When Frida Kahlo was 18 years old and preparing to study medicine, she was already a high-achieving and free-thinking spirit in male-dominated Mexican society. It seemed clear that she would go far. But then, a horrific and mutilating traffic accident shattered both her spine and her plans. From then on, her talents and spirit were set on an entirely new path.

Bored by long hospital stays, she took up painting, and became the most famous female painter of all time. Some 30 years, and as many orthopaedic operations, later she died and became an icon, adopted by feminists, leftists and Mexicans, inspired by the several examples of her life. She married and had affairs with great men, including Diego Rivera and Leon Trotsky, but lived a life marred by pain, disability, isolation and loss.

It was a large, extraordinary life, the facts of which are covered in Herrera's definitive biography1 and Salma Hayek's faithful, partly wonderful but inevitably superficial, Hollywood film. Kahlo's own illustrated diary, and her paintings (almost half of which are on display at the Tate Modern, until 9 October) tell a more complicated story.

Like encounters in general practice, the paintings stand on their own, but are better appreciated against the narrative of a remarkable personality who lived an extraordinary life. Kahlo painted primarily for herself, expressing how she felt. The paintings contain great detail, widespread Mexican forms and imagery, brutal frankness, masks, masquerades and coded messages. Many are striking but, for Kahlo who painted life as she saw it, none were surreal.

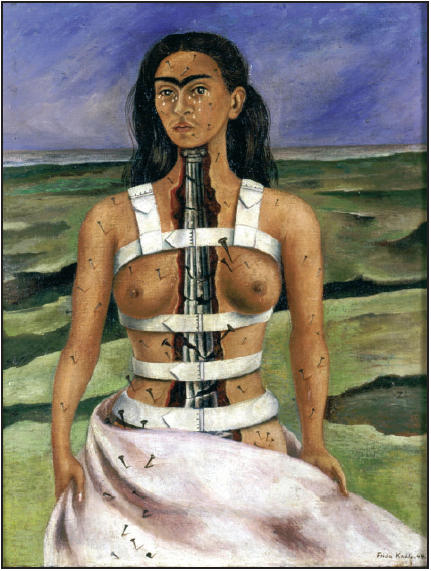

The Broken Column (La columna rota) 1944 Oil on canvas 400 × 305 mm Museo Dolores Olmedo Patino, Mexico City

The paintings fall into several groups: the early pictures as she was finding her style; the numerous self-affirming portraits (‘I paint myself, because I am often alone, because I know myself best’); the explicit portrayals of life events, such as My Birth (loaned by Madonna), a miscarriage, her failed marriage and the suicide of a friend; the still lives of Mexican fruit; ironic commentaries on the US (‘gringolandia’) and her world views, comprising naturalism, communism and the continuity and force of life. Many are oils painted on metal or wood, enabling her distinctive approach to surface and touch.2

A common feature is duality: the body she lost and the body she had; her heterosexual and lesbian affairs; traditional and modern ways; Mexican and European, the closeness and treachery of those she loved; sadness and joy; the community of her world view and the loneliness of her position.

Kahlo had much to be miserable about, but her nature was to live life as fully and as passionately as she could:

‘There is nothing more precious than laughter and scorn — It is strength to laugh and lose oneself, to be cruel and light. Tragedy is the most ridiculous thing “man” has.’

According to the art historian Helga Prignitz-Poda,3 The Broken Column represents not only Kahlo's obvious physical injuries, but also the damage to her self-confidence during a traumatic childhood and the pain of Diego Rivera's frequent affairs with other women (most notably, Kahlo's sister). What Kahlo embodies in The Broken Column is her double life: outwardly proud in order to cover up the pain inside. Kahlo herself wrote:

‘Waiting with anguish hidden away, the broken column, and the immense glance, footless through the vast path … carrying on my life enclosed in steel … If only I had his caresses upon me as the air touches the earth.’

There were several Fridas and living them all was a struggle. When a leg finally had to be amputated, due to osteomyelitis and gangrene, she wrote defiantly:

‘Feet, what do I want them for if I have wings to fly?’

But this was one mutilation too far. It broke her will to live.

Kahlo lives on, via the vivid depictions and sharing of her physical and psychological pain. John Berger wrote of Kahlo:

‘That she became a world legend is in part due to the fact that in these dark days of the new world order the sharing of pain is one of the essential preconditions for a refunding of dignity and hope.’2

Kahlo wrote that she drank to drown her pain, but the pain learned to swim. Her body disintegrated, but not her spirit. Across the last painting she scrawled her final, parting message ‘VIVA LA VIDA’.

REFERENCES

- 1.Herrera H. Frida. A biography of Frida Kahlo. London: Bloomsbury; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger J. Frida Kahlo; in the shape of a pocket. London: Bloomsbury; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prignitz-Poda H, Frida Kahlo. The painter and her work. New York: Schirmer/Mosel; 2004. [Google Scholar]