Abstract

Mutations in the ATP6 gene of mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) have been shown to cause several different neurological disorders. The product of this gene is ATPase 6, an essential component of the F1F0-ATPase. In the present study we show that the function of the F1F0-ATPase is impaired in lymphocytes from ten individuals harbouring the mtDNA T8993G point mutation associated with NARP (neuropathy, ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa) and Leigh syndrome. We show that the impaired function of both the ATP synthase and the proton transport activity of the enzyme correlates with the amount of the mtDNA that is mutated, ranging from 13–94%. The fluorescent dye RH-123 (Rhodamine-123) was used as a probe to determine whether or not passive proton flux (i.e. from the intermembrane space to the matrix) is affected by the mutation. Under state 3 respiratory conditions, a slight difference in RH-123 fluorescence quenching kinetics was observed between mutant and control mitochondria that suggests a marginally lower F0 proton flux capacity in cells from patients. Moreover, independent of the cellular mutant load the specific inhibitor oligomycin induced a marked enhancement of the RH-123 quenching rate, which is associated with a block in proton conductivity through F0 [Linnett and Beechey (1979) Inhibitors of the ATP synthethase system. Methods Enzymol. 55, 472–518]. Overall, the results rule out the previously proposed proton block as the basis of the pathogenicity of the mtDNA T8993G mutation. Since the ATP synthesis rate was decreased by 70% in NARP patients compared with controls, we suggest that the T8993G mutation affects the coupling between proton translocation through F0 and ATP synthesis on F1. We discuss our findings in view of the current knowledge regarding the rotary mechanism of catalysis of the enzyme.

Keywords: ATPase 6 subunit, F1F0 ATPase, membrane potential, mitochondria, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) point mutation, proton transport

Abbreviations: Δψm, mitochondrial membrane potential; FQR, fluorescence quenching rate; NARP, neuropathy, ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa; MILS, maternally inherited Leigh syndrome; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism; RH-123, Rhodamine-123

INTRODUCTION

Proton transporting F1F0-ATP synthases are ubiquitous enzymes that catalyse the terminal step in oxidative phosphorylation. The enzymes consist of two structurally and functionally distinct sectors termed F1, the proper catalytic domain, where ATP synthesis or hydrolysis takes place, and F0, the membrane sector that sustains H+ transport. Structurally similar F1F0-ATP synthases are present in mitochondria, chloroplasts and most eubacteria [1]. The bacterial enzyme has the simplest subunit structure, α3β3γδϵ for F1 and ab2c10–14 for F0, and its enzymology is best understood [2]. The mitochondrial F0 domain has seven more distinct subunits. However, specific eukaryotic functional subunits are known, which correspond to those of the bacterial enzyme, including a, b and c [3].

The F1F0-ATP synthase is a molecular motor where proton translocation within F0 drives the rotation of a transmembrane ring of 10–14 c subunits, which induces the central part of F1 (γ, δ and ϵ subunits) to rotate relative to the surrounding α3β3 hexameric ring where ATP synthesis from ADP and Pi occurs [2].

In the bacterial system subunit a has been shown to play a major role in transporting protons through F0, and to induce the ring of c subunits to rotate [1]. More precisely, rotation involves protonation and deprotonation of the acidic Asp-61 of subunit c (Glu-58 in human mitochondria), located roughly in the middle of the membrane's hydrophobic layer. Subunit a, and its corresponding subunit, ATPase 6 in eukaryotes, is believed to have two functions. First, it leads the proton through a hydrophilic half-channel to its binding to Glu-58 of subunit c, it contributes to the protonation/deprotonation steps by dynamically bringing Arg-159 (Arg-210 in subunit a of Escherichia coli) into juxtaposition with the acidic residue of subunit c, the proton is then released into the mitochondrial matrix [4,5]. Secondly, it turns the rotor for ATP synthesis. A mutation in subunit a might thus interfere with either the flow of protons into the mitochondrial matrix, or with turning of the rotor, or both of these functions.

The biogenesis of eukaryotic F1F0-ATPase involves co-ordination of both the nuclear and the mitochondrial genomes [6,7]. A large number of mutations affecting human mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) are associated with disorders involving tissues that are characterized by a high-energy demand, including the central nervous system, as well as skeletal and cardiac muscles [8].

The mtDNA T8993G point mutation in the ATPase 6 gene leads to an Leu-156→Arg amino acid change, which is associated with the clinical phenotype of NARP (neuropathy, ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa) when the mutation load (percentage of mutant mtDNA or heteroplasmy) is typically below 90–95%, or in the case of MILS (maternally inherited Leigh syndrome) when the mutation load is greater than 95% [8]. There is a general consensus that the main biochemical defect induced by the T8993G mutation is an impairment in the rate of ATP synthesis [9–13]. However, which step in the molecular synthesis of ATP is precisely involved and which is the primary mechanism of cell damage are questions that have not been fully elucidated. Leu-156 is highly conserved in eukaryotes (it corresponds to Leu-207 of subunit a in the E. coli F1F0-ATP synthase). Based on protein structure predictions and on the homology between subunits a and ATPase 6, residue Leu-156 of human mitochondrial ATPase 6 is located in close proximity to residue Glu-58 of subunit c [14]. Hartzog and Cain [15] investigated the biochemical effects of the ATPase 6 L207R mutation in E. coli, and proposed that the mutation affects either assembly or stability of the enzyme and could result in a block of proton translocation through the ATP synthase complex. This hypothesis lacked experimental support, and on the contrary, ATP-driven H+ translocation of submitochondrial particles in patient platelets harbouring up to 93% mutation load, was hardly impaired [11]. This was demonstrated by monitoring proton translocation from the matrix towards the intermembrane space, that is in opposition to the passive proton flow occurring during ATP synthesis in normoxic conditions. This suggests either uncoupling within the mutated F0F1 complex or unidirectional impairment of proton flow under physiological conditions.

We recently published a study of a very sensitive and reproducible method to measure the physiological H+ flow in intact mitochondria [16]. This method allows the evaluation of membrane potential and proton flow from the cytosolic side of the mitochondrial inner membrane to the matrix. Using this method we have examined ATP synthase proton transport in lymphocytes of individuals harbouring a 13–94% mutation T8993G load, and correlated the Δψm (mitochondrial membrane potential) with ATP synthesis. The F1F0-ATP synthase dysfunction induced by the NARP/MILS mutation is not due to the failure of protons to cross the bilayer through F0.

EXPERIMENTAL

Patients

Members of four pedigrees harbouring the T8993G mutation were investigated. Clinical details of these patients have been reported previously [17,18], and when referred to below, individuals are designated as in these reports.

Cell culture

PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cells) were obtained by Ficoll-Hypaque Plus centrifugation of EDTA-treated blood, washed twice in PBS and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum, 50 units/ml penicillin and 50 mg/ml streptomycin. PBMCs (106 cells/ml) were cultured in T-75 flasks for 3 h at 37 °C in a humidified incubator. Lymphocytes (non-adherent cells) were then harvested, pelleted, resuspended in fresh medium and cultured for 48 h. Viability was usually approx. 90% in both control and patient cells, and cell population homogeneity (95% lymphocytes) was assessed by flow cytometry.

mtDNA analysis

Total DNA was extracted by means of the standard phenol/chloroform method from a pellet of the same lymphocytes as used for biochemical investigations. To detect the T8993G mutation, a convenient 551 bp segment of mtDNA was amplified by PCR as described previously [11]. The mutation was detected by RFLP (restriction fragment length polymorphism) analysis after digestion of the PCR product with the restriction endonuclease, AvaI. The co-presence of three fragments, one uncut wild-type (551 bp) and two cut-mutant fragments (345 and 206 bp), indicated heteroplasmy. To evaluate the ratio of mutant to wild-type mtDNA, digestion products were electrophoresed through a 3% NuSieve-containing 0.5% agarose gel and visualized by UV transillumination after ethidium bromide staining. The AvaI-digested fragments were quantified by scanning the gel with an image analysing system (Quantity One Quantitation software 4.1 for a Fluor-S™ MultiImager Bio-Rad densitometer).

ATP synthesis and citrate synthase assay

Cellular ATP synthesis rate was measured by the highly sensitive luciferin/luciferase chemiluminescent method. In order to permeabilize cells and minimize ATP synthesis by biochemical pathways other than oxidative phosphorylation, lymphocytes (20×106 cells/ml) were incubated for 20 min at room temperature with 60 μg/ml digitonin, 2 mM iodoacetamide, and the adenylate kinase inhibitor, P1, P5-di(adenosine-5′) pentaphosphate penta-sodium salt (25 μM), in 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 5 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM EGTA, 3 mM EDTA and 2 mM MgCl2. Complex II driven ATP synthesis was induced by adding 20 mM succinate, 4 μM rotenone and 0.5 mM ADP to the sample. The reaction was carried out at 30 °C and after 5 min it was stopped by the addition of 80% DMSO. Synthesized ATP was extracted from the cell suspension and assayed by the luminometric method as described in [19]: as a blank a sample that was not energized with succinate, but containing both 18 μM antimycin A and 2 μM oligomycin, was used.

The citrate synthase activity was assayed essentially as described in Trounce et al. [20] by incubating cell samples with 0.02% Triton X-100, and monitoring the reaction by measuring the rate of free coenzyme A release spectrophotometrically. Citrate synthase activity was similar in individuals carrying the mtDNA T8993G mutation and in controls (25.94±8.80 nmol/min per mg of protein), indicating a lack of mitochondrial mass enhancement in mutant cells.

Protein determination

The protein concentration of samples was assessed by the method of Lowry et al. [21] in the presence of 0.3% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate. BSA was used as a standard.

Steady-state Δψm measurements

To evaluate the physiological proton translocation activity of the mitochondrial ATP synthase complex (protons flowing from the intermembrane space to the matrix), we measured the steadystate Δψm by means of the fluorescent cationic dye RH-123 (Rhodamine-123), which distributes electrophoretically into the mitochondrial matrix in response to the electric potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane [22]. Briefly, lymphocytes (2×106/ml) were suspended in a respiratory buffer [250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Hepes, 100 μM K-EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2 and 4 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4)] containing an ADP regenerating system (5 units/ml hexokinase and 10 mM glucose) and 50 nM RH-123 were incubated with 33 nM cyclosporin A, 2.5 μM rotenone and 200 μM ADP, and then permeabilized by adding 15 μg/ml digitonin. RH-123 fluorescence change kinetics (λexc=503 nm; λem=527 nm) were induced by the addition of 20 mM succinate to the sample that was either pre-incubated (pseudo-state 4 respiratory condition) with 2 μM oligomycin or not (state 3 respiratory condition).

RESULTS

Characterization of cells

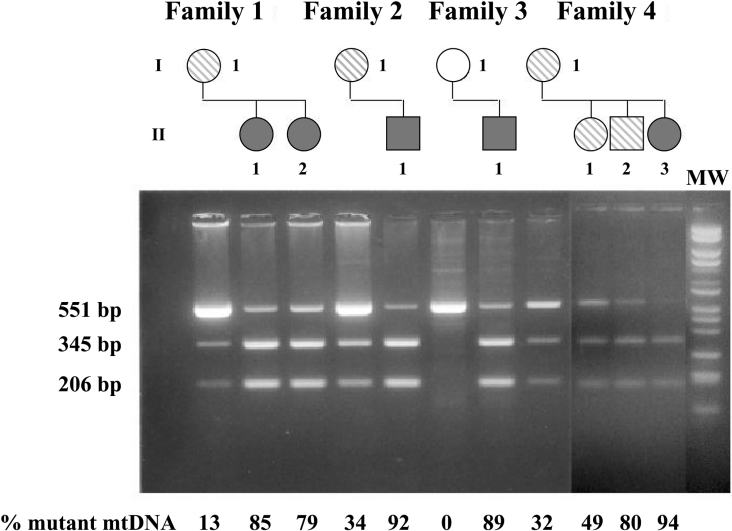

To determine the consequences of the T8993G mutation on mitochondrial function, lymphocytes from ten individuals carrying the mutation and belonging to four Italian unrelated families were analysed and compared with 12 controls. Five of these individuals were diagnosed with full-blown NARP syndrome, whereas the rest had either none or mild neurological symptoms [17,18]. Lymphocytes isolated from blood were maintained in RPMI medium (glucose-rich medium), and after 48 h cell viability was found to be in the normal range (approx. 90%) for both control and patient cells. The results of mtDNA analysis of the cells are shown in Figure 1. All probands presented with mutant mtDNA loads ranging from 13–94%, as detected by RFLP analysis.

Figure 1. Pedigree of four families carrying the mtDNA T8993G mutation and mtDNA heteroplasmy of lymphocyte probands.

Top, pedigrees of the four Italian families investigated. White symbols indicate unaffected individuals without the mutation; hatched symbols, carrier of the mutation with non-specific symptoms; dark-grey symbols, individuals with full-blown NARP or MILS. Bottom, electrophoretic gel showing the AvaI digestion of PCR products. The presence of three fragments correspond to the coexistence of both wild-type (551 bp) and mutant (345 and 206 bp) mtDNA in patients. Mutant mtDNA was absent in the control samples. Relative densitometric quantification of the AvaI-digested fragments allows evaluation of the percentage of mtDNA heteroplasmy. MW, size markers

Rate of ATP synthesis in digitonin-permeabilized T8993G heteroplasmic cells

The main function of mitochondria is to synthesize ATP, driven by a substantial electrical membrane potential across the mitochondrial inner membrane. In normally functioning mitochondria, the Δψm is generated by proton translocation from the matrix to the intermembrane space coupled with the electron transfer from reduced nicotinamide and flavin dinucleotides to oxygen, which is carried out by the respiratory chain complexes. To quantify ATP synthesis in relation to the mutation load of lymphocytes carrying the T8993G transversion, we measured the rate of mitochondrial ATP synthesis in digitonin-permeabilized cells energized with succinate. We were particularly keen to quantify the decrease in ATP synthesis in lymphocytes from NARP patients owing to the high variability of the data reported [9–12]. In order to definitively determine ATPase activity in heteroplasmic cells, we carefully designed the assay with particular attention to the following: (i) digitonin concentration compared with protein concentration in the medium; (ii) presence in the assay medium of both glycolysis and adenylate kinase inhibitors at adequate concentrations; (iii) as a blank we used the succinate-less assay cocktail supplemented with antimycin; (iv) exogenous Mg2+ was included in the assay medium in order to supply saturating Mg-ADP to the ATP synthase complex. Figure 2 shows that ATP synthesis catalysed by the F1F0-ATP synthase decreases sharply in lymphocytes from the five NARP patients, reaching a 70% decrease when mutant mtDNA load is approx. 90%.

Figure 2. Mitochondrial ATP synthesis in digitonin-treated lymphocytes.

The reaction mixture contained: 20×106 cells/ml, 60 μg/ml digitonin, 2 mM iodoacetamide, 25 μM P1, P5-di(adenosine-5′) pentaphosphate pentasodium salt, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, 3 mM EDTA, 5 mM KH2PO4 and 2 mM MgCl2 in Tris/HCl (pH 7.4). ATP synthesis was supported by adding 20 mM succinate (in the presence of 4 μM rotenone) and 0.5 mM ADP. The reaction was carried out at 30 °C for 5 min, and the amount of ATP synthesized was measured with the luciferin/luciferase chemiluminescent method [15]. Data reported for patients are presented as mean for two determinations in lymphocyte preparations.

Δψm in digitonin-permeabilized T8993G heteroplasmic cells

The energy of the transmembrane H+ electrochemical gradient (the proton-motive force, ΔμH+) resulting from the respiratory chain activity is mainly used by the F1F0-ATP synthase to generate ATP. This process requires that protons, flowing down their concentration gradient through F0, release energy to the enzyme and drive rotation of subunits, which allows synthesis and release of ATP at the catalytic sites in F1.

Determination of which step in the catalytic mechanism of F1F0-ATP synthase is impaired by the T8993G mutation is required in order to understand precisely the biochemical consequences of this mutation. As previously hypothesized [10], but then questioned [11], this step could be a result of the block of proton translocation through F0. To clarify this issue, we designed a method [16] that allows the measurement of H+ translocation through F0 when protons flow physiologically from the cytosol to the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane. The method is based on monitoring the initial rate of respiration-induced RH-123 fluorescence quenching that is quantitatively associated with the Δψm.

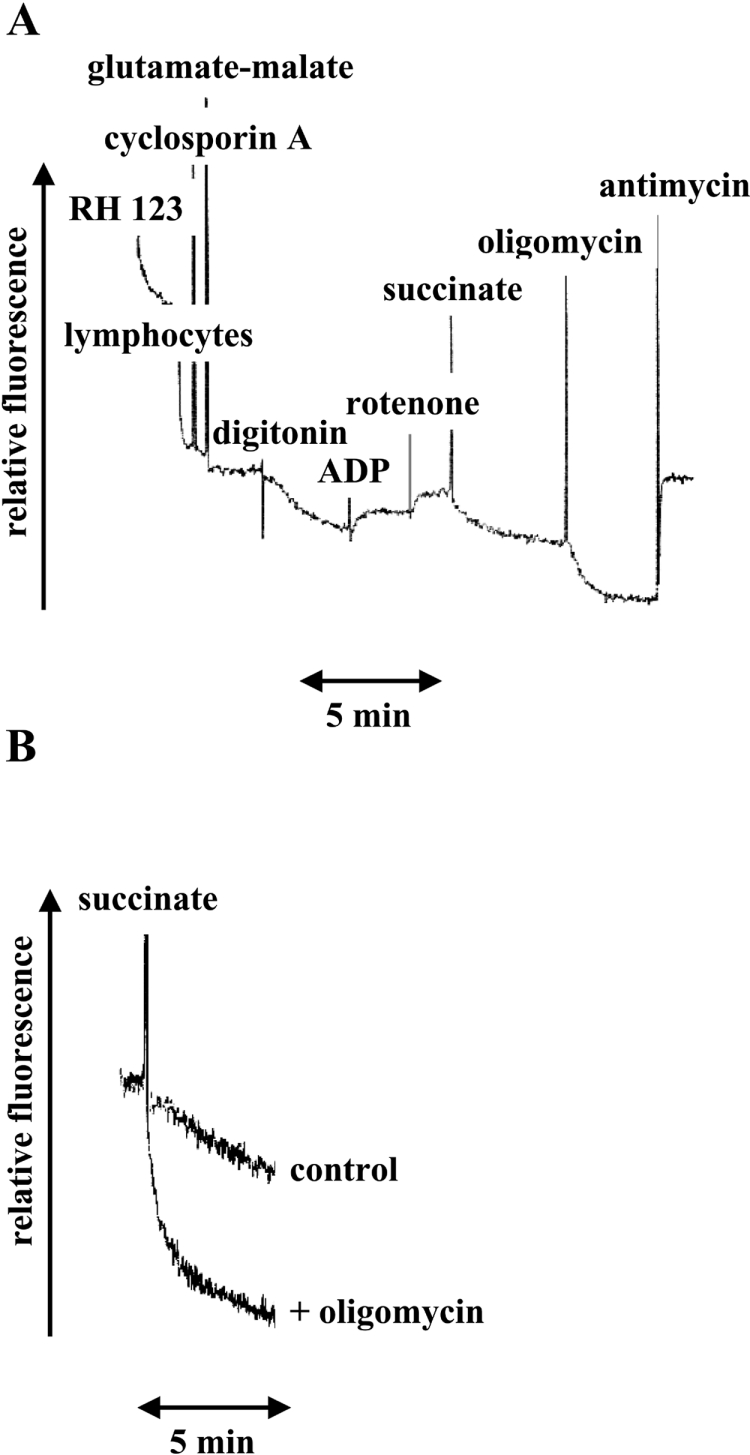

Protons are extruded from mitochondrial matrix by the respiratory complexes into the intermembrane space, and easily diffuse back in through F0. However, a significant amount of fluorescence quenching is maintained at a steady-state as a balance between respiration activity and proton flow through F0 (Figure 3A). This approach is sensitive enough to detect small changes in Δψm within a broad range, and it allows measurement of Δψm changes caused by protons moving through the inner membrane when pumped by respiratory complexes or when flowing down the proton gradient through F0 [16]. Therefore the electrical component of the membrane potential generated by proton movements across the inner mitochondrial membrane in digitonin-permeabilized lymphocytes of both controls and patients was evaluated.

Figure 3. RH-123 fluorescence changes in digitonin-permeabilized lymphocytes upon addition of respiratory substrates and inhibitors.

(A) Fluorescence measurements were carried out in a respiratory buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Hepes, 100 μM K-EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2 and 4 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4), containing an ADP regenerating system (10 mM glucose and 2.5 units of hexokinase). Additions were 50 nM RH-123, 2×106/ml lymphocytes, 33 nM cyclosporin, 10 mM glutamate/10 mM malate, 15 μg/ml digitonin, 200 μM ADP, 2.5 μM rotenone, 20 mM succinate, 2 μM oligomycin and 1 μg/ml(1.8 μM) antimycin. (B) RH-123 fluorescence kinetics induced by the addition of 20 mM succinate to digitonin-treated lymphocytes pre-incubated or not with 2 μM oligomycin. The sample mixture consisted of 0.5 ml of respiratory buffer containing an ADP regenerating system, 50 nM RH-123, 2×106/ml lymphocytes, 33 nM cyclosporin, 2.5 μM rotenone, 0.2 mM ADP and 15 μg/ml digitonin.

Figure 3(B) shows the fluorescence decay of RH-123 upon energization of mitochondria with succinate, in the presence of ADP (state 3 respiration) and also in the presence of both ADP and saturating oligomycin. This molecule abolishes state 3 respiration by binding to the ATP synthase F0-sector, and blocking its proton conduction pathway (i.e. the flow back of protons into the matrix). The FQR (fluorescence quenching rate) after normalization is expressed as (ΔF/Fi)/s per 106 cells and is an index of Δψm, according to details reported previously [16].

An analysis of lymphocyte mitochondrial Δψm under state 3 respiratory conditions showed a slightly higher level of FQR in cells from patients (Figure 4), particularly when the mutation load was greater than 80%, indicating an enhanced Δψm in patients' cells compared with controls. However, even in cells bearing greater than 90% heteroplasmy, FQR was dramatically lower (26%) than that observed in cells treated with saturating oligomycin (2 μM). When the ATP synthesis activity of control lymphocytes was inhibited to 80% of control values by 30 nM oligomycin, FQR was nearly 3-fold higher than that observed in NARP patients' cells (Figure 4). Interestingly, both controls and patients' cells treated with saturating oligomycin showed similar FQR values, indicating similar sensitivities of both mutant and wild-type enzymes to the inhibitor. This observation is consistent with the view that Δψm enhancement in NARP cells is due to ATP synthase dysfunction alone.

Figure 4. Δψm in lymphocytes of individuals harbouring the mtDNA T8993G mutation.

Digitonin-permeabilized lymphocytes (2×106/ml) incubated with 50 nM RH-123 were energized with succinate, and the kinetics of the accumulation of the positively charged probe in mitochondria was evaluated by monitoring the fluorescence emission at 527 nm (λex=503 nm). The sample mixture contained 0.5 ml of respiratory buffer [250 mM sucrose, 10 mM Hepes, 100 μM K-EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2 and 4 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4)] with an ADP regenerating system; 33 nM cyclosporin A, 2.5 μM rotenone and 0.2 mM ADP. Patient data (state 3 respiratory condition) are reported as the mean for two measurements, whereas control data (state 3 respiratory condition) and data from both oligomycin-treated controls and patients are reported as the means±S.D.

In conclusion, our results clearly indicate the occurrence of Δψm under ADP phosphorylating conditions that is compatible with a slightly lower membrane permeability (i.e. F0) to protons in cells of patients compared with those of controls, rather than with blockade of proton translocation in F0.

Correlation between T8993G mutation load, ATP synthesis rate and FQR

The lymphocytes of the ten patients examined had variable proportions of mutant mtDNA, ranging from 13–94%. The number of NARP patients examined and the wide-ranging mutation load available allowed us to correlate the heteroplasmy with the biochemical parameters analysed.

The ATP synthesis rate in cells harbouring the T8993G mutation decreases linearly with increased mutation load (Figure 5A), indicating a close relationship between tissue heteroplasmy and the expression of the biochemical defect in ATP synthesis. A linear and positive correlation was found in patients between digitonin-permeabilized cell FQR and the proportion of mutant mtDNA (Figure 5B). Therefore the biochemical defect was strictly related to the degree of heteroplasmy, with no evidence of a biochemical threshold. However, it is worth noting that a 60–75% mutant mtDNA load is required for obvious clinical expression of central-nervous-system symptoms [23,24].

Figure 5. Correlation between ATP synthesis rate, Δψm and mutation load.

ATP synthesis rate and Δψ were measured in permeabilized lymphocytes from both 10 probands carrying the mtDNA T8993G mutation and 12 healthy and age-matched volunteers as controls. (A) The correlation between ATP synthesis rate and mutation load (r2=0.85). (B) The correlation between Δψm and mutation load (r2=0.72). (C) The correlation between ATP synthesis rate and Δψm (r2=0.83).

Since both ATP synthesis rate and FQR are functional parameters associated with the efficiency of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, and since the methods used to measure the two parameters are completely independent, we also analysed the relationship between ATP synthesis rate and FQR, and observed a linear negative correlation with a high r2 of 0.89 (Figure 5C). The linear dependence of the rate of ATP synthesis on FQR does not imply that the former is caused by the latter, or vice versa, but simply that both parameters are a consequence of the T8993G transversion in mtDNA. Moreover, since the rate of ATP synthesis changes more sharply with heteroplasmy than does Δψm, and it can be extrapolated to zero when ΔF/Fi is below 0.6 (Figure 5C), whereas ΔF/Fi is above 1.6 when oligomycin blocks proton transport through F0 (Figure 4), the dramatic decrease in the rate of ATP synthesis in cells from NARP patients is probably not due to a block in proton transport. This supports the direct observation that the mutated enzyme retains the ability to translocate protons as described above.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides experimental evidence to support our original speculation [11] that the membrane sector, F0, of the mitochondrial ATP synthase complex carrying the Leu-156→Arg change in the ATPase 6 subunit is competent for proton translocation. Previous results have only shown that the mutated enzyme could support ATP-driven proton translocation from the matrix to the intermembrane space. In the present study we report experimental data on the physiological (i.e. from the cytosol to the matrix) activity of the mutated enzyme on proton flow, allowing us to clarify the molecular mechanism that induces insufficient ATP synthesis in cells from patients harbouring the T8993G transversion.

The previous interpretation that this mutation may cause a block in proton flow through the membrane sector F0 of the ATP synthase complex was not sufficiently supported by experimental data and it was challenged by our previous study [11]. In the same study we firstly hypothesized that the mutation might impair the coupling of ATP synthesis in F1 to proton flow through F0, but direct evidence was not available at that time. Moreover, in a purely speculative study, Schon et al. [25] did not rule out possible uncoupling within the mutated ATP synthase complex. Our present study clearly shows that the mutated F0 can translocate H+ from the cytoplasm to the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane under state 3 respiratory conditions. Moreover, the impairment of ATP synthesis is linearly and inversely correlated with the proton transport activity of F0. Therefore considering the results together, and since the drastic changes in the rate of ATP synthesis were reflected by only modest changes in the proton transport activity of the F1F0 complex, the most likely explanation for the mechanism responsible for the impairment of ATP synthesis is the failure of the enzyme to couple phosphorylation of ADP to proton translocation down the membrane proton gradient.

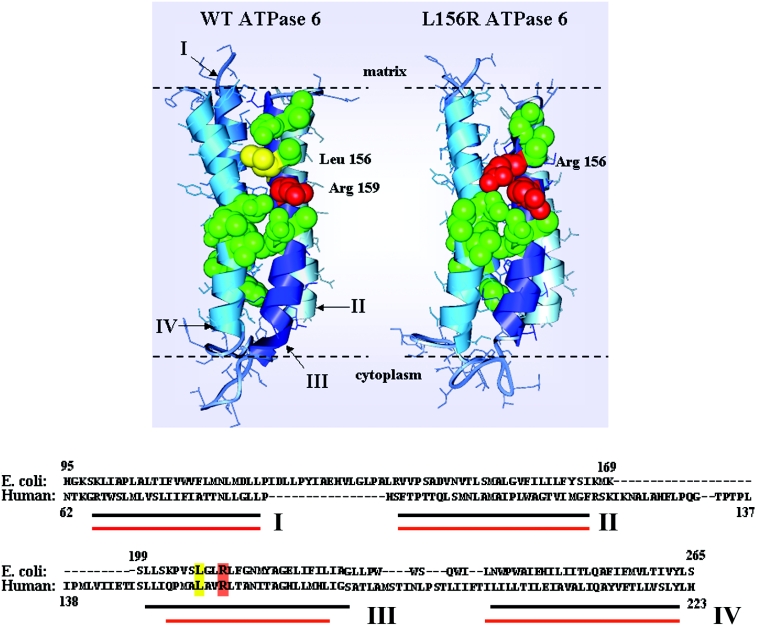

The actual mechanism of ATP synthesis is brought about by the rotary ATP synthase which couples H+ transport through F0 with catalysis in F1, which are approx. 10 nm apart [26]. The proton flux, involving the transmembrane helices of ATPase 6, and Glu-58 of subunit c, induces the subunit c oligomer to rotate, and this in turn drives the rotation of a central rotor within F1, allowing the binding change mechanism to operate [1]. According to the current view, mitochondrial ATPase 6 provides access channels to the proton-binding Glu-58 residue, which in turn by protonation and deprotonation and associated conformational changes moves past a stationary subunit ATPase 6 [27–29]. This is described in more detail in the scheme shown in Figure 6; helix III (i.e. the transmembrane segment of the ATPase 6 containing the functionally essential Arg-159) senses the conformational change in subunit c, in which Glu-58 juxtaposed with a Arg-159 deprotonates. This allows proton release into the matrix through the four-helix bundle of ATPase 6 [30]. The consequent conformational rearrangement of these helices, which moves Arg-159 away from Glu-58 in subunit c allows protons to flow down the proton gradient through the cytoplasmic half-channel. This is followed by protonation of Glu-58 and concerted conformational changes of the ATPase 6 helices that cause the ring of c subunits to rotate. According to the three-dimensional model described in Figure 6, when physiological Leu-156 is replaced with arginine, as occurs in the mutated ATP synthase complex, the positively charged and bulky amino acid residue (red in Figure 6) causes a structural change particularly prominent in the helix III region proximal to the aqueous matrix phase. Interestingly, it appears that the L156R change does not alter the core structure of helix III (containing both Arg-156 and Arg-159). This, together with the observed permeability of F0 to protons suggests that the two functions of ATPase 6, (i) to rotate the ring of c subunits and (ii) to conduct the protons to the opposite side of the bilayer, can be differentially affected by the mutation. The L156R change interferes with the first function of ATPase 6, but does not affect the second, therefore it uncouples ADP phosphorylation in F1 from proton transfer through F0. The accessible aqueous residues (green in Figure 6) create a proton pathway that might be physiologically blocked by the hydrophobic leucine residue, and ‘facilitated’ by the Arg-156 in the mutant enzyme. By contrast, rotation of the subunit c ring might be impaired by the introduction of an extra arginine residue. Results previously reported by Vazquez-Memije et al. [31] are consistent with uncoupling of the oxidative phosphorylation machinery, indicating that mitochondria isolated from fibroblasts of NARP patients have an increased respiration rate under state 4 conditions (i.e. non-phosphorylating conditions) compared with controls.

Figure 6. Ribbon diagram comparing the predicted four transmembrane α-helices of wild-type and mutant human ATPase 6.

Top, the scheme is based on the three-dimensional model of the E. coli ac12 complex [41] (PDB accession number, 1C17). Leu-156 of the mitochondrial enzyme is shown in yellow, whereas the essential Arg-159 and Arg-156 (in the mutant enzyme only) residues are shown in red. The amino acids reported to take part in the proton translocation [33] are represented in green. Bottom, the partial amino acid sequence of wild-type human ATPase 6. Transmembrane α-helices, as predicted by homology modelling software (EasyPred, http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/biotools/EasyPred/), are indicated by red (mutated) and black (wild-type) lines.

A corollary of the findings in the present study is that the incorrect assembly of the mutated F1F0-ATP synthase proposed by some authors [32,33] may occur, and could in fact contribute to the inefficient passive proton translocation through the inner mitochondrial membrane (i.e. F0). Early association between subunits a and c is essential for the control of proton flux through F0, therefore an unassembled F1F0-ATPase could be associated with either a block or a fully uncontrolled translocation of the protons within F0. Whether the L156R change also affected the stability of the enzyme was not addressed in our study, but Garcia et al. [12] in an extensive study on the structure and assembly of the mutated enzyme found that the level of F1F0 complexes was close to normal and that complexes were stable. On the other hand indirect indications of the presence of assembled F1F0 in mutated cells can also be inferred from our previous work [11], showing both unaffected F1F0-catalysed ATP hydrolysis and ATP-driven proton translocation in NARP mitochondria exposed to sonic oscillation. Observations made in other laboratories [12,34] and the findings of the present study are also in agreement with this view, that the enzyme activities are fully oligomycin-sensitive, a property that is lost, for instance, when the enzyme structure is severely altered [35,36].

It is also noteworthy that the biochemical analysis of the human mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase affected by the mtDNA T8993G mutation in the ATP6 gene had revealed an inverse correlation between the rate of ATP synthase activity and the mutation load, extending and supporting our previous results based on studies carried out in inverted submitochondrial particles prepared from a limited number of individuals carrying the NARP mutation [24]. Of even more interest is the observation that the membrane potential of mitochondria from the same individuals also correlates linearly with heteroplasmy, therefore providing evidence that the control of membrane potential may be a possible therapeutic target with which to limit the dramatic effects of the mutation.

In conclusion, our study clearly shows that, besides its appeal to our understanding the pathogenesis of disease, and its importance in designing appropriate therapies, biochemical analysis of the mammalian ATP synthase complex carrying mutations in structural genes of its subunits offers new insights into the function, structural organization and regulation of this enzyme complex. We are investigating the effects of other mutations in the human ATP6 gene on the assembly and functional properties of the F0-ATPase, and future experiments will focus on the functional and structural features of ATPase 6 and other F0 polypeptides in mammalian mitochondria.

Finally, the present results may establish a baseline for studies aimed to test therapeutic strategies, in particular drugs that act as energy suppliers or anti-oxidants (increased membrane potential is usually associated with overproduction of reactive oxygen species [37]), apart from gene therapy approaches which have been recently attempted [38–40], but still need much work in order to have therapeutic benefits.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor T. H. Haines (Department of Chemistry, City College of CUNY, NY, U.S.A.) for reading the manuscript, Dr M. Zeviani (Molecular Neurogenetics Unit, National Institute of Neurology C. Besta, Milan, Italy) and Dr P. Montagna (Department of Neurological Science, University of Bologna, Italy) for referring the patients. This work was supported by Comitato Telethon Fondazione Onlus, Roma, project number GP0280/01 to G. S.

References

- 1.Boyer P. D. The ATP synthase – a splendid molecular machine. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997;66:717–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber J., Senior A. E. ATP synthesis driven by proton transport in F1F0-ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 2003;545:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collinson I. R., Skehel J. M., Fearnley I. M., Runswick M. J., Walker J. E. The F1Fo-ATPase complex from bovine heart mitochondria: the molar ratio of the subunits in the stalk region linking the F1 and F0 domains. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12640–12646. doi: 10.1021/bi960969t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fillingame R. H., Angevine C. M., Dmitriev O. Y. Mechanics of coupling proton movements to c-ring rotation in ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angevine C. M., Fillingame R. H. Aqueous access channels in subunit a of rotary ATP synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:6066–6074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearnley I. M., Walker J. E. Two overlapping genes in bovine mitochondrial DNA encode membrane components of ATP synthase. EMBO J. 1986;8:2003–2008. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sierra M. F., Tzagoloff A. Assembly of the mitochondrial system. Purification of a mitochondrial product of the ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1973;70:3155–3159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.11.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiMauro S., Schon E. A. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;106:18–26. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trounce I., Neill S., Wallace D. C. Cytoplasmic transfer of the mtDNA nt 8993 T>G (ATP6) point mutation associated with Leigh syndrome into mtDNA-less cells demonstrates cosegregation with a decrease in state III respiration and ADP/O ratio. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:8334–8338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tatuch Y., Robinson B. H. The mitochondrial DNA mutation at 8993 associated with NARP slows the rate of ATP synthesis in isolated lymphoblast mitochondria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;192:124–128. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baracca A., Barogi S., Carelli V., Lenaz G., Solaini G. Catalytic activities of mitochondrial ATP synthase in patients with mitochondrial DNA T8993G mutation in the ATPase 6 gene encoding subunit a. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:4177–4182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia J. J., Ogilvie I., Robinson B. H., Capaldi R. Structure, functioning, and assembly of the ATP synthase in cells from patients with the T8993G mitochondrial DNA mutation. Comparison with the enzyme in RhoO cells completely lacking mtDNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11075–11081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pallotti F., Baracca A., Hernandez-Rosa E., Walker W. F., Solaini G., Lenaz G., Melzi D'Eril G. V., Dimauro S., Schon E. A., Davidson M. M. Biochemical analysis of respiratory function in hybrid cell lines harbouring mitochondrial DNA mutations. Biochem. J. 2004;384:287–293. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howitt S. M., Rodgers A. J., Hatch L. P., Gibson F., Cox G. B. The coupling of the relative movement of the a and c subunits of the F0 to the conformational changes in the F1-ATPase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 1996;28:415–420. doi: 10.1007/BF02113983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartzog P. E., Cain B. D. The a Leu207→Arg mutation in F1F0-ATP synthase from Escherichia coli. A model for human mitochondrial disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:12250–12252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baracca A., Sgarbi G., Solaini G., Lenaz G. Rhodamine 123 as a probe of mitochondrial membrane potential: evaluation of proton flux through F0 during ATP synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1606:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(03)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uziel G., Moroni I., Lamantea E., Fratta G. M., Ciceri E., Carrara F., Zeviani M. Mitochondrial disease associated with the T8993G mutation of the mitochondrial ATPase 6 gene: a clinical, biochemical, and molecular study in six families. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1997;63:16–22. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.63.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puddu P., Barboni P., Mantovani V., Montagna P., Cerullo A., Bragliani M., Molinotti C., Caramazza R. Retinitis pigmentosa, ataxia, and mental retardation associated with mitochondrial DNA mutation in an Italian family. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1993;77:84–88. doi: 10.1136/bjo.77.2.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanley P. E., Williams S. G. Use of the liquid scintillation spectrometer for determining adenosine triphosphate by the luciferase enzyme. Anal. Biochem. 1969;29:381–392. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trounce I. A., Kim Y. L., Jun A. S., Wallace D. C. Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Methods Enzymol. 1996;264:484–509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emaus R. K., Grunwald R., Lemasters J. J. Rhodamine 123 as a probe of transmembrane potential in isolated rat-liver mitochondria: spectral and metabolic properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1986;850:436–448. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(86)90112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White S. L., Collins V. R., Wolfe R., Cleary M. A., Shanske S., Di Mauro S., Dahl H. H., Thorburn D. R. Genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis for the mitochondrial DNA mutations at nucleotide 8993. Am. J. Hum. Gen. 1999;65:474–482. doi: 10.1086/302488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carelli V., Barogi S., Baracca A., Pallotti F., Valentino M. L., Montagna P., Zeviani M., Pini A., Lenaz G., Baruzzi A., Solaini G. Biochemical-clinical correlation in patients with different loads of the mitochondrial DNA T8993G mutation. Arch. Neurol. 2002;59:264–270. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schon E. A., Santra S., Pallotti F., Girvin M. E. Pathogenesis of primary defects in mitochondrial ATP synthesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001;12:441–448. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2001.0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stock D., Leslie A. G. W., Walker J. E. Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science (Washington, DC) 1999;86:1700–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fillingame R. H., Dmitriev O. Y. Structural model of the transmembrane Fo rotary sector of H+-transporting ATP synthase derived by solution NMR and intersubunit cross-linking in situ. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1565:232–245. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(02)00572-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fillingame R. H., Angevine C. M., Dmitriev O. Y. Mechanics of coupling proton movements to c-ring rotation in ATP synthase. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aksimentiev A., Balabin I. A., Fillingame R. H., Schulten K. Insights into the molecular mechanism of rotation in the F0 sector of ATP synthase. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1332–1344. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74205-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angevine C. M., Herold K. A. G., Fillingame R. H. Aqueous access pathways in subunit a of rotary ATP synthase extend to both sides of the membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:13179–13183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2234364100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vazquez-Memije M. E., Shanske S., Santorelli F. M., Kranz-Eble P., DeVivo D. C., DiMauro S. Comparative biochemical studies of ATPases in cells from patients with the T8993G or T8993C mitochondrial DNA mutations. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1998;21:829–836. doi: 10.1023/a:1005418718299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houstek J., Klement P., Hermanskà J., Houstkovà H., Hansikovà H., Van den Bogert C., Zeman J. Altered properties of mitochondrial ATP-synthase in patients with a T→G mutation in the ATPase 6 (subunit a) gene at position 8993 of mtDNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1271:349–357. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00063-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nijtmans L. G., Henderson N. S., Attardi G., Holt I. J. Impaired ATP synthase assembly associated with a mutation in the human ATP synthase subunit 6 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6755–6762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manfredi G., Gupta N., Vazquez-Memije M. E., Sadlock J. E., Spinazzola A., DeVivo D. C., Schon E. A. Oligomycin induces a decrease in the cellular content of a pathogenic mutation in the human mitochondrial ATPase 6 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:9386–9391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T., Hatefi Y. Studies on the mechanism of oxidative phosphorylation: effects of specific F0 modifiers on ligand-induced conformation changes of F1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:7550–7554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Penefsky H. S. Mechanism of inhibition of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase by dicyclohexylcarbodiimide and oligomycin: relationship to ATP synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:1589–1593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solaini G., Harris D. E. Biochemical dysfunction in heart mitochondria exposed to ischaemia and reperfusion. Biochem. J. 2005;390:377–394. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manfredi G., Fu J., Ojaimi J., Sadlock J. E., Kwong J. Q., Guy J., Schon E. A. Rescue of a deficiency in ATP synthesis by transfer of MTATP6, a mitochondrial DNA-encoded gene, to the nucleus. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:394–399. doi: 10.1038/ng851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srivastava S., Moraes C. T. Manipulating mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy by a mitochondrially targeted restriction endonuclease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:3093–3099. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.26.3093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka M., Borgeld H.-J., Zhang J., Muramatsu S., Gong J.-S., Yoneda M. Gene therapy for mitochondrial disease by delivering restriction endonuclease SmaI into mitochondria. J. Biomed. Sci. 2002;9:534–541. doi: 10.1159/000064726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rastogi V. K., Girvin M. E. Structural changes linked to proton translocation by subunit c of the ATP synthase. Nature (London) 1999;402:263–268. doi: 10.1038/46224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]