Abstract

Stress-induced Hfq-binding small RNAs of Escherichia coli, SgrS and RyhB, down-regulate the expression of target mRNAs through base-pairing. These small RNAs form ribonucleoprotein complexes with Hfq and RNase E. The regulatory outcomes of the RNase E/Hfq/small RNA-containing ribonucleoprotein complex (sRNP) are rapid degradation of target mRNAs and translational inhibition. Here, we ask to what extent the sRNP-mediated mRNA destabilization contributes to the overall silencing of target genes by using strains in which the rapid degradation of mRNA no longer occurs. We demonstrate that translational repression occurs in the absence of sRNP-mediated mRNA destabilization. We conclude that translational repression is sufficient for gene silencing by sRNP. One possible physiological role of mRNA degradation mediated by sRNP is to rid the cell of translationally inactive mRNAs, making gene silencing irreversible.

Keywords: bacterial small RNA-containing ribonucleoprotein complex, Hfq, mRNA degradation, RNase E, glucose transporter

Increasing numbers of small noncoding RNAs are showing up as regulators of gene expression in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. In Escherichia coli, the members of a major class of these RNAs act with the help of the RNA chaperone Hfq to regulate translation and/or stability of target mRNAs through base-pairing (1–4). SgrS and RyhB are two examples that have been shown to mediate destabilization of target mRNAs in an RNase E-dependent manner. SgrS, whose expression is induced in response to phosphosugar stress, acts on the glucose-specific transporter of the phosphotransferase system (ptsG) mRNA encoding a major glucose transporter (5, 6), whereas RyhB, whose expression is induced in response to Fe depletion, acts on several mRNAs encoding Fe-binding proteins (7, 8). We have discovered recently that both SgrS and RyhB RNAs form complexes with RNase E through Hfq (9). The ribonucleoprotein complex consisting of Hfq, RNase E, and SgrS or RyhB RNA can be called sRNP (small RNA-containing ribonucleoprotein complex) that specifically down-regulates target genes at posttranscriptional levels through RNA–RNA base-pairing.

Although it is firmly established that the bacterial sRNP acts to destabilize target mRNAs, it is not yet clear to what extent the sRNP-dependent mRNA destabilization contributes to the overall silencing of target genes. In other words, it has not been tested experimentally whether sRNP could inhibit the translation of target mRNAs independently from mRNA destabilization in vivo. These two events are intimately coupled; mRNA degradation will certainly cause loss of translation, and inhibition of translation can lead to destabilization of an mRNA by exposing it to RNases (10, 11). Thus, the relative roles of direct translational repression and mRNA destabilization in gene silencing mediated by bacterial sRNP is a chicken-or-egg question: which is the primary event? Previously, we found that the truncated RNase E lacking the C-terminal scaffold region no longer supports the rapid degradation of target mRNAs mediated by SgrS or RyhB RNA (9, 12). This finding has provided us with an excellent opportunity to examine experimentally this important question. In the present study, we address the question of how sRNP-mediated mRNA destabilization contributes to the overall gene silencing of target genes. We demonstrate that translational repression of target mRNAs occurs in the absence of the rapid mRNA destabilization. The logical conclusion is that translational repression is sufficient for gene silencing by bacterial sRNP. One possible physiological role of mRNA degradation mediated by sRNP containing RNase E would be to get rid of the translationally inactive mRNAs, making gene silencing irreversible.

Results

SgrS-Mediated Gene Silencing of ptsG Occurs in Cells Carrying the Truncated rne Gene.

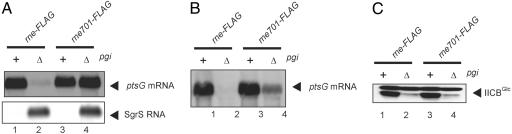

The addition of glucose to cells lacking phosphoglucose isomerase (pgi) or the addition of α-methylglucoside (αMG) to wild-type cells rapidly generates phosphosugar stress, resulting in induction of SgrS, which in turn leads to destabilization of ptsG mRNA (5, 13). The rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA under phosphosugar stress no longer occurs in cells carrying rne701 encoding a truncated RNase E missing the C-terminal scaffold region (9, 12). To evaluate the contribution of the rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA mediated by SgrS to gene silencing, four different strains (rne-FLAG, rne701-FLAG, Δpgi rne-FLAG, and Δpgi rne701-FLAG) were grown in LB medium and exposed to glucose for 20 min. We showed previously that the C-terminal FLAG tag does not affect the activity of either full-length or truncated RNase E (9). Total RNAs were prepared and subjected to Northern blotting with the ptsG probe. The ptsG mRNA was stably expressed in both the rne-FLAG and rne701-FLAG cells in the pgi+ background (nonstress condition: no induction of SgrS) (Fig. 1A, lanes 1 and 3). Little full-length ptsG mRNA was detected in Δpgi rne-FLAG (stress condition: induction of SgrS) because of the rapid destruction mediated by sRNP containing SgrS, whereas the ptsG mRNA was well expressed in Δpgi rne701-FLAG cells (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 4). These results are consistent with the previous results (9, 12). Because 20 min is not enough time to see the effect of phosphosugar stress on the expression of IICBGlc, the four strains were further exposed to glucose for 2 h. Total RNAs were prepared and subjected to Northern blotting. Again, little full-length ptsG mRNA was detected in Δpgi rne-FLAG, whereas the ptsG mRNA was still expressed in Δpgi rne701-FLAG cells although at a reduced level (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 4). The reduction of ptsG mRNA by long-term (2 h) glucose exposure in Δpgi rne701-FLAG cells suggests that prolonged phosphosugar stress affects the expression and/or stability of ptsG mRNA by some mechanisms that do not require the C-terminal scaffold region of RNase E.

Fig. 1.

The SgrS-mediated repression of IICBGlc occurs without recruitment of RNase E to the ptsG mRNA. (A) Effect of short-term phosphosugar stress on ptsG mRNA. TM338 (rne-FLAG), TM339 (Δpgi rne-FLAG), TM528 (rne701-FLAG), and TM525 (Δpgi rne701-FLAG) were grown in LB medium to A600 = 0.5. To each culture, 0.4% glucose was added, and incubation was continued for 20 min. Total RNAs were prepared, and each RNA sample (10 or 5 μg) was subjected to Northern blotting with ptsG or sgrS probes. (B) Effect of long-term phosphosugar stress on ptsG mRNA. Cells were grown in LB medium to A600 = 0.1. To each culture, 0.4% glucose was added, and incubation was continued for 2 h. Total RNAs were prepared, and each RNA sample (10 μg) was subjected to Northern blotting with ptsG probe. (C) Effect of long-term phosphosugar stress on IICBGlc expression. Cells were grown in LB medium to A600 = 0.1. To each culture, 0.4% glucose was added, and incubation was continued for 2 h. Crude extracts were prepared, and each protein sample corresponding to 0.04 A600 was loaded on the gel and subjected to Western blotting with anti-IIBGlc antibody.

We next analyzed the effect of phosphosugar stress on IICBGlc expression. Crude extracts were prepared from cells exposed to glucose for 2 h and subjected to Western blotting for IIBGlc. IICBGlc was stably expressed in both the rne-FLAG and rne701-FLAG cells in the pgi+ background (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 3). The level of IICBGlc was dramatically reduced in Δpgi rne-FLAG cells exposed to glucose because of the action of SgrS (Fig. 1C, lane 2). Interestingly, the expression of IICBGlc was still strongly inhibited in Δpgi rne701-FLAG cells expressing the C-terminally truncated RNase E-FLAG (Fig. 1C, lane 4). A more quantitative analysis of IICBGlc level indicated that the phosphosugar stress causes ≈10- to 20-fold reduction of IICBGlc levels in both rne-FLAG and rne701-FLAG cells under this condition (data not shown). These results suggest that SgrS inhibits the translation of ptsG mRNA in the absence of rapid message degradation.

SgrS Inhibits the Translation of ptsG mRNA.

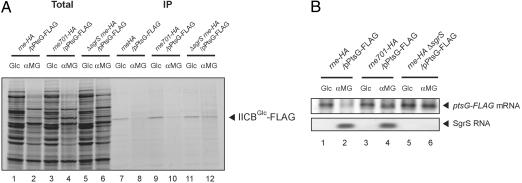

To examine directly the effect of the SgrS-mediated rapid mRNA destabilization on translation, we analyzed biosynthesis of IICBGlc by pulse-labeling and immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments just after the induction of phosphosugar stress where no reduction of ptsG mRNA is expected to occur. For this process, we first constructed a ptsG-FLAG gene encoding the C-terminally FLAG-tagged IICBGlc. The plasmid-borne ptsG-FLAG gene was introduced in three different strains (rne-HA, rne701-HA, and rne-HA ΔsgrS). As previously shown, the C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA) tag does not affect the activity of either full-length or truncated RNase E (9). In addition, we confirmed that the ptsG-FLAG allele could rescue perfectly the ΔptsG cells, indicating that the C-terminal FLAG tag does not affect significantly the activity of IICBGlc (data not shown). Cells were grown in M9-glycerol medium without methionine and exposed to either glucose or αMG for 10 min. Then, cells were treated with [35S]methionine for 1 min, and the total proteins were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. A marked difference was observed in the profile of newly synthesized proteins between the normal (+glucose) and stress (+αMG) conditions, indicating that the phosphosugar stress causes a global translational effect (Fig. 2A, lanes 1–6). The total proteins were also subjected to IP assay with anti-FLAG beads. The proteins bound to the beads were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. A significant amount of 35S-IICBGlc was detected in all three strains when exposed to glucose (Fig. 2A, lanes 7, 9, and 11). On the other hand, the amount of 35S-IICBGlc was markedly reduced in rne-HA cells (Fig. 2A, lane 8) but not in cells lacking SgrS (Fig. 2A, lane 12) when exposed to αMG. These results imply that the stress-induced SgrS efficiently inhibits the translation of ptsG mRNA. Importantly, a significant reduction of 35S-IICBGlc was also observed in rne701 cells exposed to αMG (Fig. 2A, lane 10). We also examined the effect of the addition of αMG on IICBGlc present before the stress by Western blotting. No significant reduction of IICBGlc level was observed in response to the addition of αMG, suggesting that phosphosugar stress and SgrS do not affect the stability of IICBGlc protein itself (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

SgrS inhibits the translation of IICBGlc in the absence of the RNase E-dependent rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA. TM641 (nre-HA), TM642 (rne701-HA), and TM666 (rne-HA ΔsgrS) harboring pPtsG-FLAG were grown until A600 = 0.4 in M9–0.4% glycerol medium without methionine. To each culture, 0.01% glucose or αMG was added, and incubation was continued for 10 min. (A) Each culture was exposed to [35S]methionine for 1 min and subjected to IP experiments as described in Materials and Methods. The crude extract (Total; lanes 1–6) and bound fraction (IP; lanes 7–12) corresponding to 0.04 or 0.12 A600 unit, respectively, were analyzed by 12% SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. (B) Total RNAs were prepared before the treatment with [35S]methionine. Each RNA sample (0.5 or 5 μg) was subjected to Northern blotting with ptsG or sgrS probe.

We analyzed ptsG mRNA by Northern blotting under the same conditions used for the pulse-labeling experiment. As expected, the addition of αMG, but not glucose, caused both the induction of SgrS and the destabilization of the ptsG-FLAG mRNA in the rne-HA cells (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 2). The destabilization of the ptsG-FLAG mRNA no longer occurred in rne701-HA cells despite normal induction of SgrS (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4). Neither the induction of SgrS nor the destabilization of the ptsG-FLAG mRNA occurred in rne-HA ΔsgrS cells (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 and 6). These results indicate that the mRNA expressed from the plasmid-borne ptsG-FLAG gene is normally regulated by the stress-induced SgrS. Taken together, we conclude that SgrS down-regulates the IICBGlc expression by directly inhibiting its translation, and the rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA is not required for the translational repression.

Inactivation of RNase E Does Not Affect the Translational Inhibition by SgrS.

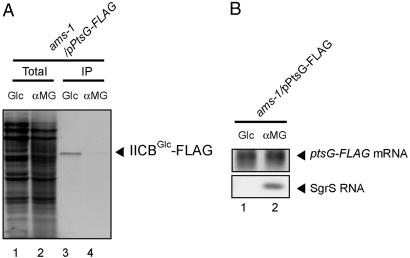

To confirm the conclusion mentioned above, we examined the effect of inactivation of RNase E on the translational inhibition of ptsG mRNA by SgrS. The ptsG-FLAG allele was moved to the ams1 strain that expresses a temperature-sensitive RNase E. The resulting strain was grown in M9-glycerol medium without methionine at 30°C to the midlog phase. Either glucose or αMG was added to the culture and incubation was continued for 20 min at either 30°C or 42°C. Then, the cells were treated with [35S]methionine for 1 min. Total proteins were prepared and immunoprecipitated by using anti-FLAG beads. Total RNAs were also prepared from cells before treatment with [35S]methionine and subjected to Northern blotting. Both 35S-IICBGlc and ptsG-FLAG mRNA were detected when exposed to glucose, whereas the amount of 35S-IICBGlc, but not the ptsG mRNA, was markedly reduced when exposed to αMG (Fig. 3). We also confirmed that the induction of SgrS occurs normally in the ams1 strain under the stress condition (Fig. 3B). These results again indicate that the RNase E-dependent rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA is not required for the translational repression mediated by SgrS.

Fig. 3.

The TM151 (ams1) cells harboring pPtsG-FLAG were grown to A600 = 0.4 at 30°C in M9–0.4% glycerol medium without methionine. To each culture, 0.01% glucose or αMG was added, and incubation was continued for 15 min at 42°C. Each culture was exposed to [35S]methionine for 1 min and subjected to an IP experiment as described in Materials and Methods. (A) The crude extract (Total; lanes 1 and 2) and bound fraction (IP; lanes 3 and 4) corresponding to 0.04 or 0.12 A600 unit, respectively, were analyzed by 12% SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. (B) Total RNAs were prepared before the treatment with [35S]methionine. Each RNA sample (0.5 or 5 μg) was subjected to Northern blotting with ptsG or sgrS probe.

The Rapid Degradation of ptsG mRNA Mediated by SgrS Occurs in the Absence of Translation.

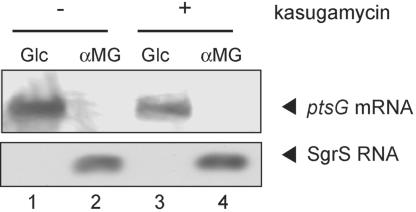

We showed previously that the rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA mediated by SgrS occurs efficiently even when its translation is slowed down by introducing a point mutation in the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (6). This finding suggested that the mRNA destabilization effect of SgrS is independent of translation. To test whether this is the case, we examined the effect of blocking translation on SgrS action. We first confirmed by Northern blotting that SgrS is efficiently induced, resulting in the rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA after the addition of αMG to the wild-type strain growing in LB medium (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2). Next, wild-type cells were grown in LB medium and treated with kasugamycin to block translation initiation. The antibiotic kasugamycin is known to inhibit the initial step of translation (14). In fact, the kasugamycin treatment completely inhibited cell growth (data not shown). Then, cells were exposed to either glucose or αMG for 20 min. Total RNA was prepared and subjected to Northern blotting. The full-length of ptsG mRNA was still detectable even after treatment with kasugamycin in the presence of glucose (Fig. 4, lane 3). Importantly, kasugamycin affected neither the induction of SgrS nor the rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA in the presence of αMG (Fig. 4, lane 4). These results suggest that SgrS may act to destabilize the ptsG mRNA in the absence of translation.

Fig. 4.

Effect of kasugamycin on the rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA. Wild-type IT1568 cells were grown in LB medium to OD600 = 0.3. Cells were exposed to kasugamycin (300 μg/ml) for 30 min, and then to either 0.4% glucose or αMG for 15 min. Total cellular RNAs were isolated and subjected to Northern blot analysis by using the ptsG or sgrS probe (lanes 3 and 4). Total cellular RNAs were also isolated from cells exposed to glucose or αMG without kasugamycin treatment and subjected to Northern blot analysis (lanes 1 and 2). Each RNA sample (10 or 5 μg) was used to detect ptsG or sgrS mRNA.

Physiological Roles of the Translation Inhibition and Destabilization of ptsG mRNA Under the Stress Condition.

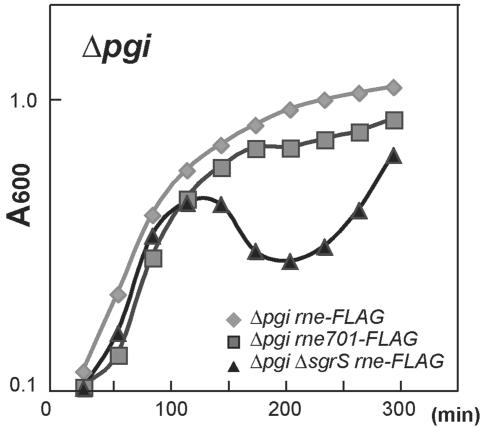

The physiological relevance of the down-regulation of ptsG mRNA by SgrS under the stress condition would be to prevent the accumulation of potentially toxic metabolic intermediates. In fact, we demonstrated previously that the uptake of glucose causes a strong, but transient, growth retardation in pgi mlc cells in which IICBGlc protein is highly expressed before the cells are exposed to glucose, although how the accumulation of glucose-6-P causes growth inhibition remains to be studied (15). To evaluate the physiological roles of the translational inhibition and destabilization of ptsG mRNA mediated by SgrS, we examined the effects of ΔsgrS and rne701 mutations on cell growth under both normal and stress conditions. Cells were grown in LB medium containing glucose. The ΔsgrS and rne701 mutations do not significantly affect cell growth in the pgi+ background (data not shown). On the other hand, the ΔsgrS mutation induced a serious growth defect in the Δpgi background because of the metabolic stress caused by G6P accumulation (Fig. 5). This observation is essentially consistent with the finding by Vanderpool and Gottesman (5) that cells lacking SgrS grew very slowly after the addition of αMG. Thus, the down-regulation of ptsG mRNA mediated by SgrS is an important cellular response to the metabolic stress. We also examined the effect of the rne701 mutation on cell growth in the Δpgi background. Interestingly, the rne701 mutation caused a moderate growth inhibition in Δpgi background (Fig. 5), which suggests that the rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA also plays some physiological roles under the stress condition, presumably by rapidly removing the translationally repressed mRNAs.

Fig. 5.

Effect of C-terminal truncation of RNase E and the sgrS deletion on the cell growth. Overnight cultures of TM339 (Δpgi rne-FLAG), TM525 (Δpgi rne701-FLAG), and TM671 (Δpgi rne-FLAG ΔsgrS) were 100-folded diluted and grown in LB medium containing 0.4% glucose. Cell growth was monitored by measuring OD at 600 nm.

RyhB-Mediated Gene Silencing of sodB Occurs in Cells Carrying the Truncated rne Gene.

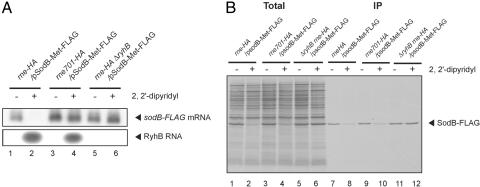

The studies on the ptsG mRNA silencing by SgrS strongly suggests that RyhB-mediated gene silencing of sodB also occurs in cells carrying the truncated rne gene. To determine whether this is the case, we first modified the plasmid-borne sodB gene to encode SodB-2xMet-FLAG protein in which two methionine sequences and a FLAG sequence were attached to the C terminus of SodB. The addition of 2xMet is to enhance its labeling with [35S]methionine because the wild-type SodB protein does not contain any internal methionine residues. This plasmid was introduced into three different strains (rne-HA, rne701-HA, and ΔryhB rne-HA). Cells were grown in M9-glycerol medium containing 10 μM FeSO4 without methionine and treated with 2,2′-dipyridyl for 10 min to deplete Fe2+. As shown in Fig. 6A, upon the addition of 2,2′-dipyridyl, RyhB RNA was induced, resulting in the destabilization of sodB mRNA. The degradation of sodB mRNA was essentially suppressed in the Δryh B strain or the rne701-FLAG strain (Fig. 6A, lanes 3–6). These results are consistent with the previous data and suggest that RyhB destabilizes the sodB mRNA by recruiting RNase E to the message (7, 9). To test whether RyhB RNA inhibits sodB translation, the biosynthesis of SodB-2xMet-FLAG protein was examined by pulse-labeling and IP experiments. After the addition of 2,2′-dipyridyl, cells were treated with [35S]methionine for 1 min. The total proteins (Fig. 6B, lanes 1–6) and proteins bound to the anti-FLAG beads (Fig. 6B, lanes 7–12) were analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography. A significant amount of 35S-SodB-2xMet-FLAG was detected in all three strains without treatment with 2,2′-dipyridyl (Fig. 6B, lanes 7, 9, and 11). On the other hand, the amount of 35S-SodB-2xMet-FLAG was markedly reduced in wild-type cells but not in cells lacking RyhB when treated with 2,2′-dipyridyl (Fig. 6B, lanes 8 and 12). This finding implies that the stress-induced RyhB efficiently inhibits the translation of sodB mRNA. The reduction of 35S-SodB-2xMet-FLAG was also observed in rne701 cells exposed to 2,2′-dipyridyl (Fig. 6B, lane 10). These results imply that RyhB down-regulates SodB expression by directly inhibiting its translation, and the rapid destruction of sodB mRNA is not required for the reduced synthesis of SodB.

Fig. 6.

RyhB inhibits the translation of SodB in the absence of the RNase E-dependent rapid degradation of sodB mRNA. TM641 (nre-HA), TM642 (rne701-HA), and TM667 (rne-HA ΔryhB) harboring pTM31 (pSodB-Met2-FLAG) were grown until A600 = 0.4 in M9–0.4% glycerol medium containing 10 μM FeSO4 without methionine. Then, 250 μM 2,2′-dipyridyl was added to each culture, and incubation was continued for 10 min. (A) The cellular RNAs were prepared, and each RNA sample (0.5 or 5 μg) was subjected to Northern blotting with sodB or ryhB probe. (B) Each culture was treated with [35S]methionine for 1 min and subjected to IP experiments as described in Materials and Methods. The crude extract (Total; lanes 1, 2) and bound fraction (IP; lanes 3, 4) corresponding to 0.02 and 0.04 A600 unit, respectively, were analyzed by 15% SDS/PAGE followed by autoradiography.

Discussion

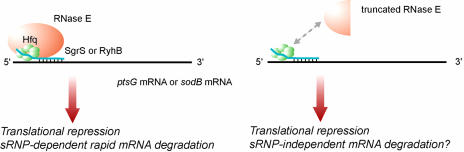

The major finding in the current study is that the down-regulation of target mRNAs by sRNP containing SgrS or RyhB occurs without the RNase E-dependent rapid degradation of mRNAs (Figs. 1, 2, 3, and 6). In other words, sRNP-mediated translational repression of target mRNAs can occur independently from message destabilization, which has led us to conclude that direct translational repression is sufficient for gene silencing by sRNP. We also showed that sRNP-mediated mRNA destabilization is probably an independent process from translational repression although both events occur simultaneously in normal cells in which sRNP consisting of a small RNA, Hfq, and RNase E is formed (Fig. 4). Although it is still possible that the rapid degradation of mRNAs mediated by sRNP containing SgrS or RyhB contributes to some extent to overall gene silencing, one possible role of the rapid destabilization of target mRNAs by sRNP is to eliminate translationally inactive mRNAs to make gene silencing irreversible. We also observed that the prolonged exposure to phosphosugar stress significantly reduces the expression of ptsG mRNA. This observation simply suggests that a particular mRNA becomes susceptible to degradation without small RNA-mediated recruitment of RNase E whenever its translation is blocked. In other words, sRNP-independent mRNA destabilization may be coupled with translational repression. We depict a model concerning the mechanism of sRNP in Fig. 7 that incorporates these observations.

Fig. 7.

Model for gene silencing by sRNP. (Left) Ribonucleoprotein complex consisting of Hfq, RNase E, and SgrS or RyhB (sRNP) acts on the target mRNA through base-pairing, resulting in translational repression and rapid mRNA degradation that requires RNase E within sRNP. (Right) Ribonucleoprotein complex lacking RNase E could act on the target mRNA to cause translational inhibition without the rapid degradation of mRNA. The translational inhibition may lead to the gradual destabilization of target mRNAs that does not depend on RNase E within sRNP.

Several Hfq-binding small RNAs, such as MicF and OxsS, are known to act to inhibit the translation of target mRNAs (2, 3). It is apparent that many uncharacterized Hfq-binding small RNAs also act to inhibit the translation of target mRNAs. For example, it has reported recently that one of the uncharacterized Hfq-binding small RNAs, MicA/SraD, is involved in silencing of a target ompA mRNA by inhibiting its translation through base-pairing (16, 17). It remains to be studied whether these RNAs form ribonucleoprotein complexes with RNase E through Hfq to destabilize the target mRNAs. However, if so, it is highly possible that the present conclusion regarding the relationship between translational repression and mRNA degradation is applicable to the mechanism of other Hfq-binding small RNAs because these RNAs apparently base-pair with the translational initiation region of target mRNAs. An interesting question is whether sRNP is able to down-regulate the target mRNA primarily through mRNA destabilization. This mechanism would be theoretically possible if base-pairing does not occlude the translation initiation region.

Our finding regarding the relative contribution of translational repression and mRNA degradation to gene silencing caused by sRNP could be relevant to the mechanism of gene silencing mediated by eukaryotic microRNA (miRNA)/RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The prevailing view for gene regulation by miRNA/RISC is that partial base-pairing between a miRNA and its target mRNA results in translational repression without mRNA degradation, whereas perfect base-pairing between two RNAs induces mRNA degradation (18–20). However, this view has been challenged recently (21, 22). In particular, it should be noted that the founding members of miRNA, Caenorhabditis elegans lin-4 and let-7, have been shown to result in degradation of target mRNAs despite the fact that they can only partially base-pair with the target mRNAs (21). Thus, the regulatory outcomes of miRNA/RISC are quite similar with those of sRNP in E. coli although the mechanisms of translational inhibition and mRNA degradation exerted by miRNA/RISC are not yet well understood. In addition, it would be interesting to examine whether translational repression contributes to overall gene silencing in the RNA interference pathway where small interfering RNA/RISC-mediated mRNA destruction is believed to be the major event.

Materials and Methods

Media and Growth Conditions.

Cells were grown aerobically in LB or M9 medium supplemented with the indicated sugars and compounds at 37°C unless specified. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations when needed: chloramphenicol (15 μg/ml) and kanamycin (15 μg/ml). Bacterial growth was monitored by determining the OD at 600 nm.

Strains and Plasmids.

The E. coli K12 strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. IT1568 (23) was used as a parent wild-type strain. The rne-HA-cat and rne-FLAG-cat alleles of TM642 (9) and TM338 (12) were moved to TM452 (9) by P1 transduction to construct TM666 [Δ(sgrS-sgrR) rne-HA-cat] and TM634 [Δ(sgrS-sgrR) rne-FLAG-cat], respectively. The ams1 allele of GW20 (24) was moved to IT1568 by P1 transduction to constructed TM151. TS7 (ΔryhB::cat) was constructed from IT1568 by one-step gene inactivation protocol (25). TM635 was constructed from TS7 by eliminating the cat marker. The rne-HA-cat allele of TM642 was moved to TM635 by P1 transduction to construct TM667 (ΔryhB rne-HA-cat). The Δ(sgrS-sgrR)::cat allele of TM540 (6) was moved to TM224 (12) to construct TM541 (Δpgi (Δ(sgrS-sgrR)::cat). TM670 was constructed from TM541 by eliminating the cat marker. The rne-FLAG-cat allele of TM338 was moved to TM670 by P1 transduction to construct TM671 [Δpgi (Δ(sgrS-sgrR) rne-FLAG-cat].

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Relevant genotype and property | Source/reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strain | ||

| IT1568 | W3110mlc | 23 |

| TM338 | W3110mlc rne-FLAG-cat | 12 |

| TM339 | W3110mlc Δpgi rne-FLAG-cat | 12 |

| TM528 | W3110mlc rne701-FLAG-cat | 12 |

| TM525 | W3110mlc Δpgi rne701-FLAG-cat | 12 |

| TM641 | W3110mlc rne-HA-cat | 9 |

| TM642 | W3110mlc rne701-HA-cat | 9 |

| TM452 | W3110mlcrne-FLAG cat-PBAD-eno | 9 |

| TM542 | W3110mlc Δ(sgrS-sgrR) | 6 |

| TM666 | W3110mlc Δ(sgrS-sgrR) rne-HA-cat | This study |

| GW20 | W3110ams1 zce726::Tn10 | 24 |

| TM151 | W3110mlc ams1 zce726::Tn10 | This study |

| TS7 | W3110mlc Δ ryhB::cat | This study |

| TM635 | W3110mlc Δ ryhB | This study |

| TM667 | W3110mlc Δ ryhB rne-HA-cat | This study |

| TM634 | W3110mlc Δ(sgrS-sgrR) rne-FLAG-cat | This study |

| TM224 | W3110mlc Δpgi | 23 |

| TM540 | W3110mlc Δ(sgrS-sgrR)::cat | 6 |

| TM541 | W3110mlc Δpgi Δ(sgrS-sgrR)::cat | This study |

| TM670 | W3110mlc Δpgi Δ(sgrS-sgrR) | This study |

| TM671 | W3110mlc Δpgi Δ(sgrS-sgrR) rne-FLAG-cat | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pPtsG-FLAG | Derivative of pMW218 carrying ptsG-FLAG | This study |

| pSodB-Met-FLAG | Derivative of pMW218 carrying sodB-Met2-FLAG | This study |

Plasmids pPtsG-FLAG and pSodB-Met-FLAG were constucted by inserting a PCR-amplified DNA fragment carrying ptsG-FLAG or sodB-Met2-FLAG sequence into BamHI/HindIII sites of pMW218 (Nippon Gene, Tokyo), respectively.

Western Blotting.

The sample was heated at 100°C for 5 min and subjected to a 12% or 15% polyacrylamide-0.1% SDS gel electrophoresis and transferred to Immobilon membrane (Millipore). The membranes were treated with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma), anti-IIBGlc, or anti-HA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) polyclonal antibodies. Signals were visualized by the ECL system (Amersham Pharmacia). Anti-IIBGlc polyclonal antibody has been described (26).

Pulse Labeling and IP.

Cells were grown in M9–0.4% glycerol medium supplemented with 19 aa except methionine (50 μg/ml each) and appropriate antibiotics to maintain the plasmids. At A600 = 0.4, cells were treated as described in the figure legends. Each cell culture of 400 μl was pulse-labeled with 0.1 nmol (37 kBq) of [35S]methionine (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences) for 1 min. Then, cells were treated with trichloroacetic acid (final concentration 5%). The precipitates were collected by centrifugation, washed with acetone, dissolved in 40 μl SDS-EDTA buffer (1% SDS/20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0/0.1 mM EDTA), and used directly as total proteins. For IP experiments, a portion (30 μl) of each sample was mixed with 0.5 ml of IP buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0/0.1 M KCl/5 mM MgCl2/10% glycerol/0.1% Tween20) containing Complete Mini (Roche Diagnostics) and 20 μl of anti-FLAG M2-agarose suspension (Sigma). The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 1 min. The pellet beads were washed two times with 1 ml of IP buffer by centrifugation. The proteins bound to the beads were eluted with 15 μl of SDS sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min and used as IP sample. The total protein and IP samples were subjected to 12% and 15% SDS/PAGE gel for detection of IICBGlc-FLAG and SodB-Met2-FLAG, respectively.

Northern Blotting.

Total RNAs were isolated from cells grown in LB medium to midlog phase as described (27). For Northern blot analysis, indicated amount of total RNAs were resolved by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in the presence of formaldehyde and blotted onto Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences). To prepare RNAs produced in the absence of translation, cells were grown in LB medium and treated with the translation inhibitor kasugamycin as described in the figure legends. The mRNAs were visualized by using digoxigenin (DIG) regents and kits for nonradioactive nucleic acid labeling and detection (Roche Diagnostics) according to the procedures specified by the manufacturer. The following DIG-labeled DNA probes were prepared by PCR using DIG-dUTP: 305-bp fragment corresponding to the 5′ region of ptsG; 500-bp fragment corresponding to the 5′ region and ORF region of sodB; 150-bp fragment corresponding to sgrS; and 120-bp fragment corresponding to ryhB.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Gottesman for critical reading of the manuscript. T.M. thanks Masami Oguchi for continuous encouragement during this work. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan and Ajinomoto Co., Inc. T.M. is a recipient of Research Fellowships of the Japan Society for the Program of Science for Young Scientists.

Abbreviations

- sRNP

small RNA-containing ribonucleoprotein complex

- pgi

phosphoglucose isomerase

- ptsG

glucose-specific transporter of the phosphotransferase system

- αMG

α-methylglucoside

- HA

hemagglutinin

- miRNA

microRNA

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- IP

immunoprecipitation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Gottesman S. Trends Genet. 2005;21:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottesman S. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;58:303–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storz G., Opdyke J. A., Zhang A. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004;7:140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storz G., Altuvia S., Wassarman K. M. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:199–217. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanderpool C. K., Gottesman S. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:1076–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawamoto H., Morita T., Shimizu A., Inada T., Aiba H. Genes Dev. 2005;19:328–338. doi: 10.1101/gad.1270605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masse E., Escorcia F. E., Gottesman S. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2374–2383. doi: 10.1101/gad.1127103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masse E., Gottesman S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:4620–4625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032066599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita T., Maki K., Aiba H. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2176–2186. doi: 10.1101/gad.1330405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen C. In: Control of Messenger RNA Stability. Belasco J. B. G., editor. New York: Academic; 1993. pp. 117–145. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coburn G. A., Mackie G. A. Prog. Nucleic Acids Res. Mol. Biol. 1999;62:55–108. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60505-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morita T., Kawamoto H., Mizota T., Inada T., Aiba H. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:1063–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimata K., Tanaka Y., Inada T., Aiba H. EMBO J. 2001;20:3587–3595. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.13.3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuyama A., Machiyama N., Kinoshita T., Tanaka N. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1971;43:196–199. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(71)80106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Kazzaz W., Morita T., Tagami H., Inada T., Aiba H. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;51:1117–1128. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Udekwu K. I., Darfeuille F., Vogel J., Reimegard J., Holmqvist E., Wagner E. G. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2355–2366. doi: 10.1101/gad.354405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasmussen A. A., Eriksen M., Gilany K., Udesen C., Franch T., Petersen C., Valentin-Hansen P. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;58:1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zamore P. D., Haley B. Science. 2005;309:1519–1524. doi: 10.1126/science.1111444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartel D. P. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sontheimer E. J., Carthew R. W. Cell. 2005;122:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagga S., Bracht J., Hunter S., Massirer K., Holtz J., Eachus R., Pasquinelli A. E. Cell. 2005;122:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim L. P., Lau N. C., Garrett-Engele P., Grimson A., Schelter J. M., Castle J., Bartel D. P., Linsley P. S., Johnson J. M. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morita T., El-Kazzaz W., Tanaka Y., Inada T., Aiba H. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15608–15614. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300177200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wachi M., Umitsuki G., Nagai K. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1997;253:515–519. doi: 10.1007/s004380050352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Datsenko K. A., Wanner B. L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka Y., Kimata K., Aiba H. EMBO J. 2000;19:5344–5352. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aiba H., Adhya S., de Crombrugghe B. J. Biol. Chem. 1981;256:11905–11910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]