Abstract

Background

Depression is a common and important public health problem most often treated by GPs. A self-help approach is popular with patients, yet little is known about its effectiveness.

Aim

Our primary aim was to review and update the evidence for the clinical effectiveness of bibliotherapy in the treatment of depression. Our secondary aim was to identify which of these self-help materials are generally available to buy and to examine the evidence specific to these publications.

Method

Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CCTR, PsiTri and the National Research Register were searched for randomised trials that evaluated self-help books for depression which included participants aged over 16 years with a diagnosis or symptoms of depression. Clinical symptoms, quality of life, costs or acceptability to users were the required outcome measures. Papers were obtained and data extracted independently by two researchers. A meta-analysis using a random effects model was carried out using the mean score and standard deviation of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression at the endpoint of the trial.

Results

Eleven randomised controlled trials were identified. None fulfilled CONSORT guidelines and all were small, with the largest trial having 40 patients per group. Nine of these evaluated two current publications, Managing Anxiety and Depression (UK) and Feeling Good (US). A meta-analysis of 6 trials evaluating Feeling Good found a large treatment effect compared to delayed treatment (standardised mean difference = −1.36; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −1.76 to −0.96). Five self-help books were identified as being available and commonly bought by members of the public in addition to the two books that had been evaluated in trials.

Conclusion

There are a number of self-help books for the treatment of depression readily available. For the majority, there is little direct evidence for their effectiveness. There is weak evidence that suggests that bibliotherapy, based on a cognitive behavioural therapy approach is useful for some people when they are given some additional guidance. More work is required in primary care to investigate the cost-effectiveness of self-help and the most suitable format and presentation of materials.

Keywords: bibliotherapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, cost-effectiveness, depression, randomised controlled trials, self care

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a common and important public health problem and most patients are treated in primary care by their GP.1 Depression is often associated with anxiety, although people with pure anxiety disorders often have their own behavioural and cognitive strategies that are different from depression. Psychological treatments for depression, such as cognitive behavioural therapy are effective2 but increasing demand means that many patients who might benefit are unable to obtain the appropriate services. Written self-help materials or bibliotherapy based on psychological treatments of proven efficacy would seem a sensible option, providing a more accessible source of psychological help.

Self-help is often difficult to define but there is consensus that self-help books should aim to guide and encourage the patient to make changes, resulting in improved self-management, rather than just provide information. The self-help approach fits well with cognitive behavioural therapy, in which patients are encouraged to carry out work between sessions in order to challenge unhelpful thoughts and behaviours. There is a growing interest and literature on computerised cognitive behavioural therapy3 but this option is at present still of limited availability.

How this fits in

There is some evidence that self-help books (bibliotherapy) for depression can be beneficial. However, most of the books currently available in the UK have not been evaluated in randomised trials. There is some trial evidence for one self-help book based on cognitive behavioural therapy, although the evidence is difficult to generalise to primary care in the UK or elsewhere. It is still possible to recommend the cautious use of self-help books for some patients who might be more receptive to a self-help approach.

A self-help approach is often popular with patients and there are now many self-help books commercially available, although few have been empirically tested in trials.4 There have been a number of systematic reviews undertaken that demonstrate the potential benefits of bibliotherapy for a range of conditions including depression.5-7 Cuijpers8 summarised the literature on bibliotherapy on depression and Bower9 has extensively reviewed the literature on the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care, although there was only one study included that examined depression. Both suggest benefits. However, many of the older studies in these reviews had devised their own self-help materials that are no longer available.

In view of this, our primary aim was to review and update the evidence for the clinical effectiveness of bibliotherapy in the treatment of depression. Our secondary aim was to identify which of these self-help materials are generally available to buy and to examine the evidence specific to these publications.

METHOD

Search strategy

A search for systematic reviews had already been carried out as part of a larger study to identify self-help interventions for a range of mental health conditions, including depression.10 The randomised trials that had evaluated written self-help materials for depression were extracted from these systematic reviews.11-16

We carried out a further search for any randomised controlled trials that the systematic reviews might have missed using Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CCTR, limited to the years 1990–2003. We used search terms for depression combined with terms for ‘bibliotherapy’, ‘user manual’, ‘workbook’, ‘self-help’ and ‘minimal contact’. We used the Cochrane search terms for randomised controlled trials. A new database called PsiTri was also searched. The National Research Register was used to identify ongoing trials.

Electronic updates were received regularly, the last in December 2003. Reference lists of all identified papers were examined and authors and experts in the field contacted for further or unpublished work.

Inclusion criteria for randomised controlled trials

We did not set any limitations on setting. We looked for randomised controlled trials with participants aged over 16 years who had a diagnosis or symptoms of depression, with or without anxiety. Trials were included if the intervention was written material, used with minimal guidance, defined as one hour or less of professional face-to-face time or up to six 15-minute telephone calls.17 Outcome measures for either clinical symptoms, quality of life, costs or acceptability to users were required. We only included trials that compared self-help with a treatment as usual or waiting list comparison.

Data extraction

Relevant abstracts were examined by two independent researchers to exclude those that did not investigate written material. Where there was disagreement, the papers were discussed and when this did not result in consensus the papers were sent out to a third member of the team. The papers that met the inclusion criteria were obtained and data extracted. Quality was assessed using four criteria: adequacy of random allocation concealment; percentage followed up; whether a primary outcome measure had been stated; and whether an a priori power calculation had been made.

Data analysis

We were able to carry out a meta-analysis using the mean score and standard deviation of Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression18 at the endpoint of the trial for some of the studies. We used a random effects meta-analysis as this is a more conservative analysis. Tests for heterogeneity were calculated on the fixed effects meta-analysis. The effect size calculated was a standardised mean difference and this was computed using the Metan19 command in STATA version 7. The mean difference was calculated so that negative values indicated a better outcome in the group receiving the intervention.

RESULTS

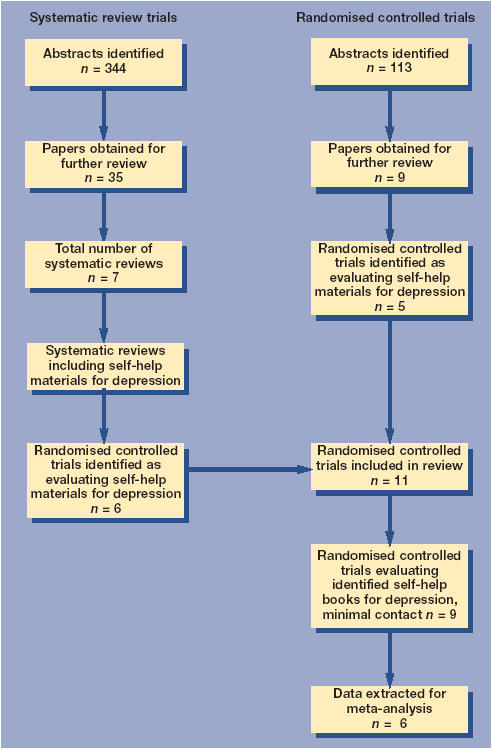

We found 11 randomised controlled trials that evaluated written self-help materials for depression and met our criteria (Figure 1). Six of these studies were identified from the systematic reviews. The dates of the studies ranged from 1983 to 2002.

Figure 1.

Flow chart detailing how six studies were identified

Two studies evaluated material that had been specifically developed for the trial and is not currently available to members of the public.12,16 Nine studies evaluated self-help books that can be purchased by patients today. Managing Anxiety and Depression20 has been evaluated in one trial,11 but it is worth noting that it has been evaluated in a further study that was excluded as subjects had contact time with a practice nurse that exceeded our limit of 1 hour.21 Feeling Good22 has been evaluated in eight trials that met our criteria.13-15,23-27 It has also been evaluated in a study of adults with physical disability,28 but this was not included in our analysis because this sample increased the likelihood of statistical heterogeneity. One other book, Control Your Depression29 was used in two of the studies, along with a group receiving Feeling Good, which was the main intervention being tested.14,24

The published trials we examined were of limited quality (Supplementary Table 1) and none fulfilled CONSORT guidelines.30 Holdsworth's study11 recruited via a GP and was the only trial conducted in the UK and in a primary care setting. The sample size was small. One hundred and six patients were recruited, but data were reported on only 62 subjects. Randomisation methods were unclear and there was no power calculation. There was no significant difference between the intervention group and control group for measures of depression at either 1 or 3 months follow-up.

The studies evaluating Feeling Good were all conducted in the US, were very similar in design and conducted by the same team. We are not aware of any conflict of interest from either the author or publisher. All had small, self-selecting samples, recruited mainly by advertisement. The participants appeared to have a very high educational level. Three of the studies recruited from the over-60 years of age group.13,15,23 Randomisation methods were not described and there was no a priori outcome measure or power calculation. In all the studies that investigated Feeling Good, research workers familiar with the intervention contacted subjects at weekly intervals and were able to answer questions about the book and encourage adherence to tasks.

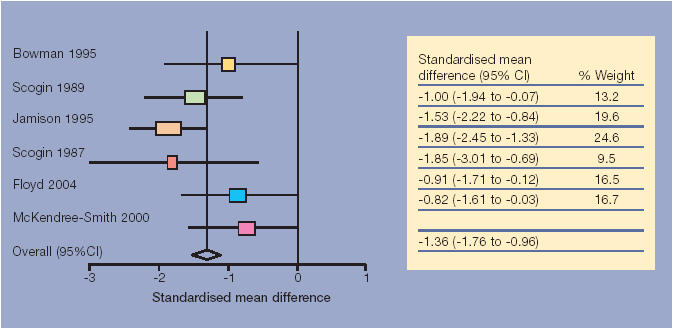

Six papers that evaluated Feeling Good provided data for a meta-analysis (Figure 2).13,14,23-26 These all gave mean values and standard deviations for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression18 at 4 weeks.

Figure 2.

Forest plot for the randomised controlled trials evaluating Feeling Good. Standardised mean differences for Hamilton rating scale for depression. Values below 0 indicate benefit for self-help.

Two papers were excluded, as they drew on data from the same sample as the included studies.15,27 All six papers reported a statistically significant improvement in outcome measures for depression. The summary estimate indicates a large improvement over 4 weeks for those given the self-help book (standardised mean difference = −1.36; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −1.76 to −0.96) and statistically significant (P<0.0001). There was no evidence for heterogeneity of effect (χ2 = 7.83, degrees of freedom [df] = 5, P = 0.16).

A summary estimate was also possible for the two studies that compared the first edition of Control your Depression with a waiting list control. The summary estimate was −0.58 (95% CI = −1.40 to 0.25), indicating that the observed improvement in the bibliotherapy condition after 4 weeks was not statistically significant. We also calculated a summary estimate for the six trials evaluating Feeling Good together with the two trials12,16 evaluating unpublished self-help materials. The summary estimate was −1.28 (95% CI = −1.68 to −0.88) and the test for heterogeneity was of borderline significance (χ2 = 13.04, df = 7, P = 0.07).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

We identified some studies that have investigated the effectiveness of self-help interventions in relieving the symptoms of depression. Overall, our meta-analysis indicates that bibliotherapy was an effective intervention, although the evidence was drawn from small studies that were overall of a poor quality. Only two self-help books for depression that are currently available for patients to buy, Managing Anxiety and Depression and Feeling Good, have been evaluated in randomised trials and the bulk of the evidence was for Feeling Good. A third book, Coping with Depression, was used in two trials where Feeling Good was the main intervention. Although our meta-analysis indicates a substantial benefit for self-help books, this relies upon six US trials evaluating Feeling Good, all of which adopt a similar methodology and were conducted by the same scientific team.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The identification of randomised trials partly through systematic reviews was a possible weakness. This relied on the search strategy of the original reviewers and we therefore may have overlooked some of the older studies. However, we carried out a rigorous search of a broad range of databases from 1990 to capture all the recent randomised trials and also examined reference lists. Self-help is a relatively recent intervention and we think it unlikely we have missed a substantial body of evidence. We have identified nearly twice as many studies as included in the Cuijpers' review of 1997.8 Nevertheless, meta-analysis of small trials is unreliable,31 publication bias is a distinct possibility and this all adds to the caution in drawing conclusions from the review. Our summary estimate that indicated a difference of 1.36 standard deviations between the self-help and control condition, was larger than reported in a systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapy versus usual treatment.2 This would seem unlikely and supports our cautious interpretation. One further limitation was that outcomes were measured at 4 weeks, so there were no data on whether the benefit extended beyond the duration of the intervention.

One important consideration is that the findings are difficult to generalise to UK primary care. Firstly, the participants were self-selecting and therefore likely to be highly motivated. They had a high education level. Scogin et al13 reported that 41% of their sample had degree level qualifications or above. Secondly, all the studies provided guidance from a research worker familiar with the self-help book, who offered advice, encouragement and answered questions on a weekly basis. Feeling Good does not offer patients advice about when to seek medical advice. Given the amount of contact the patients in the studies had with researchers the evidence suggests that self-help books can benefit some people with depression as long as they are provided with encouragement and support, thus reducing the likelihood of negative outcomes.32

Implications for clinical practice

Using self-help as the first element in a stepped care approach33 to treating depression would seem a sensible option, especially if GPs or other primary healthcare providers receive training in their use.34 Some of the newer books, Mind over Mood35 and Overcoming Depression: a Five Areas Approach,36 have associated guidance for practitioners but these might not be useful to those unfamiliar with cognitive behavioural therapy. However, more evidence on the cost-effectiveness of additional support would be needed before recommending widespread adoption of self-help books.

Self-help books for depression — format and presentation

Patients are likely to be using a range of self-help books and this was investigated during the systematic review (Box 1 and Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Compared to the style and format of the books that have been evaluated in trials it would appear that there is little or no evidence available for these materials, although three of the books we found34-36 use a cognitive behavioural therapy-based approach, similar to that used in Feeling Good.

Box 1. The evidence of self-help books used by patients.

-

▸

Identifying the availability of self-help books

Having identified all the materials from the scientific literature, we looked to see if they were commercially available in the UK. We explored the Amazon website and contacted any publishers listed in the papers we had identified in the systematic review. We also conducted a search of the websites for the Mental Health Foundation, MIND and Depression Alliance. In addition, we examined two local bookstores' sales lists to identify the bestsellers that people were buying, and a recent survey of therapists40 provided information on the most recommended publications used in practice.

-

▸

Comparing the evidence with popular and recommended books

Five self-help books were identified as being available and commonly bought by members of the public or were recommended by therapists, in addition to the three books that had been evaluated in trials. Two of these books, Mind over Mood35 and Overcoming Depression: a Five Areas Approach,36 contain a large number of worksheets and exercises, similar to a distance learning workbook, and are based on a cognitive behaviour therapy model. Mind Over Mood is frequently recommended by therapists40 and a randomised trial is currently underway in the UK to evaluate Overcoming Depression: a Five Areas Approach. Gilbert's Overcoming Depression38 is a popular book in the UK, highly recommended by therapists, with worksheets and activities, but it is not presented in a workbook format.

Both Climbing out of Depression38 and Depression — the Way out of your Prison39 are listed on various voluntary organisations websites and appear as bestsellers on the Amazon website. These books are not cognitive behavioural therapy-based but encourage psychological change using psychodynamic principles. They do not engage the reader in activities but are more focused on contemplation, understanding and reflection.

In comparison to the books evaluated in trials, Overcoming Depression is similar to Feeling Good, while Mind over Mood is similar to Control your Depression in format. Feeling Good and Control your Depression have undergone revisions since the trials were conducted but the self-help features have not changed.

All these cognitive behavioural therapy-based books cover a similar content, although differ in the style of their approach. Two other popular books encourage psychological change using psychodynamic principles.38-39 Different formats have not been compared and there is insufficient evidence at present to suggest that one format or another is more effective although the only evidence for effectiveness is for self-help based upon cognitive behavioural therapy.

The use of books in the treatment of depression within primary care looks promising. It would seem particularly appropriate for people with depression of milder severity where medication is not necessarily the preferred option. It might also help in the self-management of more chronic disorders. We looked at a small range of self-help books available for the treatment of depression and only two of these had been evaluated in trials. There is a suggestion of potential benefit for books based upon cognitive behavioural therapy, but there is certainly a need for more evidence to support their use in a health service setting as the current studies are small and of dubious generalisability to primary care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Department of Health for funding the project. The publishers and book stores for assisting in the identification of self-help books for depression. Peter Bower, Senior Research Fellow, National Primary Care Research and Development Centre, for generously providing advice for this paper.

Supplementary information

Additional information accompanies this article at: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/journal/index.asp

Funding body

Department of Health, Policy Research Programme

Competing interests

Chris Williams is author of one of the self-help books mentioned in the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.NHS Centre for Reviews & Dissemination. Improving the recognition and management of depression in primary care. Effective Health Care. 2002:7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Churchill R, Hunot V, Corney R, et al. A systematic review of controlled trials of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of brief psychological treatments for depression. Health Technol Assess. 2001;5(35) doi: 10.3310/hta5350. www.ncchta.org/projectdata/1_project_record_published.asp?PjtId=1003&SearchText=You+Selected++AND++AND (accessed 6 Apr 2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaltenhaler E, Shackley P, Stevens K, et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for depression and anxiety. London: Department of Health; 2002. The NHS Health Technology Assessment Programme Volume 6 number 22 www.ncchta.org/ProjectData/3_project_record_published.asp?PjtId=1254 (accessed 30 Mar 2005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKendree-Smith NL, Floyd M, Scogin FR. Self-administered treatments for depression: a review. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;59:275–288. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scogin F, Bynum J, Stephens G. Efficacy of self-administered treatment programs: meta-analytic review. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1990;21:42–47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould RA, Clum GA. A meta-analysis of self-help treatment approaches. Clin Psychol Rev. 1993;13:169–186. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marrs RW. A meta-analysis of bibliotherapy studies. Am J Community Psychol. 1995;23:843–870. doi: 10.1007/BF02507018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuijpers P. Bibliotherapy in unipolar depression: a meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioural Therapy and Psychiatry. 1997;28:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(97)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bower P, Richards D, Lovell K. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of self-help treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:838–845. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis G, Anderson L, Araya R, et al. Self-help interventions for mental health problems. Department of Health expert briefing. London: DoH; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holdsworth N, Paxton R, Seidel S, et al. Parallel evaluations of new guidance materials for anxiety and depression in primary care. Journal of Mental Health. 1996;5:195–207. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wollersheim JP, Wilson GL. Group treatment of unipolar depression: a comparison of coping, supportive, bibliotherapy and delayed treatment groups. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1991;22:496–502. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scogin F, Hamblin D, Beutler L. Bibliotherapy for depressed older adults: a self-help alternative. Gerontologist. 1987;27:383–387. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scogin F, Jamison C, Gochneaur K. Comparative efficacy of cognitive and behavioural therapy for mildly and moderately depressed older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:403–407. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scogin F, Jamison C, Davis N. Two-year follow-up of bibliotherapy for depression in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58:665–667. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidt MM, Miller WR. Amount of therapist contact and outcome in a multidimensional depression treatment program. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:319–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuijpers P, Tiemens B, Willemse G. Minimal contact therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(Issue 2) Art, No: CD003011. (DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003011) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradburn MJ, Deekes JJ, Altman DG. METAN — an alternative meta-analysis command. Stata Technical Bulletin. 1998;44:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holdsworth N, Paxton R. Managing anxiety and depression. London: Mental Health Foundation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards A, Barkham M, Cahill J, et al. PHASE: assessing self-help education in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:746–770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burns DD. Feeling good—the new mood therapy. New York: Avon Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Floyd MR. Cognitive therapy for depression: a comparison of individual psychotherapy and bibliotherapy for depressed older adults. Behaviour Modification. 2004;28:297–318. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKendree-Smith NL. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama; 2000. Cognitive and behavioural bibliotherapy for depression: an examination of efficacy and mediators and moderators of change. Phd Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowman D, Scogin F, Lyrene B. The efficacy of self-examination therapy and cognitive bibliotherapy in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Psychotherapy Research. 1995;5:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jamison C, Scogin F. The outcome of cognitive bibliotherapy with depressed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:644–650. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith NM, Floyd M, Jamison CS, Scogin F. Three-year follow-up of bibliotherapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:324–327. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landreville P, Bissonnette L. Effects of cognitive bibliotherapy for depressed older adults with a disability. Clin Gerontol. 1997;17:35–55. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewinsohn PM, Munoz RA, Youngren MA. Control your depression. London: Simon & Schuster Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–1194. www.consort-statement.org/revisedstatement.htm (accessed 30 Mar 2005) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Dickersin K, Davey-Smith G. Problems and limitations in conducting systematic reviews. In: Egger M, Davey-Smith G, Altman DG, editors. Systematic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. London: BMJ Books; 2001. pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scogin F, Floyd M, Jamison C, et al. Negative outcomes: what is the evidence on self-administered treatments? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:1086–1089. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, Thomas R. Educational and organisational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care. JAMA. 2003;289:3145–3151. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitfield G, Williams CJ. The evidence base for CBT in depression: delivering CBT in busy clinical settings. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2003;9:21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenberger D, Padesky CA. Mind over mood: change how you feel by changing the way you think. New York: The Guildford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams C. Overcoming depression: a five areas approach. London: Arnold; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert P. Overcoming depression. London: Robinson Publishing Ltd; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atkinson S. Climbing out of depression. Oxford: Lion Publishing; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowe D. Depression: the way out of your prison. London: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keeley H, Williams CJ, Shapiri D. A United Kingdom survey of accredited cognitive behaviour therapists' attitudes towards and use of structured self-help materials. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2002;30:191–201. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.