Abstract

Objective

To understand and develop a model about the meaning of coordination to consumers who experienced a transition from acute care to home care.

Study Design

A qualitative, exploratory study using Grounded Theory.

Data Sources/Analysis

Thirty-three consumers in the Calgary Regional Health Authority who had experienced the transition from an acute care hospital back into the community with home care support were interviewed. They were asked to describe their transition experience and what aspects of coordination were important to them. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using constant comparison. The coding and retrieval of information was facilitated by the computer software program Nud*ist.

Principal Findings

The resulting model has four components: (1) the meaning of coordination to consumers; (2) aspects of health care system support that are important for coordination; (3) elements that prepared consumers to return home; and (4) the components of a successful transition experience. Consumers appeared to play a crucial role in spanning organizational boundaries by participating in the coordination of their own care.

Conclusions

Consumers must be included in health care decisions as recipients of services and major players in the transition processes related to their care. Health care providers need to ensure that consumers are prepared to carry out their coordination role and managers need to foster a culture that values the consumer “voice” in organizational processes.

Keywords: Coordination, consumers, integrated delivery systems, system performance

The 17 Health Regions established in Alberta, Canada, in 1994, to replace more than two hundred individual boards, exhibit many features of integrated health care delivery systems. Horizontal integration has been accomplished by consolidating hospital services. Vertical integration is also apparent since each region has been required to merge the previously independent organizations responsible for public health, acute care, home care, and continuing care under a single board with a single administrative structure. Since it was anticipated that “the Regional Health Authorities Act will promote coordination and integration of health services” (Alberta Health 1994) this study was undertaken to investigate coordination from the perspective of an important stakeholder—the consumer.

A number of studies examine coordination from the perspective of providers and managers (Boland and Wilson 1994; Devers et al. 1994; Gilles et al. 1993; Young et al. 1998). In one study in which clients and families were consulted using a six statement “coordination scale” (Grusky and Tierny 1989), they were asked to rate the services they received and the activities of the agencies that served them. However, no previous studies sought to understand what consumers consider to be coordination.

In this study, consumers were asked to describe the coordination of their care in the transition from an acute care hospital back into the community with support from home care. Acute care and home care were examined because they provide care at different phases of the patient care continuum, an important aspect of vertical integration (Conrad 1993). The purpose of this study was to understand the meaning of coordination to consumers, to describe elements that contribute to a successful transition between hospital and home care, and to develop a model illustrating how the different elements relate to each other.

Method

An exploratory, qualitative design was selected because the intent of the study was to “make the phenomena (coordination) understandable, and to identify the perceptions of a particular group ” (Rundall et al. 1999). Qualitative methods were required because the variables were unknown; the context is important because there was no established theory on this topic (Creswell 1994). A grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss 1967) was used, which involves the systematic analysis of text to develop an inductively derived theory grounded in the data collected (Strauss and Corbin 1990).

Sample

The Calgary Regional Health Authority (CRHA) is one of two large urban health regions in the province of Alberta. The region provides primary and secondary care for citizens in the Calgary area (about 900,000 people), tertiary care for surrounding regions, and certain quaternary services for the entire province. Participants were drawn from the entire Calgary Health Region including all of the geographic home care areas (five urban and one rural) in the health region and all four full service adult hospitals. Interviews were conducted in 1996. Each of the five urban geographic home care areas was randomly selected to be the study area for one week. For the one rural-based home care team, data collection was continued for a month due to small numbers.

The Home Care Information System (HCIS) was used to recruit consumers from each designated home care team area. A letter was sent to consumers who had been discharged from an acute care hospital and were registered for short-term home care services. The HCIS list was used to compare the demographic characteristics and the diagnostic categories of consumers who agreed to be interviewed, with the total group of consumers in the home care area who were eligible for the study during the target time frame (usually one week).

Most consumers were interviewed within one month of their discharge from hospital. Subjects who did not wish to be interviewed in person were interviewed by telephone. Most personal interviews lasted somewhat longer than an hour (60–90 minutes); the telephone interviews were much shorter (5–10 minutes). With the permission of the interviewee, all personal interviews were recorded and later transcribed. The transcript of the interview was crucial for the data analysis process.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were obtained primarily through the in-depth personal interviews and a smaller number of short telephone interviews. An interview guide was used to initiate discussion. (See Appendix 1—Interview Guide). This did not pre-empt the open-ended nature of the interview, and there was ample opportunity for unstructured responses.

During the course of the interview, the researcher asked questions to verify her understanding of what the consumer was saying and made notes during and after the interview. These notes were included in the data analysis process. Questions about the transition experience evolved during the course of the study, as is often the case in qualitative research (Creswell 1994). For example, as categories began to emerge from the initial interviews relating to preparation for returning home, subsequent participants were asked about these categories.

Data analysis began with reviewing the transcripts of the interviews to identify common thoughts, themes, and ideas. Portions of the interview were labelled with a code, which is a word or phrase that captured the idea in the text. Some codes were words or phrases taken directly from the interview, while others were chosen by the researcher to represent the idea or concept in the text. The codes were grouped into major headings (categories) and subheadings (properties). The constant comparison method (Creswell 1998) was used, with codes and headings continually refined and enriched as new sections of text were examined and added or new codes were created. The Nud*ist (Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing Searching and Theorizing) software program was used as a convenient way of managing and beginning to analyze the data. Coding and grouping the data is the first step in data interpretation. The next step in theory development is examining and forming hypotheses about the relationships between concepts (Strauss and Corbin 1990). The relationships may be expressed as hypotheses, or presented in a diagram as a model, which is how the theory is presented in this paper.

Maintaining Research Quality

To assess the neutrality (objectivity) and dependability (reliability) (Devers 1999) of the data, other researchers reviewed and coded some interviews. Five interviews were reviewed by the co-investigator. In addition, sections of interviews were coded and discussed with two groups of graduate student researchers (20 graduate students in one group and 6 in the other). Two experienced qualitative researchers, not associated with the project, each reviewed and coded a complete interview as “skeptical peers.” To triangulate the information that was emerging from the data collection and coding process, the preliminary categories were discussed with a group of 20 home care coordinators and managers who work closely with the consumer group.

To determine the credibility (validity) of the findings, a one-page summary of the consumer's view of coordination was mailed to a purposive sample of 12 participants who had been interviewed in the study. Eight subjects were interviewed by telephone for about 15 minutes regarding the summary. All of the participants who were interviewed agreed with the summary. One consumer expressed his support in the following way: “It captured the things that were important about my experience and I can't think of anything to change about my care or the summary.” The research proposal was reviewed and approved by the Research and Development Committee at Calgary Health Services and the Conjoint Medical Ethics Review Board at the University of Calgary.

Findings

Participants

Of the 64 potential participants, 10 consumers declined to be interviewed and 21 were not included in the study for the following reasons: an initial contact letter from Home Care was not sent (7); they could not be reached by telephone to set up an interview (4); they did not receive any home care services (2); or they could not be interviewed (8) (poor health [2], psychiatric problems [2], limited English [4]). Of the 33 consumers who took part in the study, 26 were interviewed in person and 7 by telephone.

Slightly more than half of the consumers (59 percent) were female. The mean age of participants was 65 years (range 21–89 years) with the following age distribution: 20–39 years (15 percent), 40–59 years (15 percent), 60–79 years (50 percent), 80 years+ (20 percent). Two-thirds of participants lived with a family member, one-third lived alone, and half of the group were retired. There were no major differences in the sex and age distribution of the residents in each geographic area of the health region. The majority of respondents in the personal interviews reported their nationality as Canadian (20/26). Six other nationalities were self-reported with one respondent in each of the following categories: American, British, “African” (country not specified), Dutch, Lebanese, and Pakistani. Information was not available on the nationality of nonrespondents or those interviewed by telephone. The majority of home care consumers received nursing care (20/33), which most commonly was nursing support for a home I.V. (9/20); 6/33 consumers had occupational, respiratory, or physiotherapy. Four diagnostic categories accounted for about 70 percent of the consumers in the study: musculoskeletal (30 percent), circulatory (20 percent), digestive (10 percent), and injury (10 percent).

In most respects the characteristics of the participants in the study were similar to the sample frame of consumers who were eligible for the study. The exception was the diagnostic code indicating a nervous system or mental disorder. In the group of consumers who were not interviewed, four consumers had this diagnostic code, whereas no consumers had this diagnostic code among those who were interviewed.

The Meaning of Coordination to Consumers

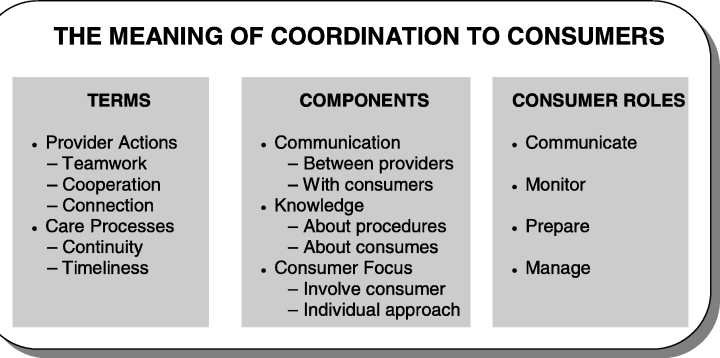

Three aspects to the meaning of coordination emerged from the interviews: “Terms,”“Components,” and “Consumer Roles.” They are presented in Figure 1. “Terms” are single words synonymous with coordination that could be clustered into two groups: (a) terms that referred to coordination between providers, including cooperation, teamwork, and connection; and (b) terms related to the processes of care including continuity and timeliness. The two other aspects of coordination, “Components” and “Consumer Roles,” are discussed below.

Figure 1.

Coordination—Three aspects to the meaning of coordination: Terms, Components, and Consumer Roles

Components of Coordination

Three components of coordination were identified: communication, knowledge, and consumer focus. The most consistent component was communication. One consumer defined this as: “Communication, knowing what the plan is and following it through.” Two types of communication emerged as important. One was communication between health care providers: “I go and see my Doctor here, (Dr. H.) and Dr. C. gets all the dope on it. The communication is fantastic.”

The second aspect was communication between health care providers and the consumer: “I hadn't been home but a short time when the first call came. The communication was the big thing.” The importance of communication was also identified by consumers who identified problems: “It turned out to be a big fiasco…It was just a lack of communication, lack of people knowing what to do.”

The second component of coordination was knowledge. There was an expectation that staff members at all sites in the system would be informed about procedures or services that consumers needed. A patient who had a midline I.V. inserted to allow her to receive intravenous antibiotics at home had problems with the I.V. When she went to the emergency room of the hospital (where she had been told to go), the staff there did not seem to know how to handle the problem and eventually just removed the I.V.

The basic [problem] was just the fact that people weren't knowledgeable in the actual home I.V. program. If they're going to go ahead with the program, maybe they should make sure there's people that are trained. (Female, Age 35)

The other aspect was knowledge about the individual consumer. One consumer had a severely injured arm as a result of a car accident in another province. He observed:

I could tell the difference in the hospital nurses, in the OT and physiotherapy people, as to whether or not they had actually bothered to read my chart or had seen my X-rays… It's one thing to say “You've got a broken arm.” There's another thing to see my X-rays with all the little wee bone chunks and 20 screws and 2 metal plates… The key point here being that my left arm was shattered, not broken, shattered. (Male, Age 39)

Consumer focus as a component of coordination meant involving consumers in what was going on:

INTERVIEWER: Now, any pointers or any comments about what kinds of things that you think are important about coordination for people who are in hospital and coming home?

CONSUMER: I think if they do everything the same way as they did to me. They involved me more and I knew more about everything than I expected to . I think that's about as much as they can do. (Male, Age 21)

Another aspect of consumer focus was the need for an individualized approach. This was expressed by the following consumer who indicated her transition between hospital and home went well because Home Care had “recognized her special needs.” In the hospital, however, she felt the staff did not understand her individual health needs. “There were set timetables for this, or for that, or for the other thing but nobody was paying attention to me that I might not fit into their timetables.”

Consumer Roles

A very dramatic finding that emerged from the interviews was the importance of consumers in coordinating their own care. This came up in more than half (17) of the 26 personal interviews. It was a factor for men and women and for all age groups. This consumer involvement may include a variety of actions that have been classified as consumer roles: communicate, monitor, prepare, and manage. These roles are illustrated below.

Communicate

In the following example, the home care nurses would call the patient to ask how often her doctor wanted her dressings changed. The nurses would then alter the schedule of home visits accordingly.

CONSUMER: When he changed it [the number times the dressing should be changed] from twice a day to once a day, the nurse…that usually comes in, phoned me that afternoon after I'd been to the doctor and asked me what…what, you know, he said. She changed it [her home visits] down to once a day.

INTERVIEWER: So the nurse basically arranged her visits through you? CONSUMER: Yes. Through me. (Female, Age 50)

Monitor

Other consumers indicated it was up to them to carry through with their therapy and keep track of how they were doing.

She checked my exercises. I'm just carrying on with the exercises the nurse in the hospital gave me. And I keep a chart for myself to see if I'm going up or going down or what I'm doing. (Female, Age 82)

Prepare

Consumers would seek information from their own sources about what to expect before going into hospital or coming home.

I did quite a bit myself before I went into hospital. I phoned people that had been in the hospital or had been in surgery and I asked them what I was supposed to take. And another thing is that I asked them everything that I could about what, like after care or things like that. And they told me. (Female, Age 79)

Manage

The management role of the consumer was evident with a consumer who was very involved in adapting his environment both in the hospital and at home, to allow him to manage with severe injuries to one side of his body.

I've basically kind of fixed up most of it myself. I think what it comes down to is who's the coordinator? The coordinator seems to be me, the customer. (Male, Age 39)

The extreme example of the manager role was an ex-Navy man who was very def-inite that to make things happen in health care, either in the hospital or at home or in the transition between the two, people had to take charge themselves.

INTERVIEWER: What would you tell your buddy about the experience of being in hospital and coming home?

CONSUMER: Don't leave it to them. Take your situation in your own hands. You have to take your situation in your own hands. (Male, Age 76)

The consumers in the above excerpts played a number of active roles, including some who actually managed the coordination process. However, as the following respondent pointed out, not all consumers are able to take on an active role unless they have some assistance.

CONSUMER: He didn't bother because he was more concerned about just getting me out of there. So I could coordinate whatever, but he just didn't understand that it wasn't that easy. Especially for me being blind.

INTERVIEWER: So what kinds of things do you think are important about the coordination of services for people who leave hospital and require care at home, from your experience?

CONSUMER: I think there needs to be teamwork, effective and clear team work, like, what am I trying to say. The doctors or nurses, well probably the doctors, should know what the resources are, even within the hospital, even if all they know is to call social work. They should know what the other options are instead of just handing it over to the patient because sometimes we don't know. (Female, Age 23)

The Transition Experience

Participants were asked whether they preferred to be in the hospital or at home. All consumers except one (25 of 26 personal interviews) preferred to be at home. This was usually expressed as a very strong preference: “I desperately wanted to get out of hospital and come home so they [home care nurses] fulfilled that need for me.” Only one consumer expressed a slight preference for the hospital. He needed a walker to move around and liked the hospital because the floors did not have carpet.

Most consumers indicated the timing of their discharge from the hospital was about right. This was often part of a positive, coordinated, successful transition experience: “The transition was good and the staff both ways have been amazing.”

The following quote illustrates the interplay between timing and site preference. When this consumer was ready to leave the hospital, his preference was to be at home.

CONSUMER: The doctor, would have liked me to be discharged. I had to apply pressure to stay a couple of days longer than they would have liked. We were ready, when I was discharged, (two days later) we were in complete agreement with the time and felt that was the right time. (Male, Age 76)

The consumer characterized his eventual transition from the hospital to home as “a very positive experience” because he and his wife “were ready for it.”

Two other consumers wanted to stay in the hospital longer but were not successful in delaying their discharge from the hospital. One consumer was a 77-year-old woman from Pakistan, the other a 59-year-old man from Africa.

Preparation for Returning Home

Most consumers indicated they felt prepared to come home. This preparation was manifested in a number of ways including knowing what to expect when they were discharged and having the necessary training and information (such as written instructions) to manage at home. Consumers who were prepared to go home often received information more than once and in a variety of formats.

Part of being prepared was knowing what to expect at discharge. The following consumer indicated he knew what to expect about his medical condition when he returned home because he had been involved in the decision to proceed with his surgery: “They explained it to me on several occasions, not just once.”

A second aspect of preparation was information. This included training consumers to manage the equipment or therapy they would need at home. “Oh, yes, I was prepared because I had been down (to the physiotherapy department) and I had instructions.”

Written instructions were an important and recurrent theme identified by consumers who indicated they were prepared to come home. Instructions were provided for various stages of the care process but were particularly important at transition points, such as prior to hospitalization and the day of discharge.

Consumers who felt prepared to go home had often received information more than once in a variety of formats, had been given guidance about how to handle anticipated problems, and had a phone number to call as a backup: “They gave me a complete folder of everything—what to do if this happens, if this happens, if this happens. And if none of that worked then I was to call immediately.”

System Support for Coordination

While responding to questions about the nature of coordination, consumers identified a number of aspects of the health care system that were important to coordination. Some of these were specific services, others involved health care providers working across organizational sectors and lastly, the concept of attending to the consumer's voice emerged.

Specific services included: (a) regular phone calls by home care personnel to the consumer and a phone number consumers could call if they had problems; (b) health care staff having the time and training to provide services that consumers felt they needed; (c) providing written instructions; and (d) keeping the chart in the consumer's home.

The concept of service providers crossing sectors emerged in consumers' comments explaining why they felt their care was coordinated. The most frequently mentioned example was providers from one sector (the home care coordinator) going to another sector (the hospital) to see the consumer.

The coordination started with the Home Care people at the hospital coming to my room, showing me how to use the pump, how it was going to be handled, what they were going to do and then giving me all the information on the Home Care people who would be coming [to his home]. (Male, Age 51)

In the next example, in addition to going to the hospital, the home care nurse also obtained help from hospital personnel to assist with the inserting a midline I.V.

INTERVIEWER: Did you feel there was coordination between the hospital and Home Care?

CONSUMER: Yes ….Actually she [the home care nurse] put it in and then the nurse at the hospital just assisted her… Even there, both the Home Care nurse and the hospital nurse were working together. (Male, Age 21)

Another activity that signalled coordination for the same consumer was the nurse from one sector (home care) facilitating access for the consumer to services in another sector.

My foot was still quite swollen. They were concerned that maybe the specialist, Dr. L., would want to keep the I.V. in longer. She [the home care nurse] phoned Dr. L. up and made an appointment for me to go in to see him. (Male, Age 21)

If there is going to be consumer involvement in coordination, however, the organizational environment and health care providers need to allow and encourage this involvement:

I just know those resources are there. I was going to mention it but he wasn't listening to me anyway so it didn't seem to matter if I said it or not. (Female, Age 23)

This excerpt suggests that for consumers to assume a role in coordination, they need an organizational “voice,” that is, they need to feel that health care providers are listening to them.

The Successful Transition

A successful transition was defined as the consumer being able to function well once they returned home. Support and confidence were the two variables that emerged as important to both the transition process and to the consumers functioning well in their home environment after the transition.

Support

As the study progressed, and support began to emerge as an important variable, the interview guide was modified to ask consumers if they felt they had support at home and to explore what contributed to a feeling of support. Consumers identified a number of sources of support including: family members—“Because all my three children are here. And all of them are dedicated kids” the community—“and I've got good neighbours. My neighbour next door comes in almost every day” and the health care system. Excerpts from the following interview illustrate a number of aspects of health care system support. The appropriate care was available but only services that were needed were provided.

CONSUMER: I needed 24-hour care when I went back into the hospital.

INTERVIEWER: You mentioned you don't seem to need the care 24 hours a day now.

CONSUMER: I need somebody that knows what they're doing to come in. … I think the level of care at home is as good as it is in the hospital. The only difference is that it's not 24 hours. It's there and it is available but it's not something that's kicked in automatically…To me, that works great because it's not wasted. (Female, Age 50)

Telephone contact was another important source of system support identified by many consumers.

I had all these phone numbers. And I phoned back, I phoned to the Home Care nurse, actually. And she gave me everything she could think of to do. Then she said, well, I'll give you two more things to do and if neither of these work then you'll probably have to come back up here and I'll look at it. (Male, Age 21)

Confidence

One of the aspects of the transition process that was examined was whether the consumer felt confident about the transition and what contributed to confidence. Confidence seemed to be related to system support and preparation.

INTERVIEWER: You were saying you felt pretty confident managing things at home. You had the written stuff, and they'd gone over it with you, and they'd taken X-rays.

CONSUMER: Yes. The Home Care Nurse was really helpful too. She checked my toe each time she came and made sure it looked like it was getting better. (Male, Age 28)

CONSUMER: I was looking forward to it [going home] and I was very confident. It was the right thing—that day. But I didn't before.

INTERVIEWER: What helped you to be ready do you think?

CONSUMER: My condition. Because I had done a considerable amount of walking and exercise, which prepared me for it. (Male, Age 76)

For one consumer, control related to the timing of his discharge from hospital was a significant issue. However, control did not emerge as a major issue for other respondents.

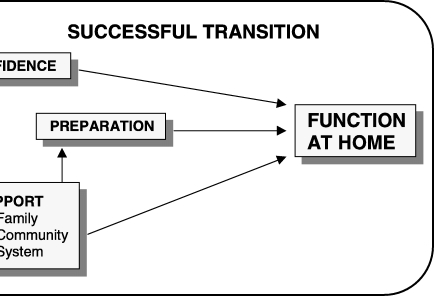

Figure 2 is a diagram of the relationships that appear to contribute to a successful transition (defined as the consumer being able to function well at home).

Figure 2.

Transition—Confidence is affected by preparation and support; support enhances confidence and preparation; confidence, preparation, and support contribute to a successful transition. Support and preparation appear to be imporatant to functioning at home directly, and as factor influencing confidence

Discussion

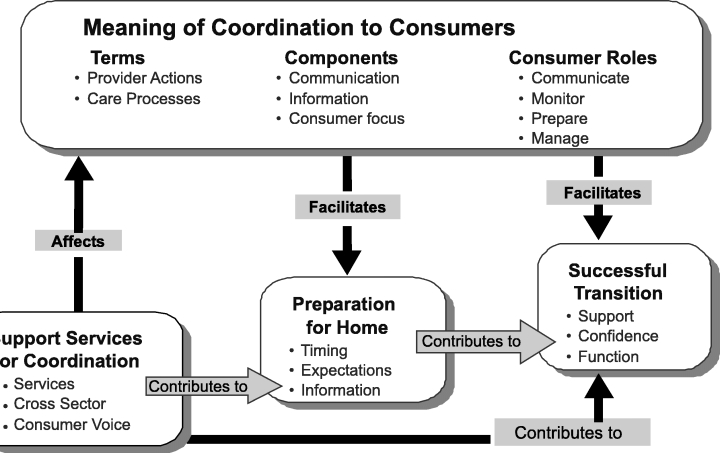

The Model

Figure 3 is a model of the hypothesised relationships among the findings. The first part of the model describes what coordination means to consumers, and is presented as terms, components, and the consumer role in coordination. A consistent and dominant theme is consumer involvement in the consumer's own care. This involvement begins to emerge in the “components” that consumers identify as important to coordination, particularly “communication with the consumer” and “consumer focus.” Consumer involvement is also the foundation of the consumer roles that were identified: communicate, monitor, prepare, and manage.

Figure 3.

The Model Understanding Coordination

Next the model identifies why coordination is important. This is related to the information that emerged about the transition experience. It is proposed that coordination is related to a successful transition for the consumer from hospital to home in two ways: (1) directly by facilitating a successful transition, and (2) indirectly by facilitating preparation for the consumer to return home.

Another aspect of the model identifies the elements of the health care system that support coordination and facilitate preparation for the consumer to return home as well as contribute to a successful transition.

The majority of consumers who were interviewed indicated their care had been coordinated and gave examples of coordination, which provided internal validation for the definitions of coordination that emerged initially. For those who did not have a positive transition experience, there was also internal consistency between how they defined coordination and what they expected (but did not experience) in their health care. The definitions of coordination and expectations were similar in the reports among consumers with a positive transition experience, and those with a negative experience.

With the intense financial pressures that most health care organizations face, there is often pressure to minimize the number of days that a patient will be in the hospital. There is often an implicit assumption that patients want to stay in the hospital. In this study all consumers, except one, preferred to be at home. Although most consumers agreed with the timing for leaving the hospital, the two consumers who felt they were discharged from the hospital too soon were from cultures outside North America (Africa and Pakistan). Therefore health care providers may need to spend more time with consumers from other ethnic backgrounds to clarify the expectations (of both the consumers and the providers) and to provide additional support to assist the consumer with the transition.

Preparation to return home after hospitalization is part of a continuum of care that begins with consumer involvement in decisions about the treatment that requires hospitalization, such as surgery. Preparation continues with training (while the consumer is in hospital) about procedures that will be required at home. Consumers indicated that good preparation was proactive; it provided information about possible common problems and their solutions. Written instruction at different phases of the continuum of care was a powerful tool that empowered consumers. Repetition in conveying information in a variety of formats was perceived as effective preparation. The system support that emerged most often as important to coordination was the visit by the home care nurse while the consumer was still in the hospital. These findings provide important data on how to manage boundaries between sectors from the consumer's perspective, that is, provide information for the consumer in a variety of formats before the transition occurs. This is consistent with the finding that to “smooth transitions,” it was valuable to connect clients with outpatient services before discharge from hospital (Ware et al. 1999).

The findings about coordination, consumer preparation for returning home, health care services, and a successful transition experience that are presented in the model in Figure 3 were interrelated: A successful transition occurred as the culmination of activities if all of the other elements were in place.

Implications

The Consumer Role

Patient satisfaction with clinical care is now a focal concern of quality assurance and an expected outcome of care (Ford et al. 1997). However, the present study has demonstrated that in addition to assessing the outcomes of care, consumers can and should be involved in the processes of delivering that care, particularly in a vertically integrated system where coordination between sectors is a goal of the system. The recent Institute of Medicine report on “Crossing the Quality Chasm” (2000) identifies six major challenges to introducing the organizational changes needed for a new health system for the twenty-first century. One of these organizational challenges is “coordination of care across patient conditions, services, and settings over time.” This study suggests that supporting active consumer participation in coordinating their own care is one mechanism to accomplish the boundary spanning necessary to link services across settings and organizational sectors.

The findings from this study support the observation that “the public is moving beyond the patient role into a more egalitarian partnership role with professionals in the treatment process” (Siler-Wells 1988). The concept of “patients as partners” (Holman and Loring 2000) is particularly striking in the literature relating to self-care for patients with chronic disease. One aspect of the collaborative management of chronic illness described by Von Korff et al. (1997) is patient access to services that teach skills needed to carry out medical regimens and guide health behaviors, with ongoing health system support. In the Chronic Care Model described by Wagner et al. (1999) community resources and the organization of the health care system provide a backdrop for “productive interactions” between an “informed, activated patient” and a “prepared, proactive practice team.” Similar to the present study, Wagner identifies that “patients must have the information and confidence to make best use of their involvement with their practice team.” In the Wagner model, it is the health care team who must be prepared, and “preparation means having the necessary expertise, information, time, and resources.” In our study, provider expertise and resources were identified as important components of health system support. Preparation, however, emerged as important for consumers, with information identified as one of three significant components.

Health Care Providers and Managers

An organizational role for consumers also has implications for health care providers and managers. Mills and Moberg (1982) identify a number of differences in processes and outcomes between organizations that manufacture goods and those that produce services. A major difference in service organizations, such as those that provide health services, is that the customer and the service provider must interact. As well as providing the information that constitutes the “raw material” for the interaction, service organizations also often make use of clients' efforts in actually producing the service. For example, the customer fills out a deposit slip in the bank, or patients carry their X-rays from one department to another in a hospital. However, consumers may have less knowledge than they require to carry out the necessary tasks. Thus they may need to be co-opted, or drawn into organizational membership roles, so they can acquire the necessary information and use it responsibly. For consumers to participate effectively as partners, they need support from providers. This adds to the role of the provider since, in addition to providing clinical care, providers also need to serve as coaches or teachers for consumers.

This is particularly important for consumers with special challenges. In dealing with patients with cognitive impairment Reimer (1997) found that the ability of the patient to participate in discussions about their care was affected by the nature and degree of the impairment that was present and that questions needed to be more specific and concrete. For those from other cultures, in addition to translation services, system supports might need to include access to someone with “cultural competence” (Campinha-Bacote 1991) who understands the cultural context of health and illness for the consumer to allow the consumer “voice” to be expressed and heard.

Kaluzny and Shortell (2000) predict a major change for health care managers from managing an organization to managing a network of services and managing across boundaries. Managing boundaries between organizations, or sectors within an organization, and managing the transition processes across these boundaries for those who use the system are critical for developing an integrated system. One mechanism to help manage boundaries is to draw on the consumer as a temporary organizational member. In planning and evaluating health system performance, managers should solicit consumers' views about organizational processes, particularly those that cross boundaries. To accomplish this, managers need to foster an organizational culture that values and respects consumer input.

Health System Performance

To assess system performance, the emphasis needs to be on actual system attributes. “It is important to recognize that system performance at any given level may not be analyzable as a simple aggregation of system performance at lower levels. This is one of the principal features of any system, its performance is determined as much, if not more, by the arrangement of its parts—their relations and interactions—as by the performance of the individual components” (Flood 2000, p. 364).

Evaluating health systems requires measures that emphasize interdependencies and common goals and that assess the contribution of the various operating units to the “system.” The importance of evaluation goes beyond assessing performance, since it is argued that the development, collection, and feedback of system-wide indicators can foster the development of “systems thinking” (Devers et al. 1994). The present study contributes to understanding an important unifying element in any health system (coordination) and provides a foundation of knowledge that will allow the assessment of coordination by an important stakeholder in the health care system (the consumer).

Young et al. (1998), in their investigation of patterns of coordination in surgical services, conclude that high levels of both programming (e.g., policies, procedures) and feedback (personal one-on-one discussion and group modes) produce better clinical outcomes. Alter and Hage (1993) suggest the difficulties in predicting outcomes in human services make it difficult to standardize interventions and processes, which is one coordination mechanism. In this study, consumers who expressed dissatisfaction with the coordination of their care indicated that providers had not recognized their unique needs. This finding supports the view that standardized activities alone have limited application for achieving coordination in a service industry such as health care. Since it is difficult to coordinate activities by standardized processes, consumers need to be involved in tailoring the activities to meet their own needs. Thus, the consumer becomes an integral part of the organizational system, central to integrating, enabling, or assisting the production of services and the level of quality desired by the consumer (Mills and Moberg 1982).

Organizational stakeholders often value dimensions of performance differently (Sicotte et al. 1998). Thus, for a comprehensive assessment, a multiple stakeholder approach to effectiveness is warranted. Since consumers are the stakeholders who experience the entire episode of an illness, they are ideally positioned to participate in, and to evaluate, the continuum of care. The findings from the present study suggest that in addition to asking consumers about the quality of clinical processes, they should also be asked about organizational processes, especially those processes that relate to managing the boundaries between sectors, which is a potential problem in a vertically integrated health care system.

Kaplan and Norton (1992) developed a balanced scorecard approach for assessing organizational performance that included four perspectives: financial measures, customers, internal business processes, and learning and growth. Leggat and Leatt (1997) added the concept of “Community Benefit” to the Kaplan and Norton model. However, the health care system is only one of the players in the organizational environment that affects the health of the population. One of the future challenges for assessing health system performance will be to study the interface between the health care system and the other determinants of health. The findings from this study suggest consumers of services might be able to participate in managing the boundaries and assessing the linkages between the health care system and the other systems that affect the health of individuals and communities.

Strengths/Limitations/Future Research

A strength of the study was the validity of the findings. There was convergence in the descriptions of coordination from consumers with different experiences and consistency within each interview. A major finding from the study, the role of the consumer in coordinating care, was unanticipated, which demonstrates the importance of a qualitative approach as a first step in investigating previously unstudied phenomena in their social context.

A limitation of the study was that the consumer needed to be able to be interviewed to be included, thus creating sampling bias and limiting the applicability of the study for those who cannot speak English or who are cognitively impaired. Another potential limitation with qualitative research is researcher bias. The steps taken to minimize this are outlined in the section on “maintaining research quality.”

Response bias regarding personal versus telephone interviews may also be a limitation. Because the personal interviews were longer (60–90 minutes), the findings include more information from the personal interviews, although there was no information in the telephone interviews that contradicted the findings in the personal interviews. The phone interviews were much shorter (5–10 minutes), with proportionately more women, and respondents older then 80 years of age. In addition, telephone participants had received fewer home care services. Therefore the major finding regarding the significant role that consumers play in coordinating their own care may be more reflective of men younger than 80 years of age who receive more home care services. This patient involvement may be more important for those with chronic conditions (necessitating more ongoing involvement with the health care system). Conversely, those with episodic care might be less concerned with (and therefore less willing to be interviewed about) the coordination of care.

The lack of generalizability of qualitative research is often regarded as a limitation of the design. Therefore, considerable detail has been included about the participants to allow other researchers to determine how generalizable this study is to their own research (Miles and Huberman 1994). Future research is needed to determine if the findings are generalizable to short-term home care clients outside Calgary and to other groups of home care clients.

Zapa et al. (1995) have reported a strong association between problems in system performance and dissatisfaction with care. Assessing the organizational role of the consumer and examining if this is related to other outcome measures, such as health status or satisfaction with care, would be another compelling area of investigation. Further research is also needed to understand more about the extent of consumer involvement, that is, are there some circumstances in which there could be “too much” consumer involvement?

Conclusion

The findings from this study have implications for health services theory—the development of a model about the meaning of coordination; health care practice—the role of health care consumers, providers and managers; and health services evaluation—assessing the performance of an integrated health care delivery system with guidance about how to assess coordination (an attribute of the system), from the perspective of the consumer (a key stakeholder).

Appendix 1

Interview Guide

November 1996

The Consumer's View Of Coordination

Interviewer A. Harrison

NAME OF RESPONDENT -----------------------

ADDRESS ------------------------------

TELEPHONE NUMBER ------------------------

INTERVIEW: DATE --------- TIME INTERVAL -----------

REGISTRATION DATE WITH HOME CARE ---------------

Introduction

There have been many changes in the way health services are organized in the province of Alberta and the City of Calgary. One of the reasons for making changes is to improve the coordination between various parts of the Health Care system. The purpose of our interview today is to learn what you as a consumer think is important about the coordination of the services you received in the hospital and the services you are now receiving from Home Care.

1. Description of Personal Experience

Can you tell me about your experience: A) Leaving hospital B) Arriving home

2. The Transition from Hospital to Home

Description– Would you describe your transition from the hospital to your home as positive or negative?

Preference– Would you prefer to be in hospital or at home?

-

Timing– From your perspective was the time right for you to come home?

Would you like to have come home a) sooner, b) when you did, or c) stayed in hospital longer?

Healing– Do you think you will get better faster a) at home or b) in the hospital or c) at about the same rate?

Preparation– Did you feel ready to come home?

Support– Did you have enough support to go home a) from the health care system b) from your family or friends?

-

Confidence– Did you feel confident about going home?

Why did you answer Yes or No?

-

Function– Were you able to function reasonably well at home?

What helped you manage at home?

Control– Did you feel in control of things when you were getting ready to go home and when you got home?

Finances– Were there any financial implications for you in leaving the hospital and receiving care in your home?

Changes– Are you aware of any recent changes in health care? Do you think these changes have had, or will have, an effect on your own health care?

3. Coordination

What does coordination mean to you?

What does coordination in health care mean to you?

Did you think there was coordination between the health care services you received in hospital and the care you are now receiving in your home? Could you give me some examples of why you answered (yes or no) to this question.

Were there gaps between the services provided in hospital and the services provided at home?

Are some of the services provided at home duplicating or repeating the services you had in hospital?

What do you think is important about the coordination of services for people who leave hospital but require care in their home?

Any other comments about your experience?

The Consumer's View of Coordination

Researcher A. Harrison

Information about the consumer who participated in the interview

Introduction

I would like to include some information about who you are. This information is not intended to identify you personally, but rather to provide background about the people who participated in the study. All information about you as an individual will be kept strictly confidential. We can skip any questions that you would rather not answer or add anything which you think should be included.

AGE OF RESPONDENT ________________________

MALE OR FEMALE ________________________

OCCUPATION ________________________

ETHNIC GROUP ________________________

REFERRING HOSPITAL ________________________

REASON FOR HOSPITAL STAY ________________________

LENGTH OF TIME IN HOSPITAL ________________________

REASON FOR HOME CARE ________________________

TYPE OF HOME CARE SERVICES ________________________

FREQUENCY OF HOME CARE SERVICES ________________________

DURATION OF HOME CARE SERVICES ________________________-

GENERAL HEALTH ________________________

LIVING ARRANGEMENTS ________________________

(e.g. living alone, with a partner, with another family member)

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION (From Consumer or Interviewer)

__________________________________________________

References

- Alberta Health. Regional Health Authorities User's Guide. Edmonton: Alberta Health; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Alter CJ, Hage . Organizations Working Together. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bolland J, Wilson J. “Three Faces of Coordination: A Model of Interorganizational Relations in Community-based Health and Human Services”. Health Services Research. 1994;29(3):341–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J. The Process of Cultural Competence: A Culturally Competent Model of Care. Wyoming, OH: Transcultural C.A.R.E. Associates; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad DA. “Coordinating Patient Care Services in Regional Health Systems: The Challenge of Clinical Integration”. Hospital and Health Services Administration. 1993;38(4):491–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. Research Design, Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Devers K. “How Will We Know Good Qualitative Research When We See It”. Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1153–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devers K, Shortell S, Gilles R, Anderson D, Mitchell J, Erickson K. “Implementing Organized Delivery Systems: An Integration Scorecard”. Health Care Management Review. 1994;19(3):7–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood A, Zinn J, Shortell S, Scott R. “Organizational Performance: Managing for Efficiency and Effectiveness”. In: Shortell SM, Kaluzny AD, editors. Health Care Management: Organization Design and Behavior. 4th ed. Albany, NY: Delmar Thomson Learning; 2000. pp. 356–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ford RC, Bach S, Flotter M. “Methods of Measuring Patient Satisfaction in Health Care Organizations”. Health Care Management Review. 1997;22(2):74–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles R, Shortell S, Anderson D, Mitchell J, Morgan K. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Integration: Findings from the Health Systems Integration Study”. Hospital and Health Services Administration. 1993;38(4):467–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Grusky O, Tierney K. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Countywide Mental Health Systems”. Community Mental Health Journal. 1989;25(1):3–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00752439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman H, Loring K. “Patients as Partners in Managing Chronic Disease”. British Medical Journal. 2000;320(26 February):526–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. The National Academy Press; 2000. “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century”. http://www.nap.edu/books/0309072808/html/ [Google Scholar]

- Kaluzny A, Shortell S. “Creating and Managing the Future”. In: Shortell SM, Kaluzny AD, editors. Health Care Management: Organization Design and Behavior. 4th ed. Albany, NY: Delmar Thomson Learning; 2000. pp. 392–404. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan RS, Norton DP. “The Balanced Scorecard—Measures that Drive Performance”. [January-February];Harvard Business Review. 1992 :71–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggat S, Leatt P. “A Framework for Assessing the Performance of Integrated Delivery Systems”. Health Care Management Forum. 1997;10(1):11–8. doi: 10.1016/S0840-4704(10)61148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mills P, Moberg D. “Perspectives on the Technology of Service Operations”. Academy of Management Review. 1982;7:467–78. [Google Scholar]

- Reimer M. Measurement of Quality of Life in Adult Onset Cognitive Impairment. 1997. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Calgary. [Google Scholar]

- Rundall T, Devers K, Sofaer S. “Overview of the Special Issue”. Health Services Research. 1999;34(5 Pt 2):1091–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sicotte C, Champagne F, Contandriopoulos A, Barnsley J, Béland F, Leggat S, Denis J, Bilodeau H, Langley A, Bremond M, Baker R. “A Conceptual Framework for Analysis of Health Care Organizations' Performance”. Health Services Management Research. 1998;11(1):24–41. doi: 10.1177/095148489801100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siler-Wells GL. Directing Change and Changing Direction: A New Health Policy Agenda for Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry S, Wagner E. “Collaborative Management of Chronic Illness”. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127(2):1087–102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E, Davis C, Schaefer J, Von Korff M. “A Survey of Leading Chronic Disease Management Programs: Are they Consistent with the Literature”. Managed Care Quarterly. 1999;7(3):56–66. http://www.centerforhealthstudies.org/maclist.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware N, Tugenberg T, Dickey B, McHorney C. “An Ethnographic Study of the Meaning of Continuity of Care in Mental Health Services”. Psychiatry Services. 1999;50(March):395–400. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young GJ, Charns MP, Desai K, Khuri SF, Forbes MG, Henderson W, Daley JJ. “Patterns of Coordination and Clinical Outcomes: A Study of Surgical Services”. Health Services Research. 1998;33(5 Pt 1):1211–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapka J, Palmer R, Hargraves J, Nerenz J, Frazier H, Warner C. “Relationships of Patient Satisfaction with Experience of System Performance and Health Status”. Journal of Ambulatory Care Medicine. 1995;18(1):73–83. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]