Abstract

Objective

To develop an instrument to characterize public sector managed behavioral health care arrangements to capture key differences between managed and “unmanaged” care and among managed care arrangements.

Study Design

The instrument was developed by a multi-institutional group of collaborators with participation of an expert panel. Included are six domains predicted to have an impact on access, service utilization, costs, and quality. The domains are: characteristics of the managed care plan, enrolled population, benefit design, payment and risk arrangements, composition of provider networks, and accountability. Data are collected at three levels: managed care organization, subcontractor, and network of service providers.

Data Collection Methods

Data are collected through contract abstraction and key informant interviews. A multilevel coding scheme is used to organize the data into a matrix along key domains, which is then reviewed and verified by the key informants.

Principal Findings

This instrument can usefully differentiate between and among Medicaid fee-for-service programs and Medicaid managed care plans along key domains of interest. Beyond documenting basic features of the plans and providing contextual information, these data will support the refinement and testing of hypotheses about the impact of public sector managed care on access, quality, costs, and outcomes of care.

Conclusions

If managed behavioral health care research is to advance beyond simple case study comparisons, a well-conceptualized set of instruments is necessary.

Keywords: Managed behavioral health care, Medicaid managed care, public sector, managed care contracts

It has become commonplace in discussions of public behavioral health policy to note both the ubiquity and difficulty of defining managed care with any degree of precision. The term managed care is used to depict a wide variety of organizational forms, financial arrangements, and regulatory devices that vary considerably in structure, function, and impact on the care of people with behavioral health disorders. The development, implementation, and evaluation of public sector managed care plans has been hindered by the lack of a systematic vocabulary for describing them and the absence of instruments to operationalize this vocabulary into a set of measurement procedures. Our current limited knowledge about the effect of public sector reforms has stemmed, at least in part, from the failure of past evaluations to address the complexity of organizational, financial, and clinical care arrangements, and to document the ways in which such arrangements affect access to care and clinical practice, and therefore individual consumer outcomes. A well-conceptualized set of instruments and procedures for describing managed behavioral health care programs and capturing differences between them would be a significant contribution to the field.

To that end, the authors and their colleagues developed and pilot-tested an instrument to enable investigators to categorize public sector managed care arrangements. A version of this instrument is currently being used in the Managed Behavioral Health Care in the Public Sector Study, a 21-site study supported by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).

Background

Public spending on mental health care ($35.1 billion in 1996) exceeds private spending even though the privately insured population in the United States is three times larger than the publicly insured or uninsured population (McKusick et al. 1998). This is because most of the people with severe mental illness in the population are either uninsured or covered by public insurance programs such as Medicaid. It is no small matter, then, that public behavioral health systems are in the midst of a dramatic revolution. States are rapidly moving people with severe mental illness into managed care plans, using the opportunity provided initially under HCFA 1115 and 1915(b) waivers and more recently under more flexible Medicaid program requirements (liberalized under the Balanced Budget Act of 1997).

The application of private sector managed care principles to public sector behavioral health care has received a generally negative response from advocacy organizations even though managed care (at least in theory) holds the potential for enhancing access and quality of public sector care. For example, if the introduction of managed care results in more flexible (in contrast to narrowly defined) benefits, the promotion of innovative new service approaches, and improved efficiency through capitated financing, public sector behavioral health systems would be vastly improved over the status quo (Ridgely and Goldman 1996). However, there is reason to advocate caution in the application of private sector managed care strategies to more vulnerable populations such as those served in the public sector. Among the chief concerns is the fear that private sector experience in providing benefits to employed populations may not be readily transferable to treating indigent, and especially severely disabled, populations (Taube, Goldman, and Salkever 1990; Christianson and Osher 1994).

Research evaluating Medicaid managed behavioral health care demonstrations suggests that costs can be contained, at least in the initial shift from fee-for-service to managed care. Much of the cost containment has come from reductions in the use of inpatient care (e.g., Frank and McGuire 1997). However the literature also raises questions about the potential impact of managed care on more vulnerable populations such as adults with severe mental illness. Medicaid managed care initiatives in Tennessee (Chang et al. 1998) and Minnesota (Lurie et al. 1992) have been plagued by problems such as risk segmentation as a result of inadequate risk adjustment of capitation rates. While overall there is little evidence in the literature that managed care negatively affects quality of care, research has suggested that there may be a decline in the quality of care for people with severe mental illness in managed care (Popkin et al. 1998; Christianson et al. 1995; Lurie et al. 1992). These findings suggest that adverse selection, problems in continuity of care, and lower quality of care are all issues that may affect people with severe mental illness enrolled in managed care plans.

Empirical research on the implementation and effects of public sector managed behavioral health care has not kept pace with the quickly changing marketplace, leaving many critical public policy questions unanswered. Because of the large variation and rapid changes in the structure of public systems, even basic information that tracks implementation and describes the structural form and context of managed care innovations in the public sector is lacking. Only a handful of case studies of selected programs have documented the effects of public managed behavioral health care programs on access, utilization, costs, or quality of care (Rothbard 1999). Few if any studies have attempted to open the “black box” of managed care (Pincus, Zarin, and West 1996). Clearly, research is needed to assess the efficacy of various types of managed care arrangements, and to determine which components of these arrangements are most helpful or detrimental to the goal of providing quality behavioral health care at a reasonable cost.

Studying Public Sector Managed Care Arrangements

The term managed care is often used and infrequently defined even in the professional literature. In a sense, any agency administering or providing health insurance or health care services can be thought of as “managing” care. Some references to managed care are particular to specific techniques (e.g., utilization review), specific types of financing (e.g., capitation) or specific types of organizations (e.g., health maintenance organizations [HMOs]). However, the American Medical Association (AMA) has adopted a definition of managed care that provides a broad template for thinking about the kinds of arrangements, techniques, and processes that may be subsumed under the heading managed care. The AMA defines managed care as “the processes or techniques used by any entity that delivers, administers, and/or assumes risk for health services in order to control or influence the quality, accessibility, utilization, costs, and process or outcomes of such services provided to a defined population” (AMA 1999).

The key aspects of managed care embedded in this definition include: an enrolled population; a purchaser's use of an entity to deliver, administer, or assume financial risk for care for that enrolled population; and the use of specific techniques or processes by that entity to control, coordinate, or influence access, utilization, quality, costs, or client outcomes. Although trends in managed care are constantly evolving, and specific arrangements, techniques and processes may differ dramatically across plans, the combination of a defined population, the presence of an entity other than the purchaser involved in administering care, and the use of techniques or processes designed to contain health care expenditures and/or affect accessibility, utilization, and/or quality of care are the major characteristics that differentiate managed from “unmanaged” care. Very often the assumption of financial risk on the part of the administrative entity is also present. Managed care may also include the use of a defined network of providers who have accepted a discounted fee schedule or assumed financial risk for providing care to a defined population.

Whether there is an important distinction to be drawn between the public and private sector in the context of managed care is an unanswered question. This article focuses attention on structures in the public sector although this distinction applies more to the source of funds (e.g., Medicaid), the enrolled populations (e.g., recipients of government assistance such as Supplemental Security Income [SSI] or Temporary Assistance to Needy Families [TANF]), and the ultimate legal responsibility of the purchaser (i.e., states cannot delegate all liability to managed care organizations) than to the managed care structures themselves. Many of the state Medicaid agencies have chosen private, for-profit vendors to administer their managed behavioral health care programs (Lewin Group 1998).

Health services researchers have recognized the need to characterize managed care arrangements at some level of detail, however, no widely accepted instruments currently exist in the behavioral health care arena. Most evaluations to date have relied upon broad characterizations of managed care structures or have not attempted to describe the arrangements at all.1 None has successfully described “nested” relationships within multilevel managed care arrangements in spite of the fact that multilevel arrangements are the norm and not the exception.

By the mid-1990s investigators began to focus on the formal, written contracts between state Medicaid agencies and their managed behavioral health care vendors (and between vendors and their providers). For example, using elaborate coding schemes, Rosenbaum and her colleagues captured rich, detailed information on specific features of managed behavioral health care plans from their contracts (Rosenbaum, Silver, and Weir 1997). Making contracts the focus of data collection was purposeful—unlike other documents, contracts define legal relationships between the purchaser, the managed care vendor, and other parties and are legally enforceable reflections of substantive agreements. These investigators identified a vast array of potentially important contract elements and described them exhaustively because the purpose of their endeavor was to inform public sector purchasers to write contracts that better achieved their public policy goals. The sheer number of features recorded, however, limited the utility of their protocol for research purposes.

Other attempts to specify key features of managed care arrangements deserve mention, even though they were not exclusively focused on public sector managed care. In the mid-1990s, investigators in both the mental health and substance abuse fields began employing mail surveys to identify key aspects of managed care by using providers (rather than managed care plans) as the unit of analysis. For example, investigators with the American Psychiatric Association (Zarin et al. 2000) used a mail survey of member psychiatrists to identify utilization management techniques and financial/resource constraints. Investigators at the University of Michigan, using data from an NIDA-funded nationalsurvey of outpatient substance abuse treatment units Drug Abuse Treatment System Survey (DATSS), provided a systematic look at how managed care is influencing substance abuse treatment by identifying the influence of such managed care features as utilization review, prior authorization, and treatment guidelines or restrictions (Alexander and Lemak 1997a; 1997b; 1997c). Neither of these studies surveyed managed care plans themselves and therefore data on the organizational structure of managed care plans is very limited.

Building on these studies, our method focuses data collection on managed care organizations themselves rather than using provider agencies or individual providers as the unit of analysis. In comparison to the studies described above, our methods: (1) employ contract review but focus on a smaller number of key factors hypothesized to be related to changes in service utilization patterns and key outcomes; (2) focus on developing information at multiple levels, allowing us to investigate nested relationships among key players; and (3) include explicit procedures to verify the accuracy of the information.

Development of a Conceptual Framework and Instrument

This paper introduces a conceptual framework and describes an instrument for categorizing managed care arrangements, in order to describe differences between managed and “unmanaged” care and among managed care arrangements. As an initial step in instrument development, an extensive review of the managed care literature was completed, with a special focus on the classification of managed behavioral health care arrangements.

Our thinking about the influence of contextual and organizational factors on the care provided to people with behavioral health disorders in the public sector was influenced by the contemporaneous work of Pincus, Zarin, and West (1996) in the field of private sector psychiatry and by Landon, Wilson, and Cleary (1998) in the field of primary health care. Each group of investigators suggested that it was necessary to describe managed care plans in terms of their key characteristics and then to study the effects of those characteristics singly and in combination to understand the influence of managed care on the delivery of health care services.

In their article on the “black box” of managed behavioral health care, Pincus and his colleagues (1996) identified three structural elements posited to influence outcomes—organizational and contractual relationships; financial arrangements; and procedural arrangements. They also identified the potential mechanisms through which these elements can influence outcomes—by affecting the flow and characteristics of patients through the plan and by affecting the selection and utilization of treatments. Similarly, Landon and colleagues (1998) argued that organizational structures can influence the treatment process and therefore client outcomes such as quality of care. They posited four basic ways that primary health care organizations can alter the quality of care they provide: (1) through resource allocation and selection of specific providers; (2) through patient education and other enrollee-focused mechanisms; (3) through larger community-based or public health efforts; and (4) by influencing individual provider behavior.

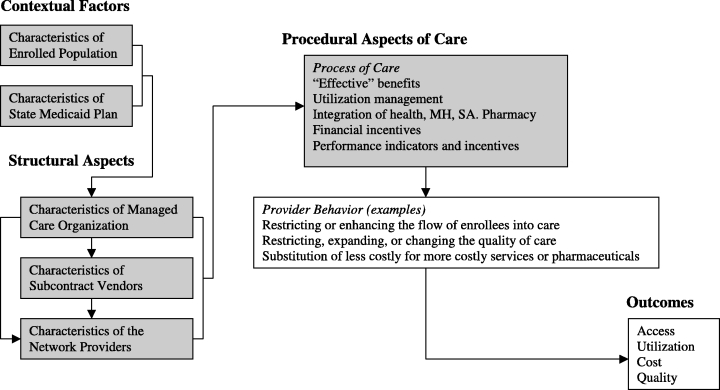

Like these investigators, our conceptual framework is based on the work of Donabedian, which links elements of structure with process and outcomes (Donabedian 1980). Figure 1 illustrates our conceptual model, beginning with an understanding of key factors outside of the managed care arrangement. Within the “contextual factors” we identify two important considerations: the characteristics of the enrolled population and the characteristics of the state Medicaid program (which are likely to have an influence over who is involved in the managed care arrangement and how it is constituted).

Figure 1.

Effects of Managed Care on Behavioral Health Care in the Public Sector

The literature review and our exploratory interviews with health plans in Florida suggested that the instrument developed to collect data on the “structural aspects” of managed care plans, in order to be useful, must be sensitive to the complexity of organizational arrangements in public sector managed care initiatives. For example, States may contract with more than one entity to manage and/or provide behavioral health services to Medicaid enrollees in a single geographic area. Even where there is an exclusive contract with a single managed care organization (MCO) within a geographic area, MCOs may enter into a variety of legal and contractual arrangements with specialty behavioral health organizations (BHOs), other subcontractors, vendors, and providers. Each of these nested relationships may differ in terms of contracted responsibility, payment arrangement, exposure to risk, and authority to control utilization.2 Any instrument developed to characterize managed care arrangements and to make cross-state comparisons must be able to capture information in these nested contracts within an overall plan.

“Procedural aspects” include the specific techniques or processes by which the structural entities control, coordinate, or influence the behavior of providers. These include techniques or processes designed to contain expenditures (e.g., shifting financial risk), and to effect access (e.g., gatekeeping, formularies), utilization (e.g., prior authorization) and quality of care (e.g., performance monitoring). Our conceptual model suggests that processes of care affect the behavior of providers and ultimately client outcomes, although the instrument we propose does not measure provider behavior or client outcomes.

Following the completion of the literature review and the development of our conceptual framework, and working with the template developed by George Washington University investigators (Rosenbaum, Silver and Weir 1997), an initial set of critical domains was developed, framed by the question, “based on current knowledge, what aspects of managed care arrangements are the most likely to have an effect on patterns of service utilization and, therefore, consumer outcomes, broadly conceived?” A national expert panel was convened, composed of services researchers, managed care industry consultants, representatives of state Medicaid and mental health authorities, national mental health organizations, mental health consumers, and SAMHSA investigators. The expert panel reached consensus on inclusion of six domains in the draft protocol: general description of the managed care plan; enrolled population; benefit design; payment and risk arrangements; composition of provider networks; and accountability. Many items were considered but not included in the instrument, not because they were not of interest to some policymakers or useful in differentiating plans, but because no hypotheses were generated about how that domain or item would be related to key outcomes.3

Domains in the Protocol

General Description of the Managed Care Plan

The first domain includes basic information on the Medicaid managed care program (size, geography, parties) as well as questions pertaining to the organizational features of the managed care plans. Managed care organizations differ in their internal organizational structure and their strategic relationships with other organizations within a managed care plan. Tax status (e.g., private, public, quasi-public) and profit status (e.g., for-profit, not-for-profit, voluntary) may be important indicators because they may portend both the incentive for and the ability of the organization to contain costs and to pursue other goals (e.g., improve the quality of care, increase access to care, etc.). Whether particular MCO legal structures (e.g., partnerships between independent companies versus single corporations) are important to these goals is an empirical question. Managed care organizations also differ in the extent to which they “make” or “buy” services, including the extent to which they delegate duties to subcontractors (e.g., when an MCO contracts with a behavioral health organization to deliver mental health services to its members).

Enrolled Populations

The numbers and types of individuals covered by a managed care plan may serve as a predictor of differences in access, service utilization, and costs. The size of the enrolled population or base rate of covered lives may be an indication of the potential financial viability of the plan. Generally, in order to be viable, capitated plans need to spread risk across large numbers of individuals. Plans that are too small or that have enrolled a homogeneously needy population, absent capitation rates that adequately reflect need, may face financial difficulties that could result in restricted access to care.

Identifying the proportion of beneficiaries who are in various age and eligibility categories characterizes the plan's case mix (e.g., by the proportion of SSI versus TANF recipients). It should be noted, however, that disability status must be treated with caution because it is an imperfect measure of severity of illness (Shinnar et al. 1990). Undoubtedly case mix will have an effect on patterns of service utilization and therefore costs (e.g., people with disabilities are more likely to use high levels of behavioral health as well as health services). Eligibility categories may also be expected to impact the composition of the network of providers. Issues of rate-setting may also be raised; where two or more plans are competing within a single public sector market, there may be risk segmentation if the majority of adults and children with disabilities accumulate into one plan—putting some plans at additional financial risk, and thereby increasing the possibility that plans will deny care to control costs.

Benefit Design, Medical Necessity, and Utilization Management

Traditional, unmanaged Medicaid benefit plans consist of a set of covered services provided by qualified providers that state agencies agree to reimburse—often at below market rates. Utilization in this demand-driven system is controlled by limiting the covered services. The move to managed care has shifted the focus to a supply-side set of cost controls. Thus, the rules for accessing services (e.g., medical necessity criteria) become as important as the list of covered services (the benefit plan). It is important to note, however, that these care management controls (e.g., prior authorization for services, formularies) also exist in many fee-for-service insurance plans. In fact, most fee-for-service insurance plans now incorporate utilization management features making it critical to specify these arrangements in both conditions when making comparisons between managed care and unmanaged plans (Fried et al. 2000).

The benefit design is important in understanding and comparing utilization patterns across plans. Benefit design both specifies a list of services and a set of substitutions for those services (enabling comparisons on comprehensiveness and flexibility of service coverage) and drives the specification of the provider network. The contract between a purchaser and MCO identifies service categories that are specifically excluded by contract as well as services that are covered by the plan.4

The rules for accessing services are as important as the amount, scope, and duration limits in the benefit plan. Plans may vary in terms of how and by whom medical necessity criteria are developed and implemented, the range of services to which each criteria apply (e.g., medical versus psychosocial), the mechanisms employed to control access (e.g., prior authorization, concurrent review, clinical or treatment protocols), and the level at which authority for decision making resides (e.g., treating physician versus MCO).

Another potentially important aspect of benefit design is the extent of integration (or lack thereof) among health, pharmacy, mental health, and substance abuse services. Integration of benefit does not always predict integration of services, however. As has been observed in Florida, even where the health and behavioral health premium are integrated, many HMOs carve out the behavioral health benefit to BHO subcontractors (Ridgely, Giard, and Shern 1999).

Composition of Provider Networks

The ratio of providers to beneficiaries, as well as the types of institutional and individual providers with which a plan contracts, may be important variables in understanding patterns of service utilization and costs across plans. Information on the number of individual providers by professional role (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker) is important, as well as the ratio of providers to enrollees, and whether a plan primarily refers to a core network of providers—even though the plan's actual network may be several times larger.

A public policy issue of growing importance is whether to mandate the inclusion of so-called “safety-net” providers (Reuters Medical News 2000). These providers are typically public or nonprofit organizations that have experience in serving Medicaid recipients with severe behavioral health disorders and who are publicly-funded to serve the uninsured, indigent population. Because many poor people cycle on and off the Medicaid rolls even within a single year, safety-net providers may serve an important function in maintaining continuity of care when clients become ineligible for Medicaid.

Payment and Risk Arrangements

The distribution of financial risk among the purchaser (e.g., state Medicaid agency), the MCO and its subcontractors, and the service provider is another aspect of managed care believed to have an impact on utilization, costs, and other outcomes. The instrument focuses on two aspects of the financing of managed care arrangements—the payment arrangements (e.g., fee-for-service, capitation) and the mechanisms for ameliorating the risk (e.g., risk pools, shared savings). Within a single managed care plan, payment and risk-sharing arrangements may vary across service type or provider type. For example, institutional providers such as community mental health centers may have capitation contracts, while private practitioners are reimbursed on a discounted fee-for-service basis. Contracts may also include stepped-up/down risk sharing arrangements that change in a predefined way over the life of the contract. Since with risk comes the incentive to deny or restrict care in order to stay solvent or make a profit, it is important to understand whether and how risk is distributed, and how risk exposure may be expected to change over time.

Accountability

While much has been written about the market as regulator, in most health care markets consumers don't have enough information or the flexibility to “vote with their feet” and leave plans they believe to be poor performers. Yet, having a single, identifiable point of accountability has been suggested as a primary strength of managed care. Accountability is measured with a single indicator—the capacity and demonstrated willingness to regulate performance through performance indicators, including measures of consumer outcome. The presence of particular mechanisms of accountability must be coupled with knowledge of the possible and actual consequences of failing to meet an accountability standard and by knowledge about the likelihood, timing, type, and severity of response.

Table 1 identifies the content items in each of the six domains (discussed above) and indicates the levels at which the items are measured.5 As indicated in Table 1, the first domain of the instrument provides information on the state Medicaid plan (Figure 1: contextual factors) and the characteristics of the MCO, vendors and network of providers (Figure 1: structural aspects). The second domain of the instrument provides information on characteristics of the enrolled population (Figure 1: contextual factors). The third domain (benefit design, medical necessity, and utilization management) provides information on actual and effective behavioral health benefits as well as processes health plans and providers use to expand or limit access, utilization, and cost (Figure 1: procedural aspects). The fourth domain (payment and risk arrangements) provides additional process of care information focused on the use of financial incentives and the shifting of risk among the parties (Figure 1: procedural aspects). The fifth domain (composition of provider networks) extends the analysis of structure beyond the health plan to the provider network (Figure 1: structural aspects). Finally, the sixth domain adds information on accountability (Figure 1: procedural aspects). Taken together, these descriptive data will enable investigators to describe the context, structure, and processes of managed behavioral health care and to understand their relationship with one another.

Table 1.

Major Dimensions of Managed Behavioral Health Care Arrangements

| Levels | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Content | MCO | BHO | Provider | |

| 1 | Description of managed care plan | •Parties to the contract | X | X | |

| •Type of Medicaid waiver or state plan amendment | X | ||||

| •Geographic areas | X | X | |||

| •Duration of the contract | X | X | |||

| Organizational features of the managed care plan | •Tax status | X | X | ||

| •Profit status | X | X | |||

| •Affiliation with a larger corporate entity | X | X | |||

| •MCO roles under the contract | X | X | |||

| •Contract as % of MCO business | X | X | |||

| •Legal structures (e.g., partnerships, subcontracts) | X | X | |||

| 2 | Enrolled population | •Base rate of covered lives | X | X | |

| •% eligibility, age, & disability category | X | X | |||

| 3 | Benefit design, medical necessity, and utilization management | •Integration of health, MH, SA, pharmacy •Covered services (exclusions, amount, scope & duration limits, financing) | X | X | |

| •State hospitals and court-ordered treatment | X | ||||

| •Public sector services available outside of the managed care plan | |||||

| •Medical necessity definition & sources | X | X | X | ||

| •Involvement of treating clinician in determinations | X | X | X | ||

| •Clinical appeals processes | X | X | X | ||

| •Procedures to manage utilization (e.g., prior authoriz.) | |||||

| 4 | Payment and risk arrangements | •Financial arrangements (e.g., capitation, fee-per-episode, case rate) and % of contract dollars | |||

| •Administrative fees | X | X | X | ||

| •PMPM (capitation only) | X | X | X | ||

| •Capitation rates | X | X | X | ||

| •Risk sharing arrangements (e.g., stop-loss, risk corridor) | X | X | X | ||

| 5 | Composition of Provider Networks | •Types of individual providers (payment, risk, profit sharing) | X | ||

| •Types of institutional providers (payment, risk, profit sharing) | X | ||||

| •Ratio of providers to enrollees | X | ||||

| •Safety net providers | X | ||||

| •Use of core or tier of providers | X | ||||

| 6 | Accountability | •Performance indicators | X | X | X |

| •Sanctions for non-performance | X | X | X | ||

Generating Hypotheses About the Effects of Managed Care on Provider Behavior and Outcomes

Based on the literature, our conceptual model and our own experience in collecting these data in public sector settings, we hypothesize that a number of the key elements of managed care might be expected to influence specific outcomes of behavioral health care. For example:

The characteristics of the enrolled population (Table 1: Domain 2) may be important in understanding patterns of access and service utilization. High-risk and chronically disabled enrollees will likely have greater service needs and difficulty accessing care and may be more vulnerable to underutilization in capitated plans without adequate risk adjustment.

Incentives inherent in capitation financing (Table 1: Domain 4)—where plans and/or providers are at full risk for the costs of services—may be important to understanding who gets access to treatment and what behavioral health treatment is available. Plans or providers at risk may have more clinical flexibility (which may result in improved quality of care) but may also experience significant cost containment pressures that may cause them to limit the amount, scope, or duration of services.

The characteristics of the pharmacy benefit (Table 1: Domain 3)—for example, risk for pharmacy costs and composition of the formulary—may determine whether clients receive new generation pharmaceuticals (e.g., atypical antipsychotic agents) in large numbers. All other things being equal, providers may be less likely to prescribe expensive psychotropic medications when they are at risk for the costs (except as a substitute for more expensive psychotherapy), potentially impacting the quality of pharmacological care.

The characteristics of the utilization management (UM) process (Table 1: Domain 3) may be important to understanding access to particular types of services, for example, whether prior authorization is required for all services or just for very expensive services (e.g., inpatient hospitalization and residential substance abuse treatment) and the administrative burden represented by the process. Knowing who performs the UM function (the plan or the provider) may be critical to understanding patterns of care.

The characteristics of the provider agencies in the plan's network(Table 1: Domain 5) may be critical—including whether there are safety net providers experienced in the care of people with severe and chronic illnesses and whether providers have appropriate professional credentials to treat this population.

Whether one element matters can depend on the presence or absence of other elements. For example, whether the cost containment incentives inherent in capitation result in reductions in services will be influenced by whether the contract also includes clinical performance measures associated with a penalty/reward structure. The characteristics of utilization management by an MCO may be unimportant if the BHO and/or providers bear full risk (i.e., there would be no incentive to request authorization for unnecessary services).

It is worth noting that whether cost containment pressures lead to more efficient and appropriate use of services—or to underutilization—is probably at least in part determined by whether there is enough money in the system to provide for a decent floor of care. Large variations across states in per capita spending for public mental health suggest that overall resource availability could account for substantial variation in system performance even under traditional payment systems. Therefore, understanding the larger public sector context in which these systems operate, as well as the historical spending patterns on behavioral health services, is critical to interpreting information gleaned in any study of managed care arrangements and their impact on outcomes.

Conclusion

Linking specific elements of managed care to patterns of service use and consumer outcomes is clearly the next step in managed care research, however, it is not easy to mount such studies. Investigators must take advantage of natural variations in managed care environments and make comparisons across those environments using common study methodologies. Because the elements of managed care are many and variously combined, studies that combine large numbers of sites, or the meta-analysis of studies that compare limited numbers of sites, may be required to begin to understand the relationship between plan characteristics, service patterns, and outcomes. Careful and systematic assessment and description of the managed care “black box” across these environments can provide a context for interpreting and understanding their differential effects on outcomes. Even when predictions regarding the expected effects of organizational incentives on outcomes are not borne out, important insights can be gained from a close look at the plans and provider agencies.

In conclusion, if research on managed behavioral health care is to advance beyond the stage of simple case study comparisons—one step in the right direction is to identify a series of important domains and to collect information systematically with a well-conceptualized set of instruments and procedures. Agreement on a set of domains likely to predict service utilization and consumer outcomes is imperative. This conceptual framework and instrument are a work in progress toward that end.

Acknowledgments

This work has been a collaborative and multi-institutional effort. Collaborators in the development of the instrument include (alphabetically): Christine Bishop (Brandeis); Mady Chalk (CSAT Office of Managed Care); Sheila Donahue (NYS-OMH); James Fossett (SUNY); Suzanne Gelber (SGR Health-Oakland, CA); Aviva Goldstein (SUNY); Jeffrey Merrill (TRI-Philadelphia); Judy Samuels and Carole Siegel (Nathan Kline Institute, NY). We also gratefully acknowledge the members of our National Managed Care Expert Panel. Those who have not been named above include (alphabetically): Colette Croze, Trevor Hadly, Kelly Kelleher, Candace Nardini, Kathy Penkert, John Petrila, Harold Pincus, and Laura Van Tosh.

Notes

For example, in the public sector, prior investigators have surveyed states to collect basic information on Medicaid waiver programs (e.g., Pires et al. 1995; National Academy for State Health Policy 1997; Lewin Group 1998). These data collections resulted in comparisons of selected state-level Medicaid managed care program features but provided little or no information about the managed care arrangements themselves. Other investigators attempted to describe Medicaid managed care structures by classifying them into organizational types (e.g., Hurley, Freund, and Paul 1993). Unfortunately, such typologies have had limited utility due to rapid changes in the marketplace.

For example, the contract between the state Medicaid agency and the MCO may be capitated but the MCO may pay providers on a fee-for-service basis. The nested relationship (in this case the relationship between the MCO and provider) clearly has a different set of incentives than those operating in the purchaser/MCO relationship. Understanding this nested relationship would be the key to understanding provider behavior. In the alternative, without an understanding of this nested relationship, an investigator might make incorrect assumptions about the effects of capitation or incorrect interpretations about provider behavior in response to incentives in capitated contracts.

For example, the capitalization and solvency of MCOs is important to state regulators in assessing whether the state should contract with a particular managed care plan. However, no specific hypotheses were generated about how capitalization and solvency of managed care organizations might predict different patterns of service utilization and therefore consumer outcomes. The same was true for critical issues such as leadership and organizational culture (participants acknowledged a probable effect of “charismatic” leadership) and adequacy of management information systems. These, among others, were considered important, but no specific hypotheses were generated by the expert panel.

For example, a contract may have exclusions for particular types of services (i.e., vision or dental benefits), for particular diagnoses (e.g., autism) or for categories of treatment (e.g., experimental or investigational drugs or devices). In addition, contracts may specify services that are available only to specific populations (e.g., health plans may cover detoxification and substance abuse treatment for pregnant women, even though substance abuse benefits are not generally available).

Initial exploratory work using this instrument in Florida suggested that an investigation of these domains using case study methods should include both contract abstraction and interviews with key informants at various levels of the managed care plan (Ridgely, Giard, and Shern 1999). Three levels of information gathering were pursued: (1) contracts between the Medicaid agency and the managed care organization; (2) contracts between the MCO and any subcontractors; and (3) contracts between the MCO or subcontractor and service providers. After the contract abstraction and telephone interviews were complete, a matrix summarizing the information was produced for each plan and interview respondents were provided the summary for their review and comment. Strategies for increasing the rigor of case study data collection have been outlined elsewhere (Silverman, Ricci, and Gunter 1990). For example, in addition to using a detailed protocol as a guide: The design of the data collection permitted completion of the case study work quickly, thereby assuring the timeliness and accuracy of the information; a multidisciplinary team of interviewers was employed; the design allowed for re-interviewing of some informants for clarification and verification of interview information in order to resolve factual inconsistencies; in-depth interviews were targeted on the most knowledgeable informants; and external review by the organizations and agencies being studied was employed to verify the accuracy of the data.

This work was supported in part by grants from the New York Center for the Study of Issues in Public Mental Health (NIMH Grant #1P50MH5139-05) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Grant #5 UR7 TI11278-02) with support from UCLA-RAND Research Center on Managed Care and Psychiatric Disorders. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding agencies.

References

- Alexander JA, Lemak CH. “Directors’ Perceptions of the Effects of Managed Care in Outpatient Substance Abuse Treatment”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1997a;9:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA. “Managed Care Penetration in Outpatient Substance Abuse Treatment Units”. Medical Care Research Review. 1997b;54:490–507. doi: 10.1177/107755879705400406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA. “The Effects of Managed Care on Administrative Burden in Outpatient Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities”. Medical Care. 1997c;35:1060–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199710000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association. Principles of Managed Care. 4th ed. Chicago: American Medical Association Council on Medical Service; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chang CF, Kiser LJ, Bailey JE, Martins M, Mirvis DM, Applegate WB. “Tennessee's Failed Managed Care Program for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(10):864–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson J, Gray D, Kohlstrom LC, Speckman ZK. “Development of the Utah Prepaid Mental Health Plan”. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research. 1995;15:117–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson J, Osher F. “HMOs Health Care Reform and Persons with Serious Mental Illness”. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:898–905. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.9.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring: The Definition of Quality and Approaches to Its Assessment. vol. 1. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Frank R, McGuire T. “Savings from a Medicaid Carve-out for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services in Massachusetts”. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:1147–52. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.9.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried B, Topping S, Morrissey JP, Ellis AR, Stroup S, Blank M. “Comparing Provider Perceptions of Access and Utilization Management in Full-Risk and No-Risk Medicaid Programs for Adults with Serious Mental Illness”. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2000;27:29–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02287802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley RE, Freund DA, Paul JE. “Describing and Classifying Programs Managed Care in Medicaid: Lessons for Policy and Program Design”. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Landon BE, Wilson IB, Cleary PD. “A Conceptual Model of the Effects of Health Care Organizations on the Quality of Health Care”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279(17):1377–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin Group. SAMHSA Managed Care Tracking System: State Profiles on Public Sector Managed Behavioral Healthcare and Other Reforms. Fairfax, VA: author; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie N, Moscovice IS, Finch M, Christianson JB, Popkin MK. “Does Capitation Affect the Health of the Chronically Mentally Ill? Results from a Randomized Trial”. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;267:3300–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKusick D, Mark TL, King E, Harwood R, Buck J, Dilonardo J, Genvardi J. “Spending for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment 1996”. Health Affairs. 1998;17:147–57. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.17.5.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy for State Health Policy. Medicaid Managed Care: A Guide for States. Portland, ME: 1997. author. [Google Scholar]

- Pincus HA, Zarin DA, West JC. “Peering into the Black Box: Measuring Outcomes of Managed Care”. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:870–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires S, Stroul B, Roebuck L, Friedman R, McDonald B, Chambers K. Health Care Reform Tracking Project: The 1995 Survey. Tampa, FL: Louis de al Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, University of South Florida; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin M, Lurie N, Manning W, Harman J, Callies A, Gray D, Christianson J. “Changes in the Process of Care for Medicaid Patients with Schizophrenia in Utah's Prepaid Mental Health Plan”. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:518–23. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.4.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuters Medical News. [April 9, 2000];“America's Healthcare ‘Safety Net’ in Danger of Collapsing”. 2000 http://managedcare-medscape.com/19691.rhtml.

- Ridgely MS, Goldman HH. “Putting the Failure of National Health Care Reform in Perspective: Mental Health Benefits and the ‘Benefit’ of Incrementalism”. Saint Louis University Law Journal. 1996;40:407–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgely MS, Giard J, Shern D. “Florida's Medicaid Mental Health Carve-out: Lessons from the First Years of Implementation”. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 1999;26:400–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02287301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridgely MS, Giard J, Shern D. “Major Dimensions of Managed Behavioral Health Care Arrangements”. 1999 Copies of instruments administration manuals, and glossary available at http://www.rand.org/health/surveys.html.

- Rosenbaum S, Silver K, Weir E. An Evaluation of Contracts between State Medicaid Agencies and Managed Care Organizations for the Prevention and Treatment of Mental Illness and Substance Abuse. vols. 1–2. Washington, DC: George Washington University Center for Health Policy Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbard A. “Managed Mental Health Care for Seriously Mentally Ill Populations”. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 1999;12:211–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shinnar A, Rothbard A, Kanter R, Adams K. “Crossing State Lines of Chronic Mental Illness”. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1990;41:756–60. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.7.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J, Ricci E, Gunter M. “Strategies for Increasing the Rigor of Qualitative Methods in Evaluation of Health Care Programs”. Evaluation Review. 1990;14:57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Taube C, Goldman H, Salkever D. “Medicaid Coverage for Mental Illness: Balancing Access and Coverage”. Health Affairs. 1990;9(1):5–18. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.9.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarin DA, West JC, Pincus HA, Tanielian TL. “Characteristics of Health Plans That Treat Psychiatric Patients”. Health Affairs. 2000;18:226–36. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]