Abstract

The particular virulence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum derives from export of parasite-encoded proteins to the surface of the mature erythrocytes in which it resides. The mechanisms and machinery for the export of proteins to the erythrocyte membrane are largely unknown. In other eukaryotic cells, cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains or “rafts” have been shown to play an important role in the export of proteins to the cell surface. Our data suggest that depletion of cholesterol from the erythrocyte membrane with methyl-β-cyclodextrin significantly inhibits the delivery of the major virulence factor P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1). The trafficking defect appears to lie at the level of transfer of PfEMP1 from parasite-derived membranous structures within the infected erythrocyte cytoplasm, known as the Maurer's clefts, to the erythrocyte membrane. Thus our data suggest that delivery of this key cytoadherence-mediating protein to the host erythrocyte membrane involves insertion of PfEMP1 at cholesterol-rich microdomains. GTP-dependent vesicle budding and fusion events are also involved in many trafficking processes. To determine whether GTP-dependent events are involved in PfEMP1 trafficking, we have incorporated non-membrane-permeating GTP analogs inside resealed erythrocytes. Although these nonhydrolyzable GTP analogs reduced erythrocyte invasion efficiency and partially retarded growth of the intracellular parasite, they appeared to have little direct effect on PfEMP1 trafficking.

Plasmodium falciparum is the etiological agent of the most virulent form of human malaria. This apicomplexan parasite resides in mature human red blood cells (RBCs) during a phase of cyclical asexual development. The particular virulence of P. falciparum is due in part to the insertion of cytoadherence-mediating proteins into the membrane of its host cell. These proteins mediate adhesion of infected RBCs (IRBCs) within the microvasculature—a process that results in the occlusion of these vessels within vital organs. The best characterized of these parasite-encoded molecules are a family of proteins known as P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) encoded by the var multigene family. Members of this family have been shown to mediate adhesion to a number of host molecules, including ICAM-1, CD31, CD36, and glycosaminoglycans (30). Switching expression between different var genes allows the parasite to undergo clonal antigenic variation, thus evading the host's protective antibody response (12, 62). PfEMP1 is thus of considerable research interest, as it is both a major virulence factor and an immune target. And yet, despite its importance, relatively little is known about the trafficking of PfEMP1 from the parasite across the parasitophorous vacuole in which the parasite resides and through the host cell cytoplasm to the RBC surface.

It has been assumed that PfEMP1, like other integral membrane proteins, is initially cotranslationally inserted into the parasite endoplasmic reticulum membrane and subsequently delivered to the RBC membrane via a series of vesicle-mediated trafficking events (10). However, given that RBCs lack endogenous coat proteins needed for vesicle-mediated transport, the pathway for trafficking across the host cell cytosol clearly involves an unusual mechanism. Immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy (EM) studies indicate that plasmodial homologs of the coat proteins, Sar1p, Sec31p, and Sec23p, are exported to the host RBC cytoplasm, where they are associated with structures known as the Maurer's clefts (1, 4, 65, 68, 69). Moreover small vesicles, potentially involved in trafficking from the parasitophorous vacuole membrane to the host cell membrane, have been visualized in the RBC cytosol (65, 66).

However, recent data suggest that PfEMP1 trafficking to the host cell surface may involve a completely novel mechanism. Transfected malaria parasites expressing a chimera of a PfEMP1 fragment with green fluorescent protein (GFP) have been analyzed by fluorescence photobleaching techniques (28). The dynamics of the chimera suggest that it is present in the RBC cytosol as a large protein complex rather than as a membrane-embedded protein in phospholipid vesicles (28). In addition, data analyzing the solubility properties of PfEMP1 have shown that it remains bicarbonate extractable during trafficking through the parasite's endomembrane system (43). Together, these data suggest that PfEMP1 may be trafficked as a soluble chaperoned complex and only inserted into a membrane environment at the Maurer's clefts or the RBC membrane.

Lauer et al. (32) have shown that cholesterol is required for the inward transport of some host cell proteins from the RBC membrane to the parasitophorous vacuole. Cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains have also been reported to be important in the export of proteins to the cell surface in other eukaryotic systems (35, 37). For example, insertion of proteins into membranes has been shown to be dependent on normal levels of membrane cholesterol (20). Similarly, SNARE proteins, which are involved in docking and fusion of vesicles, have been shown to accumulate at cholesterol-rich domains (7).

Given the potential importance of cholesterol-rich microdomains in cellular trafficking processes, we have examined the effect of cholesterol depletion on trafficking of PfEMP1 to the RBC surface. To examine the potential involvement of GTP-dependent vesicle-mediated events we have tested the effects of two GTP analogs, guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS) and guanosine-5′-(β,γ-imido)-triphosphate (GDPNP), on trafficking of PfEMP1 across the IRBC cytosol.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasite culture.

P. falciparum parasites of the A4, 3D7, and CS2 lines were cultured in medium containing 8% human serum (A4) or 4% serum and 0.25% AlbuMAX (GIBCO-BRL) (3D7, CS2) as described previously (18, 49). The A4 clone was derived from P. falciparum IT4/25/5 by micromanipulation (52). A4 IRBCs were repeatedly selected for binding to immobilized BC6 monoclonal antibody (MAb), which recognizes the A4-specific PfEMP1 molecule (18). Flow cytometric analysis with BC6 MAb showed positive staining on the surface of ∼80% of A4 IRBCs. The CS2 line was derived from isolate FAF-EA8 (which is genetically the same as IT4/25/5) by panning for adhesion to Chinese hamster ovary cells and to immobilized chondroitin sulfate A (54). Cultures were synchronized and harvested as described previously (29).

Cholesterol depletion and reloading of RBCs and IRBCs.

Tightly synchronous early ring stage cultures (5 to 10% parasitemia; ∼10-h stage) were incubated in the presence or absence of methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MBCD) (0 to 10 mM) in serum-free medium at 37°C for 20 min and washed twice with serum-free medium. Following depletion some cells were reloaded with cholesterol by addition of a complex of cholesterol-MBCD for 2 h at 37°C and then two washes with serum-free medium (8). Cells were suspended in fresh complete medium prepared with 8% serum and returned to culture at 37°C. In some experiments 0.5% AlbuMAX was employed instead of 8% serum. Uninfected RBCs were similarly depleted of cholesterol and then mixed with an inoculum of purified schizont IRBCs.

TLC analysis of lipids.

Samples of RBCs were prepared by lysis with 1% saponin in phosphate-buffered saline containing 5 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate for 10 min on ice. Lipids were extracted using a two-phase system comprising chloroform:methanol:water (8:4:3) from approximately 5 × 108 RBCs. Samples were separated on Silica Gel 60 thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates (Merck) by use of chloroform:methanol:water (50:20:3). Lipid standards (dipalmitoyl phosphatidylethanolamine, dimyristoyl phosphatidylcholine, and cholesterol; all from Sigma) were prepared in chloroform. The plates were stained with amido black 10B (Sigma) in 1% acetic acid-water (46). The TLC plates were scanned and the images analyzed with background correction by use of NIH ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

Resealing of RBCs and invasion assays.

Using a modification of the protocol of Dluzewski et al. (14), packed washed RBCs (1 ml) were incubated with gentle agitation on ice for 10 min with 4 ml of ice-cold 1 mM MgATP-5 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5) in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of GTP, GTPγS, or GDPNP (Sigma). NaCl was added from a concentrated stock to achieve a final concentration of 0.15 M, and samples were resealed at 37°C for 45 min. Cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI medium (or in RPMI medium containing a concentration of GTP analogue equivalent to that trapped within the resealed cells) and mixed with an inoculum of purified schizont IRBCs (>95% parasitemia). Parasitemia levels were determined after 20 to 48 h by staining thin smears with Giemsa reagent and counting at least 1,000 cells. Parasitemias were recorded as an invasion index, i.e., the observed parasitemia at a given time relative to the inoculating parasitemia, or as growth rates, i.e., the percentage of parasites at a particular stage relative to the total parasitemia amount. Parasite stages were assessed by morphology of Giemsa-stained smears under light microscopy (61). The growth of treated cultures was routinely monitored for 3 days to determine any long-term effects on growth.

To examine the homogeneity of the incorporation of exogenous components, fluorescein-labeled bovine serum albumin [prepared by reacting 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) with bovine serum albumin (Sigma) in 0.1 M NaHCO3 and purified by gel filtration chromatography (26)] was trapped inside resealed RBCs. The resealed cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometric analysis. The efficiency of capture of nucleotides inside the resealed RBCs was determined by monitoring entrapment of trace levels of [32P]GTP (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences). Leakage of the nucleotide from resealed cells was monitored by pelleting the cells at different incubation time points and estimating the level of the radiolabel in the supernatant. The amount of trapped nucleotide released upon streptolysin O lysis (6) of resealed IRBCs was compared with the amount released upon freeze-thawing and used to determine the relative levels of nucleotide trapped in the host and parasite compartments. Chemical stability of the guanine nucleotide analogues during incubation at 37°C was monitored by TLC.

Immunolabeling and flow cytometry protocols.

The BC6 MAb, which recognizes the A4 PfEMP1 external domain (52, 63), and an anti-CS2 rabbit antiserum (50) were generated as described previously. For flow cytometry applications, a multilayer labeling protocol was employed which involved incubation with MAb BC6 (52) followed by rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) and then fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled pig anti-rabbit IgG (29) or rabbit anti-CS2 antiserum followed by FITC-labeled pig anti-rabbit IgG each containing 5 μg/ml ethidium bromide. The numbers of FITC- and ethidium bromide-labeled cells were analyzed in triplicate using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur flow cytometer and Cell Quest or WinMIDI software.

Fluorescence and EM of P. falciparum IRBCs.

A transfected P. falciparum line expressing a PfEMP1 fragment-GFP chimera (K1-119TmATS-GFP) that is trafficked to the Maurer's clefts and RBC surface was generated previously (28). Samples were viewed with a Leica TCS-SP2 confocal microscope as described elsewhere (55). Samples of control or treated strain A4 P. falciparum IRBCs were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 1% tannic acid, dehydrated, and embedded in epoxy resin as described previously (65). Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and sodium bismuth before examination in a Hitachi 7000 scanning transmission EM.

RESULTS

Effect of depletion of host cell cholesterol on growth and morphology of P. falciparum.

Cholesterol-rich microdomains have been shown to be involved in correct delivery and presentation of cell surface receptors in a number of eukaryotic systems (7, 20). To examine a possible role of host cell cholesterol in promoting delivery or insertion of PfEMP1 at the RBC surface, we have depleted cholesterol from RBC membranes and measured the effect on parasite maturation and PfEMP1 trafficking. RBC membranes are rich in cholesterol (50 mol percent) (11). By contrast, the intracellular membranes of the parasite appear to be completely devoid of cholesterol, while the parasitophorous vacuole membrane probably contains intermediate levels (24, 36, 67). We employed MBCD treatment to extract cholesterol from RBC membranes (8, 32). TLC analysis indicated 50% and 70% depletion of the RBC membrane cholesterol for 5 mM and 10 mM MBCD, respectively (Fig. 1A). Cholesterol-depleted RBCs incubated for 20 h in the presence of 0.5% fatty acid-loaded albumin (AlbuMAX) showed little change in cholesterol content over this period compared with control results. However, 5 and 10 mM MBCD-treated cells incubated in the presence of 8% serum showed partial repletion of cholesterol levels to about 40% and 50% of control levels, respectively (Fig. 1A). Uninfected and ring stage IRBCs were relatively resistant to lysis during treatment with up to 10 mM MBCD; however, higher concentrations of MBCD caused significant RBC lysis and investigation of those was not pursued. Similarly, treatment of trophozoite stage IRBCs causes release of parasites from the host cells (32) and was not employed.

FIG. 1.

Intraerythrocytic development of strain A4 P. falciparum in cholesterol-depleted RBCs. (A) Washed RBCs were incubated at 37°C for 20 min in the presence of MBCD (0 to 10 mM). MBCD-treated RBCs were incubated for 20 h in medium containing 8% serum (triangles) or 0.5% AlbuMAX (squares) or prepared just before analysis (circles). The cells were lysed and washed and the extracted lipids separated by TLC, stained with amido black 10B, and analyzed by scanning densitometry. (B) Tightly synchronized early ring stage IRBCs (∼6% parasitemia; ∼10-h stage) were incubated at 37°C for 20 min in the presence of MBCD (0 to 10 mM), with or without repletion, and then returned to culture for 20 h in serum-containing medium. Smears of duplicate samples were prepared and stained with Giemsa, and 1,000 cells per slide were counted. The number of cell infected with >16-h-stage parasites was determined relative to total parasitemia results. The data represent the mean of duplicates in a typical experiment that was performed three times.

Cholesterol-depleted RBCs can be made replete by incubation with cholesterol-loaded MBCD (25). We examined the effects of cholesterol depletion and repletion on the development of A4 parasites. Treatment of early ring stage (6- to 14-h stage) IRBCs with up to 10 mM MBCD did not significantly affect the rate of maturation of the intraerythrocytic parasite. Parasites maintained equivalent stages of development in treated and control RBCs, and by 20 h posttreatment the entire population of the parasites in both samples had reached the trophozoite stage (20 to 34 h). Moreover, the parasites were able to complete the life cycle and to reinvade (although reinvasion occurred with reduced efficiency; data not shown). The parasites also developed normally in cholesterol-replenished cells. To enable a direct comparison with results for the GTP analogs (see below) the data for parasite development are presented in Fig. 1B as parasites with a morphological stage of >16 h and are expressed as a percentage of the total number of parasites. There was no delay in maturation in any of the samples.

The ultrastructure of A4 and CS2 strain parasites in cholesterol-depleted RBCs was examined by EM (Fig. 2A and data not shown). Crenation of the host cell membrane was observed in some cells; however, the intracellular parasites showed no major abnormalities. Characteristic Maurer's clefts (2, 3) were observed, and knobs with normal morphology were seen to decorate the RBC membrane. Semiquantitative analysis of the electron micrographs (examining at least 10 IRBCs for each treatment type) revealed no obvious difference in numbers of knobs between control and treated cells.

FIG. 2.

Effect of cholesterol depletion on parasite ultrastructure and trafficking of PfEMP1 in control and transfected parasites. (A) Early ring stage (∼10 h) strain A4 parasites were mock treated (left panel) or treated with 5 mM (middle panel) or 10 mM (right panel) MBCD and returned to culture for 20 h in serum-containing medium. The trophozoite stage samples were prepared for transmission EM analysis. Maurer's clefts are indicated with arrows; knobs are indicated with arrowheads. Bar, 2 μm. (B) Intact strain A4 IRBCs were incubated with BC6 MAb followed by fluorescently labeled anti-mouse IgG. Imaging by confocal microscopy indicates that fluorescence labeling is restricted to the IRBC surface (left panels; bar, 5 μm). Strain A4 parasites developing in control (middle panel) or MBCD-treated (right panel) IRBCs were incubated with BC6 MAb and prepared for analysis by flow cytometry. The data represent the ethidium bromide and fluorescein fluorescence signals. The crossing lines indicate the cell populations selected for analysis. The upper quadrants represent IRBCs, with the right quadrant representing BC6-positive IRBCs. (C) Early ring stage 3D7 transfectants expressing a GFP-PfEMP1 chimera were mock treated or treated with 5 or 10 mM MBCD and returned to culture for 20 h in serum-containing medium. Imaging by confocal microscopy indicates that the fluorescence is largely associated with the Maurer's clefts. A weak rim of fluorescence at the IRBC surface is also observed. Bar, 5 μm.

Effect of cholesterol depletion on PfEMP1 trafficking.

Transcription of the var gene(s) is initiated in early ring stage parasites, and the level of transcript peaks at 12 h after RBC invasion (30). However, transit of newly synthesized protein to the RBC surface requires about 9 h, first appearing at the RBC membrane about 16 h after invasion. Moreover, a significant proportion of the PfEMP1 population appears to remain in an intracellular pool associated with the Maurer's clefts (18, 29). We have used flow cytometric analysis to quantitate the amount of PfEMP1 on the surface of control and MBCD-treated RBCs infected with A4 parasites. The A4 parasite has been selected for binding to the BC6 MAb, which specifically recognizes an epitope within the external domain of the A4 PfEMP1 (18, 29). Ethidium bromide staining was used to distinguish uninfected RBCs from IRBCs, and the FITC signal (in a three-layer antibody labeling protocol) was used to monitor PfEMP1 levels in control and resealed RBCs (Fig. 2B, right panels). To investigate the effect of cholesterol depletion on PfEMP1 delivery to the IRBC surface, we allowed parasites to mature within cholesterol-depleted cells and examined surface-exposed PfEMP1 at about 30 h after invasion. In a typical experiment A4 parasites developing in control IRBCs were about 80 to 85% BC6 reactive by this stage. For comparison with other samples, the mean fluorescence of the control sample was taken as 100%.

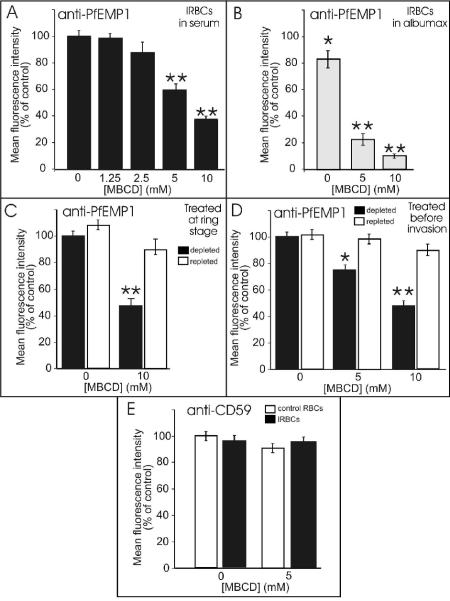

A4 parasites are routinely cultured in 8% serum, as this has been found to help maintain high levels of PfEMP1 expression (unpublished data). Therefore, initially we examined PfEMP1 surface expression in control and cholesterol-depleted IRBCs incubated for 20 h in the presence of 8% serum. We observed a significant decrease in BC6 reactivity in treated cells (Fig. 2B, right panels; Fig. 3A). In IRBCs treated with 10 mM MBCD, the levels of PfEMP1 surface exposure were less than 40% of control levels. This indicates that normal levels of host cell cholesterol are needed for efficient transfer of PfEMP1 to the RBC membrane.

FIG. 3.

Effect of cholesterol depletion on surface-exposed PfEMP1 in IRBCs. Early ring stage (∼10 h) strain A4 parasites were mock treated or treated with increasing concentrations of MBCD and returned to culture for 20 h in medium containing 8% serum (A) or 0.5% AlbuMAX (B). Samples were incubated with BC6 MAb and ethidium bromide and prepared for analysis by flow cytometry as depicted in Fig. 2B. A4 parasites developing in control IRBCs were typically 80% to 85% BC6 reactive by this stage. To facilitate comparison between samples, the mean fluorescence of the control sample was taken as 100%. (C) Following treatment or mock treatment of A4 IRBCs with 5 mM MBCD, aliquots of treated ring stage cultures were left depleted (filled bars) or reloaded with cholesterol (open bars) by incubation with a complex of cholesterol:MBCD for 2 h at 37°C and returned to culture for 20 h. Samples were incubated with BC6 MAb, and surface-exposed PfEMP1 was assessed by flow cytometry. (D) Uninfected RBCs were treated or mock treated with MBCD, and aliquots were reloaded with cholesterol by incubation with a complex of cholesterol:MBCD. The treated RBCs were mixed with an aliquot of schizont stage A4 IRBCs and returned to culture for 35 h. Samples were incubated with BC6 MAb, and surface-exposed PfEMP1 was assessed by flow cytometry. (E) Ring stage A4 IRBCs were cholesterol depleted or mock treated for 2 h at 37°C and returned to culture for 20 h. Samples were incubated with anti-CD59 MAb and analyzed by flow cytometry. MBCD treatment did not alter CD59 levels, indicating that it does not cause loss of surface proteins. The data represent the averages plus or minus standard deviations for triplicate determinations of the mean fluorescence intensity for the antibody-positive IRBCs incubated for 20 h in the presence of serum. Values that are significantly different (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) from those for controls are marked with a single or double asterisk, respectively.

As incubation for 20 h in serum-containing medium allows partial repletion of cholesterol levels (Fig. 1A), we also examined the level of surface exposure of A4 PfEMP1 in control and cholesterol-depleted IRBCs cultured in the presence of AlbuMAX (Fig. 3B). AlbuMAX is often used as a serum substitute for the culture of P. falciparum (51). We found that even without treatment with MBCD, the level of surface expression of PfEMP1 was consistently lower in IRBCs incubated in the absence of serum (Fig. 3B; 0 mM MBCD). For MBDC-treated IRBCs, the decrease in BC6 reactivity was even more pronounced. Indeed, PfEMP1 surface exposure was almost completed ablated in IRBCs treated with 10 mM MBCD (Fig. 3B).

To ensure that the effect on PfEMP1 trafficking was not due to an irreversible effect of the cholesterol depletion treatment, we replenished cells by incubation with cholesterol-loaded MBCD. We found that reloading depleted cells with cholesterol largely reversed the effect on PfEMP1 trafficking to the RBC surface (Fig. 3C, open bars).

We also examined the effect of depleting RBC cholesterol levels prior to infection with P. falciparum. For these experiments synchronized schizont stage strain A4 parasites (i.e., at about 38 h of the 48 h cycle; >95% parasitemia) were harvested and mixed with cholesterol-depleted RBCs. The efficiency of invasion was reduced to about 40% of the control level, as reported previously (15, 59); however, those parasites that invaded successfully were able to develop normally. When the parasites reached the trophozoite stage, similar decreases in PfEMP1 surface exposure were observed (Fig. 3D). Again, repletion of cholesterol levels before the invasion step restored the level of surface-exposed PfEMP1 to control levels (Fig. 3D).

The effect of depletion of host cell cholesterol on PfEMP1 trafficking in parasites of the CS2 strain was also examined. The CS2 parasite has been selected for binding to chondroitin sulfate A (53). A monoclonal antibody to the CS2 PfEMP1 is not available; however, a polyclonal antiserum that specifically recognizes RBCs infected with CS2 strain parasites has been generated and it is likely that this polyclonal antiserum mainly recognizes the external domain of CS2 PfEMP1 (16, 50). Cholesterol depletion (using 10 mM MBCD) also decreased surface-exposed PfEMP1 levels in RBCs parasitized with CS2 strain parasites to 60% ± 6% of control levels (data not shown).

Effect of cholesterol depletion on CD59 levels.

We examined the effect of cholesterol depletion on the surface accessibility of the endogenous RBC protein, CD59 (13). CD59 is a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-anchored RBC protein that is likely to be associated with cholesterol-rich domains in the RBC membrane, and it is possible that its organization and hence accessibility to labeling might be affected by cholesterol depletion. In a previous study, Lauer et al. used immunofluorescence to examine the binding of a specific MAb to CD59 and found a decrease in labeling in IRBCs (32). By contrast, we found that control and trophozoite IRBCs showed similar levels of CD59, as judged by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 3E). Moreover, treatment of either infected or uninfected RBCs with 5 mM MBCD also had no effect on the measured CD59 levels (Fig. 3E). This suggests that cholesterol depletion does not cause a major defect in membrane integrity or result in gross loss of lipid raft-associated proteins from the RBC surface.

Effect of cholesterol depletion on transfer of PfEMP1 to the Maurer's clefts.

Transfected parasites have recently been generated that express a chimera comprising the KAHRP PEXEL/VTS motif and the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of PfEMP1 appended to green fluorescent protein (K1-119-PfEMP1-GFP). This chimera is directed to the host cell cytosol, where it associates with the Maurer's clefts, and at least part of the population of chimeric molecules eventually becomes exposed at the IRBC surface (28). We examined the effect of cholesterol depletion on trafficking of the K1-119-PfEMP1-GFP chimera in these transfectants. We found that the PfEMP1 chimera was correctly trafficked to the RBC cytosol and became associated with structures in the RBC cytosol (Fig. 2C). These structures have previously been shown to be Maurer's clefts (28). Analysis of the numbers of Maurer's clefts in 20 different cells of each treatment type revealed 6 ± 2 Maurer's clefts in control and 5 mM and 10 mM MBCD-treated cells. Thus, cholesterol depletion does not appear to affect the formation of Maurer's clefts or trafficking to this compartment but may affect trafficking from the Maurer's clefts to the RBC membrane.

Effect of GTP analogs on invasion of RBCs by P. falciparum.

Components of the plasmodial COPII complex appear to be exported to the host cell cytosol and to associate with the Maurer's clefts (1, 4, 65, 68, 69). This suggests that GTP-dependent, vesicle-mediated events could be involved in PfEMP1 trafficking. The GTP analogs GTPγS and GDPNP have been shown to inhibit GTP hydrolysis by small GTPases and affect the process of cargo packaging into COP vesicles, as well as preventing vesicle fusion with target membranes (42).

In light of this and of the data described above, we wanted to examine the effect of GTP analogs on trafficking of proteins across the RBC cytosol. However, RBC membranes do not contain nucleotide transporters, and our preliminary studies indicated that radiolabeled nucleotides are unable to penetrate the RBC membrane of either uninfected RBCs or IRBCs (data not shown). Therefore, we developed a method for trapping non-membrane-permeating GTP analogs in resealed RBCs that could subsequently be used to support parasite growth.

It has previously been shown that human RBCs can be lysed by dialysis at high hematocrit levels against a low ionic strength medium containing 1 mM ATP and resealed by dialysis at physiological ionic strength. These resealed cells are invaded with high efficiency by P. falciparum (14). The physical characteristics of the resealed cells and the requirements for supporting parasite growth have been extensively examined previously (14, 47, 48).

We have used a slightly modified resealing protocol that avoids the dialysis steps and produces resealed cells reproducibly containing hemoglobin at 44% ± 8% of the initial level (as judged from the absorbance at 412 nm of 10 different samples of resealed cells). Fluorescence microscopy and fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis of RBCs resealed in the presence of fluorescently labeled bovine serum albumin revealed that the method allows uniform encapsulation of the entrapped species. The efficiency of trapping of radiolabeled GTP in resealed cells was analyzed in five different samples and found to be 13% ± 3%.

Synchronized schizont stage (i.e., at about 38 h of the 48-h cycle; >95% parasitemia) strain A4 parasites were harvested and mixed with resealed RBCs containing increasing concentrations of GTP, GTPγS, or GDPNP. The amount of GTP analogues in the resealing medium was adjusted to give a range of intracellular (trapped) concentrations of the analogues from 0 to 100 μM. To determine the fate of the entrapped nucleotides, parasites were allowed to develop in resealed cells containing radiolabeled GTP for 28 h; then, the IRBCs (10% parasitemia) were lysed using streptolysin O. This process released 99.1% ± 0.4% of the entrapped radiolabeled nucleotide, indicating that the nucleotide is largely associated with the host cell compartment and not taken up into the parasite. In some samples we also added the GTP analogues at concentrations equivalent to the estimated trapped concentration on the outside of the resealed cells. Semiquantitative TLC analysis indicated that the GTP analogues are stable for >20 h during incubation in aqueous media at 37°C (data not shown).

We examined the efficiency of invasion of the resealed RBCs. At about 10 h after invasion (i.e., at 20 h after inoculation) we found that the released merozoites had invaded intact cells with an invasion index of about 3.5 and control resealed RBCs with an index of 2.2. (The invasion index is the ratio of the observed parasitemia at a given time to the inoculating parasitemia.) For ready comparison with other samples, we have expressed the invasion efficiency for the different samples relative to that for RBC resealed in the absence of guanine nucleotide (Fig. 4A). We examined the invasion of RBCs resealed in the presence of increasing concentrations of GTP, GTPγS, or GDPNP. RBCs resealed in the presence of GTP were invaded with efficiency similar to the control results (Fig. 4A); however, we found that both GTPγS and GDPNP, at concentrations of 50 and 100 μM, reduced the invasion efficiency by about 45% and 60%, respectively, compared with the results seen with controls resealed in the absence of inhibitor (Fig. 4A). A similar effect was observed when GTPγS was added at both the outside and inside of resealed RBCs (Fig. 4A). By contrast, addition of GTPγS at a concentration of up to 200 μM to the medium supporting a culture of intact IRBCs had no effect on the invasion efficiency (data not shown), indicating that the nucleotide analogue must have access to the erythrocyte cytoplasm to exert an effect on invasion.

FIG. 4.

Effect of intracellular GTP analogs on the ability of P. falciparum to invade RBCs and undergo intraerythrocytic development. (A) Isolated schizont stage parasites were added to intact RBCs or to RBCs resealed in the absence or presence of GTP, GTPγS, or GDPNP and returned to culture (initial parasitemia, ∼3%). The concentrations of guanine nucleotides are the estimated intraerythrocytic concentrations, assuming 13% trapping of added nucleotide. The subscripts refer to samples in which the guanine nucleotides were trapped inside (i) or also added externally (i/e). After 20 h, smears were prepared and stained with Giemsa, and 1,000 cells per slide were counted. The ratio of the ring stage parasitemia to the inoculating parasitemia was determined, and the data are expressed as invasion efficiency relative to the control in the absence of guanine nucleotide. At ∼28 h after invasion (B) and ∼38 h after invasion (C), additional smears were prepared and the number of cell infected with >16-h-stage parasites was determined relative to total parasitemia numbers. The data represent the averages of duplicates in typical experiments that were performed at least three times. p.i., postinvasion.

Effect of intracellular GTP analogs on maturation and morphology of P. falciparum IRBCs.

The extent of intracellular parasite maturation was monitored at approximately 28 h after invasion (i.e., 38 h after inoculation) by analysis of Giemsa-stained smears and assessment of parasite stages (61). PfEMP1 first appears at the surface of parasitized RBCs at ∼16 h after invasion (29). Therefore, we assessed the number of parasites that were morphologically characterized at >16 h and expressed this as a percentage of the total parasitemia (Fig. 4B). Parasites in RBCs resealed in the presence of GTP showed a rate of maturation similar to that seen with RBCs resealed in the absence of guanine nucleotide. However, in RBCs resealed in the presence of higher concentrations of GTPγS or GDPNP, parasite growth was somewhat delayed, as indicated by the dose-dependent decrease in the percentage of mature stage (>16 h) parasites at 28 h after invasion (Fig. 4B). Despite the delayed maturation, the majority of the population of parasites in RBCs containing GTP analogues did reach maturity by 38 h after invasion (Fig. 4C) and were able to reinvade (albeit with reduced efficiency; data not shown). When GTPγS was added to both the exterior and interior of resealed RBCs, a proportion of the parasites failed to reach maturity even 38 h after invasion. These data indicate that the GTPase inhibitors substantially delay maturation of the parasite. We also examined the ability of parasites of the CS2 and 3D7 strains to invade and mature within resealed RBCs and found similar effects of the GTP analogues on these strains (data not shown).

The ultrastructural integrity of A4 intracellular parasites developing within RBCs resealed in the absence of guanine nucleotide (Fig. 5A) or in the presence of 100 μM GTP, GTPγS, or GDPNP (Fig. 5B to D) was examined by EM. In resealed cells the host cell membrane showed morphological derangement and often appeared to have flattened around the parasite; however, the parasite exhibited normal morphology and Maurer's clefts were observed in the RBC cytoplasm and characteristic knob structures at the RBC membrane (Fig. 5A). In parasites growing in cells containing the GTP analogs there was some evidence for increased vacuolarization of the parasite cytoplasm, but, surprisingly, even at the higher levels of GTP analogs there were no obvious major abnormalities. The host cell cytosol appeared to contain numbers of Maurer's clefts similar to those seen with controls, and the host cell membrane was studded with knobs (Fig. 5C and D). There was no evidence for accumulation of vesicles in the host cell cytosol as has been reported for AlF4 treatment (65, 66).

FIG. 5.

Ultrastructure of P. falciparum in RBCs resealed to contain GTP analogs. P. falciparum of the A4 strain was cultured in RBCs resealed in the absence of guanine nucleotide (A) or in the presence of an estimated intracellular concentration of 100 μM GTP (B), 100 μM GTPγS (C) or 100 μM GDPNP (D). The samples were prepared for transmission EM analysis after 42 h of culture (i.e., ∼32 h postinvasion). Maurer's clefts are indicated with arrows; knobs are indicated with arrowheads. Bar, 1 μm.

Effect of intracellular GTP analogs on surface exposure of PfEMP1 in P. falciparum IRBCs.

We have used flow cytometric analysis to quantitate the amount of PfEMP1 on the surface of control and resealed RBCs infected with A4 parasites. Isolated mature-stage A4 IRBCs (>95% parasitemia) were mixed with control or resealed RBCs. At ∼28 h after reinvasion (i.e., at 38 h after inoculation), the culture was assessed for the presence of surface-exposed PfEMP1 by flow cytometry using the BC6 MAb (29).

In flow cytometric analyses, the resealed cells generated lower forward and side scatter (Fig. 6A, upper panels); however, there was no evidence for extensive fragmentation of the cells. In a typical experiment (Fig. 6B), A4 parasites infecting resealed RBCs without GTPase inhibitor were about 70% to 80% BC6 reactive by about 28 h after invasion. The mean fluorescence value for these cells was taken as 100%, and the fluorescence of other samples was expressed relative to this control. Intact IRBCs showed a moderately higher mean fluorescence value (113%), indicating that the efficiency of PfEMP1 trafficking in intact RBCs is somewhat higher than in resealed RBCs. When A4 parasites developed in RBCs that had been resealed in the presence of increasing amounts of GTP, a small but significant increase in PfEMP1 surface exposure was observed at 50 μM GTP but this effect was reversed at 100 μM GTP (Fig. 6B, filled diamonds). In RBCs resealed in the presence of increasing amounts of GTPγS or GDPNP, we observed a decrease in PfEMP1 surface exposure (Fig. 6B, filled triangles and squares). In these cells the level of surface exposure of PfEMP1 was about 60% of control levels. A similar decrease was observed for cells in which GTPγS was also added to the outside of the resealed cells (Fig. 6B, open squares).

FIG. 6.

Modulation of surface-exposed PfEMP1 by GTP analogs. (A) Strain A4 parasites developing in intact (left panels) or resealed (right panels) RBCs were incubated with BC6 MAb and prepared for analysis by flow cytometry. The top panels represent the side and forward scatter of the intact and resealed cells. The lower panels represent the ethidium bromide and fluorescein fluorescence. The crossing lines indicate the cell populations selected for analysis. The upper quadrants represent IRBCs, with the right quadrant representing BC6-positive IRBCs. (B) Isolated schizont stage IRBCs (A4 strain) were added to intact RBCs or to RBCs resealed in the absence or presence of different concentrations of GTP, GTPγS, or GDPNP and returned to culture. Concentrations presented represent the estimated intracellular concentrations. The subscripts refer to samples in which the guanine nucleotides were trapped inside (i) or also added externally (i/e). After 38 h (∼28 h postinvasion [p.i.], left panel) or 48 h (∼38 h p.i., right panel), samples were incubated with BC6 MAb and ethidium bromide and prepared for analysis by flow cytometry. Values that are significantly different (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01) from those for RBCs resealed in the absence of GTP analogue are marked with single or double asterisks, respectively. The data represent the averages plus or minus standard deviations for triplicate determinations of the mean fluorescence intensity for the antibody-positive IRBCs.

However, the defect in PfEMP1 trafficking in the presence of the GTP analogs appears to be largely the result of delayed maturation of the intracellular parasites. The growth data for the 28-h time point after invasion (Fig. 4B) reveal that in the presence of the GTP analogs a substantial proportion of the parasite population had failed to develop to the morphological stage, where PfEMP1 is expected to be surface expressed. By 38 h after invasion, the majority of parasites had developed beyond the 16-h morphological stage. Therefore, we also evaluated the level of expression of PfEMP1 at this time point. While there remained small but significant differences between RBCs resealed in the presence or absence of the GTP analogs at this time point, the effect was much less marked. The level of PfEMP1 expression reached about 90% to 95% of the control level (Fig. 6C). This indicates that upon maturation of the intracellular parasite PfEMP1 is eventually trafficked to the RBC surface. Additional time points between 28 h and 38 h gave intermediate levels of exposure (data not shown). Taken together, the data presented above indicate that the ability of GTP analogs to inhibit trafficking of PfEMP1 to the host cell surface is due their effect on parasite maturation.

It is worth noting that when GTPγS or GDPNP (up to 200 μM) was added at the external surface of cultures maintained in intact RBCs, there was no effect on parasite development or on PfEMP1 surface exposure, indicating that the analogs cannot penetrate intact IRBCs (data not shown).

We also examined trafficking of PfEMP1 in RBCs infected with CS2 strain parasites. Similar results were obtained for the CS2 parasites (data not shown); the GTP analogs inhibited PfEMP1 delivery but apparently as a consequence of inhibition of parasite maturation.

DISCUSSION

The plasma membranes of eukaryotic cells, including the RBC membrane (58), contain cholesterol-rich domains known as lipid rafts. Depletion of cholesterol from the plasma membrane of mammalian cells inhibits protein secretion (31, 56). Lipid rafts are also thought to be involved in the biosynthetic delivery of proteins to the yeast plasma membrane (5). Samuel et al. (59) showed that depletion of RBC membrane cholesterol had no significant effect on lipid asymmetry, membrane deformability, or the transport properties of the host membrane. However, cholesterol depletion did inhibit invasion of RBCs by P. falciparum and disrupted the association of “raft” proteins with detergent-resistant membranes isolated from IRBCs. Moreover, Lauer et al. (32) showed that normal cholesterol levels are required for the inward transport of some host cell proteins from the IRBC membrane to the parasitophorous vacuole membrane. Given the important role of cholesterol in inward transport of proteins, we investigated the effect of cholesterol depletion on PfEMP1 delivery to the RBC surface.

β-Cyclodextrins selectively bind cholesterol to form a water-soluble complex, thereby providing a means of manipulating the cholesterol content of cell membranes (8, 41). We found that treating RBCs with MBCD allowed depletion of up to 70% of the RBC cholesterol without a major effect on RBC integrity. Parasites maintained in cholesterol-depleted RBCs developed normally and showed no major ultrastructural defects, and the morphology of the Maurer's clefts and knobs in the treated cells appeared similar to that in the controls. To monitor potential effects of depletion of host cell cholesterol on trafficking of proteins across the RBC cytosol we made quantitative measurements of the delivery of PfEMP1 to the external surface of RBCs. We made use of specific antibodies recognizing the surface-exposed domains of PfEMP1 in RBCs infected with A4 and CS2 strain parasites. Interestingly, depletion of host cell cholesterol was associated with up to 90% inhibition of delivery of PfEMP1 to the RBC surface. This suggests that cholesterol-dependent events are critical for efficient delivery of this protein.

Recent studies have suggested that PfEMP1 is trafficked to Maurer's clefts as a chaperoned complex and is only inserted into a bilayer environment at the Maurer's clefts or possibly the RBC membrane (28, 43). We found that a chimera comprising PfEMP1 domains fused to GFP was trafficked to the Maurer's clefts of cholesterol-depleted cells with an efficiency apparently similar to that observed in untreated cells. This suggests that the defect in PfEMP1 delivery is beyond the Maurer's cleft compartment, possibly in the insertion of PfEMP1-containing protein complexes or Maurer's cleft-derived vesicles into the RBC membrane. The high cholesterol content of the RBC membrane may be necessary to provide a bilayer with the correct physicochemical properties to allow insertion of the PfEMP1 delivery vehicle. Cholesterol depletion has been shown to increase the fluidity of the inner leaflet of the RBC membrane (60). This could prevent insertion into regions of membrane heterogeneity at boundaries between cholesterol-rich and cholesterol-poor domains. In this context it is interesting that the posttranslational insertion of proteins into membranes has previously been shown to be dependent on normal levels of cholesterol (20).

Interestingly, even without depletion of host cell cholesterol, serum-containing medium appears to promote A4 PfEMP1 surface exposure more effectively than medium containing fatty acid-loaded albumin. This suggests that PfEMP1 exposure may be sensitive to the presence of cholesterol-containing components (lipoproteins) in the serum. In this regard it is worth noting that CD36, a major host cell receptor for PfEMP1 (30), is a major player in mediating the uptake of lipids across the plasma membranes of muscle and adipose cells (9, 17). It is interesting to speculate that PfEMP1 binding to CD36 may facilitate uptake of host lipid components into parasitized RBCs. Clearly, additional work is needed to examine this possibility.

Classical vesicle-mediated transport proceeds by successive budding and fusion events that are driven by GTP hydrolysis (70). In an effort to examine the role of GTP-mediated events in the trafficking of PfEMP1, we established a method for incorporating slowly hydrolyzable analogs of GTP inside the host cytosol. The resealed RBCs retained ∼50% of initial hemoglobin levels. The remaining hemoglobin, along with amino acids taken up from the medium, readily sustains growth of the intracellular parasite (14). We examined the effects of incorporating GTPγS and GDPNP into the host cell compartment. These GTP analogs are known to inhibit Arf1- and Sar1p-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis and thus affect the process of cargo packaging into COPI-and COPII-coated vesicles (40, 42, 45, 64). In mammalian cell-free systems half-maximal inhibition of vesicle transport is observed at 0.5 μM GTPγS (39), although higher concentrations are needed in intact cell systems (44). GTP analogs can also affect other GTP-dependent events such as microtubule elongation, protein synthesis, and the tricarboxylic acid cycle; however, these higher metabolic processes are not operational in mature human RBCs (19).

We found that RBCs resealed to contain GTP analogs were invaded less efficiently than controls resealed in the absence of inhibitor or in the presence of GTP. This inhibition of invasion does not appear to involve a direct effect (for example, inhibition of parasite tubulin polymerization) on the invading merozoite, as the analogs had no effect when added to the culture medium. It has recently been reported that signaling via heterotrimeric Gα proteins can regulate P. falciparum invasion into RBCs (22), and it is possible that sustained activation of RBC G proteins by the GTP analogs caused the observed effect on invasion efficiency.

GTP analogs also slowed parasite development, especially at high concentrations. However, treated parasites eventually completed the intraerythrocytic cycle and were able to reinvade new RBCs over several generations. The retardation of parasite development may be due to inhibition of GTPase-mediated events, such as heterotrimeric G protein signaling, in the RBC cytosol. Alternatively, it remains possible that a limited uptake of the analogs into the parasite cytoplasm could inhibit growth. Even though there appears to be no nucleotide transporter in the parasite plasma membrane (57), small amounts of the inhibitors may be taken up by endocytic feeding and escape from the digestive vacuole into the parasite cytoplasm. Our analysis of the levels of parasite-associated tracer nucleotide suggests that only very small amounts of the drug are taken up in this way, but this may be sufficient to slow maturation.

We measured surface exposure of PfEMP1 at 28 h after invasion in control and GTPase-treated IRBCs. While IRBC resealed to contain GTP showed levels of surface-exposed PfEMP1 similar to control resealed IRBC levels, we found that intracellular GTPγS or GDPNP concentrations of 50 or 100 μM inhibited PfEMP1 trafficking. This may be due to inhibition or retardation of vesicle-mediated events involved in PfEMP1 delivery. However, we found that at a later time point (38 h after invasion) nearly equivalent levels of PfEMP1 were presented at the external surface of control and GTPase inhibitor-treated RBCs. This suggests that the GTPase inhibitors exert their effect by delaying parasite maturation. Thus, while it remains possible that classical GTP-dependent trafficking processes play a role in a parasite maturation event that is needed for delivery of PfEMP1 to the IRBC surface, the observed effect is limited and it is difficult to differentiate between direct and indirect effects.

In the light of these data, it is interesting to reevaluate the likely role(s) of Maurer's cleft-associated COPII components in the IRBC cytosol. It remains possible that COPII proteins are involved in the genesis of Maurer's clefts or in the trafficking of other membrane-embedded proteins, such as Rifins and STEVORs. Transfection experiments employing GFP chimeras of trafficking components that may help to resolve the roles and locations of these components are currently under way in our laboratories.

The data presented here are in apparent conflict with previous data from one of our laboratories (65, 66) showing that that the trafficking of PfEMP1 across the RBC cytosol is inhibited by treatment with AlF4—an inhibitor that prevents coatomer shedding following vesicle formation (33). Following treatment of IRBCs with AlF4, strings of vesicles with diameters of 60 to 100 nm were observed, and immunolabeling studies indicated that the vesicles contained PfEMP1 and were associated with actin and myosin (65, 66). This apparent discrepancy may arise from the fact that GTP analogs and AlF4 inhibit different cellular targets. For example, it has been suggested that the AIF-sensitive component in vesicle transport may not be a GTP-binding protein (21). Indeed, AlF4 is known to inhibit other phosphoryl transfer reactions involved in vesicle transport, such as phospholipase D activity (27, 34). Thus, AlF4 may provide a means of further dissecting this pathway.

The important role of cholesterol-mediated events and the weak dependence on GTP hydrolysis of the delivery of PfEMP1 to the RBC surface suggests that we may need to reevaluate our model of PfEMP1 trafficking. Indeed, recent studies of transfected parasites expressing PfEMP1-GFP fusion proteins have markedly enhanced our understanding of the unusual trafficking pathway for this protein (23, 38). These studies have shown that a so-called “protein export element” or “vacuolar transport signal” within the N-terminal region of PfEMP1 is needed for transfer across the parasitophorous vacuolar membrane (23, 38). Moreover, it has been shown that transfectants expressing a chimera comprising a hydrophobic signal sequence, a protein export element or vacuolar transport signal motif, and the PfEMP1 transmembrane and C-terminal domains contain sufficient information for trafficking to the RBC membrane and presentation of the N-terminal region at the external surface (27). Interestingly, fluorescence photobleaching analysis of the exported PfEMP1-GFP chimera suggests that it is trafficked across the RBC cytosol as a large protein complex rather than as a membrane-embedded protein in phospholipid vesicles. In addition, recent data analyzing the solubility properties of PfEMP1 have shown that it remains bicarbonate extractable during trafficking through the parasite's endomembrane system (42). Together, these data suggest that PfEMP1 may be trafficked as a soluble chaperoned complex rather than as a membrane-embedded protein. These studies suggest that PfEMP1 may diffuse across the RBC cytosol as a protein complex and insert into a membrane environment only when it reaches the Maurer's clefts of the RBC membrane. We further propose that the final event in the delivery of PfEMP1 to the RBC surface involves fusion of PfEMP1-containing structures with cholesterol-rich microdomains in the RBC membrane.

In conclusion, our data suggest that trafficking of the cytoadherence protein to the RBC membrane may utilize a highly novel process. Further studies of these processes may point to possible mechanisms for interfering with the surface expression of this major virulence factor and immune target.

. . . . .

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Australian Government's Cooperative Research Centres Program, and the Wellcome Trust. Expert technical assistance was provided by Emma Fox and Bob Pinches.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adisa, A., F. R. Albano, J. Reeder, M. Foley, and L. Tilley. 2001. Evidence for a role for a Plasmodium falciparum homologue of Sec31p in the export of proteins to the surface of malaria parasite-infected erythrocytes. J. Cell Sci. 114:3377-3386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aikawa, M. 1988. Morphological changes in erythrocytes induced by malaria parasites. Biol. Cell 64:173-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aikawa, M. 1971. Plasmodium: the fine structure of malaria parasites. Exp. Parasitol. 30:284-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albano, F. R., A. Berman, N. La Greca, A. R. Hibbs, M. Wickham, M. Foley, and L. Tilley. 1999. A homologue of Sar1p localises to a novel trafficking pathway in malaria-infected erythrocytes. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 78:453-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagnat, M., S. Keranen, A. Shevchenko, and K. Simons. 2000. Lipid rafts function in biosynthetic delivery of proteins to the cell surface in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:3254-3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baumeister, S., K. Paprotka, S. Bhakdi, and K. Lingelbach. 2001. Selective permeabilization of infected host cells with pore-forming proteins provides a novel tool to study protein synthesis and viability of the intracellular apicomplexan parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 112:133-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamberlain, L. H., R. D. Burgoyne, and G. W. Gould. 2001. SNARE proteins are highly enriched in lipid rafts in PC12 cells: implications for the spatial control of exocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5619-5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christian, A. E., M. P. Haynes, M. C. Phillips, and G. H. Rothblat. 1997. Use of cyclodextrins for manipulating cellular cholesterol content. J. Lipid Res. 38:2264-2272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coburn, C. T., F. F. Knapp, Jr., M. Febbraio, A. L. Beets, R. L. Silverstein, and N. A. Abumrad. 2000. Defective uptake and utilization of long chain fatty acids in muscle and adipose tissues of CD36 knockout mice. J. Biol. Chem. 275:32523-32529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooke, B. M., K. Lingelbach, L. Bannister, and L. Tilley. 2004. Protein trafficking in Plasmodium falciparum-infected red blood cells. Trends Parasitol. 20:581-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper, R. A. 1970. Lipids of human red cell membrane: normal composition and variability in disease. Semin. Hematol. 7:296-322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig, A., and A. Scherf. 2001. Molecules on the surface of the Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocyte and their role in malaria pathogenesis and immune evasion. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 115:129-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies, A., D. L. Simmons, G. Hale, R. A. Harrison, H. Tighe, P. J. Lachmann, and H. Waldmann. 1989. CD59, an LY-6-like protein expressed in human lymphoid cells, regulates the action of the complement membrane attack complex on homologous cells. J. Exp. Med. 170:637-654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dluzewski, A. R., K. Rangachari, R. J. Wilson, and W. B. Gratzer. 1983. A cytoplasmic requirement of red cells for invasion by malarial parasites. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 9:145-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dluzewski, A. R., K. Rangachari, R. J. Wilson, and W. B. Gratzer. 1985. Relation of red cell membrane properties to invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology 91:273-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott, S. R., M. F. Duffy, T. J. Byrne, J. G. Beeson, E. J. Mann, D. W. Wilson, S. J. Rogerson, and G. V. Brown. 2005. Cross-reactive surface epitopes on chondroitin sulfate A-adherent Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes are associated with transcription of var2csa. Infect. Immun. 73:2848-2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Endemann, G., L. W. Stanton, K. S. Madden, C. M. Bryant, R. T. White, and A. A. Protter. 1993. CD36 is a receptor for oxidized low density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 268:11811-11816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gardner, J. P., R. A. Pinches, D. J. Roberts, and C. I. Newbold. 1996. Variant antigens and endothelial receptor adhesion in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:3503-3508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner, M. J., N. Hall, E. Fung, O. White, M. Berriman, R. W. Hyman, J. M. Carlton, A. Pain, K. E. Nelson, S. Bowman, et al. 2002. Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 419:498-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giddings, K. S., A. E. Johnson, and R. K. Tweten. 2003. Redefining cholesterol's role in the mechanism of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:11315-11320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Happe, S., M. Cairns, R. Roth, J. Heuser, and P. Weidman. 2000. Coatomer vesicles are not required for inhibition of Golgi transport by G-protein activators. Traffic 1:342-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison, T., B. U. Samuel, T. Akompong, H. Hamm, N. Mohandas, J. W. Lomasney, and K. Haldar. 2003. Erythrocyte G protein-coupled receptor signaling in malarial infection. Science 301:1734-1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiller, N. L., S. Bhattacharjee, C. van Ooij, K. Liolios, T. Harrison, C. Lopez-Estrano, and K. Haldar. 2004. A host-targeting signal in virulence proteins reveals a secretome in malarial infection. Science 306:1934-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson, K. E., N. Klonis, D. J. P. Ferguson, A. Adisa, C. Dogovski, and L. Tilley. 2004. Food vacuole-associated lipid bodies and heterogeneous lipid environments in the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 54:109-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein, U., G. Gimpl, and F. Fahrenholz. 1995. Alteration of the myometrial plasma membrane cholesterol content with Β-cyclodextrin modulates the binding affinity of the oxytocin receptor. Biochemistry 34:13784-13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klonis, N., M. Rug, I. Harper, M. Wickham, A. Cowman, and L. Tilley. 2002. Fluorescence photobleaching analysis for the study of cellular dynamics. Eur. Biophys. J. 31:36-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knowles, J. R. 1980. Enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer reactions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 49:877-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knuepfer, E., M. Rug, N. Klonis, L. Tilley, and A. F. Cowman. 2005. Trafficking of the major virulence factor to the surface of transfected P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Blood 105:4078-4087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kriek, N., L. Tilley, P. Horrocks, R. Pinches, B. C. Elford, D. J. Ferguson, K. Lingelbach, and C. I. Newbold. 2003. Characterization of the pathway for transport of the cytoadherence-mediating protein, PfEMP1, to the host cell surface in malaria parasite-infected erythrocytes. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1215-1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyes, S., P. Horrocks, and C. Newbold. 2001. Antigenic variation at the infected red cell surface in malaria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 55:673-707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang, T., D. Bruns, D. Wenzel, D. Riedel, P. Holroyd, C. Thiele, and R. Jahn. 2001. SNAREs are concentrated in cholesterol-dependent clusters that define docking and fusion sites for exocytosis. EMBO J. 20:2202-2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauer, S., J. VanWye, T. Harrison, H. McManus, B. U. Samuel, N. L. Hiller, N. Mohandas, and K. Haldar. 2000. Vacuolar uptake of host components, and a role for cholesterol and sphingomyelin in malarial infection. EMBO J. 19:3556-3564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li, L. 2003. The biochemistry and physiology of metallic fluoride: action, mechanism, and implications. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 14:100-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li, L., and N. Fleming. 1999. Aluminum fluoride inhibits phospholipase D activation by a GTP-binding protein-independent mechanism. FEBS Lett. 458:419-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magnani, F., C. G. Tate, S. Wynne, C. Williams, and J. Haase. 2004. Partitioning of the serotonin transporter into lipid microdomains modulates transport of serotonin. J. Biol. Chem. 279:38770-38778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maguire, P. A., and I. W. Sherman. 1990. Phospholipid composition, cholesterol content and cholesterol exchange in Plasmodium falciparum-infected red cells. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 38:105-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchand, S., A. Devillers-Thiery, S. Pons, J. Changeux, and J. Cartaud. 2002. Rapsyn escorts the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor along the exocytic pathway via association with lipid rafts. J. Neurosci. 22:8891-8901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marti, M., R. T. Good, M. Rug, E. Knuepfer, and A. F. Cowman. 2004. Targeting malaria virulence and remodeling proteins to the host erythrocyte. Science 306:1930-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melançon, P., B. S. Glick, V. Malhotra, P. J. Weidmann, T. Serafini, M. L. Gleason, L. Orci, and J. E. Rothman. 1987. Involvement of GTP-binding “G” proteins in transport through the Golgi stack. Cell 51:1053-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nickel, W., J. Malsam, et al. 1998. Uptake by COPI-coated vesicles of both anterograde and retrograde cargo is inhibited by GTPγS in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 111:3081-3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohtani, Y., T. Irie, K. Uekama, K. Fukunaga, and J. Pitha. 1989. Differential effects of alpha-, beta- and gamma-cyclodextrins on human erythrocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 186:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oka, T., and A. Nakano. 1994. Inhibition of GTP hydrolysis by Sar1p causes accumulation of vesicles that are intermediate of the ER to Golgi transport in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 124:425-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papakrivos, J., C. I. Newbold, and K. Lingelbach. 2005. A potential novel mechanism for the insertion of a membrane protein revealed by a biochemical analysis of the Plasmodium falciparum cytoadherence molecule PfEMP-1. Mol. Microbiol. 55:1272-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pepperkok, R., M. Lowe, B. Burke, and T. E. Kreis. 1998. Three distinct steps in transport of vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein from the ER to the cell surface in vivo with differential sensitivities to GTP gamma S. J. Cell Sci. 111:1877-1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pepperkok, R., J. A. Whitney, M. Gomez, and T. E. Kreis. 2000. COPI vesicles accumulating in the presence of a GTP restricted Arf1 mutant are depleted of andrograde and retrograde cargo. J. Cell Sci. 113:135-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plekhanov, A. Y. 1999. Rapid staining of lipids on thin-layer chromatograms with amido black 10B and other water-soluble stains. Anal. Biochem. 271:186-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rangachari, K., G. H. Beaven, G. B. Nash, B. Clough, A. R. Dluzewski, O. Myint, R. J. Wilson, and W. B. Gratzer. 1989. A study of red cell membrane properties in relation to malarial invasion. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 34:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rangachari, K., A. R. Dluzewski, R. J. Wilson, and W. B. Gratzer. 1987. Cytoplasmic factor required for entry of malaria parasites into RBCs. Blood 70:77-82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raynes, K., M. Foley, L. Tilley, and L. W. Deady. 1996. Novel bisquinoline antimalarials. Synthesis, antimalarial activity, and inhibition of haem polymerisation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 52:551-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reeder, J. C., A. F. Cowman, K. M. Davern, J. G. Beeson, J. K. Thompson, S. J. Rogerson, and G. V. Brown. 1999. The adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to chondroitin sulfate A is mediated by P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:5198-5202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ringwald, P., F. S. Meche, J. Bickii, and L. K. Basco. 1999. In vitro culture and drug sensitivity assay of Plasmodium falciparum with nonserum substitute and acute-phase sera. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:700-705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts, D. J., A. G. Craig, A. R. Berendt, R. Pinches, G. Nash, K. Marsh, and C. I. Newbold. 1992. Rapid switching to multiple antigenic and adhesive phenotypes in malaria. Nature 357:689-692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rogerson, S. J., and G. V. Brown. 1997. Chondroitin sulphate A as an adherence receptor for Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Parasitol. Today 13:76-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rogerson, S. J., S. C. Chaiyaroj, K. Ng, J. C. Reeder, and G. V. Brown. 1995. Chondroitin sulfate A is a cell surface receptor for Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. J. Exp. Med. 182:15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rug, M., M. E. Wickham, M. Foley, A. F. Cowman, and L. Tilley. 2004. Correct promoter control is needed for trafficking of the ring-infected erythrocyte surface antigen to the host cytosol in transfected malaria parasites. Infect. Immun. 72:6095-6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salaun, C., D. J. James, and L. H. Chamberlain. 2004. Lipid rafts and the regulation of exocytosis. Traffic 5:255-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saliba, K. J., and K. Kirk. 2001. Nutrient acquisition by intracellular apicomplexan parasites: staying in for dinner. Int. J. Parasitol. 31:1321-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salzer, U., and R. Prohaska. 2001. Stomatin, flotillin-1, and flotillin-2 are major integral proteins of erythrocyte lipid rafts. Blood 97:1141-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samuel, B. U., N. Mohandas, T. Harrison, H. McManus, W. Rosse, M. Reid, and K. Haldar. 2001. The role of cholesterol and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins of erythrocyte rafts in regulating raft protein content and malarial infection. J. Biol. Chem. 276:29319-29329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schachter, D., R. E. Abbott, U. Cogan, and M. Flamm. 1983. Lipid fluidity of the individual hemileaflets of human erythrocyte membranes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 414:19-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silamut, K., N. H. Phu, C. Whitty, G. D. Turner, K. Louwrier, N. T. Mai, J. A. Simpson, T. T. Hien, and N. J. White. 1999. A quantitative analysis of the microvascular sequestration of malaria parasites in the human brain. Am. J. Pathol. 155:395-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith, J. D., B. Gamain, D. I. Baruch, and S. Kyes. 2001. Decoding the language of var genes and Plasmodium falciparum sequestration. Trends Parasitol. 17:538-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith, J. D., S. Kyes, A. G. Craig, T. Fagan, D. Hudson-Taylor, L. H. Miller, D. I. Baruch, and C. I. Newbold. 1998. Analysis of adhesive domains from the A4VAR Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein-1 identifies a CD36 binding domain. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 97:133-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tanigawa, G., L. Orci, M. Amherdt, M. Ravazzola, B. J. Helms, and J. E. Rothman. 1993. Hydrolysis of bound GTP by ARF protein triggers uncoating of Golgi-derived COP coated vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 123:1365-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taraschi, T. F., M. E. O'Donnell, S. Martinez, T. Schneider, D. Trelka, V. M. Fowler, L. Tilley, and Y. Moriyama. 2003. Generation of an erythrocyte vesicle transport system by Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites. Blood 102:3420-3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trelka, D. P., T. G. Schneider, J. C. Reeder, and T. F. Taraschi. 2000. Evidence for vesicle-mediated trafficking of parasite proteins to the host cell cytosol and erythrocyte surface membrane in Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 106:131-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vial, H. J., M. L. Ancelin, J. R. Philippot, and M. J. Thuet. 1990. Biosynthesis and dynamics of lipids in Plasmodium-infected mature mammalian erythrocytes. Blood Cells 16:531-561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wickert, H., P. Rohrbach, S. J. Scherer, G. Krohne, and M. Lanzer. 2003. A putative Sec23 homologue of Plasmodium falciparum is located in Maurer's clefts. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 129:209-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wickham, M. E., M. Rug, S. A. Ralph, N. Klonis, G. I. McFadden, L. Tilley, and A. F. Cowman. 2001. Trafficking and assembly of the cytoadherence complex in Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes. EMBO J. 20:5636-5649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoshida, T., C. Barlowe, and R. Schekman. 1993. Requirement for a GTPase-activating protein in vesicle budding from the endoplasmic reticulum. Science 259:1466-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]