Abstract

Objectives: As part of a project to map the literature of nursing, sponsored by the Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section of the Medical Library Association, this study identifies core journals cited in nursing education journals and the indexing services that cover the cited journals.

Methods: Three nursing education source journals were subjected to a citation analysis of articles from 1997 to 1999, followed by an analysis of database access to the most frequently cited journal titles.

Results: Cited formats included journals (62.4%), books (31.3%), government documents (1.4%), Internet (0.3%), and miscellaneous (4.6%). Cited references were relatively older than other studies, with just 58.6% published in the 1990s. One-third of the citations were found in a core of just 6 journal titles; one-third were dispersed among a middle zone of 53 titles; the remaining third were scattered in a larger zone of 762 titles. Indexing coverage for the core titles was most comprehensive in CINAHL, followed by PubMed/MEDLINE and Social Sciences Citation Index.

Conclusions: Citation patterns in nursing education show more reliance on nursing and education literature than biomedicine. Literature searches need to include CINAHL and PubMed/MEDLINE, as well as education and social sciences databases. Likewise, library collections need to include education and social sciences resources to complement works developed for nurse educators.

INTRODUCTION

The primary purpose of this study was to analyze the core literature cited in nursing education journals. The study also analyzed database access to the most cited journals from these source journals. This was a Phase II study of the Task Force on Mapping the Nursing Literature, sponsored by the Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section (NAHRS) of the Medical Library Association. The study used the common methodology described in the overview article [1], subjecting the three source journals to citation analysis over a three-year period, 1997 to 1999, and ranking the number of cited references by journal title in descending order to identify the most frequently cited titles according to Bradford's Law of Scattering [2]. From this core of most productive journal titles, coverage in bibliographic databases was analyzed to determine which databases provided the best access. The purpose of this analysis was to assist librarians with journal and database selection, provide nurse educators with guidelines for selecting databases to search, and recommend additional titles to database producers.

Nursing education includes “generic” education— initial preparation for nursing—as well as graduate programs and lifelong learning via formal continuing education and staff development roles. Teaching is also considered a significant role for all nurses, along with management and clinical practice. However, for the purposes of this study, nursing education refers to the education of nurses, not patient education.

HISTORY

The history of nursing education is tied to nursing's quest for a professional identity. As noted by Smith, early hospital-based nursing schools “were little more than protected environments in which young women carried the major burden of nursing patients. Often they taught younger students as well” [3]. Mary Nutting, one of the early leaders for reforming nursing education, was credited as the first nurse to conduct research on the educational status of nursing in 1906 [4]. Several reports, most notably Goldmark (1923) and Brown (1948), recommended that nursing education take place in institutions of higher learning [3–5]. In 1966, the American Nurses Association House of Delegates adopted the famous 1965 position paper on entry into practice [3, 6]. Smith summarized the position paper:

The major components of the position paper are as follows: education for all who practice nursing should take place in institutions of higher education; the minimum preparation for beginning professional nursing practice should be a baccalaureate degree in nursing; and the minimum preparation for technical nursing practice should be an associate degree education in nursing. [3, 6]

An excellent summary of the ongoing issues regarding the “entry into practice” issue was published in the Online Journal of Issues in Nursing [7]. While nursing is still trying to achieve the goal of a bachelor's degree in nursing for all professional nurses, most nursing education in the United States and other countries now takes place in educational institutions, although some hospital-based diploma programs remain. This move to academia placed new demands on faculty, especially those in baccalaureate programs. To meet accreditation requirements, faculty were expected to obtain a master's degree as a minimum and a doctoral degree for tenure. The process of obtaining graduate degrees and maintaining scholarly productivity helped foster the development of nursing research and the publication of more nursing journals, including titles devoted to nursing education.

In addition to creating more baccalaureate nursing programs, educational reform also pushed diploma programs to become more pedagogically sound. All types of programs encouraged faculty to research educational topics, including studies of educational outcomes related to curriculum reforms. In a history of Nursing Research, the 1st nursing journal devoted to research, Baer noted that educational research dominated the early issues and that it would be 1976 before the editor could state that more than 50% of the articles reported clinical nursing research [8]. A 1984 analysis classified nursing research into four categories: nursing education, nurse characteristics, administration, and clinical practice [9]. Topics for nursing education research included “investigations of student and teacher attitudes, backgrounds, and relationships, and studies of curricula, teaching methods, continuing education, and staff development.” Looking at numbers of studies published in key research journals in 1952 to 1953, 1960, 1970, and 1980, this study noted a relative decline in publication of research devoted to nursing education, from 50% in the 1952-to-1953 sample to 21% in 1980. However, this article also noted the development of specialty journals, including the Journal of Nursing Education, which published 19 nursing education research articles in 1980.

NURSING EDUCATION TODAY

As documented in these early studies, nursing is serious about education, placing major emphasis on lifelong learning as well as initial preparation. Continuing nursing education is organized by professional associations, as well as hospitals and others employing nurses. Specialty certification includes expectations of continuing education, and many jurisdictions require continuing education for licensure renewal. This is just as true for nursing faculty and educators as it is for clinicians. In 2001, the National League for Nursing (NLN) adopted a position statement noting the importance of lifelong learning for faculty, with an emphasis on learning about education as well as clinical topics [10]. In 2005, NLN announced a pilot certification program for nurse educators, including the development of eight core competencies [11].

Each country has organizations that support nursing education and accredit nursing programs. NLN is the oldest in the United States, created in 1893 as the American Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses [11], and Nursing Education Perspectives, formerly published under a variety of earlier titles, is its official journal. In earlier years, NLN had a broader mission, including public health nursing. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), founded in 1969, is dedicated to furthering baccalaureate and graduate nursing education [12], and its official journal is the Journal of Professional Nursing. In the United States, the accreditation function belongs to separate organizations created by NLN and AACN: the National League for Nursing Accrediting Commission (NLNAC), created in 1997, and the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE), created in 1996. In Canada, the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing/Association canadienne des écoles de sciences infirmières (CASN/ACESI) serves as the national organization for nursing education and research and accredits nursing programs [13]. Similar organizations exist in other countries, each working to advance education for nursing as well as the profession of nursing

METHODS

The common methodology is described in detail in the overview article [1]. Articles related to nursing education are published in nursing research journals and journals focused on nursing issues, as well as education-specific titles. The official journals of NLN and AACN, Journal of Professional Nursing and Nursing Education Perspectives, cover nursing and health care issues as well as education. The titles selected for this study focus exclusively on education topics and are published in the United States. Stevens, the initial researcher for this study, selected these titles based on informally surveying her nursing faculty and consulting the Brandon/Hill list [14]. The selected source journals include:

Journal of Nursing Education, published 1962 to date by Charles B. Slack

Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, published 1970 to date by Charles B. Slack

Nurse Educator, published 1976 to date by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

The Journal of Nursing Education “publishes research and other scholarly works involving and influencing nursing education…. [it] focuses on aspects of nursing education related to undergraduate and graduate programs in schools of nursing” [15]. In contrast, the mission of the Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing: Continuing Competence for the Future, from the same publisher, “is to support continued career competence through continuing education, staff development, professional policy, and advocacy” [16]. Nurse Educator focuses on both audiences, claiming “Nursing faculty members as well as in-service educators turn to this respected resource for developments and innovations in nursing education” [17].

RESULTS

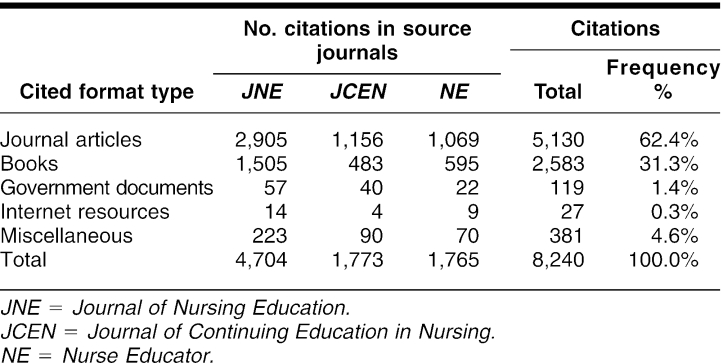

A total of 8,240 citations appeared in the 3 source journals during 1997 to 1999. Table 1 shows the distribution of the citations in the source journals among format types: journal articles (62.4%), books (31.3%), government documents (1.4%), the Internet (0.3%), and miscellaneous (4.6%).

Table 1 Cited format types by source journal and frequency of citations

Age of cited references

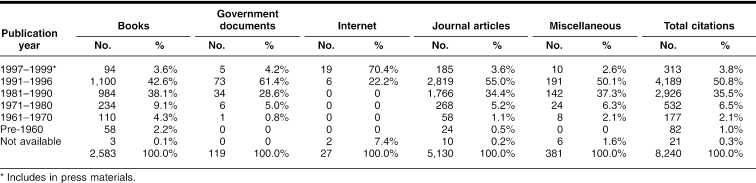

Table 2 breaks down the total citations for each format type into publication year ranges to see how recently the source journal citations were published, the most current being the study years 1997 to 1999. For all cited format types, except the Internet, the greatest number of citations were published during the years 1991 to 1996: journal articles (55.0%), books (42.6%), government documents (61.4%), and miscellaneous formats (50.1%). The second greatest publication year range for these formats was 1981 to 1990 for journal articles (34.4%), books (38.1%), government documents (28.6%), and miscellaneous (37.3%). The majority of Internet citations (70.4%) were published during 1997 to 1999, the most current time period for the study.

Table 2 Cited format types by publication year periods

Distribution of cited journals

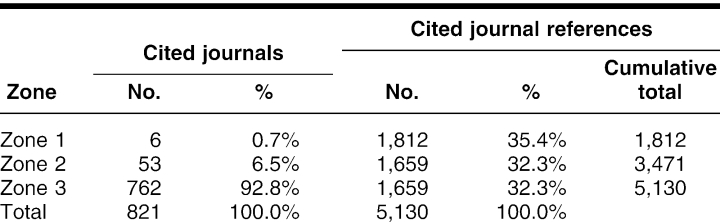

The 5,130 cited journal references came from a total of 821 journal titles, as indicated in Table 3. A ranked listing of the cited journal titles was created, based on the cumulated number of times each title was cited. Dividing this list into thirds created Zones 1, 2, and 3: Zone 1 had 6 (0.7%) of the cited journal titles; Zone 2 had 53 (6.5%) of the cited journal titles; and Zone 3 had 762 (92.8%) of the cited journal titles.

Table 3 Distribution by zone of cited journals and references

Distribution and database access for titles in Zones 1 and 2

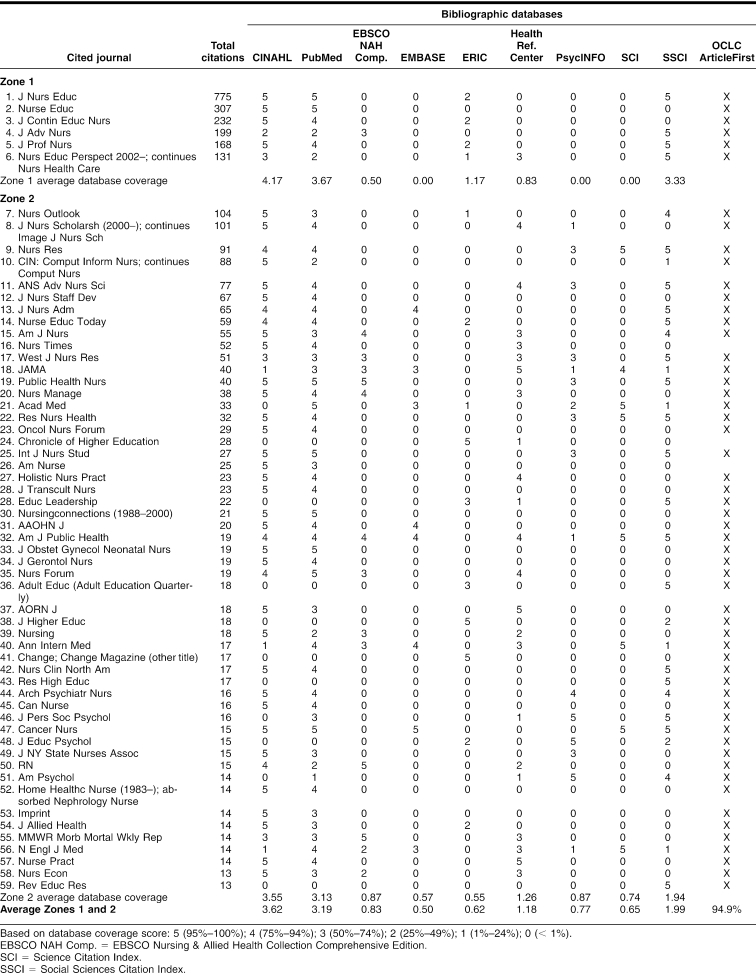

Table 4 compares database coverage for cited journals in Zones 1 and 2. For Zone 1, CINAHL (4.17) provided the best database indexing coverage, followed closely by PubMed/MEDLINE (3.67), then Social Sciences Citation Index (3.33), ERIC (1.17), Gale Health Reference Center (0.83), and EBSCO Nursing & Allied Health Collection Comprehensive Edition (0.50). EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Science Citation Index provided no coverage for any of the cited journal titles in Zone 1. CINAHL (3.55) provided the best indexing coverage in Zone 2, followed by PubMed/MEDLINE (3.13), Social Sciences Citation Index (1.94), Gale Health Reference Center (1.26), EBSCO Nursing & Allied Health Collection Comprehensive Edition and PsycINFO (0.87), Science Citation Index (0.74), EMBASE (0.57), and ERIC (0.55). The same relative ranking applied to the average coverage for the top two zones, with CINAHL, PubMed/MEDLINE, and Social Sciences Citation Index in the top three places.

Table 4 Distribution and database coverage of cited journals in Zones 1 and 2

While not scored, OCLC ArticleFirst covered 100.0% of the titles in Zone 1 and 94.9% of the combined total of 59 titles in the top 2 zones. Although Wilson Education Index was not part of the suite of databases analyzed for the mapping project's master coverage title list, coverage for all journals from Zones 1 and 2 was assessed. Only one title was covered better, Chronicle of Higher Education. Apparently, Wilson's coverage policies for this title were much broader than the other databases.

DISCUSSION

This study looked at the format types of cited references in source journal articles to get a sense of what types research articles depended on. Use of format types in journal article references for nursing education differed somewhat from most of the other specialties studied in the NAHRS “Mapping the Literature of Nursing Project” [1]. Although the majority of cited references in all specialties were from journals, nursing education cited journals to a lesser extent than the other specialties. The next most frequently used format for all specialties but one was books; nursing education had the highest proportion compared to the other specialties. This high proportion might be because nursing education research draws from fields that use books more than is typical in the biomedical sciences. The Web was not widely used during the years of this study, so the numbers reflected for this format were low compared to what they must be now. Only one other specialty made lower use of government documents in their journal articles, perhaps reflecting the limited government support for nursing education in the 1990s.

Publication year periods were examined to note the currency of the literature cited for research. The majority of citations were from literature published from three to eight years prior to the study. Nursing education was next to last of the specialties in the percentage of cited literature from the most recent two years, which made sense because a large proportion of literature used for research was books. Books take longer to be published and therefore have a larger gap between when a piece is actually completed and the date when it is accessible for use. Only one other specialty cited a higher percentage of references published more than twenty years before. Nursing education appears to build on theory and research of previous years, demonstrating a healthy respect for prior scholarly work.

Nursing education has a much lower percentage of Zone 1 cited journal titles than the other nursing specialties. This low percentage demonstrates that a very small number of journals, albeit all primary journals for nursing education, are the most productive for this specialty. Compared to other specialties, this area's Zone 1 titles are directly related to the specialty area, whereas the Zone 1 titles for other areas typically are from several areas, reflecting dependence on multidisciplinary sources of information. Zone 2 has a considerably smaller percentage of journal titles than any of the other areas, again revealing reliance on a smaller number of journals for even moderately productive titles. This demonstrates a core number of journals that nursing educators utilize for research. Also notable, but not surprising compared to results from the other specialties, Zone 1 totally consists of nursing journals and Zone 2 has a high percentage of nursing journals (32.1%), showing less dependence on the literature of medicine and other disciplines.

Average database coverage scores for the specialty of nursing education show that CINAHL provides the best coverage of journals, followed by PubMed/MEDLINE and then Social Sciences Citation Index for both Zones 1 and 2. In Zone 2, best coverage by databases other than CINAHL and PubMed/MEDLINE is provided by EBSCO Nursing & Allied Health Collection Comprehensive Edition for two nursing and one medical titles; ERIC for one general and three education titles; Health Reference Center for one major medical title; PsycINFO for two psychology titles; Science Citation Index for two nursing and four medical titles; and Social Sciences Citation Index for one medical, three nursing, and four education titles. For comprehensive searching, these databases should be on the palette, particularly ERIC and Social Sciences Citation Index for education journals. While ERIC is not as productive as hoped, it also offers access to ERIC documents and other resources not easily accessed via any other source.

Results are limited to citation patterns in US nursing education journals. Future studies might include additional source titles, including other titles in Zone 1, particularly the official journals of NLN and AACN noted earlier. Also, this study is missing the international perspective. While coverage of the Journal of Advanced Nursing, the most general title in Zone 1, is far too broad, inclusion of Nurse Education Today would add a UK perspective to this research.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study will be useful to nurse researchers and educators, collection development specialists, and database providers. The data provide useful insights for developing search strategies for nursing education questions and support for collection decisions about literature in the area of nursing education. It confirms Smith's advice from a previous era, urging nurses and librarians “to consult the literature of the social and biological sciences, mathematics, cybernetics, philosophy, medicine, education and others” [3]. While this advice is offered in the broader sense, it is especially pertinent to nursing education, which looks to the literature of education and the social sciences far more than many of the other nursing specialties studied in this project.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the NAHRS task force members who volunteered to check databases: Kristine Alpi, AHIP, Carol Galganski, AHIP, and Martha (Molly) Harris, AHIP. Also, thanks to Ginny Chaskey of Cinahl Information Systems, who supplied cited journal references as spreadsheets and produced lists of non-journal cited references for the Journal of Nursing Education.

Contributor Information

Margaret (Peg) Allen, Email: pegallen@verizon.net.

Melody M. Allison, Email: mmalliso@uiuc.edu.

Sheryl Stevens, Email: sstevens@meduohio.edu.

REFERENCES

- Allen M, Jacobs SK, and Levy JR. Mapping the literature of nursing: 1996–2000. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Apr; 94(2):206–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford S. Documentation. London, UK: Crosby, Lockwood, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Smith KM. Trends in nursing education and the school of nursing librarian. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1969 Oct; 57(4):362–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly DE. Research in nursing education: yesterday—today—tomorrow. Nurs Health Care. 1990 Mar; 11(3):138–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby J. History of higher education: educational reform and the emergence of the nursing professorate. J Nurs Educ. 1999 Jan; 38(1):23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Nurses Association. Educational preparation for nurse practitioners and assistants to nurses: a position paper. New York, NY: The Association, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- The 1985 entry into practice proposal: is it relevant today? Online J Issues in Nursing [serial online]. Topic 18, 2002. [cited 31 Jul 2005]. <http://nursingworld.org/ojin/topic18/tpc18toc.htm>. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer ED. “A cooperative venture” in pursuit of professional status: a research journal for nursing. Nurs Res. 1987 Jan–Feb; 36(1):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JS, Tanner CA, and Padrick KP. Nursing's search for scientific knowledge. Nurs Res. 1984 Jan–Feb; 33(1):26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Position statement: lifelong learning for nursing faculty. [Web document]. New York, NY: National League for Nursing, 2001. [cited 31 Jul 2005]. <http://www.nln.org/aboutnln/PositionStatements/lifelonglearning01.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- National League for Nursing. [Web document]. New York National League for Nursing, 2005. [cited 31 Jul 2005]. <http://www.nln.org>. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. [Web document]. Washington, DC: American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2005. [cited 31 Jul 2005]. <http://www.aacn.nche.edu>. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing/Association Canadienne des écoles de sciences infirmières (CASN/ACESI). [Web document]. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing/Association Canadienne des écoles de sciences infirmières, 2005. [cited 31 Jul 2005]. <http://www.casn.ca>. [Google Scholar]

- Hill DR, Stickell HN. Brandon/hill selected list of print nursing books and journals. Nurs Outlook. 2002 May– Jun; 50(3):100–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Journal of Nursing Education. Information for authors. [Web document]. Thorofare, NJ: Charles B. Slack, 2005. [cited 1 Aug 2005]. <http://www.journalofnursingeducation.com/images/jneinfo.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. Information for authors. [Web document]. Thorofare, NJ: Charles B. Slack, 2005. [cited 1 Aug 2005]. <http://www.slackinc.com/allied/jcen/JCENinfo.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse educator. [serial online]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2005. [cited 1 Aug 2005]. <http://www.nurseeducatoronline.com>. [Google Scholar]