Abstract

We examined the relationship between changes in cardiac output  and middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity (MCA Vmean) in seven healthy volunteer men at rest and during 50% maximal oxygen uptake steady-state submaximal cycling exercise. Reductions in

and middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity (MCA Vmean) in seven healthy volunteer men at rest and during 50% maximal oxygen uptake steady-state submaximal cycling exercise. Reductions in  were accomplished using lower body negative pressure (LBNP), while increases in

were accomplished using lower body negative pressure (LBNP), while increases in  were accomplished using infusions of 25% human serum albumin. Heart rate (HR), arterial blood pressure and MCA Vmean were continuously recorded. At each stage of LBNP and albumin infusion

were accomplished using infusions of 25% human serum albumin. Heart rate (HR), arterial blood pressure and MCA Vmean were continuously recorded. At each stage of LBNP and albumin infusion  was measured using an acetylene rebreathing technique. Arterial blood samples were analysed for partial pressure of carbon dioxide tension (Pa,CO2. During exercise HR and

was measured using an acetylene rebreathing technique. Arterial blood samples were analysed for partial pressure of carbon dioxide tension (Pa,CO2. During exercise HR and  were increased above rest (P < 0.001), while neither MCA Vmean nor Pa,CO2 was altered (P > 0.05). The MCA Vmean and

were increased above rest (P < 0.001), while neither MCA Vmean nor Pa,CO2 was altered (P > 0.05). The MCA Vmean and  were linearly related at rest (P < 0.001) and during exercise (P = 0.035). The slope of the regression relationship between MCA Vmean and

were linearly related at rest (P < 0.001) and during exercise (P = 0.035). The slope of the regression relationship between MCA Vmean and  at rest was greater (P = 0.035) than during exercise. In addition, the phase and gain between MCA Vmean and mean arterial pressure in the low frequency range were not altered from rest to exercise indicating that the cerebral autoregulation was maintained. These data suggest that the

at rest was greater (P = 0.035) than during exercise. In addition, the phase and gain between MCA Vmean and mean arterial pressure in the low frequency range were not altered from rest to exercise indicating that the cerebral autoregulation was maintained. These data suggest that the  associated with the changes in central blood volume influence the MCA Vmean at rest and during exercise and its regulation is independent of cerebral autoregulation. It appears that the exercise induced sympathoexcitation and the change in the distribution of

associated with the changes in central blood volume influence the MCA Vmean at rest and during exercise and its regulation is independent of cerebral autoregulation. It appears that the exercise induced sympathoexcitation and the change in the distribution of  between the cerebral and the systemic circulation modifies the relationship between MCA Vmean and

between the cerebral and the systemic circulation modifies the relationship between MCA Vmean and  .

.

Cerebral autoregulation maintains cerebral blood flow constant over a range of arterial pressures from 60 to 150 mmHg (Paulson et al. 1990). In humans, measurements of middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity (MCA Vmean) provide an index of the cerebral blood flow (Ide & Secher, 2000; Van Lieshout et al. 2003). In conditions where MCA Vmean was reduced or increased by 30 Torr lower body negative pressure (LBNP) (Zhang et al. 1998b) and head-up tilt (Jorgensen et al. 1993), or mild and moderate exercise (Brys et al. 2003; Ogoh et al. 2005b), respectively, central blood volume and cardiac output  were also decreased or increased, respectively. These changes in MCA Vmean occurred without changes in arterial carbon dioxide tension (Pa,CO2) or cerebral autoregulation. Van Lieshout et al. (2001) confirmed the relationship between

were also decreased or increased, respectively. These changes in MCA Vmean occurred without changes in arterial carbon dioxide tension (Pa,CO2) or cerebral autoregulation. Van Lieshout et al. (2001) confirmed the relationship between  , MCA Vmean and central blood volume when they demonstrated that the MCA Vmean was decreased in association with the reduction in

, MCA Vmean and central blood volume when they demonstrated that the MCA Vmean was decreased in association with the reduction in  that occurs when changing postural positions from supine to standing. This reduction in MCA Vmean was present even though mean arterial pressure (MAP) was increased.

that occurs when changing postural positions from supine to standing. This reduction in MCA Vmean was present even though mean arterial pressure (MAP) was increased.

During exercise the competition for perfusion between active and inactive skeletal muscle, brain and other organ beds is regulated by the sympathetic nervous system (Rowell, 1993). For example, during progressive changes in exercise workloads, from rest to maximal exercise, progressive sympathoexcitation occurs (Hartley et al. 1972) resulting in an increasing proportional distribution of the  to the active skeletal muscles (Rowell, 1993). It was found that when healthy subjects performed one-legged exercise MCA Vmean was increased by 20% and was maintained when they performed two-legged exercise (Hellstrom et al. 1997). However, in patients with heart failure, one-legged exercise did not increase MCA Vmean and two-legged exercise resulted in a decreased MCA Vmean (Hellstrom et al. 1997). When the increase in

to the active skeletal muscles (Rowell, 1993). It was found that when healthy subjects performed one-legged exercise MCA Vmean was increased by 20% and was maintained when they performed two-legged exercise (Hellstrom et al. 1997). However, in patients with heart failure, one-legged exercise did not increase MCA Vmean and two-legged exercise resulted in a decreased MCA Vmean (Hellstrom et al. 1997). When the increase in  was reduced by β1-blockade (Ide et al. 1998, 2000; Dalsgaard et al. 2004), or atrial fibrillation (Ide et al. 1999), the increase in MCA Vmean during bicycling exercise was reduced. These findings further indicate that

was reduced by β1-blockade (Ide et al. 1998, 2000; Dalsgaard et al. 2004), or atrial fibrillation (Ide et al. 1999), the increase in MCA Vmean during bicycling exercise was reduced. These findings further indicate that  is an important factor in establishing the MCA Vmean to be regulated by cerebral autoregulation.

is an important factor in establishing the MCA Vmean to be regulated by cerebral autoregulation.

We hypothesized that the MCA Vmean that is regulated by cerebral autoregulation is directly related to  at rest and during exercise. We further hypothesized that the relationship established between MCA Vmean and

at rest and during exercise. We further hypothesized that the relationship established between MCA Vmean and  at rest is reduced during exercise. To test these hypotheses, we manipulated

at rest is reduced during exercise. To test these hypotheses, we manipulated  at rest and during exercise by using LBNP of 8 and 16 Torr and infusions of albumin to decrease and increase central blood volume, respectively.

at rest and during exercise by using LBNP of 8 and 16 Torr and infusions of albumin to decrease and increase central blood volume, respectively.

Methods

Seven men (mean ± s.e.m.: age 26 ± 1 years; height 180 ± 3 cm; weight 89 ± 6 kg) were recruited for participation in the present study. All subjects were free of any known cardiovascular and pulmonary disorders and were not using prescribed or over the counter medications. Each subject provided written informed consent, which conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by The University of North Texas Health Science Center Institutional Review Board. Subjects were requested to abstain from caffeinated beverages for 12 h and strenuous physical activity and alcohol intake for at least a day prior to their study. Before any experiments were performed each subject visited the laboratory for familiarization with the measurement techniques and the experimental protocol. All experiments were conducted at a constant room temperature (25.1 ± 0.3°C).

Maximal exercise

On experimental day 1, each subject performed a maximal incremental load test to volitional fatigue in a 70 deg back-supported semirecumbent position by cycling on an electronically braked ergometer placed within the LBNP box for determining the experimental workload. This test served as the initial screening test and provided evidence of suitability for the study. Before the exercise test, the subject's resting blood pressure and 12-lead electrocardiogram were recorded in the seated and standing positions. The cycle workload was set at 50 W for initial 2 min and was increased 30 W each minute to exhaustion. Criteria for attainment of maximal oxygen uptake  included the inability to maintain a cycling cadence of 60 r.p.m. accompanied by a respiratory quotient which exceeds 1.10 or a documented plateau of

included the inability to maintain a cycling cadence of 60 r.p.m. accompanied by a respiratory quotient which exceeds 1.10 or a documented plateau of  . Subjects respired through a mouthpiece attached to a low-resistance turbine volume transducer (model VMM E-2 A, Sensor Medics, Anaheim, CA, USA) and mass spectrometry (model MGA1100B, Perkin-Elmer, St Louis, MO, USA) for determination of

. Subjects respired through a mouthpiece attached to a low-resistance turbine volume transducer (model VMM E-2 A, Sensor Medics, Anaheim, CA, USA) and mass spectrometry (model MGA1100B, Perkin-Elmer, St Louis, MO, USA) for determination of  . The experimental protocol was scheduled at least 3 days after the day of the maximal exercise test.

. The experimental protocol was scheduled at least 3 days after the day of the maximal exercise test.

Experimental protocol

After arrival at the laboratory and, after instrumentation, the subjects were positioned in the 70 deg back-supported semirecumbent position with the lower body in the LBNP box. In addition, a mercury-in-silastic strain gauge was placed over the largest part of the subject's forearm for the measurement of forearm blood flow (FBF) using venous occlusion plethysmography. Occlusion cuffs were placed at the subject's wrist and upper arm. The subject was sealed in the LBNP box at the level of the iliac crest with a flexible rubber dam. The electrically braked cycle ergometer placed in the LBNP box was adjusted to each subject's leg length. During exercise full extension of the leg was more than 20 deg above the horizontal plane of hip.

At rest two pressures, 8 Torr (LB8) and 16 Torr (LB16), of LBNP were applied to reduce central blood volume. After data collection at rest, the subjects performed steady-state cycling at 50% (108 ± 23 W) with LBNP applied at 8 and 16 Torr. The same measurements taken at rest and at each pressure of LBNP were obtained during the exercise. Following completion of the exercise protocols with LBNP the subjects rested for 30–40 min to enable haemodynamic recovery from the preceding exercise trial. Subsequently, two discrete infusions of 25% human serum albumin solution were administered via the antecubital vein catheter to raise central venous pressure (CVP) 2.0 ± 0.7 and 2.5 ± 0.4 mmHg, respectively, from the resting value. Before the first infusion protocol, the infusion volume of 25% albumin was 1.15 ± 0.04 ml kg−1 (INF1) and the additional volume was 1.62 ± 0.07 ml kg−1 for second infusion protocol (INF2). After data collection at rest, the subjects performed steady-state leg cycling at 50%

(108 ± 23 W) with LBNP applied at 8 and 16 Torr. The same measurements taken at rest and at each pressure of LBNP were obtained during the exercise. Following completion of the exercise protocols with LBNP the subjects rested for 30–40 min to enable haemodynamic recovery from the preceding exercise trial. Subsequently, two discrete infusions of 25% human serum albumin solution were administered via the antecubital vein catheter to raise central venous pressure (CVP) 2.0 ± 0.7 and 2.5 ± 0.4 mmHg, respectively, from the resting value. Before the first infusion protocol, the infusion volume of 25% albumin was 1.15 ± 0.04 ml kg−1 (INF1) and the additional volume was 1.62 ± 0.07 ml kg−1 for second infusion protocol (INF2). After data collection at rest, the subjects performed steady-state leg cycling at 50% . During the resting and exercise experiments, heart rate (HR), arterial blood pressure (ABP) and MCA Vmean were recorded continuously. At each stage of LBNP, or albumin infusion, FBF and

. During the resting and exercise experiments, heart rate (HR), arterial blood pressure (ABP) and MCA Vmean were recorded continuously. At each stage of LBNP, or albumin infusion, FBF and  were measured.

were measured.

Measurements

The HR was monitored with a standard lead II electrocardiogram (Model 78342 A, Hewlett Packard). The ABP was measured by a cannula (1.1 mm i.d., 20 gauge) which was placed in the brachial artery for measurement of the ABP. Another cannula (17 gauge, 65-cm radio-opaque catheter) was introduced into the superior vena cava via the basilica vein for measurement of CVP. Each pressure was recorded with a disposable pressure transducer (Maximum Medical, Athens, TX, USA) positioned at the level of the right atrium in the midaxillary line. In addition, the catheters had extension tubes connected to a slow drip of heparinized normal saline (2 U ml−1). The MCA Vmean was obtained by transcranial Doppler ultrasonography (Multidop X, DWL, Sipplingen, Germany) with a 2-MHz probe placed over the temporal window and fixed with an adjustable headband and adhesive ultrasonic gel (Tensive, Parker Laboratories, Orange, NJ, USA). A venous catheter (1.2 mm i.d., 18 gauge) was inserted into the median antecubital vein for central blood volume expansion by infusing 25% human serum albumin solution.  was estimated by an aceytlene re-breathing technique (Triebwasser et al. 1977). The FBF was determined using venous occlusion plethysmography employing a dual loop mercury-in-silastic strain gauge to determine changes in limb volume (Whitney, 1953). The venous occlusion cuff pressure was set at 40 mmHg, and an arterial occlusion cuff (inflated to 250 mmHg) was used to prevent arterial inflow into the hand during each blood flow measurement. Arterial blood samples were obtained at each condition and stored in ice–water until analysed for Pa,CO2 (Instrumentation Laboratory model no. 1735, Lexington, MA, USA). Cerebral vascular resistance index (CVRi) was expressed as (MAP/MCA Vmean).

was estimated by an aceytlene re-breathing technique (Triebwasser et al. 1977). The FBF was determined using venous occlusion plethysmography employing a dual loop mercury-in-silastic strain gauge to determine changes in limb volume (Whitney, 1953). The venous occlusion cuff pressure was set at 40 mmHg, and an arterial occlusion cuff (inflated to 250 mmHg) was used to prevent arterial inflow into the hand during each blood flow measurement. Arterial blood samples were obtained at each condition and stored in ice–water until analysed for Pa,CO2 (Instrumentation Laboratory model no. 1735, Lexington, MA, USA). Cerebral vascular resistance index (CVRi) was expressed as (MAP/MCA Vmean).

Transfer function analysis

Analog signals of ABP and the spectral envelope of MCA Vmean were sampled at 200 Hz and digitized at 12 bits for off-line analysis. Beat-to-beat MAP and MCA Vmean were obtained by integrating analog signals within each cardiac cycle and linearly interpolated and re-sampled at 2 Hz for spectral analysis (Zhang et al. 1998a). For transfer function analysis, the cross-spectrum between change in MAP and MCA Vmean was estimated and then divided by the autospectrum of MAP. At rest and during exercise transfer function gain and phase were calculated (Zhang et al. 1998a, b; Ogoh et al. 2005a, b).

In addtion, the coherence function was calculated to estimate the fraction of output power (MCA Vmean) that can be linearly related to the input power (MAP) at each frequency. Similarly to a correlation coefficient, it varies between 0 and 1. For this calculation, the 3 min steady-state MAP and MCA Vmean were used at each condition.

Spectral power of MAP, MCA Vmean, mean value of transfer function gain, phase, and coherence function were calculated in the very low (VLF, 0.02–0.07 Hz), low (LF, 0.07–0.20 Hz), and high (HF, 0.20–0.30 Hz) frequency ranges to reflect different patterns of the dynamic pressure–flow relationship (Zhang et al. 1998a, 2002). The ABP fluctuations in the HF range, including those induced by the respiratory frequency, are transferred to MCA Vmean, whereas ABP fluctuations in the LF range are independent of the respiratory frequency and the LF transfer analysis reflects cerebral autoregulation mechanisms (Diehl et al. 1995; Zhang et al. 1998a). Furthermore, the VLF range of both the flow and the pressure variabilities appears to reflect multiple physiological mechanisms that confound interpretation. Thus, we used the LF range for the spectral analysis to identify the dynamic cerebral autoregulation during exercise.

Statistics

Statistical comparisons of physiological variables were made utilizing a repeated-measures two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a 5 × 2 design (condition × exercise). A Student-Newman-Keuls test was employed post hoc when interactions were significant. The relationship between MCA Vmean or FBF and  was described using simple linear regression analysis. These relationships (slope of linear regression) at rest and exercise were compared by using Student's paired t test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and results are presented as means ± s.e.m. Analyses were conducted using SigmaStat (Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA, USA).

was described using simple linear regression analysis. These relationships (slope of linear regression) at rest and exercise were compared by using Student's paired t test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and results are presented as means ± s.e.m. Analyses were conducted using SigmaStat (Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA, USA).

Results

This study involved two protocols designed to alter  by increasing and decreasing central blood volume. One protocol used LBNP to decrease

by increasing and decreasing central blood volume. One protocol used LBNP to decrease  while the second protocol used human serum albumin infusions to increase

while the second protocol used human serum albumin infusions to increase  . In response to LB8 and LB16, the reduction in CVP was 1.5 ± 0.3 and 2.8 ± 0.5 mmHg at rest, and 0.9 ± 0.4 and 2.9 ± 0.4 mmHg during exercise, respectively. In response to the first and second albumin infusions, the increase in CVP was 2.0 ± 0.7 and 2.5 ± 0.4 mmHg at rest, and 3.2 ± 1.0 and 4.9 ± 1.0 mmHg during exercise, respectively.

. In response to LB8 and LB16, the reduction in CVP was 1.5 ± 0.3 and 2.8 ± 0.5 mmHg at rest, and 0.9 ± 0.4 and 2.9 ± 0.4 mmHg during exercise, respectively. In response to the first and second albumin infusions, the increase in CVP was 2.0 ± 0.7 and 2.5 ± 0.4 mmHg at rest, and 3.2 ± 1.0 and 4.9 ± 1.0 mmHg during exercise, respectively.

The haemodynamic changes that occurred at rest and during exercise during the experimental manipulation of central blood volume are presented in Table 1. The HR tended to increase during LBNP at rest (P > 0.05) and was increased during LBNP and exercise. The  was reduced during LBNP as a result of a larger reduction in stroke volume despite the increase in HR. The HR gradually increased during the infusions of albumin at rest and during exercise (P < 0.05) resulting in increases in

was reduced during LBNP as a result of a larger reduction in stroke volume despite the increase in HR. The HR gradually increased during the infusions of albumin at rest and during exercise (P < 0.05) resulting in increases in  because both HR and stroke volume increased. Thus, the changes in

because both HR and stroke volume increased. Thus, the changes in  were larger during the infusion of albumin than those that occurred during LBNP. The changes in central blood volume produced by LB8, LB16 and infusions 1 and 2 did not affect MAP at rest or during exercise. The Pa,CO2 remained constant throughout all experimental conditions. However, MCA Vmean tended to decrease during LBNP and increase during the infusions of albumin, both at rest and during exercise.

were larger during the infusion of albumin than those that occurred during LBNP. The changes in central blood volume produced by LB8, LB16 and infusions 1 and 2 did not affect MAP at rest or during exercise. The Pa,CO2 remained constant throughout all experimental conditions. However, MCA Vmean tended to decrease during LBNP and increase during the infusions of albumin, both at rest and during exercise.

Table 1.

Haemodynamic responses to lower body negative pressure (LBNP) and the infusion of albumin at rest and during exercise

| LBNP | Infusion of albumin | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB16 | LB8 | Control | INF1 | INF2 | ||

| HR(bpm) | Rest | 74 ± 5 | 70 ± 4 | 66 ± 3 | 82 ± 6†‡* | 84 ± 7†‡* |

| Exercise | 130 ± 6# | 123 ± 6# | 114 ± 3†‡# | 129 ± 5*# | 133 ± 4‡*# | |

| MAP (mmHg) | Rest | 99 ± 4 | 96 ± 3 | 96 ± 3 | 92 ± 4† | 91 ± 3† |

| Exercise | 106 ± 4 | 104 ± 5# | 109 ± 5# | 105 ± 4# | 106 ± 5# | |

| MCA Vmean(cm s−1) | Rest | 62 ± 4 | 63 ± 4 | 66 ± 4 | 71 ± 4†‡* | 73 ± 4†‡* |

| Exercise | 68 ± 3# | 70 ± 3# | 70 ± 5 | 74 ± 4 | 74 ± 4 | |

(l min−1) (l min−1) |

Rest | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 6.5 ± 0.3† | 8.2 ± 0.6†‡* | 8.5 ± 0.4†‡* |

| Exercise | 13.7 ± 1.1# | 14.1 ± 1.1†# | 14.7 ± 1.0†# | 16.5 ± 1.3†‡*# | 18.5 ± 1.2†‡**§# | |

| Pa,co2 | Rest | 40 ± 1 | 39 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 |

| Exercise | 41 ± 1 | 42 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | |

| CVRi (mmHg s cm−1) | Rest | 1.62 ± 0.11 | 1.55 ± 0.11 | 1.49 ± 0.10 | 1.31 ± 0.08†‡* | 1.27 ± 0.07†‡* |

| Exercise | 1.59 ± 0.10 | 1.50 ± 0.08 | 1.61 ± 0.13 | 1.45 ± 0.08*# | 1.46 ± 0.11*# | |

Values are means ± s.e.m.; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MCA Vmean, middle cerebral artery blood velocity;  , cardiac output; ,arterial carbon dioxide tension; CVRi, cerebral vascular resistance index; LB8, 8 Torr LBNP; LB16, 16 Torr LBNP; INF1, first albumin infusion; INF2, second albumin infusion.

, cardiac output; ,arterial carbon dioxide tension; CVRi, cerebral vascular resistance index; LB8, 8 Torr LBNP; LB16, 16 Torr LBNP; INF1, first albumin infusion; INF2, second albumin infusion.

Different from control, P < 0.05;

different from LB16, P < 0.05;

different from LB8, P < 0.05;

different from INF1, P < 0.05;

different from rest.

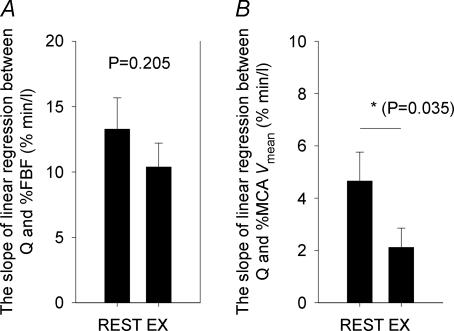

The response of the FBF and MCA Vmean to the changes in  are summarized in Figs 1 and 2. Although the FBF increased from rest to exercise by 30.4 ± 4.9% (P < 0.001), the FBF response to the changes in

are summarized in Figs 1 and 2. Although the FBF increased from rest to exercise by 30.4 ± 4.9% (P < 0.001), the FBF response to the changes in  was the same during exercise as that observed at rest. The linear relationships between FBF and

was the same during exercise as that observed at rest. The linear relationships between FBF and  were statistically significant at rest and during exercise (Fig. 1). In addition, there was no difference between rest and exercise in the average slope of the linear regression between percentage FBF (where control FBF at rest was equal to 100%) and

were statistically significant at rest and during exercise (Fig. 1). In addition, there was no difference between rest and exercise in the average slope of the linear regression between percentage FBF (where control FBF at rest was equal to 100%) and  (P = 0.205) (Fig. 2). In contrast, even though the increases in the MCA Vmean from rest to exercise were not statistically significant (Table 1), the linear relationships between

(P = 0.205) (Fig. 2). In contrast, even though the increases in the MCA Vmean from rest to exercise were not statistically significant (Table 1), the linear relationships between  and MCA Vmean were statistically significant at rest (P < 0.001) and during exercise (P = 0.035). However, the MCA Vmean response to the changes in

and MCA Vmean were statistically significant at rest (P < 0.001) and during exercise (P = 0.035). However, the MCA Vmean response to the changes in  was greater at rest compared with that during exercise. Thus, there was a reduction in the average slope of the linear regression of the relationship between percentage MCA Vmean and

was greater at rest compared with that during exercise. Thus, there was a reduction in the average slope of the linear regression of the relationship between percentage MCA Vmean and  (P = 0.035) from rest to exercise. In addition, the percentage change from rest MCA Vmean to the absolute changes in

(P = 0.035) from rest to exercise. In addition, the percentage change from rest MCA Vmean to the absolute changes in  was lower than the percentage changes in FBF to the absolute changes in

was lower than the percentage changes in FBF to the absolute changes in  at rest (13.3 ± 2.4 versus 4.7 ± 1.1% min l−1) and during exercise (10.4 ± 1.8 versus 2.1 ± 0.7% min l−1).

at rest (13.3 ± 2.4 versus 4.7 ± 1.1% min l−1) and during exercise (10.4 ± 1.8 versus 2.1 ± 0.7% min l−1).

Figure 1. A summary of the linear relationships between  and FBF (A) or MCA Vmean (B) at rest (•) and during exercise (○).

and FBF (A) or MCA Vmean (B) at rest (•) and during exercise (○).

Symbols denote actual group data for all subjects (means ± s.e.m.). The lines represent the linear regressions calculated from the group average data. The significant relationship between  (in l min−1) and percentage FBF (where control FBF at rest was equal to 100%) was linear; Rest, FBF (%) = 11.9 ×

(in l min−1) and percentage FBF (where control FBF at rest was equal to 100%) was linear; Rest, FBF (%) = 11.9 × + 19.4, R = 0.93, P = 0.023; Exercise, FBF (%) = 10.0 ×

+ 19.4, R = 0.93, P = 0.023; Exercise, FBF (%) = 10.0 × – 37.3, R = 0.98, P = 0.003. The significant relationship between

– 37.3, R = 0.98, P = 0.003. The significant relationship between  (in l min−1) and MCA Vmean (in cm s−1) was linear; Rest, MCA Vmean = 3.4 ×

(in l min−1) and MCA Vmean (in cm s−1) was linear; Rest, MCA Vmean = 3.4 × + 44.0, R = 0.99, P < 0.001; Exercise, MCA Vmean = 1.2 ×

+ 44.0, R = 0.99, P < 0.001; Exercise, MCA Vmean = 1.2 × + 52.9, R = 0.90, P = 0.035.

+ 52.9, R = 0.90, P = 0.035.

Figure 2. Group averaged responses of FBF (A) and MCA Vmean (B) to the change in  at rest and during exercise.

at rest and during exercise.

Bars represent the average slope of the linear regression line between percentage FBF and  (A) and between percentage MCA Vmean and

(A) and between percentage MCA Vmean and  (B) for all subjects (means ± s.e.m.) at rest and during exercise.

(B) for all subjects (means ± s.e.m.) at rest and during exercise.

Transfer function analysis of the dynamic relationship between beat-to-beat changes in MCA Vmean and MAP was used to assess cerebral autoregulation across changes in  (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Power spectra of MCA Vmean and MAP were not altered at rest and during exercise by the LBNP or the infusion of albumin. The phase and gain between MCA Vmean and MAP in the LF range were not altered across changes in

(Table 2 and Fig. 3). Power spectra of MCA Vmean and MAP were not altered at rest and during exercise by the LBNP or the infusion of albumin. The phase and gain between MCA Vmean and MAP in the LF range were not altered across changes in  and central blood volume during rest or exercise indicating that the cerebral autoregulation was maintained. The LF coherence between MCA Vmean and MAP was above 0.5 both at rest and during exercise.

and central blood volume during rest or exercise indicating that the cerebral autoregulation was maintained. The LF coherence between MCA Vmean and MAP was above 0.5 both at rest and during exercise.

Table 2.

Power spectra of beat-to-beat variability of mean arterial pressure and middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity during lower body negative pressure (LBNP) and the infusion of albumin at rest and during exercise

| LBNP | Infusion of albumin | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB16 | LB8 | control | INF1 | INF2 | ||

| MAP (mmHg)2 | ||||||

| Rest | ||||||

| VLF | 5.28 ± 1.43 | 9.88 ± 5.03 | 3.69 ± 0.62 | 6.39 ± 2.30 | 5.57 ± 1.30 | |

| LF | 6.97 ± 1.64 | 7.33 ± 2.84 | 4.22 ± 1.08 | 3.47 ± 0.85 | 5.04 ± 1.29 | |

| HF | 0.46 ± 0.14 | 0.44 ± 0.22 | 0.41 ± 0.11 | 0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.43 ± 0.16 | |

| Exercise | ||||||

| VLF | 4.87 ± 1.36 | 3.64 ± 0.85 | 4.13 ± 0.81 | 5.01 ± 1.24 | 4.03 ± 0.64 | |

| LF | 6.73 ± 1.30 | 5.62 ± 1.29 | 5.16 ± 1.36 | 3.06 ± 0.82† | 2.53 ± 0.46† | |

| HF | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 0.21 ± 0.08 | 0.28 ± 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.19 ± 0.08 | |

| MCA Vmean (cm s−1)2 | ||||||

| Rest | ||||||

| VLF | 4.69 ± 1.05 | 5.93 ± 0.84 | 4.70 ± 1.03 | 5.37 ± 0.86 | 9.32 ± 3.52 | |

| LF | 3.18 ± 0.47 | 3.29 ± 1.14 | 2.67 ± 0.64 | 2.49 ± 0.73 | 4.30 ± 1.28 | |

| HF | 0.37 ± 0.09 | 0.30 ± 0.12 | 0.36 ± 0.11 | 0.53 ± 0.29 | 0.42 ± 0.16 | |

| Exercise | ||||||

| VLF | 3.96 ± 1.19 | 3.70 ± 1.05 | 2.89 ± 0.66 | 3.72 ± 1.12 | 3.36 ± 1.10# | |

| LF | 3.56 ± 1.04 | 3.36 ± 0.68 | 2.45 ± 0.62 | 2.66 ± 0.80 | 2.15 ± 0.44 | |

| HF | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.06 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.28 ± 0.07 | 0.22 ± 0.05 | |

Values are means ± s.e.m.; MAP, mean arterial pressure; MCA Vmean, middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity; VLF, very low frequency range (0.02–0.07 Hz); VL, low frequency range (0.07–0.20 Hz); HF, high frequency range (0.20–0.03 Hz); LB8, 8 Torr LBNP; LB16, 16 Torr LBNP; INF1, first albumin infusion; INF2, second albumin infusion.

Different from LB16, P < 0.05;

different from rest.

Figure 3. Grouped-averaged low-frequency (LF) transfer function phase (A), gain (B) and coherence (C) between MAP and MCA Vmean at rest (filled bars) and during exercise (open bars).

Values are means ± s.e.m.†Different from rest.

Discussion

The findings of the present investigation provide new information regarding the influence of cardiac output on middle cerebral artery mean blood velocity and its autoregulation at rest and during dynamic exercise, independent of Pa,CO2. Specifically, the relationship between the changes in MCA Vmean and the changes in  at rest and during dynamic exercise were linear and highly significant; however, during exercise the slope of the relationship was reduced by 55% from that at rest (Fig. 2). This exercise-induced decrease in the responsiveness of MCA Vmean to changes in

at rest and during dynamic exercise were linear and highly significant; however, during exercise the slope of the relationship was reduced by 55% from that at rest (Fig. 2). This exercise-induced decrease in the responsiveness of MCA Vmean to changes in  occurred without changes in Pa,CO2 or cerebral autoregulation. These data suggest that the sympathoexcitation associated with exercise may have directly affected MCA Vmean by changing CVRi, or indirectly by enabling a redistribution of

occurred without changes in Pa,CO2 or cerebral autoregulation. These data suggest that the sympathoexcitation associated with exercise may have directly affected MCA Vmean by changing CVRi, or indirectly by enabling a redistribution of  between the systemic circulation and the cerebral circulation.

between the systemic circulation and the cerebral circulation.

Patients with chronic heart failure (Hellstrom et al. 1997) and atrial fibrillation (Ide et al. 1999) have an attenuated ability to elevate cerebral perfusion during exercise because of their impaired ability to increase  . β1-Blockade-induced reductions in

. β1-Blockade-induced reductions in  in healthy subjects resulted in a reduction of the increase in MCA Vmean that occurred from rest to dynamic exercise despite the increase in MAP (Ide et al. 1998, 2000; Dalsgaard et al. 2004). These findings indicate that a reduced ability to increase

in healthy subjects resulted in a reduction of the increase in MCA Vmean that occurred from rest to dynamic exercise despite the increase in MAP (Ide et al. 1998, 2000; Dalsgaard et al. 2004). These findings indicate that a reduced ability to increase  during exercise limits MCA Vmean. Cerebral autoregulation is an important mechanism in maintaining a constant cerebral blood flow within an arterial pressure range of 60–150 mmHg (Paulson et al. 1990), when Pa,CO2 remains constant (Ide & Secher, 2000; LeMarbre et al. 2003; Ainslie et al. 2005). Because the data of the present investigation identify that moderate exercise, LBNP, infusions of human serum albumin and their combination did not alter cerebral autoregulation or Pa,CO2 (Table 1 and Fig. 3), the MCA Vmean observed during this investigation was directly related to the absolute value of

during exercise limits MCA Vmean. Cerebral autoregulation is an important mechanism in maintaining a constant cerebral blood flow within an arterial pressure range of 60–150 mmHg (Paulson et al. 1990), when Pa,CO2 remains constant (Ide & Secher, 2000; LeMarbre et al. 2003; Ainslie et al. 2005). Because the data of the present investigation identify that moderate exercise, LBNP, infusions of human serum albumin and their combination did not alter cerebral autoregulation or Pa,CO2 (Table 1 and Fig. 3), the MCA Vmean observed during this investigation was directly related to the absolute value of  . Collectively, these findings suggest that

. Collectively, these findings suggest that  influences the MCA Vmean regulated by cerebral autoregulation.

influences the MCA Vmean regulated by cerebral autoregulation.

MCA Vmean and central blood flow remained constant, or were slightly increased from rest to exercise despite large increases in  and MAP (Madsen et al. 1993). In the present study exercise did not increase MCA Vmean(+5.9 ± 4.0%), but interestingly it increased forearm blood flow (+30.4 ± 4.9%) despite the presence of a sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction. More importantly the calculated CVRi increased from rest to exercise (Table 1). These data suggest that cerebral vasoconstriction was a result of the exercise induced sympathoexcitation (Ide et al. 2000) and the change in the vascular resistance was greater in the brain than in the forearm at the same perfusion pressure. This greater increase in vascular resistance of the brain than in the peripheral vasculature may be a mechanism of protection for the brain against the large increases in

and MAP (Madsen et al. 1993). In the present study exercise did not increase MCA Vmean(+5.9 ± 4.0%), but interestingly it increased forearm blood flow (+30.4 ± 4.9%) despite the presence of a sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction. More importantly the calculated CVRi increased from rest to exercise (Table 1). These data suggest that cerebral vasoconstriction was a result of the exercise induced sympathoexcitation (Ide et al. 2000) and the change in the vascular resistance was greater in the brain than in the forearm at the same perfusion pressure. This greater increase in vascular resistance of the brain than in the peripheral vasculature may be a mechanism of protection for the brain against the large increases in  and MAP that occur during moderate and heavy exercise.

and MAP that occur during moderate and heavy exercise.

Sympathetic nerves richly innervate the brain's vasculature; however, it is thought that they have little influence on cerebral vasculature function (Ide et al. 2000). For example, in cats, electrical stimulation of the distal cut end of the petrosal nerve had no effect on total cerebral blood flow (Busija & Heistad, 1981). In rats, sensory nerve stimulation did not significantly affect cerebral blood flow, even after sympathetic denervation (Morita-Tsuzuki et al. 1993). However, Pearce & D'Alecy (1980) demonstrated that in dogs the increase in CVRi induced by haemorrhage is eliminated by α-adrenergic blockade. They further demonstrated that sympathetic vasoconstriction contributed approximately 5% to prehaemorrhage CVRi and suggested that the cerebrovascular response to haemorrhage was a balance between autoregulatory vasodilatation and sympathetic vasoconstriction. Moreover, denervation of arterial baroreceptors of rats blunted the cerebral vasodilatation associated with a breakdown of autoregulation (Talman et al. 1994). In humans, handgrip exercise-induced increases in sympathetic activity was associated with increases in CVRi during isocapnia (Ainslie et al. 2005) and dynamic cerebral autoregulation was found to be attenuated by ganglion blockade (Zhang et al. 2002). These findings suggest that autonomic neural control of the cerebral circulation plays a significant role in the beat-to-beat regulation of cerebral blood flow. However, it is well known that CO2 is the most powerful regulator of vascular tone in the brain and it has been reported that baroreflex-induced sympathetic activation had no influence on the cerebral vascular response to CO2 (LeMarbre et al. 2003). Collectively, these findings suggest that the importance of the sympathetically mediated vasoconstriction in the cerebral circulation may be to protect the blood–brain barrier when limits of autoregulation are exceeded.

The changes in MCA Vmean that occurred in response to the central blood volume-induced changes in  were decreased from rest to exercise (P = 0.035, Figs 1 and 2). One possible explanation is the presence of a decrease in the distribution of

were decreased from rest to exercise (P = 0.035, Figs 1 and 2). One possible explanation is the presence of a decrease in the distribution of  to the brain during exercise. For example, when exercise increases the cardiac output 4–5 times from rest, to enable blood flow to the active muscle to be increased, the distribution of

to the brain during exercise. For example, when exercise increases the cardiac output 4–5 times from rest, to enable blood flow to the active muscle to be increased, the distribution of  to the brain was decreased from rest (14%) to exercise (3%) (Rowell, 1993). Thus, the changes in MCA Vmean to changes in

to the brain was decreased from rest (14%) to exercise (3%) (Rowell, 1993). Thus, the changes in MCA Vmean to changes in  during exercise would be less because of the reduced proportion of total

during exercise would be less because of the reduced proportion of total  being directed to the brain. This reduction in proportion of

being directed to the brain. This reduction in proportion of  distributed to the brain would be dependent on the exercise workload. Hence, the exercise-induced decreases in changes of MCA Vmean associated with the changes in

distributed to the brain would be dependent on the exercise workload. Hence, the exercise-induced decreases in changes of MCA Vmean associated with the changes in  may be explained by the reduced proportion of

may be explained by the reduced proportion of  distributed to the brain (Fig. 2).

distributed to the brain (Fig. 2).

As the changes in  were associated with the experimentally induced changes in central blood volume, changes in sympathetic activity resulting from the loading and unloading of the cardiopulmonary baroreceptors appear to influence the cerebral vasculature in the presence of a constant MAP. However, if the cardiopulmonary baroreflex-induced sympathetic vasoconstriction of the periphery is a mechanism for maintaining arterial pressure and cerebral perfusion and the same vasoconstriction were to occur at the same magnitude in the brain, cerebral blood flow would be compromised (LeMarbre et al. 2003). A similar vasoconstriction of the brain's vasculature may not assist in defending blood pressure during decreases in central blood volume because the cerebral circulation is located above the level of the heart and the brain has a relatively small vascular bed. Moreover, sympathetic activation elicited by unloading the cardiopulmonary baroreceptors had no influence on the cerebralvascular response to CO2 (LeMarbre et al. 2003). Thus, the different responses between MCA Vmean and FBF may be evidence for the existence of a different cardiopulmonary baroreflex control of the brain vasculature compared to that of others (Johnson et al. 1974; Victor & Leimbach, 1987).

were associated with the experimentally induced changes in central blood volume, changes in sympathetic activity resulting from the loading and unloading of the cardiopulmonary baroreceptors appear to influence the cerebral vasculature in the presence of a constant MAP. However, if the cardiopulmonary baroreflex-induced sympathetic vasoconstriction of the periphery is a mechanism for maintaining arterial pressure and cerebral perfusion and the same vasoconstriction were to occur at the same magnitude in the brain, cerebral blood flow would be compromised (LeMarbre et al. 2003). A similar vasoconstriction of the brain's vasculature may not assist in defending blood pressure during decreases in central blood volume because the cerebral circulation is located above the level of the heart and the brain has a relatively small vascular bed. Moreover, sympathetic activation elicited by unloading the cardiopulmonary baroreceptors had no influence on the cerebralvascular response to CO2 (LeMarbre et al. 2003). Thus, the different responses between MCA Vmean and FBF may be evidence for the existence of a different cardiopulmonary baroreflex control of the brain vasculature compared to that of others (Johnson et al. 1974; Victor & Leimbach, 1987).

The contribution of changes in  to the carotid baroreflex control of blood pressure during exercise was found to be minimal (Collins et al. 2001; Ogoh et al. 2003) and supported previous work identifying differences in the contribution of carotid-cardiac and carotid-vasomotor arms of the carotid baroreflex to blood pressure regulation during changes in posture (Ogoh et al. 2002). In dogs the reflex response to carotid baroreceptor stimulation was peripheral vasoconstriction and did the alterations in

to the carotid baroreflex control of blood pressure during exercise was found to be minimal (Collins et al. 2001; Ogoh et al. 2003) and supported previous work identifying differences in the contribution of carotid-cardiac and carotid-vasomotor arms of the carotid baroreflex to blood pressure regulation during changes in posture (Ogoh et al. 2002). In dogs the reflex response to carotid baroreceptor stimulation was peripheral vasoconstriction and did the alterations in  were not identified as being part of the reflex response (Collins et al. 2001). In addition, in humans a carotid-vasomotor reflex-mediated change in total vascular conductance was the major response to carotid baroreceptor stimulation during exercise (Ogoh et al. 2003) and orthostasis (Ogoh et al. 2002). However, the findings of the present study identified that changes in

were not identified as being part of the reflex response (Collins et al. 2001). In addition, in humans a carotid-vasomotor reflex-mediated change in total vascular conductance was the major response to carotid baroreceptor stimulation during exercise (Ogoh et al. 2003) and orthostasis (Ogoh et al. 2002). However, the findings of the present study identified that changes in  affect the MCA Vmean at rest and during exercise. Thus, carotid-cardiac baroreflex function may prove to be more important to the regulation of MCA Vmean than its control of blood pressure. Interestingly, the changes in MCA Vmean associated with changes in

affect the MCA Vmean at rest and during exercise. Thus, carotid-cardiac baroreflex function may prove to be more important to the regulation of MCA Vmean than its control of blood pressure. Interestingly, the changes in MCA Vmean associated with changes in  were reduced from rest to exercise and may be related to the reduction in carotid-cardiac baroreflex sensitivity associated with relocation of the operating point of the cardiac arterial baroreflex that occurs during exercise (Ogoh et al. 2005c). These findings suggest that arterial baroreflex regulation of blood pressure via reflex regulation of the systemic vasculature becomes more involved in maintaining cerebral perfusion during exercise.

were reduced from rest to exercise and may be related to the reduction in carotid-cardiac baroreflex sensitivity associated with relocation of the operating point of the cardiac arterial baroreflex that occurs during exercise (Ogoh et al. 2005c). These findings suggest that arterial baroreflex regulation of blood pressure via reflex regulation of the systemic vasculature becomes more involved in maintaining cerebral perfusion during exercise.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the time and effort expended by all the volunteer subjects. We thank Jill Kurschner and Joseph Raven for the expert technical assistance. This study was supported in part by AHA-TX. Affiliate Grant no. 0465104Y and NIH grant no. HL045547.

References

- Ainslie PN, Ashmead JC, Ide K, Morgan BJ, Poulin MJ. Differential responses to CO2 and sympathetic stimulation in the cerebral and femoral circulations in humans. J Physiol. 2005;566:613–624. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brys M, Brown CM, Marthol H, Franta R, Hilz MJ. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation remains stable during physical challenge in healthy persons. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1048–H1054. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00062.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busija DW, Heistad DD. Effects of cholinergic nerves on cerebral blood flow in cats. Circ Res. 1981;48:62–69. doi: 10.1161/01.res.48.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins HL, Augustyniak RA, Ansorge EJ, O'Leary DS. Carotid baroreflex pressor responses at rest and during exercise: cardiac output vs regional vasoconstriction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H642–H648. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard MK, Ogoh S, Dawson EA, Yoshiga CC, Quistorff B, Secher NH. Cerebral carbohydrate cost of physical exertion in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R534–R540. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00256.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl RR, Linden D, Lucke D, Berlit P. Phase relationship between cerebral blood flow velocity and blood pressure. A clinical test of autoregulation. Stroke. 1995;26:1801–1804. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.10.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley LH, Mason JW, Hogan RP, Jones LG, Kotchen TA, Mougey EH, Wherry FE, Pennington LL, Ricketts PT. Multiple hormonal responses to graded exercise in relation to physical training. J Appl Physiol. 1972;33:602–606. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.33.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom G, Magnusson B, Wahlgren NG, Gordon A, Sylven C, Saltin B. Physical exercise may impair cerebral perfusion in patients with chronic heart failure. Cardiol Elder. 1997;4:191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ide K, Boushel R, Sorensen HM, Fernandes A, Cai Y, Pott F, Secher NH. Middle cerebral artery blood velocity during exercise with beta-1 adrenergic and unilateral stellate ganglion blockade in humans. Acta Physiol Scand. 2000;170:33–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.2000.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide K, Gullov AL, Pott F, Van Lieshout JJ, Koefoed BG, Petersen P, Secher NH. Middle cerebral artery blood velocity during exercise in patients with atrial fibrillation. Clin Physiol. 1999;19:284–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.1999.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide K, Pott F, Van Lieshout JJ, Secher NH. Middle cerebral artery blood velocity depends on cardiac output during exercise with a large muscle mass. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;162:13–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.0280f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide K, Secher NH. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;61:397–414. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JM, Rowell LB, Niederberger M, Eisman MM. Human splanchnic and forearm vasoconstrictor responses to reductions of right atrial and aortic pressures. Circ Res. 1974;34:515–524. doi: 10.1161/01.res.34.4.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen LG, Perko M, Perko G, Secher NH. Middle cerebral artery velocity during head-up tilt induced hypovolaemic shock in humans. Clin Physiol. 1993;13:323–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1993.tb00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMarbre G, Stauber S, Khayat RN, Puleo DS, Skatrud JB, Morgan BJ. Baroreflex-induced sympathetic activation does not alter cerebrovascular CO2 responsiveness in humans. J Physiol. 2003;551:609–616. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen PL, Sperling BK, Warming T, Schmidt JF, Secher NH, Wildschiodtz G, Holm S, Lassen NA. Middle cerebral artery blood velocity and cerebral blood flow and O2 uptake during dynamic exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:245–250. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita-Tsuzuki Y, Hardebo JE, Bouskela E. Interaction between cerebrovascular sympathetic, parasympathetic and sensory nerves in blood flow regulation. J Vasc Res. 1993;30:263–271. doi: 10.1159/000159005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoh S, Dalsgaard MK, Yoshiga CC, Dawson EA, Keller DM, Raven PB, Secher NH. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation during exhaustive exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005a;288:H1461–H1467. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00948.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoh S, Fadel PJ, Monteiro F, Wasmund WL, Raven PB. Haemodynamic changes during neck pressure and suction in seated and supine positions. J Physiol. 2002;540:707–716. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoh S, Fadel PJ, Nissen P, Jans O, Selmer C, Secher NH, Raven PB. Baroreflex-mediated changes in cardiac output and vascular conductance in response to alterations in carotid sinus pressure during exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2003;550:317–324. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoh S, Fadel PJ, Zhang R, Selmer C, Jans O, Secher NH, Raven PB. Middle cerebral artery flow velocity and pulse pressure during dynamic exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005b;288:H1526–H1531. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00979.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoh S, Fisher JP, Dawson EA, White MJ, Secher NH, Raven PB. Autonomic nervous system influence on arterial baroreflex control of heart rate during exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2005c;566:599–611. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1990;2:161–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce WJ, D'Alecy LG. Hemorrhage-induced cerebral vasoconstriction in dogs. Stroke. 1980;11:190–197. doi: 10.1161/01.str.11.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB. Human Cardiovascular Control. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. Control of regional blood flow during dynamic exercise. [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT, Dragon DN, Ohta H. Baroreflexes influence autoregulation of cerebral blood flow during hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:H1183–H1189. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.3.H1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triebwasser JH, Johnson RL, Burpo RP, Campbell JC, Reardon WC, Blomqvist CG. Noninvasive determination of cardiac output by a modified acetylene rebreathing procedure utilizing mass spectrometer measurements. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1977;48:203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieshout JJ, Pott F, Madsen PL, Van Goudoever J, Secher NH. Muscle tensing during standing: effects on cerebral tissue oxygenation and cerebral artery blood velocity. Stroke. 2001;32:1546–1551. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.7.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lieshout JJ, Wieling W, Karemaker JM, Secher NH. Syncope, cerebral perfusion, and oxygenation. J Appl Physiol. 2003;94:833–848. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00260.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor RG, Leimbach WN., Jr Effects of lower body negative pressure on sympathetic discharge to leg muscles in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:2558–2562. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.6.2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney RJ. The measurement of volume changes in human limbs. J Physiol. 1953;121:1–27. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1953.sp004926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Giller CA, Levine BD. Transfer function analysis of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Am J Physiol. 1998a;274:H233–H241. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.1.h233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Iwasaki K, Wilson TE, Crandall CG, Levine BD. Autonomic neural control of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in humans. Circulation. 2002;106:1814–1820. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000031798.07790.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zuckerman JH, Levine BD. Deterioration of cerebral autoregulation during orthostatic stress: insights from the frequency domain. J Appl Physiol. 1998b;85:1113–1122. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.3.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]