As CO2 concentrations continue to rise and discussions on global warming assume ever more warning tones, understanding of the CO2 cycle between the atmosphere and biosphere becomes ever more important. Most CO2 enters the biosphere through the actions of Rubisco, an enzyme found in all plants and many microorganisms. For many of these organisms, this entry into the biosphere via the C3 carbon reduction cycle is fraught with impediments associated with particular attributes of this enzyme. At one time, Rubisco, because of its poor performance, was not considered up to the task of being the primary agent for atmospheric CO2 fixation. Although its role in this capacity was for some years in serious doubt, we know now that this most abundant enzyme is in fact the primary agent. However, as its numerous idiosyncratic features have revealed themselves, it has become clearer just how tenuous this primary reaction really is.

“It is demonstrable,” said [Pangloss], “that things cannot be otherwise than as they are; for as all things have been created for some end, they must necessarily be created for the best end.

“… they, who assert that everything is right, do not express themselves correctly; they should say that everything is best.” (1)

In this issue of PNAS, Tcherkez et al. (2) deal with perhaps the biggest impediment, namely the competition between partial reactions of the enzyme that lead either to CO2 fixation or to alternative products from a wasteful oxygenation reaction. In their analysis, they provide a kinetic and thermodynamic rationale for the limitations of the reaction and indicate how most, if not all, Rubisco species studied to date conform to this rationale. These observations are of practical importance because a voluminous literature suggests that increases in the selectivity of Rubisco toward carboxylation could lead to improved rates and yields of photosynthetic carbon fixation, which in turn could enhance yields of many agronomically important crops.

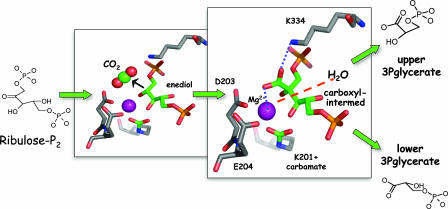

The enzyme catalyzed reaction (Fig. 1) begins with conversion of the substrate ribulose-P2 into a reactive enediol (3). The enediol is subject to numerous fates, only one of which is productive for CO2 fixation. It can be reprotonated on the wrong face to create a tightly bound inhibitor (xylulose-P2), it can undergo elimination of the C1-phosphate group, or it can react with gaseous electrophiles. The enzyme apparently holds the enediol so as to maximize its reactivity with CO2. Binding of the substrate induces the closure of loops over the active site, burying the newly formed enediol deep within the protein (4, 5). There is then only one route of access for CO2 to the enediol—via a channel just large enough for CO2 or any other opportunistic molecule small enough to fit. Oxygen is similar to CO2 in its linearity but with the added feature that it is less sterically encumbered. For an enzyme intent on converting as much of the bisphosphate molecule to products via carboxylation, this is a serious disadvantage.

Fig. 1.

The active site of Rubisco occupied by intermediates of the carboxylase reaction as depicted by the transition-state analog 2-carboxyarabinitol-P2 (Protein Data Bank ID code 1RBL). In the smaller boxed image, the site is shown occupied by the enediol as CO2 reacts. Carboxylation of the enediol results in formation of 2-carboxy-3-keto-arabinitol-P2 (larger boxed image), and contacts involving K334 and the Mg2+ ion (6, 7) determine the conformation of the carboxyl as being more or less “product-like.” The progress of the reaction to product involves hydration and cleavage of the carboxylated intermediate (dashed red line).

“Well, my dear Pangloss,” said Candide to him, “when You were hanged, dissected, whipped, and tugging at the oar, did you continue to think that everything in this world happens for the best?”

“I have always abided by my first opinion,” answered Pangloss; “for, after all, I am a philosopher, and it would not become me to retract my sentiments… .” (1)

What reluctant beginnings for a molecule that will become the backbone of all life processes. CO2 is devoid of chemical hand- or footholds that the enzyme can use to its advantage to assist in deciding the fate of the fickle enediol. It seems that all the enzyme can do is present the intermediate to the gaseous surroundings that exist at that instant in time and leave the rest to chemistry. If this were the case, assuming equal reactivity, the ratio of the concentrations of CO2 and O2 would fully determine the partitioning of ribulose-P2 between the two competing reactions. At prevailing solution concentrations, O2 would win by ≈25:1 (250:10 μM), i.e., only ≈4% of the bisphosphate would be carboxylated. In fact, a typical Rubisco from C3 plants directs 75% of the bisphosphate into the more favored pathway. So although not totally directed toward carboxylation, the enzyme does indeed exert some preference.

As Tcherkez et al. (2) point out, there is indeed a correlation between the ratio of the gas concentrations and the degree of partitioning between the two reactions. The observed partitioning favors the reaction with CO2, and Rubiscos from different sources show different discretion. This discretion lies in the ability of the enzyme to dictate how the reaction intermediate emerges after carboxylation of the enediol: the more favored the carboxylase reaction, the closer the newly fixed CO2 resembles the characteristics of a carboxylate moiety in anticipation of the 3P-glycerate product that will ultimately form and the less it resembles the original gas molecule. However, this ability of the enzyme comes at some cost to the overall rate of the reaction. The more the enzyme induces a more product-like conformation (and hence favors carboxylation), the deeper the energy well in which the intermediate finds itself and the slower the subsequent steps of hydration and cleavage. From a detailed analysis of the partitioning parameters and kcat of Rubiscos from various photosynthetic organisms, the authors postulate a unified understanding of the inverse correlation between these two critical parameters. Furthermore, they have compiled compelling evidence that the enzyme is optimally suited for the thermal and gaseous environment in which it finds itself.

A further correlation that emerges from the authors’ survey (2) is the effect that increased discrimination in favor of carboxylation has on the preference for 12C over 13C. The more the carboxylated intermediate adopts a product-like conformation, the larger the kinetic isotope effect on carboxylation of the enediol, and the 12C/13C ratio increases. This increased preference is reflected in all biological molecules and ultimately becomes archived in the geological record. Over such time periods, the concentration of CO2 and O2 in the atmosphere has fluctuated significantly and so presumably has the response of the enzyme to optimally favor carboxylation over oxygenation. It then follows that the degree of discrimination between the isotopes of carbon must also have fluctuated in concert with atmospheric conditions. Temperature will also have played a role in defining the isotopic ratio given the negative correlation of increasing temperature on the ability of Rubisco to favor carboxylation. Observations in the recent past show the disturbing rise in the rate of CO2 emission. In most cases, plants respond positively to increased CO2 simply because there is more available to compete for the enediol at the enzyme active site and consequently less is wasted by oxygenation. However, with that increase in CO2 comes an increase in global average temperatures, which will have a negative effect on the ability of plants to take advantage of the more favorable conditions. These complexities are likely exacerbated by the better solubility characteristics of O2 relative to CO2 at higher temperature. If organisms do indeed respond to changing atmospheric gas and temperature conditions by adjusting the specificity of Rubisco, resulting in altered isotopic discrimination, it will be important to account for this variation to further understand earth’s development.

Why should the intricate and intimate details of this enzyme reaction be worthy of further dissection? Most simply, a question of high interest is now better defined, namely: What are the prospects for engineering improved forms of the enzyme, and how far can the specificities of the two competing reactions be decoupled from kcat? Tcherkez et al. (2) caution that the amount of improvement that could be introduced by design is unlikely to exceed the superior variants that have evolved naturally. Implicit in this view is whether we have sampled the natural orders extensively enough to know the true bounds of these two parameters. Do they extend beyond the form II Rubiscos, like the dimeric enzyme from Rhodospirillum rubrum with its fast turnover but where oxygenation is favored ≈2:1 under solution concentrations of CO2 and O2? Or do they extend beyond the other extreme exemplified by the enzyme from red algae, like Griffithsia monilis with its reasonable turnover and favoring carboxylation 6:1 (6) under the same conditions? Regardless, this article rightly underscores the need for precision in determining the reaction parameters of Rubisco. The assay can be challenging, and intimate knowledge of the behavior of all substrates, as well as the enzyme, is necessary to ensure acceptable precision, particularly in dealing with Rubiscos of unusual pedigree. Any report of a Rubisco from another source that is significantly better than Griffithsia and demonstrating an acceptable turnover will be subject to intense scrutiny. Interestingly, if the attributes of the Griffithsia enzyme were adopted by a typical C3 Rubisco, photosynthetic performance of the plant could potentially double.

Having proposed a unifying concept to explain the performance of Rubisco, could the same concept of near perfection be extended to other enzymes? One might argue about the definition of perfection, but from a biological perspective, perhaps nature most often finds the “best” solution for any particular catalytic need. Sometimes perfection may not be immediately obvious. Indeed, the detailed analysis of Tcherkez et al.(2) is required to see any signs at all of perfection in the slow, nonspecific, discordant activities of Rubisco. Although sequence space is too vast to be fully sampled, there may be many ways to perfection. If this is indeed the case, then we might anticipate that many enzymes do represent the “best fit” for the natural constraints in which they find themselves.

Although imparting the most favorable discriminatory characteristics to produce an “ideal” Rubisco seems like a daunting task in itself, it may only be a mere prelude to the difficulties associated with convincing a crop plant to respond beneficially to any new and improved Rubisco. We started off this Commentary describing the process of CO2 fixation as being rife with impediments, and Tcherkez et al. (2) have provided useful insights into the nature of these impediments. If we were to somehow overcome these problems and produce an improved Rubisco with adequate specificity and rate, the practical problems of improving plant productivity would still remain to be solved. Gaining control over expression of the enzyme and its folding, activation, and inhibition, especially within the confines of the plastid (7, 8), are future battles yet to be engaged.

Perhaps we should end with some further observations from Voltaire.

Pangloss used now and then to say to Candide: “There is a concatenation of all events in the best of possible worlds; for, in short, had {many apparently unrelated and accidental events not happened} you would not have been here to eat preserved citrons and pistachio nuts.”

“Excellently observed,” answered Candide; “but let us cultivate our garden.” (1)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Andreassi for his assistance in producing Fig. 1.

Footnotes

See companion article on page 7246.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Voltaire F.-M. Candide; (1901) from The Works of Voltaire, a Contemporary Version with Notes. New York: E. R. DuMont; 1759. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tcherkez G. G. B., Farquhar G. D., Andrews T. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:7246–7251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600605103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pierce J., Lormer G. H., Reddy G. Biochemistry. 1986;25:1636–1644. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newman J., Gutteridge S. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:25876–25886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleleand W. W., Andrews T. J., Gutteridge S., Hartman F. C., Lorimer G. H. Chem. Rev. (Washington D. C.) 1998;98:549–561. doi: 10.1021/cr970010r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitney S. M., Baldet P., Hudson G. S., Andrews T. J. Plant J. 2001;26:535–547. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanevski I., Maliga P., Rhoades D. F., Gutteridge S. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:133–141. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitney S. M., von Caemmerer S., Hudson G. S., Andrews T. J. Plant Physiol. 1999;121:579–588. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.2.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]