Abstract

The determination of functional antipneumococcal capsular polysaccharide antibodies by sequential testing of pre- and postvaccination serum samples one serotype at a time is sample-intensive and time-consuming and has a relatively low throughput. We tested several opsonophagocytic assay (OPA) formats, including the reference killing method, a monovalent bacterium-based flow method, a trivalent bacterium-based flow method, and a tetravalent bead-based flow method using a panel of sera (4 prevaccination and 16 postvaccination, from healthy adults immunized with the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine). The trivalent and tetravalent methods allow simultaneous measurements of opsonic antibodies to multiple pneumococcal serotypes. The trivalent bacterial-flow OPA had significant correlation to the reference OPA method and to a previously published flow cytometric OPA (r values ranged from 0.61 to 0.91, P < 0.05) for serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F. The tetravalent OPA had significant correlation to all OPA method formats tested (r values from 0.68 to 0.92, P < 0.05) for all seven serotypes tested. This tetravalent OPA is an alternative to other OPA methods for use during vaccine evaluation and clinical trials. Further, the flow cytometric multiplex OPA format has the potential for expansion beyond the current four serotypes to eight or more serotypes, which would further increase relative sample throughput while reducing reagent and sample volumes used.

Streptococcus pneumoniae remains one of the most significant causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide (5, 6, 21). Host immunity to pneumococci is mediated by both innate and adaptive immunity, including opsonizing antibodies, complement, and phagocytic effector cells (4, 7, 20). Measurement of total binding antibodies through an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) may not reflect the true level of opsonic or “functional” antibodies, as the measurement of total binding antibodies includes both functional and nonfunctional antibodies (15, 18, 19). Phagocytosis of pneumococci elicited by functional antibodies is thought to be a representative measure of the potential protective efficacy of pneumococcal vaccines (7, 10). Laboratory correlates of protection, such as opsonophagocytic assays (OPAs), are used to measure the functional antibodies elicited by pneumococcal vaccines (10). The currently available assays for measurement of pneumococcal opsonic antibodies can assess from one to seven serotypes at a time (3, 9, 10, 12, 14, 17). Most of these methods require the use of infectious organisms and overnight incubation to allow colony growth and measure killing of opsonized bacteria by phagocytic cells.

With the licensure of a seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, “non-inferiority” of newer formulations compared to the existing licensed formulation will need to be established before new products are licensed (10). Therefore, the new multiserotype conjugate vaccines (seven or more serotypes) for S. pneumoniae have resulted in an additional logistical problem, i.e., the need for evaluation of the functional, immune response to each capsular polysaccharide (PS) serotype included in the vaccine. Each vaccine polysaccharide component needs to be individually assessed for immunogenicity.

Since the OPA has been recognized as a correlate of protection for the evaluation of functional antibody activity, many efforts have been made to facilitate the use of this type of assay. Two major formats exist for opsonization assays: killing and uptake. Killing assays are variations of the accepted reference assay developed by Romero-Steiner et al. (16, 17). The recent multiplex killing assays (3, 11, 14) make use of antibiotic-resistant strains of target bacteria to allow differentiation of killing for each specific pneumococcal serotype. Uptake opsonization assays measure the uptake of opsonized fluorescent targets, either bacteria (10, 12) or polysaccharide-conjugated beads (12). The uptake assays measure the opsonization of specific targets and their subsequent internalization by phagocytic cells. The uptake assays do not measure killing directly; however, they have been shown to measure all processes leading up to bacterial killing within the phagosome (1, 2), such as antibody binding, complement fixation, cellular attachment through Fc and complement receptors, internalization, and activation of the respiratory burst.

Existing OPA single-serotype functional testing is time-consuming, expensive, and requires significant amounts of serum, primarily due to the sequential nature (one serotype at a time) of this testing. The newer multiplex OPAs based on bacterial killing still require a significant amount of time due to the overnight growth requirement of bacterial colonies and the need for colony counting. While these assays are clearly an improvement over singleplex killing assays, these assay require two days rather than one day for obtaining results.

Development of a multiplex functional OPA that would provide significant reduction in time could encourage more investigators to measure functional antibodies by OPA instead of measuring both functional and nonfunctional antibodies by ELISA. We have developed a multiplex OPA based on uptake of opsonized targets (fluorescently labeled bacteria or polysaccharide-conjugated fluorescent beads). We compared the previously published reference OPA method (17) to a previously published single-bacterium uptake flow OPA (13) and to two new uptake-based multiplex OPAs: a trivalent bacterial OPA and a tetravalent bead OPA. We demonstrate that there is a good correlation between all OPA formats tested, both killing and uptake.

(Part of this study was presented at the 3rd International Symposium on Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases, Anchorage, Alaska, 2001.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reference OPA method.

The reference method was performed as previously published (17).

Preparation of fluorescently labeled bacteria.

S. pneumoniae serotypes 1, 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F were grown as previously described for the single-color-bacterium-based opsonophagocytic assay (13). The bacterium-staining protocol was modified to use 1.25 mg/ml (5,6)-carboxytetramethylrhodamine, succinimidyl ester, (5,6)-TAMRA (6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine), succinimidyl ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), or 0.25 mg/ml Texas Red-X-succinimidyl ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) as an alternative to the 10 mg/ml 5,6 carboxyfluorescein used in the original protocol. Protocol staining times and fixation of bacteria were performed as previously published (13).

Polysaccharide-conjugated polystyrene beads.

Polystyrene beads, 1 to 1.4 μm in diameter, of four different fluorescence wavelengths, (yellow, 488/530 nm [excitation/emission]; pink, 488/585 nm; red, 488/>600 nm; blue, 635/>670 nm [provided by Flow Applications, Okawville, Ill.]) were conjugated with Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular PS serotype 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, or 23F (ATCC, Manassas, Va.). The PS-conjugated beads were provided to CDC by Flow Applications, Inc. (Okawville, Ill.), under an unrestricted cooperative research agreement. The conjugated beads are now commercially available.

For the bead-based multiplex OPA, the beads were divided into groups, each with four fluorescent-bead populations. Group 1 contained serotype 14-yellow (Y), serotype 9V-pink (P), serotype 6B-red (R), and serotype 4-blue (B). Group 2 contained: serotype 14-Y, serotype 18C-P, serotype 19F-R and serotype 23F-B. The two groups together allowed testing of opsonic antibodies directed against serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F. Serotype 14 was duplicated in each bead set as an internal control measurement.

Each set of beads was diluted by adding a predetermined volume of each serotype bead population and the resulting suspension was brought up to 2 ml using OPA buffer (Hanks buffered saline with Ca2+ and Mg2+ [Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.], with 0.2% bovine serum albumin [Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.]). This working bead suspension delivered a final concentration of 1 × 105 beads for each serotype bead in 20 μl OPA buffer. Four serotypes (4, 6B, 9V, and 14 or 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F) were assayed simultaneously on one single plate using 20 μl of working bead suspension per well.

HL60 polymorphonuclear leukocyte induction.

Growth, maintenance, and induction of HL-60 cells were carried out as previously described (13). HL60 cells were harvested at 5 days postinduction as previously described and resuspended at 2.5 × 106 cells per 3 ml using OPA buffer. This cell density provides sufficient cells for one plate when added at a volume of 30 μl per well.

Complement source.

Frozen serum from 3 to 4 week old rabbits was obtained from Pel Freeze (Brown Deer, Wis.). The frozen serum was thawed at 4°C and aliquoted in 1-ml volumes. These aliquots were snap-frozen using dry ice and ethanol and stored at −70°C until use.

Donor sera.

Twenty international quality control sera from adults immunized with the 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (4 prevaccination and 16 postvaccination) were obtained from the National Institute for Biological Standards and Control, United Kingdom.

ELISA.

The 20 international quality control sera were tested using the WHO standard ELISA (19). Immunoglobulin G concentrations for serotypes 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F were obtained.

OPAs.

Eight twofold dilutions were made in OPA buffer from 10 μl of test serum as previously reported (13). A 20-μl aliquot of either multiplex bacteria or multiplex bead suspension containing 1 × 105 of each of the target pneumococcal serotype or pneumococcal polysaccharide-conjugated beads was added to each well, and the plate incubated for one hour at 37°C with horizontal shaking (200 rpm). Following this, 20 μl of sterile serum from 3- to 4-week-old baby rabbit serum (Pel-Freez, Brown Deer, Wis.) was added to each well except for HL60 cell control wells, which received 20 μl of OPA buffer. After incubation at 37°C for 20 min with shaking (200 rpm on an orbital shaker), 30 μl of washed HL60 polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) (2.5 × 104/ml) were added to each well, resulting in an effector-to-target ratio of 1:4 (for each target type). The final well volume was 80 μl, with the first well of a dilution series containing a 1:8 final dilution. The plate was then incubated for 60 min with shaking at 37°C. An additional 80 μl of OPA buffer was added to every well to provide sufficient volume for flow cytometric analysis and the well contents transferred to microtiter tubes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Up to 12 serum samples could be assayed per plate, including a quality control sample.

Samples were assayed with a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) suitably compensated for simultaneous differentiation of all four bead colors: yellow (530 nm), pink (585 nm), red (>600 nm), and blue (>670 nm). The fluorescent dyes for the bead populations were chosen to be read using a standard filter set and do not require any modification of the cytometer. However, the ease of compensation can be improved by installation of band pass filters more closely matching bead fluorescent signals. The data were analyzed using Cell Quest software (Becton Dickinson) and OPA antibody titers determined. The OPA analysis was done on all samples for serogroups 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F using Becton-Dickinson FACSCalibur cytometer (with standard filters). The acquisition protocol on the cytometer was modified to acquire data from four different wavelength emissions.

Pearson's product moment correlation coefficient and the Mann-Whitney rank sum test were used for statistical analysis of the data, with significance set at P < 0.05. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was also performed to determine statistical differences in the median values of the treatment groups. The Sigma Stat software program, version 3.1 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, Calif.), was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

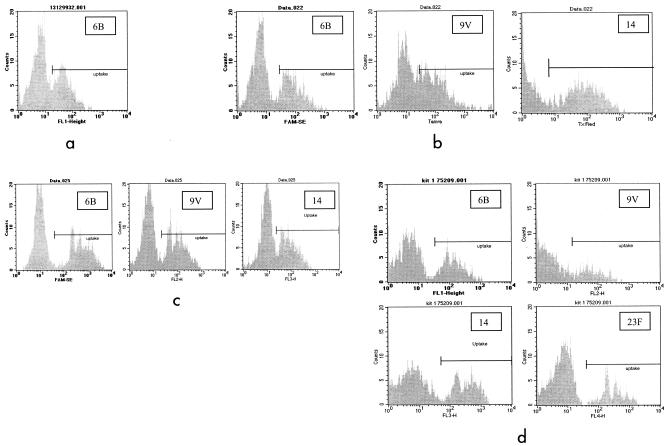

The flow cytometric OPAs measure the change in fluorescence observed as effector cells phagocytose fluorescently labeled targets (percent of effector cells with fluorescent target uptake). As we previously reported (13), the reciprocal dilution at which 50% of maximal uptake for a given sample can be reported as the titer for antibody reacting to a serotype-specific polysaccharide. Thus, the quality of the fluorescent histograms is critical in the determination of OPA titers. Figure 1 illustrates fluorescence histograms (sample dilution, 1/8) obtained from four flow OPAs (the monovalent bacterium-based OPA, the trivalent bacterium-based OPA, the trivalent bead-based OPA, and the tetravalent bead-based OPA). These histogram examples show that the assays are capable of detecting the uptake of a single serotype or several (four) serotypes by measurement of specific fluorescent emissions from HL60 PMNs with phagocytosed fluorescent targets in a single reaction. It should be noted from these examples that HL60 PMNs with ingested fluorescent-bead targets are more clearly distinguished from HL60 PMNs without ingested fluorescent targets, making titer determination more easily standardized than the bacterium-based assay. Figure 3 shows representative uptake plots for both the trivalent and tetravalent OPAs.

FIG. 1.

This figure contains representative histograms showing fluorescent uptakes obtained from the monovalent bacterium-based (a), trivalent bacterium-based (b), trivalent bead-based (c), and tetravalent bead-based (d) OPAs. All histograms shown are from the 1/8 dilution well of each assay. The marker regions used to determine percent cells with uptake is determined by using the complement control (not shown). The marker region is set for each serotype being tested (i.e., each fluorescent channel) such that 2% or less of the cells in the negative (nonfluorescent) cell population are included in the marker region.

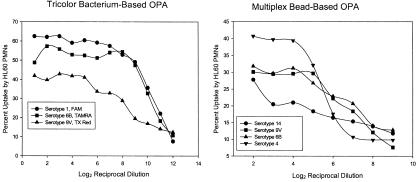

FIG. 3.

These graphs show sample uptake curves obtained using either the trivalent bacterium-based OPA or the tetravalent bead-based OPA.

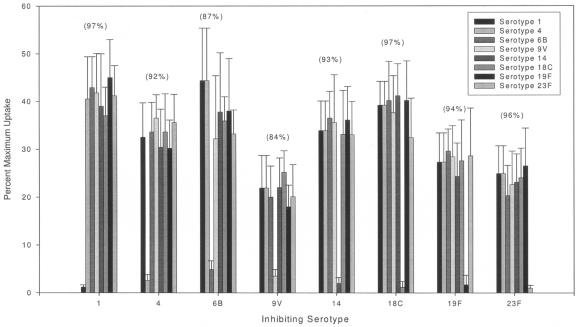

The potential effects of nonspecific antipneumococcal antibodies, antibodies against pneumococcal proteins or capsular polysaccharide for example, on the observed OPA titers were studied. The effects of nonspecific antipneumococcal antibodies would of course be more critical in OPAs in which multiplex serotypes are assessed. Figure 2 is representative of the effects on percent maximum uptakes with serum preabsorbed with type-specific polysaccharides. Five postvaccination high-titer sera were preabsorbed with each pneumococcal polysaccharide (serotype 1, 4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, or 23F) to a final concentration of 500 μg per ml as previously published (13). The absorbed sera were tested in the trivalent bacterium-based OPA, and the average percent uptake for the 1:16 dilutions are shown. As can be seen, there is significant inhibition of uptake in the presence of type-specific polysaccharide and minimal effect on uptake of non-type-specific fluorescent bacteria (Fig. 2). These data supported the feasibility of the multiplex OPA format and the capacity for the evaluation of OPA titers for multiple serotypes in a single reaction mixture.

FIG. 2.

Effects of type-specific and non-type-specific polysaccharide on multiplex OPA uptakes. This graph shows the inhibition of percent maximum uptake in the presence of type-specific pneumococcal polysaccharide and the lack of inhibition on heterologous polysaccharide bead types. As is shown, the resulting inhibition is specific, i.e., significantly inhibiting the uptake of the specific-polysaccharide-conjugated beads and not significantly reducing uptake of heterologous polysaccharide beads in the same reaction well. This result showed that multiplex OPAs were possible.

One important criterion for proving the value of any new assay is the demonstration that the new assay yields results similar to those obtained by the reference method (17). As part of the multiplex assay development plan, we compared four OPA methods: the reference method (17) and three flow OP assays (the monovalent bacterial OPA [13], the trivalent bacterial OPA, and the tetravalent bead OPA). Our results show significant correlations between all the flow cytometry-based OPAs and the reference OPA method (Table 1) with the exception of serotype 9V and 14 in the reference and monovalent OPAs. Different strains of 9V and 14 were used in the reference and monovalent OPAs. Further, Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA showed that the differences in the median values among the treatment groups (manual OPA, monovalent bacterial OPA, and tetravalent bead OPA) are not statistically different (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Correlation of reference OPA, monovalent bacterial flow OPA, trivalent bacterial flow OPA, and the tetravalent bead-based flow OPAa

| Serotype |

r value (P value)

|

P value for Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA for manual OPA vs. monovalent OPA vs. tetravalent OPA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference OPA vs. monovalent OPA | Reference OPA vs. trivalent bacterial OPA | Reference OPA vs. tetravalent OPA | Monovalent OPA vs. trivalent OPA | Monovalent OPA vs. tetravalent OPA | ||

| 4 | 0.88 (<0.001) | 0.61 (0.04) | 0.86 (<0.001) | 0.80 (0.002) | 0.85 (<0.001) | 0.48 |

| 6B | 0.77 (0.003) | 0.87 (<0.001) | 0.88 (<0.001) | 0.86 (<0.001) | 0.77 (<0.001) | 0.74 |

| 9V | 0.53 (0.08) | 0.79 (0.006) | 0.80 (<0.001) | 0.73 (0.008) | 0.88 (0.002) | 0.21 |

| 14 | 0.54 (0.04) | 0.75 (0.005) | 0.85 (<0.001) | 0.63 (0.03) | 0.92 (<0.001) | 0.07 |

| 18C | 0.77 (0.003) | 0.91 (<0.001) | 0.71 (<0.001) | 0.74 (0.005) | 0.92 (<0.001) | 0.58 |

| 19F | 0.95 (<0.001) | 0.91 (<0.001) | 0.68 (0.01) | 0.91 (<0.001) | 0.87 (<0.001) | 0.54 |

| 23F | 0.83 (<0.001) | 0.78 (0.003) | 0.68 (<0.001) | 0.88 (<0.001) | 0.88 (<0.001) | 0.76 |

This table shows the correlations obtained by comparing titers obtained on the serum panel tested by the reference killing OPA, the monovalent bacterium-based flow OPA, the trivalent bacterium-based OPA, and the tetravalent bead-based flow OPA. As can be seen, the various OPAs correlate well, with the exception of serotypes 9V and 14 when the reference OPA was compared to the monovalent OPA. The serotype 9V and 14 strains used in the manual and monovalent OPAs differed. These two strains used in the reference OPA demonstrated significant background activity in the complement control making them unsuitable for use in the monovalent flow OPA. The strains selected for the monovalent OPA demonstrated a bias towards higher titers in the bacterium-based flow OPAs.

The monovalent bacterial OPA and the reference method (17) had an r ranging from a low of 0.53 for 9V to a high of 0.95 for serotype 19F (Table 1). These values compare well to a previously published comparison of these two OPAs (13). We then compared the reference OPA to the trivalent bacterial OPA in order to introduce the multiplex OPA format. As is shown in Table 1, we obtained good correlations with the trivalent bacterial OPA to the reference method with improvement of the correlations for serotypes 9V and 14 (r from 0.53 and 0.54 to r = 0.79 and 0.75 for serotypes 9V and 14, respectively). Comparison of the tetravalent bead OPA and the reference OPA yielded similar results, with a low r of 0.68 for serotypes 19F and 23F to a high of 0.88 for serotype 6B. We obtained very similar correlations between these three flow OP assays as shown in Table 1.

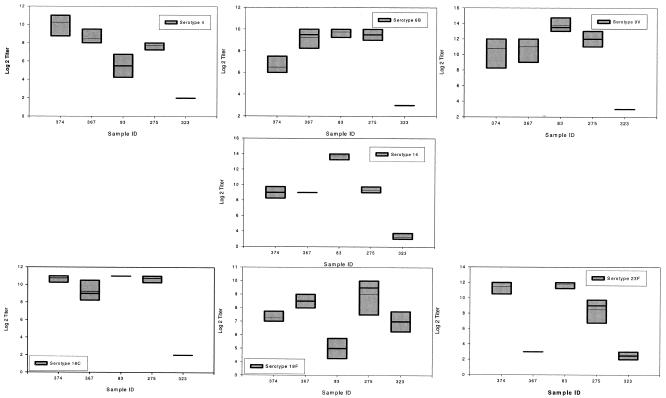

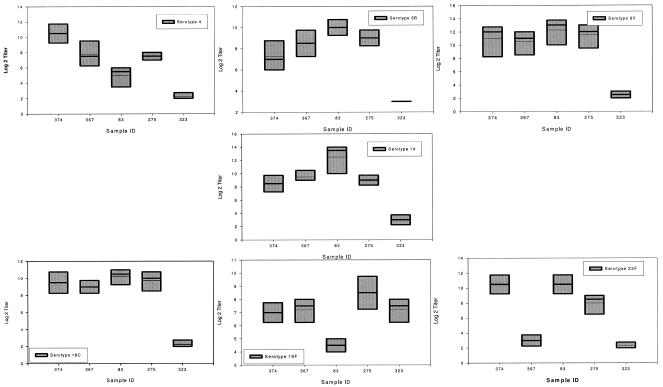

The data in Table 2 show that the tetravalent bead OPA has a good qualitative comparison with the reference assay, with 94% of samples within 2 dilutions of the expected median titer. There was a bias towards increased titers noted for samples with a >1-dilution difference from the reference method. We also compared the reference OPA and the tetravalent bead flow OPA with ELISA concentrations. The reproducibility of the trivalent and tetravalent OPA is shown in Fig. 4 and 5, respectively. As can be seen, both assays are reproducible, with the majority of titers within ±1 titer. The multiplex assay also correlates well with ELISA values obtained with the WHO reference ELISA (Table 3) (19).

TABLE 2.

Qualitative differences between expected manual titers and observed titers from the tetravalent bead-based OPA

| Serotype | % of sera differing from expected reference OPA titer (by no. of dilutions)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| ±1 | ±2 | ±4 | |

| 4 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 6B | 90 | 5 | 5 |

| 9V | 85 | 5 | 10 |

| 14b | |||

| Group 1 | 90 | 10 | 0 |

| Group 2 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 18C | 95 | 5 | 0 |

| 19F | 75 | 5 | 20 |

| 23F | 85 | 5 | 10 |

| Mean | 90 | 4.4 | 5.6 |

This table provides data on the difference between the expected titers, as measured by the reference OPA, and the titers obtained from the tetravalent OPA. As can seen in the data, the majority of samples for all serotypes tested were within 1 dilution of the target titer.

Serotype 14 was incorporated in each tetravalent bead kit. Group 1 included serotype 4, 6B, 9V, and 14 beads. Group 2 included serotype 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F beads.

FIG. 4.

Reproducibility of the trivalent bacterium-based OPA. This figure shows the variability of five samples tested using the trivalent OPA on four different days. Data on seven serotypes (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F) are shown. The top and bottom levels of each box represent the 5 and 95 percent confidence intervals. The bold line within a box (when present) is the median titer. The thin line in the box is the mean titer obtained.

FIG. 5.

Reproducibility of the tetravalent bead-based OPA. This figure shows the variability of five samples tested using the trivalent OPA on four different days. Data on seven serotypes (4, 6B, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F) are shown. The top and bottom levels of each box represent the 5 and 95 percent confidence intervals. The bold line within a box (when present) is the median titer. The thin line in the box is the mean titer obtained.

TABLE 3.

Correlation of ELISA concentrations and OPA titersa

| Serotype | 22F absorbed ELISA immunoglobulin G concn vs. that of:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Multiplexed bead OPA | Reference OPA | |

| 4 | 0.63 | 0.49 |

| 6B | 0.56 | 0.55 |

| 9V | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| 14 | ||

| Group 1 | 0.93 | 0.72 |

| Group 2 | 0.91 | 0.72 |

| 18C | 0.57 | 0.42 |

| 19F | 0.41 | 0.82 |

| 23F | 0.82 | 0.72 |

This table lists the correlation values for OPA titers obtained by either the tetravalent bead OPA or the reference OPA against 22F absorbed ELISA immunoglobulin G concentrations. The assays yielded similar results, with the tetravalent bead OPA having slightly higher correlations for all serotypes except serotype 19F.

DISCUSSION

We previously showed that a single-color flow cytometric OPA for pneumococci (13) was possible and comparable to the reference method (17). At that time, we proposed the development of a multiplex OPA. We modified the single-color flow OPA to use a mixture of pneumococci labeled with carboxyfluorescein, tetramethylrhodamine, or Texas Red in an initial multiplex format. The trivalent bacterial OPA correlated well with the reference method. The trivalent bacterial OPA provided the first proof of principle for further development of a multiplex uptake OPA with percent uptake as the measurement parameter used for titer determination.

The trivalent bacterial OPA demonstrated that it was possible to measure functional (opsonic) antibodies with specificities to different pneumococcal polysaccharides simultaneously within a single-assay system. In this study, we have shown that the presence of multiple bacterial serotypes within a sample do not interfere with each other and that observed uptake of each bacterial serotype by the effector cells is independent of uptakes of the other bacterial serotypes present. We also show that specific polysaccharide added to the assay system inhibits the uptake of the corresponding target bacteria without adversely affecting the uptake of the different polysaccharide targets present. These inhibition studies show that these OPAs are measuring functional antibodies to each specific polysaccharide-conjugated target.

Our data show that the titers obtained from the trivalent bacterial OPA correlate well with those of the reference OPA method (17) and the previously published monovalent OPA method (13). We have demonstrated that a multiplex uptake-based flow OPA was possible without interference among different antigenic targets. Whereas ELISA requires preabsorption of sera with capsular polysaccharide and 22F to remove nonspecific antibody interference, the OPA methods do not require this preabsorption step. The multiplex nature of the assay serves to reduce any contributions made by nonspecific antibodies to any single opsonic titer observed in the assay.

While the trivalent bacterial OPA correlated well with the reference OPA method and the single-color flow OPA, the process of labeling the bacteria is difficult to standardize due to differences in lot-to-lot growth of the bacteria, strain-to-strain bacterial differences, staining variability, and variability in capsule production in culture (the assay requires highly encapsulated bacteria). These difficulties can result in increased backgrounds levels (cell and complement controls) due to variability in the encapsulation of individual bacteria and to variable exposure of common pneumococcal cell wall components and/or capsular proteins which may cross-react with antibodies in the specimen or the complement source itself (8, 15). The variability in bacterial staining also contributes to the variability in percent uptake when low levels of fluorescent label result in insufficient separation of phagocytosing and nonphagocytosing cells (low signal-to-noise ratio). Variability in bacterial staining also contributes to difficulty in flow cytometric compensation of crossover signals between the various fluorescent dyes.

These technical difficulties with bacterial fluorescent labeling suggested that an alternative target should be used. We evaluated fluorescently labeled polystyrene beads conjugated to pneumococcal polysaccharides as alternative targets. The use of polysaccharide-conjugated beads allowed us to control for the amount of polysaccharide present, reduce the possibility of nonspecific antibody binding (the use of vaccine-grade polysaccharide to conjugate the beads reduces the amount of nonspecific antigenic targets present), control the amount of fluorescent label per target, and more accurately control the level of target fluorescence, allowing more reproducible instrument compensation. The use of fluorescent beads as OPA targets was the next step in the evolution of the multiplex OPA and led to testing of a trivalent bead-based OPA (data not shown).

There were several concerns with the concept of an artificial OPA target. First was the concern whether the conjugation protocol would affect the pneumococcal polysaccharide in an adverse way, for example, whether the conjugation process might destroy antigenic sites within the pneumococcal polysaccharide, thereby reducing its reactivity and thus reducing OPA titers obtained. Our data in Table 1 show this not to be the case, as results from a panel of sera previously assayed by both the reference method and the single-color bacterium-based OPA compared well with results obtained by the tetravalent bead OPA.

A second concern was that a multiplex OPA might not be possible or that nonspecific antibodies present might interfere with a multiplex assay. This also proved not to be the case. The trivalent bacterium-based OPA correlated well with both the reference OPA and the monovalent flow OPA. We demonstrated few or no effects from nonspecific antibodies.

We have shown no significant titer differences observed between the four different OPAs (the reference OPA, the monovalent flow OPA, the trivalent bacterial OPA, and the tetravalent flow OPA) evaluated. This is not surprising since all the opsonophagocytic assays, both killing and uptake based, share the same biological processes: opsonization of a particle (whether bacterium or bead) with antibody and complement, attachment to cells through Fc and complement receptors, and internalization by the phagocytic cells.

In this study, we have introduced the concept of a multiplex uptake pneumococcal OPA. The tetravalent OPA forms the primary method evaluated. This patented multiplex uptake bead OPA utilizes four different-colored beads conjugated to a total of seven different pneumococcal polysaccharides. A combination of different fluorescent, colored beads was used to determine the titers of opsonophagocytic antibodies against four different pneumococcal serotypes simultaneously in a single assay. We believe that the tetravalent OPA represents an improvement over the reference method. The tetravalent OPA has a higher net serotype throughput; it uses one-quarter the serum per serotype answer and reduces reagent usage by three-quarters. Others have demonstrated that the tetravalent OPA was capable of an average of 2.9 min per serotype answer when data were collected on a Becton Dickinson LSR system without automated sample acquisition (Carl Frasch, FDA, Bethesda, Md., personal communication). These throughputs were impressive and resulted in the collection of data for up to four serotypes on 38 samples in an eight-hour period. The tetravalent uptake OPA reduced the overall time required for testing, allowing quadruple the number of serotype answers to be performed in a single work day. The reference killing OPA and multiplex killing OPA require overnight incubations prior to reading of the bacterial plates.

The tetravalent OPA compared well with the reference method, making it a useful adjunct to pneumococcal laboratory correlates of protection. The multiplex uptake OPAs do not require the use of live infectious agents, greatly reducing the hazards to laboratory workers and thus reducing the potential liability to employers. The multiplex OPAs also have the potential to be modified to assay at least eight serotypes in a single assay using a standard cytometer, and work is currently under way to attain this. Further, the multiplex OPAs can be modified to increase assay automation by use of autoloaders or plate loaders, by use of batch analysis of flow data files to extract uptake data, and by use of curve-fitting software to automate the titer determination process. All of these automation improvements can significantly reduce the time required to obtain a result.

Acknowledgments

The data presented in this publication represent unbiased research and do not represent an endorsement of any product.

The work was partly supported by Flow Applications, Inc., Okawville, Ill., through an unrestricted cooperative research agreement which resulted in U.S. patent number 6,815,172.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali, F., M. E. Lee, F. Iannelli, G. Pozzi, T. J. Mitchell, R. C. Read, and D. H. Dockrell. 2003. Streptococcus pneumoniae-associated human macrophage apoptosis after bacterial internalization via complement and Fcγ receptors correlates with intracellular bacterial load. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1119-1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassoe, C. F., I. Smith, S. Sornes, A. Halstensen, and A. K. Lehman. 2000. Concurrent measurement of antigen- and antibody-dependent oxidative burst and phagocytosis in monocytes and neutrophils. Methods 21:203-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogaert, D., M. Sluijter, R. de Groot, and P. W. M. Hermans. 2004. Multiplexed opsonophagocytosis assay (MOPA): a useful tool for the monitoring of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Vaccine 22:4014-4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casal, J., and Tarrago, D. 2003. Immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae: factors affecting production and efficacy. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 16:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1997. Prevention of pneumococcal disease: recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 46(RR-8):1-24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1989. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 38:64-68, 73-76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guckian, J. C., G. D. Christensen, and D. P. Fine. 2000. The role of opsonins in recovery from experimental pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 142:175-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu, B. T., X. Yu, T. R. Jones, C. Kirch, S. Harris, S. W. Hildreth, D. V. Madore, and S. A. Quataert. 2005. Approach to validating an opsonophagocytic assay for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 12:287-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen, W. T. M., J. Gootjes, M. Zelle, D. V. Madore, J. Verhoef, H. Snippe, and A. F. M. Verheul. 1998. Use of highly encapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae strains in a flow-cytometry assay for assessment of the phagocytic capacity of serotype specific antibodies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 5:703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jodar, L., J. Butler, G. Carlone, R. Dagan, D. Goldblatt, H. Kayhty, K. Klugman, B. Plikaytis, G. Siber, R. Kohberger, I. Chang, and T. Cherian. 2003. Serological criteria for evaluation and licensure of new pneumococcal conjugate vaccine formulations for use in infants. Vaccine 21:3265-3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, K. H., J. Yu, and M. H. Nahm. 2003. Efficiency of a pneumococcal opsonophagocytic killing assay improved by multiplexing and by coloring colonies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:616-621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez, J., T. Pilishvili, S. Barnard, J. Caba, W. Spear, S. Romero-Steiner, and G. M. Carlone. 2002. Opsonophagocytosis of fluorescent polystyrene beads coupled to Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A, C, Y, or W135 polysaccharide correlates with serum bactericidal activity. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 9:485-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinez, J. E., S. Romero-Steiner, T. Pilishvili, S. Barnard, J. Schinsky, D. Goldblatt, and G. M. Carlone. 1999. A flow cytometric opsonophagocytic assay for measurement of functional antibodies elicited after vaccination with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 6:581-586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nahm, M. H., D. E. Brile, and X. Yu. 2000. Development of a multi-specificity opsonophagocytic killing assay. Vaccine 18:2768-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nahm, M. H., J. V. Olander, and M. Magyarlaki. 1997. Identification of cross-reactive antibodies with low opsonophagocytic activity for Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Infect. Dis. 176:698-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero-Steiner, S., C. Frasch, N. Concepcion, D. Goldblatt, H. Kayhty, M. Vakevainen, C. Laferriere, D. Wauters, M. Nahm, M. F. Schinsky, and B. D. Plikaytis. 2003. Multilaboratory evaluation of a viability assay for measurement of opsonophagocytic antibodies specific to the capsular polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:1019-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero-Steiner, S., D. LiButti, L. B. Pais, J. Dykes, P. Anderson, J. C. Whitin, H. L. Keyserling, and G. M. Carlone. 1997. Standardization of an opsonophagocytic assay for the measurement of the functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae using differentiated HL-60 cells. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:415-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romero-Steiner, S., D. M. Musher, M. S. Cetron, L. B. Pais, J. E. Groover, A. E. Fiore, B. D. Plikaytis, and G. M. Carlone. 1999. Reduction in functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae in vaccinated elderly individuals highly correlates with decreased IgG antibody avidity. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29:281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wernette, C. M., C. M. Frasch, D. Madore, G. Carlone, D. Goldblatt, B. Plikaytis, W. Benjamin, S. A. Quataet, S. Hildreath, D. J. Sikkema, H. Kayhty, I. Jonsdottir, and M. Nahm. 2003. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for quantitation of human antibodies to pneumococcal polysaccharides. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 10:514-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winkelstein, J. A., M. R. Smith, and H. S. Shin. 1975. The role of C3 as an opsonin in the early stages of infection. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 149:397-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. 1999. Pneumococcal vaccines. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 74:177-183.10437429 [Google Scholar]