Abstract

N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide (4HPR), a synthetic retinoid effective in cancer chemoprevention and therapy, is thought to act via apoptosis induction resulting from increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. As ROS can activate MAP kinases and protein kinase C (PKC), we examined the role of such enzymes in 4HPR-induced apoptosis in HNSCC UMSCC22B cells. 4HPR increased ROS level within 1 h and induced activation of caspase 3 and PARP cleavage within 24 h. Activation of MKK3/6 and MKK4, JNK, p38 and ERK was detected between 6 and 12 h, increased up to 24 h and preceded apoptosis. 4HPR-induced activation of these kinases was abrogated by the antioxidants BHA and vitamin C. SP600125, a JNK inhibitor, suppressed 4HPR-induced c-Jun phosphorylation, cytochrome c release from mitochondria and apoptosis. Suppression of JNK1 and JNK2 using siRNA decreased, whereas overexpression of wild type-JNK1 enhanced 4HPR-induced apoptosis. PD169316, a p38, inhibitor suppressed phosphorylation of Hsp27 and apoptosis. PD98059, an MEK1/2 inhibitor, also suppressed ERK1/2 activation and apoptosis induced by 4HPR. Likewise, PKC inhibitor GF109203X suppressed ERK and p38 phosphorylation and PARP cleavage. These data indicate that 4HPR-induced apoptosis is triggered by ROS increase, leading to the activation of the mitogen-activated protein serine/threonine kinases JNK, p38, PKC and ERK, and subsequent apoptosis.

Keywords: 4HPR, apoptosis, ROS, MAPK, HNSCC

Introduction

Several retinoids, including natural and synthetic analogs of vitamin A, exert regulatory effects on epithelial cell growth, differentiation and death (Lotan, 1996) as well as tumor-preventive effects in a variety of carcinogenesis models (Freemantle et al., 2003). N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide (4HPR), also known as fenretinide, is a synthetic retinoid, which has a low degree of toxicity relative to other retinoids, and has shown efficacy as an antineoplastic agent in experimental models and clinical trials. In animal models, 4HPR can inhibit carcinogenesis in a variety of tissues (Formelli et al., 1996; Malone et al., 2003). Various clinical trials involving chemoprevention of cancers of the breast, prostate, cervix, skin and lung have also been conducted (Malone et al., 2003). 4HPR is currently undergoing clinical trials for the prevention or treatment of oral premalignant lesions, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, brain tumor (glioblastoma multiforme) and neuroblastoma in children (Malone et al., 2003; Reynolds, 2004).

Although the mechanisms of the in vivo activities of 4HPR are not yet elucidated, the findings by several groups that 4HPR promotes apoptosis in a variety of tumor cell lines imply that this cellular event may be important for both the chemopreventive and therapeutic effects of 4HPR (Reed, 1999; Sun et al., 2004).

4HPR appears to induce apoptosis predominantly by the activation of the mitochondrial pathway (Suzuki et al., 1999; Hail and Lotan, 2000; Boya et al., 2003). Increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Delia et al., 1997; Suzuki et al., 1999; Hail and Lotan, 2001), increased ceramide production (Maurer et al., 1999), induction of mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) (Suzuki et al., 1999; Hail and Lotan, 2000; Poot et al., 2002; Boya et al., 2003), cytochrome c release (Suzuki et al., 1999; Asumendi et al., 2002; Boya et al., 2003), increased GADD153 (Kim et al., 2002; Lovat et al., 2002), and activation of 12-lipoxygenase (Lovat et al., 2002) or activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (Chen et al., 1999; Shimada et al., 2002; Osone et al., 2004) have been implicated in 4HPR-mediated apoptosis in various cancer cells. In addition, retinoid receptors may contribute to 4HPR-induced apoptosis in some cells (Sun et al., 1999; Lovat et al., 2000; Ulukaya et al., 2003).

The level of ROS appears to increase immediately after exposure of certain cells to 4HPR via retinoid receptor-independent mechanism (Delia et al., 1997; Sun et al., 1999; Suzuki et al., 1999). Previous studies by our group have shown that 4HPR induces apoptosis by generating ROS in HNSCC cells (Sun et al., 1999). ROS has been shown to activate several mitogen-activated protein serine/threonine kinases (MAPKs), which transduce diverse extracellular stimuli (mitogenic growth factors, environmental stresses, and proapoptotic agents) to the nucleus via kinase cascades to regulate a wide array of cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (Davis, 2000; Chang and Karin, 2001; Kyriakis and Avruch, 2001).

In this study, we used antioxidants and a variety of pharmacological inhibitors of different kinases to examine the effects of 4HPR on the major MAPK and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathways in HNSCC cells and their relation to the increase in ROS. Our results demonstrate that 4HPR-induced apoptosis is mediated by activation of JNK, p38, ERK and PKC by a mechanism that is triggered by ROS generation. Furthermore, we show that 4HPR disrupts mitochondrial integrity that leads to activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

Results

Detection of 4HPR-induced apoptosis in HNSCC cells by Western blotting

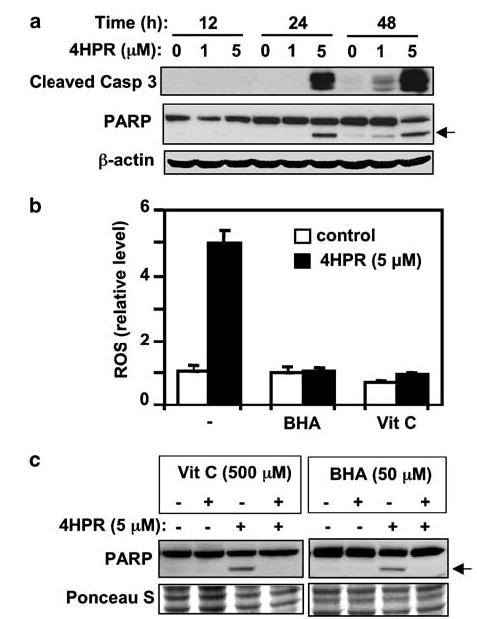

As the major technique that we had intended to use for demonstration of MAPK activation (phosphorylation) was Western blotting, we first established conditions for detecting 4HPR-induced apoptosis in SDS–PAGE gels to be able to analyse kinase activation and apoptosis in the same cell lysate. Figure 1a shows that induction of apoptosis by 4HPR in HNSCC cells could be demonstrated by Western blot with antibodies against the activated (cleaved) form of caspase 3 and also by antibodies against PARP, a substrate for the proteolytic activity of caspase 3. Specifically, treatment of the 22B cells with 5 μm 4HPR resulted in caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage after 24 h. Some apoptosis could also be detected in cells treated with 1 μm 4HPR, albeit after 48 h. Therefore, we decided to use 24 h treatment with 5 μm 4HPR for evaluation of apoptosis in subsequent experiments. It is noteworthy that 12.9 μm concentration can be achieved pharmacologically in pediatric neuroblastoma patients receiving oral 4HPR (Garaventa et al., 2003).

Figure 1.

Induction of apoptosis by 4HPR and its suppression by antioxidants. (a) Time course of activation of caspase-3 and cleavage of PARP induced by 4HPR. The cells were treated with 4HPR (1 or 5 μm as indicated) or DMSO control for 12, 24, or 48 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to SDS–PAGE, followed by Western blotting with specific antibodies against cleaved caspase-3 and PARP, followed by anti-actin antibodies to ascertain equal loading. (b) Effects of antioxidants on ROS generation were determined after 60 min of incubation with 4HPR or 4HPR plus BHA or vitamin C using the DCF-DA assay. (c) Effect of antioxidants on 4HPR-induced PARP cleavage was determined by Western blotting analysis. Arrows point to the location of the cleaved PARP fragment. Ponceau S staining was used to compare loading in different lanes.

Suppression of 4HPR-induced ROS generation and apoptosis in UMSCC22B cells by antioxidants

ROS has been shown to activate multiple signaling pathways leading to various cellular responses including apoptosis. Treatment of the 22B cells with 5 μm 4HPR for 1 h resulted in a five-fold increase in ROS level (Figure 1b). The antioxidants BHA (50 μm) and vitamin C (500 μm) effectively blocked 4HPR-induced ROS production (Figure 1b). Furthermore, cells treated with either antioxidant were protected from 4HPR-induced apoptosis, as observed after 24 h (Figure 1c).

4HPR induces activation of JNK, p38/MAPK and ERK as downstream events of ROS production

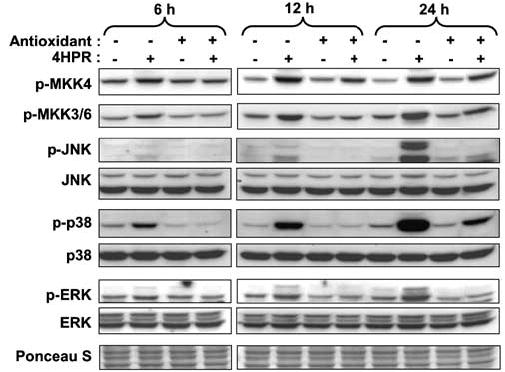

To determine whether 4HPR-induced ROS leads to activation of MAPKs in our cell system, we determined the phosphorylation state of MAPK kinases (MKK4, MKK3/6) and their major downstream targets (JNK, p38 and ERK) by Western blot analysis using phospho-specific antibodies that specifically detect the activated form of each kinase. Total protein levels of the MAPKs were also analysed to determine whether there are changes in the total amount of the enzymes. Figure 2 shows that the phosphorylation of all the kinases was increased by 4HPR in a time-dependent manner. The change was first observed 6 h following 4HPR treatment and was sustained for at least 24 h. The total protein level of JNK, p38 and ERK remained unchanged during 4HPR treatment.

Figure 2.

Effects of antioxidants (BHA and vitamin C) on 4HPR-induced activation of MKKs (MKK4 and MKK3/6) and their downstream substrates MAPKs (JNK, p38 and ERK). Cells were treated with 4HPR (5 μm) alone or with antioxidant (BHA (50 μm) for MKK4, JNK and ERK, and vitamin C (500 μm) for MKK3/6 and p38) for the indicated time periods. The cells were then harvested and total cell lysates were prepared and resolved on 10% SDS–PAGE and subjected to Western blotting analysis with antibodies against the different protein kinases.

To determine whether the increase in ROS that was detected within 1 h of 4HPR treatment is involved in kinase activation, we tested the effects of antioxidants on 4HPR-induced activation of these kinases. Pretreatment of the cells with doses of antioxidants that blocked ROS generation (Figure 1b) abrogated 4HPR-induced activation of all kinases albeit to different degrees with greatest effects on JNK, p38, and ERK and lesser effects on MKK3/6 and 4 (Figure 2). These results suggest that ROS production increased by 4HPR contributes at least in part to the activation of JNK, p38 and ERK and that ROS is located upstream of MKK4 and MKK3/6.

Activation of JNK and p38 by 4HPR

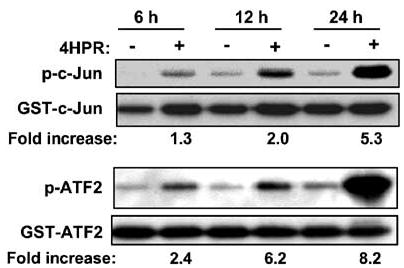

The increases in the activities of JNK and p38 by 4HPR suggested by their increased phosphorylation (Figure 2) were validated by kinase assay using GST-c-Jun and GST-ATF2 as substrates, respectively (Figure 3). Activation became apparent about 6 h following treatment and was sustained over the following 24 h period, which is consistent with the result obtained by Western analysis of the phosphorylated kinases. 4HPR also activated JNK and p38 in other HNSCC cell lines (e.g., UMSCC38 and MDA886, data not shown) that are also induced to undergo apoptosis, suggesting that these activations may be common signaling events induced by 4HPR in HNSCC cells.

Figure 3.

Effects of 4HPR on JNK and p38 kinase activities. Cells were treated with DMSO or 4HPR (5 μm) for the indicated times. The cells were then harvested, solubilized and the lysates were used for JNK and p38 kinase assays with GST-c-Jun and GST-ATF-2 as substrates, respectively (see Materials and methods). Data from a representative experiment from among three independent experiments with similar findings are shown. The phosphorylation was quantitated by densitometry using the NIH image analysis program. ‘Fold increase’ is expressed relative to the control value obtained with DMSO-treated cells (−).

Pharmacological Inhibitor of JNK suppresses 4HPR-induced cell death

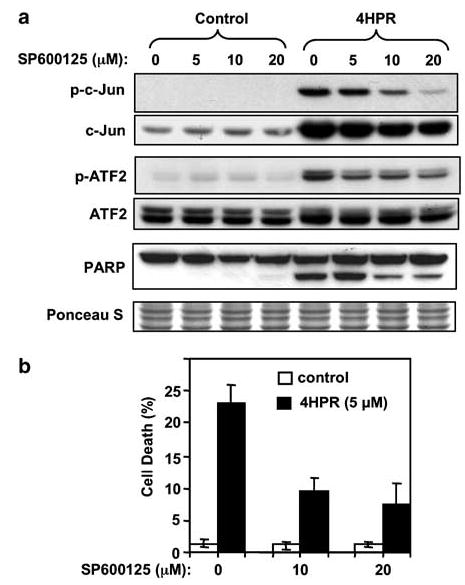

The JNK-specific kinase inhibitor SP600125 (Bennett et al., 2001) suppressed phosphorylation of c-Jun induced by 4HPR in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4a). The phosphorylation of ATF2 was also suppressed, though only partially. The SP600125 doses used in this study appear to be specific for inhibition of JNK activity because they did not inhibit the activity of other MAP kinases like p38 and ERK (data not shown). SP600125 also suppressed 4HPR-induced apoptosis indicated by PARP cleavage. Inhibition of 4HPR-induced cell death by SP600125 was confirmed in 22B cells by nuclear DAPI staining (Figures 4b and 5a). Inhibition of cell death by SP600125 was also observed in HNSCC 886 cells (data not shown), suggesting that JNK activation may be a common requirement in 4HPR-induced cell death in HNSCC cells.

Figure 4.

Effects of a JNK inhibitor on 4HPR-induced apoptosis. (a) Cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of SP600125 for 2 h. Then 4HPR (5 μm) was added to the culture medium and cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. Phosphorylation status of the JNK substrates c-Jun and ATF-2 was determined by Western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies. PARP cleavage was determined by re-probing the membranes using specific antibodies. (b) Inhibition of 4HPR-induced cell death by SP600125 was quantified by nuclear DAPI staining as described in ‘Materials and methods’. The data are the mean ± s.d. of triplicates.

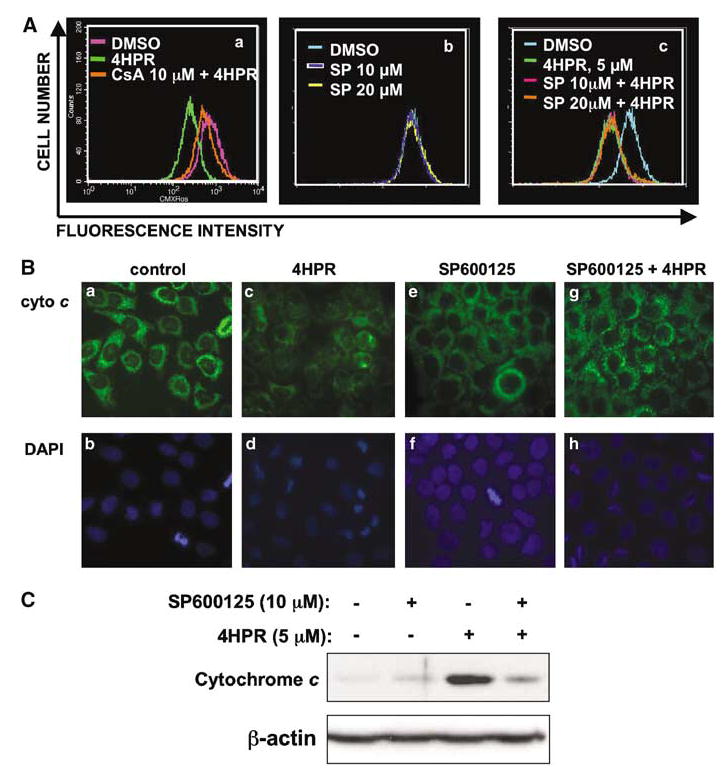

Figure 5.

Effect of JNK inhibitor on mitochondrial events induced by 4HPR. (A) Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential were monitored by using cell-permeable mitochondria-selective dye CMXRos as described in ‘Materials and methods’. (a) Cells were pretreated with cyclosporine A (CsA) for 1 h, followed by incubation either with DMSO or 4HPR for an additional 1 h. (b, c) Cells were pretreated with SP600125 for 2 h, followed by incubation with DMSO or 4HPR for an additional 1 h. (B) Subcellular localization of cytochrome c was determined by immunofluorescence. Cells were pretreated with DMSO or SP600125 (10 μm) for 2 h and subsequently incubated with 4HPR for 14 h. The cells were then subjected to immunofluorescent labeling to localize cytochrome c as described in ‘Materials and methods.’ (a, c, e, g) cytochrome c staining. (b, d, f, h) nuclear DAPI staining. (C) Detection of cytochrome c by Western blotting analysis. After cells were treated with either 4HPR alone or in combination with SP600125, cytosolic proteins were isolated and subjected to Western blot analysis using cytochrome c antibody. The membrane was probed with β-actin antibodies to compare loading in different lanes.

JNK inhibitor suppresses cytochrome c release from mitochondria

JNK has been shown to be required for cytochrome c release from mitochondria in stress-induced apoptosis (Tournier et al., 2000) and 4HPR has been shown to induce cytochrome c release from mitochondria in various cell types (Suzuki et al., 1999; Asumendi et al., 2002; Boya et al., 2003). To delineate the mechanism of JNK function in 4HPR-induced apoptosis in 22B cells, we examined the effect of SP600125 on mitochondrial events induced by 4HPR.

Dissipation of the mitochondrial inner-membrane potential followed by permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane induced by apoptotic agents is considered to be one of the mechanisms by which proapoptotic proteins (e.g. cytochrome c, apoptosis-inducing factor) are released from mitochondria (Robertson and Orrenius, 2002; Zamzami and Kroemer, 2003). Increase in mitochondrial membrane permeability has been shown to be a central event in 4HPR-induced cell death in some cells (Hail and Lotan, 2000; Poot et al., 2002; Boya et al., 2003). To determine whether 4HPR can induce changes in membrane permeability in HNSCC22B cells, the inner membrane potential was monitored after 4HPR treatment by using the mitochondria-specific dye CMXRos. Cells underwent maximal depolarization of membrane potential 1 h after exposure to 4HPR, after which the membrane potential was gradually recovered during treatment, although it was not completely reversed to the value of control. 4HPR-induced dissipation of membrane potential was effectively inhibited by cyclosporin A, an inhibitor of the permeability transition pore complex (Figure 5A(a)). However, JNK inhibitor had no effect on membrane potential in untreated cells (Figure 5A(b)) or on the loss of membrane potential induced by 4HPR treatment (Figure 5A(c)).

Cytochrome c release is a consequence of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization (Kroemer and Reed, 2000). Cytochrome c release was determined by immunofluorescence by using specific antibodies. In the absence of 4HPR, cells treated with DMSO or SP600125 showed punctate perinuclear cytoplasmic staining pattern, which is an indication that cytochrome c is contained within the mitochondria (Figure 5B(a), (b) and B(e), (f)). 4HPR-treated cells, however, showed condensed nuclei (apoptotic cells) and diffuse cytochrome c staining pattern, suggesting that it was released from the mitochondria (Figure 5B(c) and (d)). Cells treated concurrently with a combination of SP600125 and 4HPR showed a staining pattern that was similar to the untreated (DMSO) controls, indicating that SP600125 blocked cytochrome c release from mitochondria (Figure 5B(g)). Suppression of 4HPR-induced cytochrome c release by JNK inhibitor was also confirmed by decrease in the level of cytochrome c in the cytosolic fraction, as determined by Western blot analysis (Figure 5C). These results imply that 4HPR-induced cytochrome c release requires JNK activation.

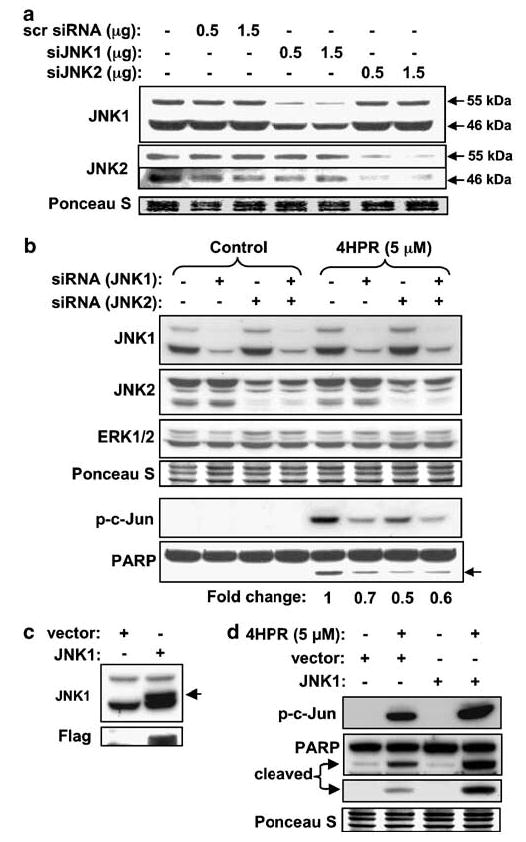

siRNA against JNK1 and JNK2 suppresses cell death induced by 4HPR

The involvement of JNK in 4HPR-induced apoptosis was further tested in 22B cells that had been transiently transfected with siRNA against JNK1 and JNK2 mRNA. Transfection of JNK1 and JNK2 siRNAs resulted in decrease in the basal protein levels of JNK1 and JNK2, respectively (Figure 6a). This effect was specific, as evidenced by: (a) the inability of scrambled siRNA to decrease either of the two JNK species, (b) the finding that JNK1 siRNA decreased the level of JNK1 and did not affect the level of JNK2 and vice versa and (c) neither siRNA decreased the level of ERK (Figure 6b). siRNA JNK1 and JNK2 also suppressed the phosphorylation of c-Jun induced by 4HPR. More importantly, siRNA JNK1 or JNK2 suppressed 4HPR-induced PARP cleavage by about 30 and 50%, respectively, compared to nontransfected cells, as determined by Western blotting analysis with PARP antibody (Figure 6b).

Figure 6.

Demonstration of the role of JNK1 and JNK2 in 4HPR-induced cell death using loss- and gain-of-function approaches. (a) Effect of siRNA against JNK1 and JNK2 on endogenous JNK1 and JNK2 protein levels. Cells were transfected with siRNA against JNK1, JNK2 or scrambled siRNA. The protein levels of JNK1 and JNK2 were determined by Western blotting 1 day after transfection by using antibodies against JNK1 and JNK2. (b) Effects of siRNA against JNK1 and JNK2 on 4HPR-induced cell death. Cells transfected with siRNA against JNK1, JNK2 or combination of the two were treated with 4HPR for 24 h and total cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using the antibodies indicated. (c) Cells were transiently transfected with either empty vector or wt-JNK1 expressing vector. The levels of endogenous and exogenously expressed JNK1 were determined by Western blotting 24 h after transfection. (d) Cells transfected with wt-JNK1 were treated with 4HPR for 24 h. Total cell lysates were analysed by Western analysis to determine the level of phospho-c-Jun and cleaved PARP.

Overexpression of JNK enhances 4HPR-induced cell death

To further confirm the involvement of JNK in 4HPR-induced cell death pathway in 22B cells, we first transiently transfected the cells with JNK1-expressing plasmid and found that it was indeed increasing the level of the JNK1 protein (Figure 6c). Overexpression of JNK1 enhanced the induction of phosphorylation of c-Jun by 4HPR (Figure 6d). JNK1 overexpression also increased 4HPR-induced apoptosis as evidenced by PARP cleavage, whereas overexpression alone had no effect on cell viability (Figure 6d). These results further support the conclusion that JNK is required for 4HPR-induced apoptosis in 22B cells.

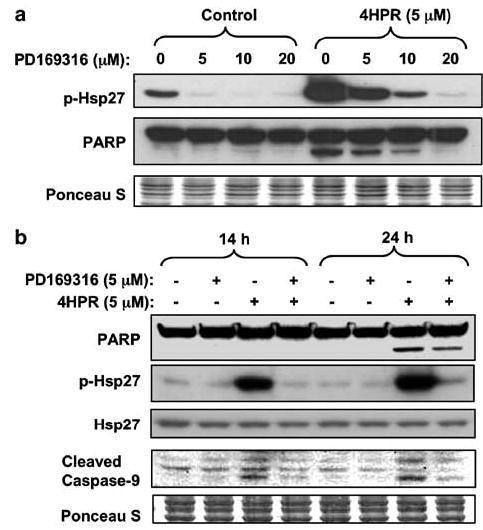

p38/MAPK inhibitor suppresses 4HPR-induced cell death

As ATF2 is a substrate for both JNK and p38 and the JNK-specific inhibitor SP6000125 suppressed ATF2 phosphorylation only partially, we surmised that p38 also contributes to ATF2 activation in the 22B cells. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of the specific p38 MAPK inhibitor, PD169316, on p38 activity. For this purpose, we followed phosphorylation of Hsp27, which is downstream of p38 in the p38-dependent signaling pathway and is not activated by JNK (Rouse et al., 1994; McLaughlin et al., 1996). Figure 7a shows that PD169316 suppressed in a dose-dependent manner both 4HPR-induced Hsp27 phosphorylation and cell death, as determined by PARP cleavage. The suppression of 4HPR-enhanced Hsp27 phosphorylation by PD169316 was accompanied by inhibition of 4HPR-induced cleavage of caspase 9 (Figure 7b). These findings indicate that p38 is involved in the proapoptotic signal induced by 4HPR through the mitochondrial pathway.

Figure 7.

Effects of a p38/MAPK inhibitor on 4HPR-induced apoptosis. (a) Cells were pretreated with PD169316 at different doses for 2 h, followed by incubation with 4HPR for an additional 24 h. The phosphorylation status of the Hsp27 was determined by Western blotting with phospho-specific antibody as an indication of p38 kinase activity. (b) Cells treated with 4HPR alone or in combination with PD169316 for the indicated time periods were analysed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies.

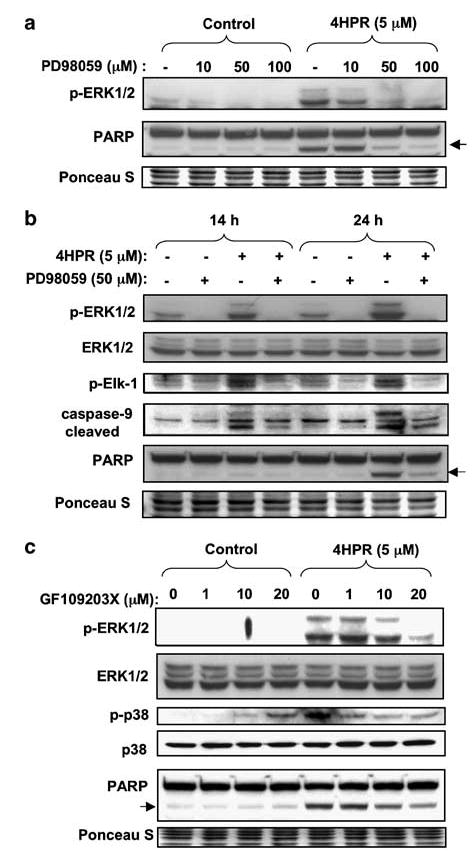

MEK1/2 inhibitor suppresses 4HPR-induced apoptosis

ERK activation can be inhibited by PD98059, a specific inhibitor of MEK1/2 (an upstream kinase of ERK). Figure 8a shows that PD98059 dose-dependently suppressed the phosphorylation of ERK induced by 4HPR. Furthermore, PD98059 also suppressed 4HPR-induced phosphorylation of Elk-1, a target of ERK, indicating that PD98059 indeed inhibited the activity of ERK (Figure 8b). In addition, PD98059 suppressed 4HPR-induced caspase 9 and PARP cleavage (Figure 8b). All these findings indicate that ERK is involved in 4HPR-induced apoptosis.

Figure 8.

Effect of MEK1/2 inhibitor (PD98059) and PKC inhibitor (GF109203X) on 4HPR-induced apoptosis. (a) Cells were pretreated with PD98059 with the indicated concentrations for 2 h followed by incubation with 4HPR for additional 24 h. Phosphorylation status of ERK1/2 (a substrate of MEK1/2) was determined by Western blotting with phospho-specific antibody. (b) Cells were pretreated with 50 μm PD98059 for 2 h. 4HPR was then added to the culture medium and cells were incubated for additional 14 or 24 h. Phosphorylation status of the kinase target proteins was determined by Western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies against ERK and Elk-1. PARP cleavage, a marker of caspase-3 activation and apoptosis, and caspase-9 cleavage were determined by re-probing the membranes using specific antibodies. (c) Cells were pretreated with the indicated concentrations of GF109203X for 2 h, followed by incubation with 4HPR for additional 24 h. Phosphorylation status of ERK1/2 and p38 was determined by Western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies and antibodies against total ERK1/2 and p38. PARP cleavage was determined by re-probing the membranes using specific antibodies. The membranes were stained with Ponceau S to compare loading in different lanes.

Implication of PKC in activation of ERK and p38 by 4HPR

The PKC pathway is another mechanism by which ERK and p38 are activated (Ueda et al., 1996; Schonwasser et al., 1998). To determine whether such a mechanism could account for the activation of ERK by 4HPR, we used the pan-selective PKC inhibitor GF109203X. At doses up to 20 μm, this inhibitor was able to diminish the phosphorylation of ERK and p38 and the cleavage of PARP in a dose-dependent manner in 4HPR-treated cells (Figure 8c) without inducing apoptosis when used alone (Figure 8c).

Discussion

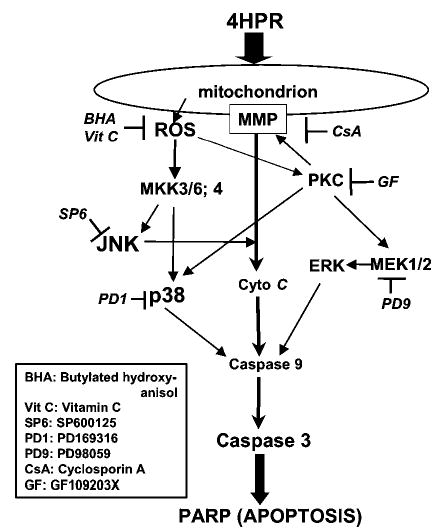

In this study, we tried to delineate the signaling pathways activated by 4HPR, leading to cell death in HNSCC cells. Our data show that 4HPR-increased ROS generation is a proximal and an early event that triggers the activation of the MAPKs JNK, p38 and ERK. We further demonstrated using various inhibitors that the activation of these kinases was important for 4HPR-induced apoptosis pathway. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report implicating all three major MAPKs in mediating 4HPR-induced apoptosis as downstream effectors of ROS. The different pathways affected by 4HPR are depicted in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the different pathways shown in this report to be activated by 4HPR through ROS and lead to apoptosis in HNSCC cells. The use of antioxidants and various inhibitors of kinases indicates that 4HPR acts on the mitochondria to increase the production of ROS and alter the mitochondrial membrane potential. The increased membrane permeability facilitates the release of cytochrome c to the cytoplasm. The increase in ROS also activates PKC and MKKs. The activation of PKC further augments cytochrome c release, as well as activates p38 and MEK1/2. The activation of ERK appears to be associated with apoptosis induction. The activation of MKKs results in activation of JNK and p38, which could enhance apoptosis via the cytochrome c, caspase-9 and caspase-3 pathway.

JNK and p38 are activated by various stress stimuli, including oxidative stress (Ichijo, 1999). In the present study, we showed that 4HPR treatment resulted in sustained activation of these two kinases during the apoptotic process up to 24 h when the apoptotic phenotypic markers are detected (e.g. PARP cleavage, nuclear condensation). We also demonstrated that activation of JNK and p38 are necessary for the 4HPR-induced apoptosis by using pharmacological inhibitors (SP600125 for JNK and PD169316 for p38). Inhibition of activity of JNK and p38 by these methods resulted in decrease in phosphorylation of their substrates, c-Jun and Hsp27, respectively. The requirement of JNK in 4HPR-induced apoptosis was further confirmed by the observation that decreased levels of JNK in cells transfected with specific siRNA resulted in partial resistance to the proapoptotic effect of 4HPR, whereas overexpression of wild type (wt)-JNK1 enhanced 4HPR-induced apoptosis. These results are in agreement with previous reports on other agents that concluded that longlasting activation of JNK and p38 is required for stress-induced apoptosis (Xia et al., 1995; Luo et al., 1998; Chen and Tan, 2000; Tobiume et al., 2001).

We demonstrated that ROS generation mediates the activation of JNK and p38 in 4HPR-induced cell death signaling pathway. Antioxidants (e.g., BHA, vitamin C) significantly attenuated activation of JNK and p38 as well as their respective upstream kinases MKK4 and MKK3/6 (Figure 2). It is noteworthy that MKK4, MKK3/6, p38 and ERK showed some constitutive activation without 4HPR treatment possibly due to some autocrine growth factor stimulation. JNK has been shown to be required for 4HPR-induced cell death in prostate cancer (Chen et al., 1999; Shimada et al., 2002). However, the link between JNK and ROS has not been demonstrated in those studies. Recently, Osone et al. (2004) have shown that 4HPR-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells was associated with sustained activation of JNK and p38 in a ROS-dependent manner. However, the mechanistic aspects of this association have not been clarified. Our results provide more direct evidence for the involvement of the ROS and MKK/MAPK pathway in 4HPR-induced apoptosis. In addition, we found that ERK activation in 4HPR-treated HNSCC cells is induced by ROS and is playing a role in apoptosis induction.

JNK has been implicated in stress-induced cytochrome c release from mitochondria and apoptosis, which did not require new gene expression (Tournier et al., 2000). We found that 4HPR increases MPT and cytochrome c release. Interestingly, the JNK inhibitor suppressed cytochrome c release and apoptosis without reversing the effects of 4HPR on MPT (Figure 5), suggesting that increased MPT is not sufficient for cytochrome c release. Other factors that are involved in cytochrome c release are the members of the Bcl2 family (Kroemer and Reed, 2000). JNK has been shown to phosphorylate several members of the Bcl2 family of proteins, resulting in inhibition of the antiapoptotic activity of Bcl2 and Bcl-XL (Yamamoto et al., 1999; Kharbanda et al., 2000), while enhancing the proapoptotic activity of Bad (Donovan et al., 2002). JNK also has been shown to promote translocation of Bax to the mitochondria, leading to activation of the mitochondrial pathway (Yu et al., 2003; Tsuruta et al., 2004). Such mechanisms could explain the involvement of JNK in 4HPR-induced cytochrome c release from the mitochondria. Indeed, Bax relocalization into the mitochondria has been implicated in ROS-mediated apoptosis induced by 4HPR (Boya et al., 2003).

In the present study, we demonstrated that similar to its effect on JNK and p38, 4HPR induced persistent activation of ERK as a downstream event of ROS production and that activated ERK is also required for apoptosis in UMSCC22B cells. ERK appears to act via the mitochondria because inhibition of ERK by the MEK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 resulted in decrease in 4HPR-induced cleavage of PARP (a substrate of caspase-3) and caspase-9. It is noteworthy that anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2 can be phosphorylated and inhibited by ERK (Tamura et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2004). The proapoptotic role of ERK in 4HPR-induced cell death is a novel finding that is somewhat unexpected because ERK has been associated with enhanced cell proliferation (Chang and Karin, 2001) and increased survival signal that counteracted proapoptotic effects mediated by JNK and/or p38 activation (Xia et al., 1995; Seidman et al., 2001; Carvalho et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004). Furthermore, oxidative stress has been shown to activate ERK as a protective mechanism (Guyton et al., 1996; Aikawa et al., 1997; Bhatt et al., 2002). However, a proapoptotic role has been demonstrated for ERK in several studies with different stimuli, including anticancer drugs (Stanciu et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000; Guise et al., 2001; Xiao and Singh, 2002; Lee et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; Nguyen et al., 2004).

It is noteworthy that androgen-independent prostate cancer cells PC-3 and DU145 with constitutively activated ERK were resistant to 4HPR (Shimada et al., 2002), whereas ERK was required for testosterone-induced sensitization of LNCaP cells to 4HPR (Shimada et al., 2003). Although neither of these studies examined the ability of 4HPR to induce activation of ERK, they point out that ERK can regulate cell survival or death in a cell-type- and stimulus-specific way.

ERK activation downstream of ROS has been shown to be mediated by different signaling pathways, including growth factor receptors (epidermal growth factor receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor), Ras and PKC (Guyton et al., 1996; Aikawa et al., 1997; Martindale and Holbrook, 2002; Lee et al., 2003). We observed that the pan-PKC inhibitor GF109203X suppressed ERK and p38 activation and apoptosis induced by 4HPR, suggesting that PKC may be an upstream regulator of ERK in our system. Others have reported that PKCdelta is upstream of changes in mitochondrial memebrane leading to cytochrome c release (Liao et al., 2005) and PKCzeta is upstream of p38 MAPK activation in UVB-induced apoptosis (Won et al., 2005). ROS may be upstream of PKC because it has been shown that PKC-dependent induction of p21WAF1 by phorbol ester was inhibited by antioxidant (Traore et al., 2005).

In conclusion, we demonstrated that 4HPR induces prolonged activation of JNK, p38 and ERK as downstream events of ROS production in HNSCC cells. Furthermore, the activation of these MAPKs is required for 4HPR-induced apoptosis in HNSCC cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

HNSCC cell line UMSCC22B was obtained from Dr Thomas Carey (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The cells were grown in monolayer culture in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of DMEM and Ham’s F12 medium containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. 4HPR was obtained from Dr Ronald Lubet (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) and was prepared as a 10 mm stock solution in DMSO. 4HPR was kept at −20°C and diluted with culture medium just before use. The antioxidants BHA and Vitamin C were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Western blotting

Whole cell lysates (80–100 μg of protein) were separated by 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and processed for Western blotting as described previously (Kim and Lotan, 2004). Phospho-specific antibodies against c-Jun (Ser63, Ser73), ATF-2 (Thr71), hsp27 (Ser82), JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), MKK4 (Thr261) and MKK3/6 (Ser189/207), and antibodies against cleaved caspase-3, ERK were purchased from Cell Signaling Biotechnology (Beverly, MA, USA). Antibodies against Jun, JNK1, p38 and PARP were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Jose, CA, USA). Phospho-proteins were detected first with phospho-specific antibodies (JNK, p38, ERK) and the levels of total proteins were analysed on the same blots. The loading in different lanes was assessed by staining the blots with Ponceau S.

Kinase assay

Cells were treated with DMSO or 4HPR at indicated concentrations and times and harvested with lysis buffer and analysed by nonradioactive kinase assays for JNK and p38 (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction mixture was subjected to Western blotting and loading was normalized with the amount of GST–c-Jun or GST–ATF2 fusion proteins by probing the same blot with anti-GST antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Pharmacological inhibitors of JNK, p38/MAPK, ERK and PKC

Pharmacological inhibitors of JNK (SP600125), p38 (PD169316), MEK1/2 (PD98059) or PKC (GF109203X) (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA) were added to cells 2 h prior to 4HPR treatment. Cultures were maintained in the presence of both inhibitor and 4HPR for the designated time periods. SP600125, PD169316 and GF109203X were prepared as 10 mm stocks in DMSO and kept at −20°C. PD98059 was prepared as 50 mm stock solution in DMSO and kept at −20°C. The stock solution was diluted with culture medium right before use.

Transient transfection of cells with wt-JNK1

An expression vector containing wt-JNK1 was a kind gift of Dr Roger J Davis (University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA, USA). wt-JNK1 contains the Flag epitope (-Asp-Try-Lys-Asp-Asp-Asp-Asp-Lys-), which permits detection by immunoblotting using reagent specific for the Flag-tag, thus allowing discrimination of exogenous proteins from endogenous proteins. Transient transfection of cells with wt-JNK1 plasmid was conducted using ‘cell line Nucleofection kit V’ (Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were suspended at 1.5 × 106 cells per 100 μl of transfection solution (Nucleofector solution V). After 4 μg of plasmid DNA was added to the cells (pcDNA3 or wt-JNK1), the mixtures were transferred to electroporation cuvettes and subjected to electroporation using programs provided by the manufacturer. The cell suspensions were immediately mixed with 500 μl pre-warmed RPMI medium supplemented with 5% FBS and incubated for 5 min at 37°C. The cells were then transferred to a six-well plate with pre-warmed DMEM/F12 containing 5% FBS and incubated for 24 h before treatment with 4HPR.

Transfection of siRNA against JNK1 and JNK2

SiRNAs against JNK1 and JNK2 were prepared by a proprietary design and synthesized as a SMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon Inc., Lafayette, CO, USA). The SiRNAs are 21 nucleotides forming 19-base-pair duplex cores with symmetrical two nucleotide 3′-UU overhangs. SMARTpool siRNA pool is composed of 4 SMARTselection-designed siRNA. We used 1 μg of siRNA per 1.5 × 106 cells employing the same transfection protocol as the one described above for wt-JNK plasmid.

Measurement of intracellular ROS

Intracellular production of ROS in cells was measured using the oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye DCFH-DA as described previously (Suzuki et al., 1999). Equal numbers of cells (8 × 104/well) for each of the cell lines were seeded in 24-well cell culture plates. Cells were washed twice with Krebs-Ringer buffer (Invitrogen/Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) on the second day after seeding. Cells were incubated with Krebs–Ringer buffer containing 10 μg/ml of DCFH-DA and 4HPR at 37°C. The fluorescence intensity of DCF was measured at 530 nm emission wavelength after excitation at 480 nm for 1 h using a CytoFluor 2350 Fluorescence Measurement System (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). An increase in fluorescence intensity was used to represent the generation of net intracellular ROS. Each treatment was performed in four replicate wells and the results were calculated as the mean±s.d.

Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential

Mitochondrial membrane potential was monitored by FACS analysis using cell-permeable mitochondria-selective dye Mito Tracker Red CMX (CMXRos) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). Cells were treated with 4HPR and other reagents for the indicated time periods. CMXRos was added to the culture medium at 100 nm final concentration 20 min before harvest for assay. The media was removed and cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After detachment by trypsinization, cells were resuspended in PBS and subjected to FACS analysis for assessment of CMXRos fluorescence (488 and 585 nm excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively) and cell numbers using a Becton Dickinson flow cytometer.

Cell fractionation for cytochrome c assay

Cytosolic fraction was isolated by using ‘Cytochrome c releasing Apoptosis Assay kit’ from BioVision Research Products (Mountain View, CA, USA). Briefly, cells (5 × 106) were harvested by trypsinization, washed once in ice-cold PBS and resuspended in 100 μl of 1 × Cytosol Extraction Buffer. After incubation on ice for 10 min, cells were homogenized by gentle douncing (100 strokes) in a glass microgrinder and centrifuged at 700 g for 10 min at 4°C to pellet nuclei and unbroken cells. Supernatants from the centrifugation were further centrifuged at 10 000 g for 30 min at 4°C to get cytosolic fraction (supernatant) and mitochondrial fraction (pellet). Cytosolic fractions (20 μg) were separated by 12% SDS–PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis using a monoclonal antibody to cytochrome c.

Immunofluorescent staining of cytochrome c

Cells were plated at a density of 8 × 105 cells per chamber in a four-chamber microscope slide in medium (MEM/F12, 5% FBS) and incubated overnight. The cells were then treated with 4HPR alone or in combination with SP600125. The cells were then fixed in ice-cold 4% buffered paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. After washing with PBS, cells were incubated with 5% normal goat serum for 1 h and subsequently with cytochrome c antibody (BD Bioscience/Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) diluted (1:1000) in 5% goat serum overnight. The cells were washed with PBS three times, and incubated with FITC-labeled goat-anti-mouse secondary antibody (Alexa 488) for 1 h in the dark. Cells were washed with PBS and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (10 μg/ml). The cells were then mounted in anti-fade mount (Biomeda, Foster City, CA, USA).

DAPI staining and quantification of apoptosis

Apoptosis was quantitated by determining the proportion of DAPI-stained cells with condensed or fragmented nuclei. Cells were plated in 12-well culture dishes and treated with 4HPR alone or in combination with JNK inhibitor for 24 h. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at 4°C, washed twice with PBS and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at 4°C. Then the cells were incubated for 10 min with DAPI solution (10 μg/ml) diluted in PBS. More than 100 cells from three different fields were counted under the microscope and a percentage of apoptotic cell population was calculated.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Head and Neck Cancer SPORE grant P50 CA97007 and Cancer Center Core Grant P30 CA16672-30 from the NCI.

References

- Aikawa R, Komuro I, Yamazaki T, Zou Y, Kudoh S, Tanaka M, et al. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1813–1821. doi: 10.1172/JCI119709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asumendi A, Morales MC, Alvarez A, Arechaga J, Perez-Yarza G. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1951–1956. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O’Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt NY, Kelley TW, Khramtsov VV, Wang Y, Lam GK, Clanton TL, et al. J Immunol. 2002;169:6427–6434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Morales MC, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Andreau K, Gourdier I, Perfettini JL, et al. Oncogene. 2003;22:6220–6230. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho H, Evelson P, Sigaud S, Gonzalez-Flecha B. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:502–513. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Karin M. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YR, Tan TH. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:651–662. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YR, Zhou G, Tan TH. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1271–1279. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.6.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RJ. Cell. 2000;103:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delia D, Aiello A, Meroni L, Nicolini M, Reed JC, Pierotti MA. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:943–948. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.5.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan N, Becker EB, Konishi Y, Bonni A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40944–40949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Formelli F, Barua AB, Olson JA. FASEB J. 1996;10:1014–1024. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freemantle SJ, Spinella MJ, Dmitrovsky E. Oncogene. 2003;22 :7305–7315. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaventa A, Luksch R, Lo Piccolo MS, Cavadini E, Montaldo PG, Pizzitola MR, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2032–2039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guise S, Braguer D, Carles G, Delacourte A, Briand C. J Neurosci Res. 2001;63:257–267. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20010201)63:3<257::AID-JNR1019>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton KZ, Liu Y, Gorospe M, Xu Q, Holbrook NJ. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4138–4142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hail N, Jr, Lotan R. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:1293–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hail N, Jr, Lotan R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45614–45621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichijo H. Oncogene. 1999;18:6087–6093. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharbanda S, Saxena S, Yoshida K, Pandey P, Kaneki M, Wang Q, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:322–327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DG, You KR, Liu MJ, Choi YK, Won YS. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38930–38938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Lotan R. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2439–2448. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Reed JC. Nat Med. 2000;6:513–519. doi: 10.1038/74994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Cho HN, Soh JW, Jhon GJ, Cho CK, Chung HY, et al. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291:251–266. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao YF, Hung YC, Chang WH, Tsay GJ, Hour TC, Hung HC, et al. Life Sci. 2005;77:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotan R. FASEB J. 1996;10:1031–1039. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovat PE, Oliverio S, Ranalli M, Corazzari M, Rodolfo C, Bernassola F, et al. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5158–5167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovat PE, Ranalli M, Annichiarrico-Petruzzelli M, Bernassola F, Piacentini M, Malcolm AJ, et al. Exp Cell Res. 2000;260:50–60. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Umegaki H, Wang X, Abe R, Roth GS. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3756–3764. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone W, Perloff M, Crowell J, Sigman C, Higley H. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12:1829–1842. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.11.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer BJ, Metelitsa LS, Seeger RC, Cabot MC, Reynolds CP. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1138–1146. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin MM, Kumar S, McDonnell PC, Van Horn S, Lee JC, Livi GP, et al. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8488–8492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TT, Tran E, Nguyen TH, Do PT, Huynh TH, Huynh H. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:647–659. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osone S, Hosoi H, Kuwahara Y, Matsumoto Y, Iehara T, Sugimoto T. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:219–224. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poot M, Hosier S, Swisshelm K. Exp Cell Res. 2002;279:128–140. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1099–10100. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.13.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CP. Pediatr Transplant. 2004;8(Suppl 5):56–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-2265.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JD, Orrenius S. Toxicology. 2002;181–182:491–496. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00464-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse J, Cohen P, Trigon S, Morange M, Alonso-Llamazares A, Zamanillo D, et al. Cell. 1994;78:1027–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonwasser DC, Marais RM, Marshall CJ, Parker PJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:790–798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman R, Gitelman I, Sagi O, Horwitz SB, Wolfson M. Exp Cell Res. 2001;268:84–92. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K, Nakamura M, Ishida E, Kishi M, Konishi N. Mol Carcinogen. 2003;36:115–122. doi: 10.1002/mc.10107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K, Nakamura M, Ishida E, Kishi M, Yonehara S, Konishi N. Mol Carcinogen. 2002;35:127–137. doi: 10.1002/mc.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu M, Wang Y, Kentor R, Burke N, Watkins S, Kress G, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12200–12206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SY, Hail N, Jr, Lotan R. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:662–672. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SY, Li W, Yue P, Lippman SM, Hong WK, Lotan R. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2493–2498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Higuchi M, Proske RJ, Oridate N, Hong WK, Lotan R. Oncogene. 1999;18:6380–6387. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura Y, Simizu S, Osada H. FEBS Lett. 2004;569:249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobiume K, Matsuzawa A, Takahashi T, Nishitoh H, Morita K, Takeda K, et al. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:222–228. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournier C, Hess P, Yang DD, Xu J, Turner TK, Nimnual A, et al. Science. 2000;288:870–874. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5467.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traore K, Trush MA, George M, Jr, Spannhake EW, Anderson W, Asseffa A. Leuk Res. 2005;29:863–879. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruta F, Sunayama J, Mori Y, Hattori S, Shimizu S, Tsujimoto Y, et al. EMBO J. 2004;23:1889–1899. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda Y, Hirai S, Osada S, Suzuki A, Mizuno K, Ohno S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23512–23519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulukaya E, Pirianov G, Kurt MA, Wood EJ, Mehmet H. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:856–859. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39435–39443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won YK, Ong CN, Shen HM. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:2149–2156. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Choi S, Johnson DE, Vogel VG, Johnson CS, Trump DL, et al. Oncogene. 2004;23:5594–5606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao D, Singh SV. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3615–3619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K, Ichijo H, Korsmeyer SJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19 :8469–8478. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Rahmani M, Dent P, Grant S. Exp Cell Res. 2004;295:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Sanders BG, Kline K. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2483–2491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamzami N, Kroemer G. Curr Biol. 2003;13:R71–R73. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Shan P, Sasidhar M, Chupp GL, Flavell RA, Choi AM, et al. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:305–315. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0156OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]