Abstract

Objectives: As part of a project to map the literature of nursing, sponsored by the Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section of the Medical Library Association, this study identifies core journals cited by general or “popular” US nursing journals and the indexing services that cover the cited journals.

Methods: Three journals were selected for analysis: American Journal of Nursing, Nursing 96–98, and RN. The source journals were subjected to a citation analysis of articles from 1996 to 1998, followed by an analysis of database access to the most frequently cited journal titles.

Results: Cited formats included journals (63.7%), books (26.6%), government documents (3.0%), Internet (0.5%), and miscellaneous (6.2%). Cited references were relatively current; most (86.6%) were published in the current decade. One-third of the citations were found in a core of 24 journal titles; one-third were dispersed among a middle zone of 94 titles; and the remaining third were scattered in a larger zone of 694 titles. Indexing coverage for the core titles was most comprehensive in PubMed/MEDLINE, followed by CINAHL and Science Citation Index.

Conclusions: Results support the popular (not scholarly) nature of these titles. While not a good source for original research, they fulfill a key role of disseminating nursing knowledge with their relevantly current citations to a broad variety of sources.

INTRODUCTION

The primary purpose of this study was to analyze the core literature cited in “general” United States nursing journals: American Journal of Nursing (AJN), Nursing,* and RN. The study also analyzed database access to the top-cited journals from these source journals. This was a Phase I study of the Task Force on Mapping the Literature of Nursing, sponsored by the Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section (NAHRS) of the Medical Library Association. The study used the common methodology described in the overview article, subjecting the three source journals to citation analysis over a three-year period, 1996 to 1998, and ranking the number of cited references by journal title in descending order to identify the most frequently cited titles according to Bradford's Law of Scattering [1]. From this core of most productive journal titles, coverage in bibliographic databases was analyzed to determine which databases provided the best access. The purpose of this analysis was to assist librarians with journal and database selection, provide end users of the literature with guidelines for selecting databases to search, and recommend additional titles to database producers.

In an editorial based on a 1995 presentation to the International Academy of Nurse Editors (INANE), Smith divided nursing journals into three types: “popular,” specialist, and scholarly [2]. He stated that “The popular nursing journals aim to keep their readers regularly informed about up-to-date and topical professional developments, trends in nursing care and practice, news about individuals and the profession, and by providing conference reports” [2]. These journals are seen as complementary to the specialist and scholarly literature. They are important in that they fill a key role of translating research information to formats that are more accessible to nurses in clinical practice. This study uses the term “general” to describe the popular clinically oriented journals marketed to practicing nurses.

SOURCE JOURNALS

In the United States, the 3 monthly titles chosen for this study had the highest circulation among nursing journals for both libraries and individuals. In 2003, they headed the list of the top 50 nursing titles ordered from EBSCO Subscription Services [3]. In a study of registered nurses' (RN's) journal reading habits, Skinner and Miller noted 1987 circulation figures of 511,600 for Nursing, 330,428 for AJN, and 275,000 for RN [4]. In their study, those titles were the ones most frequently read by staff nurses at 2 hospitals, with 2/ 3 of respondents subscribing to at least 1 nursing journal. These titles also headed the list of professional journals read by educators in a 1970s survey sent to a sample of staff development educators at 141 California hospitals [5]. In addition, all 3 titles appeared on the Brandon/Hill nursing list [6] and appeared in Table 4: “Coverage of Most Frequently Cited Journals” in the overview article summarizing the analyses of all the mapping studies [1]. While print circulation has declined, current numbers reported to Ulrich's remain high [7]. Nursing is still in first place, with a reported circulation of 300,424. RN reports 237,615, and AJN reports just 144,000 paid. AJN is also sent to all members of ANA, which makes it the world's largest circulating nursing journal [8].

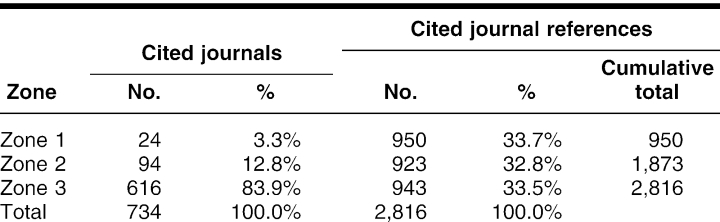

Table 4 Distribution by zone of cited journals and references

At the end of the nineteenth century, American nurses identified the need for a journal “for nurses and about nurses” [9]. With the first issue published in October 1900, AJN was established as the official journal of the Associated Alumnae of Trained Nurses of the United States, which became the American Nurses' Association (ANA) [10]. Lippincott was the publisher until 1913, when AJN was acquired by ANA. In 1996, the journal was reacquired by Lippincott Williams and Wilkins and continued as the official journal of ANA [11]. The history of this journal was well documented in anniversary issues, including the centennial issue published in October 2000. Wheeler credited AJN with contributing to the socialization of the profession [12]. Wheeler's study explored the editorial position and content of each issue in the first twenty years of AJN in relation to the emergence of nursing as a profession. Results revealed strong nursing leadership that supported legitimizing nursing as a self-controlled profession and generating reform in nursing and society at large.

While edited by nurses, the other two journals were more commercial in nature. RN, published by Medical Economics, began in October 1937, and Nursing started in November 1971. Nursing was published by Springhouse Corporation until 2001, when Springhouse was purchased by Lippincott. These titles focused on clinical topics and were known for their use of illustrations and color. In the late 1990s, each surveyed their readership and made changes related to trends in nursing and health care. Noting that readers had little time to read, the editor of RN announced design changes intended to make key information easier to identify [13]. Nursing added the tagline “the voice and vision of modern nursing” and noted that hospital practice no longer defined nursing practice [14]. This editorial announced a “core curriculum” of topics common to all settings and promised articles on therapies and procedures as well as professional trends.

With their high circulation, these journals are well positioned to convey current research findings to practicing nurses, thereby helping to improve the translation of research into practice. As part of this goal, all three publish continuing education (CE) articles in each issue. AJN and Nursing provide free access to these CE articles via the Web, and RN Web offers online access to all content to subscribers. RN began offering CE credit in 1986, with the editor noting a commitment to “offer our readers more opportunities to earn continuing education credit than any of our competitors” [15]. CINAHL database indexing noted the presence of CE units for journal articles in 1985, with seventeen indexed for AJN and twenty-two for Nursing. Given the competition between these titles, the current study notes the number of CE articles in these titles for the studied years as part of the analysis of these source journals.

Other general US nursing journals are not national in scope, with Nursing Spectrum and Nurse Week as a primary examples. These journals are published in several regional editions with slightly different content. General American nursing periodicals have a different “flavor” than those in other countries. For example, Canadian Nurse was published in bilingual editions (English and French) until 2001, when the Canadian Nurses Association decided to publish separate editions. Nursing Times and Nursing Standard are both published weekly in the United Kingdom.

METHODS

The common methodology is described in detail in the overview article and project protocol for the NAHRS “Mapping the Literature of Nursing Project” [1, 16].

RESULTS

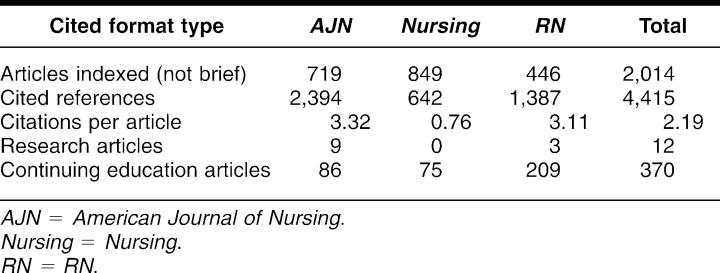

For the years studied (1996–1998), Nursing published the most articles, with fewer references than either AJN or RN. Table 1 is based on CINAHL indexing for these titles. The average number of cited references for AJN was slightly more than for RN. While none of the source journals were “scholarly,” Nursing was the least scholarly of the 3 journals. As promised by its editors, RN published considerably more articles with CE credit than either AJN or Nursing. This trend continued: RN published 242 CE articles from 2001 to 2003, compared to 131 for AJN and 81 for Nursing [17]. AJN increased its production of CE articles more than Nursing did. None of the titles features research on a regular basis, and only AJN and RN accounted for the handful of research articles published during the studied years. All 3 claimed peer-review status but did not respond to a CINAHL survey of nursing and allied health journal editors requesting information on the specific type of peer review (i.e., blind, double-blind, editorial board, or expert) [17]. The data in this study support the popular, not scholarly, nature of these titles.

Table 1 Source journal characteristics

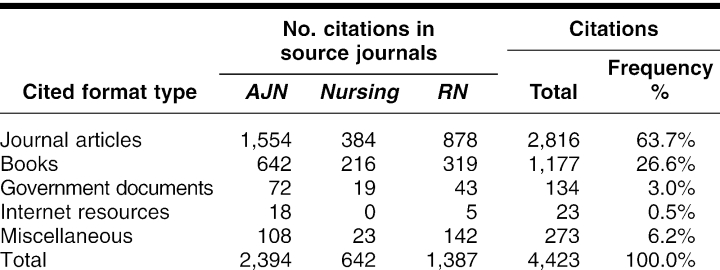

Cited formats

Journals accounted for the majority of the cited references, as shown in Table 2. Books accounted for more than a quarter of the citations. Sixty-seven citations were to drug references, mostly books, including thirteen to the Physician's Desk Reference (PDR). Other reference books were also cited, including eight citations to the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) and eighteen citations to manuals of diagnostic tests. Publications from organizations were highly cited in the books and miscellaneous categories, including twenty-four to ANA publications, including the ANA code and position statements; thirteen to Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) standards; twelve to American Heart Association cardiac-life-support publications; and eighty-four to a variety of other association publications.

Table 2 Cited format types by source journal and frequency of citations

While government documents accounted for just 3% of the citations, 52 were citations to government guidelines. Professional organizations' guidelines were also cited. While citations to the Internet were minimal, evidence indicated that the journals were using Internet resources for information, including 7 statistical references. Thirty-eight statistical references came from the non-journal categories. “Miscellaneous” included a variety of publications not easily categorized, including 50 legal cases and 24 newspaper articles. Citation of news items, position statements, guidelines, statistical resources, and the legal literature suggests that these journals are fulfilling their mission of keeping nurses informed on current professional issues.

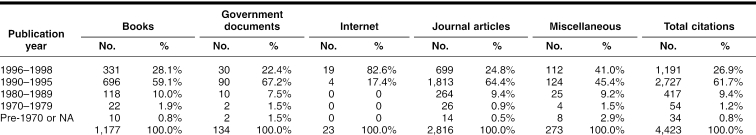

Age of cited references

The ages of cited references were remarkably current. As indicated in Table 3, almost 27% of the cited references were very current, coming from the same years as the source journals, 1996 to date. A total of 88.6% came from the 1990s, with just 9.4% from the 1980s and fewer than 2% published prior to 1980.

Table 3 Cited format types by publication year periods

Cited journals and database indexing

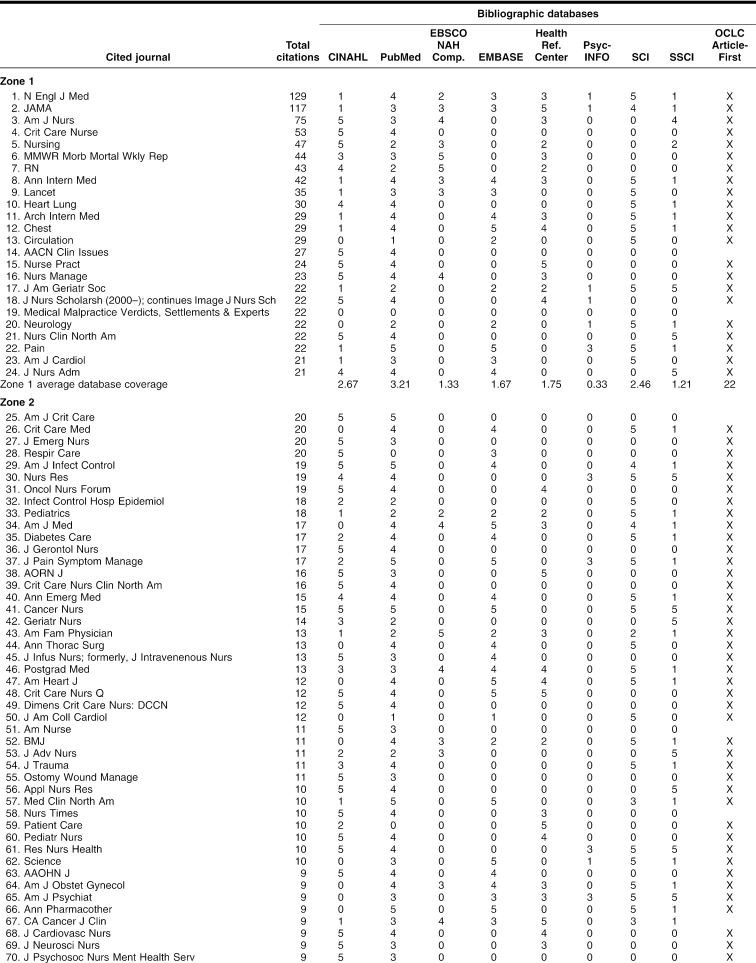

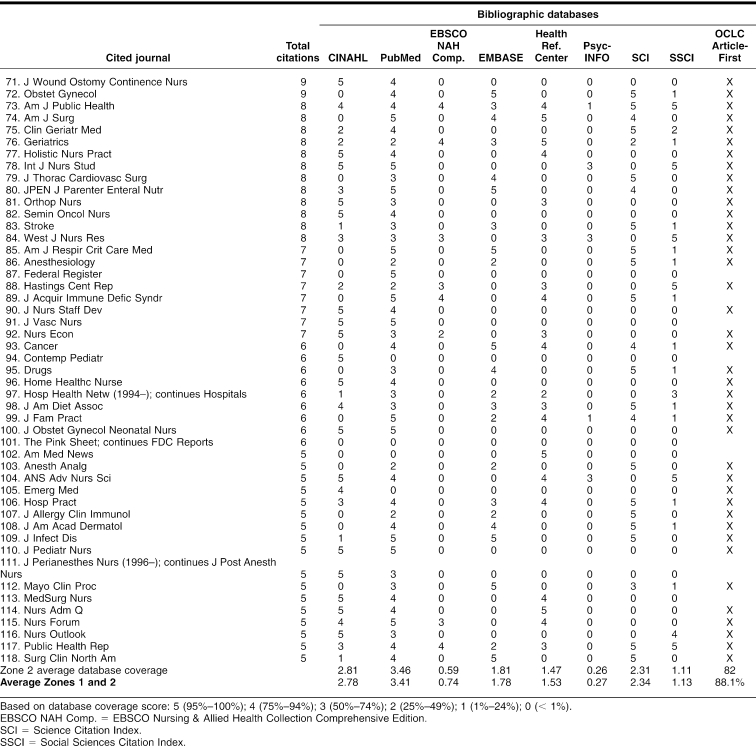

The cited journals were listed in order of descending frequency and divided into three zones, per the project protocol, as shown in Table 4. A relatively small number of journals accounted for the titles in the top 2 zones. The combined total, 114, represented just 16.1% of the cited titles, confirming Bradford's Law of Scattering. Table 5 presents the distribution and indexing of cited journals in Zones 1 and 2. Titles in Zone 3 are not displayed but are available from the author by request. The cited journals included broad representation from nursing, biomedicine, and the social sciences. All 3 source journals appeared in Zone 1, with AJN the most frequently cited nursing journal, followed by Critical Care Nurse, Nursing, RN, and Heart & Lung in the top ten.

Table 5 Distribution and database coverage of cited journals in Zones 1 and 2

Five of the searched databases—EBSCO Health Business, EBSCO Health Source Plus, ERIC, PsycINFO, and Sociofile—did not provide significant coverage for the cited journals in Zones 1 and 2. Table 5 indicates the average coverage scores for the indexing services, omitting OCLC ArticleFirst, which had unreliable numbers for indexed articles. PubMed/MEDLINE provided the best overall coverage of the top cited journals because many were biomedical, followed by CINAHL and Science Citation Index. No other databases had an average score above 2. Note that the 3 source journals were indexed in the 2 resources with full-text holdings (EBSCO Nursing & Allied Health Collection Comprehensive Edition and Health Reference Center), but full-text was only included for RN in the EBSCO database, demonstrating how inclusion of full-text changes indexing coverage scores. Of the 3 source journals, only RN did not score 5 in CINAHL. OCLC ArticleFirst covered 88.1% of the titles, confirming its potential value as a current information resource for nursing. Nursing journals appeared to have the best coverage in CINAHL, and PubMed/MEDLINE offered the best coverage for biomedical titles.

DISCUSSION

The general US nursing journals cite both nursing and biomedical literature. As noted, cited sources are remarkably current. These journals provide nurses with current information from a wide variety of sources, helping to meet the goal of keeping busy nurses informed on current issues and clinical knowledge. They are a good source for continuing education credit and can be recommended to libraries and individual nurses. These titles are highly cited in the other mapping studies, with all appearing in Table 4 of the overview article (115 titles) [1] and would be considered essential for all libraries serving nursing.

CONCLUSIONS

AJN, Nursing, and RN fill an important niche in the literature of nursing. Their most outstanding features include currency and a commitment to presenting information in formats that practicing nurses would find useful. While not “scholarly,” they do cite a wide variety of sources. Future study is needed to determine how the Internet is impacting this type of publication. Will citations to the Internet increase? Will the provision of CE articles via the public Internet continue as a profitable enterprise for publishers? Will newer publications, including those with free distribution (Nursing Spectrum and Nurse Week) capture the individual subscription market? Citation analysis tells just part of the story. Other types of research are needed to answer some of these questions, including readership studies updating those studies published in the 1980s [4, 18].

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the NAHRS task force members who volunteered to check databases: Kristine Alpi, AHIP, Melody Allison, Carol Galganski, AHIP, and Martha (Molly) Harris, AHIP. Thanks to Susan Jacobs, AHIP, Dorice Vieira, and Jennifer Schwartz at New York University for designing the Access database used to analyze the non-journal citations. Last but not least, Ginny Chaskey and Cinahl Information Systems supplied cited journal references as spreadsheets and produced lists of non-journal cited references for each of the three source journals.

Footnotes

* Nursing (ISBN: 0360-4039) uses the year of publication as part of its official title. In this article, the year is omitted when referring to this journal.

Contributor Information

Margaret (Peg) Allen, Email: pegallen@verizon.net.

June R. Levy, Email: jlevy@cinahl.com.

REFERENCES

- Allen M, Jacobs SK, and Levy JR. Mapping the literature of nursing: 1996–2000. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Apr; 94(2):206–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP. The value of nursing journals. J Adv Nurs. 1996 Jul; 24(1):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EBSCO listing: online and print journals in nursing 2003. Birmingham, AL: EBSCO, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner K, Miller B. Journal reading habits of registered nurses. J Contin Educ Nurs. 1989 Jul–Aug; 20(4):170–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binger JL, Huntsman AJ. Keeping up: the staff development educator and the professional literature. Nurse Educ. 1979 May–Jun; 4(3):19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill DR, Stickell HN. Brandon/Hill selected list of print nursing books and journals. Nurs Outlook. 2002 May–Jun; 50(3):100–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich's periodicals directory. [Web document]. R. R. Bowker, 2005. [cited 29 Jul 2005]. <http://www.ulrichsweb.com>. [Google Scholar]

- American Journal of Nursing. [Web document]. New York, NY: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2005. [cited 1 Aug 2005]. <http://www.ajnonline.com>. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MM. The journal's golden anniversary. Am J Nurs. 1950 Oct; 50(10):583–5. [Google Scholar]

- DeWitt K. The journal's first fifty years. Am J Nurs. 1950 Oct; 50(10):590–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott J. An enduring partnership. Am J Nurs. 2000 Oct; 100(10):11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler CE. The American Journal of Nursing and the socialization of a profession, 1900–1920. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1985 Jan; 7(2 Suppl):20–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattera MD. Welcome…. RN. 1999 Jan; 62(1):7. [Google Scholar]

- Nornhold P. A new voice and vision. Nursing. 1997 Jan; 27(1):10. 9171641 [Google Scholar]

- Mattera MD. A new name. RN. 1997 Jan; 60(1):7. [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, Jacobs SK, and Vieira D. Mapping the literature of nursing project protocol. [Web document]. Kent, OH: Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section Task Force on Mapping the Literature of Nursing, Medical Library Association, 2003. [cited 25 May 2005]. <http://nahrs.library.kent.edu/activity/mapping/nursing/protocol.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. Key and electronic nursing journals: characteristics and database coverage. 2005 ed. Glendale, CA: Cinahl Information Systems, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz D. An investigation of the usage of the periodical literature of nursing by staff nurses and nursing administrators. J Cont Educ Nurs. 1986 Jan–Feb; 17(1):22–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]