Abstract

Fifth-graders' (N = 162; 93 girls) relationships with parents and friends were examined with respect to their main and interactive effects on psychosocial functioning. Participants reported on parental support, the quality of their best friendships, self-worth, and perceptions of social competence. Peers reported on aggression, shyness and withdrawal, and rejection and victimization. Mothers reported on psychological adjustment. Perceived parental support and friendship quality predicted higher global self-worth and social competence and less internalizing problems. Perceived parental support predicted fewer externalizing problems, and paternal (not maternal) support predicted lower rejection and victimization. Friendship quality predicted lower rejection and victimization for only girls. Having a supportive mother protected boys from the effects of low-quality friendships on their perceived social competence. High friendship quality buffered the effects of low maternal support on girls' internalizing difficulties.

Keywords: friendship, parent-child relationships, attachment, social withdrawal, aggression

From the earliest years of childhood, children develop significant relationships with family members and, with increasing age, their peers. Over the years, researchers have examined the influence that children's experiences with these relationships may have on their functioning. Links have been established between parent-child relationship quality and adjustment during the pre-, elementary, and middle school years as well as later adolescence (see Rubin & Burgess, 2002, for a relevant review). Likewise, aspects of children's peer relationships and friendships have been associated with psychosocial functioning. Recently, researchers have examined relations between relationship systems and the manner in which experiences in both familial and extrafamilial relationships may interact to influence psychosocial functioning. The focus of this study was on parent-youth adolescent and friendship relationships and whether and how friendships serve to moderate the association between parent-adolescent relationship quality and psychosocial functioning.

An Attachment Framework

Although there are a number of ways in which relationships with parents may influence relationships with friends and psychosocial functioning, our framework in the present study is based on premises drawn from attachment theory. According to attachment theorists, the child who receives responsive and sensitive parenting from the primary caregiver forms an internal working model of that caregiver as trustworthy and dependable when needed and develops a model of the self as someone who is worthy of such care (Bowlby, 1973, 1982). Through experience with a responsive and sensitive caregiver, the child learns reciprocity in social interactions (Elicker, Englund, & Sroufe, 1992) and a set of specific social skills that can be used in relationships that extend beyond the child-caregiver relationship. Also, the securely attached child is able to use the caregiver as a secure base for exploration (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978), including the exploration of relationships with peers. Thus, although links between attachment security and social competence with peers are theoretically meaningful, there is a compelling rationale for the link between attachment security and friendship. In particular, parent-child relationship quality engenders a set of internalized relationship expectations that affect the quality of friendships with peers (Belsky & Cassidy, 1994; Youngblade & Belsky, 1992).

Children whose parental care experiences lead to insecure attachment are considered to be at risk for maladjustment (Burgess, Marshall, Rubin, & Fox, 2003; Greenberg, Speltz, & DeKlyen, 1993). Although the links between attachment and maladaptive behaviors are not well understood, there are a number of possible mechanisms. Insecure models characterized by anger, mistrust, and fear (Bretherton, 1985) as well as negative attribution biases (Dodge & Newman, 1981) may lead insecurely attached children to behave aggressively. Emotion-regulation difficulties, which could be a potential consequence of insecure attachment (Cassidy, 1994; Thompson, 1994), might also lead to behavior problems. In addition, feelings of insecurity and of the self as unworthy may lead to internalizing problems (Granot & Mayseless, 2001) and to feelings of loneliness and social isolation (Kerns, Klepac, & Cole, 1996).

Attachment relationships and social competence

Researchers have shown that securely attached toddlers are more sociable and positively oriented toward unfamiliar peers than toddlers with insecure attachments (Pastor, 1981). Also, early secure attachment predicts social competence in the preschool years (Booth, Rose-Krasnor, & Rubin, 1991; Howes, Matheson, & Hamilton, 1994; Rose-Krasnor, Rubin, Booth, & Coplan, 1996). However, insecure attachment relationships in infancy and early childhood predict (a) being victimized (Troy & Sroufe, 1987), (b) the frequent display of negative affect (LaFreniere & Sroufe, 1985), and (c) less frequent social participation and less dominant behavior (LaFreniere & Sroufe, 1985). Moreover, insecure, unsupportive parent-child relationships predict teacher-rated passive withdrawal and aggression in early elementary school (Renken, Egeland, Marvinney, Mangelsdorf, & Sroufe, 1989).

Researchers have also found that secure parent-child relationships during the elementary school years are concurrently related to social competence. For example, Cohn (1990) reported that 6-year-old, insecurely attached boys were less liked and perceived to be more aggressive by their classmates than securely attached boys were. Kerns et al. (1996) noted that securely attached fifth-graders were more accepted by their peers, whereas Granot and Mayseless (2001) found that insecurely attached fourth- and fifth-graders were more rejected by peers. Finally, Finnegan, Hodges, and Perry (1996) found that third-grade to seventh-grade boys who reported greater use of preoccupied (i.e., insecure-ambivalent) coping strategies with their attachment figure when faced with everyday stressors requiring emotion regulation were more likely nominated by their peers as immature and victimized and used a hovering peer entry style.

Attachment and psychosocial adjustment

Children who feel secure and supported by their primary caregivers have been shown to have higher levels of perceived competence in multiple domains (Kerns et al., 1996), have higher self-esteem (Simons, Paternite, & Shore, 2001) and feel less lonely (Kerns et al., 1996). Furthermore, relatively lower security has been associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems (Granot & Mayseless, 2001; McCartney, Owen, Booth, Clarke-Stewart, & Vandell, 2003). The quality of the child-parent attachment relationship has been linked with social competence and adjustment and maladjustment from early childhood through adolescence. As the child matures, however, relationships outside of the home, specifically their friendships, may influence adjustment directly and indeed, moderate the relations between parent-child attachment and adjustment.

Attachment and friendship

Aspects of the early parent-child relationship, including security of attachment, have been shown to predict competence in forming close friendships at 10 years of age such that children who had positive early relationships with their parents were more likely to have a close friend at age 10 (Freitag, Belsky, Grossmann, Grossmann, & Scheurer-Englisch, 1996). Also, secure mother-infant attachment predicts positive qualities of 5-year-olds' friendships (Elicker et al., 1992; Krollmann & Krappmann, 1996; Park & Waters, 1989). Father-infant attachment security, however, has been shown to be negatively related to 5-year-olds' positive friendship qualities, suggesting to some that children with less secure attachments to their parents may actively seek more emotionally satisfying relationships with peers and, conversely, that children with secure attachments may not need to seek support from peers (Youngblade & Belsky, 1992). Finally, secure attachment in late childhood and early adolescence is associated positively with the number of reciprocated classroom friendships that children have (Kerns et al., 1996) and positive qualities of children's close peer relationships (Lieberman, Doyle, & Markiewicz, 1999).

FRIENDSHIP

Friends are thought to have a strong impact on adjustment during pre-adolescence (Sullivan, 1953). Perhaps this is the result of children's growing need, during this period, for acceptance in their peer groups. During the early adolescent period, friendship is thought to serve numerous functions, including the provision of intimacy, security, and trust; instrumental aid; and norm teaching (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 1998). Thus, forming and maintaining strong, qualitatively rich friendships becomes of central importance during late childhood and adolescence. Researchers have shown that with age, children become increasingly reliant on friends for support (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). Because the provisions offered by friendship become increasingly important during this late childhood and early adolescent period, it seems likely that the quality of friendship must have some bearing on children's psychosocial adjustment.

Friendship and psychosocial adjustment

Despite the putative significance of friendship during early adolescence, much of what is known about the phenomenon derives from studies of young children. Thus, children who perceive higher levels of warmth in their friendships show lower levels of behavioral conduct problems and depression as well as higher levels of self-worth (Stocker, 1994). Furthermore, high-quality early elementary school friendships are associated with success and happiness in school (Ladd, Kochenderfer, & Coleman, 1996).

In middle childhood, friendship quality is associated negatively with loneliness and positively with self-regard (Parker & Asher, 1993). Having high-quality friendships is also related positively to peer-assessed sociability and leadership (Berndt, Hawkins, & Jiao, 1999) and to higher involvement in school (Berndt & Keefe, 1995). Among a sample of shy children, Fordham and Stevenson-Hinde (1999) found that friendship quality was correlated with higher global self-worth, higher perceptions of classmate support, and lower trait anxiety. In this latter regard, friendship was viewed as a buffer or moderator of the relation between dispositionally based shyness and negative outcomes. The long-term influence of friendship quality in early adolescence has also been demonstrated in a 12-year longitudinal study by Bagwell, Newcomb, and Bukowski (1998). These researchers found that adolescents without friends, compared to those with friends, had lower self-esteem and more psychopathological symptoms in adulthood.

Interaction of Attachment and Friendship

Given the significance of both parent-child relationships and friendships in early adolescence, one may speculate that these relationships interact in meaningful ways to predict adjustment. Thus, parent-adolescent relationship and friendship processes may be associated with psychosocial functioningin at least three ways. First, each may make an independent, unique contribution to predicting adjustment outcomes. Second, the parent-adolescent relationship may provide the basis for the formation of friendships, which in turn are related to psychosocial adjustment. Third, the relation between the parent-adolescent relationship and functioning may be moderated by friendship quality. According to Bowlby (1973), adjustment at any particular stage is the result of the interaction of the individual's past experiences with current relationships in the larger social environment. Therefore, the early parent-adolescent relationship and friendship experiences may interact with each other to influence psychosocial functioning. Specifically, a high-quality friendship may buffer the impact of a qualitatively poor parent-adolescent relationship (Booth, Rubin, & Rose-Krasnor, 1998). We do not suggest that only one of these models is the correct model. Rather, it is more likely that all three processes take place to varying degrees. The goal of the present study was to examine the moderating model of the impact of friendship on the relation between attachment and adjustment.

Surprisingly little research has been conducted with this goal in mind, but some investigators have attempted to examine the interaction between early home environment and friendships. Schwartz, Dodge, Pettit, and Bates (2000), for example, examined whether early harsh home environment and number of a children's friendships predicted peer victimization. They found that children who experienced harsh home environments in the preschool years were more likely to be victimized by peers in the third and fourth grades; however, this correlation was stronger for those who had a lower number of friendships. Overall, early harsh environment did not predict victimization for children who reported having many friendships. More recently, Criss, Pettit, Bates, Dodge, and Lapp (2002) explored the role of children's peer relationships in the link between family adversity and child externalizing problems and found that family adversity and externalizing behaviors were not related for children who had a large friendship network.

Laible, Carlo, and Raffaelli (2000) investigated the differential and interactive relations between parent and peer attachment and adolescent adjustment. Middle school and high school children reported the degree of trust, communication, and alienation perceived in their relationships with their parents (particularly the one who influenced them the most) and friends. Adolescents who perceived their relationships with both parents and peers to be more secure were the best adjusted, reporting lower levels of aggression and depression and more sympathy. Those who perceived their parent and peer relationships to be less secure were the least well adjusted. It was also found that adolescents with a secure attachment to peers but an insecure attachment to their parents were significantly better adjusted than those with an insecure attachment to peers but a secure attachment to parents. Although both attachments served similar functions for adjustment, the findings suggest that peer attachment may become more influential than parent attachment during adolescence.

Importantly, adolescents in the above study were asked about their friends in general, rather than a close friend in particular. Although close friendships may be considered affectional bonds and even attachments, in either case, it is the function of the specific relationship that is of particular interest within an attachment framework (Ainsworth, 1985). Thus, we examined the moderating impact of specific close friendship relationships on the association between adolescents' internal working models of their relationships with their parents and their own psychological well-being. We also examined these relations among younger adolescents to determine if experiences in high-quality friendships buffer the impact of insecure attachment even at younger ages and when friends are unlikely to serve as attachment figures. Finally, in almost all studies on this topic, the relevant parent has been the mother, and far less is known about fathers' specific parenting styles or the mechanisms involved in linking fathering to young adolescents' adjustment (Parke, 2002). Moreover, virtually nothing is known about the putative influence of father-child attachment among older children and adolescents. For these reasons, we examined the independent contributions of both perceived maternal and paternal support in the prediction of adjustment and maladjustment.

To advance beyond the knowledge base described above, we examined whether the quality of early adolescent friendship moderates the parent-adolescent relationship regarding the prediction of adjustment and maladjustment. Specifically, we predicted that fifth-graders whose relationships with their mothers and fathers were viewed as affectively positive, nurturant, and supportive would be more socially competent, have more positive self-regard, and show fewer problems of an internalizing or externalizing nature than young adolescents with poorer quality relationships with their parents would. Furthermore, we predicted that the quality of the best friend relationship would be positively associated with social competence and self-regard and negatively with both internalizing and externalizing problems. That is, for young adolescents who viewed their best friendship as supportive and trustworthy, positive outcomes would be evinced. Last, we posited that friendship would serve as a moderator to protect young adolescents with relatively poor parent-child relationships from negative outcomes. We also examined the main and interactive effects of both parent and child gender. Attachment theory suggests that children form separate internal working models based on experiences within different attachment relationships (Bowlby, 1982). However, the organization and influence of divergent representations have not yet been explicated. Howes (1999) has summarized the alternative organizations as (a) a hierarchical organization in which the most salient caregiver (usually the mother) is most influential, (b) an integrative organization in which the child integrates the various representations to form a single internal working model (and no relationship is more salient than any other), and (c) an independent organization in which the various attachments are differentially influential for different developmental domains. There is little empirical evidence to date regarding which model best represents the organization of divergent representations. Moreover, developmental advances allow older children and adolescents to compare relationships to one another as well as to a hypothetical ideal, and issues of autonomy and relatedness arising during adolescence may affect the roles of attachment figures. But given little empirical evidence on which to base parent gender hypotheses, our analyses regarding parent gender were strictly exploratory.

However, we did have hypotheses regarding adolescent gender. Although there was no reason to suspect that parent-adolescent attachment would have differential effects on boys' and girls' adjustment, there is evidence in the friendship literature to suggest that girls may have more intimate relationships with their friends than boys do (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Sharabany, Gershoni, & Hofman, 1981) and that girls may be more strongly affected than boys by tensions and strains in their best friendships (Clark & Ayers, 1992); as such, girls may be more influenced by close friendships than boys are. Thus, we hypothesized that girls would benefit more than boys from high-quality friendship relationships overall as well as in the context of qualitatively poor relationships with parents.

METHOD

Participants

Participants were drawn from a larger sample of fifth-grade students (N = 828; 421 girls). All students with parental consent (consent rate = 84%) in 39 classrooms across eight public elementary schools in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area completed the school assessments, which included friendship nominations and a measure of peer-nominated behavioral status (described below). Based on mutuality of friendships and behavioral status, pairs of students were invited to visit the university and completed an additional battery of questionnaires, including those related to the present study. The mothers of these students also completed a number of questionnaires. The sample described in this study (N = 162; 93 girls) is made up of those young adolescents in this selected laboratory sample who had complete data relevant to this study. Thirty-nine young adolescents in the present sample were classified as aggressive (14 boys, 25 girls), 34 as shy and withdrawn (15 boys, 19 girls), 13 as both aggressive and withdrawn (5 boys, 8 girls), and 76 as nonaggressive and nonwithdrawn (35 boys, 41 girls).

Demographic data were collected only from the laboratory sample. Of these, 10 young adolescents were missing mother-reported demographic data because their mothers did not return the questionnaire or did not speak English. The mean age was 10.33 (SD = .52); the mean age of boys was 10.34 (SD = .49), and the mean age of girls was 10.33 (SD = .56). Approximately 60% of the children were White, 15% Black, 15% Asian, and 10% Latino. Sixty-eight percent of the mothers (68% of the fathers) had a university degree, 21% had some college education (13% of the fathers), and 9% had high school and vocational education (12% of the fathers). Seventy-two percent of the adolescents lived with both of their biological or adoptive parents.Demographic information was not collected from the students who only participated in the school assessments.

Procedures and Measures: School Assessments

All 828 participants completed questionnaires regarding friendship nominations and peer-nominated behavioral status in the fall of their fifth-grade year. Research assistants administered two questionnaires in group format in the classrooms. Each session lasted approximately 1 hour. The first questionnaire involved friendship nominations, and the second questionnaire was a modification of the Revised Class Play (RCP; Masten, Morison, & Pellegrini, 1985).

Friendship nominations

For friendship nominations (Bukowski, Hoza, & Boivin, 1994), participants were asked to write the names of their very best friend and their second best friend at their school. Young adolescents could only name same-sex best friends, and only mutual (reciprocated) best friendships were subsequently considered. Young adolescents were considered best friends if they were each other's very best or second best friend choice. The identification of a best friendship is similar to procedures used in other studies focused on best friendships (Parker & Asher, 1993).

Child behaviors—Extended Class Play (ECP)

Following completion of the friendship nomination questionnaire, participants completed a modified version of the RCP (Masten et al., 1985). The young adolescents were instructed to pretend to be the directors of an imaginary class play and to nominate their classmates for various positive and negative roles. The young adolescents were provided with a list of their classmates who were participating in the study and were instructed to choose one boy and one girl for each role, but the same person could be selected for more than one role. Only nominations for participants with consent were considered. All item scores were standardized within each sex and within each classroom to adjust for the number of nominations received and the number of nominators. Items were added to the original RCP to more fully capture different types of aggression (e.g., “someone who spreads rumors”) and to better distinguish between peer rejection and victimization, and active isolation or social withdrawal (e.g., “someone who likes spending time alone”). A principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation yielded five orthogonal factors: aggression, shyness and withdrawal, rejection and victimization, prosocial behavior, and popularity and sociability. The standardized item scores were summed to yield five different total scores for each participant. It should be noted that the ECP (Burgess, Rubin, Wojslawowicz, Rose-Krasnor, & Booth, 2003) measure has been found both valid and reliable using a large normative sample of fifth-grade children across three time points (Burgess et al., 2003, April).

Procedures and Measures: Laboratory Visits

Based on the existence of mutually nominated friendships and peer-nominated behaviors, selected pairs of young adolescents were invited to the Laboratory for the Study of Child and Family Relationships at the University of Maryland in the spring of their fifth-grade year. During this visit, the young adolescents completed a number of questionnaires, as did the mothers. If mothers did not accompany their child to the laboratory for the friend visit, they were asked to complete a set of questionnaires at home. Measures completed by mothers and children are described below.

Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI)

The NRI (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985) was used in this study to assess young adolescents' perceptions of maternal and paternal support and relationship provisions. In this regard, the NRI was used as a proxy measure of the young adolescents' internal working model of the child-parent attachment relationship. The 30-item NRI comprises 10 conceptually distinct subscales that load onto two factors (Furman, 1996): (a) support (affection, admiration, instrumental aid, companionship, intimacy, nurturance, and reliable alliance) and (b) negativity (antagonism and conflict). Only the support subscale was used herein. The NRI subscales have adequate internal reliability across gender, ethnic, and adolescent age groups (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). It is noteworthy that for one half of the current sample, Security Scale (Kerns et al., 1996) data were available. These data assessed children's perceptions of security in their relationships with both their mothers and their fathers. The correlation between the maternal NRI support scale and the maternal Security Scale was r(73) = .65, with p < .001; the correlation between measures for fathers was r(68) = .66, with p < .001. Given that we had a much larger number of participants for whom NRI data were available and given the strong correlations between the NRI and the Security Scale, the NRI was used as an index of perceived parental support and security.

The Friendship Quality Questionnaire–Revised (FQQ; Parker & Asher, 1989) was used to assess the young adolescents' self-perceived quality of friendship with their best friend. The FQQ yields six subscales in the areas of companionship and recreation, validation and caring, help and guidance, intimate disclosure, conflict and betrayal, and conflict resolution (alpha = .73 to .90); higher scores indicated greater perceived friendship quality on all of the subscales. Given the strong correlations between the FQQ subscales (range of r = .36 to r = .74) and given procedures followed by Parker and Asher (1989), only the total FQQ score was used in this study.

Finally, the Self Perception Profile for Children (Harter, 1985) was used to assess the young adolescents' perception of self and self in relation to peers. The measure yields six subscales in the areas of scholastic competence, social acceptance, athletic competence, physical appearance, behavioral conduct, and global self-worth. Previous research has demonstrated the reliability and validity of each of these measures (Harter 1982, 1985). Of particular interest in the present study were children's perceptions of their own competence in the social domain as well as their general self-worth. Accordingly, although the measure was administered in its entirety, only scores for social perceived competence (alpha = .82) and general self-worth (alpha = .80) were considered in data analyses.

In addition to the measures completed by the young adolescents, mothers were asked to complete the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL: Achenbach, 1991). This 118-item checklist assesses adjustment and maladjustment in children. The CBCL yields eight narrow-band factors (e.g., hyperactivity, aggression, social withdrawal, depression) that are further reduced to two broadband factors: internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. The reliability and validity of the CBCL have been demonstrated in numerous studies (Achenbach, 1991). A small number of items were dropped from the original questionnaire (e.g., “thinks about sex too much”) to reduce potential difficulties with parents. The alpha for the internalizing scale was .82, and the alpha for the modified externalizing scale was .84. The prevalence of internalizing and externalizing behavior problems were of particular interest in this study. Total raw scores for each CBCL broadband factor (internalizing and externalizing) were used in all analyses.

Aggregated Variables

To reduce the number of criterion variables and still capitalize on multiple informants, conceptually based indices of externalizing and aggression, and internalizing and shyness and withdrawal were formed. Although maternal reports of externalizing difficulties and peer-nominated aggression were not strongly correlated with one another, we chose to aggregate the two measures to create an index such that children receiving the highest scores would be those young adolescents who were reported by both their mothers and their peers as aggressive. Thus, an index of externalizing difficulties and aggression was formed by standardizing and aggregating the scores of the mother-rated externalizing difficulties (CBCL) and peer-nominated aggression (ECP) measures (the correlation between measures was r(144) = .12, with p = .07). Similarly, an index of internalizing difficulties and shyness and withdrawal was formed by standardizing and aggregating the scores of the mother-rated internalizing difficulties (CBCL) and peer-nominated shyness and withdrawal (ECP) measures (the correlation between measures was r(144) = .37, with p < .01).

RESULTS

Results of this investigation are reported in several sections. In the first section, descriptive statistics for the sample are presented, the need for covariates in the main analyses is investigated, and initial correlation analyses are provided. The main research questions of this study are addressed in the subsequent five sections, in which we present analyses of the independent and moderating relations among parental support and perceived friendship quality in the prediction of psychosocial adjustment.

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics on all predictor and criterion variables for the whole sample and for boys and girls separately are shown in Table 1. Participants reported receiving fairly high levels of support from both their mothers and fathers and perceived their friendships to be of fairly high quality. In terms of outcomes, the sample was relatively well adjusted. However, each of the predictor and criterion measures had an acceptable range and variance. Sample sizes varied to a small degree across measures because of missing data. Specifically, 18 young adolescents were missing mother-reported data because their mothers did not return the questionnaire, completed it incorrectly, or did not speak English. We conducted t tests to determine whether sex of the child should be included as a predictor in the regression analyses. As seen in Table 1, boys reported significantly higher levels of support from their fathers than girls did; girls reported significantly higher quality friendships than boys did. Boys and girls did not differ significantly on any of the criterion measures. Gender was entered as a main effect in the regression analyses, as were interactions between gender and attachment and friendship quality. The inter-correlations among the study variables are presented for the whole sample and separately for boys and girls in Table 2. Regarding predictors, perceptions of maternal and paternal support were moderately to strongly correlated, especially for boys. Although several of the criterion variables were strongly intercorrelated, all were retained for regression analyses either because the magnitude of the correlations differed for boys and girls or they were based on conceptual differences.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Predictor and Criterion Variables for All Adolescents and Separately for Boys and Girls

| Overall |

Boys |

Girls |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | X | SD | X | SD | X | SD | t | df |

| Perceived maternal support | 162 | 4.25 | 0.54 | 4.24 | 0.47 | 4.26 | 0.58 | −0.20 | 158.92 |

| Perceived paternal support | 162 | 4.03 | 0.74 | 4.16 | 0.62 | 3.94 | 0.80 | 1.97* | 159.67 |

| Perceived friendship quality | 162 | 4.00 | 0.62 | 3.85 | 0.65 | 4.11 | 0.57 | −2.61** | 134.50 |

| Global self-worth | 162 | 3.43 | 0.60 | 3.52 | 0.58 | 3.36 | 0.61 | 1.70 | 150.77 |

| Perceived social competence | 162 | 3.18 | 0.66 | 3.21 | 0.70 | 3.16 | 0.64 | 0.44 | 139.02 |

| Internalizing problems | 144 | −0.01 | 0.84 | −0.11 | 0.70 | 0.07 | 0.93 | −1.35 | 141.90 |

| Externalizing problems | 144 | −0.02 | 0.73 | −0.05 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.70 | −0.41 | 126.62 |

| Peer-nominated rejection and victimization | 162 | −0.12 | 0.82 | −0.16 | 0.77 | −0.09 | 0.85 | −0.51 | 153.31 |

NOTE: Maternal and paternal support are derived from the Network of Relationships Inventory. Perceived friendship quality is a composite variable formed from the Friendship Quality Questionnaire–Revised subscales of companionship and recreation, validation and caring, help and guidance, intimate disclosure, and conflict resolution. Global self-worth and perceived social competence are derived from the Harter SPPC. Internalizing problems is a composite of mother-reported internalizing behavior and peer-nominated shyness and withdrawal; externalizing problems is a composite of mother-reported externalizing behavior and peer-nominated aggression. Mother-reported internalizing and externalizing behavior are the broadband scales of the Child Behavior Checklist. Peer-nominated behaviors are the average standardized proportion of nominations (within sex and classroom) received for behavioral descriptions of aggression, shyness and withdrawal, and rejection and victimization.

p < .05.

p < .01.

TABLE 2.

Two-tailed Correlations Among Study Variables for the Entire Sample and Separately for Boys and Girls

| Perceived Maternal Support | Perceived Paternal Support | Friendship Quality | Global Self-Worth | Perceived Social Competence | Internalizing and Shyness and Withdrawal | Externalizing and Aggression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire sample | |||||||

| Perceived paternal support | .45** | ||||||

| Friendship quality | .35** | .33** | |||||

| Global self-worth | .23** | .34** | .34** | ||||

| Perceived social competence | .23** | .32** | .40** | .53** | |||

| Internalizing and shyness and withdrawal | −.24** | −.20* | −.24** | −.24** | −.46** | ||

| Externalizing and aggression | −.22** | −.33** | −.15 | −.16 | −.04 | .13 | |

| ECP rejection and victimization | −.08 | −.20* | −.28** | −.31** | −.35** | .57** | .24** |

| Boys only | |||||||

| Perceived paternal support | .58** | ||||||

| Friendship quality | .27* | .28* | |||||

| Global self-worth | .19 | .17 | .27* | ||||

| Perceived social competence | .28* | .24* | .43** | .57** | |||

| Internalizing and shyness and withdrawal | −.25 | −.19 | −.32* | −.20 | −.50** | ||

| Externalizing and aggression | −.17 | −.27* | −.28* | −.18 | −.09 | .20 | |

| ECP rejection and victimization | −.06 | −.11 | −.14 | .01 | −.33** | .73** | .24 |

| Girls only | |||||||

| Perceived paternal support | .41** | ||||||

| Friendship quality | .42** | .44** | |||||

| Global self-worth | .27** | .42** | .47** | ||||

| Perceived social competence | .20 | .38** | .41** | .50** | |||

| Internalizing and shyness and withdrawal | −.26* | −.18 | −.28* | −.26* | −.44** | ||

| Externalizing and aggression | −.28* | −.38** | −.06 | −.13 | .02 | .08 | |

| ECP rejection and victimization | −.09 | −.24* | −.42** | −.50** | −.36** | .48** | .24* |

NOTE: ECP = Extended Class Play. Two-tailed correlations are reported to be conservative based on the number of tests conducted.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Overview of Predictive Analyses

Two series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted: One series included perceived maternal support as a predictor, and the other series perceived paternal support. Within each set of analyses, separate regression analyses were performed to predict global self-worth, perceived social competence, internalizing problems, externalizing problems, and peer rejection and victimization. The first set of analyses included young adolescents' gender, perceived maternal support (NRI), positive friendship quality (FQQ), the interactions of sex with maternal support and friendship quality, and the three-way interaction of sex with both maternal support and friendship quality as predictors. The second set replaced perceived maternal support with perceived paternal support. Gender was coded as 1 = male and 2 = female. The support and friendship quality variables were centered on their means before forming interactions. All predictor variables (including interaction terms) were entered as separate steps to identify the independent contributions of (i.e., the variance accounted for by) each main effect and the independent contributions of the interaction effects after controlling for the main effects.

Self-Esteem and Self-Perceptions

As indicated in Tables 3 and 4, results of regression analyses revealed both significant main effects and several interaction effects for perceived parental support and perceived friendship quality. The overall regression predicting global self-worth from gender, perceived maternal support, and perceived friendship quality was significant, F(7, 154) = 6.08, p < .01, as was the overall regression predicting global self-worth from paternal support and perceived friendship quality, F(7, 154) = 7.22, p < .01. As noted in Table 3, perceived maternal and paternal support, as well as the quality of friendship, was a significant predictor of global self-worth. In both analyses, the three-way interaction of gender, parental support, and friendship quality approached but did not reach statistical significance.

TABLE 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Global Self-Worth From Perceived Maternal and Paternal Support and Perceived Friendship Quality (N = 162)

| Predictors | B | SE | β | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived maternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | −.16 | .10 | −.13† | .02† |

| Perceived maternal support | .26 | .08 | .24** | .06** |

| Perceived friendship quality | .34 | .08 | .35** | .10** |

| Gender × Support | .04 | .17 | .06 | .00 |

| Gender × Friendship quality | .26 | .15 | .42† | .02† |

| Support × Friendship quality | .17 | .11 | .12 | .01 |

| Gender × Support × Friendship quality | .41 | .23 | .51† | .02† |

| Perceived Paternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | −.16 | .10 | −.13 | .02† |

| Perceived paternal support | .27 | .06 | .33** | .11** |

| Perceived friendship quality | .30 | .08 | .31** | .08** |

| Gender × Support | .15 | .13 | .33 | .01 |

| Gender × Friendship Quality | .17 | .15 | .28 | .01 |

| Support × Friendship Quality | .15 | .10 | .13 | .01 |

| Gender × Support × Friendship Quality | .38 | .20 | .58† | .02† |

NOTE: Each predictor was entered as a separate step.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

TABLE 4.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Perceived Social Competence From Perceived Maternal and Paternal Support and Perceived Friendship Quality (N = 162)

| Predictors | B | SE | β | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived maternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | −.05 | .10 | −.04 | .00 |

| Perceived maternal support | .28 | .10 | .23** | .05** |

| Perceived friendship quality | .42 | .08 | .40** | .13** |

| Gender × support | −.20 | .19 | −.28 | .01 |

| Gender × friendship quality | .03 | .17 | .04 | .00 |

| Support × friendship quality | .04 | .12 | .02 | .00 |

| Gender × support × friendship quality | .54 | .25 | .61* | .02* |

| Perceived paternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | −.05 | .10 | −.04 | .00 |

| Perceived paternal support | .29 | .07 | .32** | .10** |

| Perceived friendship quality | .38 | .08 | .36** | .11** |

| Gender × Support | .03 | .14 | .06 | .00 |

| Gender × Friendship Quality | −.09 | .17 | −.13 | .00 |

| Support × Friendship Quality | .02 | .10 | .02 | .00 |

| Gender × Support × Friendship Quality | .27 | .22 | .36 | .01 |

NOTE: Each predictor was entered as a separate step.

p < .05.

p < .01.

In terms of predicting perceived social competence, as indicated in Table 4, both overall regression equations were significant, F(7, 154) = 6.05, p < .01, for the regression with gender, perceived maternal support, and perceived friendship quality as predictors, and F(7, 154) = 6.14, p < .01, for the regression with gender, perceived paternal support, and perceived friendship quality as predictors. Both sets of analyses revealed positive and significant main effects for perceptions of parental support and friendship quality. However, after controlling for maternal support and friendship quality, a significant amount of the variance in perceived social competence was attributable to the three-way interaction of gender, maternal support, and friendship quality. This effect was not found for paternal support.

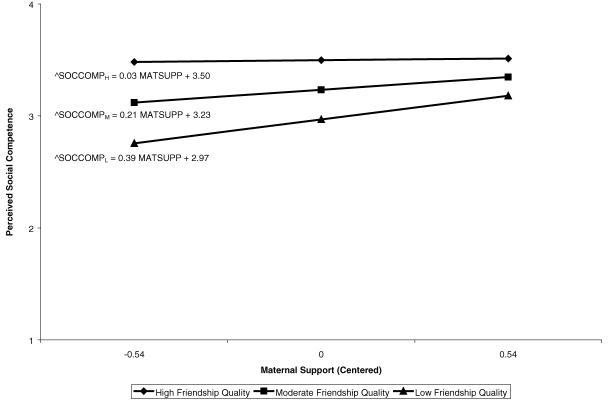

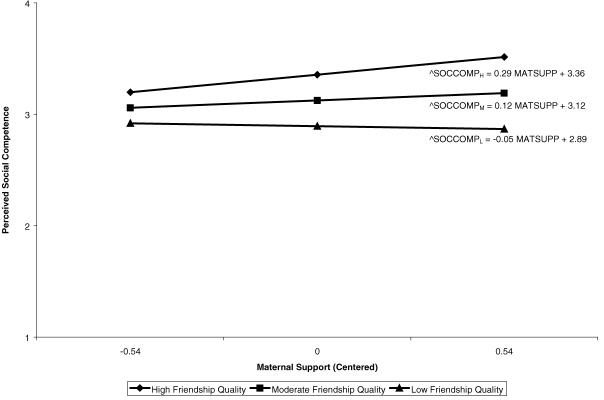

The significant interaction was probed following the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991). The regression equation was restructured to express the regression of perceived social competence on perceived maternal support at levels of friendship quality, separately for girls and boys. The values of perceived friendship quality chosen corresponded to the mean, one standard deviation above the mean, and one standard deviation below the mean. As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the strongest relation between perceived maternal support and perceived social competence was obtained for the boys who reported the lowest levels of friendship quality. The simple slope for the low friendship quality group was significantly different from zero (β = .27, p < .05), whereas the simple slopes for the average (mean) and high friendship quality groups were not significantly different from zero (β = .14, ns, and β = .04, ns, respectively). Thus, for boys, low maternal support coupled with low friendship quality was related to the lowest levels of perceived social competence, but at higher levels of maternal support, low friendship quality was not as detrimental in terms of perceived social competence. For boys with average or high quality friendships, the level of maternal support was not a significant factor in predicting perceived social competence. Looked at another way, at high-levels of perceived maternal support, friendship quality was not a significant factor in predicting perceived social competence. For girls in the high, average, and low friendship quality groups, the simple slopes were not significantly different from zero (β = .27, ns, β = .11, ns, and β = .04, ns, respectively).

Figure 1.

Predicting perceived social competence from maternal support and perceived friendship quality (boys only).

Figure 2.

Predicting social competence from maternal support and perceived friendship quality (girls only).

Internalizing Problems

The overall regression predicting the composite measure of internalizing problems from sex, perceived maternal support, and perceived friendship quality was significant, F(7, 136) = 4.58, p < .01, as was the overall regression predicting internalizing difficulties from gender, perceived paternal support, and perceived friendship quality, F(7, 136) = 2.34, p < .05. As indicated in Table 5, both sets of analyses revealed negative and significant main effects for perceptions of parental support and friendship quality. However, after controlling for maternal support and friendship quality, a significant amount of the variance in internalizing problems was attributable to the three-way interaction of gender, maternal support, and friendship quality. This was not the case for paternal support.

TABLE 5.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Internalizing Problems From Perceived Maternal and Paternal Support and Perceived Friendship Quality (N = 144)

| Predictors | B | SE | β | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived maternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | .18 | .14 | .11 | .01 |

| Perceived maternal support | −.45 | .15 | −.25** | .06** |

| Perceived friendship quality | −.33 | .12 | −.24** | .05** |

| Gender × Support | −.14 | .29 | −.13 | .00 |

| Gender × Friendship Quality | −.12 | .25 | −.13 | .00 |

| Support × Friendship Quality | .51 | .21 | .21* | .04* |

| Gender × Support × friendship Quality | .99 | .44 | .56* | .03* |

| Perceived paternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | .18 | .14 | .11 | .01 |

| Perceived paternal support | −.23 | .10 | −.19* | .03* |

| Perceived friendship quality | −.36 | .12 | −.26** | .06** |

| Gender × Support | −.05 | .20 | −.07 | .00 |

| Gender × Friendship Quality | −.16 | .25 | −.18 | .00 |

| Support × Friendship Quality | .11 | .16 | .06 | .00 |

| Gender × Support × Friendship Quality | −.02 | .33 | −.01 | .00 |

NOTE: Each predictor was entered as a separate step.

p < .05.

p < .01.

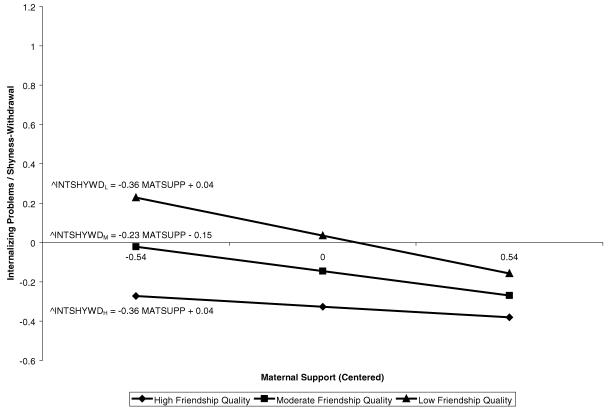

Again, the above noted significant interaction was probed following the recommendations of Aiken and West (1991). The equation was restructured to express the regression of internalizing problems on perceived maternal support at levels of friendship quality, separately for girls and boys. The values of perceived friendship quality chosen again corresponded to the mean, one standard deviation above the mean, and one standard deviation below the mean. For boys, the simple slope for the low friendship quality group approached significance (β = −.24, p = .09), whereas the simple slopes for the average (mean) and high friendship quality group were not significantly different from zero (β = −.16, ns, β = −.07, ns, respectively). As with perceived social competence, for boys with average or high-quality friendships, the level of maternal support was not a significant factor in predicting perceived internalizing difficulties. But low-quality friendship combined with low maternal support predicted the highest level of internalizing problems.

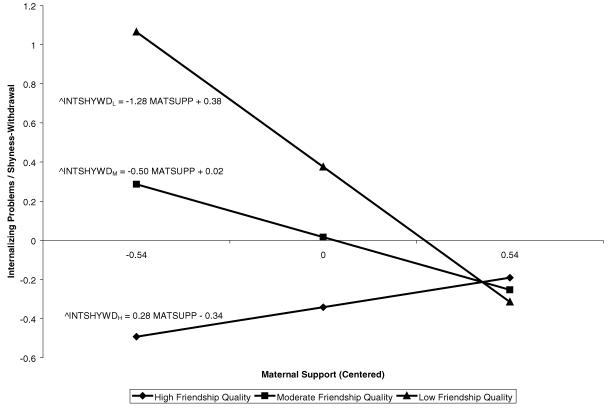

As indicated in Figure 3, the strongest (negative) relation between perceived maternal support and internalizing problems was obtained for girls reporting the lowest levels of friendship quality. The simple slopes for the low and average (mean) friendship quality groups were significantly different from zero (β = −.63, p < .01, and β = −.25, p < .05, respectively), whereas the simple slope for the high friendship quality group was not significantly different from zero (β = .14, ns). For both low- and average-quality friendships, low maternal support predicted the most internalizing problems. However, for girls with high-quality friendships, low maternal support was nonsignificantly associated with internalizing problems.

Figure 3.

Predicting internalizing and shyness and withdrawal from maternal support and perceived friendship quality (boys only).

Externalizing Problems

The overall regression predicting the externalizing problems from sex, perceived paternal support, and perceived friendship quality was significant, F(7, 136) = 3.39, p < .01, whereas the overall regression predicting externalizing difficulties from gender, perceived maternal support, and perceived friendship quality was not significant, F(7, 136) = 1.86. As indicated in Table 6, a significant (negative) main effect was revealed for perceptions of paternal support and maternal support, though the latter regression equation with all predictor variables yielded a nonsignificant R2.

TABLE 6.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Externalizing Problems From Perceived Maternal and Paternal Support and Perceived Friendship Quality (N = 144)

| Predictors | B | SE | β | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived maternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | .05 | .12 | .04 | .00 |

| Perceived maternal support | −.36 | .13 | −.28** | .05** |

| Perceived friendship quality | −.14 | .11 | −.12 | .01 |

| Gender × Support | −.14 | .26 | −.14 | .00 |

| Gender × Friendship Quality | .35 | .22 | .43 | .02 |

| Support × Friendship Quality | −.14 | .19 | −.07 | .00 |

| Gender × Support × Friendship Quality | .12 | .41 | .08 | .00 |

| Perceived paternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | .05 | .12 | .04 | .00 |

| Perceived paternal support | −.36 | .09 | −.33** | .11** |

| Perceived friendship quality | −.09 | .11 | −.07 | .00 |

| Gender × Support | −.05 | .18 | −.08 | .00 |

| Gender × Friendship Quality | .38 | .22 | .48† | .02† |

| Support × Friendship Quality | −.19 | .14 | −.12 | .01 |

| Gender × Support × Friendship Quality | .17 | .28 | .18 | .00 |

NOTE: Each predictor was entered as a separate step.

p < .10.

p < .01.

Rejection and Victimization

In terms of predicting peer-nominated rejection and victimization, both of the overall regression equations were significant, F(7, 154) = 3.12, p < .01, for the regression with gender, perceived maternal support, and perceived friendship quality as predictors, and F(7, 154) = 3.32, p < .01, for the regression with gender, perceived paternal support, and perceived friendship quality as predictors. In only the second set of analyses was parental support a significant predictor of rejection and victimization, with children who reported higher levels of paternal support being nominated significantly less often by their peers as rejected or victimized. As indicated in Table 7, a significant R2 change in peer-nominated rejection and victimization was attributable to perceived friendship quality in both sets of analyses. However, in both cases, a significant R2 change in peer-nominated rejection and victimization was also attributable to the interaction of gender and perceived friendship quality. Follow-up analyses revealed that the correlation between positive friendship quality and peer-nominated rejection and victimization was negative and significant for girls (r = −.42, p < .01), whereas this correlation was nonsignificant for boys (r = −.14).

TABLE 7.

Hierarchical Regression Analyses Predicting Peer-Nominated Rejection and Victimization From Perceived Maternal and Paternal Support and Perceived Friendship Quality (N = 162)

| Predictors | B | SE | β | ΔR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived maternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | .06 | .13 | .04 | .00 |

| Perceived maternal support | −.12 | .12 | −.08 | .01 |

| Perceived friendship quality | −.41 | .11 | −.31** | .08** |

| Gender × Support | −.01 | .25 | −.02 | .00 |

| Gender × Friendship Quality | −.53 | .22 | −.64* | .03* |

| Support × Friendship Quality | .03 | .16 | .02 | .00 |

| Gender × Support × Friendship Quality | .04 | .32 | .03 | .00 |

| Perceived paternal support | ||||

| Sex of young adolescent (1 = male, 2 = female) | .06 | .13 | .04 | .00 |

| Perceived paternal support | −.22 | .09 | −.20* | .04* |

| Perceived friendship quality | −.35 | .11 | −.27** | .06** |

| Gender × Support | −.11 | .18 | −.18 | .00 |

| Gender × Friendship Quality | −.44 | .22 | −.53* | .02* |

| Support × Friendship Quality | .05 | .14 | .03 | .00 |

| Gender × Support × Friendship Quality | .35 | .29 | .38 | .01 |

NOTE: Each predictor was entered as a separate step.

p < .05.

p < .01.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study support the contention that relationships with both parents and peers, especially friends, are significant in that they independently, as well as in concert, predict young adolescents' social and emotional adjustment. In the present study, we examined young adolescents' feelings pertaining to perceived parental support (an index of the child's internalized model of the child-parent attachment relationship), their perceptions of friendship quality, and the relations between these different relationship experiences and young adolescents' self-esteem, self-perceptions of social competence, and problems of an internalizing or externalizing nature. We attempted to evaluate whether young adolescents' experiences in parent-child and friendship relationships interacted to influence psychosocial functioning during early adolescence. Indeed, our data supported the overall hypothesis that perceived parental support and friendship quality made both independent and interactive contributions in the prediction of adjustment and maladjustment.

As expected, young adolescents' internal models pertaining to parental support were associated with their feelings and thoughts about themselves. Young adolescents reporting greater parental support (from both mothers and fathers) regarded themselves as more worthy and socially competent. Also, these young adolescents demonstrated fewer internalizing and externalizing problems, based on the aggregation of mothers' and peers' reports. Young adolescents reporting higher paternal (but not maternal) support also were less likely to be nominated by their peers as rejected and victimized. These findings are consistent with a growing body of research indicating that school-age children and young adolescents are better adapted when they feel secure and supported by a primary caregiver (Granot & Mayseless, 2001; Kerns et al., 1996; Simons et al., 2001). In the present study, we expanded previous work to include the fact that perceived paternal support also predicted internalizing and externalizing difficulties and peer victimization.

Young adolescents' perceptions of friendship quality also were associated with their self-esteem, perceptions of social competence, and internalizing problems. These findings are consistent with those indicating that children who have high-quality friendships, characterized by warmth and validation, are better adjusted than children who do not have a friend or who have low-quality friendships (Berndt et al., 1999; Booth et al., 1998; Fordham & Stevenson-Hinde, 1999; Ladd et al., 1996; Parker & Asher, 1993; Stocker, 1994). The findings also support the contention of Hartup and Stevens (1997) that “good outcomes are most likely when one has friends, one's friends are well socialized, and when one's relationships with these individuals are supportive and intimate” (p. 365).

There was also a negative association between friendship quality and peer nominations of rejection and victimization, but only for girls. Prior research has shown that although rejected children do have friends, their friendships tend to be qualitatively poor (Parker & Asher, 1993). The measure used herein, however, did not identify children in the traditional fashion as being sociometrically rejected; rather, a behavior-based reputational measure of peer-perceived rejection and victimization was used (Lease, Musgrove, & Axelrod, 2002). In this regard, the data are novel in that they provide a picture of reputationally rejected and victimized young adolescent girls as having poorer quality friendships. Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, and Bukowski (1999) have shown that a high-quality friendship may act as a buffer against victimization. Specifically, a protective friendship may break the cycle of victimization and internalizing and externalizing problems. Thus, although our findings are consistent with prior research, it is not clear why boys' friendship quality would not also be associated with rejection and victimization. Perhaps those girls who are less intimate and close with their friends also seem less attractive to outsiders (i.e., they may not be viewed as trustworthy or supportive by the peer group at large), reducing the protective factor of friendship. Similarly, Hodges and Perry (1999) have shown that children are at risk for victimization when they appear behaviorally vulnerable (e.g., physically weak or prone to anxiety) and interpersonally at risk (e.g., friendless). Therefore, it also is striking that boys' friendship quality was linked with internalizing difficulties but not to rejection and victimization. Perhaps, insofar as rejection and victimization are concerned, the quality of a friendship is not as salient for boys as whether one has a friend at all.

A main contribution of this study was its examination of the interactive effects of parent-child and friendship relationships during early adolescence as well as the main effects of these variables. Whether experiences in high-quality friendships could buffer the effects of perceptions of less supportive parenting was queried. Our previous research (Booth et al., 1998) indicated that friendship did not serve as a buffer for the link between insecure attachment and problematic outcomes. Specifically, among children who were insecurely attached to their mothers, the greater the reliance on the best friend for emotional support, the greater the externalizing problems. However, other researchers have found that having reciprocated friendships may moderate the effects of family adversity, including harsh parenting (Criss et al., 2002; Schwartz et al., 2000), and that experiences in high-quality friendships may buffer the effects of poor family functioning (Gauze, Bukowski, Aquan-Assee, & Sippola, 1996). Importantly, neither harsh parenting nor poor family functioning can be viewed as synonymous with an internalized model of the child-parent relationship. Can friendships and parent-child relationships serve the same functions? If provisions are not received in one relationship, might they be found in another? The work of Laible et al. (2000) suggests that at least during adolescence, attachment to parents and attachment to peers do serve similar functions in terms of adjustment and that each can moderate the effects of the other. In early adolescence, is it possible for friends (who are not attachment figures) to buffer or exacerbate the effects of less-than-optimal relationships with parents?

In the present study, there was a complex relation between feelings of maternal support, perceptions of friendship quality, and perceived social competence. For boys reporting friendships of at least average quality, maternal support was not related to perceived social competence. Yet for those boys who reported low-quality friendships, low maternal support was related to less positive views of their own social competence. Finally, boys reporting having more supportive mothers viewed their social competence about as positively as those boys who reported higher quality friendships. Attachment theory (Belsky & Cassidy, 1994) would suggest that children of sensitive, responsive parents should actively seek environments where their worth and competence are acknowledged. Indeed, although the results for girls did not reach significance, the findings suggest that having a friendship of at least average quality served to enhance the benefits of having a supportive parent on girls' feelings of self-worth and perceptions of social competence. Having a friendship characterized by warmth and validation seemed to reinforce the model of a worthy and competent self formed within the parent-child relationship. Yet some securely attached young adolescents will find themselves in friendship relationships that are not characterized by high levels of validation and support. The findings for boys may imply that having a supportive relationship with one's mother, and presumably a complementary internal working model of the self as worthy and competent, may protect young adolescents, particularly boys, when their friendships are not supportive. Indeed, these findings support the notion suggested by Richards, Gitelson, Petersen, and Hurtig (1991) that boys rely on their relationships with their mothers as they continue to develop their interpersonal skills into adolescence.

The findings also suggest a buffering effect of friendship on the relation between perceived parental support and internalizing difficulties. Specifically, high friendship quality buffered the effects of low maternal support on girls' internalizing difficulties. That is, girls reporting close, supportive friendships were reported less frequently by their mothers and peers as anxious, depressed, and withdrawn, even when perceived maternal support was low. It is noteworthy, however, that this buffering effect was not found for girls who reported their friendships to be of average quality. These findings suggest that a poor mother-child relationship may be a risk factor, especially for girls, such that it sets one on a course toward difficulties of an internalizing nature, a pathway that may not be easily alterable (i.e., not modified by simply having a friend or being in a friendship of even average quality).

Importantly, perceived paternal support predicted global self-worth, perceived social competence, difficulties of both an internalizing and externalizing nature, and peer victimization; these relations were not moderated by friendship quality for boys or girls. To date, very little is known about the role of the father-child relationship in influencing children's and adolescents' social competence and incompetence, including aggression and social withdrawal (Rubin & Burgess, 2002). Fathers spend less time interacting with their children throughout childhood and adolescence than mothers do, and when they do interact, their interactions tend to involve relatively more physical and outdoor play. The interactions of mothers and children tend to involve relatively more caregiving and household tasks (Collins, Madsen, & Susman-Stillman, 2002). Feiring and Taska (1996) have hypothesized that the playful interactions that characterize time spent with fathers may be important to the development of social skills and social competence. Parke and Buriel (1998) also have suggested that fathers are involved with the separateness task of adolescence (i.e., achieving autonomy), whereas mothers are involved with the task of connectedness (i.e., maintaining attachments, developing intimate relationships). Perhaps fathers who encourage independence without also providing the warmth and social support of a secure base have young adolescents who are less able to deal with their social problems than young adolescents whose interactions with their fathers are characterized by both support for independence and connectedness. Clearly, more research that examines the role of fathers in young adolescents' social and emotional adjustment is necessary. In addition, it is important to examine sources of support other than parents that may facilitate young adolescents' adjustment, including relationships with siblings, grandparents, and other extended family members.

Overall, this study demonstrates the importance of both parents and peers for social adjustment in early adolescence. In contrast to prior studies, young adolescents' perceived relationships with both fathers and mothers were examined as they relate to and influence the impact of friendships on psychosocial functioning. As well, the inclusion of an assessment of friendship quality allowed us to distinguish among young adolescents who merely have a friend from those who have friendships characterized by validation, intimacy, and loyalty as well as to examine the relative advantages and disadvantages of these friendship experiences. We also benefited from the perspectives of multiple informants for several of the outcome variables: Mothers reported on internalizing and externalizing difficulties, and classroom peers reported on aggression and shyness and withdrawal. In the case of internalizing difficulties, however, it may have been more appropriate to use a self-report measure of depression, anxiety, and withdrawal with this age group, which is the first limitation of this study. A second limitation is its reliance on paper-and-pencil methods. Although some of our measures included the perspectives of multiple informants, it will be useful in the future to add observational measures to gain a more complete picture of children's competencies and incompetencies. Finally, to draw conclusions regarding direction of effects and causality, further investigations must examine the longitudinal impact of parent-child and friendship relationships and the interactions between these relationship systems as children make the transition to adolescence.

Figure 4.

Predicting internalizing and shyness and withdrawal from maternal support and perceived friendship quality (girls only).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the children, parents, and teachers who participated in the study as well as Charissa Cheah, Stacey Chuffo, Erin Galloway, Jon Goldner, Sue Hartman, Amy Kennedy, Sarrit Kovacs, Alison Levitch, Abby Moorman, Andre Peri, Margro Purple, Josh Rubin, Erin Shockey, and Julie Wojslawowicz, all of whom assisted in data collection and input. The research reported in this manuscript was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Contributor Information

Cathryn Booth-LaForce, University of Washington.

Linda Rose-Krasnor, Brock University.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist: 4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Attachments across the life span. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1985;61:792–812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Newcomb AF, Bukowski WM. Preadolescent friendship and peer rejection as predictors of adult adjustment. Child Development. 1998;69:140–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Cassidy J. Attachment: Theory and evidence. In: Rutter M, Hay DF, editors. Development through life: A handbook for clinicians. Basil Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 1994. pp. 373–402. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Hawkins JA, Jiao Z. Influences of friends and friendships on adjustment to junior high school. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1999;45:13–41. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Keefe K. Friends' influence on adolescents' adjustment to school. Child Development. 1995;66:1313–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth CL, Rose-Krasnor L, Rubin KH. Relating preschoolers' social competence and their mothers' parenting behaviors to early attachment security and high-risk status. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1991;8:363–382. [Google Scholar]

- Booth CL, Rubin KH, Rose-Krasnor L. Perceptions of emotional support from mother and friend in middle childhood: Links with social-emotional adaptation and pre-school attachment security. Child Development. 1998;69:427–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Volume 2, Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Volume 1, Attachment. 2nd Basic Books; New York: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I. Attachment theory: Retrospect and prospect. (1-2, Serial No. 209).Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1985;50:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;58:1101–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Hoza B, Boivin M. Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11(3):472–484. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Marshall P, Rubin KH, Fox NA. Infant attachment and temperament as predictors of subsequent behavior problems and psychophysiological functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Discipline. 2003;44:1–13. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess KB, Rubin KH, Wojslawowicz J, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth C. The Extended Class Play: A longitudinal study of its factor structure, reliability, and validity. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Tampa, FL: Apr, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotional regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. (2-3, Serial No. 240).Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:228–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Ayers M. Friendship similarity during early adolescence: Gender and racial patterns. Journal of Psychology. 1992;126:393–405. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1992.10543372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn DA. Child-mother attachment of six-year-olds and social competence at school. Child Development. 1990;61:152–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Madsen SD, Susman-Stillman A. Parenting during middle childhood. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1. Children and parenting. 2nd Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Criss MM, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Lapp AL. Family adversity, positive peer relationships, and children's externalizing behavior: A longitudinal perspective on risk and resilience. Child Development. 2002;74:1220–1237. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Newman JP. Biased decision-making processes in aggressive boys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90:375–379. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elicker J, Englund M, Sroufe LA. Predicting peer competence and peer relationships in childhood from early parent-child relationships. In: Parke RD, Ladd GW, editors. Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Taska LS. Family self-concept: Ideas on its meaning. In: Bracken BA, editor. Handbook of self-concept: Developmental, social, and clinical considerations. John Wiley; New York: 1996. pp. 317–373. [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan RA, Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Preoccupied and avoidant coping during middle childhood. Child Development. 1996;67:1318–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Fordham K, Stevenson-Hinde J. Shyness, friendship quality, and adjustment during middle childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1999;40:757–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag MK, Belsky J, Grossmann K, Grossmann JE, Scheurer-Englisch H. Continuity in child-parent relationships from infancy to middle childhood and relations with friendship competence. Child Development. 1996;67:1437–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W. The measurement of friendship perceptions: Conceptual and methodological issues. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence. Cambridge University Press; UK: 1996. pp. 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:1016–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks and personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauze C, Bukowski WM, Aquan-Assee J, Sippola LK. Interactions between family environment and friendship and associations with self-perceived well-being during adolescence. Child Development. 1996;67:2201–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granot D, Mayseless O. Attachment security and adjustment to school in middle childhood. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:530–541. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, DeKlyen M. The role of attachment in the early development of disruptive problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:191–213. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development. 1982;53:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children. University of Denver; Denver, CO: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW, Stevens N. Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM. The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:94–101. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Attachment relationships in the context of multiple caregivers. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 671–687. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Matheson CC, Hamilton CE. Maternal, teacher, and child care history correlates of children's relationships with peers. Child Development. 1994;65:264–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns KA, Klepac L, Cole A. Peer relationships and preadolescents' perceptions of security in the child-mother relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:457–466. [Google Scholar]

- Krollmann M, Krappmann L. Poster presented at the 11th meeting of the German Psychological Society; Osnabruck, Germany: 1996. Bindung und Gleichaltrigenbeziehungen in der mittleren Kindheit [Attachment and peer relationships in middle childhood] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer BJ, Coleman CC. Friendship quality as a predictor of young children's early school adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67:1103–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFreniere PJ, Sroufe LA. Profiles of peer competence in the preschool: Interrelations between measures, influence of social ecology, and relation to attachment history. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Laible DJ, Carlo G, Raffaelli M. The differential relations of parent and peer attachment to adolescent adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lease AM, Musgrove KT, Axelrod JL. Dimensions of social status in preadolescent peer groups: Likeability, perceived popularity, and social dominance. Social Development. 2002;11:508–533. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M, Doyle A, Markiewicz D. Developmental patterns in security of attachment to mother and father in late childhood and early adolescence: Associations with peer relations. Child Development. 1999;70:202–213. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Morison P, Pellegrini DS. A revised class play method of peer assessment. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21(3):523–533. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney K, Owen MT, Booth CL, Clarke-Stewart A, Vandell DL. Testing a relational model of behavior problems in early childhood. 2003 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00270.x. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KA, Waters E. Security of attachment and preschool friendships. Child Development. 1989;60:1076–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD. Fathers and families. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 3: Being and becoming a parent. 2nd Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 27–74. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization within the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3: Social, emotional, and personality development. 5th John Wiley; New York: 1998. pp. 463–552. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship Quality Questionnaire–Revised: Instrument and administrative manual. University of Illinois; Champaign: 1989. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor DL. The quality of mother-infant attachment and its relationship to toddlers' initial sociability with peers. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17:326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Renken B, Egeland B, Marvinney D, Mangelsdorf S, Sroufe LA. Early childhood antecedents of aggression and passive-withdrawal in early elementary school. Journal of Personality. 1989;57:257–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards MH, Gitelson IB, Petersen AC, Hurtig AL. Adolescent personality in girls and boys: The role of mothers and fathers. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1991;15:65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rose-Krasnor L, Rubin KH, Booth CL, Coplan R. The relation of maternal directiveness and child attachment security to social competence in preschoolers. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1996;19:309–235. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB. Parents of aggressive and withdrawn children. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1: Children and parenting. 2nd Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 383–418. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Friendship as a moderating factor in the pathway between early harsh home environment and later victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:646–662. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.5.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharabany R, Gershoni R, Hofman JE. Girlfriend, boyfriend: Age and sex differences in intimate friendship. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17:800–808. [Google Scholar]

- Simons KJ, Paternite CE, Shore C. Quality of parent/adolescent attachment and aggression in young adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21:182–203. [Google Scholar]