Abstract

Studies using single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) have shown that excitability of the corticospinal system is systematically reduced in natural human sleep as compared to wakefulness with significant differences between sleep stages. However, the underlying excitatory and inhibitory interactions on the corticospinal system across the sleep–wake cycle are poorly understood. Here, we specifically asked whether in the motor cortex short intracortical inhibition (SICI) and facilitation (ICF) can be elicited at all in sleep using the paired-pulse TMS protocol, and if so, how SICI and ICF vary across sleep stages. We studied 28 healthy subjects at interstimulus intervals of 3 ms (SICI) and 10 ms (ICF), respectively. Magnetic stimulation was performed over the hand area of the motor cortex using a focal coil and evoked motor potentials were recorded from the contralateral first dorsal interosseus muscle (1DI). Relevant data was obtained from 13 subjects (NREM 2: n = 7; NREM 3/4: n = 7; REM: n = 7). Results show that both SICI and ICF were present in NREM sleep. SICI was significantly enhanced in NREM 3/4 as compared to wakefulness and all other sleep stages whereas in NREM 2 neither SICI nor ICF differed from wakefulness. In REM sleep SICI was in the same range as in wakefulness, but ICF was entirely absent. These results in humans support the hypothesis derived from animal experiments which suggests that intracortical inhibitory mechanisms are involved in the control of neocortical pyramidal cells in NREM and REM sleep, but along different intraneuronal circuits. Further, our findings suggest that cortical mechanisms may additionally contribute to the inhibition of spinal motoneurones in REM sleep.

Previous work has shown that the excitability of the corticospinal system is systematically decreased in all stages of human sleep as compared to wakefulness when the single-pulse TMS protocol is used (Fish et al. 1991; Stalder et al. 1995; Grosse et al. 2002). Additionally, differences between sleep stages could be shown since corticospinal excitability is significantly higher in stage NREM 3/4 as compared to stage NREM 2. However, the most pronounced reduction of excitability is found in REM (Grosse et al. 2002). These findings have been interpreted as an indication that the balance between inhibitory and excitatory influences in the corticospinal system is specific for each state of vigilance. To date, the precise mechanisms of inhibitory and excitatory system interactions at cerebral and spinal levels remain to be elucidated for the respective sleep stages.

Experiments in animals have demonstrated that inhibition at the cortical level is highly dynamic across the sleep–wake cycle. Inhibition of principal cortical cells such as pyramidal cells is either realized through disfacilitation leading to the absence of excitatory synaptic activity (Llinás, 1964; Contreras et al. 1996) or through GABAergic synaptic inhibition (Timofeev et al. 2001). Thus in the cat, for example, disfacilitation is prominent during the hyperpolarizing phase of cortical motoneurones in slow-wave sleep (Steriade, 1974). Conversely, in REM synaptic inhibition mediated through the activity of GABAA-ergic interneurones has been identified as an important inhibitory mechanism (Timofeev et al. 2001). These singular findings reflect a much more complex but well-orchestrated interplay of different inhibitory and excitatory mechanisms, which lie at the base of each state of vigilance.

Here we investigate sleep stage-related changes in short intracortical inhibition (SICI) and intracortical facilitation (ICF) using the classical TMS paired-pulse protocol (Kujirai et al. 1993) to measure inhibitory and excitatory influences on pyramidal cells in the motor cortex mediated through different cortical interneuronal pathways (Ilic et al. 2002). Despite the anatomical and functional complexity of interneuronal circuits it seems particularly promising to investigate human sleep with the paired-pulse TMS protocol, since several studies have strongly suggested that this method exclusively reflects the effects of cortical interneurones on pyramidal cells and that excitability changes of spinal motoneurones can be disregarded. Thus, Kujirai et al. (1993) showed that a magnetic conditioning stimulus followed by an electrical test stimulus fails to produce SICI. Additionally, Di Lazzaro et al. (1998) confirmed that no descending volleys can be recorded from the spinal cord with subthreshold magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex. Finally, Kujirai et al. (1993) as well as Ziemann et al. (1996a) demonstrated that the time-locked H-reflex is unaffected.

The paired-pulse protocol has substantially helped to pharmacologically characterize SICI-related interneuronal circuits as the latter are enhanced when GABAA-ergic substances or NMDA-receptor antagonists are applied (Ziemann et al. 1996a). These findings have led to the assumption that SICI mirrors the activity level of GABAA-ergic interneurones (Ziemann, 1999; Boroojerdi, 2002). Conversely, most authors have suggested an excitatory glutamatergic interneuronal mechanism to be responsible for ICF (Amassian et al. 1987; Ilic et al. 2002). The latter might be under GABAergic inhibitory influence as ICF decreases with the application of GABAergic substances (Ziemann et al. 1996b; Ziemann, 1999). Other research based on single cortical cell recordings has depicted an even more complex scenario with a diversity of inhibitory GABAergic cortical interneurones under glutamatergic, histaminergic, serotonergic, nicotinergic and muscarinergic influences to effectively realize the fine-tuning of the entire cortical network (Freund, 2003).

Methods

Subjects

We examined 28 healthy drug-free volunteers (15 men, 13 women) aged between 18 and 42 years (mean: 26.4 years) with no history of medical, neurological and psychiatric disease, or sleep disorder. Subjects were fully informed about the nature of the experiments, which had been approved by the ethics committee of our institution according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and gave written consent to the procedures. All subjects underwent partial sleep deprivation during the night prior to the study, with a sleep time of 3 h before 6:00 am. It was intended that partial sleep deprivation would render the subjects more indifferent to the laboratory surroundings in which they should sleep in order to improve overall sleep performance. After getting up they had to refrain from any stimulating substances such as coffee or tea. Moderate alcohol ingestion was allowed up to 36 h prior to the examination.

Sleep stage assessment

To allow appropriate sleep stage assessment during the experiment an electroencephalogram (EEG; F1, F2, Fz, Cz, O1, O2, A1 and A2 according to the 10–20 system), electro-oculogram (EOG) and submental electromyogram (EMG) were continuously recorded on a mobile electroencephalography device (Nihon Koden). The time constant of the EEG recording was set at 0.3 s and low-pass-filtered at 70 Hz. The sampling rate was 256 Hz. Sleep stages were scored in accordance with the criteria of Rechtschaffen & Kales (1968). For all sleep stages, stage-specific EEG features had to appear for at least 3 min before TMS was started. The assessment of sleep stages during the experiment was controlled off-line by one of the investigators experienced with sleep stage assessment but not participating in the respective trial.

TMS

Magnetic stimuli were delivered using a Magstim 200 stimulator (Whitland, Dyfed, UK; monophasic pulse, peak magnetic field of up to 2 T). Two stimulators were connected to a figure-of-eight-shaped coil through a Bistim module (Magstim). The stimulation coil was positioned tangentially on the scull with the handle pointing backwards and the coil was rotated ∼45 deg from the subject's midsagittal axis. Induced currents were postero-anteriorly directed. Ag–AgCl surface electrodes of 9 mm diameter were placed over the 1DI of both hands. Motor-evoked potentials were recorded using an electromyograph (Neuropack 8, Nihon Kodon) with a bandpass filter of 3 Hz to 3 kHz and a sampling rate of 5000 Hz.

To assess SICI and ICF, focal TMS was applied to the hand area of the motor cortex as described by Kujirai et al. (1993). Stimuli were delivered to the hemisphere which could be accessed more easily depending on the factual body and head position during sleep. The optimal positions for coil placement were identified for both hemispheres before the experiment and marked on the scalp with fluorescent patches.

Since motor thresholds vary between the different sleep stages (Grosse et al. 2002) the motor threshold (motor-evoked potential (MEP) of > 100 µV in 5 out of 10) was assessed for each sleep stage separately. The conditioning stimulus was set at 80% of the resting motor threshold (RMT) while the test stimulus was of a suprathreshold intensity producing an MEP for each single stimulus of (1 mV (0.5–1.5 mV). As thresholds in sleep are generally higher than in wakefulness we excluded those subjects in whom it required more than 80% of maximal stimulator output to elicit the test stimulus of 1 mV in order to avoid arbitrary stimulus intensities in the higher range of the stimulus–response curve.

Interstimulus intervals (ISIs) were set at 3 ms for SICI and 10 ms for ICF as these are a good representation of SICI and ICF, respectively. Twenty-four stimuli were randomly delivered (8 × test stimulus, 8 × conditioned stimulus at an ISI of 3 ms, 8 × conditioned stimulus at an ISI of 10 ms) in each sleep stage. The mean amplitude of the conditioned MEPs was expressed as a percentage of the mean amplitude of the test MEPs.

All subjects in whom the experiment could successfully be completed in at least one sleep stage were also investigated in wakefulness according to the same protocol and in the same hemisphere as during sleep.

Statistics

To test for statistical significance the grand mean results from individual subjects were entered into a repeated measures general linear model using ISI (2 levels: 3 ms and 10 ms) and vigilance states (4 levels: awake, NREM 2, NREM 3/4 and REM) as the main effects. As data proved to be spherical (Mauchley's test for sphericity: P = 0.336) no correction had to be applied. When differences were significant (P < 0.05), post hoc pair-wise comparison with Scheffé's correction was performed between sleep stages and wakefulness and between the individual sleep stages.

Results

Assessment of SICI/ICF was feasible in 13 subjects in at least one sleep stage (NREM 2: n = 7; NREM 3/4: n = 7; REM: n = 7). In the other subjects (n = 15) either motor thresholds in sleep were too high, or the amplitude of the test stimulus could not be kept constant, or subjects awoke repetitively during the recording. Averaged RMTs and test stimulus intensities for each sleep stage as they compare to wakefulness are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

| A. Averaged resting motor threshold for each sleep stage, matching values for wakefulness (% of max. stimulus output) and difference between sleep and wakefulness | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | Awake | Difference | |

| NREM 2 | 57 ± 11% | 39 ± 6% | 18% |

| NREM 3/4 | 49 ± 7% | 44 ± 4% | 5% |

| REM | 59 ± 3% | 41 ± 2% | 18% |

| B. Averaged test stimulus intensities for each sleep stage, matching values for wakefulness (% of max. stimulus output) and difference between sleep and wakefulness | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep | Awake | Difference | |

| NREM 2 | 73 ± 7% | 47 ± 4% | 26% |

| NREM 3/4 | 61 ± 4% | 48 ± 3% | 13% |

| REM | 70 ± 4% | 47 ± 2% | 23% |

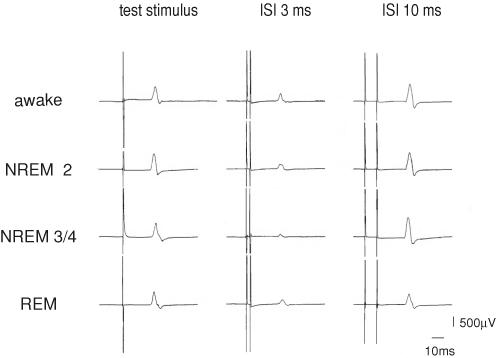

Figure 1 illustrates a representative example of the characteristic SICI and ICF in sleep compared to wakefulness in a single subject in whom all three sleep stages were assessed. SICI and ICF can be clearly identified in both NREM sleep stages. However, SICI is more pronounced in NREM 3/4 compared to NREM 2. In REM sleep SICI is present at the same level as in wakefulness and NREM 2, but ICF is absent.

Figure 1. Example of the characteristic short intracortical inhibition (SICI) and intracortical facilitation (ICF) in sleep compared to wakefulness in a single subject.

Averaged MEPs of 8 test stimuli, 8 conditioned stimuli at an ISI of 3 ms, and 8 conditioned stimuli at an interstimulus interval (ISI) of 10 ms, respectively, in a single subject for all four states of vigilance. Note that amplitude of test stimulus is kept constant across the different sleep stages and in wakefulness. In NREM 3/4 sleep there is a marked enhancement of inhibition at ISI 3 ms while ICF (ISI 10 ms) is absent in REM sleep.

These individual results could be confirmed for the averaged data of our sample and significant interaction between ISI and state of vigilance (F(6,18)= 8.92; P = 0.005) was present and revealed specific patterns for each sleep stage.

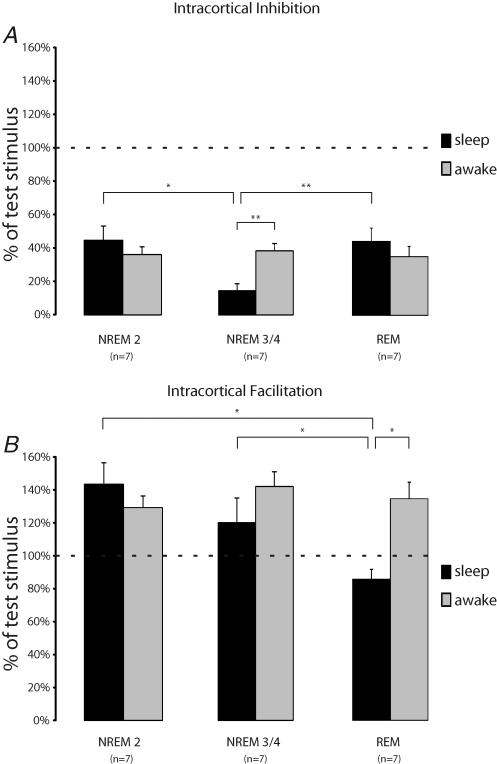

NREM 2

In NREM 2 no significant changes either for SICI or ICF were present compared to wakefulness (Fig. 2). With 45 ± 9% (mean ± s.e.m.) of the test stimulus amplitude SICI was slightly above the level for wakefulness with 37 ± 5%. Similarly, ICF was in the same range as during wakefulness (NREM 2: 143 ± 13%versus wakefulness: 129 ± 7%).

Figure 2. Averaged data for SICI (A) and ICF (B) for different sleep stages compared to wakefulness.

For each sleep stage only data from the same individuals were compared to those in wakefulness. Error bars indicate s.e.m. Horizontal dotted lines represent 100% of test stimulus. Note that in NREM 3/4 sleep SICI is significantly different from wakefulness and from the two other sleep stages, whereas in REM sleep ICF is absent. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005.

NREM 3/4

In NREM 3/4 profound enhancement of SICI (15 ± 4%versus 39 ± 4%) was present which was significantly different from both wakefulness (P < 0.05) and the other two sleep stages (Fig. 2; NREM 2: P < 0.05; REM: P < 0.05). Considering subjects individually, SICI was enhanced by a factor between 2.5 and 17.5 (mean: 5.6 ± 2.2) compared to the respective SICI in wakefulness. In contrast, although ICF in NREM 3/4 sleep was lower than in wakefulness (120 ± 14%versus 142 ± 9%) this difference was not statistically significant.

REM

REM sleep showed a slight decrease of SICI compared to wakefulness, which, however, did not attain statistical significance (Fig. 2A; 44 ± 8%versus 35 ± 6% in wakefulness; P = 0.41). ICF in REM sleep was entirely absent in all subjects (Fig. 2B; range at ISI of 10 ms: 74–101%) and averaged data was statistically different from wakefulness (86 ± 4%versus 135 ± 10%; P < 0.05) and all other sleep stages (NREM 2: P < 0.05; NREM 3/4: P = 0.05).

As stated for the single-pulse protocol (Grosse et al. 2002), mean MEP onset latencies in sleep are also slightly higher in this study using the paired-pulse protocol. In this sample the mean MEP latency differences between sleep stage and matching data in wakefulness were 0.7 ± 0.12 ms in NREM 2, 1.1 ± 0.24 ms in NREM 3/4 and 0.7 ± 0.22 ms in REM.

Constant test stimulus amplitudes across different states of vigilance

As excitability of the corticospinal system can differ markedly between sleep stages and between sleep and wakefulness it is crucial that MEP amplitudes of the test stimulus are kept constant across the different stages of vigilance (Orth et al. 2003). To prove that the experimental conditions for each stage of vigilance were comparable, all test stimulus MEP amplitudes from each subject were averaged and a two-tailed Student's t test was performed. For all sleep stages averaged MEP amplitudes of the test stimulus were in a similar range, between 0.75 and 0.93 mV for the different sleep stages and wakefulness (NREM 2: 0.92 ± 0.06 versus 0.93 ± 0.03 mV in wakefulness; NREM 3/4: 0.90 ± 0.1 versus 0.93 ± 0.03 mV in wakefulness; REM: 0.76 ± 0.03 versus 0.92 ± 0.03 mV in wakefulness). Although variance was slightly greater for sleep stages compared to wakefulness, differences were not statistically significant, either between sleep stages and wakefulness or across sleep stages (NREM 2 versus wakefulness: P = 0.91; NREM 3/4 versus wakefulness: P = 0.98; REM versus wakefulness: P = 0.06; NREM 2 versus NREM 3/4: P = 0.88; NREM 2 versus REM: P = 0.11; NREM 3/4 versus REM; P = 0.25).

It is noteworthy that in one subject during NREM 3/4 and in another subject during REM, both of whom were excluded from the aggregated data because of inconstant MEP amplitudes of the test stimulus, the characteristic results described above could, nevertheless, be obtained. For the one subject in NREM 3/4, SICI was at 4% with an averaged test stimulus MEP amplitude of 1.78 mV (min: 0.67 mV; max: 3.74 mV). In the other subject in REM the percentage of the test stimulus attained 66% with an ISI of 10 ms at an averaged test stimulus amplitude of 3.03 mV (min: 1.99 mV; max: 4.84 mV).

Discussion

We can show that both SICI and ICF are present in human NREM sleep. SICI could also be demonstrated in REM sleep; however, in this stage of vigilance ICF was entirely absent. Compared to wakefulness no relevant changes of SICI were present in NREM 2, but there was a drastic enhancement of SICI in NREM 3/4. Conversely, in NREM sleep no significant changes compared to wakefulness could be shown for ICF. Similar to NREM 2, SICI in REM did not differ from wakefulness, yet the complete absence of ICF in REM sleep seems to be a unique feature across the sleep–wake cycle. Despite the great inter-individual and intra-individual variability reported for paired-pulse TMS (Wassermann, 2002; Orth et al. 2003), we could elicit the characteristic pattern for each stage of vigilance in each single subject in whom assessment was feasible. However, having used the classical paired-pulse protocol according to Kujirai et al. (1993), more subtle changes in SICI in NREM 2 and REM might have escaped notice that could have been detected by other protocols (Ilic et al. 2002, 2004), but which cannot be applied in sleep due to an unsuitable amount of stimuli.

Effects of sleep deprivation

It can be assumed that partial sleep deprivation does not have any effect on parameters of cortical excitability during sleep itself as effects on EEG have only been shown after prolonged total sleep deprivation of several days (Bonnet, 2000). Further, changes of cortical excitability as assessed with TMS are minimal even in wakefulness (Manganotti et al. 2001; Civardi et al. 2001). Consequently, we could not observe any abnormal EEG patterns which would have indicated abnormal cortical excitability during sleep in our subjects.

SICI and ICF in NREM sleep

We assume that the difference in SICI between NREM 2 and NREM 3/4 reflects varying degrees of synaptic inhibition across the NREM sleep stages mediated through GABAA-ergic cortical interneurones (Ziemann et al. 1996a; Ziemann, 1999). As the enhancement of SICI in NREM 3/4 seemingly parallels the progression from NREM 2 to NREM 3/4 GABAergic synaptic inhibition at the cortical level might be an important physiological mechanism which parallels the progression towards deeper NREM sleep.

Since MEP configurations in the paired-pulse condition depend on the number of trans-synaptically induced cortico-spinal volleys (i.e. I-waves) prolongation of MEP onset latency could in theory point towards a selective inhibition of early I-waves as a result of a reorganization of the intracortical inhibitory networks. Despite the slightly higher increase of MEP onset latency in NREM 3/4 as compared to NREM 2 and REM, we do not think that this finding could immediately be attributed to a suppression of early I-waves because this increase does not attain the average latency of an I-wave of between 1.4 and 1.8 ms (Di Lazzaro et al. 2003).

Importantly, the enhancement of SICI in NREM 3/4 is not accompanied by a substantial decrease of ICF, in contrast to the results of administrating GABAA-ergic drugs during wakefulness (Ziemann et al. 1996b). It can therefore be argued that the excitatory glutamatergic interneuronal network remains basically unaffected in NREM sleep compared to wakefulness.

Increased SICI has been found after pharmacological modification with GABAA-ergic substances or antigluta-matergic drugs such as riluzole (Ziemann, 1999). Although NMDA antagonistic action in NREM 3/4 sleep cannot entirely be ruled out, the fact that SICI is profoundly enhanced in NREM 3/4 would be in line with previous investigations in animals showing the highest cortical release of GABA in NREM 3/4 (Jasper et al. 1965). Accordingly, the activity of GABA-containing interneurones during NREM 3/4 sleep is particularly high (Steriade & Hobson, 1976). Thus, it is likely that GABAergic inhibition accounts for enhanced SICI in NREM 3/4. This view is further corroborated by the fact that GABAA-ergic substances greatly enhance NREM 3/4 thereby suggesting a relevant role of GABAA-ergic intracortical transmission for the induction and maintenance of this particular sleep stage (Gottesmann, 2002). In summary, NREM 3/4 can be regarded as a state of vigilance in which enhanced SICI parallels a state of high activity of pyramidal cells in deeper sleep stages (Contreras & Steriade, 1995) for which unchanged ICF and higher corticospinal excitability in NREM 3/4 compared to NREM 2 (Grosse et al. 2002) are strong indications.

SICI and ICF in REM sleep

The absence of ICF in REM, in contrast to wakefulness and NREM sleep, supports the hypothesis that different inhibitory mechanisms contribute to the specific organization of the motor cortex in each state of vigilance, in particular as in REM sleep SICI remains unchanged. The absence of ICF strongly suggests that in REM the excitatory glutamatergic interneuronal network cannot be activated in the same way as in wakefulness or in NREM sleep. Hypoexcitability of the glutamatergic excitatory interneuronal network can be realized through disfacilitation of selected neuronal elements within the network, including pyramidal cells themselves. The latter may be targeted either through intracortical or thalamocortical pathways (Timofeev et al. 2001). Alternatively, synaptic GABAergic inhibitory control of intracortical glutamatergic neurones must also be considered (Boroojerdi, 2002; Freund, 2003). To explain our findings in REM sleep we would tend to favour the latter interpretation as previous animal data showed that fast-spiking neurones in REM, electrophysiologically identified as inhibitory GABAergic interneurones, are responsible for synaptic inhibition on neocortical pyramidal cells during ocular saccades (Timofeev et al. 2001).

Our findings suggest that in REM sleep relevant inhibitory influences on the spinal motoneurone might concomitantly be mediated through the corticospinal system and not exclusively through reticulospinal pathways (Jouvet & Delorme, 1965) as usually suggested. Consequently, decreased corticospinal excitability found in REM sleep upon TMS using single pulses (Fish et al. 1991; Stalder et al. 1994; Grosse et al. 2002) might at least partly be attributed to cortical mechanisms as a consequence of the deactivated excitatory glutamatergic interneuronal network. Nevertheless, it cannot immediately be assumed that ICF is absent over the whole neocortex because functional imaging studies using positron emission tomography (PET) have demonstrated a selective cortical activation–deactivation pattern in REM (Braun et al. 1997; Buchsbaum et al. 2001). Therefore, absent ICF may only be a specific signature of REM in the motorcortex and perhaps in some other cortical areas, but not necessarily in all.

For future research the finding of an absent ICF in REM might have some implications for the study of sleep-associated motor disorders. For instance in the case of REM sleep behaviour disorder, e.g. in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) and multisystem atrophy (MSA), the occurrence of pathological movements in REM might not solely be attributed to subcortical mechanisms (Gilman et al. 2003) since it is compelling to suggest that basal ganglia diseases, such as PD and MSA, lead to disinhibition of normally suppressed glutamatergic excitatory cortical circuits in REM, as it is known from wakefulness (Strafella et al. 2000; Pierantozzi et al. 2001).

Conclusions

In summary, we can show that inhibition of neocortical pyramidal cells is present at the cortical level through intracortical mechanisms in sleep, most likely using different circuits in NREM and REM sleep. More specifically GABAergic synaptic inhibition seems to be present in both NREM and REM sleep to a varying extent, whereas the intracortical glutamatergic excitatory network is significantly depressed in REM as opposed to NREM sleep. Although the number of subjects studied in this study was limited, the characteristic pattern for each sleep stage could be demonstrated in each single individual in whom assessment was feasible. Nevertheless, our results require confirmation in a larger group. Further studies are needed to better define the pharmacological basis of cortical interneuronal inhibitory and excitatory control of principal cells in human sleep by using specific receptor agonists and antagonists and to explore the relevance of these findings for motor disorders in sleep.

Acknowledgments

We thank Karin Reichel, Margot Trautmann and Kyong Soo Shin-Nolte for their kind assistance and Sein Schmidt for linguistic advice. Further, we would like to thank John Rothwell for his very helpful comments and criticism.

References

- Amassian VE, Stewart M, Quirk GJ, Rosenthal JL. Physiological basis of motor effects of a transient stimulus to cerebral cortex. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:74–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet M. Sleep deprivation. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Boroojerdi B. Pharmacological influences on TMS effects. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;19:255–271. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun AR, Balkin TJ, Wesenten NJ, Carson RE, Varga M, Baldwin P, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow throughout the sleep-wake cycle. An H2(15)O PET study. Brain. 1997;120:1173–1197. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.7.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchsbaum MS, Hazlett EA, Wu J, Bunney WE., Jr Positron emission tomography with deoxyglucose-F18 imaging of sleep. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:S50–S56. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00339-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civardi C, Boccagni C, Vicentini R, Bolamperti L, Tarletti R, Varrasi C, et al. Cortical excitability and sleep deprivation: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:809–812. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.6.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras D, Steriade M. Cellular basis of EEG slow rhythms: a study of dynamic corticothalamic relationships. J Neurosci. 1995;15:604–622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00604.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras D, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Mechanisms of long-lasting hyperpolarizations underlying slow sleep oscillations in cat corticothalamic networks. J Physiol. 1996;494:251–264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Oliviero A, Pilato F, Mazzone P, Insola A, Ranieri F, Tonali PA. Corticospinal volleys evoked by transcranial stimulation of the brain in conscious humans. Neurol Res. 2003;25:143–150. doi: 10.1179/016164103101201292. 10.1179/016164103101201292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Restuccia D, Oliviero A, Profice P, Ferrara L, Insola A, et al. Magnetic transcranial stimulation at intensities below active motor threshold activates intracortical inhibitory circuits. Exp Brain Res. 1998;119:265–268. doi: 10.1007/s002210050341. 10.1007/s002210050341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish DR, Sawyers D, Smith SJ, Allen PJ, Murray NM, Marsden CD. Motor inhibition from the brainstem is normal in torsion dystonia during REM sleep. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:140–144. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.2.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF. Interneuron diversity series: rhythm and mood in perisomatic inhibition. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00227-3. 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman S, Koeppe RA, Chervin RD, Consens FB, Little R, An H, Junck L, et al. REM sleep behaviour disorder is related to striatal monoaminergic deficit in MSA. Neurology. 2003;61:29–34. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073745.68744.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesmann C. GABA mechanisms and sleep. Neuroscience. 2002;111:231–239. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00034-9. 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse P, Khatami R, Salih F, Kühn A, Meyer B-U. Excitability of the corticospinal system in natural human sleep as assessed by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology. 2002;59:1988–1991. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000038762.11894.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic TV, Meintzschel F, Cleff U, Ruge D, Kessler KR, Ziemann U. Short-interval paired-pulse inhibition and facilitation of human motor cortex: the dimension of stimulus intensity. J Physiol. 2002;545:153–167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030122. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.030122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic TV, Jung P, Ziemann U. Subtle hemispheric asymmetry of motor cortical inhibitory tone. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:330–340. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.09.017. 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper HH, Khan RT, Elliott KAC. Amino acids released from the cerebral cortex in relation to its state of activation. Science. 1965;147:1448–1449. doi: 10.1126/science.147.3664.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouvet M, Delorme F. Locus coeruleus et sommeil paradoxal. C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1965;159:895–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Thompson PD, Ferbert A, et al. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol. 1993;471:501–519. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás RR. Mechanism of supraspinal action upon spinal cord activities. Difference between reticular and cerebellar inhibitory action upon alpha extensor motoneurons. J Neurophysiol. 1964;27:1117–1126. doi: 10.1152/jn.1964.27.6.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganotti P, Palermo A, Patuzzo S, Zanette G, Fiaschi A. Decrease of motor cortical excitability in human subjects after sleep deprivation. Neurosci Lett. 2001;304:153–156. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01783-9. 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)01783-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth M, Snijders AH, Rothwell JC. The variability of intracortical inhibition and facilitation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:2362–2369. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00243-8. 10.1016/S1388-2457(03)00243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierantozzi M, Palmieri MG, Marciani MG, Bernardi G, Giacomini P, Stanzione P. Effect of apomorphine on cortical inhibition in Parkinson's disease patients: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Exp Brain Res. 2001;141:52–62. doi: 10.1007/s002210100839. 10.1007/s002210100839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques, and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. Bethesda, MD, USA: US Dept of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Stalder S, Rösler KM, Nirkko AC, Hess CW. Magnetic stimulation of the human brain during phasic and tonic REM sleep. recordings from distal and proximal muscles. J Sleep Res. 1995;4:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M. Inhibitory processes and interneuronal apparatus in the motor cortex during sleep and waking. J Neurophysiol. 1974;37:1065–1092. doi: 10.1152/jn.1974.37.5.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, Hobson JA. Neuronal activity during the sleep waking cycle. Prog Neurobiol. 1976;6:155–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strafella AP, Valzania F, Nassetti SA, Tropeani A, Bisulli A, Santangelo M, et al. Effects of chronic levodopa and pergolide treatment on cortical excitability in patients with Parkinson's disease: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:1198–1202. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00316-3. 10.1016/S1388-2457(00)00316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timofeev I, Grenier F, Steriade M. Disfacilitation and active inhibition in the neocortex during the natural sleep–wake cycle: An intracellular study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1924–1929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041430398. 10.1073/pnas.041430398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassermann EM. Variation in the response to transcranial magnetic brain stimulation in the general population. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00144-x. 10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00144-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann U. Intracortical inhibition and facilitation in the conventional paired TMS paradigm. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;51(suppl.):127–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann U, Lonnecker S, Steinhoff BJ, Paulus W. Effects of antiepileptic drugs on motor cortex excitability in humans: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Ann Neurol. 1996a;40:367–378. doi: 10.1002/ana.410400306. 10.1002/ana.410400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann U, Rothwell JC, Ridding MC. Interaction between intracortical inhibition and facilitation in human motor cortex. J Physiol. 1996b;496:873–881. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]