Abstract

To explore scenarios that permit transcription regulation by activator recruitment of RNA polymerase and σ competition in vivo, we used an equilibrium model of RNA polymerase binding to DNA constrained by the values of total RNA polymerase (E) and σ70 per cell measured in this work. Our numbers of E and σ70 per cell, which are consistent with most of the primary data in the literature, suggest that in vivo (i) only a minor fraction of RNA polymerase (<20%) is involved in elongation and (ii) σ70 is in excess of total E. Modeling the partitioning of RNA polymerase between promoters, nonspecific DNA binding sites, and the cytoplasm suggested that even weak promoters will be saturated with Eσ70 in vivo unless nonspecific DNA binding by Eσ70 is rather significant. In addition, the model predicted that σs compete for binding to E only when their total number exceeds the total amount of RNA polymerase (excluding that involved in elongation) and that weak promoters will be preferentially subjected to σ competition.

Keywords: nonspecific DNA binding, gene regulation promoter, systems biology, Escherichia coli

In bacteria transcription is initiated by RNA polymerase (RNAP) holoenzyme (Eσ), which is formed when core RNAP (E) binds the transcription initiation factor σ (1). Eσ initially binds to promoter sites in a closed complex, which then transits to an open complex, competent for transcription. The number of intermediates between the closed and open complex is variable and promoter-dependent; each step may be subject to regulation in vivo (2, 3). At least for some promoters, Eσ binding to promoters is thought to be reversible on the time scale of transcription initiation in vivo (3); reversibility has also been demonstrated in vitro for several promoters (3–6). Even binding to the strong lac UV5 promoter is reversible in vitro when tested under conditions that approximate the in vivo situation (6).

Recruitment of Eσ to promoters in vivo is thought to depend on the intrinsic binding affinity of the promoter and is modulated by repressors that prevent and activators that stabilize interactions between Eσ and the promoter (3). Based on in vitro studies of the mechanism of activator function, it is believed that promoters that bind Eσ weakly require activators to recruit Eσ. In addition, cells contain multiple σs, which direct E to various sets of promoters specific to the σ factors (1). These σs are believed to compete with each other for binding to E (7–10). By changing the relative levels of the σs, Escherichia coli is thought to coordinate its transcriptional program with growth conditions (11–13). This view is based on observations indicating that (i) overexpressing one σ decreases expression of genes controlled by another σ (7), (ii) mutationally altering binding constants of one σ for E alters expression by another σ (14), and (iii) physiological effectors such as ppGpp may act by altering relative binding of σs to E (8–10). In the present work, we use an equilibrium model of RNAP binding to DNA to explore in vivo scenarios that permit transcription regulation by activator recruitment of RNAP and σ competition.

Nonspecific binding of E and Eσ to DNA should be an important component of a model that describes RNAP binding to promoters. Nonspecific binding of both species has been demonstrated in vitro (15); however, the magnitude and extent of nonspecific binding in vivo are hard to evaluate experimentally. von Hippel et al. (16) were the first to develop a model that examined the role of nonspecific binding in regulating transcription. Using a simple equilibrium approach, they examined partitioning of the Lac repressor between specific and nonspecific sites in E. coli. Their results showed that the kinetics of induction of Lac repressor could be understood only when nonspecific DNA binding was considered, suggesting that nonspecific DNA binding may play an important role in the thermodynamics and kinetics of interaction of transcription factors (as well as RNAP) with their specific sites (16, 17).

Estimation of RNAP partitioning between promoters, nonspecific binding sites on DNA, and the cytoplasm requires knowledge of the levels of E, σ70 (the housekeeping σ factor), and at least some alternative σs. However, published values have been measured by different techniques, in different strains, and under different physiological conditions (both during exponential phase and during entry into stationary phase) (18–26). In fact, discrepancies in these numbers have led to the common perceptions that (i) as most RNAP is elongating, only a minor fraction could be bound to DNA nonspecifically (27, 28), and (ii) cellular levels of σ70 are much less than that of RNAP (29); thus, σs may compete because of their excess over free RNAP. We have remeasured the levels of E, σ70, σ32, and σE in E. coli K12 MG1655. Analysis of our data, which are consistent with most of the primary data in the literature, suggests that in vivo (i) only a minor fraction of RNAP (<20%) is involved in elongation and (ii) σ70 is in excess of total E.

Using an equilibrium model based on our new values and relevant data from the literature, we explored the possible partitioning of E and Eσ between promoters, nonspecific DNA sites, and the cytoplasm. Our results suggest that even weak promoters will be saturated with Eσ70 in vivo unless nonspecific DNA binding by Eσ70 is rather significant. Thus, strong nonspecific binding is required for activators to work by recruiting Eσ and for the binding affinity of the promoter to contribute to regulation. In addition, our model predicts that σs compete for binding to E only when their total number exceeds the total amount of RNAP (excluding those molecules involved in elongation), rather than the amount of free RNAP, and that weak promoters will be preferentially subjected to σ competition.

Results and Discussion

Quantifying Intracellular Levels of σE, σ32, σ70, and E.

Our data for the levels of σ70, σE, σ32, and E in cells growing exponentially in M9 glucose (M9 minimal) and M9 glucose supplemented with amino acids (M9 complete) are summarized in Table 1. Determinations of cell number and total protein mass per cell, taken at the same OD450 as sampling for intracellular protein concentrations (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), were used to convert our measurements to molecules per cell and fmol/μg total cellular protein (Table 1).

Table 1.

E, σ70, σE, and σ32 intracellular levels during log phase in MG1655 wild-type cells, grown in M9 glucose media at 30°C

| Complete media |

Minimal media |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fmol/μg total protein* | No. of molecules per cell† × 103 | fmol/μg total protein* | No. of molecules per cell† × 103 | |

| E‡ | 46 ± 15 | 13 ± 4 | 14 ± 7 | 2.6 ± 1.3 |

| σ70 | 62 ± 17 | 17 ± 4 | 26 ± 13 | 4.7 ± 2.4 |

| σE | 20 ± 5 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 17 ± 4 | 3.2 ± 0.6 |

| σ32 | 0.44 ± 0.14 | 0.120 ± 0.034 | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 0.020 ± 0.005 |

These values are based on measurements from three independent cultures.

*Calculated by dividing moles of the measured protein per milliliter of culture by the total protein per milliliter of culture (see Table 2).

†Converted into the no. of molecules per cell by multiplying moles of protein in 1 ml of culture by Avogadro’s number and dividing that value by the no. of cells per 1 ml of culture (see Table 2).

‡The concentration of purified E, used for quantification, was measured by UV A280 absorbance, whereas the concentration of the three purified σ factors, used for quantification, was measured by Coomassie staining, as described in Materials and Methods.

Our estimate of ≈13,000 molecules of E per cell (≈5,000 per genome equivalent) for M9 complete is somewhat higher than the value of 5,000 molecules per cell (2,000 molecules per genome equivalent) quoted in most reviews (23, 29), but it is consistent with the fraction of total protein synthesis devoted to E, αp, that has been reported previously (αp; Table 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). Despite strain differences (Table 3: E. coli B, entries 1–4, vs. E. coli K12, entries 5–8), sample preparation differences (Table 3: whole-cell lysates, entries 1–5, vs. pelleted lysates, entries 6–8), and quantification differences (Table 3: radioactivity, entries 2–4 and 6–8, vs. densitometry, entries 1 and 5), αp values for cells growing in glucose plus amino acids are 1.1–1.8%, with most values clustering between 1.5% and 1.7% (Table 3, entries 1–8). Thus, our αp value of 1.8 ± 0.6% (entry 5) is within the range of reported values, and 13,000 molecules of E per cell is a reasonable estimate to use.

Our estimate that σ70 is ≈60 fmol/μg total protein in M9 complete (Table 1) is similar to reports that there are 50–170 fmol σ70 per microgram total protein values for cells growing in LB (18, 20, 29). These estimates of σ70 are higher than those obtained previously using less direct methods (23, 30, 31), probably because of protein loss during the experimental procedures. To convert to number of molecules per cell, the fmol σ70 per microgram total protein was multiplied by the amount of total protein per cell (Table 2) and Avogadro’s number. Thus, 60 fmol σ70 per microgram total protein corresponds to 17,000 molecules per cell or ≈7,000 molecules per genome (Table 1 and Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). This is almost an order of magnitude higher than the generally reported number of 500–1,700 σ70 molecules either per cell or per genome equivalent (18, 20, 29). However, because the fmol σ70 per microgram total protein used to calculate σ70 molecules per cell are all in the same range, the inconsistency appears simply to be a result of miscalculation. Thus, all recent data are consistent with a significantly higher number of σ70 molecules per cell than previously thought.

σE is much more abundant (3,000–5,500 molecules per cell) than the previously reported value of <100 molecules per cell (18). This profound difference is not a media effect or an effect of preparation methods (data not shown). Our measurements indicate that total σE represents a significant fraction of the σ molecules in a cell, almost comparable in abundance to σ70.

Our data reveal two new aspects of global regulation. First, our E αp = 0.5% measured in glucose (Table 3, entry 5) is lower than previously measured αp values in glucose (Table 3, αp = 1–1.4%, entries 3, 4, 7, 8). Because E expression varies with growth rate (21, 23, 24), the discrepancy in αp values may be due to a much slower doubling time of MG1655 (133 min), a partial purine auxotroph (32), than the other strains (40–79 min). Second, slower-growing cells have a 1.4-fold increase in the ratio of σ70 to E (Tables 1 and 4), which might alter σ competition. A more comprehensive examination of the ratios of these molecules as a function of a wide range of growth rates is required to establish the generality of these observations.

Insights on Partitioning of RNAP from the Equilibrium Model Using Measured Values of E and σ70.

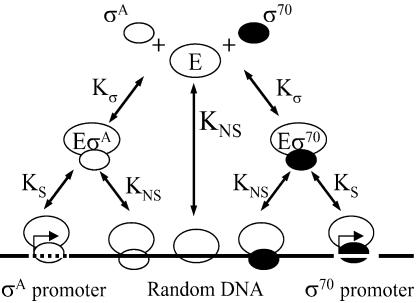

To calculate partitioning of RNAP between specific (promoters) and nonspecific sites on DNA and a pool of free RNAP in the cytoplasm we developed an equilibrium model that is described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1) and in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Preliminary calculations indicated that the dissociation constants for specific (KS) and nonspecific (KNS) binding of RNAP (E + Eσ70) to DNA are the critical parameters that influence partitioning of RNAP between specific and nonspecific sites on DNA. In vitro measurements indicate that these constants are very sensitive to ionic conditions and vary from 10−6 to 10−9 M for KS (for initial closed complex formation) and from 10−3 to 10−6 M for KNS (2, 15). Neither the precise intracellular ionic conditions nor the distribution of promoter binding strengths are known in vivo. Therefore, to gain insight on the possible partitioning of RNAP in vivo, we varied KS and KNS over a wide range of values and modeled the outcome.

Fig. 1.

Equilibrium model reaction channels. E can bind to either of two σ factors, σ70 and σA, to form Eσ70 or EσA, each having the same disassociation constant Kσ. Eσ70 can specifically bind to σ70 promoters, whereas EσA can specifically bind to σA promoters with the same disassociation constant KS. E, Eσ70, and EσA can bind to DNA nonspecifically with a disassociation constant KNS.

We first determined how varying KS and KNS would affect the amount of free cytoplasmic RNAP (E and Eσ70), because this parameter has been determined experimentally to be ≤1% of total RNAP (33). Free cytoplasmic RNAP was measured by examining how the β′-subunit of RNAP partitions into minicells (which lack DNA) (33). Our model predicts that, for KS and KNS within their reported range in vitro (2, 15), the majority of RNAP will be bound to DNA and very little RNAP will be free in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). Thus, for reasonable values of KS and KNS, the equilibrium model recapitulates experimental results.

Fig. 2.

Free RNAP and promoter saturation vs. KS and KNS. Data were calculated according to the equilibrium model. See Materials and Methods and Supporting Text for a complete discussion of the binding constants and approximations used in the models. The number of total σA = 0; ET = 12,000 molecules per cell (the number of total RNAP that is not involved in elongation); total σ70 = 17,000 molecules per cell; σ70 promoters = 10,500; DNA binding sites = 11 × 106 (see Table 4, column 3). (A) Free RNAP as a function of KS and KNS. Solid lines are sets of KS (the dissociation constant for Eσ70 binding to promoters) and KNS (the dissociation constant of nonspecific binding between E or Eσ70 and the random DNA) for which free RNAP (free E plus free Eσ70) is 5%, 1%, or 0.1% of ET. Hatched area is the space of KS and KNS where free RNAP is <1%. The dashed line indicates where KS = KNS; everything to the right of this line is considered nonphysiological. (B) Fraction of σ70 promoters occupied by Eσ70 plotted vs. KS as a function of KNS.

We then calculated how varying KS and KNS affects the fraction of σ70 promoters occupied by Eσ70 (Fig. 2B). When nonspecific binding is weak (KNS ≥ 10−2 to 10−3 M), Eσ70 promoters are predicted to be fairly close to saturation (Fig. 2B). This is true even for promoters that bind Eσ70 very weakly (KS ≈ 10−6 M); such promoters are usually thought to fire only in the presence of an activator. On the other hand, if nonspecific binding is relatively strong (KNS ≈ 10−4 to 10−6 M), then Eσ70 promoters with KS >10−9 M are predicted to be far from saturation (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that nonspecific binding of RNAP is a critical determinant of promoter occupancy by Eσ70. Thus, activators can function by recruiting RNAP and binding affinity can contribute to promoter strength only if KNS is tight enough in vivo to prevent complete promoter occupancy by Eσ70.

The above results were obtained by assuming an equivalent KNS for both E and Eσ70. However, KNS of E and Eσ70 may not be equivalent. We therefore tested whether promoter occupancy by Eσ70 is sensitive to KNS of E. Because E binds much more tightly to σ70 (Kσ ≈ 1 nM) than to nonspecific DNA (KNS ≈ 10−2 to 10−6 M), any free E preferentially binds to σ70 rather than to DNA. Thus, Eσ70, not E, is the predominant species binding nonspecifically to DNA. As a consequence, KNS of E can be varied over three orders of magnitude relative to KNS of Eσ70 without affecting promoter saturation with Eσ70 (data not shown). The model is sensitive to KNS of E only if the binding constant of E to σ70 is very weak (Kσ ≫ 10−6 M; data not shown). These results indicate that KNS of E has no significant influence on promoter occupancy by Eσ70. Therefore, we propose that the extent of promoter saturation in vivo is determined primarily by KNS and KS of Eσ70.

The discussion thus far has been limited to those promoters exhibiting reversible binding to RNAP. When Eσ–promoter binding is irreversible on the time scale of transcription initiation, their occupancy is determined by the rate of Eσ association with the promoter and the rate of transcription initiation, limited by promoter clearance (≈1 sec−1). To keep such promoters unsaturated in the absence of nonspecific binding of Eσ to DNA, their association rate constant would have to be very slow, on the order of 10−4 M−1 sec−1 or less (data not shown). We therefore suggest that, to stay far from saturation, such promoters also require a low pool of free Eσ, attained through its nonspecific binding to DNA.

Insights from the Equilibrium Model on σ Competition.

We used our equilibrium model to examine how competition between σ70 and σA, both assumed to have equal affinity for E, depends on the following three parameters: (i) the total number of σs (σt = σ70 + σA), (ii) promoter saturation by Eσ70 (in the absence of σA), and (iii) the amount of free RNAP (both E and Eσ70).

We determined whether competition between σs depends on the absolute number of σs by varying the number of σA per cell at different numbers of σ70 per cell. When σs compete, an increase in σA per cell decreases promoter occupancy by Eσ70 (Fig. 3A). Simulations showed that competition occurs only when total σs exceeds the total number of E (compare solid and dashed lines in Fig. 3A). This result reflects the fact that σA first titrates nonspecifically bound E to form holoenzyme (EσA) and only then competes with σ70 for E. Additional simulations of the model indicate that total σ must be in excess over E regardless of variations in the number of free RNAP or the number of promoters saturated with Eσ70 at σA = 0 (data not shown). It is noteworthy that σA competes more weakly than an equivalent amount of σ70 (Fig. 3A, “perfect competition” line). This asymmetry is due to our assumption that Eσ70 binds a large number of promoters, whereas EσA has few promoter sites. We therefore ignored specific binding of EσA. As a result, equilibrium is slightly shifted so that E preferentially binds σ70 over σA (but see Figs. 4 and 5, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 3.

Decrease in Eσ70 promoter occupancy induced by σ competition. Calculated according to the equilibrium model. See Materials and Methods and Supporting Text for a complete discussion of the binding constants and approximations used in the model. ET, the number of RNAP not included in elongation = 12,000 molecules per cell; σ70 promoters = 10,500; DNA binding sites = 11 × 106 (see Table 4, column 3). The concentration of free RNAP = free E + free Eσ70 is set at 1%. (A) Decrease in Eσ70 promoter occupancy calculated for various numbers of σ70 molecules per cell. Eσ70 promoter occupancy at σA = 0 is 48%. Dashed line: σ70 = 8,000 molecules per cell (KS = 1.19 × 10−7 M, KNS = 4.01 × 10−4 M). Competition starts when σT = σ70 +σA > ET = 12,000 molecules. Solid line: σ70 = 17,000 molecules per cell (KS = 2.76 × 10−7 M, KNS = 4.01 × 10−4 M). An arbitrary line of perfect competition is calculated for σ70 = 17,000 molecules per cell for a “symmetrical” case when EσA has the same number of specific binding sites and the same KS as Eσ70. (B) Decrease in Eσ70 promoter occupancy calculated for promoters with various binding affinities to Eσ70. σ70 is set at 17,000 molecules per cell. The occupancy of σ70 promoters with Eσ70 (at σA = 0) is set at 99% for “strong” promoters (KS = 2.07 × 10−9 M, KNS = 1.88 × 10−3 M), 48% for “intermediate” promoters (KS = 2.76 × 10−7 M, KNS = 4.01 × 10−4 M), and 5% for “weak” promoters (KS = 5.01 × 10−6 M, KNS = 2.42 × 10−4 M).

That the total number of σs must be higher than the number of nonelongating E for σ competition in vivo rationalizes the higher number of σ70 per cell estimated in this work (Table 1). In this regard, it is interesting that, at low growth rates, the ratio of σ70/E is greater than at high growth rates (Tables 1 and 4). Thus, the competition among σs may be more prevalent at low than high growth rates.

We next explored whether extent of promoter occupancy affects competition between σs. In these simulations, we (i) fixed σ70t > Et, (ii) fixed the concentration of free RNAP to 1% (33), and (iii) varied KS and KNS to achieve initial Eσ70 promoter occupancies (at σA = 0) of 99%, 48%, or 5%. Calculation of σA competition for each initial condition indicates that an increase in σA always results in a decrease in Eσ70 promoter occupancy (Fig. 3B). However, the extent of competition depends inversely on the promoter saturation: promoters close to saturation are weakly competed, whereas promoters far from saturation show profound competition (Fig. 3B). These results can be understood by considering how the ability of σA to pull Eσ70 from its promoters is affected by the assumed KS and KNS of Eσ70. High promoter saturation by Eσ70 requires strong affinity for promoters (KS ≪ KNS; see Fig. 2 A and B). In this condition, σA primarily pulls Eσ70 from its nonspecific interactions with DNA, leading to a very small decrease in the occupancy of strong promoters. In contrast, low promoter saturation is achieved when KS is weak (KS ≈ KNS). Here σA competes with promoter-bound Eσ70 almost as readily as with nonspecifically bound Eσ70, accounting for the profound competition observed.

Further simulations indicated that when initial promoter occupancy (σA = 0) was fixed altering the free RNAP concentration (5%, 1%, or 0.1%) did not affect competition-induced changes in promoter occupancy (data not shown). Therefore, even if <1% of RNAP is free in vivo, we predict that the relationship between σ competition-induced changes in promoter saturation and promoter binding strengths (Fig. 3B) would not be altered. We therefore propose that only promoters far from saturation with Eσ70 will be efficiently regulated by σ competition in vivo. This prediction of the model is consistent with experimental data. V. Shingler (personal communication) showed that a weak promoter was more subject to σ competition than a strong promoter in vivo.

How would variation in the relative affinities of Eσs for DNA and σs for E affect predictions of the model? Our calculations suggest that when σA affinity for E is higher than that of σ70, or when EσA has tighter nonspecific DNA binding than Eσ70, equilibrium would shift toward binding to σA (Figs. 5 and 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), thereby decreasing Eσ70 promoter occupancy more than indicated by the simulations in Fig. 3. However, strong nonspecific binding of EσA to DNA is unfavorable for EσA binding to its cognate promoters. In fact, because EσA is present in much lower amounts than Eσ70, for significant binding of EσA to its cognate promoters either EσA nonspecific binding to DNA should be weaker than that of Eσ70 or promoter binding of EσA should be much tighter than that of Eσ70 (Figs. 5 and 6).

Concluding Remarks.

In this work, we remeasured the levels of E, σ70, σE, and σ32 in E. coli and developed an equilibrium model that describes the partitioning of RNAP between promoters, nonspecific DNA binding sites, and the cytoplasm. By exploring how critical parameters of the model affect promoter saturation with Eσ70 and the competition between σs, we have obtained important insights into each of these processes.

Our model suggests that nonspecific binding of holoenzyme to DNA plays a critical role in the extent of promoter saturation. It predicts that strong nonspecific DNA binding is required to keep promoters far from saturation. For their binding affinities to contribute to variation in promoter strength, and for activators to function by recruiting holoenzyme, weak promoters must be relatively free of holoenzyme in vivo, which requires strong nonspecific DNA binding of RNAP. Likewise, nonspecific binding of lac repressor to DNA was predicted to control equilibrium binding at the operator (16). Thus, in both cases nonspecific DNA binding is predicted to be necessary to understand the observed in vivo regulation.

The large pool of Eσs bound to DNA nonspecifically can effectively buffer weak promoters against changes in transcription by the strongest promoters in the cell. For example, if nonsaturating occupancy of promoters were achieved by having “just enough” Eσ to bind to promoters, decreased expression of the strongest promoters (e.g., rRNA promoters) would lead to very large increases in expression of weaker promoters. However, because much of the released Eσ will bind nonspecifically to DNA, the increase in transcription at weaker promoters is more modest, which may be necessary to allow appropriate regulation at such promoters.

Our model demonstrates that, for σ competition to occur, σs must be in excess over all E not involved in elongation (rather than in excess of only free E). Previously, the number of σ70 (29) was thought to be lower than the number of nonelongating E (34), although there was a great deal of evidence for σ competition (7–10, 14). Our new estimates and careful consideration of the previously published data (18, 20, 23, 24, 29, 31, 35) indicate that σ70 and thus total σs exceed nonelongating E, and our model rationalizes this finding: this condition is necessary for σ competition.

The model predicts that σ competition preferentially affects promoters that are far from saturation. This seems to be a sensible strategy. Promoters can be far from saturation because they have been designed to be intrinsically weak because only small amounts of their products are necessary for growth. Alternatively, under the particular conditions tested, the activator for that promoter may be nonfunctional. In either case, when remodeling transcription, it makes sense to shut off such promoters first. This has been experimentally validated in one case (V. Shingler, personal communication). The generality of this idea can now be subjected to experimental test.

Materials and Methods

Protein Purification and Quantification.

His-tagged σ70, σE, σ32, and the periplasmic domain of RseA, as well as E and GST-tagged σE, were overproduced and purified as previously described (36–40). E was quantified by UV A280 nm absorbance [E280 nm1%= 5.5 (41)]. σ70 was quantified by Coomassie staining because degradation products were visible on the gel. Because the degradation products would be included in the UV A280 nm measurement, the amount of intact σ70 would be overestimated. Indeed, concentration of His-tagged σ70 based on the UV A280 nm measurement (E280 nm1% = 8.07 for His6-σ70) was 4.1 mg/ml, 1.5-fold higher than estimated by Coomassie. In the Coomassie staining protocol, purified proteins and known amounts of BSA were coelectrophoresed on the Tris-glycine SDS gels and then stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 for 20 min and destained overnight. Protein staining was quantified by densitometric analysis using the AlphaImager 2200. A linear calibration curve, obtained from Coomassie staining of the BSA standards, was used to quantify the concentrations of the purified proteins. His6-σE and His6-σ32 were also quantified by Coomassie staining.

Strains and Media.

The bacterial strains used in this work were E. coli CAG51114 (MG1655 φλ[rpoHP3-lacZ] ΔlacX74), wild-type cells (wt); CAG19193 (ML 20035 rpoH::kanR λPHS-lacZ, kanR), the Δσ32 cells (42); CAG22216 [ΔlacX74 galK galU Δ(araABC-leu)7679 araD139 hsdR rpsL mcrB rpoE/Ω λP3-lacZ], the ΔσE cells; and RL1120 (W3110 trpR tnaA2 rpoB5201) (43). Cells were grown at 30°C in M9 glucose medium, prepared as described (44) and supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 1 mM MgSO4, and 2 μg/ml thiamine (M9 minimal) or in M9 glucose plus amino acids (M9 complete), which contained the previous components and all amino acids (40 μg/ml). Wild-type, RL1120, and CAG19193 cells were grown in both M9 minimal and M9 complete, and CAG22216 cells were grown in M9 complete only.

Preparation of Whole-Cell Extracts and Protein Level Measurements by Quantitative Western Blots.

At OD450 ≈ 0.16 (for M9 minimal) or OD450 ≈ 0.275 (for M9 complete), 1 ml of culture was added to 111 μl of ice-cold 50% trichloroacetic acid, incubated on ice for >15 min, centrifuged, resuspended, and boiled (5 min) in Laemmli sample buffer. These extracts were used for measuring the intracellular levels of σ70, σE, σ32, and E.

The efficiency of protein staining with antibodies after transfer to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane differed for purified proteins alone and these same proteins mixed with whole-cell extract (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). To approximate conditions of the protein to be measured, we generated calibration curves by mixing known amounts of purified His6-σ70, His6-σE, His6-σ32, or E, respectively, with cellular extracts from wild type, ΔrpoE (CAG22216), ΔrpoH (CAG19193), or RL1120 (whose β-subunit is modified by addition of protein A so that it runs at a higher molecular weight than authentic β). Samples with equal amounts of the total cellular protein but different amounts of the purified protein standards were loaded onto Tris-glycine SDS gels, and separated proteins were directly electroblotted onto poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes. Blots were probed with dilutions of polyclonal antibodies specific to σ70, σE, σ32, or β and then incubated with a 1:10,000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies. Blots were developed with the SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate from Pierce. The signal was visualized by a charge-couple device, which eliminates nonlinearities due to properties of the film.

For σ70, intracellular levels were determined directly from the calibration curve samples, which contained both His6-σ70 and σ70 (Fig. 8A, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). For σE (Fig. 8B) and σ32, intracellular levels were determined from extracts of wild-type cells run on the same gel as the calibration samples (which contained His6-σE or His6-σ32 mixed with extracts of strain lacking, respectively, σE and σ32). For the β-subunit of E, intracellular levels were determined from extracts of wild-type cells on the same gel as the calibration samples [E mixed with extracts of RL1120 (Fig. 8C)].

The signals of known amounts of the purified proteins within the linear range were fitted to a straight line and used to measure intracellular concentrations using an appropriate dilution of the cell extract (for example, see Fig. 8). All quantification experiments were repeated at least three times.

Measurement of the Total Cellular Protein.

At OD450 of 0.16 (M9 glucose) and 0.275 (M9 complete), 0.9 ml of cell culture was added to 0.1 ml of ice-cold 50% trichloroacetic acid, incubated on ice for 15 min, centrifuged, resuspended in 0.1 ml of 5% SDS/0.1 M TrisBase by vortexing and boiling for 5 min, and used to measure total cellular protein. The calibration curve was constructed from trichloroacetic acid-precipitated 0.9-ml samples of varying concentrations of BSA in M9 glucose or M9 complete medium. A total of 0.1 ml of either the resuspended cellular protein samples or the BSA standards was mixed with 2 ml of BCA working reagent (from BCA protein kit) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. The signal was measured at OD590 versus water. The signals of the BSA standards were fitted by a straight line (in the linear range), which was used to calculate total cellular protein concentration. Experiments were repeated twice.

Measurement of the Number of Cells.

A total of 0.1 ml of consecutive dilutions of cells in M9 minimal (OD450 = 0.16) or M9 complete (OD450 = 0.275) was plated on LB plates and incubated at 37°C, and cells were calculated from the numbers of colonies on the plates. Experiments were repeated three times.

Development of Equilibrium Model.

A mathematical model was developed to study partitioning of RNAP between specific (promoters) and nonspecific sites on DNA and a pool of free RNAP in the cytoplasm. The model considers one major σ factor, labeled as σ70, and one alternative σ factor, labeled as σA. It describes equilibrium binding between (i) free E and the σs, (ii) Eσs and promoters, and (iii) E and Eσs binding to nonspecific DNA sites (Fig. 1). The following assumptions are used in the equilibrium model: (i) binding of E and Eσs to DNA is reversible; (ii) σ70 promoters can be occupied only by Eσ70 (and σA promoters only by EσA); (iii) σ70 and σA have the same binding affinity for free E; (iv) all σ70 promoters have the same binding affinity for Eσ70 (and all σA promoters have the same affinity for EσA); and (v) E, Eσ70, and EσA bind to nonspecific DNA sites with the same affinity. For simulation of RNAP partitioning between various pools, we set σA = 0, because under “normal” growth conditions the alternative σ factors available for binding to E comprise a small fraction of total σs. For simulation of σ competition, we set σA promoters = 0, because there are many more promoter sites for σ70 than for alternative σs (45). Simulations varying specific and nonspecific binding of EσA are presented in Supporting Text. Parameters used in calculations are summarized in Table 4, column 3, and in Supporting Text. Details of model’s equations, parameter selection and calculation, and discussion of the assumptions are given in Supporting Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is dedicated to Naum J. Phleger, who conceptualized the initial formulation of this model and was intimately involved in its development. He was a wonderful collaborator. We thank Peter von Hippel, Hana El-Samad, Hao Li, Morten Kloster, Victoria Shingler, Ann Hochschild, Tom Record, Ruth Spolar, and Patricia Kiley for interesting discussions and the critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant GM36278-18 from the National Institutes of Health (to C.A.G.) and a Burroughs Wellcome Predoctoral Fellowship awarded to I.L.G.

Abbreviation

- RNAP

RNA polymerase.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Gross C. A., Chan C., Dombroski A., Gruber T., Sharp M., Tupy J., Young B. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 1998;63:141–155. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.deHaseth P. L., Zupancic M. L., Record M. T., Jr. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:3019–3025. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3019-3025.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClure W. R. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985;54:171–204. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.001131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buc H., McClure W. R. Biochemistry. 1985;24:2712–2723. doi: 10.1021/bi00332a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saecker R. M., Tsodikov O. V., McQuade K. L., Schlax P. E., Jr., Capp M. W., Record M. T., Jr. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;319:649–671. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlax P. J., Capp M. W., Record M. T., Jr. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;245:331–350. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hicks K. A., Grossman A. D. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;20:201–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jishage M., Kvint K., Shingler V., Nystrom T. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1260–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.227902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nystrom T. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;54:855–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurie A. D., Bernardo L. M., Sze C. C., Skarfstad E., Szalewska-Palasz A., Nystrom T., Shingler V. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:1494–1503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y. N., Gross C. A. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:7128–7137. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7128-7137.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farewell A., Kvint K., Nystrom T. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:1039–1051. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jishage M., Ishihama A. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:3768–3776. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.12.3768-3776.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y. N., Walter W. A., Gross C. A. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:5005–5012. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5005-5012.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.deHaseth P. L., Lohman T. M., Burgess R. R., Record M. T., Jr. Biochemistry. 1978;17:1612–1622. doi: 10.1021/bi00602a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Hippel P. H., Revzin A., Gross C. A., Wang A. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1974;71:4808–4812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.12.4808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kao-Huang Y., Revzin A., Butler A. P., O’Conner P., Noble D. W., von Hippel P. H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1977;74:4228–4232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.10.4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jishage M., Iwata A., Ueda S., Ishihama A. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:5447–5451. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5447-5451.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maeda H., Jishage M., Nomura T., Fujita N., Ishihama A. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:1181–1184. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.4.1181-1184.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jishage M., Ishihama A. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:6832–6835. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6832-6835.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalbow D. G. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;75:181–184. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90537-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwakura Y., Ishihama A. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1975;142:67–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwakura Y., Ito K., Ishihama A. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1974;133:1–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00268673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matzura H., Hansen B. S., Zeuthen J. J. Mol. Biol. 1973;74:9–20. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90350-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matzura H., Molin S., Maaloe O. J. Mol. Biol. 1971;59:17–25. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedersen S., Bloch P. L., Reeh S., Neidhardt F. C. Cell. 1978;14:179–190. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raffaelle M., Kanin E. I., Vogt J., Burgess R. R., Ansari A. Z. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grainger D. C., Hurd D., Harrison M., Holdstock J., Busby S. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17693–17698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506687102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishihama A. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000;54:499–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engbaek F., Gross C., Burgess R. R. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1976;143:291–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00269406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakamura Y., Yura T. J. Mol. Biol. 1975;97:621–642. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soupene E., van Heeswijk W. C., Plumbridge J., Stewart V., Bertenthal D., Lee H., Prasad G., Paliy O., Charernnoppakul P., Kustu S. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:5611–5626. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.18.5611-5626.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shepherd N., Dennis P., Bremer H. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:2527–2534. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2527-2534.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bremer H., Dennis P. P. Escherichia coli and Salmonella Cellular and Molecular Biology. In: Neidhardt F. C., editor. Vol. 2. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol; 1996. pp. 1553–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawakami K., Saitoh T., Ishihama A. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1979;174:107–116. doi: 10.1007/BF00268348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharp M. M., Chan C. L., Lu C. Z., Marr M. T., Nechaev S., Merritt E. W., Severinov K., Roberts J. W., Gross C. A. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3015–3026. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.22.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campbell E. A., Tupy J. L., Gruber T. M., Wang S., Sharp M. M., Gross C. A., Darst S. A. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1067–1078. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gamer J., Multhaup G., Tomoyasu T., McCarty J. S., Rudiger S., Schonfeld H. J., Schirra C., Bujard H., Bukau B. EMBO J. 1996;15:607–617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young B. A., Anthony L. C., Gruber T. M., Arthur T. M., Heyduk E., Lu C. Z., Sharp M. M., Heyduk T., Burgess R. R., Gross C. A. Cell. 2001;105:935–944. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gruber T. M., Gross C. A. Methods Enzymol. 2003;370:206–212. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)70018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgess R. R. In: RNA Polymerase. Losick R., Chamberlin M. J., editors. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1976. pp. 69–100. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kusukawa N., Yura T. Genes Dev. 1988;2:874–882. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.7.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Opalka N., Mooney R. A., Richter C., Severinov K., Landick R., Darst S. A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:617–622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sambrook J., Fritsch E., Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salgado H., Gama-Castro S., Martinez-Antonio A., Diaz-Peredo E., Sanchez-Solano F., Peralta-Gil M., Garcia-Alonso D., Jimenez-Jacinto V., Santos-Zavaleta A., Bonavides-Martinez C., Collado-Vides J. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D303–D306. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.