Abstract

The median preoptic nucleus (MnPN) of the hypothalamus contains sleep-active neurones, and sleep-related Fos-immunoreactivity (IR) in this nucleus is primarily expressed in GABAergic cells. The MnPN also contains cells responsive to hypertonic saline and to angiotensin-II (Ang-II). To clarify functional relationships between MnPN neurones involved in the regulation of sleep and body fluid homeostasis, we examined c-fos expression in the MnPN after administration of hypertonic saline and Ang-II in both spontaneously sleeping and sleep-deprived rats. Systemic administration of hypertonic saline and intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injection of Ang-II increased Fos-IR in both spontaneously sleeping and sleep-deprived rats, compared to control animals. To determine if the population of MnPN neurones activated in response to osmotic and hormonal stimuli is similar to or different from neurones activated during sleep, we quantified Fos-IR in MnPN GABAergic neurones in spontaneously sleeping hypertonic saline- and Ang-II-treated rats versus respective control rats. Fos-IR evoked by these treatments occurred primarily (80–85%) in non-GABAergic neurones. Findings of the present study provide evidence that separate populations of MnPN neurones are involved in the regulation of sleep and body fluid homeostasis.

Recent studies implicate the median preoptic nucleus (MnPN) of the hypothalamus as a sleep-promoting site. Involvement of MnPN in the regulation of sleep and waking was first demonstrated by a functional mapping of Fos-immunoreactivity (IR). The number of Fos-immunoreactive neurones (IRNs) was increased following sustained sleep (Gong et al. 2000). The presence of sleep-active neurones in the MnPN was confirmed by electrophysiological studies: nearly 76% of the recorded MnPN neurones displayed elevated discharge rates during sleep (Suntsova et al. 2002). Sleep-associated Fos-IR in the MnPN was colocalized with IR for glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), a marker of GABAergic neurones. The number of sleep-active GAD-positive cells in this nucleus was positively correlated with the total amount of the preceding sleep (Gong et al. 2004). In addition, the number of MnPN GABAergic neurones manifesting Fos-IR was significantly elevated during recovery sleep following sleep deprivation (Gong et al. 2004). Taken together, these findings suggest an involvement of MnPN GABAergic neurones in homeostatic regulation of sleep.

The MnPN also functions as an important relay nucleus in the central pathways mediating the regulation of body fluid homeostasis (McKinley et al. 1996, 1999). In response to hydromineral challenge, MnPN neurones display increased Fos-IR (Oldfield et al. 1991a, 1994; Sharp et al. 1991; Hamamura et al. 1992; Xu & Herbert, 1995). The MnPN has anatomical and functional connections with several structures involved in osmoregulation, including the vascular organ of the lamina terminalis, the subfornical organ and the supraoptic nucleus (Camacho & Phillips, 1981; Lind & Johnson, 1982; Lind et al. 1985; Tanaka et al. 1987; Wilkin et al. 1989; Weiss & Hatton, 1990; Oldfield et al. 1991b; Armstrong et al. 1996; Krout et al. 2002). Destruction of the MnPN inhibits dehydration-induced vasopressin release from the hypothalamus and impairs drinking behaviour (Manciapane et al. 1983; Gardiner & Stricker, 1985; Wilkin et al. 1986; Xu & Herbert, 1995, 1996; Ludwig et al. 1996).

Functional relationships between MnPN neurones involved in sleep regulation and osmoregulation are not known. The present study was designed to determine (1) if the activation of MnPN neurones by osmotic and hormonal stimuli is modified by sleep–waking state and (2) if the population of MnPN neurones activated in response to osmotic challenge is similar to or different from that activated during sleep. To determine the effects of sleep–waking state on the MnPN neuronal response to osmotic challenge, we quantified the expression and distribution of c-Fos IRNs after systemic administration of hypertonic saline and i.c.v. Ang-II in both spontaneously sleeping and sleep-deprived rats. We have previously shown that sleep-related Fos-IR is predominately localized in MnPN GABAergic neurones (Gong et al. 2004). Therefore, we determined the extent to which MnPN Fos-IR evoked by hypertonic saline and Ang-II was or was not colocalized with immunostaining for GAD.

Methods

All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at VAGLA and were conducted according to the guidelines of the National Research Council.

Animals and experimental environment

Fifty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 280–320 g at the beginning of the experiments, were acclimated to a 12-h light–dark cycle (lights-on 08.00 h). The rats were housed individually in environmental chambers. Food and water were available ad libitum and the ambient temperature was maintained at 23 ± 0.5°C.

Surgical procedures and recording

Under ketamine–xylazine anaesthesia (80/10 mg kg−1, intraperitoneally, i.p.), rats were surgically implanted with chronic cortical electroencephalogram (EEG) and dorsal neck electromyogram (EMG) electrodes for assessment of sleep–wakefulness states. Briefly, stainless steel screw electrodes were implanted in the skull for EEG recordings and flexible, insulated stainless steel wires were threaded into neck muscles for EMG recordings. Leads from the electrodes were soldered to a small Amphenol connector and the complete assembly was anchored to the skull with dental acrylic. A stainless steel guide cannula (outer diameter (o.d.) 0.5 mm) for Ang-II i.c.v. injection was stereotaxically placed in the right lateral ventricle and sealed with a removable obdurator (o.d. 0.3 mm).

Animals were allowed a 7–9 day recovery period following surgery. For five consecutive days prior to the experimental day, the rats were connected to a recording cable that was lightly suspended above them by a counter–weighted beam. They remained connected to the cable for 5–6 h (started at 08.00 h) each day. The recording cable joined the miniature connector on the animal's head to a polysomnography recording device (Embla, Medcare Flaga Medical Devices, Reykjavik, Iceland). The EEG and EMG recordings were digitally displayed and stored on a computer using Somnologica software (Somnologica Studio, Medcare Flaga Medical Devices). During experiments, EEG and EMG signals were recorded continuously.

Experimental groups

Twenty-four animals were given either hypertonic saline (1.5 m, 1 ml per 100 mg body weight, i.p.; n = 12) or Ang-II (25 ng in 3 μl of pyrogen-free saline; i.c.v.; n = 12). Animals from i.p. hypertonic saline and i.c.v. Ang-II groups were divided into subgroups (n = 6 in each); one subgroup was permitted 2 h spontaneous sleep after the treatment, while the other was maintained awake for a 2-h period by means of gentle stimuli (tapping on the cage and/or slight movement of the cage) when EEG signs of sleep appeared. Level of sleep homeostatic pressure/drive in sleep-deprived rats was defined by counting the number of attempts to initiate sleep during the experimental procedure. To estimate the accumulation of sleep drive, the number of sleep entries in each rat was averaged per consecutive 10 min interval of the 2 h sleep deprivation period. Rats were well adapted to the procedure of sleep deprivation prior to the start of experiments. Control rats (n = 24) were injected with 0.9% saline via i.p. (n = 12) or i.c.v. (n = 12) and were also divided into spontaneously sleeping and sleep-deprived subgroups of rats (n = 6 in each). In addition to the described four groups of treated animals, a group of untreated rats (n = 6) was allowed 2 h spontaneous sleep from 09.00 h. This group served as an additional (untreated) control for the condition of spontaneous sleep. At the end of all experiments (3 h after lights on), rats were removed from the recording chamber and immediately given a lethal dose of pentobarbital, which was followed by cardiac perfusion.

The hypertonic saline was freshly prepared on the day of the experimental procedure. For Ang-II remote administration, a stainless steel needle (o.d. 0.3 mm) filled with the injectate and connected to 5 μl Hamilton microsyringe (by 1 m of polyethylene tubing) was inserted into the implanted guide cannula 1 h before (at 08.00 h) the experiments began (at 09.00 h). The animals remained undisturbed in their home cages during the course of Ang-II i.c.v. administration that was made over a 1-min period. Empty water bottles were used to observe a drinking response to the treatments. To avoid continued sham drinking, the bottles were removed from the cages in about 5 min after the injection. Water was not provided to the rats throughout the entire post-treatment 2-h period. Placement of the cannula in the right lateral ventricle was histologically confirmed at the end of the experiment.

Immunohistochemistry

Under deep pentobarbital anaesthesia (100 mg kg−1), animals were transcardially perfused with 0.12 m Millonig's phosphate buffer (MPB) for 5 min, followed by 500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.12 m MPB. After perfusion, the bodies of the perfused animals were kept at 4°C for 1 h. The brains were then removed, post-fixed in the same PFA solution for 1 h, washed in 0.12 m MPB and gradually transferred to 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose at 4°C until they sank. Thirty-micrometre coronal sections were cut through the MnPN on a freezing microtome. The sections were processed with Fos staining first. Tissue sections were incubated overnight in a rabbit anti-Fos primary antiserum (AB-5, Oncogene Science; 1 : 15 000) on a shaker, at 4°C. Sections were processed with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 800; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 1.5 h at room temperature, followed by reacting with avidin–biotin complex (ABC, Vector Elite Kit; 1 : 200). Sections were developed with nickel-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Ni-DAB), which produced a black reaction product in cell nuclei. There was no nuclear staining in the absence of primary antiserum. Tissue from sleep deprived groups was stained for Fos protein only. Tissue from spontaneously sleeping groups was also immunostained for GAD. To stain for GAD, the sections were incubated with mouse anti-GAD monoclonal antibody (MAB5406, Chemicon International; 1 : 300) at 4°C over two nights, processed with biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (BA-2001, Vector Laboratories; 1 : 500) and developed with DAB to produce a brown reaction product for double labelling. Omission of the GAD primary antiserum resulted in the absence of a specific staining. After the staining, the sections were mounted on gelatinized slides, dehydrated through graded alcohol, and coverslipped with Depex.

Data analysis

Sleep analysis

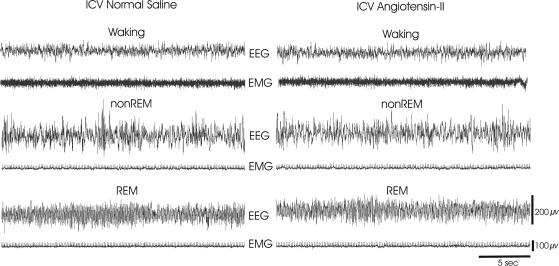

Sleep–wakefulness states of the rats were determined by an experienced scorer on the basis of the predominate state within each 10 s epoch. The scorer was blind to experimental condition and group identity of the animal. Wakefulness was defined by the presence of a desynchronized EEG activity combined with elevated neck muscle tone. Non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep consisted of a high-amplitude slow-wave EEG (with prominent activity in the 2–4 Hz range) together with a low-EMG tone relative to wakefulness. REM sleep was identified by the presence of a moderate-amplitude EEG with dominant theta frequency activity (6–8 Hz) coupled with minimal neck EMG tonus except for occasional brief twitches (see Fig. 2 for examples). The percentage of each state was calculated for the last 90 min of the 2 h recording period.

Figure 2. Examples of polygraphic recordings during wakefulness, NREM and REM sleep (30-s) in I.C.V. normal saline and I.C.V. Ang-II spontaneously sleeping rats.

Both animals show typical electrographic signs of sleep–waking states (see Methods). Abbreviations: EEG, fronto-parietal electro-encephalogram; EMG, dorsal neck muscle electromyogram.

Cell counts

An individual, who was blind to the experimental conditions of the animals, conducted the cell counts. The Neurolucida computer-aided plotting system (MicroBrightField, Inc., Williston, VT, USA) was used to identify and quantify neurones that were single labelled for c-Fos-IR and double-labelled for Fos + GAD-IR. Section outlines were drawn under 20× magnification. Fos-IRNs and Fos + GAD-IRNs were mapped in the section outlines under 400× magnification. All cell counts were calculated for constant rectangular grids corresponding to two areas of interest. (1) The rostral MnPN (rMnPN) grid was a 600 μm × 600 μm square, centred on the apex of the third ventricle rostral to the decussation of the anterior commissure and to bregma (A: 0.1 mm) (Gong et al. 2000). (2) The caudal MnPN (cMnPN) grid was placed immediately dorsal to the third ventricle at the level of the decussation of the anterior commissure, extending 150 μm laterally and 600 μm dorsally just caudal to Bregma (A: −0.26 mm) (Gong et al. 2000).

For both the rostral and caudal MnPN, cell counts were made in three sections and averaged to yield a single value for each rat. Since Fos-IR is high within the ependymal cells lining the ventricular walls following Ang-II i.c.v. injection, and, to a lesser extent, i.c.v. saline, we were careful to exclude these cells from counting.

Statistical analysis

All results are reported as means ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). For sleep stage percentages, a one-way, repeated measures ANOVA was calculated across all five groups that were permitted spontaneous sleep (Table 1). For i.p. injection-treated animals, a one-way non-repeated measures ANOVA was calculated for the number of Fos single-IRNs across four experimental groups: i.p. normal saline sleep-deprived and spontaneously sleeping rats; and i.p. hypertonic saline sleep-deprived and spontaneously sleeping rats (Fig. 6). A similar ANOVA was calculated for the four i.c.v. treated groups: i.c.v. normal saline sleep-deprived and spontaneously sleeping rats; and i.c.v. Ang-II sleep-deprived and spontaneously sleeping rats (Fig. 6). For Fos + GAD cell counts, one-way, non-repeated measures ANOVA was calculated across spontaneously sleeping rats in i.c.v. Ang-II, i.c.v. normal saline and untreated control groups. Following all ANOVAs, significance of the differences between individual group means was assessed with the Newman-Keuls post hoc test. Fos + GAD-IRN counts in spontaneously sleeping i.p. hypertonic saline versus spontaneously sleeping i.p. normal saline control rats were assessed with Student's unpaired t test (Table 2).

Table 1.

Percentage of time spent in Total sleep, NREM sleep and REM sleep for rats that were allowed spontaneous sleep post injection

| Experimental groups | Total sleep (%) | NREM sleep (%) | REM sleep (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| i.p. hypertonic saline (n = 6) | 49.7 ± 2.9* | 42.4 ± 2.1* | 7.3 ± 2.7***† |

| i.p. normal saline (n = 6) | 74.5 ± 3.1** | 60.2 ± 2.9** | 14.3 ± 2.4** |

| i.c.v. angiotensin II (n = 6) | 87.1 ± 5.2 | 78 ± 4.3*** | 9.1 ± 2.9*** |

| i.c.v. normal saline (n = 6) | 86.4 ± 3.8 | 68 ± 2.7 | 18.4 ± 1.8 |

| Untreated rats (n = 6) | 85.3 ± 6.3 | 66.1 ± 3.3 | 19.2 ± 1.7 |

ANOVA indicates significant effect of treatment for percentage total sleep (F4,25 = 588.6; P < 0.001), percentage NREM sleep (F4,25 = 432.3; P < 0.001) and percentage REM sleep (F4,25 = 89.5; P < 0.001).

Significantly different from all other groups, P < 0.001 (Newman-Keuls).

Significantly different from i.c.v. normal saline and untreated rats, P < 0.001 (Newman-Keuls).

Significantly different from i.p. normal saline, i.c.v. normal saline and untreated rats, P < 0.001 (Newman-Keuls).

Significantly different from i.c.v. angiotensin, P < 0.05 (Newman-Keuls).

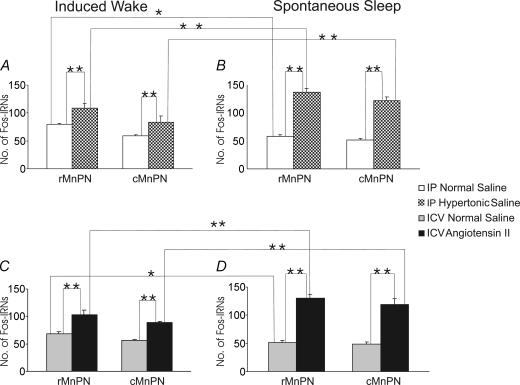

Figure 6. Mean numbers of Fos-IRNs in the rostral and caudal MnPN of hypertonic saline-treated and respective control rats and Ang-II-treated and respective control rats under conditions of induced waking (A and C) and spontaneous sleep (B and D).

A and B, mean numbers of Fos-IRNs in the rostral and caudal MnPN of hypertonic saline-treated and respective control rats under conditions of induced waking (A) and spontaneous sleep (B). C and D, mean numbers of Fos-IRNs in the rostral and caudal MnPN of Ang-II-treated and respective control rats under conditions of induced waking (C) and spontaneous sleep (D). For i.p. injection-treated rats, ANOVA indicated significant effects of experimental conditions in both the rostral (F3,20 = 131.2; P < 0.001) and caudal (F3,20 = 67.1; P < 0.001) MnPN. There were overall significant effects of experimental condition for i.c.v. treated rats as well, in both the rostral (F3,20 = 82.7; P < 0.001) and caudal (F3,20 = 64.8; P < 0.001) MnPN. Individual mean differences as determined by post hoc tests (Newman-Keuls) are indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.01, **P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Mean numbers of Fos + GAD IRNs and the mean percentage of Fos-IRNs that were double labelled for GAD-IR in the MnPN of I.P. normal saline and I.P. hypertonic saline spontaneously sleeping rats

| Rostral MnPN | Caudal MnPN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Groups | No. of Fos + GAD IRNs | % of Fos + GAD IRNs | No. of Fos + GAD IRNs | % of Fos + GAD IRNs |

| i.p. normal saline (n = 6) | 25.4 ± 1.8 | 30.6 ± 1.4* | 17 ± 1.8 | 25.9 ± 1.9* |

| i.p. hypertonic saline (n = 6) | 27.8 ± 2.1 | 20.1 ± 1.5* | 20.25 ± 2.21 | 18.0 ± 1.1* |

The cell counts were not significantly different, but the mean percentage of Fos + GAD double-labelled cells was significantly lower in i.p. hypertonic saline versus i.p. normal saline rats (unpaired t tests) for the rostral (t10 = 8.0;

P < 0.001) and caudal MnPN (t10 = 6.2; P < 0.001).

Results

Sleep and wakefulness

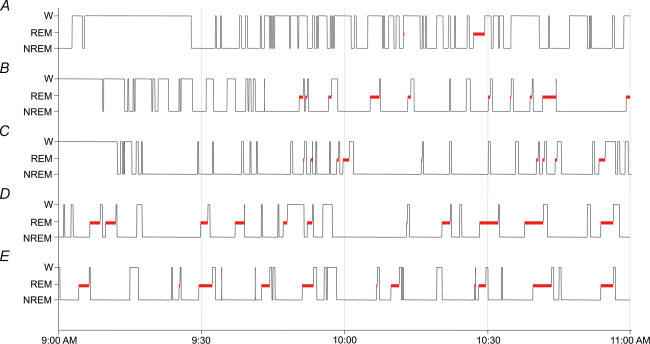

Table 1 presents the percentage of time spent in sleep for the groups of rats that were allowed spontaneous sleep in the post-injection period. As shown, percentage of total time spent asleep was similar in i.c.v. Ang-II, i.c.v. normal saline and untreated rats. However, i.c.v. Ang-II rats showed significant reductions in REM sleep time and increased NREM sleep when compared to respective control and untreated animals. These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Wakefulness time in these rats did not differ significantly, although it tended to be less in Ang-II-treated animals. i.p. hypertonic saline rats had fragmented sleep and significantly reduced total sleep time compared to all other rats (P < 0.05). i.p. normal saline rats also exhibited reduced sleep time, compared to other control groups (i.c.v. normal saline and untreated controls). Examples of the distribution of sleep–waking states across the recording period are shown in Fig. 1. As shown on the diagrams, i.p. hypertonic saline, i.p. normal saline and i.c.v. Ang-II rats had delayed sleep onset compared to i.c.v. normal saline and untreated rats. This was because during the first 15–20 min post-injection, i.p. hypertonic saline and i.c.v. Ang-II rats were actively searching for water, while i.p. normal saline rats exhibited excessive grooming behaviour. While i.p. hypertonic saline and i.c.v. Ang-II altered the amount and/or temporal distribution of sleep and waking, neither treatment altered the electrographic correlates of sleep–waking states. Examples of polygraphic recordings during waking, NREM sleep and REM sleep for an i.c.v. saline control and an i.c.v. Ang-II-treated animal are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 1. Examples of sleep–waking organization in a 2-h period prior to perfusion.

A, i.p. hypertonic saline; B, i.p. normal saline; C, i.c.v. Ang-II; D, i.c.v. normal saline; E, untreated spontaneously sleeping rats.

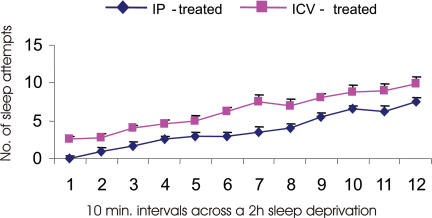

All sleep deprived rats manifested evidence of gradual accumulation of sleep pressure; the frequency of attempts to initiate sleep increased during the deprivation procedure (Fig. 3). i.p. hypertonic saline and corresponding control rats exhibited fewer attempts to initiate sleep compared to other groups. All sleep-deprived rats exhibited less than 6% of NREM sleep and no REM sleep during the deprivation period.

Figure 3. Average numbers of sleep attempts during consecutive 10 min intervals across a 2-h period for rats that were maintained awake after I.C.V. (n = 12) and I.P. (n = 12) treatments.

Expression and distribution of c-Fos immunoreactive neurones in the MnPN

Immunostaining for c-Fos protein was used as a reflection of neuronal activity (Sagar et al. 1988; Dragunow & Faull, 1989; Herrera & Robertson, 1996) in the MnPN across experimental groups. Treatments with hypertonic saline and Ang-II evoked elevated Fos expression in MnPN neurones of all experimental rats (Figs 4 and 5). Numbers of Fos-IRNs in the MnPN of treated animals were significantly increased compared to respective control animals in both spontaneously sleeping and sleep-deprived groups of rats (all P < 0.05), although the extent of the MnPN Fos-IR across the experimental groups showed sleep–waking state-related variations (Fig. 6). The number of Fos-IRNs in i.p. hypertonic saline and i.c.v. Ang-II sleeping rats were significantly higher than in sleep-deprived animals that were treated the same way (P < 0.05). In normal saline-treated rats (controls), the number of Fos-IRNs in rostral MnPN of sleeping rats was significantly lower than in sleep-deprived rats (P < 0.05) while caudal MnPN of these rats showed similar cell counts.

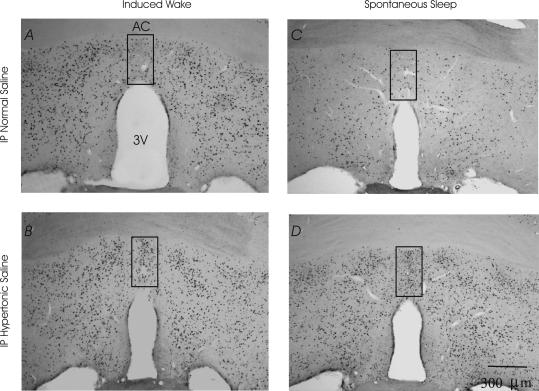

Figure 4. Expression of c-fos in the caudal MnPN.

A, i.p. normal saline induced waking; B, i.p. hypertonic saline induced waking; C. i.p. normal saline spontaneously sleeping; D, i.p. hypertonic saline spontaneously sleeping rats. Grids indicate the area in which cell counts were performed.

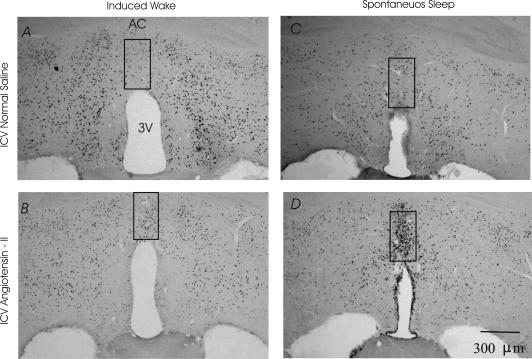

Figure 5. Expression of c-fos in the caudal MnPN.

A, i.c.v. normal saline induced waking; B, i.c.v. Ang-II induced waking; C, i.c.v. normal saline spontaneously sleeping; D, i.c.v. Ang-II spontaneously sleeping rats.

ANOVA indicated that i.p. injection did not cause significant changes in the extent of MnPN neuronal activation; expression of c-fos in the MnPN of i.p. normal saline rats was similar to that in i.c.v. normal saline rats in both conditions of spontaneous sleep and sleep deprivation (see Fig. 6).

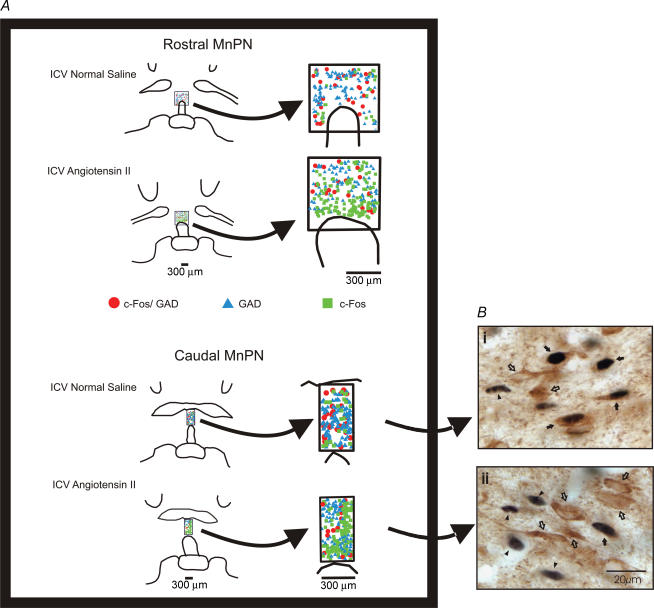

Extent of Fos + GAD immunoreactivity in MnPN neurones

To determine whether MnPN neurones activated in response to sleep and during activation of central drinking and osmoregulatory circuits have the same neurotransmitter phenotype, Fos + GAD cell counts in the MnPN were compared between i.c.v. Ang-II, i.c.v. normal saline and untreated sleeping rats. These groups of animals were chosen for comparison because of having similar total sleep amounts (see in Table 1). Examples of the distribution of Fos-IR, GAD-IR and Fos + GAD-IR neurones within MnPN counting grids are shown in Fig. 7A. Examples of individually stained neurones are shown in Fig. 7B. As presented in Fig. 8A, i.c.v. Ang-II rats showed dramatically higher numbers of Fos-IRNs compared to i.c.v. normal saline and untreated control rats (P < 0.05). However, the numbers of Fos + GAD-IRNs in these animals did not differ significantly (Fig. 8B); a majority of the Fos-IRNs in the MnPN of i.c.v. Ang-II rats were located in the neurones that did not colocalize GAD (Figs 7A and 8C).

Figure 7. Distribution and examples of Fos-IR, GAD-IR, and Fos + GAD neurons in MnPN counting grids.

A, line drawings showing the distribution of Fos single-labelled, GAD single-labelled and Fos + GAD double-labelled neurones located in counting grids for the rostral and caudal MnPN from one i.c.v. normal saline and one i.c.v. Ang-II spontaneously sleeping rat. B, examples of Fos single-labelled (filled arrowheads), GAD single-labelled (open arrows) and Fos + GAD double-labelled (filled arrows) neurones in the MnPN of one i.c.v. normal saline (i) and one i.c.v. Ang-II (ii) spontaneously sleeping rat. The Fos protein is stained black and confined to the nucleus. The GAD-IRNs are stained brown and the staining is evident throughout the soma and the proximal dendrites.

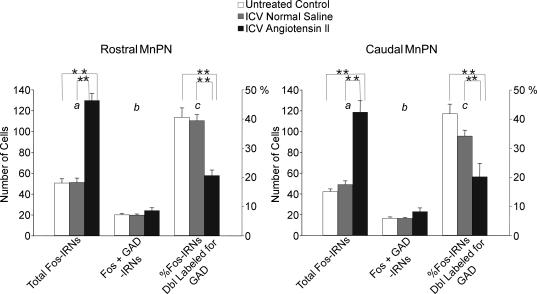

Figure 8. Mean numbers of total Fos-IRNs (a), Fos + GAD-IRNs (b) and the mean percentage of Fos-IRNs that were double labelled for GAD-IR (c) in the rostral and caudal MnPN of untreated, I.C.V. normal saline and I.C.V. Ang-II spontaneously sleeping rats.

ANOVA for total Fos IRNs indicated a significant effect of experimental condition in both the rostral (F2,15 = 138.4; P < 0.001) and caudal (F2,15 = 71.3; P < 0.001) MnPN. There was no significant effect of experimental condition on the number of Fos + GAD IRNs. However, there was a significant effect of experimental condition on the percentage of Fos IRNs double labelled for GAD in both the rostral (F2,15 = 28.7; P < 0.001) and caudal MnPN (F2,15 = 52.2; P < 0.001). Individual group mean differences are indicated by asterisks (**P < 0.001; Newman-Keuls).

As presented in Table 2, i.p. hypertonic saline rats that were allowed spontaneous sleep after treatment showed no significant difference in the number of Fos + GAD-IRNs in the MnPN compared to i.p. normal saline animals. Administration of hypertonic saline significantly increased the total number of Fos-single IRNs (P < 0.05; see Fig. 6), but only 20% of the MnPN neurones expressing Fos-IR were double labelled for GAD (Table 2).

Neither i.p. hypertonic saline nor i.c.v. Ang-II caused significant changes in the total number of GAD IRNs in the MnPN (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean numbers of single GAD-IRNs in the MnPN of spontaneously sleeping I.P. hypertonic saline and respective control rats, spontaneously sleeping I.C.V. angiotensin-II and respective control rats and spontaneously sleeping untreated rats

| Experimental Groups | Rostral MnPN | Caudal MnPN |

|---|---|---|

| i.p. hypertonic saline (n = 6) | 94.7 ± 1.6 | 87.6 ± 2.6 |

| i.p. normal saline (n = 6) | 93.9 ± 2.9 | 89.0 ± 3.4 |

| i.c.v. angiotensin II (n = 6) | 96.9 ± 4.9 | 89.9 ± 6.1 |

| i.c.v. normal saline (n = 6) | 94.8 ± 4.7 | 80.9 ± 6.1 |

| Untreated rats (n = 6) | 95.5 ± 5.7 | 89.4 ± 3.4 |

Discussion

The present study was designed to determine (1) whether or not activation of MnPN neurones in response to hypertonic saline and Ang-II is modified by sleep–waking state and (2) if MnPN neurones expressing Fos-IR during sleep and during activation of central drinking and osmoregulatory circuits are the same or different neuronal populations.

Our results demonstrate that administration of hypertonic saline and Ang-II significantly increased the number of Fos-IRNs in the MnPN of awake rats, compared to awake controls. The activation of MnPN neurones by hypertonic saline and Ang-II was not diminished in animals that were permitted to sleep during the post-treatment period. This indicates that MnPN neurones respond to the activation of central drinking and osmoregulatory circuits in a state-independent manner, and that MnPN-mediated regulatory responses to such challenges (e.g. release of vasopressin) may persist during sleep.

Increases in circulating angiotensin, as occurs during hypovolaemic challenge, act via the subfornical organ (SFO) to stimulate drinking (see McKinley et al. 2004). The pattern of activation of angiotensin-sensitive drinking circuits in the brain produced by i.c.v. Ang-II, as performed in this study, may be different from that occurring in response to systemic Ang-II release. However, Ang-II sensitive neurones in the MnPN are critically involved in drinking responses evoked by circulating Ang-II, mediated by excitatory angiotensinergic projections from the SFO to the MnPN (Tanaka et al. 1987; Tanaka, 1989; Tanaka & Nomura, 1993). Given the proximity of the MnPN to the third ventricle, i.c.v. Ang-II can be expected to activate these critical Ang-II sensitive neurones in this nucleus.

Both i.p. hypertonic saline and i.c.v. Ang-II in the present study induced Fos-IR in neurones located dorsal and ventral to the anterior commissure, and the Fos-IR was restricted to the midline of the dorsal and ventral parts of the MnPN. Findings of the present study agree with previously published reports. Expression of c-fos in MnPN in response to systemic administration of hypertonic saline and Ang-II (Oldfield et al. 1991a; Herbert et al. 1992; Oldfield et al. 1994; Xu & Herbert, 1995, 1996; Xu et al. 2003), or 24-h water deprivation (McKinley et al. 1994) was seen in neurones located in the midline of the dorsal and ventral parts of the MnPN. The same regions were activated during acute hydromineral challenge evoked by furosemide-induced fluid and electrolyte depletion (Grob et al. 2003). The MnPN counting grids used in the present study were positioned ventral to the anterior commissure; cells dorsal to the commissure were not counted.

Excitatory responses to the application of hypertonic saline and Ang-II are commonly observed in MnPN neurones and electrophysiological data corroborate findings with c-Fos immunostaining. Experiments in sheep (McAllen et al. 1990) and rats (Honda et al. 1990) have indicated that a majority of MnPN neurones increase their electrical activity in response to systemic or local infusions of hypertonic solutions. Excitation of MnPN neurones occurs with Ang-II chemical stimulation of the SFO, and this effect is abolished by iontophoretic application of saralasin, a specific Ang-II antagonist, into the MnPN (Tanaka et al. 1987; Tanaka, 1989).

i.p. hypertonic saline and i.c.v. Ang-II in the present study activated MnPN neurones during both sleep and wakefulness, compared to controls. However, the number of Fos-IRNs was significantly increased in treated animals that were permitted to sleep, compared to similarly treated animals that were kept awake. This finding could reflect the dual activation of separate populations of sleep-related neurones and osmosenstive neurones during sleep in hypertonic saline- and Ang-II-treated animals.

i.p. injection of hypertonic saline resulted in significant increases in c-fos expression in the MnPN, compared to control rats receiving i.p. injections of normal saline. Hypertonic saline also caused sleep disruption, including delayed sleep onset, sleep fragmentation and loss of both non-REM and REM sleep. Sleep disturbance persisted during the entire 2 h recording period. Hypertonic saline-treated rats also required fewer stimuli to maintain sleep deprivation compared to normal saline controls. While normal saline-treated rats exhibited significantly more sleep than hypertonic saline-treated rats, i.p. injection had some sleep disruption effects. Normal saline control rats exhibited increased sleep latency and reduced sleep time during the first 30–45 min post-injection, compared to other control groups (i.c.v. normal saline and untreated control rats).

Fos expression in the MnPN of i.p. hypertonic saline rats may be considered to be related to stress of injection. Two points argue against this: (1) i.p. hypertonic saline rats had an appropriate control – control rats were also exposed to the non-specific effects of i.p. injection; and (2) a previous report demonstrates that a similar pattern of Fos-IR in MnPN cells was induced by both i.p. and intravenous applications of hypertonic saline (Xu et al. 2003). These authors concluded that the increased c-fos expression in the MnPN of i.p. treated rats could be interpreted as being the result of osmotic stimulation but not the stress caused by injection-related pain.

i.c.v. Ang-II resulted in only small and insignificant changes in sleep latency and total sleep time. Differential effects of i.c.v. Ang-II versusi.p. hypertonic saline on sleep latency were undoubtedly due, in part, to use of a remote injection method, which did not involve handling animals during Ang-II administration. While i.c.v. Ang-II did not significantly alter total sleep time, sleep architecture was affected, with significant reductions in REM sleep in Ang-II-treated rats. To our knowledge, this is the first description of an acute REM sleep-suppressing effect of i.c.v. Ang-II.

The difference in REM sleep amounts between i.c.v. Ang-II and spontaneously sleeping control rats could have differentially influenced c-fos expression in the MnPN neurones of these animals. We have previously reported that the extent of Fos-IR in the MnPN is positively correlated with the total amount of preceding sleep (Gong et al. 2004). However, it is not clear whether sleep-induced Fos-IR in MnPN cells is related to NREM or REM sleep. REM sleep reduction evoked by i.c.v. Ang-II could cause a decrease in Fos-IR in MnPN GABAergic neurones. However, our results demonstrate that the total number of Fos + GAD IRNs did not change in i.c.v. Ang-II versusi.c.v. normal saline and untreated spontaneously sleeping rats. Alternatively, REM sleep suppression in i.c.v. Ang-II rats could activate a population of MnPN non-GABAergic neurones. The relationship of c-fos expression in MnPN neurones with the regulation of NREM versus REM sleep remains to be determined.

We have previously shown that sleep-related fos-IR in the MnPN is expressed in GABAergic neurones (Gong et al. 2004). To determine if the population of MnPN neurones activated in response to excitation of central drinking and osmoregulatory circuits is similar to or different from neurones activated during sleep, we quantified Fos- and GAD-IR in spontaneously sleeping Ang-II-treated versus spontaneously sleeping i.c.v. saline and untreated control rats. These groups of animals were chosen for comparison because of having similar total sleep amounts. In Ang-II rats, only 15% of MnPN neurones expressing Fos-IR were double-labelled for GAD. In control rats, 40% of Fos-IR neurones were also positive for GAD-IR. In fact, the number of Fos + GAD-IR neurones was similar in Ang-II-treated and control rats, but the percentage of double-labelled cells was reduced in the experimental group due to significant increases in the number of Fos single-labelled neurones. Similarly, there was no significant difference in the number of Fos + GAD-IRNs in the MnPN of hypertonic saline rats compared to controls, but the number of Fos single IRNs was significantly elevated in treated rats.

The increase in single Fos staining in Ang-II and hypertonic saline-treated rats suggests activation of an additional, non-GABAergic neuronal population. This is consistent with a previous report demonstrating that Fos-IR evoked by furosemide-induced fluid and electrolyte depletion occurs primarily in MnPN glutamatergic neurones (Grob et al. 2003). Local application of hypertonic solution to the organum vasculosum lamina terminalis region evokes excitatory responses in neurosecretory neurones in the supraoptic nucleus (Richard & Bourque, 1995). These findings support the hypothesis that hypertonic saline and Ang-II activate non-GABAergic neurones in the MnPN.

In a previous publication (Gong et al. 2004), we reported that > 70% of MnPN neurones expressing sleep-related Fos-IR were also double-labelled for GAD. In the current study, < 50% of Fos-IR neurones in sleeping control rats were also GAD-IR. One factor that could account for these differences was the use of a monoclonal antibody against GAD67 in the present study versus the use of a polyclonal antibody against GAD67 and GAD65 in our previous report. Use of the polyclonal antibody may have yielded more non-specific staining, resulting in an overestimation of the number of GAD+ neurones in the MnPN. Alternatively; the MnPN may contain subpopulations of GABAergic neurones that express predominately GAD67 or GAD65. The monoclonal antibody used in the present study may have stained only a subset of MnPN GABAergic neurones that were labelled by the polyclonal antibody.

In the present study, we did not analyse changes in Fos + GAD population of MnPN in sleep-deprived versus spontaneously sleeping rats. However, previous reports demonstrated that the number of Fos + GAD IRNs in spontaneously sleeping rats is significantly higher than in sleep-deprived animals (Gong et al. 2004; Modirrousta et al. 2004).

In our original report of sleep-related Fos-IR in the MnPN, we reported low levels of Fos+ neurones in animals that were sleep deprived compared to spontaneously sleeping rats (Gong et al. 2000). The present study shows high numbers of Fos-IRNs in the MnPN of sleep-deprived rats. The reasons for this discrepancy are not clear. In the two studies, animals were killed at similar circadian times and the methods and duration of sleep deprivation were similar. Significant numbers of Fos-IRNs in the MnPN of awake rats, with the number of Fos-IR neurones being similar to or higher in sleep-deprived versus sleeping rats, have been also reported in previous studies (Pompeiano et al. 1992; Modirrousta et al. 2004; Peterfi et al. 2004). We have observed activation of Fos in the MnPN of awake rats exposed to elevated environmental temperatures and in rats subjected to restraint stress (unpublished findings). Therefore, activation of Fos-IR can occur in MnPN neurones during waking under some physiological and/or behavioural conditions. As demonstrated here, acute osmotic challenge can strongly activate waking fos expression in the MnPN, predominately in non-GABAergic neurones. Other stimuli that can alter MnPN neuronal activity include changes in blood pressure (Shi et al. 2005), fever and immune system activation (Ek et al. 2000; Oka et al. 2000; Ekimova, 2003) and hyperthermia (Scammel et al. 1993; Vellucci & Parrott, 1994, 1995). The extent to which similar or different subpopulations of MnPN neurones are activated by these different stimuli remains to be determined.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Keng-Tee Chew for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs and NIH grant MH63323.

References

- Armstrong WE, Tian M, Wong H. Electron microscopic analysis of synaptic inputs from the median preoptic nucleus and adjacent regions to the supraoptic nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373:228–239. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960916)373:2<228::AID-CNE6>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho A, Phillips MI. Horseradish peroxidase study in rat of the neural connections of the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis. Neurosci Lett. 1981;25:201–204. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M, Faull R. The use of c-fos as a metabolic marker in neuronal pathway tracing. J Neurosci Meth. 1989;29:261–265. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ek M, Arias C, Sawchenko P, Ericsson-Dahlstrand A. Distribution of the EP3 prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype in the rat brain: relationship to sites of interleukin-1-induced cellular responsiveness. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:5–20. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<5::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekimova I. Changes in the metabolic activity of neurons in the anterior hypothalamic nuclei in rats during hyperthermia, fever, and hypothermia. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2003;33:455–460. doi: 10.1023/a:1023459100213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner TW, Stricker EM. Impaired drinking responses of rats with lesions of nucleus medianus: Circadian dependence. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:R224–R230. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1985.248.2.R224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H, McGinty D, Guzman-Marin R, Chew KT, Stewart D, Szymusiak R. Activation of c-fos. GABAergic neurons in the preoptic area during sleep and in response to sleep deprivation. J Physiol. 2004;556:935–946. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.056622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong H, Szymusiak R, King J, Steininger T, McGinty D. Sleep-related c-Fos protein expression in the preoptic hypothalamus: effects of ambient warming. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R2079–R2088. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grob M, Trottier JF, Drolet G, Mouginot D. Characterization of the neurochemical content of neuronal populations of the lamina terminalis activated by acute hydromineral challenge. Neuroscience. 2003;122:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamura M, Nunez DJ, Leng G, Emson PC, Kiyama H. c-fos may code for a common transcription factor within the hypothalamic neural circuits involved in osmoregulation. Brain Res. 1992;572:42–51. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90448-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert J, Forsling ML, Howes SR, Stacey PM, Shiers HM. Regional expression of c-fos antigen in the basal forebrain following intraventricular infusions of angiotensin and its modulation by drinking either water or saline. Neuroscience. 1992;51:867–882. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90526-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera DG, Robertson HA. Activation of c-fos in the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;50:83–107. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R, Negoro H, Dyball REJ, Higuchi T, Takano S. The osmoreceptor complex in the rat: Evidence for interactions between the supraoptic and other diencephalic nuclei. J Physiol. 1990;431:225–241. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krout K, Kawano J, Mettenleiter T, Loewy A. CNS inputs to the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the rat. Neuroscience. 2002;110:73–92. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind RW, Johnson AK. Subfornical organ-median preoptic connections and drinking and pressor responses to angiotensin II. J Neurosci. 1982;2:1043–1051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-08-01043.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind RW, Swanson LW, Ganten D. Organization of angiotensin II immunoreactive cells and fibers in the rat central nervous system: An immunohistochemical study. Neuroendocrinology. 1985;40:2–24. doi: 10.1159/000124046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig M, Callahan MF, Landgraf R, Johnson AK, Morris M. Neural input modulates osmotically stimulated release of vasopressin into the supraoptic nucleus. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:E787–E792. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.5.E787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllen RM, Pennington GL, McKinley MJ. Osmoresponsive units in sheep median preoptic nucleus. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:R593–R600. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.3.R593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Cairns MJ, Denton DA, Egan G, Mathai ML, Uschakokv A, Wade JD, Weisinger RS, Oldfield BJ. Physiological and pathophysiological infuences on thirst. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:795–803. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Gerstberger R, Mathai ML, Oldfield BJ, Schmid H. The lamina terminalis and its role in fluid and electrolyte homeostasis? J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6:289–301. doi: 10.1054/jocn.1998.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Hards DK, Oldfield BJ. Identification of neural pathways activated in dehydrated rats by means of Fos-immunohistochemistry and neural tracing. Brain Res. 1994;653:305–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinley MJ, Pennington GL, Oldfield BJ. Anterior wall of the third ventricle and dorsal lamina terminalis: headquartes for control of body fluid homeostasis? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb02823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manciapane ML, Thrasher TN, Keil LC, Simpson JB, Ganong WF. Deficits in drinking and vasopressin secretion after lesions of the nucleus medianus. Neuroendocrinology. 1983;37:73–77. doi: 10.1159/000123518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modirrousta M, Mainville L, Jones B. GABAergic neurons with alpha2-adrenergic receptors in basal forebrain and preoptic area express c-Fos during sleep. Neuroscience. 2004;129:803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka T, Oka K, Scammell T, Lee C, Kelly J, Nantel F, Elmquist J, Saper C. Relationship of EP (1–4) prostaglandin receptors with rat hypothalamic cell groups involved in lipopolysaccharide fever responses. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:20–32. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<20::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BJ, Badoer E, Hards DK, McKinley MJ. Fos production in retrogradely labeled neurons of the lamina terminalis following intravenous infusion of either hypertonic saline or angiotensin II. Neuroscience. 1994;60:255–262. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BJ, Bicknell RJ, McAllen RM, Weisinger RS, McKinley MJ. Intravenous hypertonic saline induces Fos immunoreactivity in neurons throughout the lamina terminalis. Brain Res. 1991a;561:151–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90760-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BJ, Hards DK, McKinley MJ. Projections from the subfornical organ to the supraoptic nucleus in the rat: ultrastructural identification of an interposed synapse in the median preoptic nucleus using a combination of neuronal tracers. Brain Res. 1991b;558:13–19. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterfi Z, Churchill L, Hajdu I, Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM, Parducz A. Fos-immunoreactivity in the hypothalamus: dependency on the diurnal rhythm, sleep, gender, and estrogen. Neuroscience. 2004;124:695–707. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompeiano M, Cirelli C, Tononi G. Effects of sleep deprivation on fos-like immunoreactivity in the rat brain. Arch Ital Biol. 1992;130:325–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard D, Bourque CW. Synaptic control of rat supraoptic neurons during osmotic stimulation of the organum vasculosum lamina terminalis in vitro. J Physiol. 1995;489:567–577. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar SM, Sharp FR, Curran T. Expression of c-fos protein in brain: metabolic mapping at the cellular level. Science. 1988;240:1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.3131879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scammell T, Price K, Sagar S. Hyperthermia induces c-fos expression in the preoptic area. Brain Res. 1993;618:303–307. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp FR, Sagar SM, Hicks K, Lowenstein D, Hisanaga K. c-fos mRNA, Fos, and Fos-related antigen induction by hypertonic saline and stress. J Neurosci. 1991;11:2321–2331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-08-02321.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Zhang Y, Morrissey P, Yao J, Xu Z. The association of cardiovascular responses with brain c-fos expression after central carbachol in the near-term ovine fetus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005 doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300738. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suntsova N, Szymusiak R, Alam MN, Guzman-Marin R, McGinty D. Sleep–waking discharge patterns of median preoptic nucleus neurons in rats. J Physiol. 2002;543:665–667. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.023085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J. Involvement of the median preoptic nucleus in the regulation of paraventricular vasopressin neurons by the subfornical organ in the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1989;76:47–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00253622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J, Nomura M. Involvement of neurons sensitive to angiotensin II in the median preoptic nucleus in the drinking response induced by angiotensin II activation of the subfornical organ in rats. Exp Neurol. 1993;119:235–239. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J, Saito H, Kaba H. Subfornical organ and hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus connections with median preoptic nucleus neurons: An electrophysiological study in the rat. Exp Brain Res. 1987;68:579–535. doi: 10.1007/BF00249800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellucci S, Parrott R. Hyperthermia-associated changes in Fos protein in the median preoptic and other hypothalamic nuclei of the pig following intravenous administration of prostaglandin E2. Brain Res. 1994;646:165–169. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellucci S, Parrott R. Prostaglandin-dependent c-Fos expression in the median preoptic nucleus of pigs subjected to restraint: correlation with hyperthermia. Neurosci Lett. 1995;198:49–51. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11938-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MI, Hatton GI. Collateral input to the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei in rat. I. Afferents from the subfornical organ and the anteroventral third ventricle region. Brain Res Bull. 1990;24:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(90)90210-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin LD, Gruber KA, Johnson AK. Changes in magnocellular-neurohypophyseal vasopressin following anteroventral third-ventricle (AV3V) lesions. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1986;7:70–75. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198600087-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin LD, Mitchell D, Ganten D, Johnson AK. The supraoptic nucleus: afferents from areas involved in control of body fluid homeostasis. Neuroscience. 1989;28:573–584. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Herbert J. Regional suppression by the lesions in the anterior third ventricle of c-fos expression induced by either angiotensin II or hypertonic saline. Neuroscience. 1995;67:135–147. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00050-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Herbert J. Effects of unilateral or bilateral lesions within the anteroventral third ventricular region on fos expression induced by dehydration or angiotensin II in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus. Brain Res. 1996;713:36–43. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01462-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Torday J, Yao L. Functional and anatomic relationship between cholinergic neurons in the median preoptic nucleus and the supraoptic cells. Brain Res. 2003;964:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03800-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]