Abstract

We developed a novel model using fluorescent intravital microscopy to study the effect of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) on the extrasplenic microcirculation. Continuous infusion of ANP into the splenic artery (10 ng min−1 for 60 min) of male Long–Evans rats (220–250 g, n = 24) induced constriction of the splenic arterioles after 15 min (−7.2 ± 6.6% from baseline diameter of 96 ± 18.3 μm, mean ± s.e.m.) and venules (−14.4 ± 4.0% from 249 ± 25.8 μm; P < 0.05). At the same time flow did not change in the arterioles (from 1.58 ± 0.34 to 1.27 ± 0.27 ml min−1), although it decreased in venules (from 1.67 ± 0.23 to 1.15 ± 0.20 ml min−1) and increased in the lymphatics (from 0.007 ± 0.001 to 0.034 ± 0.008 ml min−1; P < 0.05). There was no significant change in mean arterial pressure (from 118 ± 5 to 112 ± 5 mmHg). After continuous ANP infusion for 60 min, the arterioles were dilated (108 ± 16 μm, P < 0.05) but the venules remained constricted (223 ± 24 μm). Blood flow decreased in both arterioles (0.76 ± 0.12 ml min−1) and venules (1.03 ± 0.18 ml min−1; P < 0.05), but was now unchanged from baseline in the lymphatics (0.01 ± 0.001 ml min−1). This was accompanied by a significant decrease in MAP (104 ± 5 mmHg; P < 0.05). At 60 min, there was macromolecular leak from the lymphatics, as indicated by increased interstitial fluorescein isothiocyanate–bovine serum albumin fluorescence (grey level: 0 = black; 255 = white; from 55.8 ± 7.6 to 71.8 ± 5.9, P < 0.05). This study confirms our previous proposition that, in the extrasplenic microcirculation, ANP causes greater increases in post- than precapillary resistance, thus increasing intrasplenic capillary hydrostatic pressure (Pc) and fluid efflux into the lymphatic system. Longer-term infusion of ANP also increases Pc, but this is accompanied by increased ‘permeability’ of the extrasplenic lymphatics, such that fluid is lost to perivascular third spaces.

Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) is synthesized in the atrium of the heart and is released into the circulation in response to stretch of the atrial wall. ANP causes diuresis and generalized vasodilatation via NPA receptors, which together reduce blood volume and blood pressure to restore homeostasis (Rubattu Volpe, 2001). However, mesenteric, coronary, renal and splenic vessels, from several species, have been found to constrict in response to ANP, with greater constriction observed on the postcapillary side of the circulation (Marin Grez et al. 1986; Ertl Bauer, 1990; Houben et al. 1998; Woods Jones, 1999; Andrew Kaufman, 2003). Interestingly, both the constriction and dilatation are mediated through NPA receptors and the guanylyl cyclase A (GCA) pathway (Endlich Steinhausen, 1997; Andrew Kaufman, 2003).

Our laboratory is interested in the effects of ANP within the splenic vasculature, and its role in blood volume regulation (Deng Kaufman, 1996; Sultanian et al. 2001). We have shown in rats that ANP (20 ng min−1 per 500 g body weight, i.a) causes a decrease in splenic vein blood flow, with no effect on arterial inflow (Sultanian et al. 2001). We concluded that this resulted in increased fluid extravasation caused by differential vasoconstriction of the postcapillary vessels. This was consistent with our observation that isolated extrasplenic veins are more sensitive to the vasoconstrictor effects of ANP than are the arteries (Andrew Kaufman, 2003). These changes allow ANP to increase intrasplenic capillary hydrostatic pressure (Pc), resulting in third space fluid losses (Sultanian et al. 2001). In the spleen, changes in capillary permeability do not contribute to increases in fluid extravasation, since the intrasplenic vasculature is freely permeable to protein (Kaufman Deng, 1993).

The rat spleen has no blood or lymph storage capacity (Reilly, 1985), nor does splenic weight change in response to ANP administration (Deng Kaufman, 1996). The extravasated fluid thus drains from the spleen through lymph ducts running adjacent to the splenic hilar arterioles and venules. Indeed, Evans Blue dye, injected into the splenic artery, rapidly appears in these extrasplenic lymphatics (Kaufman Deng, 1993). ANP also increases total systemic lymphatic capacity and impedes the return of fluid to the blood by inhibiting lymphatic pumping (Ohhashi et al. 1990; Atchison Johnston, 1996). We have therefore proposed that, in response to hypervolaemia and increased ANP secretion, there is an increase in intrasplenic extravasation and lymph drainage from the spleen. This fluid is then accommodated within the enlarged systemic lymphatic system, including the perisplenic mesenteric arcade, thus reducing intravascular fluid volume (Kaufman Deng, 1993). Nevertheless, to date, we have had no in vivo technique with which to directly observe or quantify changes in extrasplenic lymphatic flow in response to ANP.

Our hypothesis was that, within the splenic circulation, ANP causes greater post- than precapillary constriction, leading to increased intrasplenic Pc, increased fluid extravasation and increased splenic lymph flow. To test this hypothesis we developed a novel surgical technique for observing the extrasplenic arterioles, venules and lymphatic vessels using intravital microscopy (IVM). We found that fluorescently labelled albumin (fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated bovine serum albumin; FITC–BSA), administered into the splenic artery, appeared in both the extrasplenic microcirculation and the lymphatics. This allowed us to measure the effects of ANP on changes in diameter and macromolecular leak, a marker of endothelial cell integrity (Brookes et al. 2002). We also adapted a new IVM technique (Norman, 2001) to the extrasplenic microvasculature, whereby we administered fluorescently labelled microspheres to measure changes in centreline flow velocity. Finally, we were able to confirm our account of the role of the spleen in blood volume regulation by directly observing lymphatic permeability and flow.

Methods

Experiments were examined by a local Animal Welfare Committee in agreement with the Canada Council on Animal Care. These experiments also comply with the American Physiological Society's guiding principles for research involving animals and human beings.

Animals and housing

Male Long–Evans rats (n = 24) weighing 200 g were obtained from Charles River, St Foy, Quebec, Canada. They were held in the animal facility for 3–4 weeks prior to experimentation on a restricted diet of 45 kCal day−1 so that body weight did not exceed 260 g. Rats fed ad libitum tend to develop obesity (Keenan et al. 1998). A restricted diet prevents excessive fat and connective tissue deposition, thus allowing the extrasplenic microvasculature to be visualized. Animals were exposed to a 12 h–12 h light–dark cycle in a humidity- and temperature-controlled environment whilst allowed access to water ad libitum.

Drugs and solutions

Rat ANP (3062.5 MW, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Mountain View, CA, USA) was prepared in distilled water in stock solutions of 10−5 mol l−1 and stored in aliquots at −43°C until the day of use, when it was prepared in vehicle (saline) at a concentration of 10−6 mol l−1.

We conjugated fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC) on celite (10%, A1628, Sigma, Canada) to bovine serum albumin (BSA; 98%, A7030, Sigma, Canada). This was achieved by combining 340 mg of FITC with 2 g BSA in 20 ml of bicarbonate (0.6 g Na2CO3 (anhydrous), 3.7 g NaHCO3 and 100 ml distilled water adjusted to pH 9.0) in a stoppered test tube overnight at 4°C. The conjugation mixture was centrifuged at 3–5000 g for 10 min and the supernatant pipetted into cellulose dialysis tubing (molecular weight 12 000 Da). The sealed dialysis bag was placed in Nairn's solution (17(34) g NaCl, 0.692(1.384) g NaH2PO4, 2.14(4.28) g Na2HPO4 (anhydrous) and 2(4) l of distilled water, adjusted to pH 7.4) and stirred at 4°C, first for 12 h in the 2 l solution and then for 12 h in 4 l of fresh solution to remove unbound FITC. The tubing was then removed and the FITC–BSA solution stored in 0.5 ml aliquots at −20°C until required.

100 ml of protein A-labelled fluorescent microspheres (F13081, Molecular Probes Europe BV, Netherlands) were added to 4.9 ml of BlockAid™ (B107101, Molecular Probes) and incubated without light at room temperature for 30 min. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 5 ml) was then added and the mixture was placed in the centrifuge for 15 min at 1000g. The supernatant was removed, 5 ml of PBS added and centrifuged again, after which the pellet was resuspended in 300 μl of PBS. No more than 1 week later, on the day of use, 100 μl of vortexed bead solution was added to 1.9 ml of PBS.

Surgical procedures

Rats (220–260 g) were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (MTC Pharmaceuticals, Canada; 50 mg kg−1i.p.) and anaesthesia was maintained with Inactin (Byck, ethyl-(1-methyl-propyl)-malonyl-thio-urea, 60 mg kg−1s.c.) given 1 h after induction of anaesthesia. At the end of the study animals were administered a lethal dose of Euthanol (sodium barbitol; Bimeda-MTC, Canada, 1 ml kg−1) into the jugular vein.

Body temperature was maintained at 37°C throughout the experiment (Heating pads, Cole Palmer, Vernon Holts, IL, USA). The left carotid artery was cannulated with polyethylene tubing (0.58 mm i.d., 0.965 mm o.d.) for computerized monitoring and continuous recording of mean arterial blood pressure by WINDAQ (DI-400, DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH, USA). The right jugular vein was cannulated (polyethylene tubing, 0.58 mm i.d., 0.965 mm o.d.) for injections of either saline or fluorescent microspheres.

A laparotomy was performed and the spleen cleared from its attachments to the stomach. To ensure that the extrasplenic microvasculature supplied and drained only the spleen, all vessels connecting to the pancreas, stomach and surrounding connective tissue were ligated and cut (Kaufman Levasseur, 2003). These ligations have no effect on blood flow in the extrasplenic hilar vessels (Chen Kaufman, 1996). The splenic ligament was also cut, allowing manoeuvrability of the spleen and adjoining mesenteric tissue. The gastric artery was then cannulated with Silastic tubing (0.31 mm i.d., 0.64 mm o.d.), which was tunnelled to the junction with the splenic artery, for a single bolus injection of FITC–BSA and continuous infusion of either isotonic saline or ANP. The cannula was secured with tissue adhesive (3M Vetbond, Animal Care products, St Paul, MN, USA), the stomach returned to the abdomen, and the abdominal incision repaired leaving the spleen and extrasplenic mesentery exteriorized. The animal was placed on its left side, and microclamps were used to hold the spleen in position over a microscope slide mounted on Perspex pillars on a Perspex board. The spleen and mesentery were then immersed in saline (37°C) and covered in Saran wrap (Dow Chemical CO, USA, which is impermeable to oxygen (Sullivan Johnson, 1981). Such techniques, previously used to observe the mesenteric microcirculation, allow preparations to remain viable for up to 4 h (Brookes et al. 2002).

In vivo fluorescent microscopy

The animal, warming pad and Perspex board were transferred to the stage of a Leica fluorescent microscope (DMLM). The microscope was equipped with a tungsten lamp for transmitted light and a mercury arc lamp for epi-illumination fluorescent light microscopy. A filter cube interspersed into the path of the mercury arc lamp controlled the wavelength of light (blue: 460–490 nm) to which each area of interest (approx. 2 mm2) was exposed. Images of the preparation were displayed on a high-resolution monitor (Hitachi VM-920, USA) using a black and white CCD camera (Hitachi KP-M2 S1, USA). Images were recorded by VCR (Panasonic PV-V4023-K, USA) for later off-line computerized image analysis (Capiscope, KK Technology, Colyton, Devon, UK) using a frame grabber card (Matrox Meteor II, USA).

Three areas of the extrasplenic microcirculation were recorded every 15 min throughout the experimental protocol (t= 0−90 min), plus a 5 min period after commencing infusion of ANP (t= 35 min). Large paired arterioles (50–100 μm) and venules (200–300 μm) were selected from one of the four major arcades connecting the spleen to the splenic artery and vein. The small vessels (arterioles < 40 μm and venules < 50 μm) were found in the mesenteric windows between the arcades, and the lymphatic vessels (40–80 μm) were found either accompanying the larger vessels or traversing the mesenteric tissue.

Experimental protocol

Animals were divided into two experimental groups, one to measure diameter and macromolecular leak in the microcirculation and lymphatics (study A) and the other to measure diameter and velocity (blood flow) in the microcirculation (study B). Following surgery there was a 30 min stabilization period in both groups, followed by a 30 min equilibration period, during which time isotonic saline was infused continuously into the splenic artery via the gastric cannula (1.5 ml h−1). After baseline measurements were taken, the infusion of isotonic saline was either continued (controls) or replaced with 4 ng min−1 (100 g)−1 (1.3 pmol min−1 (100 g)−1) ANP (1.5 ml h−1) for 60 min (Deng Kaufman, 1996; Sultanian et al. 2001).

The only differences between studies A and B were as follows. In study A, FITC–BSA (0.2 ml (100 g)−1, i.e. 0.2 g (100 g)−1) was infused into the gastric artery at t= 0 min to animals receiving either ANP (n = 6) or saline (controls, n = 6). Thirty minutes was required for FITC–BSA to appear in the lymphatics (Fig. 1). In study B, fluorescent microspheres (0.2 ml (100 g)−1) were infused into the jugular vein at t= 30, 35, 45, 60 and 90 min in animals receiving either ANP (n = 6) or saline (controls, n = 6).

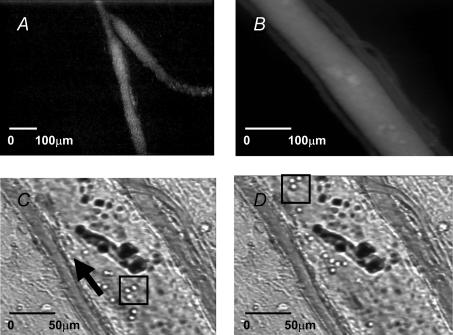

Figure 1.

A, extrasplenic lymphatics can be observed following intravascular administration of FITC–BSA and epi-illumination with blue light (Hitachi KP-M2 S1 camera). B, arteriole and venule (∼30 μm) accompanying lymphatic vessel (in centre; Hitachi KP-161 camera). C, arteriole, venule and lymphatic vessel illuminated with transmitted light. D, same specimen as C, but taken approximately 3 s later. Arrow shows direction of flow. In C and D, lymphocytes are within the box and are clearly seen moving at a continuous steady rate within the lymphatic vessels.

Data acquisition and analysis

External wall diameter was measured from the outside edge of the vessel using FITC–BSA and epi-illumination. The image analysis software (Capiscope) was calibrated with a micrometer specifically designed for the aforementioned camera and monitor, and three lines were drawn across the vessel to produce a median value in micrometres. For consistency, when spontaneous contractions were evident (∼30% of small arterioles only, 100% of lymphatics), measurements were made at the point of maximal diameter.

Macromolecular leak (study A) was measured using FITC–BSA and epi-illumination. FITC–BSA is normally retained within the vasculature for long periods of time and upon activation with blue light may be used to view the microcirculation (Brookes et al. 2002). When vessel integrity is compromised the endothelium becomes ‘permeable’ to macromolecules, and FITC is observed in a flare in the interstitium surrounding postcapillary venules (Brookes et al. 2002). In each animal, several lymphatics could be found distant from the hilar arterioles and venules. Thus, although FITC–BSA had not previously been used to view the extrasplenic microvasculature, macromolecular leak could be measured specifically for arterioles, for venules and for lymphatics. Capiscope assigned an integer value to the brightness of the interstitial fluorescence based on an arbitrary grey scale ranging from 0 (black) to 255 (white). The fluorescent light intensity thus measured is proportional to the amount of leak (Miller et al. 1982; Huxley et al. 1987a). Three small boxes (2 mm2) were placed at random sites adjacent to small venules and lymphatic vessels to produce a median of three values.

Velocity (study B) was determined in the 2 min immediately following administration of protein A-labelled 1 μm fluorescently labelled microspheres (yellow-green), which are observed in the microcirculation during concurrent illumination with both transmitted and blue fluorescent light (Norman, 2001). Microspheres of this size do not usually leak from the microvasculature (Norman, 2001). At 25 frames s−1 the distance microspheres moved over time, within a relatively straight vessel, could thus be computed using Capiscope. Velocity (μm s−1) was measured over 3–4 frames for arterioles and in < 10 frames for venules. Ten centreline velocity measurements were made and the three fastest used to calculate mean values (Norman, 2001). Mean velocity (Vf) was obtained from centreline velocity following multiplication by an empirical factor of 0.625, as described earlier (Lipowsky Zweifach, 1978). Actual blood flow (ml min−1) was then calculated using the circular cross-sectional area multiplied by the mean blood flow velocity: (π× (diameter/2)2×Vf; Ley et al. 1995). For determining flow, diameter was measured in the same vessel at the time of velocity measurement using transmitted light, which allowed assessment of internal diameter. As the large splenic hilar arterioles and venules were paired, we could also present flow as arteriovenous (A–V) difference, to give an indication of whether more blood was entering than leaving the spleen (Kaufman Levasseur, 2003).

The fluorescent microspheres did not appear in the lymphatics, and so this method could not be used to calculate lymphatic velocity. However, FITC–BSA was distributed non-uniformly within lymphatic vessels such that, at 25 frames s−1, velocity could be measured by pattern recognition. Our lymphatic vessels appeared to contain lymphocytes (Fig. 1), which created non-uniformity and allowed us to assess centreline flow velocity.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± s.e.m. Within-group analysis was performed using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA on ranks, followed by post hoc analysis with a Wilcoxon test for non-parametric data to identify points of significance compared to baseline. Between-group analysis was performed with a two-way ANOVA for repeated measures, followed by post hoc analysis at each time point using a Mann–Whitney U test. Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Initial effects of ANP infusion (t= 0–15 min)

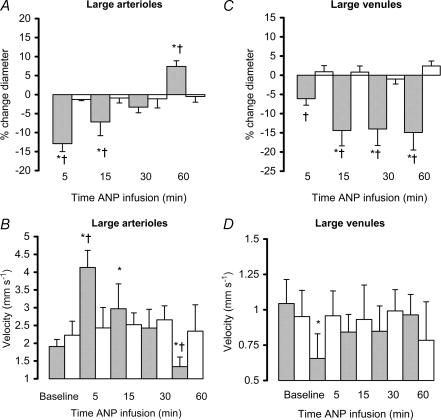

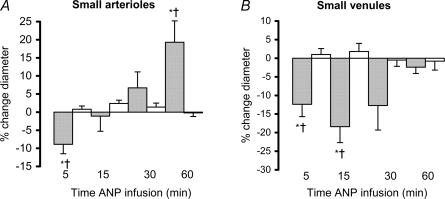

There was no significant difference in MAP between the ANP- and saline-infused animals, although blood pressure did tend to decrease in the ANP group (NS, Table 1). There was however, significant constriction of the extrasplenic microvasculature that was greater in the venules than in the arterioles (P < 0.05; Figs 2 and 3). ANP also increased centreline velocity in the large arterioles, but caused a decrease in the large venules (P < 0.05; Fig. 2, t= 5 min). Overall, there was a significant decrease in mean blood flow in the venules, in the absence of any significant change in the arterioles (Table 2), i.e. the A–V flow differential increased (P < 0.05; Table 2, t= 5 min).

Table 1.

The effect of ANP (10 ng min−1) infusion on mean arterial blood pressure

| Baseline | 5 min | 15 min | 30 min | 60 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | 118 ± 6 | 119 ± 6 | 117 ± 7 | 115 ± 7 | 114 ± 6 |

| ANP | 118 ± 4 | 114 ± 4 | 111 ± 5 | 109 ± 4* | 104 ± 5*† |

Values of MAP (means ± s.e.m.) are given in mmHg (n = 25).

P < 0.05, significantly different from baseline

P < 0.05 versus control.

Figure 2.

The effect of ANP infusion (10 ng min−1; shaded bars) or 1.5 ml h−1 saline (open bars) on the percentage change (mean ± s.e.m.) from baseline in the diameters of large extrasplenic arterioles (A, baseline diameter for ANP group 96.3 ± 18.0 μm, and for saline group 101.1 ± 9.6 μm) and venules (C, baseline for ANP group 249.0 ± 25.8 μm, and for saline group 269.0 ± 49.7 μm) and centreline erythrocyte velocity within extrasplenic large arterioles (B) and venules (D). *P < 0.05 ANP versus baseline, †P < 0.05 versus control.

Figure 3.

The effect of ANP infusion (10 ng min−1; shaded bars) or 1.5 ml h−1 saline (open bars) on the percentage change (mean ± s.e.m.) from baseline in the diameters of small extrasplenic arterioles (A, baseline diameter for ANP group 22.5 ± 3.6 μm, and for saline group 24.7 ± 0.9 μm) and venules (B, baseline for ANP group 32.1 ± 6.9 μm, and for saline group 33.7 ± 6.3 μm) *P < 0.05 ANP versus baseline, †P < 0.05 versus control.

Table 2.

The effect of ANP (10 ng min−1) infusion on large arteriole and large venule blood flow volume measured using fluorescent microspheres, and the difference between the two measurements (A–V difference)

| Baseline | 5 min | 15 min | 30 min | 60 min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arteriole | 1.579 ± 0.336 | 1.866 ± 0.339 | 1.274 ± 0.273 | 1.073 ± 0.231 | 0.759 ± 0.123*† |

| Venule | 1.675 ± 0.231 | 1.084 ± 0.367*† | 1.146 ± 0.201*† | 1.090 ± 0.294*† | 1.028 ± 0.179*† |

| Lymphatic | 0.007 ± 0.001 | 0.047 ± 0.008*† | 0.034 ± 0.008*† | 0.033 ± 0.005*† | 0.010 ± 0.001 |

| A–V difference | −0.096 ± 0.035 | +0.782 ± 0.027*† | +0.128 ± 0.026 | +0.018 ± 0.004 | −0.27 ± 0.022*† |

Values of blood flow (means ± s.e.m.) are in ml min−1. Lymphatic flow is also shown, measured using pattern recognition.

P < 0.05, significantly different from baseline

P < 0.05 versus control.

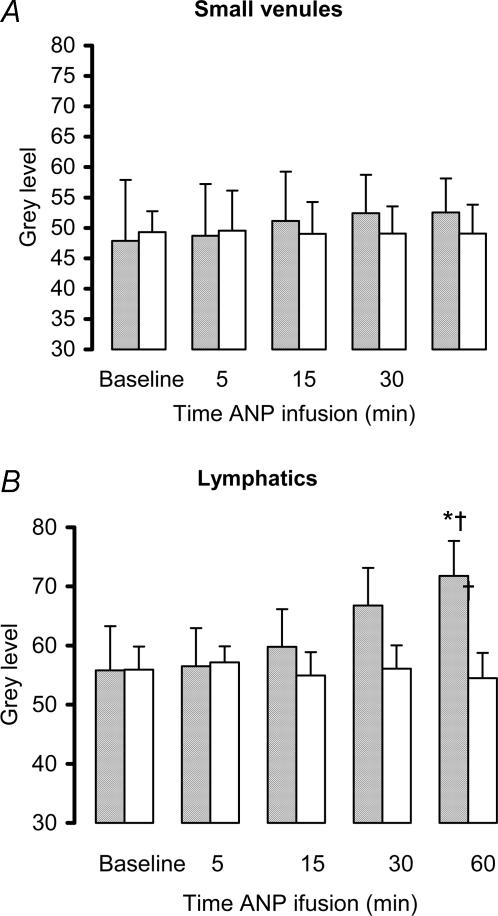

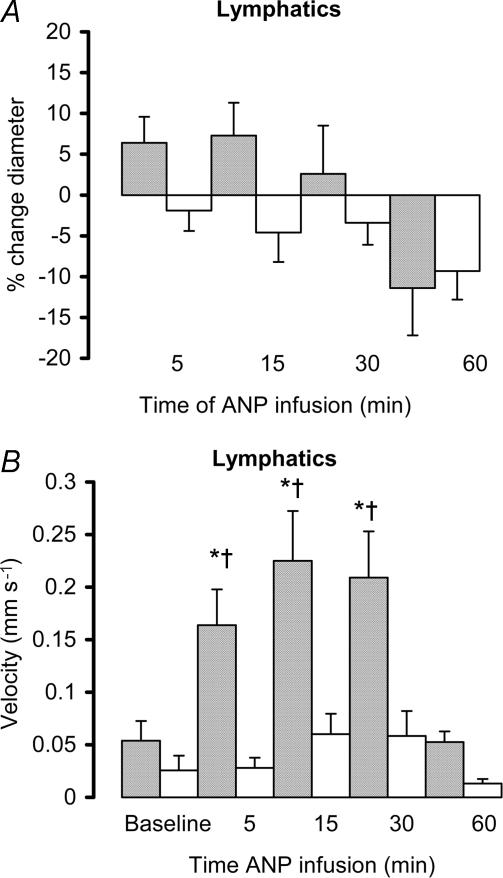

ANP also caused a significant increase in lymphatic velocity and flow (P < 0.05, Fig. 5 and Table 2), measured in the direction away from the spleen (outflow). There was no change in lymphatic vessel diameter (Fig. 4), nor was there any increase in macromolecular leak from either small venules or lymphatic vessels, indicating that endothelial cell integrity had been maintained (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

The effect of ANP infusion (10 ng min−1; shaded bars) or 1.5 ml h−1 saline (open bars) on interstitial fluorescence (0 = black, 255 = white) within the interstitium adjacent to extrasplenic postcapillary venules and lymphatics. Increased grey level indicates macromolecular leak and a compromise of the lymphatic endothelium. *P < 0.05 ANP versus baseline, †P < 0.05 ANP versus control.

Figure 4.

The effect of ANP infusion (10 ng min−1; shaded bars) or 1.5 ml h−1 saline (open bars) on the percentage change (mean ± s.e.m.) from baseline in diameter of extrasplenic lymphatics (A, baseline diameter for ANP group 89.4 ± 10.2 μm, and for saline group 89.7 ± 11.1 μm) and fluid velocity within the extrasplenic lymphatics. *P < 0.05 ANP versus baseline, †P < 0.05 ANP versus control.

Longer term effects of ANP infusion (t= 30–60 min)

ANP caused delayed dilatation of the arterioles (large and small) and continued constriction of the large venules (P < 0.05, Figs 2 and 3, t= 30–60 min). At 60 min, centreline velocity returned to baseline in the venules and was significantly reduced in the arterioles (P < 0.05, Fig. 2). Mean blood flow decreased in both arterioles and venules (P < 0.05, Table 2). Thirty minutes after the start of infusion, the A–V difference had returned to baseline, although at 60 min it had fallen below baseline (P < 0.05, Table 2).

With continued infusion of ANP, velocity and flow within the lymph vessels returned to baseline (Fig. 4 and Table 2). There was also a gradual increase in macromolecular leak, which appeared as a generalized flare in the interstitium surrounding the lymphatics, which reached significance by 60 min (P < 0.05, Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study describes a novel in vivo model of the spleen that allows direct observation of the extrasplenic microcirculation and lymphatics in rats by intravital microscopy. Using fluorescently labelled albumin and microspheres, changes in diameter, blood flow and endothelial cell integrity could be quantified during a continuous intravascular infusion of ANP. Close arterial infusion of ANP, at a dose designed to yield high physiological plasma levels (Deng Kaufman, 1996), caused immediate constriction of the splenic hilar vessels, which was greater in venules than in arterioles. This is consistent with previous studies in our laboratory showing differential vasoconstriction of the splenic arterial and venous vascular beds (in vivo), and of isolated small (∼200 μm) extrasplenic arterioles and venules (Deng Kaufman, 1996; Sultanian et al. 2001; Andrew Kaufman, 2003). In the present study, we have now demonstrated in vivo that ANP also induces constriction in much smaller arterioles and venules (< 40 μm). In addition, we used fluorescent microspheres to derive mean splenic blood flow from centreline velocity (Lipowsky et al. 1978; Ley et al. 1995; Norman, 2001), which yielded values that were in agreement with those we have previously observed using transit-time flow probes, i.e. little change in arterial blood flow, but a significant decrease in venous flow (Chen Kaufman, 1996). The larger extrasplenic arterioles and venules are paired, thus enabling us to calculate the A–V flow difference. As had been revealed with the transit-time flow probes, ANP caused the A–V flow differential of these paired vessels to become positive, again signifying intrasplenic fluid extravasation.

Due to the presence of cellular components within the lymphatic fluid (lymphocytes) we were able to use pattern recognition to assess lymphatic outflow from the spleen. These measurements provide the first direct evidence that ANP increases splenic lymphatic outflow. We know that ANP inhibits spontaneous contractions and relaxation of bovine lymphatic smooth muscle, thus increasing total lymphatic system capacitance and reducing lymph return to the intravascular space (Ohhashi et al. 1990; Atchison Johnston, 1996). There is also evidence that, in response to volume loading (and increased plasma ANP), the increase in transcapillary fluid flux is greater than the rate of lymph return to the blood, and that the volume surfeit is accommodated within an enlarged lymphatic system (Valenzuela-Rendon Manning, 1990). The sites at which physiological levels of ANP might increase microvascular permeability and fluid efflux have not previously been identified (Smits et al. 1987; Eliades et al. 1989). We propose that in response to hypervolaemia, the increase in transcapillary fluid flux is mediated primarily through an ANP-induced increase in intrasplenic capillary pressure and fluid extravasation. The net effect is to reduce intravascular volume, i.e. this is a classical negative feedback system.

With the exception of continued constriction in the small venules, the other measured parameters (diameter, flow and A–V difference) returned to or overshot baseline values during the last 30 min of ANP infusion. At this time, net effects on the splenic vasculature are presumably attributable not only to the direct effects of ANP, but also to neurohormonal reflexes initiated by the rise in systemic ANP levels, the fall in mean arterial pressure and the fall in plasma volume (Kaufman, 1992).

We have previously reported that there is no change in the plasma protein concentration of blood as it passes through the spleen, despite marked intrasplenic fluid extravasation (Kaufman Deng, 1993). Moreover, the lymph draining from the spleen is isoncotic to the plasma. We have concluded that, unlike most vascular beds, the intrasplenic microvasculature must be freely permeable to proteins and that, contrary to previous suggestions that ANP increases permeability of the microvasculature independently of hydrostatic forces (McKay Huxley, 1995), fluid extravasation within the splenic microvasculature must be wholly controlled by changes in capillary pressure. This may reflect a regional difference in the vascular bed of the spleen. Indeed, it has been shown that, unlike most vascular beds, splenic capillaries do have a discontinuous endothelium, thus rendering them more permeable to large molecules such as plasma proteins (Takubo et al. 1999). Our present observation that there was no change in macromolecular leak from the venules suggests that the site of such fluid extravasation must be deep within the spleen, rather than in the extrasplenic (hilar) vasculature. The role of the extrasplenic (hilar) vessels thus appears to be confined to controlling pre- versus postcapillary resistance and microvascular pressure.

Infusion of the large molecular weight protein FITC–BSA (∼66 kDa) is commonly used to measure endothelial cell junctional integrity within the microcirculation (Miller et al. 1982; Brookes et al. 2002). In the present study, FITC–BSA appeared in the extrasplenic lymphatics 20–30 min after intravascular administration into the splenic artery (Fig. 5). We were thus able to show that longer term infusion of ANP did cause macromolecular leak from lymphatic vessels. This is consistent with our previous observations that, in response to ANP, clear fluid appears to accumulate in a gel-like matrix around the splenic vascular arcade (Deng Kaufman, 1993). Our data are also consistent with previous suggestions that splanchnic interstitial matrices of hyaluronan/proteoglycans serve to accommodate, and ultimately remobilize, third space fluid losses, such as those associated with ANP administration, volume loading or endotoxaemia (Ostgaard Reed, 1993; Fraser et al. 1997; Berg, 1997; Holliday, 1999). Indeed, the apparent rise in the A–V difference (Table 2, 60 min), suggesting addition of fluid to the blood passing through the spleen, may be indicative of an as yet unreported reflex to remobilize this fluid back to the intravascular space.

Initial lymphatics have a single layer of endothelial cells and are non-contractile, feeding into the larger contractile collecting lymphatic vessels. Most lymphatics within the intestine are of the initial type, but the nature of those accompanying the splenic hilar vessels is unknown. If the lymphatic vessels studied were of the initial type their permeability would depend on the stress exerted on the vessel wall. A decrease in flow and pressure (such as occurred after 60 min of ANP) would allow the primary valves to open, followed by leakage of FITC–BSA into the interstitium. Like the rest of the microvasculature, lymphatic vessels are lined with endothelial cells (Schmid-Schonbein, 1990a). This raises the question of whether vessel integrity might be compromised by ANP, to allow to passage of macromolecules such as albumin, such as has been shown to occur in postcapillary venules (Huxley et al. 1987a, b; Trzewik et al. 2001). ANP inhibits phosphorylation of tight junctional proteins, which maintain the endothelial cell barrier structure in venules (Pedram et al. 2003) and lymphatic vessels also possess similar junctional proteins (Weber et al. 2002). Since conducting lymphatics are considered to be continuous, with very little permeability to proteins and fluid, a compromise of the endothelial cell barrier would be necessitated to permit extravasation of FITC–BSA from vessels of this type (Schmid-Schonbein, 1990a). Macromolecular leak from venules, due to a compromise of endothelial cell integrity, is often associated with discreet ‘hot-spots’ of fluorescence where junctional proteins have failed (Miller et al. 1982; Baldwin Thurston, 2001). The present study detailed an increase in background fluorescence caused by a more generalized flare surrounding the lymphatic vessels. Thus, it is difficult to make conclusions regarding the mechanisms responsible for leakage of FITC–BSA, nor can we firmly conclude whether the extrasplenic lymphatics are of the initial or conducting type. Regardless, the end result is the same; namely, ANP-induced extravasation of protein-rich fluid from the extrasplenic lymphatic vessels and loss of fluid to third spaces. Identifying the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon will form the basis of our future studies.

In summary, we have a developed a new surgical model for studying the extrasplenic microcirculation and lymphatics of rats using fluorescent intravital microscopy. We have confirmed our previous observation that ANP causes greater increases in post- than in precapillary resistance, thus increasing intrasplenic fluid extravasation. We have obtained, for the first time, direct evidence that ANP does indeed increase lymph drainage from the spleen. And we have shown that longer term infusion of ANP also increases the movement of protein across the lymphatic endothelium. This last finding confirms and quantifies previous observations that, in response to volume loading and to ANP infusion, fluid accumulates in the perivascular spaces surrounding the splenic vascular arcades.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. Dr Zoë Brookes gratefully acknowledges her Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Canadian Hypertension Society/Canadian Institutes for Health Research and a travelling Fellowship from the British Heart Foundation.

References

- Andrew PS, Kaufman S. Guanylyl cyclase mediates ANP-induced vasoconstriction of murine splenic vessels. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:R1567–R1571. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00417.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchison DJ, Johnston MG. Atrial natriuretic peptide attenuates flow in an isolated lymph duct preparation. Pflugers Arch. 1996;431:618–624. doi: 10.1007/BF02191911. 10.1007/s004240050043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin AL, Thurston G. Mechanics of endothelial cell architecture and vascular permeability. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2001;29:247–278. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v29.i2.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg S. Hyaluronan turnover in relation to infection and sepsis. J Intern Med. 1997;242:73–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes ZL, Brown NJ, Reilly CS. Differential effects of intravenous anaesthetic agents on the response of rat mesenteric microcirculation in vivo after haemorrhage. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:255–263. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Kaufman S. Splenic blood flow and fluid efflux from the intravascular space in the rat. J Physiol. 1996;490:493–499. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Kaufman S. The influence of reproductive hormones on ANP release by rat atria. Life Sci. 1993;53:689–696. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90245-x. 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90245-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Kaufman S. Influence of atrial natriuretic factor on fluid efflux from the splenic circulation of the rat. J Physiol. 1996;491:225–230. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliades D, Swindall B, Johnston J, Pamnani M, Haddy FJ. Effects of ANP on venous pressures and microvascular protein permeability in dog forelimb. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H272–H279. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endlich K, Steinhausen M. Natriuretic peptide receptors mediate different responses in rat renal microvessels. Kidney Int. 1997;52:202–207. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl G, Bauer B. Coronary arteriolar vasoconstriction in myocardial ischaemia. Vasopressin, renin-angiotensin system and ANP. Eur Heart J. 1990;11:53–57. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/11.suppl_b.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Laurent UB. Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. J Int Med. 1997;242:27–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday MA. Extracellular fluid and its proteins: dehydration, shock, and recovery. Pediatr Nephrol. 1999;13:989–995. doi: 10.1007/s004670050741. 10.1007/s004670050741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben AJ, Krekels MM, Schaper NC, Fuss-Lejeune MJ, Rodriguez SA, de Leeuw PW. Microvascular effects of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) in man: studies during high and low salt diet. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;39:442–450. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00072-8. 10.1016/S0008-6363(98)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley VH, Curry FE, Adamson RH. Quantitative fluorescence microscopy on single capillaries: alphalactalbumin transport. Am J Physiol. 1987a;252:H188–H197. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.1.H188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley VH, Tucker VL, Verburg KM, Freeman RH. Increased capillary hydraulic conductivity induced by atrial natriuretic peptide. Circ Res. 1987b;60:304–307. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman S. Role of spleen in ANP-induced reduction in plasma volume. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1992;70:1104–1108. doi: 10.1139/y92-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman S, Deng Y. Splenic control of intravascular volume in the rat. J Physiol. 1993;468:557–565. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman S, Levasseur J. Effect of portal hypertension on splenic blood flow, intrasplenic extravasation and systemic blood pressure. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:R1580–R1585. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00516.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan KP, Laroque P, Dixit R. Need for dietary control by caloric restriction in rodent toxicology and carcinogenicity studies. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 1998;1:135–148. doi: 10.1080/10937409809524548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley K, Bullard DC, Arbones ML, Bosse R, Vestweber D, et al. Sequential contribution of L- and P-selectin to leukocyte rolling in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;181:669–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.669. 10.1084/jem.181.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipowsky HH, Zweifach BW. Application of the ‘two-slit’ photometric technique to the measurement of microvascular volume tric flow rates. Microvasc Res. 1978;15:93–101. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(78)90009-2. 10.1016/0026-2862(78)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MK, Huxley VH. ANP increases capillary permeability to protein independent of perfusate protein composition. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1139–H1148. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.3.H1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin Grez M, Fleming JT, Steinhausen M. Atrial natriuretic peptide causes preglomerular vasodilatation and post glomerular vasoconstriction in rat kidney. Nature. 1986;324:473–476. doi: 10.1038/324473a0. 10.1038/324473a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FN, Joshua IG, Anderson GL. Quantitation of vasodilator-induced macromolecular leakage by in vivo fluorescent microscopy. Microvasc Res. 1982;24:56–67. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(82)90042-5. 10.1016/0026-2862(82)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman KE. An effective and economical solution for digitizing and analyzing video recordings of the microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2001;8:243–249. doi: 10.1038/sj/mn/7800082. 10.1038/sj.mn.7800082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohhashi T, Watanabe N, Kawai Y. Effects of atrial natriuretic peptide on isolated bovine mesenteric lymph vessels. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H42–H47. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.1.H42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostgaard G, Reed RK. Intravenous saline infusion in rat increases hyaluronan efflux in intestinal lymph by increasing lymph flow. Acta Physiol Scand. 1993;147:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1993.tb09506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER. Deciphering vascular endothelial cell growth factor/vascular permeability factor signalling to vascular permeability. Inhibition by atrial natriuretic peptide. J Biol Chem. 2003;277:44385–44398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202391200. 10.1074/jbc.M202391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly FD. Innervation and vascular pharmacodynamics of the mammalian spleen. Experientia. 1985;41:187–192. doi: 10.1007/BF02002612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubattu S, Volpe M. The atrial natriuretic peptide: a changing view. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1923–1931. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200111000-00001. 10.1097/00004872-200111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid-Schonbein GW. Mechanisms causing initial lymphatics to expand and compress to promote lymph flow. Arch Histol Cytol. 1990a;53:107–114. doi: 10.1679/aohc.53.suppl_107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid-Schonbein GW. Microlymphatics and lymph flow. Physiol Rev. 1990b;70:987–1028. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JF, le Nobel JL, van Essen H, Slaaf DW. Synthetic atrial natriuretic peptide does not increase protein extravasation in rat mesentery. J Hypertens. 1987;5:S45–S47. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan SM, Johnson PC. Effect of oxygen on blood flow autoregulation in cat sartorius muscle. Am J Physiol. 1981;241:H807–H815. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.241.6.H807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultanian R, Deng Y, Kaufman S. Atrial natriuretic factor increases splenic microvascular pressure and fluid extravasation in the rat. J Physiol. 2001;533:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0273b.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0273b.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takubo K, Miyamoto H, Imamura M, Tobe T. Morphology of the human and dog spleen with special reference to intrasplenic microcirculation. Jpn J Surg. 1999;16:29–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02471066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzewik J, Mallipattu SK, Artmann GM, Delano FA, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Evidence for a second valve system in lymphatics: endothelial microvalves. FASEB J. 2001;15:1711–1717. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0067com. 10.1096/fj.01-0067com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela-Rendon J, Manning RD., Jr Chronic transvascular fluid flux and lymph flow during volume-loading hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:H1524–H1533. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.5.H1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber E, Rossi A, Solito R, Sacchi G, Agliano M, Gerli R. Focal adhesion molecules expression and fibrillin deposition by lymphatic and blood vessel endothelial cells in culture. Microvasc Res. 2002;64:47–55. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2002.2397. 10.1006/mvre.2002.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RL, Jones MJ. Atrial, B type, and C type natriuretic peptides cause mesenteric vasoconstriction in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1443–R1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]