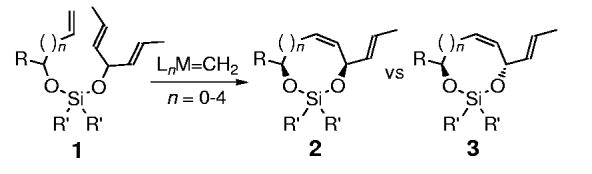

The ability to control stereochemistry in substrates where the reactive elements are distal represents a fundamentally important area of investigation that is commonly referred to as long-range asymmetric induction.[1,2] Although there are numerous examples of this phenomenon, a significant limitation with this type of process is the ability to predict the manner in which the chiral group attains proximity to the reactive site in order to translate stereochemical information. The inherent challenge associated with this requirement provided the incentive for the development of a new process where the elements of stereocontrol could be conserved in a predictable manner.[1,2] Herein, we describe a new approach to long-range asymmetric induction using the diastereoselective temporary silicon-tethered (TST) ring-closing-metathesis (RCM) reaction of mixed bisalkoxy silanes 1, derived from an allylic and prochiral alcohol, for the construction of cis-1,4-silaketals 2 (Scheme 1; n = 0). This methodology was also extended to higher homologues (where n=1-4), which resulted in the formation of the opposite trans diastereoisomer.[3-8]

Scheme 1.

General approach to the diastereoselective TST-RCM reactions with alkenyl and prochiral alcohols.

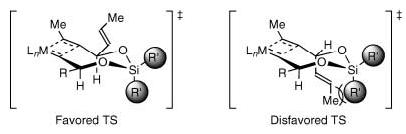

We envisioned that the TST-RCM of the mixed bisalkoxy silane 1 (Scheme 1; n = 0) should proceed through the favored transition state illustrated in Figure 1. The basis for this hypothesis was the assumption that the substituents (R’) on silicon would result in nonbonding interactions with the pseudoaxial propenyl moiety in the disfavored transition state, and thereby prefer the formation of the cis-1,4-silaketal 2. The potential advantage of this approach is that the reactive elements involved in diastereoselection are conserved irrespective of ring size, which should translate into a convenient stereochemical relay, provided the relative orientation of the substituents is maintained in the medium rings. Moreover, the ability for ring-closing metathesis to facilitate the formation of medium and large rings should allow the application of this concept to higher homologues.

Figure 1.

Proposed transition states for 1,4-stereocontrol in the TST-RCM reaction of an allylic alcohol.

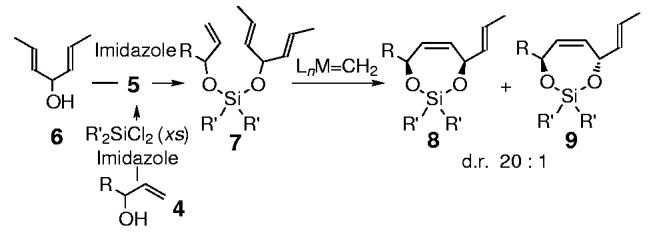

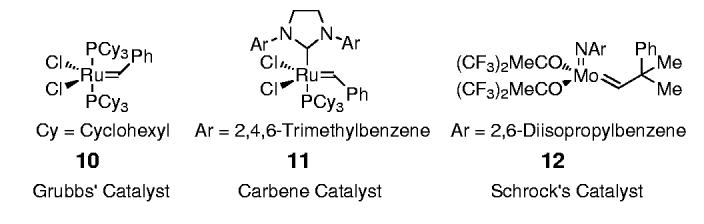

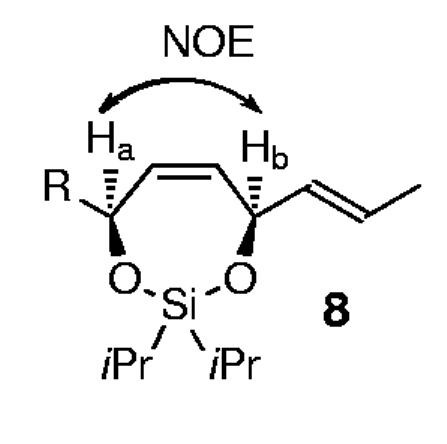

Preliminary studies examined the feasibility of this hypothesis for 1,4-stereocontrol (Scheme 2) through the examination of various substituents on silicon[9,10] and metal alkylidene catalysts,[11] as outlined in Table 1. Initial studies determined that the steric nature of the substituents on the silicon tether were indeed crucial in terms of silaketal construction, overall efficiency, and the level of diastereoselection, in which the diisopropylsilane proved optimal (Table 1; entry 3 versus 1 and 2). Treatment of the triene 7a (R=2-naphthyl (Np), R’ = iPr) with Grubbs' catalyst 10 at reflux in dichloromethane furnished the silaketals 8a and 9a in 75% yield, with ≥ 99:1 diastereoselectivity favoring 8a (Table 1; entry 3).[12] Additional studies explored the effects of more reactive metal alkylidene catalysts, in which the second-generation Grubbs catalyst 11 and the molybdenum-based Schrock catalyst 12 proved significantly inferior for this particular transformation (Table 1; entries 4 and 5).[11]

Scheme 2.

Preparation of bisalkoxy silanes 7 and the resulting diastereoselective TST-RCM reaction to form the cis-1,4-silaketals.

Table 1.

Optimization of the diastereoselective TST-RCM reaction with silicon tether 7a (R = Np).

| Entry | 7a; R′ = | Catalyst[a] | 8a:9a[b],[c] | Yield of 8a+9a [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Me | 10 | 23:1 | 41 |

| 2 | Ph | 10 | 15:1 | 70 |

| 3 | iPr | 10 | ≥99:1 | 75 |

| 4 | iPr | 11 | 6:1 | 31[d] |

| 5 | iPr | 12 | 14:1 | 23[e] |

All reactions (0.1 mmol) were carried out using 10 mol % of the catalyst in dichloromethane (0.05 m)at40 8C except for entry 5.

Ratios of diastereoisomers were determined by capillary GLC on aliquots of the crude reaction mixture.

Authentic standards were prepared independently from the corresponding 1,4-diols.

The more reactive second-generation catalyst proved less selective in furnishing significant amounts of polymeric and recovered starting material (30 %).

This reaction was carried out using 10 mol % catalyst in benzene (0.04 m) at room temperature.

Table 2 summarizes the scope of the TST-RCM, under the optimized reaction conditions (Table 1, entry 3). The construction of the mixed bisalkoxy silane 7 was achieved from the requisite allylic alcohol 4, through treatment with excess diisopropyldichlorosilane, to afford the monoalkoxychlorosilane 5, followed by the removal of the excess silylating agent and addition of the prochiral alcohol 6 (Scheme 2). The diastereoselective TST-RCM proved remarkably tolerant to a range of aryl, linear, and branched alkyl substituents (Table 2; entries 1-7), albeit with lower conversion for the α-branched allylic alcohol derivatives (Table 2; entry 4). Moreover, in nearly all cases the bisalkoxy silanes 7a—i were recovered and could be resubmitted to the reaction conditions. This transformation is also tolerant of both benzyloxymethyl and carboalkoxy substituents (Table 2; entries 8-9).[13]

Table 2.

Scope of the diastereoselective TST-RCM reaction (Scheme 2; R′ = iPr).

| Entry | 4; R = | Yield of 7 [%][a] | 8:9[b],[c],[d] | Yield of 8+9 [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Np (1a) | 88 | ≥99:1 | 75 |

| 2 | Ph (1b) | 76 | ≥99:1 | 90 |

| 3 | nPr (1c) | 71 | 29:1 | 66 |

| 4 | c-Hex (1d) | 85 | 22:1 | 54 |

| 5 | iBu (1e) | 77 | 34:1 | 73 |

| 6 | PhCH2 (1f) | 86 | 20:1 | 82 |

| 7 | Ph(CH2)2 (1g) | 85 | 32:1 | 66 |

| 8 | BnOCH2 (1h) | 72 | 41:1 | 61 |

| 9 | BnO2CCH2 (1i) | 72 | 40:1 | 73 |

The bisalkoxy silanes were prepared on a 0.5 mmol reaction scale using diisopropyldichlorosilane (10 equiv) and imidazole.

The meta-thesis reactions were carried out on a 0.05-0.1 mmol reaction scale (0.05 m) using 10-15 mol % of Grubbs' catalyst 10 in dichloromethane at 40 8C.

Ratios of diastereoisomers were determined by capillary GLC on aliquots of the crude reaction mixture.

The major stereoisomer was confirmed by nOe experiments in each case.12

|

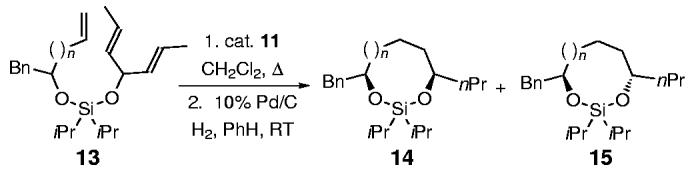

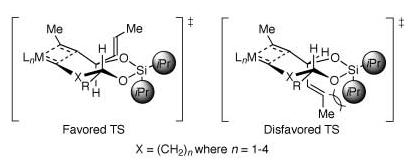

We envisioned that the application of diastereoselective TST-RCM to higher homologues would extend this concept, and provide a general method for long-range asymmetric induction. Table 3 summarizes the results of this study. Treatment of the trienes 13a—d with the second-generation Grubbs catalyst 11 in refluxing dichloromethane furnished, after hydrogenation, the saturated silaketal intermediates 14/15a—d, with the trans isomers 15a—d favored (Table 3; entries 1-4).[14] The unsaturated silaketals were reduced in this particular case to remove the E and Z isomers and simplify the stereochemical analysis. The origin of diastereoselectivity is consistent with the previous model, albeit with the caveat that the pseudoaxial/equatorial positions are reversed in the medium rings (Figure 2). Hence, the preferred transition state in the medium rings also places both substituents in pseudoequatorial positions, thus avoiding the steric interaction derived from the axial isopropyl group on the silicon tether.

Table 3.

Diastereoselective TST-RCM reactions with homologated alkenyl alcohols.

| Entry | Ring size n= | Yield of 13 [%][a] | 14:15b-[d] | Yield of 14+15 [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1(13a) | 92 | 1:11 | 90 |

| 2 | 2(13b) | 68 | 1:27 | 92 |

| 3 | 3(13c) | 75 | 1:3 | 75 |

| 4 | 4(13d) | 87 | 1:3 | 73 |

The bisalkoxy silanes were prepared on an analogous reaction scale to those in Table 2.

[b] The RCM reactions (0.1 mmol) were carried out using new Grubbs catalyst 11 (6 mol%) in dichloromethane (0.003M) at 40°C.[14]

Ratios of diastereoisomers were determined by capillary GLC on the saturated silaketals 14 and 15 after hydrogenation.

The major isomer was assigned by analogy to an independently prepared authentic sample.

Figure 2.

Proposed transition states for 1,n-stereocontrol in the TST-RCM reaction of homologated alkenyl alcohols (where n=1-4).

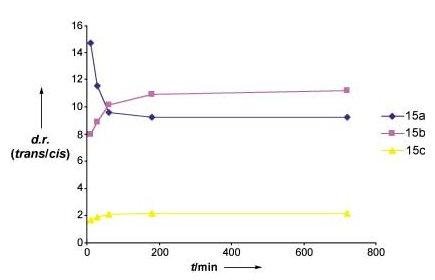

Additional studies demonstrated that the RCM is consistent with a kinetic reaction that affords the more thermodynamically stable product. Although there is evidence for reversibility in the formation of 15a and 15b, the trans isomer appears to be the major product throughout the course of the reaction, as outlined in Figure 3. Periodic analysis of the reaction revealed that the diastereoselectivity for 15a and 15b decreases and increases respectively with time at 95% conversion.[15] Hence, the level of stereocontrol in these reactions may be optimized accordingly. For example, the diastereoselectivity for the formation of 15a can be improved to approximately 18:1, provided the reaction is quenched after about 10 min at room temperature.

Figure 3.

Plot of diastereoselectivity with time for the TST-RCM reactions of 15a—c at min. 95% conversion. All aliquots were quenched with DMSO and directly hydrogenated prior to GLC analysis.

In conclusion, diastereoselective TST-RCM provides a useful approach to 1,4-, 1,5-, and 1,6-stereocontrol, and thus represents a new strategy for long-range asymmetric induction. This method facilitates the construction of cis-1,4-silaketals 8a—i (Scheme 1; d.r. ≥20:1), whereas the extension of this concept to homologated alkenyl alcohols (Table 3; n = 1-4), results in reversal in diastereoselectivity favoring the trans isomers 15a—d. The ability to systematically examine medium-ring stereocontrol in this manner should provide a greater understanding of the conformational factors that control diastereoselection in these systems.

|

|

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We sincerely thank the National Institutes of Health (GM54623) for generous financial support. We also thank Johnson and Johnson for a Focused Giving Award, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals for the Creativity in Organic Chemistry Award, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals for an Academic Achievement Award. The Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation is thanked for a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award (P.A.E.).

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- [1]. For recent reviews on long-range asymmetric induction, see:; a) Sailes H, Whiting A. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 2000:1785–1805. [Google Scholar]; b) Mikami K, Shimizu M, Zhang H-C, Maryanoff BE.Tetrahedron 2001572917–2951.and references therein [Google Scholar]

- [2]. For recent examples of long-range asymmetric induction, see:; a) Date M, Tamai Y, Hattori T, Takayama H, Kamikubo Y, Miyano S. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 2001:645–653. [Google Scholar]; b) Hudson RDA, Anson CE, Mahon MF, Stephenson GR. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001;630:88–103. [Google Scholar]; c) O'Malley SJ, Leighton JL. Angew. Chem. 2001;113:2999–3001. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:2915–2917. [Google Scholar]; d) Carson MW, Kim G, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem. 2001;113:4585–4588. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011203)40:23<4453::aid-anie4453>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:4453–4456. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011203)40:23<4453::aid-anie4453>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Flamme EM, Roush WR.J. Am. Chem. Soc 200212413644–13645.and references therein [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. For recent reviews on ring-closing metathesis, see:; a) Grubbs RH, Chang S. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:4413–4450. [Google Scholar]; b) Pandit UK, Overkleeft HS, Borer BC, Bieräugel H. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999:959–968. [Google Scholar]; c) Fürstner A. Angew. Chem. 2000;112:3140–3172. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2000393012–3043.and references therein [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fu GC, Grubbs RH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5426–5427. [Google Scholar]

- [5]. For a stereospecific approach to C2-symmetrical 1,4-diols, see:; a) Evans PA, Murthy VS. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:6768–6769. doi: 10.1021/jo9811524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lobbel M, Köll P. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2000;11:393–396. [Google Scholar]

- [6]. For examples of silicon-tethered ring-closing-metathesis cross-coupling reactions, see:; a) Hoye TR, Promo MA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:1429–1432. [Google Scholar]; b) Boiteau J-G, Van deWeghe P, Eustache J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:239–242. [Google Scholar]; c) Harrison BA, Verdine GL. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2157–2159. doi: 10.1021/ol0159569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. For a related example of an enantioselective RCM using a prochiral alcohol, see:; Kiely AF, Jernelius JA, Schrock RR, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:2868–2869. doi: 10.1021/ja012679s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. For examples of diastereoselective ring-closing-metathesis reactions, see:; a) Huwe CM, Velder J, Blechert S. Angew. Chem. 1996;108:2542–2544. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1996;35:2376–2378. [Google Scholar]; b) Burke SD, Müller M, Beaudry CM. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1827–1829. doi: 10.1021/ol9910971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Oguri H, Sasaki S-Y, Oishi T, Hirama M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:5405–5408. [Google Scholar]; d) Lautens M, Hughes G. Angew. Chem. 1999;111:160–162. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:129–131. [Google Scholar]; e) Lloyd-Jones GC, Murray M, Stentiford RA, Worthington PA. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2000:975–985. [Google Scholar]; f) Wallace DJ, Cowden CJ, Kennedy DJ, Ashwood MS, Cottrell IF, Dolling U-H. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:2027–2029. [Google Scholar]; g) Schmidt B, Westhus M. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:2421–2426. [Google Scholar]; h) Stoianova DS, Hanson PR. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1769–1772. doi: 10.1021/ol005952o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Fukuda Y, Sasaki H, Shindo M, Shishido K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:2047–2049. [Google Scholar]; j) Ogasawara M, Nagano T, Hayashi T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9068–9069. doi: 10.1021/ja026401r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. For reviews on temporary silicon-tethered strategies, see:; a) Fensterbank L, Malacria M, Sieburth SM. Synthesis. 1997:813–854. [Google Scholar]; b) Gauthier DR, Jr., Zandi KS, Shea KJ. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:2289–2338. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sieburth SM, Fensterbank L. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:5279–5281. [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Schrock RR, Murdzek JS, Bazan GC, Robbins J, DiMare M, O'Regan M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:3875–3886. [Google Scholar]; b) Schwab P, Grubbs RH, Ziller JW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:100–110. [Google Scholar]; c) Scholl M, Ding S, Lee CW, Grubbs RH. Org. Lett. 1999;1:953–956. doi: 10.1021/ol990909q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].The major stereoisomer was confirmed from nOe experiments in each case (8a-i). Details are available in the Supporting Information

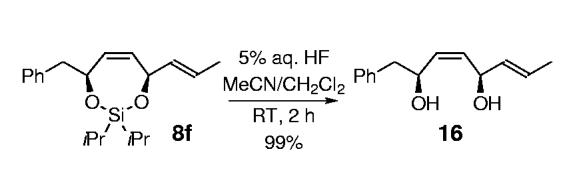

- [13].The silyl tether can be readily removed in each case to afford the corresponding diol. For example, treatment of 8f with 5% aqueous HF at room temperature furnished the bisallylic 1,4-diol 16 in 99% yield

- [14].Although Grubbs' catalyst 10 was not optimal for the larger rings, it also furnished 15 as the major diastereoisomer, which confirmed that the catalyst was not responsible for the reversal in selectivity

- [15].The diastereoselectivities in Figure 3, refer to crude product ratios, whereas the selectivities in Table 3 are for the purified silaketals 14a-d and 15a-d

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.