Abstract

Gfh1, a transcription factor from Thermus thermophilus, inhibits all catalytic activities of RNA polymerase (RNAP). We characterized the Gfh1 structure, function and possible mechanism of action and regulation. Gfh1 inhibits RNAP by competing with NTPs for coordinating the active site Mg2+ ion. This coordination requires at least two aspartates at the tip of the Gfh1 N-terminal coiled-coil domain (NTD). The overall structure of Gfh1 is similar to that of the Escherichia coli transcript cleavage factor GreA, except for the flipped orientation of the C-terminal domain (CTD). We show that depending on pH, Gfh1-CTD exists in two alternative orientations. At pH above 7, it assumes an inactive ‘flipped' orientation seen in the structure, which prevents Gfh1 from binding to RNAP. At lower pH, Gfh1-CTD switches to an active ‘Gre-like' orientation, which enables Gfh1 to bind to and inhibit RNAP.

Keywords: active center, inhibitor, RNA polymerase, transcription elongation factors, transcription regulation

Introduction

Transcriptional activity of RNA polymerase (RNAP) is controlled by a large number of regulatory factors. Only few of them are known to modulate RNAP activity by directly affecting its catalytic center (Nickels and Hochschild, 2004). In prokaryotes, these include transcription elongation factors Gre (GreA and GreB), which stimulate nucleolytic activity of RNAP and increase the overall transcription efficiency and fidelity (Fish and Kane, 2002; Borukhov et al, 2005; Greive and von Hippel, 2005), and DksA, which amplifies the effects of ppGpp, an effector of bacterial stringent control, on transcription initiation from several essential promoters (Paul et al, 2004; Perederina et al, 2004). Although Escherichia coli DksA and Gre are not homologous, they share a structural similarity in their extended N-terminal coiled-coiled domains (NTDs) (Perederina et al, 2004). Both Gre and DksA bind RNAP, and deliver their NTDs through the secondary channel of RNAP to the catalytic center. GreA and GreB directly participate in the catalysis of the nascent RNA hydrolysis by donating two acidic residues on the tip of NTD to coordinate the second Mg2+ ion in the active center of RNAP (Laptenko et al, 2003; Opalka et al, 2003; Sosunova et al, 2003). DksA, on the other hand, acts through ppGpp, possibly by coordinating its Mg2+ ion and stabilizing the RNAP–ppGpp complex (Paul et al, 2004; Perederina et al, 2004). In eukaryotes, a functional equivalent of GreA/GreB, elongation factor TFIIS, also acts through the Pol II secondary channel in a manner similar to Gre (Kettenberger et al, 2003, 2004).

In thermophilic bacteria of the Thermus genus, two transcription factors, GreA and Gfh1 (previously named GreA1 and GreA2, respectively) share substantial sequence similarity with members of the GreA/GreB family of transcription factors (Laptenko et al, 2000; Hogan et al, 2002; Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003). Thermus thermophilus (Tth) and Thermus aquaticus GreA stimulate RNA cleavage in ternary elongation complexes (TCs) formed by cognate RNAPs in manner similar to that of E. coli GreA, facilitate transcription elongation, and increase transcription fidelity. Gfh1, on the other hand, lacks any transcript cleavage activity, but competes with GreA for binding to RNAP and appears to be a general inhibitor/repressor of RNAP catalytic functions (Laptenko et al, 2003; Symersky et al, 2006). Localized protein footprinting assays show that the tip of Gfh1–NTD reaches the catalytic center in Gfh1–RNAP complex, implying that Gfh1 also acts through the RNAP secondary channel (Laptenko et al, 2003). Indeed, the structure of Tth Gfh1 shows an overall similarity to the known structure of E. coli GreA, with a notable exception of flipped C-terminal domain (CTD) (Lamour et al, 2006; Symersky et al, 2006; see below). However, the molecular mechanism of Gfh1 action and its biological role are unknown.

Here, we use a combination of genetic, biochemical, and X-ray crystallographic methods to characterize the Gfh1 structure, function, and possible mechanisms of action and regulation. We show that Gfh1 inhibits RNAP by partially occluding its substrate-binding site and by competing with NTPs for coordination of the active center Mg2+ ion. We provide evidence that inhibitory activity of Gfh1 is regulated through a pH-induced conformational change of its structure.

Results

Gfh1 is a transcriptional inhibitor in vitro

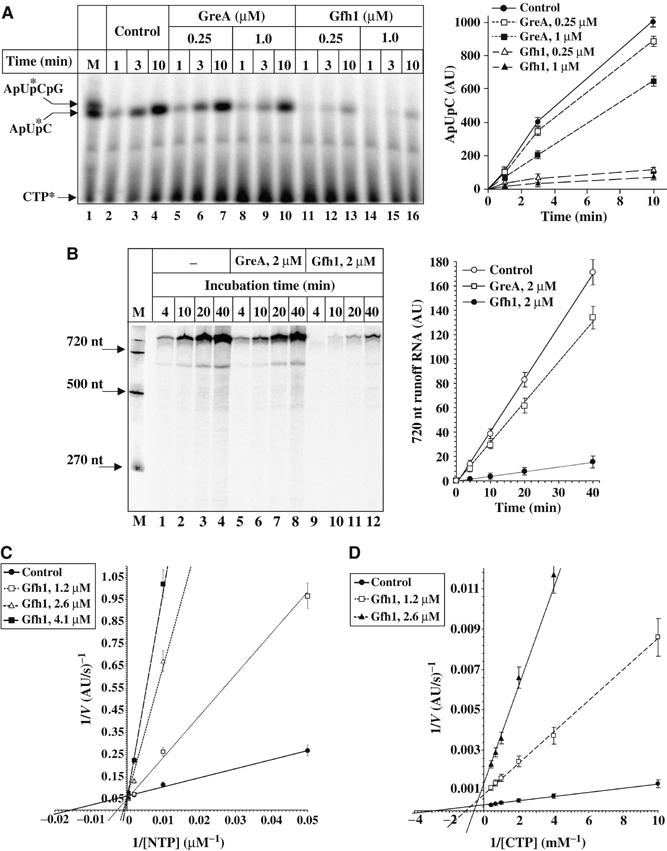

Standard in vitro transcription assays using different promoter DNA templates (see Materials and methods) revealed that Gfh1 inhibits all catalytic activities of RNAP including intrinsic and GreA-mediated transcript cleavage, RNA synthesis during abortive initiation and elongation, pyrophosphorolysis, and multiround transcription (Figure 1A and B and Supplementary Figure S1A–D; Laptenko et al, 2000, 2003; Hogan et al, 2002; Symersky et al, 2006). Depending on experimental conditions, the overall inhibitory effect of Gfh1 on RNA synthesis or pyrophosphorolysis can be 50-fold. The effect of Gfh1 on multiround transcription varied from three-fold on the Tth nrc promoter to >10-fold on the Tth nqo and the T7 A1 promoters. These effects were observed at 1 mM substrate concentration, which is close to physiological concentrations of NTPs in E. coli, indicating that Gfh1 could be a potent inhibitor in vivo.

Figure 1.

Analysis of Gfh1 inhibitory activity by in vitro transcription assays. (A) Abortive initiation. Left panel is the autoradiogram of urea–23% PAGE, which shows a time course of ApUpC synthesis in the presence or absence of protein factors at indicated concentrations. Each reaction contained 80 nM T7A1-50 promoter DNA, 0.3 μM Tth RNAP, 0.3 mM ApU, 50 μM CTP, and [α-32P]CTP (0.9 Ci/mmol). Positions of size markers are shown under ‘M'. Kinetics graph on the right is a quantification of the autoradiogram on the left. Here and elsewhere in text, the amount of product is expressed in arbitrary units, a.u. (1 a.u.=10 PhosphorImager counts). (B) Multiround runoff assay. Left panel is the autoradiogram of urea–8% PAGE showing a time course of 720-nt-long runoff transcript synthesis. Each reaction contained 15 nM T7A1-720 DNA, 25 nM Tth RNAP, 0.3 mM ApU, 1 mM each NTPs, [α-32P]ATP (0.15 Ci/mmol), and 50 μg/ml heparin incubated in the presence or absence of protein factors at indicated concentrations. Kinetics graph on the right is a quantification of the autoradiogram. DNA size markers are indicated on the left. (C) and (D) Double reciprocal plots showing the rate dependence of RNAP elongation (C) and abortive initiation (D) on substrate concentration under indicated conditions. Abortive synthesis reactions were carried out as in (A). For transcription elongation, each reaction containing 2–5 nM of the initial radiolabeled TC-20A obtained on T7A1-50 promoter (Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003) were incubated at 40°C for 1–10 min with different concentrations of NTPs in the presence or absence of protein factors. The initial rates of 50-mer runoff RNA (C) and ApUpC synthesis (D) were measured at 0.04–2 mM NTPs or 0.1–2.5 mM CTP, respectively.

To determine whether Gfh1 is a competitive, noncompetitive, or uncompetitive inhibitor, we measured its activity as a function of substrate concentration in quantitative abortive initiation and elongation assays (Figure 1C and D, and Supplementary S1E–G) using the T7 A1 promoter. The results of both assays show that the inhibitory effect measured as a decrease in the rate of RNA synthesis in the presence of Gfh1 is inversely proportional to the concentration of NTPs. During transcript elongation (RNA extension from 20 to 50 mer), Gfh1 acts as a competitive inhibitor by reducing the apparent affinity of RNAP to NTPs without affecting the maximum rate of catalysis (kcat). For example, 2.6 μM Gfh1 increases the apparent Km for NTP from 62 μM to 1.5 mM (Figure 1C and Supplementary Figure S1E). The calculated Ki for Gfh1 is in the range of 0.25–0.3 μM. During abortive synthesis of ApUpC, Gfh1 appears to act as a mixed mode inhibitor; at 2.6 μM, it increases the apparent Km for CTP from 0.3 to 1.7 mM, and also decreases the reaction Vmax ∼3-fold (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure S1F). However, Gfh1 is noncompetitive towards the initiating substrate, ApU (Supplementary Figure S1G). Similar results were obtained with ATP as initiating substrate (data not shown). The fact that Gfh1 decreases the Vmax of abortive initiation (which represents a steady-state multiround reaction where the product must be released before each new round of synthesis) but not of elongation (which represents a single turnover reaction where the synthesized product remains in the complex) implies that Gfh1 affects the rate limiting step during abortive synthesis, which most likely is the product release. Since Gfh1 occupies the RNAP secondary channel (Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003), it may inhibit the release of abortive products through this conduit and decrease the turnover rate. Thus, the major mode of Gfh1 action appears to be through competition with substrates.

Gfh1 inhibitory activity resides in the distal half of Gfh1-NTD

The sequence alignment (Supplementary Figure 2) shows that the major difference between Gfh1 and GreA is in a loop connecting the two α-helices of GreA-NTD (residues 40–46) and the flanking regions (residues 29–39 and 47–58). Also, a residue that introduces a kink in the GreA-NTD structure, V24, is absent in Gfh. To identify the structural determinants of the Gfh1 inhibitory activity, we constructed a set of hybrids by swapping the NTD of Gfh1 or its parts with corresponding parts of Tth GreA. A similar approach was very useful in elucidating the structural determinants that confer unique properties to E. coli GreA and GreB (Koulich et al, 1997).

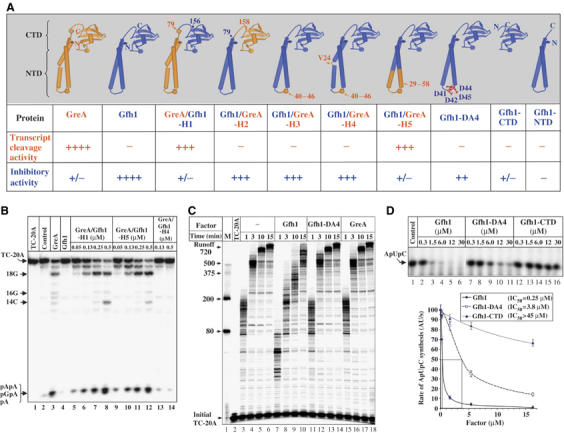

Schematic representations of Tth Gfh1, GreA, their hybrids, and a summary of their functional properties are shown in Figure 2. The results of domain swapping experiment demonstrate that NTDs confer either the Gfh1-like or the GreA-like activity to hybrid proteins (Figure 2A; Gfh1/GreA-H1 and GreA/Gfh1-H2). The individual domains of Gfh1 used as controls are inactive. Further genetic dissection revealed that substituting the distal half of Gfh1-NTD with a corresponding part of GreA abolishes Gfh1 inhibitory function and confers GreA-like transcript cleavage activity (Figure 2A and B; Gfh1/GreA-H5). Thus, the Gfh1 inhibitory activity resides in the distal half of its NTD, within residues 29–58. However, grafting only the loop of GreA NTD (residues 40–46) to Gfh1 (Gfh1/GreA-H3) is insufficient to confer the cleavage activity to Gfh1, and more importantly, causes only a small decrease in its inhibitory activity, indicating that not all four acidic residues in the Gfh1-NTD loop are required for its inhibitory activity. Additional insertion of a valine at position 24 to reproduce the GreA-like kink in NTD has no effect (Gf1h/GreA-H4). The ability of H3 and H4 hybrids to retain the inhibitory activity of Gfh1 could be owing to the presence of conserved D41 and E44 residues in the loop imported from GreA-NTD.

Figure 2.

Functional activities of Gfh1/GreA hybrid and mutant factors. (A) Schematic diagram showing the structure of engineered proteins and summary of their activities. Proteins are color coded to indicate the origin of corresponding part. Activities expressed as ++++, +++, ++, +/−, and − represent 50–100, 20–50, 5–20, 1–5, and <1% of the wt activity, respectively. Inhibitory activity was measured in abortive initiation assay as in (D). (B) The autoradiogram of urea–23% PAGE showing the results of transcript cleavage reactions induced in 20 nM radiolabeled TC-20A after incubation at 60°C for 10 min alone or in the presence of 100 nM GreA, 1 μM Gfh1, or hybrid proteins at indicated concentrations. (C) Autoradiogram of urea–8% PAGE showing the elongation time course of the initial TC-20A incubated at 40°C in the presence or absence of protein factors. Positions of DNA size markers are indicated on the left. (D) Top panel is the autoradiogram of urea–23% PAGE showing the synthesis of ApUpC (see Figure 1A) during 15 min reaction in the presence of wt Gfh1, Gfh1-4DA, or Gfh1-CTD used at different concentrations. Bottom graph shows rate dependence of ApUpC synthesis as a function of protein concentration. Estimated values of IC50 are indicated in the inset.

To determine the functional role of acidic residues in the Gfh1-NTD loop, we constructed a mutant Gfh1, Gfh1-DA4, in which all four aspartates of the loop are substituted by alanine. Functional assays revealed that the inhibitory activity of Gfh1-DA4 is severely compromised (Figure 2C and D). In contrast to wt Gfh1, even 4.2 μM of Gfh1-DA4 fails to inhibit RNA synthesis during transcription elongation in the presence of 1 mM NTPs (Figure 2C). However, a small inhibitory effect of Gfh1-DA4 can be observed when less than 100 μM NTPs are used (Supplementary Figure S2B). In a more sensitive abortive initiation assay, Gfh1-DA4 moderately decreases the rate of ApUpC synthesis (Figure 2D). However, ∼15 times higher concentration of Gfh1-DA4 (compared to the wt Gfh1) is required to achieve 50% inhibition. It also shows only a weak competitive inhibition towards CTP (Supplementary Figure S2C). Thus, at least two aspartates at the tip of Gfh1-NTD loop are necessary for efficient inhibitory activity of Gfh1.

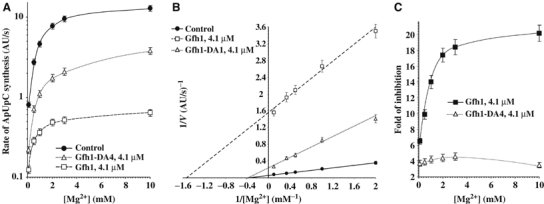

Acidic residues of the Gfh1-NTD loop coordinate Mg2+ ion in the RNAP substrate-binding site

The conservation of acidic residues in the NTD loop and their functional importance in both Gfh1 and Gre suggest that they act on the same target in RNAP, specifically, the second metal ion in the RNAP catalytic center (Borukhov et al, 2005). Symersky et al (2006) and Lamour et al (2006) also speculate on a possible role of the four acidic residues of Gfh-NTD in chelation of catalytic Mg2+ ion and in substrate occlusion; however, no experiments to address these questions were conducted. To define the functional roles of these residues, we analyzed the dependence of inhibitory activity of Gfh1 and Gfh1-DA4 on the concentration of divalent metal ions, Mg2+, Co2+, and Ni2+, all of which can support the catalytic activities of RNAP (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S3). The results show that during abortive synthesis of ApUpC on the T7 A1 promoter, Gfh1 increases the apparent affinity of RNAP to Mg2+ ∼5-fold, whereas Gfh1-DA4 does not cause any noticeable effect (Figure 3A and B). Surprisingly, the relative inhibitory effect of Gfh1, but not Gfh1-DA4, strongly depends on the concentration of Mg2+ (∼6-fold inhibition at 0.2 mM Mg2+ versus ∼22-fold inhibition at 10 mM Mg2+; Figure 3C). This relationship is even more striking when Ni2+ is used as a catalytic ion. At 3 mM Ni2+, Gfh1 causes a ∼60-fold decrease in the rate of abortive synthesis, but at 0.1 mM Ni2+, only a four-fold inhibition is observed (Supplementary Figure 3). Similar results were obtained in transcription elongation assays (data not shown). These results indicate that Gfh1 stabilizes the binding of a metal ion in the catalytic center, most likely through direct coordination by acidic residues of the NTD loop. On the other hand, Gfh1 requires high concentration of metal ion to exert its inhibitory effect. This could be explained by the fact that at low concentration, most metal ions are bound by NTPs to form metal–NTP complexes that bind efficiently to RNAP active site. At high concentrations, however, the metal ions can freely diffuse into the active center where they can be stabilized by Gfh1, which prevents the binding of NTP or Mg2+–NTP. Therefore, it appears that Gfh1 can compete with the substrate only if it coordinates the free metal ion first. Gfh1-DA4 is unable to chelate metal ions but binds RNAP and occupies the secondary channel as efficiently as the wt Gfh1 (data not shown). Therefore, it may exert its residual inhibitory activity simply by limiting the diffusion of NTPs to active center through the secondary channel.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effect of wt Gfh1 and Gfh1-DA4 on abortive synthesis as a function of Mg2+ concentration. (A) Semilogarithmic plot shows the dependence of the initial rates of ApUpC synthesis (see Figure 1A) in the absence or presence of protein factors on Mg2+ concentration. (B) Double reciprocal plot of (A). (C) Graph shows Mg2+ dependence of the inhibitory activity of wt Gfh1 and Gfh1-DA4 during ApUpC synthesis. The data presented are derived form (A).

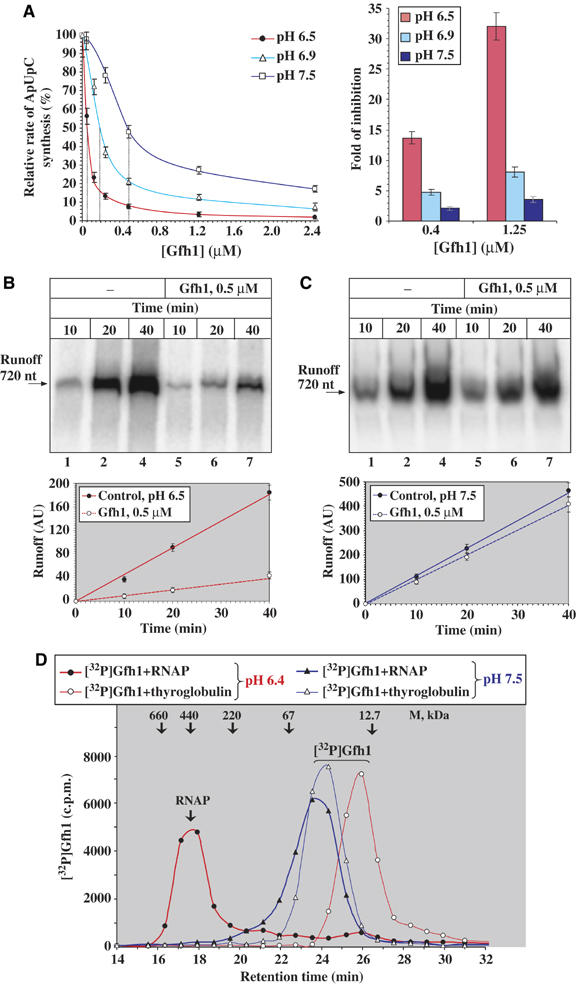

Gfh1 is a pH-sensing transcription factor that responds to a small change in pH

Quantitative analysis of the in vivo expression levels of Gfh1 and GreA by immunoblotting using anti-Gfh1 and anti-GreA antibodies revealed that both proteins are present in Tth cells at 0.5–1 μM concentrations (0.1–0.2 ng/μg of cell lysate; Supplementary Figure S4A), and their amounts remain constant during all growth phases (data not shown). The fact that Gfh1 inhibits all catalytic activities of RNAP in vitro, including transcription elongation in the presence of high concentrations of NTPs, and has an RNAP-binding affinity that is ∼8 times higher that that of GreA (Kd=0.05 μM; Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003) suggests that it should be a strong transcriptional repressor in vivo. Given these facts, it seems likely that the inhibitory activity of Gfh1 is normally suppressed or masked in vivo.

During our studies, we made a serendipitous discovery that Gfh1 inhibitory activity is highly sensitive to small changes of pH within a physiological range. As shown in Figure 4, the concentration of Gfh1 required for 50% inhibition (IC50) of abortive ApUpC synthesis at pH 6.5, 6.9 and 7.5 increases from 0.05 to 0.2 and 0.5 μM, respectively. Or, the fold inhibition of the reaction by 1.25 μM Gfh1 decreases from 35- to seven- to three-fold in the same pH ranges. Similar results are obtained during transcript elongation where inhibitory effect of Gfh1 decreases ∼10-fold upon increase of pH from 6.5 to 7.5 (Supplementary Figure S4B). The inhibitory effect of Gfh1 on the rates of multiround runoff transcription also decreases with increase in pH (Figure 4B and C). The loss of the inhibitory activity at pH 7.5 can be compensated by increasing the concentrations of Gfh1 (Figure 4A), suggesting that Gfh1 binding to RNAP rather than the intrinsic properties of the enzyme is affected by pH. Indeed, the direct RNAP-Gfh1-binding assay (Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003) using size-exclusion HPLC (Figure 4D) demonstrates that in the presence of a two-fold molar excess of RNAP, ∼90% of Gfh1 forms a stable complex with RNAP at pH 6.4, whereas <5% is bound to RNAP at pH 7.5. It should be noted that during chromatography, free Gfh1 behaves as a monomer at both pH. The difference in retention times observed for free radiolabeled Gfh1 at pH 6.4 and 7.5 is apparently owing to an increased nonspecific adsorption of phosphorylated Gfh1 monomer at pH 6.4 to the column matrix (see Figures 4D and 6C legends and Supplementary data for details).

Figure 4.

Inhibitory activity of Gfh1 as a function of pH. (A) Graph on the left shows the dependence of the relative rates of ApUpC synthesis (seeFigures 1A, 2D) on Gfh1 concentrations at pH 6.5, 6.9, and 7.5. Rates are expressed as % of rates of the control reaction at each pH in the absence of Gfh1. Each vertical dotted line indicates Gfh1 IC50. On the right, bar graph shows the effect of pH on the fold of inhibition by 0.4 and 1.2 μM Gfh1. (B) Inhibitory effect of Gfh1 during multiround runoff transcription at T7A1-720 promoter DNA at pH 6.5 (see Figure 1B). Top panel is the autoradiogram of urea–8% PAGE showing a time course of 720-nt-long RNA synthesis in the presence and absence of Gfh1. The graph below shows the quantification of the autoradiogram. (C) Same as (B) at pH 7.5. (D) Effect of pH on Gfh1-RNAP binding. Chromatographic plot shows the radioactivity profiles of free [32P]Gfh1 and [32P]Gfh1–RNAP core complexes during chromatography on Superose 6 column at pH 6.4 and 7.5 (Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003). Retention times and molecular weights of the protein size markers (thyroglobulin, ferritin, catalase, BSA, and cytochrome c) are indicated. The increased retention of radiolabeled Gfh1 (theoretical MW=18.9 kDa) observed at pH 6.4 (∼26 min corresponding to an apparent MW of ∼16 kDa) is owing to nonspecific adsorption of phosphorylated Gfh1 to the column matrix at this pH. Free unphosphorylated Gfh1 elutes from the column with retention time of ∼24.5 min (with an apparent MW of ∼26 kDa), both at pH 6.4 and 7.5 (data not shown).

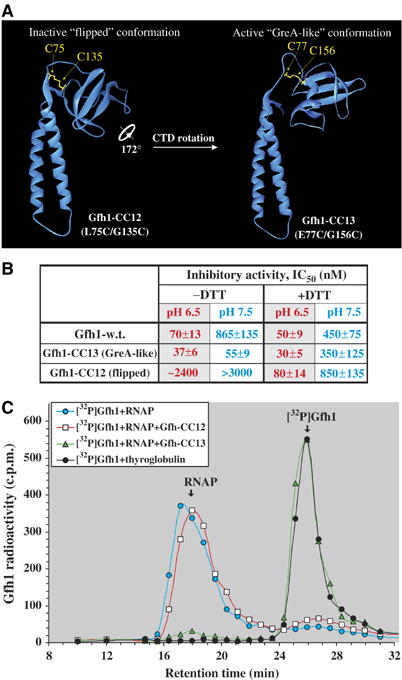

Figure 6.

Effect of CTD conformation on functional activity of Gfh1. (A) Model structures of mutant factors with conformations fixed via S–S bridges, Gfh1-CC12 and Gfh1-CC13 are shown as ribbons. Models were generated by Swiss-Model (Schwede et al, 2003) using the structures of Tth Gfh1 and E. coli GreA as templates, respectively. (B) Summary of the inhibitory activities of wt and mutant Gfh1-CC factors. The IC50 values were obtained from abortive initiation assay as in Figure 4A–C, conducted under indicated conditions. (C) [32P]Gfh1–RNAP competition-binding assay. [32P]Gfh1–RNAP core complex was chromatographed with or without 20 μM competitor proteins, Gfh1-CC12 or Gfh1-CC13, at pH 6.4 under nonreducing conditions (see Figure 4D). Free oxidized forms of Gfh1-CC12 and Gfh1-CC13 all elute irrespective of pH with almost identical retention times of 24.5–24.7 min (the same as that of the wt Gfh1) corresponding to an apparent molecular weight of ∼26 kDa (data not shown), which, according to a light-scattering analysis, represents a monomer (see Supplementary data).

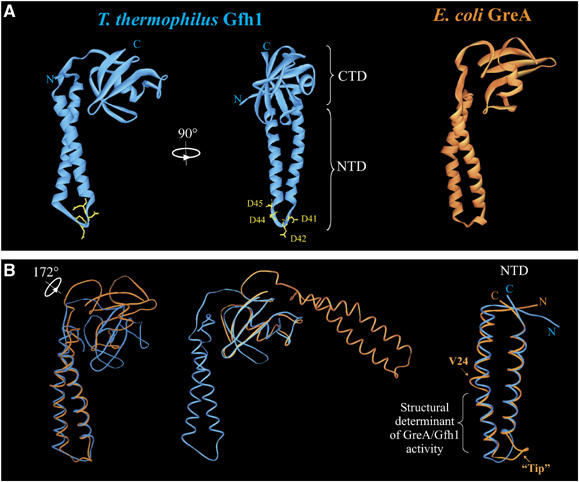

Crystal structure of Gfh1 reveals a ‘flipped' CTD

To assess the possible structural alteration in Gfh1 and to compare it to the known structure of E. coli GreA, we crystallized Gfh1 and determined its structure to 1.6 Å resolution (Supplementary Table S1). There are two molecules in the asymmetric unit in both the monoclinic and orthorhombic crystals, with two NTDs packed against each other (Supplementary Figure S5). Like E. coli GreA (Stebbins et al, 1995), Gfh1 has an elongated ‘L'-shape with two domains: the extended α-helical coiled-coil NTD, and the globular CTD (Figure 5A). Despite the overall similarity, there are several notable differences between the structures of GreA and Gfh1. The first and the most striking is the ‘flipped' orientation of CTD in the Gfh1 structure; it is 172° rotated around an axis tilted about 45° from that of the NTD coiled-coil (Figure 5B). The rotation of the Gfh1-CTD reduces the effective length of its NTD compared to E. coli GreA, potentially limiting its ability to reach the active site of RNAP in this conformation. It also creates a more extensive interface between the CTD and the NTD. While the interdomain contact in GreA is hydrophilic and mediated by solvent molecules (Stebbins et al, 1995), in Gfh1 it is largely hydrophobic, without any solvent molecules in between. Another difference is the absence of bulge (V24 of GreA) in the first α-helix of Gfh1 NTD coiled-coil (Figure 5C). Lastly, in the structure of Gfh1, Asp41 has no electron density at 1σ level, and the densities for the two flanking residues are weak, indicating a potential flexibility of this region of the loop (Figure 5A and C). In the active center of RNAP, however, the loop residues of Gfh1 are likely to be structured owing to metal coordination.

Figure 5.

Crystal structure of Tth Gfh1. (A) Ribbon representation of Gfh1 structure is shown in two orthogonal views (left and central panel). The location of the two domains, NTD and CTD, and the four Asp residues of NTD loop are indicated. The structure of E. coli GreA (Stebbins et al, 1995) is shown for comparison (right panel). (B) Superposition of the structures of E. coli GreA (orange) and Tth Gfh1 (blue) as Cα trace. Left panel shows the alignment by NTD and central panel shows alignment by CTD. Overall, the molecules superimposed well with r.m.s. deviation of the Cα atoms=1.8 Å with more than 90% equivalences. The rotation axis of the CTD is indicated. Right panel shows aligned NTDs, rotated by 60° counterclockwise around the NTD axis from the view shown in the left panel.

Our mutational analysis (Figure 2) indicates that neither the structure of the loop nor the bulge in α-helix of the coiled-coil influences Gfh1 function. The rotation of the CTD, on the other hand, could potentially affect the interaction of Gfh1-NTD with RNAP. As illustrated in Figure 5B, superimposing Gfh1 and GreA structures by aligning the CTDs causes their NTDs to project in directions almost perpendicular to one another. Since Gfh1 and GreA interact with RNAP in a similar manner, requiring binding to RNAP through CTD and insertion of NTD into the secondary channel, only one of the two conformations can be functionally active for Gfh1 and GreA.

Gfh1 binds to RNAP and exerts its inhibitory function only in a ‘GreA-like' conformation

To determine which of the two orientations of CTD is functionally relevant, we constructed Gfh1 mutants with paired cysteine substitutions, which will allow covalent crosslinking of the CTD by intramolecular disulfide (S–S) bridge formation (see Materials and methods). Mutants Gfh1-CC12 and -CC13 harbor double substitutions L75C/G135C and E77C/G156C, respectively, and can each be fixed only in the ‘flipped' or ‘GreA-like' conformation upon oxidation (Figure 6A). The reduced and oxidized forms of both mutant proteins are readily distinguishable by SDS–PAGE (Supplementary Figure S6A). Both CC12 and CC13 are highly susceptible to intramolecular S–S crosslinking under nonreducing conditions at pH 6.5 and 7.5, yielding >90% of crosslinked monomers. Under native conditions, both proteins can be reduced with 10 mM DTT; however, upon storage or 10-fold dilution, 5–10% of the protein becomes oxidized, restoring intramolecular S–S bridges (Supplementary Figure S6). The complete reduction requires boiling in the presence of SDS and 10% β-mercaptoethanol (Supplementary Figure S6A). These results provide strong evidence that Gfh1 can assume two conformations in solution under appropriate conditions.

The mutant and wt Gfh1 factors were compared for their inhibitory activity using abortive initiation assays in the presence or absence of 5 mM DTT, at pH 6.5 or 7.5 (Supplementary Figure S6B). As summarized in Figure 6B, in the absence of DTT, Gfh1-CC13 inhibits abortive synthesis of ApUpC even better than wt Gfh1, whereas Gfh1-CC12 is virtually inactive. Unlike wt Gfh1, both mutant proteins are insensitive to pH. In the presence of 5 mM DTT, all three proteins have similar inhibitory activity and are equally susceptible to pH. Specifically, reduction of S–S bridges restores the inhibitory activity of Gfh1-CC12 to the wt level. The small differences between the inhibitory activities of mutant proteins under reduced condition are probably owing to their incomplete reduction (see Supplementary Figure S6A). Thus, Gfh1 can exert its inhibitory function only in a GreA-like conformation and is inactive in ‘flipped' conformation. Free rotation of Gfh1-CTD is essential for Gfh1 to manifest its pH-response function.

The dependence of Gfh1 activity on pH may reflect a pH-driven conformational switch that either allows or prohibits its binding to RNAP. This is consistent with the results of functional and RNAP-binding assays (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure S4). To prove that the conformational change of Gfh1 is directly responsible for altering the binding affinity to RNAP, we performed a competition binding assay in which the Gfh1-CC12 and -CC13 are allowed to compete under nonreducing conditions with radiolabeled wt Gfh1 for binding to RNAP at pH 6.5. Figure 6C shows that, as expected, Gfh1-CC13 almost quantitatively displaces the wt Gfh1 from the complex with RNAP during size-exclusion chromatography, while CC12 does not.

Taken together, these results strongly support the hypothesis that at pH above 7, the CTD of Gfh1 assumes an inactive ‘flipped' orientation that prevents the binding to RNAP. At lower pH, the CTD of Gfh1 switches to an active ‘Gre-like' orientation, enabling Gfh1 to bind and inhibit RNAP.

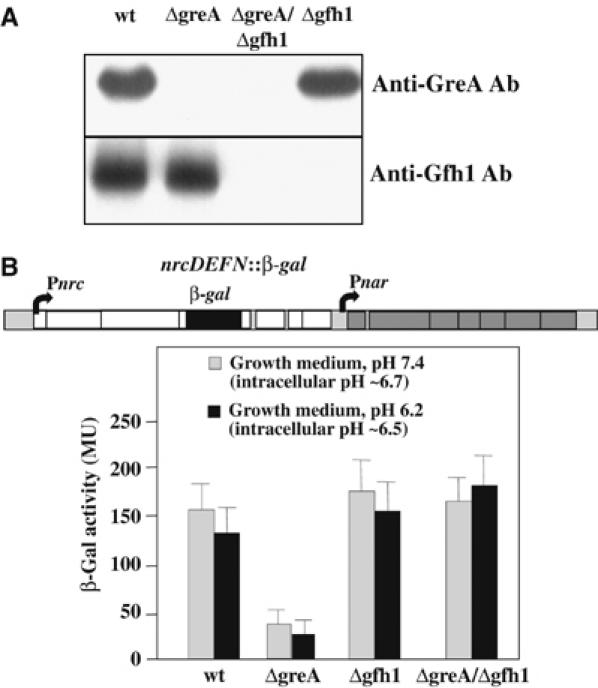

Gfh1 acts as a transcriptional inhibitor in vivo

To test the in vivo activity of Gfh1 and to investigate its possible biological function, we constructed a series of Tth isogenic mutants in which the coding sequences of greA, gfh1, or both were deleted (see Figure 7A and Materials and methods). Although none of these deletions affected cell viability, they each conferred a distinct morphological phenotype. Microscopic analysis (Supplementary Figure S7) revealed a significant decrease in the average cell size of ΔgreA cells, and the presence of vesicles on the surface of Δgfh1cells, which were of normal cell size but frequently with aberrant shapes. The double ΔgfhΔgreA mutant had the small size characteristic of the ΔgreA mutant, and a strong aggregating phenotype. The double mutant strain was also temperature sensitive and failed to grow above 70°C. The morphological phenotypes of single deletion mutants can be complemented by suicidal plasmids carrying the missing greA or gfh1 gene with their natural promoters (data not shown), excluding the possibility of polar effects of the deletions on downstream genes. On the other hand, the temperature-sensitive and aggregative phenotypes of the double mutant strain can be suppressed by either GreA or Gfh1. This suggests that despite their functional antagonism, GreA and Gfh1 may act in concert towards the same phenotypic end in vivo.

Figure 7.

Analysis of in vivo expression levels and activities of Gfh1 and GreA. (A) Western blot analysis of wt Tth (HB-27) and mutant ΔgreA, Δgfh1, and ΔgreA∷Δgfh1 cells grown to log phase in rich TB medium at pH 7.5. Cell lysates were separated by SDS–PAGE and blotted using polyclonal antibodies against purified Tth GreA and Gfh1 as indicated. The blot demonstrates that GreA and Gfh1 were not present in the lysates of corresponding mutant cells. (B) Inhibitory effect of Gfh1 on the expression of nrc operon in vivo. The wt and mutant Tth strains were assayed using the β-Gal reporter expression system (Cava et al, 2004b) shown schematically in top. Below is the bar graph showing β-Gal activities expressed in Miller units (MU) from cell lysates grown at pH 7.4 and 6.2 after 4 h induction.

To analyze quantitatively the inhibitory effect of Gfh1 during gene expression in vivo, we used a reporter system described previously (Cava et al, 2004b) in which the bgaA gene coding for thermostable β-galactosidase (β-Gal) is inserted into the fourth gene of the nitrate respiration nrcDEFN operon in the chromosome of each mutant (Figure 7B). The β-Gal activity was measured following the induction of nrc operon by adding nitrate and stopping the aeration. Figure 7B shows that the expression of β-Gal in both Δgfh and ΔgfhΔgreA strains is only slightly higher than in wt cells. However, the expression of β-Gal is reduced by three-fold in the ΔgreA strain relative to ΔgfhΔgreA. These results show that Gfh1 is indeed a transcriptional repressor in vivo, but that GreA suppresses its inhibitory activity. This implies that in vivo, the manifestation of the Gfh1 inhibitory function depends on the ratio of the GreA and Gfh1.

It should be noted that our experimental conditions do not allow us to assess the effect of pH on the in vivo inhibitory activity of Gfh1. Before induction, under normal growth conditions, the intracellular pH is maintained at 6.9–7.1 regardless of the pH of the media (in the range 6.2–7.5). Upon induction of the nrc operon, the intracellular pH drops to 6.5–6.7, apparently owing to lack of aeration. Therefore, the effect of Gfh1 deletion observed is similar for strains grown at pH 7.4 and 6.2 (Figure 7B).

Discussion

Functional activity of Gfh1 and the mechanism of action

Biochemical data obtained to date indicate that Gfh1 is a general transcription repressor that inhibits all catalytic activities of RNAP. RNAP requires for its activities the presence of two Mg2+ ions, Mg[I] and Mg[II] (Steitz and Steitz, 1993; Sosunova et al, 2003; Westover et al, 2004) in the active site. Mg[I] is tightly coordinated by three aspartates of the conserved catalytic loop NADFDGD of the β′-subunit of RNAP. Mg[II] is brought to the active center in the form of Mg2+–NTP complex, and is coordinated by the triphosphate moiety of NTP and two of the same catalytic loop aspartates. The results of our kinetic analyses (Figures 1, 2 and 3 and Supplementary Figures S1, S2 and S3) indicate that the inhibition by Gfh1 involves direct competition between Asp residues in the tip of the NTD loop with the NTP substrates (or pyrophosphates) for coordination of Mg[II] in the active center of RNAP. Apparently, the geometry of Gfh1–Mg2+ coordination is principally different from that of GreA or GreB. Gre factors catalyze nucleolytic reaction through simultaneous coordination of Mg[II] and the attacking nucleophile (either a water molecule or a hydroxide ion) in the active center. Unlike Gre, Gfh1 lacks any catalytic activity, and moreover, inhibits the intrinsic nucleolytic activity of RNAP. Thus, it appears that Gfh1 not only stabilizes Mg[II] in a nonproductive state but also blocks the proper positioning of the nucleophile by Mg[II]. This functional difference between Gfh1 and GreA may be attributable to the difference in local conformation of the NTD loop. Based on our mutagenesis studies, the amino-acid composition of the loop is not critical for Gfh1 function, provided that at least two acidic residues are present (see hybrid H3; Figure 2A). Therefore, we propose that the loop–proximal coiled-coil segment of NTD plays a critical role in stabilizing a specific conformation of the loop (see hybrid H5; Figure 2A).

In addition to direct competition with substrates, the inhibitory effect of Gfh1 also results from restricting the passage of substrates and abortive products to and from the active center by partial occlusion of the secondary channel, the main entryway for NTP substrates (Batada et al, 2004). This is supported by our observation that Gfh1-DA4 mutant, which cannot coordinate Mg2+ ion (Figure 3), nevertheless displays residual inhibitory activity (Figure 3). This property of Gfh1 resembles the action of the peptide antibiotic microcin J25, which inhibits transcription by binding within, and obstructing, the RNAP secondary channel (Adelman et al, 2004; Mukhopadhyay et al, 2004).

Although Gfh1 inhibits RNAP during both initiation and elongation stages of transcription, its inhibitory effect is more acute during abortive synthesis (Figure 1). We attribute this to the fact that Km for NTPs are generally higher during initiation than during elongation, and since Gfh1 increases the apparent Km for NTPs, the initiation complexes are intrinsically more susceptible to its inhibitory action. We predict that in vivo, promoters with initial transcribed sequences requiring high substrate concentrations may be targeted by Gfh1. However, elongation complexes stalled at Km-dependent pause sites may be also more sensitive to Gfh1.

Structure of Gfh1 and implications for its regulation

Our X-ray crystallographic analysis shows that the domain structures of Gfh1 and GreA are similar as predicted by their high sequence similarity (Supplementary Figure S2). Remarkably, however, the CTD in the structure of Gfh1 is rotated almost 180° around an axis (Figure 4) tilted roughly 45° from the axis of NTD. While this paper was in preparation, Symersky et al (2006) and Lamour et al (2006) reported the crystal structure of Tth Gfh1, also with the flipped conformation of its CTD. The reported lower resolution structures are overall very similar to ours, with minor differences in the conformation of NTD loop and the tilting angle of CTD, which could be attributed to different crystallization conditions. Symersky et al (2006) hypothesized that Gfh1 could bind and inhibit RNAP with the flipped conformation of its CTD. Our results clearly exclude such possibility and demonstrate that Gfh1 can act only when its CTD is in ‘GreA-like' conformation.

Gfh1 most likely exists in equilibrium between two conformations. One indication for this is that Gfh1 crosslinked in the ‘GreA-like' conformation displays higher inhibitory activity than wt Gfh1 even at pH 6.5 (Figure 6), implying that some fraction of wt Gfh1 is present in inactive conformation. In this regard, it should be noted that Gfh1 molecules trapped in crystal at pH 6.0 in the ‘flipped' conformation could be a minute fraction of the total protein. For this and other reasons, the ratio of ‘flipped' versus ‘GreA-like' conformers in solution cannot be inferred. How can pH affect the equilibrium between the two conformations of Gfh1? There are three hydrogen bonds in the interdomain interface of Gfh1 in the ‘flipped' conformation, two of which involve D136 and E148 whose ionization state is likely to affect the strength of the hydrogen bonds. It was previously shown that the pH-driven dimerization of T-cell adhesion protein CD2 domain hinges on the protonation of a single residue at the interface of the dimer, a glutamate with an anomalous pKa of 6.9 (Chen et al, 2002). By extension, the protonation of Gfh1 D136 and/or E148 within the pH range of 6.0–7.5 could also affect the interdomain hydrogen bond formation, and thus the conformation of CTD. The pKa-dependent conformational toggle could serve as a molecular switch that activates or inactivates Gfh1 inhibitory function. Thus, Gfh1 may play a role as a pH sensor in the cell.

Conformational switch could be a general regulatory mechanism for all Gre-related transcription factors. We constructed mutants of E. coli GreA analogous to Gfh1-CC12 and -CC13 and confirmed by SDS–PAGE analyses that both proteins can be crosslinked intramolecularly through their cysteines with high efficiency (data not shown), demonstrating that like Tth Gfh1, E. coli GreA alternates between two conformations in solution. Moreover, crosslinked GreA-CC mutants showed a similar correlation between conformation and activity as the Gfh1-CC mutants. That is, GreA is inactive as a transcript cleavage factor in the flipped conformation, and active in the ‘GreA-like' conformation. Thus, we may speculate that reversible conformational switch could provide a mechanism to modulate the concentration of active GreA molecules in the cell where GreA is known to be constitutively expressed. Unlike Gfh1, however, GreA activity does not appear to be pH-dependent, suggesting that its conformational switch could be induced by a different environmental factor.

While neither Gfh1 nor GreA is essential under normal growth conditions, they may be required for cell survival under specific stress conditions such as heat shock, starvation, and chemical or osmotic stress. Since the conformational change of Gfh1 is likely to occur fast, it may be involved in response to a sudden intracellular acidification, for instance, from respiratory failure owing to lack of oxygen.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

The wt and mutant Tth GreA and Gfh1 factors were cloned, expressed, and purified as described (Laptenko et al, 2003; see also Supplementary data). Tth RNAP core and holoenzyme were isolated from T. thermophilus HB-8 strain as described (Vassylyeva et al, 2002). All proteins were stored at −80°C in 50% (v/v) glycerol.

Crystallographic studies

Crystals of the Tth Gfh1 were grown by the hanging-drop method at 23°C with a well solution containing 26–29% PEG-3350 and 100 mM MES, pH 6.0. Crystals were soaked in mother liquor containing 15% glycerol and flash frozen in liquid propane. The crystals were found in the same crystallization drop in several different space groups, including P21 (a=28.41 Å, b=152.66 Å, c=32.37 Å, β=102.65°, and 2 molecules/a.s.u.) and P212121 (a=30.11 Å, b=82.21 Å, c=140.75 Å, 2 molecules/a.s.u.). The orthorhombic and monoclinic crystals diffracted to ∼2.5 Å and better than 1.5 Å resolution, respectively. X-ray diffraction data were collected at beamlines X4A, X25, and X6A at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) at Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL). We collected MAD data sets at the Se edge for both crystals in the P212121 and P21 space groups and solved the structures in these two space groups independently. The structures of Gfh1 in these two space groups are essentially the same, except the slightly shifted relative orientation of the two molecules in the a.s.u. The model of the P21 crystals was build using program ‘O' (Jones et al, 1991), and refined to 1.6 Å resolution using CNS (Brunger et al, 1998). The current model contains 292 water molecules and has the sequence amino-acid molecule of the 156-built, except for the first two residues.

Construction of mutant Tth GreA and Gfh1

Plasmids expressing Tth greA and gfh1 genes carrying N-terminal 6xHis-tag and heart muscle kinase recognition site (HMK) were constructed by PCR mutagenesis using appropriate primers and pET19b-GreA1 and pET19b-GreA2 (Laptenko et al, 2000, 2003) as templates, respectively, and cloned into NcoI/NdeI-linearized pET19b (Novagen). The resulting pET19b[NPH]GreA and pET19b[NPH]Gfh1 were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE-3)pLysS cells for overexpression. Residues for Cys substitution in GreA- and Gfh1-CC mutants were chosen based on the structural data and the program Disulfide By Design (Dombkowski, 2003). All mutant and hybrid greA and gfh1 were constructed using three-step PCR (Koulich et al, 1997), or Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). Primers used in all PCR-based cloning were obtained from IDT and their sequences are available upon request. The sequences of all resulting plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing (GeneWiz). The wt GreA and Gfh1 proteins were purified as described (Laptenko et al, 2000). The tagged proteins were purified by metal-affinity and size-exclusion chromatography, as described for E. coli GreA (Laptenko et al, 2003) and analyzed by SDS–12%-PAGE. Gfh1-CC and Gre-CC proteins were isolated under nonreducing conditions and additionally purified by ion-exchange FPLC using Mono-Q column (GE-Healthcare).

Isolation and characterization of ΔgreA and Δgfh1 Tth mutants

T. thermophilus HB27nar and its mutant strains were grown in TB medium (Ramirez-Arcos et al, 1998) adjusted to pH 7.4 or pH 6.2. For the isolation of greA and gfh1 mutants, derivatives from the suicidal pK18 plasmids (Cava et al, 2004b) carrying upstream and downstream 1 kbp DNA regions around each gene were constructed by conventional methods (Supplementary data). In Δgfh1 construct, the gfh1 promoter was kept to allow the expression of downstream genes, whereas in ΔgreA, the apparently monocistronic greA was deleted together with its promoter.

Cell size and morphology were studied by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy. Cells were covalently labeled with derivatives of either Texas Red or Oregon Green (Cava et al, 2004a). Intracellular pH was measured at 70°C on total extracts from mechanically broken cells after washing them three times with distilled water followed by centrifugation.

β-Gal reporter assays

T. thermophilus HB27 nrcN∷bgaA express a thermostable β-Gal from the Pnrc promoter when incubated in the presence of nitrate under anoxic conditions (Cava et al, 2004b). To analyze the effect of the GreA and Gfh1 on this promoter, the nrcN∷bgaA mutation was transferred to the wt and each mutant Tth strains by selecting for the bgaA-linked kanamycin-resistant marker. The mean values of β-Gal activities from two clones of each mutant in three different 4-h induction experiments were used (Cava et al, 2004b).

In vitro transcription assays

Transcription assays were performed using linear DNA fragments carrying either a standard T7A1 promoter with 50-nt transcript (T7A1-50) (Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003) or a modified promoter with 720-nt transcript (TML-720) made of 20 nt of initial transcribed sequence of T7A1 followed by 700 nt of E. coli lacZ gene. Additionally, we used 218- and 443-bp-long linear DNA templates carrying, respectively, Tth Pnrc (47-nt-long transcript) and Pnqo (90-nt-long transcript) promoters (Cava et al, 2004b). Unless otherwise indicated, all reactions were carried out at 60°C for indicated periods of time in standard transcription buffer adjusted to pH 6.5, 6.9, or 7.5 (50 mM MOPS; 60 mM KCl; 10 mM MgCl2; 0.2 mg/ml BSA) with or without 1 mM DTT. Reaction mixtures contained 25–100 nM DNA template, 25–150 nM RNAP holoenzyme, 0–5 μM transcription factors, and appropriate mixture of initiator ApU, NTPs, and [α-32P]-labeled radioactive NTPs (3000 Ci/mmol) (MP-Biomedicals). For multiround transcription, all reactions were supplemented with 50 μg/ml heparin. At this concentration, heparin promoted multiround RNA synthesis by Tth RNAP. All the reactions were terminated as described (Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003). RNA products were analyzed by urea–23% PAGE or urea–8% PAGE, autoradiographed, and quantified by PhosphorImager. All assays were reproduced several times and average data from three independent experiments are presented.

RNAP-binding assays

Direct and competitive Gfh1/GreA-RNAP-binding experiments were conducted as described (Laptenko and Borukhov, 2003) using size-exclusion HPLC on Superose 6, except 50 mM MOPS buffer was used instead of Tris–HCl and pH was adjusted to either pH 6.4 or 7.5. For each assay, 25 μl sample contained 2.5 μM [32P]Gfh1 (∼2000 c.p.m./μl), 5 μM RNAP core or 10 μM carrier protein thyroglobulin, 50 mM MOPS buffer, pH 6.4 or 7.5, 5% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Accession numbers

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the entry code 2F23.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Figure 4

Supplementary Figure 5

Supplementary Figure 6

Supplementary Figure 7

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ekaterina Stepanova for help with in vivo studies of Tth strains, and to the beamline staffs of NSLS for their support during X-ray data collections. We are also indebted to Dr Jordi Benach for his help with light-scattering measurements. This work has been supported by NIH Grants GM54098 to SB, GM70841 to XPK, and by the Spanish ‘Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia Grant BIO2004-02671 and Fundación Ramón Areces Institutional Grant to JB. SSK was supported by NIH training grant AI07180.

References

- Adelman K, Yuzenkova J, La Porta A, Zenkin N, Lee J, Lis JT, Borukhov S, Wang MD, Severinov K (2004) Molecular mechanism of transcription inhibition by peptide antibiotic Microcin J25. Mol Cell 14: 753–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batada NN, Westover KD, Bushnell DA, Levitt M, Kornberg RD (2004) Diffusion of nucleoside triphosphates and role of the entry site to the RNA polymerase II active center. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17361–17364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borukhov S, Lee J, Laptenko O (2005) Bacterial transcription elongation factors: new insights into molecular mechanism of action. Mol Microbiol 55: 1315–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D 54: 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cava F, de Pedro MA, Schwarz H, Henne A, Berenguer J (2004a) Binding to pyruvylated compounds as an ancestral mechanism to anchor the outer envelope in primitive bacteria. Mol Microbiol 52: 677–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cava F, Zafra O, Magalon A, Blasco F, Berenguer J (2004b) A new type of NADH dehydrogenase specific for nitrate respiration in the extreme thermophile Thermus thermophilus. J Biol Chem 279: 45369–45378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HA, Pfuhl M, Driscoll PC (2002) The pH dependence of CD2 domain 1 self-association and 15N chemical exchange broadening is correlated with the anomalous pKa of Glu41. Biochemistry 41: 14680–14688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Grado M, Castan P, Berenguer J (1999) A high-transformation-efficiency cloning vector for Thermus thermophilus. Plasmid 42: 241–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombkowski AA (2003) Disulfide by Design: a computational method for the rational design of disulfide bonds in proteins. Bioinformatics 19: 1852–1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish RN, Kane CM (2002) Promoting elongation with transcript cleavage stimulatory factors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1577: 287–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greive SJ, von Hippel PH (2005) Thinking quantitatively about transcriptional regulation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BP, Hartsch T, Erie DA (2002) Transcript cleavage by Thermus thermophilus RNA polymerase. Effects of GreA and anti-GreA factors. J Biol Chem 277: 967–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M (1991) Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A 47: 110–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenberger H, Armache KJ, Cramer P (2003) Architecture of the RNA polymerase II–TFIIS complex and implications for mRNA cleavage. Cell 114: 347–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettenberger H, Armache KJ, Cramer P (2004) Complete RNA polymerase II elongation complex structure and its interactions with NTP and TFIIS. Mol Cell 16: 955–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulich D, Orlova M, Malhotra A, Sali A, Darst SA, Borukhov S (1997) Domain organization of Escherichia coli transcript cleavage factors GreA and GreB. J Biol Chem 272: 7201–7210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamour V, Hogan BP, Erie DA, Darst SA (2006) Crystal structure of Thermus aquaticus Gfh1, a Gre-factor paralog that inhibits rather than stimulates transcript cleavage. J Mol Biol 356: 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laptenko O, Borukhov S (2003) Biochemical assays of Gre factors of Thermus thermophilus. Methods Enzymol 371: 219–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laptenko O, Hartsch T, Bozhkov AI, Borukhov S (2000) Gre-homologous transcription factors GreA-1 and GreA-2 from Thermus thermophilus: cloning, purification and analysis of functional activity. Biologicheskiy Vestnik (Biol Herald) 4: 3–14 [Google Scholar]

- Laptenko O, Lee J, Lomakin I, Borukhov S (2003) Transcript cleavage factors GreA and GreB act as transient catalytic components of RNA polymerase. EMBO J 22: 6322–6334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay J, Sineva E, Knight J, Levy RM, Ebright RH (2004) Antibacterial peptide microcin J25 inhibits transcription by binding within and obstructing the RNA polymerase secondary channel. Mol Cell 14: 739–751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickels BE, Hochschild A (2004) Regulation of RNA polymerase through the secondary channel. Cell 118: 281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opalka N, Chlenov M, Chacon P, Rice WJ, Wriggers W, Darst SA (2003) Structure and function of the transcription elongation factor GreB bound to bacterial RNA polymerase. Cell 114: 335–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul BJ, Barker MM, Ross W, Schneider DA, Webb C, Foster JW, Gourse RL (2004) DksA: a critical component of the transcription initiation machinery that potentiates the regulation of rRNA promoters by ppGpp and the initiating NTP. Cell 118: 311–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perederina A, Svetlov V, Vassylyeva MN, Tahirov TH, Yokoyama S, Artsimovitch I, Vassylyev DG (2004) Regulation through the secondary channel – structural framework for ppGpp-DksA synergism during transcription. Cell 118: 297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Arcos S, Fernandez-Herrero LA, Berenguer J (1998) A thermophilic nitrate reductase is responsible for the strain specific anaerobic growth of Thermus thermophilus HB8. Biochim Biophys Acta 1396: 215–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T, Kopp T, Guex N, Peitsch MC (2003) SWISS-MODEL: an automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 3381–3385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosunova E, Sosunov V, Kozlov M, Nikiforov V, Goldfarb A, Mustaev A (2003) Donation of catalytic residues to RNA polymerase active center by transcription factor Gre. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15469–15474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins CE, Borukhov S, Orlova M, Polyakov A, Goldfarb A, Darst SA (1995) Crystal structure of the GreA transcript cleavage factor from Escherichia coli. Nature 373: 636–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz TA, Steitz JA (1993) A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 6498–6502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symersky J, Perederina A, Vassylyeva MN, Svetlov V, Artsimovitch I, Vassylyev DG (2006) Regulation through the RNA polymerase secondary channel: structural and functional variability of the coiled-coil transcription factors. J Biol Chem 281: 1309–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassylyeva MN, Lee J, Sekine SI, Laptenko O, Kuramitsu S, Shibata T, Inoue Y, Borukhov S, Vassylyev DG, Yokoyama S (2002) Purification, crystallization and initial crystallographic analysis of RNA polymerase holoenzyme from Thermus thermophilus. Acta Crystallogr D 58: 1497–1500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westover KD, Bushnell DA, Kornberg RD (2004) Structural basis of transcription: nucleotide selection by rotation in the RNA polymerase II active center. Cell 119: 481–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Figure 1

Supplementary Figure 2

Supplementary Figure 3

Supplementary Figure 4

Supplementary Figure 5

Supplementary Figure 6

Supplementary Figure 7