry high health risks including respiratory complications and neurological impairment of the newborn and long-term postpartum morbidity for the mother (Russell 1981; De Muylder 1993; Glazener et al. 1995; Belizan et al. 1999). Furthermore, caesarean deliveries require the use of more medical and healthcare resources compared with normal deliveries, becoming as such a real burden to health systems working with limited budgets (De Muylder 1993; Glazener et al. 1995; Belizan et al. 1999). An increasing number of studies have been conducted on this topic, particularly in countries undergoing rapid demographic and health transitions such as South American countries, where the incidence of caesarean section is very high even compared with rates in developed societies (Belizan et al. 1999; Savage 2000).

Little is known about the prevalence of caesarean deliveries in the Arab world, a region that has been undergoing salient demographic changes. There has been some available evidence for a few of the countries in this region, and even for these countries, studies are largely based on hospital-based samples (Chattopadhyay et al. 1987; Guirguis and Al-Saleh 1991; Elhag et al. 1994; Hughes and Morrison 1994; Ziadeh and Abu-Heija 1995; Abu-Heija and Zayed 1998; Abu-Heija et al. 1999; Akasheh and Amarin 2000; Khayat and Campbell 2000; Mesleh et al. 2000; Ziadeh et al. 2000; Mesleh et al. 2001). This is surprising given the availability of national-level micro-data from the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) and the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) programmes for several countries in the region.

At the turn of the 21st century, the Arab region is entering an era of dramatic demographic shifts with obvious health consequences. Declining fertility, now underway in most countries, is one of the most significant phenomena in the region today. The fertility decline is likely to result in improved maternal and child health (Cook 1987) as well as a substantially changed age structure and distribution, with gradually fewer dependants. As countries move through the demographic transition, important questions arise about the effect of this phenomenon on maternal health, the well-being of families and other issues of policy concern. Yet, the demographic changes currently underway in the region are far from uniform. As a result of the demographic transition, the demographic and socioeconomic gaps between different countries and areas within countries seem wider than ever (UNDP and AFESD 2002). Furthermore, a quick look at the onset of demographic and health transitions reveals little correspondence with socioeconomic development in this context. The presence of oil-rich countries and prolonged political conflict and wars contribute to these demographic and health anomalies (Omran and Roudi 1993).

This study has a dual purpose of (1) estimating the prevalence of caesarean section in 18 Arab countries and (2) correlating these with important demographic, socioeconomic and health characteristics of the populations under study. Cook (1987) argued that maternal health and obstetric care should improve in this region with increased urbanization, education and literacy. Establishing the prevalence and correlates of caesarean delivery in this region is of considerable policy concern. According to UNICEF et al. (1997), rates of caesarean section below 5% seem to be associated with gaps in obstetric care leading as such to poor health outcomes for mother and child, whereas rates over 15% do not seem to improve either maternal or infant health. Is there a need to increase or reduce the caesarean delivery rates towards the ‘acceptable’ range in the countries under examination? What is the potential impact of demographic transition and/or socioeconomic development on rates of caesarean section delivery in this region?

Data and methods

Given the purpose of our study, we sought (1) information about the prevalence of caesarean section, as well as (2) data on the structural context (demographic and socioeconomic environment) of countries in which caesarean section took place. In both cases, we relied on secondary, or otherwise published, sources. To obtain latest data for each country included in the study, we contacted the DHS program, Population Research Unit of the Arab League, and Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

Our main sources of data on caesarean section were the most recent population-based surveys undertaken in each of the 18 Arab countries under examination. Here, we relied on various data sources. First, micro-data from the DHS program were used for Egypt (EDHS 2000), Yemen (YDHS 1997) and Mauritania (ORC Macro 2003). For Jordan (JDHS 1997), we used data from the published report. Second, the 1996 Demographic Survey in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, designed and implemented by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, was used to calculate estimates for the Palestinian areas. Finally, data for the remaining countries were obtained from published reports of national surveys carried out by PAPCHILD of the League of Arab States and UNFPA. Published reports from the Arab Maternal and Child Health Survey programme were used for Algeria (AMCHS 1993), Lebanon (LMCHS 1996), Libya (ALMCHS 1995), Morocco (MMCHS 1999), Sudan (SMCHS 1993) and Tunisia (TMCHS 1994–5), countries where national micro-data could not be accessed. Likewise, the Gulf Family Health Survey reports were used for information about Bahrain (BFHS 1995), Kuwait (KFHS 1996), Oman (OFHS 1995), Qatar (QFHS 1998), Saudi Arabia (SAFHS 1996) and United Arab Emirates (UAE) (EFHS 1995). For Syria (SARMCHS 2001), we used information obtained from the first national survey carried out by the Pan Arab Project for Family Health (PAPFAM) of the League of Arab States which was originally developed out of the PAPCHILD survey and it aims to provide information on Arab family health.

All of these national surveys used largely standardized instruments and similar methodologies, thus enhancing comparability of data between countries and over time. Table 1 provides information about sample characteristics of the surveys in question.

Table 1.

Sources of data on caesarean section

| Country | National survey | Year | No. of households interviewed | No. of women interviewed | No. of births | Response rate (%) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | AMCHS | 1993 | 6 694 | 5 881 | 5 288 | 93.7 | Ministry of Health and Population [Algeria] (1994) |

| Bahrain | BFHS | 1995 | 4 166 | 3 725 | 3 120 | 94.0 | Naseeb and Farid (2000) |

| Egypt | EDHS | 2000 | 16 957 | 15 573 | 11 467 | 99.1 | Micro data |

| Jordan | JDHS | 1997 | 7 335 | 5 548 | 6 360 | 96.4 | Department of Statistics [Jordan] (1998) |

| Kuwait | KFHS | 1996 | 3 673 | 3 453 | 3 514 | 91.0 | Alnesef et al. (2000) |

| Lebanon | LMCHS | 1996 | 4 600 | 3 317 | 2 156 | 93.0 | Ministry of Public Health [Lebanon] (1998) |

| Libya | ALMCHS | 1995 | 6 312 | 5 164 | 5 348 | 95.0 | The General People’s Committee forHealth and Social Insurance [Libya] (1996) |

| Mauritania | MDHS | 2000–1 | 6 149 | 7 728 | 5 088 | 97.6 | ORC Macro (2003) |

| Morocco | MMCHS | 1999 | 6 000 | 5 311 | 3 815 | 95.0 | Ministry of Health [Morocco] (2000) |

| Oman | OFHS | 1995 | 6 304 | 6 405 | 9 033 | 94.7 | Sulaiman et al. (2000) |

| Palestine | PDS | 1996 | 3 722 | 3 564 | 4 630 | 94.6 | Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (1997) |

| Qatar | QFHS | 1998 | 4 207 | 3 787 | 3 775 | 83.0 | Al-Jaber and Farid (2000) |

| Saudi Arabia | SFHS | 1996 | 10 510 | 8 894 | 10 831 | 94.5 | Khoja and Farid (2000) |

| Sudan | SMCHS | 1993 | 5 320 | 4 869 | 4 585 | 96.6 | Ministry of Public Health [Sudan] (1995) |

| Syria | SRMCHS | 2001 | 9 500 | 6 953 | 4 038 | 95.0 | Central Bureau of Statistics [Syria] (2002) |

| Tunisia | TMCHS | 1994–5 | 6 308 | 4 920 | 3 783 | 96.3 | Ministry of Public Health [Tunisia] (1996) |

| UAE | EFHS | 1995 | 5 822 | 5 745 | 6 285 | 97.0 | Fikri and Farid (2000) |

| Yemen | YDMCHS | 1997 | 10 701 | 10 414 | 12 451 | 95.8 | Micro data |

In all these surveys, women were asked the same questions about their pregnancies during the past 5 years before the survey. Specifically, mothers were asked if they had any pregnancy during the 5 years preceding the survey, and about complications during delivery if any. Among the various complications reported, we focused on caesarean section deliveries.

Our sources of data for national-level demographic and socioeconomic indicators were the UN PRED (2002) and WHO (2002) cross-national databases for all the countries included here except for the Palestinian areas. Data for the Palestinian areas were obtained directly from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2002) in Ramallah. The UN PRED is a machine-readable database prepared by the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. This database contains national, comparative indicators on various aspects of population, resources, environment and development for 228 countries or areas of the world. Population estimates and projections were produced by the Population Division of the UN. Other data were contributed directly, or indirectly from published sources, by the various specialized UN agencies including FAO, ILO, UNEP, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNICEF and WHO, and the World Bank. For consistency purposes, the WHO database, United Nations specialized agency for health, was used to obtain information on health personnel for countries in the region. Estimates of health personnel were made by the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (WHO 2002). There is some variability in the quality of the data used in these databases (UN PRED 2002; WHO 2002). According to the UN, ‘despite the considerable efforts of international organisations to collect, process and disseminate social and economic statistics and to standardize definitions and data collection methods, limitations remain in the data coverage, consistency and comparability of data across time and between countries’ (UN PRED 2002). To our knowledge, the country level data provided by UN agencies remain the best available for conducting cross-national studies.

The indicators obtained from these two machine-readable databases and from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics were chosen based on their proximity to the year of the survey in question. In cases where we could not obtain macro data for the same year of the survey date, we used available data for the year closest to the survey date. We relied on a set of widely used development indicators, including percentage of the population that is urban, adult female literacy rate, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in US$ adjusted for purchasing power parities, total fertility rate (TFR), percentage of women having institutional deliveries, proportion of physicians per 100 000 people, infant mortality rate (IMR) and maternal mortality ratio (MMR). Taken together, these indicators permit a preliminary examination of the links between caesarean section prevalence in a country and its wider socioeconomic context. The Appendix provides a brief summary of the data sources, variables used and their definition.

Appendix.

List of variables used

| Variable | Unit | Definition of variable |

|---|---|---|

| Total population1 | Thousands | Mid-year de facto population estimated by the Population Division/DESA of the United Nations Secretariat. Estimates and medium-variant projections provided by United Nations. |

| Percentage urban1 | Percentage | Estimates of the percentage of total population residing in urban areas provided by United Nations. ‘Urban’ is defined according to the national census definition used in the latest available population census in each country. |

| Adult literacy rate, female1 | Percentage | Female adult literacy refers to the proportion of the female population aged 15+ years who can, with understanding, both read and write a short simple statement on everyday life. Estimates provided by UNESCO. |

| Total fertility rate1 | Children per woman | Average number of children that would be born to a woman in her lifetime, if she were to pass through her childbearing years experiencing the age-specific fertility rates for a given period. Estimates and medium-variant projections provided by United Nations. |

| Infant mortality rate1 | Deaths per 1000 live births | Number of deaths of infants under 1 year of age per 1000 live births in a given year. It shows the probability of a newborn dying before reaching his first birthday. Figures are quinquennial estimates and medium-variant projections provide by United Nations. |

| Maternal mortality ratio1 | Deaths per 100 000 live births | The maternal mortality ratio is the number of maternal deaths over a year per 100 000 live births in that year. |

| GDP per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP)1 | Current international dollars | GDP per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) are GDP estimates based on the purchasing power of currencies rather than on current exchange rates. These estimates are a blend of extrapolated and regression-based numbers provided by the World Bank. |

| Health personnel2 | Rate per 100 000 people | Number of physicians, nurses, midwives, dentists, pharmacists per 100 000 population per year provided by WHO. |

Source: UN PRED (2002);

For the analysis, both population and hospital-based caesarean section prevalence rates for Arab countries were (if appropriate) estimated and documented. Estimation was done for 12 countries that lacked data on population caesarean section. We used information from published survey reports on total number of deliveries, proportion of hospital births and caesarean section rates for women with births in the time period covered by these surveys. In estimating the rates, we made the assumption that the proportion of caesarean section deliveries at home is nil in these countries, as had been the case in the countries where this information was readily available. We divided the number of caesarean section deliveries (given) by the total number of births irrespective of place of delivery (given). Belizan et al. (1999) used a similar methodology in their study in Latin America. To increase confidence in the estimates, we compared the caesarean rates of countries for which we had the micro-data sets with the rates obtained from their published reports. The results were almost identical. The associations between caesarean section rates and the demographic, socioeconomic and health indicators were analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. The analysis reported here was undertaken by the program Stata 7 for Windows (2001).

Results

Table 2 presents information on important demographic, socioeconomic and health indicators for 18 countries in the Arab region. Clearly, this region is quite diverse. For convenience purposes, the countries examined were classified into four groups based on their socioeconomic profiles. The first group included the Gulf countries and Libya, characterized by high GDPs, high rates of urbanization, impressively low infant and maternal mortality rates, and high rates of institutional deliveries. Some of these countries could be characterized demographically as pre-transitional owing to still high fertility rates: Saudi Arabia and Oman had an estimated TFR of 6.2 and 5.9 children, respectively. Other Gulf countries such as Bahrain and UAE could be classified instead as transitional countries. The second set of countries included Lebanon and Tunisia. These were found to be upper middle-income countries, with very low fertility rates and infant mortality rates, high female literacy, and high institutional delivery rates. With TFR approaching replacement levels, Lebanon and Tunisia could be considered as forerunners in the fertility transition. The third category of countries included Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Palestine and Syria, lower and upper middle-income countries, characterized mostly by high urbanization, female literacy rates, accelerating though still modest fertility transition (save Palestine), and satisfactory socioeconomic and health conditions. The last category of countries included Mauritania, Sudan and Yemen. These were economically poor countries characterized by low rates of urbanization, female literacy and doctors per 100 000 people, and excessively high TFR, IMR and MMR.

Table 2.

Demographic, social, economic and health indicators for 18 Arab countries

| Caesarean section3

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Population1 (1000s) | Urban Population1 (%) | Female Literacy1 (%) | GDP (PPP)1 (US$) | TFR1 (children per woman) | IMR1 (per 1000 live births) | Year | MMR1 (per100 000 live births) | Year | No. of doctors2 (per 100 000 people) | Year | Institutional deliveries3 (%) | Population (%) | Hospital (%) | Year |

| Algeria | 27 655 | 56.6 | 49.4 | 4 697 | 3.3 | 50.0 | 1995 | 148 | 1995 | 84.6 | 1995 | 76.1 | 4.9 | 6.4 | 1993 |

| Bahrain | 573 | 90.3 | 79.4 | 13 803 | 2.6 | 16.0 | 1995 | 38 | 1995 | 100.0 | 1997 | 98.2 | 16.0 | 16.3 | 1995 |

| Egypt | 67 884 | 45.2 | 43.9 | 3 041 | 3.4 | 51.0 | 2000 | 174 | 1995 | 202.0 | 1996 | 48.2 | 10.3 | 20.9 | 2000 |

| Jordan | 4 249 | 71.4 | 79.3 | 3 347 | 4.7 | 27.0 | 1995 | 41 | 1995 | 166.0 | 1997 | 93.1 | 10.5 | 11.3 | 1997 |

| Kuwait | 1 691 | 97.0 | 76.4 | 18 3502 | 2.9 | 12.0 | 1995 | 25 | 1995 | 189.0 | 1997 | 97.5 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 1996 |

| Lebanon | 3 169 | 87.5 | 76.9 | 3 964 | 2.3 | 20.0 | 1995 | 127 | 1995 | 210.0 | 1997 | 87.9 | 15.1 | 17.2 | 1995–6 |

| Libya | 4 755 | 85.3 | 60.4 | 12 0982 | 3.8 | 28.0 | 1995 | 117 | 1995 | 128.0 | 1997 | 94.0 | 7.2 | 7.6 | 1995 |

| Mauritania | 2 665 | 57.7 | 32.1 | 1 563 | 6.0 | 97.0 | 2000 | 874 | 1995 | 13.8 | 1995 | 48.5 | 3.2 | 6.6 | 2000–1 |

| Morocco | 29 878 | 56.1 | 36.1 | 3 305 | 3.4 | 52.0 | 2000 | 390 | 1995 | 46.0 | 1997 | 45.7 | 7.0 | 15.3 | 1999 |

| Oman | 2 154 | 75.6 | 50.5 | 15 8082 | 5.9 | 27.0 | 1995 | 115 | 1995 | 133.0 | 1998 | 88.7 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 1995 |

| Palestine4 | 3 191 | 67.45 | 83.9 | 1 537 | 5.9 | 25.5 | 1995 | 74 | 1995 | – | – | 89.8 | 6.1 | 7.0 | 1996 |

| Qatar | 565 | 92.5 | 83.1 | 26 3042 | 3.7 | 14.0 | 2000 | 41 | 1995 | 126.0 | 1996 | 97.8 | 15.9 | 16.3 | 1998 |

| Saudi Arabia | 17 091 | 82.8 | 59.7 | 10 766 | 6.2 | 25.0 | 1995 | 23 | 1995 | 166.0 | 1997 | 91.0 | 8.1 | 8.9 | 1996 |

| Sudan | 27 213 | 31.3 | 38.8 | 1 331 | 4.9 | 86.0 | 1995 | 1 452 | 1995 | 9.0 | 1996 | 18.2 | 3.7 | 20.4 | 1993 |

| Syria | 16 189 | 54.5 | 60.5 | 2 892 | 4.0 | 27.0 | 2000 | 195 | 1995 | 144.0 | 1998 | 55.4 | 14.8 | – | 2000 |

| Tunisia | 8 943 | 61.9 | 53.3 | 4 870 | 2.3 | 30.0 | 1995 | 69 | 1995 | 70.0 | 1997 | 80.0 | 8.0 | 10.2 | 1995 |

| UAE | 2 352 | 83.8 | 74.3 | 19 935 | 3.2 | 12.0 | 1995 | 30 | 1995 | 181.0 | 1997 | 99.1 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 1995 |

| Yemen | 14 895 | 23.6 | 18.4 | 719 | 7.6 | 74.0 | 1995 | 850 | 1995 | 23.0 | 1996 | 15.5 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 1997 |

Population- and hospital-based caesarean section rates for the 18 Arab countries are also reported in Table 2. Yemen, Mauritania, Sudan and Algeria had population caesarean section rates below 5%. Palestine, Oman, Morocco, Libya, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait and Syria had caesarean rates ranging between 5–15%. Only three countries had rates above 15%, namely, Lebanon, Qatar and Bahrain. Eleven countries had hospital-based caesarean rates below 15%. The rest of the countries had rates ranging between 15.3% and 27.1%. A country like Sudan, with a population caesarean rate below 5%, was found to exhibit a hospital-based caesarean section rate of 20.4%, one of the highest in this category for the region. Information by type of hospital for delivery was available for only five countries in the region. The proportion of hospital-based caesarean rates was found to be significantly higher for women delivering in the private sector (22.6%) compared with those delivering in the public (19.0%) in Egypt. Older datasets for Jordan (JDHS 1990) and Morocco (MDHS 1995) also revealed higher caesarean rates in private hospitals. However, the converse was true for Yemen (4.7% and 6.6%) and Palestine (9.0% and 8.7%), where caesarean rates where higher in public hospitals.

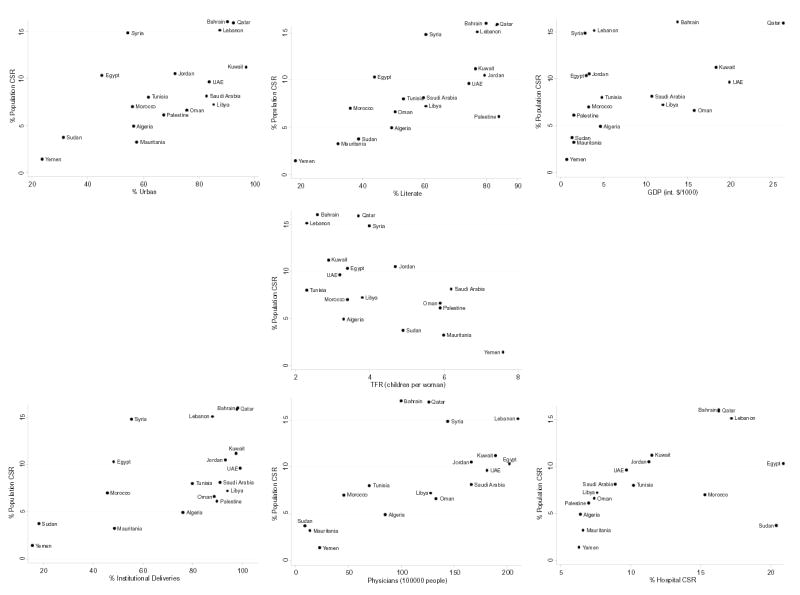

Figure 1 shows the association of important socioeconomic and demographic characteristics with population caesarean section rates. Significant associations were found between rates of caesarean section and urban population (rs = 0.637; n = 18; p < 0.01), proportion of adult female literacy (rs = 0.715; n = 18; p < 0.01), GDP per capita purchasing power (rs = 0.560; n = 18; p < 0.05) and TFR (rs = −0.585; n = 18; p < 0.05). In fact, Yemen and Sudan, poor countries with low levels of urbanization and adult female literacy rates and high TFR, showed some of the lowest population caesarean rates in the region. Mauritania had a similar pattern despite its relatively higher level of urbanization. On the other hand, richer countries like Bahrain and Qatar, with their high levels of urbanization and female adult literacy rates and their relatively lower TFR, exhibited the highest caesarean rates. Egypt provided an exception to this rule. It was found to exhibit higher rates of caesarean delivery than Oman, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, Libya and UAE, all with better socioeconomic profiles. Despite its relatively modest socio-demographic profile, Syria was found to have caesarean rates similar to those of Lebanon, Qatar and Bahrain. Also interesting is the case of Kuwait. Even though it showed a better overall socioeconomic profile than Lebanon (except for its higher TFR), it was found to have a lower percentage of caesarean deliveries. The rest of the countries were found to follow to a great extent the aforementioned trend.

Figure 1.

Bivariate associations between population-based caesarean section rates and indicators: Arab countries

A significant association was also found between population-based caesarean section and institutional deliveries, as shown in Figure 1 (rs = 0.614; n = 18; p < 0.01). Arab countries with caesarean rates below 5% showed lower proportions of hospital deliveries. Yemen and Bahrain could best illustrate this. Yemen, with the lowest institutional delivery rate in the region (15.5%), exhibited also the lowest caesarean section rate (1.4%), compared with Bahrain which had an almost universal hospital delivery rate and a caesarean section rate above 15%.

There were anomalies. With less than 50% of births delivered in hospitals, Egypt had a caesarean rate higher than countries like Algeria, Tunisia, Oman, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Libya and UAE, where proportions of hospital births were well above 70%. This pattern was observed in the case of Syria as well. Similarly, the association between caesarean rates and proportion of physicians (rs = 0.646; n = 17; p < 0.01) was positive and significant (Figure 1). A statistically significant, positive relation was also found between caesarean rates at the population- and the hospital-based levels (rs = 0.651; n = 17; p < 0.01). Bahrain, Qatar and Lebanon, all with high population caesarean rates, also had the highest rates at the hospital levels. The converse was true for Yemen, Mauritania and Algeria. Among the most interesting exceptions were the cases of Egypt and Sudan, with hospital caesarean section rates being two- and six-times higher, respectively, than their population rates.

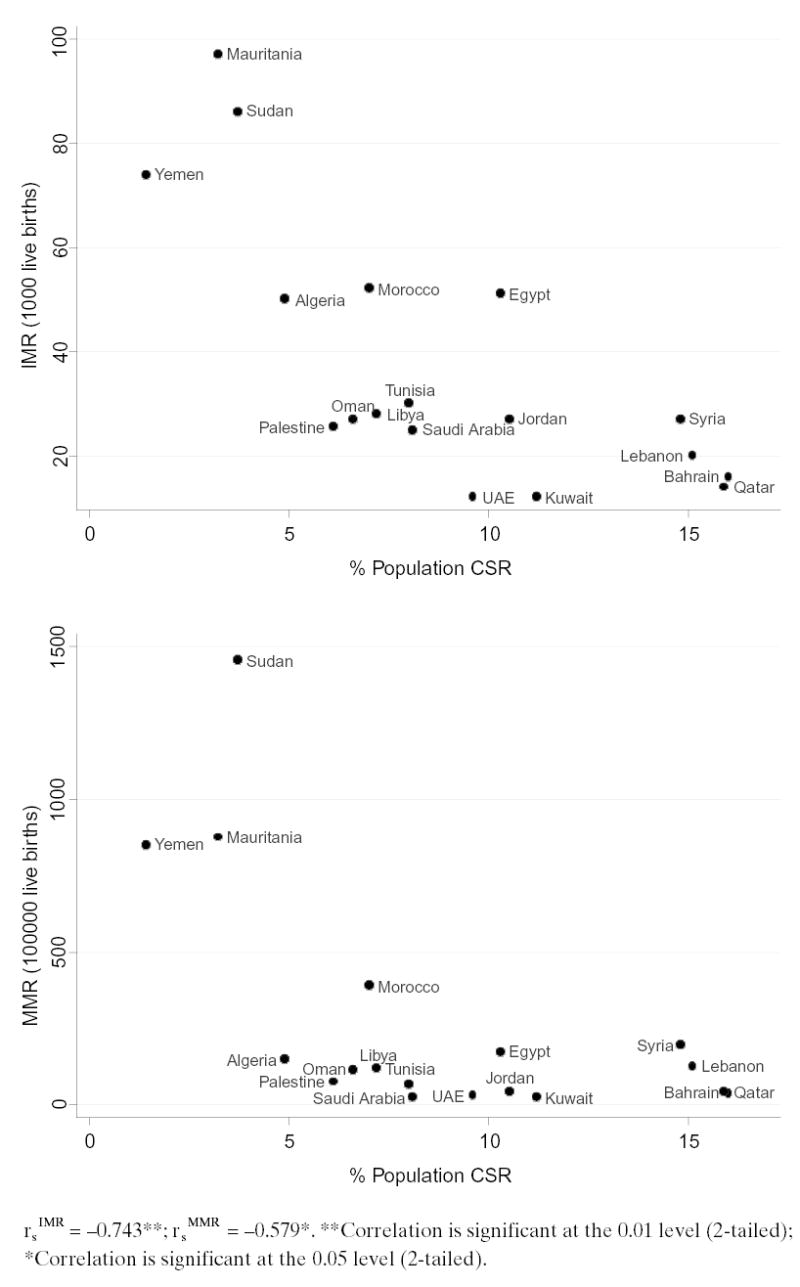

Figure 2 shows a strong, negative association between population caesarean section rate and IMR and MMR. Yemen, Mauritania and Sudan with high IMR and MMR had the lowest rates of caesarean section at the population level. Again, Bahrain and Qatar, with their low IMR and MMR, exhibited the highest population-based caesarean section rates in the region. Despite having a relatively high maternal mortality rate in comparison with Bahrain and Qatar, Lebanon and Syria seemed to fit with this last group of transitional countries. UAE and Saudi Arabia could be regarded as exceptions in this regard. Despite having very low IMR and MMR, they showed lower rates of caesarean section when compared with countries with relatively modest health indicators like Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon. Although Kuwait had impressive decreases in IMR and MMR, it showed caesarean rates lower than countries with similar characteristics like Bahrain and Qatar, or worse-off countries like Lebanon and Syria. Countries like Jordan, Tunisia, Libya, Morocco, Palestine and Algeria showed caesarean rates in great conformity with their overall IMR and MMR.

Figure 2.

Bivariate association between population caesarean rates and mortality outcomes: Arab countries

Discussion and conclusions

Our results show that the Arab countries exhibited great disparities in their population-based caesarean section rates. These differences were explained to a great extent by the countries’ demographic transition and socioeconomic development. The strongest associations were found between the prevalence of population caesarean section rate and female literacy, percentage urban, IMR and the proportion of physicians per 100 000 people. Clearly, countries with better socio-demographic and health parameters, as well as better off economically, have been moving more quickly towards a medicalization of maternal health care, through specialized, high technology models.

Although higher caesarean section rates were found to be associated with better health care and higher levels of socioeconomic development, there were exceptions. For example, Saudi Arabia and Oman, being pronatalist countries with high fertility rates, enjoyed high GDPs, levels of urbanization and female literacy rates, and impressive improvements in infant and maternal mortality rates. And yet, they had average rates of caesarean section. At the other extreme were Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon with rather high caesarean rates for their overall levels of development. This raises the question of whether these countries have been undergoing over-medicalization of delivery or the ‘liberal’ use of the caesarean section procedure in recent years.

All in all, however, the findings reveal that the ‘caesarean section epidemic’ (Sakala 1993) found in countries of Latin America is not yet evident in the Arab region. Rather, efforts need to be undertaken to promote better access to caesarean section in some countries. Specifically, Yemen, Mauritania, Sudan and Algeria had caesarean rates well below 5%, indicating possible problems in accessing appropriate obstetrical interventions in case of complications during delivery. These countries are largely rural, exhibiting great regional disparities in health conditions and socioeconomic development. Access to appropriate obstetric care in remote areas in these countries may help reduce both infant and maternal mortality rates encountered in these areas. Again, however, as Buekens et al. (2003, p. 136) put it, ‘any support programs [in this direction] should be carefully designed to avoid the risk of simultaneously increasing unnecessary caesarean section and iatrogenic morbidity and mortality.’

Clear differences between population- and hospital-based caesarean section rates were also documented, especially in countries with very low overall rates of hospital deliveries. This may reflect differences in accessibility to maternal health services in some cases, or the misuse of scarce resources in others. High rates of caesarean section at the hospital level compared with only modest rates at the population level, as was the case in Sudan, pose questions regarding the proper use of this surgical procedure.

Differences in caesarean rates between private and public hospitals were also evident in some countries. Bearing these results in mind, we cannot but wonder whether the higher proportions of caesarean section deliveries in private hospitals are really a reflection of physicians’ efforts to ensure better outcomes in case of complications, or whether their decisions are affected by profitability or factors relating to physicians’ convenience. Although we lack systematic information on health care financing by place and mode of delivery for the countries under study, some general observations are in order. First, obstetricians are generally paid more for a caesarean delivery than for a vaginal delivery. However, payments differ greatly between countries and between hospital types within the same country. Secondly, institutional deliveries are handled mostly by physicians, but deliveries by trained nurses/midwives are also common. Again, differences exist between and within countries. For example, a country like Egypt, characterized by a shortage in trained nurses/midwives, has a higher proportion of institutional deliveries handled by doctors (Eltigani 2000). Data for Jordan reveal that assistance during delivery in a hospital setting varies greatly, with about 65% of deliveries being assisted by a doctor and 32% by a trained nurse/midwife (Department of Statistics [Jordan] 1998). Furthermore, doctors are more likely to assist births to educated women, to women in urban areas and to women who received more antenatal care (Department of Statistics [Jordan] 1998). The opposite is true for Syria and Palestine, where a significant proportion of institutional deliveries are handled by trained nurses/midwives (Central Bureau of Statistics [Syria] 2002; Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics 2002).

Thirdly, the mode of payment of physicians in these countries depends greatly on the setting and the availability of health insurance in each country. In most cases, there are out-of-pocket payments if the women are not insured or are only partially insured. Although some countries have only public insurance coverage (e.g. Syria), most settings have both private and public sectors providing health insurance. Further research is needed to establish the precise causes of hospital-based caesarean section, and to unmask the mechanisms underlying the practice in private and public sector hospitals in the region and beyond. A detailed comparison of health care financing in these countries by type of hospital may provide answers to some of the observed differences.

When considering the implications of our findings, the usual shortcomings of the study design need to be acknowledged. This is an ecological study based on comparative national-level data collected at different points in time in different countries. As such, it may explore hypotheses but it cannot explain associations. Hence, the study relied on bivariate associations rather than multivariate analyses. Given the small sample size and the data at hand, we chose to use correlation analysis between caesarean rates on the one hand and selected development and health indicators on the other. Confirmation of our findings using multivariate statistical techniques and better, or otherwise more current, development indicators will be necessary.

Our study may have several other related limitations. One major weakness pertains to the quality of the data used. The data used for the national-level demographic and socioeconomic indicators varies from source to source, despite efforts by the UN agencies to ensure comparability (UN PRED 2002). Problems of obtaining data at the same point in time for all indicators under examination may have also affected the validity or the comparability between the countries under examination. Nevertheless, the UN agencies provide the most recent and comparable statistical series at the national level – there is simply no other, more credible, source of demographic and health characteristics of countries. Another weakness relates to the estimation of population-based caesarean section rates for some countries. Owing to the lack of appropriate data, we had to estimate caesarean rates using information from published reports for some countries. Here, we assumed that non-hospital deliveries were all vaginal deliveries (Belizan et al. 1999). Although our assumption may be a valid one, the exact correspondence between our estimates and the actual figures remains difficult to assess. Finally, we were not able to consider another set of factors related to health care financing and profitability that might have accounted for some of the observed associations between caesarean section delivery and development indicators.

This study has left many other important questions unanswered. The Arab region is clearly diverse in terms of maternal health and obstetric care, as demonstrated in this profile of caesarean section delivery, but intra-regional variations mask important intra-national differences in maternal health outcomes, including childbirth. It is unclear, for example, whether the variations observed among countries are due to within country differentials in access to health care or to overall ‘deficit’ in health care coverage. What are the precise socioeconomic and demographic factors contributing to the deficit (if any) in utilizing maternal health care in specific contexts? Can low rates of caesarean section delivery be attributed to cultural preferences for traditional or otherwise home-based delivery in some countries? To what extent are the high levels of caesarean section observed in countries like Egypt, Syria and Lebanon due to the development of policy concerns and heightened awareness about maternal mortality and morbidity? Do levels of caesarean section reflect the recent trend towards privatization or otherwise lack of regulation of the health sector in the region (Campbell and Lewando-Hundt 1998)? Answers to these and similar policy-relevant questions require the use of carefully designed qualitative studies, as well as the utilization of micro survey data, which have become recently available.

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of a larger regional research project on Changing Childbirth in the Arab Region, sponsored by the Center for Research on Population and Health at the American University of Beirut with support from the Wellcome Trust and Mellon Foundation.

Footnotes

Biographies

Rozzet Jurdi, MS (American University of Beirut), is trained in demographic techniques and statistics. She is currently a Researcher in the Center for Research on Population and Health in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the American University of Beirut. She is presently engaged in two projects namely, Changing Childbirth Practices in the Arab Region and Provider’s Study on Sexual Health in Lebanon. Her research interests include woman’s obstetric care and experience, reproductive morbidity, infertility and other issues of public health concern.

Marwan Khawaja, Ph.D. (Cornell University), is an Associate Professor of Population Health and Director of the Center for Research on Population and Health in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the American University of Beirut. He is currently coordinating a major research initiative on displacement, impoverishment and urban health in outer Beirut, including a large household survey undertaken in 2002. He has published numerous research reports and articles.

References

- Abu-Heija A, Zayed F. Primary and repeat caesarean sections: comparison of indications. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;18:432–4. doi: 10.1080/01443619866723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Heija AT, Jallad MF, Abukteish F. Obstetrics and perinatal outcome of pregnancies after the age of 45. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;19:486–8. doi: 10.1080/01443619964265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akasheh HF, Amarin V. Caesarean sections at Queen Alia Military Hospital, Jordan: a six-year review. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2000;6:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jaber KA, Farid SM. 2000. Qatar family health survey Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey.

- Alnesef Y, Al-Rashoud R, Farid SM. 2000. Kuwait family health survey Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey.

- Belizan JM, Althabe F, Barros FC, Alexander S. Rates and implications of caesarean section in Latin America: ecological study. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:1397–402. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7222.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buekens P, Curtis S, Alayon S. Demographic and health surveys: caesarean section rates in sub-Saharan Africa. British Medical Journal. 2003;326:136. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7381.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell O, Lewando-Hundt G. 1998. Profiling maternal health in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria. In: Barlow R, Brown JW (ed). Reproductive health and infectious disease in the Middle East Hampshire: Ashgate, pp. 25–48.

- Central Bureau of Statistics [Syria]. 2002. Family health survey in the Syrian Arab Republic: summary report Syrian Arab Republic and the Pan Arab Project for Family Health (PAPFAM) of the League of Arab States.

- Chattopadhyay SK, Sengupta PB, Edrees YB, Lambourne A. Caesarean section: changing patterns in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1987;25:387–94. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(87)90345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook R. Current knowledge and future trends in maternal and child health in the Middle East. Journal of Tropical Paediatrics. 1987;33:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Muylder X. Caesarean sections in developing countries: some considerations. Health Policy and Planning. 1993;8:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics [Jordan]. 1998. Population and family health survey 1997 Demographic and Health Surveys Macro International Inc. Calverton, Maryland USA.

- Dosa L. Caesarean section delivery, an increasingly popular option. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2001;79:1173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhag BI, Milaat WA, Taylouni ER. An audit of caesarean section among Saudi females in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Egypt Public Health Association. 1994;69:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltigani E. 2002. Standard of living and utilization of maternal health care services in Egypt. Social Research Center, American University in Cairo. [Unpublished draft].

- Fikri M, Farid SM. 2000. United Arab Emirates family health survey Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey.

- Guirguis W, Al-Saleh K. Caesarean section in Kuwait, 1983 through 1988. Journal of Egypt Public Health Association. 1991;66:451–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PF, Morrison J. Pregnancy outcome data in a UAE population: what can they tell us? Asia Oceania Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;20:183–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1994.tb00447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khayat R, Campbell O. Hospital practices in maternity wards in Lebanon. Health Policy and Planning. 2000;15:270–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoja TA, Farid SM. 2000. Saudi Arabia family health survey Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey.

- The Lancet. Editorial: Caesarean section on the rise. The Lancet. 2000;356:1697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesleh RA, Al Naim M, Krimly A. Pregnancy outcomes of patients with previous four or more caesarean sections. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;21:355–7. doi: 10.1080/01443610120059879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesleh RA, Asiri F, Al-Naim M. Caesarean section in the primigravid. Saudi Medical Journal. 2000;21:957–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health [Morocco]. 2000. Moroccan maternal and child health survey: principal report The Republic of Morocco and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States.

- Ministry of Health and Population [Algeria]. 1994. Algeria maternal and child health survey: principal report The Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States.

- Ministry of Public Health [Lebanon]. 1998. Lebanon maternal and child health survey: principal report Republic of Lebanon and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States.

- Ministry of Public Health [Sudan]. 1995. Sudan maternal and child health survey: principal report Republic of Sudan and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States.

- Ministry of Public Health [Tunisia]. 1996. Tunisia maternal and child health survey: summary report Republic of Tunisia and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States.

- Naseeb T, Farid SM. 2000. Bahrain family health survey Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey.

- Omran AR, Roudi F. The Middle East population puzzle. Population Bulletin. 1993;48:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ORC Macro. 2003. Demographic and health surveys Measure DHS +STAT compiler. Macro International Inc. Calverton, USA. Web site: http://www.measuredhs.com/, accessed in July 2003.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. 1997. Health survey in the West Bank and Gaza Strip- 1996. Main findings Ramallah, Palestine.

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. 2002. Selected statistics Web site: [http://www.pcbs.org/inside/selcts.htm] accessed in December 2002.

- Russell JK. Caesarean section. British Medical Journal. 1981;283:1076. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6299.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakala C. Medically unnecessary caesarean section births: introduction to a symposium. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;37:1177–98. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90331-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage W. The Caesarean section epidemic. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;20:223–5. doi: 10.1080/01443610050009485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata 7 for Windows. 2001. Texas: Stata Corporation.

- Sulaiman AJ, Al-Riyami A, Farid SM. 2000. Oman family health survey Riyadh: Gulf Family Health Survey. [PubMed]

- The General People’s Committee for Health and Social Insurance [Libya]. 1996. Arab Libyan maternal and child health survey: principal report The Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiria and the Pan Arab Project for Child Development (PAPCHILD) of the League of Arab States.

- UN PRED. 2002. Population, resources, environment and development database (PRED, version 3.0) New York: United Nations.

- UNDP and AFESD. 2002. Arab human development report 2002: creating opportunities for future generations New York: United Nations Development Program.

- UNFPA. 2003. Country Profile New York: United Nations Population Fund. Web site: [http://www.unfpa.org/profile/palestini-anterritory.cfm] accessed in August 2003.

- UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA. 1997. Guidelines for monitoring the availability and use of obstetric services New York: United Nations Children’s Fund. pp. 1–103.

- WHO. 2002. Countries Geneva: World Health Organization. Web site: [http://www.who.int/country/en/] accessed in December 2002.

- Ziadeh SM, Abu-Heija AT. Reducing caesarean section rates and perinatal mortality. a four year study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;15:171–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ziadeh SM, Sunna E, Badria LF. The effect of mode of delivery on neonatal outcome of twins with birthweight under 1500 grams. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;20:389–91. doi: 10.1080/01443610050112039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]