Abstract

Objectives: A bibliometric investigation was done to identify characteristics of the literature that nephrology nurses utilize. It is one component of a broader study, “Mapping the Literature of Nursing,” by the Medical Library Association's Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section Task Force to Map the Literature of Nursing.

Methods: Following a standard protocol, this project utilized Bradford's Law of Scattering to analyze the literature of nephrology nursing. Citation analysis was done on articles that were published from 1996 to 1998 in a source journal. Cited journal titles were divided into three zones, and coverage in major article databases were scored for Zones 1 and 2.

Results: During the three-year period, journals were the most frequently cited format type. Eighty-one journals were cited in Zones 1 and 2. As Bradford's Law of Scattering predicted, a small number of the cited journals accounted for the most use. Coverage is most comprehensive for cited journals in Science Citation Index, PubMed/ MEDLINE, and EMBASE. When looking just at cited nursing journals, CINAHL and PubMed/MEDLINE provide the best indexing coverage.

Conclusion: This study offers understanding of and insights into the types of information that nephrology nurses use for research. It is a valuable tool for anyone involved with providing nephrology nursing literature.

INTRODUCTION

Nephrology nursing is a specialized area of nursing that is directed towards individuals with kidney failure, and their families. The nephrology nurse practices in ambulatory care settings, such as clinics, and hospital-based dialysis centers, as well as free-standing dialysis facilities, home training programs, and transplant units. Nephrology nurses involved in the dialysis process may provide care for patients over a lengthy period of time, usually several years [1].

The spectrum of nephrology nursing practice for patients with acute and chronic renal failure includes hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and transplantation [2]. The American Nephrology Nurses' Association (ANNA) is the professional organization for this specialty. Its mission is “to advance nephrology nursing practice and positively influence outcomes for patients with kidney or other disease processes requiring replacement therapies through advocacy, scholarship, and excellence” [3]. Over 11,000 registered nurses are members [3].

Educational requirements for registered nurses working in nephrology depend on the institution in which they work. Institutions may require that the registered nurse have experience in a medical-surgical or intensive care setting [1]. Generally, entry-level preparation for practice in this specialty includes theoretical and clinical components for six weeks or more [1]. Currently, two types of certification for nephrology nurses are certified nephrology nurse (CNN), which documents proficiency for practice across the entire scope of nephrology nursing, and certified dialysis nurse (CDN), which documents entry-level practice in the dialysis setting [4–6]. Both certifications were developed by the Nephrology Nursing Certification Commission (NNCC), a member of the American Board of Nursing Specialties (ABNS), and are endorsed by ANNA [4]. The certification examinations are administered by the Center for Nursing Education and Testing (C-NET) and are available for registered nurses from the United States or US territories [5, 6]. To take the CNN examination, an applicant must have a baccalaureate degree in nursing, a minimum of 2 years' experience with at least 50% of work hours as a nephrology nurse, and at least 30 accredited continuing education credits in nephrology topics, the latter 2 criteria to be fulfilled within the 3 years before applying for certification [5]. Applicants for the CDN examination must have worked as a nephrology nurse for at least 2,000 hours and have accumulated at least 15 continuing education hours, both in the 2 years prior to the application [6]. Additionally, a nurse can become certified as an advanced practice nurse (APN) in nephrology nursing, either as a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) or nurse practitioner (NP), by completing a graduate degree in nursing that includes advanced study and clinical experience in this specialty [7].

HISTORY OF NEPHROLOGY NURSING

Nephrology nursing is a case study in the evolution of nursing and its progress. During the post–World War II era, the role of nursing began to expand and change from being subservient to physicians and hospitals. New scientific medical advances and technologies were increasing the complexity of patient care. Nursing leaders recognized and embraced this change and called for a melding of the traditional with the new. A role change from being thought of as the “physician's handmaiden” to being the “physician assistant” was necessitated by new medical and technological knowledge [8]. The need for scientific nursing knowledge became apparent. Nurses wanted to provide a total nursing care plan of action using a problem-solving approach and focusing on the patient by “maintaining the patient's individuality, maintaining physiologic functioning during illness, and protecting the patient from external causes of illness” [8].

And thus it was with nephrology nurses. “Dialysis nursing was one of the first practice areas that reflected the changing roles for nurses” [9]. As the technology expanded and the number of treatments increased in the early 1960s, nephrology nurses began taking on more responsibilities and autonomy with dialysis treatments [10]. With this expansion in responsibilities and autonomy came a hunger for knowledge about the professional needs of nurses in this fast-paced, new environment. Nephrology physicians and engineers had formed a group in 1955 called the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs (ASAIO). It was at these annual meetings that nephrology nurses first began to meet informally, a development that led in 1966 to the first symposium for dialysis nurses in Boston [11]. They formed the American Association of Nephrology Nurses (AANN) in 1969. In 1970, the name was changed to the American Association of Nephrology Nurses and Technicians (AANNT), and, in 1983, the group finalized its name as ANNA. This group continues to serve as the professional association for nephrology nurses [12]. The American Board of Nursing Specialties (ABNS) was formed in 1991, and, in 1992, nephrology nursing was formally recognized by ABNS as a specialty, using the education and practice standards created by the Nephrology Nursing Certification Board (NNCB) [13]. The NCCB is now known as the NNCC [4].

Nephrology nurses' environments are fast paced; their responsibilities are diverse, specialized, and numerous; their roles as nurses have put them on the cutting edge of the modern interpretation of nursing. Advances in scientific medical knowledge and technology for dialysis, transplantation, and other extracorporeal therapies have continued at a seemingly exponential pace since the early days. Nephrology nurses have been, and continue to be, at the forefront of these advances.

METHODOLOGY

A common methodology was used for this bibliometric study of nephrology nursing literature, as described in the overview article [14]. The predicted outcome of this study, “for any specialty, a relatively small core of journals can be expected to account for a disproportionate amount of the literature,” was based on Bradford's Law of Scattering [15]. Background information on nephrology nursing and its literature were collected. To determine if particular journals were appropriate for this project to map the literature of nursing, one clear criterion was that the selections needed to be about and for nephrology nursing. Because journals of the organizations in a nursing specialty indicate relevance and importance of the published articles, an obvious choice for nephrology nursing was the journal published by ANNA. Currently, the title of this journal is Nephrology Nursing Journal, but, during the source years of this study, its title was ANNA Journal. This journal is “a refereed clinical and scientific resource that provides current information on wide variety of subjects to facilitate the practice of professional nephrology nursing” [16]. It was listed on the “Brandon/Hill Selected List of Print Nursing Books and Journals,” a well-established standard list of credible nursing literature [17].

A number of multidisciplinary journals existed in the area of nephrology. For instance, some covered information relevant to the nephrology technician, nutritionist, social worker, occupational therapist, patient, and/or physician, as well as the nephrology nurse. None of the titles was on the “Brandon/Hill Selected List of Print Nursing Books and Journals” [17]. In the quest to ascertain if any of these titles had relevant scholarship mainly for or by registered nurses, the items were physically located at the medical library of a large health center and representative contents were assessed. None of these other source journals focused on nephrology nursing and, therefore, did not represent this nursing specialty. For these reasons, ANNA Journal was selected as the sole source journal in the area of nephrology nursing.

ANNA Journal references were reviewed for the years 1996 to 1998 as source material. The table of contents of the issues had three main sections: “Articles,” “Educational Supplement,” and “Departments,” each of which included material with references. The “Articles” sections contained refereed articles. “Educational Supplement” sections contained articles sponsored by Amgen about various anemia issues relating to renal failure. “Departments” included regular columns such as the “(ANNA) President's Message,” “Critique to Practice: Facilitating Research-based Practice,” “Case Study,” “Medication Review,” “Clinical Consult,” “Book Reviews,” “Journal Club,” and “Professional Issues.” Although all sections contained relevant information with references, only “Articles” were used for mapping the literature of nephrology nursing.

RESULTS

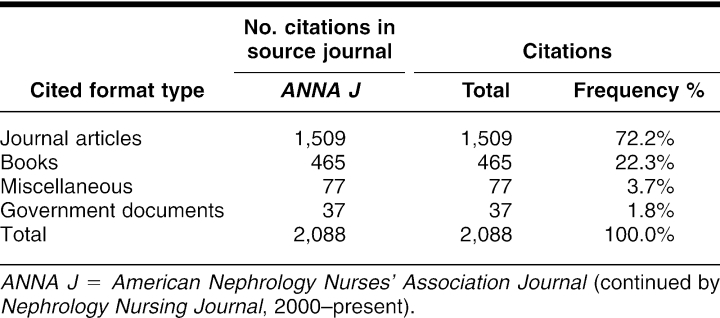

During the 3-year period of 1996 to 1998, 2,088 items were cited in ANNA Journal. Table 1 shows that these cited items were distributed by format type as journal citations (72.2%), book citations (22.3%), miscellaneous items (3.7%), and government documents (1.8%).

Table 1 Cited format types by source journal and frequency of citations

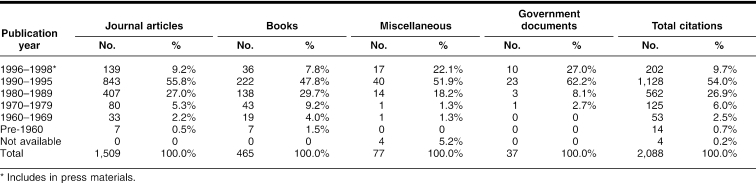

When publication years of citations were examined in Table 2, the majority of cited journal articles (55.8%), books (47.8%), miscellaneous items (51.9 %), and government documents (62.2%) were published in the years 1990 to 1995. The second largest block of citations for journal articles (27.0%) and books (29.7%) was from the years 1980 to 1989 and, for miscellaneous items (22.1%) and government documents (27.0%), from the years 1996 to 1998. Looking at all citation formats, the distribution of publication years was: 1990 to 1995 (54.0%), 1980 to 1989 (26.9%), 1996 to 1998 (9.7%), 1970 to 1979 (6.0%), 1960 to 1969 (2.5%), and pre-1960 (0.7%).

Table 2 Cited format types by publication year periods

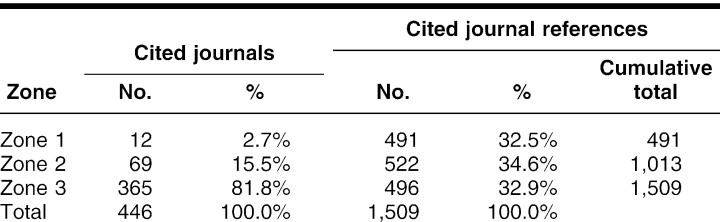

A total of 446 journals were cited, and 1,509 references were cited in Zones 1, 2, and 3. As Bradford's Law of Scattering predicted, a small number of the cited journals accounted for the most use [16]. Table 3 shows that 12 core journals were identified in Zone 1 for nephrology nursing. These 12 journals (2.7%) provided 32.5% of all the journal citations, thereby representing the most productive journals. Sixty-nine journal titles (15.5%) were found for Zone 2, which contributed the second-most productive section for journal citations. Zone 3 journal citations were provided by 365 journal titles (81.8%), making these journal titles the least productive in terms of frequency of use.

Table 3 Distribution by zone of cited journals and references

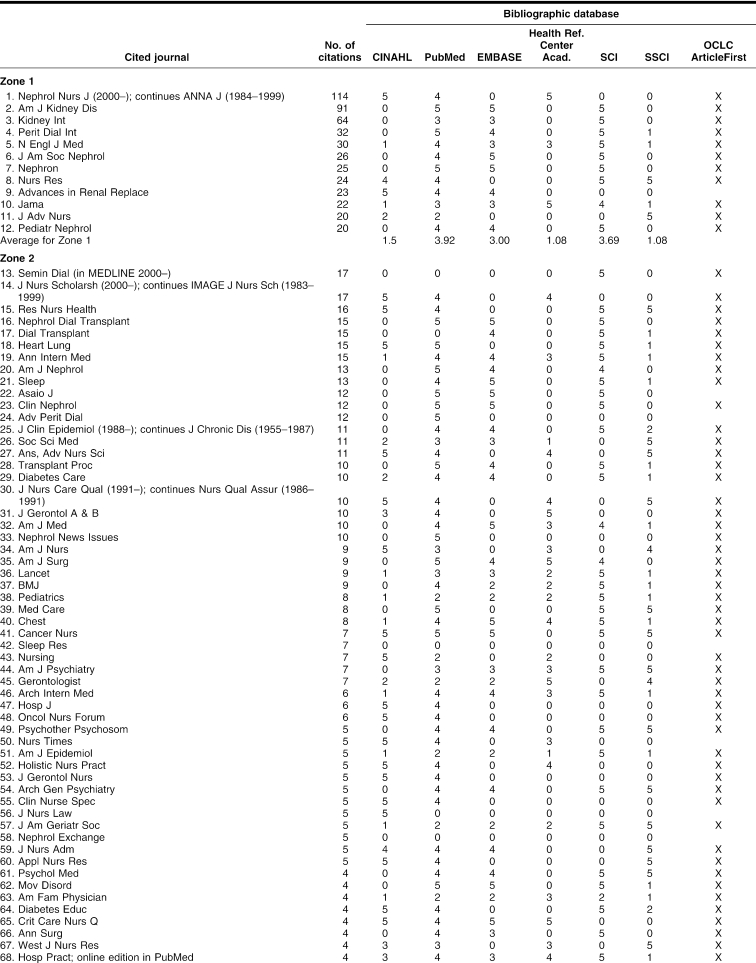

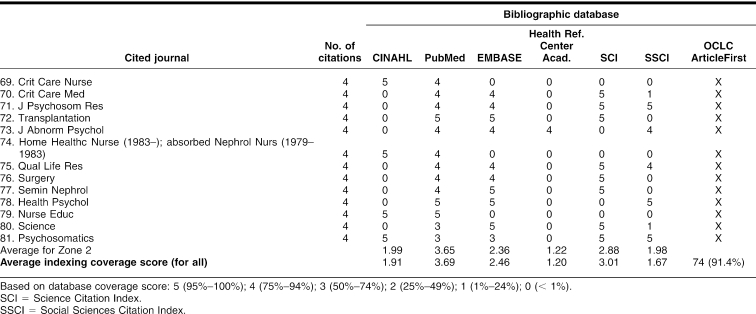

As shown in Table 4, PubMed/MEDLINE (3.92) and Science Citation Index (3.67) via Web of Science (WOS) were 1st and 2nd for indexing coverage of Zone 1 citation journal titles from the source journal articles in 1998, followed by EMBASE (3.00) and CINAHL (1.50), with Social Sciences Citation Index and Health Reference Center tying in last place (1.08). PubMed/MEDLINE (3.65) was first for indexing coverage of Zone 2 journals citation titles, followed by Science Citation Index (2.88), EMBASE (2.36), CINAHL (1.99), Social Sciences Citation Index (1.78), and Health Reference Center (1.22). OCLC ArticleFirst covered 91.7% of Zone 1 journal titles and 91.3% of Zone 2 journal titles. Despite not having abstracts or subject headings, it remains a useful comprehensive resource for journals cited in this specialty.

Table 4 Distribution and database coverage of cited journals in Zones 1 and 2

DISCUSSION

Journals provided nearly three times the cited references than did the next most frequently cited format, books. Nursing and medical information changes so quickly that dependency on journals for information is the norm and is typical of other scientific fields.

A considerable portion of cited references for journal articles (35.0%) and books (44.4%) are somewhat dated materials, from pre-1960 to 1989, with cited references for government documents (10.8%) and miscellaneous items (20.8%) to a smaller extent (Table 2). Government documents (89.2%) and miscellaneous items (74.0%) had a higher proportion of recent cited references, from 1990 to 1998, than journal articles (65.0%) and books (55.6%) during this time range. From this study, it is impossible to ascertain the timeliness of the literature used, but it is interesting to note the extent to which newer and older literature is cited. Further study to determine the currency of references cited to the article topic would interest researchers and those who depend on the materials for making clinical decisions.

A notable finding of this study is the fact that nephrology nursing journal articles use medical literature (Zone 1: 75.0%; Zone 2: 69.6%) for cited references much more than nursing journals (Zone 1: 25.0%; Zone 2: 30.4%). This explains why medical indexes cover more of the journal titles than CINAHL, the premier nursing indexing service, does. Taking into account that the majority of utilized journals are medical and not nursing journals, it is not unexpected that Science Citation Index, PubMed/MEDLINE, and EMBASE provide more comprehensive indexing coverage of those journals. Of the twelve journals cited in Zone 1, only three titles (25.0%) are distinctly nursing journals. In Zone 2, twenty-one (30.4%) of the sixty-nine journals are distinctly nursing journals. When one looks at just the nursing titles in Zones 1 and 2, the story concerning index coverage changes. Average indexing coverage for nursing journal titles only are: CINAHL (Zone 1: 3.67; Zone 2: 4.86), PubMed/MEDLINE (Zone 1: 3.33; Zone 2: 3.76), Social Sciences Citation Index (Zone 1: 3.33; Zone 2: 1.86), Health Reference Center (Zone 1: 1.67; Zone 2: 1.52), Science Citation Index (Zone 1: 1.67; Zone 2: 0.71), and EMBASE (Zone 1: 0.00; Zone 2: 0.67).

Nephrology/dialysis is the main topic of eight (66.7%) of the twelve journals of Zone 1. Zone 2 journal titles cover a wide range of medical subjects, with nephrology/dialysis being the main subject in ten (14.5%) of the sixty-nine journal titles. Zone 1 titles have a higher percentage of nephrology/dialysis–related titles than Zone 2 cited titles, which is not unexpected. Although most of the Zone 1 journals are related to nephrology/dialysis, the majority of Zone 2 journals (86.8%) came from several other areas. This demonstrates a need for the availability of diverse information resources and index content to provide comprehensive coverage for nephrology nursing research needs.

CONCLUSION

Because the function of the kidney directly affects every organ and cell of the body, information is needed from many areas in addition to specialized nephrology journals. Other important areas for nephrology nursing include cardiology, pulmonary medicine, transplantation medicine, psychiatry and psychology, epidemiology and infection control, critical care nursing, oncology, neurology, and gerontology. Nephrology is essentially interrelated with all of these medical specialties. It is important to understand that nephrology nurses rely on literature from medical and other scientific disciplines, as well as nursing, for their research and clinical needs.

The results of this study will help those who perform collection development for nephrology nursing in institutions with nephrology departments or specialty programs and nurses who care for nephrology patients in various medical settings and academic settings that have nursing programs. By knowing what journals and types of other materials are used by nephrology nurses or those nurses who provide care in some way to nephrology patients, resource providers will have objective data to assist in the decision-making process of resource selection. Also, the information benefits indexing publishers and database producers by aiding their understanding and provision of the types of information that nephrology nurses actually use for research. Insights gained from this study show publishers of cited non-nursing journals that their audience includes nephrology nurses and thus may encourage them to include additional material relevant to nephrology nursing when appropriate. Nephrology nurses will find it useful to note the wide distribution of literature that is used, and what is available to use, in nephrology nursing research, as well as what indexing publishers and database producers can be sources of literature information for them. This study provides understanding of and insights into the types of information actually used for nephrology nursing literature. It is a valuable tool for anyone involved with providing nephrology nursing literature and thus providing nursing care to nephrology patients.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Margaret (Peg) Allen, AHIP, cochair, Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section Task Force to Map the Literature of Nursing, for her steadfast guidance, assistance, and encouragement. Thanks to fellow database checkers Allen, Kristine Alpi, AHIP, Carol Galganski, AHIP, Martha (Molly) Harris, AHIP, Helen Seaton, AHIP, Priscilla Stephenson, AHIP, Mary K. Taylor, AHIP, and Pamela White for contributions to the master index. Thanks also to task force reviewers, Alpi and White, for their helpful paper comments.

REFERENCES

- Council of Nephrology Nurses and Technicians of the National Kidney Foundation (NKF). Renal career fact sheet: nephrology nurse. [Web document]. New York, NY: The Foundation, 2005. [cited 4 May 2005]. <http://www.kidney.org/professionals/CNNT/nurscnnt.cfm>. [Google Scholar]

- American Nephrology Nurses' Association (ANNA). Discover nephrology nursing. [Web document]. Pitman, NJ: The Association. [cited 4 May 2005]. <http://www.annanurse.org/download/reference/membership/discover.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- American Nephrology Nurses' Association (ANNA). About the ANNA. [Web document]. Pitman, NJ: The Association, 2005. [Cited 4 May 2005]. <http://www.annanurse.org/cgi-bin/WebObjects/ANNANurse.woa/1/wa/viewSection?s_id=1073744048&wosid=eOX1I86LuXDv3sf2I6p2xL2p3vy>. [Google Scholar]

- Nephrology Nursing Certification Commission (NNCC). About NNCC. [Web document]. Pitman, NJ: The Commission. [cited 4 May 2005]. <http://www.nncc-exam.org/about/>. [Google Scholar]

- Nephrology Nursing Certification Commission (NNCC). Certified nephrology nurse (CNN): about becoming a CNN. [Web document]. Pitman, NJ: The Commission. [cited 4 May 2005]. <http://www.nncc-exam.org/exams/cnn/facts.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Nephrology Nursing Certification Commission (NNCC). Certified dialysis nurse (CDN): about becoming a CDN. [Web document]. Pitman, NJ: The Commission. [cited 4 May 2005]. <http://www.nncc-exam.org/exams/cdn/facts.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- ANNA positions statements. Nephrol Nurs J. 2004 May– Jun; 31(3):309–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart N. Nephrology nursing 1915–1970: a historical study of the integration of technology and care. ANNA J. 1989 May; 16(3):169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers J. Reflections on the first dialysis nurse training program. ANNA J. 1989 May; 16(3):230–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton BJ, Cameron EM. Perspectives on our beginnings: 1962–1979. ANNA J. 1989 May; 16(3):201–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffart N. A professional organization for nephrology nurses. ANNA J. 1989 May; 16(3):197–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch SD. Celebrating ANNA's silver anniversary: 25 years of learning, sharing, caring and growing. ANNA J. 1994 May; 21(3):197–203. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Parker J. Nephrology nursing as a specialty. In: Parker J, ed. Contemporary nephrology nursing. Pitman, NJ: American Nephrology Nursing Association, 1998:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, Jacobs SK, and Levy JR. Mapping the literature of nursing: 1996–2000. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Apr; 94(2):206–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M, Jacobs S, and Vieira D. Task Force to Map the Literature of Nursing, Nursing and Allied Health Resources Section, Medical Library Association. Mapping the literature of nursing project protocol, August 2003. [Web document]. The Section, 2003:1–14. [cited 1 Sep 2003]. <http://nahrs.library.kent.edu/activity/mapping/nursing/protocol.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- American Nephrology Nurses' Association (ANNA). Nephrology Nursing Journal: the official journal of the American Nephrology Nurses' Association: about the journal: purpose/philosophy. [Web document]. Pitman, NJ: Anthony J. Jannetti (AJJ), 2004. [cited 4 May 2005]. <http://nephrologynursing.net/about/default.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Hill DR, Stickell HN. Brandon/Hill selected list of nursing books and journals. Nurs Outlook. 1998 Jan–Feb; 46(1):7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]