Abstract

Naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T regulatory (Treg) cells have been shown to inhibit adaptive responses by T cells. Natural killer (NK) cells represent an important component of innate immunity in both cancer and infectious disease states. We investigated whether CD4+CD25+ Treg cells could affect NK cell function in vivo by using allogeneic (full H2-disparate) bone marrow (BM) transplantation and the model of hybrid resistance, in which parental marrow grafts are rejected solely by the NK cells of irradiated (BALB/c × C57BL/6) F1 recipients. We demonstrate that the prior removal of host Treg cells, but not CD8+ T cells, significantly enhanced NK cell-mediated BM rejection in both models. The inhibitory role of Treg cells on NK cells was confirmed in vivo with adoptive transfer studies in which transferred CD4+CD25+ cells could abrogate NK cell-mediated hybrid resistance. Anti-TGF-β mAb treatment also increased NK cell-mediated BM graft rejection, suggesting that the NK cell suppression is exerted through TGF-β. Thus, CD4+CD25+ Treg cells can potently inhibit NK cell function in vivo, and their depletion may have therapeutic ramifications for NK cell function in BM transplantation and cancer therapy.

Keywords: anti-CD25, bone marrow transplantation, hybrid resistance, Foxp3

Natural killer (NK) cells represent a key component of the innate immune system and can mediate MHC unrestricted cytotoxicity against neoplastic and virally infected cells; they also are capable of secreting numerous effector cytokines (1, 2). In addition, NK cells can mediate rejection of bone marrow (BM) but not solid-tissue allografts (3, 4). Studies by Cudkowicz and Bennett (5) have shown that NK cells are responsible for the phenomenon of “hybrid resistance,” in which parental BM cells (BMCs) are rejected by lethally irradiated F1 hybrid recipients. Aside from their ability to kill target cells directly, NK cells have also been shown to modulate adaptive immune responses, presumably in part through the release of numerous cytokines (6). NK cells have been shown to promote T helper 1-type responses (7, 8) and participate in dendritic cell maturation (9) and the generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and tumor-specific memory T cells against various tumors (10, 11). Thus, although the influence of NK cells on adaptive immunity has been well documented, little has been elucidated regarding the influence of components of the adaptive immune system on NK cells.

Naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T regulatory (Treg) cells have been shown to be critical immunomodulatory cells capable of suppressing immune responses. CD4+CD25+ Treg cells have been shown to be important for maintaining self-tolerance (12), regulating the homeostasis of the peripheral T cell pool (13), contributing to tolerance induction after solid organ transplantation (14), and providing protection from graft-versus-host disease lethality in BM transplantation (BMT) models (15, 16). These immunosuppressive thymus-derived cells represent a small fraction (5–10%) of CD4+ T cells that constitutively express IL-2 receptor α (CD25) (17), cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (18), and the transcription factor Foxp3 (19). CD4+CD25+ Treg cells have been shown to suppress T cell responses both in vitro and in vivo (12), although the precise mechanisms underlying the Treg-mediated inhibition of immune responses remain to be defined.

There have been numerous reports that the functional activity of NK cells may be under the influence of T cell control. For example, T cell-deficient athymic mice were found to have augmented NK cell function in tumor resistance models (20, 21). We have previously reported that mice with severe combined immune deficiency and that lack T and B cells not only could reject allogeneic BMCs but actually displayed markedly heightened BMC rejection capability and could resist allogeneic BMC (3). These studies would suggest that T cells can possibly down-regulate NK cell-mediated BM rejection in vivo.

In this article, we provide direct evidence that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells can modulate NK cell function in vivo. NK cell-mediated BMC rejection was significantly augmented with prior Treg depletion of the recipient mice. Further, transfer of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells could suppress this rejection in vivo. These results demonstrate a potentially important regulatory link between adaptive and innate immune responses.

Results

Enhanced BM Rejection in Full MHC-Mismatched and Hybrid Resistance BMT Models by CD25+ Cell Depletion.

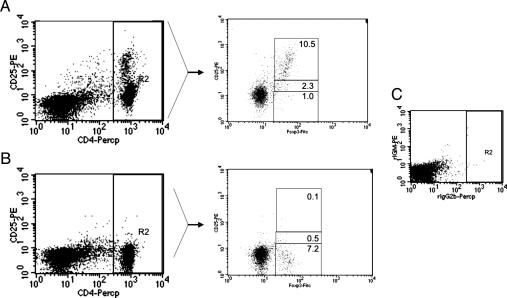

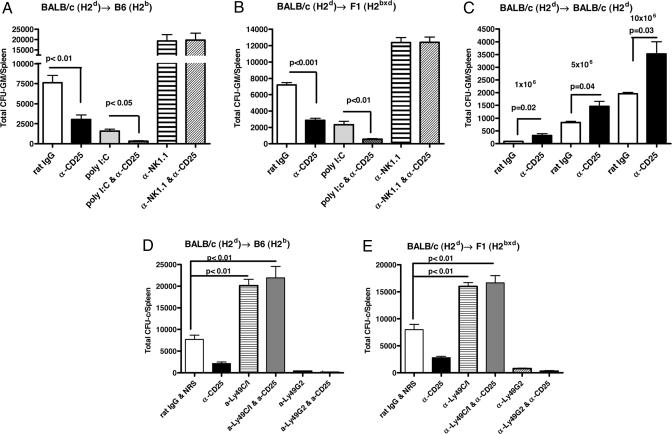

To determine the role of host CD4+CD25+ Treg cells on allogeneic and parental BM graft rejection, we used anti-CD25 mAbs to deplete this population in vivo. Recipient mice were treated with anti-CD25 or control antibody for 2 days before BMT. Treatment with anti-CD25 antibody (PC61) essentially eliminated CD25+ T cells (as detected with the 7D4 clone) and caused a marked, but not complete, reduction in the percentage of Foxp3+ cells in the lymph nodes of recipients (Fig. 1). The fact that we have found that PC61 anti-CD25 does not block the binding of 7D4 anti-CD25 (data not shown) indicates that either all CD25+ cells were eliminated or CD25 cell surface expression was down-modulated in a percentage of cells after in vivo treatment with anti-CD25. This observation for the presence of CD4+CD25−Foxp3+ cells after anti-CD25 treatment is described in ref. 22. After CD25+ cell depletion, lethally irradiated B6 (H2b) and F1 hybrid (H2bxd) recipients (9.0 and 11.0 Gy, respectively) were transplanted with BALB/c (H2d) BMCs at BMC doses in which resistance was only partial. Six days after BMT, the level of BMC engraftment was determined by measuring the colony-forming unit–granulocyte/monocytes (CFU-GMs) in spleen as an indicator of early post-BMT donor-derived hematopoiesis that occurs after lethal total body irradiation (TBI). The data (Fig. 2A and B) demonstrate that lethally irradiated B6 and CB6F1 hybrid mice were not capable of significantly resisting H2d BMC at these doses (20 × 106 and 10 × 106, respectively). In these anti-CD25-treated recipients, the rejection of the donor BMCs was significantly increased after the depletion of host CD4+CD25+ T cells in comparison with the control group (B6, P < 0.01; CB6F1, P < 0.001). Rejection depended on host NK cells, as demonstrated by the increased engraftment of BMCs in recipient mice treated first with anti-NK1.1 (P < 0.001 compared with rat IgG treatment). The combined depletion of both host NK cells and CD25+ cells resulted in similar levels of BMC engraftment in comparison with mice treated with anti-NK1.1 mAbs alone, indicating that the anti-CD25-mediated effects on engraftment were contingent on host NK cells. Prior in vivo activation of NK cells by administration of polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid [poly(I:C)] also increased BMC rejection (P < 0.001), as demonstrated by us and others (3, 23). The increased level of resistance observed by anti-CD25 administration was comparable with that seen with poly(I:C). Interestingly, coadministration of anti-CD25 mAb with poly(I:C) significantly enhanced graft resistance compared with recipients receiving either treatment alone (B6, P < 0.05; CB6F1, P < 0.01), suggesting that the mechanisms by which the NK activity was increased were separate and distinct. Thus, in vivo removal of host CD4+CD25+ Treg cells strongly enhances NK cell-mediated allogeneic and parental BM rejection.

Fig. 1.

Decrease in Foxp3 level in CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in anti-CD25-treated mice. Lymph node cells from rat IgG- and anti-CD25-treated mice (1 mg at days −4 and −2) were stained for CD4 and CD25, followed by anti-Foxp3 intracellular staining and analysis by flow cytometry. In comparison with untreated mice (A), the CD4+ cells of lymph nodes from anti-CD25-treated mice (B) exhibited few Foxp3+ Treg cells. In C, isotype-matched controls were used. These results are representative of three different experiments.

Fig. 2.

In vivo depletion of host CD25+ cells enhances allogeneic and parental BM rejection and syngeneic BM engraftment. B6 (H2b) mice (A and D) and CB6F1 hybrid (H2bxd) mice (B and E) received various treatments before irradiation and transplantation: rat IgG or anti-CD25, anti-Ly49C/I (5E6), or anti-Ly49G2 (4D11) at day −4 and day −2, anti-NK1.1 at day −2, and/or poly(I:C) at day −2. Lethally irradiated B6 mice (9.0 Gy) and CB6F1 hybrid mice (11.0 Gy) received 20 × 106 and 10 × 106 H2d BMCs, respectively (three to four mice per group). On day 6 after BMT, splenic CFU-GMs were assessed. Enhanced allogeneic (A) and parental (B) BM graft rejection occurred after removal of host CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. A representative experiment from a total of four independent experiments is presented. (C) BALB/c (H2d) mice were treated with rat IgG and anti-CD25 mAb as described above and received lethal TBI (7.0 Gy) and escalating doses of syngeneic BMCs (three to four mice per group). Enhanced syngeneic BM engraftment occurred after the depletion of host CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. One of three experiments is presented. The effect of coadministration of anti-Ly49 and anti-CD25 mAbs was determined in B6 (H2b) mice (D) and F1 hybrid (H2bxd) mice (E). Enhanced allogeneic and parental BM graft engraftment occurred after removal of Ly49C/I+ NK cells with 5E6 and CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. In contrast, depletion of Ly49G2+ NK cells with 4D11 and CD4+CD25+ Treg cells increases BM rejection. Three independent experiments were performed. Values are represented as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA (A, B, D, and E) and unpaired Student's t tests (C) were used. NRS, normal rat serum.

To verify that the removal of host CD4+CD25+ Treg cells was not deleterious to normal hematopoietic recovery, syngeneic BMT studies were performed. Anti-CD25 was administered to BALB/c mice before receiving a myeloablative dose of TBI and followed by infusion of escalating doses of BALB/c BMCs (1 × 106 to 10 × 106). Surprisingly, analysis of splenic CFU-GMs demonstrated that early hematopoietic recovery was significantly enhanced (P < 0.05) in mice depleted of CD25+ cells, signifying that removal of these cells was not impairing hematopoietic engraftment (Fig. 2C). Thus, the increased NK cell-mediated rejection of the donor BMCs observed in mice after anti-CD25 treatment occurred despite potential increases in myelopoiesis, which was observed in the syngeneic models.

Allogeneic and parental BMC graft rejection is largely controlled by the coexpression of various inhibitory and stimulatory Ly49 receptors on NK cells whose ligands are MHC class I molecules (24). It has been previously shown that removal of the NK cell subset expressing Ly49C/I from homozygous H2b or heterozygous H2bxd recipient abrogates rejection to donor H2d BM grafts, whereas the removal of Ly49G2+ NK cells increases H2d BMC rejection (24, 25). We investigated the impact of the depletion of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in combination with the removal of Ly49C/I+ or Ly49G2+ NK cells on H2d marrow engraftment in B6 (H2b) and F1 (H2bxd) mice (Fig. 2 D and E). The codepletion of Ly49C/I+ NK cells and CD25+ cells from recipient mice significantly promoted H2d BMC engraftment compared with control mice (P < 0.01). These results indicate that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells suppress a defined NK cell subset that mediates BMC rejection based on Ly49/H2-specific recognition.

In Vivo Depletion of Host CD4+, but Not CD8+, T Cells Enhances H2d BMC Rejection in B6 and CB6F1 Hybrid Mice.

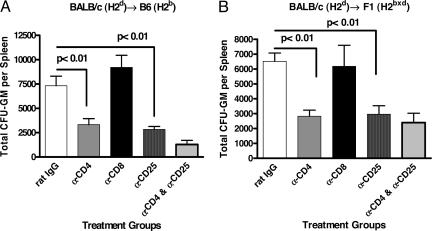

To confirm the role of host CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in the suppression of the NK-mediated rejection, recipient mice were pretreated with anti-CD8 or anti-CD4 and/or anti-CD25-depleting mAbs. Antibody treatment resulted in the depletion of ≈99% of the relevant CD4+ or CD8+ cell populations (data not shown). As seen in Fig. 3, no change in donor BMC resistance was observed in mice treated with anti-CD8 mAbs compared with rat IgG-treated mice. In contrast, mice treated with anti-CD4 demonstrated significant increases in BMC rejection (Fig. 3A, B6, P < 0.01; and Fig. 3B, CB6F1, P < 0.01) comparable with mice depleted of CD25+ cells. Coadministration of anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 mAbs did not result in a significant increase of BM rejection when compared with the administration of each of the mAbs alone. These data suggest that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells are the T cell population that mainly regulates NK cell-mediated H2d BMC rejection.

Fig. 3.

Enhanced allogeneic and parental BM rejection after anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 treatment. B6 (H2b) and F1 (H2bxd) mice received various mAb treatments (rat IgG or anti-CD25 mAb at day −4 and day −2 and anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 mAb at day −2) before irradiation and transplantation. Lethally irradiated B6 (H2b) (9.0 Gy) (A) and F1 (H2bxd) (11.0 Gy) (B) mice were injected with 20 × 106 and 10 × 106 H2d BMCs, respectively (three to four mice per group). Splenic CFU-GMs were assessed on day 6 after BMT. Three separate experiments were performed. Enhanced allogeneic and parental BM rejection occurred after treatment with anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 but not with anti-CD8 mAbs. Values are represented as mean ± SD (one-way ANOVA).

In Vivo Administration of Anti-CD25 mAb Results in Decreased Long-Term Survival/Donor Chimerism After Allogeneic BMT.

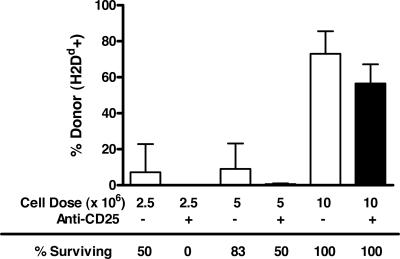

We have recently shown that rejection of hematopoietic progenitors shortly after allogeneic BMT does not always correlate with long-term reconstitution and donor chimerism (26). To determine whether depletion of CD25+ cells impairs long-term reconstitution of the donor graft, we transplanted B6 (H2b) recipients with increasing doses of allogeneic (BALB/c; H2d) BMCs after the infusion of anti-CD25 or rat IgG mAbs. The results mirror those seen with the CFU assays. At lower cell doses (2.5 × 106 and 5 × 106 BMCs), death caused by BM failure was increased in allogeneic graft recipients that were depleted of CD25+ cells (Fig. 4) compared with recipients that received control antibody infusions. In surviving mice that received 5 × 106 or 10 × 106 allogeneic BMCs, lower levels of donor (H2d) cells were observed in the spleen on day 35 after BMT. Survival of the recipients correlated with the chimerism results in which greater survival was observed in mice not treated with anti-CD25. These results demonstrate that the removal of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells results in decreased long-term survival/donor chimerism in allogeneic BMT.

Fig. 4.

Decreased survival and reduced donor chimerism in CD25-treated mice. B6 (H2b) mice received rat IgG or anti-CD25 mAbs at day −4 and day −2 before irradiation and transplantation. Mice were then irradiated (9.0 Gy) and transplanted with 2.5 × 106, 5.0 × 106, or 10 × 106 BALB/c (H2d) BMCs (six mice per group). Mice were monitored for survival. On day 35 after BMT, surviving mice were assessed for donor chimerism. Spleen cells were labeled with anti-H2Dd and anti-H2Kb. The frequency of donor H2Dd expression in surviving mice is shown. A representative experiment from two independent experiments is presented. Values are shown as mean ± SD.

In Vivo Administration of Neutralizing Antibodies to TGF-β Enhances H2d BMC Rejection in B6 and CB6F1 Hybrid Mice.

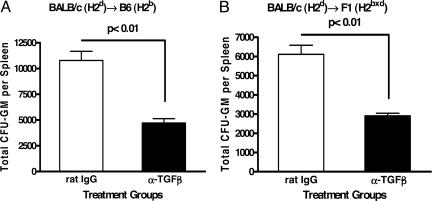

CD4+CD25+ T cells have been shown to produce the immunosuppressive cytokine TGF-β (27, 28) and inhibit NK cell activity in vitro (29) and in vivo (30–33). To assess the effect of the neutralization of endogenously produced TGF-β on BMC graft rejection, B6 and F1 mice were injected with a neutralizing anti-TGF-β mAb (1D11) before BMT. Anti-TGF-β mAb treatment significantly increased BM graft rejection in both mouse strains (Fig. 5A, B6, P < 0.01; and Fig. 5B, F1, P < 0.01). These results suggest that TGF-β may be a contributing mechanism by which Treg cells suppress NK cell-mediated BM rejection in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Enhanced allogeneic and parental BM rejection after anti-TGF-β treatment. B6 (H2b) and F1 (H2bxd) mice received rat IgG or anti-TGF-β mAb at days −4, −2, and 0 before irradiation and transplantation. Lethally irradiated B6 (H2b) (9.0 Gy) (A) and F1 (H2bxd) (11.0 Gy) (B) mice were injected with 20 × 106 and 10 × 106 H2d BMCs, respectively (three to four mice per group). Splenic CFU-GMs were assessed on day 6 after BMT. Three separate experiments were performed. Enhanced allogeneic and parental BM rejection occurred after treatment with anti-TGF-β mAb. Values are represented as mean ± SD (unpaired Student's t test).

Adoptive Transfer of Donor CD4+CD25+ Treg Cells Suppresses NK Cell-Mediated BMC Rejection in the Hybrid Resistance BMT Model.

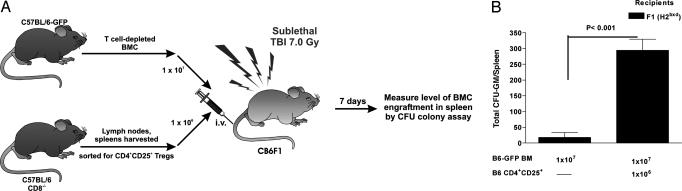

Recently, we reported that the addition of donor CD4+CD25+ Treg cells affected the outcome in a complete MHC-mismatched BMT model (B6 → BALB/c) in which both host T and NK cells can mediate resistance. In this model, the addition of donor CD4+CD25+ Treg cells resulted in greater lineage-committed and multipotential donor progenitors in recipient spleens 1 week after transplantation and significantly increased long-term multilineage donor chimerism in sublethally irradiated recipients (34). We have now assessed the capacity of transferred CD4+CD25+ Treg cells to affect donor BMC rejection in the hybrid resistance model, which is solely mediated by host NK cells. As seen in Fig. 6A, F1 (H2bxd) hybrid mice were conditioned with TBI (7.0 Gy) and received a BMT 1 day later with donor H2b T cell-depleted BM from B6-GFP mice with and without coadministration of enriched CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. The sublethal conditioning dose of 7.0 Gy was selected to leave intact a significant myeloid compartment and increased host resistance capacity. CB6F1 hybrid mice receiving CD4+CD25+ Treg cells at the time of BMT demonstrated significantly higher numbers of donor CFU-GMs compared with control recipients (Fig. 6B, averaged 13.3-fold increases, P < 0.001) with donor chimerism confirmed by flow cytometry (data not shown). These results support the depletion data and confirm that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells strongly suppress NK cell-mediated BM graft rejection.

Fig. 6.

Donor CD4+CD25+ Treg cells enhance progenitor cell recovery after transplant into recipients that can mediate NK- but not T cell-dependent marrow allograft resistance. (A) Enriched H2b CD4+CD25+ T cells (1 × 106) were cotransplanted with H2b-GFP T cell-depleted BMCs into 7.0-Gy conditioned F1 (H2bxd) (10 × 106 BM T cell-depleted) recipients. (B) Spleen cells were removed from recipients (n = 3 per group), pooled, and plated for CFU-GMs. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate cultures. The results of two individual H2b → H2bxd experiments averaged 13.3-fold increases (unpaired Student's t test).

Discussion

In this article, we provide evidence that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells suppress NK cell-mediated BMC rejection in vivo. Removal of these immunosuppressive cells augmented NK activity, whereas their addition inhibited activity as reflected by BMC engraftment. These data reconcile early observations of heightened NK activity in T cell-deficient mice, including heightened ability to reject BMC allografts and represent an additional link between adaptive and innate immunity. NK cells have been previously shown by us and others to be capable of both up- and down-modulating T cell function (10, 11, 35, 36). The results presented here demonstrate that a reciprocal arrangement exists in which T cells can also down-regulate NK cell function. Although NK cell activity appears to be the predominant parameter affected, it remains to be determined whether prolonged Treg depletion also alters NK cell number and/or phenotype. It will also be of particular interest to assess models in which increased Treg cells (e.g., models where heavy or prolonged tumor burden is present) may exist. The effects of Treg depletion on the NK cell populations may be even more striking.

CD4+CD25+ Treg cells have been shown to suppress T cell (12, 37), NK T cell (38), and monocyte/macrophage function (39). However, studies demonstrating direct effects of T cells in regulating NK cell-mediated BMC rejection have been lacking. NK and T cells can resist engraftment of fully MHC-mismatched allogeneic marrow (5), but in hybrid resistance, NK cells have been identified as the only host immune elements capable of rejecting parental-strain hematopoietic cell grafts (5, 40). We found that depletion of host CD4+CD25+ Treg cells enhances NK cell-mediated BM rejection in the full MHC-mismatched and hybrid resistance BMT models. Moreover, adoptive transfer of donor-type CD4+CD25+ Treg cells into sublethally conditioned F1 (H2bxd) hybrid mice resulted in decreased rejection of H2d BM grafts mediated by NK cells. With the advent of reduced intensity conditioning in clinical BMT, there will likely be an increased incidence of graft rejection by host NK cells. The data presented here suggest that transfer of Treg cells can indeed be used to promote engraftment.

The mechanisms by which CD4+CD25+ T cells mediate their suppressive effects on NK cells are not yet determined and may involve multiple events, particularly in vivo. The immunosuppressive properties of Treg cells appear to be mediated mainly by the immunosuppressive cytokine TGF-β. The inhibitory effect of TGF-β on NK cell activity in vitro is well known (29), and in vivo models strongly imply that TGF-β is essential for suppression of NK cells by CD4+CD25+ T cells (30). The cellular source of the TGF-β was not addressed in our studies but can be derived from the immunosuppressive regulatory T cells. Recent studies have demonstrated that Treg cells can suppress NK cell-mediated tumor killing by membrane-bound TGF-β (30). Our data showing that anti-TGF-β mAb treatment increases NK cell-mediated BM graft rejection raises the possibility that Treg-mediated NK suppression is exerted through TGF-β in our BMT models. However, it cannot be excluded that other mechanisms may be involved. For instance, the impaired production of IL-2 by CD4+ T cells (41) or IL-12 by dendritic cells (42), potent NK stimulators, may be an indirect way by which Treg cells modulate NK cell activity. Moreover, CD4+CD25+ Treg cells may indirectly suppress NK cell activity through the modulation of macrophage function by inhibiting the production of IL-15 and IL-18. NKG2D has been demonstrated to be critical in the rejection of H2d BMCs (43). Recent studies also suggest that modulation of NKG2D may be a mechanism by which Treg cells suppress NK cell function (30, 43–45). However, our adoptive transfer data demonstrating that B6 (H2b) BMC rejection is abrogated with Treg cell transfer into CB6F1 hybrid recipients would suggest that NKG2D is not the only pathway that is affected.

In the BMT scenario, Treg cells may function to inhibit donor cell engraftment and immune reconstitution either by suppressing direct NK cell killing of BM precursors and/or the production of inhibitors of hematopoiesis by these effectors (e.g., IFN-γ and TNF-α) (6). The increased engraftment of syngeneic BMCs observed after Treg depletion is of interest. In this instance, CD4+CD25+ Treg cells may suppress hematopoietic progenitors through the production of cytokines that impede hematopoiesis directly (e.g., TGF-β and IL-10) or suppress cells that promote hematopoiesis (e.g., T cell production of IL-3/GM-colony-stimulating factor or macrophage production of colony-stimulating factors). Although the mechanism remains to be elucidated, the data suggest that the removal of Treg cells increases immune and myeloid reconstitution after autologous BMT. However, the use of Treg cell depletion in allogeneic BMT may result in increased donor BMC rejection. The observations that increased NK cell-mediated rejection occurred after Treg cell removal despite concurrent promotion of hematopoietic recovery suggests that the increased NK activity is even more prominent. It will be also of interest to ascertain the role of Treg cells in other models (e.g., viral) where NK cells play an important role.

In summary, we demonstrate that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells can suppress in vivo responses mediated by NK cells. This unique immunoregulatory link between adaptive and innate lymphocytes provides evidence for reciprocal interactions between the two arms of the immune system. The present findings enhance overall understanding of the regulation of immune responses and are particularly important for the development of therapeutic strategies to improve both BMT and cancer treatment involving NK cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

BALB/c (H2d), C57BL/6 (B6; H2b), and BALB/c × C57BL/6 F1 (CB6F1 or F1 H2bxd) mice were obtained from the Animal Production Area at the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD), and B6 CD8−/− (H2b) mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. C57BL/6 TgN(act-EGFP)OsbC15-001-FJ001 GFP transgenic breeder mice (B6-GFP) were originally provided by Timothy Ley (Washington University, St. Louis). All mice were maintained in microisolators under specific pathogen-free conditions. Mice were 8–12 weeks of age at the start of experiments.

Myeloablative BMT Studies.

B6, BALB/c, and CB6F1 hybrid mice were given sulfomethoxazole-trimethoprim (Schein Pharmaceutical, Corona, CA) in the drinking water 7 days before BMT. Before BMT, mice were injected i.p. with the following antibodies: 1 mg of rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch); 1 mg of anti-CD25 (PC61; National Cell Culture Center, Minneapolis) at days −4 and −2 before BMT (CD4+CD25+ cells were undetectable on lymph nodes for 8 days from day 0); 200 μg of anti-NK1.1 (PK136), a gift from J. R. Ortaldo (National Cancer Institute); 300 μg of anti-CD4 (GK1.5) or 300 μg of anti-CD8 (YTS169.4), generously provided by G. B. Huffnagle (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor) at day −2 before BMT; 5% of normal rat serum (NRS; Jackson ImmunoResearch); 500 μg of anti-Ly49C/I (5E6) and 200 μg of anti-Ly49G2 (4D11) provided by M. Bennett (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas) at days −4 and −2 before BMT or 120 μg of poly(I:C) (Sigma) at day −2; and 200 μg of anti-TGF-β (1D11), a gift from F. W. Ruscetti (National Cancer Institute), at days −4, −2, and 0. On the day of transplant (day 0), mice were lethally irradiated with a 137Cs source (B6 at 9.0 Gy, CB6F1 at 11.0 Gy, and BALB/c at 7.0 Gy) and later injected i.v. with 20 × 106 and 10 × 106 BMCs from BALB/c mice. BALB/c recipients were transplanted with 1 × 106, 5 × 106, or 10 × 106 BALB/c BMCs. The level of BMC engraftment was determined by measuring CFU-GM content in the spleen 6 days after BMT as described below. For the long-term donor chimerism studies, mice were previously treated with 1 mg of rat IgG or anti-CD25 mAb at days −4 and −2 before they were irradiated and transplanted with different doses of BALB/c (H2d) BMCs (2.5 × 106, 5 × 106, or 10 × 106). Mice were monitored for survival and analyzed for levels of H2d 35 days after BMT. Six mice per group were used.

CFU-GM Assay.

CFU-GM assays were performed as described (26, 34). Briefly, recipient spleens were collected on day 6 after BMT, and a single-cell suspension of each spleen was prepared. The spleen cells (1.5 × 105 to 5 × 105) were cultured in colony assay medium supplemented with colony stimulatory factors in 35-mm Petri dishes. Cultures were established in triplicate for each concentration and maintained for 5–7 days at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. Colonies consisting of >50 cells were enumerated on a stereo microscope (Nikon). The results are presented as the total CFU-GMs per spleen ± SD after multiplying CFU frequency by the total number of nucleated splenocytes.

Flow Cytometric Analysis.

Three-color flow cytometric analysis of cell suspensions was performed by using the following mAbs: PE-anti-CD25 mAb (7D4) purchased from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA); FITC-anti-Foxp3 (eBioscience, San Diego); and FITC-CD3, PE-CD8, PE-DX5, and PerCP-anti-CD4 (Pharmingen). Nonspecific binding was corrected with isotype-matched controls. Cell staining was prepared as described (24) and analyzed on a FACScan with cellquest software (Becton Dickinson).

Adoptive Transfer of CD4+CD25+ Treg Cells and Sublethal BMT.

One day before transplantation, CB6F1 recipients were conditioned with a sublethal 7.0-Gy dose of TBI (60Co, 44.5 cGy/min). BMCs obtained from flushing of femurs and tibias were resuspended at a concentration of 2.5 × 107 cells per ml, incubated for 30 min with anti-Th1.2 mAb (H0-13-4) at 4°C (for 30 min), washed, and incubated at 37°C for 30 min in the presence of complement (Rabbit Low Tox-M; Cedarlane Laboratories). Cells were washed before i.v. injection alone or together with B6 CD4+CD25+ T cells.

CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from spleen and lymph nodes of B6 CD8−/− mice were obtained as described above. B6-GFP T cell-depleted BMCs were injected i.v. alone or together with B6 CD4+CD25+ T cells, and, 6 days after BMT, the level of BMC engraftment was determined by measuring CFU-GM content in the spleen and by flow cytometry (FACScan) as described (26, 34). The results are presented as the average total CFU-GMs per spleen ± SD after multiplying CFU frequency by the total number of nucleated splenocytes.

Statistical Analysis.

ANOVAs (one- and two-way) were used to determine statistically significant differences between more than two experimental groups. Unpaired Student t tests were used to determine statistically significant differences between two experimental groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ruth Gault for assistance with the manuscript; Kory Alderson for help with flow cytometry; and Weihong Ma, Myra Godfrey, and Danice Wilkins for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-CA93527, R01-HL63452, R01-AI34495, 2R37-HL56067, RR11576, AI-46689, T32-CA09563, and P20-RR016464 and American Cancer Society Grant RSG-020169.

Abbreviations

- BM

bone marrow

- BMC

BM cell

- BMT

BM transplantation

- CFU-GM

colony-forming unit–granulocyte/monocyte

- Treg

T regulatory

- NK

natural killer

- poly(I:C)

polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- TBI

total body irradiation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

S.S. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

References

- 1.Trinchieri G. Adv. Immunol. 1989;47:187–376. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60664-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biron C. A., Nguyen K. B., Pien G. C., Cousens L. P., Salazar-Mather T. P. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1999;17:189–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy W. J., Kumar V., Bennett M. J. Exp. Med. 1987;165:1212–1217. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.4.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy W. J., Kumar V., Cope J. C., Bennett M. J. Immunol. 1990;144:3305–3311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cudkowicz G., Bennett M. J. Exp. Med. 1971;134:1513–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy W. J., Keller J. R., Harrison C. L., Young H. A., Longo D. L. Blood. 1992;80:670–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dredge K., Marriott J. B., Todryk S. M., Dalgleish A. G. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2002;51:521–531. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trinchieri G., Wysocka M., D'Andrea A., Rengaraju M., Aste-Amezaga M., Kubin M., Valiante N. M., Chehimi J. Prog. Growth Factor Res. 1992;4:355–368. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(92)90016-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerosa F., Baldani-Guerra B., Nisii C., Marchesini V., Carra G., Trinchieri G. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:327–333. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geldhof A. B., Van Ginderachter J. A., Liu Y., Noel W., Raes G., De Baetselier P. Blood. 2002;100:4049–4058. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly J. M., Darcy P. K., Markby J. L., Godfrey D. I., Takeda K., Yagita H., Smyth M. J. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:83–90. doi: 10.1038/ni746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shevach E. M. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:423–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annacker O., Pimenta-Araujo R., Burlen-Defranoux O., Barbosa T. C., Cumano A., Bandeira A. J. Immunol. 2001;166:3008–3018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingsley C. I., Karim M., Bushell A. R., Wood K. J. J. Immunol. 2002;168:1080–1086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor P. A., Lees C. J., Blazar B. R. Blood. 2002;99:3493–3499. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann P., Ermann J., Edinger M., Fathman C. G., Strober S. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:389–399. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N., Asano M., Itoh M., Toda M. J. Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi T., Tagami T., Yamazaki S., Uede T., Shimizu J., Sakaguchi N., Mak T. W., Sakaguchi S. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:303–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hori S., Nomura T., Sakaguchi S. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tai A., Burton R. C., Warner N. L. J. Immunol. 1980;124:1705–1711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds C. W., Timonen T. T., Holden H. T., Hansen C. T., Herberman R. B. Eur. J. Immunol. 1982;12:577–582. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830120709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zelenay S., Lopes-Carvalho T., Caramalho I., Moraes-Fontes M. F., Rebelo M., Demengeot J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:4091–4096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408679102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davenport C., Kumar V., Bennett M. J. Immunol. 1995;155:3742–3749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raziuddin A., Longo D. L., Bennett M., Winkler-Pickett R., Ortaldo J. R., Murphy W. J. Blood. 2002;100:3026–3033. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.8.3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fahlen L., Lendahl U., Sentman C. L. J. Immunol. 2001;166:6585–6592. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koh C. Y., Welniak L. A., Murphy W. J. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura K., Kitani A., Strober W. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:629–644. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levings M. K., Sangregorio R., Sartirana C., Moschin A. L., Battaglia M., Orban P. C., Roncarolo M. G. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:1335–1346. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellone G., Aste-Amezaga M., Trinchieri G., Rodeck U. J. Immunol. 1995;155:1066–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghiringhelli F., Menard C., Terme M., Flament C., Taieb J., Chaput N., Puig P. E., Novault S., Escudier B., Vivier E., et al. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1075–1085. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arteaga C. L., Hurd S. D., Winnier A. R., Johnson M. D., Fendly B. M., Forbes J. T. J. Clin. Invest. 1993;92:2569–2576. doi: 10.1172/JCI116871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su H. C., Leite-Morris K. A., Braun L., Biron C. A. J. Immunol. 1991;147:2717–2727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallick S. C., Figari I. S., Morris R. E., Levinson A. D., Palladino M. A. J. Exp. Med. 1990;172:1777–1784. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanash A. M., Levy R. B. Blood. 2005;105:1828–1836. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asai O., Longo D. L., Tian Z. G., Hornung R. L., Taub D. D., Ruscetti F. W., Murphy W. J. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1835–1842. doi: 10.1172/JCI1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uberti J., Martilotti F., Chou T. H., Kaplan J. Blood. 1992;79:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piccirillo C. A., Shevach E. M. J. Immunol. 2001;167:1137–1140. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azuma T., Takahashi T., Kunisato A., Kitamura T., Hirai H. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4516–4520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taams L. S., van Amelsfort J. M., Tiemessen M. M., Jacobs K. M., de Jong E. C., Akbar A. N., Bijlsma J. W., Lafeber F. P. Hum. Immunol. 2005;66:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzue K., Reinherz E. L., Koyasu S. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:3147–3152. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3147::aid-immu3147>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thornton A. M., Shevach E. M. J. Exp. Med. 1998;188:287–296. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Smedt T., Van Mechelen M., De Becker G., Urbain J., Leo O., Moser M. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997;27:1229–1235. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogasawara K., Benjamin J., Takaki R., Phillips J. H., Lanier L. L. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:938–945. doi: 10.1038/ni1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee J. C., Lee K. M., Kim D. W., Heo D. S. J. Immunol. 2004;172:7335–7340. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smyth M. J., Teng M. W., Swann J., Kyparissoudis K., Godfrey D. I., Hayakawa Y. J. Immunol. 2006;176:1582–1587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]