Abstract

Illumination of the receptive-field surround reduces the sensitivity of a retinal ganglion cell to centre illumination. The steady, antagonistic receptive-field surround of retinal ganglion cells is classically attributed to the signalling of horizontal cells in the outer plexiform layer (OPL). However, amacrine cell signalling in the inner plexiform layer (IPL) also contributes to the steady receptive-field surround of the ganglion cell. We examined the contributions of these two forms of presynaptic lateral inhibition to ganglion cell light sensitivity by measuring the effects of surround illumination on EPSCs evoked by centre illumination. GABAC receptor antagonists reduced inhibition attributed to dim surround illumination, suggesting that this inhibition was mediated by signalling to bipolar cell axon terminals. Brighter surround illumination further reduced the light sensitivity of the ganglion cell. The bright surround effects on the EPSCs were insensitive to GABA receptor blockers. Perturbing outer retinal signalling with either carbenoxolone or cobalt blocked the effects of the bright surround illumination, but not the effects of dim surround illumination. We found that the light sensitivities of presynaptic, inhibitory pathways in the IPL and OPL were different. GABAC receptor blockers reduced dim surround inhibition, suggesting it was mediated in the IPL. By contrast, carbenoxolone and cobalt reduced bright surround, suggesting it was mediated by horizontal cells in the OPL. Direct amacrine cell input to ganglion cells, mediated by GABAA receptors, comprised another surround pathway that was most effectively activated by bright illumination. Our results suggest that surround activation of lateral pathways in the IPL and OPL differently modulate the sensitivity of the ganglion cell to centre illumination.

The classical receptive fields of retinal ganglion cells are organized into antagonistic centre and surround regions. Illumination of the receptive-field surround reduces the sensitivity of the ganglion cell to centre illumination (Sakmann & Creutzfeldt, 1969; Thibos & Werblin, 1978). The neural circuitry that contributes to the ganglion cell surround is unclear because lateral signalling pathways in both the outer plexiform layer (OPL) and the inner plexiform layer (IPL) could contribute. Ganglion cell responses to steady surround illumination have been attributed to horizontal cell signalling in the OPL. These signals give rise to the surround responses in bipolar cells, which were thought in turn to mediate the ganglion cell surround (Werblin, 1974; Thibos & Werblin, 1978; McMahon et al. 2004). Supporting this notion, hyperpolarizing horizontal cells with current mimics the surround response in ganglion cells (Naka & Witkovsky, 1972; Mangel, 1991). Lateral signalling in the IPL, by contrast, was thought to mediate change-sensitive lateral inhibition and not the steady surround in ganglion cells (Werblin, 1972).

Recent work suggests that the contributions of OPL- and IPL-mediated lateral signalling are not this straightforward, and indicate that lateral signalling in the IPL mediates a component of the steady surround response in ganglion cells (Cook & McReynolds, 1998a; Taylor, 1999; Flores-Herr et al. 2001). Thus, lateral interactions in both the OPL and IPL could contribute to the ganglion cell steady surround, as suggested by Naka (1977).

In this study, we investigated how steady, presynaptic lateral inhibition in the OPL and IPL contributes to ganglion cell surround responses. Dim surround stimuli reduced the sensitivity of the ganglion cells to central illumination. GABAC receptor antagonists, which act primarily at bipolar cell axon terminals in salamander (Lukasiewicz et al. 1994; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a) and do not affect horizontal cell signalling to cones (Kamermans et al. 2001; Verweij et al. 2003) or bipolar cells (Hare & Owen, 1996; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a), blocked the reduction in light sensitivity. Brighter steady surround illumination caused a further reduction in ganglion cell light sensitivity that was unaffected by GABA receptor antagonists. Carbenoxolone and cobalt (< 10 μm), which reduce horizontal cell to cone signalling (Kamermans et al. 2001; Verweij et al. 2003), decreased the effect of the bright, but not dim, surround illumination, suggesting that this component was mediated by horizontal cells. We also assessed the role of the direct inhibitory pathway from amacrine cells to ganglion cells by recording light-evoked IPSCs. Unlike the IPL pathway to bipolar cells, this pathway was activated primarily by bright, and less by dim, illumination. Thus, lateral inhibition in both plexiform layers affects ganglion cell light sensitivity.

Methods

Slice preparation

Larval tiger salamanders obtained from Charles Sullivan (Nashville, TN, USA) were kept in aquaria at 5°C on a 12 h light–dark cycle. Salamanders were anaesthetized in an ice bath until they were immobilized, and then decapitated and pithed before the eyes were enucleated. The experimental protocol was approved by the Washington University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Eyes were dark-adapted for at least 1 h before dissection. Dissection and recording procedures were performed under dim red illumination. Retinal slices were prepared as described by Lukasiewicz et al. (1994) and sliced at 300-μm intervals. For whole mount preparations, the isolated retina was cut into two pieces, which were placed in a chamber, ganglion cell side up, and were immobilized with nylon netting. Individual slices or retinal pieces were transferred to a recording chamber and viewed through an upright, fixed-stage microscope (Eclipse E-600-FN; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with a 40 × water-immersion lens and Hoffman modulation contrast optics. Using a gravity-fed perfusion system, the preparation was continuously superfused with a Ringer solution containing (mm): NaCl 112, KCl 2, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, glucose 5 and Hepes 5; pH adjusted to 7.8 with NaOH.

Whole-cell recording

Electrodes were pulled from borosilicate glass (IB150F-4; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) with a P-97 Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA). Whole-cell recordings were made from ganglion cells by using 5-MΩ pipettes filled with solution containing (mm) caesium gluconate 95.25, TEA-Cl 8, MgCl2 0.4, EGTA 1 and Na-Hepes 10; pH adjusted to 7.5 with HCl. Lucifer yellow (0.1%, Aldrich Chemical Co, Milwaukee, WI, USA) was added to the pipette solution to identify ganglion-cell morphologies after electrophysiological recordings. Membrane potentials were corrected for junction potentials (−14.9 mV).

The voltage-clamp recordings were made with either 3900A Integrating Patch Clamp (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or Axopatch 200A (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Data were digitized and stored with a personal computer using TL-1 data acquisition system (Axon Instruments). Patchit software (White Perch Software, Somerville, MA, USA) was used to generate voltage command outputs, acquire data, control the light stimuli, and operate the drug superfusion system. Data were filtered at 1 kHz with a four-pole Bessel filter and were sampled at 0.5–10 kHz.

Drugs

The entire recording chamber was superfused by a gravity-fed perfusion system. A computer-controlled superfusion system was used to apply drug-containing Ringer solutions. For all experiments, glycine receptors were blocked with strychnine (5 μm). The GABAB receptor antagonist CGP55845 was obtained from Tocris Cookson (Ballwin, MO, USA). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA).

Light stimulation

Centre and surround illumination were controlled separately. Red centre illumination (diameter, 180 μm) was obtained by placing a band-pass filter (peak wave length (λmax) = 633 nm) in front of a tungsten–halogen light source. The centre stimulus was projected through the objective lens via a light pipe attached to the microscope camera port and presented every 30–60 s. The intensity of the unattenuated light stimulus in the plane of the preparation was equivalent to 4.52 × 108 photons μm−2 s−1 of 633-nm monochromatic light. Centre spot intensity was varied with neutral density filters. The surround stimulus was an annulus that was projected through the microscope condenser. The annulus pattern (for slice preparations: i.d., 300 μm; o.d. 2300 μm; and for isolated retina preparations: i.d., 800 μm; o.d., 3000 μm) was generated by masking the centre of the light path. A red light-emitting diode (LED) (λmax= 635 nm, HLMP3750A; Digi-Key, Thief River Falls, MN, USA) was used for the surround light source. Surround light intensity was controlled by varying the LED current. The maximum, unattenuated intensity of the LED was 1.53 × 106 photons μm2 sec1 at 635 nm.

Intensity–response functions were generated by plotting the EPSC at light onset (ON -EPSC) amplitude as a function of centre light intensity. Intensity–response relations were generated in either the absence or presence of surround illumination. Surround illumination was presented from 5 to 10 s prior to, and until the end of, centre stimulation. Similar stimulus durations used in previous studies did not result in desensitization of surround responses (Sakmann & Creutzfeldt, 1969; Thibos & Werblin, 1978; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a). Surround light intensity was of dim (−3 log) or bright (−1 to 0 log) intensity. After obtaining responses in control Ringer solution, responses were then obtained in the presence of drug-containing solutions.

For experiments with carbenoxolone we needed to obtain the light intensity–response relations rapidly. To accomplish this, we ramped the centre light stimulus intensity (diameter, 180 μm; λmax, 635 nm) by increasing the current to a red LED in incremental steps (each step was 0.5–1.0 log unit, 100–150 ms) (see Fig. 6A) (Werblin, 1971). The intensity of the unattenuated light stimulus in the plane of the preparation was similar to that of the tungsten–halogen light source (4.54 × 108 photons μm−2 s−1 at 635 nm). The threshold level to evoke an EPSC was first determined using conventional light-intensity steps. The ramp stimulus was varied from background response threshold intensity to saturation in less than a second. The ramp stimulus was presented every 60 s. Bright surround illumination was presented in combination with centre illumination as described above.

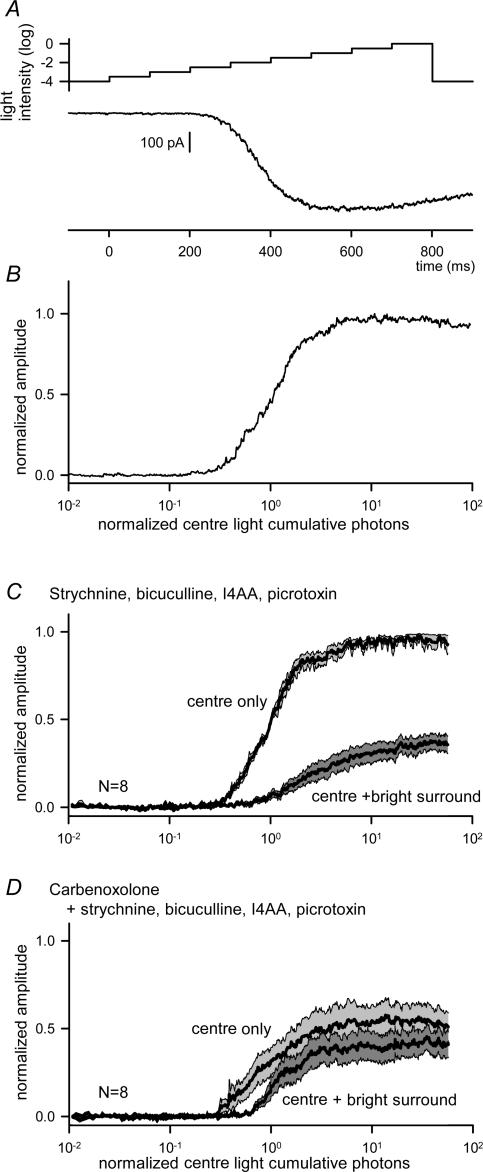

Figure 6. Carbenoxolone reduced the inhibition by bright surrounds.

A, ramp-light stimulation protocol consisted of 100 ms and 0.5 log intensity steps from −4 log to 0 log attenuation (upper trace) and a representative EPSC in response to the ramp light stimulation in the presence of strychnine, bicuculline, I4AA and picrotoxin (lower trace). B, the cumulative photon–response relationship obtained by re-plotting the EPSC in A. C, the cumulative photon–response relations (mean ± s.e.m.) from eight ganglion cells obtained in the absence or the presence of bright surround light stimulation (‘centre only’ and ‘centre + bright surround’, respectively). Bright surround illumination shifted the curve to the right and compressed it (L50, P = 0.01; max, P < 0.01; n = 8). D, in the presence of carbenoxolone, the cumulative photon–response relation was compressed (L50, P = 0.16; max, P < 0.01; n = 8), while surround inhibition was eliminated (L50, P = 0.11 versus‘centre only’; max, P = 0.12 versus‘centre only’; n = 8).

The centre and surround stimuli were both in the photopic range and most probably activated cone-driven pathways. The light intensities employed in our study were comparable to those used by Yang & Wu (1997) to activate cone-dominant, salamander bipolar cells (see Results). We eliminated a rod contribution to the ganglion cell light-evoked responses by using dim light for dissection. When we used IR light for dissection, the threshold intensity to evoke minimum EPSCs in ganglion cells was always dimmer than −10 log units (n = 10). By contrast, the threshold intensity was −4.38 ± 0.18 log units for ganglion cells in slices dissected under dim light (n = 8) and the response latency was shorter, consistent with the observation by Hensley et al. (1993) that the dim illumination during isolation of the retina adapted the rod system. These observations strongly suggest that both centre and surround light responses were dominated by cone inputs.

To ensure that surround illumination was not scattering into the centre and desensitizing responses to centre illumination, we only analysed cells in which dim surround illumination alone did not elicit an EPSC. Brighter surround illumination often elicited small, transient EPSCs (≤ 13% of maximal centre response), which decayed completely before the receptive-field centre was activated. Increasing EPSC amplitudes in response to brighter centre illumination indicated that bright surround illumination did not saturate the centre response. Although bright surround light, which scattered into the centre, may have partially desensitized centre pathways, we still were able to determine the effects of antagonists on dim and bright surrounds signalling, as described below.

Analysis

For the conventional light-step stimulus experiments, peak ON -EPSC amplitude was measured by using Tack software (White Perch Software). Data were normalized to maximum response of the centre-evoked EPSC in control solution. SigmaPlot (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) curve-fitting routines were used to fit light intensity–response curves to the Hill equation:

where a is the maximum response, b is the slope factor, and L50 is the light intensity at half-maximum response. The luminance evoking a half-maximal response (L50) and the maximal response were determined from the fit. A Student's paired t test was used to determine whether or not each parameter was significantly different between two conditions in a group of cells. In the text, values are presented as means ± s.e.m., and differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

For the ramp light-stimulus experiments, we calculated cumulative photons at a given time of the ramp by integrating photons per unit area over the time course of the ramp light stimulus. The light-evoked EPSC was re-plotted as a function of cumulative photons μm−2 (see Fig. 6B) to obtain the intensity–response relation. Response amplitude and cumulative photons were normalized to maximum amplitude and to the photon number that evoked half-maximum response, respectively.

Results

The receptive-field surround reduces ganglion cell sensitivity to centre illumination

To determine the presynaptic effects of steady surround illumination, we measured the amplitudes of EPSCs evoked by illumination of the receptive-field centre (L-EPSCs) in the absence or presence of surround illumination. While previous studies have assessed salamander ganglion cell responses by using extracellular and intracellular voltage recordings (Thibos & Werblin, 1978; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a), we assessed their excitatory inputs directly by voltage clamping the ganglion cell to the reversal potential for the major inhibitory synaptic inputs (ECl). By measuring the L-EPSCs at ECl, we confined our analysis to the two lateral signalling pathways that were presynaptic to the ganglion cell dendrites. All recordings were obtained from ganglion cells that responded at light onset and offset (ON-OFF), the most frequently encountered subtype in the salamander slice preparation (Mittman et al. 1990). A single morphological class of ON-OFF ganglion cell was recorded from, which had dendritic processes that stratified in the mid-IPL, where cone-dominant bipolar cell inputs co-stratify (Wu et al. 2000). Because EPSCs at light offset (OFF L-EPSCs) showed significant variability in amplitude, we limited our analysis to the ON L-EPSCs. Steady surround illumination has similar effects on sustained and transient ON responses in salamander retina (Thibos & Werblin, 1978). Strychnine was included in the bath to block the change-sensitive surround inhibitory inputs (Cook et al. 1998) and it had no effect on steady surround ganglion cell responses (Cook et al. 1998; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a).

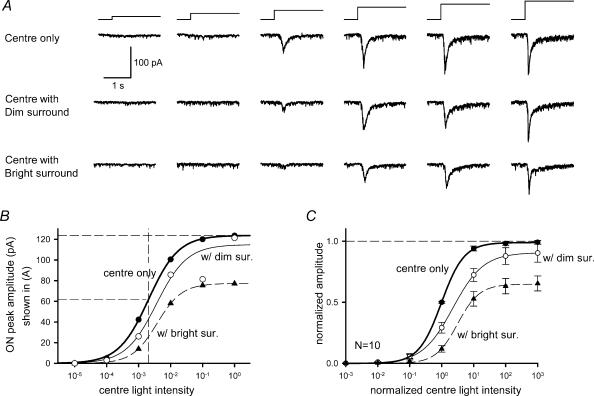

Illumination of the ganglion cell receptive-field centre elicited EPSCs that increased in amplitude with increasing light intensity (Fig. 1A, upper row). The L-EPSC was maximal at 0 log relative attenuation. In a few cells, at 0 log relative attenuation, the L-EPSC was reduced in amplitude, most probably attributable to scattered light stimulating the surround, which reduces the centre response amplitude (Cook & McReynolds, 1998a). The L-EPSC amplitudes were plotted as a function of light intensity in Fig. 1B (•).

Figure 1. Surround illumination reduced ganglion cell EPSCs evoked by receptive-field centre illumination.

A, EPSCs evoked by centre illumination (L-EPSCs) of increasing intensity (10−5–10° relative intensity, from left to right) in a ganglion cell voltage-clamped at −58.7 mV (ECl) (upper traces). Dim surround illumination (10−3 relative intensity) attenuated the L-EPSCs (middle traces). Bright surround illumination (10−1 relative intensity) reduced L-EPSCs further (lower traces). The time course and relative intensity of centre illumination is indicated by the stimulus traces above the light responses here and in subsequent figures. B, the peak amplitude of L-EPSCs (•), or with dim surround (○), or with bright surround (▴) in A was plotted as a function of centre light intensity. Each light intensity–response curve was fitted by the Hill equation (see Methods). The dashed horizontal lines indicate maximum amplitude (top) and half-maximum amplitude (middle) of L-EPSCs. The dashed vertical line indicates the light intensity at half-maximum of the centre-evoked EPSCs (L50). C, in this, and all of the succeeding intensity–response curves, the control centre illumination intensity–response curves were normalized to both the maximum amplitude of L-EPSCs, and to the light intensity at half-maximum amplitude of L-EPSCs. Curves measured in the presence of surround illumination were shifted relative to the control curve. The average maximum amplitude and L50 for the centre light were 0.99 ± 0.02 and 1.00 ± 0.0, respectively (n = 10). Dim surround illumination shifted the L50 to higher intensities (P < 0.01, n = 5), but did not significantly reduce the maximum amplitude (P = 0.19). Bright surround illumination shifted L50 values further (P < 0.01, n = 7) and reduced the maximum amplitudes (P < 0.01).

Surround illumination with an annulus (i.d., 300 μm; o.d., 2300 μm) reduced the current response of the ganglion cell to illumination of its receptive-field centre. Figure 1A (middle row) shows that surround illumination reduced the amplitude of the L-EPSCs, and shifted the intensity–response function to the right (Fig. 1B, ○). Increasing the surround illumination further reduced the L-EPSCs (Fig. 1A, lower row), increased the shift of the intensity–response function and suppressed the maximal response (Fig. 1B, ▴). While the suppressive effect on the maximal response by bright surround illumination has also been reported by others (Thibos & Werblin, 1978), the circuitry underlying this effect is unknown.

Figure 1C shows mean spot intensity–response curves obtained from 10 ganglion cells with centre or centre plus surround illumination. Maximal L-EPSC amplitude and light sensitivity (L50, the luminance eliciting a half-maximal response) varied from ganglion cell to ganglion cell, making comparisons across the population difficult. The L50 values varied from 3.7 × 10−4 to 1.2 × 10−2, with a mean value of 6.5 × 10−3 relative attenuation, which, after conversion to photon fluxes, were comparable to L50 values reported by Yang & Wu (1997) for salamander, cone-driven bipolar cells. To more easily compare intensity–response functions across different neurones, intensity–response curves were normalized to the maximal L-EPSC amplitude and the half-maximal light intensity of the spot function (Fig. 1C). Dim surround light shifted the control curve to the right, but there was no significant decrease in maximum L-EPSC amplitude (Fig. 1C; Table 1). Brighter surround light produced a further shifting of the curve to the right and also reduced the maximum L-EPSC amplitude of the average response (Fig. 1C; Table 1). These results are consistent with earlier extracellular- and intracellular-recording studies of mammalian and salamander ganglion cells (Sakmann & Creutzfeldt, 1969; Thibos & Werblin, 1978; Cook & McReynolds, 1998b).

Table 1.

Effect of GABA receptor blockers on light-sensitivity curves

| Light stimulation | Solution | Max | L50 mean | L50 range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre only | Control | 0.99 ± 0.02 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Centre + Dim sur. | Control | 0.91 ± 0.1 | 2.24* | 1.33–2.87 | 5 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | Control | 0.67 ± 0.1* | 3.17* | 1.64–14.7 | 7 |

| Centre only | Control | 0.99 ± 0.02 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Centre only | Bicuculline | 0.81 ± 0.08* | 2.22* | 1.28–8.23 | 8 |

| Centre only | Bic, I4AA, PTX | 1.03 ± 0.09 | 1.35 | 0.10–5.70 | 10 |

| Centre only | Bicuculline | 1.00 ± 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Centre + Dim sur. | Bicuculline | 0.85 ± 0.05* | 2.18* | 1.20–3.95 | 4 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | Bicuculline | 0.63 ± 0.1* | 3.31* | 2.05–10.2 | 6 |

| Centre only | Bic, I4AA, PTX | 1.00 ± 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Centre + Dim sur. | Bic, I4AA, PTX | 0.98 ± 0.4 | 0.88 | 0.08–2.14 | 5 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | Bic, I4AA, PTX | 0.53 ± 0.6* | 4.29* | 2.07–13.3 | 7 |

| Centre only | CGP55845 | 1.01 ± 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | CGP55845 | 0.40 ± 0.1* | 2.45* | 1.19–6.15 | 5 |

| Centre only | GABAA,B,C blockers | 0.99 ± 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | GABAA,B,C blockers | 0.49 ± 0.1* | 18.9* | 2.41–54.9 | 5 |

Max, normalized maximum amplitude, L50, normalized light intensity at half maximum, sur, surround, Bic, bicuculline.

Statistical significance versus‘centre only’, P < 0.05.

Surround responses in ganglion cells have been attributed to lateral, horizontal cell signalling in the OPL (Thibos & Werblin, 1978). However, recent studies have demonstrated that lateral inhibition, mediated by GABAergic amacrine cells, contributes to the ganglion surround response (Cook & McReynolds, 1998a; Flores-Herr et al. 2001). A portion of this lateral inhibition has been attributed to amacrine cell input to bipolar cell axon terminals. Consistent with this notion, it was shown previously that ganglion cell L-EPSCs evoked by full-field illumination were enhanced when GABAC receptor activation was reduced and diminished when GABAC receptor activation was increased (Zhang & Slaughter, 1995; Ichinose & Lukasiewicz, 2002). Although GABA receptors are present in the outer retina, GABA receptor blockers do not reduce outer retinal inhibitory signalling (Hare & Owen, 1996; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a; Kamermans et al. 2001; Verweij et al. 2003). Using GABA receptor blockers, we determined whether the components of the ganglion cell surround elicited by dim or bright surround illumination were mediated by GABAergic amacrine cells.

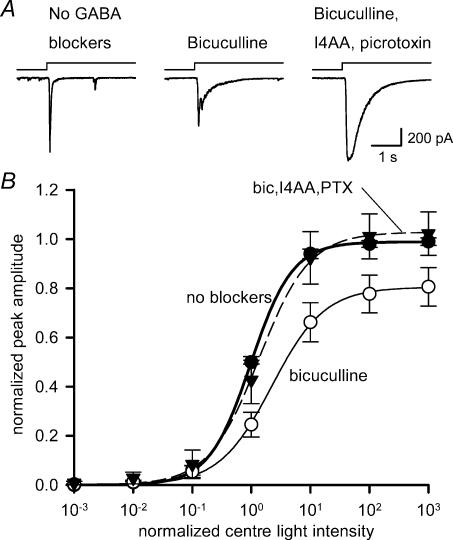

GABA receptor antagonists alter ganglion cell EPSCs evoked by centre illumination

The receptive-field centre illumination evokes both the excitation and the surround inhibition in ganglion cells because the steady surround component extends through the centre component of the receptive field (Rodieck & Stone, 1965; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a). In the inner retina, there are amacrine cells with both narrow- and wide-field processes. The relative contributions of these two morphological classes of amacrine cells, and the types of inhibitory receptors that they use to signal, are unclear. To assess the effects of GABA antagonists on the inhibition activated by centre stimuli and attributed to amacrine cells, we first determined the effects of GABA receptor blockers on EPSCs evoked by centre illumination alone. L-EPSCs evoked by sub-saturating centre illumination and recorded in the absence or presence of GABA receptor antagonists are shown in Fig. 2A. The blockade of GABAA receptors by bicuculline reduced the amplitude of the L-EPSC, but prolonged the response. Blocking GABAC and GABAA receptors, by the subsequent addition of I4AA and picrotoxin, increased the amplitude and prolonged the L-EPSCs beyond both control conditions and in the presence of bicuculline.

Figure 2. Effects of GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists on EPSCs evoked by centre illumination.

A, the amplitude of a ganglion cell EPSC evoked by centre illumination (left) was reduced by the GABAA receptor blocker bicuculline (200 μm) (middle). The suppressive effects of bicuculline were reversed by the addition of GABAC blockers, 200 μm picrotoxin and 20 μm I4AA (right). B, intensity–response curves for the centre-evoked EPSCs in the absence (•) or presence of GABA receptor blockers. Bicuculline (○) shifted the curve to the right (P < 0.05; n = 8) and reduced the maximum amplitude (P < 0.05). GABAC receptor blockers (▾) reversed the effects of bicuculline and shifted the light–response curve back to control levels (L50, P = 0.07; max, P = 0.35; n = 10).

Figure 2B shows intensity–response relationships for L-EPSCs obtained for centre illumination alone when GABA receptors were blocked. When GABAA receptors were antagonized by bicuculline, the curve was shifted rightwards to higher light intensities, and the maximum L-EPSC amplitude was reduced (Table 1). The effect of bicuculline can be attributed, in part, to blockade of serial inhibitory pathways, which resulted in increased GABAC receptor-mediated surround inhibition of bipolar cells (Zhang et al. 1997; Roska et al. 1998; Ichinose & Lukasiewicz, 2002). However, the prolongation of the L-EPSC by bicuculline as shown in Fig. 2A suggests that GABAA receptors may also modulate bipolar cell output, albeit to a lesser extent than GABAC receptors (Fig. 2A). When GABAC receptors were subsequently blocked by the addition of I4AA and picrotoxin, the bicuculline-induced curve shift was reversed (Table 1), indicating that it was mediated by GABAC receptor activation. In the presence of GABAC receptor blockers, the maximum L-EPSC amplitude was not significantly different from the control amplitude. However, as observed with bicuculline, the duration of the L-EPSCs were prolonged after GABAC receptors were blocked. This prolongation was previously described and has been attributed to the block of GABAC receptor-mediated inhibition to bipolar cell axon terminals, which truncates the excitatory signal to ganglion cells (Dong & Werblin, 1998; Shen & Slaughter, 2001). Because the GABAC receptor antagonist TPMPA was not sufficiently potent and selective in our hands, we were unable to effectively block GABAC receptors, despite the fact that Shen & Slaughter (2001) were able to. Nevertheless, the actions of GABAC receptor blockers picrotoxin and I4AA, applied in the presence of bicuculline, indicated that a component of the surround signal activated by centre illumination was mediated in the IPL by GABAC receptors on bipolar cell axon terminals.

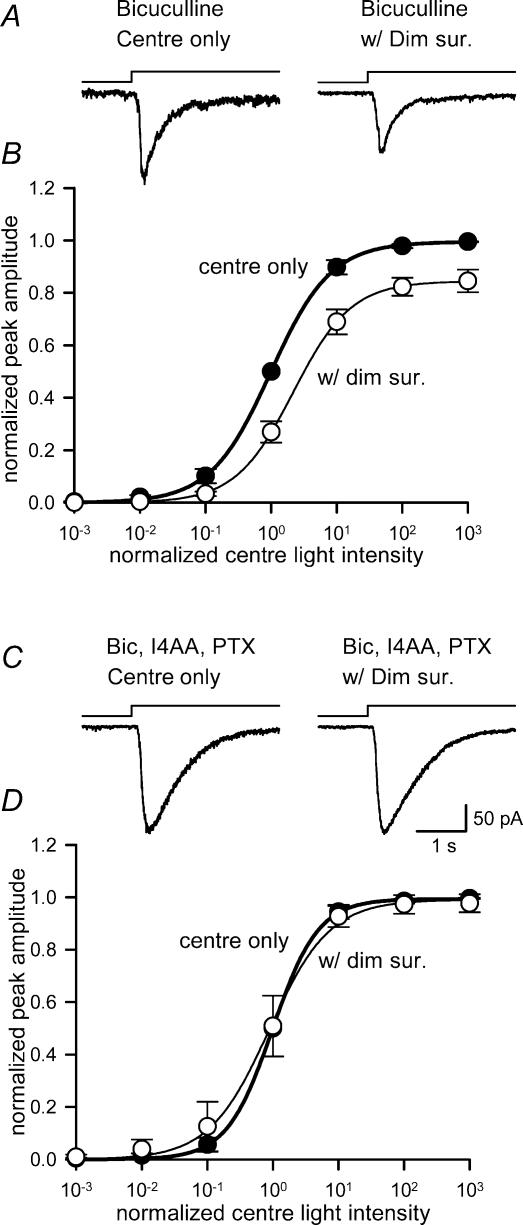

GABAC receptor antagonists reduced the dim surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs

As centre light-evoked EPSCs in ganglion cells were affected by a component of the surround, we assessed the effects of annular illumination on the GABAergic surround by comparing EPSCs elicited by centre and dim surround illumination with EPSCs in response to centre illumination alone. This allowed us to detect the direct actions of GABA receptor antagonists on wider-field surround signalling and control for any antagonist effects on central pathway signalling. When the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline was present, dim surround illumination still reduced the L-EPSCs (Fig. 3A). In the presence of bicuculline, dim surround shifted the intensity–response curve to brighter intensities and reduced the maximum amplitude of the L-EPSCs (Fig. 3B, Table 1). The inability of bicuculline to block the effects of dim surround illumination indicated that GABAA receptors did not mediate the predominant lateral inhibitory signals. The subsequent addition of the GABAC receptor antagonists, I4AA and picrotoxin to the bath blocked the effects of dim surround illumination, indicating that GABAC receptors mediated its effects (Fig. 3C and D, and Table 1). These data suggest that GABAC receptors, located primarily on bipolar cell terminals, mediate a large component of the lateral inhibitory signal elicited by dim surround illumination. Because GABAA receptors are present on salamander bipolar cell terminals, albeit to a lesser extent than GABAC receptors (Lukasiewicz et al. 1994), they may make a small contribution to surround signalling.

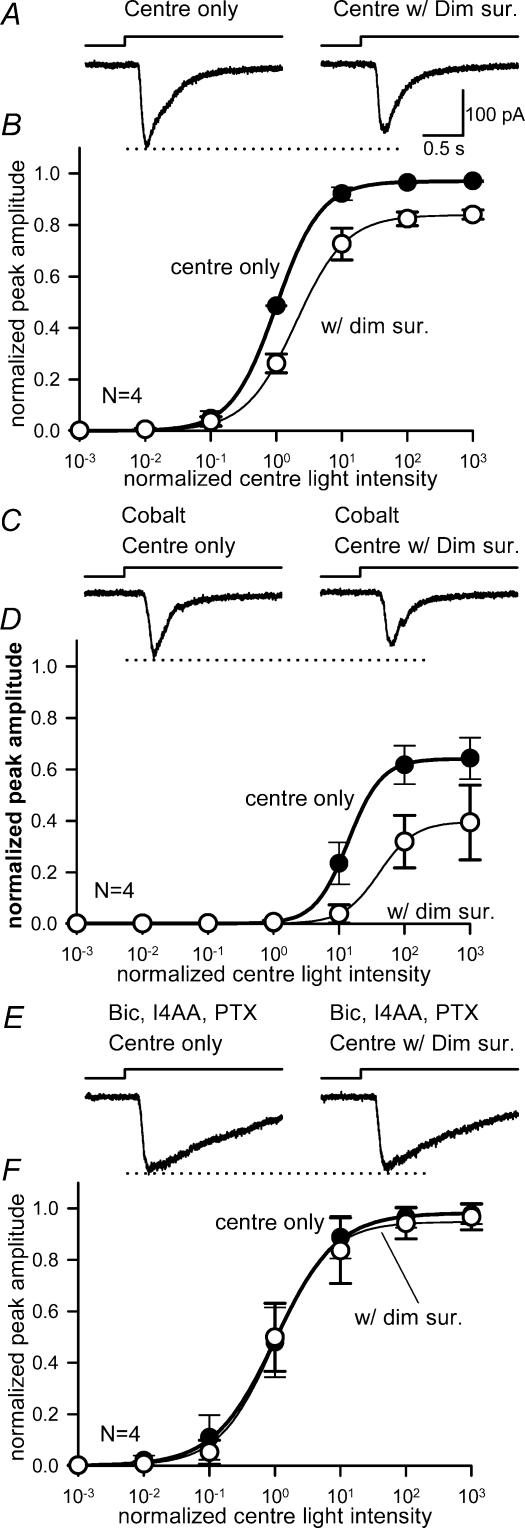

Figure 3. GABAC receptor antagonists blocked the reduction in ganglion cell light sensitivity by dim surround illumination.

A, a ganglion cell L-EPSC in the presence of bicuculline (left), was reduced by dim surround illumination (right). B, in the presence of bicuculline, the intensity–response curves for centre illumination (•) were still shifted to the right by the dim surround (○), indicating that bicuculline did not reverse the inhibition attributed to dim surround illumination (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.05; n = 4). C, L-EPSCs recorded in the presence of bicuculline and the GABAC receptor antagonists, I4AA and picrotoxin (left), were unaffected by dim surround illumination (right). D, in the presence of GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists, the intensity–response curves for centre plus surround (○) were similar to those for centre illumination alone (•) (L50, P = 0.40; max, P = 0.22; n = 5).

GABA receptor antagonists did not reduce the bright surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs

Activation of the receptive-field surround with brighter annular illumination produced a further reduction of the L-EPSC amplitude and caused an additional shift of the spot intensity–response curve to higher intensities, as well as reducing the maximum amplitude (Fig. 1, and Table 1). Although GABA receptor blockers were effective in blocking the effects of dim surround illumination, they had little effect on bright surround inhibition. Figure 4 shows L-EPSCs in either the absence or presence of bright surround illumination in the presence of antagonists. Neither bicuculline alone (Fig. 4A and B) nor bicuculline in combination with GABAC receptor blockers (Fig. 4C and D, and Table 1) reversed the effects of bright surround inhibition. These data suggest that different lateral inhibitory pathways mediated the effects of dim and bright surround illumination observed in ganglion cells.

Figure 4. GABAA or GABAC receptor antagonists did not block the effects of bright surround illumination.

A, L-EPSCs measured in the presence of bicuculline (left) were still strongly suppressed by bright surround illumination (right). B, in the presence of bicuculline, the intensity–response curves for centre illumination (•) were still shifted by bright surround illumination (▴), indicating that bicuculline did not block the inhibition evoked by bright surround illumination (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.01; n = 6). C, L-EPSCs measured after the GABAC receptor blockers, I4AA and picrotoxin, were applied with bicuculline were still reduced by bright surround illumination. D, in the presence of GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists, the centre intensity–response curve (•) was still shifted to the right and compressed by bright surrounds (▴) (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.01; n = 7), indicating that these receptors did not mediate the effects of bright surround illumination.

Results obtained in whole mount preparations were similar to those obtained in slices

To ensure that our results were not attributed to truncated lateral signal pathways, which may exist in the slice preparation, we repeated these experiments, and obtained the same results (data not shown), in the more intact retinal whole mount preparation. The same combination of GABAA and GABAC blockers that were used in the slice experiments, eliminated dim to moderate surround inhibition (n = 3), but did not affect the inhibition mediated by bright surround illumination (n = 5).

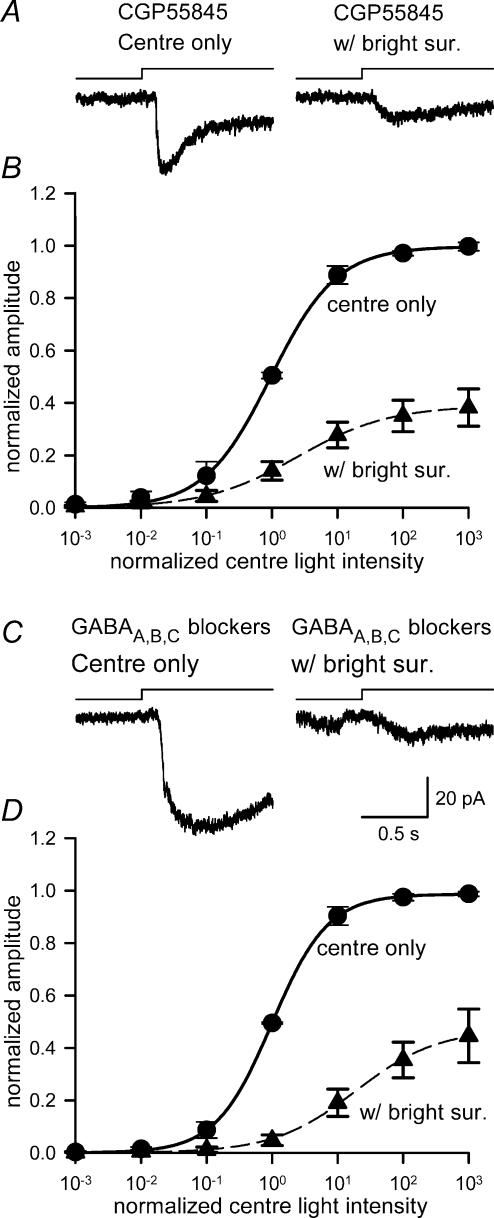

Bright surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs was not mediated by GABAB receptors

Although ionotropic GABA receptors did not mediate the bright surround response, it is possible that inhibition by bright surround illumination was mediated through GABAB receptors located in the IPL. GABAB receptors were shown to mediate presynaptic inhibition at bipolar cells (Maguire et al. 1989), which reduced light-evoked ganglion cell EPSCs (Shen & Slaughter, 2001). We tested whether GABAB receptors were involved in the suppression of L-EPSCs mediated by bright surround illumination by comparing the effects of centre and centre plus surround illumination in the presence of a GABAB receptor antagonist. Bath application of CGP55845 (100 μm) did not reverse the effects of bright surround illumination (Fig. 5A and B, and Table 1), indicating that GABAB receptors did not play a role in mediating this lateral inhibition. Even when the GABAB blocker was applied in combination with bicuculline, picrotoxin and I4AA (Fig. 5C and D, and Table 1), bright surround illumination was still effective, indicating that neither ionotropic nor metabotropic GABA receptors mediated bright surround inhibition. Instead of reversing the suppression attributed to bright surround inhibition, GABAB receptor blockers enhanced the surround suppressive effects (Table 1). This effect, while interesting, was beyond the scope of the present study and not investigated further.

Figure 5. Bright surround inhibition was not mediated by GABAB receptors.

A, L-EPSCs measured in the presence of the GABAB receptor antagonist, CGP55845 (left) were still attenuated by bright surround illumination (right). B, the centre intensity–response curve (•) was still shifted to the right and compressed by bright surround light (▴) (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.01; n = 5). C, the L-EPSC (left) measured in the presence of bicuculline, CGP55845, I4AA and picrotoxin was still attenuated by bright surround illumination (right). D, the centre light, intensity–response curve (•) was compressed and shifted to right with bright surround light (▴) (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.01; n = 5).

Carbenoxolone blocked bright surround inhibition without affecting dim surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs

Although GABA receptors are present in the OPL, steady surround inhibition in the outer retina is not mediated by GABA receptors on cones or bipolar cells (Hare & Owen, 1996; Verweij et al. 1996, 2003; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a; McMahon et al. 2004), but has been attributed to the modulation of calcium channels on cone photoreceptor terminals by horizontal cells (Verweij et al. 1996; Kamermans et al. 2001). Horizontal cell feedback to cones was blocked by carbenoxolone or cobalt and was not reduced by GABA receptor blockers (Verweij et al. 1996, 2003; Kamermans et al. 2001; Fahrenfort et al. 2004).

We tested whether signalling from horizontal cells to cone photoreceptors mediated the bright surround inhibition observed in ganglion cells by recording responses in the absence or presence of carbenoxolone. As carbenoxolone also caused a time-dependent suppression of the cone output (Kamermans et al. 2001; Vessey et al. 2004), we obtained complete light intensity–response functions rapidly by ramping the light intensity in a staircase fashion with increments of 0.5 or 1.0 log intensity steps with durations of 100–150 ms (Fig. 6A). The blocking effects of carbenoxolone on horizontal cell feedback are best observed when central cones were maximally activated by light (Kamermans et al. 2002; Verweij et al. 2003). We used a modified version of this protocol where we partially activated the receptive-field centre with dim illumination and then measured the effects of further increases of centre illumination, in either the absence or presence of bright surround illumination (Fig. 6A).

In response to a ramp of light intensity, we recorded a slowly rising ganglion cell L-EPSC whose amplitude increased as a function of centre illumination intensity (Fig. 6A). GABAA, GABAC and glycine receptor antagonists were included in the bath to block lateral inhibition at the IPL. Intensity–response relationships were constructed by re-plotting the L-EPSCs as a function of cumulative photons μm−2 (Fig. 6B, see Methods). In the presence of bright surround illumination, the centre intensity–response relationship was shifted to brighter intensities and the maximum amplitude was reduced (Fig. 6C). These ramp-generated intensity–response relationships were similar to the intensity–response relationship generated by increasing centre-illumination steps illustrated above (Fig. 4D, and Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Effects of carbenoxolone, cobalt and NO-711 on light-sensitivity curves

| Light stimulation | Solution | Max | L50 mean | L50 range | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre only | Control (GABAA,C blockers) | 0.95 ± 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | Control (GABAA,C blockers) | 0.39 ± 0.05* | 2.61* | 1.61–13.7 | 8 |

| Centre only | + Carbenoxolone | 0.55 ± 0.1 | 0.88 | 0.51–7.24 | 8 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | + Carbenoxolone | 0.48 ± 0.1 | 1.23 | 0.93–19.2 | 8 |

| Centre only | Control (GABAA,C blockers) | 0.99 ± 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | Control (GABAA,C blockers) | 0.32 ± 0.05* | 7.56* | 2.62–21.1 | 5 |

| Centre only | + 10 μm cobalt | 0.58 ± 0.1 | 13.1 | 1.12–39.7 | 5 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | + 10 μm cobalt | 0.54 ± 0.1 | 24.5 | 0.99–175 | 5 |

| Centre only | Control | 0.97 ± 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Centre + Dim sur. | Control | 0.84 ± 0.0* | 1.98* | 1.41–3.00 | 4 |

| Centre only | 10 μm cobalt | 0.64 ± 0.1 | 13.8 | 9.19–34.8 | 4 |

| Centre + Dim sur. | 10 μm cobalt | 0.41 ± 0.2* | 40.9* | 21.1–57.8 | 4 |

| Centre only | Bic, I4AA, PTX | 0.98 ± 0.0 | 1.01 | 0.22–4.05 | 4 |

| Centre + Dim sur. | Bic, I4AA, PTX | 0.97 ± 0.0 | 0.98 | 0.57–9.90 | 4 |

| Centre only | Control | 1.00 ± 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | Control | 0.48 ± 0.1* | 3.62* | 2.90–15.1 | 3 |

| Centre only | NO-711 | 0.57 ± 0.1 | 33.2 | 1.66–73.8 | 3 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | NO-711 | 0.31 ± 0.1* | 364* | 22.5–989 | 3 |

| Centre only | + Bic, I4AA, PTX | 1.48 ± 0.6 | 28.9 | 0.40–55.6 | 3 |

| Centre + Bright sur. | + Bic, I4AA, PTX | 0.40 ± 0.1* | 369* | 15.9–950 | 3 |

Max, normalized maximum amplitude, L50, normalized light intensity at half maximum, sur, surround, Bic, bicuculline.

Statistical significance versus‘centre only’, P < 0.05.

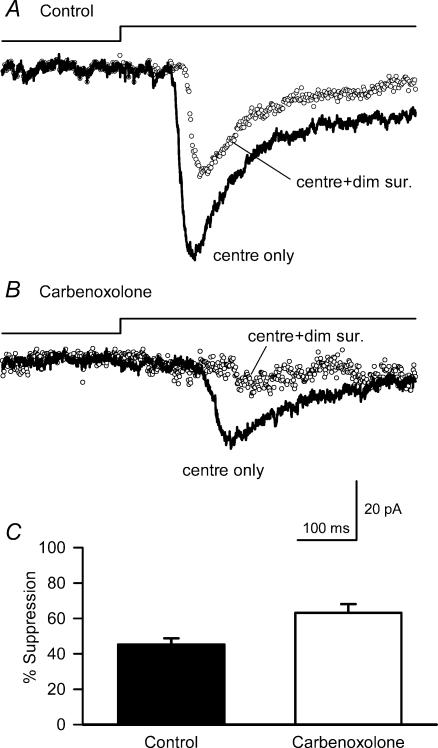

Carbenoxolone blocked the inhibitory effects of bright surround on L-EPSCs (Fig. 6D, and Table 2). In addition, carbenoxolone gradually reduced the L-EPSCs over a few minutes (Fig. 6D, ‘centre only’), as reported previously (Kamermans et al. 2001; Verweij et al. 2003). In the presence of carbenoxolone, the intensity–response relationships for centre illumination alone overlapped with those obtained for centre plus surround illumination (maximum response (max), P = 0.12; L50, P = 0.11). The elimination of bright surround inhibition is consistent with earlier reports of carbenoxolone blocking horizontal cell signalling to cones (Kamermans et al. 2001; Verweij et al. 2003; McMahon et al. 2004).

Although bright surround signalling was blocked by carbenoxolone, the effects of dim surround illumination on the responses to centre illumination were not affected by carbenoxolone. To observe the effects of dim surround illumination mediated by inner retinal pathways, GABA receptor antagonists were not present in the bath. Because we could not obtain reliable responses to ramp-intensity stimuli, in the absence of GABA receptor blockers, we used steps of sub-saturating centre illumination to assess the effects of surround inhibition. As noted above, L-EPSC run-down precluded us from obtaining intensity–response relationships using steps of illumination. Dim surround illumination reduced the response to centre illumination steps in either the absence (Fig. 7A) or presence (Fig. 7B) of carbenoxolone. As expected, carbenoxolone also reduced the effects of centre illumination, but was ineffective in reducing the effects of dim surround illumination (Fig. 7B and C). The results with carbenoxolone suggest that the pathways that mediate dim and bright surround inhibition are distinct.

Figure 7. Carbenoxolone did not affect dim surround inhibition.

A, L-EPSCs in the presence of strychnine, but in the absence of GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists (thick line), was suppressed by 43% by dim surround illumination (○). B, the L-EPSC was still suppressed (by 43%) by dim surround illumination when carbenoxolone (100 μm) was present, although it reduced the EPSC evoked by the centre illumination (see text). C, bar graph summarizing the dim surround illumination results. The suppression of L-EPSCs by dim surround illumination (45.3 ± 3.5%, filled bar) was not reduced by carbenoxolone (63.2 ± 5.0%, n = 7, open bar).

Cobalt reduced bright surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs

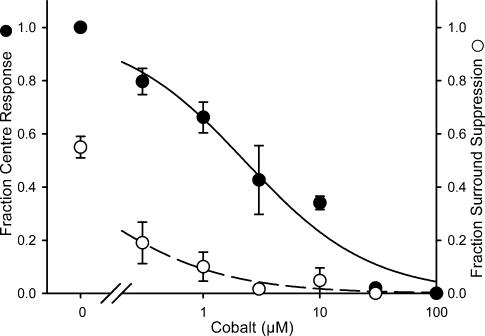

While our findings with carbenoxolone are consistent with its blockade of horizontal cell signalling to cones, carbenoxolone has also been reported to reduce calcium currents in cones (Vessey et al. 2004). The latter effect could explain the time-dependent decrease in cone output that we observed, but it is unclear whether this effect contributed to the blockade of surround signals that we observed (Kamermans & Fahrenfort, 2004). Therefore we used another method to reduce horizontal cell signalling to cones. Low concentrations of cobalt, which do not eliminate synaptic transmission, have been shown to block horizontal cell feedback to cones in turtle (Thoreson & Burkhardt, 1990; Vigh & Witkovsky, 1999) and macaque retina (Verweij et al. 2003). In goldfish retina, this cobalt blockade has been attributed to block of hemichannels on horizontal cells (Fahrenfort et al. 2004). As cobalt blocks surround antagonism in ganglion cells at photopic light levels (Vigh & Witkovsky, 1999; McMahon et al. 2004), we tested whether low concentrations of cobalt blocked bright surround inhibition in our preparation.

Because cobalt can also reduce synaptic transmission, we first determined the optimal concentration of cobalt needed to block surround inhibition with minimal effects on transmitter release. To do this, we measured the effects of cobalt on synaptic transmission by recording L-EPSCs and comparing these effects with the ability of cobalt to block bright surround inhibition. As with the carbenoxolone experiments, the centre pathway was partially activated with red illumination (−1 log attenuation). The cobalt concentration–response curve for the centre light response is shown in Fig. 8. The fraction of inhibition of the centre response by bright surround illumination is also plotted in Fig. 8. Complete surround inhibition of the centre responses is indicated by 1.0, and no inhibition is indicated by 0.0. At a concentration that preferentially reduced cone surround inhibition in goldfish and macaque retina, cobalt (50 μm) abolished the ganglion cell EPSCs evoked by centre illumination (n = 4). When 0.3 μm cobalt was used, some surround inhibition still remained. Bright surround inhibition was dramatically reduced by 3–10 μm cobalt, but the L-EPSCs were only decreased by half. Thus we determined whether 3–10 μm cobalt blocked the effect of bright surround illumination on light-sensitivity curves.

Figure 8. Low concentrations of cobalt attenuated the bright surround inhibition as well as EPSCs evoked by centre illumination.

L-EPSCs were recorded in the presence or absence of bright surround illumination. EPSCs evoked by centre light alone were attenuated by cobalt at 0.3 μm (•), and were abolished at 50 μm. The suppressive effect of bright surround inhibition was also blocked with cobalt at 0.3 μm (○), and was mostly eliminated at 3 μm. Each point shows the mean (± s.e.m.) of responses from different neurones (n = 2–3).

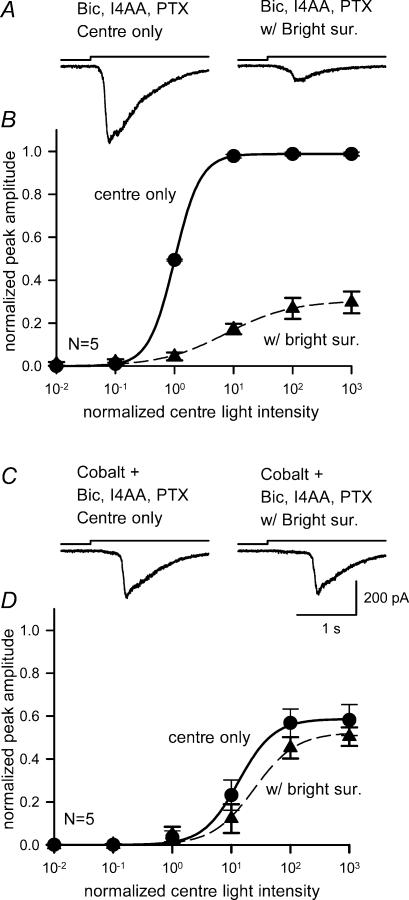

L-EPSCs were recorded in the absence or presence of bright surround illumination from five ganglion cells in the presence of bicuculline, I4AA and picrotoxin to block GABA signalling. Under these conditions, bright surround illumination still reduced the L-EPSCs (Fig. 9A) and shifted and compressed the intensity–response curve (Fig. 9B, and Table 2). In the presence of cobalt (3–10 μm), the L-EPSCs were reduced (Fig. 9C, left), and the light intensity–response curve shifted to the right (Fig. 9D, ‘centre only’). However, cobalt blocked the effects of bright surround illumination. In the presence of cobalt, bright surrounds did not reduce the L-EPSCs and did not shift the intensity–response curves (n = 5, Fig. 9C and D, and Table 2). These data are in agreement with earlier studies and suggest that cobalt blocked bright surround signalling by acting at the outer retina (Vigh & Witkovsky, 1999; Verweij et al. 2003; Fahrenfort et al. 2004; McMahon et al. 2004).

Figure 9. Cobalt blocked the reduction in ganglion cell light sensitivity by bright surround illumination.

A, L-EPSCs in the presence of bicuculline, I4AA and picrotoxin (left), were reduced by bright surround illumination (right). B, in the presence of GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists, the intensity–response curves for centre illumination (•) were still shifted to the right by the bright surround (▴) (L50, P < 0.01; max, P < 0.01; n = 5). C, L-EPSCs recorded in the presence of 3–10 μm cobalt as well as GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists (left) were unaffected by bright surround illumination (right). D, in the presence of 3–10 μm cobalt, as well as GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists, the intensity–response curve for centre plus surround illumination (▴) was similar to the curve for centre illumination alone (•) (L50, P = 0.14; max, P = 0.08; n = 5).

Cobalt did not affect dim surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs

We also tested whether cobalt (10 μm) affected dim surround inhibition, which we attributed to a GABA-dependent pathway in the IPL (Fig. 3). L-EPSCs were recorded in the absence or presence of dim surround illumination from four ganglion cells in control solution or in cobalt-containing solution. As shown above, dim surround illumination reduced the L-EPSCs (Fig. 10A), and shifted the light intensity–response curve to the right and compressed it slightly (Fig. 10B, and Table 2). Cobalt reduced the L-EPSCs (Fig. 10C) and shifted and compressed the spot intensity–response curves from their control values (Fig. 10D‘centre only’), as noted above. In contrast to its effects on bright surround, cobalt did not block the effects of dim surround illumination. In the presence of cobalt, dim surround illumination still reduced the L-EPSC amplitude (Fig. 10C right) and shifted the spot intensity–response curve (Fig. 10D, and Table 2). After washing out cobalt, we tested the effects of GABAA and GABAC receptor blockers on dim surround illumination in the same set of cells. As expected, the GABA receptor blockers eliminated the effect of dim surround illumination (Fig. 10E and F, and Table 2).

Figure 10. Cobalt did not block the effects of dim surround illumination.

A, ganglion cell EPSCs evoked by centre illumination (left), were reduced by dim surround illumination (right) in the control Ringer solution. B, the intensity–response curves for centre illumination (•) were shifted to the right and compressed by the dim surround illumination (○) (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.01; n = 4). C, 10 μm cobalt attenuated centre-evoked EPSCs (left). The EPSCs were still suppressed by dim surround illumination (right). D, in the presence of 10 μm cobalt, the intensity–response curves for centre illumination (•) were still shifted by dim surround illumination (○), indicating that cobalt did not affect the inhibition evoked by dim surround illumination (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.05; n = 4). E, after cobalt was washed out, L-EPSCs were recorded in the presence of GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists (left). Dim surround illumination did not attenuate the L-EPSCs (right). F, in the presence of GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists, the centre intensity–response curve (•) was similar to the curve for centre with dim surround illumination (○) (L50, P = 0.13; max, P = 0.37; n = 4), indicating that dim surround inhibition was mediated by GABA receptors, but not by cobalt-sensitive pathways.

Our results with cobalt were similar to our carbenoxolone findings and confirmed that the pathways that mediate dim and bright surround inhibition are distinct. The dim surround inhibition was GABA-dependent, suggesting that it was mediated in the IPL, whereas the bright surround inhibition was not GABA-dependent but carbenoxolone- and cobalt-sensitive, suggesting that it was mediated by the OPL.

Bright surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs was not mediated by a presynaptic, GABAergic pathway

The experiments with carbenoxolone and cobalt suggested that the bright surround inhibition is mediated by a different pathway from the dim surround signalling pathway. We examined whether the bright surround inhibition also uses a GABA-dependent pathway by determining whether GABA transporter (GAT) inhibition affected bright surround signalling (Ichinose & Lukasiewicz, 2002). The effect of GABA signalling on the surround inhibition is different at the inner and the outer retina. In the IPL, we showed that presynaptic surround inhibition was mediated by GABA signalling. When GABA signalling is enhanced in the IPL by GAT inhibitors, IPL surround inhibition is enhanced and this enhancement can be reversed with GABA receptor blockers (Ichinose & Lukasiewicz, 2002). In the OPL, GABA does not mediate surround signalling (Verweij et al. 1996, 2003), but it modulates surround inhibition (Kamermans et al. 2002). The horizontal cell feedback to cones is reduced by the activation of ionotropic GABA receptors and enhanced after GABA signalling is reduced by blocking either GABA release with GAT inhibitors or GABA receptors with antagonists (Kamermans et al. 2002).

To determine whether bright surround inhibition was also mediated by a GABA-dependent, presynaptic pathway, we examined the effects of a GAT inhibitor, NO-711, and GABAA and GABAC receptor blockers on the bright surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs. Figure 11A and B shows the L-EPSCs and light-sensitivity curves in the absence and presence of bright surround illumination. NO-711 reduced the L-EPSCs and shifted the centre intensity–response relation to the right (Fig. 11C and D, and Table 2) in agreement with our previous results (Ichinose & Lukasiewicz, 2002). The shift of the ‘centre only’ intensity–response curve by NO-711 can be attributed to the enhancement of the GABAergic inhibition in the IPL.

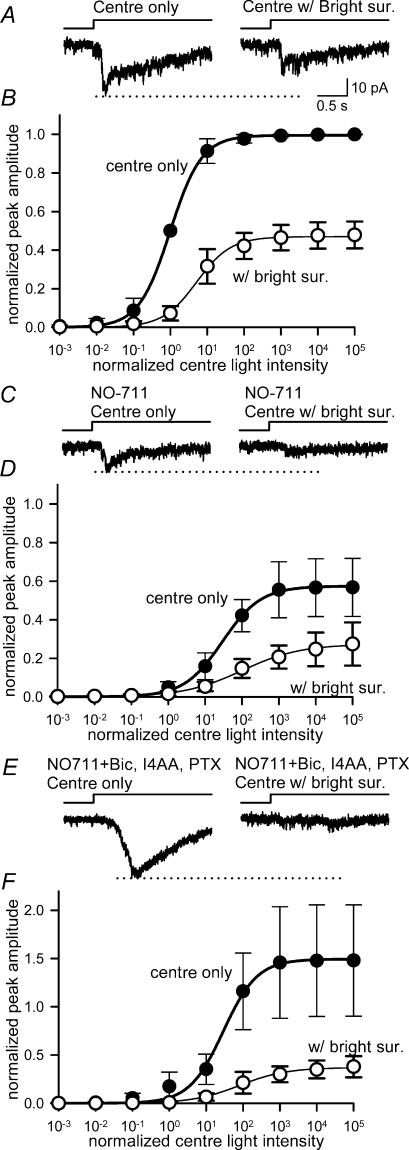

Figure 11. Bright surround inhibition did not utilize a presynaptic, IPL pathway.

A, L-EPSCs recorded in control solution (left), were attenuated by bright surround illumination (right). B, the centre intensity–response curve (•) was shifted to the right and compressed by bright surround light (○) (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.05; n = 3). C, NO-711 (3 μm) reduced L-EPSCs (left), which was further reduced by bright surround illumination (right). D, the intensity–response relationships of L-EPSCs in the presence of NO-711, with and without bright surround illumination. Bright surrounds still shifted the curve to the right (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.09; n = 3). E, subsequent application of ionotropic GABA receptor blockers, 200 μm bicuculline, 50 μm I4AA and 200 μm picrotoxin, reversed the effect of NO-711 on centre-evoked L-EPSCs (left), but did not reverse the NO-711 effect on bright surround illumination (right). F, the addition of GABA receptor blockers did not reverse the NO-711 effect on the bright surround-mediated shift of the intensity–response curve (L50, P < 0.05; max, P < 0.05; n = 3).

NO-711 enhanced surround inhibition elicited by bright annular stimulation (Fig. 11C and D, and Table 2). In the presence of NO-711, bright surrounds caused a larger reduction in maximum L-EPSC amplitude and a larger rightward shift of the L-EPSC intensity–response curve. The NO-711 effects on lateral inhibition can be attributed to two different mechanisms; surround inhibition was enhanced by increasing GABA signalling in the IPL or feedback to cones was enhanced by decreasing GABA modulation in the OPL, or both. If the GAT inhibitor effect was attributed to an IPL mechanism, then subsequent application of GABA receptor blockers should reverse the effect. By contrast, surround inhibition in the OPL should not be affected by the addition of GABA receptor blockers because the GAT inhibitor had already blocked GABA release from horizontal cells. When we added GABAA and GABAC receptor blockers in the bath solution, the effect of the GAT inhibitor on ‘centre only’ L-EPSCs was reversed (Fig. 12C and E), consistent with these effects occurring in the IPL. However, the bright surround inhibition, enhanced by NO-711, was not reversed by GABA receptor blockers (Fig. 12E and F, and Table 2), suggesting that it was primarily mediated in the OPL. These data suggest that the bright surround inhibition was not mediated by a presynaptic, GABA-dependent pathway in the IPL, and suggest that OPL signalling was enhanced by blocking GABAergic modulation of horizontal feedback to cones (Kamermans et al. 2002).

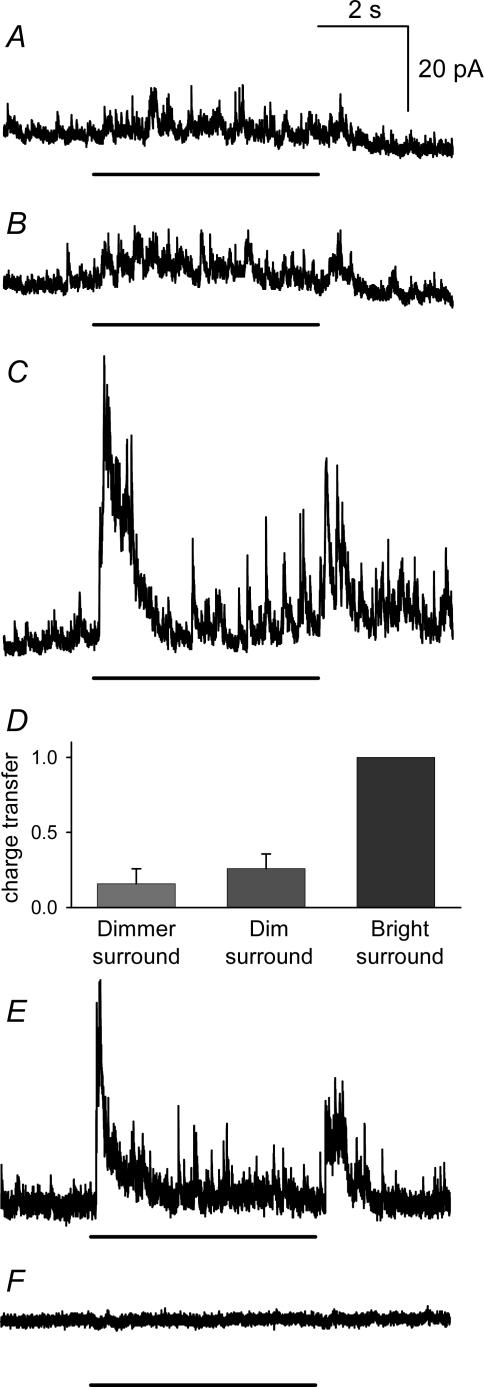

Figure 12. Direct inhibition from amacrine cells to ganglion cells was evoked by surround illumination.

A, dimmer surrounds, which did not attenuate L-EPSCs in ganglion cells, evoked small L-IPSCs. B, the standard dim surround stimulus, which did attenuate ganglion cell L-EPSCs, evoked slightly larger L-IPSCs. C, the standard bright surround stimulus elicited prominent L-IPSCs. D, graph shows L-IPSC charge transfer for the three surround intensities, normalized to the response to bright surround for each cell (n = 7). Dim surrounds evoked significantly smaller L-IPSCs than the L-IPSCs elicited by bright surround (0.26 ± 0.1, P < 0.01 versus bright surround) and were not different from the L-IPSCs evoked by dimmer surround illumination (0.16 ± 0.1, P < 0.01 versus bright surround, P = 0.46 versus dim surround). E, L-IPSCs evoked by bright surround illumination, recorded from a different cell. F, bicuculline (200 μm) abolished the L-IPSCs in E. The duration of the light stimulus is indicated by the line below each L-IPSC.

Bright surround inhibition of ganglion cell L-EPSCs also utilizes a direct inhibitory pathway

In addition to the presynaptic surround signalling pathways described above, there is also a GABAergic amacrine cell pathway that directly inhibits ganglion cells (Cook & McReynolds, 1998a). We assessed the contribution of this pathway by recording light-evoked inhibitory postsynaptic currents (L-IPSCs) in ganglion cells that were voltage-clamped to 0 mV, the reversal potential for L-EPSCs. Strychnine was included in the bath to isolate the GABAergic L-IPSCs. The standard dim surround stimulus used throughout this study evoked small amplitude, asynchronous L-IPSCs (Fig. 12B). Dimmer surround stimuli, which did not inhibit L-EPSCs in ganglion cells, evoked smaller L-IPSCs; however, they were not significantly different from those evoked by the standard dim surround (Fig. 12A and D). By contrast, standard bright surround stimuli evoked large L-IPSCs composed of synchronous and asynchronous events (Fig. 12C and D). Comparisons of the L-IPSC charge transfer evoked by different surround illumination intensities show that bright surround illumination was more effective than dim surround illumination in activating the feedforward IPL inhibitory surround pathway. These findings are in contrast to our results for presynaptic, IPL inhibition that showed that dim surround illumination was most effective in suppressing ganglion cell L-EPSCs. In agreement with previous studies (Dong & Werblin, 1998; Lukasiewicz & Shields, 1998; Flores-Herr et al. 2001), the L-IPSCs evoked by bright surround illumination were blocked by bicuculline (Fig. 12E and F), indicating that they were mediated by GABAA receptors. Our results illustrate that surround signalling in the IPL was mediated by two amacrine cell pathways. Dim surround signalling utilized a presynaptic pathway that reduced bipolar cell transmitter release and bright surround signalling utilized a pathway that directly inhibited ganglion cells.

Discussion

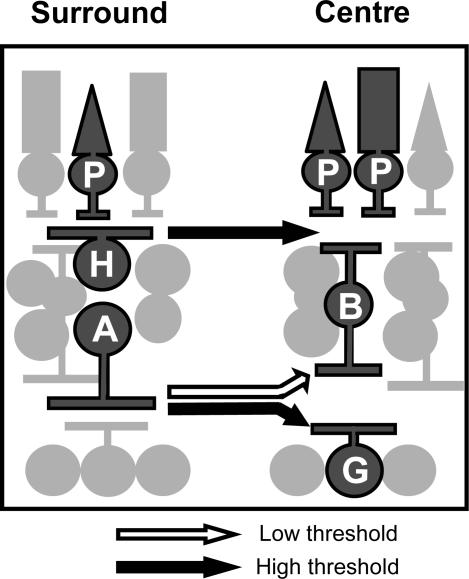

The reduction in ganglion cell light sensitivity in response to receptive-field surround activation was attributed to horizontal cell signalling in the OPL (Thibos & Werblin, 1978). Subsequent studies indicated that GABAergic amacrine cells also contribute to surround inhibition of ganglion cells in both salamander (Cook & McReynolds, 1998a; Roska et al. 2000) and rabbit (Flores-Herr et al. 2001). Here we show that lateral pathways in both the IPL and the OPL contribute to the ganglion cell surround, as suggested by Naka (1977). However, the contribution of each pathway depended on the intensity of surround illumination. The dim surround inhibition was mediated by a GABA-dependent pathway in the IPL that was presynaptic to ganglion cells, whereas the bright surround inhibition was mediated by a presynaptic, GABA-independent pathway in the OPL and direct GABAergic inhibition in the IPL (Fig. 13).

Figure 13. Different lateral pathways mediate bright or dim surround inhibition.

Presynaptic, dim surround inhibition was mediated by GABAC receptors, suggesting amacrine cell activation of bipolar cells in the IPL. By contrast, presynaptic, bright surround inhibition was mediated by a GABA-independent, carbenoxolone- and cobalt-sensitive mechanism, consistent with feedback from horizontal cells to cones in the OPL. Bright surround inhibition was also mediated in the IPL by amacrine cells, which directly inhibited ganglion cells. P, photoreceptor; B, bipolar cell; G, ganglion cell; H, horizontal cell; A, amacrine cell.

Inhibition evoked by dim surround illumination was primarily mediated in the IPL

Blockade of GABAC receptors located mainly on bipolar cell axon terminals (Lukasiewicz et al. 1994; Enz et al. 1996; Koulen et al. 1997) eliminated the dim surround component of ganglion cell responses (Fig. 13). Although GABA receptors are present on cone photoreceptors, as well as on bipolar cell dendrites, in mammals and in lower vertebrates (Vardi et al. 1992; Picaud et al. 1998; Wu & Maple, 1998; Shields et al. 2000), they do not mediate lateral inhibition in the outer retina in either lower vertebrates or primates as surround inhibition was still observed in bipolar cells and cone photoreceptors in the presence of GABA receptor antagonists (Hare & Owen, 1996; Verweij et al. 1996, 2003; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a). In agreement with our findings, GABA blockers eliminated mesopic surround inhibition to rabbit ganglion cells (Flores-Herr et al. 2001) and to rat bipolar cell terminals (Euler & Masland, 2000). These findings suggest that GABA blockers acted primarily at bipolar cell axon terminals to block presynaptic surround inhibition of ganglion cells.

Both wide- and narrow-field GABAergic amacrine cells are present in salamander retina (Yang et al. 1991; Deng et al. 2001). The contributions of these two classes of amacrine cells to the surround receptive-field organization are unclear. Our results show that inhibitory signals mediated by both narrow- and wide-field amacrine cell inputs had the same properties. Both spot and annulus stimuli activated GABAC receptor-mediated pathways (Figs 2 and 3) and blockade of GABAA receptors enhanced GABAC signalling in both cases. These findings suggest that either both narrow- and wide-field amacrine cells contribute to the ganglion cell surround or that wide-field amacrine cells can mediate both lateral and local signalling (Cook & McReynolds, 1998a).

Glycinergic amacrine cells in salamander also have wide-field processes (Yang et al. 1991) and mediate a change-sensitive, wide-field inhibition of ganglion cells (Cook et al. 1998). Studies in salamander, rabbit and primate retina showed that strychnine, which blocks transient inhibition (Belgum et al. 1984; Cook et al. 1998), had no effect on the sustained surround component of ganglion cells (Cook et al. 1996; Cook & McReynolds, 1998a; Flores-Herr et al. 2001; McMahon et al. 2004). These studies suggest that both glycinergic amacrine and interplexiform cells (Maple & Wu, 1998) do not contribute to steady surround inhibition. In our study, the effects of steady surround inhibition cannot be attributed to glycinergic neurones because we always included strychnine in the bath.

We found that carbenoxolone and cobalt, agents reported to block feedback to cones (Kamermans, 2001; Verweij et al. 2003; Fahrenfort et al. 2004), had little effect on dim surround inhibition, suggesting that dim surround illumination does not strongly activate lateral inhibitory pathways in the outer retina. Consistent with our findings, others showed that horizontal cell feedback to cones in goldfish and primate retinas is most effective when activated by bright illumination (Kraaij et al. 2000; McMahon et al. 2004). Although we cannot rule out a role of the outer retina in mediating a component of dim surround inhibition, under our experimental conditions it did not play a major role.

Dim surround effects were not mediated by rod photoreceptor pathways

Rod and cone signalling pathways have different light sensitivities; however, our observations cannot be attributed to the differential activation of these pathways by dim or bright surround illumination. We used red light in all of our experiments, which should only minimally activate salamander rods at dim light intensities (Fain & Dowling, 1973). We also performed our dissections using dim red light that eliminated the rod-mediated responses that were observed if dissections were performed using IR illumination (see Results, Hensley et al. 1993). All of the ON-OFF ganglion cells recorded had dendritic proccesses that stratified in the mid-IPL and received inputs from cone-dominant bipolar cells (Wu et al. 2000). Thus, the dim and bright surround signalling that we recorded were most probably mediated primarily by cone signalling pathways.

Presynaptic inhibition evoked by bright surround illumination was primarily in the OPL

Bright illumination of the receptive-field surround reduced the sensitivity of the ganglion cell to centre illumination further and also reduced the maximum L-EPSC amplitude. Thibos & Werblin (1978) reported similar effects on ganglion cell spike output. We found that the effects of bright surround illumination on the L-EPSCs, unlike dim illumination, were not reversed by GABA receptor antagonists, suggesting that they were not GABA-mediated. The effects of bright surround illumination were not mediated by glycine because strychnine was always present in the bath solution. Our inability to reduce the effects of bright surround illumination with GABA and glycine receptor antagonists suggests that the lateral inhibition was either mediated in the outer retina or by amacrine cells that release an inhibitory transmitter other than GABA or glycine.

Bright surround inhibition was reduced by carbenoxolone and cobalt, suggesting that it was largely mediated in the outer retina (Fig. 13). In support of this notion, bright surrounds were found to most effectively activate lateral feedback to cones in goldfish (Kraaij et al. 2000) and in primates (McMahon et al. 2004). Carbenoxolone and cobalt, which have been shown to block feedback inhibition to cone photoreceptors (Thoreson & Burkhardt, 1990; Kamermans et al. 2001; Verweij et al. 2003), blocked the effects of bright surround inhibition on ganglion cells. Consistent with our findings, McMahon et al. (2004) showed that photopic surround inhibition to primate parasol ganglion cells was reduced by carbenoxolone and by cobalt. Vessey et al. (2004) showed that carbenoxolone also reduces calcium currents in cones. This may have contributed to the time-dependent decrease of the centre response that we observed with carbenoxolone, but these actions cannot account for the effects of carbenoxolone on feedback to cones (Kamermans & Fahrenfort, 2004). In our experiments, carbenoxolone still reduced the effects of bright surrounds, consistent with the blockade of feedback. The simplest interpretation of our results is that these blockers reduced signalling from horizontal cells to cones, diminishing the effects of bright surround illumination. Carbenoxolone may have also reduced electrical coupling between horizontal cells, decreasing lateral signalling in the OPL. However, calculations by Verweij et al. (2003) indicate that reducing horizontal cell coupling does not affect the strength of horizontal cell feedback signalling.

Carbenoxolone could block gap junction communication between amacrine cells, reducing the effectiveness of IPL surround signalling. However, the main effects of carbenoxolone were not on amacrine cells because it was ineffective in blocking lateral inhibition elicited by dim surround illumination, which was attributed to GABAC receptor-mediated signalling between amacrine and bipolar cells. Also cobalt, which should not block gap junctional signalling, mimicked the effects of carbenoxolone, suggesting that the main effects of carbenoxolone were not in the IPL. Low concentrations of cobalt have been shown to reduce the GABA-evoked current in turtle cones and fish horizontal cells (Kaneko & Tachibana, 1986; Kaneda et al. 1997). However in our studies, cobalt (10 μm) did not affect GABA-dependent dim surround signalling pathways (Fig. 9), suggesting that cobalt, at this concentration, did not affect GABAC receptors in our preparation. The simplest interpretation of our cobalt and carbenoxolone data is that they reduced bright surround inhibition by attenuating horizontal cell feedback to cones.

Is bright surround inhibition also mediated by presynaptic IPL pathways?

Our findings may not rule out a role of the inner retina in bright surround inhibition because GABA may act as a slow modulator of horizontal cell feedback to cones (Kamermans et al. 2002). In this model, the activation of GABA receptors on cone terminals reduces feedback from horizontal cells. GABA receptor blockers should increase this feedback signal, enhancing lateral signalling in the OPL. In agreement with McMahon et al. (2004), we found that GABA receptor blockers did not reduce bright, presynaptic surround signalling, suggesting that it was not mediated by the IPL. It is unclear why bright surround signals are not mediated by the presynaptic IPL pathway. One possibility is that the presynaptic IPL pathway saturates at dim to moderate light intensities, precluding bright intensity signalling. Alternatively, an IPL component of bright surround inhibition might be masked as GABA receptor antagonists block an IPL component while enhancing an OPL component of the steady surround. However, our GAT inhibitor experiments suggested that bright surround inhibition was not mediated by a GABA-dependent, inner retinal feedback pathway (Fig. 11).

Our studies of the effects of IPL-mediated surround inhibition on ganglion cell EPSCs focused on the component mediated by signalling to bipolar cell axon terminals. An additional component of inner retinal surround inhibition is attributed to amacrine cell signalling to ganglion cells (Cook & McReynolds, 1998a; Roska et al. 2000; Flores-Herr et al. 2001). Our results suggest that surround inhibition to bipolar cell axon terminals and ganglion cell dendrites are different. Dim surround intensities, which activated inhibitory inputs to bipolar cell terminals, were less effective in activating direct inhibition of ganglion cells. By contrast, brighter surrounds activated GABAergic inputs to ganglion cells. These findings suggest that different amacrine cell circuits that utilize different complements of GABA receptors were involved in presynaptic versus direct surround inhibition in the IPL. The presynaptic IPL signals were mediated largely by GABAC receptors, whereas the direct inhibitory IPL signals were mediated by GABAA receptors, as previously described (Lukasiewicz & Shields, 1998; Flores-Herr et al. 2001).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants EY08922 and EY02687, Research to Prevent Blindness and The M. Bauer Foundation. The authors thank Drs Paul Cook, Erika Eggers, Iris Fahrenfort, Maarten Kamermans, Carmelo Romano, Maureen McCall and Ronald Gregg for helpful discussion and comments on the manuscript.

References

- Belgum JH, Dvorak DR, McReynolds JS. Strychnine blocks transient but not sustained inhibition in mudpuppy retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1984;354:273–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PB, Lukasiewicz PD, McReynolds JS. Action potentials are required for the lateral transmission of glycinergic transient inhibition in the amphibian retina. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2301–2308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02301.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PB, McReynolds JS. Lateral inhibition in the inner retina is important for spatial tuning of ganglion cells. Nat Neurosci. 1998a;1:714–719. doi: 10.1038/3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PB, McReynolds JS. Modulation of sustained and transient lateral inhibitory mechanisms in the mudpuppy retina during light adaptation. J Neurophysiol. 1998b;79:197–204. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PB, McReynolds JS, Lukasiewicz PD. Action potentials are necessary for wide-field inhibitory signals in the inner plexiform layer of amphibian retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:S1153. [Google Scholar]

- Deng P, Cuenca N, Doerr T, Pow DV, Miller R, Kolb H. Localization of neurotransmitters and calcium binding proteins to neurons of salamander and mudpuppy retinas. Vision Res. 2001;41:1771–1783. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00060-8. 10.1016/S0042-6989(01)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Werblin FS. Temporal contrast enhancement via GABAC feedback at bipolar terminals in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2171–2180. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enz R, Brandstatter JH, Wassle H, Bormann J. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAc recptor rho subunits in the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4479–4490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euler T, Masland RH. Light-evoked responses of bipolar cells in mammalian retina. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1817–1829. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenfort I, Sjoerdsma T, Ripps H, Kamermans M. Cobalt ions inhibit negative feedback in the outer retina by blocking hemichannels on horizontal cells. Vis Neurosci. 2004;21:501–511. doi: 10.1017/S095252380421402X. 10.1017/S095252380421402X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain GL, Dowling JE. Intracellular recordings from single rods and cones in the mudpuppy retina. Science. 1973;180:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.180.4091.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Herr N, Protti DA, Wassle H. Synaptic currents generating the inhibitory surround of ganglion cells in the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4852–4863. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04852.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare WA, Owen G. Receptive field of the retinal bipolar cell: a pharmacological study in the tiger salamander. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2005–2019. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley SH, Yang X-L, Wu SM. Relative contribution of rod and cone inputs to bipolar cells and ganglion cells in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:2086–2098. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose T, Lukasiewicz PD. GABA transporters regulate inhibition in the retina by limiting GABAC receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3285–3292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03285.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamermans M, Fahrenfort I. Ephaptic interactions within a chemical synapse: hemichannel-mediated ephaptic inhibition in the retina. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.016. 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamermans M, Fahrenfort I, Schultz K, Janssen-Bienhold U, Sjoerdsma T, Weiler R. Hemichannel-mediated inhibition in the outer retina. Science. 2001;292:1178–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.1060101. 10.1126/science.1060101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamermans M, Fahrenfort I, Sjoerdsma T. GABAergic modulation of ephaptic feedback in the outer retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:E-2920. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda M, Mochizuki M, Aoki K, Kaneko A. Modulation of GABAC response by Ca2+ and other divalent cations in horizontal cells of the catfish retina. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110:741–747. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.6.741. 10.1085/jgp.110.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko A, Tachibana M. Blocking effects of cobalt and related ions on the gamma-aminobutyric acid-induced current in turtle retinal cones. J Physiol. 1986;373:463–479. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koulen P, Brandstatter JH, Kroger S, Enz R, Bormann J, Wassle H. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAC receptor ρ subunits in the cat, goldfish and chicken retina. J Comp Neurol. 1997;380:520–532. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970421)380:4<520::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-3. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19970421)380:4<520::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij DA, Spekreijse H, Kamermans M. The open- and closed-loop gain-characteristics of the cone/horizontal cell synapse in goldfish retina. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:1256–1265. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.3.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz PD, Maple BR, Werblin FS. A novel GABA receptor on bipolar cell terminals in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1202–1212. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01202.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukasiewicz PD, Shields CR. Different combinations of GABAA and GABAC receptors confer distinct temporal properties to retinal synaptic responses. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:3157–3167. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.6.3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon MJ, Packer OS, Dacey DM. The classical receptive field surround of primate parasol ganglion cells is mediated primarily by a non-GABAergic pathway. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3736–3745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5252-03.2004. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5252-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire G, Maple B, Lukasiewicz P, Werblin F. Gamma-aminobutyrate type B receptor modulation of L-type calcium channel current at bipolar cell terminals in the retina of the tiger salamander. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:10144–10147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangel SC. Analysis of the horizontal cell contributions to the receptive field surround of ganglion cells in the rabbit retina. J Physiol. 1991;442:211–234. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maple BR, Wu SM. Glycinergic synaptic inputs to bipolar cells in the salamander retina. J Physiol. 1998;506:731–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.731bv.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.731bv.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittman S, Taylor WR, Copenhagen DR. Concomitant activation of two types of glutamate receptor mediates excitation of salamander retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1990;428:175–197. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka KI. Functional organization of catfish retina. J Neurophysiol. 1977;40:26–43. doi: 10.1152/jn.1977.40.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naka KI, Witkovsky P. Dogfish ganglion cell discharge resulting from extrinsic polarization of the horizontal cells. J Physiol. 1972;223:449–460. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picaud S, Pattnaik B, Hicks D, Forster V, Fontaine V, Sahel J, Dreyfus H. GABA-A and GABA-C receptors in adult porcine cones: evidence form a photoreceptor-glia co-culture model. J Physiol. 1998;513:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.033by.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.033by.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodieck RW, Stone J. Analysis of receptive fields of cat retinal ganglion cells. J Neurophysiol. 1965;28:832–849. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.5.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roska B, Nemeth E, Orzo L, Werblin FS. Three levels of lateral inhibition: a space-time study of the retina of the tiger salamander. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1941–1951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01941.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roska B, Nemeth E, Werblin FS. Response to change is facilitated by a three-neuron disinhibitory pathway in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3451–3459. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03451.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakmann B, Creutzfeldt OD. Scotopic and mesopic light adaptation in the cat's retina. Pflugers Arch. 1969;313:168–185. doi: 10.1007/BF00586245. 10.1007/BF00586245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Slaughter MM. Multireceptor GABAergic regulation of synaptic communication in amphibian retina. J Physiol. 2001;530:55–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0055m.x. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0055m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CR, Tran MN, Wong RO, Lukasiewicz PD. Distinct ionotropic GABA receptors mediate presynaptic and postsynaptic inhibition in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2673–2682. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-07-02673.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR. TTX attenuates surround inhibition in rabbit retinal ganglion cells. Vis Neurosci. 1999;16:285–290. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899162096. 10.1017/S0952523899162096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibos LN, Werblin FS. The response properties of the steady antagonistic surround in the mudpuppy retina. J Physiol. 1978;278:79–99. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]