Abstract

A 7-year-old Arabian gelding was presented with a 9-month history of progressive patches of nonpruritic scaling, crusting, alopecia, and leukoderma of the periocular areas and muzzle, becoming generalized over time. Sebaceous adenitis was diagnosed on histopathologic examination. Lesions resolved without treatment, coinciding with regression of a sarcoid on the neck.

Résumé

Adénite sébacée chez un cheval Arabe hongre âgé de 7 ans. Un cheval Arabe castré âgé de 7 ans a été présenté pour une histoire de 9 mois de plaques de desquamation, de croutes, d’alopécie et de leucodermie sur les régions périoculaire et sur le nez, devenant généralisées avec le temps. Une adénite sébacée a été diagnostiquée à l’examen histologique. Les lésions se sont résorbées d’elles mêmes, en même temps que la régression d’un sarcoïde sur le cou.

(Traduit par Docteur André Blouin)

A systemically healthy, 7-year-old Arabian gelding was presented to the Western College of Veterinary Medicine with a 9-month history of progressive patches of nonpruritic crusting, scaling, alopecia, and leukoderma. The lesions began on the periocular and muzzle regions and became generalized to include the face, thorax, abdomen, and rump.

Five months previously, the horse was presented to the Western College of Veterinary Medicine for an unrelated lameness. On clinical examination, the horse had a 5 cm × 10 cm sarcoid on the left side of its neck that had been treated previously with cryotherapy and surgical excision, with limited success. The horse was otherwise systemically healthy. Dermatologically, there was a crescent-shaped lesion on the margin of the left lower eyelid with mild hyperemia of the conjunctiva and a small 2-cm diameter patch on the right dorsal aspect of the muzzle. The lesions began to appear approximately 4 mo prior to the initial presentation and had progressed from mildly pruritic patches of crusting and scaling of the hair and skin to nonpruritic fresh, smooth depigmented skin with adherent white scales after the crusts had fallen, or were rubbed, off. Several punch biopsies (9 mm) were taken from the lesions and submitted for histopathologic examination.

Overall, the epidermis was normal, apart from lid spongiosis and a progressive or abrupt disappearance of epidermal melanocytes. A mild to moderate mononuclear interface dermatitis was most intense over the areas of depigmentation. Tentative diagnosis at this time was vitiligo (Arabian Fading Syndrome) and no further treatments were implemented. All supplements and pellets in the diet had been removed 1 mo prior to presentation to rule out feed allergies, and the horse had been maintained on hay, pasture, and a small amount of oats. No pasture mates had ever shown similar clinical signs.

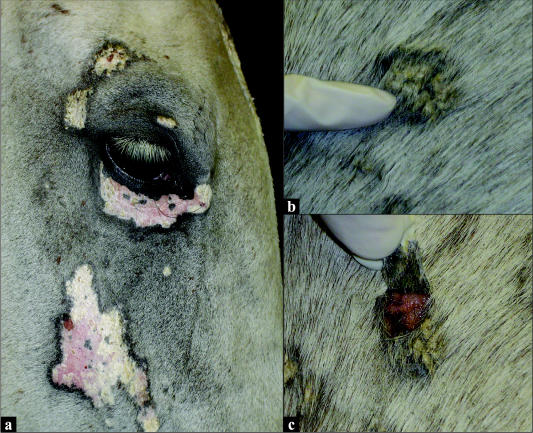

On current presentation, clinical examination proved the horse to be systemically healthy, and results from a complete blood (cell) count (CBC) and biochemical profile showed no significant abnormalities. The sarcoid on the left side of the neck had reduced minimally in size and was ulcerated on the surface. Dermatological lesions now included multifocal nonpruritic patches of crusting, scaling, alopecia, and depigmentation of the face, neck, trunk, and rump. The 9-month-old lesions on the face were now patches of smooth, depigmented skin with fine white adherent scales (Figure 1a). The 2- to 3-month-old lesions of the neck, trunk, and rump consisted of patches of scaling and crusting (Figure 1b); beneath the lesions that could be easily epilated off, the skin was smooth, moist, and depigmented, and no exudate was present (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

a) Multifocal patches of crusting, scaling, alopecia, and leukoderma on the face (9-month duration); b) A more recent lesion of crusting and scaling on the trunk (2 to 3 mo duration); c) Underlying leukoderma of an epilated lesion from the trunk.

Differential diagnoses included bacterial folliculitis or furunculosis, dermatophilosis, dermatophytosis, demodecosis, epitheliotrophic lymphoma, or discoid lupus erythematosis. A skin culture was not performed, because the lesions were not pustular or painful in nature.

Dermatophilosis normally appears initially along the dorsum in a “scald line” and demonstrates a classic “paintbrush” crusting and tufting of hair. When the crusts are pulled off, the underlying skin is erythematous to ulcerated and usually contains a green to yellow exudate. Diagnosis is made by direct smear or histopathologic examination. These were not performed, as the distribution and the appearance of the lesions were not consistent with this disease (1).

Dermatophytosis is contagious and is characterized by variable pruritis, tufted papules, and singular or coalescing annular areas of alopecia, crusting, and scaling. Fungal culture provides the definitive diagnosis; it was not performed in this case, because the lesions were uncharacteristic of the condition (1).

Demodecosis is a rare dermatosis of horses, where Demodex spp. are normal residents of the hair follicles. Clinical signs, such as alopecia and scaling over the face, neck, shoulders, and forelimbs, have only been reported in horses that are immunosuppressed (1). Both biopsy and deep skin scraping may reveal the mite (1).

Epitheliotrophic lymphoma is also rare in the horse and demonstrates a pattern of multifocal to generalized alopecia with scaling, crusting, and variable pruritis. Focal nodules or ulceration may also be present and diagnosis is determined by biopsy and histopathologic examination (1).

Discoid lupus erythematosis is a rare immunemediated dermatosis of horses with no systemic involvement. Lesions appear on the lips, nostrils, or periocular areas and may spread to affect the ears, neck, shoulders, or perineal areas. They appear as symmetric annular to oval areas of erythema, scaling or crusting, and alopecia with varying degrees of leukoderma or leukotrichia (1). Pruritis and pain are mild to absent. Histopathologic examination along with immunohistochemical staining or immunofluorescence is diagnostic (1).

Vitiligo, the original tentative diagnosis, was still a consideration; however, the progression of the lesions was not consistent with this condition (1). Typically, vitiligo causes annular areas of macular depigmentation on the skin of the lips, periocular areas, muzzle, and, occasionally, the anus, vulva, sheath, and hooves. Typically, the absence of crusting, scaling, or dermatitis and histopathologic examination is diagnostic (1). External parasites were also a differential diagnosis in this case; however, none were identified and the horse was regularly dewormed.

The horse was sedated with xylazine (Rompun, 100 mg/mL; Bayer, Toronto, Ontario), 0.5 mg/kg bodyweight (BW), IV, and butorphanol tartrate (Torbugesic, 10 mg/mL; Ayerst, Guelph, Ontario), 0.02 mg/kg BW, IV. Each biopsy site was anesthetized by a local block with mepivacaine HCL (Carbocaine®-V 2%; Pharmacia & Upjohn, Orangeville, Ontario), and 4 punch biopsies (9 mm in diameter) were taken. One sample was taken from normal skin on the right side of the neck, 1 from an area of chronic depigmentation and alopecia on the right cheek, and 2 from the most recent crusted lesions on the right rump.

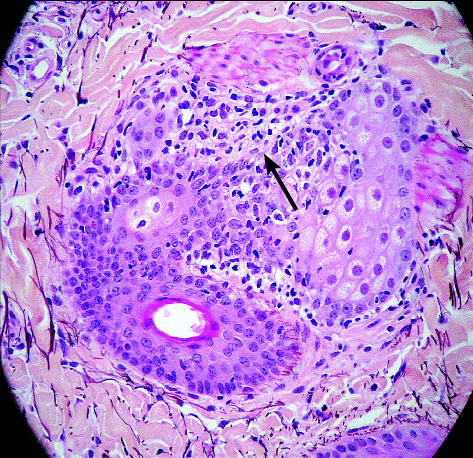

Histopathologic examination revealed lymphoid destruction of sebaceous ducts with subsequent complete loss of the sebaceous gland (Figure 2). The epidermis exhibited dramatic acanthosis due to hyperplasia and very dramatic surface hyperkeratosis, which was mainly orthokeratotic with patchy foci of parakeratosis. An occasional very small intracorneal pustule contained desiccated neutrophils and ghost-like acantholytic cells in very low numbers. No infectious agents were seen. Visible hair follicles were entering telogen phase, whereas no drop out, or destruction, of the follicles was present, and the majority showed perifollicular lymphocytic bulbitis at or near the isthmus region. No sebaceous glands were present, except in the “normal” biopsy. Overall, it appeared that cell-mediated destruction was approximately at the level of the sebaceous ducts. The final diagnosis was superficial lymphocytic dermatitis with subtotal destruction and absence of sebaceous glands (sebaceous adenitis) and secondary telogenization of follicles with severe surface hyperkeratinization.

Figure 2.

Histopathologic evidence of lymphoid destruction of a sebaceous gland duct (arrow).

This is the first reported case of sebaceous adenitis in a horse; however, 2 histologically similar equine cases have been documented at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine over the past 14 y (Edward Clark, personal communication). Despite its rarity in horses, sebaceous adenitis has been reported in several breeds of dogs and, sporadically, in rabbits and cats (2–4).

Sebaceous adenitis was first described as a rare, idiopathic dermatosis of young to middle-aged dogs in the late 1980s. Recently, an immunemediated component has been postulated (5), but the condition is likely multifactorial in nature. Vizslas, Akitas, standard poodles, and Samoyeds appear to be predisposed, but cases in various other breeds have been reported (5–7,9,10). There appears to be no sex predilection; however, an autosomal recessive hereditary basis has been determined in Akitas (5) and standard poodles (6).

In dogs, sebaceous adenitis appears clinically as 2 different chronically progressive forms and blood analysis generally reveals no significant abnormalities. The Akita, however, may show signs of systemic illness, such as fever, malaise, and weight loss (7,8). In short-coated breeds, such as the vizsla, lesions include symmetric multifocal areas of alopecia (“moth-eaten” appearance) and adherent white scales beginning on the head and ears and disseminating to the trunk. In longer-coated dogs, such as Akitas and standard poodles, generalized alopecia with erythema and yellow-brown keratosebaceous secretions occur (9,10). Lesions are usually not pruritic or painful, unless complicated by secondary folliculitis.

Histopathologic examination typically demonstrates a periadnexal pattern of granulomatous inflammation, primarily directed at the sebaceous glands (10). As the disease progresses, the sebaceous glands are destroyed, whereas the hair follicles remain normal. In advanced cases, however, perifollicular fibrosis of the isthmus region and follicular atrophy can occur (10). Other histological findings may include orthohyperkeratosis, acanthosis, irregular epidermal hyperplasia, vascular dilatation, and perivascular cuffing of superficial dermal vessels (10).

Sebaceous adenitis in rabbits appears as chronic progressive nonpruritic scaling of the face and neck, proceeding to a generalized exfoliative dermatosis with alopecia and leukoderma (4). Skin biopsies of affected areas may reveal an absence of sebaceous glands, perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate at the level of the absent sebaceous glands, a mural infiltrative lymphocytic folliculitis, orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, and follicular dystrophy with perifollicular fibrosis. A mild, mononuclear interface dermatitis may also be seen (4).

In the cat, sebaceous adenitis manifests itself as chronic progressive, nonpruritic patches of scaling, crusting, alopecia, and skin depigmentation of the head, neck, and trunk (2,3). Histopathologic examination reveals pyogranulomatous perifolliculitis with the absence of sebaceous glands, along with orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. In 1 report, a short-haired cat’s condition remained stable for 18 mo without systemic involvement (3), yet in another report, a Persian-cross cat showed marked signs of systemic involvement, such as a leukocytosis, enlarged popliteal lymph nodes, depression, and weight loss (2).

Prognosis for recovery of sebaceous adenitis is fair to guarded, depending on the level of destruction and regeneration of the sebaceous glands. The disease demands long-term treatment with immunosuppressive agents and combinations of topical and oral supplements, as well as treatment of secondary folliculitis, if it is present. Supplemental options include topical propylene glycol sprays, oral essential fatty acids, vitamin A, sunflower oil, topical antiseborrheic shampoos, and moisturizing emollient rinses. These initial treatments should be tried for at least 2 mo before considering them ineffective (8). The next step typically involves treatment with synthetic retinoids or cyclosporines. Sebaceous adenitis in dogs is generally refractory to immunosuppressive doses of corticosteroids (8). In the rabbit and cat, immunosuppressive treatment with corticosteroids has resulted in only a transient improvement of skin lesions and there has been no response to topical propylene glycol sprays, essential fatty acid capsules, or synthetic retinoids (2–4).

This case demonstrates many similar clinical and histopathological characteristics of sebaceous adenitis in other species; however, diseases such as this, where the pathogenesis is not entirely understood, are unpredictable. The leukoderma was similar to that in cases reported in rabbits and cats (2–4), but it was more dramatic than that reported in dogs (5–9). Retrospectively, performing diagnostic tests such as bacteriologic culture, mycologic studies, or deep skin scrapings would have been ideal to rule out other differential diagnoses before taking biopsies and histopathologic examination as a definitive diagnosis. In this case, the lesions improved spontaneously without treatment, coinciding with simultaneous regression of the sarcoid on the neck 4 mo later. This may be postulated as an alteration in immune stimulation, suggesting an immunemediated basis. Follow-up biopsies were not obtained, but they would have been useful in understanding the progression of the disease and recovery. Treatment in the horse may be extrapolated from other species with sebaceous adenitis, but little is known of the prognosis for recovery in the horse, with the exception of this case. Overall, sebaceous adenitis should be considered as a differential diagnosis in systemically healthy horses presenting with a chronic progressive history of multifocal nonpruritic scaling, crusting, alopecia, and leukoderma of the face, becoming generalized over time.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Drs. K. Lohmann, J. Carmalt, T. Clark, and L. Petrie for their guidance and advice on this case. CVJ

Footnotes

Dr. Osborne’s current mailing address is Strathmore Veterinary Clinic, 43 Spruce Lane, Strathmore, Alberta T1P 1J6.

Dr. Osborne will receive 50 free reprints of her article, courtesy of The Canadian Veterinary Journal.

References

- 1.Scott DW, Miller WH Jr. Equine Dermatology. St. Louis: WB Saunders, 2003.

- 2.Wendlberger U. Sebadenitis bei einer Katze. Kleintiepraxis. 1999;44:293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott DN. Adenite sebacee pyogranulomateuse sterile chez un chat. Pointe Vet. 1989;21:107–11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.White SD, Linder KE, Schultheiss P, et al. Case report: Sebaceous adenitis in four domestic rabbits (Oryctatagus cuniculus) Vet Dermatol. 2000;11:53–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3164.2000.00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichler IM, Hauser B, Schiller I, et al. Sebaceous adenitis in the Akita: clinical observations, histopathology and heredity. Vet Dermatol. 2001;12:243–53. doi: 10.1046/j.0959-4493.2001.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunstan RW, Hargis AM. The diagnosis of sebaceous adenitis in standard poodle dogs. In: Kirk RW, ed. Current Veterinary Therapy XII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 1995:619–22.

- 7.Scott DW. Sterile granulomatous adenitis in dogs and cats. Vet Annu. 1993;33:236–43. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonagura J, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XIII Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2000:572–573.

- 9.Rosser EJ, Dunstan RW, Breen PT, Johnson GR. Sebaceous adenitis with hyperkeratosis in the standard poodle: a discussion of 10 cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1987;23:341–345. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart LJ. Advances in clinical dermatology. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1990;20:1607–1608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]