Social marketing applies commercial marketing strategies to promote public health. Social marketing is effective on a population level, and healthcare providers can contribute to its effectiveness.

What is social marketing?

In the preface to Marketing Social Change, Andreasen defines social marketing as “the application of proven concepts and techniques drawn from the commercial sector to promote changes in diverse socially important behaviors such as drug use, smoking, sexual behavior... This marketing approach has an immense potential to affect major social problems if we can only learn how to harness its power.”1 By “proven techniques” Andreasen meant methods drawn from behavioural theory, persuasion psychology, and marketing science with regard to health behaviour, human reactions to messages and message delivery, and the “marketing mix” or “four Ps” of marketing (place, price, product, and promotion).2 These methods include using behavioural theory to influence behaviour that affects health; assessing factors that underlie the receptivity of audiences to messages, such as the credibility and likeability of the argument; and strategic marketing of messages that aim to change the behaviour of target audiences using the four Ps.3

How is social marketing applied to health?

Social marketing is widely used to influence health behaviour. Social marketers use a wide range of health communication strategies based on mass media; they also use mediated (for example, through a healthcare provider), interpersonal, and other modes of communication; and marketing methods such as message placement (for example, in clinics), promotion, dissemination, and community level outreach. Social marketing encompasses all of these strategies.

Communication channels for health information have changed greatly in recent years. One-way dissemination of information has given way to a multimodal transactional model of communication. Social marketers face challenges such as increased numbers and types of health issues competing for the public's attention; limitations on people's time; and increased numbers and types of communication channels, including the internet.4 A multimodal approach is the most effective way to reach audiences about health issues.5

Figure 1 summarises the basic elements or stages of social marketing.6 The six basic stages are: developing plans and strategies using behavioural theory; selecting communication channels and materials based on the required behavioural change and knowledge of the target audience; developing and pretesting materials, typically using qualitative methods; implementing the communication programme or “campaign”; assessing effectiveness in terms of exposure and awareness of the audience, reactions to messages, and behavioural outcomes (such as improved diet or not smoking); and refining the materials for future communications. The last stage feeds back into the first to create a continuous loop of planning, implementation, and improvement.

Fig 1.

Social marketing wheel

Audience segmentation

One of the key decisions in social marketing that guides the planning of most health communications is whether to deliver messages to a general audience or whether to “segment” into target audiences. Audience segmentation is usually based on sociodemographic, cultural, and behavioural characteristics that may be associated with the intended behaviour change. For example, the National Cancer Institute's “five a day for better health” campaign developed specific messages aimed at Hispanic people, because national data indicate that they eat fewer fruits and vegetables and may have cultural reasons that discourage them from eating locally available produce.6

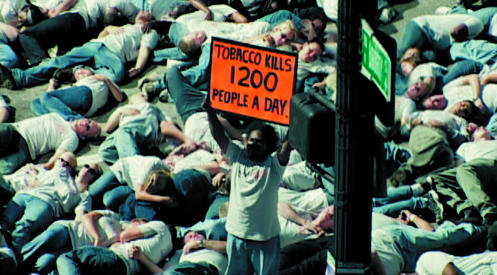

The broadest approach to audience segmentation is targeted communications, in which information about population groups is used to prepare messages that draw attention to a generic message but are targeted using a person's name (for example, marketing by mass mail). This form of segmentation is used commercially to aim products at specific customer profiles (for example, upper middle income women who have children and live in suburban areas). It has been used effectively in health promotion to develop socially desirable images and prevention messages (fig 2).

Fig 2.

Image used in the American Legacy Foundation's Truth antismoking campaign aimed at young people

“Tailored” communications are a more specific, individualised form of segmentation. Tailoring can generate highly customised messages on a large scale. Over the past 10-15 years, tailored health communications have been used widely for public health issues. Such communications have been defined as “any combination of information and behavior change strategies intended to reach one specific person, based on characteristics that are unique to that person, related to the outcome of interest, and derived from an individual assessment.”7 Because tailored materials consider specific cognitive and behavioural patterns as well as individual demographic characteristics, they are more precise than targeted materials but are more limited in population reach and may be more expensive to develop and implement.

Media trends and adapting commercial marketing

As digital sources of health information continue to proliferate, people with low income and low education will find it more difficult to access health information. This “digital divide” affects a large proportion of people in the United States and other Western nations. Thus, creating effective health messages and rapidly identifying and adapting them to appropriate audiences (which are themselves rapidly changing) is essential to achieving the Healthy People 2010 goal of reducing health disparity within the US population.8

In response, social marketers have adapted commercial marketing for health purposes. Social marketing now uses commercial marketing techniques—such as analysing target audiences, identifying the objectives of targeted behaviour changes, tailoring messages, and adapting strategies like branding—to promote the adoption and maintenance of health behaviours. Key trends include the recognition that messages on health behaviour vary along a continuum from prevention to promotion and maintenance, as reflected by theories such as the “transtheoretical model”9; the need for unified message strategies and methods of measuring reactions and outcomes10; and competition between health messages and messages that promote unhealthy behaviour from product marketers and others.11

Prevention versus promotion

Social marketing messages can aim to prevent risky health behaviour through education or the promotion of behavioural alternatives. Early anti-drug messages in the US sought to prevent, whereas the antismoking campaigns of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Legacy Foundation offered socially desirable lifestyle alternatives (be “cool” by not smoking).12,13 The challenge for social marketing is how best to compete against product advertisers with bigger budgets and more ways to reach consumers.

Competing for attention

Social marketing aimed at changing health behaviour encounters external and internal competition. Digital communications proffer countless unhealthy eating messages along with seductive lifestyle images associated with cigarette brands. Cable television, the web, and video games offer endless opportunities for comorbid behaviour. At the same time, product marketers add to the confusion by marketing “reduced risk” cigarettes or obscure benefits of foods (such as low salt content in foods high in saturated fat).

How is social marketing used to change health behaviour?

Social marketing uses behavioural, persuasion, and exposure theories to target changes in health risk behaviour. Social cognitive theory based on response consequences (of individual behaviour), observational learning, and behavioural modelling is widely used.14 Persuasion theory indicates that people must engage in message “elaboration” (developing favourable thoughts about a message's arguments) for long term persuasion to occur.3 Exposure theorists study how the intensity of and length of exposure to a message affects behaviour.10

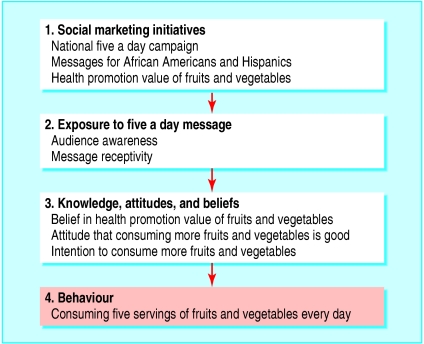

Social marketers use theory to identify behavioural determinants that can be modified. For example, social marketing aimed at obesity might use behavioural theory to identify connections between behavioural determinants of poor nutrition, such as eating habits within the family, availability of food with high calorie and low nutrient density (junk food) in the community, and the glamorisation of fast food in advertising. Social marketers use such factors to construct conceptual frameworks that model complex pathways from messages to changes in behaviour (fig 3).

Fig 3.

Example of social marketing conceptual framework

In applying theory based conceptual models, social marketers again use commercial marketing strategies based on the marketing mix.2 For example, they develop brands on the basis of health behaviour and lifestyles, as commercial marketers would with products. Targeted and tailored message strategies have been used in antismoking campaigns to build “brand equity”—a set of attributes that a consumer has for a product, service, or (in the case health campaigns) set of behaviours.13 Brands underlying the VERB campaign (which encourages young people to be physically active) and Truth campaigns were based on alternative healthy behaviours, marketed using socially appealing images that portrayed healthy lifestyles as preferable to junk food or fast food and cigarettes.14,15

Can social marketing change health behaviour?

The best evidence that social marketing is effective comes from studies of mass communication campaigns. The lessons learned from these campaigns can be applied to other modes of communication, such as communication mediated by healthcare providers and interpersonal communication (for example, mass nutrition messages can be used in interactions between doctors and patients).

Social marketing campaigns can change health behaviour and behavioural mediators, but the effects are often small.5 For example, antismoking campaigns, such as the American Legacy Foundation's Truth campaign, can reduce the number of people who start smoking and progress to established smoking.16 From 1999 to 2002, the prevalence of smoking in young people in the US decreased from 25.3% to 18%, and the Truth campaign was responsible for about 22% of that decrease.16

Summary points

Social marketing uses commercial marketing strategies such as audience segmentation and branding to change health behaviour

Social marketing is an effective way to change health behaviour in many areas of health risk

Doctors can reinforce these messages during their direct and indirect contact with patients

This is a small effect by clinical standards, but it shows that social marketing can have a big impact at the population level. For example, if the number of young people in the US was 40 million, 10.1 million would have smoked in 1999, and this would be reduced to 7.2 million by 2002. In this example, the Truth campaign would be responsible for nearly 640 000 young people not starting to smoke; this would result in millions of added life years and reductions in healthcare costs and other social costs.

In a study of 48 social marketing campaigns in the US based on the mass media, the average campaign accounted for about 9% of the favourable changes in health risk behaviour, but the results were variable.17 “Non-coercive” campaigns (those that simply delivered health information) accounted for about 5% of the observed variation.17

A study of 17 recent European health campaigns on a range of topics including promotion of testing for HIV, admissions for myocardial infarction, immunisations, and cancer screening also found small but positive effects.18 This study showed that behaviours that need to be changed once or only a few times are easier to promote than those that must be repeated and maintained over time.19 Some examples (such as breast feeding, taking vitamin A supplements, and switching to skimmed milk) have shown greater effect sizes, and they seem to have higher rates of success.19,20

Implications for healthcare practitioners

This brief overview indicates that social marketing practices can be useful in healthcare practice. Firstly, during social marketing campaigns, such as antismoking campaigns, practitioners should reinforce media messages through brief counselling. Secondly, practitioners can make a valuable contribution by providing another communication channel to reach the target audience. Finally, because practitioners are a trusted source of health information, their reinforcement of social marketing messages adds value beyond the effects of mass communication.

Contributors and sources: WDE's research focuses on behaviour change and public education intervention programmes designed to communicate science based information. He has published extensively on the influence of the media on health behaviour, including the effects of social marketing on changes in behaviour. This article arose from his presentation at and discussions after a recent conference on diet and communication.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Andreasen A. Marketing social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1995.

- 2.Borden N. The concept of the marketing mix. J Advertis Res 1964;4: 2-7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Communication and persuasion: central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986.

- 4.Backer TE, Rogers EM, Sonory P. Designing health communication campaigns: what works? Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992.

- 5.Hornik RC. Public health communication: evidence for behavior change. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2002.

- 6.National Cancer Institute. Making health communication programs work: a planner's guide. Bethesda, MD: NCI, 2002.

- 7.Kreuter M, Farrell D, Olevitch L, Brennan L. Tailored health messages: customizing communication with computer technology. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2000.

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: understanding and improving health. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2000.

- 9.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992. [PubMed]

- 10.PACT Agencies. PACT: positioning advertising copy testing. J Advertis 1982;11: 3-29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aaker D. Building strong brands. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

- 12.Hornik R, Yanovitsky I. Using theory to design evaluations of communication campaigns: the case of the national youth anti-drug media campaign. Commun Theory 2003;13: 204-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans D, Price S, Blahut S. Evaluating the truth™ brand. J Health Commun 2005;10: 181-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1986.

- 15.Huhman M, Heitzler C, Wong F. The VERB campaign logic model: a tool for planning and evaluation. Prev Chronic Dis 2004;1(3): A11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Haviland ML, Messeri P, Healton CG. Evidence of a dose-response relationship between “truth” antismoking ads and youth smoking. Am J Public Health 2005;95: 425-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snyder LB, Hamilton MA. Meta-analysis of U.S. health campaign effects on behavior: emphasize enforcement, exposure, and new information, and beware the secular trend. In: Hornik R, ed. Public health communication: evidence for behavior change. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 2002: 357-83.

- 18.Grilli R, Freemantle N, Minozzi S, Domenighetti G, Finer D. Mass media interventions: effects on health services utilization (Cochrane review). Cochrane Library. Issue 3. Oxford: Update Software, 2000: CD000389. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Snyder LB, Diop-Sidibé N, Badiane LA. Meta-analysis of the impact of family planning campaigns conducted by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs. Presented at the International Communication Association annual meeting, San Diego: May 2003.

- 20.Hornik RC. Public health education and communication as policy instruments for bringing about changes in behavior. In: Goldberg M, Fishbein M, Middlestadt S, eds. Social marketing. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1997: 45-60.