Abstract

Very fast ramp stretches at 9.5–33 sarcomere lengths s−1 (l0s−1) stretching speed, 16–25 nm per half-sarcomere (nm hs−1) amplitude were applied to activated intact frog muscle fibres at tetanus plateau, during the tetanus rise, during the isometric phase of relaxation and during isotonic shortening. Stretches produced an almost linear tension increase above the isometric level up to a peak, and fell to a lower value in spite of continued stretching, indicating that the fibre became suddenly very compliant. This suggests that peak tension (critical tension, Pc) represents the tension at which crossbridges are forcibly detached by the stretch. The ratio of Pc to the isometric tension at tetanus plateau (P0) was 2.37 ± 0.12 (s.e.m.). This ratio did not change significantly at lower tension (P) during the tetanus rise but decreased with time during the relaxation and increased with speed during isotonic shortening. At tetanus plateau Pc occurred when sarcomere elongation attained a critical length (Lc) of 10.98 ± 0.13 nm hs−1, independently of the stretching speed. Lc remained constant during the tetanus rise but decreased on the relaxation and increased during isotonic shortening. Length-clamp experiments on the relaxation showed that the lower values of Pc/P ratio and Lc, were both due to the slow sarcomere stretching occurring during this phase. Our data show that Pc can be used as a measure of crossbridge number, while Lc is a measure of crossbridge mean extension. Accordingly, for a given tension, crossbridges on the isometric relaxation are fewer than during the rise, develop a greater individual force and have a greater mean extension, while during isotonic shortening crossbridges are in a greater number but develop a smaller individual force and have a smaller extension.

When ramp stretches are applied to an activated skeletal muscle, tension rises almost linearly up to a point at which a break in tension rise occurs and force peaks and falls, or either rises more slowly or stays constant, depending on the stretching speed (Sugi, 1972; Edman et al. 1978; Flitney & Hirst, 1978a,b; Julian & Morgan, 1981; Lombardi & Piazzesi, 1990; Stienen et al. 1992; Cavagna, 1993; Getz et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2001). In agreement with a previous report (Sugi, 1972), for stretching speed above about 1 sarcomere length s−1 (l0 s−1), tension at the break point, peaks and falls in spite of the continued stretching, indicating that the muscle has became suddenly very compliant. Flitney & Hirst (1978a,b; attributed the increase of muscle compliance to forced crossbridge detachment, as suggested by their observation that, at various sarcomere lengths, critical tension was directly proportional to the overlap between myofilaments, similarly to isometric tension and muscle stiffness. Flitney & Hirst (1978b) also found that the amount of sarcomere elongation (Lc) needed to reach the critical tension was constant at various sarcomere lengths, but changed when the muscle was subjected to a conditioning ramp release prior the stretch. Successive experiments on single skinned fibres from mammalian muscle, showed that changes in peak tension (critical tension, Pc) and Lc also occurred when inorganic phosphate (Pi) (Stienen et al. 1992), phosphate analogue or polyethylene glycol (PEG) were added to the bathing solution (Chinn et al. 2003). These results showed that critical tension and critical length measurements could provide important information about crossbridge properties. With the exception of Sugi's report, all the experiments mentioned above were made using relatively low stretching speeds (up to 2 l0 s−1 at most) so that significant crossbridge cycling occurred during the stretch itself, leading to change in crossbridge properties and population (Lombardi & Piazzesi, 1990; Linari et al. 2000). In the experiments reported here crossbridge cycling was instead minimized by using very fast ramp stretches so that force response, up to the crossbridge breaking, was mainly determined by the crossbridge elasticity. Critical force and critical length were measured in single intact fibres from frog muscle, at the plateau, during the tetanus rise, tetanus relaxation, isotonic shortening and at plateau of submaximal tetanic contractions obtained by using Ringer's solution containing 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM) at various concentrations. Measurements were made on force and sarcomere length changes resulting from the application of ramp stretches at speed up to 33 l0s−1 (ramp time <0.4 ms). These experiments were exclusively aimed at studying the properties of the crossbridges using very fast stretches as a tool, rather than studying the mechanism of force enhancement induced by slow stretching as was extensively done in the past.

Methods

Frogs (Rana esculenta) were killed by decapitation followed by destruction of the spinal cord, according to the procedure suggested by the local ethical committee. Single intact fibres, dissected from the tibialis anterior muscle (4–6 mm long, 60–120 µm diameter) were mounted by means of aluminium foil clips (Ford et al. 1977) between the lever arms of a force transducer (natural frequency 40–60 kHz) and a fast electromagnetic motor in a thermostatically controlled chamber provided with a glass floor for both ordinary and laser light illumination. The experiments were performed at 14°C (±0.2°C) and at about 2.1 µm sarcomere length. Stimuli of alternate polarity, 0.5 ms duration and 1.5 times threshold strength, were applied transversely to the fibre by means of platinum-plate electrodes at the minimum frequency necessary to obtain fused tetani. Sarcomere length was measured using a striation follower device (Huxley et al. 1981) in a fibre segment (1.2–2.5 mm long) selected for striation uniformity in a region as close as possible to the force transducer. In a few experiments, sarcomere length was maintained strictly constant during the relaxation (length-clamp) for a period of 150–200 ms, starting at tetanus plateau, by feeding back to the stretcher electronics the sarcomere length signal from the striation follower. Stretches were applied 0.2–0.5 ms after the end of the length-clamp period, on the assumption that during such a short period the crossbridge population does not change appreciably. Force, fibre length and sarcomere length signals were measured with a digital oscilloscope (4094, Nicolet, USA), and transferred to a personal computer for further analysis. Ringer solution had the following composition (mm): NaCl, 115; KCl, 2.5; CaCl2, 1.8; NaH2PO4, 0.85; Na2HPO4, 2.15. BDM-Ringer solution was obtained by adding the appropriate amount of BDM to Ringer solution to reach the final concentration of 1–5 mm.

Fast ramp-shaped stretches (9.5–33 l0s−1 stretching speed and 16–25 nm hs−1 amplitude) were applied to one fibre end while force response was measured at the other end. It was assumed throughout the paper, that the stretching speed was high enough to reduce crossbridge cycling to a negligible extent during the stretch, so that the force response could be attributed to the crossbridges present just before the stretch. Passive force response was negligible and no correction was made for it. Fibres developing the maximum tetanic tension were easily damaged by the stretches used here. In general only a limited number of stretches (30–50) could be applied before the sarcomere length along the fibre became inhomogeneous. This was the first sign of damage which led to a progressive reduction of the sharpness of the force change at critical length. Data from inhomogeneous fibres were not included in the analysis. The damage was very much reduced when stretches were applied to fibres developing low tension, such as during the tetanus rise, relaxation or isotonic shortening. In some experiments stretches were applied at the plateau of submaximal tetani of various amplitudes, obtained by perfusing the fibre with BDM, a well known crossbridge inhibitor (Horiuti et al. 1988; Bagni et al. 1992). Isotonic data were obtained by releasing the tetanized fibre with a given shortening velocity and applying the stretches when the isotonic tension reached the steady value.

Results

Characteristics of force response to fast stretches

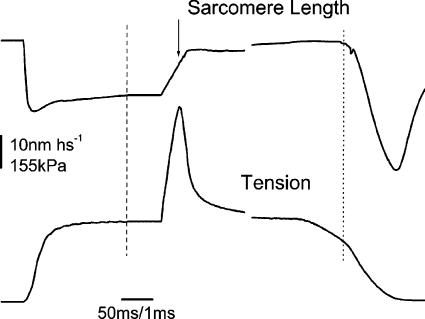

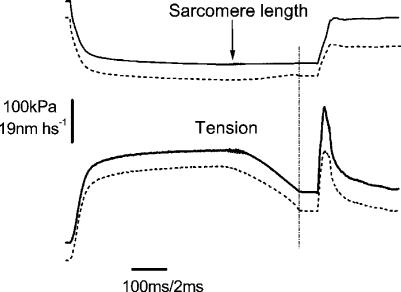

Figure 1 shows a typical force response to a fast stretch applied at tetanus plateau in a single muscle fibre. Tension rises steeply and almost linearly during the stretch up to a point at which it stops growing, reaching a peak and then dropping towards a lower value in spite of the continuous stretching of the sarcomeres. This means that at tension peak, instantaneous fibre stiffness drops to very low and even negative values, due to forced crossbridge detachment. The force record is similar to those reported previously in the literature by a number of researchers, however, due to the much higher stretching speed used here, the tension peak is much sharper and its amplitude is slightly greater than previously found. The ratio of critical tension at plateau (Pc0) to plateau tension (P0) measured in 10 fibres at a mean stretching speed of 19.6 ± 2.36 l0s−1 was 2.37 ± 0.12 (s.e.m.) a value smaller than the ratio of 3.2 found recently in skinned mammalian fibres (Getz et al. 1998) but greater than the ratio of about 2 reported for frog intact preparation at lower stretching speed (see Getz et al. 1998 and references therein). The latter difference is probably due to the faster stretches used here, since critical tension increases slightly with stretching speed (Flitney & Hirst, 1978a; our data not shown).

Figure 1. Force response of a single intact muscle fibre to a fast ramp stretch applied at tetanus plateau.

The peak tension reached during the stretch represents the tension necessary to break the attached crossbridges. The arrow on the sarcomere length signal indicates the time of the tension peak. Broken vertical line and short break on the record indicate the start and the end of the fast time base recording. The vertical dotted line shows the end of the isometric phase of relaxation after which sarcomere length along the fibre starts to become inhomogeneous as indicated by the great shortening occurring beyond this point. Time elapsed during the break, 44 ms. Stretching speed: 14.7 l0 s−1.

Tetanus rise and relaxation

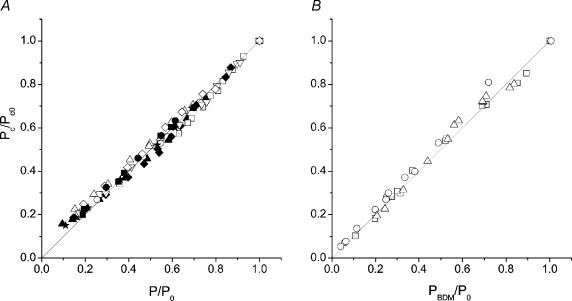

If Pc is the force needed to forcibly detach the crossbridges, its value would depend on both the properties of the individual acto-myosin bond and the number of bonds. Therefore the critical force should represent a measure of the number of attached crossbridges during muscle activity as long as crossbridges maintain their properties and act independently from each other. To test this point we measured Pc under conditions in which it is usually assumed that force is proportional to attached crossbridge number as during the tetanus rise. Stretches were therefore applied at different tension levels (P) on the tetanus rise. The results are shown in Fig. 2A as a plot of critical tension against P/P0 ratio. Critical tension data were normalized by plotting for each fibre the ratio between critical tension on the rise and critical tension at plateau (Pc0). It can be seen that, with the exception of a small deviation at around 0.25 P0, critical tension increases linearly with isometric tension, suggesting a direct proportionality with crossbridge number. Similar results (Fig. 2B) were obtained when the stretches were applied at plateau of submaximal tetanic forces (PBDM) obtained by using BDM-Ringer solution at different concentrations. The relationship between Pc and tetanic tension is almost perfectly linear suggesting that, similarly to the tetanus rise, critical force is directly proportional to crossbridge number.

Figure 2. Critical tension as a function of relative tension during the tetanus rise (A) and relative plateau tensions in presence of various BDM concentrations (B).

Different symbols represent different experiments from 10 (tetanus rise) and 3 (BDM data) fibres. The lines on the graphs represent the direct proportionality. The slight deviation from the linearity at low tensions on the tetanus rise, is probably due to the small sarcomere shortening occurring during this phase, which tends to increase the critical tension. The deviation is not present on BDM data since no sarcomere shortening was occurring during the stretch application.

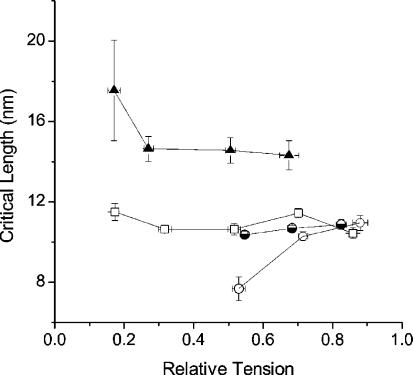

Figure 4 shows that Lc, measured during the tetanus rise in the same group of fibres of Fig. 2A, is independent of the tension developed being constant at a mean value of 10.98 ± 0.13 nm hs−1. Lc was also found to be independent of tension in BDM experiments (data not shown). These findings are somewhat surprising since the portion of Lc absorbed by the filament compliance (assumed Hookean) which is about 50% of the sarcomere compliance at tetanus plateau (Huxley et al. 1994; Wakabayashi et al. 1994), should decrease at lower tensions (lower Pc), reducing the value of Lc needed to elongate the crossbridges to their rupture length. To calculate the effect of filament compliance on Lc it is necessary to take into account the complicated parallel-series network in which filament and crossbridge compliances are arranged in the sarcomere. For this purpose, calculations were made with the distributed model of Forcinito et al. (1997); that is best suited when crossbridge number is small. With the assumption above that crossbridges and myofilaments at tetanus plateau have the same compliance, calculations show that at tensions of 0.52 P0 and 0.26 P0, Lc should decrease, relative to the plateau value, to 0.77 and 0.65, respectively.

Figure 4. Critical length at various relative tensions during tetanus rise, isotonic shortening, isometric and length–clamp relaxation.

Lc is constant during the tetanus rise (□), while at low tensions it increases during the shortening (▴) and decreases during relaxation (○). This last effect is not present when relaxation data are obtained under length-clamp conditions (half-filled circles). Mean and s.e.m. from 6 (isotonic), 10 (rise), 5 (relaxation) and 4 (relaxation in length-clamp) experiments.

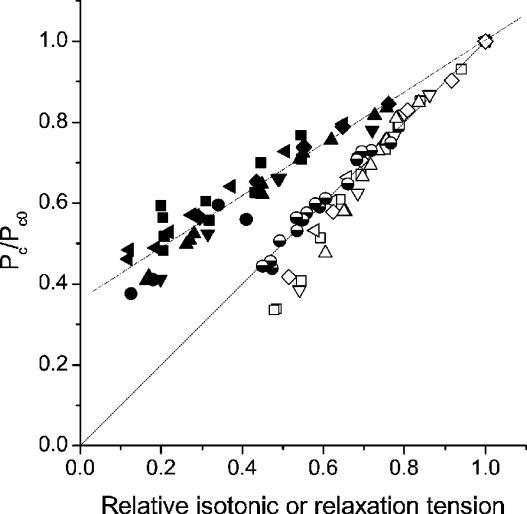

Measurements on the tetanus relaxation were performed exclusively during the so-called isometric phase (from P0 down to about 0.48–0.55 P0), occurring before the development of sarcomere length disorder (see Fig. 1). The results shown in Fig. 3 indicate a clear difference with respect to the tetanus rise and BDM data. The proportionality between P/P0 and critical tension holds in fact only for the initial part of the isometric relaxation. At tensions <0.7 P0 there is a clear deviation from the direct proportionality and the ratio Pc/Pc0 is smaller than on the tetanus rise. This suggests that for a given tension, there are fewer crossbridges during the relaxation than on the rise, which in turn means that these crossbridges develop a greater mean force. It is interesting that critical length too is different from tetanus rise (Fig. 4). At tension of 0.53 P0, critical length was 7.69 nm hs−1 as compared to 10.98 nm hs−1 measured on the rise (see Table 1).

Figure 3. Critical tension as a function of relative tension during isotonic shortening, and during relaxation in normal and length-clamped conditions.

Open symbols refer to data on the isometric relaxation (5 fibres). Half-filled symbols refer to experiments in which sarcomere length was clamped during relaxation. Length-clamp eliminated the deviation from linearity present on the isometric relaxation. For clarity only one experiment is plotted, but similar results were obtained in all the four experiments carried out. The isotonic data (6 fibres, filled symbols) were fitted (broken line) by the linear equation: Pc= 0.362 + 0.64 P/P0. The intercept of this equation on the ordinate (zero isotonic tension), shows that Pc is 0.36 the plateau value. This means that at Vmax, attached crossbridges are still 36% of crossbridges attached at plateau of an isometric tetanus. Different symbols represent different experiments.

Table 1.

Critical tension and critical length during various phases of muscle activity

| P/P0 | Pc/Pc0 | Lc (nm hs−1) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetanus rise | 0.52 ± 0.018 | 0.53 ± 0.021 | 10.64 ± 0.29 | 11 |

| Isotonic shortening | 0.50 ± 0.015 | 0.69 ± 0.014* | 14.57 ± 0.65* | 12 |

| Relaxation | 0.53 ± 0.018 | 0.40 ± 0.032* | 7.69 ± 0.57* | 6 |

| Length-clamped relaxation | 0.55 ± 0.008 | 0.52 ± 0.016 | 10.38 ± 0.17 | 12 |

P < 0.05.

The striation follower output showed that during the isometric phase of relaxation, sarcomeres in the monitored segment elongated slowly. For the experiments of Fig. 4 at a mean tension of 0.57 ± 0.015 P0, elongation speed was 0.055 ± 0.016 l0s−1. This effect is due to the elastic recoil of the tendon compliance occurring during the fall of tension. Since sarcomere stretching could explain both the higher individual crossbridge force and the smaller Lc measured during this phase, we performed a few experiments in which stretch application was preceded by a period of 150–200 ms during which sarcomere length was clamped, as described in the method section, to eliminate the elongation. A sample record obtained with this technique is compared with a normal isometric record in Fig. 5. Length-clamp increased significantly the critical force in response to the same stretch, eliminating the non-proportionality between P/P0 and Pc/P0 found on the relaxation. Thus, length-clamp data lie on the same proportionality line as tetanus rise data (Fig. 3). As expected, length-clamp also eliminated the decrease of Lc occurring during the relaxation (Fig. 4). The mean Pc/Pc0 and Lc values found in four length-clamp experiments were not significantly different from the tetanus rise (Table 1).

Figure 5. Effect of sarcomere length-clamp on the force response to the stretch on the tetanus relaxation.

Continuous lines, length-clamp; short broken lines, isometric contraction from the same fibre. Records in length clamp are shifted upward for clarity. Note the slow sarcomere lengthening occurring during the isometric phase of relaxation and its disappearance upon length-clamping. Critical force and critical length are both increased by the length-clamp procedure. The broken vertical line indicates the change from the slow to the fast sampling. Length clamp starts at the vertical arrow and ends 0.5 ms before the stretch.

Isotonic shortening

Isotonic measurements were made by applying the stretches on the steady isotonic tension during shortening at constant velocity. The pooled data for six experiments reported in Fig. 3 show that, differently from the tetanus rise, isotonic critical tension decreases less than proportionally with tension, increasing progressively over isometric Pc as tension decreases. This suggests that, for a given tension, crossbridge number is greater during the shortening. Consequently crossbridges operating under isotonic shortening develop a smaller individual force respect to isometric crossbridges. The lower the isotonic tension, the greater the number of crossbridges and the smaller is their individual force. At the tension of 0.53 P0, Pc was about 32% greater than the isometric value. Shortening also increased the critical length with respect to the tetanus rise (Fig. 4) and at tension of 0.5 P0, Lc was about 33% greater than on the tetanus rise. This finding suggests that isotonic crossbridges have a shorter mean extension then isometric crossbridges. The increase of crossbridge number during the shortening is in good agreement with previous stiffness measurements (Julian & Sollins, 1975; Ford et al. 1985; Griffiths et al. 1993) and with Huxley's (1957) model of muscle contraction. It is interesting that Huxley's model also predicts a reduction of the crossbridge mean length during the shortening, in accordance with our experimental findings.

Critical tension and critical length values (± s.e.m.) measured for n data during the tetanus rise, isotonic shortening, relaxation and length-clamp relaxation, are summarized in Table 1. Compared to the data on the tetanus rise, significant changes (P < 0.05) occur on both Pc and Lc during isotonic shortening and isometric relaxation. Length-clamp during relaxation eliminated the differences with the tetanus rise.

Discussion

Force responses of activated whole muscles or single fibres either intact or skinned, to stretches have been extensively studied in the past (Sugi, 1972; Edman et al. 1978; Flitney & Hirst, 1978a; Julian & Morgan, 1981; Lombardi & Piazzesi, 1990; Stienen et al. 1992; Cavagna, 1993; Getz et. al. 1998; Linari et al. 2000; Lee et al. 2001; Rassier & Herzog, 2004). Most of these studies investigated the mechanism of force enhancement occurring during and after the stretch, using low stretching speed (< 2 l0 s−1) similar to those naturally occurring during in vivo activity. In the experiments reported here, stretches were instead used to investigate crossbridge properties, and very high speeds were used to minimize the changes of crossbridge population during the stretch itself, so that force response was mainly determined by the elastic properties of the crossbridges present at the time of the stretch.

Based on their finding that peak tension response to stretches in active muscles, was directly proportional to muscle stiffness and to the extent of overlap between myofilaments, Flitney & Hirst (1978a) suggested that critical tension (their Ps2) was directly proportional to crossbridge number, representing the sum of the individual resistance to breaking of all the crossbridges. Consequently, critical length represented the amount of muscle elongation needed to increase the load on the crossbridges up to the rupture value. Studies of critical force and critical length could therefore provide important information on crossbridge number and properties during various phases of muscle activity.

Our Pc/P ratio and Lc values are in general agreement with those reported on literature. The mean Pc/P ratio of 2.37 ± 0.12 found on the tetanus rise and at plateau, is slightly greater than the values reported previously for intact frog preparation. This is probably due to the higher stretching speed used here, since the Pc/P ratio increases slightly with the stretching speed above 0.5 l0s−1 (Flitney & Hirst, 1978a; our data not shown). A significantly higher ratio of about 3.2 was reported by Getz et al. (1998) in rabbit skinned fibres at 5°C, but this difference is probably attributable to the lower experimental temperature, since the Pc/P ratio has been shown to increase by lowering the temperature (Chinn et al. 2003). On the tetanus rise and at plateau, Lc was 10.98 ± 0.13 nm hs−1, similar to the values reported previously on single intact or skinned fibres in which length changes were measured at sarcomere level (10–12 nm hs−1, Lombardi & Piazzesi, 1990; 8 nm hs−1, Getz et al. 1998). The relatively high value of 16 nm hs−1 reported by Stienen et al. (1992) is probably attributable to the effect of the fibre end compliance which was not eliminated by measuring the length change at sarcomere level.

During the tetanus rise, the critical force was directly proportional to the isometric tension, exactly as expected if the tension development is due to a progressive increase of attached crossbridges all having the same properties. This result disagrees somewhat with previous stiffness data (another putative crossbridge number measure) showing that crossbridge number grows more than proportionally during the tetanus rise (Cecchi et al. 1982). The discrepancy is mainly due to the effect of myofilament compliances on sarcomere stiffness, which tends to increase the stiffness/tension ratio when crossbridge number decreases. On the contrary, filament compliance simply transmits the force to the crossbridges and has no effect on critical tension. Pc is also insensitive to the quick force recovery which, by truncating the force response during the length change, reduces the measured stiffness (Ford et al. 1977).

BDM-Ringer data give further support to the idea that critical tension is proportional to crossbridge number. In fact, when tetanic tension is inhibited to various degrees by different BDM concentrations, the critical force is correspondingly reduced in a very linear way (Fig. 2). This finding seems to be at odds with recent data by Rassier & Herzog (2004) reporting that, at stretching speed of 0.4 l0 s−1 in the presence of BDM, peak tension decreases less than isometric tension. However, this contradiction is only apparent, as the peak tension in Rassier and Herzog's experiments does not correspond to the critical tension, as in our case. At low stretching speed, in fact, the tension rise suddenly slows down at the critical length attainment, but continues to increase up to the end of the stretch. Therefore, in contrast to our results, the tension peak is attained at the end of the stretch and it is proportional to its amplitude. The increase in force beyond the critical tension could occur because tension increase due to crossbridge recruitment during the relatively long-lasting slow stretches (Linari et al. 2000), overcomes the tension loss due to crossbridge breaking. Crossbridge recruitment was instead considered negligible in our experiments, and the force response was attributed to the crossbridge elastic properties. This assumption was based on published data showing that crossbridge attachment and detachment elicited by fast stretches have a combined time constant of about 14 ms at 4°C and contribute to the force response for about 15%P0 (Piazzesi et al. 1997). Calculations made considering that our experiments were carried out at 14°C with stretches of 10.98 nm hs−1 amplitude and 0.53 ms mean duration, showed that crossbridge cycling cannot contribute more than 1.5%P0 to our force responses, corresponding to about 1% of the mean critical tension. The much faster kinetics of weakly binding bridges was not considered here, since at normal ionic strength in frog muscle fibres there is no mechanical evidence for these bridges (Bagni et al. 1995).

It should be mentioned that, according to the data in the literature (Bagni et al. 1994; Edman & Tsuchiya, 1996; Rassier & Herzog, 2004), the force response of activated fibres to stretches, contains a contribution from non-crossbridge structure(s) proportional to the length change and independent of the stretching speed. However, for the stretches used here, it can be calculated that this contribution amounts to only 0.7–1% of the force response and therefore no correction was made for it.

Figure 4 shows that Lc is independent of the tension developed by the fibre and therefore independent of the crossbridge number. This result is consistent with the data of Flitney & Hirst (1978a) showing that Lc measured at plateau of tetanic contractions at different sarcomere length, was constant, but it is in contrast with the calculation reported in the Results section, showing that Lc is expected to decreases significantly at low tensions, due to filament compliance. This discrepancy could be due to two possible mechanisms. Lc could be affected by the quick force recovery which decreases the effects of the stretch, making necessary the application of greater length to reach the breaking force. Since the speed of the quick recovery increases at low tensions on the tetanus rise (Ford et al. 1986; Bagni et al. 1988), Lc would tend to increase, counteracting the effects of filament compliance. The other possibility is that filament compliance may be not linear, as suggested previously (Bagni et al. 1999 and references therein). Assuming that filament compliance is inversely proportional to tension, it can be shown that Lc does not change during the tetanus rise as found here.

The observation that for a given tension Pc is smaller on the tension fall during relaxation than on the tension rise during activation (Table 1), suggests that a smaller number of crossbridges generating a greater individual force is present on the relaxation. At the same time, Lc data show that these bridges are extended by 2.95 nm hs−1 more than isometric crossbridges. These effects are both due to the slow sarcomere elongation occurring during the isometric phase of relaxation. In fact, if the sarcomere lengthening is abolished by the length-clamp, the Pc/Pc0 ratio becomes exactly proportional to the P/P0 ratio and Lc increases up to the tetanus rise value (Fig. 3). Therefore, sarcomere stretching, even at very low speed, increases both crossbridge mean extension and mean force.

Data in Fig. 3 show that for a given relative tension, the number of crossbridges is greater during isotonic shortening than during isometric contraction, indicating a smaller mean crossbridge force during the shortening, just the opposite of that found during the relaxation under isometric conditions. As indicated by the greater Lc required to reach the critical tension compared to the tetanus rise, the smaller crossbridge force is attributable to a smaller crossbridge mean extension. According to Table 1, crossbridge extension is reduced by 3.93 nm h−1 during shortening. This effect can be explained by assuming that shortening shifts the crossbridge population towards a low force-generating state or even to a negative force state as suggested by a crossbridge model (Huxley, 1957) and by the finding that at the unloaded shortening velocity (Vmax) a consistent number of crossbridges is still attached (Fig. 3). The reduction of crossbridge mean length during the shortening is consistent with the recent finding (Reconditi et al. 2004) showing that power stroke amplitude increases with lowering of the load. Shorter crossbridges are less strained and this reduces the detachment rate from actin allowing the execution of a longer power stroke before detachment.

Changes in Lc and Pc were induced by muscle activity (Flitney & Hirst, 1978b) and, in skinned fibres, by changes in the bathing solution composition. Stienen et al. (1992) found that addition of inorganic phosphate (Pi), increased both the critical length and the Pc/P ratio. Similarly to our results during isotonic shortening, these effects were attributed to a shift of the crossbridge population towards a low force-generating state, as expected if Pi release is coupled to the power stroke. Pc/P ratio increased also when polyethylene glycol (PEG) was added to the bathing solution (Chinn et al. 2003). To explain this effect it was suggested that PEG increased the distension of prepower stroke crossbridges, which were considered responsible for the increase in force during the stretch.

Throughout the paper we assumed that the force response to the stretch, up to the rupture force, was due to the elongation of the sarcomere elasticity, similarly to previous reports using step length changes of similar speed (Ford et al. 1977). From their data on skinned mammalian fibres at low stretching velocity, Getz et al. (1998) suggested that stretch tension could be due to a shift of the prepower stroke crossbridges into a region of high force induced by the stretch. Our data do not exclude this possibility, however, to explain the proportionality between tension and Pc on the tetanus rise it would be necessary for prepower stroke state crossbridges, to be a fixed fraction of the total attached crossbridges. In these terms, isotonic data would suggest a greater proportion of prepower state crossbridges to account for the smaller crossbridge extension and the lower tension developed.

To summarize, our results show that critical force represents the force at which crossbridges are forcibly detached while critical length represents the elongation needed to raise the crossbridge force up to the rupture value. During the tetanus rise, critical force is directly proportional to the number of attached crossbridges all having the same individual force and extension. Shortening decreases crossbridge mean force and extension while the opposite occurs during the slow sarcomere lengthening present on the isometric phase of relaxation; abolition of lengthening by the length-clamp procedure, eliminates the difference with the tetanus rise.

Acknowledgments

Supported by University of Florence and Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze (n. 2003. 1772).

References

- Bagni MA, Cecchi G, Colombini B, Colomo F. Sarcomere tension-stiffness relation during the tetanus rise in single frog muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1999;20:469–476. doi: 10.1023/a:1005582324129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni MA, Cecchi G, Colomo F, Garzella P. Effects of 2,3-butanedione monoxime on the crossbridge kinetics in frog single muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1992;13:516–522. doi: 10.1007/BF01737994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni MA, Cecchi G, Colomo F, Garzella P. Development of stiffness precedes cross-bridge attachment during the early tension rise in single frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1994;4812:273–278. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni MA, Cecchi G, Colomo F, Garzella P. Absence of mechanical evidence for attached weakly binding cross-bridges in frog relaxed muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1995;482:391–400. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagni MA, Cecchi G, Colomo F, Tesi C. The mechanical characteristics of the contractile machinery at different levels of activation in intact single muscle fibres of the frog. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;226:473–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavagna GA. Effect of temperature and velocity of stretching on stress relaxation of contracting frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1993;462:161–173. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi G, Griffiths PJ, Taylor SR. Muscular contraction: kinetics of crossbridge attachment studied by high-frequency stiffness measurements. Science. 1982;217:70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.6979780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinn M, Getz EB, Cooke R, Lehman SL. Force enhancement by PEG during ramp stretches of skeletal muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2003;24:571–578. doi: 10.1023/b:jure.0000009846.05582.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman KAP, Elzinga G, Noble MIM. Enhancement of mechanical performance by stretch during tetanic contractions of vertebrate skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1978;281:139–155. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman KAP, Tsuchiya T. Strain of passive elements during force enhancement by stretch in frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1996;490:191–205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flitney FW, Hirst DG. Cross-bridge detachment and sarcomere ‘give’ during stretch of active frog's muscle. J Physiol. 1978a;276:449–465. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flitney FW, Hirst DG. Filament sliding and energy absorbed by the crossbridges in active muscle subjected to cyclical length changes. J Physiol. 1978b;276:467–479. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcinito M, Epstein M, Herzog W. Theoretical consideration on myofibril stiffness. Biophys J. 1997;72:1278–1286. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78774-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford LE, Huxley AF, Simmons RM. Tension responses to sudden length changes in stimulated frog muscle fibres near slack length. J Physiol. 1977;269:441–515. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford LE, Huxley AF, Simmons RM. Tension transients during steady shortening of frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1985;361:131–150. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford LE, Huxley AF, Simmons RM. Tension transients during the rise of tetanic tension frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1986;372:595–609. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz EB, Cooke R, Lehman SL. Phase transition in force during ramp stretches of skeletal muscle. Biophys J. 1998;75:2971–2983. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77738-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths PJ, Ashley CC, Bagni MA, Maeda Y, Cecchi G. Cross-bridge attachment and stiffness during isotonic shortening of intact single muscle fibers. Biophys J. 1993;64:1150–1160. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81481-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuti K, Higuchi H, Umazume Y, Konishi M, Okazaki O, Kurihara S. Mechanism of action of 2,3-butanedione2-monoxime on contraction of frog skeletal muscle. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1988;9:156–194. doi: 10.1007/BF01773737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley AF. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem. 1957;7:255–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley AF, Lombardi V, Peachey LD. A system for fast recording of longitudinal displacement of a striated muscle fibre. J Physiol. 1981;317:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Huxley HE, Stewart A, Sosa H, Irving CT. X-ray diffraction measurements of the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments in contracting muscle. Biophys J. 1994;67:2411–2421. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80728-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian FJ, Morgan DL. Variation of muscle stiffness with tension during tension transients and constant velocity shortening in the frog. J Physiol. 1981;319:193–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian FJ, Sollins MR. Variation of muscle stiffness with force at increasing speeds of shortening. J Gen Physiol. 1975;66:287–302. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.3.287. 10.1085/jgp.66.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HD, Herzog W, Leonard T. Effects of cyclic changes in muscle length on force production in in-situ cat soleus. J Biomech. 2001;34:979–987. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00077-x. 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00077-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linari M, Lucii L, Reconditi M, Vanicelli Casoni ME, Amenitsch H, Bernstorff S, Piazzesi G, Lombardi V. A combined mechanical and X-ray diffraction study of stretch potentiation in single frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2000;526:589–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00589.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi V, Piazzesi G. The contractile response during steady lengthening of stimulated frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1990;431:141–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazzesi G, Linari M, Reconditi M, Vanzi F, Lombardi V. Corss-bridges detachment and attachment following a step stretch imposed on active single frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1997;498:3–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassier DE, Herzog W. Active force inhibition and stretch-induced force enhancement in frog muscle treated with BDM. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1395–1400. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00377.2004. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00377.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reconditi M, Linari M, Lucii L, Stewart A, Sun YB, Boesecke P, Narayanan T, Fischetti RF, Irving T, Piazzesi G, Irving M, Lombardi V. The myosin motor in muscle generates a smaller and slower working stroke at higher load. Nature. 2004;428:578–581. doi: 10.1038/nature02380. 10.1038/nature02380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stienen GJM, Versteeg PGA, Papp Z, Elzinga G. Mechanical properties of skinned rabbit psoas and soleus muscle fibres during lengthening: effects of phosphate and Ca2+ J Physiol. 1992;451:503–523. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugi H. Tension changes during and after stretch in frog muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1972;225:237–253. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakabayashi K, Sugimoto Y, Tanaka H, Hueno Y, Takezaw Y, Amemiya Y. X-ray diffraction evidence for the extensibility of actin and myosin filaments during muscle contraction. Biophys J. 1994;67:2422–2435. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80729-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]