Abstract

Chemically defined medium (CDM) conditions for controlling human embryonic stem cell (hESC) fate will not only facilitate the practical application of hESCs in research and therapy but also provide an excellent system for studying the molecular mechanisms underlying self-renewal and differentiation, without the multiple unknown and variable factors associated with feeder cells and serum. Here we report a simple CDM that supports efficient self-renewal of hESCs grown on a Matrigel-coated surface over multiple passages. Expanded hESCs under such conditions maintain expression of multiple hESC-specific markers, retain the characteristic hESC morphology, possess a normal karyotype in vitro, as well as develop teratomas in vivo. Additionally, several growth factors were found to selectively induce monolayer differentiation of hESC cultures toward neural, definitive endoderm/pancreatic and early cardiac muscle cells, respectively, in our CDM conditions. Therefore, this CDM condition provides a basic platform for further characterization of hESC self-renewal and directed differentiation, as well as the development of novel therapies.

Keywords: chemically defined medium

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), typically derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst, can be propagated indefinitely and differentiated into all of the cell types of the embryo proper (1). ESCs not only hold considerable promise for the treatment of a number of devastating diseases but also provide an excellent system for studying early development and human diseases. Human and mouse ESCs are conventionally maintained in culture with feeder cells and/or mixtures of exogenous factors (1, 2, 12). However, unknown factors secreted from the feeder cells or contained in the serum may have undesired activities (e.g., inducing differentiation or cell death), which require the addition of other factors that inhibit their effects. Such undefined culture conditions is the main source of inconsistency in large scale and long-term expansion of undifferentiated ESCs. Consequently, the establishment of a well defined culture condition for ESCs would facilitate practical applications of human ESCs (hESCs) and allow for studying and controlling signaling inputs that regulate self-renewal or differentiation of ESCs without multiple unknown and variable factors.

Recent studies have shown that feeder-fibroblast conditioned medium (CM) (3), high concentrations of basic FGF (bFGF, 100 ng/ml) (4) and combinations of bFGF with Noggin (4, 5) or TGF-β/activin/Nodal signaling molecules (6–8) can support long-term culture of hESCs grown on an extracellular matrix (ECM)-coated surface (e.g., Matrigel) in feeder-free conditions. However, these medium conditions typically contain a proprietary serum replacement product, which is a complex mixture of many unknown factors with varying batch-to-batch activities. To come one step closer to a completely defined, animal product-free condition (i.e., chemically defined media and ECM) for long-term self-renewal and efficient clonal expansion of hESCs, we examined chemically defined medium (CDM) conditions based on the previous studies, which have shown that mESCs can self-renew in the absence of feeder cells in a CDM supplemented with leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) (9), and can be selectively differentiated into different lineages in CDM conditions supplemented with various defined factors (10–12).

Here we report a simple CDM condition that supports long-term self-renewal of two independent hESC lines (H1 and HSF6) grown on a Matrigel-coated surface. The serially passaged hESCs under our CDM conditions maintain expression of multiple hESC-specific markers, retain the characteristic hESC morphology, possess a normal karyotype in vitro, and form complex teratomas after engrafted into nude mice. We also demonstrate the ability of several growth factors to induce selective monolayer differentiation of our CDM expanded hESC cultures toward neural, definitive endoderm/pancreatic and early cardiac muscle cells, respectively, under our CDM conditions. We believe that our CDM conditions provide a basis for further delimiting culture requirements for studying the molecular mechanisms of hESC self-renewal and differentiation.

Results

N2- or N2/B27-Based CDM Supplemented with 20 ng/ml bFGF Is Sufficient for Long-Term Self-Renewal of hESCs.

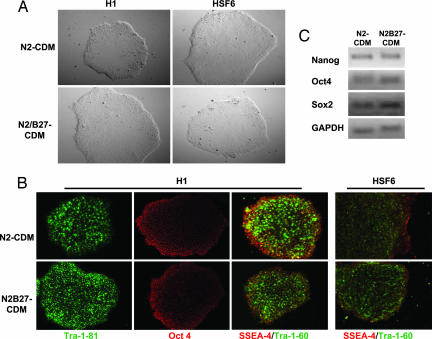

It has been shown recently that the proprietary serum replacement (GIBCO) used widely in hESC culture contains strong BMP-like activity. Antagonizing the BMP pathway with the addition of Noggin (500 ng/ml) along with increased concentration of bFGF (40 ng/ml) allows for the long-term expansion of undifferentiated hESCs on Matrigel in the absence of feeder cells or feeder-cell CM (4, 5). We reasoned that the substitution of the serum replacement with chemically defined components may avoid the use of BMP-antagonizing molecules. To test such hypothesis, we devised a CDM (herein referred as N2-CDM) consisting of DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1× N2 (GIBCO), 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.11 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 0.5 mg/ml BSA (faction V). This N2-CDM was further supplemented with different concentrations of bFGF and evaluated for their ability to support self-renewal of undifferentiated hESCs grown on Matrigel. It was found that the 20 ng/ml bFGF supplemented N2-CDM was sufficient for growing both the H1 and HSF6 hESCs for >17 passages over 5 months. Under such N2-CDM conditions, hESCs grow as large compact colonies (Fig. 1A), similar to undifferentiated hESC colonies grown under CM or feeder cell conditions. N2-CDM expanded hESCs also stain positive for multiple hESC-specific markers including Oct4, Tra-1-60, Tra-1-81, and SSEA-4 (Fig. 1B) but not SSEA-1 (data not shown). They also express high levels of Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 as determined by RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). These results imply that such N2-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF may constitute a minimal medium requirement for supporting self-renewal of hESCs.

Fig. 1.

N2 and N2/B27-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF support long-term self-renewal of hESCs. (A) Serially passaged H1 and HSF6 hESCs grown on a Matrigel-coated surface in 20 ng/ml bFGF-supplemented N2-CDM (Upper) or N2/B27-CDM (Lower) form large compact colonies. (B) H1 and HSF6 hESCs cultured in the above conditions show positive staining of Tra-1-81, Oct4, Tra-1-60, and SSEA-4. (C) RT-PCR analysis shows that the serially passaged H1 hESCs cultured in the above CDM conditions express Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2.

However, hESCs cultured in the above N2-CDM condition grow substantially slower (≈10–12 days per passage) than in normal feeder cell or feeder-free CM conditions (≈6 days per passage). To improve the growth rate, 1× B27 supplements (GIBCO) were added to the N2-CDM (herein referred as N2/B27-CDM). We found that the N2/B27-CDM supplemented with 20 ng/ml bFGF also supported long-term feeder-free culture of both H1 and HSF6 hESCs on Matrigel for >27 passages over a period of 5.5 months. Notably, such N2/B27-CDM conditions support a similar growth rate to conventional hESC cultures grown with feeder cells or in feeder-free CM with comparable if not fewer spontaneously differentiating colonies. Under this N2/B27-CDM condition, hESCs can grow well from very small cell clusters to large compact colonies without visible differentiation (Fig. 1A), characterized by positive staining with Oct4, Tra-1-60, Tra-1-81, and SSEA-4 (Fig. 1B) in addition to high expression levels of Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 as determined by RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). Such N2/B27-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF represents a more practical condition for long-term culture of hESCs due to its ability to efficiently promote self-renewal while maintaining normal hESC growth rates.

The N2/B27-CDM Expanded hESCs Maintain Normal Karyotype and Full Differentiation Potentials.

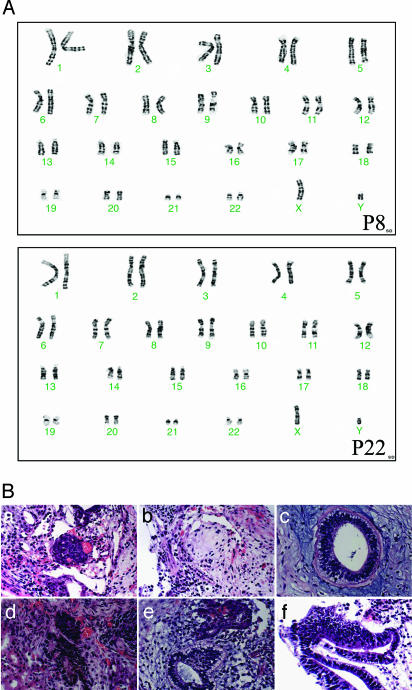

After 7- and 19-week continued feeder-free culture in the N2/B27-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF, H1 hESCs at passage 8 and 22 were karyotyped by standard G-banding. No chromosomal abnormality was found in the analyzed nuclei (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

The N2/B27-CDM expanded hESCs maintain normal karyotype and full differentiation potential. (A) Karyotype analysis of passage 8 and 22 H1-hESCs cultured under the feeder-free condition in the N2/B27-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF using G-banding. A normal karyotype was observed for all analyzed nuclei (two representative examples are shown). (B) Complex differentiation developed in the hESC-derived teratomas 4–5 weeks after inoculation in nude mice. Typical differentiated tissues are shown. a, Glandular acinus-forming epithelium; b, osteoid-forming cells; c, neuroepithelial (ependymal) rosette; d, pigmented retinal epithelium; e, neuroepithelial rosette and glandular-type epithelium; f, columnar epithelium.

To examine the in vitro differentiation potential of the hESCs that had been long-term cultured under the feeder-free condition in the N2/B27-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF, they were treated in monolayer in the N2/B27-CDM with specific growth factors and found to efficiently differentiate into ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm derivatives that will be described in detail below. To further examine their in vivo differentiation potential, passage 7 and 9 H1-hESCs expanded in the N2/B27-CDM plus bFGF were injected under the kidney capsule of nude mice. Teratomas developed in all engrafted mice 4–5 weeks after inoculation and exhibited complex differentiation of the three primary germ layer tissues (Fig. 2B) as determined by histological characterizations. These results confirmed the ability of our described feeder-free culture condition in the N2/B27-CDM plus bFGF to maintain pluripotency of hESCs.

Differentiation of hESCs Under CDM Conditions.

Because the above feeder-free culture in the CDM represents a relatively defined basal condition for self-renewal of hESCs, it also provides an excellent platform for the study of directed hESC differentiation induced by exogenous factors without much complication. We initially examined the effects of Noggin (4, 5), activin A (6, 13), and BMP (4, 14) (which have previously been used for self-renewal and differentiation of hESCs under non-CDM conditions) on hESC differentiation toward neural, definitive endoderm and cardiac muscle lineages. Interestingly, a combinatorial study of these three growth factors alone or in combination at different concentrations revealed conditions for relatively selective differentiation of hESCs, where Noggin induced neural differentiation, activin A induced definitive endoderm/pancreatic differentiation, and activin A plus BMP induced cardiac muscle differentiation.

N2/B27-CDM Plus Noggin Induced Neural Differentiation of hESCs.

The most commonly used methods for inducing neural specification of hESCs involve either growing them in suspension to form embryoid bodies (EBs) and then replating EBs back onto adherent substrate for outgrowth, or coculturing hESCs with particular stromal cells (15–18). However, not only are both methods practically inconvenient (e.g., EB formation and coculture with feeder cells), but they also involve poorly defined medium conditions and processes, and therefore lead to inconsistency. For example, although the stromal cell coculture protocol might be more efficient than the EB protocol in neural induction, the molecular nature of the stromal cell-derived inducing activity (SDIA) remains unknown and the SDIA has midbrain patterning activities (17), making it incompatible with generating unregionalized neural progenitor cells. Consequently, establishment of a monolayer, feeder-free, and CDM condition for neural differentiation of hESCs would be highly desirable.

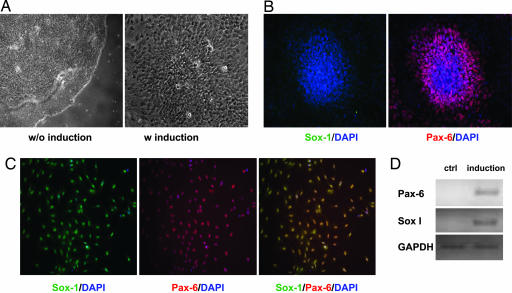

Interestingly, when undifferentiated hESC colonies were treated with Noggin (100 ng/ml) in the N2/B27-CDM in the absence of bFGF, it was observed that, although differentiations from the center of the colonies (which typically occur in the N2/B27-CDM without bFGF) were inhibited and colonies remained compact initially, multiple neural rosette-like structures that started to form from columnar cells were noticeable within each colony after ≈8 days of Noggin treatment (Fig. 3A). Cells within these rosette-like structures immunostain positive for Pax6 but not Sox1 (Fig. 3B), suggesting that they are early neuroectoderm cells. When cells at this stage were trypsinized and replated into single cells in the N2/B27-CDM with bFGF but without Noggin, they became Pax6+/Sox1+ double-positive neural cells (Fig. 3C) that can further differentiate into neurons as evidenced by positive βIII-tubulin and Map2ab stainings as well as characteristic neuronal morphologies. RT-PCR analysis further confirmed the expression of these two neural lineage makers (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that hESCs maintained in the N2/B27-CDM feeder-free condition can differentiate into neural lineage, and Noggin can suppress nonneural differentiations and induce a selective neural specification of hESCs in the N2/B27-CDM.

Fig. 3.

Noggin induced neural differentiation of hESCs cultured in monolayer in the N2/B27-CDM. (A) Four-day-old undifferentiated hESC colonies were treated with 100 ng/ml Noggin for 8 days in the N2/B27-CDM. Noggin blocked the differentiation in the center of the hESC colonies that are typically seen after withdrawal of bFGF but induced formation of multiple neural rosette-like structures over 8 days. (B) Cells within these early rosette-like structures immunostain positive for Pax6 but not Sox1. (C) After the early neural rosettes are split into single cells in the N2/B27-CDM plus bFGF, they further differentiate into Pax6+/Sox1+ double- positive neural cells. (D) RT-PCR analysis confirmed that the late neural cells express both Pax-6 and Sox1.

N2/B27-CDM Plus Activin A Induced Definitive Endoderm/Pancreatic Differentiation of hESCs.

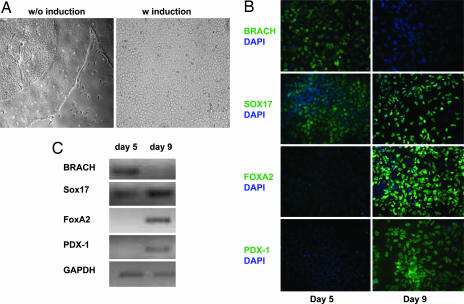

activin A, along with several other TGF-β family members, has been used in combination with bFGF in the serum replacement-containing medium for long-term feeder-free propagation of undifferentiated hESCs (6, 7, 19). Whether activin A or other TGF-β family members is required for self-renewal of hESCs in CDM remains to be determined. Nevertheless, it has also been shown in many studies that activin A can induce differentiation of ESCs toward definitive endoderm lineage (13, 20–22). It was observed that treatment of feeder-free hESC colonies with activin A (100 ng/ml) in the N2/B27-CDM induced dramatic morphological changes of hESCs over 5–9 days (which are different from the trophoblast cell morphology) (Fig. 4A). Immunocytochemical analysis of activin A treated hESCs over 9 days revealed that the differentiating hESCs transition through mesendoderm (Brachyury+) toward definitive endoderm (Brachyury−/Sox17+/HNF3β+). After 5 days of activin A treatment, the number of the differentiating hESCs expressing Brachyury increased to ≈80%, and a fraction of these Brachyury+ cells are also Sox17+. Continued treatment with activin A resulted in a decrease of Brachyury+ cells to <2% and correspondingly an increase in number of Brachyury−/Sox17+/HNF3β+ cells to >80% by day 9 (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the Sox17+/HNF3β+ cells may be differentiated from the Brachyury+ population and represent definitive endoderm cells. In addition, cells that immunostain positive for PDX1 could be observed on day 9 of activin A treated cultures (Fig. 4B), suggesting that such conditions may also permit further pancreatic differentiation. The differential expression of Brachyury, Sox17, HNF3β, and PDX-1 at different time points along activin A treatment could also be confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 4C). These results suggested that hESCs maintained in the N2/B27-CDM and feeder-free conditions can differentiate into definitive endoderm/pancreatic lineages, and activin A acts as a selective inducer for definitive endoderm differentiation of hESCs in the N2/B27-CDM.

Fig. 4.

N2/B27-CDM plus activin A induced definitive endoderm/pancreatic differentiation of hESCs. (A) Four-day-old undifferentiated hESC colonies were treated with 100 ng/ml activin A for 9 days in the N2/B27-CDM. Activin A blocked the differentiation in the center of the hESC colonies that are typically seen after withdrawal of bFGF but induced definitive endoderm differentiation. (B) Immunostaining of hESCs after 5 and 9 days of activin A treatment. At day 5, >80% of the cells express Brachyury, whereas <50% of the cells express Sox17. At day 9, little expression of Brachyury was detected, but Sox17, FOXA2, and PDX-1 were expressed in >80% of the cells. (C) RT-PCR analysis confirmed the expression of Brachyury, Sox17, FOXA2, and PDX-1 at days 5 and 9.

N2/B27-CDM Plus Activin A and BMP Induced Marker Expression Associated with Cardiac Muscle Lineage.

Generating human cardiac muscle cells from hESCs largely relies on a spontaneous EB differentiation process in the presence of serum (23–25). Such method is a poorly defined, inefficient, and relatively nonselective process that leads to heterogeneous populations of differentiated and undifferentiated cells, inappropriate for cell-based therapy or complicated biological studies of particular differentiation programs. Consequently, defining a cardiac muscle differentiation condition for hESCs would facilitate their functional applications in research and therapy, and allow characterization of the molecular mechanisms underlying cardiomyogenic specification.

Feeder-free hESC colonies differentiate quickly toward the trophoblast lineage upon addition of BMP to the N2/B27-CDM. It was found that such trophoblast differentiation can be blocked by activin A, and the treatment of hESCs with the combination of activin A (50 ng/ml) and BMP-4 (50 ng/ml) in the N2/B27-CDM for 3–4 days and continued culture for an additional 8–10 days in the basal N2/B27-CDM induced marker expression associated with cardiac muscle lineage (Fig. 5A). These results are consistent with the model that transient activin A treatment induces mesendoderm differentiation of hESCs in the N2/B27-CDM and BMPs play essential roles in cardiac muscle differentiation. Immunocytochemistry revealed that a high percentage of these differentiated cells were positive for specific cardiomyocyte markers, including MHC, cardiac troponin I (cTnI), MEF-2, and GATA-4 (Fig. 5B). RT-PCR analysis also confirmed the expression of αMHC, cTnI, Nkx-2.5, and ANF in these cells (Fig. 5C). These data suggest that hESCs maintained in the N2/B27-CDM feeder-free condition can proceed through mesendoderm toward mesoderm/cardiac muscle lineage, and the combination of activin A and BMP may represent a selective cardiac muscle induction condition for hESCs in the permissive N2/B27-CDM.

Fig. 5.

N2/B27-CDM plus activin A and BMP induced marker expression associated with cardiac muscle lineage. (A) Four-day-old undifferentiated hESC colonies were treated with 50 ng/ml activin A and 50 ng/ml BMP-4 for 4 days in the N2/B27-CDM and further cultured for an additional 8–10 days in the basal N2/B27-CDM. (B) Immunostaining shows expression of specific cardiomyocyte makers: αMHC, cardiac Troponin I, MEF-2, and GATA-4. (C) RT-PCR shows the expression of αMHC, cardiac Troponin I, Nkx-2.5, and ANF.

Discussion

A Feeder-Free CDM Condition for Long-Term Self-Renewal of hESCs.

The above in vitro and in vivo examinations of the serially passaged hESCs suggest that the use of N2/B27-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF represents a defined, relatively minimal and practical medium condition to support long-term self-renewal of hESCs in the feeder-free fashion. Under such conditions, hESCs maintain the characteristic highly compact colony morphology and multiple hESC-specific markers (Fig. 1). More importantly, such long-term CDM-expanded hESCs maintain normal karyotype, full developmental potential as determined by in vitro directed differentiations toward the three primary germ layer derivatives (Figs. 3–5), and in vivo complex teratoma formation (Fig. 2). Moreover, such conditions have been applied in large-scale serial cultures of undifferentiated hESCs (>108), and provide opportunities for various applications, including genomic, proteomic, and high throughput screening studies, which had been compromised in the past by previous undefined, complex serum-containing medium conditions. However, it should be noted that additional efforts are needed to further improve the culture condition for efficient clonal expansion, define the optimal ECM (e.g., Matrigel is not chemically defined), and make the culture condition completely animal product free.

Multiple signaling pathways have been suggested for the maintenance of hESC pluripotency. However, almost all of these studies (e.g., hESC derivations, expression analysis, and cellular assays) were carried out under the influences of feeder cells and/or serum, and consequently their results reflect/inherit the nature of such complex and undefined environments. For example, although hESCs remain pluripotent in culture with certain feeder-derived factors counteracting the differentiation inducing activity in the serum replacement, their properties (e.g., ECM or clonal expansion requirements, differentiation propensity) and molecular profiles are also adapted to those factors from feeder cells and serum. Therefore, it is conceivable that new hESC lines with more comparable properties with mESC lines can be derived under new conditions.

Our CDM condition described here is largely consistent with the evidence emerging from the recent reports on the developments of unconditioned media and CDM: inhibiting differentiation of proliferating ESCs would be sufficient for their self-renewal. In most of the commonly used hESC culture conditions, BMP-like activity contained in the media is the dominating differentiation-inducing factor (4, 14). Consequently, reducing such BMP-like activity by using a CDM with supplemented bFGF that directly or indirectly inhibits the remaining differentiation-inducing activity and promotes proliferation allows expansion of the undifferentiated hESCs (4). Concurrent with our work, an RPMI-based CDM condition, which requires bFGF and activin/Nodal as well as the use of FBS-derived ECM and possibly a 10-fold higher concentration of BSA, was reported by Vallier et al. (19) for supporting long-term self-renewal of hESCs. Their studies concluded that the use of bFGF as the only growth factor supplement in the medium was not sufficient to support long-term self-renewal of hESCs in their CDM but that activin/Nodal is required in addition to bFGF. This discrepancy may be explained by the following possibilities: (i) our use of 20 ng/ml bFGF (vs. 12 ng/ml in Vallier’s CDM) because growth factor activity is often concentration-dependent; (ii) our use of Matrigel as ECM that has been shown to contain TGF-β (26, 27), which, however, could not substitute activin/Nodal for supporting hESC self-renewal in Vallier’s CDM; on the other hand, FBS-derived ECM may contain other undefined factors as well; and (iii) certain components in the N2 and B27 supplements may provide activin/Nodal-like activity. Interestingly, when our N2/B27-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF was further supplied with 100 ng/ml Nodal or 20 ng/ml activin A for hESC culture, differentiation occurs within 3 days (data not shown). More recently, Ludwig et al. (28) reported a DMEM/F12-based CDM (named TeSR1) that contains bFGF (≈100 ng/ml), TGF-β (≈0.6 ng/ml), LiCl (≈1 mM), GABA, and pipecolic acid for long-term self-renewal and derivation of hESCs. Although additional experiments would be required to more carefully compare these CDM conditions and their utilities, our N2/B27-CDM provides a basic platform for further development of more efficient and defined culture conditions for hESCs, as well as characterization of hESC self-renewal and directed differentiation.

Monolayer Culture of hESCs in the N2/B27-CDM Provides a Defined Platform for Directed Differentiation Studies.

Controlled differentiation of hESCs into a homogenous population of a specific cell type is required for their ultimate application in cell-based therapy. However, most differentiation protocols involve EB formation and the use of serum, which are undefined and nonselective. Starting from monolayer hESC colonies, our differentiation protocols using the N2/B27-CDM with the appropriate growth factors allow for the selective induction of hESCs toward neural (Fig. 3), definitive endoderm/pancreatic (Fig. 4), and early cardiac muscle lineages (Fig. 5). Although Noggin, activin A, and BMP have been shown with different activities for self-renewal or differentiation, these discrepancies may largely be explained by their dosage effect and the existence of other factors in the media. Similar conditions (with differences in the basal media and the use of low concentration of serum) and models for selective neural, definitive endoderm, and mesoderm differentiations have also been recently reported by others, supporting our findings (13, 29).

In summary, we have described a basal CDM that can be devised for either long-term self-renewal or selective differentiation of hESCs. Such conditions provide a basic platform for further characterizing hESC self-renewal and differentiation using genomic, proteomic, and functional high-throughput screening approaches, and may ultimately lead to the development of novel therapies.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture.

H1 and HSF6 hESCs are routinely cultured on irradiated CF-1 MEF feeder cells in DMEM/F-12 supplied with 20% KnockOut Serum Replacement (GIBCO), 2 mM l-glutamine, 1.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 8 ng/ml bFGF. Cells are passaged at the ratio of 1 to ≈6–10 every 4–5 days by using 1 mg/ml collagenase type IV. For feeder-free culture, hESCs are grown on Matrigel-coated tissue culture plates in either the N2- or N2/B27-CDM and passaged by using 1 mg/ml Dispase (GIBCO). The N2-CDM is defined as DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 1× N2 supplements, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.11 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, and 0.5 mg/ml BSA (fraction V). The N2/B27-CDM is defined as the N2-CDM plus 1× B27 supplements. The N2 supplements (GIBCO) contain 1 mM human transferrin (Holo), 8.61 μM recombinant human insulin, 1 mM progesterone, 1 mM putrescine, and 1 mM selenite. The B27 supplements (GIBCO) contain d-biotin, BSA (fatty acid-free, fraction V), catalase, l-carnitine HCl, corticosterone, ethanolamine HCl, d-galactose (anhydrous), glutathione (reduced), insulin (human, recombinant), linoleic acid, linolenic acid, progesterone, putrescine·2HCl, sodium selenite, superoxide dismutase, T-3/albumin complex, dl-α-tocopherol, dl-α-tocopherol acetate, and transferrin (human, iron-poor) (information provided by GIBCO).

Immunostaining.

Undifferentiated or induced differentiated hESCs were fixed and immunostained by standard indirect immunocytochemistry. The following commercial antibodies were used: anti-Tra-1-60 (Chemicon) at 1:100, anti-Tra-1-81 (Chemicon) at 1:100, anti-SSEA4 (Chemicon) at 1:100, anti-Oct4 (Chemicon) at 1:100, anti-SSEA1 (Chemicon) at 1:100, anti-human Sox17 goat antibody (R & D Systems) at 1:100, anti-human HNF-3β/FOXA2 goat antibody (R & D Systems) at 1:100, anti-human Brachyury goat antibody (R & D Systems) at 1:100, anti-human PDX-1/IPF1 goat antibody (R & D Systems) at 1:100, anti-αMHC (MF-20; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) at 1:400, anti-cardiac Troponin I McAb (clone 8I-7; Spectral Diagnostics) at 1:200, anti-human MEF-2 rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:100, anti-human GATA-4 rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:100, anti-human Sox1 goat antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:100, and anti-Pax6 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) at 1:200. The following secondary antibodies are used: Cy2-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgM, μ-chain-specific (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at 1:200, Cy3-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG, Fcγ fragment-specific (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at 1:500, Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG(H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at 1:200, Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG(H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at 1:200, and Cy2-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at 1:400.

RT-PCR.

Cells were harvested by using Trypsin. After PBS washing, mRNA were isolated by using an RNeasy Miniprep kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed by using an Invitrogen SuperScript First-strand Synthesis System kit. The following primer pairs were used to detect the gene-specific mRNAs: human Oct4, 5′-GAGCAAAACCCGGAGGAGT-3′ and 5′-TTCTCTTTCGGGCCTGCAC-3′; human Nanog, 5′-GCTTGCCTTGCTTTGAAGCA-3′ and 5′-TTCTTGACTGGGACCTTGTC-3′; human Sox2, 5′-ATGCACCGCTACGACGTGA-3′ and 5′-CTTTTGCACCCCTCCCCATT-3′; human Pax6, 5′-TCAGGCTTCGCTAATGGG-3′ and 5′-AAAAGGCCTCACACATCTG-3′; human PDX-1, 5′-CATGAACGGCGAGGAGCAGTA-3′ and 5′-GTTGAAGCCCCTCAGCCAGG-3′; human Sox-1, 5′-ATGCACCGCTACGACATGG-3′ and 5′-CTCATGTAGCCCTGCGAGTTG-3′; human αMHC, 5′-GGAGGAGCAAGCCAACACCAA-3′ and 5′-GCAGTGAGGTTCCCGTGGCA-3′; human cardiac Troponin-I (cTnI), 5′-CCCTGCACCAGCCCCAATCAGA-3′ and 5′-CGAAGCCCAGCCCGGTCAACT-3′; human Nkx-2.5, 5′-TGGCTACAGCTGCACTGCCG-3′ and 5′-GGATCCATGCAGCGTGGAC-3′; human ANF, 5′-TAGGGACAGACTGCAAGAGG-3′ and 5′-CGAGGAAGTCACCATCAAACCAC-3′; human Brachyury, 5′-TGCTTCCCTGAGACCCAGTT-3′ and 5′-GATCACTTCTTTCCTTTGCATCAAG-3′; human Sox17, 5′-GGCGCAGCAGAATCCAGA-3′ and 5′-CCACGACTTGCCCAGCAT-3′; human FoxA2, 5′-GGGAGCGGTGAAGATGGA-3′ and 5′-TCATGTTGCTCACGGAGGAGTA-3′; human GAPDH, 5′-AGCCACATCGCTCAGACACC-3′ and 5′-GTACTCAGCGGCCAGCATCG-3′. The PCR was performed under the following conditions: 3 min at 94°C, and then 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 10 min 72°C extension after the cycles.

Teratoma Formation and Karyotyping.

The serially passaged H1 hESCs (passage 7 and 9) under the feeder-free condition in the N2/B27-CDM plus bFGF were harvested by using 1 mg/ml Dispase. Three to five million cells were injected under the kidney capsule of nude mice. Two mice were injected with the passage 7 hESCs, and five mice were injected with the passage 9 hESCs. After 4–5 weeks, all mice developed teratomas, which were removed and then immunohistologically analyzed by The Scripps Research Institute Research Histology service and Animal Resources. The passage 8 and 22 H1 hESCs cultured under the feeder-free N2/B27-CDM condition were karyotyped by standard G-banding at the University of California at San Diego, Medical Genetics Laboratory. No chromosomal abnormality was found in the 10 randomly picked nuclei.

In Vitro-Induced Differentiation.

Four-day-old undifferentiated hESC colonies cultured under the feeder-free N2/B27-CDM plus 20 ng/ml bFGF conditions were treated with corresponding cytokines to induce differentiation. For neural differentiation, 100 ng/ml recombinant mouse Noggin (R & D Systems) was added into the N2/B27-CDM in the absence of bFGF. After 8 days of induction, multiple neural rosette-like structures were observed within each colony. For definitive endoderm differentiation, 100 ng/ml recombinant human/mouse/rat activin A (R & D Systems) was added into the N2/B27-CDM in the absence of bFGF. The cells were analyzed on days 5 and 9. For cardiomyocyte differentiation, cells were treated with 50 ng/ml recombinant human BMP-4 (R & D Systems) and 50 ng/ml recombinant human/mouse/rat activin A in the N2/B27-CDM for 3–4 days and cultured in the cytokine-free media for an additional 8–10 days.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kent Osborn for histological analysis of teratomas. This work was supported by grants from The Scripps Research Institute (to S.D.) and The Larry L. Hillblom Foundation (A.H.).

Abbreviations

- ESC

embryonic stem cell

- hESC

human ESC

- CM

conditioned medium

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- CDM

chemically defined medium

- BMP

bone morphogenetic protein

- EB

embryoid body

- bFGF

basic FGF

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Thomson J. A., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Shapiro S. S., Waknitz M. A., Swiergiel J. J., Marshall V. S., Jones J. M. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reubinoff B. E., Pera M. F., Fong C. Y., Trounson A., Bongso A. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:399–404. doi: 10.1038/74447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu C., Inokuma M. S., Denham J., Golds K., Kundu P., Gold J. D., Carpenter M. K. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:971–974. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu R. H., Peck R. M., Li D. S., Feng X., Ludwig T., Thomson J. A. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:185–190. doi: 10.1038/nmeth744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang G., Zhang H., Zhao Y., Li J., Cai J., Wang P., Meng S., Feng J., Miao C., Ding M., et al. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;330:934–942. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beattie G. M., Lopez A. D., Bucay N., Hinton A., Firpo M. T., King C. C., Hayek A. Stem Cells. 2005;23:489–495. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James D., Levine A. J., Besser D., Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 2005;132:1273–1282. doi: 10.1242/dev.01706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallier L., Reynolds D., Pedersen R. A. Dev. Biol. 2004;275:403–421. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ying Q. L., Nichols J., Chambers I., Smith A. Cell. 2003;115:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ying Q. L., Stavridis M., Griffiths D., Li M., Smith A. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:183–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiles M. V., Johansson B. M. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;247:241–248. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller G. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1129–1155. doi: 10.1101/gad.1303605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Amour K. A., Agulnick A. D., Eliazer S., Kelly O. G., Kroon E., Baetge E. E. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:1534–1541. doi: 10.1038/nbt1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu R. H., Chen X., Li D. S., Li R., Addicks G. C., Glennon C., Zwaka T. P., Thomson J. A. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:1261–1264. doi: 10.1038/nbt761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S. C., Wernig M., Duncan I. D., Brustle O., Thomson J. A. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carpenter M. K., Inokuma M. S., Denham J., Mujtaba T., Chiu C. P., Rao M. S. Exp. Neurol. 2001;172:383–397. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrier A. L., Tabar V., Barberi T., Rubio M. E., Bruses J., Topf N., Harrison N. L., Studer L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:12543–12548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizuseki K., Sakamoto T., Watanabe K., Muguruma K., Ikeya M., Nishiyama A., Arakawa A., Suemori H., Nakatsuji N., Kawasaki H., et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:5828–5833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1037282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vallier L., Alexander M., Pedersen R. A. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:4495–4509. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ku H. T., Zhang N., Kubo A., O’Connor R., Mao M., Keller G., Bromberg J. S. Stem. Cells. 2004;22:1205–1217. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo A., Shinozaki K., Shannon J. M., Kouskoff V., Kennedy M., Woo S., Fehling H. J., Keller G. Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 2004;131:1651–1662. doi: 10.1242/dev.01044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tada S., Era T., Furusawa C., Sakurai H., Nishikawa S., Kinoshita M., Nakao K., Chiba T., Nishikawa S. Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 2005;132:4363–4374. doi: 10.1242/dev.02005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He J. Q., Ma Y., Lee Y., Thomson J. A., Kamp T. J. Circ. Res. 2003;93:32–39. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000080317.92718.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kehat I., Kenyagin-Karsenti D., Snir M., Segev H., Amit M., Gepstein A., Livne E., Binah O., Itskovitz-Eldor J., Gepstein L. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:407–414. doi: 10.1172/JCI12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu C., Police S., Rao N., Carpenter M. K. Circ. Res. 2002;91:501–508. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000035254.80718.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinman H. K., McGarvey M. L., Liotta L. A., Robey P. G., Tryggvason K., Martin G. R. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6188–6193. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vukicevic S., Kleinman H. K., Luyten F. P., Roberts A. B., Roche N. S., Reddi A. H. Exp. Cell Res. 1992;202:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90397-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ludwig T. E., Levenstein M. E., Jones J. M., Berggren W. T., Mitchen E. R., Frane J. L., Crandall L. J., Daigh C. A., Conard K. R., Piekarczyk M. S., et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:185–187. doi: 10.1038/nbt1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerrard L., Rodgers L., Cui W. Stem Cells. 2005;23:1234–1241. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]