Abstract

The medial septum and diagonal band complex (MS/DB) is important for learning and memory and is known to contain cholinergic and GABAergic neurones. Glutamatergic neurones have also been recently described in this area but their function remains unknown. Here we show that local glutamatergic neurones can be activated using 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) and the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline in regular MS/DB slices, or mini-MS/DB slices. The spontaneous glutamatergic responses were mediated by AMPA receptors and, to a lesser extend, NMDA receptors, and were characterized by large, sometimes repetitive activity that elicited bursts of action potentials postsynaptically. Similar repetitive AMPA receptor-mediated bursts were generated by glutamatergic neurone activation within the MS/DB in disinhibited organotypic MS/DB slices, suggesting that the glutamatergic responses did not originate from extrinsic glutamatergic synapses. It is interesting that glutamatergic neurones were part of a synchronously active network as large repetitive AMPA receptor-mediated bursts were generated concomitantly with extracellular field potentials in intact half-septum preparations in vitro. Glutamatergic neurones appeared important to MS/DB activation as strong glutamatergic responses were present in electrophysiologically identified putative cholinergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurones. In agreement with this, we found immunohistochemical evidence that vesicular glutamate-2 (VGLUT2)-positive puncta were in proximity to choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-, glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67)- and VGLUT2-positive neurones. Finally, MS/DB glutamatergic neurones could be activated under more physiological conditions as a cholinergic agonist was found to elicit rhythmic AMPA receptor-mediated EPSPs at a theta relevant frequency of 6–10 Hz. We propose that glutamatergic neurones within the MS/DB can excite cholinergic and GABAergic neurones, and that they are part of a connected excitatory network, which upon appropriate activation, may contribute to rhythm generation.

One of the most important inputs to the hippocampus originates from ascending fibres of principal neurones situated in the medial septum and diagonal band complex (MS/DB) (Chandler & Crutcher, 1983; Baisden et al. 1984; Amaral & Kurz, 1985). There is now overwhelming evidence showing that this powerful septo-hippocampal pathway can generate theta rhythm (Petsche et al. 1962; Stumpf et al. 1962; Gogolak et al. 1968; Alonso et al. 1987); a hippocampal 4–12-Hz oscillation prominent during immobility and exploratory movements (Vanderwolf, 1969; Bland & Bland, 1986; Vinogradova, 1995; Vertes & Kocsis, 1997) and critical in memory formation (Petsche et al. 1962; Winson, 1978; Bland & Bland, 1986; Smythe et al. 1991; Bland et al. 1994). A large number of investigations have suggested that the population of septo-hippocampal neurones may belong to one of two phenotypes: cholinergic or GABAergic (Baisden et al. 1984; Panula et al. 1984; Brashear et al. 1986; Kiss et al. 1990), which may drive hippocampal neurones by firing rhythmic bursts at theta frequency (Toth et al. 1997; Kocsis & Li, 2004).

It is interesting that there is increasing evidence that a third population of neurones is present in the MS/DB. It has been acknowledged for some time that a portion of MS/DB neurones cannot be identified with cholinergic and GABAergic markers and could in fact be glutamatergic (Kiss et al. 1997; Gritti et al. 1997). Indirect evidence for glutamate neurones in the MS/DB was obtained using phosphate-activated glutaminase (the enzyme thought to be involved in the synthesis of the neurotransmitter glutamate) or glutamate itself, and by the retrograde transport of [3H]aspartate in septal neurones (Gonzalo-Ruiz & Morte, 2000; Manns et al. 2001; Kiss et al. 2002). We have recently provided strong evidence for the presence of glutamate neurones in the MS/DB using single-cell multiplex RT-PCR by identifying a subpopulation of septo-hippocampal neurones that express mRNAs for the vesicular glutamate transporters type 1 and/or 2 (VGLUT1/2) (Sotty et al. 2003; Danik et al. 2003, 2005). Together with the vesicular glutamate transporters type 3 (VGLUT3), these transporters are presumed to be contained in neurones that have the capacity to use glutamate as neurotransmitter (Moriyama & Yamamoto, 2004). In agreement with our results, the expression of VGLUT2 transcripts was also reported by other groups (Hisano et al. 2000; Fremeau et al. 2001; Lin et al. 2003) whereas the presence of the VGLUT2 protein in the cell body of numerous neurones of the MS/DB was demonstrated in colchicine-treated rats (Hajszan et al. 2004).

These glutamatergic neurones could potentially play an important physiological role in the activity of the MS/DB and septo-hippocampal pathway as earlier studies have shown that intraseptal injection of glutamate receptor antagonists produces significant reduction in hippocampal learning and memory (Izquierdo et al. 1992; Izquierdo, 1994). However, whether glutamatergic neurones of the MS/DB can provide synaptic input within this area remains to be determined. Whereas electrically evoked or spontaneous EPSPs (Segal, 1986; Armstrong & MacVicar, 2001) are known to be present in the MS/DB, it is not known whether these responses originate from local MS/DB glutamatergic neurones and/or from the significant glutamatergic input coming from outside the MS/DB (Leranth & Kiss, 1996; Leranth et al. 1999; Jaskiw et al. 1991; Kiss et al. 2000; Bokor et al. 2002). In this study, we have investigated whether MS/DB glutamatergic neurones can mediate local excitation to GABAergic and cholinergic neurones. The present experiments were performed using a variety of preparations including cultured organotypic MS/DB slices devoid of extrinsic glutamatergic afferents in order to investigate exclusively local synaptic input from MS/DB glutamatergic neurones. Moreover, using an intact preparation of the septum in vitro, we have examined if MS/DB glutamatergic neurones were connected and could be activated synchronously, a property potentially important for pacemaker activity and oscillations. We present novel evidence that glutamatergic neurones within the MS/DB can generate powerful excitatory inputs to cholinergic and GABAergic neurones, are organized into a local excitatory network and can be activated by cholinergic agonists. These findings suggest that intrinsic glutamatergic neurones may play an important role in the MS/DB, and subsequently by modulating septo-hippocampal neurones, in hippocampal activity.

Methods

Animals and materials

All experiments were performed using Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, St-Constant, Quebec, Canada). Animal care was provided according to protocols and guidelines approved by the McGill University Animal Care Committee and the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Bicuculline, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), carbachol, glucose and all inorganic salts were obtained from Sigma (Oakville, Ontario, Canada). 6,7-Dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX) and dl-2-amino-5-phophonopentanoic acid (DL-APV) were from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). All drugs were diluted in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) from previously prepared stock solutions that were prepared in deionized H2O and stored at –20°C. All drugs were delivered by bath application.

Acute MS/DB slice preparation

Rats (8–17 days (d) old) were killed by decapitation and the brain was rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold ACSF, pH 7.4, equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2 and containing (mm): NaCl 126, NaHCO3 24, glucose 10, KCl 3, MgSO4 2, NaH2PO4 1.25, ascorbic acid 0.4, thiourea 0.8 and CaCl2 1.2. Coronal slices (350 μm thick) containing the MS/DB were cut with a Vibroslice (Campden Instruments Ltd, UK) and placed in a Petri dish containing oxygenated ACSF. Slices were further trimmed to include either the MS/DB and lateral septum (whole-septum slice) or the MS/DB alone (MS/DB mini-slice). After 1–1.5 h, single slices were transferred to a Plexiglas recording chamber on the stage of a Nikon microscope (Eclipse E600FN) equipped with Nomarski optics, and continuously perfused with oxygenated ACSF (containing 2 mm CaCl2; room temperature, ∼24°C) at a rate of 1–2 ml min−1 for electrophysiological recordings. Cells were visualized using a 40 × water immersion objective.

MS/DB organotypic slices

Coronal 350 μm-thick slices of septum were cut as above from the brains of 6- to 9-day-old rats in Hanks' buffered salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 25 mm Hepes (both from Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) and 25 mm glucose. The MS/DB area of the septum was dissected out with a scalpel blade and grown on patches of polytetrafluoroethylene membrane placed in Millicell-CM culture inserts (both from Millipore, Ontario, Canada) according to the interface culture method (Stoppini et al. 1991). The culture medium (50% minimal essential medium, 25% HBSS, 25 mm Hepes, 25% horse serum (all from Invitrogen) and 25 mm glucose) was replaced 24 h after dissection and every 2 days thereafter. For electrophysiological experiments, slices cultured for 4–6 days in vitro were transferred to the recording chamber and continuously perfused with oxygenated ACSF as described above. For immunohistochemistry, we used 15 slices at 4 days in vitro. Colchicine was used to disrupt axoplasmic transport in order to visualize the perikarya of VGLUT2-containing neurones (Kreutzberg, 1969). Accordingly, one-third of the slices were exposed to 10 μm colchicine (Sigma) for 1 h followed by a medium change. After 24 h (5 days in vitro), all slices were rinsed briefly in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.3) and processed for immunohistochemistry.

Intact half-septum preparation

The brain from 8- to 17-day-old rats was removed and dropped into a pre-cooled high-sucrose modified ACSF solution (mACSF; Jones et al. 1999) with the following composition (mm): sucrose 252, KCl 3, MgSO4 2, NaHCO3 24, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 1.2 and glucose 10; pH to 7.4 with 95% O2–5% CO2. The cerebellum and frontal part of the brain were removed and a sagital cut was made through the interhemispheric sulcus to separate the two hemispheres (method adapted from Khalilov et al. 1997). The half-septum and hippocampus were carefully dissected out from each hemisphere by inserting a flat spatula in the lateral ventricle and sliding along both dorsal and ventral surfaces of hippocampus and septum. The half-septa were separated from the hippocampus by cutting the septo-hippocampal fibres with a scalpel. Each half-septum was left to rest in high-sucrose solution (room temperature) for 1–3 h prior to the start of experiments. For electrophysiology, single half-septa were transferred to a fully submerged recording chamber (same as for slices), weighted on a nylon mesh and perfused with oxygenated ACSF (3–4 ml min−1). A 30-min rest was allowed before recordings started. Placement of the half-septum was such that the MS/DB was at the surface of the preparation (see Fig. 3A) thereby allowing direct access for the recording electrodes. A 10 × objective was used to visualize the positioning of electrodes in this preparation.

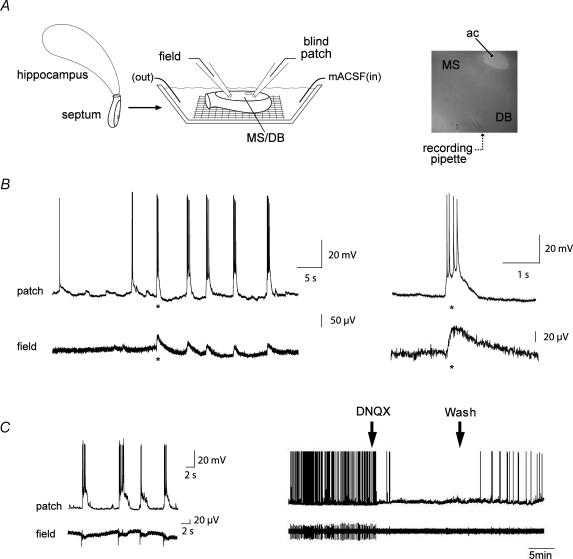

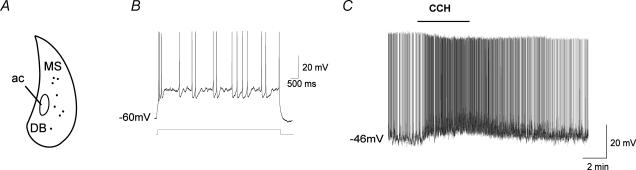

Figure 3. Synchronized intracellular glutamate-mediated bursts and extracellular field potentials in a novel in vitro half-septum preparation.

A, schematic diagram of the recording set up. Field and patch electrodes were gently lowered onto the exposed MS/DB surface of the half-septa, and whole-cell recordings were established using the blind patch technique. The image on the right illustrates the positioning of a recording electrode in the centre of the MS with the anterior commissure (ac) serving as a landmark. The picture was taken at 10 × magnification. B, spontaneous repetitive bursts were recorded in MS/DB neurones (top traces) and were correlated with large field potentials (bottom traces) in the mACSF-infused half-septum. Expanded traces (right, *) show that the extracellular bursts occur synchronously with those in the cell. C, in another experiment, the spontaneous intra- and extracellular bursting activity observed in mACSF (shown here at rapid sweep speed on the left and slow sweep speed on the right) were reversibly blocked by the AMPA receptor antagonist DNQX (20 μm). These results indicate that MS/DB glutamatergic neurones are organized into a network. For this experiment, the tip of the extracellular electrode was placed 200 μm form the recorded neurone.

Whole-cell and field potential recording

Patch pipettes (3–6 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass capillary tubing (Warner Instrument Corp., Hamden, CT, USA) and filled with internal solution containing (mm): potassium gluconate 144, MgCl2 3, EGTA 0.2, Hepes 10, ATP 2 and GTP 0.3; pH 7.2 (285–295 mosmol l−1). Whole-cell recordings in voltage-clamp and current-clamp modes were performed at room temperature using a whole-cell patch-clamp amplifier PC-505 A (Warner Instrument Corp.). The resting membrane potential was measured in current-clamp mode once a stable recording was obtained. Cells were only used for experiment when the resting membrane potential was more negative than –45 mV, spikes overshot 0 mV and the series resistance was less than 30 MΩ. Cells recorded in the various experimental preparations used in this study appeared equally healthy based on these criteria. The presence of a hyperpolarization-activated cation current (Ih) or a depolarizing sag was monitored using hyperpolarizing steps from −60 mV to −95 mV. The firing frequency was estimated using a series of depolarizing steps. The membrane potential (Vm) output signal was filtered on-line (0.1–0.2 kHz) and acquisition speed was set between 2 and 10 kHz in the pClamp 8.0.1 software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Whole-cell recordings in the intact half-septum were performed as noted above for slices except that the whole-cell configuration was established blindly by descending the recording electrode into the tissue (Blanton et al. 1989; Margrie et al. 2002). For this technique to work well, high positive pressure had to be applied to the back of the pipette. Field potentials were recorded conventionally with glass micropipettes (2 MΩ, filled with normal ACSF) using the 100 ×Vm output of an AM-system 3100 (Everett, WA, USA) or a Dagan BVC-700 A (Minneapolis, MN, USA) amplifier equipped with a low-cut filter set at 0.3 Hz. Extracellular recordings were low-pass filtered on-line at 1 kHz and traces shown were additionally filtered off-line for clarity.

Measurement of spontaneous synaptic activity and bursts

MS/DB cells were patched, briefly characterized and held at a hyperpolarized membrane potential (usually −80 or −70 mV) to monitor spontaneous synaptic activity. Slices were perfused with mACSF solution that was Mg2+-free and that contained the pro-convulsant agent 4-AP (50 μm) and the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (10 μm). This combination of solutions was chosen because, neither bicuculline nor 4-AP alone (with or without Mg2+) triggered reproducible bursts in the preparations. Although most recorded cells showed increased spontaneous synaptic activity in this solution, we concentrated our analysis on spontaneous excitatory bursts. A burst was defined as a period of sustained depolarization originating with rapid onset from baseline (−80 mV), remaining above a preset threshold (three times the baseline noise) for 400 ms and having a peak amplitude of 15 mV. These criteria for burst analysis were used mainly to facilitate the comparison of spontaneous synaptic activity between the different conditions. Burst duration was measured as the time during which the membrane potential was above baseline and burst amplitude was measured at the peak of synaptic potentials when possible or just before the first action potential when intense firing prevented adequate measurement (Fig. 1A). We found that holding the membrane at a hyperpolarized potential facilitated measurement of burst amplitude. All bursts were measured from a holding potential of –80 mV for slices and –70 mV for intact half-septum preparation.

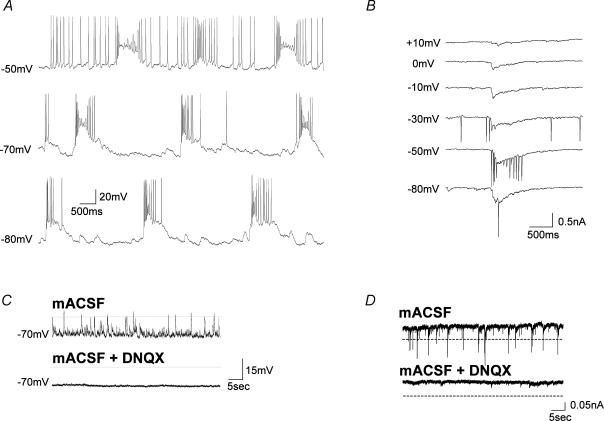

Figure 1. Large spontaneous glutamatergic bursts are observed in neurones from acute MS/DB slices perfused with mACSF (4-AP, bicuculline and Mg2+free).

A, prolonged perfusion (more than 30 min) with mACSF induced spontaneous and sustained bursting discharges in a MS/DB neurone. Example from a cell that was recorded for more than 1 h, 72 min after the start of mACSF perfusion, demonstrating large and long-lasting bursts (mean duration, 1071 ± 64.4 ms; mean amplitude, 35 ± 2.3 mV; n = 19 bursts) at regular intervals. Current-clamping the cell at different membrane potentials did not affect the regularity of bursts, indicating that this activity was not due to intrinsic membrane properties but rather to synaptic input. Note that spontaneous bursts can trigger action potentials from a holding potential of −80 mV. B, large spontaneous inward currents recorded under voltage clamp from the neurone shown in A have an equilibrium potential typical of glutamatergic transmission (> 0 mV). C, for a different neurone, upper and lower traces illustrate current-clamp recordings (duration, 1 min) of mACSF-induced spontaneous activity before and after the addition of DNQX (in this example, bursts did not trigger action potentials from the holding potential of −80 mV). In current-clamp recorded MS/DB neurones, the mACSF-induced bursts were abolished by the AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist DNQX (20 μm, *P < 0.05, paired t test, n = 5). D, in voltage-clamp recordings of the same cells (held at −80 mV), mACSF-induced spontaneous inward currents exceeding a preset threshold (horizontal dashed line shows three times the baseline noise) were also completely abolished by DNQX (**P < 0.01, n = 5).

Immunohistochemistry

Cultured MS/DB slices were fixed for 1 h at room temperature with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde followed by several rinses in PBS. Slices were then treated for 1 h with PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100. Blocking was performed with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA), 5% normal horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h. The slices were incubated overnight at 4°C in the presence of primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer (with BSA diluted to 0.5%). Final dilutions for antibodies were 1 : 1000 for polyclonal rabbit anti-VGLUT2 (Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany), 1 : 2500 for polyclonal guinea-pig anti-VGLUT2, 1 : 2500 for monoclonal mouse IgG2a anti- glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 (GAD67), 1 : 500 for monoclonal mouse IgG1 anti-synaptophysin (Chemicon International; Temecula, CA, USA) and 1 : 1000 for monoclonal mouse anti-choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) kindly provided by Dr L. Descarries (Université de Montréal, Quebec, Canada; Cossette et al. 1993; Chedotal et al. 1994). After extensive washing in PBS, the slices were incubated overnight at 4°C in the same antibody diluent buffer containing the appropriate species-specific fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted 1: 400: Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit or Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-guinea-pig IgG (VGLUT2), Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse IgG2a (GAD67) (Invitrogen), and Cy3 donkey anti-mouse IgG (ChAT and synaptophysin) (Jackson Immunoresearch). Following the final washes in PBS, the slices were briefly rinsed in water then mounted on slides in Vectashield medium (Vector Laboratories) and subsequently examined with a Nikon fluorescence microscope and a Nikon PCM2000 confocal microscope system. Z-series of 16–51 optical sections were scanned and carried out sequentially (for dual labelling) with the 488 nm and 543 nm lines of the laser to reveal Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 568 or Cy3, respectively. Images were acquired either at 0.6 μm, 0.2 μm or 0.14 μm intervals with a 20 ×, 60 × and 100 × objective lens, respectively. Images were adjusted for contrast only using the Simple PCI Program Rev 3.5 (Compix Inc., C-Imaging Systems, Cranberry Township, PA, USA).

Data analysis

All electrophysiological data were analysed using pCLAMP 9.0 sofware (Axon Instruments). To compare bursting activity in MS/DB cells between different conditions, we used 1-min recording episodes. All results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. For statistical analyses we performed paired or unpaired Student's t test (two-tailed) or ANOVA using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Figures were compiled using pCLAMP or Origin (5.0, Microcal Software, Northampton, MA) for plotting electrophysiological data and analyses.

Results

Large spontaneous EPSPs are mediated by AMPA/kainate receptor activation in disinhibited MS/DB slices

In the following experiments, we examined whether glutamatergic neurones within the MS/DB could be activated (Fig. 1) and then further investigated whether glutamatergic synaptic terminals originating from outside this nucleus contributed to the glutamatergic activity (Fig. 2). As an electrical stimulation of afferent fibres would activate both cut glutamatergic synaptic fibres originating from outside and those from glutamatergic neurones within the MS/DB, intrinsic glutamatergic neurones were activated by increasing the overall excitability of the slices. Moreover, we hypothesized that if MS/DB glutamatergic neurones were interconnected, increasing the overall excitability of MS/DB slices would favour the emergence of large and sustained synaptically mediated spontaneous depolarizations reflecting the synchronized discharge of several glutamatergic neurones. In contrast, synaptically mediated glutamate responses originating from cut excitatory afferents or isolated glutamatergic neurones would be small and transient (Barbarosie & Avoli, 1997; Avoli et al. 2002; Dzhala & Staley, 2003). To increase neuronal excitability of MS/DB slices, we used mACSF solution containing 4-AP (50 μm), the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (10 μm), and no Mg2+. MS/DB neurones exhibited only sparse spontaneous synaptic activity in normal ACSF but perfusion of MS/DB slices with the mACSF elicited a gradual increase in spontaneous EPSPs over the first 20 min. Because of the slow development of the spontaneous activity, most experiments were then initiated using slices that had already been perfused in modified ACSF for more than 30 min. We found that such treatment induced large bursting activity in recorded MS/DB neurones. Figure 1A shows an example from a cell demonstrating large and long-lasting bursts occurring at regular intervals of 1–3 s. In 19/62 neurones, spontaneous bursts recorded from a holding potential of −80 mV consisted of sharp-onset prolonged depolarizations (400 ms, 15 mV; see Methods) that often triggered action potential firing (in 13/19 cells with bursts). These bursts had a mean duration of 838.3 ± 70.3 ms (range, 405–2263 ms), a mean amplitude of 22 ± 1.8 mV, and a mean number of bursts per min of 5.1 ± 1.05. Although bursts occurring at relatively regular intervals (such as in Fig. 1A) were observed in rare occasions, most bursting cells did not display any apparent pattern in acute slices. The spontaneous bursts of MS/DB neurones were not dependent on intrinsic membrane properties, rather they were synaptically mediated because: (1) their frequency and duration did not change at different levels of membrane potentials (Fig. 1A); (2) they were associated with the production of large inward currents (EPSCs) in voltage clamp (Fig. 1B); and (3) burst-associated EPSCs had a reversal potential near 0 mV (n = 6), a value typical of AMPA receptor-dependent EPSPs in the MS/DB (Schneggenburger et al. 1992; Armstrong & MacVicar, 2001). To verify that spontaneous bursts were mediated by presynaptic release of glutamate, we bath applied the selective AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist DNQX (20 μm). In 5 out of 5 cells, the mACSF-induced burst activity and burst-associated currents were completely abolished by DNQX (Fig. 1C and D). In one other cell (not shown), the burst activity persisted 15 min after DNQX perfusion (although the duration of bursts was dramatically reduced) but was stopped in a reversible manner after addition of the NMDA receptor antagonist d-aminophosphonovalerate (APV). Taken together, these results suggest that the spontaneous bursts are mediated by the release of glutamate and mostly involve postsynaptic AMPA receptors, and to a lesser extent NMDA receptors.

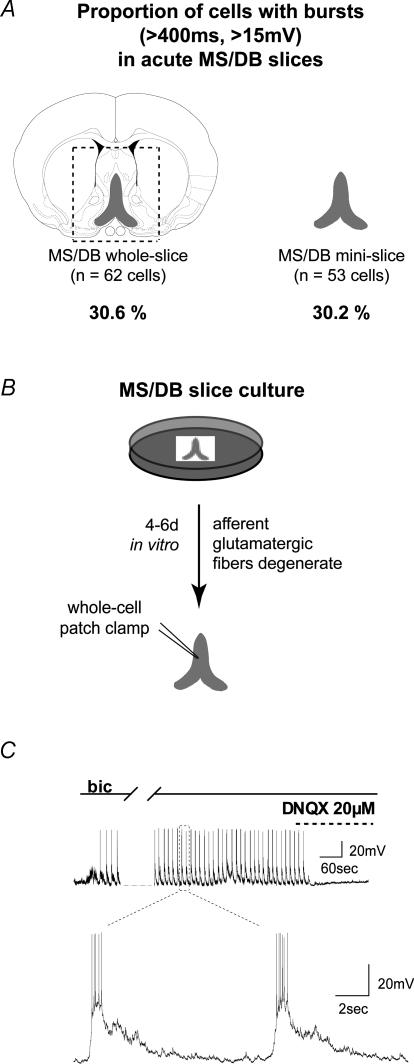

Figure 2. AMPA receptor-mediated bursts are prominent in MS/DB acute and organotypic mini-slices containing only the MS/DB.

A, narrowing the slice preparation to the MS/DB region by surgically removing the neighbouring lateral septum did not reduce the proportion of cells showing large spontaneous EPSPs (measured from a holding of –80 mV). The contours of the complete (regular) slice are outlined (dashed line) and include the lateral septum and portions of the striatum. B, organotypic slices containing the MS/DB region alone were cultured for 4– 6 days in vitro to allow afferent (extra-septal) glutamatergic terminals to degenerate. C, disinhibition of the organotypic slice with bicuculline rapidly (in less than 5 min) induced large spontaneous and repetitive bursting discharges that were abolished by DNQX (20 μm, n = 6). The bottom panel shows an expanded view of the spontaneous bursts at a faster sweep speed.

Glutamate-mediated bursts are generated by neurones within the MS/DB and not by external glutamatergic afferents

We investigated whether neurones from the lateral septum, a region suspected to contain glutamatergic projecting neurones (Kiss et al. 2002; Kocsis et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2003; Hajszan et al. 2004), might have contributed to the synaptically mediated glutamate responses that were observed in the MS/DB. We therefore challenged slices with mACSF that contained only the MS/DB (mini-slices; see Methods and Fig. 2A) without the lateral septum. We found that, in comparison to regular lateral septum-containing slices, a similar proportion of neurones from mini-slices responded to the mACSF with spontaneous burst (16/53 cells, 30.2%). Moreover, these bursts were also comparable in terms of duration (760 ± 68.3 ms), amplitude (21.1 ± 1.5 mV) and frequency (5.6 ± 1.2 bursts min−1) (P > 0.05; unpaired t test) and they were similarly blocked by DNQX (data not shown). This indicates that glutamatergic neurones within the MS/DB are sufficient to sustain this bursting and that the lateral septum region does not further contribute to the generation of spontaneous glutamatergic bursts in these experimental conditions.

We next examined whether the glutamatergic inputs that are known to originate from outside the septum (Jaskiw et al. 1991; Leranth & Kiss, 1996; Leranth et al. 1999; Kiss et al. 2000; Bokor et al. 2002) contributed to the spontaneous EPSPs observed in the acute slices challenged with the mACSF. Excitatory terminals remaining in the slice can potentially sustain repetitive synchronous discharge when activated with 4-AP (Strowbridge, 1999). We therefore eliminated glutamatergic synaptic afferents from outside by using an organotypic slice culture preparation of the MS/DB (Fig. 2B). In organotypic slices, all extrinsic input degenerates over the first few days in culture leaving only synaptic contacts from neurones within the slice (Buchs et al. 1993; Gahwiler et al. 1997). Similar to the neurones recorded in acute slices, those recorded from organotypic slices displayed healthy membrane characteristics in normal ACSF. Interestingly, the addition of bicuculline alone in MS/DB organotypic slices induced large spontaneous excitatory bursts within the first 5 min of perfusion (Fig. 2C) in 7 out of 8 recorded neurones. The bursts had an average duration of 5034 ± 1035 ms (range, 1904–8837 ms), an average amplitude of 25.8 ± 2.9 mV and the mean number of burst per min was 4.0 ± 0.9. These bursts were rapidly blocked (n = 6/6 neurones) by superfusion of the AMPA receptor antagonist DNQX (20 μm) (Fig. 2C). Taken together these results demonstrate that the excitatory bursts observed in disinhibited MS/DB slices are generated by local glutamatergic neurones residing within the MS/DB while neurones of the lateral septum or excitatory afferent fibres from outside the septum do not contribute to these responses.

Network activity of MS/DB glutamatergic neurones in the intact half-septum in vitro

Excitatory interconnections between glutamatergic neurones form the basis for the generation and synchronization of some network rhythms in regions such as the CA3 of the hippocampus (Traub et al. 1999). Interestingly, we have observed that a small proportion of neurones from mACSF-bathed acute MS/DB slices showed very slow and large repetitive activity (as in Fig. 1A), suggesting that local glutamatergic neurones could be organized into a network of synchronously discharging neurones. We hypothesized that this putative network activity occurred in only a few slices because the synaptic connections necessary for such activity were damaged by the slicing procedure and that a more intact preparation would provide a more prominent and functional network. We therefore examined whether glutamate-mediated slow repetitive activity would be more frequent and robust when recorded in an intact half-septum preparation in vitro (see Methods and Fig. 3A). Using the whole-cell blind patch-clamp technique to record the activity of single cells in mACSF-perfused half-septum, we observed large amplitude, regular and sustained bursting activity in a significantly larger proportion of recorded neurones (13 of 26 cells, 50%) in this preparation than in the acute slices. The duration of bursts was also significantly larger (2352 ± 383.4 ms; range, 423–8097 ms; P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA; whole-slice, mini-slice, intact half-septum), and in contrast to acute slices, bursts occurred with a stable repetitive pattern (i.e. at regular intervals, similar to Fig. 3B and C) in most cells recorded from in the intact half-septa. Overall, the proportion of preparations that were recruited into burst activity in mACSF was larger for the half-septum experiments than for acute slices (Table 1). As these results suggested that the integrity of the glutamatergic network was better preserved in this type of preparation, we went on to perform extracellular recordings that might pick up the activity of simultaneously discharging neurones.

Table 1.

Proportion of MS/DB slices and intact preparations where repetitive burst activity was observed

| Acute MS/DB slices | MS/DB cultured mini-slice | Intact half-septum preparation |

|---|---|---|

| n = 60 (in mACSF) | n = 8 (in ACSF + bicuculline) | n = 55 (in mACSF) |

| 38% | 75% | 56% |

Summary of burst activity for the different preparations used in this study. Note that for the intact half-septum, all the different experiments were pooled including those that were done with patch or field recordings alone and in parallel.

Our extracellular recordings detected clear long-duration field potentials in 54.5% of intact half-septa tested with mACSF. The mean amplitude, duration and frequency of MS/DB field potentials were 42.5 ± 19.9 μV, 2394 ± 1073 ms and 5.2 ± 2.5 bursts min−1 (n = 13), respectively. The presence of such extracellular bursts suggested the presence of an important population of synchronously discharging neurones. Consistent with this possibility, in three of the half-septa where extracellular bursts were recorded, simultaneous whole-cell recordings (n = 4 cells) revealed that intracellular bursts were synchronous with extracellular field potentials (Fig. 3B and C). These synchronized activities were mediated primarily by AMPA receptors because in all cases they were reversibly blocked by the antagonist DNQX (20 μm, Fig. 3C; whole-cell, n = 6/6, P < 0.001; extracellular, n = 6/6, P < 0.01 paired t test). We also investigated whether cholinergic neurones contributed to the repetitive bursting by perfusing the muscarinic antagonist atropine. We found that atropine (10 μm) applied for 10 min did not affect the extracellular synchronous discharges nor the simultaneously recorded intracellular bursting activity (n = 3) suggesting that acetylcholine does not contribute to this activity. Our results thus indicate that the spontaneous bursts recorded from MS/DB neurones in mACSF may in fact reflect a broad synchronization of glutamatergic network activity through interconnections.

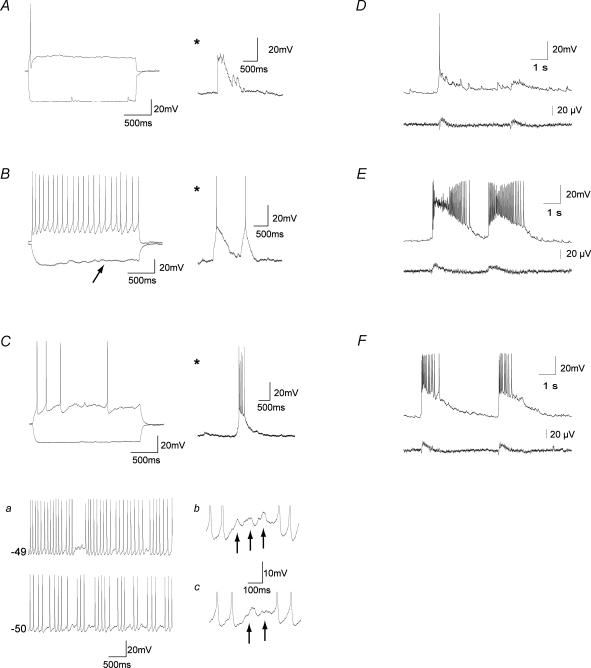

Glutamatergic neurones of the MS/DB activate cholinergic and non-cholinergic neurones

It remains to be shown that cholinergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurones of the MS/DB receive AMPA/kainate receptor-mediated synaptic input form local glutamatergic neurones of the MS/DB. Using electrophysiological characterization of MS/DB neurones, we first investigated whether the different neuronal types of the MS/DB received synaptic inputs from local glutamatergic neurones. We used previously reported electrophysiological characteristics to identify MS/DB neurones, namely the lack of expression of an Ih and a slow firing frequency in cholinergic neurones versus larger Ih and faster firing rates in GABAergic neurones (Griffith, 1988; Gorelova & Reiner, 1996; Serafin et al. 1996; Jones et al. 1999; Sotty et al. 2003). We also investigated whether cluster-firing neurones, previously suggested to be glutamatergic in nature (Sotty et al. 2003), received glutamatergic input. Our results show that slow-firing neurones lacking Ih (Fig. 4A; putative cholinergic), fast-firing neurones with an important Ih (Fig. 4B; putative GABAergic), and neurones that displayed cluster-firing (Fig. 4C; putative glutamatergic) all received glutamatergic-mediated EPSPs and bursts from the local glutamatergic network. Table 2 summarizes the electrophysiological properties of MS/DB cells showing glutamatergic input in mACSF. Of 29 fully characterized neurones that were that were recorded from acute MS/DB slices, most had the characteristics of fast-firing cells, eight were slow firing, and five cells were of the cluster-firing type.

Figure 4. Electrophysiologically identified MS/DB neurones receive glutamatergic input in mACSF-perfused MS/DB slices and display synchronized glutamatergic network activity in the intact half-septum preparation.

A–C, neurones challenged with depolarizing and hyperpolarizing currents (left traces) to identify cell types and examples of burst observed in these are shown (*). Large excitatory bursts (*) were observed in slow-firing (putative cholinergic) neurones showing no Ih current, strong spike frequency accommodation and a large AHP (A), fast-firing (putative GABAergic) neurones showing prominent Ih current (arrow), nominal accommodation and small AHP (B) and cluster-firing (putative glutamatergic) neurones of the MS/DB (C). C, examples of cluster-firing (a) and subthreshold oscillations (b and c) showing increased frequency at depolarized membrane potentials are shown on the right for each trace depicted in a. D–F, representative examples of repetitive bursts (upper traces) and synchronized field potentials (lower traces) in slow- (D), fast- (E) and cluster-firing (F) neurones.

Table 2.

Firing characteristics of electrophysiologically identified MS/DB neurones receiving local glutamatergic input

| Slow firing | Fast firing | Cluster firing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute MS/DB slice | n = 8 (3) | n = 12 (6) | n = 5 (3) |

| Ih amplitude (mV) | 1.0 ± 0.3* | 7.6 ± 0.7‡ | 1.0 ± 0.9 |

| AHP duration (ms) | 276 ± 40.6*† | 99.8 ± 12.3‡ | 181 ± 10.2 |

| AP at 5th step from threshold | 7.75 ± 1.51* | 26.4 ± 2.79‡ | 10.0 ± 2.05 |

| Intact half-septum preparation | n = 7 | n = 6 | n = 4 |

| Ih amplitude (mV) | 1.8 ± 0.4* | 5 ± 1‡ | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| AHP duration (ms) | 381 ± 66.3* | 63 ± 11.7‡ | 296 ± 40.8 |

| AP at 5th step from threshold | 8.6 ± 1.4 | 21.7 ± 1.4 | 9.5 ± 2.8 |

A series of depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current pulses (2–8 s, 0–200 pA, steps of 10 pA) administered from a holding of −60 mV were used to electrophysiologically identify MS/DB neurones receiving local glutamatergic input. Because mACSF-induced burst activity only developed slowly in slices and fully bursting cells were otherwise difficult to characterize due to their unstable membrane potential, we extended the analysis to all cells showing increased EPSP activity in mACSF. In the intact half-septum preparation where bursts appear more rapidly, fully bursting cells were first characterized in normal ACSF. Ih amplitude was determined by comparing the difference in voltage at the start and at the end of 2-s pulses to −95 mV. AHP duration was measured for the first action potential evoked at threshold and an indicator of firing properties was obtained by counting the number of spikes elicited by 2-s current pulses 50 pA greater than the threshold current. Significant differences (P < 0.05, Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test) are indicated:

slow-firing versus fast-firing neurones;

slow-firing versus cluster-firing neurones;

fast-firing versus cluster-firing neurones. For slices, the numbers in parentheses indicate the proportion of these identified neurones that developed mACSF-induced AMPA-mediated bursts (400 ms, 15 mV). Consistently with previous reports (Griffith et al. 1988; Gorelova & Reiner, 1996; Serafin et al. 1996; Jones et al. 1999; Sotty et al. 2003) an important portion of fast-firing neurones showed intrinsic bursting properties. AHP, after-hyperpolarization; AP, action potential number.

Using the intact half-septum preparation, we further explored whether the three electrophysiologically identified classes of MS/DB neurones displayed bursting responses concomitant with the extracellular field recordings. We found that all neurone classes had bursts that were always synchronized with extracellular fields (Fig. 4D–F). However, the intracellular bursts measured in the putative cholinergic neurones were somewhat smaller than those in the other classes even though the extracellular fields appeared to be relatively large in amplitude (Fig. 4D and Table 3). This suggests that slow-firing (putative) cholinergic neurones may participate less that the other cell types in the glutamatergic-driven network activity.

Table 3.

Properties of simultaneously recorded intracellular and extracellular bursts for electrophysiologically characterized MS/DB neurones from the intact half-septum preparation

| Intracellular bursts | Extracellular bursts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude (mV) | Duration (ms) | Amplitude (μV) | Duration (ms) | |

| Slow firing (n = 5) | 12.3 ± 2.2 | 4596 ± 2568 | 25.34 ± 5.908 | 3427 ± 1391 |

| Fast firing (n = 4) | 28.6 ± 6.7 | 4285 ± 1408 | 16.50 ± 3.941 | 3146 ± 1062 |

| Cluster firing (n = 2) | 29.3 ± 0.4 | 2901 ± 1266 | 22.63 ± 1.869 | 2104 ± 445.7 |

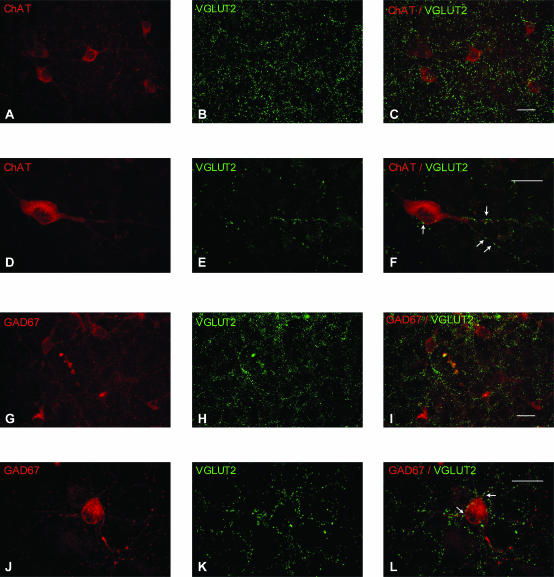

To complement these electrophysiological results suggesting that putative cholinergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurones receive glutamate-mediated responses from local neurones, we examined whether VGLUT2-positive puncta were found adjacent to cholinergic neurones labelled for choline ChAT and GABAergic neurones labelled for the GABA-synthesizing enzyme GAD67 in organotypic mini-slices of the MS/DB (Fig. 5). Using confocal microscopy, VGLUT2-immunoreactive puncta were seen in close apposition (with no discernible gap) to the cell body and dendrites of both, ChAT- and GAD67-positive neurones (Fig. 5A–L). These results support the electrophysiological evidence that cholinergic and GABAergic neurones receive glutamatergic synapses from glutamate neurones within the MS/DB.

Figure 5. Immunohistochemical evidence for locally originating VGLUT2-positive terminals on MS/DB cholinergic and GABAergic neurones in organotypic slices.

A–F, representative examples showing (A–C) numerous VGLUT2-positive puncta (green) in a region containing many ChAT-positive neurones (red) and (D–F) VGLUT2-positive terminals (green; arrows) in contact with the soma and dendrites of a ChAT-positive neurone (red). Single-channel confocal immunofluorescence for ChAT (A and D), VGLUT2 (B and E) and merged images (C and F). G–L, representative examples showing (G–I) numerous VGLUT2-positive puncta (green) in a region containing many GAD67-positive neurones (red) and (J–L) VGLUT2-positive terminals (green; arrows) in contact with the soma and dendrites of a GAD67-positive neurone (red). Single-channel confocal immunofluorescence for GAD67 (G and J), VGLUT2 (H and K) and merged images (I and L). Note that although the putative glutamatergic synapses seem to be relatively scattered in the tissue, a clear correspondence of VGLUT2 distribution with the dendritic pattern of the labelled neurones is seen in the preceding examples. Scale bars, 20 μm.

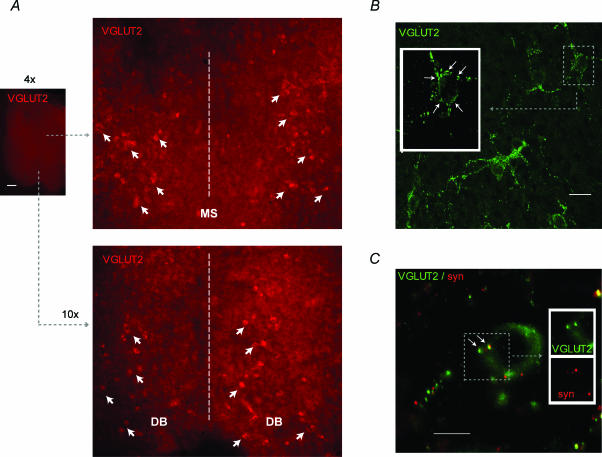

We next determined whether glutamatergic neurones could be detected in organotypic MS/DB slices and whether they also received VGLUT2-positive puncta. As VGLUT2 is essentially a synaptic marker and is usually not observed in the cell body or dendrites, the axonal-transport blocker colchicine was used to enhance the accumulation and visualization of VGLUT2 in the perikarya. A large number of VGLUT2-positive soma and terminals were found in organotypic slices of the MS/DB (Fig. 6A). VGLUT2-positive cell bodies were distributed ventrally along the DB, laterally lining the border of the MS, and caudally often forming elongated clusters (Fig. 6A and B), with relatively few cell bodies close to the midline. Such a distribution was very similar to that reported by Hajszan et al. (2004). Additionally, we observed using confocal microscopy that VGLUT2-positive puncta (Fig. 6B and C) were frequently found in proximity to the soma of VGLUT2-positive neurones. We found that some of these VGLUT2-positive puncta were double-labelled for the synaptic marker synaptophysin (Fig. 6C) confirming that they were axonal varicosities. It is important to note that these VGLUT2-positive terminals could only originate from local neurones in the MS/DB because the cultured slices (containing only the MS/DB area) were devoid of truncated glutamatergic synaptic terminals from extrinsic neurones. We also noted that some of the VGLUT2-positive puncta were not co-labelled with the synaptic marker synaptophysin when slices were treated with colchicine. We suspect that some of the VGLUT2-positive boutons were not co-labelled with synaptophysin because they could have been labelled in the axon while they were prevented from being transported by colchicine. Although hard evidence that VGLUT2-positive synaptic terminals contact cholinergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurones would require electron microscopy, the present immunohistochemical results further support the electrophysiological evidence that the three major groups of MS/DB neurones receive synaptic input from local glutamatergic neurones and that glutamatergic neurones are interconnected in the MS/DB.

Figure 6. Fluorescence microscopy (A) and confocal (B and C) photomicrographs of VGLUT2-positive neurones and terminals in colchicine-treated organotypic MS/DB slices.

A, VGLUT2-immunostaining following a short (1-h) exposure to colchicine reveals the presence of numerous Alexa Fluor 568-positive (glutamatergic) cell bodies (red; arrows) near the lateral borders of the MS and throughout the diagonal bands on the ventral side of the slice (dotted line, midline). A similar distribution was seen in eight other slices. B, Alexa Fluor 488-labelled VGLUT2 puncta and neurones (green). The VGLUT2-positive neurones were often organized in elongated clusters as illustrated here and many seemed surrounded with VGLUT2-positive terminals. Inset, higher magnification from a few optical sections of the area outlined in B illustrating putative VGLUT2-positive teminals (arrows) lining the surface of a VGLUT2-positive soma. C, Alexa Fluor 488-labelled VGLUT2 neurone (green) and colocalization of VGLUT2-positive puncta (green) with Cy3-labelled synaptophysin puncta (red). Inset, higher magnification of area outlined in C illustrating VGLUT2/synaptophysin-postive terminals (arrows) contacting the VGLUT2-positive neurone. Number of stacked optical sections for B and C are 16 and 6, respectively. Scale bars: 500 μm in A; 20 μm in B; and 10 μm in C.

Selective activation of muscarinic receptors elicits glutamatergic EPSPs at theta frequency in MS/DB neurones of the intact septum

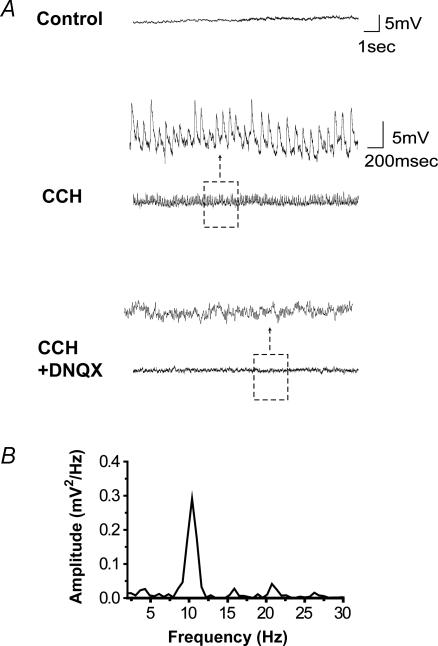

Acetylcholine (ACh) originating from the septum plays an important role in learning and memory (Lee et al. 1994; Leung et al. 2003). It is well known that cholinergic muscarinic receptor activation in the MS/DB in vivo can positively affect memory and increase hippocampal theta (Monmaur & Breton, 1991; Lawson & Bland, 1993; Oddie et al. 1994; Givens & Olton, 1994, 1995; Markowska et al. 1995; Frick et al. 1996). Therefore, we investigated whether local glutamatergic neurones were involved in the actions of ACh in the MS/DB by examining if MS/DB glutamatergic neurones of the intact half-septum preparation could be activated by muscarinic receptor stimulation. Although occasional EPSPs were observed in a large proportion of the 50 neurones recorded in normal ACSF, a striking increase in spontaneous EPSPs was observed in 12 of these cells following perfusion of the preparation with carbachol (30 μm) (Fig. 7A, middle trace; 1543 ± 300% increase in the number of EPSPs per 30 s; ***P < 0.005, paired t test). Carbachol-induced EPSPs were completely abolished by the addition of the glutamatergic AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist DNQX (Fig. 7A, bottom trace; 6 out of 6 experiments; *P < 0.05, paired t test). Interestingly, we found that in a portion of the carbachol-responsive cells (n = 4/12 cells), carbachol elicited continuous or intermittent bursts of EPSPs at theta frequency (6–10 Hz range) appearing as significant peaks in the power spectra (Fig. 7A, middle trace and B); the average peak frequency for the four cells was 8.9 ± 1.6 Hz and the mean power peak amplitude was 0.35 ± 0.24 (range, 0.09–0.64). Carbachol-induced rhythmic and non-rhythmic EPSPs elicited in the presence of bicuculline (n = 2/2 cells; data not shown) were comparable to those in control suggesting that they were not reversed IPSPs. These results suggest that carbachol can induce the collective activity of MS/DB glutamatergic neurones and generate EPSPs at theta frequencies.

Figure 7. Selective activation of muscarinic receptors elicits large and rhythmic EPSPs in MS/DB neurones in the in vitro half-septum preparation.

A, in control (ACSF) solution, no apparent synaptic activity is seen in a whole-cell recorded neurone of the half-septum preparation (top trace; membrane potential, −55 mV). However, bath application of the cholinergic agonist carbachol (CCH, 30 μm) induces continuous and rhythmic EPSPs (middle trace), which are abolished by the addition of the glutamatergic AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist DNQX (20 μm, bottom trace). B, power spectrum of carbachol-induced synaptic activity obtained over a 2-s recording from the neurone shown in A using a fast Fourier transform algorithm (pCLAMP 9.0). Note the distinct peak at 10 Hz.

To provide more direct evidence that glutamatergic neurones of the MS/DB can be activated by carbachol, we recorded from cluster-firing neurones (previously shown to be putative MS/DB glutamate neurones; Sotty et al. 2003) in the intact half-septum preparation (Fig. 8A and B; in this series of experiments, 42 neurones were recorded and 11 were identified as clusters). In 8 out of 8 cluster-firing cells tested, carbachol elicited a depolarization of the resting membrane potential (mean increase, 6 ± 1 mV; **P < 0.005, paired t test). Of more importance, the spontaneous firing frequency of cluster-type neurones was also increased to 293 ± 135% of control in the presence of carbachol (Fig. 8C; *P < 0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank test) and this effect was reversible. These results thus indicate that putative glutamate cluster-firing neurones are excited by muscarinic stimulation.

Figure 8. Distribution of the recorded cluster-firing (putative glutamatergic) neurones in the intact half-septum preparation and depolarizing effect of carbachol.

A, schematic diagram showing the approximate location of cluster-firing cells recorded from the MS/DB area in 12 preparations. B, current-clamp recording showing the response of a cluster-firing MS/DB neurone to injection of a depolarizing current pulse (8-s square pulse) applied from a membrane potential of −60 mV. Depolarization elicited characteristic cluster firing and subthreshold oscillations between clusters. C, in the same cell, bath application of carbachol (30 μm) caused a 7 mV depolarization from resting potential and dramatically increased the firing frequency (from 50 to a 100 action potentials min−1) in a reversible manner.

Discussion

It has generally been accepted in the last two decades that the MS/DB is made up primarily of cholinergic and GABAergic cells. Here, we present compelling novel evidence that MS/DB glutamate neurones can provide powerful glutamatergic input locally. This conclusion is based on a number of experimental results obtained using acute MS/DB slices, organotypic MS/DB cultured slices or an intact half-septum preparation in vitro. First, depolarizing glutamatergic neurones with extracellular solutions that promoted increases in excitability in MS/DB slices initiated dramatic long-lasting increases in repetitive glutamate-mediated bursts. Second, these responses were generated from glutamatergic neurones within the MS/DB and not from glutamatergic extrinsic fibres as glutamate-mediated bursts remained prominent when generated in trimmed slices leaving only the MS/DB without the lateral septum, an area that could potentially send excitatory projections to the MS/DB (Staiger & Nurnberger, 1991; Risold & Swanson, 1997; Kiss et al. 2002; Kocsis et al. 2003; Lin et al. 2003; Hajszan et al. 2004). Finally, powerful glutamate-mediated bursts were also prominent when recorded in trimmed MS/DB organotypic slices. The experiments with organotypic MS/DB slices provide strong evidence that glutamate-mediated bursts were generated exclusively from within the MS/DB as all truncated synaptic terminals originating from outside the area degenerate rapidly and are absent at the time of recordings in these cultures (Buchs et al. 1993; Gahwiler et al. 1997). Taken together, these experiments provide new evidence that functional glutamatergic neurones are present in the MS/DB and can drive other neurones locally.

One important conclusion from our study is that glutamatergic neurones within the MS/DB generated bursting activity on postsynaptic neurones that was blocked predominantly by the AMPA/kainate antagonist DNQX, and to a much lesser extent, AP-V. Such DNQX-sensitive responses were observed in acute regular slices containing the MS/DB, in trimmed MS/DB slices, in trimmed MS/DB organotypic slices and in the intact half-septum preparation. Similarly, the carbachol-induced rhythmic EPSPs in the MS/DB were also sensitive to this agent (see below). We suggest that MS/DB glutamatergic neurones activate predominantly AMPA, and to a lesser extent NMDA receptors, but probably not kainate receptors. Although DNQX is also known to block kainate receptors, previous studies have clearly shown that electrically activated synaptic responses in the MS/DB (Armstrong & Macvicar, 2001) or currents elicited by exogenous application of glutamate agonists on a variety of MS/DB neurones (Jasek & Griffith, 1998; Frye & Fincher, 2000; Hsiao & Frye, 2003) are generated solely by AMPA and NMDA receptors. The result of predominant activation of AMPA receptors by local MS/DB glutamatergic neurones is interesting in light of the evidence that cholinergic and non-cholinergic MS/DB neurones are known to express at least three types of postsynaptic glutamate receptors; that is, AMPA, NMDA and metabotropic type receptors (Schneggenburger et al. 1992, 1993a, b; Page & Everitt, 1995; Jasek & Griffith, 1998; Armstrong & MacVicar, 2001). This indicates that connections from local glutamatergic neurones activate mostly AMPA receptors (and to a lesser extent NMDA receptors), and may suggest that the other glutamate receptors are activated by glutamatergic populations located outside the MS/DB area. Recent evidence from Wu et al. (2003) does support this contention. They showed that nicotine agonists activated a glutamatergic population which induced a metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated slow depolarization in MS/DB GABA-type neurones in regular acute MS/DB slices. However, the neurones activating the metabotropic-mediated responses were mostly localized outside the MS/DB because physically excluding the lateral septum from the MS/DB reduced the number of nicotinic responding GABAergic neurones from 90 to 40%. As other regions outside the MS/DB such as the supramammilary area (Leranth & Kiss, 1996; Kiss et al. 2000), the entorhinal cortex (Leranth et al. 1999), the frontal cortex (Jaskiw et al. 1991) and nucleus reuniens thalami (Bokor et al. 2002) may also provide important glutamatergic input, it will be important to determine what type of glutamate receptors are activated by these afferents to drive MS/DB neurones. Interestingly, a recent study using MS/DB slices has shown that activation of kainate receptors can synchronize MS/DB neurones at theta frequency (Garner et al. 2005). Therefore, although kainate receptors may not have a significant role postsynaptically in the MS/DB, their activation presynaptically could modulate neurotransmitter release and promote increased synchronization in a manner that is often observed in other brain regions such as the hippocampus (Huettner, 2003).

AMPA receptor-mediated network activity in the whole MS/DB preparation

A particularly striking result from the present study was that the glutamatergic neurones of the MS/DB are organized within a synaptically connected network of excitatory neurones. This conclusion stems from a number of observations. First, the AMPA-mediated bursts (or the voltage-clamped inward current) observed in a large portion of MS/DB neurones from acute slices were probably mediated by many synchronously discharging glutamatergic neurones because these events were sometimes in excess of 700 pA, an unlikely size if they were mediated by only one presynaptic neurone. Second, it was found that a greater number of neurones recorded in the disinhibited intact septum preparation displayed large repetitive AMPA-receptor-mediated bursts in comparison to those recorded in acute slices. This probably indicates that a greater number of neurones are recruited in the intact septum preparation which has greater network integrity compared to acute slices. Third, the bursting activity of neurones in the intact half-septum was also recorded extracellularly as long-duration field potentials, indicating that bursts were probably generated by synchronized discharges in many neurones. Accordingly, simultaneous recordings of neurones and extracellular fields from the intact septum preparation revealed that slow and large repetitive bursts were generated synchronously within the MS/DB, even when the extracellular and patch electrode were positioned several hundred micrometres away from each other. This suggested that the bursts could propagate throughout the glutamatergic network. It is interesting that cholinergic muscarinic receptors did not participate in the synchronous discharge as atropine did not affect these responses. This suggests that even though cholinergic neurones are probably activated by the 4-AP/bicuculline solution (slow-firing neurones thought to be cholinergic were often observed to fire bursts of action potentials in this solution), acetylcholine released from local axon collaterals may not contribute significantly to this type of rapid glutamatergic network activity in the MS/DB. However, it remains to be tested whether the synchronously activated MS/DB cholinergic neurones could contribute to the spontaneous burst/network activity through the activation of extrasynaptic nicotinic receptors in the MS/DB (Henderson et al. 2005).

It should be emphasized here that although the burst firing observed in this study was elicited under non-physiological conditions and is therefore unlikely to reflect any mechanism of MS/DB activity occurring in vivo, it is nonetheless indicative of the presence of a local excitatory network of glutamatergic cells in the MS/DB. Thus, the repetitive synchronous discharge activity observed in the disinhibited MS/DB is highly reminiscent of periodic burst discharges that can be recorded in vitro under similar experimental conditions from various brain structures containing an important number of glutamatergic neurones such as the cerebral cortex (Sanchez-Vives & McCormick, 2000), the brain stem (Koshiya & Smith, 1999) and the CA3 area of the hippocampus (Muller & Misgeld, 1991; Traub & Miles, 1991). Similarities between the bursting observed in the CA3 area and in the septum during disinhibition include large-amplitude, regular and sustained bursts with relatively long-lasting silent periods between them (Staley et al. 1998) and the primary requirement for AMPA receptors (Avoli et al. 1993; Traub et al. 1995). In the CA3, the repetitive bursting activity is due to propagating discharges through relatively extensive recurrent/reciprocal excitatory connections between CA3 pyramidal neurones (Li et al. 1994), driving the entire population into synchronized oscillatory activity (Traub & Wong, 1982; Miles & Wong, 1983, 1986; Traub & Miles, 1991). Of interest, our immunohistochemical data also suggested that glutamatergic neurones are part of an interconnected network as we observed that a significant number of VGLUT2-positive MS/DB neurones appeared to receive VGLUT2/synaptophysin-positive terminals that originated from local neurones in organotypic slices. Therefore, our immunohistochemical data together with the high occurrence of large repetitive glutamatergic bursts are strong evidence that glutamatergic neurones of the MS/DB are connected. Finally, it should be noted that the repetitive glutamatergic bursting activity appeared more prominent in organotypic than in acute slices and necessitated less disinhibition (only bicuculline was needed instead of combined 4-AP and bicuculline in the acute preparations). This may be due to an increase, or reorganization, of glutamatergic synaptic terminals in the MS/DB culture preparation that resulted in an enhancement of the excitation and of synchronous discharge.

Glutamatergic neurones in the MS/DB not only made connections together but also to cholinergic and GABAergic neurones. AMPA receptor-mediated EPSPs and bursts were frequently recorded in putative cholinergic and GABAergic neurones identified by their electrophysiological characteristics. Indeed, glutamatergic excitation was present in slow-firing neurones that lack an Ih, and in fast/burst-firing neurones that had a prominent Ih, which are considered to be key features distinguishing cholinergic and GABAergic neurones (Griffith & Matthews, 1986; Markram & Segal, 1990; Gorelova & Reiner, 1996; Sotty et al. 2003). Our immunohistochemistry data were also in agreement with this as VGLUT2-positive puncta were seen in close vicinity of the soma and dendrites of ChAT-positive and GAD67-positive neurones in the organotypic MS/DB mini-slices. These experiments thus further suggest that glutamatergic neurones within the MS/DB make synapses on cholinergic and GABAergic neurones. In a previous study Hajszan et al. (2004) found that VGLUT2-positive puncta can be localized close to neurones immunoreactive to parvalbumin, a calcium-binding protein found in a subset of GABAergic neurones, in the under- and over-cut septum in vivo (although the possibility was not excluded that some VGLUT2 terminals may have originated from the lateral septum (LS). Our results extend these observations by showing that VGLUT2-positive puncta from MS/DB glutamatergic neurones are likely to be present on GAD67-positive GABAergic neurones. Numerous VGLUT2-positive synapses were recently shown to make contact with cholinergic neurones in the MS/DB, but unlike in our study, the origin of the VGLUT2 puncta was not determined (Wu et al. 2004). These results suggest that local connections from glutamatergic neurones may be important to the output of cholinergic and GABAergic neurones (Fig. 9).

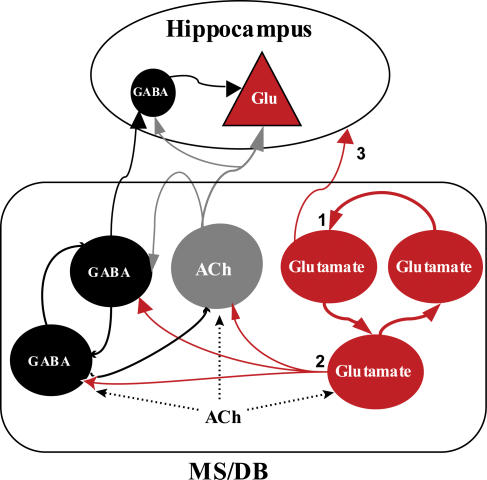

Figure 9. Simplified model of interactions between MS/DB neurones and hippocampus.

In this model, glutamatergic neurones are part of a network (1) and can activate (2) GABAergic and cholinergic neurones mainly through AMPA-type receptors. Some glutamatergic neurones (Sotty et al. 2003) may be septohippocampal-projecting neurones (3). Acetylcholine activates GABAergic, cholinergic and glutamatergic neurones of the MS/DB through muscarinic receptors.

It remains to be determined which type of neurone (slow, fast or cluster firing) releases glutamate locally in the MS/DB. The most likely neuronal cell type in the MS/DB is the slow/cluster-firing neurones we have recently described using single-cell RT-PCR that contains exclusively VGLUT1 and/or VGLUT2 transcripts (Sotty et al. 2003). It is interesting that these neurones were also shown to send projections to the hippocampus (Sotty et al. 2003). Therefore, it may be possible that some of these VGLUT-positive neurones can make local connections within the MS/DB and also send projections to the hippocampus. Alternatively, an important number of fast-firing GAD- (GABA) and slow-firing ChAT-positive (cholinergic) neurones also expressed VGLUT transcripts suggesting that glutamate may also be co-released with other transmitters in the MS/DB (Sotty et al. 2003). Paired recordings from neurones in the MS/DB in combination with pharmacology may help address this issue.

MS/DB glutamatergic neurones can generate EPSPs at theta frequency

The role of ACh in the MS/DB has been shown to be very important in hippocampal theta oscillation, and in learning and memory. The blockade of muscarinic receptors in the MS/DB in vivo can impair learning and disrupt hippocampal theta rhythm (Stewart & Fox, 1990; Givens & Olton, 1995), whereas injecting muscarinic agonists into the MS/DB results in continuous theta field activity (Lawson & Bland, 1993) and may improve memory (Markowska et al. 1995; Frick et al. 1996). Recent reports suggested that the role of ACh in memory may be a result of the activation of GABAergic neurones (Alreja et al. 2000) and/or cholinergic neurones (Henderson et al. 2005) in the MS/DB. Here we provide evidence that in addition, ACh can modulate MS/DB glutamatergic neurones because muscarinic agonist application into the whole septum elicited AMPA-receptor mediated EPSPs at theta frequency (6–10 Hz). Consistent with the idea that muscarinic stimulation activates the glutamatergic neurones in the MS/DB, we also show that carbachol can depolarize and increase the firing frequency of cluster-firing neurones in the intact half-septum. Taken together, these results suggest that muscarinic-induced hippocampal theta generation may be due to the combined activation of GABAergic, cholinergic and glutamatergic MS/DB neurones (Fig. 9). Although, MS/DB glutamatergic neurones appear to be activated by Ach at the relevant frequency, it remains to be determined if and how they are involved in theta and in learning and memory. A recent study has shown that blocking AMPA/kainate receptors in the septum of unanaesthetized alert walking rat in vivo (known has type 1 theta; Stewart & Fox, 1990) did not affect hippocampal theta (Leung & Shen, 2004). However, others have shown that hippocampal theta triggered by intraseptal ACh (using physostigmine) in anaesthetized (i.e. immobile type 2 theta) rats in vivo is strongly antagonized by intraseptal perfusion of AMPA receptor antagonists (Puma et al. 1996; Puma & Bizot, 1999). Therefore, it may be speculated that carbachol-activated MS/DB glutamatergic neurones contribute to atropine-sensitive theta (type 2 theta) recorded during immobility in anaesthetized (Stewart & Fox, 1990) or unanaesthetized rats prior to the initiation of movements (Oddie & Bland, 1998) but not to the atropine-insensitive theta observed in behaving walking rats (Lawson & Bland, 1993). It will be important to determine how MS/DB glutamatergic neurones are involved in hippocampal theta recorded during immobility in unanaesthetized animals. Although it remains unknown how MS/DB glutamate neurones contribute to theta rhythm, there is evidence that blocking AMPA/kainate receptors in the medial septum can abolish the expression of two different types of hippocampal-dependent memory formation (Izquierdo, 1994).

In conclusion, this study presents the first evidence that glutamatergic neurones in the MS/DB have a significant functional role. These neurones are part of a glutamatergic neuronal network that can be activated by acetylcholine and may potentially drive cholinergic and GABAergic neurones in a physiologically relevant manner. Therefore, MS/DB glutamatergic neurones could potentially be important in septal function and in hippocampal activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). F.M. was supported by a fellowship from the Alzheimer Society of Canada. We thank Dr Louis-Éric Trudeau for his helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript and Claude Gauthier for technical assistance.

References

- Alonso A, Gaztelu JM, Buno W, JR, Garcia-Austt E. Cross-correlation analysis of septohippocampal neurons during theta-rhythm. Brain Res. 1987;413:135–146. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alreja M, Wu M, Liu W, Atkins JB, Leranth C, Shanabrough M. Muscarinic tone sustains impulse flow in the septohippocampal GABA but not cholinergic pathway: implications for learning and memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8103–8110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08103.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Kurz J. An analysis of the origins of the cholinergic and noncholinergic septal projections to the hippocampal formation of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1985;240:37–59. doi: 10.1002/cne.902400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JN, MacVicar BA. Theta-frequency facilitation of AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic currents in the principal cells of the medial septum. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1709–1718. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.4.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, D'Antuono M, Louvel J, Kohling R, Biagini G, Pumain R, D'Arcangelo G, Tancredi V. Network and pharmacological mechanisms leading to epileptiform synchronization in the limbic system in vitro. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;68:167–207. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Psarropoulou C, Tancredi V, Fueta Y. On the synchronous activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the CA3 subfield of juvenile rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1018–1029. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.3.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baisden RH, Woodruff ML, Hoover DB. Cholinergic and non-cholinergic septo-hippocampal projections: a double-label horseradish peroxidase-acetylcholinesterase study in the rabbit. Brain Res. 1984;290:146–151. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90745-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarosie M, Avoli M. CA3-driven hippocampal-entorhinal loop controls rather than sustains in vitro limbic seizures. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9308–9314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09308.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland BH, Oddie SD, Colom LV, Vertes RP. Extrinsic modulation of medial septal cell discharges by the ascending brainstem hippocampal synchronizing pathway. Hippocampus. 1994;4:649–660. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland SK, Bland BH. Medial septal modulation of hippocampal theta cell discharges. Brain Res. 1986;375:102–116. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90963-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton MGLO, Turco JJ, Kriegstein AR. Whole cell recording from neurons in slices of reptilian and mammalian cerebral cortex. J Neurosci Methods. 1989;30:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokor H, Csaki A, Kocsis K, Kiss J. Cellular architecture of the nucleus reuniens thalami and its putative aspartatergic/glutamatergic projection to the hippocampus and medial septum in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1227–1239. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brashear HR, Zaborszky L, Heimer L. Distribution of GABAergic and cholinergic neurons in the rat diagonal band. Neuroscience. 1986;17:439–451. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90258-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchs PA, Stoppini L, Muller D. Structural modifications associated with synaptic development in area CA1 of rat hippocampal organotypic cultures. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1993;71:81–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90108-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler JP, Crutcher KA. The septohippocampal projection in the rat: an electron microscopic horseradish peroxidase study. Neuroscience. 1983;10:685–696. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chedotal A, Cozzari C, Faure MP, Hartman BK, Hamel E. Distinct choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) bipolar neurons project to local blood vessels in the rat cerebral cortex. Brain Res. 1994;646:181–193. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossette P, Umbriaco D, Zamar N, Hamel E, Descarries L. Recovery of choline acetyltransferase activity without sprouting of the residual acetylcholine innervation in adult rat cerebral cortex after lesion of the nucleus basalis. Brain Res. 1993;630:195–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90657-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danik M, Cassoly E, Manseau F, Sotty F, Mouginot D, Williams S. Frequent coexpression of the vesicular glutamate transporter 1 and 2 genes, as well as coexpression with genes for choline acetyltransferase or glutamic acid decarboxylase in neurons of the rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2005 doi: 10.1002/jnr.20500. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danik M, Puma C, Quirion R, Williams S. Widely expressed transcripts for chemokine receptor CXCR1 in identified glutamatergic, gamma-aminobutyric acidergic, and cholinergic neurons and astrocytes of the rat brain: a single-cell reverse transcription-multiplex polymerase chain reaction study. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:286–295. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhala VI, Staley KJ. Transition from interictal to ictal activity in limbic networks in vitro. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7873–7880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07873.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RTJR, Troyer MD, Pahner I, Nygaard GO, Tran CH, Reimer RJ, Bellocchio EE, Fortin D, Storm-Mathisen J, Edwards RH. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters defines two classes of excitatory synapse. Neuron. 2001;31:247–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM, Gorman LK, Markowska AL. Oxotremorine infusions into the medial septal area of middle-aged rats affect spatial reference memory and ChAT activity. Behav Brain Res. 1996;80:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(96)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye GD, Fincher A. Sustained ethanol inhibition of native AMPA receptors on medial septum/diagonal band (MS/DB) neurons. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:87–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahwiler BH, Capogna M, Debanne D, McKinney RA, Thompson SM. Organotypic slice cultures: a technique has come of age. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:471–477. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner HL, Whittington MA, Henderson Z. Induction by kainate of theta frequency, rhythmic activity in the rat medial septum/diagonal band complex in vitro. J Physiol. 2005;564:83–102. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.080622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens B, Olton DS. Local modulation of basal forebrain: effects on working and reference memory. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3578–3587. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-06-03578.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givens B, Olton DS. Bidirectional modulation of scopolamine-induced working memory impairments by muscarinic activation of the medial septal area. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1995;63:269–276. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogolak G, Stumpf C, Petsche H, Sterc J. The firing pattern of septal neurons and the form of the hippocampal theta wave. Brain Res. 1968;7:201–207. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(68)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalo-Ruiz A, Morte L. Localization of amino acids, neuropeptides and cholinergic markers in neurons of the septum-diagonal band complex projecting to the retrosplenial granular cortex of the rat. Brain Res Bull. 2000;52:499–510. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelova N, Reiner PB. Role of the afterhyperpolarization in control of discharge properties of septal cholinergic neurons in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:695–706. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.2.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith WH. Membrane properties of cell types within guinea pig basal forebrain nuclei in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:1590–1612. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.5.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith WH, Matthews RT. Electrophysiology of AChE-positive neurons in basal forebrain slices. Neurosci Lett. 1986;71:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90553-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritti I, Mainville L, Mancia M, Jones BE. GABAergic and other noncholinergic basal forebrain neurons, together with cholinergic neurons, project to the mesocortex and isocortex in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;383:163–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajszan T, Alreja M, Leranth C. Intrinsic vesicular glutamate transporter 2-immunoreactive input to septohippocampal parvalbumin-containing neurons: novel glutamatergic local circuit cells. Hippocampus. 2004;14:499–509. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson Z, Boros A, Janzso G, Westwood AJ, Monyer H, Halasy K. Somato-dendritic nicotinic receptor responses recorded in vitro from the medial septal diagonal band complex of the rodent. J Physiol. 2005;562:165–182. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.070300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisano S, Hoshi K, Ikeda Y, Maruyama D, Kanemoto M, Ichijo H, Kojima I, Takeda J, Nogami H. Regional expression of a gene encoding a neuron-specific Na+-dependent inorganic phosphate cotransporter (DNPI) in the rat forebrain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;83:34–43. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao SH, Frye GD. AMPA receptors on developing medial septum/diagonal band neurons are sensitive to early postnatal binge-like ethanol exposure. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;142:89–99. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(03)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettner JE. Kainate receptors and synaptic transmission. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;70:387–407. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo I. Pharmacological evidence for a role of long-term potentiation in memory. FASEB J. 1994;8:1139–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo I, Da Cunha C, Rosat R, Jerusalinsky D, Ferreira MB, Medina JH. Neurotransmitter receptors involved in post-training memory processing by the amygdala, medial septum, and hippocampus of the rat. Behav Neural Biol. 1992;58:16–26. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(92)90847-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasek MC, Griffith WH. Pharmacological characterization of ionotropic excitatory amino acid receptors in young and aged rat basal forebrain. Neuroscience. 1998;82:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskiw GE, Tizabi Y, Lipska BK, Kolachana BS, Wyatt RJ, Gilad GM. Evidence for a frontocortical-septal glutamatergic pathway and compensatory changes in septal glutamate uptake after cortical and fornix lesions in the rat. Brain Res. 1991;550:7–10. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90398-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GA, Norris SK, Henderson Z. Conduction velocities and membrane properties of different classes of rat septohippocampal neurons recorded in vitro. J Physiol. 1999;517:867–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0867s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalilov I, Esclapez M, Medina I, Aggoun D, Lamsa K, Leinekugel X, Khazipov R, Ben-Ari Y. A novel in vitro preparation: the intact hippocampal formation. Neuron. 1997;19:743–749. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80956-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J, Csaki A, Bokor H, Kocsis K, Kocsis B. Possible glutamatergic/aspartatergic projections to the supramammillary nucleus and their origins in the rat studied by selective [3H]d-aspartate labelling and immunocytochemistry. Neuroscience. 2002;111:671–691. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J, Csaki A, Bokor H, Shanabrough M, Leranth C. The supramammillo-hippocampal and supramammillo-septal glutamatergic/aspartatergic projections in the rat: a combined [3H]d-aspartate autoradiographic and immunohistochemical study. Neuroscience. 2000;97:657–669. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J, Magloczky Z, Somogyi J, Freund TF. Distribution of calretinin-containing neurons relative to other neurochemically identified cell types in the medial septum of the rat. Neuroscience. 1997;78:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J, Patel AJ, Baimbridge KG, Freund TF. Topographical localization of neurons containing parvalbumin and choline acetyltransferase in the medial septum-diagonal band region of the rat. Neuroscience. 1990;36:61–72. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis B, Li S. In vivo contribution of h-channels in the septal pacemaker to theta rhythm generation. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2149–2158. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis K, Kiss J, Csaki A, Halasz B. Location of putative glutamatergic neurons projecting to the medial preoptic area of the rat hypothalamus. Brain Res Bull. 2003;61:459–468. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshiya N, Smith JC. Neuronal pacemaker for breathing visualized in vitro. Nature. 1999;400:360–363. doi: 10.1038/22540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]