Abstract

Objective: To assess functional relationship by calculating inter- and intra-hemispheric electroencephalography (EEG) coherence at rest and during a working memory task of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Methods: The sample consisted of 69 subjects: 35 patients (n=17 males, n=18 females; 52~71 years old) and 34 normal controls (n=17 males, n=17 females; 51~63 years old). Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) of two groups revealed that the scores of MCI patients did not differ significantly from those of normal controls (P>0.05). In EEG recording, subjects were performed at rest and during working memory task. EEG signals from F3-F4, C3-C4, P3-P4, T5-T6 and O1-O2 electrode pairs are resulted from the inter-hemispheric action, and EEG signals from F3-C3, F4-C4, C3-P3, C4-P4, P3-O1, P4-O2, T5-C3, T6-C4, T5-P3 and T6-P4 electrode pairs are resulted from the intra-hemispheric action for delta (1.0~3.5 Hz), theta (4.0~7.5 Hz), alpha-1 (8.0~10.0 Hz), alpha-2 (10.5~13.0 Hz), beta-1 (13.5~18.0 Hz) and beta-2 (18.5~30.0 Hz) frequency bands. The influence of inter- and intra-hemispheric coherence on EEG activity with eyes closed was examined using fast Fourier transformation from the 16 sampled channels. Results: During working memory tasks, the inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherences in all bands were significantly higher in the MCI group in comparison with those in the control group (P<0.05). However, there was no significant difference in inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherences between two groups at rest. Conclusion: Experimental results comprise evidence that MCI patients have higher degree of functional connectivity between hemispheres and in hemispheres during working condition. It suggests that MCI may be associated with compensatory processes during working memory tasks between hemispheres and in hemispheres. Moreover, failure of normal cortical connections may exist in MCI patients.

Keywords: Mild cognitive impairment (MCI), EEG, Coherence, Working memory, Cortical connectivity

INTRODUCTION

Subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) having memory impairment beyond what can be expected for age and education are not yet demented. MCI has been defined as a boundary or transitional state between normal ageing and dementia. Reviews of several studies revealed that those subjects are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) ranging from 1% to 25% per year (Petersen et al., 1999). Therefore, patients with MCI are becoming of interest for treatment trials. Furthermore, those individuals are also becoming the focus of many prediction studies and early intervention trials for AD.

Electroencephalography (EEG) analysis is considered to be useful for assessing cerebral functioning, and is easy to perform and requires minimal cooperation from the patients, thus making this technique useful for clinical evaluation of demented patients. EEG coherence obtained from spectral EEG analysis is a noninvasive technique for studying functional relationships between brain regions. Therefore, EEG coherence is also assumed to reflect functional interactions between neural networks represented on the cortex (Hogan et al., 2003). Numerous studies have shown decrease of coherence between different brain regions in AD (Berendse et al., 2000; Jiang, 2005; Wada et al., 1998). Recently, there has been interest in the application of coherence analysis for examining functional changes associated with the performance of a perceptual or cognitive task. Hogan et al.(2003) indicated that EEG coherence provides additional sources of information on the topography of synchronous oscillatory activity and potential cortico-cortical interactions in cognitive testing.

Working memory is an important cognitive function involving encoding, maintenance and retrieval of temporary information and has become one of the hotspots of learning and memory study. Working memory tasks are known to change functional connectivity (Hogan et al., 2003). To our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined topographical differences between MCI and normal controls in either inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence during memory processing. Therefore, the goal of the present study is to investigate the group differences in inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence at rest and during working memory task for MCI patients and that for normal controls.

METHODS

Subjects

The patient group consisted of 35 patients (18 females and 17 males) who consulted the psychiatric outpatient clinic of the Department of Psychiatry, the Second Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University, China. The patients satisfied DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) for the study diagnosis of MCI and the following criteria: (1) memory complaint, (2) normal activities of daily living, (3) normal general cognitive function, (4) abnormal memory for age, (5) not demented, (6) the course of memory damage was over three months. Their mean age (±SD) was (62.3±6.5) years, range 52~71 years. Each patient was evaluated by the Mini-mental state examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975), clinical dementia rating (CDR) (Hughes et al., 1982), functional assessment staging (FAST) (Reisberg, 1988), and activities of daily living scale (ADL) (Lawton and Brody, 1969). The mean MMSE score (±SD) was 26.6±2.0, range 25~30; the CDR score was 0.5; the FAST result was 3; the ADL score was <22. None of the patients were receiving psychoactive medications such as antipsychotic drugs or cerebral vasodilators. MCI patients were followed up from the community in Hangzhou City, China. Moreover, in order to rule out other organic brain disease, e.g. multiple sub-cortical infarctions with mild cognitive impairment, examination of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or computed tomography (CT) for patient group was applied.

The control group consisted of 34 healthy volunteers (17 females and 17 males) without personal or family history of psychiatric or neurological abnormality. Their mean age was (57.4±4.0) years, range 51~63 years. Their mean MMSE score was 29.1±1.3, range 27~30. The normal controls were also sought from the community population. They were functioning normally in the community and have no cognitive impairment. Patients were not significantly different from controls in age, gender and education. All subjects were right-handed and agreed to participate in this study with full knowledge of the experimental nature of the research.

EEG recording and analysis

During EEG recording the subjects were in a resting state with eyes closed, sitting in a semi-darkened, electrically shielded, sound attenuated room. According to the international 10~20 system, original EEG signals were recorded from scalp electrodes and separate ear electrodes A1 and A2, with electrodes referenced to linked ear lobes. Impedance of electrode/skin was kept below 5000 Ω. The signals were amplified and filtered by a 128-channel electroencephalograph (EEG-NATION 918, Shanghai, China) with an upper frequency cut-off of 60 Hz and 0.1 s time constant. EEGs were recorded at 16 electrode sites: Fp1, Fp2, F3, F4, F7, F8, C3, C4, T3, T4, T5, T6, P3, P4, O1 and O2 electrodes for 10 min for each subject with eyes closed. Names of electrode sites are defined by the rule of international 10~20 system. Selection of segments recorded when eyes were closed but awaked was based on visual inspection of EEG and electro-oculographic (EOG) recordings. Segments containing eye movements, blinks, or muscle activity were excluded from the analysis.

EEG coherence was calculated by the fast Fourier transform (FFT) method. One epoch consisted of 2 s, and 20 artifact-free epochs per subject were processed with a spectral resolution of 0.5 Hz. Coherence between two waveforms x and y was calculated spectrally as

|

, where Gxy( f ) is the mean cross-power density and Gxx( f ) and Gyy( f ) are the respective mean auto-power spectral densities. The details of the method for calculating the coherence are published in (Jiang, 2004; 2005). In this study, inter-hemispheric EEG coherence was measured between the following 5 homologous electrode pairs: frontal (F3-F4), left-right centrals (C3-C4), left-right parietals (P3-P4), left-right temporal (T5-T6) and left-right occipitals (O1-O2); intra-hemispheric EEG coherence was measured between the following 10 electrode pairs: left-right fronto-central (F3-C3, F4-C4), left-right centro-parietal (C3-P3, C4-P4), left-right parieto-occipital (P3-O1, P4-O2), left-right temporo-central (T5-C3, T6-C4) and left-right temporo-parietal (T5-P3, T6-P4). The coherence coefficients were calculated and banded into delta band (1.0~3.5 Hz), theta band (4.0~7.5 Hz), alpha-1 band (8.0~10.0 Hz), alpha-2 band (10.5~13.0 Hz), beta-1 band (13.5~18.0 Hz) and beta-2 band (18.5~30.0 Hz).

Working memory task

After routine EEG examination, a working memory task was performed by each subject. In relation to working memory task, studies have generally been reported by deToledo-Morrell et al.(1991) involving Sternberg-type memory scanning task (Sternberg, 1969). Our paradigm was designed to replicate the sums (arithmetic) with three levels of working memory load, recitation of three-digit numbers and mental calculation based on Salthouse and Babcock (1991). First level of working memory is two simple unit numerals added one time, the second level is two simple unit numeral added two times, and the third level is two simple unit numeral added three times. The subjects were asked to remember the answer during every level of working memory task. Along with the increased working memory demands, EEG was recorded during the process of each question being given until the question was answered. In this paper, we focused on first level of working memory data.

Statistics

In this study, a logarithmic transformation of absolute power and Fisher’s Z transformation of coherence values of each band in each derivation were implemented to normalize the distribution of power and coherence values, respectively. Differences between the MCI patients and the normal controls were analyzed on each frequency band by using two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) with a grouping factor (patients vs controls) and a within-subject factor (electrode position). As the EEG recording method for analysis of inter-hemispheric coherence within subject factor, electrode pair involved five levels; for analysis of intra-hemispheric coherence within subject factor, electrode pair involved ten levels. Separate ANOVAs were conducted for different frequency bands in order to test inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence, respectively. The testing conditions, such as resting and working memory state, were used as condition variables. Then, two-tailed student’s t-test was conducted to compare the values of inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence between the two groups. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

RESULTS

Inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence at rest

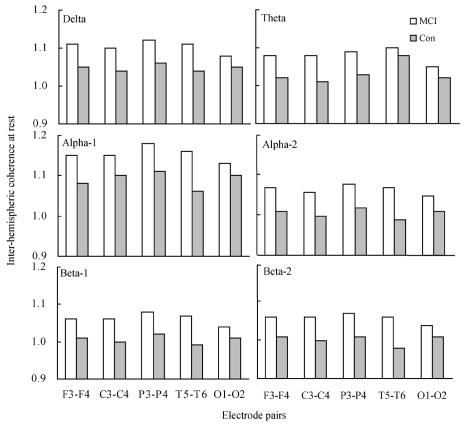

Table 1 and Fig.1 show the inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence values at rest for the controls and MCI on different frequency bands. In the resting condition, no significant group difference was found by ANOVA for inter-hemispheric EEG coherence in the delta [F(1, 4)=2.862, P=0.095], theta [F(1, 4)=2.436, P=0.123], alpha-1 [F(1, 4)=3.150, P=0.080], alpha-2 [F(1, 4)=2.565, P=0.114], beta-1 [F(1, 4)=2.514, P=0.117] and beta-2 [F(1, 4)=2.801, P=0.099] bands; and for intra-hemispheric EEG coherence in the delta [F(1, 9)=1.424, P=0.237], theta [F(1, 9)=1.280, P=0.262], alpha-1 [F(1, 9)=1.645, P=0.204], alpha-2 [F(1, 9)=1.152, P=0.287], beta-1 [F(1, 9)=1.134, P=0.291] and beta-2 [F(1, 9)=1.103, P=0.297] bands.

Table 1.

Intra-hemispheric EEG coherence values (mean±SD) at rest

| Delta | Theta | Alpha-1 | Alpha-2 | Beta-1 | Beta-2 | ||

| F3-C3 | MCI | 1.42±0.11 | 1.37±0.10 | 1.47±0.12 | 1.36±0.11 | 1.36±0.11 | 1.35±0.10 |

| Con | 1.37±0.13 | 1.33±0.13 | 1.45±0.13 | 1.33±0.13 | 1.32±0.13 | 1.32±0.13 | |

| C3-P3 | MCI | 1.42±0.11 | 1.37±0.11 | 1.49±0.11 | 1.36±0.11 | 1.36±0.10 | 1.35±0.10 |

| Con | 1.40±0.14 | 1.36±0.14 | 1.47±0.15 | 1.35±0.14 | 1.34±0.14 | 1.34±0.14 | |

| P3-O1 | MCI | 1.42±0.10 | 1.37±0.10 | 1.49±0.11 | 1.36±0.10 | 1.36±0.09 | 1.35±0.09 |

| Con | 1.39±0.15 | 1.34±0.15 | 1.45±0.16 | 1.33±0.15 | 1.33±0.15 | 1.32±0.15 | |

| T5-C3 | MCI | 1.28±0.10 | 1.23±0.10 | 1.34±0.11 | 1.21±0.10 | 1.21±0.10 | 1.12±0.10 |

| Con | 1.23±0.11 | 1.19±0.11 | 1.30±0.11 | 1.17±0.11 | 1.17±0.11 | 1.16±0.11 | |

| T5-P3 | MCI | 1.29±0.08 | 1.24±0.08 | 1.36±0.09 | 1.23±0.08 | 1.22±0.08 | 1.22±0.08 |

| Con | 1.25±0.11 | 1.20±0.11 | 1.31±0.11 | 1.19±0.11 | 1.19±0.11 | 1.18±0.11 | |

| F4-C4 | MCI | 1.42±0.14 | 1.37±0.13 | 1.48±0.14 | 1.36±0.13 | 1.35±0.13 | 1.34±0.12 |

| Con | 1.39±0.14 | 1.35±0.14 | 1.45±0.15 | 1.34±0.14 | 1.34±0.14 | 1.33±0.14 | |

| C4-P4 | MCI | 1.40±0.10 | 1.36±0.09 | 1.47±0.10 | 1.35±0.10 | 1.35±0.10 | 1.34±0.09 |

| Con | 1.37±0.15 | 1.33±0.14 | 1.44±0.15 | 1.32±0.15 | 1.32±0.15 | 1.31±0.15 | |

| P4-O2 | MCI | 1.41±0.12 | 1.37±0.11 | 1.48±0.12 | 1.35±0.11 | 1.35±0.11 | 1.34±0.11 |

| Con | 1.40±0.13 | 1.35±0.12 | 1.45±0.13 | 1.34±0.13 | 1.34±0.13 | 1.33±0.13 | |

| T6-C4 | MCI | 1.29±0.08 | 1.25±0.08 | 1.36±0.09 | 1.23±0.07 | 1.23±0.07 | 1.22±0.07 |

| Con | 1.26±0.11 | 1.21±0.11 | 1.32±0.11 | 1.20±0.11 | 1.20±0.11 | 1.19±0.11 | |

| T6-P4 | MCI | 1.29±0.10 | 1.25±0.09 | 1.36±0.10 | 1.23±0.09 | 1.23±0.09 | 1.22±0.09 |

| Con | 1.24±0.10 | 1.21±0.10 | 1.31±0.11 | 1.19±0.10 | 1.19±0.10 | 1.18±0.10 |

Note: Coherence values transformed to Fisher’s Z scores, compared between two groups (two-tailed t-test); MCI: The patients with MCI; Con: The normal controls

Fig. 1.

Inter-hemispheric EEG coherence values at rest at different electrode pairs in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients and controls (Con)

Inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence during working memory

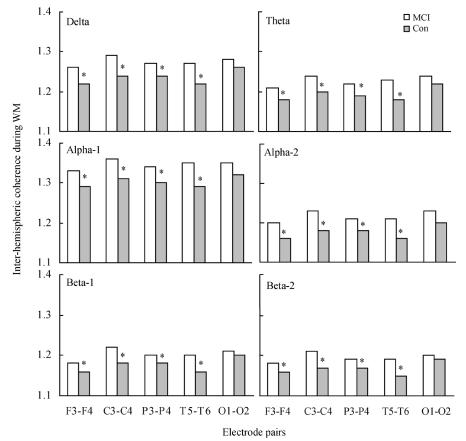

Fig.2 shows inter-hemispheric EEG coherence during working memory in different bands for the controls and MCI patients. Two-way ANOVA revealed that significant group differences were observable during working memory in the delta [F(1, 4)=18.435, P=0.000], theta [F(1, 4)=18.010, P=0.000], alpha-1 [F(1, 4)=19.283, P=0.000], alpha-2 [F(1, 4)=19.316, P=0.000], beta-1 [F(1, 4)=18.186, P=0.000] and beta-2 [F(1, 4)=15.231, P=0.005] bands. A subsequent t-test showed that MCI patients had significantly higher inter-hemispheric EEG coherence at all electrode pairs in all bands (P<0.05), except at O1-O2 electrode pair.

Fig. 2.

Inter-hemispheric EEG coherence values during working memory (WM) at different electrode pairs in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients and controls (Con)

* P<0.05

During working memory, there are significant group differences of intra-hemispheric EEG coherence for the controls and MCI patients in the delta [F(1, 9)=18.435, P=0.000], theta [F(1, 9)=18.010, P=0.000], alpha-1 [F(1, 9)=19.283, P=0.000], alpha-2 [F(1, 9)=19.316, P=0.000], beta-1 [F(1, 9)=18.186, P=0.000] and beta-2 [F(1, 9)=15.231, P=0.005] bands. As shown in Table 2, post-hoc analysis by t-test indicated that MCI patients had significantly higher intra-hemispheric EEG coherence in the F3-C3, F4-C4, C3-P3, C4-P4 and T5-P3 pairs in all bands (P<0.05). In addition, higher coherence values were found in T5-P3 pair for delta band, P4-O2 pair for alpha-1 band.

Table 2.

Intra-hemispheric EEG coherence values (mean±SD) during working memory

| Delta | Theta | Alpha-1 | Alpha-2 | Beta-1 | Beta-2 | ||

| F3-C3 | MCI | 1.27±0.10** | 1.23±0.10** | 1.30±0.10* | 1.23±0.10* | 1.23±0.10** | 1.22±0.10** |

| Con | 1.20±0.11 | 1.17±0.10 | 1.23±0.11 | 1.16±0.10 | 1.16±0.10 | 1.15±0.10 | |

| C3-P3 | MCI | 1.30±0.10* | 1.27±0.11* | 1.35±0.11* | 1.26±0.11* | 1.26±0.11* | 1.25±0.11* |

| Con | 1.23±0.10 | 1.21±0.11 | 1.27±0.10 | 1.20±0.11 | 1.20±0.11 | 1.19±0.11 | |

| P3-O1 | MCI | 1.27±0.14 | 1.23±0.14 | 1.31±0.13 | 1.23±0.14 | 1.22±0.14 | 1.22±0.14 |

| Con | 1.21±0.12 | 1.18±0.12 | 1.25±0.12 | 1.18±0.12 | 1.18±0.13 | 1.17±0.12 | |

| T5-C3 | MCI | 1.10±0.07* | 1.07±0.07 | 1.15±0.07 | 1.06±0.07 | 1.05±0.07 | 1.05±0.07 |

| Con | 1.06±0.10 | 1.03±0.09 | 1.10±0.11 | 1.02±0.09 | 1.02±0.19 | 1.01±0.09 | |

| T5-P3 | MCI | 1.12±0.07** | 1.09±0.07** | 1.17±0.07** | 1.08±0.07** | 1.08±0.07** | 1.08±0.07* |

| Con | 1.06±0.09 | 1.03±0.09 | 1.10±0.11 | 1.02±0.09 | 1.02±0.09 | 1.02±0.09 | |

| F4-C4 | MCI | 1.26±0.09* | 1.23±0.09* | 1.31±0.10** | 1.22±0.09** | 1.22±0.09** | 1.21±0.10* |

| Con | 1.20±0.10 | 1.17±0.10 | 1.23±0.10 | 1.16±0.09 | 1.16±0.09 | 1.16±0.09 | |

| C4-P4 | MCI | 1.28±0.10** | 1.25±0.10** | 1.33±0.12** | 1.25±0.11** | 1.24±0.10** | 1.24±0.10* |

| Con | 1.18±0.09 | 1.15±0.09 | 1.21±0.08 | 1.14±0.09 | 1.14±0.09 | 1.13±0.08 | |

| P4-O2 | MCI | 1.23±0.14 | 1.20±0.14 | 1.28±0.14* | 1.20±0.14 | 1.19±0.14 | 1.18±0.14 |

| Con | 1.17±0.14 | 1.14±0.14 | 1.20±0.15 | 1.13±0.14 | 1.13±0.14 | 1.12±0.14 | |

| T6-C4 | MCI | 1.08±0.08 | 1.04±0.08 | 1.12±0.09 | 1.04±0.08 | 1.04±0.09 | 1.04±0.09 |

| Con | 1.06±0.07 | 1.03±0.07 | 1.10±0.08 | 1.02±0.07 | 1.01±0.07 | 1.01±0.07 | |

| T6-P4 | MCI | 1.10±0.08 | 1.06±0.08 | 1.14±0.09 | 1.05±0.08 | 1.05±0.08 | 1.05±0.08 |

| Con | 1.07±0.06 | 1.04±0.06 | 1.11±0.06 | 1.03±0.06 | 1.03±0.06 | 1.02±0.06 |

Note: Coherence values transformed to Fisher’s Z scores, compared between two groups (two-tailed t-test); MCI: The patients with MCI; Con: The normal controls

P<0.05

P<0.01

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence in 35 MCI patients and 34 normal controls. The analysis of EEG coherence under the resting condition showed no significant group differences for any frequency band, as shown in Fig.1 and Table 1. These results are consistent with the experimental results reported by Stam et al.(2003). They revealed that there are no significant changes in EEG synchronization likelihood, a new measure method combining estimation of linear and nonlinear coupling, in the MCI group compared with controls. Moreover, Jelic et al.(2000) and Jiang (2005) reported that, in MCI, no EEG abnormalities were present. Consequently, it is suggested that disease-related changes in early stage of MCI may be little apparent during rest, thus, there were no differences in the EEG coherence between MCI and controls.

In contrast to the resting condition, the MCI patients had significantly higher inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence than that of the normal controls during working memory task, as seen in Fig.2 and Table 2. The EEG coherence can be interpreted as a quantitative measure of the degree of connectivity between distinct brain regions, and higher coherence is generally presumed to reflect greater function linkage. Thus, the present findings suggested that MCI patients may have a higher degree of inter- and intra-hemispheric functional connectivity during working memory task compared with normal controls under the working condition.

It is known that cognitive performance is supported by a network composed by brain cortical regions (Hogan et al., 2003). In relation to memory processes, studies on healthy humans have generally reported an increase of synchronization between two different brain regions involved in the respective task. Moreover, the patterns of high coherence between EEG signals recorded at different scalp sites have functional significance and can be correlated with different kinds of cognitive information processing, such as memory, language, concept retrieval and music processing (Hogan et al., 2003). The experimental results, shown in Fig.2 and Table 2, suggest that MCI patients and normal controls had differences in cortical connection, and that MCI may suffer localized damage and connectional disturbance of cortical regions.

The working memory is related to information encoding, maintenance and decoding process. Moreover, working memory tasks are known to change the cerebral function connectivity (Hogan et al., 2003). Thus, working memory tasks would result in changes of the value of coherence. The experimental results in the present work also suggest that MCI patients may be associated with early signs of cortical atrophy and/or compensatory cortical reorganization. Furthermore, the change of the EEG sign for cortical functional connectivity for MCI patients is more distinctly apparent during the performance of cognitive task than that at rest. In contrast, it seemed that there was no such compensatory process in the control group during working memory task.

Multiple brain areas, including the lateral prefrontal cortex, mediotemporal areas and posterior association cortex are functionally involved in working memory. In this study, in inter-hemispheric EEG coherence, MCI group had significantly higher values of in bilateral frontal (F3-F4), central (C3-C4), parietal (P3-P4) and temporal (T5-T6) lobes in all bands, except for bilateral occipital band (O1-O2), during working memory compared to the normal control. In intra-hemispheric EEG coherence, MCI had significantly higher values in left fronto-central (F3-C3), centro-parietal (C3-P3), temporo-parietal (T5-P3), right fronto-central (F4-C4), centro-parietal (C4-P4). The temporal lobe, hippocampus and other related cortexes play an important role in cholinergic activity in the central nerve centre, and the parietal lobe is responsible for collating all information into an entire perception. Both lobes are physical bases in cognition function. Recent neuroimage studies have provided experimental evidences that the parietal lobes are more sensitive during cognitive performance (Xie et al., 2003). Consequently, when studying retarded memory, semantic memory and information encoding or decoding, damage related to the temporal lobe, hippocampus, parietal lobe and other cortexes would occur and result in a change of EEG coherence. The experimental results in Table 2 reveal that characteristic neuropsychological and neurophysiological changes would happen during the early stage of MCI. MCI patients had higher compensatory connection during active cognition than that at rest. Moreover, the working memory disturbance is present in MCI with objective memory disturbances.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of Clinic EEG Laboratory, the Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, for their invaluable help with this study.

Footnotes

Project (No. 2003B070) supported by the Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang Province, China

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Ed. Washington, DC: APA Press; 1994. (DSM-IV) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berendse HW, Verburnt JP, Scheltens P, van Dijk BW, Jonkman EJ. Magnetoencephalographic analysis of cortical activity in Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111(4):604–612. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(99)00309-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.deToledo-Morrell L, Evers S, Hoeppner TJ, Morrell F, Garron DC, Fox JH. A ‘stress’ test for memory dysfunction. Electrophysiogical manifestations of early Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:605–609. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1991.00530180061018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hogan MJ, Swanwick GRJ, Kaiser J, Rowan M, Lawlor B. Memory-related EEG power and coherence reduction in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Psychophysiol. 2003;49(2):147–163. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(03)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RA. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jelic V, Johansson SE, Almkvist O. Quantitative electroencephalography in mild cognitive impairment: longitudinal changes and possible prediction of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(4):533–540. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(00)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang ZY. Research of diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease based on coherence analysis of EEG signal. Chinese J Sensor Actuator. 2004;17(3):363–366. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang ZY. Abnormal cortical functional connections in Alzheimer’s disease: analysis of inter- and intra-hemispheric EEG coherence. J Zhejiang Univ SCI. 2005;6B(4):259–264. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2005.B0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawton WP, Brody MP. Assessment of older people self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnic RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(3):303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reisberg B. Functional assessment staging (FAST). Psychopharmacal. Bull. 1988;24:653–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salthouse TA, Babcock RL. Decomposing adult age difference in working memory. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(5):763–776. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.5.763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stam CJ, van der Made Y, Pijnenburg YAL, Scheltens P. EEG synchronization in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108(2):90–96. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sternberg S. Memory-scanning: mental processes revealed by reaction-time experiments. Am Sci. 1969;57:421–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wada Y, Nanbu Y, Koshino Y, Yamaguchi N, Hashimoto T. Reduced interhemispheric EEG coherence in Alzheimer disease: analysis during rest and photic stimulation. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1998;12:175–181. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199809000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie S, Xiao JX, Jiang XX. The fMRI study of the calculation tasks in normal aged volunteers. J Peking Univ, (Health Sci) 2003;35(3):311–313. (in Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]