Abstract

Background

Migraine is poorly managed in primary care despite a high level of morbidity. The majority of sufferers use non-prescription medications and are reluctant to seek help but the reasons for this are not understood.

Aim

The aim of this study was to develop a research partnership between migraine sufferers and healthcare professionals to synthesise tacit and explicit knowledge in the area. Building upon this partnership, a further aim was to explore what it is to suffer with migraine from patients' perspectives in order to inform health service delivery.

Design

Qualitative interview study involving healthcare professionals and patient researchers.

Setting

A purposeful sample of eight migraine sufferers who had attended a local intermediate care headache clinic.

Method

A consensual qualitative approach.

Results

Migraine had a high and unrecognised impact on quality of life. ‘Handling the beast’ was a central metaphor that resonated with the experience of all sufferers who sought to control their problem in different ways. Three major themes were identified: making sense of their problem; actively doing something about it either through self-help or professional advice; being resigned to it.

Conclusion

Despite a significant impact on the quality of life of migraine sufferers and their families, their needs remain largely unmet. Useful insights can be obtained when patients and professionals work together in true partnership but the time and effort involved should not be underestimated. Further research is needed to identify why there are major deficiencies in delivering care in this common problem.

Keywords: migraine, patient research, qualitative research, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

The impact of migraine

Migraine affects 7.6% of males and 18.3% of females in England.1 Measures of health-related quality of life are similar to patients with other chronic conditions, such as arthritis and diabetes,2 and worse than those with asthma.3 One in three migraine sufferers believe that their problem controls their life4 and the impact extends to family and friends.5

Involving patients in research

Consumer involvement in research is an NHS priority.6,7 By bringing the unique perspectives as active negotiators, consumers can make research more relevant to the needs of the NHS.8,9 However, there is no consensus about what constitutes successful involvement.10 Although the area has developed with an emphasis on the qualitative research domain,11,12 the majority of studies still differentiate between the researcher and those researched upon.

Our approach recognises that patients are equal partners and have the experience and skills that complement those of researchers. It was based on a scoping study that found that good professional–patient partnerships require: a working context in which power differences are recognised; mutually respectful relationships between all partners; flexibility in the methods of research; and adequate resources of time, training and money to enable all partners to contribute effectively.13

How this fits in

Migraine has a high impact on the lives of sufferers and their families but the needs of migraine sufferers are largely unmet. Despite the rhetoric, few studies meet the principles of consumer involvement in NHS research regardless of its recognised importance. Migraine sufferers control their problem in different ways: making sense of their problem, actively doing something about it or being resigned to it. GPs do not appreciate the impact of migraine and patients do not consult because of poor previous experience. Addressing the needs of migraine sufferers within the context of an intermediate care service is a useful option. This study demonstrates that true research partnerships between patients and healthcare professionals can be developed to make research more relevant to the needs of the NHS. However, the time and effort involved should not be underestimated.

Aims of study

Our aims were:

To develop a research partnership between migraine sufferers and healthcare professionals who had an interest in the area with the objective of synthesising tacit and explicit knowledge in the area;

To identify and raise awareness of what it is to suffer from migraines from patients' perspectives, in order to improve the management of migraine;

To inform the development of a local primary care trust-based headache intermediate care clinic (www.headache.exeter.nhs.uk) and contribute to the dialogue of how headache services should be delivered at a national level.

METHOD

Methodology

Qualitative research has been developed within a number of traditions that vary in their philosophical assumptions and methodological focus. We used a combination of two approaches, both of which see research and the construction of knowledge as socially constructed processes. Grounded theory involves rigorously extracting and systemising the concepts, categories and themes from the evolving data. Validity, or trustworthiness, is checked by ensuring that the emergent theory be recognisable and relevant to those studied.14 Participatory research focuses on the inter-relationship between knowledge and power. It is based on a critical epistemology that sees research as an instrument for instigating social change and articulating the voices of marginal groups.15 We call our methodology consensual qualitative research: all aspects of our research — deciding the research topic and question, planning the design and methodology, gathering and analysing the data, were decided upon through mutual discussion and consensus in a series of meetings of a research team that comprised a mixed group of patients and professionals.

Initially, five patient and three professional researchers got to know one another through a set of conversations and developed a framework to negotiate and share ideas. We agreed to explore patients' own accounts of their ‘migraine journeys’ that were to be shared with other migraine sufferers rather than with professionals.

We held a further series of meetings that included mutual learning, role-plays and pilot interviews, to work out how best to conduct interviews that would enable participants to be open with what they told us. This suggested that patient researchers and participants preferred an informal conversational style interview, which led to the development of a broad topic guide. We allowed our research process to develop spontaneously. Further details of this process is beyond the scope of this paper but will be published elsewhere.

Recruitment of patient researchers

We wrote to patients who had attended a local intermediate care headache clinic, advertised through local press and word of mouth, and through an organisation for patients with migraine. Sufferers were invited to an open meeting to develop a headache research agenda. A number of meetings resulted in a core group of five patients who were keen to pursue a research project. They were joined by three professionals: a clinical psychologist with an interest in qualitative and consumer-led research; a GP who led a local headache clinic; and a research manager who administered the research unit of the general practice where the project was undertaken.

Recruitment of participants

Study participants were recruited from those who had attended the local headache clinic and had received a diagnosis of migraine. The characteristics of participants including the impact of their problem are shown in Table 1. Our aim was to recruit a purposeful sample that represented the age/sex/impact distribution of patients seen in our local intermediate care headache clinic. Recruitment was stopped when no further categories emerged in the analysis of two consecutive interviews.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants that took part in the study.

| Participant | Age | Sex | HITa disability score at entry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 46 | F | 66 |

| 2 | 54 | M | 80 |

| 3 | 30 | F | 78 |

| 4 | 61 | F | 72 |

| 5 | 33 | F | 64 |

| 6 | 51 | M | 66 |

| 7 | 56 | F | 64 |

| 8 | 50 | F | 74 |

HIT = headache impact test.

HIT reflects the impact of headache on daily activities with a score of over 56 indicating a ‘substantial impact’ (range = 36–84).

Data collection

An initial question framework was developed around key milestones in the headache journey as identified by patient researchers. This was then modified through a mutual learning process into a focused conversation, with two patient researchers working together to interview each participant. The interviews were undertaken at a health centre with the GP researcher available for support if needed. Interviews were taped but not transcribed. There was a debrief after each interview, followed by a process of consensus qualitative data analysis at a later date.

Data analysis

We adopted a consensual interpretative approach. The research team listened to each tape together. Key statements that were relevant to our research focus or meaningful to any one of the team were transcribed, and grouped into categories based on group discussion about their meaning. At completion of tape analysis, we collectively reviewed all the categories, cross-referenced, refined and defined them into core themes with typical quotes for each theme.

An important feature of qualitative research is validation of the data. To this end, we invited all participants to a meeting where our analysis was presented and further modified in the light of discussion and feedback.

RESULTS

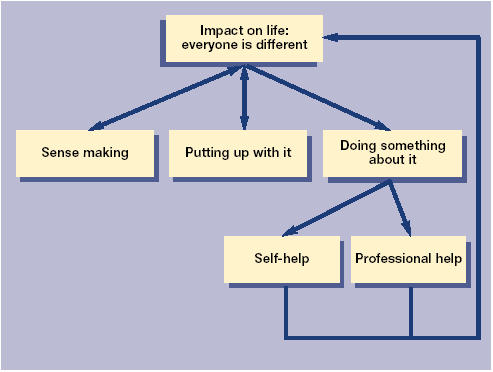

Analysis of our data revealed the emergence of an over-riding theme — the impact of migraine on sufferers' lives. ‘Handling the beast’ was a metaphor that resonated with participants and researchers and this in turn was associated with three behaviours — sense making, putting up with it and doing something about it (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Main themes for migraine suffers.

Impact on life (everyone is different)

Three aspects of impact on life were identified:

Physical and psychological impact — all participants identified severe impact on the physical side of their life.

‘You can't sleep because your head hurts on the pillow.’

‘It's the pain, it frightens me sometimes, you think you might die.’

Accompanying thoughts of death due to physical impact were thoughts around suicide:

‘The pain got so bad that I asked my partner to kill me.’

‘You can't commit suicide when you have got one and when it's over you feel so much better and relieved that you don't want to.’

There were also other physical and psychological implications other than pain:

‘The worse bit is being sick as it just takes over.’

‘I feel a sense of failure when I have a headache.’

Impact on family and social life — the impact of migraine extends beyond the individual to family, friends and colleagues:

‘Migraine has prevented me from going out and enjoying myself and having a drink.’

‘My husband says, “oh no, not another headache” — his face says it all.’

‘My son is only 11 and he has never known me any different.’

‘… my children have had to learn to put their own needs on hold.’

Impact on career —migraine impacts upon career choice and development. Many employers are not sympathetic:

‘I was off work for 5 years with a migraine. It became easier not to go out — it's a shame I wasted all those years.’

‘Do I have to admit I have got this and get signed off again?’

‘It affected my career choice.’

‘New employer doesn't understand migraine.’

Patient researchers and participants all emphasised the personal and individual nature of migraine. While common themes and categories emerged, it was recognised that everyone is different and experiences these themes differently. To some, the impact was such to express in terms of suicidal thoughts. A recurring theme was that the impact of migraine is not understood by non-sufferers. The implication is that it is not an illness but malingering:

‘As a child my teacher used to think I was malingering.’

‘How you can say you have got a headache and can't come to work — it sounds pathetic.’

Taking an overall view, ‘handling the beast’ was a metaphor for migraine that emerged during our analysis of the data. It was a term produced by one of the patient researchers during the latter stages of analysis, which resonated strongly with all researchers and participants during feedback of our findings. This conveyed a sense of a powerful, menacing creature, ever-lurking and ready to strike, with which the sufferer (and their family) had to develop some sort of relationship in order to ‘handle’ it:

‘You talk about migraine as though it is a person, well it is, it's like a part of you — a shadow.’

‘Migraines make you feel very vulnerable. You need to be able to control your life and not be dependent on anyone’

The final three themes describe how sufferers handled ‘the beast.’

Making sense of the problem

There was a need to understand what was happening and to place the problem in the context of their lives — ‘uncertainty leads to panic’. Some sufferers attempted to make sense within a physical framework, while others were still struggling for meaning:

‘Worse before or after a period.’

‘When I am worked up about something I am fine and then when I relax, I am ill.’

‘It is so hard to understand.’

A recurring theme was the value of talking to others, sharing experiences and exploring meaning:

‘It has been very helpful to be able to talk to and listen to other people who suffer from migraine.’

‘When you realise that other members of the family have migraine you feel the battle is over — you understand why you get them’.

As humans we look for patterns in the experience of our lives, searching for relationships and regularities. Some patients created meaning within a physical framework of cause and effect and others were still searching for meaning. However, all participants and patient researchers had found the opportunity of talking to a healthcare professional who had an interest in the subject valuable.

Putting up with it

A number of migraine sufferers were resigned to their problem:

‘It has made me an extremely pessimistic and fatalistic person.’

‘Why do I bother to be so careful because it doesn't seem to bring dividends.’

‘Tablets just take the edge of it so I can do what I have to do — just get by.’

‘To some extent I am beginning to see it as a disability.’

The majority of migraine sufferers are not under regular medical care and are fatalistic about their problem. We did not explore reasons for this but these may include the intermittent nature of the disease, failure to appreciate therapeutic possibilities, or poor experience with previous medical encounters.

Doing something about it

A number of sufferers actively sought either self-help or help from others:

‘Tried every over-the-counter treatment.’

All participants had sought triggers for their problem:

‘Your body has got to be regimented, you can't do anything out of the ordinary.’

‘I have tried to be so careful, no alcohol, no coffee, lots of water, try to sleep properly.’

Participants engaged in a great deal of self-help, both in terms of managing their lives and looking for remedies — particularly within the field of complementary medicine. Self-help was frequently a result of poor experience within the medical service. In many cases, patients felt that GPs and other doctors did not take the condition seriously and that they were unhelpful:

‘I have been upset by the lack of sympathy from doctors.’

‘I would like doctors to take migraines more seriously and understand how it affects people.’

‘I was told by the psychiatrist that only women get migraines — I must be mentally ill.’

Often doctors were reluctant to treat adequately:

‘Doctors try and wean me off the drugs.’

‘I suggest that doctors find more out about it because if I can, they should surely be able to?’

‘So many times I walked out crying from feeling so frustrated.’

However, the experience was not all negative and we were able to identify some positive benefits, particularly from the intermediate care headache clinic that all participants had attended:

‘I was surprised to find the medication had made a difference.’

‘The biggest landmark is coming here [to the clinic].’

‘The comfortable time came when I had been to the headache clinic.’

An important theme was the advice to other sufferers to read up about their condition before they go to the doctor:

‘Self-knowledge of the condition really helps. If you go into the doctors' [surgery] without any idea, it is a real hit or miss situation.’

‘With your experience and research try and talk to them and convince them you know something about it — you are in a position of strength.’

Overall, the advice to doctors was to take the condition seriously and sympathetically, acknowledging that migraine is more than just a headache:

‘Be sympathetic — reassure that it is a genuine illness and that patients can't help it; don't lead them to think there is a cure, but that they can manage it.’

‘Doctors should take it seriously — but it is hard for them because they can't know what you know from experience.’

The majority of our participants were actively seeking help for their problem through different avenues including many complementary and alternative approaches. The recurring theme was that the medical profession does not address the needs of sufferers adequately, but that satisfactory outcomes can be achieved by delivering care from a doctor with a special interest in the area.

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

The impact of migraine

We found a significant impact on the lives of participants and their families, both physical and psychological. Sufferers adopted strategies of sense-making, resigning themselves to the problem or actively doing something about it. Patients felt that doctors frequently do not appreciate the impact of migraine or are able to invest the time to listen to the patient sympathetically. However, it seemed that in the context of this study, positive benefit was obtained by seeing a physician with a special interest in headache who had the time to listen and take the condition seriously.

Involving patients in research

While accepting a lack of rigour in the traditional sense of qualitative research and accepting a perspective that was more influenced by action research, our impression was that this consensual, reiterative methodology, where different stakeholders bring different insights to the investigation, yielded a valuable approach that captured the experience of migraine, as it affected our subjects in ways that traditional research may have overlooked.

We identified four important factors for the success of the project:

Articulate a vision but avoid detailed aims and objectives. Although we were clear about our overall aim — reducing the burden on headache sufferers — we allowed the project to evolve with time;

Encourage diversity and rich interaction to facilitate connectivity and feedback. This required that all stakeholders were equally valued and a high level of trust between participants;

Don't underestimate the resources of time and effort that are required for successful collaborative working. Trust takes time to build. It was over a year from our initial meeting before our interviews took place;

Make it fun.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our sample was drawn from patients who had been referred to a headache clinic who may not reflect the experience of the population. In particular, the impact of their headache was greater than the population presenting to primary care. The sample size, typical of qualitative research, was small. However, the aim of qualitative research is not generalisability and the accounts we present do not necessarily reflect those of all migraine sufferers.

A possible weakness was the potentially superficial analysis of data. We elected not to transcribe our interviews for two reasons. Firstly, our resources were limited particularly in terms of the time that our consumer researchers could commit. Secondly, and more importantly, we felt that the interaction between patient and professional researchers that was stimulated by listening to the tapes developed a richer dynamic. It could also be argued that there was bias in our analysis due to fellow sufferers analysing the tapes. However, the aim of our project was not to eliminate bias, but to mobilise the insights of patients with migraines using sufferers as researchers as well as contributors. Along similar lines, we felt that the validation of data by sharing it with our participants was a valuable source of insights.

Setting our findings within the existing literature

The impact of migraine

Our study confirms and builds upon other studies in the area. Two previous qualitative migraine studies have been published.16,17 These identified the impact of migraine on sufferers and the fact that they were actively involved in treating and preventing their headaches as key decision-makers and as such, a resource for effective management of their problem. The quantifiable burden of headache in the community has been shown to be substantial.3 For example, two-thirds of sufferers search for better treatment and the majority use non-prescription medication.4 The indirect costs of migraine due to absence and reduced effectiveness at work has been estimated at over £600 million a year.18

The delivery of headache services

The Migraine Action Association, a UK patient organisation, has described four features valued by headache sufferers: timely access to local services in primary care rather than hospital-based; interested staff (whether doctor or nurse) who take them seriously; sufficient information and explanation, and opportunity to express their needs and preferences; and follow-up when needed. Reflecting these concerns, it has been suggested that although GPs should provide first-line headache services they should be supported by GPs with a special interest operating from intermediate care headache clinics.19 Our study, although limited in size and generalisability, demonstrates that a GP-led intermediate care clinic can provide a service that is of value to patients.

An important initiative to improve the relevance of research is the involvement of consumers as active negotiators for change in the research process. By contributing their unique perspectives, consumers can make research more relevant to their needs and therefore to the needs of the NHS.9 Consumers have the experience and skills that complement those of researchers, and are seen as equal partners with health professionals, scientists and policy makers.12 However, a national survey of recently completed NHS research projects found that only 17% had any form of consumer involvement and of these, only a small number met the principles of successful consumer involvement.20

Implications for further research and practice

Further qualitative research is needed to explore why patients do not seek help despite the significant impact migraine makes upon the quality of their lives. Research is also needed into why GPs find migraine difficult to manage and how the process could be facilitated. From a service delivery perspective, the implications of our research suggest that an intermediate care setting is a useful option for addressing the significant problems that the management of migraine poses and should be further explored.

We conclude that useful insights can be obtained from developing the research approach we have described where patients and professionals work together as co-producers of research. However, this process requires a large investment of time for all researchers that should not be underestimated.

Funding body and reference number

St Thomas Medical Group is a research practice that receives funding from the NHS R & D Executive. The project was supported with a grant of £2000 each from the Migraine Action Association and Folk.us, University of Exeter

Ethics committee reference number

The North and East Devon Local Research Ethics Committee (2002/6/97)

Competing interests

D Kernick is the Vice Chairman of the British Association for the Study of Headache and has received research and educational funding from a number of pharmaceutical companies in the field of migraine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steiner T, Scher A, Stewart F, et al. The prevalence and disability burden of adult migraine in England and their relationships to age, gender and ethnicity. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(7):519–527. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart A, Greenfield S, Hays R, et al. Functional status and wellbeing of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1989;262:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Terwindt G, Ferrari M, Tijhus M, et al. The impact of migraine on quality of life in the general population. The GEM study. Neurology. 2000;55:624–629. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.5.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dowson A, Jagger S. The UK migraine patient survey: quality of life and treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 1999;15(4):241–253. doi: 10.1185/03007999909116495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipton R, Bigal M, Kolodner K, et al. The family impact of migraine: population-based studies in the US and UK. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(6):429–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baxter M. Consumers and research in the NHS: consumer issues within the NHS. London: Department of Health; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health. Research and development for a first class service: R & D funding in the new NHS. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pilgrim D, Waldron L. User involvement in mental health service development: how far can it go? J Mental Health. 1998;7:95–104. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanley B, Bradburn J, Gorin S, et al. Involving consumers in research and development in the NHS: briefing notes for researchers. Winchester: Consumers in NHS Research Support Unit; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boote J, Telford R, Cooper C. Consumer involvement in health services research: a review and research agenda. Health Policy. 2002;61:213–236. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austoker J. Involving patients in clinical research. BMJ. 1999;319:724–725. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A. Consumer participation in research and healthcare. BMJ. 1997;315:499. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7107.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxter L, Thorne L, Mitchell A. Small voices, big noises. Lay involvement in health research: lessons from other fields. Exeter: Washington Singer Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: an overview. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. California: Sage Publishers; 1994. pp. 273–285. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park P. The discovery of participatory research as a new scientific paradigm: personal and intellectual accounts. Am Sociol. 1992;23:29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Velasco I, Gonzalez N, Etxeberria Y, Garcia-Monco J. Quality of life in migraine patients: a qualitative study. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(9):892–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters M, Abu-Saad H, Vydelingum V, Dowson A, Murphy M. Patients decision making for migraine and chronic daily headache management — a qualitative study. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(8):833–841. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cull RE, Wells NAG, Miocevich ML. The economic cost of migraine. British Journal of Medical Economics. 1992;2:103–115. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowson A, Lipscombe S, Sender J, et al. New guidelines for the management of migraine in primary care. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18:414–439. doi: 10.1185/030079902125001164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Telford R, Boote J, Cooper C, Stobbs M. Principles of successful consumer involvement in NHS research: results of a consensus study and national survey. Sheffield: ScHARR University of Sheffield; 2003. [Google Scholar]